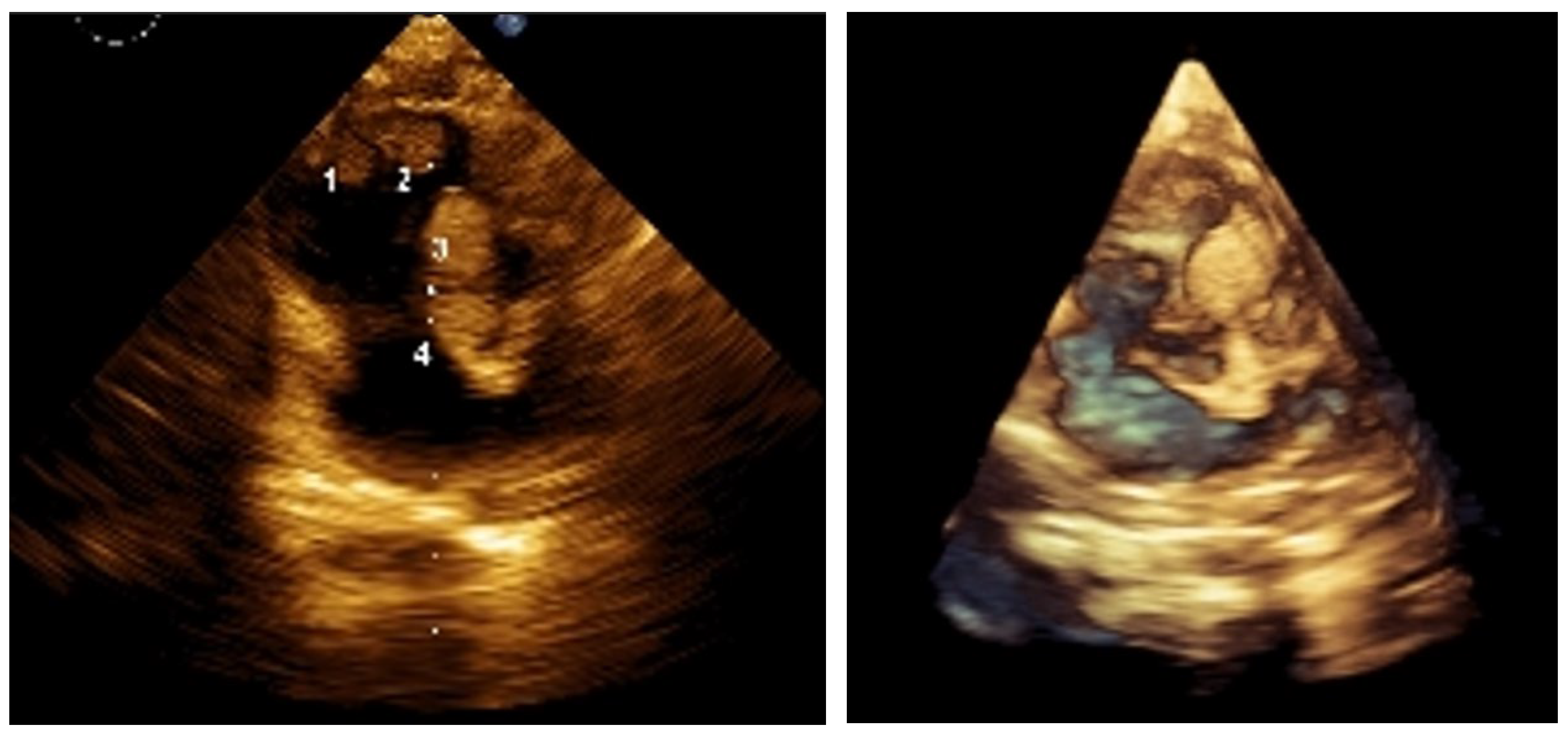

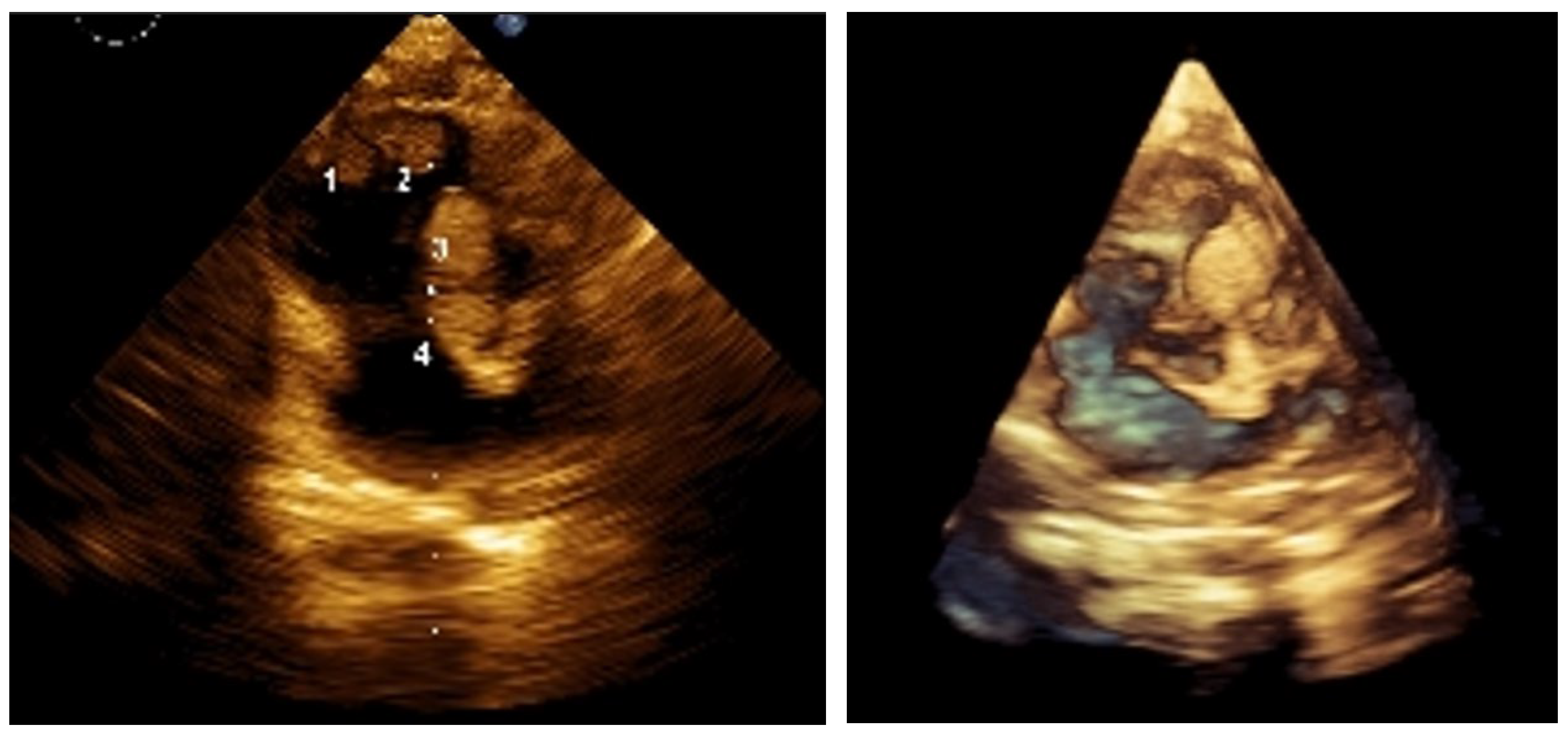

Figure 1.

2D and 3D images of the lesions before treatment. Reports suggest approximately 60% of children with TSC present with cardiac rhabdomyomas (CRs). These tumors can undergo spontaneous regression, although the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. Partial regression of CRs has been reported in about 50% of cases, and with complete resolution in approximately 18% [

1]. CRs can lead to serious cardiac complications, typically observed during fetal life or the early neonatal period. Such complications may result from obstruction of intracavitary spaces and/or cardiac valves, involvement of the conduction system causing atrioventricular block, or the formation of a substrate for atrial or ventricular tachycardia. These issues can lead to low cardiac output syndrome, congestive heart failure, and even sudden cardiac death. Mortality from cardiac complications is estimated at around 9.5% [

1]. In most cases, treatment is not required as the lesions regress spontaneously. However, patients with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction or refractory arrhythmias may require surgical resection. Prognosis depends on the number, size, and location of lesions, as well as the presence of associated anomalies. Overall, despite the potential for regression, cardiac manifestations present a clinical problem in about one-third of cases. A multidisciplinary team—including a clinical geneticist, pediatric cardiologist, neonatologist, and pediatric oncologist specializing in solid tumors—managed the case of a 1-month-old premature infant diagnosed with TSC according to international criteria. The infant was born at 35 weeks’ gestation, weighing 1980 g and measuring 44 cm, and was one of four siblings; the mother had experienced three spontaneous abortions. The neonatal period was complicated by infection and respiratory failure. Diagnosis occurred at 1 month due to a detected heart murmur. Echocardiography revealed cardiac rhabdomyomatosis (

Figure 1), prompting clinical and genetic evaluation. A

TSC2 gene (chromosome 16p13.3) mutation was identified—“

c.976-15G>A”, and imaging (Gd-enhanced MRI and transcranial ultrasound) confirmed multiple SEGAs and CRs.

Figure 1.

2D and 3D images of the lesions before treatment. Reports suggest approximately 60% of children with TSC present with cardiac rhabdomyomas (CRs). These tumors can undergo spontaneous regression, although the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. Partial regression of CRs has been reported in about 50% of cases, and with complete resolution in approximately 18% [

1]. CRs can lead to serious cardiac complications, typically observed during fetal life or the early neonatal period. Such complications may result from obstruction of intracavitary spaces and/or cardiac valves, involvement of the conduction system causing atrioventricular block, or the formation of a substrate for atrial or ventricular tachycardia. These issues can lead to low cardiac output syndrome, congestive heart failure, and even sudden cardiac death. Mortality from cardiac complications is estimated at around 9.5% [

1]. In most cases, treatment is not required as the lesions regress spontaneously. However, patients with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction or refractory arrhythmias may require surgical resection. Prognosis depends on the number, size, and location of lesions, as well as the presence of associated anomalies. Overall, despite the potential for regression, cardiac manifestations present a clinical problem in about one-third of cases. A multidisciplinary team—including a clinical geneticist, pediatric cardiologist, neonatologist, and pediatric oncologist specializing in solid tumors—managed the case of a 1-month-old premature infant diagnosed with TSC according to international criteria. The infant was born at 35 weeks’ gestation, weighing 1980 g and measuring 44 cm, and was one of four siblings; the mother had experienced three spontaneous abortions. The neonatal period was complicated by infection and respiratory failure. Diagnosis occurred at 1 month due to a detected heart murmur. Echocardiography revealed cardiac rhabdomyomatosis (

Figure 1), prompting clinical and genetic evaluation. A

TSC2 gene (chromosome 16p13.3) mutation was identified—“

c.976-15G>A”, and imaging (Gd-enhanced MRI and transcranial ultrasound) confirmed multiple SEGAs and CRs.

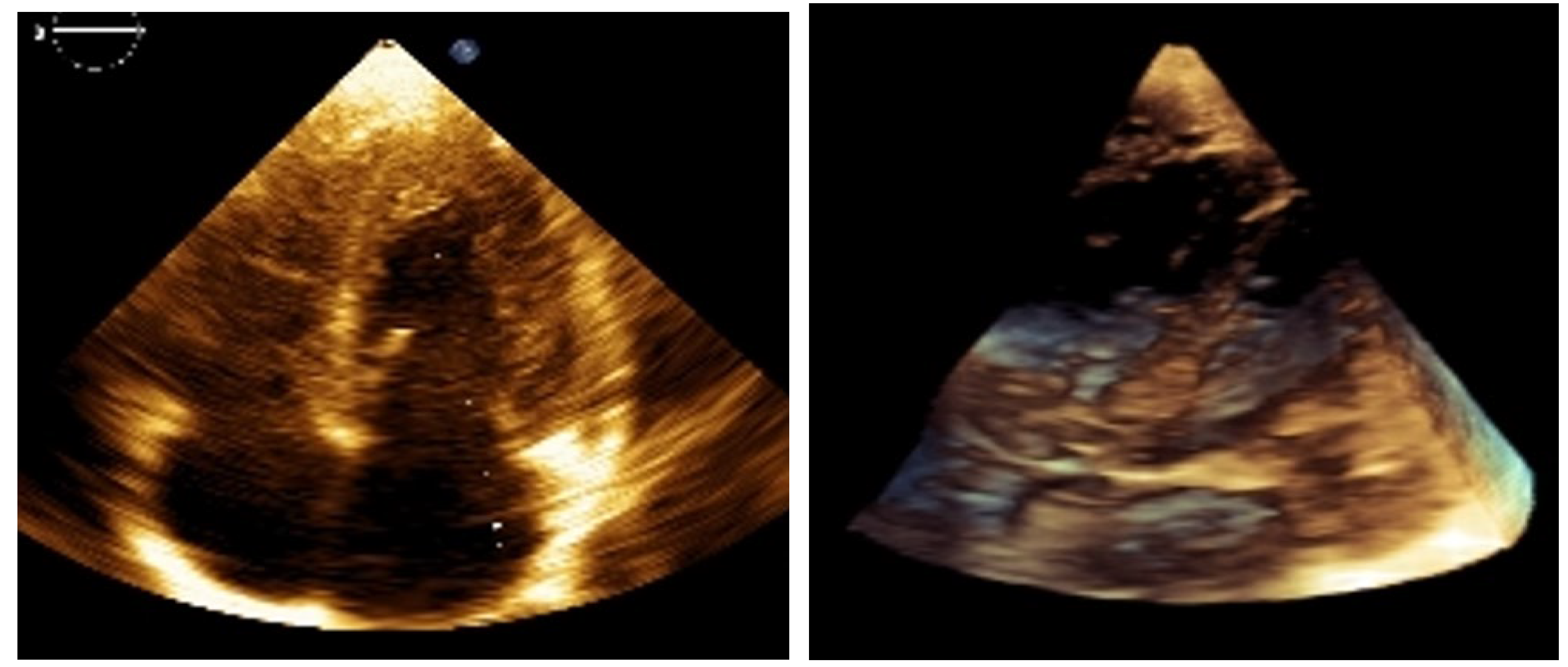

Figure 2.

2D and 3D images at 9 months post-treatment. Everolimus therapy (Rapamune) began at 3 months of age. Sirolimus, administered as an oral suspension, was started at a weight-adjusted dose based on the standard 1 mg/m² once daily (1 m² ≈ 30 kg). Serum levels were monitored every 8 weeks (therapeutic range: 4–10 ng/mL), and dose adjustments were made accordingly. Toxicity was assessed using CTCAE v3.0. SEGA response was evaluated using RECIST v1.1. Follow-ups were conducted at 6 and 9 months via echocardiography and at 12 months via CNS MRI. Clinically, the infant thrived, with no seizures or heart failure, and demonstrated normal weight gain. The best cardiac response (BCR) occurred between 4 and 6 months of therapy, with complete resolution of intracardiac tumors on echocardiography, shown on the images above.

Figure 2.

2D and 3D images at 9 months post-treatment. Everolimus therapy (Rapamune) began at 3 months of age. Sirolimus, administered as an oral suspension, was started at a weight-adjusted dose based on the standard 1 mg/m² once daily (1 m² ≈ 30 kg). Serum levels were monitored every 8 weeks (therapeutic range: 4–10 ng/mL), and dose adjustments were made accordingly. Toxicity was assessed using CTCAE v3.0. SEGA response was evaluated using RECIST v1.1. Follow-ups were conducted at 6 and 9 months via echocardiography and at 12 months via CNS MRI. Clinically, the infant thrived, with no seizures or heart failure, and demonstrated normal weight gain. The best cardiac response (BCR) occurred between 4 and 6 months of therapy, with complete resolution of intracardiac tumors on echocardiography, shown on the images above.

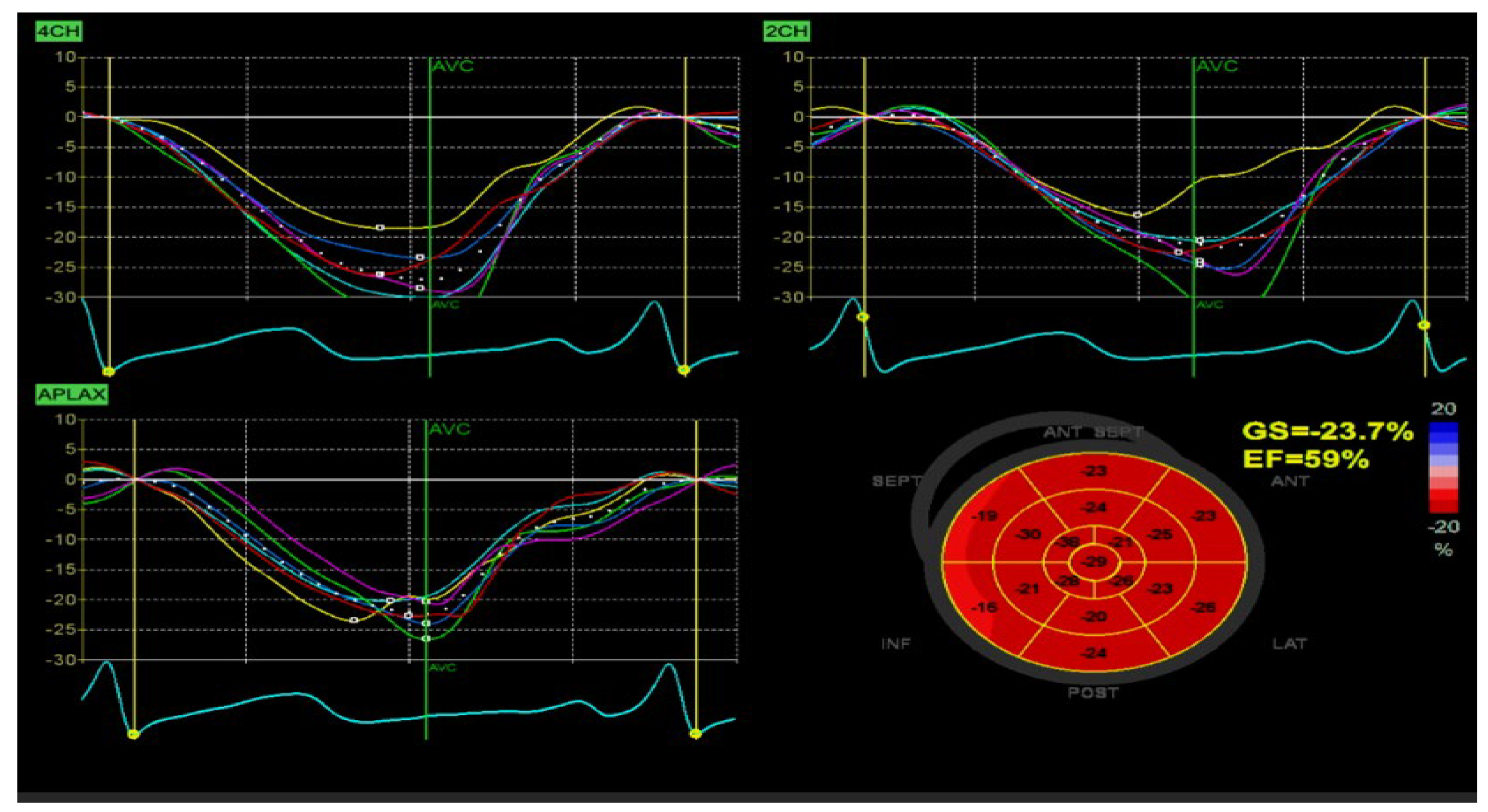

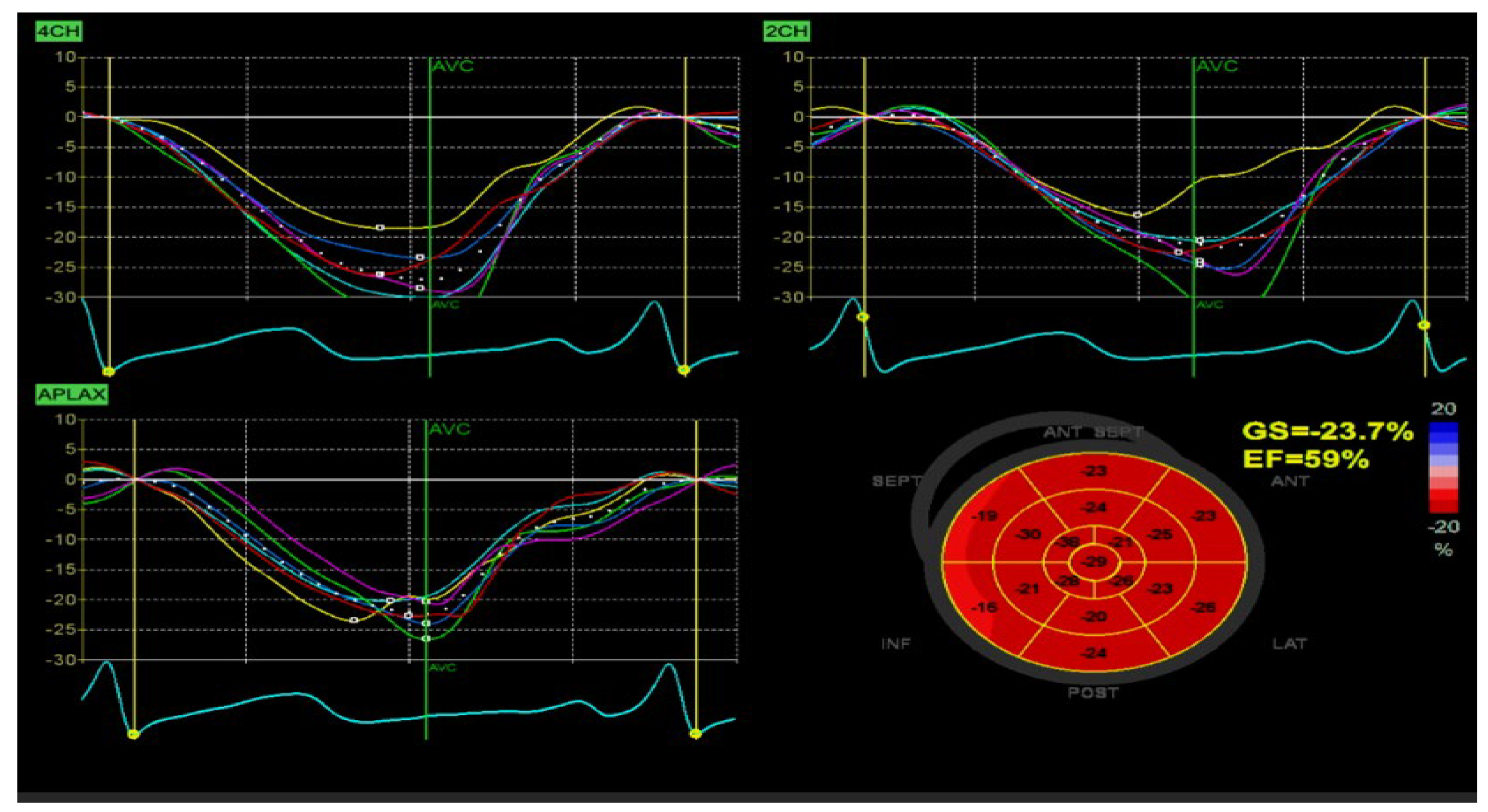

Figure 3.

Myocardial deformation indices at 9 months, demonstrating absence of residual intramural lesions. The patient, a male infant (therapy from April 2024 to January 2025), had a birth weight of 1980 g, increasing to 4000 g by therapy initiation. He remained clinically stable, with no cardiac or CNS symptoms, nor abnormalities found by exams. Myocardial strain at 9 months showed normal global longitudinal strain (GLS, −23.7%), supporting therapy discontinuation in light of tumor disappearance. Cardiac involvement in TSC often predominates in the fetal and early infant periods, typically followed by spontaneous involution. In our case, sirolimus demonstrated significant efficacy in treating multiple, large CRs, both intracavitary and intramural, without rhythm or conduction abnormalities. A key question during follow-up was the timing of therapy discontinuation, confirmation of intramural lesion resolution, and monitoring of myocardial deformation indices. Treatment resulted in complete tumor resorption—i.e., a full therapeutic response. For CNS lesions, mass reduction decreases refractory epilepsy risk. mTOR inhibitors may be crucial in neonates or infants with CRs and cardiac complications, as rapid tumor volume reduction can improve prognosis by alleviating life-threatening arrhythmias or intracardiac obstructions, reducing surgical intervention. Case reports and small series support mTOR inhibitor use in infants and fetuses [

11,

12,

13,

14].

Figure 3.

Myocardial deformation indices at 9 months, demonstrating absence of residual intramural lesions. The patient, a male infant (therapy from April 2024 to January 2025), had a birth weight of 1980 g, increasing to 4000 g by therapy initiation. He remained clinically stable, with no cardiac or CNS symptoms, nor abnormalities found by exams. Myocardial strain at 9 months showed normal global longitudinal strain (GLS, −23.7%), supporting therapy discontinuation in light of tumor disappearance. Cardiac involvement in TSC often predominates in the fetal and early infant periods, typically followed by spontaneous involution. In our case, sirolimus demonstrated significant efficacy in treating multiple, large CRs, both intracavitary and intramural, without rhythm or conduction abnormalities. A key question during follow-up was the timing of therapy discontinuation, confirmation of intramural lesion resolution, and monitoring of myocardial deformation indices. Treatment resulted in complete tumor resorption—i.e., a full therapeutic response. For CNS lesions, mass reduction decreases refractory epilepsy risk. mTOR inhibitors may be crucial in neonates or infants with CRs and cardiac complications, as rapid tumor volume reduction can improve prognosis by alleviating life-threatening arrhythmias or intracardiac obstructions, reducing surgical intervention. Case reports and small series support mTOR inhibitor use in infants and fetuses [

11,

12,

13,

14].

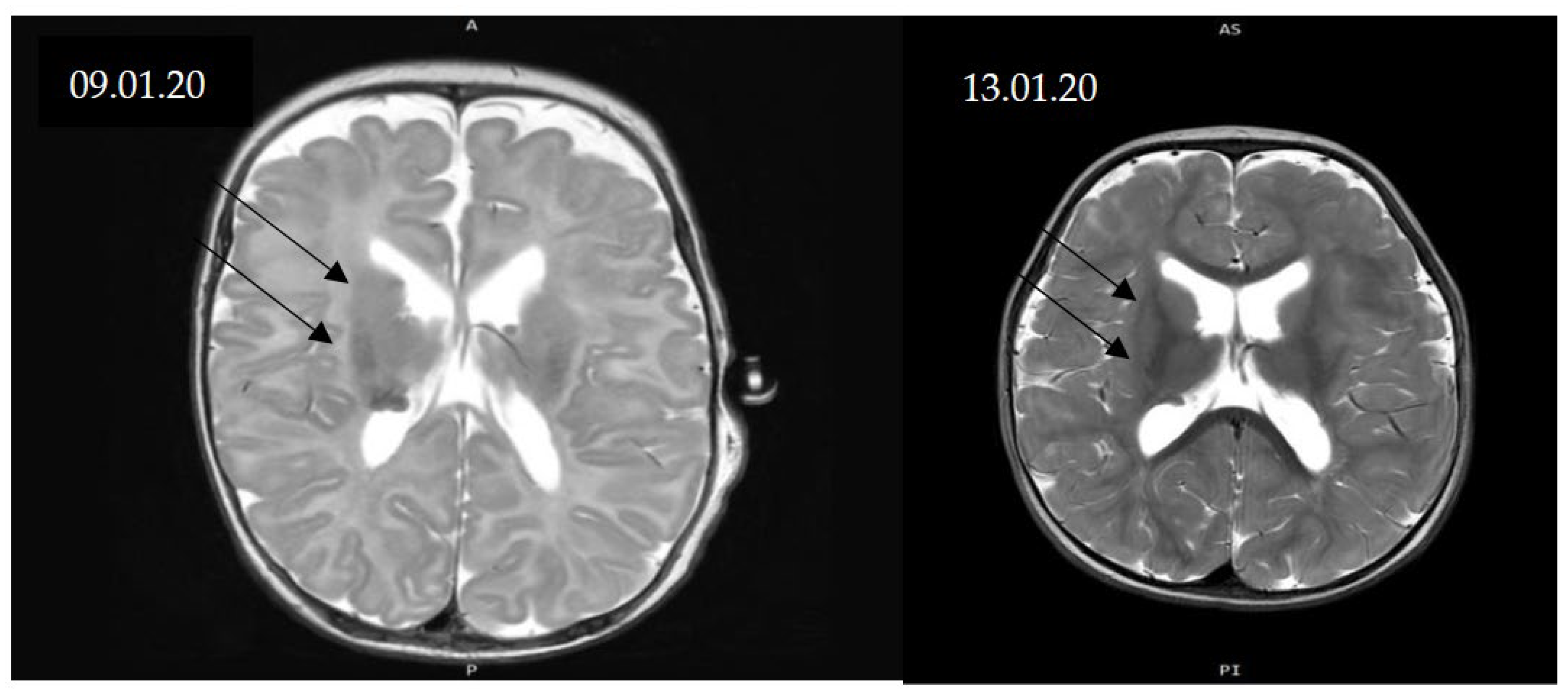

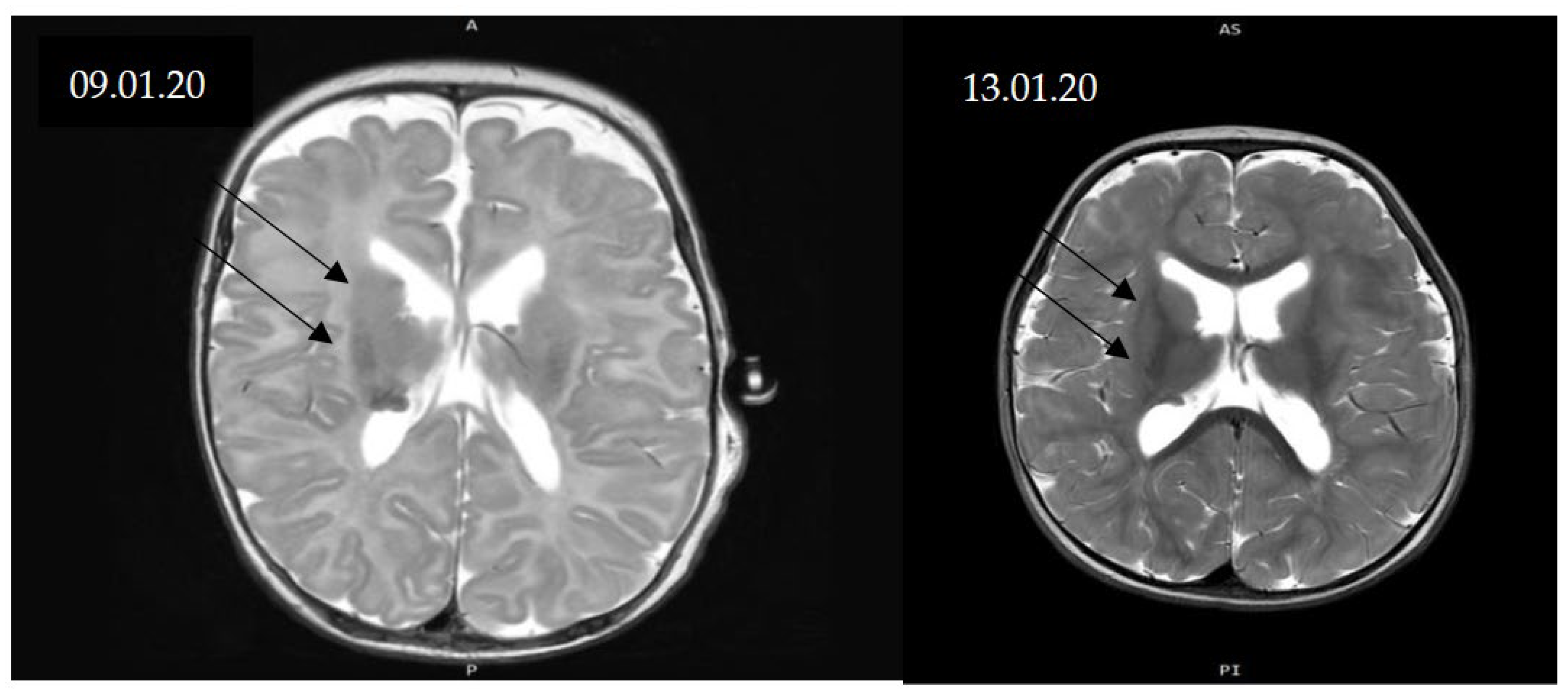

Figure 4.

MRI scans before treatment and at 9 months. CNS changes in TSC include subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas (SEGAs), epilepsy, intellectual disability, and autism spectrum disorder. In certain cases, SEGA may require surgical resection, particularly when causing obstructive hydrocephalus; incomplete excision is associated with a propensity for recurrence. Recently introduced oral mTOR inhibitors in mammalian models have shown efficacy in reducing SEGA volume and improving seizure control in patients with TSC-related intractable epilepsy. Currently, no randomized clinical trials have been conducted in infants (0–36 months), particularly those younger than 12 months, to assess drug dosing and CNS lesion evolution. The aim of our study was to assess the safety and efficacy of daily sirolimus treatment for CRs and SEGAs in a single case under 12 months of age with genetically confirmed TSC, as well as echocardiography as a diagnostic and tracking method. MRI-confirmed SEGA diagnosis pre-therapy and at 12 months showed partial response without significant size progression and no seizures. Main CNS lesions were subependymal along both lateral ventricles, with normal ventricular morphology. MRI follow-up showed CNS manifestations stabilized, with partial regression in over 50% of lesions and absence of seizures.

Figure 4.

MRI scans before treatment and at 9 months. CNS changes in TSC include subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas (SEGAs), epilepsy, intellectual disability, and autism spectrum disorder. In certain cases, SEGA may require surgical resection, particularly when causing obstructive hydrocephalus; incomplete excision is associated with a propensity for recurrence. Recently introduced oral mTOR inhibitors in mammalian models have shown efficacy in reducing SEGA volume and improving seizure control in patients with TSC-related intractable epilepsy. Currently, no randomized clinical trials have been conducted in infants (0–36 months), particularly those younger than 12 months, to assess drug dosing and CNS lesion evolution. The aim of our study was to assess the safety and efficacy of daily sirolimus treatment for CRs and SEGAs in a single case under 12 months of age with genetically confirmed TSC, as well as echocardiography as a diagnostic and tracking method. MRI-confirmed SEGA diagnosis pre-therapy and at 12 months showed partial response without significant size progression and no seizures. Main CNS lesions were subependymal along both lateral ventricles, with normal ventricular morphology. MRI follow-up showed CNS manifestations stabilized, with partial regression in over 50% of lesions and absence of seizures.

Author Contributions

Corresponding Author, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—Original Draft: Dr. Rumen Marinov; Genetic Analysis: Dr. Daniela Avdjieva-Tzavella; Requested to not share e-mail; Pediactric Oncology: Dr. Ivan Chakarov; Requested to not share e-mail; Pediatrics: Dr. Valentin Dimitrov. Requested to not share e-mail. Technical Assistant, Writing—Editing, Corrections: Med. Student Radoslav Iliev.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Cardiology Hospital of Bulgaria (approval code LEC-Sofia-NKB-2024/02/1339 and date of approval 20.02.2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for publication has been obtained from the subject’s relatives.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sirolimus in infants with Multiple Cardiac Rhabdomiomas Lucchesi M.;Chiappa E.,Mari F.,Genitori L., Sardi I. Rep Oncol (2018) 11 (2): 425–430.

- Watson, GH. Cardiac rhabdomyomas in tuberous sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;615.3. Jóźwiak S, Kotulska K, Kasprzyk-Obara J, Domańska-Pakieła D, Tomyn-Drabik M, Roberts P, et al. Clinical and genotype studies of cardiac tumors in 154 patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Pediatrics. 2006.

- Erdmenger Orellana J, Vázquez C, Ortega Maldonado J. [Echocardiography in diagnosis of primary cardiac tumors in pediatrics]. Arch Cardiol Mex. 2005.

- Holmes, G.L.; Stafstrom, C.E. ; The Tuberous Sclerosis Study Group Tuberous Sclerosis Complex and Epilepsy: Recent Developments and Future Challenges. Epilepsia 2007, 48, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byard, R.; Blumbergs, P.; James, R. Mechanisms of Unexpected Death in Tuberous Sclerosis. J. Forensic Sci. 2003, 48, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, D.A.; Care, M.M.; Holland, K.; Agricola, K.; Tudor, C.; Mangeshkar, P.; Wilson, K.A.; Byars, A.; Sahmoud, T.; Franz, D.N. Everolimus for Subependymal Giant-Cell Astrocytomas in Tuberous Sclerosis. New Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1801–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, D.A.; Care, M.M.; Agricola, K.; Tudor, C.; Mays, M.; Franz, D.N. Everolimus long-term safety and efficacy in subependymal giant cell astrocytoma. Neurology 2013, 80, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardamone, M.; Flanagan, D.; Mowat, D.; Kennedy, S.E.; Chopra, M.; Lawson, J.A. Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Inhibitors for Intractable Epilepsy and Subependymal Giant Cell Astrocytomas in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. J. Pediatr. 2014, 164, 1195–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franz, D.N.; Belousova, E.; Sparagana, S.; Bebin, E.M.; Frost, M.; Kuperman, R.; Witt, O.; Kohrman, M.H.; Flamini, J.R.; Wu, J.Y.; et al. Everolimus for subependymal giant cell astrocytoma in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: 2-year open-label extension of the randomised EXIST-1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiberio, D.; Franz, D.N.; Phillips, J.R. Regression of a Cardiac Rhabdomyoma in a Patient Receiving Everolimus. Pediatrics 2011, 127, e1335–e1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breathnach, C.; Pears, J.; Franklin, O.; Webb, D.; McMahon, C.J. Rapid Regression of Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Rhabdomyoma After Sirolimus Therapy. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e1199–e1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.-S.; Chiou, P.-Y.; Yao, S.-H.; Chou, I.-C.; Lin, C.-Y. Regression of Neonatal Cardiac Rhabdomyoma in Two Months Through Low-Dose Everolimus Therapy: A Report of Three Cases. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2017, 38, 1478–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiland, M.D.; Bonello, K.; Hill, K.D. Rapid regression of large cardiac rhabdomyomas in neonates after sirolimus therapy. Cardiol. Young- 2017, 28, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, E.; Gomez, M.R.; Northrup, H. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference: Revised Clinical Diagnostic Criteria. J. Child Neurol. 1998, 13, 624–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).