Submitted:

08 August 2025

Posted:

08 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Type of Study

Sample Selection Criteria

Instrument

Expert Validation

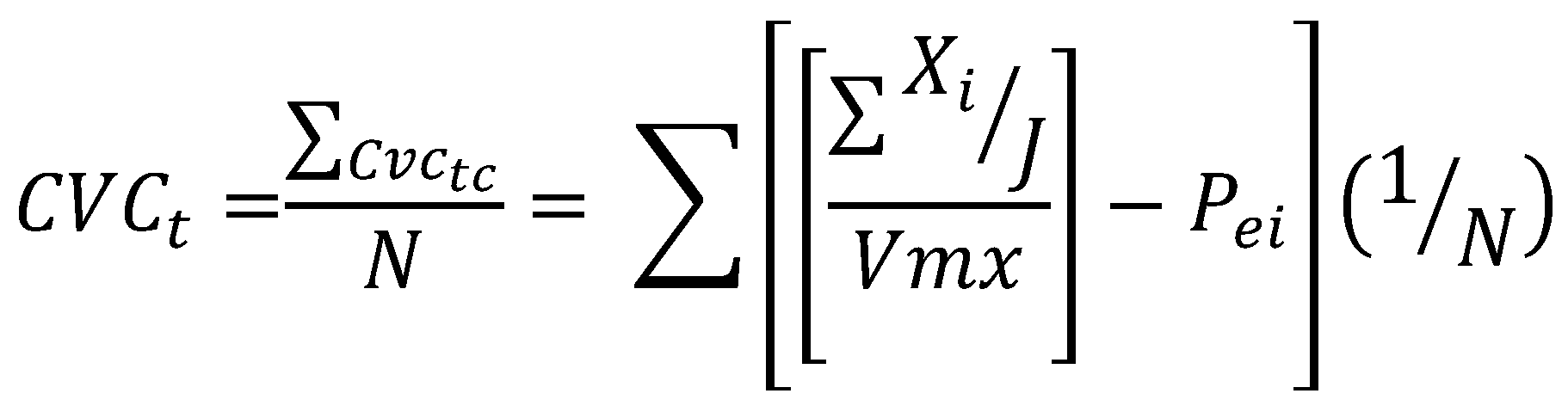

Calculation of the Results

| (a) Less than .60: Unacceptable validity and agreement. |

| (b) Equal to or greater than .60 and less than or equal to .70: Deficient validity and agreement. |

| (c) Greater than .71 and less than or equal to .80: Acceptable validity and agreement. |

| (d) Greater than .80 and less than .90: Good validity and agreement. |

| (e) Greater than .90: Excellent validity and agreement. |

Procedure

Data Analysis

3. Results

Instrument Reliability

| Cronbach's alpha | Elements |

|---|---|

| 0.857 | 9 |

| KMO and Bartlett's Test | ||

|---|---|---|

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.844 | |

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-square | 480.107 |

| gl | 36 | |

| Sig. | 0.001 | |

| Factor 1 Advice on Physical Exercise | McDonald's ω |

| Estimated | 0.852 |

| 95% CI lower limit | 0.810 |

| 95% CI upper limit | 0.894 |

| Factor 2 Application of Physical Exercise | |

| Estimated | 0.798 |

| 95% CI lower limit | 0.742 |

| 95% CI upper limit | 0.853 |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| ¿Aconsejas ejercicio físico (verbal o escrita) para prevenir enfermedades no transmisibles? | 0.820 | |

| ¿Aconsejas ejercicio físico (verbal o escrita) para tratar enfermedades no transmisibles? | 0.784 | |

| ¿Hablas de ejercicio físico con tus pacientes? | 0.702 | |

| ¿Con qué frecuencia preguntas a tus pacientes sobre su nivel de AF? | 0.606 | |

| ¿Crees necesaria la prescripción del ejercicio por profesionales especializados para apoyar en la prevención o tratamiento de ECNT? | ||

| ¿Proporcionas instrucciones escritas sobre algún programa de ejercicio físico a tus pacientes? | 0.799 | |

| ¿Con qué frecuencia refieres a tus pacientes con personal especializado para que realicen una valoración de aptitud física? | 0.695 | |

| ¿Proporcionas instrucciones verbales sobre algún programa de ejercicio físico a tus pacientes? | 0.677 | |

| ¿Consideras importante evaluar la AF a través de un test físico como parte de tus exámenes clínicos? | 0.460 |

| ítem | Percentages | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1) ¿Con qué frecuencia preguntas a tus pacientes sobre su nivel de AF? | - 63.8% Frequently or Very Frequently - Only 4.7% Never.. |

Finding: Most physicians actively inquire about physical activity. |

| 2) ¿Consideras importante evaluar la AF a través de un test físico como parte de tus exámenes clínicos? | - 44.9% Frequently or more. | Almost half of the physicians hysicians do not prioritize formal assessments of physical activity. |

| 3) ¿Con qué frecuencia refieres a tus pacientes con personal especializado para que realicen una valoración de aptitud física? | - 48.8% Never or Very Rarely - Only 26.8% Frequently or more. |

Low integration with specialized physical exercise professionals. |

| 4) ¿Proporcionas instrucciones verbales sobre algún programa de ejercicio físico a tus pacientes? | - 60.6% provide verbal instructions at least "occasionally," combining all the other options: Occasionally, Frequently, and Very Frequently.. - 29.1% do so Never or Very Rarely |

Although most physicians provide verbal instructions, about 30% of them rarely do, suggesting that these opportunities should be utilized to improve active communication. |

| 5) ¿Proporcionas instrucciones escritas sobre algún programa de ejercicio físico a tus pacientes? |

- 55.1% Never or Very Rarely. - Contrast: 60.6% give verbal instructions Occasionally or more. |

Oral communication predominates over written communication. |

| 6) ¿Aconsejas ejercicio físico (verbal o escrita) para prevenir enfermedades no transmisibles? | 70.9% do it frequently or very frequently (38.6% + 32.3%) Only 3.1% state they Never advise it, and another 9.4% do so Very Rarely. |

Most physicians recommend physical exercise as a strategy for the prevention of non-communicable diseases very frequently. |

| 7) ¿Aconsejas ejercicio físico (verbal o escrita) para tratar enfermedades no transmisibles? | 61.1% do so Frequently or Very Frequently (34.6% + 31.5%) The percentage of those who Never advise it rises to 7.1%, compared to 3.1% in prevention. |

Although recommendations also predominate, there is a slight decrease in the frequency with which physicians prescribe exercise as treatment. |

| 8) ¿Hablas de ejercicio físico con tus pacientes? | - 60.6% Frequently or Very Frequently - Only 0.8% Never |

Verbal communication is a very common practice between the physicians and the patient. |

| 9) ¿Crees necesaria la prescripción del ejercicio por profesionales especializados para apoyar en la prevención o tratamiento de ECNT? | - 85% of physicians consider it necessary or very necessary. Frequently-Very Frequently: 37.8% + 47.2% - Only 4.7% consider it Very Rarely necessary. |

There is a high recognition of the importance of the role of exercise specialists, but this contrasts with the low real frequency; they Never or Very Rarely make referrals. |

4. Discussion

Detailed Analysis of Factor 1: Advice on Physical Exercise

Detailed Analysis of Factor 2: Application of Physical Exercise

Comparative Analysis Between Factors

Comparative Analysis Between Factors

Detailed Clinical Implications

Evidence-Based Intervention Proposals

Instrument Reliability and Construct Validity

Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, E.; Durstine, J.L. Physical activity, exercise, and chronic diseases: A brief review. Sports medicine and health science 2019, 1, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, S.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, R.; Luo, L. Effectiveness of digital health interventions in promoting physical activity among college students: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2024, 26, e51714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bispo Júnior, J.P. Social desirability bias in qualitative health research. Revista de Saúde Pública 2022, 56, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börjesson, M. (2013). Förderung körperlicher aktivität im Krankenhaus. In Deutsche Zeitschrift fur Sportmedizin (Vol. 64, Issue 6, pp. 162–165). Dynamic Media Sales Verlag. [CrossRef]

- Bos-van den Hoek, D.W.; Visser, L.N.C.; Brown, R.F.; Smets, E.M.A.; Henselmans, I. Communication skills training for healthcare professionals in oncology over the past decade: a systematic review of reviews. Current opinion in supportive and palliative care 2019, 13, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, Pamela & Mankowski, Robert & Harper, Sara & Buford, Thomas. Exercise Is Medicine as a Vital Sign: Challenges and Opportunities. Translational journal of the American College of Sports Medicine 2019, 4, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G. Willumsen, J.F. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza-Bautista, D.; Janeth, F.; Mendoza, M.; Javier, F.; Farias, M.; Nava, R.R. (2024). Diseño y validación de un modelo de gestión de actividad física y del deporte universitario Design and validation of a management model for physical activity and university sports. In Retos (Vol. 57). [CrossRef]

- Cattuzzo, M.T.; Dos Santos Henrique, R.; Ré, A.H.; de Oliveira, I.S.; Melo, B.M.; de Sousa Moura, M.; de Araújo, R.C.; Stodden, D. Motor competence and health related physical fitness in youth: A systematic review. Journal of science and medicine in sport 2016, 19, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, T.J.; Baguley, T.; Brunsden, V. From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology 2014, 105, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.; Shilton, T.; Westerman, L.; Varney, J.; Bull, F. World Health Organisation to develop global action plan to promote physical activity: time for action. British journal of sports medicine 2017, 52, 484–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Domínguez, H. (2020). Estadística para no estadísticos: una guía básica sobre la metodología cuantitativa de trabajos académicos (Vol. 59). 3ciencias.

- Hernández Sampieri,R.; Mendoza-Torres. (2023). Metodología de la investigación: Las rutas cuantitativa, cualitativa y mixta (2a ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Hernández-Nieto, R. (2002). Contributions to Statistical Analysis. Universidad de los Andes file:///E:/Articulos%20cientificos/Coeficiente%20de%20Validez%20de%20contenido.pdf.

- Howes, S.; Stephenson, A.; Grimmett, C.; Argent, R.; Clarkson, P.; Khan, A.; Lait, E.; McDonough, L.R.; Tanner, G.; McDonough, S.M. The effectiveness of digital tools to maintain physical activity among people with a long-term condition(s): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Digital health 2024, 10, 20552076241299864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannou, E.; Humphreys, H.; Homer, C.; Purvis, A. Barriers and system improvements for physical activity promotion after gestational diabetes: A qualitative exploration of the views of healthcare professionals. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association 2024, 41, e15426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletta, G.; Phillips, S.M. An elusive consensus definition of sarcopenia impedes research and clinical treatment: A narrative review. Ageing Research Reviews 2023, 86, 101883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.C.; Whitt-Glover, M.C.; Marquez, D.X.; Buman, M.P.; Napolitano, M.A.; Jakicic, J.; Fulton, J.E.; Tennant, B.L. ; 2018 PHYSICAL ACTIVITY GUIDELINES ADVISORY COMMITTEE* Physical Activity Promotion: Highlights from the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Systematic Review. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 2019, 51, 1340–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, B.O.; Khan, R.; Davidov, D.; Sambamoorthi, U.; Misra, R. (2023). Exploring facilitators and barriers to patient-provider communication regarding diabetes self-management. PEC Innovation, 3. [CrossRef]

- Krops, L.A.; Bouma, A.J.; van Nassau, F.; Nauta, J.; van den Akker-Scheek, I.; Bossers, W.J.R.; Brügemann, J.; Buffart, L.M.; Diercks, R.L.; de Groot, V.; de Jong, J.; Kampshoff, C.S.; van der Leeden, M.; Leutscher, H.; Navis, G.J.; Scholtens, S.; Stevens, M.; Swertz, M.A.; van Twillert, S.; … Dekker, R. (2020). Implementing individually tailored prescription of physical activity in routine clinical care: Protocol of the physicians implement exercise = Medicine (PIE=M) development and implementation project. JMIR Research Protocols, 9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Eaton, C.B.; Driban, J.B.; McAlindon, T.E.; Lapane, K.L. Comparison of self-report and objective measures of physical activity in US adults with osteoarthritis. Rheumatology international 2016, 36, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret-Segura, S.; Ferreres-Traver, A.; Hernández-Baeza, A.; Tomás-Marco, I. El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. Anales de Psicología 2014, 30, 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, R. (2002), The Delphi method: a powerful tool for strategic management, Policing: An International Journal, Vol. 25 No. 4, pp. 762–769. [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist, S.; Boorjesson, M.; Larsson, M.E.H.; Hagberg, L.; Cider, A. Physical Activity on Prescription (PAP), in patients with metabolic risk factors. A 6- month follow-up study in primary health care. PLoS ONE 2017, 12. [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Costa, J.; Sarmento, H.; Marques, A.; Farias, C.; Onofre, M.; Valeiro, M.G. Adolescents’ Perspectives on the Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity: An Updated Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 18, 4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbanda, N.; Dada, S.; Bastable, K.; Ingalill, G.B.; Ralf, W.S. A scoping review of the use of visual aids in health education materials for persons with low-literacy levels. Patient education and counseling 2021, 104, 998–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. Post-materialism, Religiosity, Political Orientation, Locus of Control and Concern for Global Warming: A Multilevel Analysis Across 40 Nations. Social Indicators Research 2016, 128, 1273–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noetel, M.; Sanders, T.; Gallardo-Gómez, D.; Taylor, P.; Del Pozo Cruz, B.; Van Den Hoek, D.; Smith, J.J.; Mahoney, J.; Spathis, J.; Moresi, M.; Pagano, R.; Pagano, L.; Vasconcellos, R.; Arnott, H.; Varley, B.; Parker, P.; Biddle, S.; Lonsdale, C. (2024). Effect of exercise for depression: Systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. [CrossRef]

- Organizacion Mundial de la Salud. (2018). PERSONAS MÁS ACTIVAS PARA UN MUNDO MÁS SANO. Available online: https://www.paho.org/es/documentos/plan-accion-mundial-sobre-actividad-fisica-2018-2030-mas-personas-activas-para-mundo.

- Pedersen, B.K. The physiology of optimizing health with a focus on exercise as medicine. Annual review of physiology 2019, 81, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Saltin, B. Exercise as medicine–evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2015, 25, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, I.; Suárez-Álvarez, J.; García-Cueto, E. Evidencias sobre la Validez de Contenido: Avances Teóricos y Métodos para su Estimación. Acción Psicológica 2014, 10, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, JC, Bustamante, C.; Campos, S.; Sánchez, H.; Beltrán, A.; Medina, M. Validación de la Escala Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity (RAPA) en población chilena adulta consultore en Atención Primaria. Aquichán 2015, 15, 486–498. [CrossRef]

- Piercy, KL, Troiano, RP, Ballard, RM, et al. Guías de actividad física para estadounidenses. JAMA 2018, 320, 2020–2028. [CrossRef]

- Rio, C.J.; Saligan, L.N. Understanding physical activity from a cultural-contextual lens. Frontiers in public health 2023, 11, 1223919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silsbury, Z.; Goldsmith, R. y Rushton, A. Systematic review of the measurement properties of self-report physical activity questionnaires in healthy adult populations. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taber, K.S. The use of Cronbach's alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teferi, G.; Kumar, H.; Singh, P. Physical Activity Prescription for Non-Communicable Diseases: Practices of Healthcare Professionals in Hospital Setting, Ethiopia. IOSR Journal of Sports and Physical Education 2017, 04, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Wardt, V.; di Lorito, C.; Viniol, A. Promoting physical activity in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 2021, 71, e399–e405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, M.W. Exploratory Factor Analysis: A Guide to Best Practice. Journal of Black Psychology 2018, 44, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolner-Strohmeyer, G.; Keilani, M.; Mähr, B.; Morawetz, E.; Zdravkovic, A.; Wagner, B.; Palma, S.; Mickel, M.; Jordakieva, G.; Crevenna, R. Can reminders improve adherence to regular physical activity and exercise recommendations in people over 60 years old?: A randomized controlled study. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift 2021, 33, 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2020). WHO guidelines on physical activity andsedentary behaviour. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128.

| Ítems | Judges | Formulas | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Judges 1 | Judges 2 | Judges 3 | Judges 4 | Judges 5 | Judges 6 | Judges 7 | Judges 8 | Judges 9 | Sx1 | Mx | CVCi | Pei | CVCtc | |

| item 1 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 7 | 12 | 8 | 94 | 7.83333333 | 0.87037037 | 2.58117E-09 | 0.87037037 |

| item 2 | 12 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 97 | 8.08333333 | 0.89814815 | 2.58117E-09 | 0.89814815 |

| item 3 | 10 | 9 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 99 | 8.25 | 0.91666667 | 2.58117E-09 | 0.91666666 |

| item 4 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 102 | 8.5 | 0.94444444 | 2.58117E-09 | 0.94444444 |

| item 5 | 12 | 7 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 99 | 8.25 | 0.91666667 | 2.58117E-09 | 0.91666666 |

| item 6 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 103 | 8.58333333 | 0.9537037 | 2.58117E-09 | 0.9537037 |

| item 7 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 104 | 8.66666667 | 0.96296296 | 2.58117E-09 | 0.96296296 |

| item 8 | 12 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 99 | 8.25 | 0.91666667 | 2.58117E-09 | 0.91666666 |

| item9 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 100 | 8.33333333 | 0.92592593 | 2.58117E-09 | 0.92592592 |

| Total sum of the CVCtc | 8.30555553 | |||||||||||||

| General average | 0.9228395 | |||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).