1. Introduction

Positive parenting practices are essential to the healthy development, well-being, and psychological adjustment of children and adolescents (Hoeve et al., 2009; Smetana & Rote, 2019). In contrast, parenting strategies rooted in violence—such as physical punishment, harsh treatment, and neglect—have consistently been associated with both short- and long-term adverse outcomes (Hughes et al., 2017; Li, 2024; Mehta et al., 2023; Zhao, 2024). These harmful practices negatively impact children’s emotional (Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016), cognitive (McLaughlin & Sheridan, 2016), and social development (Afifi et al., 2017).

Violence against children constitutes a global public health concern, with especially high prevalence rates in low- and middle-income countries. It is estimated that approximately six out of ten children aged 2 to 14 experience violent parenting practices from primary caregivers (UNICEF, 2019; Wang & Zhang, 2024). Beyond severely impairing child development, this issue generates considerable economic and social costs (Wang & Zhang, 2024). Consequently, preventing violence against children is increasingly recognized as a critical public health priority within these regions.

1.1. Corporal Punishment and Its Associated Effects

Corporal punishment, hereafter (CP) is defined as the use of force intended to cause pain, but not injury, aimed at correcting or controlling a child’s behavior (Straus, 2010). Examples include hitting, spanking, or other forms of physical discipline enforced through fear of pain. Although CP is generally intended to modify behavior rather than inflict harm, extensive research demonstrates that it is an ineffective disciplinary strategy (Avezum et al., 2023; Gershoff, 2002; Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016; Straus, 2010). The adverse outcomes associated with CP have been consistently observed across various measurement tools, assessment sources, and culturally diverse geographic settings, as confirmed by both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016).

Exposure to CP has been linked to difficulties in emotional regulation, increasing the likelihood of impulsive and aggressive or avoidant responses in challenging situations (Bariola et al., 2011; Grogan-Kaylor et al., 2018; Lansford et al., 2014; Lotto et al., 2021). This impulsivity has been correlated with heightened vulnerability to antisocial and delinquent behaviors (Patterson et al., 2000).

Moreover, children exposed to CP face increased risks of anxiety and depression, resulting from continual exposure to stressful and fear-inducing environments (Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016). Chronic exposure also detrimentally impacts cognitive functions—such as memory and attention—potentially undermining academic success (Blair & Raver, 2012; Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016). These children may develop negative attitudes toward school, reflected by academic disengagement and diminished motivation (Pinquart, 2017). Over time, CP exposure has been linked to a heightened risk of mental health disorders, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Shaw et al., 2021).

Notably, the relational patterns learned through childhood experiences of CP often persist into adulthood, manifesting as interpersonal difficulties within romantic, occupational, and familial domains (Conger et al., 2010; Fréchette et al., 2015). Externalizing behaviors such as aggression and violence contribute to perpetuating cycles of violence across generations (Berlin et al., 2019; Grogan-Kaylor et al., 2018; Lansford et al., 2011; Lotto et al., 2021). Due to its association with numerous negative developmental outcomes, CP is considered a harmful practice that violates children’s fundamental rights (Tobón Berrío, 2020).

Despite extensive scientific evidence that has established a strong association between physical punishment and adverse developmental outcomes, it remains prevalent in many cultural contexts (Cuartas et al., 2019; UNICEF, 2025). Of particular concern, a study by Trujillo et al. (2020) found that 77% of Colombian parents reported using physical punishment within the past year, signaling a critical need for targeted intervention.1.2. Parental Stress and Emotional Self-Regulation: Implications for Parenting Practices

To understand why parents resort to violent disciplinary practices, it is necessary to examine parental stress. Elevated parenting stress is a significant predictor for harsh and coercive parenting behaviors (Alonzo et al., 2021; Le et al., 2017; Liu & Wang, 2015; Miragoli et al., 2018; Pei et al., 2020; Wolf et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2020). Parenting stress is defined as the distress experienced when parents perceive that the demands of caregiving exceed their coping resources (Crnic & Ross, 2017; Neece et al., 2012).

High stress impairs parental self-regulation, increases emotional reactivity, and reduces patience and empathy, thereby increasing the risk of physical punishment or verbal aggression as disciplinary strategies (González & Trujillo, 2024). This relationship is particularly salient in contexts marked by socioeconomic adversity, limited access to social support, and exposure to intergenerational violence— all factors that exacerbate parenting stress and constrain caregivers’ capacity to engage in positive parenting practices (Kong et al., 2023). Moreover, elevated parenting stress may interact with cultural norms that legitimize CP, leading caregivers to perceive such practices as acceptable or necessary responses to misbehavior (Lansford & Deater-Deckard, 2012).

Within Colombian population, González and Trujillo (2024) identified stress as a key moderator between parental beliefs about CP and its actual use. Their analyses indicate that belief in CP’s efficacy, combined with high parental stress, increases CP use. Indeed, in highly stressful contexts, stress rather than beliefs was the primary driver of corporal punishment use, underscoring stress as a pivotal factor influencing disciplinary choices.

Emotional regulation, conceptualized through Gross and Thompson’s (2007) model, encompasses processes by which individuals influence the emotions they experience, the timing of those emotions, and their expressive behavior (Lorber et al., 2017). The model delineates five regulatory strategies: situation selection, situation modification, attentional deployment, cognitive change, and response modulation. These strategies operate along the emotional timeline and are well supported by theoretical and empirical research (Aldao et al., 2009). Emotional regulation plays a critical role in parenting, especially under stress.

Interventions addressing parenting stress—including parent training, emotional regulation support, and community psychosocial resources—show promise for reducing violent parenting and promoting nurturing caregiving (Burgdorf, 2019).

1.3. Positive Parenting Practices

Parental monitoring involves parents’ knowledge and supervision of children’s daily activities and peer groups. This construct reflects both parental efforts to seek information and children’s voluntary disclosure (Stattin & Kerr, 2000). Effective monitoring is linked to reduced adolescent engagement in risky behaviors such as substance use, aggression, and early sexual activity (Epstein, 2018; Henderson & Mapp, 2002; Schulte & Vaca, 2024). It also strengthens parent-child communication and emotional support, which are essential for psychosocial development (Pelham et al., 2024). However, practitioners often report a lack of structured tools to guide parents in monitoring, underscoring the need for evidence-based interventions (Pelham, 2023; Schulte & Vaca, 2024).

Parental support and acceptance are critical components in the emotional and psychological development of children. These elements not only strengthen the child’s sense of self-worth but also enhance resilience in the face of adversity (Larsson et al., 2025). The parenting practice of support and acceptance refers to the behaviors and attitudes exhibited by parents that demonstrate affection, understanding, respect, and unconditional acceptance toward their children. These behaviors foster an emotionally secure and nurturing environment, promoting socioemotional development, self-esteem, and psychological well-being in both children and adolescents. Empirical evidence indicates that these practices are associated with lower levels of behavioral and emotional problems, as well as enhanced social skills and resilience (Rohner, 2017).

Parental inductive discipline is a parenting strategy that emphasizes reasoning, explanation, and perspective-taking to guide children’s behavior, in direct contrast to coercive or punitive methods. This approach has been empirically shown to foster more favorable emotional and social outcomes in children, alongside the development of prosocial behaviors, with child inhibitory control and sympathy posited as key mediating mechanisms (Melis Yavuz. Et al., 2022). The prevalence of inductive discipline typically increases as children transition from early to middle childhood. During this developmental phase, parents—particularly mothers—tend to shift away from harsher disciplinary strategies, adopting more explanatory and empathetic approaches (Vrantsidis et al., 2024). This transition is strongly influenced by children’s cognitive and social maturation, particularly advancements in executive functioning and inhibitory control (Vrantsidis et al., 2024). Inductive discipline has been consistently associated with reductions in externalizing behaviors, such as aggression and defiance, and increases in prosocial behavior (Choe et al., 2023; Xiao, 2016). Its effectiveness is further enhanced when applied in conjunction with parental warmth and adaptive emotion regulation strategies, such as cognitive reappraisal (Xiao, 2016). Although widely regarded as a constructive and developmentally appropriate parenting strategy, the efficacy of inductive discipline may exhibit variability across cultural contexts and family systems. This variability underscores the critical importance of culturally sensitive and contextually responsive approaches in the design and implementation of parenting interventions.

1.4. Evidence-Based Programs for the Reduction of Violent Parenting Behaviors

Although the literature acknowledges the importance of evidence-based interventions, many intervention programs lack effective evaluations. The World Health Organization (WHO) (2023) is promoting the use of evidence-based strategies to eliminate violence against children. One key strategy is to support parents and caregivers, as they are often the primary perpetrators of physical and emotional violence against children. As a result, parenting interventions are increasingly being implemented on a large scale, with growing interest from public policy makers.

The study by Molina Espí (2024) analyzed intervention and prevention programs addressing parental violence against children. The study concludes that there is limited evidence on both intervention and prevention programs that have been rigorously evaluated for their effectiveness. These findings underscore the need to continue directing scientific research toward the evaluation of programs currently being implemented in the field.

Other studies have found that parenting improvement programs are generally structured and predominantly implemented in high-income countries (91%) (Altafim & Linhares, 2016). All studies that assessed parenting practices reported improvements following the intervention. The authors conclude that parenting education programs represent an effective strategy for the universal prevention of child violence and maltreatment. The findings underscore the importance of implementing and rigorously evaluating such programs in low- and middle-income countries (Altafim & Linhares, 2016; Wang & Zhang, 2024).

Most meta-analyses have focused exclusively on the short-term effects of parental interventions. The evaluation of long-term outcomes remains limited, largely due to ethical and financial challenges—such as the reliance on waitlist control groups and insufficient resources to support extended follow-up assessments. Nonetheless, as the core aim of parental interventions is to achieve lasting improvements in parenting behaviors, their long-term effectiveness, as examined through longitudinal research, represents the most meaningful and policy-relevant outcome (Backhaus et al., 2023).

In conclusion, parental interventions can successfully reduce physical and emotional violence by parents and caregivers in longitudinal programs. Given the growing interest in global policies and the expansion of these interventions, more research is urgently needed to evaluate and validate interventions that are contextualized and seek to better maintain long-term effects.

In Colombia, research on targeted programs to reduce parental violence remains sparse despite governmental efforts, revealing a critical gap. This study responds to that need by evaluating the SERES program, designed to reduce violent parental practices and stress while fostering positive parenting behaviors such as emotional support, inductive discipline, and monitoring.

1.5. Hypothesis

Based on the study’s objective, methodological design, and analytical strategy, the following hypothesis was formulated: The patterns of change in physical punishment prevalence, parental stress levels, emotional regulation, and positive parenting practices (monitoring, inductive discipline, and support and acceptance) between pre-test (T1) and post-test (T2) will allow for prediction with above-chance accuracy of a participant’s group affiliation (control or experimental).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

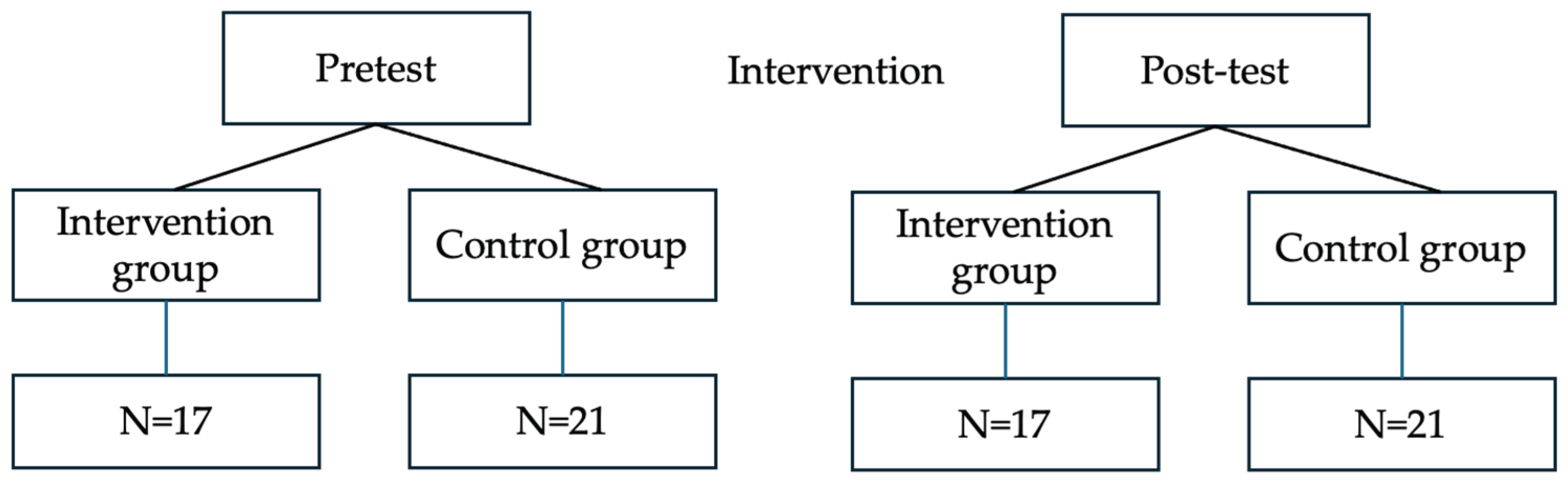

As depicted in

Scheme 1, the present study employs a quasi-experimental design with both pretest and post-test measurements. The intervention group consists of 38 participants with 21 assigned to the intervention group and 17 assigned to the control group (Hernandez et al. 2014).

According to the study’s design, pre-test measures were administered to all participants to assess the prevalence of physical punishment, levels of parental stress, self-regulation, and positive parenting practices, including monitoring, inductive discipline, and support and acceptance. Participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group. The intervention group participated in the Seres program over a 12-month period, while the control group did not receive any intervention. Following the intervention period, post-test assessments were conducted with parents from both the intervention and control groups.

2.2. Participants and Procedure

A total of 38 participants were enrolled in the study, with 17 in the control group and 21 in the experimental group. The mean age of the caregivers was 34.64 years (SD = 9.92). Most caregivers were female (control group: n = 13, 76.5%; experimental group: n = 16, 75.0%), with the remaining caregivers being male (control group: n = 4, 23.5%; experimental group: n = 5, 25.0%). The primary kinship role of the caregivers was parent (control group: n = 16, 94.1%; experimental group: n = 18, 85.0%). The most frequent socioeconomic status among caregivers was middle-class (control group: n = 13, 76.5%; experimental group: n = 13, 60.0%), followed by lower-class (control group: n = 4, 23.5%; experimental group: n = 7, 35.0%) and upper-class (experimental group: n = 1, 5.0%).

The most common marital status among caregivers was in a consensual union (control group: n = 12, 70.6%; experimental group: n = 10, 45.0%). Other marital statuses included married (control group: n = 2, 11.8%; experimental group: n = 4, 20.0%), single (control group: n = 3, 17.6%; experimental group: n = 3, 15.0%), divorced (experimental group: n = 2, 10.0%), widowed (experimental group: n = 1, 5.0%), and separated (experimental group: n = 1, 5.0%).

The most prevalent education level among caregivers was secondary education (control group: n = 9, 52.9%; experimental group: n = 10, 45.0%). Other education levels included undergraduate education (control group: n = 3, 17.6%), technical/technological education (control group: n = 2, 11.8%; experimental group: n = 5, 25.0%), basic primary (ninth grade) education (control group: n = 2, 11.8%), primary education (control group: n = 1, 5.9%; experimental group: n = 4, 20.0%), and postgraduate education (experimental group: n = 1, 5.0%).

The sample was recruited in coordination with the Municipal Secretariat of Education in Cundinamarca, Colombia. The research protocol was formally introduced to public educational institutions that demonstrated interest in participating. During informational sessions convened by these institutions, parents, legal guardians, and/or primary caregivers were invited to enroll in the study. Those who consented to participate signed a written informed consent form, confirming their voluntary participation and guaranteeing the confidentiality of their personal data. Subsequently, the initial home visit was scheduled in collaboration with the designated program facilitators. This phase concluded with the random assignment of participants to either the control or intervention group.

2.2. Measures

Physical Aggression Scale from the Spanish version of the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scale (CTSPC; Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998).The questionnaire assesses three dimensions: Nonviolent Discipline, Psychological Aggression, and Physical Aggression. For the present study, we used the Physical Aggression subscale, which evaluates a range of behaviors—from socially sanctioned corporal punishment to criminal acts of physical assault. In addition, it includes a series of items that measure the frequency with which these disciplinary practices were used over the past year.

The Parental Emotion Regulation Inventory (PERI) is a self-report instrument designed to assess intentional and volitional parental emotion regulation, grounded specifically in the Gross and Thompson (2007) model. The original version of the PERI comprises 13 items in which parents report to the extent to which they use cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression to manage their emotions during discipline encounters. The revised version of the PERI expands its scope to include four emotion regulation strategies: suppression, understood as concealing negative emotion; capitulation, referring to giving in to the child’s aversive behavior in order to reduce one’s own emotional discomfort; escape, which involves walking away during a discipline interaction to relieve emotional distress; and reappraisal, defined as cognitively reframing the child’s behavior to decrease negative emotional responses. The PERI-2 was validated primarily with parents of toddlers (ages 1–3), using a four-factor structure (suppression, capitulation, escape, reappraisal). Internal consistency was strong (e.g., α ≈ .74–.92), with suppression, capitulation, and escape demonstrating meaningful associations with harsh parenting, lax discipline, and child aggression. However, the reappraisal subscale exhibited weaker validity in original samples. Test–retest reliability has not yet been established (Hussenot-Desenonges & Wendland, 2024).

Parental stress was measured using the Parenting Stress Index–Short Form (PSI/SF) developed by Abidin (2012). Items include statements such as “I feel trapped by my responsibilities as a parent,” rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores reflect higher levels of parental stress. The internal consistency was adequate (α = 0.87 for fathers and α = 0.86 for mothers).

Parental Monitoring was assessed using a 9-item scale measuring parental knowledge of their children’s behaviors (Kerr, Stattin, & Burk, 2010). An example item is: “My parents know who my friends are,” with a corresponding parent version. Responses were rated on a Likert scale from 1 = “does not know” to 5 = “knows a lot.” The internal consistency was high (α = 0.91 for fathers, α = 0.90 for mothers, and α = 0.88 for adolescents).

Inductive Discipline was measured using an 8-item questionnaire developed by Barrera (2003), designed to assess the extent to which parents use reasoning to draw adolescents’ attention to the consequences of their actions on others. Responses were rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 = “never” to 5 = “always.” An example item is: “When I set rules for my child, I explain why.” The scale demonstrated strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.88).

Parental Support and Acceptance were measured using the short version of the Parental Acceptance–Rejection Questionnaire (PARQ) by Rohner and Lansford (2017). This version includes 17 items assessing parental behaviors that express affection, approval, and appreciation toward the child. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree.” The scale showed good internal reliability (α = 0.86).

A sociodemographic questionnaire was designed by researchers to collect family-related information regarding household structure, socioeconomic status, and educational levels.

2.3. Intervention

This study implemented SERES: La paz empieza en casa, a psychoeducational intervention designed to reduce physical punishment and parental stress while promoting emotional self-regulation and positive parenting practices within the home. The program was theoretically grounded in Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of development, which positions everyday life as a fundamental context for learning, wherein cultural practices and family interactions play a pivotal role in children’s emotional, cognitive, and social development. Empirical support for the intervention framework stems from previous studies conducted with Colombian populations (González & Trujillo, 2024; González et al., 2014; Núñez-Talero et al., 2024; Trujillo et al., 2020), which have documented links among physical punishment, parenting stress, and broader sociocultural beliefs.

SERES: La paz empieza en casa was structured as a 12-month, multicomponent intervention informed by a situated learning approach. Learning was conceptualized as emerging from culturally meaningful, everyday family activities, with developmental goals co-constructed collaboratively with each participating family according to their specific needs, values, and household dynamics.

The core implementation strategy involved weekly 90-minute home visits conducted by psychology undergraduates in the final semesters of their training. These facilitators engaged in observation, semi-structured interviews, and context-sensitive activities tailored to the family’s circumstances. Each facilitator worked with the same family throughout the duration of the program, enabling sustained insight into family dynamics and behavioral change processes. An interdisciplinary research team—comprising university faculty and members of civil society organizations—oversaw the design, training, monitoring, and evaluation of the intervention. Families were invited to participate voluntarily and collaborated in defining goals based on their needs and pre-assessment results. In cases of psychosocial vulnerability, additional support services, including legal and clinical resources, were coordinated through university-based teams. Schools played a crucial role in identifying and recruiting families and served as points of contact for program follow-up.

The program begins with phase 1 (

Table 1) which includes a pretest or baseline assessment, initiated with the signing of informed consent during the initial home visit. Subsequently, the remaining assessment instruments are administered over a period of approximately three to six weeks, depending on the specific characteristics of the participants and their families.

The second phase focused specifically on the intervention, which was delivered exclusively to participants in the intervention group. While brief interventions could be initiated during Phase 1 as baseline assessments were being completed, Phase 2 marked the formal implementation of the intervention through the development of a tailored plan for each family. Over a 12-month period, families in the intervention group engaged in the Seres program, throughout the home visits, facilitators strategically utilize spontaneous family interactions as opportunities to introduce practical recommendations concerning parental stress, emotional regulation, and the promotion of positive parenting practices. Each session is grounded in a methodological framework that combines semi-structured interviews, systematic observation, and dialogical information exchange.

Importantly, the planning of each visit is informed by the results obtained during the baseline assessment, as well as by the progress and challenges identified in the previous session. This dynamic and responsive design allows facilitators to adapt interventions to the evolving needs of each family.

To ensure continuity between sessions and to reinforce learning, participants are assigned contextualized daily tasks and supported using program-specific instructional guides designed to facilitate reflection and behavioral implementation.

Phase 3 consisted of the final assessment or post-test. Upon completion of the 12-month intervention period, a post-intervention evaluation was administered to both the intervention and control groups to assess the program’s impact on the target variables.

2.4. Data Analysis

To determine whether changes in parenting behavior reliably distinguish control from experimental participants, we implemented a feed-forward artificial neural network (ANN) in Python using TensorFlow (Abadi et al., 2015) and Keras (Chollet, 2015) on Google Colab. We chose this approach because social and developmental processes frequently involve non-linear interactions and interdependencies that exceed the explanatory power of linear models (May et al., 2008; Pasini & Amendola, 2024; Hosain et al., 2024).

Our raw data comprised 37 participants by 256 item-level scores exported from Excel into CSV. For each measure—including the Physical Aggression Scale, Parental Emotion Regulation Inventory, Parenting Stress Index, Parental Monitoring, Inductive Discipline, and Parental Support and Acceptance—we computed a difference score Δ = (Post-test − Pre-test). This transformation emphasizes program-induced change rather than baseline levels. Missing Δ-values (< 1% of cells) were imputed with the median of each variable, a robust strategy when distributions deviate from normality (Little & Rubin, 2002). Finally, we standardized all Δ-scores (zero mean, unit variance) based on training-set parameters to ensure comparable scaling across features.

Our ANN architecture was selected via grid search over hidden-layer sizes {32, 64, 128} and learning rates {10−4, 10−3, 10−2}, using five-fold cross-validation on the training set. The optimal configuration featured two hidden layers of 64 neurons each, with Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activations to capture non-linear patterns. Input and hidden weights were initialized with the Glorot uniform initializer, and a fixed random seed (42) was set for NumPy and TensorFlow to ensure replicability. We employed the Adam optimizer (learning rate = 0.001, β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999) and sparse categorical crossentropy as the loss function, training for 100 epochs with a batch size of 10. Momentum-based stochastic gradient descent (momentum = 0.9) was also tested but yielded no improvement over Adam.

Data were split stratified by group: 75% (n = 28) for training and 25% (n = 9) for final testing. This partition guards against overfitting while preserving class balance. During training, model performance was monitored on a held-out validation fold, and early stopping was applied if validation loss failed to decrease for ten consecutive epochs.

Across 100 independent runs, the network achieved mean accuracy = 0.746 (SD = 0.020), precision = 0.761 (SD = 0.027), recall = 0.729 (SD = 0.030), and F1-score = 0.744 (SD = 0.028). Final test loss averaged 0.336 (SD = 0.080), indicating effective convergence. To interpret predictor importance—an approach validated by May et al. (2008) and extended by Pasini and Amendola (2024) and Hosain et al. (2024)—we examined the absolute first-layer weights averaged across runs. Difference scores for Suppression (item 2), Physical Punishment (item 3), and Support & Acceptance (item 12) consistently carried the highest weights, revealing their pivotal role in distinguishing the two groups.

In intuitive terms, each Δ-score is multiplied by its learned weight and summed through successive layers; large positive or negative weights indicate that increasing change on a given item strongly “pushes” the network toward the experimental or control classification. The two hidden layers allow the model to learn compound patterns—such as how simultaneous reductions in parenting stress and increases in inductive discipline jointly predict intervention exposure—that linear regressions cannot capture. By grounding our design in established non-linear variable-selection literature and specifying every hyperparameter, random seed, and preprocessing step, we provide a fully transparent protocol for replicating and extending this analysis.

3. Results

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for the key constructs measured at pretest, providing an overview of participants’ baseline characteristics across parenting, stress, and emotional regulation domains. These constructs were assessed using well-validated parenting and stress scales.

The presence of Physical Punishment was notably low and constrained, with a mean of 1.05 (SD = 0.23) on a scale ranging from 1 to 2. This indicates that physical punishment was either minimally practiced or uniformly uncommon among participants at baseline.

Parental Distress averaged 28.03 (SD = 11.17), with scores spanning from 0 to 55, reflecting moderate levels of psychological stress experienced by caregivers. Related dimensions capturing challenges in parent-child dynamics were also assessed: Child Dysfunctional Interaction had a mean of 34.97 (SD = 7.28; range: 0–40), indicating some perceived difficulties in interactions, while Difficult Child scored a mean of 27.53 (SD = 11.36; range: 0–47), representing caregivers’ perceptions of child behavioral challenges.

A composite Parenting Stress score, aggregating these subdomains, had a mean of 78.18 (SD = 28.40) and a wide range from 0 to 147, highlighting substantial variability in stress levels experienced by participants.

The emotional regulation and coping strategies were captured by four constructs: Reevaluation (M = 30.51, SD = 12.54), Suppression (M = 15.86, SD = 8.75), Escape (M = 21.95, SD = 10.36), and Capitulation (M = 7.66, SD = 5.30). These measures offer important insights into how participants manage and regulate emotional responses in stressful parenting situations.

Regarding disciplinary practices, the Physical Punishment construct (distinct from its mere presence) recorded a mean of 2.27 (SD = 1.66) on a 0–5 scale, indicating some variation in the usage or attitudes toward physical punishment.

Parental monitoring was relatively high, with a mean score of 42.41 (SD = 9.09) out of a maximum of 50, demonstrating significant levels of parental oversight and involvement.

Finally, positive parenting strategies were characterized by high average scores on Support and Acceptance (M = 73.97, SD = 14.38) and Inductive Discipline (M = 22.63, SD = 8.96), reflecting considerable endorsement of nurturing and reasoned disciplinary approaches.

Together, these descriptive statistics provide a comprehensive snapshot of the sample’s baseline profiles, setting a foundation for further analyses examining the relationships among these constructs and their predictive utility.

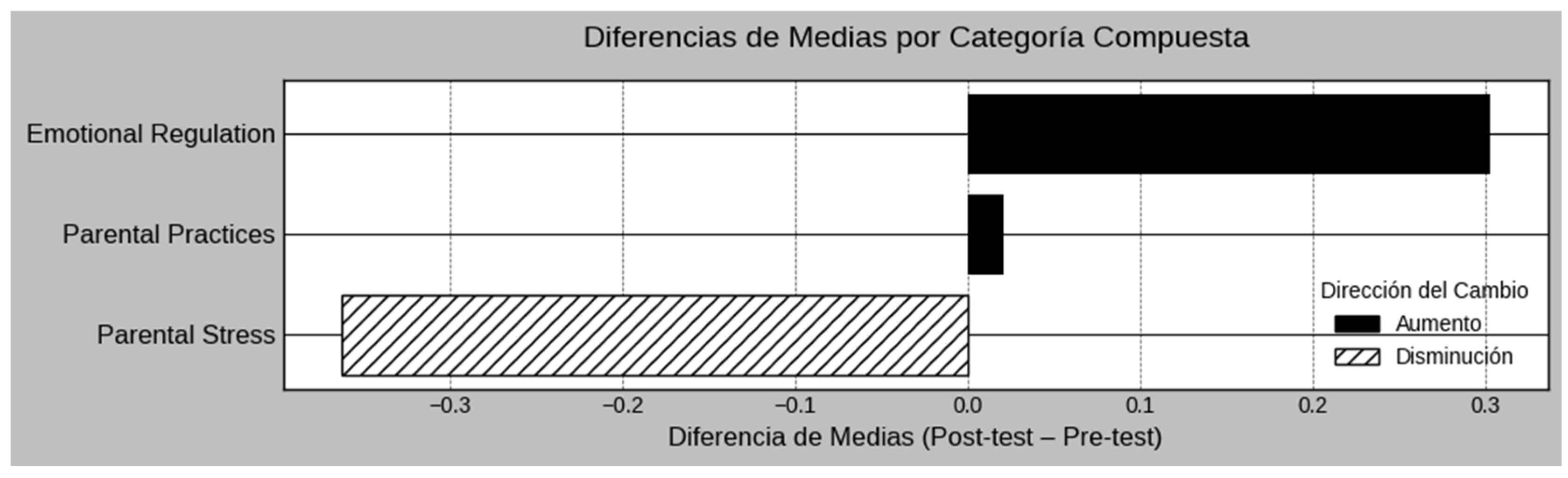

3.2. Pre-Test vs. Post-Test Comparison

Figure 1 displays the average change in three composite domains—Parental Stress, Parental Practices, and Emotional Regulation—from the pre-test (T1) to the post-test (T2). On average, Parental Stress declined (M = –0.36), reflecting reduced parental distress, fewer perceptions of the child as difficult, and less dysfunctional interaction post-intervention. Parental Practices increased modestly (M = 0.02), indicating small gains in behaviors such as active monitoring, expressions of support and acceptance, and use of inductive discipline. Emotional Regulation showed the largest positive shift (M = 0.30), driven primarily by improvements in cognitive reappraisal strategies alongside more adaptive use of suppression and capitulation.

For instance, items assessing inductive discipline (e.g., encouraging the child to reflect on the consequences of their actions) and support and acceptance (e.g., offering praise or emotional reassurance) both trended upward. Similarly, reevaluation items (e.g., reframing challenging parent–child interactions in a more constructive light) accounted for much of the Emotional Regulation gain. In contrast, indicators related to parental distress (e.g., feeling overwhelmed or losing enjoyment in daily activities) and difficult child perceptions (e.g., viewing the child’s behavior as more problematic than expected) moved downward.

Supplementary group-level comparisons showed that both control and experimental participants followed the same pre-post trajectories, with the experimental subgroup exhibiting slightly greater increases in Practices and Regulation, and marginally smaller reductions in Stress. These results highlight the intervention’s overall effectiveness in reducing stress and bolstering positive parenting and emotion-regulation strategies.

3.3. Neural Network Analysis of Program Effectiveness

Neural networks offer a powerful approach to hypothesis testing when the underlying processes are complex and potentially nonlinear. In the present study, this method was employed to determine whether sufficient structure exists in the data to reliably distinguish participants in the control group from those in the experimental group. By capturing interactions that traditional linear models might overlook, neural networks can provide deeper insights into how specific variables contribute to the observed outcomes of the intervention.

The neural network was trained using a backpropagation algorithm with a learning rate of 0.01 and a momentum of 0.9. Its architecture consisted of three layers: an input layer with 256 neurons, two hidden layers with 64 neurons each, and an output layer with 2 neurons. The Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function was used in the hidden layers, while a softmax activation function was applied in the output layer. The model was trained for 100 epochs with a batch size of 10.

Performance Metrics.

The model’s performance was assessed using multiple binary classification metrics, including accuracy, loss, precision, recall, and F1-score. After training 100 neural networks, the average accuracy was 0.746 (SD = 0.020). Loss values exhibited a decreasing trend across training epochs, with an average final loss of 0.336 (SD = 0.080), indicating that the model effectively learned the underlying patterns of change in parenting behavior associated with the SERES program. Furthermore, the average precision was 0.761 (SD = 0.027), recall was 0.729 (SD = 0.030), and the average F1-score was 0.744 (SD = 0.028). These results—marked by high accuracy and favorable precision, recall, and F1 metrics—suggest the presence of a discernible structure in the data that allows for reliable classification of participants into control and experimental groups.

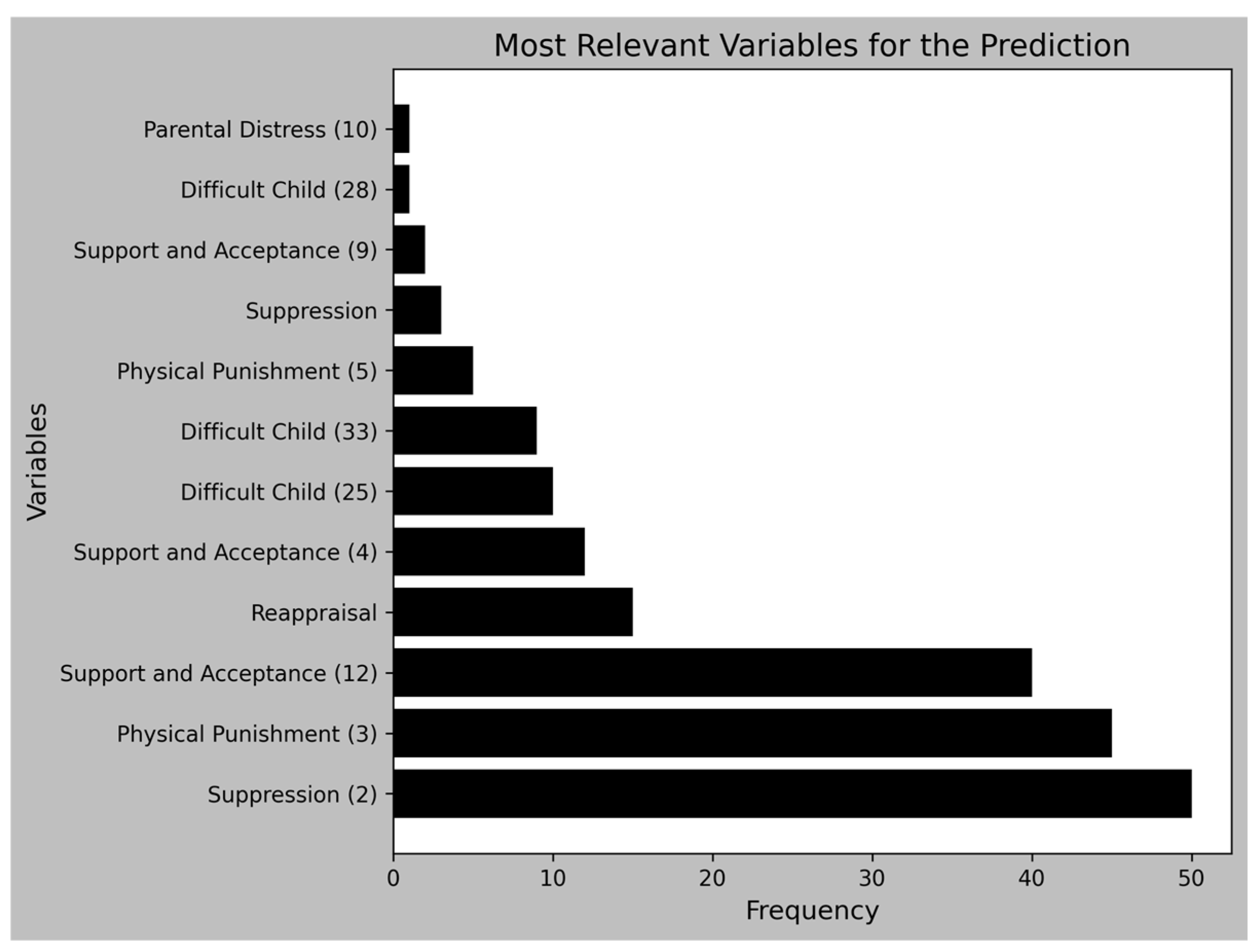

Most Relevant Variables for Prediction are presented in

Figure 2. An analysis of first-layer weights identified the variables most critical for distinguishing between the two groups. Each trained model revealed a subset of variables with the strongest predictive weights. Across multiple runs, Suppression (SU2) emerged as the most frequently selected predictor, followed closely by

Physical Punishment (CF3) and

Support and Acceptance (APO12). Other relevant variables included

Reappraisal (RV),

Support and Acceptance (APO4),

Difficult Child (ND25, ND33, ND28),

Physical Punishment (CF5),

Suppression (SU),

Support and Acceptance (APO9), and

Parental Distress (MP10), though these appeared with lower frequency.

The frequency with which each variable was identified as a top predictor underscores its relative importance in the model. For instance, SU2 and CF3 were selected in nearly 50 training runs, indicating a consistent influence on classification outcomes. Similarly, APO12, RV, and APO4 also appeared with high frequency, highlighting their predictive strength. This analysis demonstrates that specific parenting behaviors and stress-related constructs play a critical role in distinguishing individuals who received SERES intervention from those who did not.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the neural network approach effectively captures nonlinear relationships among key variables relevant to the outcomes of the SERES program. By identifying a consistent set of predictors, this method provides valuable guidance for future research and practical applications aimed at refining intervention strategies and support systems for both caregivers and children.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention program designed to reduce violent parenting practices—specifically, the use of physical punishment and parenting-related stress—while promoting positive parenting behaviors such as emotional support and acceptance, inductive discipline, and parental monitoring. To achieve this objective, we combined descriptive statistical analyses with an artificial intelligence (AI)-based analytical approach to assess the impact of experimental intervention.

Descriptive findings from the pre-test phase indicated a generally low reported frequency of physical punishment. This pattern may reflect social desirability bias, underreporting, or early shifts in disciplinary norms. However, when evaluated using a broader measurement construct, greater variability in the use of physical punishment emerged, suggesting that it remains a prevalent strategy within certain family contexts (Cuartas et al., 2019; González & Trujillo; UNICEF, 2025).

Parental stress showed a wide distribution, indicating substantial variation among caregivers regarding their perceived distress related to parenting demands (Crnic & Ross, 2017; Neece et al., 2012). This was accompanied by moderate emotional distress, difficulties in parent–child interactions, and increased perceptions of children as challenging. Together, these indicators suggest family dynamics characterized by heightened emotional reactivity, which may increase the likelihood of resorting to maladaptive disciplinary practices in high-stress situations (Alonzo et al., 2021; Le et al., 2017; Liu & Wang, 2015; Miragoli et al., 2018; Pei et al., 2020; Wolf et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2020).

Emotional regulation strategies revealed a heterogeneous distribution. While cognitive reappraisal appeared more frequently used, mechanisms such as escape, suppression, and capitulation were also observed. This pattern underscores the need to strengthen emotional self-regulation skills among caregivers. These findings align with previous research linking emotional dysregulation to increased parenting stress and the use of punitive practices, highlighting the importance of interventions targeting the promotion of more positive family environments (Alonzo et al., 2021; González & Trujillo, 2024; Wolf et al., 2021).

Conversely, the high levels of parental monitoring observed in the sample represent a strength in parenting practices, as do the positive scores on support, acceptance, and inductive discipline. These results suggest that, although risk factors are present, existing parenting resources and competencies can be reinforced and enhanced through psychoeducational interventions (WHO, 2023).

Comparisons between the control and intervention groups demonstrate the significant impact of the SERES: La Paz empieza en casa program across multiple domains associated with parenting practices, emotional regulation, and perceptions of child behavior. Overall, the intervention group showed improvements in approximately two-thirds of the assessed indicators, indicating a broad and consistent effect of the program.

The most notable gains occurred in inductive discipline and dimensions related to parental support and acceptance. These findings highlight the program’s effectiveness in fostering positive disciplinary approaches and enhancing parental warmth—both fundamental to developing secure parent–child attachment and reducing coercive or punitive interaction patterns (Rohner, 2017; Yavuz et al., 2021; Vrantsidis et al., 2024). The observed improvements correspond with prior literature emphasizing the importance of culturally and contextually tailored psychoeducational interventions aimed at transforming traditional parenting styles and promoting sensitive, responsive caregiving (Altafim & Linhares, 2016; Wang & Zhang, 2024).

This study also employed neural network analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of the SERES program in modifying parenting practices and psychological variables related to caregiver behavior. Using artificial neural networks (ANNs) provided a robust method to explore complex, nonlinear relationships among multiple predictors, delivering insights beyond those achievable through traditional linear statistical models.

The neural network model reliably distinguished between participants in the intervention and control groups, achieving an average accuracy of 74.6%. Performance metrics including precision, recall, and F1-score were also consistent, reflecting a stable pattern of group discrimination and suggesting that the SERES intervention produced observable changes in behavioral and emotional indicators as intended.

A key contribution of this analysis is the identification of central predictive variables. Certain measures, such as Emotional Suppression, Physical Punishment, and Parental Support and Acceptance, requently appeared across multiple models, underscoring their pivotal role in differentiating participants who received the intervention. Additional variables like Cognitive Reappraisal and subscales of the Difficult Child construct further illustrate the multifaceted nature of changes promoted by the SERES program. Notably, several of these predictors relate directly to emotional self-regulation and stress, reinforcing the conceptual framework underpinning the intervention.

AI-based analysis should be interpreted considering the inherent complexity of predictive modeling and the unique capabilities of neural networks (Hosain et al., 2024). Neural networks are especially adept at detecting complex and nonlinear relationships between variables and outcomes (May et al., 2008; Pasini & Amendola, 2024; Salimi et al., 2016), thus identifying variables exhibiting subtle yet consistent patterns that provide critical discriminative information—even if they do not show large mean differences. Variables with large mean differences may exhibit high variability or be influenced by extraneous factors, limiting their predictive utility. For example, while Inductive Discipline may show significant improvement in the experimental group, its variability could lessen its effectiveness for accurate group classification compared to a variable exhibiting smaller but more stable changes.

Furthermore, the feature-weighting approach of neural networks evaluates each variable’s unique predictive contribution independently of its average descriptive change. This means variables with moderate mean differences can be highly relevant if they interact synergistically with other predictors or capture underlying latent constructs. Such interactions, often missed in univariate analyses, are effectively integrated by the model’s internal structure. The recurrent selection of Suppression, for instance, suggests its consistent importance in classification accuracy by reflecting core dimensions of emotional regulation, even if it does not show the largest mean difference.

Finally, the neural network’s variable selection prioritizes predictors that minimize classification error across varying conditions (Chen et al., 2024). Variables such as Physical Punishment and facets of Support and Acceptance likely reflect fundamental processes tied to stress and caregiver–child dynamics critical for differentiating intervention effects. These processes may operate subtly, escaping detection through simple mean comparisons but remaining essential for understanding behavioral changes targeted by the intervention.

In conclusion, AI-based analysis offers a complementary perspective by isolating the most salient predictors for group differentiation. The neural network’s focus on emotional regulation and discipline-related variables aligns with prior research emphasizing their crucial role in developmental trajectories (Perry, 2019; Werchan et al., 2023). Its capability to identify nonlinear interactions explains its emphasis on predictors like Suppression and Physical Punishment, even amid broad improvements across multiple indicators. Ultimately, this AI-driven approach enhances understanding of the intervention’s impact and informs future development and optimization of parenting interventions and support strategies.

Despite the robust findings, this study is not without limitations. The relatively small sample size, while adequate for demonstrating the utility of the ANN approach in identifying key predictors, may limit the generalizability of some findings and the long-term stability of the model’s weights. Future research should aim for larger, more diverse samples to validate these predictive insights. From a practical standpoint, the consistent identification of Emotional Suppression, Physical Punishment, and Parental Support and Acceptance as the most salient predictors highlight critical areas for intervention. These findings suggest that programs explicitly targeting caregivers’ emotion regulation skills and offering concrete strategies to replace punitive discipline with supportive and accepting interactions are likely to yield the most profound and differentiating effects. Therefore, the SERES program, and similar interventions, could benefit from a refined focus on these high-impact components to maximize effectiveness and promote sustainable behavioral change.

5. Conclusions

The present study integrated descriptive statistical analyses with an artificial intelligence (AI)-driven approach to evaluate the effectiveness of an experimental intervention. Descriptive findings indicated that the experimental group demonstrated overall greater positive change across a broad set of indicators from pre-test to post-test, compared to the control group. Notably, improvements were observed in key constructs such as Inductive Discipline, Support and Acceptance, and Reappraisal, along with reductions in Parental Distress and perceived Child Difficulties. These results suggest a widespread positive impact of intervention on parenting practices, emotional regulation, and parenting-related stress.

Complementing these findings, the variable importance hierarchy derived from neural network analysis provided a more nuanced interpretation. While descriptive statistics highlighted broad improvements, the AI model consistently identified a specific subset of variables as the most salient predictors differentiating the experimental and control groups. From a practical standpoint, identifying high-impact predictors offers valuable guidance for enhancing the design and focus of the SERES program. Components that promote emotion regulation strategies and reduce reliance on physical punishment appear to exert a disproportionately strong influence. Strengthening these components may therefore increase both the overall effectiveness and sustainability of the intervention.

Collectively, the application of neural network analysis not only confirmed the efficacy of the SERES program but also provided deeper insight into the mechanisms of change underlying observed outcomes. Future research would benefit from the continued integration of machine learning approaches to optimize intervention design, tailor strategies to specific caregiver profiles, and improve long-term outcome prediction based on early behavioral indicators.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Martha Rocío González; methodology, Martha Rocío González and José David Amorocho; formal analysis, José David Amorocho; investigation, Martha Rocío González and Angela María Trujillo; resources, Universidad de La Sabana; data curation, José David Amorocho and Angela María Trujillo; writing—original draft preparation, Martha Rocío González, Angela María Trujillo, and José David Amorocho; writing—review and editing, Martha Rocío González, Angela María Trujillo, and José David Amorocho; project administration, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences; funding acquisition, Universidad de La Sabana. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad de La Sabana, grant number “PSI-30-2025” under the poject Evaluación del programa de intervención Seres: la paz empieza en casa para reducir prácticas parentales violentas, estrés de la crianza e incrementar prácticas parentales positivas en familias de Sabana Centro. “The APC was funded by Universidad de La Sabana”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad de La Sabana (protocol code 0207 February 12th 2025l).” for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all families involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be obtained upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all the families who willingly participated in the program and demonstrated a genuine interest in learning new parenting approaches. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors utilized SIDER and ChatGPT to assist with reviewing and improving the English academic writing. The authors have thoroughly reviewed and edited the generated content and take full responsibility for the final version of this publication

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Abidin, R. R. (2012). Parenting Stress Index, Fourth Edition, Short Form (PSI-4-SF). Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Afifi, T.O.; Ford, D.; Gershoff, E.T.; Merrick, M.; Grogan-Kaylor, A.; Ports, K.A.; MacMillan, H.L.; Holden, G.W.; Taylor, C.A.; Lee, S.J.; et al. Spanking and adult mental health impairment: The case for the designation of spanking as an adverse childhood experience. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 71, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzo, F. , Ramírez, P., & Torres, L. (2021). El estrés de la crianza: Factores asociados y consecuencias en el desarrollo infantil. Revista de Psicología y Desarrollo, 39(2), 115–130.

- Aldao, A.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Schweizer, S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altafim, E.R.P.; Pedro, M.E.A.; Linhares, M.B.M. Effectiveness of ACT Raising Safe Kids Parenting Program in a developing country. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 70, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avezum, M.D.M.d.M.; Altafim, E.R.P.; Linhares, M.B.M. Spanking and Corporal Punishment Parenting Practices and Child Development: A Systematic Review. Trauma, Violence, Abus. 2022, 24, 3094–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, S.; Leijten, P.; Jochim, J.; Melendez-Torres, G.; Gardner, F. Effects over time of parenting interventions to reduce physical and emotional violence against children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 60, 102003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bariola, E.; Gullone, E.; Hughes, E.K. Child and Adolescent Emotion Regulation: The Role of Parental Emotion Regulation and Expression. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 14, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera, F. (2003). Conexiones entre las prácticas parentales y las competencias psicosociales propias de la autonomía y la vinculación de los hijos [Connections between parenting practices and psychosocial competencies of child autonomy and bonding]. Proyecto presentado a la convocatoria cofinanciación de proyectos del Centro de Estudios Socioculturales e Internacionales CESO [Project presented at the project cofinacing convening of the CESO Sociocultural and International Study Center], Social Sciences Department, Universidad de Los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia.

- Berlin, L.J.; Appleyard, K.; Dodge, K.A. Intergenerational Continuity in Child Maltreatment: Mediating Mechanisms and Implications for Prevention. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, C.; Raver, C.C. Child development in the context of adversity: Experiential canalization of brain and behavior. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgdorf, V.; Szabó, M.; Abbott, M.J. The Effect of Mindfulness Interventions for Parents on Parenting Stress and Youth Psychological Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Cai, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Li, Z. Software Defect Prediction Approach Based on a Diversity Ensemble Combined With Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2024, 73, 1487–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, D.E.; Olwert, M.R.; Golden, A.B. Cognitive and psychophysiological predictors of inductive and physical discipline among parents of preschool-aged children. J. Fam. Psychol. 2023, 37, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keras Documentation. Available online: https://keras.io (accessed on 26 December 2018).

- Conger, R.D.; Conger, K.J.; Martin, M.J. Socioeconomic Status, Family Processes,and Individual Development. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnic, K. , & Ross, E. (2017). Parenting stress and parental efficacy. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Volume 4: Social conditions and applied parenting (3rd ed., pp. 259–280). Routledge.

- Fish, J.N.; Baams, L.; Wojciak, A.S.; Russell, S.T. Are sexual minority youth overrepresented in foster care, child welfare, and out-of-home placement? Findings from nationally representative data. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 89, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, J. L. (2018). School, family, and community partnerships. Routledge.

- Fréchette, S.; Zoratti, M.; Romano, E. What Is the Link Between Corporal Punishment and Child Physical Abuse? J. Fam. Violence 2015, 30, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 539–579.

- Gershoff, E.T.; Grogan-Kaylor, A. Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.R.; Trujillo, A. Examining the Moderating Role of Parental Stress in the Relationship between Parental Beliefs on Corporal Punishment and Its Utilization as a Behavior Correction Strategy among Colombian Parents. Children 2024, 11, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, M.R.; Trujillo, A. Examining the Moderating Role of Parental Stress in the Relationship between Parental Beliefs on Corporal Punishment and Its Utilization as a Behavior Correction Strategy among Colombian Parents. Children 2024, 11, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J. J. , & Thompson, R. A. (2007). Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 3-24). Guilford Press.

- Grogan-Kaylor, A.; Ma, J.; A Graham-Bermann, S. The case against physical punishment. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 19, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A. T. , & Mapp, K. L. (2002). A new wave of evidence: The impact of family, school, and community connections on student achievement. National Coalition for Parent Involvement in Education.

- Hoeve, M.; Dubas, J.S.; Eichelsheim, V.I.; van der Laan, P.H.; Smeenk, W.; Gerris, J.R.M. The Relationship Between Parenting and Delinquency: A Meta-analysis. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2009, 37, 749–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosain, T.; Jim, J.R.; Mridha, M.; Kabir, M. Explainable AI approaches in deep learning: Advancements, applications and challenges. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.; Bellis, M.A.; Hardcastle, K.A.; Sethi, D.; Butchart, A.; Mikton, C.; Jones, L.; Dunne, M.P. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e356–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussenot-Desenonges, S.; Wendland, J. French version of the Parental Emotion Regulation Inventory (PERI 2). Enceph. De Psychiatr. Clin. Biol. Et Ther. 2024, 51, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, M.; Stattin, H.; Burk, W.J. A Reinterpretation of Parental Monitoring in Longitudinal Perspective. J. Res. Adolesc. 2010, 20, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Zhu, N.; Ye, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, W. Childhood emotional but not physical or sexual maltreatment predicts prosocial behavior in late adolescence: A daily diary study. Child Abus. Negl. 2023, 139, 106123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansford, J.E.; Deater-Deckard, K. Childrearing Discipline and Violence in Developing Countries. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansford, J.E.; Sharma, C.; Malone, P.S.; Woodlief, D.; Dodge, K.A.; Oburu, P.; Pastorelli, C.; Skinner, A.T.; Sorbring, E.; Tapanya, S.; et al. Corporal Punishment, Maternal Warmth, and Child Adjustment: A Longitudinal Study in Eight Countries. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2013, 43, 670–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansford, J.E.; Criss, M.M.; Laird, R.D.; Shaw, D.S.; Pettit, G.S.; Bates, J.E.; Dodge, K.A. Reciprocal relations between parents' physical discipline and children's externalizing behavior during middle childhood and adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 2011, 23, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A.; Weineland, S.; Nissling, L.; Lilja, J.L. The Impact of Parental Support on Adherence to Therapist-Assisted Internet-Delivered Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in Primary Care for Adolescents With Anxiety: Naturalistic 12-Month Follow-Up Study. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2025, 8, e59489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monn, A.R.; Narayan, A.J.; Kalstabakken, A.W.; Schubert, E.C.; Masten, A.S. Executive function and parenting in the context of homelessness. J. Fam. Psychol. 2017, 31, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A. Parenting approaches, parental involvement, and academic achievement in US elementary schools. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2024, 45, 798–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. , & Wang, Y. ( 24(3), 591–602. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorber, M.F.; Del Vecchio, T.; Feder, M.A.; Slep, A.M.S. A Psychometric Evaluation of the Revised Parental Emotion Regulation Inventory. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 26, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotto, C.R.; Altafim, E.R.P.; Linhares, M.B.M. Maternal History of Childhood Adversities and Later Negative Parenting: A Systematic Review. Trauma, Violence, Abus. 2021, 24, 662–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google, “TensorFlow”, Accessed: Feb. 22, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.tensorflow.

- May, R.J.; Maier, H.R.; Dandy, G.C.; Fernando, T.G. Non-linear variable selection for artificial neural networks using partial mutual information. Environ. Model. Softw. 2008, 23, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K. A. , & Sheridan, M. A. (2016). Beyond cumulative risk: A dimensional approach to childhood adversity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(4), 239–245.

- Mehta, D.; Kelly, A.B.; Laurens, K.R.; Haslam, D.; Williams, K.E.; Walsh, K.; Baker, P.R.A.; Carter, H.E.; Khawaja, N.G.; Zelenko, O.; et al. Child Maltreatment and Long-Term Physical and Mental Health Outcomes: An Exploration of Biopsychosocial Determinants and Implications for Prevention. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2021, 54, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miragoli, S. , Balzarotti, S., Camisasca, E., & Di Blasio, P. (2018). Parents’ perception of child behavior, parenting stress, and child abuse potential: Identifying risk factors for prevention. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(1), 236–244. [CrossRef]

- Molina Espí, M. (2024). Revisión sistemática de programas de intervención y prevención de la violencia filio-parental en niños y adolescentes. Informació Psicològica, (127), 11–19.

- Neece, C.L.; A Green, S.; Baker, B.L. Parenting Stress and Child Behavior Problems: A Transactional Relationship Across Time. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 117, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez-Talero, D.V.; González, M.R.; Trujillo, A. Play Nicely: Evaluation of a Brief Intervention to Reduce Physical Punishment and the Beliefs That Justify It. Children 2024, 11, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasini, A.; Amendola, S. A Neural Modelling Tool for Non-Linear Influence Analyses and Perspectives of Applications in Medical Research. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, G.R.; DeBaryshe, B.D.; Ramsey, E. A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, J. , Shao, D., Yin, X., & Wang, M. (2020). Parenting stress and its impact on child development: A review of the literature. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(3), 603–617. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz-Torres, J.C.; Davis, I.S.; Thornburg, M.A.; Patel, H.; Aks, I.R.; Tapert, S.F.; Brown, S.A.; Pelham, W.E. How Can Clinicians Improve Parental Monitoring of Adolescents? A Content Review of Manualized Interventions. Evidence-Based Pr. Child Adolesc. Ment. Heal. 2024, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelham, W.E.; Patel, H.; Somers, J.A.; Racz, S.J. Theory for How Parental Monitoring Changes Youth Behavior. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2024, 13, 18–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, N. E. , Lisiango, S., & Ford, L. (2019). Understanding the role of motivation in children’s self-regulation for learning. In D. Whitebread (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Developmental Psychology and Early Childhood Education (pp. 361–377). Sage.

- Pinquart, M. Associations of Parenting Styles and Dimensions with Academic Achievement in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 28, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohner, R. P. (2017). Parental acceptance-rejection theory, methods, and evidence: A psychosocial approach to interpersonal acceptance. Parenting: Science and Practice, 17(1), 1–35.

- Rohner, R. P. , & Lansford, J. E. (2017). Parental Acceptance–Rejection Questionnaire (PARQ): Test manual (4th ed.). Rohner Research Publications.

- Salimi, A.; Rostami, J.; Moormann, C.; Delisio, A. Application of non-linear regression analysis and artificial intelligence algorithms for performance prediction of hard rock TBMs. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 58, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, R.; Vaca, F.E.; Li, K. Adolescent Parental Monitoring Offers Protection Against Later Recurrent Driving After Drinking. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2024, 75, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, Y. Commentary: Time to reconceptualize ASD? comments on Happe and Frith (2020) and Sonuga-Barke (2020). J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 62, 1042–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, J.G.; Rote, W.M. Adolescent–Parent Relationships: Progress, Processes, and Prospects. Annu. Rev. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 1, 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stattin, H.; Kerr, M. Parental Monitoring: A Reinterpretation. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 1072–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stattin, H.; Kerr, M. Parental Monitoring: A Reinterpretation. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 1072–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, M. A. (2010). Prevalence, societal causes, and trends in corporal punishment by parents in world perspective. Law and Contemporary Problems, 73(2), 1-30. http://www.jstor. 2576. [Google Scholar]

- A Straus, M.; Hamby, S.L.; Finkelhor, D.; Moore, D.W.; Runyan, D. Identification of Child Maltreatment With the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and Psychometric Data for a National Sample of American Parents. Child Abus. Negl. 1998, 22, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobón Berrío, L. E. (2020). El castigo físico desde la narrativa de padres y madres ordinarios. entre tradición, ciencia y derecho. Estudios Socio-Jurídicos, 22(2), 263–290.

- Trujillo, A.; González, M.R.; Fonseca, L.; Segura, S. Prevalence, Severity and Chronicity of Corporal Punishment in Colombian Families. Child Abus. Rev. 2020, 29, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF (2019). Hidden in plain sight: A statistical analysis of violence against children.

- UNICEF. (2025). Violent discipline: Global and regional estimates [Data set]. UNICEF. https://data.unicef.

- Vrantsidis, D.M.; Ali, N.; Khoei, M.; Wiebe, S.A. Bidirectional relations between parents’ discipline strategies and children’s inhibitory control from early to middle childhood. J. Fam. Psychol. 2025, 39, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, H. A Scoping Review of Parenting Programs for Preventing Violence Against Children in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Trauma, Violence, Abus. 2023, 25, 2173–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werchan, D.M.; Ku, S.; Berry, D.; Blair, C. Sensitive caregiving and reward responsivity: A novel mechanism linking parenting and executive functions development in early childhood. Dev. Sci. 2022, 26, e13293–e13293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, K. , Chaves, M., González, P., & Ramírez, L. (2021). Parental stress and its impact on child development: A review of recent findings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 62(4), 567–582.

- World Health Organization. (2023). Preventing child maltreatment: A guide to taking action and generating evidence. World Health Organization. https://www.who. 9789.

- Xiao, X. (2016). Inductive discipline and children’s prosocial behavior: The role of parental emotion regulation strategies [Doctoral dissertation, Syracuse University]. https://surface.syr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi? 1507. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, A.M.; DeVoe, E.R.; Steketee, G.; Emmert-Aronson, B.O.; Brown, T.; Muroff, J. Outcomes of a reflective parenting program among military spouses: The moderating role of social support. J. Fam. Psychol. 2020, 34, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, H.M.; Dys, S.; Malti, T. Parental Discipline, Child Inhibitory Control and Prosocial Behaviors: The Indirect Relations via Child Sympathy. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2022, 31, 1276–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. Balancing Discipline and Warmth: How Parenting Styles Shape Adolescent Depression Outcomes. J. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 45, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).