1. Introduction

Many fish farms use open systems, where water is taken from a natural pond and used in tanks before being returned to the main body of water. A large amount of water is consumed each day, and inorganic substances and organic nutrients are released, polluting the aquatic environment and affecting fish health status [

1,

2].

In recent years, photocatalyst has been widely studied in water treatment [

3], including in recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) for the off-flavours [

4] or ammonia removal [

5,

6,

7,

8] with positive effects on water quality, in terms of ammonia and nitrogen compounds concentrations and animal health.

The photocatalytic treatment offers great potential as an industrial technology for the detoxification or remediation of wastewater due to several factors: the process uses natural oxygen and light, possibly also sunlight, thus it is effective under ambient conditions.

The most largely employed photocatalyst, i.e., TiO

2, is low cost, readily available, non-toxic, chemically and mechanically stable, and has a high turnover; moreover the formation of large amounts of intermediate potentially toxic species is largely avoided; this technology allows the oxidation of organic molecules to CO

2 in a complete way: all these beneficial actions of TiO

2 thin films formation or growth on the internal walls of photoreactors are reported by [

9,

10].

The industrial research on TiO

2 photocatalysis is mainly aimed at using its oxidation properties, for sterilization, sanitation, and anti-pollution applications in the aqueous phase [

11]. Photocatalytic degradation of high ammonia concentration water solutions by TiO

2. Nowadays the photocatalytic destruction of organic matter is also exploited in photocatalytic antimicrobial coatings, typically thin films applied to furniture in hospitals and other surfaces susceptible to contamination with bacteria, fungi and viruses [

12].

The most commonly used photocatalyst, i.e. TiO

2, is inexpensive, readily available, non-toxic, chemically and mechanically stable [

13,

14]. Under UV irradiation reactive oxygen species, namely hydroxyl radicals (

•OH

−) and superoxide anions (

•O

2−), are produced on TiO

2 [

15]. In the case of viruses, these reactive radicals can degrade the capsid and envelope proteins and phospholipids of non-enveloped and enveloped viruses, respectively, leading to leakage and subsequent degradation of genetic information [

16,

17,

18,

19].

TiO

2 NPs are frequently used in paint, skin care, and cosmetic products, among other applications [

20]. Because of this broad use, TiO

2 NPs build up and release a lot of material into aquatic habitats [

21]. Many NPs have been used as treatments against viruses, and the advantages of their use is the specific target action and increase the efficiency of treatment with minimum side effects in species of aquaculture interest as reviewed by [

22]. For instance, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) inhibit hepatitis B virus (HBV) [

23], herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) [

24] and human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) [

25,

26] in vertebrate, as well as WSSV, Vibrio cholerae, V. harveyi, and V. parahaemolyticus infection in shrimp [

27,

28,

29,

30]. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) reduce the replication of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) in cloven-hoofed animals [

39] and V. parahaemolyticus as shrimp infection [

40]. Moreover, titanium dioxide can deactivate rotavirus, astrovirus, and feline calicivirus (FCV) [

40]. In aquaculture, numerous viral organisms affect a significant portion of global fish production, resulting in significant economic impacts on aquaculture [

42,

43,

44]. In particular, RNA viruses cause the most severe fish diseases, such as nervous necrosis virus, which is responsible for encephalopathy and retinopathy (VER) [

45]. Fish nodavirus is a non-enveloped icosahedral virion containing two positive-sense single-stranded genomic RNAs and is classified as a betanodavirus of the Nodaviridae.

In this study, the effect of TiO2, at different concentrations, was evaluated on Nodavirus in the dark and under UV irradiation, to determine TiO2 mechanisms of virus inactivating, of the cytopathic effect on fish cells, and immune system interaction of TiO2 NPs at different concentrations activated by UV irradiation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. TiO2 Powder Characterization

Commercial Aeroxide TiO

2 P25 powder was purchased from Evonik and used as received. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images for morphology investigation were acquired with a Zeiss ΣIGMA field emission instrument. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern for crystal phase determination was recorded on a Philips PW3020 powder diffractometer, using the Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54056 Å). The Rietveld refinement method was performed for quantitative phase analysis, using the “Quanto” software [

39]. The average crystallite size was calculated by means of the Scherrer equation applied to the main reflections centered at 2θ = 25.425° for anatase and 2θ = 27.575° for rutile. The BET specific surface area (SSA) and BJH mesopore volume and size were measured by N

2 adsorption/desorption at liquid nitrogen temperature (77 K) in a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 apparatus, after out-gassing the sample at 300°C in vacuum for 1 h. The diffuse reflectance (R) spectrum was measured on a Jasco V-670 spectrophotometer equipped with a PIN-757 integrating sphere, using barium sulfate as a reference, and then converted into a Taucplot, (KM hν)

1/2 vs. hν, where KM is the Kubelka-Munk transform of the reflectance R, with KM = (1−R)

2/2R, for bandgap energy determination.

2.2. Preparation of TiO2 Suspensions

The P25 powder was dispersed in aqueous suspensions as follows: a suspension containing 5 g/L of TiO2 was prepared first, which was diluted with distilled water, to obtain suspensions containing 2.5, 2.0, 1.25, 0.75, and 0.3 mg/mL of TiO2.

2.3. Cells and virus

The cell line (E-11) of Japanese striped fish (Ophiocephalus striatus) [

47] was maintained in L15 medium (Leibovitz L-15, Eurobio) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco) and 10% antibiotic (10,000 units/mL penicillin and 10,000 g/mL streptomycin, Gibco, Life Technologies). Betanodavirus isolate (PG105/D19) was obtained from clinically infected specimens of Dicentrarchus labrax from the isolate collection of the Virology Laboratory of the National Institute of Marine Sciences and Technologies (INSTM), Tunisia.

2.4. Investigation of TiO2 Cytotoxic Properties on the E-11 Cell Line

The MTT assay was performed to measure the cellular metabolic activity as an indicator of cell viability, proliferation and cytotoxicity. This colorimetric assay is based on the reduction of a yellow tetrazolium salt (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide or MTT) to purple formazan crystals by metabolically active cells. The viable cells contain NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductase enzymes that reduce MTT to formazan. The insoluble formazan crystals are dissolved with a solubilizing solution and the resulting-colored solution is analyzed by measuring the absorbance at 500-600 nm with a multiwall spectrophotometer. In this study, the protocol reported in ref. [

29] was adopted with a small change in the incubation temperature (25°C instead of 37°C). The absorbance was measured at 590 nm. The viability threshold (%) was calculated as follows: Viability threshold (%) = (absorbance of different TiO

2 suspensions / absorbance of the control) × 100.

2.5. TiO2 Inhibitory Properties on Nodaviruses Replication

An equal volume (50 µL) of Nodavirus solution and TiO2 suspension were mixed and used for the described treatments. Six TiO2 concentrations were tested (5.0, 2.5, 2.0, 1.25, 0.75 and 0.3 mg/mL). The UV irradiation was performed by exposing VNNV-TiO2 mix Eppendorf tubes, at a distance of 20 cm, to a UV-Clamp source (15 W) with a peak at 253.7 nm. The irradiated mixtures were retrieved at 5 different time intervals (5 min, 15 min, 30 min, 1 h and 16 h), then inoculated on E-11 cells. The mock and positive controls were always added.

A total volume of the irradiated mixtures (100 µL) was withdrawn at 5 different time intervals. Simultaneously, the same assay was performed in the dark by mixing an equal volume of Nodavirus and TiO2 (5 mg/mL) and incubating for 1h at 25°C prior to cell inoculation. The negative and positive controls were always added. Five 96-well plates with confluent E-11 cells (7x104 cells/well) were freshly prepared 24 h before the start of the experiment. Each plate corresponds to a sample interval. The assay was created in duplicate.

2.6. RNA Extraction and Real-Time qPCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cell supernatants using the GF-1 kit (VIVANTIS) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative reverse transcription qPCR was performed using Luna One-Step Universal Probe RT-qPCR kit and with gene-specific primers related to Nodavirus and various immune genes such as antiviral protein genes (IFN-I, Mx); pro-inflammatory genes (IL-1β, IL-8); anti-inflammatory gene (TNF-α, TGF-β); genes involved in the cellular response (CD4, CMH1-β); genes involved in the humoral response (IgM) and stress gene (Hsp30) (

Table 1). The reaction was processed in the 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The β -actin gene was selected as the housekeeping gene. The CT2 method was used to calculate relative gene expression [

30]. Validation of amplification efficiency was performed for each gene to use the amplification protocols in the current study.

3. Results

3.1. TiO2 Powder Characterization

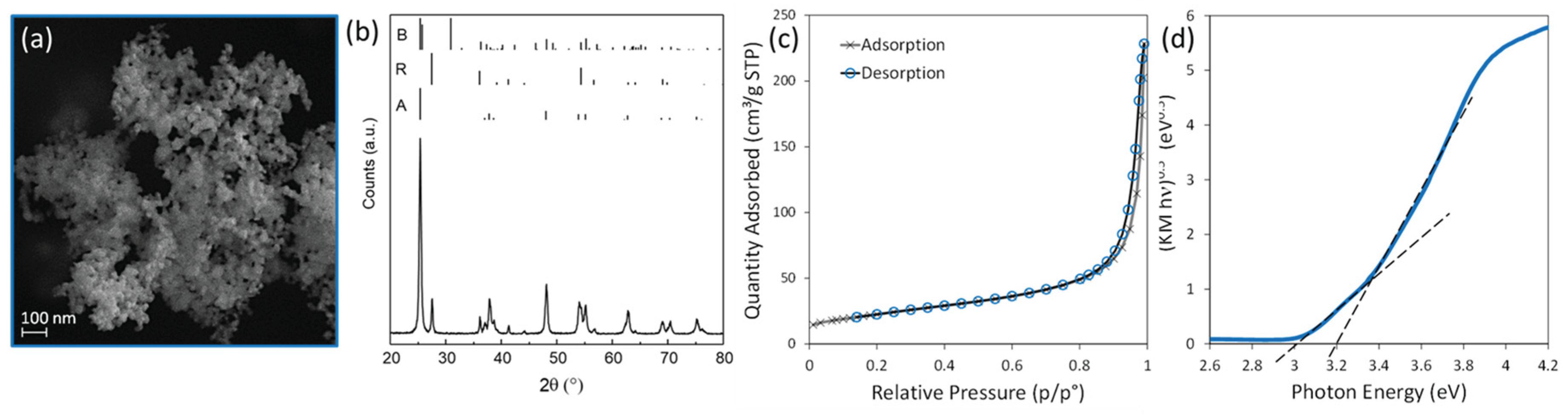

SEM micrograph (Figure1-A) reveals that commercial P25 TiO

2 consists of micro-aggregates of irregularly shaped, ca.10 to 50 nm sized NPs. According to the Rietveld refinement of the XRD pattern (

Figure 1-B), the sample is composed of 82% anatase and 18% rutile with no trace of brookite. The Scherrer average crystallite size is 21 nm for anatase and 26 nm for rutile. The N

2 adsorption/desorption isotherm at 77 K (

Figure 1-C) shows a relative narrow H1-type hysteresis loop typical of mesoporous materials with a BJH desorption cumulative volume of pores of 0.357 cm³/g and average pore width of 170 Å.

The measured BET specific surface area (SSA

BET) is 48 m

2/g. If a spherical shape of the particles were assumed, the average particle diameter D

m can be calculated from the SSA, as:

with SSA

BET in m

2/g, ρ

TiO2, the TiO

2 density, in g/cm

3 and D

m in nm. If ρ

TiO2 = 4 g/cm

3 is used (the mean value between the density of anatase and rutile), then D

m = 30 nm, in line with the SEM micrograph and the Scherrer average crystallite size. Finally, the Tauc plot of the diffuse reflectance spectrum (

Figure 1-D) clearly shows the presence of two slops. The extrapolation of these two linear regions to the abscissa yields an energy of the optical bandgap of 3 eV, characteristic of the rutile phase, and of 3.2 eV, typical of the anatase phase.

3.2. Investigation of TiO2 Cytotoxic Properties on the E-11 Cell Line

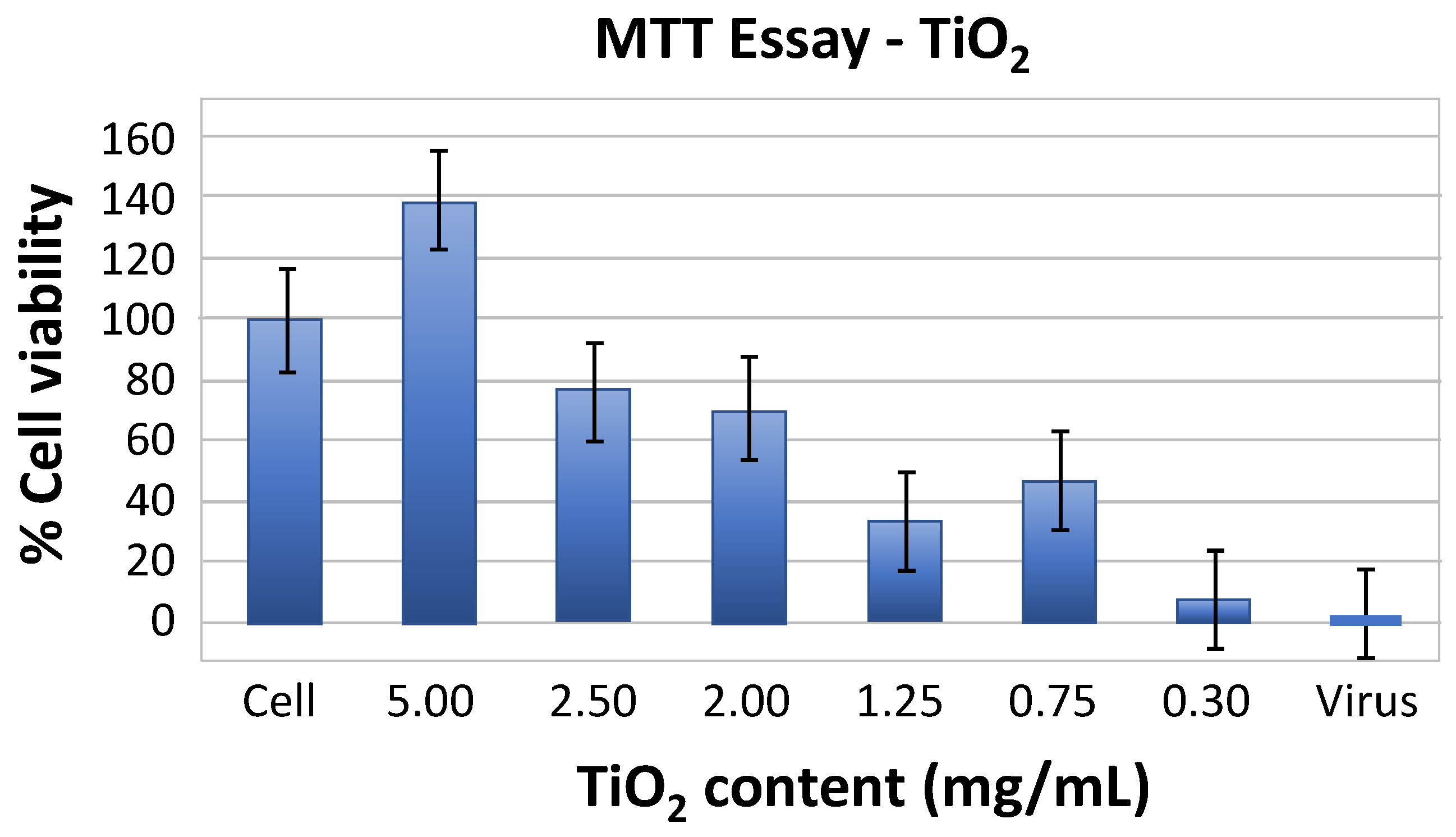

Based on the MTT measurements, the wells treated with TiO

2 (5 mg/mL) showed a higher viability threshold compared to those treated with the other TiO

2 concentrations (

Figure 2). In fact, TiO

2 concentrations ranging from 2.5 to 0.3 mg/mL significantly reduced the viability of E-11 cells.

3.3. In Vitro Investigation of the Inhibitory Properties of TiO2 on Nodavirus Replication

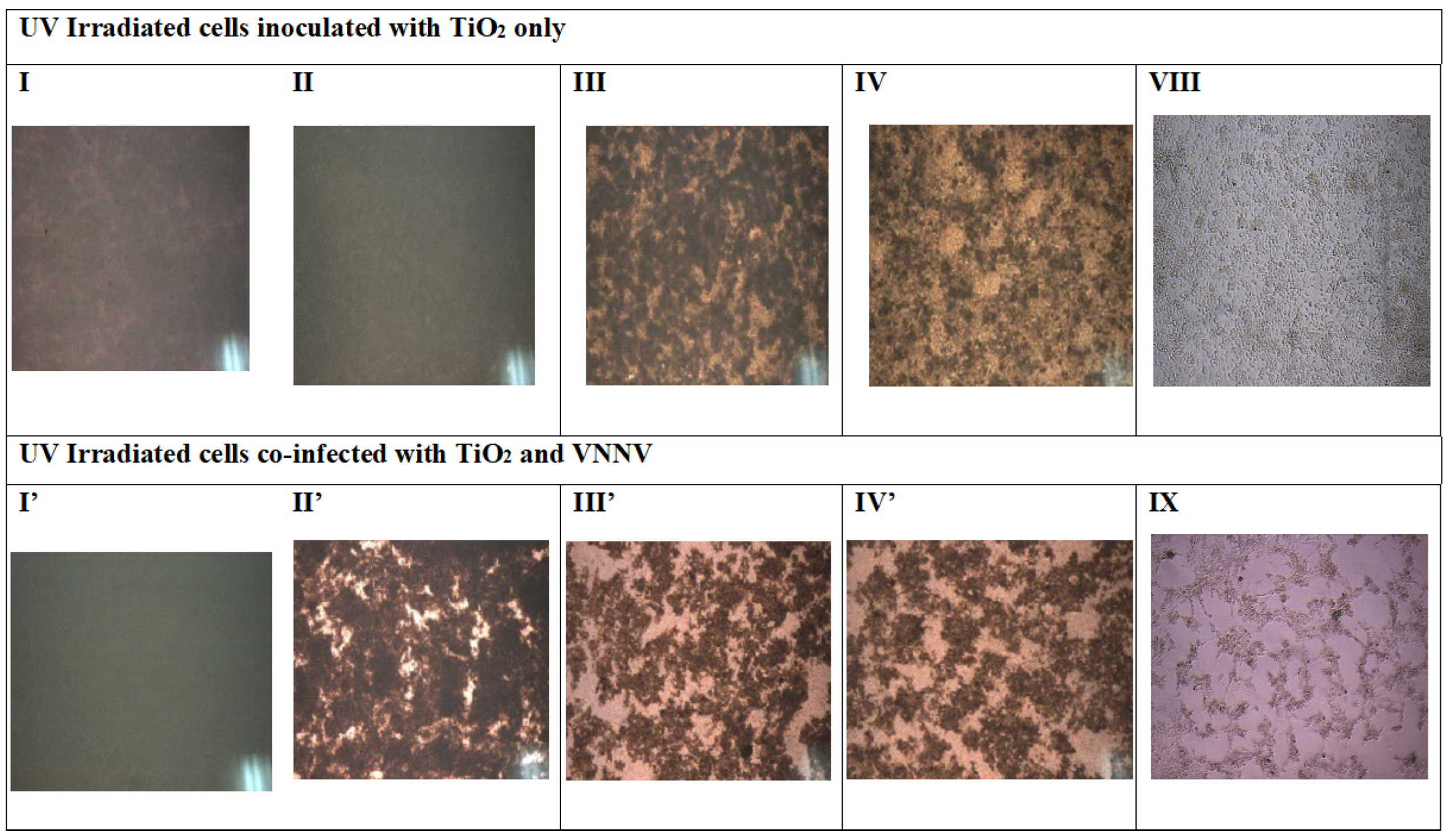

Daily observations were performed to check the cellular cytopathic effect (CPE) after different treatment conditions (see

Figure 3).

In general, the cell supernatants were very turbid and morphological changes were not visible under the reversed-phase microscope. Therefore, the wells content, which were already irradiated by UV at different time points after UV irradiation (5 min, 15 min, 30 min, 1 h and 16 h), regardless of the occurrence of CPE. It is worth noting that treatment of cells with a TiO2-nodavirus mixture incubated in the dark (i.e., not-irradiated) did not significantly inhibit Nodavirus replication on E-11. This result highlights the synergistic effect of combined UV-irradiation and TiO2 NPs inoculation. Continuous CPE was observed daily. The results obtained in darkness were then omitted in the rest of this study.

3.4. Relative Expression of the Viral Capsid Gene (CP) in E-11 Cells

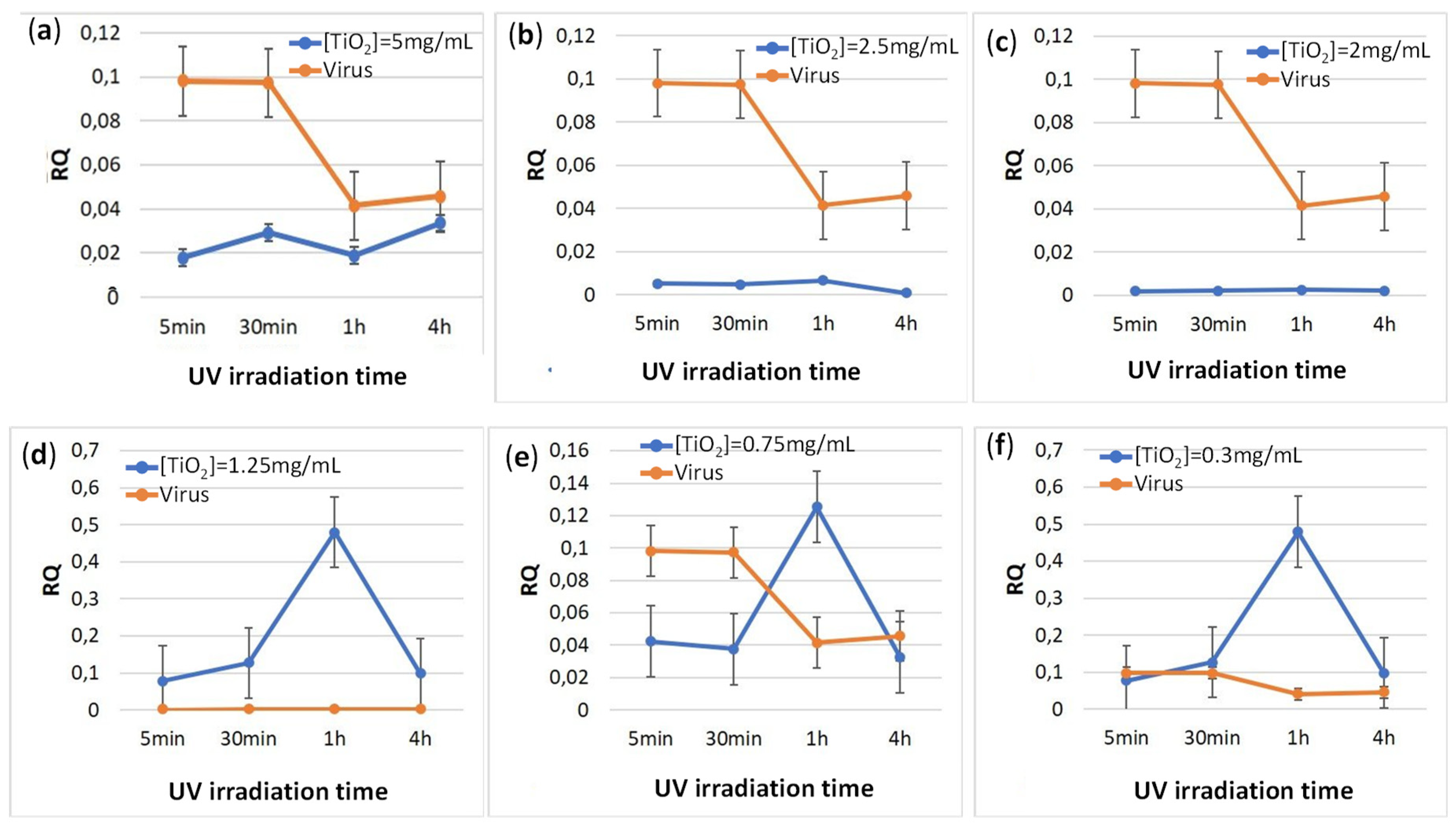

E-11 cells were inoculated with several UV-irradiated TiO

2-Nodavirus mixtures. No clear dose-dependent inhibitory effect was obtained. However, a significant decrease in viral CP gene expression was observed when TiO

2 solution was used at concentrations of 2.5 mg/mL and 1.25 mg/mL (

Figure 4). Interestingly, the inhibition of viral gene expression lasted up to 16 h after infection.

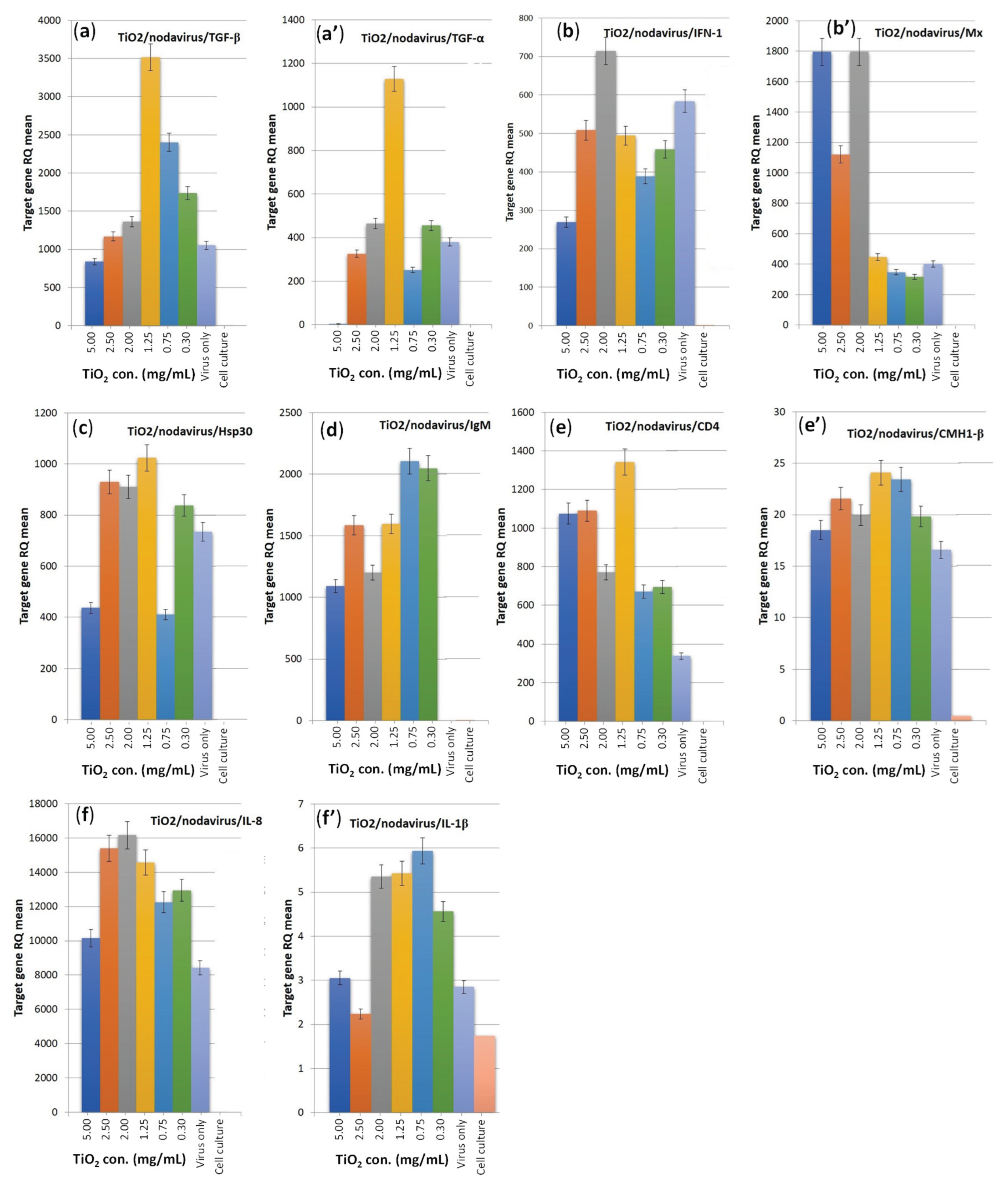

3.5. Immune Genes Expression

Immunogenes from E-11 fish cells exposed to TiO

2 co-incubated with Nodavirus showed dose-dependent up-regulation at 1 h. Cells exposed to 1.25 mg/mL of TiO

2 showed the highest level with increased expression of TGF-α, TGF-β and Hsp30 genes compared to virus control. In addition, there was an increase in the expression of IFN-1, Mx, Hsp30, Il-1β, CD4 and Il-8 genes for cells exposed to 2.0 and 2.5 mg/mL TiO

2 concentrations. With a TiO

2 concentration range of 2.0 to 0.3g/L MHC1-β gene expression increased, while cells exposed to low TiO

2 concentrations (0.75 and 0.3 mg/mL) showed an increase in IgM gene expression (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

Numerous viral organisms affect a significant portion of global fish production [

48,

49], resulting in significant economic impacts on aquaculture [

50]. In particular, RNA viruses cause the most serious fish diseases [

40] like the neural necrosis virus: betanodavirus responsible for encephalopathy and retinopath [

41]. The current study is an in vitro evaluation of the application of TiO

2 powders as an antiviral treatment in aquaculture. TiO

2 powder characterization

A comparative study of the effect of TiO

2 at different concentrations on Nodavirus in the dark and under UV irradiation was performed to determine the mechanisms of the inactivating effect of TiO

2. The investigation of the cytopathic effect was also carried out. The MTT assay shows that the cell viability decreases after addition of TiO

2 at different concentrations, especially in the 2.5-0.3 mg/mL range. These results are consistent with those of previous studies [

42], showing a significant reduction in cell viability upon co-exposure of the BF2 fish cell line to TiO

2 at 2.5 and 1.25 g/L. Despite the fact that the MTT assay either overestimates the cell viability or fails to detect a reduction in cell number and viability [

44], this effect is most likely produced by the superoxide anions (

•O

2−) generated by TiO

2 NPs [

40].

No clear cytopathic effect was observed under the reversed-phase microscope at different TiO

2 concentrations. Consistent with present results, a comparative analysis between TiO

2 NPs and ZnO NPs has shown that TiO

2 NPs are less cytotoxic than ZnO NPs [

38], meaning that TiO

2 NPs are safer than ZnO NPs with lower cytotoxicity. Another study showed that TiO

2 NPs, when coated with glycated polyethylene, exhibit stronger antiviral activity and lower cytotoxicity compared to bare TiO

2 NPs [

41].

To further investigate the antiviral activity of TiO

2, the relative expression of the viral capsid gene (CP) in E-11 cells was examined. The results showed a significant decrease in viral CP gene expression using a TiO

2 suspension at a concentration of 2.5 g/L or 1.25 g/L (

Figure 4). This result is in line with those reported by others [

47], who showed that the UV-activated TiO

2 surface is able to degrade the capsid and envelope proteins as well as the phospholipids of the non-enveloped virus. Consistent with the present results, previous studies have shown that an astrovirus, a non-enveloped virus that causes diarrheal diseases, was inactivated, but in this case the TiO

2 had been irradiated with visible light [

40].

Consistent results were obtained in previous studies on the impact of the use of different NPs on the immune system. Studies on Mytilus galloprovincialis showed that such particles induce pro-apoptotic processes. Their uptake by hemocytes was rapid and affected the phagocytic function [

52,

53,

54]. Similarly, studies of earthworms exposed to TiO

2 revealed bioaccumulation and significantly reduced phagocytosis from 0.1 mg/mL of TiO

2 NPs. However, TiO

2 did not cause cytotoxicity on coelomocytes [

52].

In the present study, co-incubation of Nodavirus with different concentrations of TiO

2 exposed to UV light for 1 h differentially regulated the relative expression of genes associated with immunity and stress in cells, such as antiviral protein genes (IFN-I, Mx); pro-inflammatory genes (IL-1, IL-8), anti-inflammatory gene (TGF-, TGF-), genes involved in the cellular response (CD4, CMH1-), gene involved in the humoral response (IgM) and stress gene (Hsp30). Remarkably, the TiO

2 concentration of 1.25 mg/mL increased expression of all target genes and induced an inflammatory response to Nodavirus, which has been never reported in the literature. Studies have now been conducted to examine the interaction of TiO

2 NPs with the immune system: human macrophages were exposed in vitro to non-toxic concentrations of various nanoparticles including TiO

2, which were shown [

53] to significantly affect the expression of several Toll-Like Receptors (TLR), molecules. These latter receptors represent a critical class involved in the initiation of the inflammatory response and innate immune responses. Particularly intriguing is that NPs like TiO

2 could increase the expression of TLR chains required for virus-dependent stimulation [

53]. TLR7 is another receptor that is crucial for detecting viruses. It binds to viral ssRNA and activates the signaling pathway that depends on IRF-3 to produce IFN-a/b [

54,

55]. According to [

53], macrophages exposed to nanoparticles such as TiO

2 have increased susceptibility to viral infections. Our in vitro research has shown that the different doses of TiO

2-NPs can possibly boost the fish's immune system to fight viral infections, although the doses are much higher compared to the estimated environmental concentration of 0.025 mg/mL [

55,

56].

Several research results suggest that nanoparticles can replace antibiotics in the treatment of infections. TiO2 NPs proved to be the safest of all NPs, cheap and easy to manufacture, compared to other NPs.

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

5. Conclusions

This in vitro study shows that TiO2 NPs reduce viral infection, while boosting the fish's innate immunity markers, and might be able to suppress more pathogens, but further experiments, such as in vivo tests, are required. In particular, further investigations should clarify whether the inactivation of TiO2 NPs depends on the virus titer, the incubation time and the TiO2 concentration. However, this work has shown that the use of TiO2 NPs to control Nodaviruses in fish farming has great potential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.C., A.C., A.D.C, and G.L.C.; methodology, N.C., A.C., A.D.C, and G.L.C.; investigation, R.E.J, N.C., and G.L.C.; resources, N.C., and G.L.C.; data curation, N.C., and G.L.C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.E.J, N.C., and G.L.C.; writing—review and editing, N.C., G.L.C., A.C., A.D.C, and E.S.; supervision, N.C. and G.L.C.; project administration, A.C.; funding acquisition, G.L.C., A.C., A.D.C, G.R., N.C., T.T and E.S.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the EU project PRIMA 2019 FishPhotoCAT.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request.

Ethical Statements

No animal experiments were performed during this study. Viral strains were isolated from fish specimens derived from the diagnostic and monitoring activities carried out at the National Institute of Sea Sciences and Technologies (INSTM) through its research project CapTunHealth (PEER Cycle 5), which was approved by the bioethics committee under the reference 2017/24/E/INSTM.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- F. Pascoli et al., “Evaluation of oxidative stress biomarkers in Zosterisessor ophiocephalus from the Venice Lagoon, Italy,” Aquatic Toxicology, vol. 101, no. 3–4, pp. 512–520, 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. L. Ahmad, J. Y. Chin, M. H. Z. Mohd Harun, and S. C. Low, “Environmental impacts and imperative technologies towards sustainable treatment of aquaculture wastewater: A review,” Journal of Water Process Engineering, vol. 46, p. 102553, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Ren et al., “Recent Advances of Photocatalytic Application in Water Treatment: A Review,” Nanomaterials, vol. 11, no. 7, p. 1804, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Zorzi, A. Bertini, A. Robertson, A. Berardinelli, L. Palmisano, and F. Parrino, “The application of advanced oxidation processes including photocatalysis-based ones for the off-flavours removal (GSM and MIB) in recirculating aquaculture systems,” Molecular Catalysis, vol. 551, p. 113616, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Livolsi et al., “Innovative photoelectrocatalytic water remediation system for ammonia abatement,” Catal Today, vol. 413–415, p. 113996, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Buoio et al., “From Photocatalysis to Photo-Electrocatalysis: An Innovative Water Remediation System for Sustainable Fish Farming,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 15, p. 9067, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Randazzo et al., “A novel photocatalytic purification system for fish culture,” Zebrafish, vol. 14, no. 5, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Altomare, G. L. Chiarello, A. Costa, M. Guarino, and E. Selli, “Photocatalytic abatement of ammonia in nitrogen-containing effluents,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 191, pp. 394–401, 2012. [CrossRef]

- G. L. Chiarello, A. Zuliani, D. Ceresoli, R. Martinazzo, and E. Selli, “Exploiting the Photonic Crystal Properties of TiO2 Nanotube Arrays to Enhance Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production,” ACS Catalysis, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 1345–1353, 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. L. Chiarello, C. Tealdi, P. Mustarelli, and E. Selli, “Fabrication of Pt/Ti/TiO2 photoelectrodes by RF-Magnetron sputtering for separate hydrogen and oxygen production,” Materials, vol. 9, no. 4, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Murgia, A. Poletti, and R. Selvaggi, “Photocatalytic degradation of high ammonia concentration water solutions by TiO2,” Annali di Chimica, vol. 95, no. 5, pp. 335–343, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wu et al., “Preparation of photocatalytic anatase nanowire films by in situ oxidation of titanium plate,” Nanotechnology, vol. 20, no. 18, 2009. [CrossRef]

- N. Moreira et al., “Fast mineralization and detoxification of amoxicillin and diclofenac by photocatalytic ozonation and application to an urban wastewater,” Water research, vol. 87, pp. 87–96, 2015.

- T. Do, D. Nguyen, K. Nguyen, P. L.- Materials, and U. 2019, “TiO2 and Au-TiO2 Nanomaterials for Rapid Photocatalytic Degradation of Antibiotic Residues in Aquaculture Wastewater,” mdpi.com, vol. 12, no. 15, 2019.

- R. C. Gilson, K. C. L. Black, D. D. Lane, and S. Achilefu, “Hybrid TiO2 -Ruthenium Nano-photosensitizer Synergistically Produces Reactive Oxygen Species in both Hypoxic and Normoxic Conditions ,” Angewandte Chemie, vol. 129, no. 36, pp. 10857–10860, 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Hajkova, P. Spatenka, Jan Horsky, I. Horska, A. Kolouch. “Photocatalytic Effect of TiO2 Films on Viruses and Bacteria,” Plasma Processes and Polymers, 4(S1), S397–S401, 2007. [CrossRef]

- N. A. Mazurkova, Y. E. Spitsyna, N. V. Shikina, Z. R. Ismagilov, S. N. Zagrebel’nyi, and E. I. Ryabchikova, “Interaction of titanium dioxide nanoparticles with influenza virus,” Nanotechnologies in Russia, vol. 5, no. 5–6, pp. 417–420, 2010. [CrossRef]

- P. Hajkova, P. Spatenka, J. Horsky, I. Horska, and A. Kolouch, “Photocatalytic effect of TiO2 films on viruses and bacteria,” Plasma Processes and Polymers, vol. 4, no. SUPPL.1, 2007. [CrossRef]

- N. Bono, F. Ponti, C. Punta, and G. Candiani, “Effect of UV Irradiation and TiO2-Photocatalysis on Airborne Bacteria and Viruses: An Overview,” Materials, vol. 14, no. 1075, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. M. A. Hussein et al., “Amelioration of titanium dioxide nanoparticle reprotoxicity by the antioxidants morin and rutin,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 26, no. 28, pp. 29074–29084, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Cheng et al., “Adverse reproductive performance in zebrafish with increased bioconcentration of microcystin-LR in the presence of titanium dioxide nanoparticles,” Environmental Science: Nano, no. 5, pp. 1208–1217, 2018.

- K. Khosravi-Katuli, E. Prato, G. Lofrano, M. Guida, G. Vale, and G. Libralato, “Effects of nanoparticles in species of aquaculture interest,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 24, no. 21, pp. 17326–17346, 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Lu, R. Sun, R. Chen, C. Hui, C.M. Ho, J.M. Luk, G.K. Lau, C.M. Che, “Silver nanoparticles inhibit hepatitis B virus replication,” Antivir Ther. 2008;13(2):253-62. [CrossRef]

- P. Orłowski, A. Kowalczyk, et al., “Antiviral activity of tannic acid modified silver nanoparticles: potential to activate immune response in herpes genitalis,” Viruses 2018, 10(10), 524. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Elechiguerra et al., “Interaction of silver nanoparticles with HIV-1,” Journal of Nanobiotechnology, vol. 3, 6, 2005. [CrossRef]

- R. W. Y. Sun, R. Chen, N. P. Y. Chung, C. M. Ho, C. L. S. Lin, and C. M. Che, “Silver nanoparticles fabricated in Hepes buffer exhibit cytoprotective activities toward HIV-1 infected cells,” Chemical Communications, no. 40, pp. 5059–5061, 2005. [CrossRef]

- K. Kandasamy, N. M. Alikunhi, G. Manickaswami, A. Nabikhan, and G. Ayyavu, “Synthesis of silver nanoparticles by coastal plant Prosopis chilensis (L.) and their efficacy in controlling vibriosis in shrimp Penaeus monodon,” Applied Nanoscience (Switzerland), vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 65–73, 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Ochoa-Meza et al., “Silver nanoparticles enhance survival of white spot syndrome virus infected Penaeus vannamei shrimps by activation of its immunological system,” Fish and Shellfish Immunology, vol. 84, pp. 1083–1089, 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Sivaramasamy and W. Zhiwei, “Enhancement of Vibriosis Resistance in Litopenaeus vannamei by Supplementation of Biomastered Silver Nanoparticles by Bacillus subtilis,” Journal of Nanomedicine & Nanotechnology, vol. 07, no. 01, 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. C. M. Márquez, A. H. Partida, M. del Carmen, M. Dosta, J. C. Mejía, and J. A. B. Martínez, “Silver nanoparticles applications (AgNPS) in aquaculture,” International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 5–11, 2018.

- V. Panzarin , A. Toffan , E. Vetrini et al. Development of a universal real-time RT-PCR assay targeting RNA2 of betanodaviruses, capable of detecting all genotypes of fish nodavirus. Journal of Virological Methods, 167(2), 110–118, 2010.

- G.K Purohit, S.K Nayak, B.K. Mishra . Evaluation of β-actin gene as a reference for RT-qPCR analysis in Puntius sophore under thermal stress. BMC Genomics, 18:617, 2017.

-

G. Scapigliati, F. Buonocore , G. Marino. Functional aspects of fish lymphocytes: markers, cytokines and gene expression. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 29(2), 229–236, 2010.

-

L. Poisa-Beiro, Q.K. Doan, M.C. Piazzon et al. Virus–host interaction in European sea bass: induction of Mx, IL-1β and TNF-α expression by betanodavirus. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 25(3), 462–470, 2008.

-

M.P. Sepulcre , V. Mulero , J.V. Planas . Interleukin-8 gene in sea bass: molecular cloning and expression pattern in response to infection. Developmental & Comparative Immunology, 31(1), 413–425, 2007.

-

T. Angsujinda , S. Auewarakul , S. Pongsiri. Tumor necrosis factor-α and heat shock protein expression in fish under stress conditions. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 103, 229–236, 2020.

- A. Santos, M.E. Marrero, M. Sánchez et al. Characterization of IgM heavy chain gene expression during fish development. Developmental & Comparative Immunology, 25(7), 549–556, 2001.

- S; Picchietti , G. Scapigliati , E. Randelli et al. Molecular cloning and expression of MHC class I-β gene in European sea bass. Developmental & Comparative Immunology, 48(2), 234–242, 2015.

- S. Rafiei, S. E. Rezatofighi, M. R. Ardakani, and S. Rastegarzadeh, “Gold Nanoparticles Impair Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus Replication,” IEEE Transactions on Nanobioscience, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 34–40, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Tello-Olea et al., “Gold nanoparticles (AuNP) exert immunostimulatory and protective effects in shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) against Vibrio parahaemolyticus,” Fish and Shellfish Immunology, vol. 84, pp. 756–767, 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Sang et al., “Photocatalytic inactivation of diarrheal viruses by visible-light-catalytic titanium dioxide,” Clinical Laboratory, vol. 53, no. 7–8, pp. 413–421, 2007.

- Kibenge frederick SB, “Emerging viruses in aquaculture,” Current Opinion in Virology, vol. 34, pp. 97–103, 2019.

- P. J. Walker and C. V. Mohan, “Viral disease emergence in shrimp aquaculture: origins, impact and the effectiveness of health management strategies,” Reviews in Aquaculture, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 125–154, Jun. 2009. [CrossRef]

- H. D. Rodger, “Fish disease causing economic impact in global aquaculture” Birkhauser Advances in Infectious Diseases, no. 9783034809788, pp. 1–34, 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. Cherif, H. Attia El Hili, N. Mzoughi, L. Chouba, M. El Bour, D. El-Amri, A. Hamza, K. Maatoug, S. Zaafrane, S. Hammami, (2011): “Tunisian aquaculture: present situation and potentialities” in: Gavin L. Andrews and Lauren A. Vexton (Eds), ”Fish Farms: Management, Disease Control and the Environment”. Nova Science Publishers N.Y., USA. Editors:, Chapter 4, pp.113-132. ISBN: 978-1-61209-538-7.

- A. Altomare et al., “Applied Crystallography Quanto: a Rietveld program for quantitative phase analysis of polycrystalline mixtures,” J. Appl. Cryst, vol. 34, 392-397, 2001. [CrossRef]

- T. Iwamoto, T. Nakai, K. Mori, M. Arimoto, and I. Furusawa, “Cloning of the fish cell line SSN-1 for piscine nodaviruses,” vol. 43, no. 1997, pp. 81–89, 2000.

- C. A. Suttle, “Marine viruses - Major players in the global ecosystem,” Nature Reviews Microbiology, vol. 5, no. 10, pp. 801–812, 2007. [CrossRef]

- H. Su and J. Su, “Cyprinid viral diseases and vaccine development,” Fish and Shellfish Immunology, vol. 83, pp. 84–95, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.M.; Sharma, B.; Talukder, S.; Uddin, M.J.; Siddik, M.A.B.; Sarker, S. Viral Threats to Australian Fish and Prawns: Economic Impacts and Biosecurity Solutions—A Systematic Review. Viruses 2025, 17, 692. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang, H. Yu, and J. K. Wickliffe, “Limitation of the MTT and XTT assays for measuring cell viability due to superoxide formation induced by nano-scale TiO2,” Toxicology in Vitro, vol. 25, no. 8, pp. 2147–2151, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. Canesi, C. Ciacci, R. Fabbri, A. Marcomini, G. Pojana, and G. Gallo, “Bivalve molluscs as a unique target group for nanoparticle toxicity,” Marine Environmental Research, vol. 76, pp. 16–21, 2012.

- C. Ciacci et al., “Immunomodulation by different types of N-oxides in the hemocytes of the marine bivalve Mytilus galloprovincialis,” PLoS ONE, vol. 7, no. 5, May 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. Barmo, C. Ciacci, B. Canonico, R. Fabbri, K. C.-A. Toxicology, and U. 2013, “In vivo effects of n-TiO2 on digestive gland and immune function of the marine bivalve Mytilus galloprovincialis,” Elsevier, 20AD.

- B. N. Mueller NC, “Exposure modeling of engineered nanoparticles in the environment,” ACS Publications, vol. 42, no. 12, pp. 4447–4453, Jun. 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Pérez and D. B. M la Farré, “Analysis, behavior and ecotoxicity of carbon-based nanomaterials in the aquatic environment,” Elsevier, 1990.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).