Submitted:

06 December 2024

Posted:

06 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

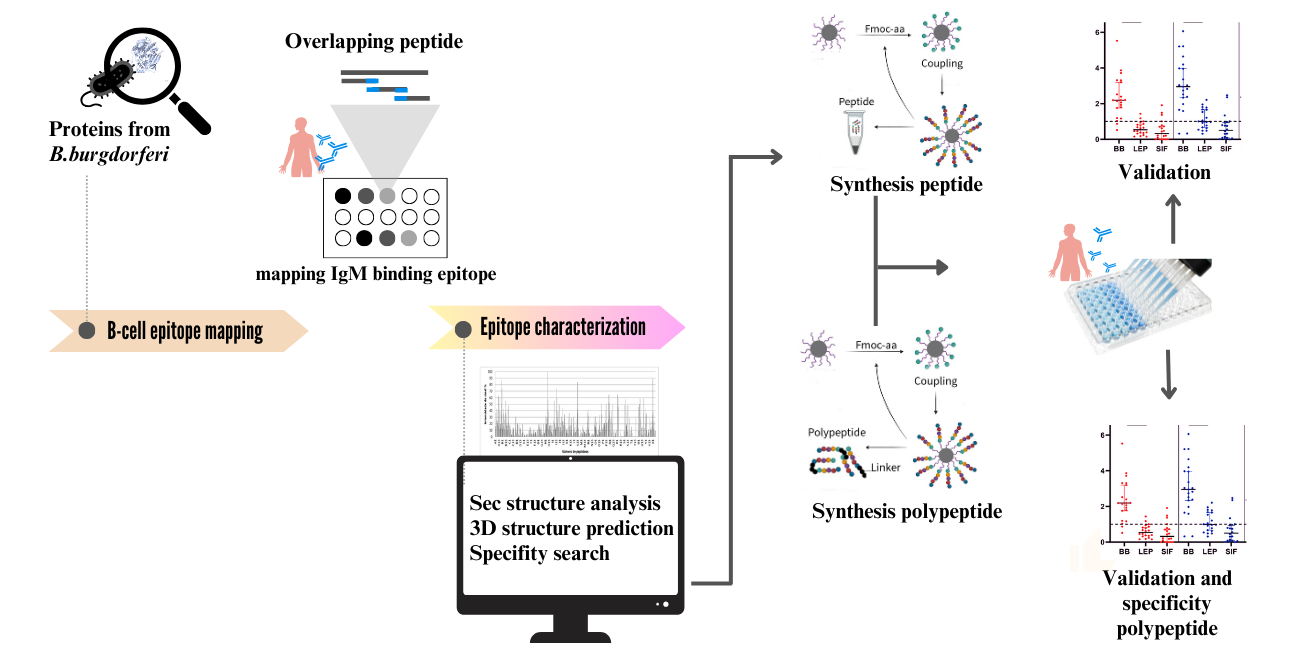

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human Serum Samples

2.2. Preparation of the Cellulose Membrane-Bound Peptide Array

2.3. Evaluation of SPOT Membranes

2.4. Scanning and Quantification of Spot Signal Intensities

2.5. Peptide preparation

2.6. Synthesis of Bi-Specific Antigen Peptides

2.7. Immunoenzymatic Assay (ELISA)

2.8. Computational Tools

2.9. Data Analysis

3. Result

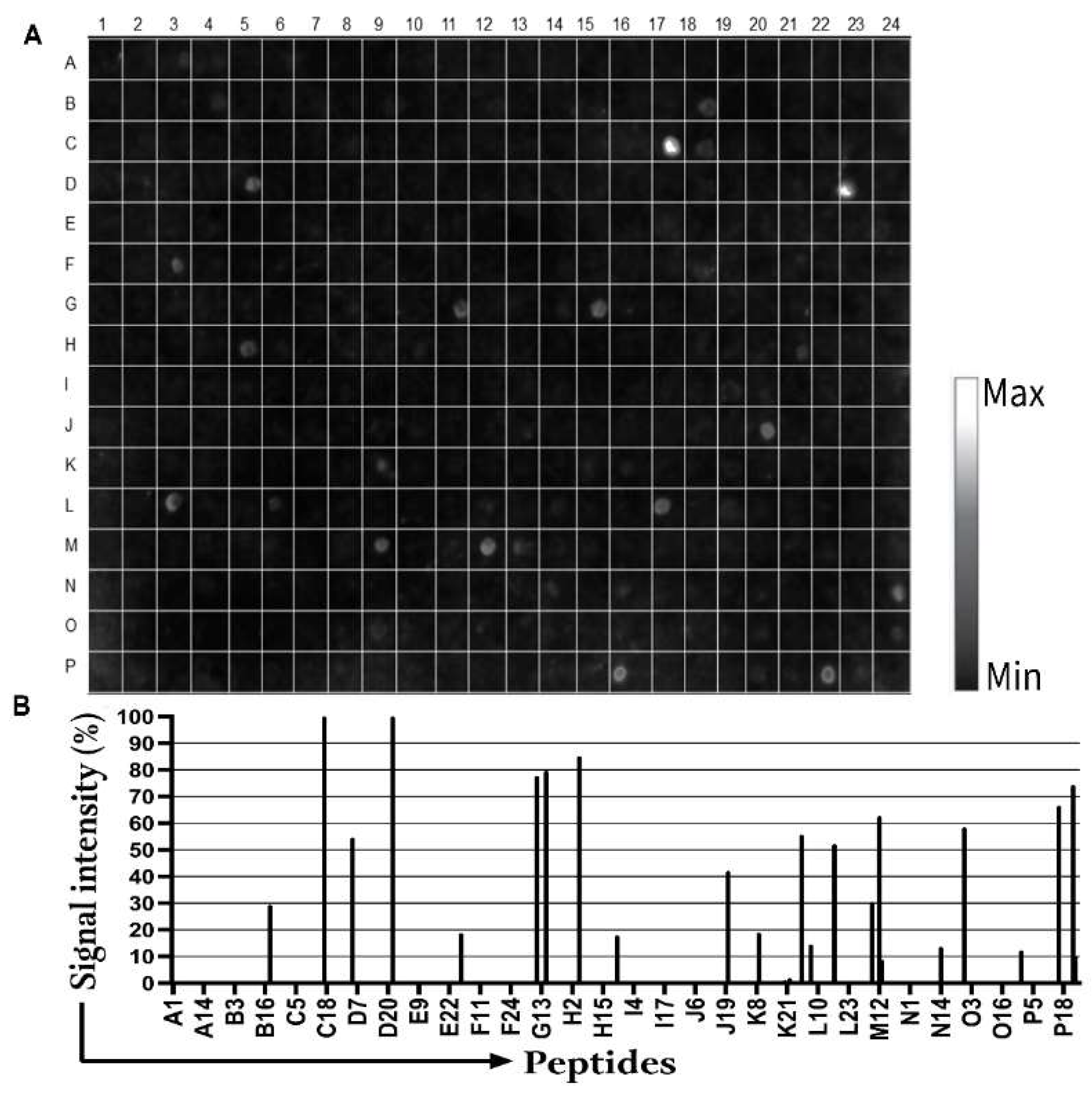

3.1. Detection of IgM Epitopes in Surface Proteins of B. burgdorferi

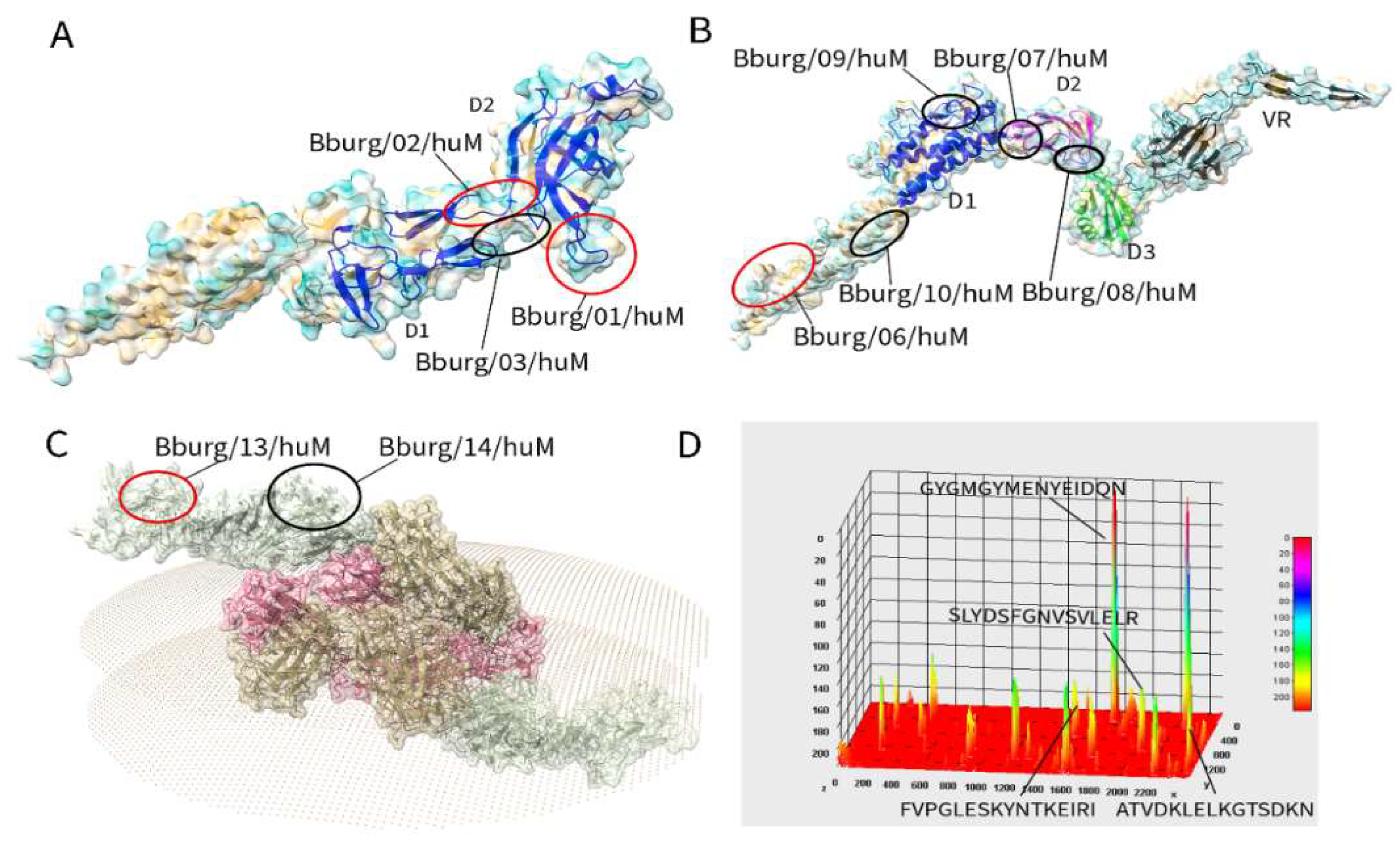

3.2. Secondary Structure and Structural Mapping of the IgM Epitopes

| Protein | Epitope | 2nd structure* | a number | Peptide match** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FlgE | Bburg/01/huM | C | 209 SLYDSFGN 216 | Various Borrelia sp |

| Bburg/02/huM | C | 321 GYGMGYME 328 | Various Borrelia sp | |

| Bburg/03/huM | C+S | 381 VRIGETGLAGLGDIR 395 | Another organism | |

| Flg41 kDa | Bburg/04/huM | H+C | 121 ANLSKTQEKLSSGYR 135 | Another organism |

| Bburg/05/huM | H+C | 322 AQANQVPQYVLSLLR 336 | Another organism. | |

| Flg hook2 | Bburg/06/huM | C | 08 PGLESKYN 15 | Various Borrelia sp |

| Bburg/07/huM | C+S | 76 SGNSSNSEVLTLSTR 90 | Another organism | |

| Bburg/08/huM | C+S | 391 AENAKIKFDGVDVER 405 | Another organism | |

| Bburg/09/huM | H+C+S | 546 RYLRLDEKKFDESIR 560 | Another organism | |

| Bburg/10/huM | H | 616 QKNKVEDYKKKYEDR 630 | Another organism | |

| BBA03 | Bburg/11/huM | C | 31 DEKSQAKSNLVD 42 | Another organism |

| Bburg/12/huM | H+C | 46 IEFSKATPLEKLVSR 60 | Another organism | |

| OSP A | Bburg/13/huM | C | 56 ATVDKLELKGTSDKN 70 | Various Borrelia sp |

| Bburg/14/huM | C | 266 EGSAVEITKL 275 | Another organism |

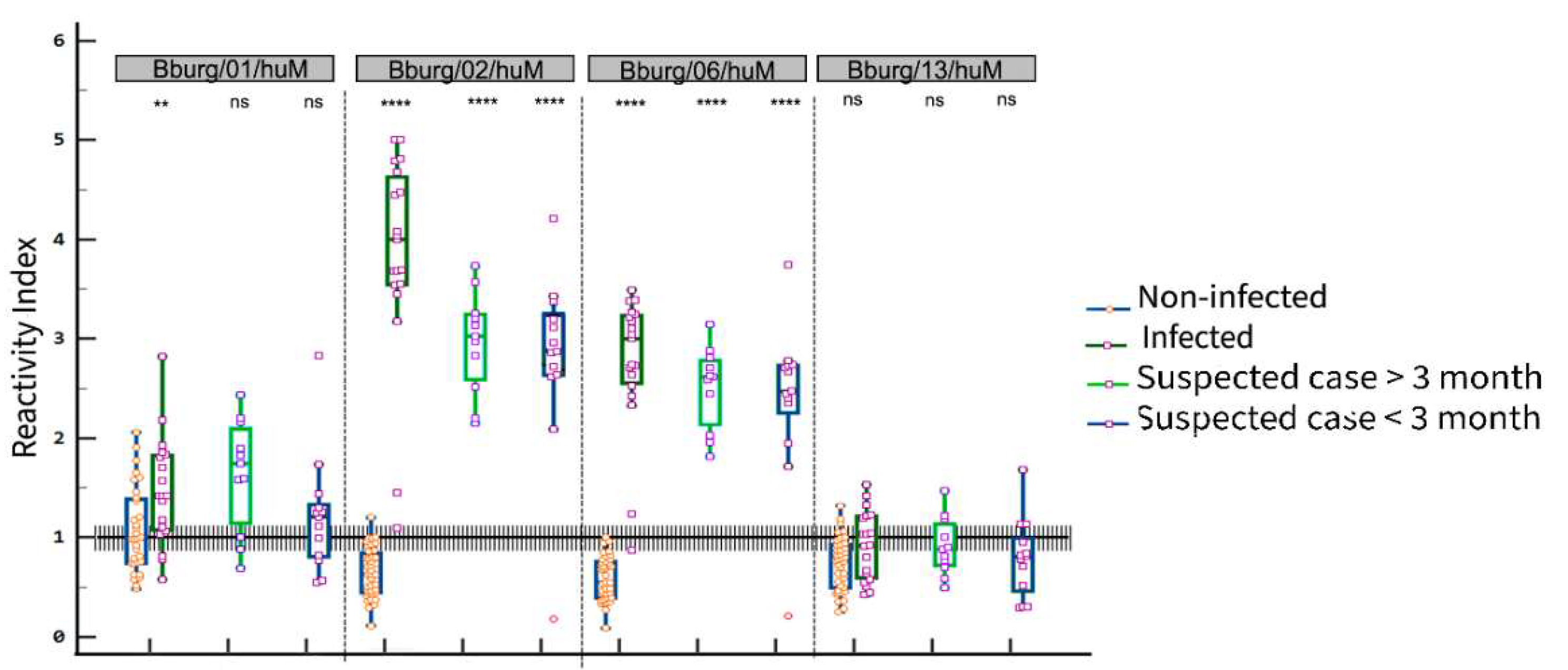

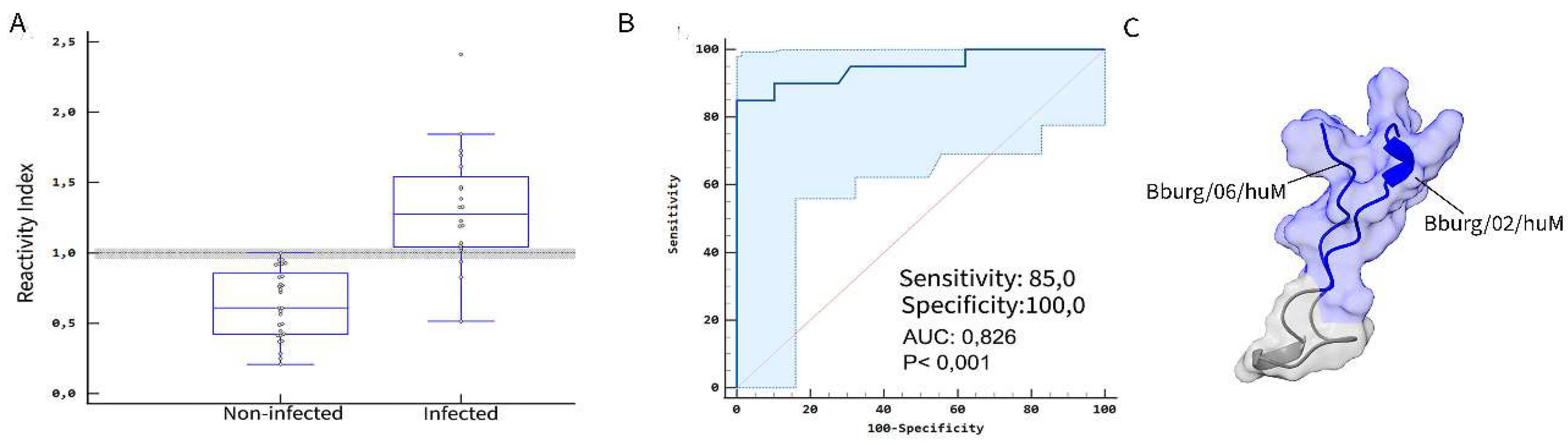

3.3. ELISA Screening

| Suspected case | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infected | > 3 months | < 3 months | |||||||||||

| Peptide | Se (%) | Sp (%) | AUC | Ac (%) | Se (%) | Sp (%) | AUC | Se (%) | Sp (%) | AUC | |||

| Bburg/01/huM | 82.4 | 56.2 | 0.721 | 66.6 | 72.7 | 56.2 | 0.557 | 76.9 | 59.4 | 0.671 | |||

| Bburg/02/huM | 100.0 | 97.44 | 0.999 | 96.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 1 | 92.3 | 100.0 | 0.925 | |||

| Bburg/06/huM | 94.74 | 100.0 | 0.996 | 98.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 1 | 92.3 | 100.0 | 0.925 | |||

| Bburg/13/huM | 47.37 | 87.18 | 0.652 | 74.1 | 72.7 | 59.0 | 0.622 | 76.9 | 59.4 | 0.694 | |||

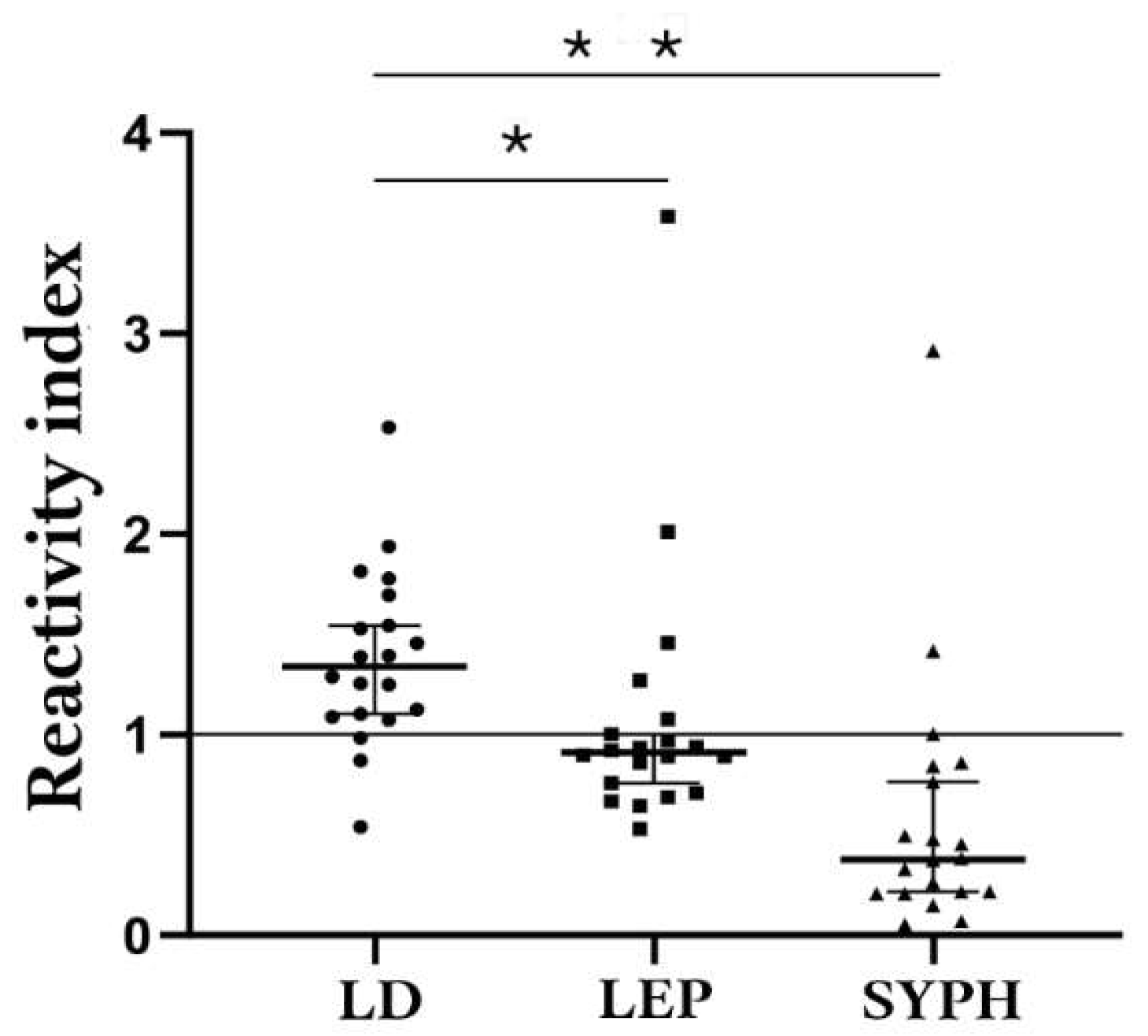

3.4. Potential cross-reactivity of the epitopes and validation of bi-specific peptides as antigens

| Comparison Group | Median | 75% Percentile | 25% Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lyme-Borreliosis | 0,2613 | 0,3235 | 0,2131 |

| Leptospirosis | 0,0755 | 0,08788 | 0,060 |

| Syphilis | 0,02175 | 0,04738 | 0,01213 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mead, P.; Hinckley, A.; Kugeler, K. Lyme disease surveillance and epidemiology in the United States: A historical perspective. J Infect Dis 2024, 230, S11–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burn, L.; Vyse, A.; Pilz, A.; Tran, T.M.P.; Fletcher, M.A.; Angulo, F.J.; Gessner, B.D.; Moïsi, J.C.; Stark, J.H. Incidence of Lyme Borreliosis in Europe: A systematic review (2005-2020). Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2023, 23, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sykes, R.A.; Makiello, P. An estimate of Lyme borreliosis incidence in Western Europe. J Public Health 2016, 39, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshinari, N.H.; Bonoldi, V.L.N.; Bonin, S.; Falkingham, E.; Trevisan, G. The current state of knowledge on Baggio-Yoshinari syndrome (Brazilian Lyme Disease-like Illness): Chronological presentation of historical and scientific events observed over the last 30 Years. Pathogens 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonoldi, V.L.N.; Yoshinari, N.H.; Trevisan, G.; Bonin, S. Baggio-Yoshinari syndrome: A report of five cases. Microorganisms. 2024, 12, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge, F.R.; Muñoz-Leal, S.; de Oliveira, G.M.B.; Serpa, M.C.A.; Magalhães, M.M.L.; de Oliveira, L.M.B.; Moura, F.B.P.; Teixeira, B.M.; Labruna, M.B. Novel Borrelia genotypes from Brazil indicate a new group of Borrelia spp. associated with South American Bats. J Med Entomol 2023, 60, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, J.; Piesman, J.; de Silva, A.M. Antigenic and genetic heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi populations transmitted by ticks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miziara, C.S.M.G.; Gelmeti Serrano, V.A.; Yoshinari, N. Passage of Borrelia burgdorferi through diverse Ixodid hard ticks causes distinct diseases: Lyme borreliosis and Baggio-Yoshinari syndrome. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2018, 73, e394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodecka, B.; Kolomiiets, V. Genetic diversity of Borreliaceae species detected in natural populations of Ixodes ricinus ticks in northern Poland. Life 2023, 13, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karageorgou, I.; Koutantou, M.; Papadogiannaki, I.; Voulgari-Kokota, A.; Makka, S.; Angelakis, E. Serological evidence of possible Borrelia afzelii Lyme disease in Greece. New Microbes New Infect 2022, 46, 100978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancilla-Agrono, L.Y.; Banguero-Micolta, L.F.; Ossa-Lopez, P.A.; Ramirez-Chaves, H.E.; Castano-Villa, G.J.; Rivera-Paez, F.A. Is Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto in South America? First molecular evidence of its presence in Colombia. Trop Med Infect Dis 2022, 7, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudenko, N.; Golovchenko, M.; Horak, A.; Grubhoffer, L.; Mongodin, E.F.; Fraser, C.M.; Qiu, W.; Luft, B.J.; Morgan, R.G.; Casjens, S.R.; et al. , Genomic confirmation of Borrelia garinii. United States Emerg Infect Dis 2023, 29, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, Y.; Leyer, C.; Lefebvre, N.; Revest, M.; Rabaud, C.; Alfandari, S.; Christmann, D.; Tattevin, P. Feedback on difficulties raised by interpreting serological tests for Lyme disease diagnosis. Med Mal Infect 2014, 44, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodym, P.; Kurzová, Z.; Berenová, D.; Pícha, D.; Smíšková, D.; Moravcová, L.; Malý, M. Serological diagnostics of Lyme Borreliosis: Comparison of universal and Borrelia species-specific tests based on whole-cell and recombinant antigens. J Clin Microbiol 2018, 56, e00601–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ružić-Sabljić, E.; Cerar, T. Progress in the molecular diagnosis of Lyme disease. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2017, 17, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldin, C.; Parola, P.; Raoult., D. Limitations of diagnostic tests for bacterial infections. Med Mal Infect. 2019, 49, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toumanios C, Prisco L, Dattwyler RJ, Arnaboldi PM. Linear B cell epitopes derived from the multifunctional surface lipoprotein BBK32 as targets for the serodiagnosis of Lyme disease. mSphere 2019, 4, e00111-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarz R, Guo C, Sanchez-Vicente S, Horn E, Eschman A, Turk SP, Lipkin WI, Marques A. Identification of reactive Borrelia burgdorferi peptides associated with Lyme disease. mBio 2024, 15, e0236024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durans AM, Napoleão-Pêgo P, Reis FCG, Dias ER, Machado LESF, Lechuga GC, Junqueira ACV, De-Simone SG, Provance-Jr DW. Chagas disease diagnosis with Trypanosoma cruzi exclusive epitopes in GFP. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 1029. [Google Scholar]

- Guérin, M.; Shawky, M.; Zedan, A.; Octave, S.; Avalle, B.; Maffucci, I.; Padiolleau-Lefèvre, S. Lyme borreliosis diagnosis: state of the art of improvements and innovations. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilly, K.; Krum, J.G.; Bestor, A.; Jewett, M.W.; Grimm, D.; Bueschel, D.; Byram, R.; Dorward, D.; Vanraden, M.J.; Stewart, P.; et al. Borrelia burgdorferi OspC protein is required exclusively in a crucial early stage of mammalian infection. Infect Immun 2006, 74, 3554–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, J.M.; Bono, J.L.; Rosa, P.A.; Schrumpf, M.E.; Schwan, T.G.; Policastro, P.F. Outer surface protein A protects Lyme disease spirochetes from acquired host immunity in the tick vector. Infect Immun 2008, 76, 5228–5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykowski, T.; Woodman, M.E.; Cooley, A.E.; Brissette, C.A.; Wallich, R.; Brade, V.; Kraiczy, P.; Stevenson, B. Borrelia burgdorferi complement regulator-acquiring surface proteins (BbCRASPs): Expression patterns during the mammal-tick infection cycle. Int J Med Microbiol 2008, 298, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brissette, C.A.; Haupt, K.; Barthel, D.; Cooley, A.E.; Bowman, A.; Skerka, C.; Wallich, R.; Zipfel, P.F.; Kraiczy, P.; Stevenson, B. Borrelia burgdorferi infection-associated surface proteins ErpP, ErpA, and ErpC bind human plasminogen. Infect Immun 2009, 77, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Sultan, S.; Yerke, A.; Moon, K.H.; Wooten, R.M.; Motaleb, M.A. Borrelia burgdorferi CheY2 is dispensable for chemotaxis or motility but crucial for the infectious life cycle of the spirochete. Infect Immun 2017, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.H.; Hobbs, G.; Motaleb, M.A. Borrelia burgdorferi CheD promotes various functions in chemotaxis and the pathogenic life cycle of the spirochete. Infect Immun 2016, 84, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulzova, L.; Bhide, M. Outer surface proteins of Borrelia: peerless immune evasion tools. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2014, 15, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Carroll, B.L.; Liu, J. Structural basis of bacterial flagellar motor rotation and switching. Trends Microbiol 2021, 29, 1024–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Qin, Z.; Chang, Y.; Liu, J.; Malkowski, M.G.; Shipa, S.; Li, L.; Qiu, W.; Zhang, J.R.; Li, C. Analysis of a flagellar filament cap mutant reveals that HtrA serine protease degrades unfolded flagellin protein in the periplasm of Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol 2019, 111, 1652–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutemark, C.; Alicot, E.; Bergman, A.; Ma, M.; Getahun, A.; Ellmerich, S.; Carroll, M.C.; Heyman, B. Requirement for complement in antibody responses is not explained by the classic pathway activator IgM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, E934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowicz, M.; Reiter, M.; Gamper, J.; Stanek, G.; Stockinger, H. Persistent anti-Borrelia IgM antibodies without Lyme Borreliosis in the clinical and immunological context. Microbiol Spectr 2021, 9, e0102021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavnezer J, Amemiya CT. Evolution of isotype switching. Semin. Immunol. 2004, 16, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chino, M.E.T.A.; Bonoldi, V.L.N.; Pereira, R.M.R.; Gazeta, G.S.; Carvalho, J.P.R.S.; Napoleão-Pêgo, P.; Durans, A.M.; Souza, A.L.A.; De-Simone, S.G. New epitopes for the serodiagnosis of human Borreliosis. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, S.E.; Thanassi, D.G.; Benach, J.L. Generation of a complement-independent bactericidal IgM against a relapsing fever Borrelia. J Immunol 2004, 172, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowicz, M.; Reiter, M.; Gamper, J.; Stanek, G.; Stockinger, H. Persistent anti-Borrelia IgM antibodies without Lyme Borreliosis in the clinical and immunological context. Microbiol Spectr 2021, 9, e0102021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalish, R.A.; McHugh, G.; Granquist, J.; Shea, B.; Ruthazer, R.; Steere, A.C. Persistence of immunoglobulin M or immunoglobulin G antibody responses to Borrelia burgdorferi 10-20 years after active Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis 2001, 33, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockenstedt LK, Wooten RM, Baumgarth N. Immune response to Borrelia: Lessons from Lyme disease spirochetes. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2021, 42, 145–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.; Nelson, C.; Molins, C.; Mead, P.; Schriefer, M. Current guidelines, common clinical pitfalls, and future directions for laboratory diagnosis of Lyme disease, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2016, 22, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshinari, N.H.; Mantovani, E.; Bonoldi, V.L.; Marangoni, R.G.; Gauditano, G. Brazilian lyme-like disease or Baggio-Yoshinari syndrome: exotic and emerging Brazilian tick-borne zoonosis. Rev Assoc Med Bras 2010, 56, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselbeck, A.H.; Im, J.; Prifti, K.; Marks, F.; Holm, M.; Zellweger, R.M. Serology as a tool to assess infectious disease landscapes and guide public health policy. Pathogens 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signorino, G.; Arnaboldi, P.M.; Petzke, M.M.; Dattwyler, R.J. Identification of OppA2 linear epitopes as serodiagnostic markers for Lyme disease. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2014, 21, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, S.; Nayak, S.; Williams, T.; di Santa Maria, F.S.; Guedes, M.S.; Chaves, R.C.; Linder, V.; Marques, A.R.; Horn, E.J.; Wong, S.J.; et al. A multiplexed serologic test for diagnosis of Lyme disease for point-of-care use. J Clin Microbiol 2019, 57, e01142-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Morrissey, J.J.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Naik, R.R.; Singamaneni, S. Plasmonically enhanced ultrasensitive epitope-specific serologic assay for COVID-19. Anal Chem 2022, 94, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, H.S. Measuring molecular biomarkers in epidemiologic studies: Laboratory techniques and biospecimen considerations. Stat Med 2012, 31, 2400–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Simone, S.G.; Napoleão-Pego, P.; Teixeira-Pinto, L.A.; Santos, J.D.; De-Simone, T.S.; Melgarejo, A.R.; Aguiar, A.S.; Marchi-Salvador, D.P. Linear B-cell epitopes in BthTX-1, BthTX-II and BthA-1, phospholipase A₂'s from Bothrops jararacussu snake venom, recognized by therapeutically neutralizing commercial horse antivenom. Toxicon 2013, 72, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F.R.; Napoleão-Pego, P.; De-Simone, S.G. Identification of linear B epitope of pertactin of Bordetela pertussis induced by immunization with whole and acellular vaccine. Vaccine 2014, 32, 6251–6258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Simone, S.G.; Gomes, L.R.; Napoleão-Pêgo, P.; Lechuga, G.C.; de Pina, J.S.; da Silva, F.R. Epitope Mapping of the diphtheria toxin and development of an ELISA-specific diagnostic assay. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Joung, H.A.; Goncharov, A.; Palanisamy, B.; Ngo, K.; Pejcinovic, K.; Krockenberger, N.; Horn, E.J.; Garner, O.B.; Ghazal, E.; et al. , Rapid single-tier serodiagnosis of Lyme disease. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 7124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenedy, M.R.; Lenhart, T.R.; Akins, D.R. The role of Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface proteins. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2012, 66, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilske, B.; Luft, B.; Schubach, W.H.; Zumstein, G.; Jauris, S.; Preac-Mursic, V.; Kramer, M.D. Molecular analysis of the outer surface protein A (OspA) of Borrelia burgdorferi for conserved and variable antibody binding domains. Med Microbiol Immunol 1992, 181, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilske, B.; Luft, B.; Schubach, W.H.; Zumstein, G.; Jauris, S.; Preac-Mursic, V.; Kramer, M.D. Molecular analysis of the outer surface protein A (OspA) of Borrelia burgdorferi for conserved and variable antibody binding domains. Med Microbiol Immunol 1992, 181, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Luft, B.J.; Schubach, W.; Dattwyler, R.J.; Gorevic, P.D. Mapping the major antigenic domains of the native flagellar antigen of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Microbiol 1992, 30, 1535–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Ma, X.; Nyman, D.; Povlsen, K.; Akguen, N.; Schneider, E.M. Antigen biochips verify and extend the scope of antibody detection in Lyme borreliosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2007, 59, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, M.J.; Miller, M.; James, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, K.; Li, C.; Charon, N.W.; Crane, B.R. Structure and chemistry of lysinoalanine cross-linking in the spirochaete flagella hook. Nat Chem Biol 2019, 15, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridmanis, J.; Bobrovs, R.; Brangulis, K.; Tārs, K.; Jaudzems, K. Structural and Functional Analysis of BBA03, Borrelia burgdorferi competitive advantage promoting outer surface lipoprotein. Pathogens 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondino, S.; San Martin, F.; Buschiazzo, A. 3D cryo-EM imaging of bacterial flagella: Novel structural and mechanistic insights into cell motility. J Biol Chem 2022, 298, 102105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izac, J.R.; Oliver, L.D., Jr.; Earnhart, C.G.; Marconi, R.T. Identification of a defined linear epitope in the OspA protein of the Lyme disease spirochetes that elicits bactericidal antibody responses: Implications for vaccine development. Vaccine 2017, 35, 3178–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steere, A.; Sikand, V.K.; Meurice, F.; Parenti, D.L.; Fikrig, E.; Schoen, R.T.; Nowakowski, J.; Schmid, C.H.; Laukamp, S.; Buscarino, C.; et al. , Vaccination against Lyme disease with recombinant Borrelia burgdorferi outer-surface lipoprotein A with adjuvant. Lyme disease vaccine study group. N Engl J Med 1998, 339, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigal, L.H.; Zahradnik, J.M.; Lavin, P.; Patella, S.J.; Bryant, G.; Haselby, R.; Hilton, E.; Kunkel, M.; Adler-Klein, D.; Doherty, T.; et al. , A vaccine consisting of recombinant Borrelia burgdorferi outer-surface protein A to prevent Lyme disease. Recombinant outer-surface protein A Lyme Disease Vaccine Study Consortium. N Engl J Med. Erratum in: N Engl J Med 1998, 339, 571. [CrossRef]

- Gingerich, M.C.; Nair, N.; Azevedo, J.F.; Samanta, K.; Kundu, S.; He, B.; Gomes-Solecki, M. Intranasal vaccine for Lyme disease provides protection against tick transmitted Borrelia burgdorferi beyond one year. NPJ Vaccines 2024, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Oeemig, J.S.; Kolodziejczyk, R.; Meri, T.; Kajander, T.; Lehtinen, M.J.; Iwaï, H.; Jokiranta, T.S.; Goldman, A. Structural basis for complement evasion by Lyme disease pathogen Borrelia burgdorferi. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 18685–18695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makabe, K.; Tereshko, V.; Gawlak, G.; Yan, S.; Koide, S. Atomic-resolution crystal structure of Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein A via surface engineering. Protein Sci 2006, 15, 1907–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreutzberger, M.A.B.; Sobe, R.C.; Sauder, A.B.; Chatterjee, S.; Peña, A.; Wang, F.; Giron, J.A.; Kiessling, V.; Costa, T.R.D.; Conticello, V.P.; et al. Flagellin outer domain dimerization modulates motility in pathogenic and soil bacteria from viscous environments. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, N.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, X.; Yan, Z.; Shao, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Fu, C. Therapeutic peptides: current applications and future directions. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Simone, S.G.; Napoleão-Pêgo, P.; Lechuga, G.C.; Carvalho, J.P.R.S.; Gomes, L.R.; Cardozo, S.V.; Morel, C.M.; Provance, D.W.; Silva, F.R.d. High-throughput IgG epitope mapping of tetanus neurotoxin: Implications for immunotherapy and vaccine design. Toxins 2023, 15, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, L.A.; Greig, J.; Mascarenhas, M.; Harding, S.; Lindsay, R.; Ogden, N. The accuracy of diagnostic tests for Lyme disease in humans, A systematic review and meta-analysis of North American research. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0168613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.R. Laboratory diagnosis of Lyme disease: advances and challenges. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2015, 29, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagatie, O.; Verheyen, A.; Nijs, E.; Batsa Debrah, L.; Debrah, Y.A.; Stuyver, L.J. Performance evaluation of 3 serodiagnostic peptide epitopes and the derived multiepitope peptide OvNMP-48 for detection of Onchocerca volvulus infection. Parasitol Res 2019, 118, 2263–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandrowski, E.L. , Turbett S.E., Nigrovic L.E., Klontz E.H., Branda J.A. Comparative evaluation of commercial test kits cleared for use in modified two-tiered testing algorithms for serodiagnosis of Lyme disease. J Infect Dis 2024, 14, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Bier, N.S.; Camire, A.C.; Patel, D.T.; Billingsley, J.S.; Hodges, K.R.; Marconi, R.T. Development of novel multi-protein chimeric immunogens. that protect against infection with the Lyme disease agent, Borreliella burgdorferi. mBio 2024, 7, e0215924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnarelli, L.A.; Anderson, J.F.; Johnson, R.C. Cross-reactivity in serological tests for Lyme disease and other spirochetal infections. J Infect Dis 1987, 156, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojciechowska-Koszko, I.; Kwiatkowski, P.; Sienkiewicz, M.; Kowalczyk, M.; Kowalczyk, E.; Dołęgowska, B. Cross-reactive results in serological tests for Borreliosis in patients with active viral infections. Pathogens 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doskaliuk, B.; Zimba, O. Borrelia burgdorferi and autoimmune mechanisms: implications for mimicry, misdiagnosis, and mismanagement in Lyme disease and autoimmune disorders. Rheumatol Int 2024, 44, 2265–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).