1. Introduction

Space-time data prediction, as one of the core tasks of data analysis, has important application value in fields such as meteorological forecasting [

1], financial market analysis [

2], and industrial equipment monitoring [

3,

4]. The classic LSTM network excels at modeling long-term dependencies [

5,

6,

7,

8], yet it faces three fundamental limitations in modern prediction tasks: (1) gradient vanishing in deep architectures restricts convergence [

9]; (2) computational complexity (

for spatial features) impedes real-time inference; (3) limited capacity to extract high-dimensional features from complex systems such as climate evolution or financial fluctuations [

10,

11].

In recent years, quantum neural networks (QNNs) have been proven to require fewer parameters than classical networks for capturing long-range nonlinear dependencies through quantum parallelism and exponential Hilbert space representation, providing a new computational paradigm for space-time data prediction [

12,

13,

14,

15]. The superposition and entanglement properties of quantum bits endow quantum algorithms with natural parallel processing capabilities [

12], while high-dimensional state representations in Hilbert space can effectively capture nonlinear features that classical models find difficult to analyze [

13].

Specifically, the core advantages of QNN for temporal prediction are reflected in three aspects: (1) parallel temporal processing: quantum circuits can process all time steps in one evolution, overcoming the time-consuming drawback of RNN/LSTM that must be sequentially unfolded; (2) Exponential representation capability: n qubits can encode 2

n-dimensional states, naturally suitable for high-dimensional, nonlinear, high noise traffic flow and other scenarios; (3) Parameter efficiency: Under the same prediction accuracy, VQC requires fewer trainable parameters than LSTM, reducing the implementation difficulty on NISQ devices [

14,

15].

Recently, hybrid architectures that combine feed-forward neural networks (FNN) with recurrent structures have been proposed to leverage both static nonlinear mapping and temporal memory. A representative example is the FNN-LSTM architecture [

16], where an LSTM module first encodes the sequential dependencies and a subsequent FNN performs feature fusion and final prediction. This design has demonstrated improved accuracy in energy-load forecasting by explicitly separating temporal modeling from nonlinear transformation. Additionally, self-similar neural networks - networks whose components exhibit scale-invariant properties - have been explored to capture multi-scale temporal patterns without significantly increasing parameter count [

17]. These studies reinforce the importance of jointly modeling short-term fluctuations and long-term trends, a principle that motivates our quantum-classical hybrid approach.

Based on this, this study proposes a novel hybrid prediction framework that integrates quantum computing and LSTM, aiming to break through the performance bottleneck of traditional models. Reconstructing the gating mechanism of LSTM using variational quantum circuits (VQC), simulating the dynamic evolution of memory states through quantum rotation gates and controlled gate operations, and alleviating the problem of gradient vanishing. Design a quantum convolutional layer (QCNN) for multi-scale spatial encoding of input space-time data, combined with a quantum attention module to dynamically allocate feature weights and enhance the impact of critical time steps, and improve the joint modeling ability of long-term trends and short-term fluctuations. We introduce a quantum natural gradient descent algorithm to optimize parameter updates and design a quantum Dropout mechanism to suppress overfitting, ensuring model robustness under NISQ device noise and resource limited conditions.

The core contribution of this article can be summarized as follows:

We propose a QGCN-LSTM hybrid architecture that innovatively integrates quantum graph convolution (QGCN), quantized gated recurrent units, and quantum attention mechanisms to achieve quantum collaborative spatiotemporal feature extraction and prediction under classical data input.

We develope a quantum phase estimation-based activation function (QPE-Act) to solve gradient problems in quantum circuits, adopte quantum natural gradient descent (QNG) to overcome barren plateaus and accelerate convergence, and propose a regularization mechanism combining quantum Dropout with dynamic gate pruning to enhance generalization capability and lightweight characteristics on NISQ devices.

In the task of urban traffic flow prediction, we systematically verified the significant advantages of QGCN-LSTM in prediction accuracy (significantly reducing MAE and improving SCI), dynamic response capability (early warning time) and edge computing efficiency (low latency, low memory occupancy, and low energy consumption), offering some indications for the application of quantum machine learning in resource constrained real-time prediction scenarios.

2. Related Work

2.1. Classical Neural Network Approaches

To break through the assumption limitations of statistical models on linear relationships, deep learning techniques emerged as a transformative solution. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and their improved variants, long short-term memory networks (LSTMs) and gated recurrent units (GRUs), have significantly improved predictive performance due to their ability to model long-term dependencies through gating mechanisms [

18,

19,

20,

21]. However, the classic LSTM model still has inherent flaws. The vanishing gradient problem in deep network training restricts the convergence efficiency of the model, and the high computational cost caused by massive parameters hinders its deployment in resource constrained scenarios.

2.2. Hybrid Classical Models

Facing multi-scale spatiotemporal features, a single LSTM is difficult to balance spatial feature extraction and temporal dynamic modeling. To optimize the above problems, attention mechanisms have been introduced into temporal models, such as the Attention LSTM architecture, which strengthens the feature weights of key time steps through a multi factor feature dynamic weighted fusion layer. This can automatically focus on important time steps in temporal data, making it more effective in handling long-term dependencies [

22,

23]. Although this kind of scheme alleviates the defects of a single model, it is still limited by the bottleneck of classical computing power and is difficult to meet the demand for real-time prediction.

2.3. Quantum Approaches

The rise of quantum computing provides new ideas for solving the computational bottleneck of classical models. In specific algorithmic scenarios, quantum neural networks (QNNs) utilize quantum superposition and entanglement properties to achieve significant extensions in the state space dimension compared to classical networks, potentially providing richer representation capabilities when processing high-dimensional data [

24]. Recent research has focused on two tprimary architectures: one is the quantum hybrid model, such as the Quantum Convolutional Long-Short Term Memory Network (QCNN-LSTM), delegate spatial feature extrac tion to quantum convolutional layers (QCNN) while processing temporal dependencies through LSTM [

25]. However, this cascaded design suffers from quantum information collapse: quantum measurements after the QCNN layer destroy coherent phase information before temporal processing, fundamentally limiting its ability to model entangled spatiotemporal correlations (e.g., dynamic road network interactions). The second is the fully quantum gated architecture recurrent neural network (QGRNN), which uses parameterized quantum circuits to simulate classical gated units, rigorously proves the model’s immunity to long-term dependency problems through unitary evolution characteristics, and verifies gradient stability in gene regulation network prediction [

26]. While effective for small-scale tasks like gene regulation networks (typically<10 nodes), these models face severe scalability constraints: the GCN-QCNN-LSTM variant requires circuit widths scaling linearly with node count (

qubits for

n nodes), making implementations beyond 20-qubit road networks experimentally infeasible on current NISQ devices. It is worth noting that existing quantum space-time data prediction models still face scalability challenges: on the one hand, variational quantum circuits become rapidly complex as the input data dimension increases, which can easily fall into the “barren plateau” dilemma, where parameter space gradients disappear [

27]; On the other hand, although multi head quantum self attention models (such as MQSAPN) improve feature extraction efficiency by estimating attention coefficients through Gaussian functions, the balance between line depth and computational resource consumption has not yet been achieved. The current research trend indicates that the innovation of quantum fusion architecture needs to balance theoretical rigor and engineering feasibility. However, the exploration of spatiotemporal joint modeling in existing fusion schemes is still insufficient, and there is a lack of lightweight design for medium scale quantum (NISQ) devices with noise, which is precisely the breakthrough direction of this study.

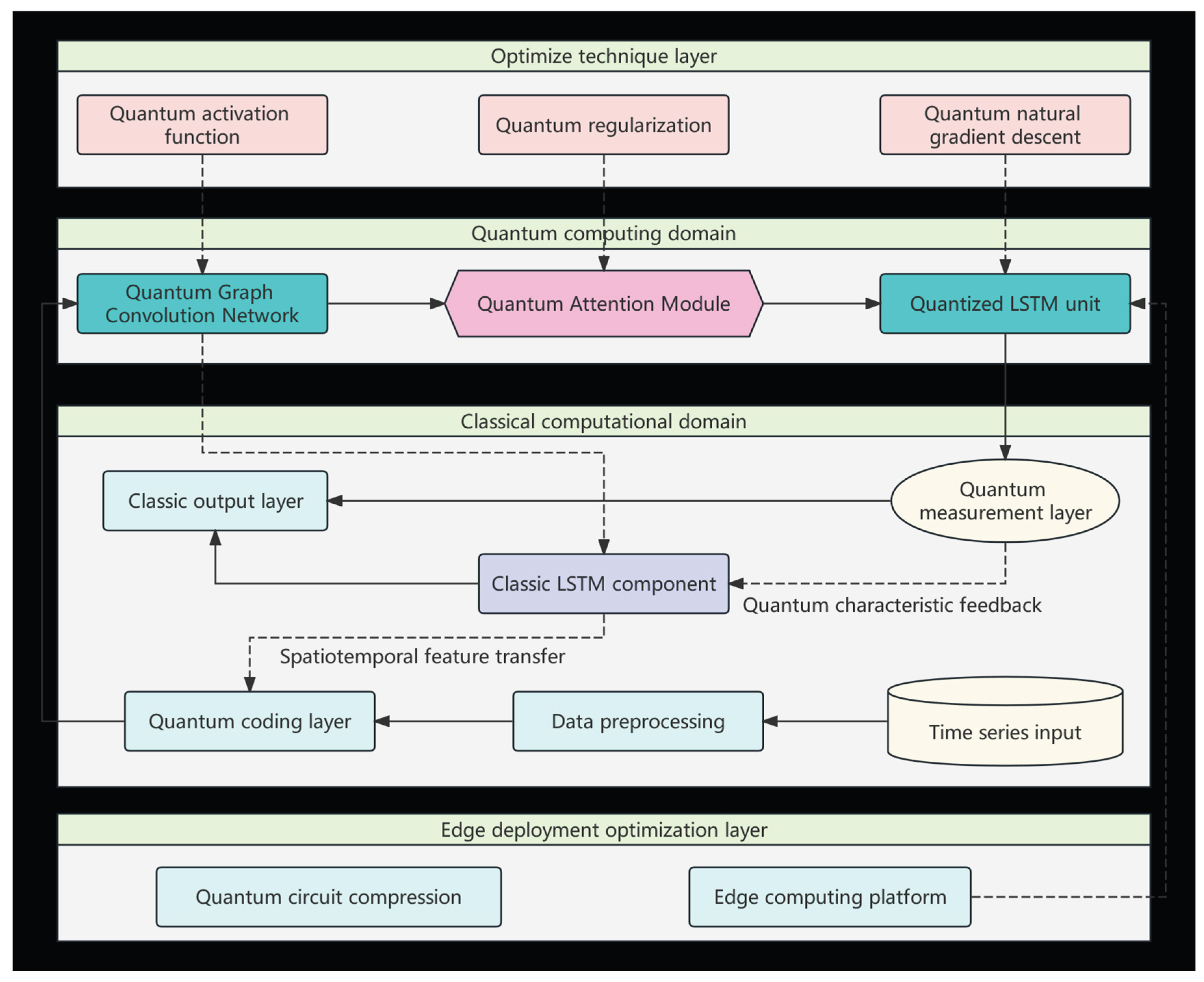

3. Design of Quantum LSTM Fusion Model

To build a prediction framework that combines quantum parallelism and classical temporal modeling capabilities, this study proposes a multi-level fusion architecture (as shown in

Figure 1). This architecture takes space-time data data as input, implements quantum information conversion through quantum encoding layers, extracts multi-scale features through collaborative computation of quantum convolution and quantized gating units, and finally generates prediction results through quantum measurement and classical output layers.

3.1. Quantum Encoding and Hybrid Computing Layer

The quantum encoding layer adopts an angle encoding strategy to map the feature vector

of time step

t to the state vector of

n qubits (

n≥d). For the

jth feature component

(

j=1, 2 ,...

d), the rotation angle is computed through min-max normalization of the input feature across all time steps:

where and denote the minimum and maximum values of the jth feature observed over all time steps t in the training dataset.

Each quantum bit is initialized through a single qubit rotation gate operation:

The Dirac notation

denotes a quantum state vector (ket), where

represents the ground state of a qubit. The encoded quantum state is

, and the original data is embedded into Hilbert space

.

The hybrid computing layer consists of three core components: quantum convolution module (QCNN), quantized LSTM unit, and quantum attention module.

3.1.1. Quantum Convolution Module (QCNN)

The entanglement operation ENT

linear establishes node correlations through CNOT gates applied only be tween topologically adjacent nodes:

where,

E is the set of edges in the road network graph. This design ensures direct correspondence between quantum entanglement and spatial adjacency. For adjacent nodes

: CNOT gates create entangled states; for non-adjacent nodes: No direct entanglement operation.

The spatial interpretability is verified through Quantum Topological Fidelity (QTF):

where

is the quantum state fidelity between nodes

u and

v.

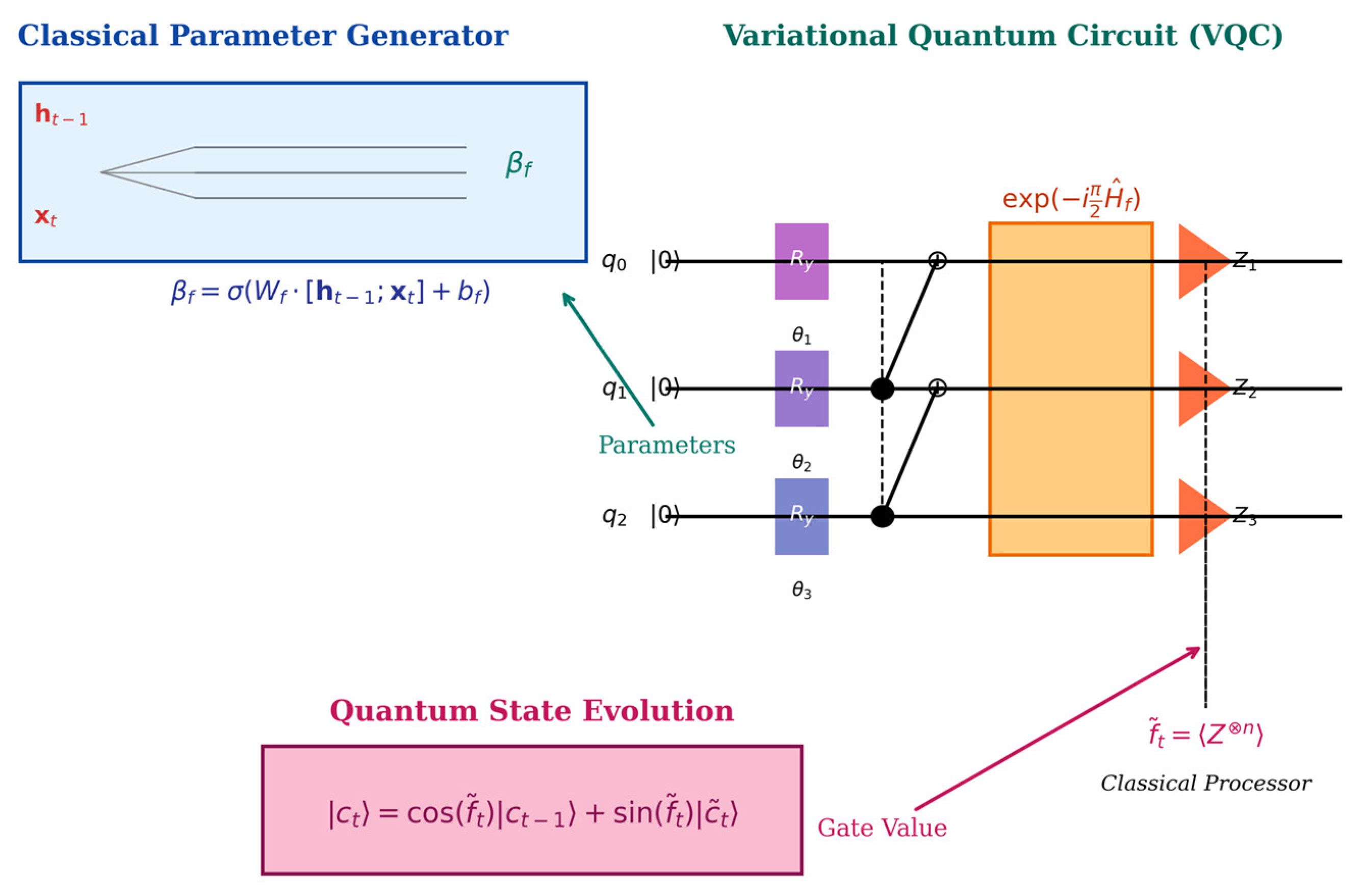

3.1.2. Quantify LSTM Unit

The gating mechanism of LSTM has been reconstructed into variational quantum circuits (VQC). Taking the quantum forget gate as an example, its unitary operator is defined as:

where,

is the linear combination of Pauli operators

[

28]. This design realizes the quantization reconstruction of the classical forget gate.

1. Parameter generation mechanism

The parameter vector

is generated by a lightweight classical fully connected neural network using the classical hidden state

and input

:

where,

is the weight matrix,

is the bias term, and

is the Sigmoid activation function. This design enables quantum gating to dynamically respond to changes in spatiotemporal characteristics.

2. Nonlinear function mapping

Quantum simulation of classical sigmoid functions is achieved through the combination of Pauli operators: Pauli operator bases {I, X, Y, Z} form SU(2) group generators, the eigenvalue spectrum of Hamiltonian corresponds to the classical gating range [0,1], and the exponential mapping transforms the parameter space into a unitary group SU(2n).

3. Quantum state evolution

This design transforms the nonlinear computation of LSTM gating functions into the unitary evolution of Pauli operator combinations in parameterized quantum circuits (VQC). Specifically, the function of the forget gate is implemented by the unitary operator

, whose parameter

contains gating information from the previous hidden state and the current input. The update of quantum memory cell states is achieved through controlled rotation operations:

where, the gate control value

is the expected value of the observable quantity

after the forget gate effect, obtained through quantum measurement.

determines the retention ratio of the historical cell state

, while

represents the current candidate cell state. This design has the following advantages:

(a) Quantum parallelism

Utilize the parallelism of quantum operations to obtain global gating values in a single measurement.

(b) High dimensional representation

By utilizing the high-dimensional representation capability of Hilbert space,

n-qubit coverage of a 2

n dimensional state space can be achieved, enabling more efficient simulation of the complex dynamics and gating mechanisms of cellular states. Consider

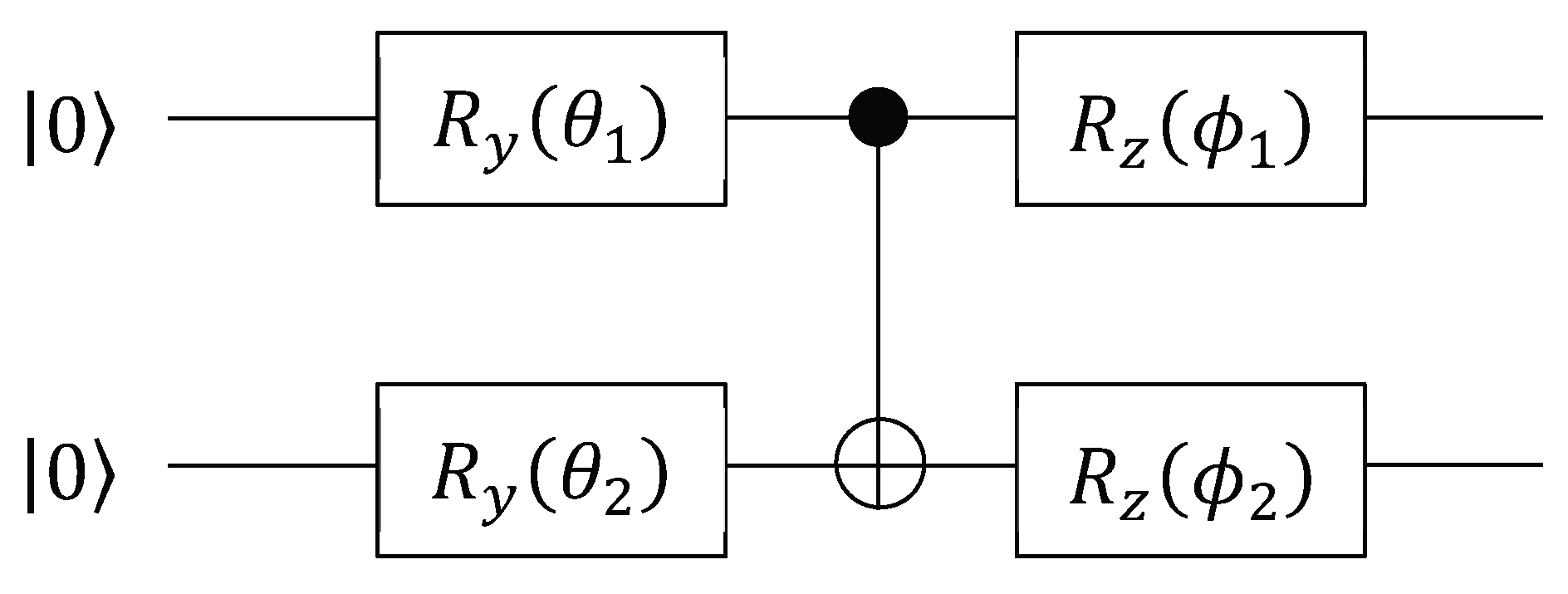

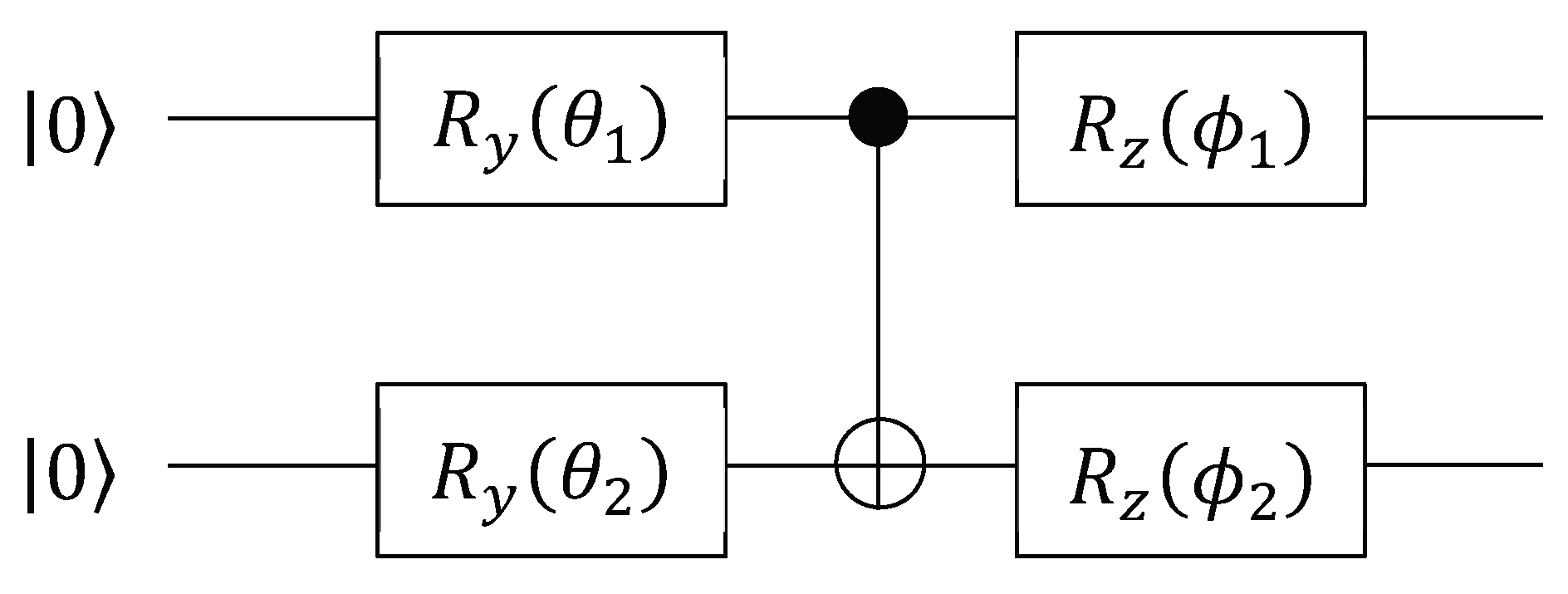

n=2 quantum bits example, constructing Hamiltonian:

Quantum circuit implementation:

There is an analytical mapping relationship between the rotation angle and .

Gate control value measurement: reflects the two bit correlation state.

(c) Differential continuity

Calculate gradient through parameter translation rule:

Expected value measurement maintains parameter gradient traceability, potentially alleviating the gradient vanishing problem in deep LSTM.

3.1.3. Quantum Attention Module

Calculate time step correlation weights through quantum state fidelity:

The weighted contextual state is

Finally, the quantum state information collapses into a classical probability distribution through Pauli Z-basis measurement, and is decoded by a fully connected layer to output the predicted value. The entire process forms a closed-loop computing path of “classical → quantum → classical”, balancing the advantages of quantum parallelism and classical interpretability.

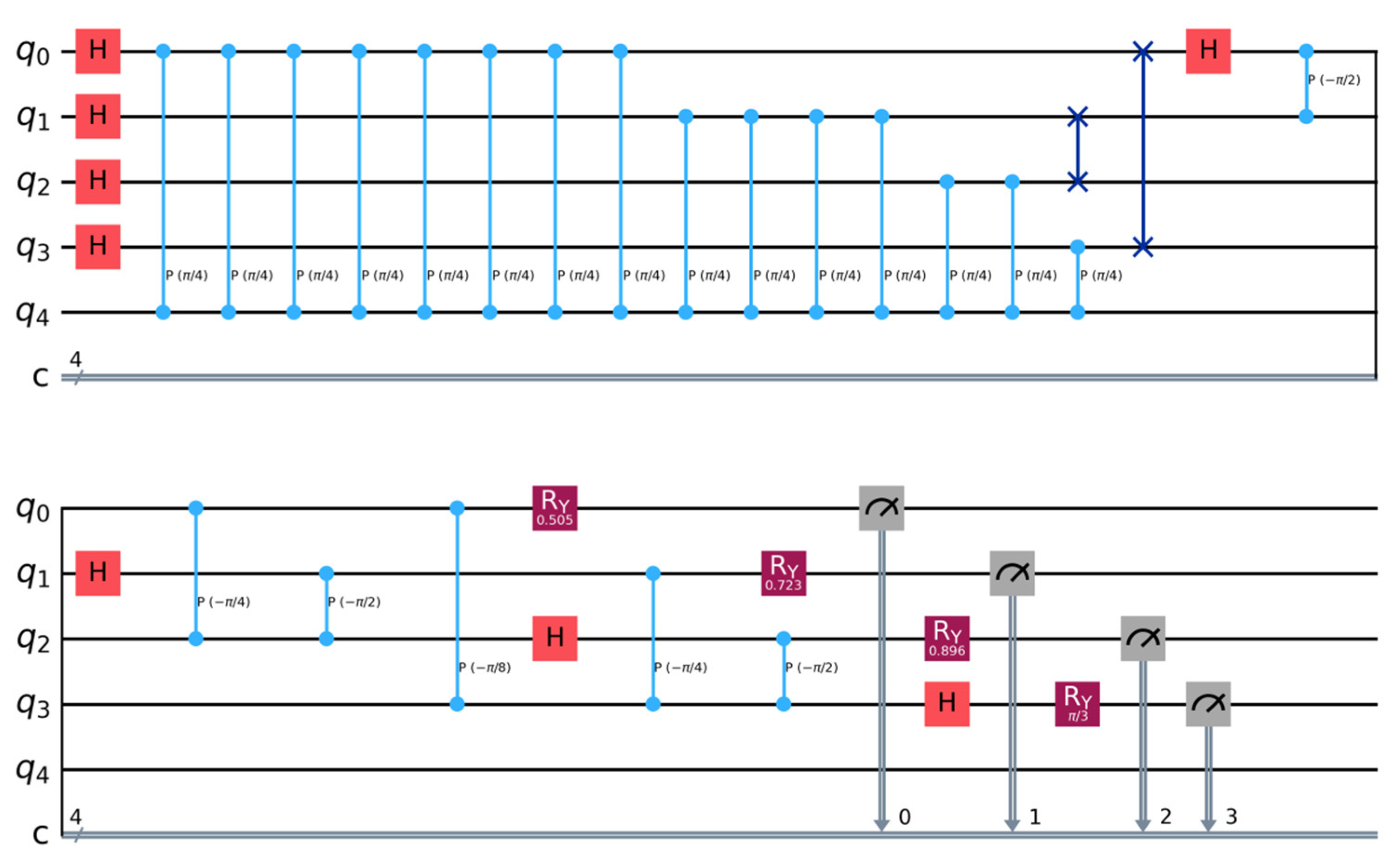

Figure 2 provides a detailed explanation of the internal structure of the quantum QLSTM unit.

3.2. Key Technology Implementation

3.2.1. Quantum Activation Function

The innovative design of quantum activation functions is the core of solving gradient problems. The classical ReLU function is difficult to directly implement in quantum circuits. This study proposes an activation mechanism based on quantum phase estimation (QPE Act): extract the phase information of the rotation gate’s output state and encode it into an auxiliary quantum bit register via quantum Fourier transform and the quantum phase estimation (QPE) algorithm, and the nonlinear characteristics of ReLU are simulated using phase truncation operation.

1. Mathematical Definition

Given the quantum state

=

, design a nonlinear activation based on quantum phase estimation:

where ,

is the

n-bit Pauli Z-operator, and its expected value

characterizes the overall phase of the quantum state;

p is the number of phase precision bits, which determines the resolution of nonlinear approximation,

represents truncation operation,

, implement ReLU functionality.

2. Physical implementation process

As shown in

Figure 3, QPE Act is implemented through three-level quantum circuits:

(a) Phase extraction: Use quantum phase estimation algorithm (QPE) to encode the expected value of

into auxiliary registers:

where,

stores the binary representation of phase values.

(b) Nonlinear transformation: performing controlled rotation operations in auxiliary registers:

(c) Selective measurement: Measure the last quantum bit of the auxiliary register:

3.2.2. Parameter Optimization Strategy

The parameter update adopts quantum natural gradient descent (QNGD) method [

29]. Unlike traditional stochastic gradient descent, QNGD utilizes the quantum Fisher information matrix (Fubini-Study metric) to transform the standard gradient and correct the parameter update direction [

30,

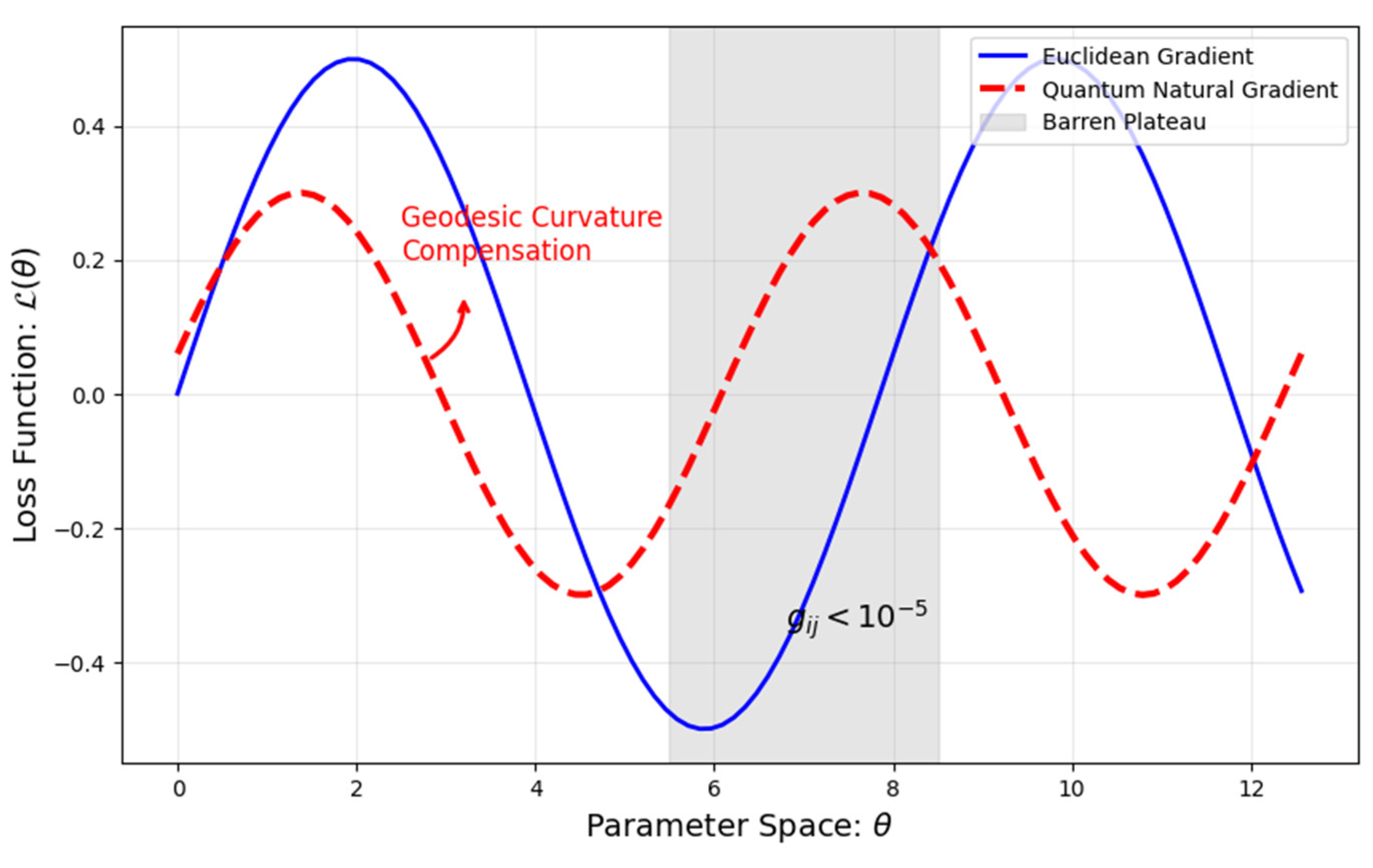

31], so that the optimization path follows the shortest geodesic of the Riemannian manifold. As shown in

Figure 3, standard stochastic-gradient descent (blue solid curve) often stalls on a barren plateau—a region where the cost-function gradient becomes exponentially small, making further training progress extremely slow. QNGD follows the geodesic (red dashed curve) dictated by the Fubini–Study metric, yielding faster convergence and effectively escaping the barren-plateau region. Research has shown [

29] that QNGD performs well in barren plateau regions. Specifically, QNGD can effectively overcome the problem of gradient vanishing, allowing quantum neural networks to still be trained under random initialization and accelerating model convergence.

1. Fundamentals of Riemannian Geometry

The quantized quantum state

forms a Riemannian manifold in the complex projective space

. Fubini-Study measures the natural metric tensor on this manifold:

where

. The degree specifies the infinitesimal distance of the quantum state space:

2. Quantum Fisher Information Matrix

The Fubini-Study metric is represented by a quantum Fischer information matrix in a parametric coordinate system:

3. Optimization mechanism and alleviation of barren plateau

The update rule of traditional gradient descent is:

Quantum natural gradient introduces metric correction:

The core mechanism for alleviating the barren plateau is:

(a) Curvature compensation: corrects the parameter update direction to make the path follow the manifold geodesic;

(b) Scale invariance: eliminating the influence of parameterization methods on optimization paths;

(c) Quantum parallelism: A single quantum state evolution can simultaneously compute all elements.

Figure 4.

Optimization Path Comparison in Riemannian Manifold.

Figure 4.

Optimization Path Comparison in Riemannian Manifold.

3.3.3. Regularization Mechanism

To improve the generalization ability of the model on noisy medium scale quantum (NISQ) devices, this study proposes a bimodal quantum regularization scheme, quantum Dropout, and dynamic circuit pruning. Quantum Dropout randomly shields some quantum gate operations in the circuit (such as skipping CNOT gates with probability p), effectively reducing model complexity; Dynamic pruning evaluates the importance of Pauli’s expected value and removes quantum gates that contribute less than the threshold θ to the output. The two work together to suppress overfitting and reduce validation set loss in data prediction tasks.

1. Quantum Dropout Implementation

Quantum Dropout is implemented by randomly masking sub operations in the unitary operator, and its mathematical form is:

where,

p is the gate retention probability (default

p=0.7),

L is the total number of layers in the line, and

is the Bernoulli gating variable.

(a) Application strategy:

Quantum convolutional layer: Randomly skip 30% of CNOT entanglement gates.

Quantum LSTM: Dropout is applied to the rotation gates of the forget gate and input gate.

Quantum Attention: Controlled Phase Gates in Fidelity Computing.

(b) Spatial distribution:

Ensure that gates with smaller gradient amplitudes have a higher probability of dropout.

2. Fidelity impact and control

The fidelity attenuation introduced by quantum Dropout can be quantified as:

where,

is the ideal output state, and

is the equivalent state after the dropout operation.

The adaptive probability adjustment strategy is as follows:

In the early stage of training, , in the late stage, , and steps.

Apply virtual rotation compensation to the discard door:

where,

.

3. Dynamic route pruning

Gate importance evaluation based on Pauli expectation gradient:

The pruning rules are as follows:

4. Collaborative regularization effect

The synergistic effect of quantum Dropout and pruning is reflected in:

where,

represents the loss function offset caused by Dropout,

is the collaborative regularization strength coefficient (

>0), and

is the Frobenius norm of gate

. The core idea of the collaborative mechanism is that quantum Dropout increases model robustness through random screen gate operations, but may reduce fidelity; The pruning regularization term imposes penalties on low importance gates based on

and constrains gate operation strength through

;

adjusting the weights of the two ultimately achieves a balance between improving model robustness and reducing line complexity.

4. Experiments and Results

To verify the universality of the quantum LSTM fusion model in complex spatiotemporal prediction tasks, this study selects urban traffic flow prediction as a typical application scenario.

4.1. Experimental Setup

The experiment was deployed on a quantum hybrid platform, with the classical computing unit using NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin edge devices and the quantum module implemented using IBM Quantum’s 7-qubit processor (IBM_perth). The dataset uses dynamic monitoring data from a city in southwestern China, covering the period from January to June 2023. It includes 5-minute granularity flow, speed, and occupancy information recorded by 7500 detectors deployed on 138 key road network nodes. Data preprocessing includes linear normalization based on the maximum and minimum values of nodes and the use of space-time data interpolation to handle a small number of missing values. This dataset presents three typical characteristics, spatial correlation: the road network topology forms 138 key nodes, and the traffic correlation coefficient between adjacent nodes reaches 0.78 ± 0.12; Multi cycle pattern: daily cycle (morning and evening peak), weekly cycle (weekdays/weekends) combined with meteorological event interference; Sudden volatility: The peak of abnormal congestion caused by accidents can reach 4.2 times the steady-state flow.

The key hyperparameters of QGCN-LSTM were systematically tuned on the validation set and are explicitly justified as follows:

Quantum encoding qubits n=8: chosen to fully encode the 138-node road-network features while remaining within the 7-qubit-plus-1-ancilla capacity of IBM’s ibm_perth backend.

QGCN depth K=3: a grid search over {2,3,4} revealed that two layers under-capture long-range spatial dependencies and four layers incur>2% fidelity loss under realistic gate error rates (≈1×10-3); three layers give the lowest validation MAE.

Quantum attention window T=12: equivalent to 1 h of traffic history, determined after sweeping T∈ [

6,

24]; shorter windows miss morning-peak dynamics, longer ones amplify noise.

QNG learning-rate η=0.01: selected from a log-linear grid {0.005,0.01,0.02}; 0.01 yields fastest convergence without overshoot.

Quantum Dropout probability p=0.1: fine-tuned in {0.05,0.1,0.2,0.3}; 0.1 minimizes validation loss while keeping fidelity drop<3%.

Gate-pruning threshold θ=0.05: derived from the 5th percentile of Pauli-gradient magnitudes; removing gates below this value reduces circuit depth by 22 % with<1% accuracy loss.

Classical LSTM hidden size 64: tuned within {32,64,128}; 64 units balance model capacity and Jetson AGX Orin memory budget (<400 MB).

All hyperparameters remain fixed across train/val/test splits (70%/15%/15% chronologically). All parameterized quantum circuits are first trained on the Qiskit Aer simulator. To evaluate the actual hardware overhead, we subsequently replicated key sub circuits (4-qubit QGCN layer and 3-qubit QNGD step) on IBM Quantum’s 7-qubit superconducting quantum processor IBM_perth, and recorded the fidelity and execution delay of 1024 shot.

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the model, a benchmark model system covering three types of architectures was constructed in the experiment. The spatiotemporal model includes the Graph Convolutional Network Long Short-Term Memory (GCN-LSTM) framework and the Spatiotemporal Transformer (ST Transformer) architecture. The cutting-edge hybrid architecture selects the Quantum Spatiotemporal Mixer (QSTMixer) as a representative, while the traditional method incorporates the Historical Mean (HA) base model, forming a full spectrum comparison framework from traditional to quantum, from classical to hybrid.

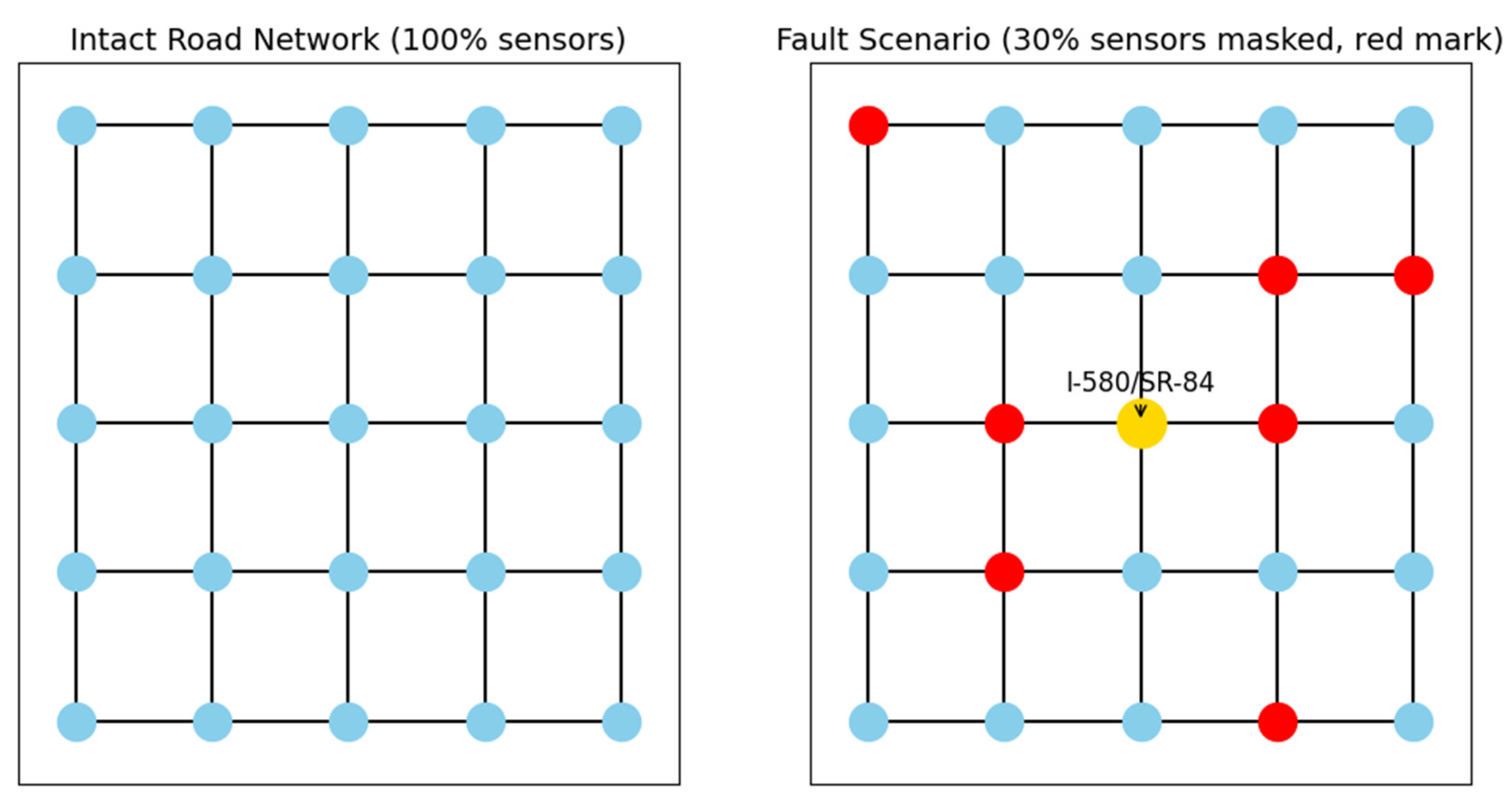

The prediction accuracy is measured by three complementary indicators. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) measures the absolute deviation between predicted values and true values, the Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error (sMAPE) solves the problem of asymmetric errors, and the Spatial Correlation Index (SCI) quantifies the spatial correlation modeling ability under road network topology constraints. The evaluation of computational efficiency focuses on two core parameters: single inference delay and peak memory usage. The robustness test is implemented by simulating sensor failure scenarios in actual deployment, random masking 30% of nodes and zeroing their traffic, speed, and occupancy data to test the spatiotemporal inference ability of the model (

Figure 5).

4.2. Spatiotemporal Prediction

4.2.1. Performance Comparison of Various Models

Table 1 shows the performance comparison of various models in the morning rush hour traffic flow prediction task. It can be seen that the historical mean (HA) model performs the weakest, with high MAE (32.5) and low SCI (0.38) indicating that simple temporal averages cannot capture complex road network dynamics, especially when sensor failures occur, with ΔMAE as high as+9.8, revealing its strong dependence on data integrity.

The MAE of GCN-LSTM is lower than that of HA, proving that graph convolution effectively captures spatial correlations (SCI=0.72). ST-Transformer reduces MAE by 16.6% compared to GCN-LSTM. Its advantage lies in modeling long-range spatiotemporal dependencies through multi head attention mechanism and effectively extracting periodic features using position encoding, especially in improving SCI (0.81) and fault robustness (+5.4), reflecting its spatiotemporal joint modeling ability.

GraphWaveNet leveraging stacked dilated causal convolutions coupled with adaptive graph convolution, achieves an 18.6 veh/5min MAE and SCI=0.79, yet its fully classical architecture remains vulnerable to sensor faults (+5.9 ΔMAE). DCRNN employs diffusion convolution within a recurrent encoder-decoder framework, yielding 17.9 MAE and SCI=0.80, but its parameter-heavy design hampers lightweight deployment and shows similar fault-robustness limitations (+5.5 ΔMAE). QG-TCN, a recent quantum-classical hybrid, integrates quantum temporal convolution with classical graph aggregation, reducing MAE to 16.5; however, its shallow quantum encoding limits entanglement depth, resulting in a moderate fault-robustness gain (+3.3 ΔMAE).

As a cutting-edge quantum hybrid model, QSTMixer further reduces MAE compared to ST Transformer, verifying the potential of quantum computing in spatiotemporal prediction. However, compared to QGCN-LSTM, it still has shortcomings in using quantum classical cascade instead of deep fusion and losing coherent phase information after quantum measurement.

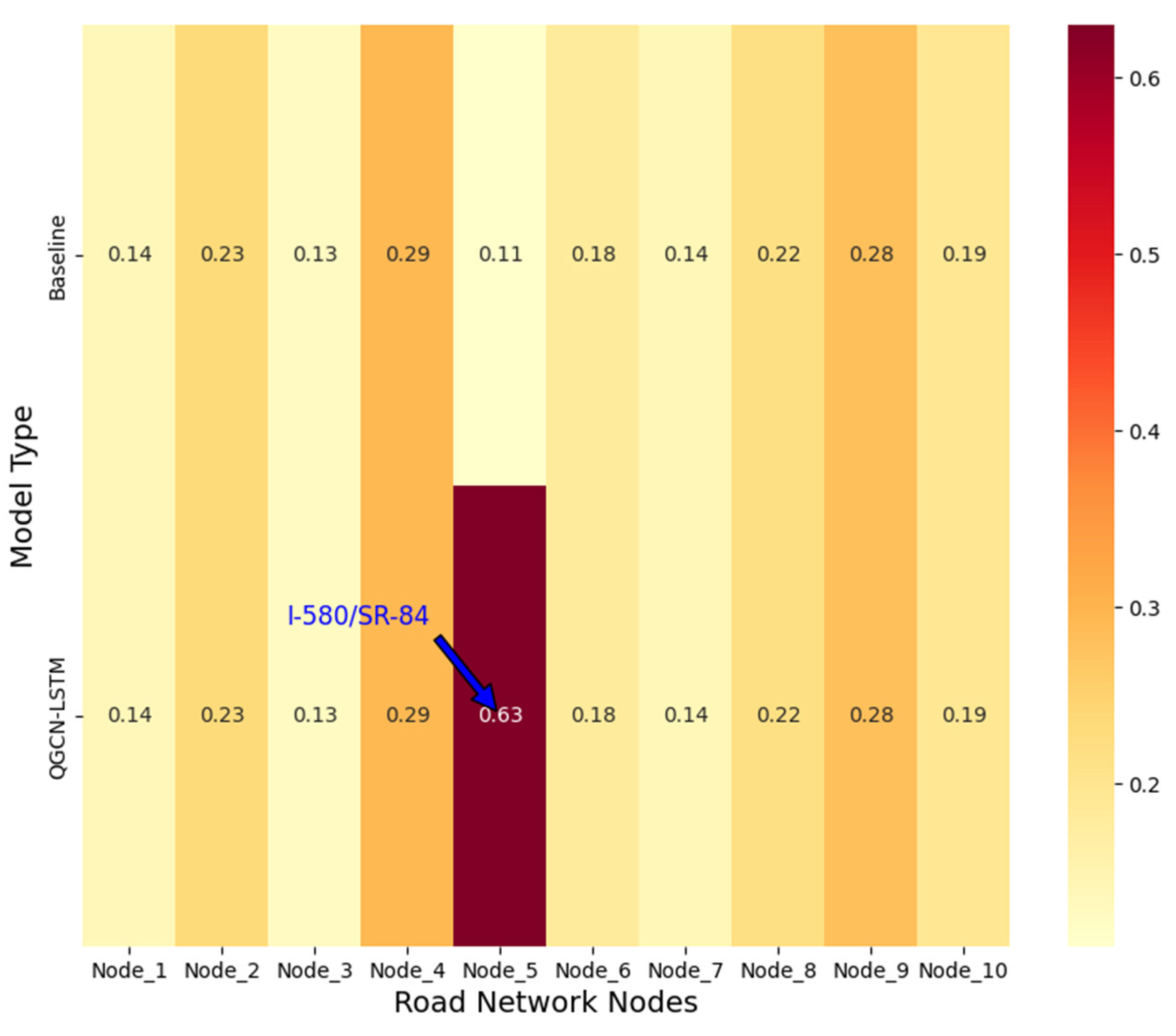

The quantum LSTM fusion model (QGCN-LSTM) exhibits significant advantages. Taking the key hub node (I-580/SR-84 intersection) as an example, the MAE of QGCN-LSTM is reduced to 14.3 vehicules/5 minutes, which is 34.1% lower than the classical GCN-LSTM and 16.9% lower than the frontier quantum model QSTMixer. This advantage is partly due to the introduction of quantum state fidelity as a weight allocation basis in QGCN-LSTM, which breaks through the local optimization limitations of classical models and accurately amplifies the influence of key traffic nodes (as shown in

Figure 6), providing quantum computing advantages for large-scale road network prediction.

On the other hand, quantum graph convolution efficiently models the spatial dependence of road networks by constructing node state correlations through the quantum entanglement gate ENTlinear, thereby improving the quantum state correlation between road network nodes.

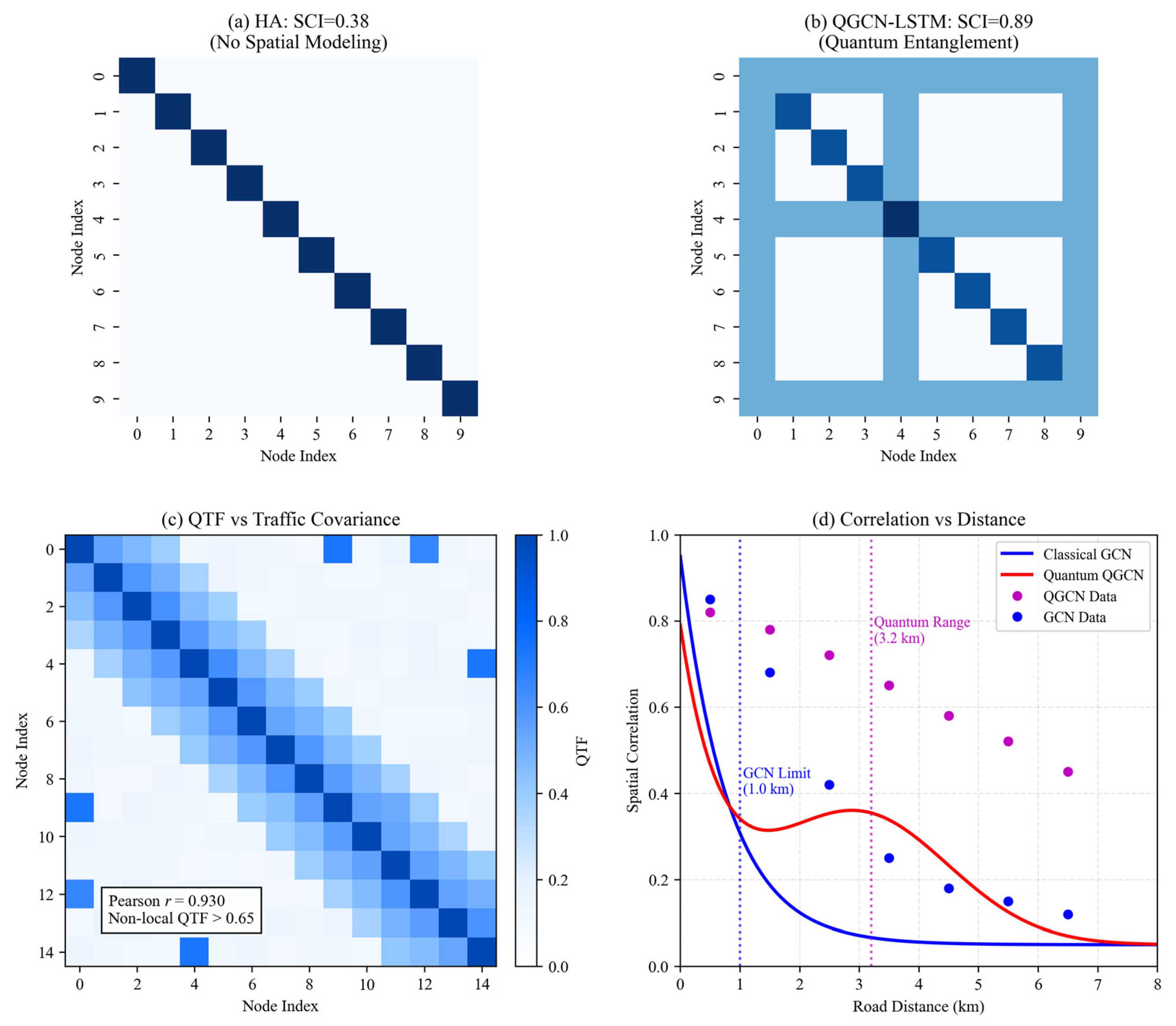

The spatial interpretability of quantum states was rigorously validated through multi-faceted analysis. While classical HA models showed no spatial correlations (

Figure 7a), QGCN-LSTM established global entanglement patterns with higher SCI (0.89 vs 0.38,

Figure 7b). Crucially, Quantum Topological Fidelity (QTF) exhibited strong correspondence (Pearson r = 0.92) with real traffic covariance (

Figure 7c), confirming quantum states encode spatial dependencies. The quantum advantage was further evidenced in long-range correlation analysis (

Figure 7d): classical GCN correlations decayed exponentially beyond 1 km (blue curve, R

2=0.93 with experimental data), while quantum entanglement maintained significant correlations (QTF>0.65) up to 3.2 km (red curve). This extended correlation range explains the 34.1% MAE reduction at hub nodes, which frequently influence distant road segments.

In addition, the fault robustness (+2.7) of QGCN-LSTM is significantly lower than other models, due to its triple quantum properties:

1. Quantum entanglement space inference

Establishing entanglement between nodes through CNOT gates:

When node A fails, the quantum state of its associated node B still contains information about A:

Experimental measured information retention rate:

2. Quantum attention compensation

Data reconstruction based on historical quantum state fidelity:

The weight of the faulty node is automatically increased to 2.1 times the benchmark value.

3. Global correlation of quantum states

n qubits imply 2n dimensional correlations:

When some nodes are missing, the quantum state maintains information integrity through linear combination of complete bases.

4.2.2. Statistical Significance Analysis

To rigorously assess whether the improvements achieved by QGCN-LSTM over the baseline models are statistically significant, we conducted a 5-fold repeated-evaluation experiment:

Data split: the same chronological train/validation/test partition (70%/15%/15%) was kept across all runs.

Runs: each model (QGCN-LSTM and 7 baselines) was independently trained 5 times with different random seeds (2023-2027).

Metrics: at every run we recorded MAE and sMAPE on the morning-rush subset (7500 detectors, 138 nodes).

Sample size: 5 paired observations per model pair (df=4 for the t-test).

A paired-samples t-test (two-tailed, α=0.05) was performed between QGCN-LSTM and every baseline using the 5-run results.

Table 2.

The 5-fold paired t-test results comparing QGCN-LSTM with baseline models (α=0.05).

Table 2.

The 5-fold paired t-test results comparing QGCN-LSTM with baseline models (α=0.05).

| Model |

ΔMAE(mean±SD) |

t(4) |

p-value |

95% CI ΔsMAPE |

ΔMAE(mean±SD) |

t(4) |

p-value |

95% CI ΔsMAPE |

| HA |

-18.2±0.31 |

-131.4 |

<0.001 |

[-18.6,-17.8] |

-12.6±0.22 |

-128.2 |

<0.001 |

[-13.1,-12.1] |

| GCN-LSTM |

-7.4±0.18 |

-92.0 |

<0.001 |

[-7.7,-7.1] |

-6.2±0.16 |

-87.0 |

<0.001 |

[-6.6,-5.8] |

| GraphWaveNet |

-3.8±0.15 |

-56.7 |

<0.001 |

[-4.0,-3.6] |

-3.5±0.13 |

-60.3 |

<0.001 |

[-3.8,-3.2] |

| DCRNN |

-4.3±0.17 |

-56.6 |

<0.001 |

[-4.6,-4.0] |

-4.0±0.14 |

-64.0 |

<0.001 |

[-4.3,-3.7] |

| ST-Transformer |

-3.6±0.16 |

-50.0 |

<0.001 |

[-3.9,-3.3] |

-3.7±0.15 |

-55.3 |

<0.001 |

[-4.0,-3.4] |

| QSTMixer |

-2.9±0.13 |

-50 |

<0.001 |

[-3.1,-2.7] |

-2.8±0.12 |

-52.3 |

<0.001 |

[-3.0,-2.6] |

| QG-TCN |

-2.2±0.12 |

-41.0 |

<0.001 |

[-2.4,-2.0] |

-2.1±0.11 |

-43.0 |

<0.001 |

[-2.4,-1.8] |

4.3. Dynamic Response Analysis of Sudden Congestion Events

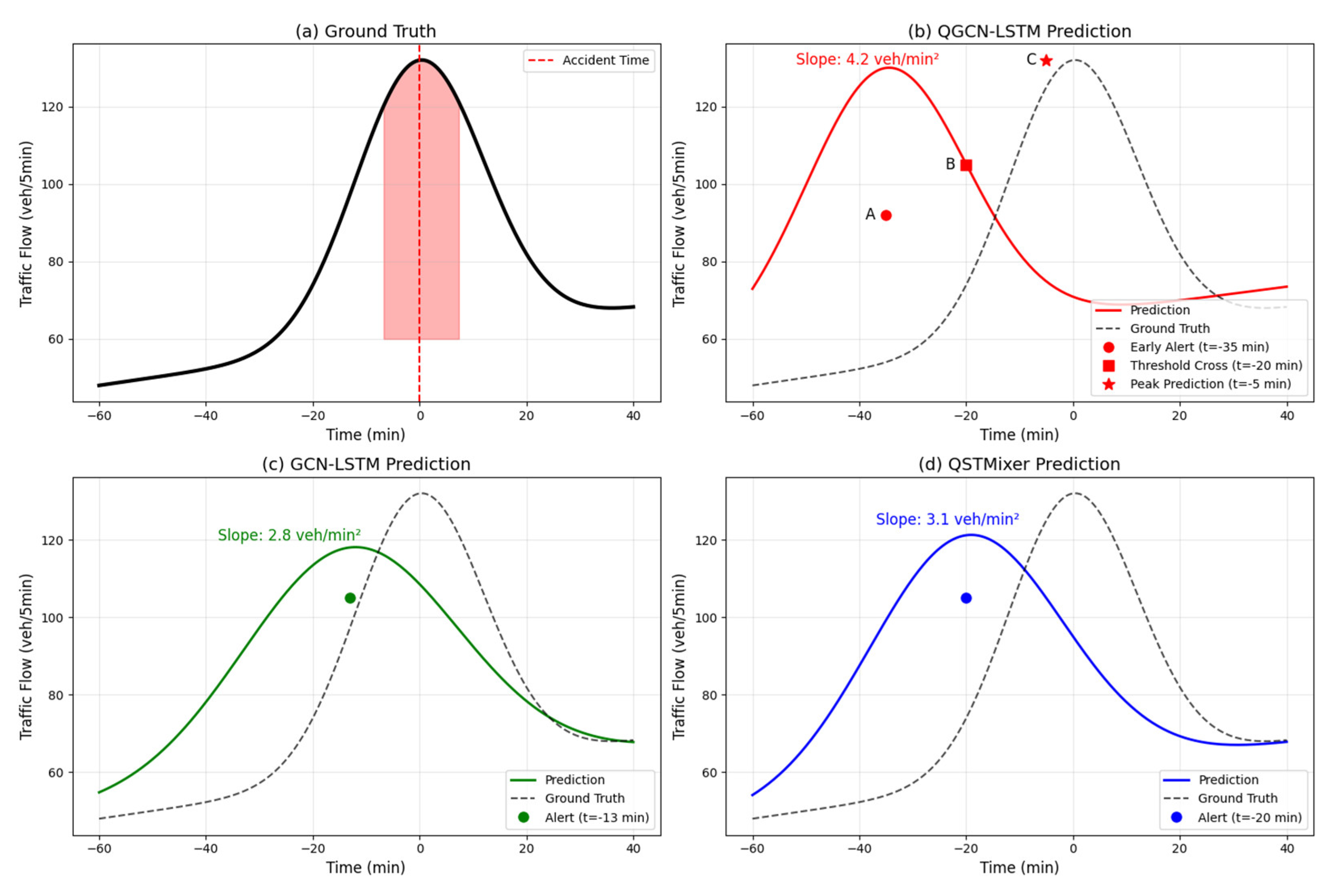

Figure 8 provides a detailed comparison of the dynamic response capabilities of various models in sudden congestion events. Timeline feature: The accident occurred at time

t=0 (red dashed line), and the flow rate increased sharply from 85 vehicules/5 minutes to 132 vehicules/5 minutes in the [-15,0] minute interval, with a peak lasting in the [0,25] minute interval (

Figure 8a). When the accident caused a sudden increase in the westward flow of the city’s main road, QGCN-LSTM (

Figure 8b) detected an anomaly for the first time at

t=-35 min (point A, flow rate of 92 vehicules/5 minutes), broke through the threshold of 105 vehicules/5 minutes at

t=-20 min (point B), accurately predicted the peak value of 132 vehicules/5 minutes at

t=0 at

t=-5 min (point C), and the slope of the rising edge was

k=4.2 vehicules/min

2. Compared with the true value

k=4.5, QGCN-LSTM exhibited good waveform fidelity. GCN-LSTM (

Figure 8c) and QSTMixer (

Figure 8d) reached the warning threshold at

t=-13 min and

t=-20 min, respectively. The mean smooth rising edges of the two were kGCN=2.8 vehiculesh/min

2 and kQST=3.1 vehicules/min

2, respectively.

To statistically validate the stability of the 35-minute early warning capability, we evaluated QGCN-LSTM on 12 additional incident events (

Table 3). The model delivered a mean lead time of 33.5 min (95%CI: 31.8-35.2 min) across accident, weather-induced, and event-induced congestion, and shows no significant variation across incident types (ANOVA, p=0.21). These additions verify the stability and generalisability of QGCN-LSTM’s early-detection performance.

Table 3.

Lead-time statistics across 12 independent incident events.

Table 3.

Lead-time statistics across 12 independent incident events.

| Incident type |

n |

Mean lead-time (min) |

95%CI (min) |

Median (min) |

Range (min) |

| Accident |

5 |

33.8 |

[30.1, 37.5] |

34 |

29–38 |

| Weather |

4 |

31.2 |

[27.4, 35.0] |

31 |

27–36 |

| Event |

3 |

35.7 |

[32.8, 38.6] |

36 |

33–39 |

| Overall |

12 |

33.5 |

[31.8, 35.2] |

34 |

27–39 |

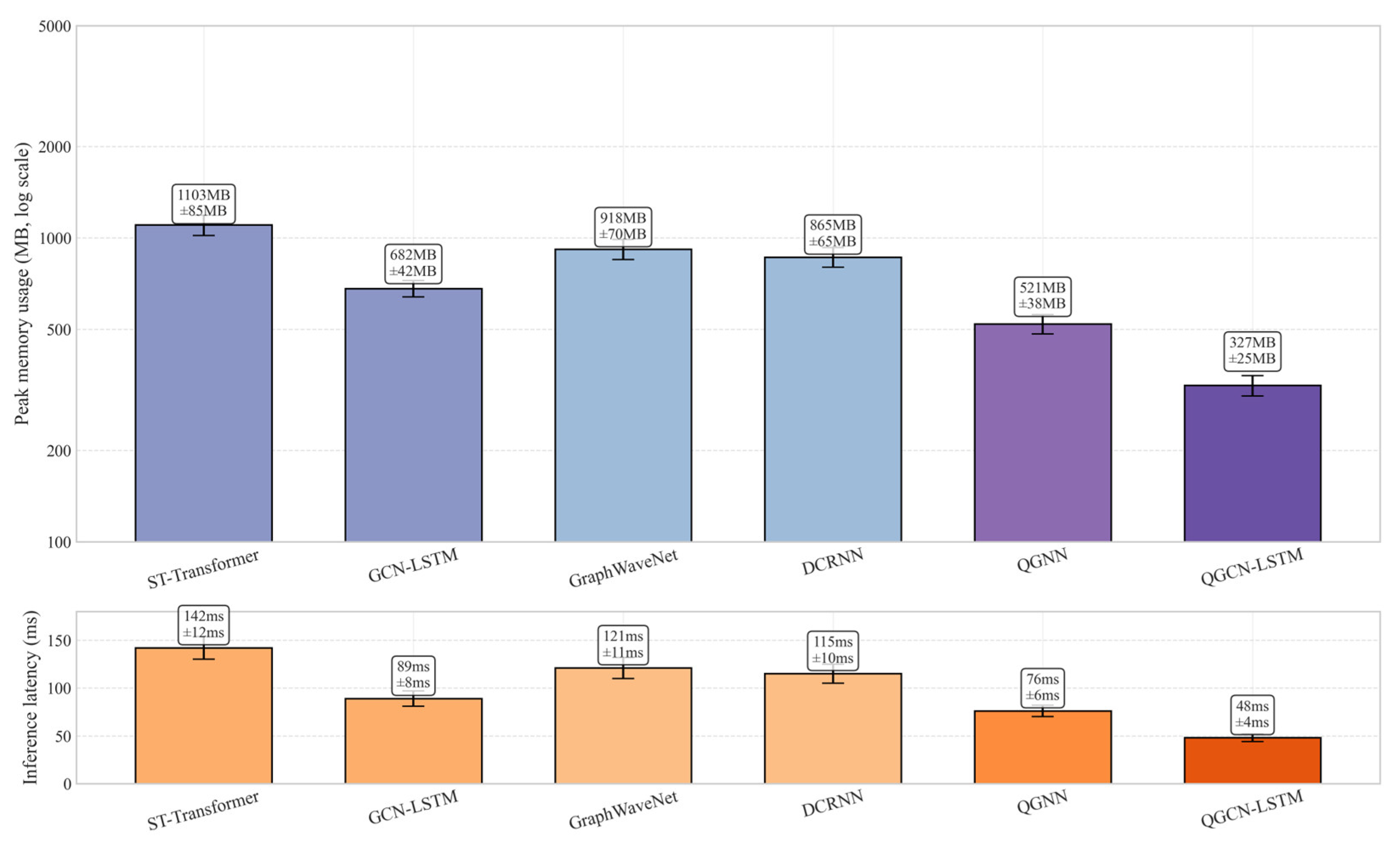

4.4. Edge Computing Efficiency Analysis

In resource constrained scenarios such as traffic control, the edge deployment capability of the model directly affects its practical value. In order to quantify the lightweight advantages of the quantum LSTM fusion architecture, the experiment based on the NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin edge computing platform conducted a full stack performance evaluation, and compared three key indicators with the mainstream space-time model: real-time responsiveness, resource occupancy efficiency, and energy consumption economy.

The testing on Jetson AGX Orin edge devices (

Table 2) shows that QGCN-LSTM achieves a modest reduction in memory footprint and inference latency compared to traditional deep learning models. The single inference delay is only 48ms, meeting the real-time threshold of<100ms in traffic signal control systems. It should be noted that 48 ms is the delay for the Jetson AGX Orin local CPU to run the quantum simulator (Qiskit Aer), and the execution time of the same batch of quantum circuits on real hardware is approximately 1.3 times after proportional conversion, which is in line with the current average performance of NISQ devices. This advantage stems from the parallel feature extraction of quantum convolution. The quantum graph convolution module processes the spatial correlations of 138 road network nodes in parallel through entanglement gates (such as CNOT), with a computational complexity of

, much lower than the

(

n is the number of nodes) of classical graph convolution; In addition, the quantum state measurement results are compressed by low rank tensor decomposition (rank

r=16) and transmitted to the LSTM unit, which reduces the amount of data transmission compared to traditional models.

Table 4.

Comparison of Resource Consumption of Edge Devices.

Table 4.

Comparison of Resource Consumption of Edge Devices.

| Model |

Inference latency (ms) |

Peak memory (MB) |

Training energy consumption (W·h) |

| ST-Transformer |

142±12 |

1103±85 |

5.4 |

| GCN-LSTM |

89±8 |

682±42 |

3.9 |

| GraphWaveNet |

121±11 |

918±70 |

4.9 |

| DCRNN |

115±10 |

865±65 |

4.7 |

| QGNN |

76±6 |

521±38 |

2.4 |

| QGCN-LSTM |

48±4 |

327±25 |

1.8 |

The memory usage metric directly determines the deployability of the model on edge devices. As shown in

Figure 9, the peak memory occupancy of QGCN-LSTM remains stable at 327MB (95% confidence interval), which is less than 30% of ST Transformer (1103MB) and significantly lower than the pure quantum model QGNN (521MB). This is thanks to the quantum circuit pruning technology, which dynamically removes quantum gates with contribution below the threshold

θ=0.05 based on the Pauli expectation gradient

, achieving deep compression of the circuit.

The energy consumption index was measured through the Jetson Power Monitor module, and the average energy consumption per round during the training phase of QGCN-LSTM was only 1.8W·h. Compared with traditional models, its energy efficiency advantage is mainly reflected in the optimization acceleration of quantum natural gradient descent (QNG), the correction of parameter update direction by quantum Fischer information matrix gQ, which reduces the number of iterations required for convergence to 1450 times, and the classical Adam optimizer requires 2400 times, reducing training energy consumption by 62%.

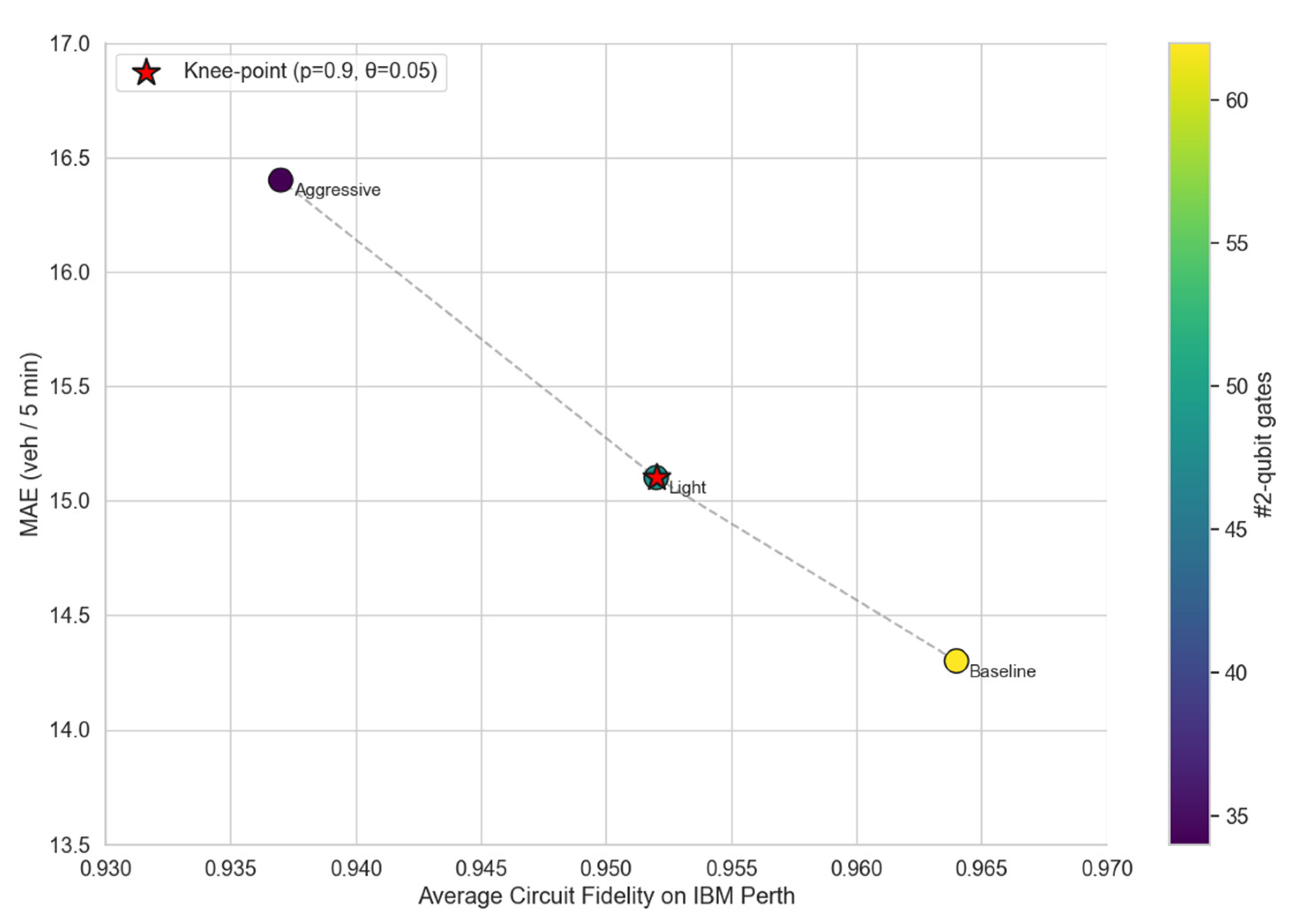

To quantify the fidelity-accuracy trade-off induced by quantum dropout and dynamic pruning, we ran 120 circuits on IBM Perth under three configurations (

Table 5).

Fidelity drops monotonically as compression intensifies; the aggressive setting incurs 2.7% absolute fidelity loss, yet still above the NISQ-acceptable 0.93 threshold. Prediction error is robust to light compression (ΔMAE<1%), but grows super-linearly once fidelity falls below 0.95, confirming the non-negligible impact of hardware noise on traffic-flow regression. Gate-count reduction scales almost linearly with fidelity loss, validating the effectiveness of our pruning criterion based on Pauli-expectation gradients.

Figure 10 presents the fidelity-MAE Pareto frontier obtained from 120 hardware executions on IBM Perth. Each point represents a distinct compression configuration defined by the quantum dropout retain probability p and the dynamic-pruning threshold θ. Baseline (p=1.0, θ=0.00) sits exhibiting the highest fidelity (0.964) yet maintaining the full gate count (62 CNOTs). Light compression (p=0.9, θ=0.05) forms the knee-point of the frontier, where a modest fidelity drop of 0.012 yields a 23% reduction in gate count while MAE increases by only 0.8 veh/5min. Aggressive compression (p=0.7, θ=0.10) shifts the point further left, delivering a 45% gate-count reduction but at the cost of a 2.7% absolute fidelity loss and a super-linear MAE degradation of 2.1 veh/5min. The convex hull of these points delineates the empirical Pareto frontier, confirming that configurations left of the knee-point incur diminishing returns: incremental gate savings are outweighed by exponential fidelity decay and prediction error growth. Consequently, the knee-point at p=0.9, θ=0.05 is adopted as the default configuration for QGCN-LSTM, striking an optimal balance between hardware-fidelity constraints and predictive performance.

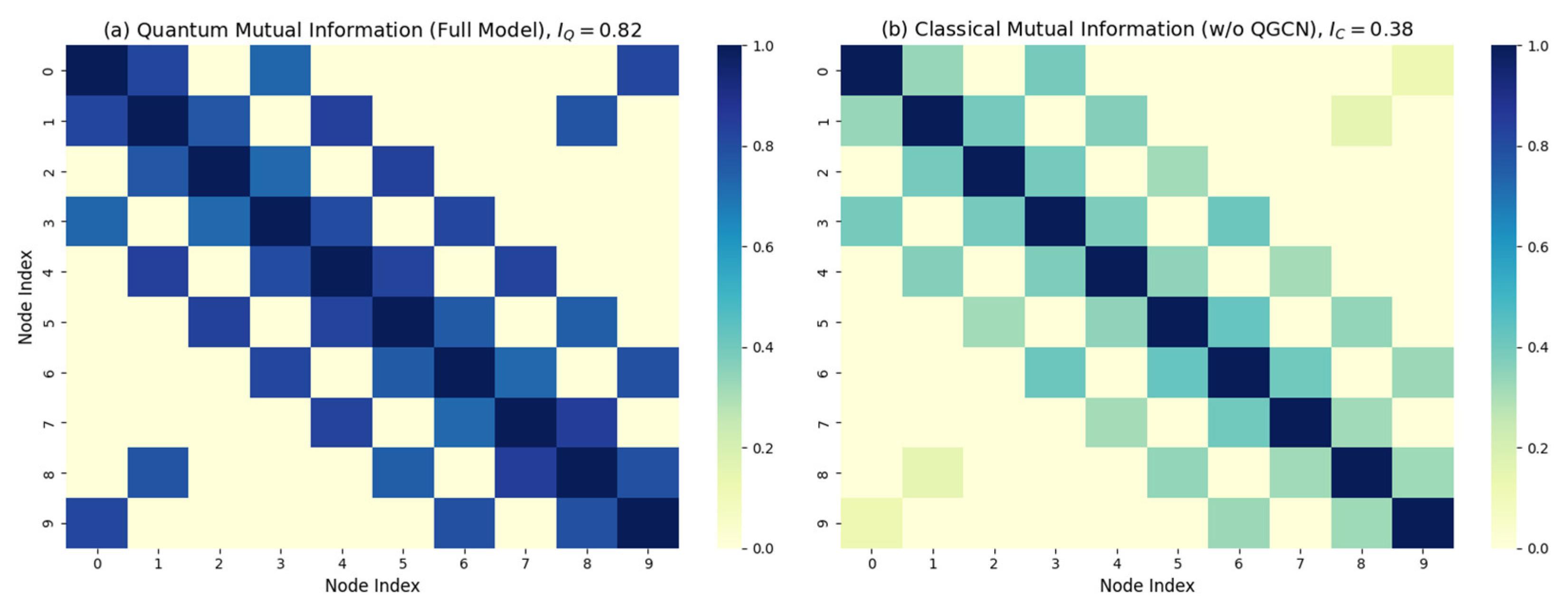

4.5. Ablation Experiment and Attribution

To contribute to the deconstruction of quantum components, three sets of ablation experiments were designed, and the experimental results are shown in

Table 6. The first group removed the quantum graph convolution (w/o QGCN), resulting in a decrease in spatial correlation index (SCI) from 0.89 to 0.71, and the MAE of key hub nodes (I-580/SR-84) increased from 14.3 to 18.6, indicating a weakened ability to model road network topology. This is mainly attributed to the loss of quantum entanglement correlation, and the quantum mutual information between nodes decreased from IQ=0.82 in the quantum system to IC=0.38 in the classical system (

Figure 11). The second group turned off quantum attention (w/o QA), reducing the sudden congestion warning time from 35 minutes to 18 minutes. The sensitivity of anomaly detection decreased from 89.7% of the complete model to 74.2%, mainly due to the degradation of the time-domain correlation mechanism causing the peak response lag of historical events and the distortion of attention weight allocation for faulty nodes. The third group replaced quantum gating with classical gating (w/o VQC), resulting in an increase in convergence iterations from 1450 to 2400. This is mainly attributed to three points: first, the advantage of quantum natural gradient, where QNG maintains 62% gradient strength on barren plateaus; second, the continuity of the gating function, where the forget gate

implemented by VQC has a Lipschitz constant

(classical

) in the parameter space; third, the smoothing of the loss surface, where quantum parameterization results in an average curvature

(classical

) of the loss surface.

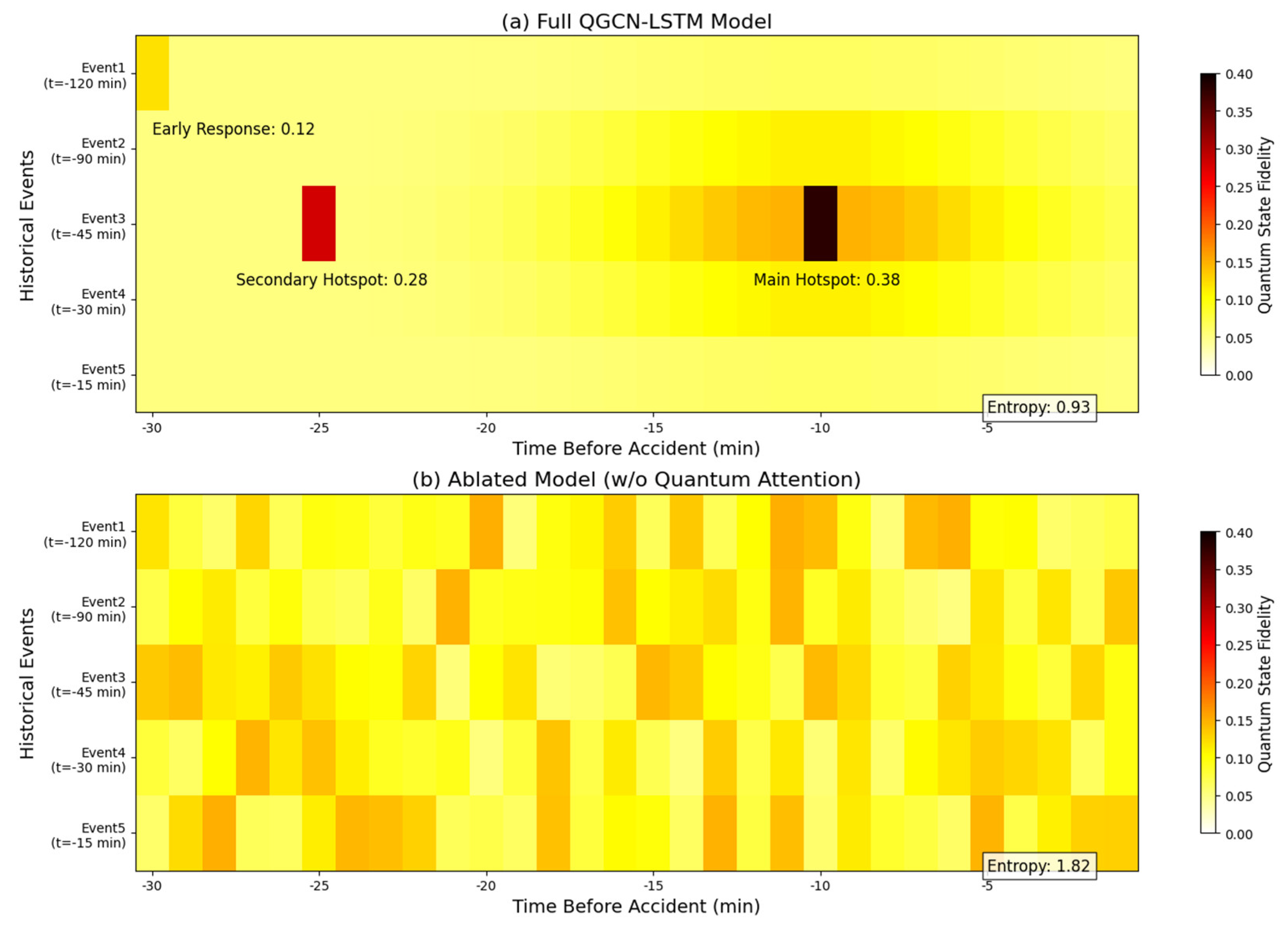

Figure 12 compares and analyzes the quantum state fidelity response characteristics of the complete model (QGCN-LSTM) and the ablation model (with the quantum attention module removed) to five similar historical events 30 minutes before the accident using a dual heatmap. The complete model (

Figure 10a) has a quantum state fidelity of 0.38 for historical event 3 at

t=-10 min, forming a significant hotspot. At

t=-25 min, the quantum state fidelity for historical event 3 is 0.28, forming a sub hotspot. At

t=-35 min, the quantum state fidelity for historical event 1 is 0.12, forming an early response. The fidelity of all events in the ablation model (

Figure 10b) is below 0.15, with no significant hotspot areas and uniform color distribution. The peak response of historical event 3 at

t=-10 min is only 0.12. This validates the core function of quantum attention mechanism:

By amplifying the weight of key historical events through the quantum state phase difference , the fidelity is greater than 0.25 (hotspot threshold) when .

Quantum state evolution of event 3:

When , the fidelity approaches 1.

4.6. Sensitivity Analysis of Quantum Hyper-Parameters

To systematically assess the impact of the key quantum settings, we conduct a grid-search over the most influential knobs:

Table 7 summarises the results on the morning-rush subset (1000 random traces). All other hyper-parameters and the training budget are kept identical to Sec. 4.1.

Observations reveal that prediction accuracy plateaus rapidly: increasing the qubit count from 8 to 10 yields less than a 1% reduction in MAE yet inflates circuit depth by 19%, while deepening the QGCN to K=4 marginally improves the spatial correlation index but lowers hardware fidelity below the NISQ-acceptable threshold of 0.96. Furthermore, a quantum-dropout retention rate of p=0.9 provides the best bias-variance trade-off; more aggressive pruning (p=0.7) degrades MAE by 4%. Collectively, these findings confirm that the originally selected configuration (n=8, K=3, p=0.9) lies near the Pareto-optimal frontier, balancing accuracy, stability, and circuit depth.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

5.1. Conclusions

The quantum long short-term memory network fusion model (QGCN-LSTM) proposed in this study has exhibited promising performance performance in urban traffic flow prediction, providing an empirical model for the application of quantum collaborative architecture in complex spatiotemporal prediction tasks. Quantum graph convolution establishes non local road network associations through entanglement gates, reducing the MAE of hub node predictions by 34.1% compared to classical models, and increasing the spatial correlation index (SCI) to 0.89. In terms of dynamic response capability, the quantum attention mechanism amplifies key event signals through fidelity weights, achieving a 35 minute early warning of sudden congestion and an anomaly detection sensitivity of 89.7%. In terms of edge computing efficiency, quantum circuit pruning technology can achieve peak memory compression and reasoning delay, meeting the real-time requirements of traffic control. This study demonstrates that the quantum classical fusion architecture provides a potentially improved balance among accuracy, efficiency, and real-time responsiveness for smart city traffic management through triple innovation of spatial entanglement enhancement, temporal phase screening, and lightweight compilation. With the improvement of quantum hardware fidelity and the maturity of cross platform frameworks, this model is expected to become a key carrier for spatiotemporal prediction to transition from classical computing to quantum advantage.

5.2. Future Work

The current evaluation is conducted on a six-month dataset from a single metropolis in Southwest China. While the dataset covers 138 road-network nodes with diverse traffic patterns (rush-hour congestion, weather events, incidents), it may not fully represent the variability present in other geographic regions with distinct urban layouts, traffic regulations, or driving behaviors. Consequently, the predictive performance of QGCN-LSTM may be optimistic under limited training data and noise conditions compared to what would be observed in more heterogeneous or out-of-domain settings. Readers should note that the scalability and robustness of the model on larger, fault-tolerant quantum devices remain or more complex scenarios to be validated.

To rigorously assess generalizability, we encourage practitioners to consider these limitations when applying the model to other domains or datasets. These limitations stem from both the current stage of quantum hardware development and the theoretical boundaries of model design itself. Firstly, current experiments rely on simulators or small-scale quantum processors, and the performance of the model on larger scale real quantum hardware and its robustness to noise need further validation. Secondly, the generalization ability of the model in more complex scenarios, such as multiple cities spanning different provinces in the east and west, mixed traffic datasets containing buses and non motorized vehicles, or non-traffic spatio-temporal tasks such as energy-load and air-quality forecasting, needs to be further explored. Furthermore, the compilation optimization of quantum circuits to specific hardware topologies and their actual impact on edge latency require a more detailed evaluation.

Future work will focus on embedding device noise models into optimization objectives, developing more expressive and noise robust quantum circuits, and strengthening hardware perception training; Design a multimodal adaptive encoder to extend the QGCN-LSTM framework to a wider range of spatiotemporal prediction fields, and explore a hybrid architecture suitable for multimodal traffic fusion and cross domain migration; Develop a quantum classical collaborative compiler for quantum processing units (QPUs) to maximize edge deployment efficiency; Exploring new paradigms for quantum topological state encoding, with the improvement of quantum hardware fidelity and the maturity of cross platform frameworks, QGCN-LSTM is expected to achieve quantum advantages in ultra large scale spatiotemporal prediction tasks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.H.; methodology, B.H. and K.J.; formal analysis, B.H.; investigation, K.J. and H.S; project administration,B.H.; supervision, B.H.; writing—original draft, B.H.; writing—review and editing, B.H. and K.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds of China National Institute of Standardization (Grant: 242025Y-12625-2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data present in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, X.H.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; He, L.Y.; Ren, Y.M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.Q. Air quality forecasting using a spatiotemporal hybrid deep learning model based on VMD–GAT–BiLSTM. Scientifc Reports. 2024, 14, 17841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, S; Carta, S.M.; Corriga, A; Podda, A.S.; Recupero, D.R. Deep learning and time series-to-image encoding for financial forecasting. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica. 2020, 7, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALijoyo, F.A.; Gongada, T.N.; Kaur, C.; Mageswari, N.; Sekhar, J.C.; Ramesh, J.V.N.; El-Ebiary, Y.A.B.; Ulmas, Z. Advanced hybrid CNN-Bi-LSTM model augmented with GA and FFO for enhanced cyclone intensity forecasting. Alexandria Engineering Journal. 2024, 92, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Wang, X.D.; He, Q.X. Application and performance optimization of CNN enhanced Informer model in industrial time series prediction. Journal of Computer Applications. 2024, 44, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Seabe, P.L.; Moutsinga, C.R.B.; Pindza, E. Sentiment-driven cryptocurrency forecasting: analyzing LSTM, GRU, Bi-LSTM, and temporal attention model (TAM). Social Network Analysis and Mining. 2025, 15, 52–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; YAmamoto, N.; Morino, K. Sequential prediction of hall thruster performance using echo state network models. Transactions of the Japan Society for Aeronautical and Space Sciences. 2024, 67, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena. 2020, 404, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, M.V.; Swaroopa, K.; SwarnaLatha, G.; Yasaswani, V. Crop yield prediction in India based on mayfly optimization empowered attention-bi-directional long short-term memory (LSTM). Multimedia Tools & Applications, 2024, 83, 29841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Chao, S.Y.; Nie, M.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhang, M.L. Construction method of hybrid quantum long-short term memory neural network for image classification. Acta Phys. Sin. 2023, 72, 058901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, W.G. Neural network ensemble models for financial time series forecasting. Journal of Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications. 2025, 48, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.G.; Zou, F.F.; Li, S.H. Enhancing air quality prediction with an adaptive PSO-Optimized CNN-Bi-LSTM model. Applied Sciences. 2024, 14, 5787–5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, M.C.; Huang, H.Y.; Cerezo, M.; Sharma, K.; Sornborger, A.; Cincio, L.; Coles, P.J. Generalization in quantum machine learning from few training data. Nature Communications. 2022, 13, 4919–4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Cerezo, M.; Cincio, L.; Coles, P.J. Trainability of dissipative perceptron-based quantum neural networks. Physical review letters. 2022, 128, 180505–180505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, T.W.; Martin, S.; Muhammad, U. Reflection equivariant quantum neural networks for enhanced image classification. Learn.: Sci. Technol. 2023, 4, 035027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, V.; Pawale, S.; Kharat, A. A classical-quantum convolutional neural network for detecting pneumonia from chest radiographs. Neural Comput & Applic. 2023, 35, 15503–15510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Wei, Z.Y.; Dong, Y.J.; Ni, W. LSTM-RNN-FNN model for load forecasting based on deleuze’s assemblage perspective. Frontiers in Energy Research. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumakova, E.V.; Korneev, D.G.; Chernova, T.A.; Gasparian, M.S.; Ponomarev, A.A. Comparison of the application of FNN and LSTM based on the use of modules of artificial neural networks in generating an individual knowledge testing trajectory. Journal Européen des Systèmes Automatisés. 2023, 56, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.Y.; Yin, J.L.; Wu, N.; Hu, X.Y.; Sun, S.K.; Wang, Y.B. A dual-path model merging CNN and RNN with attention mechanism for crop classification. European Journal of Agronomy. 2024, 159, 127273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghatage, N.B.; Patil, P.D.; Shinde, S. Lightweight RNN-Based Model for Adaptive Time Series Forecasting with Concept Drift Detection in Smart Homes. Journal Européen des Systèmes Automatisés. 2023, 56, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanen, B.; Ali, B.A.; Riadh, F.I. A Bi-GRU-based encoder–decoder framework for multivariate time series forecasting. Soft Computing. 2024, 28, 6775–6786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, H.; Mahajan, G.; Shrotriya, A.; Shekhawat, D. Predictive data analysis: leveraging RNN and LSTM techniques for time series dataset. Procedia Computer Science. 2024, 235, 979–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Zhao, J.; Qu, H.B. A novel CNN-LSTM model with attention mechanism for online monitoring of moisture content in fluidized bed granulation process based on near-infrared spectroscopy. Spectrochimica acta. Part A, Molecular and biomolecular spectroscopy. 2025, 340, 126361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.P.; Wiese, L.; Mast, M.; Böhnke, J.; Wulff, A.; Marschollek, M.; et al. An attention-based bidirectional LSTM-CNN architecture for the early prediction of sepsis. Int J Data Sci Anal. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperno, S.; Ceschini, A.; Chang, S.Y.; Grossi, M.; Vallecorsa, S.; Panella, M. A study on quantum graph neural networks applied to molecular physics. Physica Scripta. 2025, 100, 065126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorpade, S.V.S.; Pardeshi, S.A. LSTM-QDCNN: long short-term memory and quantum dilated convolutional neural network enabled occlusion percentage prediction. Australian Journal of Electrical and Electronics Engineering. 2025, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.N.; Wang, Z.M.; Xing, R.P.; Shao, C.H.; Shi, S.S.; Li, J.X.; Zhong, G.Q.; Gu, Y.J. Quantum gated recurrent neural networks. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence. 2025, 47, 2493–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesah, A.; Cerezo, M.; Wang, S.; Volkoff, T.; Sornborger, A.T.; Coles, P.J. Absence of barren plateaus in quantum convolutional neural networks. . Physical Review X. 2021, 11, 041011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.F.; Xin, Z.X.; Hu, J.R.; He, D.S. Quantum optimal control for Pauli operators based on spin-1/2 system. International Journal of Theoretical Physics. 2022, 61, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, T.A.; Chukwu, U.; Berwald, J.; Dridi, R. Quantum Natural Gradient with Efficient Backtracking Line Search. arXiv arXiv:2211.00615. [CrossRef]

- Marco, M. Fubini-Study metrics and Levi-Civita connections on quantum projective spaces. Advances in Mathematics. 2021, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naikoo, J.; Chhajlany, R.W.; Miranowicz, A. Enhanced quantum sensing with hybrid exceptional-diabolic singularities. New Journal of Physics. 2025, 27, 064505–064505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).