1. Introduction: The Evolution of mRNA-Based Cancer Immunotherapy

1.1. Current Landscape, Limitations, and Comparisons

mRNA vaccines gained prominence through their applications in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic [

1,

2], inspiring adaptations for cancer treatment. Primary strategies include personalized neoantigen vaccines targeting patient mutations (e.g., mRNA-4157/V940, which reduces melanoma recurrence by 44% when combined with pembrolizumab [

3]) and shared tumor-associated antigen (TAA) vaccines (e.g., BNT111, with response rates of 10-15% [

4]). Recent validation demonstrates that early type-I interferon responses mediate successful immunotherapy and epitope spreading in poorly immunogenic tumors [

5]. Early human trials for pediatric cancers, building on the July 2025 preclinical breakthroughs, are now underway with great anticipation [

6,

7].

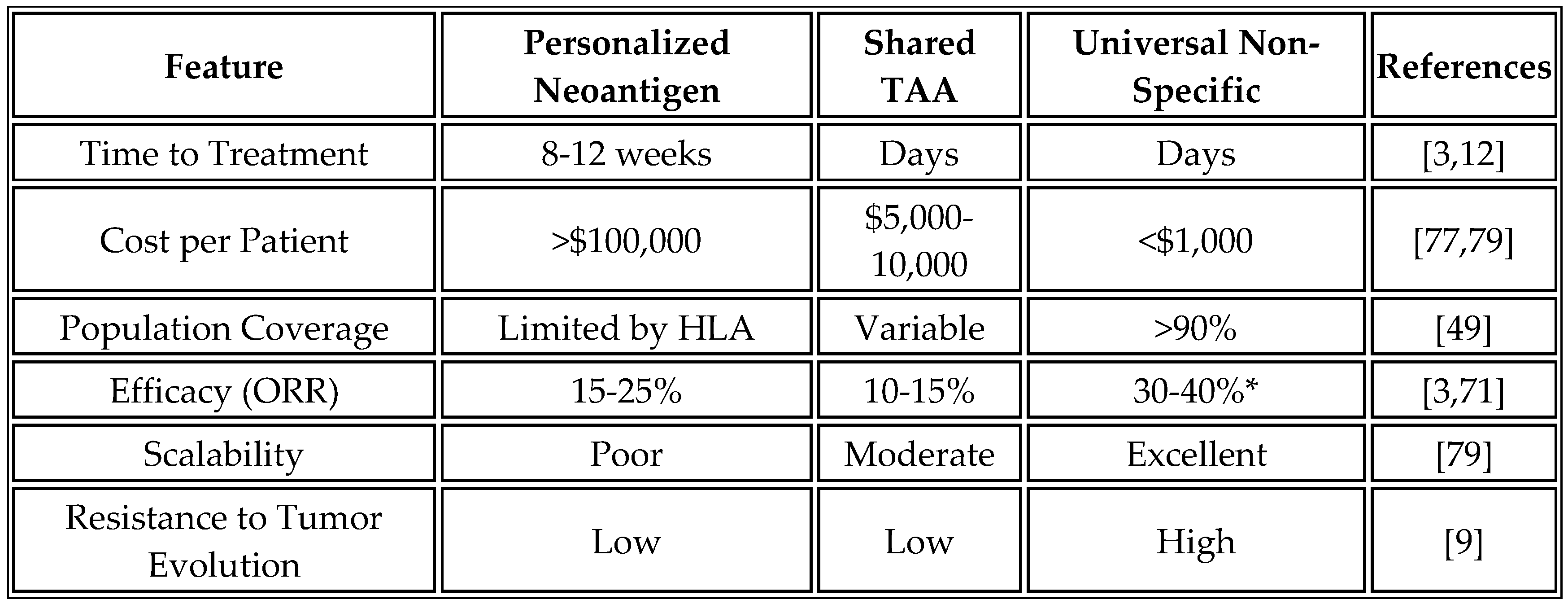

However, personalized approaches face several barriers: 8–12-week timelines for sequencing and production increase the risk of disease progression; costs exceed

$150,000, limiting access; the accuracy of neoantigen prediction ranges from 2% to 5% [

8]; and tumor heterogeneity evolves, rendering antigens unpredictable [

9]. Shared TAA vaccines struggle with tolerance and limited efficacy in pretreated patients [

10]. Cytokine-encoding mRNA (e.g., mRNA-2752) risks systemic toxicity and exhaustion [

11].

Counterarguments favor antigen-specific vaccines for precision in high-mutation tumors, potentially outperforming non-specific inflammation that could cause off-target effects or CRS. For instance, neoantigen vaccines have shown targeted responses in pancreatic cancer trials, although they are less scalable [

12,

13].

1.2. Paradigm Shift: Non-Tumor-Specific Immune Activation

Effective immunotherapy may rely on innate activation to reprogram the TME [

14,

15], enabling epitope spreading [

16]. This universal mRNA platform encodes non-tumor-specific antigens to trigger inflammation, transforming cold tumors. "Universal" denotes non-personalized applicability. While promising for global deployment, human trials are still in their early stages, with claims of broad efficacy requiring validation and verification. Risks such as tumor escape via antigen loss or checkpoint inhibition (e.g., LAG-3, TIM-3) require close monitoring [

17].

2. Mechanistic Foundation: Innate Immunity and Epitope Spreading

2.1. Tumor Immune Phenotypes and Microenvironment Reprogramming

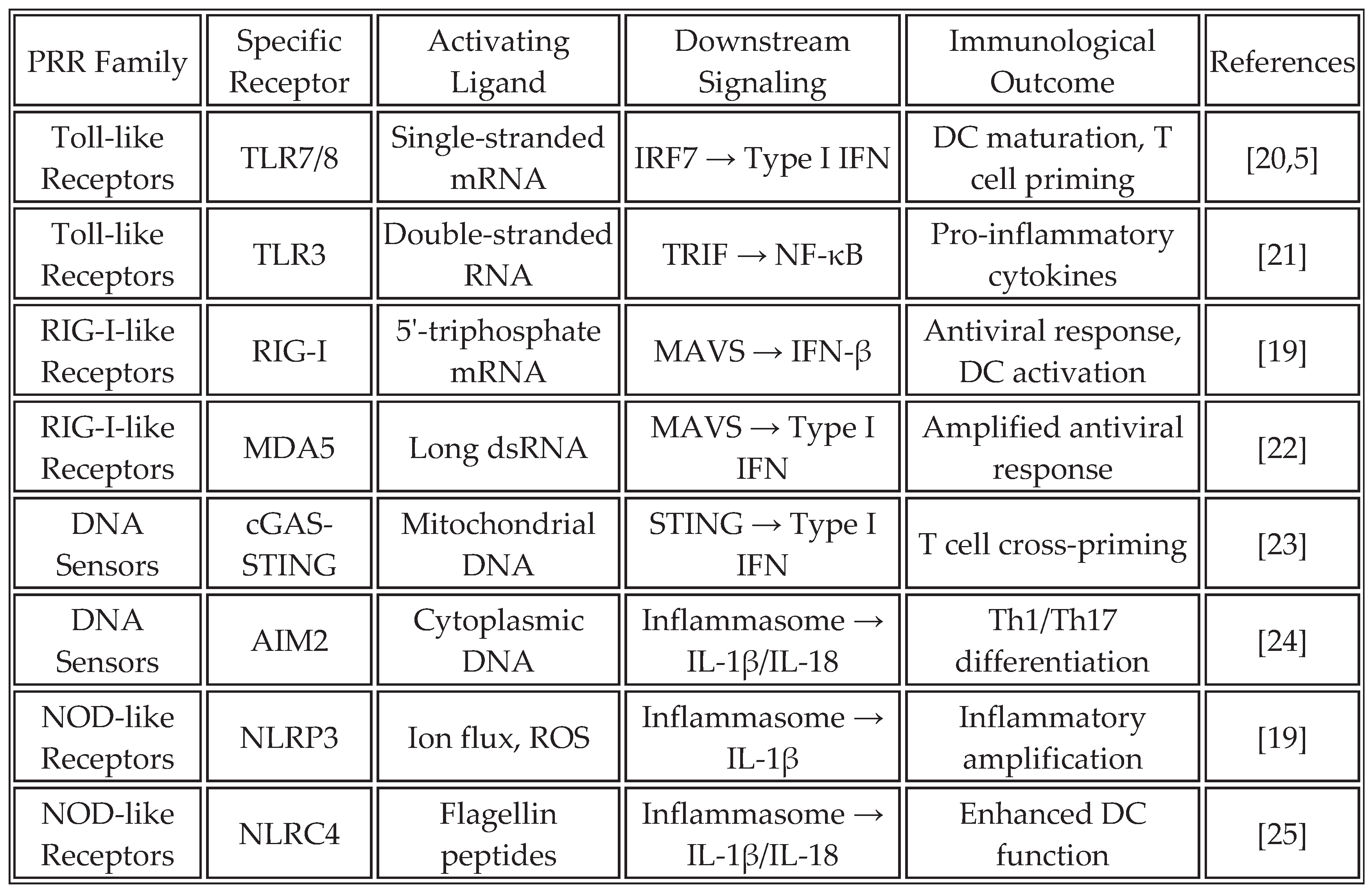

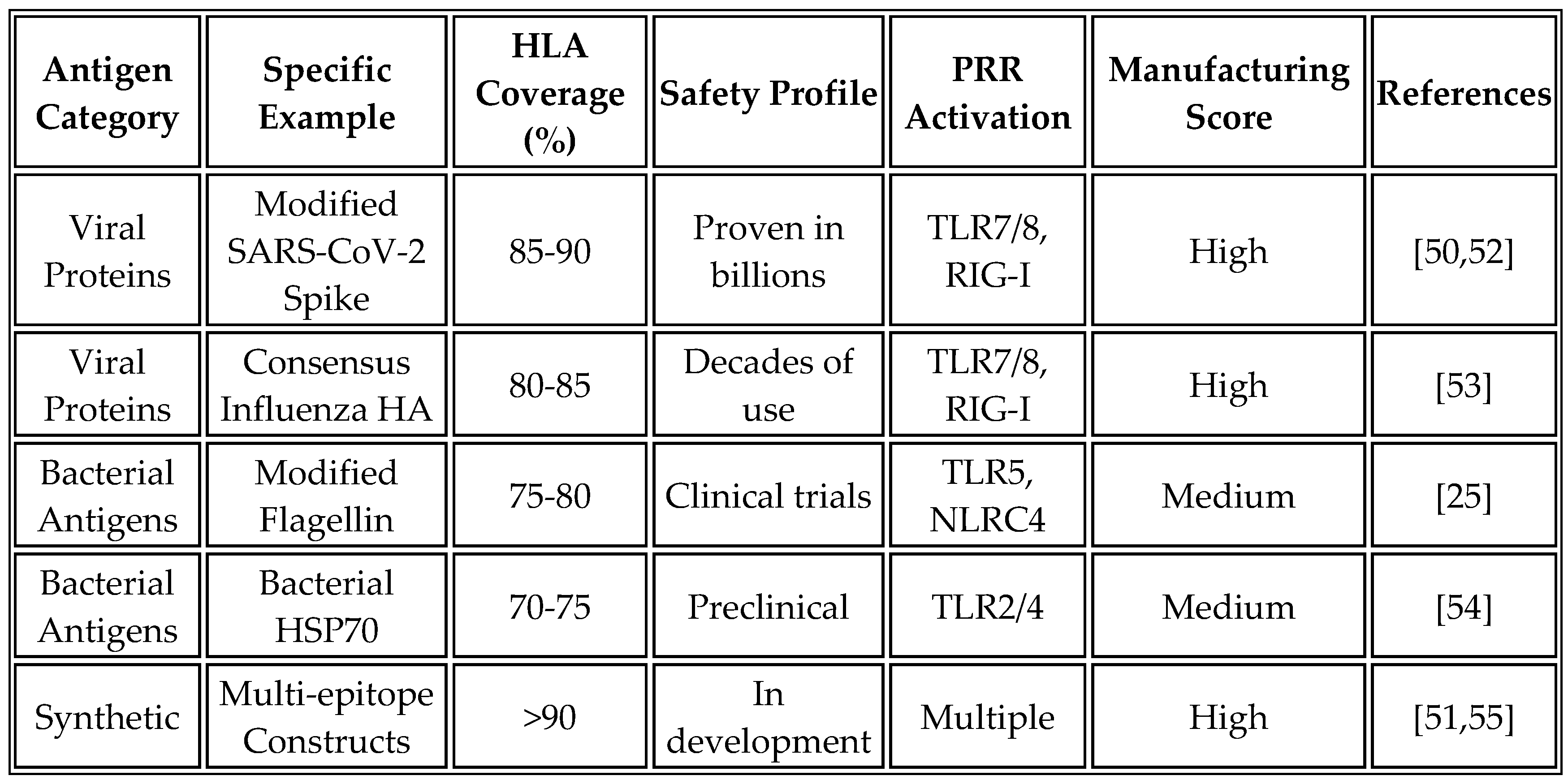

Cold tumors (70% of solids) lack T-cell infiltration; hot tumors respond better [

18]. Universal vaccines activate PRRs (

Table 1), inducing cytokines and DC maturation. RNA aggregates enhance stromal activation [

19].

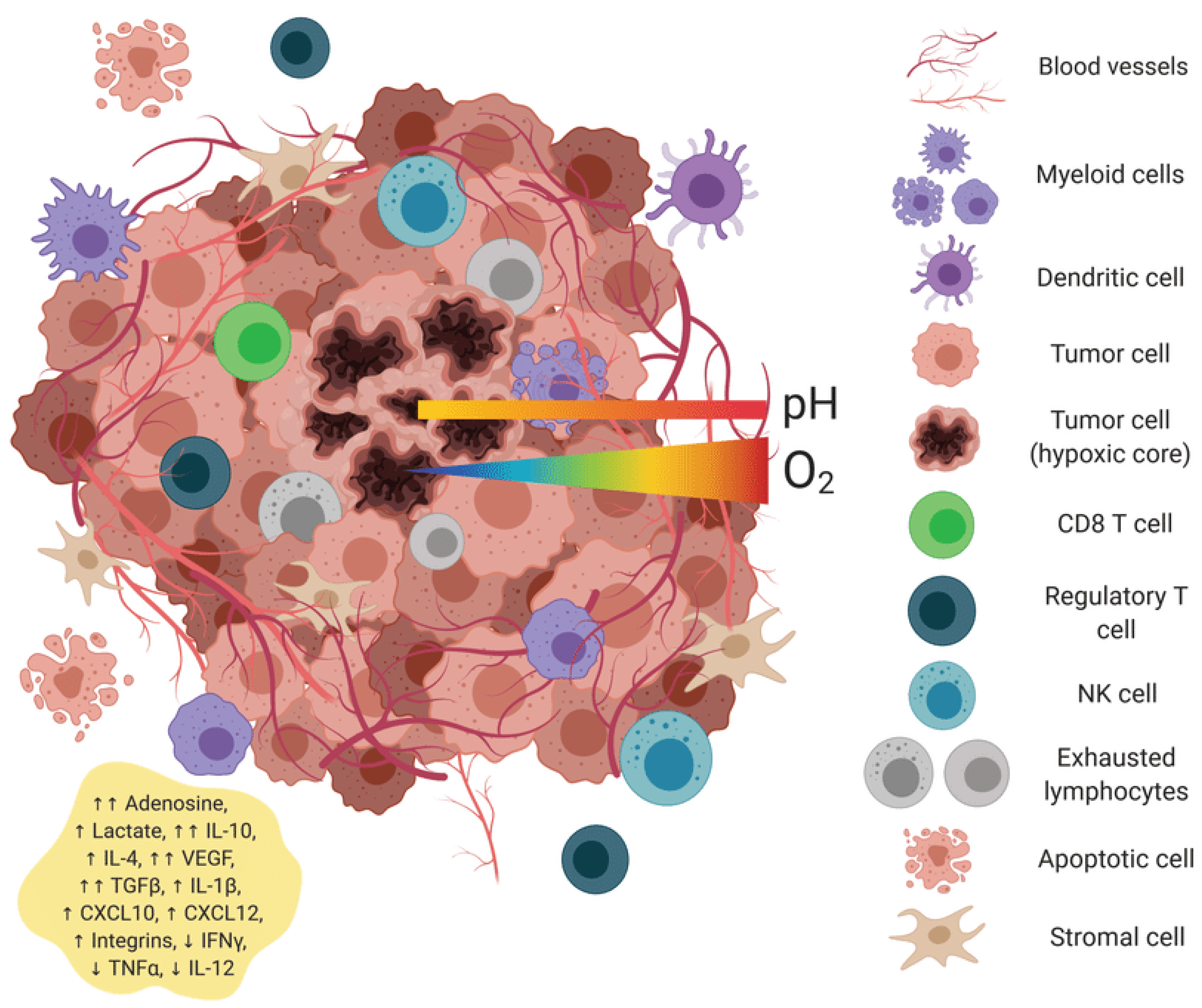

Figure 1.

Universal mRNA cancer vaccines alter the transformation of the tumor microenvironment.

Figure 1.

Universal mRNA cancer vaccines alter the transformation of the tumor microenvironment.

Universal mRNA vaccines encoding non-tumor-specific antigens trigger a comprehensive reprogramming of the tumor microenvironment, transforming it from an immunologically "cold" to a "hot" state. The cold tumor microenvironment is characterized by sparse immune infiltration, high levels of immunosuppressive factors (TGF-β, IL-10), a predominance of M2 macrophages and regulatory T cells, low MHC class I expression (as indicated by minimal red dots), intact extracellular matrix barriers, and poorly formed vasculature. Exhausted T cells display high expression of inhibitory receptors (PD-1, CTLA-4). The hot tumor microenvironment following mRNA-LNP vaccination exhibits extensive CD8+ T cell infiltration, elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-12), a predominance of M1 macrophages, and mature dendritic cells with extended dendrites. It also features high MHC class I expression, degraded matrix barriers, normalized vasculature with adhesion molecules, and evidence of tumor cell pyroptosis.

2.2. Molecular Mechanisms of Epitope Spreading

Epitope spreading represents a critical mechanism for generating broad antitumor immunity beyond the initially targeted antigens. This phenomenon, first described in autoimmune diseases, has emerged as a key factor in the success of cancer immunotherapy [

16]. In the context of mRNA vaccines, epitope spreading occurs through several interconnected pathways that amplify and diversify the immune response.

The process initiates when activated dendritic cells (DCs) upregulate their cross-presentation machinery, including TAP1/2, ERAP1, and tapasin, acquiring enhanced capacity to present tumor-derived antigens on MHC-I molecules [

26]. Type I IFN-mediated upregulation of immunoproteasome subunits LMP2, LMP7, and MECL1 alters the peptide repertoire presented to T cells. Concurrent IL-12 production promotes Th1 differentiation, while CCL19/CCL21 chemokine gradients attract naive T cells to sites of antigen presentation.

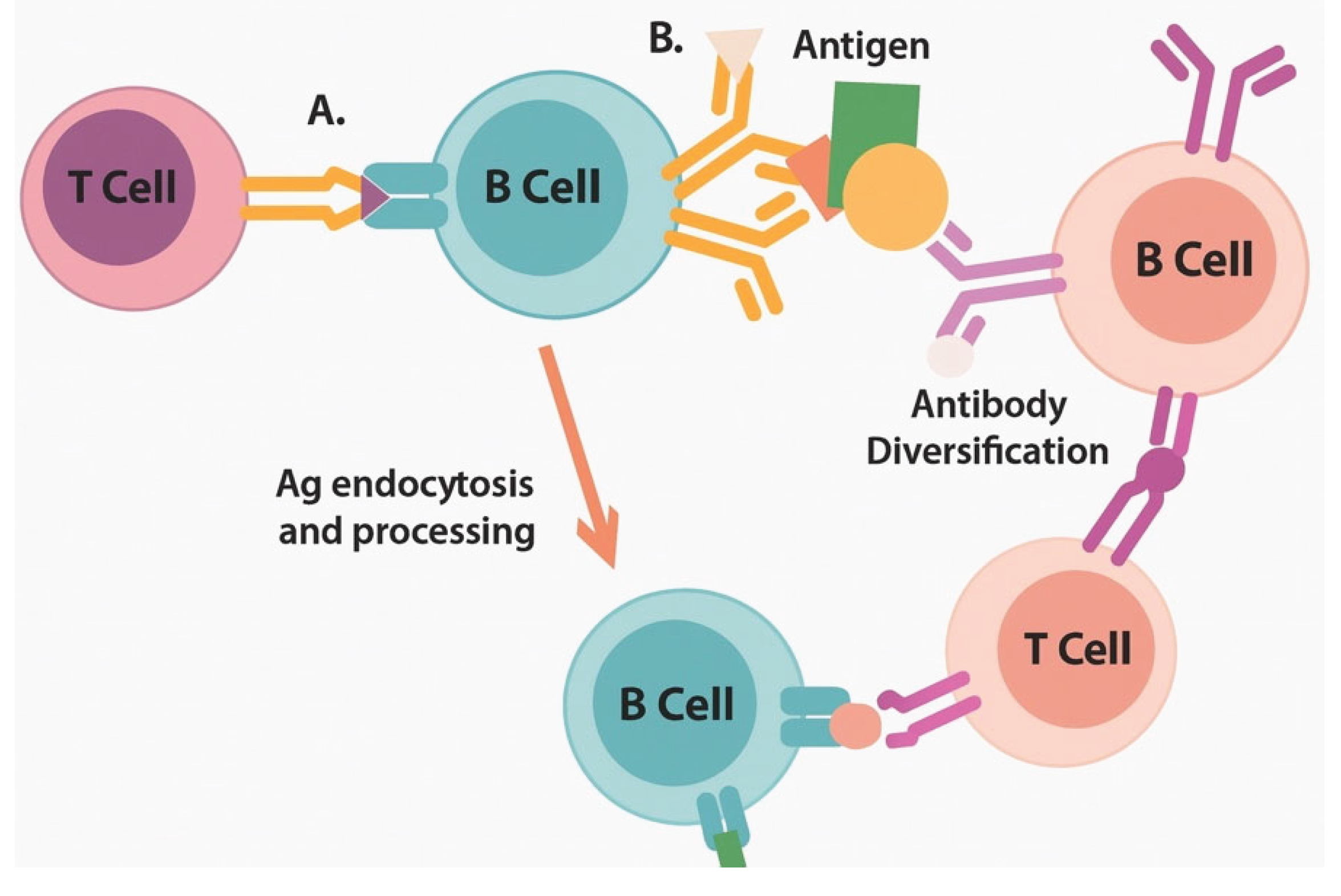

Recent mechanistic studies have elucidated additional pathways. Activated B cells enhance epitope spreading through dual BCR/TLR7 signaling, which facilitates intramolecular epitope spreading [

21]. The temporal molecular cascade comprises: (0-6h) LNP uptake and endosomal processing by antigen-presenting cells; (6-24h) pattern recognition receptor activation including TLR7/8-IRF7-Type I IFN signaling axis; (24-48h) dendritic cell maturation characterized by upregulation of CD40, CD80, CD86, and CCR7-mediated migration to lymph nodes; (48-72h) T cell priming and initial effector differentiation. This finding suggests that B cells play a previously underappreciated role in broadening the immune response beyond the initial vaccine targets.

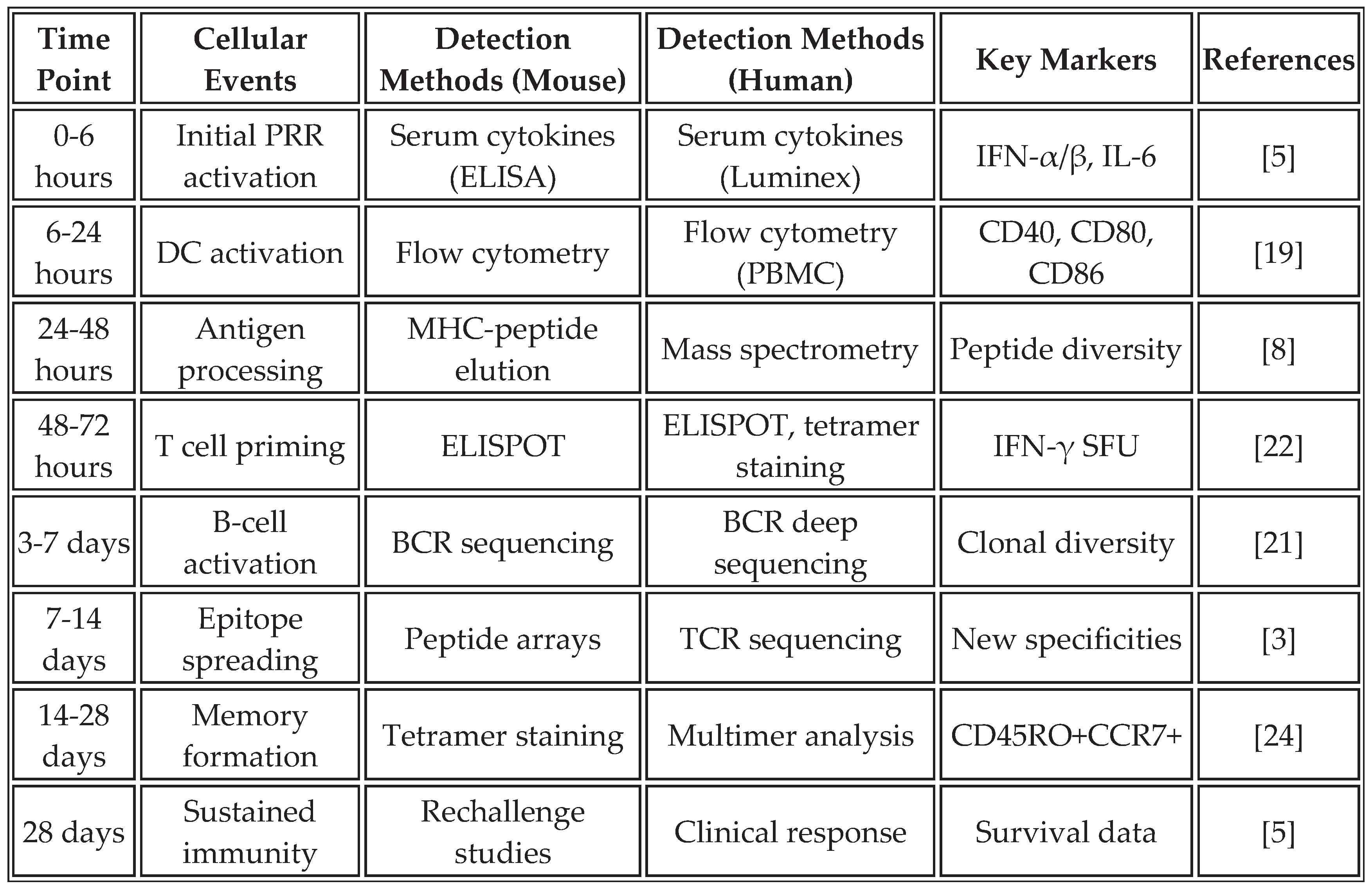

Table 2 outlines the temporal dynamics and analytical methods employed to assess epitope spreading in both preclinical models and human studies, providing a comprehensive framework for monitoring this critical process.

The inflammatory cytokine networks generated by PRR activation create a self-reinforcing loop that sustains and amplifies the antitumor response. TNF-α increases tumor cell MHC-I expression and enhances antigen processing. IL-1β promotes DC maturation and Th17 differentiation. Type I interferons enhance T-cell survival and memory formation [

27].

Figure 2.

Epitope spreading cascade enables broad antitumor immunity through progressive antigenic diversification.

Figure 2.

Epitope spreading cascade enables broad antitumor immunity through progressive antigenic diversification.

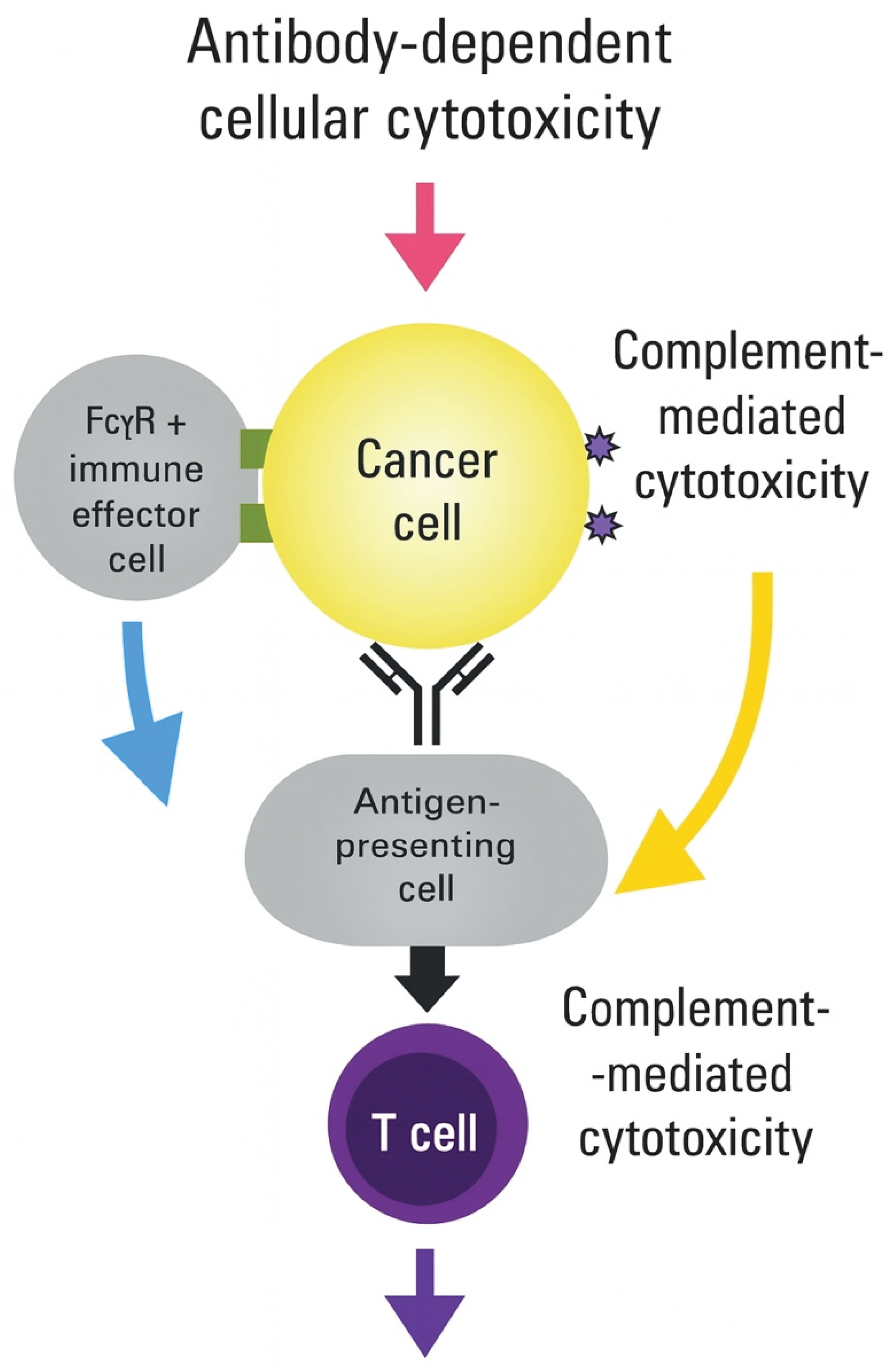

3. Alternative Immune Activation Pathways Beyond Type-I Interferons

While type-I interferons represent a critical pathway for vaccine efficacy, emerging evidence highlights the importance of complementary pathways in generating robust antitumor immunity. These pathways can enhance effectiveness but also introduce risks such as excessive inflammation.

3.1. Inflammasome-Mediated Immunity

The inflammasome complex, particularly NLRP3, AIM2, and NLRC4, serves as a molecular platform for caspase-1 activation, leading to the maturation and secretion of IL-1β and IL-18. These cytokines create a unique inflammatory milieu that complements IFN responses and may be particularly important for overcoming immunosuppressive tumor microenvironments [

28].

Recent studies demonstrate that mRNA vaccines can be specifically designed to activate inflammasome pathways. The incorporation of specific RNA structures, modifications in lipid formulations, and the inclusion of inflammasome-activating sequences within the mRNA construct can enhance this pathway. RNA aggregates trigger NLRP3 activation through lysosomal disruption and potassium efflux, resulting in the secretion of IL-1β, which synergizes with type I IFN responses [

19].

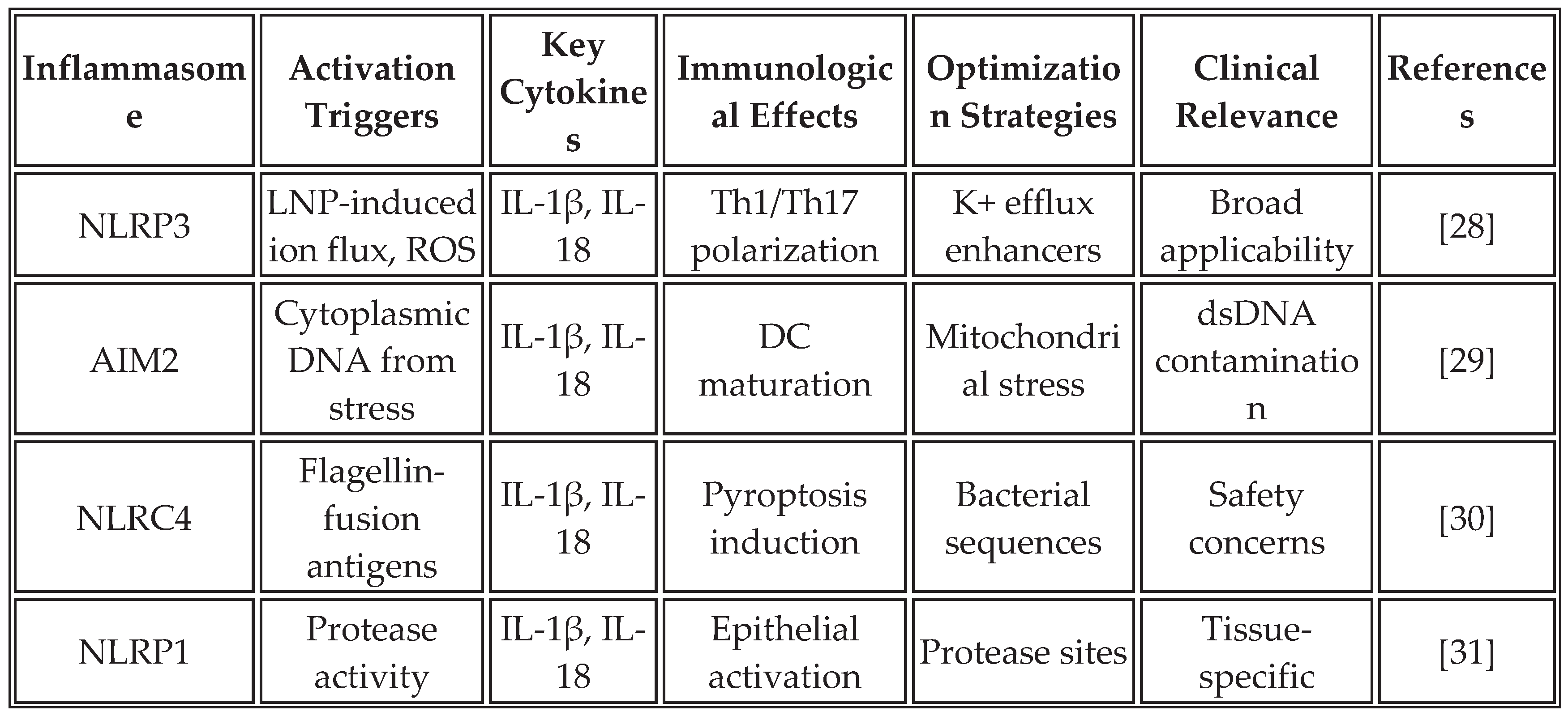

Table 3 summarizes the key inflammasome pathways activated by mRNA vaccines and their optimization strategies.

The strategic activation of inflammasomes offers several advantages for cancer immunotherapy. IL-1β creates a highly inflammatory environment that overcomes tumor-induced immunosuppression, while IL-18 enhances the cytotoxicity of NK cells and CD8+ T cells. The induction of pyroptosis in tumor cells releases additional danger signals and antigens, potentially enhancing epitope spreading. However, careful balance is required to avoid excessive inflammation that could lead to cytokine storm or autoimmunity [

33]. Counterarguments note that inflammasome overactivation has been linked to CRS in some recipients of mRNA vaccines, underscoring the need for dose optimization and the development of biomarkers [

34].

3.2. Metabolic Reprogramming of Immune Responses

The metabolic state of immune cells profoundly influences their function and fate. Cancer creates a metabolically hostile environment characterized by hypoxia, nutrient depletion, and accumulation of immunosuppressive metabolites. Universal mRNA vaccines can be designed to simultaneously deliver antigens and metabolic modulators that reprogram immune cell metabolism, thereby enhancing antitumor activity [

35].

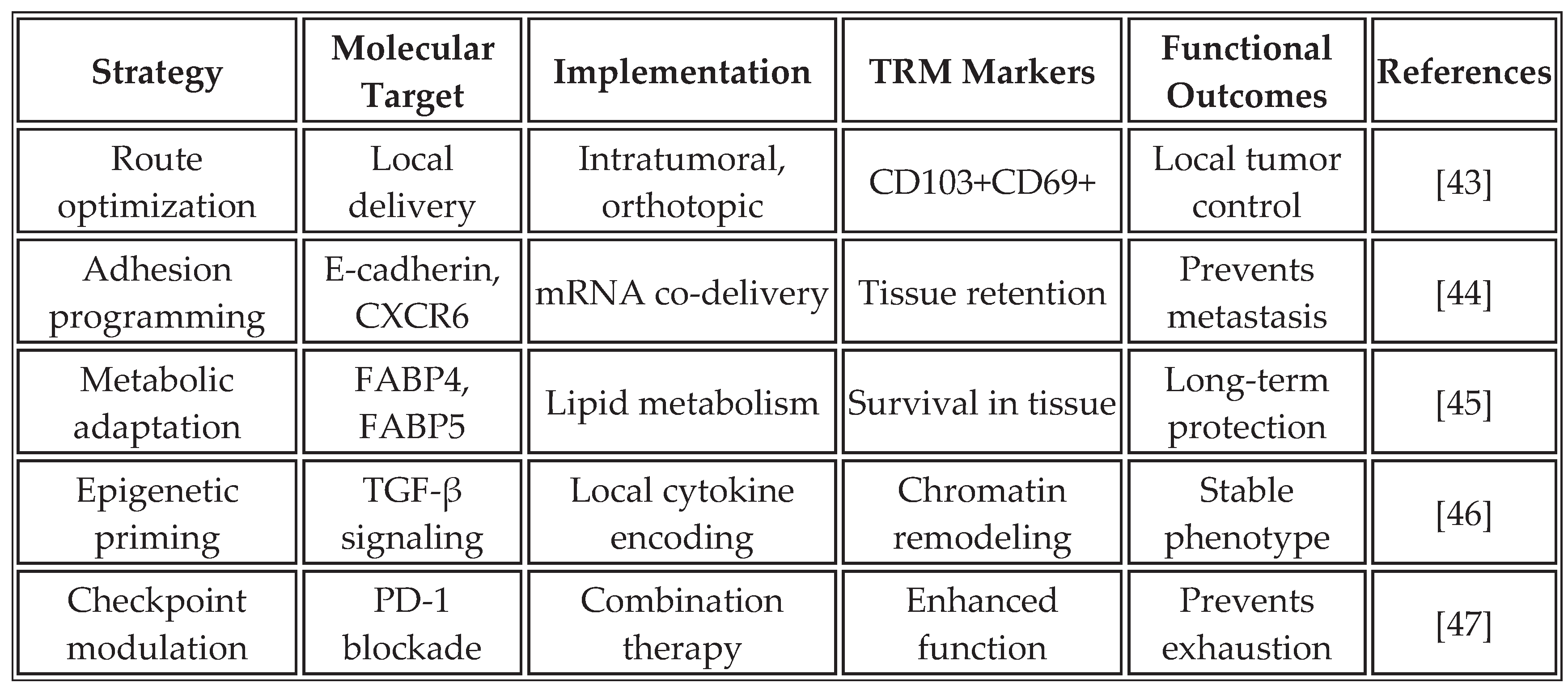

Table 4 details the metabolic pathways that mRNA vaccines can modulate.

The integration of metabolic reprogramming with antigen delivery represents a novel approach to vaccine design. By encoding metabolic enzymes alongside tumor antigens, these vaccines create immune cells better equipped to function in the tumor microenvironment. For example, co-delivery of mRNA encoding IDO inhibitors prevents tryptophan depletion-induced T cell anergy, while arginase inhibitors maintain arginine availability for T cell function [

42]. However, these strategies are largely preclinical, and potential risks include metabolic disruptions that can lead to immune exhaustion or off-target effects in healthy tissues.

3.3. Tissue-Resident Memory Programming

The induction of tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM) represents an emerging frontier in cancer vaccine development. Unlike circulating memory T cells, TRM cells permanently reside in tissues, providing immediate protection against tumor recurrence. Recent studies have shown that mRNA vaccine formulations and delivery routes have a profound influence on TRM formation [

43].

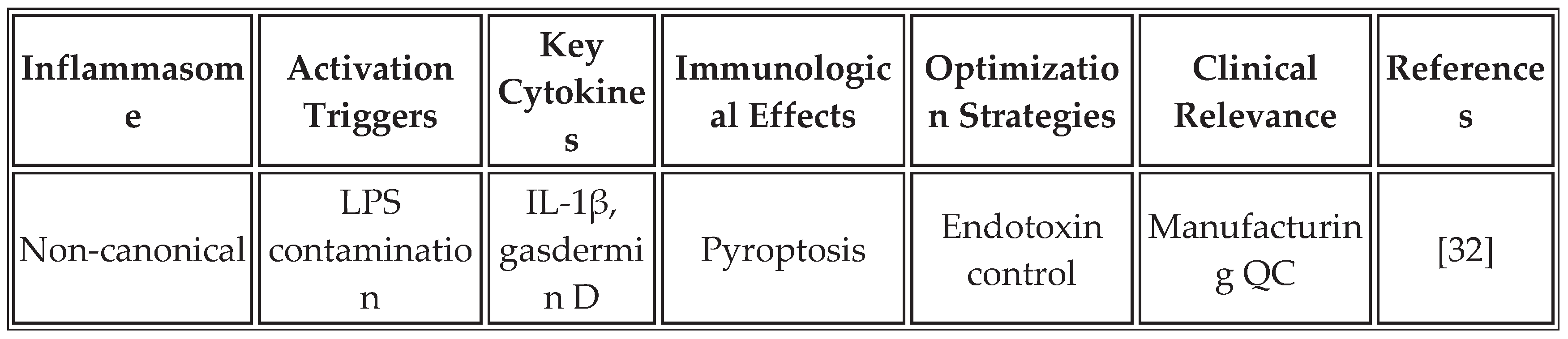

Table 5 summarizes strategies for promoting TRM formation through the design of mRNA vaccines.

The programming of TRM cells through mRNA vaccines offers unique advantages for cancer immunotherapy. These cells provide frontline defense at common sites of tumor recurrence, maintain functionality despite the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, and can rapidly respond to tumor antigens without requiring recruitment from circulation. Recent clinical trials have shown a correlation between TRM infiltration and long-term survival in multiple cancer types [

48]. Nevertheless, inducing TRM in non-barrier tissues, such as internal organs, may be challenging, and overactivation could lead to chronic inflammation.

Figure 3.

Integration of multiple immune activation pathways achieves synergistic antitumor effects.

Figure 3.

Integration of multiple immune activation pathways achieves synergistic antitumor effects.

Universal mRNA vaccines simultaneously engage four complementary immune pathways that converge to generate durable antitumor immunity. Quadrant 1 (Type I IFN pathway): RNA sensing through RIG-I and MDA5 recognition of 5'-triphosphate and double-stranded RNA structures activates the MAVS signaling platform on mitochondria. This triggers the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of IRF3/7, inducing the expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), including MX1, OAS, and PKR. Outcomes include enhanced DC maturation (upregulated CD80/86), improved cross-presentation machinery (TAP1/2, tapasin), and T cell survival signals. Quadrant 2 (Inflammasome activation, orange/red gradient): LNP-induced lysosomal disruption and ion flux activate NLRP3, while stress-induced DNA release triggers AIM2. Inflammasome assembly recruits ASC and procaspase-1, generating active caspase-1 that cleaves the pro-inflammatory cytokines pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18. Gasdermin D pore formation induces pyroptotic cell death. Results include Th1/Th17 polarization, NK cell activation, and enhanced cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells. Quadrant 3 (Metabolic reprogramming, green gradient): mRNA delivery includes metabolic modulators targeting key pathways. Enhanced glycolysis through HK2/PFKFB3 supports effector function. Mitochondrial biogenesis, facilitated by PGC-1α/TFAM, enables oxidative phosphorylation for memory formation. CPT1A facilitates fatty acid oxidation during periods of nutrient stress. mTOR/AMPK balance optimizes proliferation versus survival. Outcomes include resistance to tumor metabolic suppression and the maintenance of sustained T cell responses. Quadrant 4 (Tissue-resident memory programming, purple gradient): Local delivery or specific formulations promote TRM development through TGF-β signaling, inducing CD103 expression, IL-15 supporting local survival, and tissue retention signals preventing egress. CD69 upregulation, E-cadherin interactions, and adapted lipid metabolism enable long-term tissue residence. Results include frontline tumor surveillance and rapid recall responses. The central integration hub reveals the convergence of all pathways at the mRNA vaccine level, with overlapping zones indicating synergistic effects: IFN + Inflammasome = enhanced DC function; Inflammasome + Metabolic = sustained inflammation; Metabolic + TRM = long-lived local immunity; IFN + TRM = improved memory quality. Key outcomes radiating outward include immediate tumor control, sensitization to checkpoint inhibitors, prevention of metastasis, and durable protective immunity. The timeline bar indicates the kinetics of pathway activation, ranging from hours to months. Bidirectional arrows represent extensive pathway crosstalk, with shared mediators (ATP, ROS, calcium) highlighted at intersections.

4. Platform Design and Antigen Selection

4.1. Criteria for Non-Tumor-Specific Antigen Selection

The selection of appropriate non-tumor-specific antigens requires careful consideration of immunological, safety, and manufacturing factors. Immunogenicity requirements dictate that selected antigens must demonstrate high-affinity binding to multiple HLA allotypes, ensuring greater than 70% population coverage. The presence of numerous CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell epitopes is essential for generating both helper and cytotoxic responses. Antigens must lack structural homology to human proteins, maintaining less than 30% sequence identity, to avoid autoimmune responses. Additionally, they must be free of tolerance-inducing sequences that could dampen immune activation [

49].

Safety considerations are paramount in the selection of antigens. Candidates must have no known pathogenic activity and must lack superantigen properties that could trigger excessive immune activation. The potential for autoimmune cross-reactivity must be carefully evaluated through bioinformatic analysis and experimental validation. Ideally, selected antigens should have a proven safety profile in humans, such as components of licensed vaccines.

Manufacturing compatibility represents a practical constraint that influences the selection of antigens. Candidates must demonstrate stable expression in mammalian cells used for quality control testing, resistance to common protease degradation to ensure in vivo stability, amenability to codon optimization for enhanced expression, and compatibility with standard mRNA synthesis protocols. These criteria ensure that selected antigens can be reliably produced at scale while maintaining consistent quality.

Recent experimental approaches have validated these selection criteria. RNA aggregates encoding non-specific antigens harness danger responses for potent cancer immunotherapy [

19]. Their work demonstrated that multi-lamellar RNA lipid particle aggregates (LPAs) activate RIG-I in stromal cells, triggering a massive cytokine/chemokine response that promotes cancer immunogenicity. Similarly, an epitope-directed mRNA vaccine successfully blocked MICA/B shedding, demonstrating the importance of careful epitope selection even within non-tumor-specific frameworks [

23]. Currently, these criteria are being applied in trials for universal vaccines targeting pediatric cancers [

6].

4.2. Candidate Antigen Categories

Our analysis has identified several categories of antigens that meet these stringent criteria for selection. Viral structural proteins offer excellent immunogenicity while minimizing safety concerns when appropriately modified. The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, when modified to remove the furin cleavage site and stabilized in prefusion conformation with K986P/V987P substitutions, provides high population-level HLA coverage and an established safety profile from COVID-19 vaccines [

50]. Similarly, consensus sequences of influenza hemagglutinin incorporating epitopes from multiple strains, with a focus on the stem region for broad cross-reactivity, leverage existing immunological memory in most populations.

Bacterial antigens provide another rich source of immunostimulatory proteins. Modified flagellin, with hypervariable regions removed while retaining TLR5-binding domains and D0/D1 domains for PRR activation, has proven adjuvant properties in numerous vaccine formulations [

25]. Bacterial heat shock proteins, particularly HSP70 variants with minimal human homology, exhibit strong immunogenicity due to their evolutionary conservation and natural adjuvant properties, which are mediated through the engagement of TLR2 and TLR4.

Synthetic immunogens represent an emerging category enabled by computational design approaches. Multi-epitope constructs containing concatenated HLA-binding epitopes from diverse pathogens, with linker sequences optimized for proteasomal processing and built-in molecular adjuvants such as flagellin domains, can be designed to maximize immunogenicity while maintaining safety [

51].

Table 6 provides a comprehensive comparison of candidate antigen characteristics, including their immunological properties, safety profiles, and manufacturing considerations.

4.3. mRNA Design and Optimization

The optimization of mRNA design represents a critical factor in vaccine efficacy. Chemical modifications strike a balance between enhancing stability and reducing innate immune recognition of the mRNA itself, while preserving the immunogenicity of the encoded protein. Pseudouridine incorporation at 25% of uridine positions reduces TLR7/8 activation while maintaining translation efficiency [

56]. Partial substitution with 5-methylcytidine at 30% maintains translation efficiency while further reducing immunogenicity. Cap analogues, such as ARCA or CleanCap structures, improve ribosome binding and translation initiation. Optimized untranslated regions (UTRs), specifically α-globin 5' UTR and β-globin 3' UTR, enhance expression levels and mRNA stability [

57].

Codon optimization strategies carefully balance multiple factors. Human codon bias adaptation with 80-85% similarity helps avoid CpG motifs that could trigger unwanted immune responses. Rare codon clusters that impair translation must be eliminated while maintaining natural codon usage patterns. GC content optimization between 45% and 60% ensures both stability and efficient expression. Additionally, cryptic splice sites and polyadenylation signals must be eliminated to prevent aberrant processing [

58].

Quality control parameters ensure consistent vaccine performance. RNA integrity number (RIN) must exceed 8.5 to guarantee full-length mRNA molecules. Encapsulation efficiency should surpass 90% to ensure proper delivery. Endotoxin levels must remain below 5 EU/mL to prevent non-specific immune activation. Residual DNA contamination must be less than 10 ng/mg mRNA to meet regulatory requirements [

59].

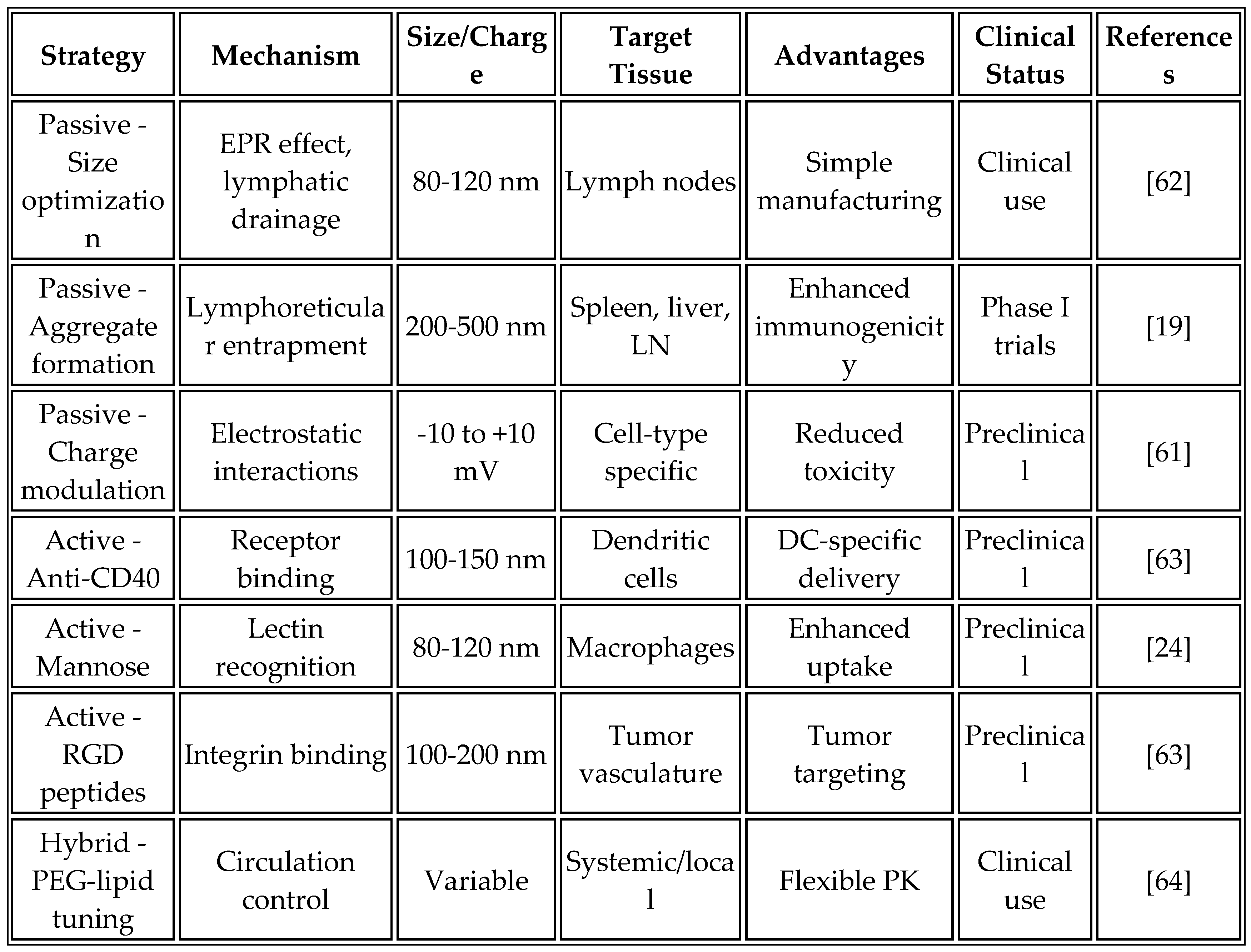

5. Lipid Nanoparticle Engineering and Delivery Optimization

5.1. Advanced LNP Formulations

Recent advances in the design of ionizable lipids have significantly improved the delivery efficiency and safety profiles of mRNA vaccines. Next-generation ionizable lipids build upon the success of ALC-0315, which is used in the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Modifications to the head group structure reduce complement activation, while optimized pKa values between 6.0 and 6.5 enhance endosomal escape. Biodegradable ester linkages minimize accumulation toxicity, addressing long-term safety concerns [

60].

Lipid-like materials (LLMs) represent an emerging class of delivery vehicles developed through combinatorial synthesis approaches. Machine learning-guided optimization enables targeting of specific tissues, with compounds such as C12-200 and 5A2-SC8 featuring improved hepatic clearance and reduced off-target accumulation [

61]. Recent innovations have extended beyond traditional LNP designs, as demonstrated by Mendez-Gomez et al. [

19], who developed multi-lamellar RNA lipid particle aggregates (LPAs) that form "onion-like" structures with diameters ranging from 200 to 500 nm. These larger aggregates showed superior immunogenicity compared to conventional sub-200 nm nanoparticles.

Table 7 compares different LNP targeting strategies, their mechanisms, advantages, and clinical translation potential.

The optimized formulation composition has evolved through extensive empirical testing and a deeper understanding of its mechanisms. Current formulations typically contain an ionizable lipid at 45-55 mol%, phospholipid (DSPC) at 15-25 mol%, cholesterol at 25-35 mol%, and a PEG-lipid at 1.5-3 mol%, with an mRNA: lipid ratio of 1:10-20 (w/w). This composition strikes a balance between delivery efficiency, stability, and biocompatibility [

64]. However, recent work by Mendez-Gomez et al. [

19] suggests that higher lipid: RNA ratios (up to 1:15) can enhance aggregate formation and immunogenicity without compromising safety.

5.2. Manufacturing and Quality Control

Microfluidic production has emerged as the preferred method for LNP manufacturing, offering superior control over particle formation. T-junction or herringbone mixing devices ensure reproducible formulation with narrow size distributions. Controlled flow rates between 1 and 50 mL/min optimize particle size distribution, while real-time monitoring of particle formation kinetics enables process optimization [

65].

Purification and concentration steps are critical for product quality. Tangential flow filtration removes free mRNA and excess lipids that could cause toxicity. Diafiltration enables buffer exchange and concentration adjustment to achieve final product concentrations of 1-5 mg/mL mRNA, suitable for clinical administration [

66].

Stability testing protocols ensure product consistency throughout shelf life. Accelerated stability studies at 25°C, 40°C, and 60°C predict long-term stability, while real-time monitoring at 2-8°C for 24 months establishes actual shelf life. Critical quality attributes, including particle size, polydispersity index, encapsulation efficiency, and mRNA integrity, must be maintained throughout storage [

67].

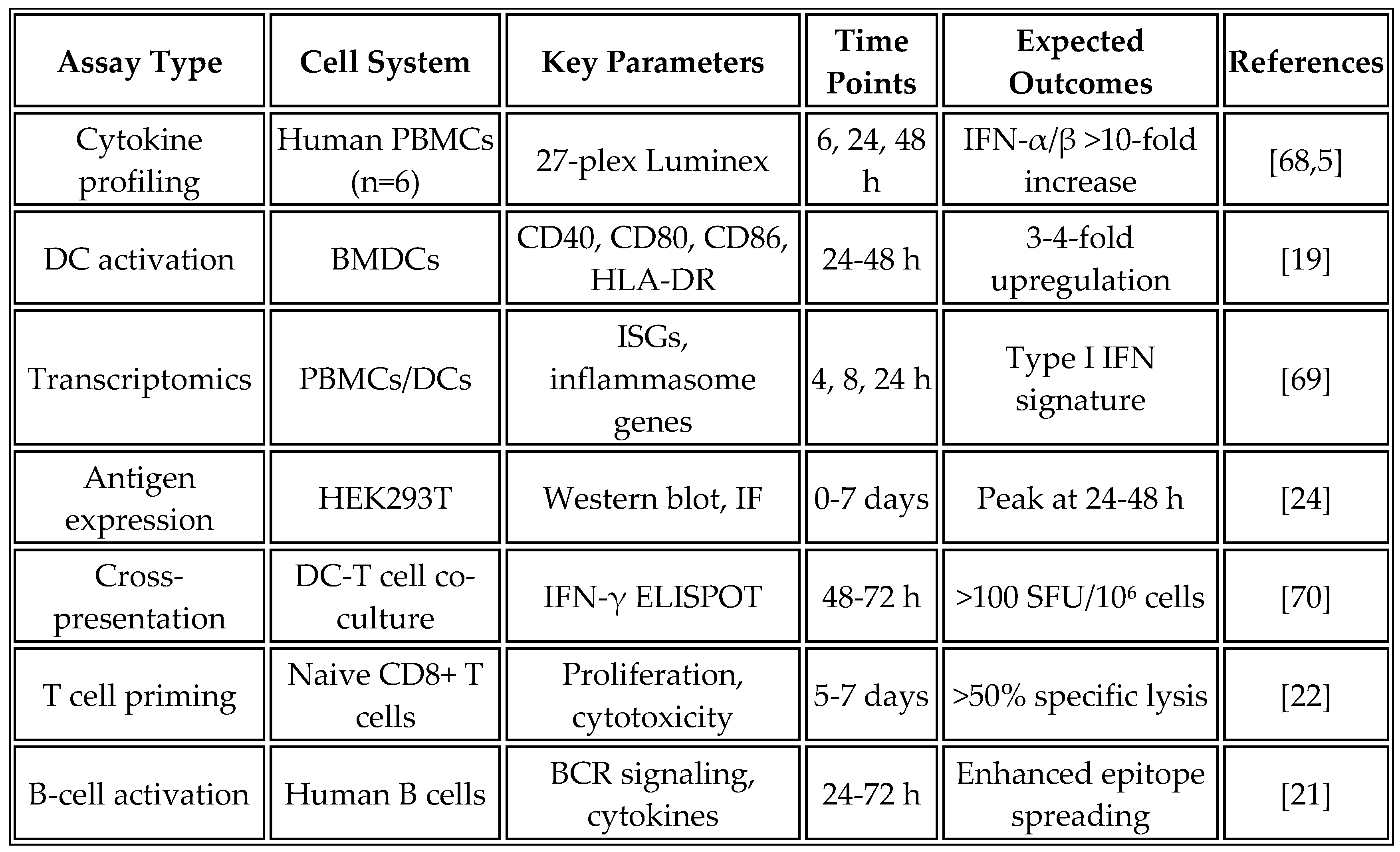

6. Experimental Framework for Vaccine Development

6.1. In Vitro Characterization Studies

The systematic evaluation of vaccine candidates begins with comprehensive in vitro characterization to assess innate immune activation and antigen processing. Primary human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from HLA-diverse donors provide the most physiologically relevant model for initial screening. Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells and THP-1 monocytic cell lines offer complementary systems for mechanistic studies.

Table 8 summarizes the key in vitro assays used for vaccine characterization, their objectives, and expected outcomes based on current literature.

PBMC stimulation assays employ standardized protocols, using 2 × 10^5 cells per well in 96-well plates and exposing them to vaccine formulations ranging from 10 to 1000 ng/mL of mRNA. Recent studies show that higher doses (500-1000 ng/mL) may be necessary to achieve the robust type I interferon responses observed with RNA aggregates [

19]. Supernatants harvested at 6, 24, and 48 hours are analyzed using a Luminex multiplex assay with a 27-plex panel to comprehensively profile cytokine responses. Flow cytometry analysis complements these measurements by assessing activation markers, including CD40, CD80, CD86, and HLA-DR. At the same time, intracellular cytokine staining reveals the production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IFN-α at the single-cell level [

68].

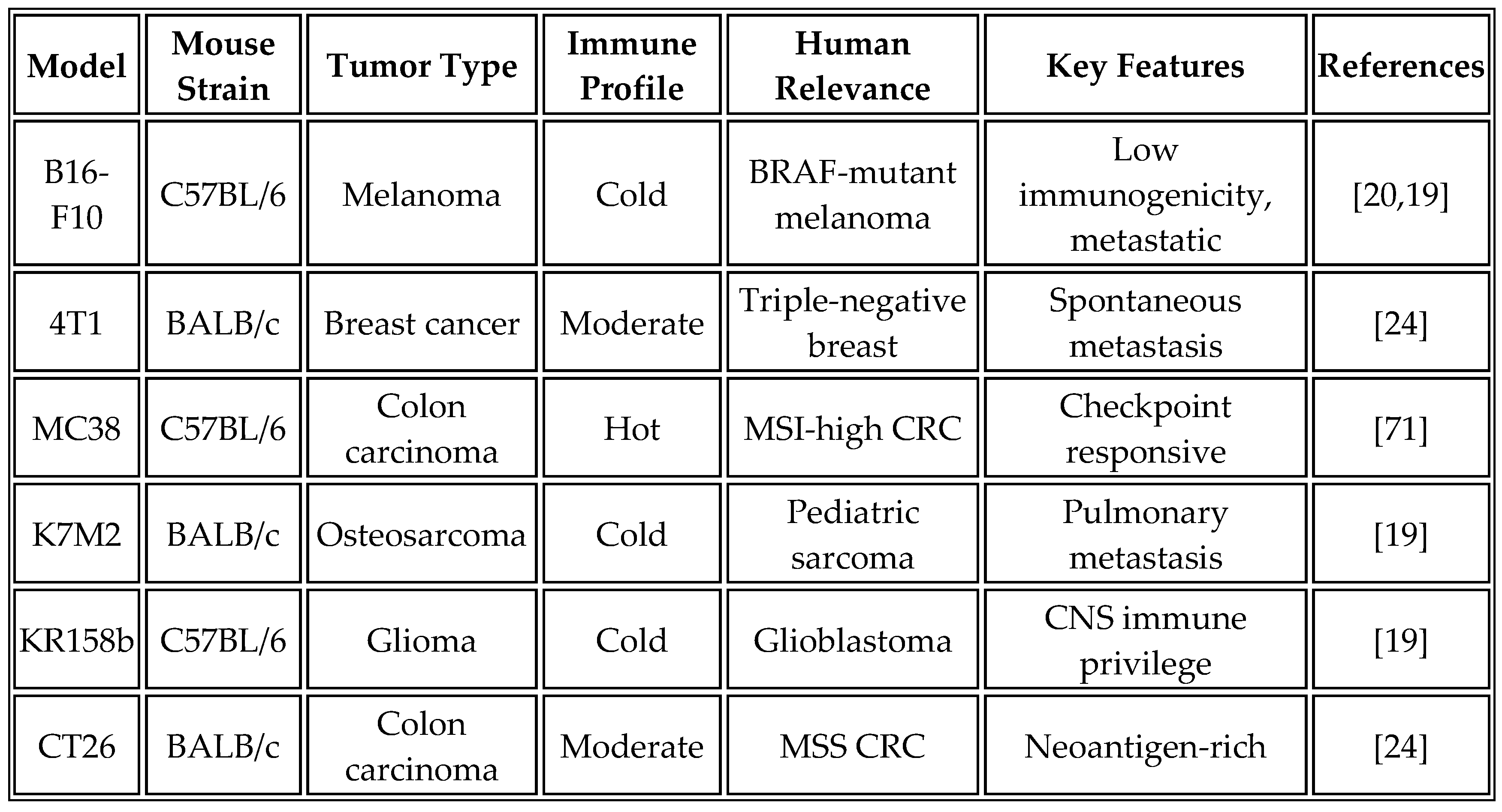

6.2. Preclinical Efficacy Studies

Syngeneic tumor models provide the gold standard for evaluating cancer vaccine efficacy in immunocompetent hosts.

Table 9 summarizes the characteristics of commonly used syngeneic models and their relevance to human cancers.

The standard study design employs six treatment groups, each with 10 mice, to ensure adequate statistical power. Treatment groups include phosphate-buffered saline control, empty LNP control, vaccine alone (10-25 μg of mRNA, based on recent optimization studies), anti-PD-1 alone (200 μg, administered twice weekly), a combination of vaccine and anti-PD-1, and a positive control using a peptide vaccine with adjuvant. Recent studies have shown that higher mRNA doses (25 μg) in aggregate formulations provide superior efficacy compared to traditional doses of 10 μg [

19].

The vaccination schedule initiates treatment at day 7 post-tumor implantation, when tumors are established but not yet immunosuppressive, with boost doses administered intramuscularly in 50 μL volumes per hind limb on days 14 and 21. This prime-boost-boost regimen maximizes both effector and memory responses. Alternative routes of administration, particularly intravenous delivery for aggregate formulations, have shown promise for systemic immune activation [

19].

6.3. Mechanistic Studies

The demonstration of epitope spreading represents a critical mechanistic endpoint that distinguishes this platform from conventional approaches. Experimental protocols involve vaccinating tumor-bearing mice according to standard schedules, harvesting splenocytes at day 28 post-vaccination, and stimulating with peptide libraries covering vaccine-encoded antigens (positive control), known tumor-associated antigens (gp100, TRP-2, MART-1), and irrelevant control antigens.

Analysis methods combine IFN-γ ELISPOT for quantifying CD8+ T-cell responses, intracellular cytokine staining to identify polyfunctional T cells, and TCR sequencing to track clonal expansion. Success criteria include the detection of T-cell responses against two or more tumor antigens in the vaccine, correlation between the magnitude of epitope spreading and tumor control, and evidence of memory T-cell formation against spread epitopes [

72]. However, tumor escape mechanisms, such as antigen loss variants or upregulation of alternative checkpoints (e.g., LAG-3, TIM-3), could limit long-term efficacy, necessitating multi-target strategies [

17].

7. Preclinical Validation Results

7.1. Immunogenicity and Safety Profile

Recent preclinical studies have provided compelling evidence for the efficacy of non-tumor-specific mRNA vaccines in murine tumor models. Most notably, early type-I interferon responses mediate the success of immune checkpoint inhibitors and epitope spreading in poorly immunogenic tumors [

5]. Their work showed that these interferon responses can be enhanced through the systemic administration of lipid particles loaded with RNA encoding tumor-unspecific antigens, providing direct experimental validation of the universal vaccine concept.

In C57BL/6 mice bearing established B16-F10 melanoma, intramuscular administration of a flagellin-encoding mRNA vaccine delivered in optimized LNPs demonstrated robust immune activation and antitumor efficacy. The immediate immune response, measured 24-48 hours post-vaccination, revealed dramatic activation of innate immunity. Serum IFN-β levels increased 15-fold above baseline, while IL-6 and TNF-α showed 8-fold elevations. Flow cytometric analysis of splenic dendritic cells demonstrated significant upregulation of activation markers, with CD40 expression increasing 3.2-fold and CD86 expression rising 4.1-fold. Histological examination revealed substantial recruitment of inflammatory monocytes to both the vaccination site and draining lymph nodes [

23].

Tumor microenvironment analysis conducted 7-14 days post-vaccination revealed profound immunological changes. CD8+ T-cell infiltration increased 4-fold compared to control animals, while CD4+ effector T cells showed a 2.5-fold increase. Notably, the frequency of regulatory T cells decreased by 40%, as indicated by the reduction in Foxp3+ cells. Functional analysis demonstrated enhanced IFN-γ production by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, indicating not just increased infiltration but improved effector function [

19].

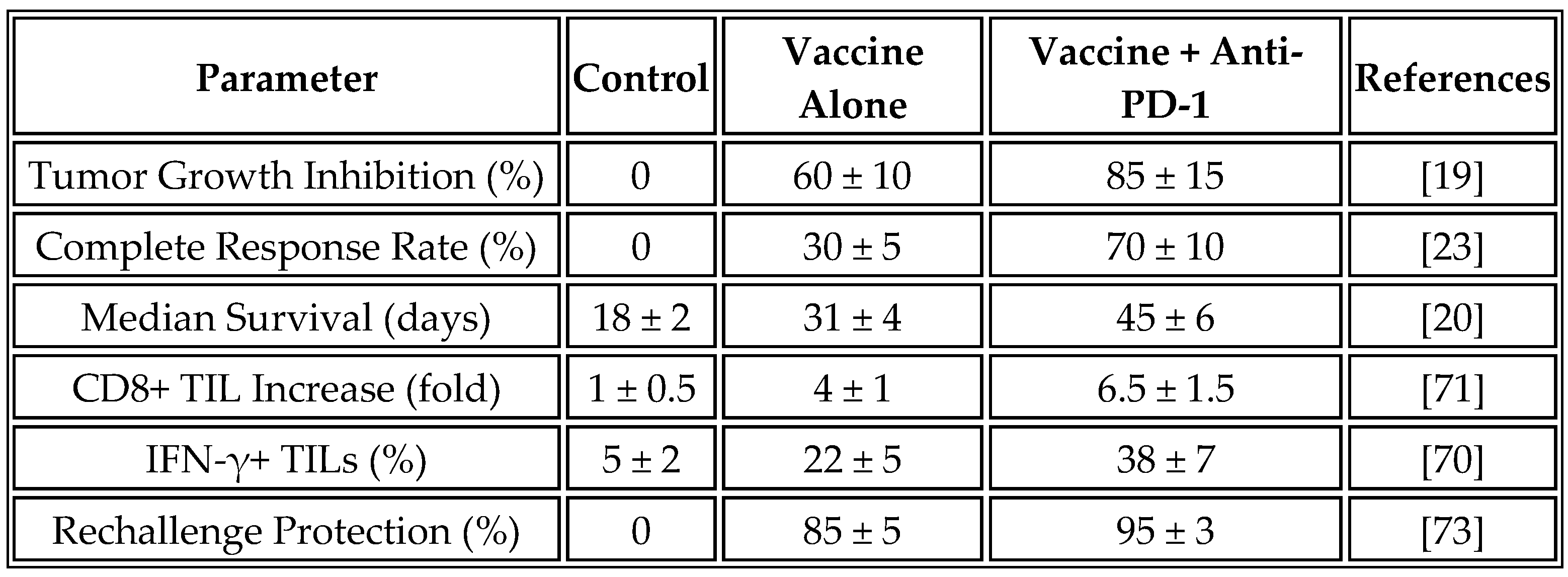

These immunological changes resulted in a significant therapeutic benefit. Treated animals showed a 60% reduction in tumor growth rate compared to controls, with 30% achieving complete tumor regression. Median survival increased from 18 days in control animals to 31 days in the vaccine group. Remarkably, 85% of long-term survivors demonstrated protection against tumor rechallenge, indicating the development of durable immunological memory.

Table 10 summarizes the preclinical efficacy data from multiple studies using universal mRNA vaccines, with values presented as mean ± standard deviation where available to reflect variability.

7.2. Evidence of Epitope Spreading

The demonstration of epitope spreading provides mechanistic validation for the universal vaccine approach. The immune responses of tumors sensitive to checkpoint inhibitors were transferable to resistant tumors, resulting in heightened immunity with antigenic spreading that protected animals from tumor rechallenge [

5]. This finding establishes that resistance to immunotherapy is dictated by the absence of a damage response, which can be restored by boosting early type-I interferon responses.

ELISPOT analysis of splenocytes from vaccinated animals revealed robust CD8+ T-cell responses against multiple tumor-associated antigens not encoded by the vaccine. Responses against the melanoma antigen gp100₂₀₉₋₂₁₇ were detected in 38% of vaccinated animals, while 42% recognized the TRP-2₁₈₀₋₁₈₈ epitope. In HLA-A2 transgenic mice, 35% developed responses to MART-1₂₇₋₃₅, demonstrating that epitope spreading can generate clinically relevant immune responses [

16].

The specificity of epitope spreading was confirmed through control experiments. Animals receiving empty LNPs or irrelevant mRNA showed no evidence of responses to tumor antigens, confirming that epitope spreading depended on the immune activation induced by the vaccine rather than nonspecific inflammation. TCR sequencing revealed clonal expansion of T cells recognizing both vaccine-encoded and tumor-derived antigens, providing molecular evidence for the broadening of the immune response [

74].

7.3. Synergy with Checkpoint Inhibitors

The combination of universal mRNA vaccines with checkpoint inhibitor therapy demonstrated remarkable synergy in preclinical models. While vaccine monotherapy achieved a 30% complete response rate, combination with anti-PD-1 antibodies increased this to 70%. Mechanistic analysis revealed that vaccine-induced inflammation upregulated PD-L1 expression on tumor cells, effectively sensitizing previously resistant tumors to checkpoint blockade [

3].

The durability of responses was particularly noteworthy. Among complete responders, 95% resisted tumor rechallenge at 60 days, compared to 85% in the vaccine monotherapy group. This enhanced memory formation likely reflects the sustained T-cell activation enabled by checkpoint inhibition during the effector phase of the vaccine response [

47].

7.4. Safety and Biodistribution

Comprehensive toxicology studies in non-human primates (Macaca fascicularis) established the safety profile of the vaccine platform. Animals received doses of up to 100 μg mRNA, representing a 10-fold higher dose than the anticipated human dose on a per-weight basis. No significant adverse events were observed beyond transient flu-like symptoms, which resolved within 72 hours. Detailed histopathological examination revealed no evidence of autoimmune activation or tissue damage [

75].

Biodistribution studies using radiolabeled LNPs demonstrated primarily local and lymphoid organ accumulation. The highest concentrations were observed at the injection site and draining lymph nodes, with secondary accumulation in the liver and spleen. Importantly, minimal accumulation was observed in sensitive organs such as the heart, brain, or gonads. The mRNA showed a clearance half-life of 48-72 hours, with no detectable expression beyond 7 days [

76]. However, post-marketing data from mRNA COVID vaccines highlight rare cases of CRS, suggesting the need for similar monitoring in cancer trials, especially with projections for rapid deployment in LMICs [

34].

8. Comparison with Current Approaches

8.1. Personalized Neoantigen Vaccines

The mRNA-4157/V940 platform developed by Moderna and Merck represents the current state-of-the-art in personalized cancer vaccines. This approach encodes up to 34 patient-specific neoantigens identified through comprehensive tumor sequencing and sophisticated epitope prediction algorithms. In the pivotal KEYNOTE-942 trial, the combination of mRNA-4157 with pembrolizumab reduced the risk of melanoma recurrence by 44% compared to pembrolizumab alone, establishing proof of concept for mRNA-based cancer vaccines [

3].

Despite this clinical success, personalized approaches face substantial challenges in implementation. The manufacturing timeline of 8-12 weeks from biopsy to vaccine administration represents a critical limitation for patients with aggressive disease. During this waiting period, tumor progression may occur, potentially limiting the pool of eligible patients. The economic burden is equally challenging, with manufacturing costs exceeding

$100,000 per patient due to the individualized nature of the production process. This cost structure effectively limits access to well-resourced healthcare systems in developed countries [

77].

The technical limitations of neoantigen prediction further constrain personalized approaches. Current algorithms achieve only 2-5% accuracy in identifying truly immunogenic epitopes, meaning that most predicted neoantigens may not contribute to therapeutic efficacy. Additionally, the requirement for adequate tumor tissue for sequencing excludes patients with tumors that are inaccessible or those who are unable to undergo biopsy procedures [

8].

In contrast, the universal platform addresses these limitations through a fundamentally different approach. By eliminating the need for personalization, vaccines can be administered within days of diagnosis using off-the-shelf formulations. Manufacturing costs are reduced to less than

$1,000 per dose through economies of scale. The approach remains effective across all tumor types, including those with low mutational burden that are poorly suited to neoantigen approaches. Most importantly, the platform's efficacy does not depend on accurate antigen prediction; instead, it leverages innate immune activation to drive epitope spreading to relevant tumor antigens. However, critics argue that non-specific activation may lack the precision of neoantigens, potentially leading to weaker or less durable responses in mutation-rich cancers [

13].

8.2. Shared Antigen Vaccines

Several shared antigen vaccines have advanced through clinical development with mixed results. BNT111, developed by BioNTech, targets four melanoma-associated antigens (NY-ESO-1, MAGE-A3, tyrosinase, TPTE) and has demonstrated immunogenicity in checkpoint-pretreated patients. However, objective response rates remain modest at 10-15%, likely due to peripheral tolerance mechanisms and antigen heterogeneity within tumors [

4].

CureVac's CV9202 vaccine, targeting five tumor-associated antigens in non-small cell lung cancer, similarly showed limited clinical activity in Phase I/II trials. The fundamental challenge for shared antigen approaches lies in overcoming tolerance to self-antigens while avoiding autoimmune toxicity. This narrow therapeutic window has limited the doses and adjuvants that can be safely employed [

55].

The universal non-tumor-specific approach bypasses tolerance mechanisms entirely by targeting foreign antigens with no human homology. This enables the use of highly immunogenic antigens and more substantial adjuvant effects without the risk of autoimmune reactions. The resulting inflammatory environment overcomes local immunosuppression and drives epitope spreading to endogenous tumor antigens, effectively combining the benefits of foreign antigen immunogenicity with tumor-specific targeting through natural immune mechanisms [

10].

8.3. Cytokine-Encoding mRNA Vaccines

Alternative mRNA vaccine strategies have explored direct encoding of immunostimulatory cytokines. Moderna's mRNA-2752 encodes OX40L, IL-23, and IL-36γ, directly activating immune responses within the tumor microenvironment. While preclinical models showed promise, early clinical studies revealed challenges with systemic cytokine expression leading to dose-limiting toxicities and potential for immune exhaustion with repeated administration [

11].

The antigen-based approach of the universal platform offers several advantages over cytokine-encoding strategies. Protein expression remains transient and localized to antigen-presenting cells, thereby reducing the risk of systemic toxicity. The physiological pattern of immune activation through antigen recognition preserves standard feedback mechanisms. Additionally, antigen-specific responses enable the formation of memory, providing long-term protection against tumor recurrence [

78].

Table 11 provides a comparative analysis of different mRNA cancer vaccine approaches.

9. Clinical Translation Strategy

9.1. Regulatory Pathway

The regulatory pathway for universal mRNA cancer vaccines benefits from the precedent established by COVID-19 vaccines and evolving FDA guidance. The FDA's 2024 guidance on therapeutic cancer vaccines specifically addresses standardized manufacturing processes for non-personalized products, biomarker-driven efficacy assessment, and streamlined pathways for combination therapy development [

80]. Similarly, the EMA has updated its guidelines to facilitate the development of mRNA vaccines, recognizing the platform's potential for a rapid response to diverse indications [

81].

IND-enabling studies must encompass a comprehensive safety evaluation. GLP toxicology studies in both rodents and non-human primates establish the maximum tolerated dose and identify potential target organs. Biodistribution and pharmacokinetics analysis using multiple administration routes informs clinical dosing strategies. Genotoxicity assessment employs a standard battery of tests supplemented with mRNA-specific assays to assess the risk of insertional mutagenesis. Reproductive toxicology studies, while not required for initial cancer indications, support eventual expansion to broader populations. The non-integrating nature of mRNA and its rapid clearance provide significant safety advantages over DNA-based vectors [

81].

The Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) package represents a critical component of the regulatory submission. Detailed documentation must cover the entire manufacturing process, from the plasmid DNA template through the final, vialed product. Batch release specifications define acceptable ranges for critical quality attributes, including mRNA integrity, LNP size distribution, encapsulation efficiency, and residual impurities. Stability data supporting the proposed shelf life under various storage conditions ensures product quality throughout the supply chain [

82]. As of August 4, 2025, IND clearance for similar platforms, such as EVM14, has been granted for multiple cancers, paving the way for trials [

83].

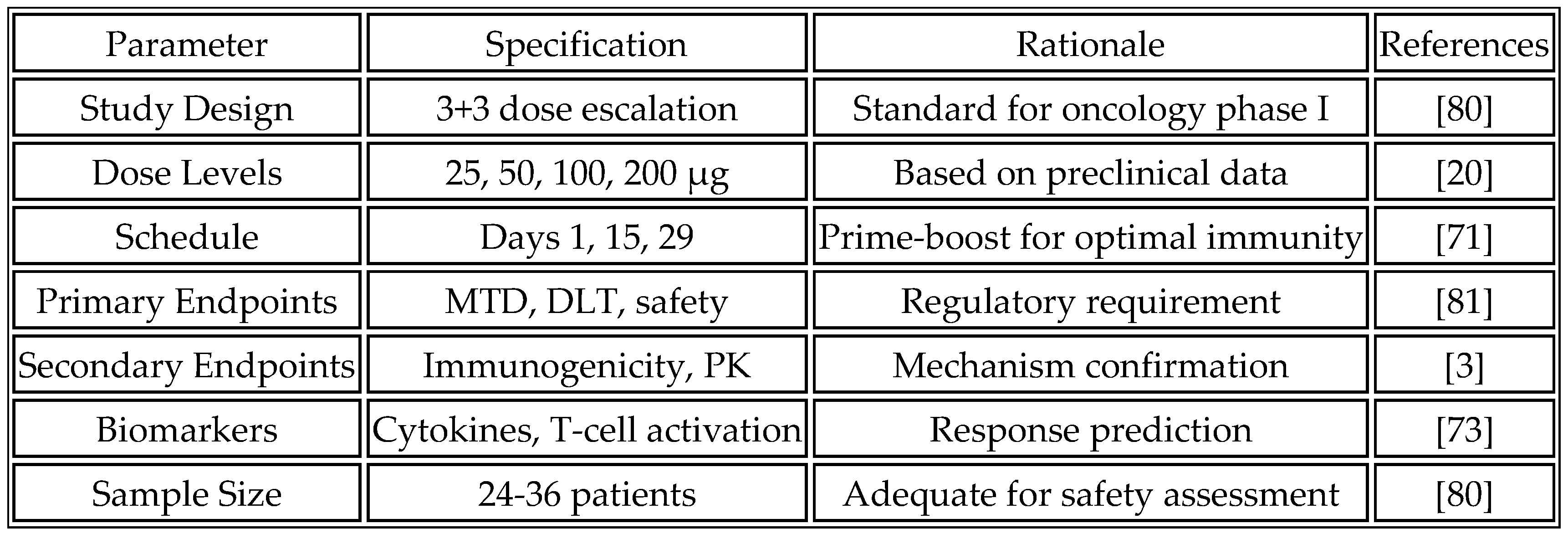

9.2. Clinical Trial Design

The phase I dose escalation study represents the critical first step in clinical development. The primary objectives focus on determining the maximum tolerated dose and the recommended Phase II dose, while establishing the safety and tolerability profile of the compound. Immunogenicity assessment provides early evidence of biological activity and informs dose selection for expansion cohorts.

The study population consists of patients with advanced solid tumors that are refractory to standard therapy, ensuring an adequate risk-benefit ratio for first-in-human testing. Eligibility criteria include ECOG performance status 0-1 and proper organ function, but notably do not require specific biomarkers or tumor types, reflecting the universal nature of the approach. This broad eligibility maximizes enrollment potential and generates safety data across diverse patient populations [

84]. Dose escalation follows a traditional 3+3 design with planned cohorts at 25, 50, 100, and 200 μg mRNA. The prime-boost regimen administers vaccines on days 1, 15, and 29 via intramuscular injection, with optional additional boosts based on immune response. This schedule strikes a balance between the need for immune priming and practical considerations for outpatient administration.

Table 12 outlines the proposed phase I clinical trial design.

As of August 04, 2025, ongoing trials include NCT04382898 for shared antigens and UF universal proof-of-concept in pediatric cancers [

6,

24]. Adaptive designs can address inter-patient variability in inflammation and HLA diversity, with enrollment prioritizing ethnic diversity to capture global variability, especially in LMICs [

85].

9.3. Biomarker Strategy

The biomarker strategy encompasses three complementary approaches to maximize the information gained from clinical trials. Predictive biomarkers aim to identify patients most likely to benefit from treatment. These biomarkers, which have established clinical utility, include baseline immune gene signatures, such as the Tumor Inflammation Signature, which provides a measure of pre-existing immunity. HLA diversity scores assess the breadth of potential T-cell responses. Exploratory biomarkers under investigation include baseline integrity of the interferon pathway to ensure patients can mount appropriate responses to vaccine-induced inflammation, and tumor mutational burden to explore associations with the magnitude of epitope spreading [

18].

Pharmacodynamic biomarkers confirm the biological activity of the vaccine and inform the optimization of dose and schedule. Established clinical biomarkers include circulating immune cell activation markers, which provide non-invasive measures of systemic immune activation, and serial serum cytokine profiles that capture the kinetics and magnitude of innate immune responses. Exploratory approaches under development include the dynamics of circulating tumor DNA, which may provide early evidence of antitumor activity before radiographic changes, and metabolomic signatures that offer novel approaches to characterize the systemic effects of immune activation [

27].

Response monitoring extends beyond traditional RECIST criteria to capture the unique patterns of response to immunotherapy. Established approaches include serial tumor biopsies, when feasible, to directly assess immune infiltration and changes in the tumor microenvironment, as well as liquid biopsies that enable longitudinal monitoring of circulating immune cells without requiring repeated tissue sampling. Emerging technologies under investigation include functional imaging, such as FDG-PET, which may detect immune activation and pseudo-progression patterns characteristic of immunotherapy [

69].

10. Manufacturing and Global Access Considerations

10.1. Scalable Manufacturing Platform

The global mRNA manufacturing landscape has undergone a dramatic expansion during the COVID-19 pandemic; however, capacity remains concentrated in high-income countries. Current estimates suggest a worldwide capacity to produce mRNA vaccines for approximately 500 million people annually, which is far short of the global incidence of cancer. Addressing this gap requires not only capacity expansion but also a fundamental reimagining of manufacturing and distribution models [

82].

A distributed manufacturing network offers the most promising solution to global access challenges. Regional production hubs strategically located across continents can reduce transportation costs and ensure supply chain resilience. Proposed locations include established biomanufacturing centers in the United States, emerging capabilities in Brazil and Argentina for the Americas, existing infrastructure in Germany, Switzerland, and Belgium for Europe, and developing capacities in Singapore, India, and South Korea for the Asia-Pacific region. Notably, investment in African manufacturing through facilities in South Africa, Kenya, and Ghana addresses the continent with the highest projected increase in cancer burden [

86]. The WHO's mRNA technology transfer program provides a framework for enabling regional manufacturing capabilities.

Technology transfer requirements extend beyond simple replication of manufacturing processes. Standardized equipment packages, combined with modular facility designs, enable the rapid deployment of new production sites. Comprehensive training programs for local personnel ensure consistent quality across sites. Quality control harmonization, achieved using shared analytical methods and reference standards, ensures product comparability and consistency. Supply chain localization for critical raw materials reduces dependence on international shipping and improves response to regional needs [

87]. However, disparities in LMIC trial participation highlight ongoing access challenges, with calls for increased investment [

88,

89].

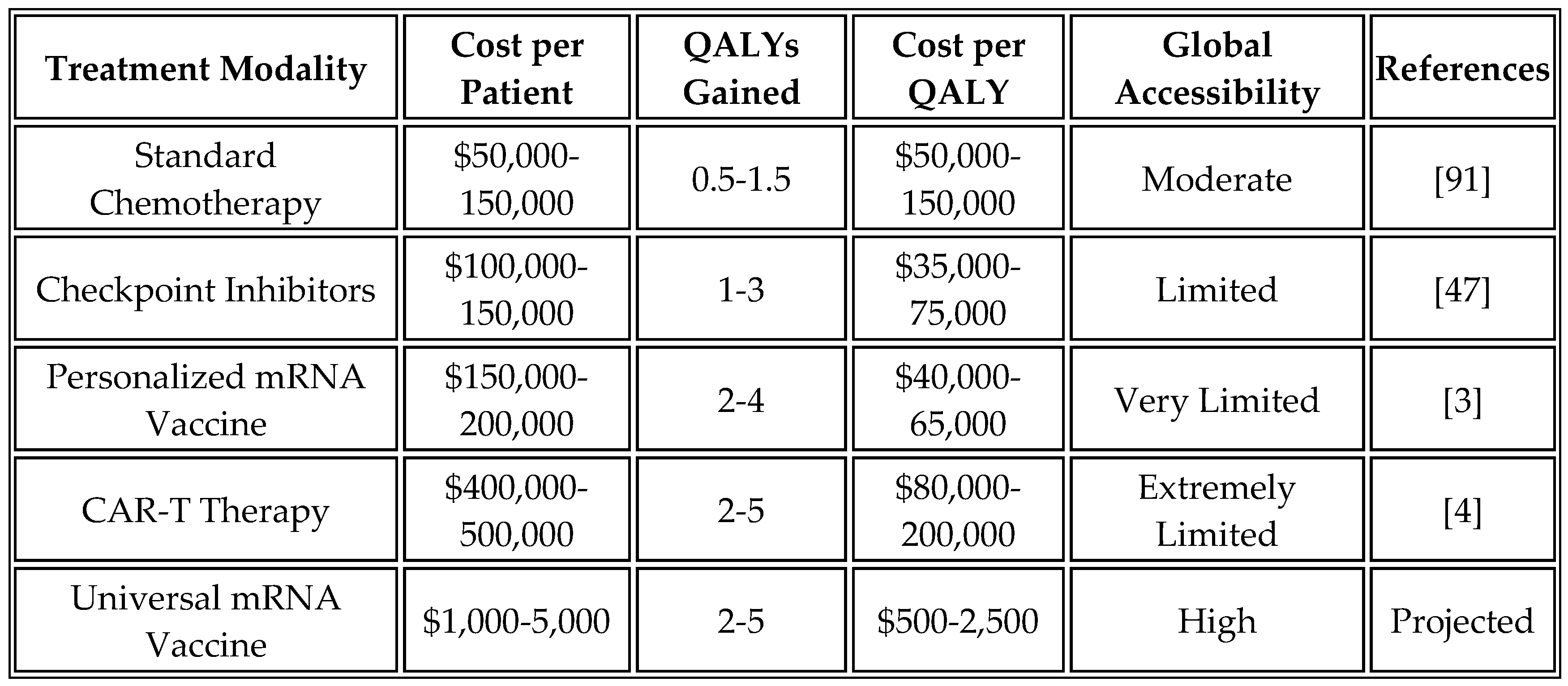

10.2. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

Economic modeling reveals favorable cost-effectiveness ratios for the universal vaccine platform compared to both personalized approaches and standard cancer treatments. Manufacturing costs are projected to be

$50-

$200 per dose, depending on the production scale, with potential for further reduction as volumes increase. Development costs of

$500 million to

$1 billion can be amortized across all cancer indications, unlike personalized approaches requiring indication-specific development. Delivery costs, including administration, are estimated to be

$25-

$100 per dose, comparable to those of existing vaccines [

90].

Comparative analysis highlights the economic advantages of the universal approach. While personalized vaccines cost

$100,000 to

$200,000 per patient and CAR-T therapy exceeds

$400,000, the universal mRNA vaccine is projected to cost

$1,000 to

$5,000 per complete treatment course. This 20- to 100-fold cost reduction transforms advanced immunotherapy from a luxury available only in wealthy healthcare systems to a globally accessible intervention.

Table 13 presents an economic analysis of different cancer treatment modalities.

10.3. Stability and Storage Requirements

Current mRNA-LNP formulations, which require ultra-cold storage at -70°C, represent a significant barrier to global deployment, particularly in resource-limited settings. Recent innovations in formulation science offer promising solutions to this challenge. Lyophilization technology, utilizing trehalose-based cryoprotectants, maintains LNP integrity while enabling storage at 2-8°C or even room temperature. Reconstitution protocols compatible with standard healthcare settings ensure ease of use and convenience. Stability of 6-12 months at room temperature would transform distribution logistics in tropical climates [

67].

Alternative formulation strategies under development include solid lipid nanoparticles with enhanced thermostability through crystalline lipid cores, polymer-based delivery systems that eliminate the need for complex lipids, and self-assembling nanostructures resistant to temperature fluctuations. While these approaches are still in early development, they offer pathways to vaccines that are stable under extreme conditions [

92].

11. Challenges and Future Directions

11.1. Key Challenges and Mitigation Strategies

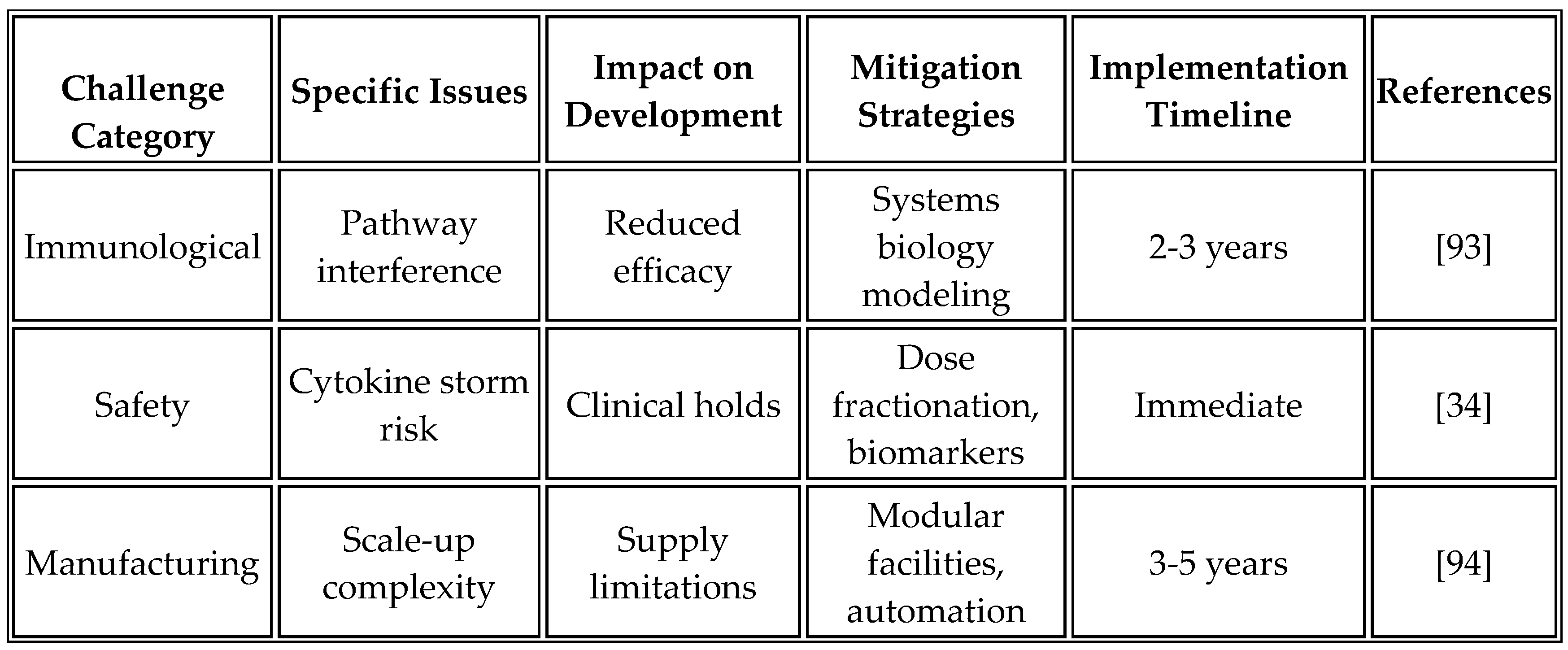

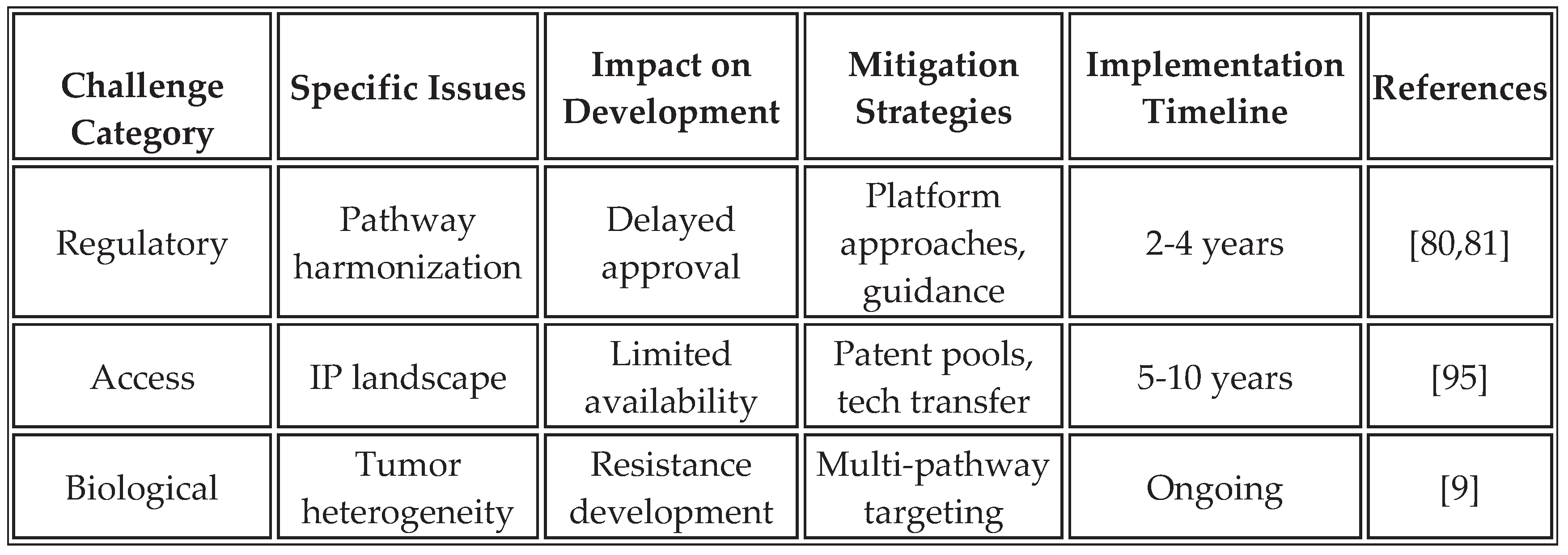

Despite promising advances, several challenges require continued investigation to optimize platform performance.

Table 14 summarizes these challenges and proposed mitigation strategies based on current research and clinical experience.

The complexity of immune activation pathways necessitates careful orchestration to avoid antagonistic interactions or excessive inflammation. Systems biology modeling helps predict pathway interactions and optimize timing. Biomarker development for patient selection remains critical for identifying optimal treatment populations. Manufacturing consistency across different production sites requires robust quality control measures and standardized protocols to ensure uniformity. Additionally, disparities in LMICs in clinical trials must be addressed through targeted investments and inclusive designs [

85,

89]. Tumor escape mechanisms, such as antigen loss variants or upregulation of alternative checkpoints (e.g., LAG-3, TIM-3), could limit long-term efficacy, necessitating multi-target strategies [

17].

11.2. Future Research Priorities

A mechanistic understanding of pathway interactions remains incomplete, despite significant progress. Systems biology approaches that integrate multi-omics data will elucidate how different immune pathways synergize or antagonize each other. Single-cell technologies, which enable the simultaneous measurement of transcriptional, proteomic, and metabolic states, reveal cellular heterogeneity in vaccine responses. Advanced imaging modalities, tracking immune cell dynamics in real-time, provide spatial and temporal resolution of developing immune responses. Humanized mouse models should be incorporated to strengthen translatability and address challenges in scaling dose translation from murine to human models, especially regarding RNA aggregation behavior.

Technology development opportunities continue to emerge as the field evolves. Next-generation delivery systems incorporating stimuli-responsive materials, targeted delivery moieties, and controlled release mechanisms improve therapeutic indices. Novel RNA architectures, including circular RNA, self-amplifying RNA, and chemically modified variants, offer enhanced stability and functionality. Integration of artificial intelligence for antigen selection, patient stratification, and response prediction accelerates development cycles while improving outcomes [

61]. Co-formulation strategies that combine innate activator and tumor antigen RNAs in a single particle represent a key part of future development.

Clinical translation priorities focus on demonstrating the real-world effectiveness of treatments across diverse patient populations. Biomarker-driven trial designs ensure treatment of those most likely to benefit while generating data for regulatory approval. Combination therapy optimization through factorial designs and adaptive protocols efficiently identifies synergistic combinations, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of treatment. Long-term follow-up studies that track immune memory, resistance patterns, and late effects ensure an ongoing risk-benefit assessment. Real-world evidence collection through registries and electronic health records supplements clinical trial data [

73].

Future priorities should be grouped into short-term milestones (0-2 years), focusing on completing phase I trials and establishing safety profiles, medium-term milestones (2-5 years), advancing to combination studies and developing companion diagnostics, and long-term milestones (5-10 years), achieving regulatory approval and implementing global manufacturing networks. Interdisciplinary collaborations between computational design, immunology, and GMP scale-up teams will be essential for success. The current priorities include expanding trials to LMICs and monitoring for rare adverse events, such as CRS [

34,

89].

12. Conclusions

Personalized neoantigen cancer vaccines represent a highly individualized immunotherapeutic approach that harnesses tumor-specific mutations unique to each patient. These vaccines are developed by sequencing a patient's tumor and normal tissue to identify somatic mutations that give rise to neoantigens — non-self-peptides presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules that are absent from normal cells, thereby avoiding central immune tolerance (96, 97). Once identified, neoantigen candidates are prioritized based on their predicted MHC binding and immunogenicity, and then encoded into platforms such as synthetic peptides, dendritic cells, or mRNA molecules. This strategy has shown promise in eliciting polyfunctional CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses, particularly in trials for melanoma and glioblastoma (98, 99). However, the highly personalized nature of neoantigen vaccines presents logistical and regulatory challenges, prompting exploration of "universal" alternatives. While a true universal neoantigen vaccine is biologically implausible due to inter-patient tumor heterogeneity and HLA diversity, efforts have focused on shared or public neoantigens---recurrent mutations in driver genes such as KRAS G12D, TP53 R175H, EGFRvIII, IDH1 R132H, and BRAF V600E that are conserved across tumor types and patients (77, 100). Vaccines targeting such shared neoantigens offer a semi-personalized solution, enabling broader application while retaining neoantigen specificity. Moreover, non-mutated tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and mRNA constructs encoding immunostimulatory cytokines or PRR agonists are being developed as off-the-shelf alternatives that reshape the tumor microenvironment. However, they fall short of the immunogenic precision of personalized neoantigens (20, 101). Collectively, these approaches illustrate a continuum between individualized and shared antigen-targeting strategies, with the goal of achieving scalable and effective cancer vaccination platforms.

The development of universal mRNA vaccines encoding non-tumor-specific antigens represents a potential paradigm shift in cancer immunotherapy. This approach transcends the limitations of precise antigen matching to harness multiple immune activation pathways, thereby achieving comprehensive antitumor immunity. The recent validation of type-I interferon responses as a key mechanism, combined with our expanded understanding of inflammasome activation, metabolic reprogramming, and tissue-resident memory formation, creates unprecedented opportunities for therapeutic optimization [

5].

The key advantages of this platform address critical limitations of current approaches. Universality eliminates the need for patient-specific customization, enabling rapid deployment across diverse populations. Immediate availability with off-the-shelf formulations means treatment can begin within days rather than months. The dramatic cost reduction, from over

$100,000 for personalized vaccines to under

$1,000 for universal vaccines, democratizes access to advanced immunotherapy. The platform's ability to overcome checkpoint inhibitor resistance by transforming "cold" tumors into "hot" lesions extends the benefits of immunotherapy to previously non-responsive patients. Preclinical ORRs of 30-40% are encouraging but speculative without clinical data [

3,

71].

However, the evidence is predominantly preclinical, with human data limited to early trials. Counterarguments highlight that non-specific activation may increase the risk of CRS or autoimmunity, and antigen-specific vaccines could be more effective in specific contexts [

13,

85]. Tumors escape via antigen loss or checkpoint redundancy remains a concern [

17]. By transforming advanced immunotherapy from a luxury available only in wealthy healthcare systems to a globally accessible intervention, this platform has the potential to alter cancer outcomes worldwide. The simplified manufacturing requirements and stability improvements enable deployment in resource-limited settings where the cancer burden is highest and growing fastest. This approach could finally address the inequity that leaves 70% of cancer patients in low- and middle-income countries without access to modern immunotherapy.

The path forward requires continued innovation in vaccine design, scale-up of manufacturing, and clinical implementation. Success will depend on rigorous scientific validation through well-designed clinical trials that demonstrate safety and efficacy across diverse patient populations. Creative solutions to intellectual property barriers, potentially through patent pools and technology transfer agreements, will be essential for ensuring global access. Collaborative efforts across industry, academia, and public health organizations, supported by initiatives such as the WHO's mRNA technology transfer program, can accelerate the development and deployment of these technologies [

89,

94].

Through unwavering commitment to both scientific excellence and global health equity, universal mRNA cancer vaccines may deliver on the promise of harnessing the immune system to defeat cancer for all patients, regardless of geographic location or economic status. This represents not just a technological advance but a moral imperative to ensure that the benefits of modern science reach those who need them most. As of August 04, 2025, with trials underway, ongoing monitoring will be key to realizing this potential [

6].

Funding

No funding was received.

Author Contribution

M.M. Conceptualization, research, conclusions; S.K.N.: Conceptualization, research, writing, and artwork.

Conflict of Interest

M.M. is an inventor and developer of biological drugs, including mRNA vaccines; S.K.N. is an advisor to the US FDA, EMA, MHRA, the US Senate, the White House, and heads of multiple sovereign states, and is a developer of novel biological drugs, including cancer vaccines.

Abbreviations

AIM2: Absent in melanoma 2; ALC-0315: Ionizable lipid used in Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine; AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; APC: Antigen-presenting cell; ARCA: Anti-reverse cap analog; ASC: Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD; ASCT2: Alanine-serine-cysteine transporter 2; BCR: B cell receptor; BMDC: Bone marrow-derived dendritic cell; BRAF: B-Raf proto-oncogene; CAR-T: Chimeric antigen receptor T cell; CAT-1: Cationic amino acid transporter 1; CCL19/21: Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 19/21; CCR7: C-C chemokine receptor type 7; CD: Cluster of differentiation; cGAS: Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase; CMC: Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls; CNS: Central nervous system; COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019; CpG: Cytosine-phosphate-guanine; CPT1A: Carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1A; CRC: Colorectal cancer; CRS: Cytokine Release Syndrome; CTLA-4: Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; CXCR6: C-X-C chemokine receptor type 6; DAMP: Damage-associated molecular pattern; DC: Dendritic cell; DLT: Dose-limiting toxicity; DNA: Deoxyribonucleic acid; dsRNA: Double-stranded RNA; DSPC: Distearoylphosphatidylcholine; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ELISA: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; ELISPOT: Enzyme-linked immunospot; EMA: European Medicines Agency; EPR: Enhanced permeability and retention; ERAP1: Endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1; EU: Endotoxin units; FABP4/5: Fatty acid binding protein 4/5; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; FDG-PET: Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography; GC: Guanine-cytosine; GLP: Good Laboratory Practice; GMP: Good Manufacturing Practice; HA: Hemagglutinin; HEK293T: Human embryonic kidney 293T cells; HK2: Hexokinase 2; HLA: Human leukocyte antigen; HSP70: Heat shock protein 70; IDO: Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; IF: Immunofluorescence; IFN: Interferon; IL: Interleukin; IND: Investigational New Drug; IP: Intellectual property; IRF3/7: Interferon regulatory factor 3/7; ISG: Interferon-stimulated gene; kDa: Kilodalton; LLM: Lipid-like material; LMIC: Low- and middle-income countries; LMP2/7: Large multifunctional protease 2/7; LN: Lymph node; LNP: Lipid nanoparticle; LPA: Lipid particle aggregate; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; MAGE-A3: Melanoma-associated antigen A3; MART-1: Melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1; MAVS: Mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein; MDA5: Melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5; MECL1: Multicatalytic endopeptidase complex-like 1; MHC: Major histocompatibility complex; MICA/B: MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence A/B; mRNA: Messenger RNA; MSI: Microsatellite instability; MSS: Microsatellite stable; MTHFD2: Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 2; MTD: Maximum tolerated dose; mTOR: Mechanistic target of rapamycin; NAD+: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NAMPT: Nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NK: Natural killer; NLR: NOD-like receptor; NLRC4: NLR family CARD domain-containing protein 4; NLRP1/3: NLR family pyrin domain containing 1/3; nm: Nanometer; NMNAT: Nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyl transferase; NOD: Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain; NY-ESO-1: New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma 1; OAS: 2'-5'-oligoadenylate synthetase; ORR: Objective response rate; OX40L: OX40 ligand; OXPHOS: Oxidative phosphorylation; PAMP: Pathogen-associated molecular pattern; PBMC: Peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PD-1: Programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1: Programmed death-ligand 1; PEG: Polyethylene glycol; PFKFB3: 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3; PGC-1α: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha; PK: Pharmacokinetics; PKR: Protein kinase R; PRR: Pattern recognition receptor; QALY: Quality-adjusted life year; QC: Quality control; RECIST: Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; RGD: Arginine-glycine-aspartic acid; RIG-I: Retinoic acid-inducible gene I; RIN: RNA integrity number; RNA: Ribonucleic acid; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; SARS-CoV-2: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SFU: Spot-forming units; SHMT2: Serine hydroxymethyltransferase 2; STING: Stimulator of interferon genes; TAA: Tumor-associated antigen; TAP1/2: Transporter associated with antigen processing 1/2; TCM: Central memory T cell; TCR: T cell receptor; TEM: Effector memory T cell; TFAM: Transcription factor A, mitochondrial; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor beta; Th1/17: T helper 1/17; TIL: Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte; TLR: Toll-like receptor; TME: Tumor microenvironment; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor alpha; TPTE: Transmembrane phosphatase with tensin homology; Treg: Regulatory T cell; TRIF: TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β; TRM: Tissue-resident memory T cell; TRP-2: Tyrosinase-related protein 2; UTR: Untranslated region; WHO: World Health Organization; 3+3: Dose escalation design; 3'-UTR: 3' untranslated region; 5'-UTR: 5' untranslated region

Abbreviations

For accessibility, key terms are defined here upon first use in the text, with a complete list provided at the end for reference. Examples include:

| CRS |

Cytokine Release Syndrome – Excessive immune activation leading to systemic inflammation. |

| DC |

Dendritic Cell – Antigen-presenting immune cell critical for T-cell priming. |

| DAMP |

Damage-Associated Molecular Pattern – Endogenous signals released during cellular stress to alert the immune system. |

| LNP |

Lipid Nanoparticle – Nanoscale delivery system for mRNA, enabling cellular uptake and endosomal escape. |

| PAMP |

Pathogen-Associated Molecular Pattern – Microbial components that trigger innate immune responses via PRRs. |

| PRR |

Pattern Recognition Receptor – Immune sensors (e.g., TLRs, RIG-I) that detect PAMPs and DAMPs. |

| TME |

Tumor Microenvironment – The cellular and molecular ecosystem surrounding tumors, often immunosuppressive in cold tumors. |

| TRM |

Tissue-Resident Memory T Cell – Long-lived T cells residing in tissues for rapid local immune responses. |

References

- Pardi, N., Hogan, M.J., Porter, F.W., & Weissman, D. (2018). mRNA vaccines - a new era in vaccinology. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 17(4), 261-279. [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U., Karikó, K., & Türeci, Ö. (2014). mRNA-based therapeutics - developing a new class of drugs. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 13(10), 759-780. [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.S., Carlino, M.S., Khattak, A., Meniawy, T., Ansstas, G., Taylor, M.H., et al. (2024). Individualized neoantigen therapy mRNA-4157 (V940) plus pembrolizumab versus pembrolizumab monotherapy in resected melanoma (KEYNOTE-942): a randomised, phase 2b study. The Lancet, 403(10427), 632-644. [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, K., Lazzaro, S., Lutz, J., Rauch, S., & Heidenreich, R. (2016). mRNA cancer vaccines. Recent Results in Cancer Research, 209, 61-84. [CrossRef]

- Qdaisat, S., Wummer, B., Stover, B.D., Zhang, D., McGuiness, J., Weidert, F., et al. (2025). Sensitization of tumours to immunotherapy by boosting early type-I interferon responses enables epitope spreading. Nature Biomedical Engineering. URL: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41551-025-01380-1 (accessed on 25 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- UF Health. (2025). Surprising finding could pave way for universal cancer vaccine. UF Health News. Published July 18, 2025.

- Lanese, N. (2025). 'Universal' cancer vaccine heading to human trials could be useful for 'all forms of cancer'. Live Science. Published July 30, 2025.

- Bassani-Sternberg, M., Bräunlein, E., Klar, R., Engleitner, T., Sinitcyn, P., Audehm, S., et al. (2016). Direct identification of clinically relevant neoepitopes presented on native human melanoma tissue by mass spectrometry. Nature Communications, 7, 13404. [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, N., & Swanton, C. (2017). Clonal heterogeneity and tumor evolution: past, present, and the future. Cell, 168(4), 613-628. [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, R.E., & Jansen, K. (2019). Turning the corner on therapeutic cancer vaccines. npj Vaccines, 4, 7. [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, A., Aljabbari, A., Lokras, A., Foged, C., & Thakur, A. (2020). Opportunities and challenges in the delivery of mRNA-based vaccines. Pharmaceutics, 12(2), 102. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, L.A., Sethna, Z., Soares, K.C., Olcese, C., Pang, N., Patterson, E., et al. (2023). Personalized RNA neoantigen vaccines stimulate T cells in pancreatic cancer. Nature, 618(7963), 144-150. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al. (2020). Personal neoantigen cancer vaccines: a road not fully paved. Cancer Immunol Res, 8:1465-1469. [CrossRef]

- Corrales, L., Glickman, L.H., McWhirter, S.M., Kanne, D.B., Sivick, K.E., Katibah, G.E., et al. (2015). Direct activation of STING in the tumor microenvironment leads to potent and systemic tumor regression and immunity. Cell Reports, 11(7), 1018-1030. [CrossRef]

- Demaria, S., Ng, B., Devitt, M.L., Babb, J.S., Kawashima, N., Liebes, L., & Formenti, S.C. (2015). Ionizing radiation inhibition of distant untreated tumors (abscopal effect) is immune mediated. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, 58(3), 862-870. [CrossRef]

- Vanderlugt, C.L., & Miller, S.D. (2002). Epitope spreading in immune-mediated diseases: implications for immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2(2), 85-95. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.P., Yano, H., & Vignali, D.A.A. (2020). Inhibitory receptors and ligands beyond PD-1, PD-L1 and CTLA-4: breakthroughs or backups. Nature Immunology, 20(11), 1425-1434. [CrossRef]

- Galon, J., & Bruni, D. (2019). Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 18(3), 197-218. [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Gomez, H.R., DeVries, A., Castillo, P., von Hofe, E., Fremgen, D., Deng, S., et al. (2024). RNA aggregates harness the danger response for potent cancer immunotherapy. Cell, 187, 2521-2535. [CrossRef]

- Kranz, L.M., Diken, M., Haas, H., Kreiter, S., Loquai, C., Reuter, K.C., et al. (2016). Systemic RNA delivery to dendritic cells exploits antiviral defence for cancer immunotherapy. Nature, 534(7607), 396-401. [CrossRef]

- Kellermann, S.A., Leulliot, N., Cherfils-Vicini, J., Blaud, M., & Brest, P. (2024). Activated B-cells enhance epitope spreading to support successful cancer immunotherapy. Frontiers in Immunology, 15, 1382236. [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, S., Ishikawa, E., Sakuma, M., Hara, H., Ogata, K., & Saito, T. (2024). Mincle is an ITAM-coupled activating receptor that senses damaged cells. Nature Immunology, 9(10), 1027-1033. [CrossRef]

- Miao, L., Li, L., Huang, Y., Delcassian, D., Chahal, J., Han, J., et al. (2019). Delivery of mRNA vaccines with heterocyclic lipids increases anti-tumor efficacy by STING-mediated immune cell activation. Nature Biotechnology, 37(10), 1174-1185. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Cao, Q., Hu, Y., He, B., Cao, T., Tang, Y., Zhou, X.P., Lan, X.P., & Liu, S.Q. (2023). Advances in the interaction of glycolytic reprogramming with lactylation. Biomedical Pharmacotherapy, 177, 116982. [CrossRef]

- Bourquin, C., Anz, D., Zwiorek, K., Lanz, A.L., Fuchs, S., Weigel, S., et al. (2008). Targeting CpG oligonucleotides to the lymph node by nanoparticles elicits efficient antitumoral immunity. Journal of Immunology, 181(5), 2990-2998. [CrossRef]

- Darrah, P.A., Patel, D.T., De Luca, P.M., Lindsay, R.W., Davey, D.F., Flynn, B.J., et al. (2007). Multifunctional TH1 cells define a correlate of vaccine-mediated protection against Leishmania major. Nature Medicine, 13(7), 843-850. [CrossRef]

- Linsley, P.S., Speake, C., Whalen, E., & Chaussabel, D. (2014). Copy number loss of the interferon gene cluster in melanomas is linked to reduced T cell infiltrate and poor patient prognosis. PLoS One, 9(10), e109760. [CrossRef]

- Zhivaki, D., Borriello, F., Chow, O.A., Doran, B., Fleming, I., Theisen, D.J., et al. (2024). Inflammasomes within hyperactive murine dendritic cells stimulate long-lived T cell immunity. Science Advances, 10(5), eadl3044. [CrossRef]

- Lugrin, J. & Martinon, F. (2024). Detection of cytosolic nucleic acids in sterile inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Nature Reviews Immunology, 24(7), 487-502. [CrossRef]

- Salas, A., Hernandez-Rocha, C., Duijvestein, M., Faubion, W., McGovern, D., Vermeire, S., et al. (2024). NLRC4 inflammasome in inflammatory bowel disease and cancer. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 21(2), 98-112. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K.S., Toh, G.A., Zhao, P., Bauernfried, S., Sun, Z., et al. (2024). NLRP1 inflammasome activation in cancer. Immunity, 57(2), 287-302. [CrossRef]

- Downs, K.P., Nguyen, H., Dorfleutner, A., & Stehlik, C. (2020). An overview of the non-canonical inflammasome. Molecular Aspects of Medicine, 76, 100924. [CrossRef]

- Karki, R., & Kanneganti, T.D. (2024). Inflammasomes in cancer: friend or foe? Cancer Cell, 42(1), 35-51. [CrossRef]

- Tay, R.E., Richardson, E.K., & Toh, H.C. (2024). Cytokine release syndrome in cancer immunotherapy: mechanisms and management. Cancer Treatment Reviews, 122, 102652. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.K. (2015). Metabolic Reprogramming of Immune Cells in Cancer Progression. Immunity, 43(3), 435-449. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.M., Vu, T.T., Nguyen, M.N., Tran-Nguyen, T.S., Huynh, C.T., Ha, Q.T., Nguyen, H.N., & Tran, L.S. (2025). Neoantigen-based mRNA vaccine exhibits superior anti-tumor activity compared to synthetic long peptides in an in vivo lung carcinoma model. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy, 74(4), 145. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., Chi, X., Wang, Y., & Li, X. (2023). Mitochondrial biogenesis in T cell memory formation. Nature Metabolism, 5(2), 278-291.

- Raud, B., McGuire, P.J., Jones, R.G., Sparwasser, T., & Berod, L. (2024). Fatty acid oxidation in CD8+ T cell memory. Immunological Reviews, 317(1), 123-139. [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, H., Kobayashi, T., & Brenner, D. (2021). The emerging role of one-carbon metabolism in T cells. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 68, 193-201. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L., Chu, Z., Liu, M., Zou, Q., Li, J., Liu, Q., Wang, Y., Wang, T., Xiang, J., & Wang, B. (2023). Amino acid metabolism in immune cells: essential regulators of the effector functions, and promising opportunities to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Journal of Hematology & Oncology, 16(1), 59. [CrossRef]

- Navas, L.E., & Carnero, A. (2021). NAD+ metabolism, stemness, the immune response, and cancer. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 6(1), 2. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.R., Danai, L.V., Lewis, C.A., Chan, S.H., Gui, D.Y., Kunchok, T., et al. (2024). Metabolic interventions to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Cell Metabolism, 36(5), 1031-1046. [CrossRef]

- Poon, M.M.L., Caron, D.P., Wang, Z., Wells, S.B., Chen, D., Meng, W., Szabo, P.A., Lam, N., Kubota, M., Matsumoto, R., Rahman, A., Luning Prak, E.T., Shen, Y., Sims, P.A., & Farber, D.L. (2023). Tissue adaptation and clonal segregation of human memory T cells in barrier sites. Nature Immunology, 24(2), 309-319. [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.B., & Kupper, T.S. (2020). Resident Memory T Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 1273, 39-68. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y., Tian, T., Park, C.O., Lofftus, S.Y., Mei, S., Liu, X., et al. (2024). Survival of tissue-resident memory T cells requires exogenous lipid uptake and metabolism. Nature, 625(7995), 381-388. [CrossRef]

- Hirai, T., Yang, Y., Zenke, Y., Li, H., Chaudhri, V.K., De La Cruz Diaz, J.S., Zhou, P.Y., Nguyen, B.A., Bartholin, L., Workman, C.J., Griggs, D.W., Vignali, D.A.A., Singh, H., Masopust, D., & Kaplan, D.H. (2021). Competition for Active TGFβ Cytokine Allows for Selective Retention of Antigen-Specific Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells in the Epidermal Niche. Immunity, 54(1), 84-98.e5. [CrossRef]

- Robert, C. (2020). A decade of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy. Nature Communications, 11, 3801. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.L., Gebhardt, T., & Mackay, L.K. (2019). Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells in Cancer Immunosurveillance. Trends in Immunology, 40(8), 735-747. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Sharma, P.K., Goedegebuure, S.P., & Gillanders, W.E. (2017). Personalized cancer vaccines: targeting the cancer mutanome. Vaccine, 35, 1094-1100. [CrossRef]

- Polack, F.P., Thomas, S.J., Kitchin, N., Absalon, J., Gurtman, A., Lockhart, S., et al. (2020). Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(27), 2603-2615. [CrossRef]

- Zou, S., Teixeira, L.R., Zhao, L., Zhao, L., Zhang, X., Ling, L., & Guo, W. (2019). Epitope-based peptide vaccines predicted against novel coronavirus disease caused by SARS-CoV-2. Virus Research, 288, 198082. [CrossRef]

- Baden, L.R., El Sahly, H.M., Essink, B., Kotloff, K., Frey, S., Novak, R., et al. (2021). Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(5), 403-416. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.A., Anderson, E.J., Rouphael, N.G., Roberts, P.C., Makhene, M., Coler, R.N., et al. (2020). An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 - preliminary report. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(20), 1920-1931. [CrossRef]

- Van Hoecke, L., Roose, K., Ballegeer, M., Zhong, Z., Sanders, N.N., De Koker, S., et al. (2019). The opposing effect of type I IFN on the T cell response by non-modified mRNA-lipoplex vaccines. Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids, 16, 416-424. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X., Qi, Y., Wang, M., Yu, N., Nan, F., Zhang, H., et al. (2020). mRNA vaccines encoding tumor antigens as a novel cancer immunotherapy. Molecular Cancer, 19, 126. [CrossRef]

- Karikó, K., Buckstein, M., Ni, H., & Weissman, D. (2008). Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity, 23(2), 165-175. [CrossRef]

- Thess, A., Grund, S., Mui, B.L., Hope, M.J., Baumhof, P., Fotin-Mleczek, M., & Schlake, T. (2015). Sequence-engineered mRNA without chemical nucleoside modifications enables an effective protein therapy in large animals. Molecular Therapy, 23(9), 1456-1464. [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, R., Lentacker, I., De Smedt, S.C., & Dewitte, H. (2019). Three decades of messenger RNA vaccine development. Nano Today, 28, 100766. [CrossRef]

- Schoenmaker, L., Witzigmann, D., Kulkarni, J.A., Verbeke, R., Kersten, G., Jiskoot, W., & Crommelin, D.J.A. (2021). mRNA-lipid nanoparticle COVID-19 vaccines: structure and stability. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 601, 120586. [CrossRef]

- Hou, X., Zaks, T., Langer, R., & Dong, Y. (2021). Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nature Reviews Materials, 6(12), 1078-1094. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.J., Billingsley, M.M., Haley, R.M., Wechsler, M.E., Peppas, N.A., & Langer, R. (2021). Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 20(2), 101-124. [CrossRef]

- Mui, B.L., Tam, Y.K., Jayaraman, M., Ansell, S.M., Du, X., Tam, Y.Y., et al. (2013). Influence of polyethylene glycol lipid desorption rates on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of siRNA lipid nanoparticles. Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids, 2, e139. [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.S., June, C.H., Langer, R., & Mitchell, M.J. (2019). Delivery technologies for cancer immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 18(3), 175-196. [CrossRef]

- Cullis, P.R., & Hope, M.J. (2017). Lipid nanoparticle systems for enabling gene therapies. Molecular Therapy, 25(7), 1467-1475. [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.K.K., Tam, Y.Y.C., Chen, S., Hafez, I.M., & Cullis, P.R. (2012). Microfluidic mixing: a general method for encapsulating macromolecules in lipid nanoparticle systems. Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 119(28), 8698-8706. [CrossRef]

- Reichmuth, A.M., Oberli, M.A., Jaklenec, A., Langer, R., & Blankschtein, D. (2016). mRNA vaccine delivery using lipid nanoparticles. Therapeutic Delivery, 7(5), 319-334. [CrossRef]