1. Introduction

Understanding the intricate link between neurological diseases—especially seizures, epilepsy, and multiple sclerosis (MS) in pediatric populations—has drawn increasing interest recently [

1,

2,

3]. This study seeks to investigate these interconnected conditions in a cohort of 120 children with MS, 6 of whom (5%) have seizures and epilepsy.

Seizures, defined as abrupt, uncontrolled electrical disruptions in the brain, are a frequent manifestation in children with neurological diseases and can greatly reduce quality of life [

4,

5]. Epilepsy, characterized by recurrent unprovoked seizures, often coexists with other neurological illnesses, including MS, a chronic central nervous system disorder that can cause diverse neurological symptoms [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Epilepsy is one of the most common chronic neurologic disorders in childhood, particularly in the first 10 years of life, affecting around 0.5–1% of children worldwide [

8]. Reported prevalence is about 17.3 per 1000 children (range 3.2–44) with an incidence of 41–187 per 100,000 person-years [

9] and approximately 2.5 per 1000 in some studies [

8]. In contrast, MS is very rare in pediatric ages; less than 5% of all MS cases begin before 18 years old [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Although these two conditions seldom appear in the same individual (only about 2–3% of MS patients have comorbid epilepsy), this percentage is higher than in the general population [

14,

15,

16,

17] and seems to be even greater in younger patients (reported at 5–10% in pediatric MS cohorts) [

18,

19].

When examining the mechanisms that might link MS and epilepsy in children, the situation becomes complex and remains poorly understood. It is unclear whether there is a direct association or if they co-occur as independent conditions. Multiple pathophysiological mechanisms have been suggested which provide incomplete explanations for the development of epilepsy in patients with MS. These include neuroinflammation due to demyelinating lesions in both white and gray matter [

1,

20,

21], global cerebral atrophy especially involving the hippocampus and other temporal lobe structures (key epileptogenic areas) [

1,

21,

22,

23], impairment of blood–brain barrier (BBB) function leading to heightened neuronal excitability [

24,

25,

26], and the proinflammatory role of excessive glutamate signaling [

23,

25]. Despite these factors, many MS patients appear to have a degree of “resilience” to developing seizures [

2,

19,

27].

The gray matter regions that make up the hippocampus and insula together with the frontal and temporal lobes play a central role in epilepsy because they are prone to generate seizures. The seizures trigger inflammation because of the activation of abnormal neuronal circuits [

1,

20,

21]. The inflammatory response can result in blood-brain barrier dysfunction and glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity through glutamate while promoting epileptogenic processes [

2,

24,

26]. Meanwhile, the known etiologies of epilepsy in children are diverse; genetic mutations and structural abnormalities (malformations of cortical development – e.g., focal cortical dysplasia [

28] or tumors) are among the most common causes, alongside metabolic, immune [

29], infectious, and acute injury causes (head trauma, stroke) [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Notably, genetic and autoimmune influences can coexist. As we see, inflammation, BBB disruption, and glutamate-mediated excitability are several mechanisms common to both MS and epilepsy.

Through this research, we aim to highlight the heterogeneity of epilepsy manifestations in children with MS and explore possible processes connecting these diseases. In our study cohort, patients with both MS and epilepsy had a significantly higher last EDSS score (indicating greater disability accumulation after at least 2 years of monitoring; p < 0.006) compared to those without epilepsy. Recognizing these patterns may help refine diagnostic and treatment approaches for this unique patient group.

2. Materials and Methods

The present retrospective observational study covers a 7-year period (January 2018–December 2024). We reviewed medical records of pediatric patients (<18 years) with MS who were diagnosed, monitored, and treated in the Pediatric Neurology Department of “Prof. Dr. Alexandru Obregia” Clinical Hospital of Psychiatry in Bucharest, Romania, the largest tertiary pediatric neurology center in the country.

A total of 120 subjects were selected, who met the 2017 revised McDonald criteria (2017) for MS diagnosis. Among these, 6 children (3 boys and 3 girls; median age 9.8 years, range 4.6–15.3 years) experienced seizures or epilepsy. Detailed data on their epileptic events (age at seizure onset; timing relative to MS onset; seizure type, frequency, and duration; whether an epilepsy diagnosis was established; anti-epileptic treatment; and whether seizure control was achieved) are summarized in

Table 1. Seizure and epilepsy types were classified according to the latest ILAE recommendations (the 2017 ILAE seizure classification and the 2022 ILAE epilepsy classification).

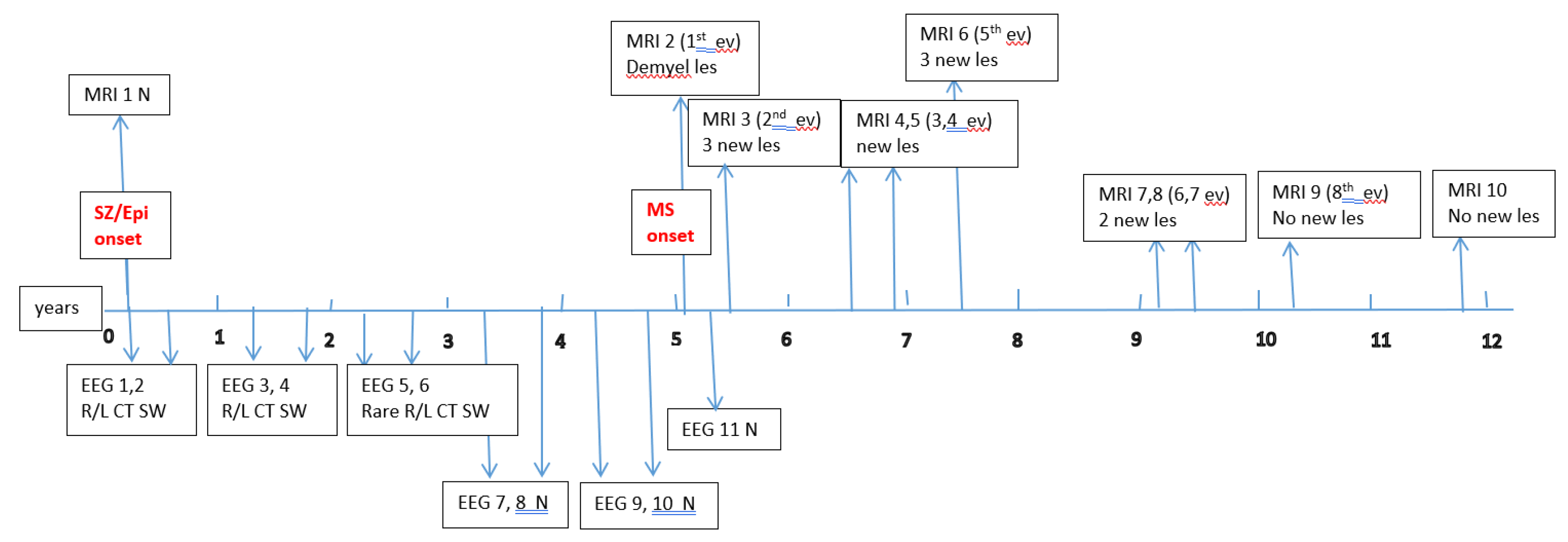

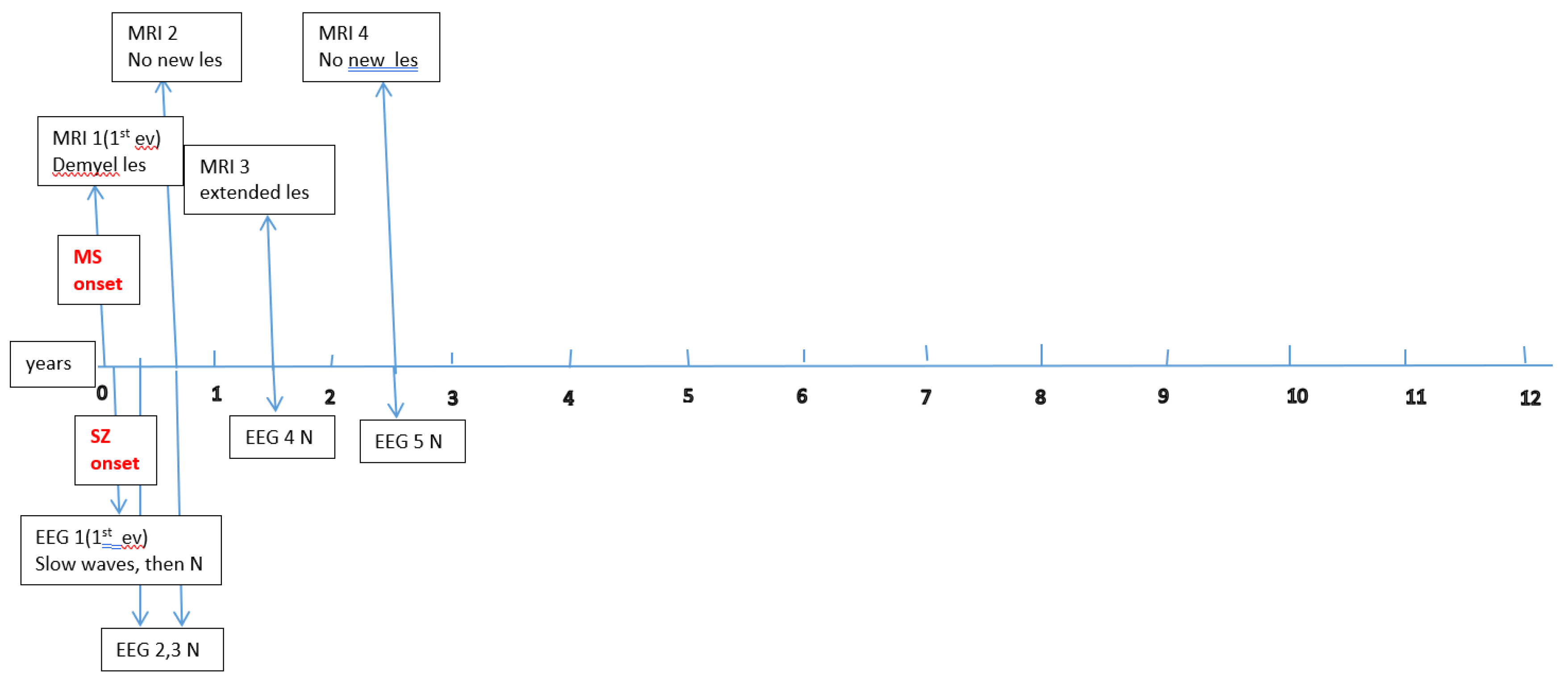

Data about each patient’s electroencephalography (EEG) and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings at MS onset and during disease evolution were collected.

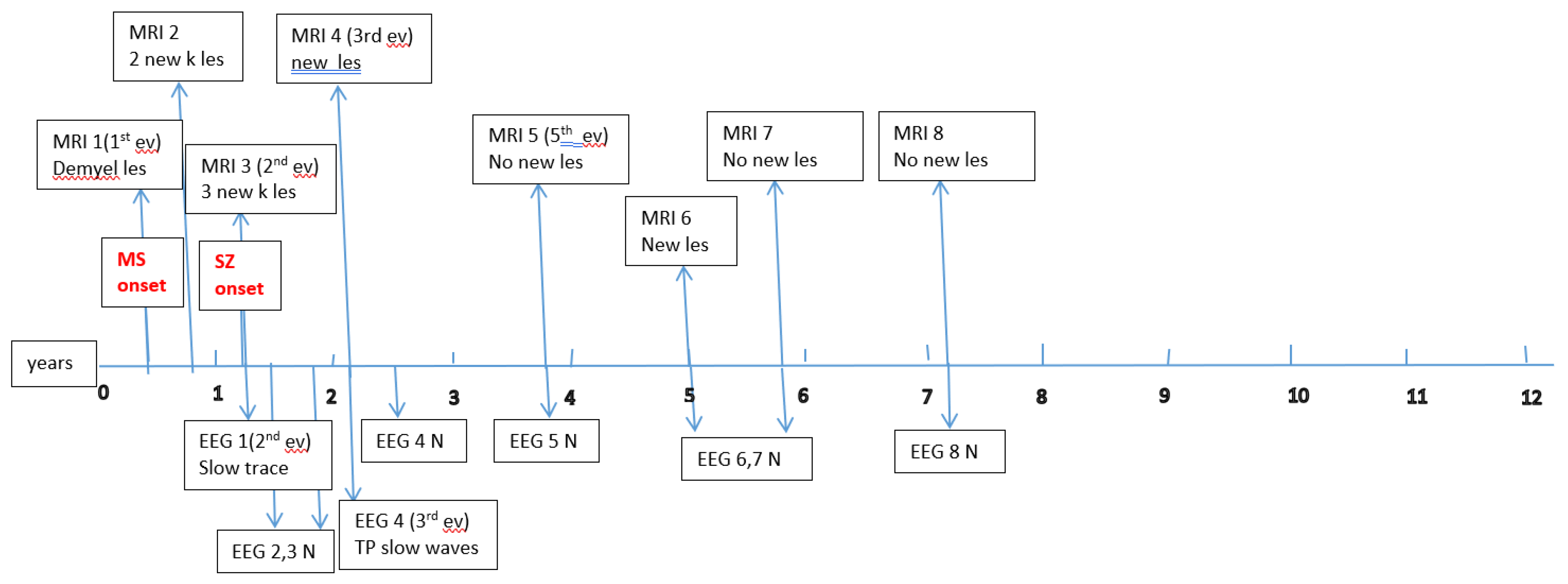

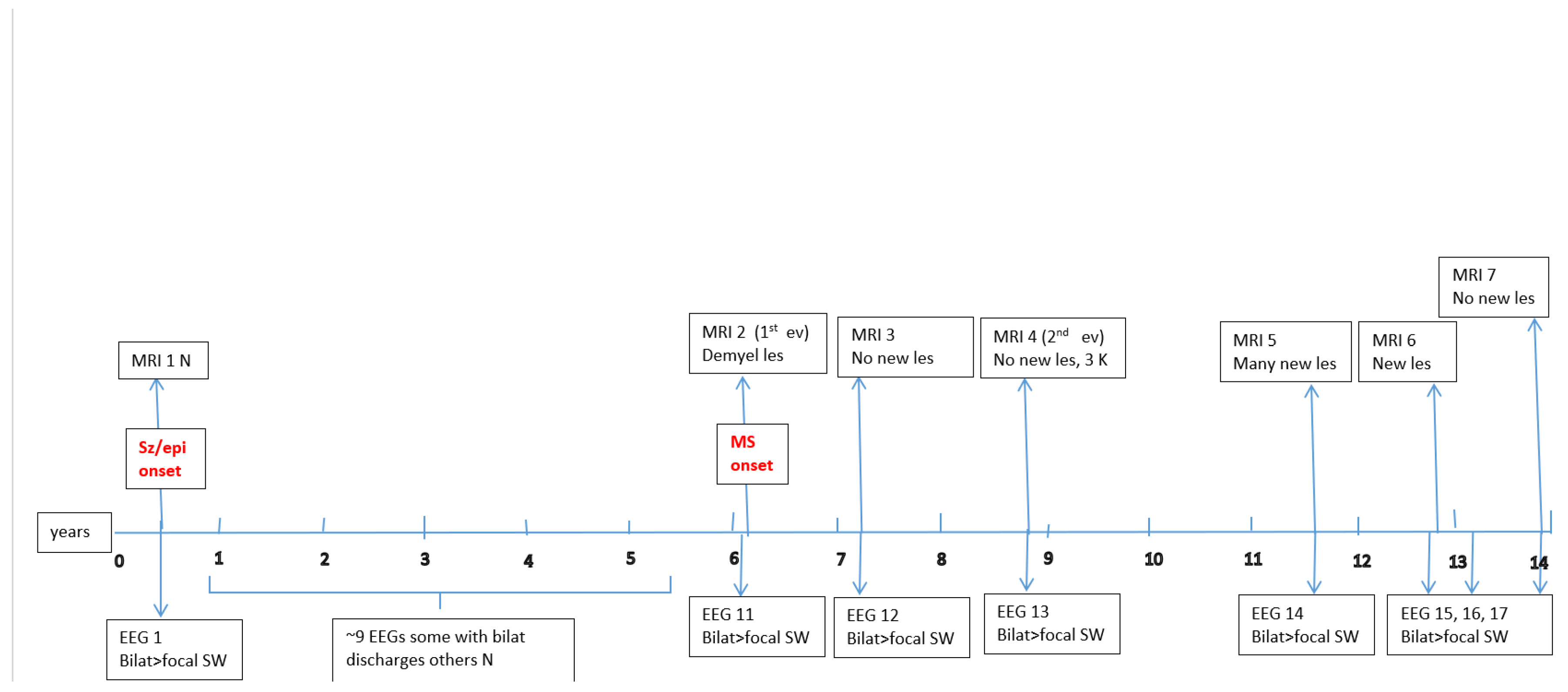

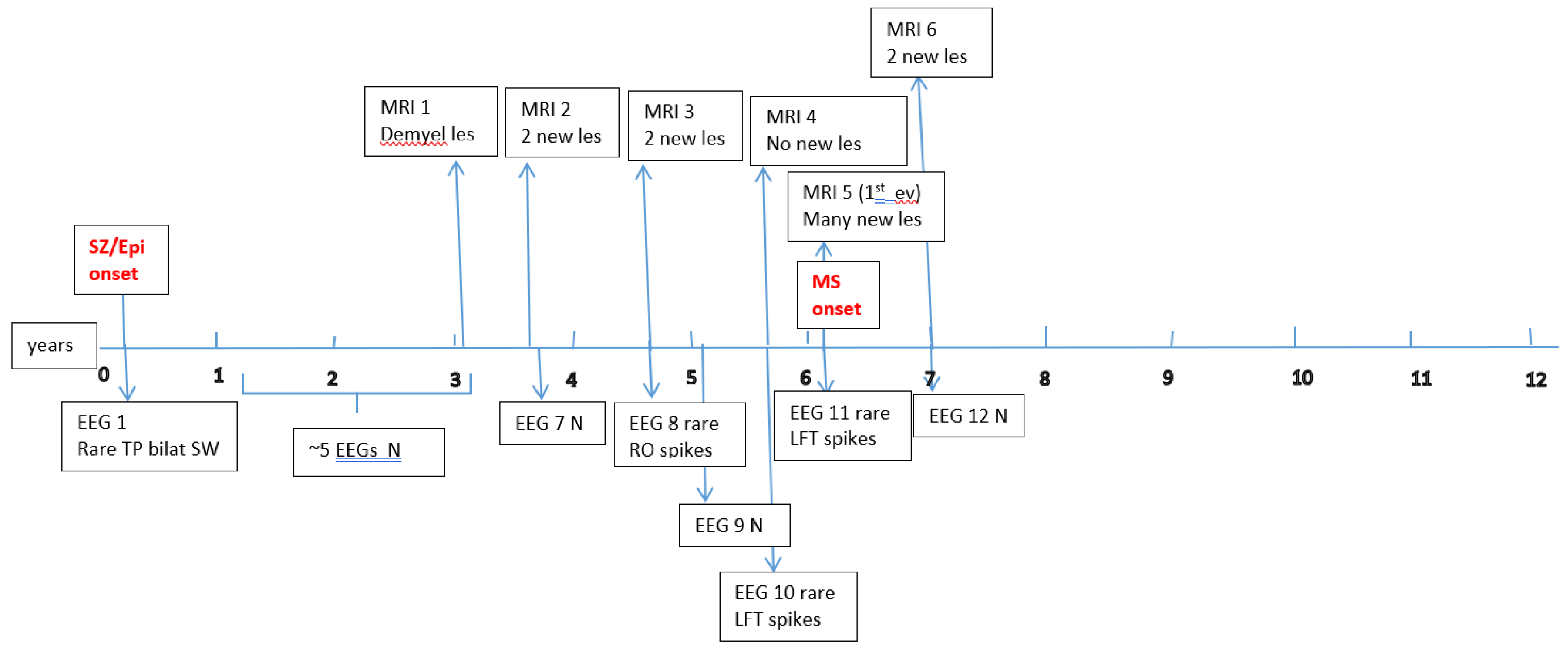

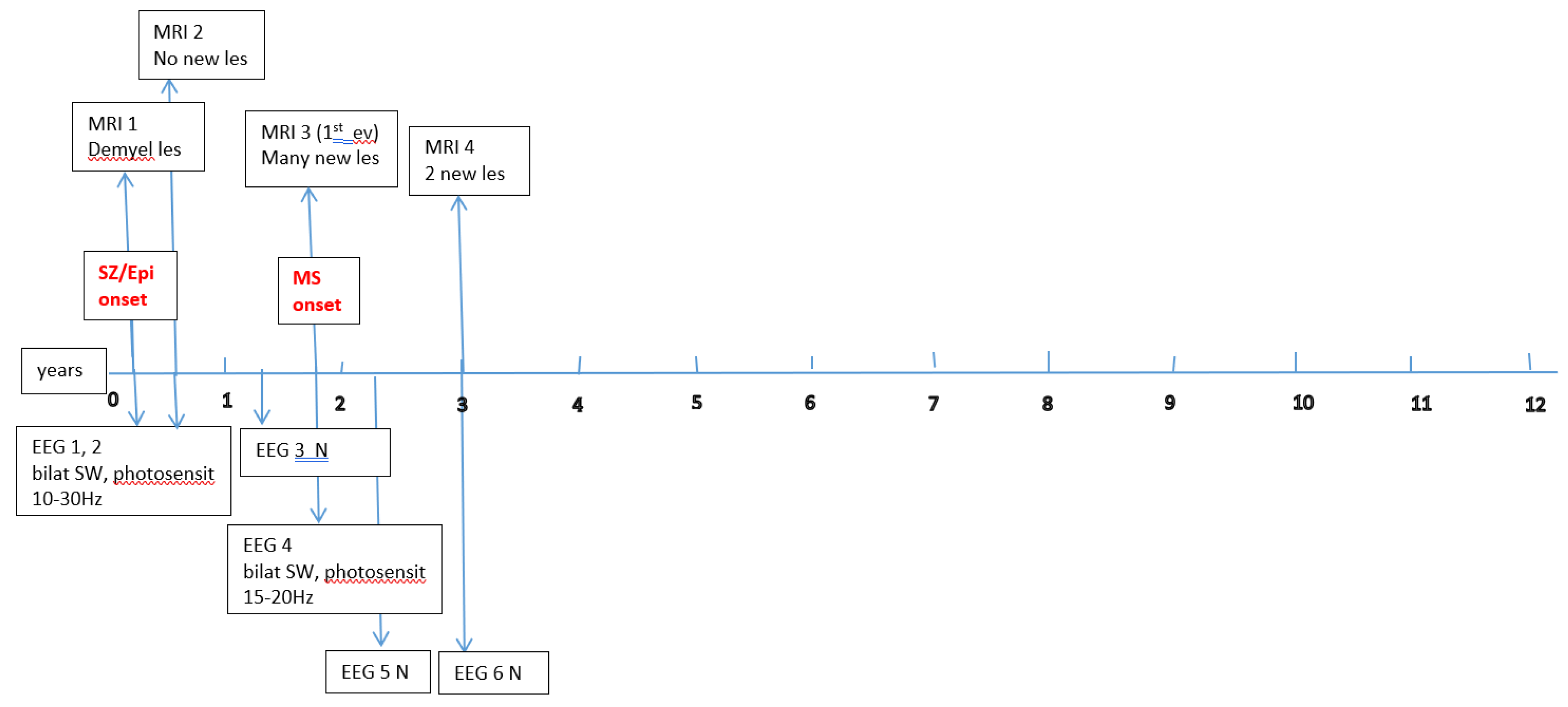

Figure A1,

Figure A2,

Figure A3,

Figure A4,

Figure A5 and

Figure A6 (see

Appendix A) show these EEG and MRI data for the six patients. For EEG recordings, the international 10–20 system was used with a double banana montage and additional ECG channel; all 6 patients had at least one prolonged EEG (3–4 hours) that included both awake and sleep recording. Brain MRI scans were performed on a 1.5T scanner, without and with gadolinium contrast.

Although there is a large discrepancy in group sizes (MS with seizures n = 6; MS without seizures n = 114), we compared disease progression between these groups using annual EDSS scores and observed that there is a significant statistical correlation with the last EDSS score (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the hospital’s ethics committee, and written informed consent was obtained for all patients (from parents or legal guardians for minors). For statistical analysis and data processing, we used JASP 0.19. Categorical comparisons were made using the chi-square test with Yates’ continuity correction. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Our main focus was to describe the particular characteristics of the small group of patients with MS who also developed epilepsy.

3.1. Concerning Seizures and Epilepsy

Among the six children, seizure onset occurred before 10 years of age in 3 patients (50%); one child experienced their first seizure at age 10 (16.66%); and the remaining two had seizure onset during adolescence (33.3%). In four patients (66.66%), seizures began before the onset of MS. These four were diagnosed with epilepsy years before MS was recognized, with a median interval of 4.7 years (range 1.8–6.5 years) between epilepsy onset and MS onset. By contrast, in the two patients whose first seizures occurred after MS onset, the latency was much shorter and seemed temporally associated with MS relapses—one had a seizure 2 weeks after the first MS episode, and the other had seizures ~9 months after MS onset as part of the second relapse. In the latter patient, it was also the only seizure and it took the form of a focal prolonged seizure with impairment of consciousness at the end of the status, followed by sloth, left central facial palsy and a transient bipyramidal syndrome lasting a few days. Even though this was considered an acute episode, given the prolonged seizure and high risk of recurrence, the child received anti-seizure medication for 6 months. This intervention resulted in a good outcome, with no further seizures and a normal EEG during follow-up.

The other teenager who had seizures shortly after his first MS relapse, was treated with anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) for two years, because his repeated focal alternate seizures eventually led to a diagnosis of focal structural epilepsy (with a probable autoimmune etiology). Furthermore, in this case, the evolution was favorable, and he has now been seizure-free for about 3 years and has been off AEDs.

Among the subjects whose seizures predated MS, two appear to meet the criteria for a genetic form of epilepsy — focal-seizures, respectively generalized-IGEs according to the recent ILAE seizures and epilepsy classification, although any immune contribution in these cases remains unclear. The other two patients in this subgroup present a more complex situation: they continue to have uncontrolled, pharmacoresistant seizures despite polytherapy (3–4 anti-seizure drugs), with multiple seizure types and persistent EEG epileptiform discharges. Notably, one had a history of simple febrile seizures in early childhood (before epilepsy onset), and another had a family history of epilepsy; both of these patients experienced an increase in seizure frequency after MS onset, suggesting a possible combination of genetic and autoimmune etiologies. In two of the four patients whose seizures started before MS, the early brain MRI scans (at the time of initial seizures) were normal.

Four children (67%) had a history of at least one simple febrile seizure in infancy; one patient had a first-degree relative with adolescent-onset epilepsy; and another had a first-degree relative with adult-onset MS. At last follow-up, four of the six children (67%) achieved good seizure control, with three of them off any anti-seizure medication, whereas two patients (33%) have ongoing drug-resistant epilepsy.

Table 1 lays out these details for each patient. Each child underwent multiple EEG studies, especially during periods of disease worsening or medication changes. Approximately one-third of all EEGs were prolonged recordings (including sleep), while the others were standard awake EEGs with activation procedures (hyperventilation and intermittent photic stimulation).

Figure A1,

Figure A2,

Figure A3,

Figure A4,

Figure A5 and

Figure A6 (see

Appendix A) provide illustrative EEG and MRI findings for each patient.

3.2. Concerning MS

Concerning the MS presentations in these six patients, the initial clinical features of MS were as follows: hemiparesis in 4 cases (66.7%); a combination of hemiparesis, cerebellar syndrome, and multiple cranial nerve involvement in 1 case; and a sensitivity disturbance in 1 case. The age at MS onset was <10 years in one patient, 10–12 years in two patients, and >12 years in three patients. Two patients had an initial presentation consistent with an isolated clinical syndrome (ICS), while four patients had a relapsing-remitting MS course from onset. Oligoclonal bands in cerebrospinal fluid were positive in four patients (one described as “intensely positive”) and negative in two. The two ICS patients experienced only a single MS attack to date, whereas the other four have had multiple relapses (2, 4, 7, and 8 acute events respectively over their disease course). All six patients received disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for MS: four patients were treated with a single DMT (two on moderate-efficacy injectables like interferon-beta, and two on high-efficacy therapies like fingolimod), and the remaining two patients required escalation through multiple DMTs (they started with intravenous immunoglobulin during early childhood when DMTs were contraindicated due to age, then switched to interferon, and later to fingolimod – which are the therapies available in our country for pediatric MS).

Figure A1,

Figure A2,

Figure A3,

Figure A4,

Figure A5 and

Figure A6 (see

Appendix A) illustrate the burden and characteristics of demyelinated brain lesions in these patients, which varied according to disease activity (relapse count), particularly prior to initiating DMTs.

All six patients have been followed for at least two years from MS diagnosis. We sought to determine whether the occurrence of epilepsy could be a risk factor for more rapid MS progression and disability accumulation. In our cohort, the EDSS began to diverge from 0 (no disability) after 2–3 years of disease in those with epilepsy. A comparative analysis of annual EDSS progression between MS patients with epilepsy and those without showed that by the last follow-up, the epilepsy group had significantly higher EDSS scores on average. As noted, the difference in outcome was statistically significant (p < 0.006 for the latest EDSS values comparison).

4. Discussion

These findings highlight the main goal of this article: to demonstrate that juvenile patients with MS and epilepsy constitute a heterogeneous and complex group, making it challenging to define the precise relationship between these two disorders. The inflammatory process in MS is known to be more pronounced in children [

34,

35] than in adults—and an earlier onset of MS implies a longer duration of disease and cumulative burden of cognitive and motor deficits [

34,

35].

Epilepsy remains one of the most prevalent pediatric neurological disorders (“a childhood disease”) [

6,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Genetic and structural etiologies are the most common causes of epilepsy in the pediatric population; therefore, when epilepsy arises in a child who also develops MS, we cannot rule out a possible link between genetic-autoimmune origins common to their age group. In our series, we indeed suspect that in some patients, the epilepsy is primarily genetic (with MS perhaps adding an inflammatory aggravating factor), whereas in others the epilepsy might be more directly related to MS (immune-mediated).

In a young developing nervous system, the intersection of MS and epilepsy in the same individual raises critical questions about how these conditions interact and to what extent they influence each other’s course. This calls for a multidisciplinary perspective—pediatric neurologists, epileptologists, and even psychiatrists and immunologists need to collaborate to untangle the contributions of neuroinflammation, genetics, and other factors. Future multi-center research on larger pediatric cohorts is needed to clarify these interactions.

Answering these questions could guide clinicians in choosing appropriate treatments for MS and seizures in such patients. Notably, some anti-epileptic drugs may not be ideal in the context of MS-related seizures (for example, certain AEDs might aggravate seizures [

36,

37]), while some DMTs for MS appear to also help in managing seizures [

34,

35].

In our study, two patients seem to have seizures most directly related to their MS disease activity, whereas in two other patients, the seizures are likely due to an underlying primary genetic epilepsy, with MS as an additional factor. We hypothesize that even in those presumed genetic cases, the superimposed neuroinflammation of MS might influence the epilepsy course (for example, making seizures more frequent or difficult to control). Conversely, for the last two patients, we suspect a true convergence of etiologies—an interaction of genetic predisposition and autoimmune demyelination contributing jointly to their epilepsy—which could explain their particularly challenging course. However, determining the exact contribution of each factor will require further research, potentially including genetic testing and immunological profiling, which were limitations in our study.

Regarding disease progression, our finding that epilepsy may be a risk factor for increasing disability in pediatric MS, aligns with some reports in adult MS populations that have noted worse outcomes in MS patients with seizures [

2,

3,

17]. On the other hand, other studies in pediatric MS found that comorbid epilepsy did not significantly affect MS outcomes [

19]. We underline that in our study, epilepsy appeared to be a risk factor for a higher last EDSS score and disability accumulation, and we evaluated it in relation to other risk factors that influenced the outcome: small age at MS onset and long course of the disease, and the fact that most of these patients have a very active form with many relapses, especially before DMTs onset. Therefore, while epilepsy might independently worsen MS prognosis, it often comes in a context of aggressive MS. Long-term, multicenter studies are needed to confirm if seizures themselves drive faster progression or if they are simply a marker of a more severe disease phenotype. The small single-center group and the lack of genetic testing on these patients because of their financial status—they are not free in our country—are limitations of this study.

In summary, pediatric patients with MS and epilepsy form a distinct subset that requires careful, individualized attention. The intersection of a demyelinating autoimmune disorder with a neurological excitability disorder (epilepsy) calls for an interdisciplinary approach and more research. A better understanding of the pathophysiological crosstalk between MS and epilepsy in children could inform more effective therapeutic strategies—such as early aggressive treatment of MS to prevent inflammatory insults that might trigger seizures, and judicious selection of AEDs that do not negatively interact with the demyelinating process.

5. Conclusions

The group of pediatric MS patients who develop epilepsy represents a unique population that displays various etiologies and clinical trajectories which have not yet been fully understood. Our single-center experience highlights that these children warrant special attention and further investigation to better delineate the particularities of this overlap. The development of tailored treatment strategies for both conditions relies on an improved understanding of their interaction. When seizures arise alongside demyelinating diseases like MS the investigation must include a thorough review of standard pediatric epilepsy causes especially genetic ones. The simultaneous presence of these conditions may result from coincidental factors or multiple causative elements. We live in an era of expanding genetic and immunological insights, and applying these to cases of MS–epilepsy comorbidity will enhance our understanding of disease mechanisms. In our cohort, epilepsy appeared to be associated with a higher risk of accumulating disability (rising EDSS scores) over time in some children with MS. This suggests that the occurrence of seizures in a pediatric MS patient may portend a more aggressive disease course and requires careful monitoring and potentially stronger treatment approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.D.D. and D.C.; Methodology: A.D.D., D.C., C.I. and M.-A.G.; Validation: D.C. and I.M.; Formal Analysis: M.-A.G. and O.T.-A.; Investigation: A.D.D., C.P., D.B., N.B., C.B., I.M., D.S., C.M., C.C., A.B., A.Ș.N., C.S. and D.A.I.; Data Curation: A.D.D., N.B., A.Ș.N., and A.B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: A.D.D.; Writing—Review & Editing: M.-A.G., A.M.G, A.D.D., D.C.; Visualization: M.-A.G. and A.-M.G.; Supervision: D.C. and D.A.I.; Project Administration: D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No external funding supported this research project. The MDPI Reviewer of the Year 2025 voucher which provided CHF 300 served as the source of funding for the article processing charge (APC). A PhD Scholarship funded the research conducted by the first author.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of “Prof. Dr. Alexandru Obregia” Clinical Hospital of Psychiatry (Bucharest, Romania; approval date: November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study (patients under 18, informed consent was obtained from their parents or legal guardians).

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study will be made available by the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families for their participation, and the staff of the Pediatric Neurology Department at “Prof. Dr. Alexandru Obregia” Clinical Hospital of Psychiatry for their support in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MS |

Multiple Sclerosis |

| ILAE |

International League Against Epilepsy |

| EDSS |

Expanded Disability Status Scale |

| BBB |

Blood–Brain Barrier |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| EEG |

Electroencephalography |

| JASP |

Jeffreys’s Amazing Statistics Program |

| AEDs |

Anti-Epileptic Drugs |

| IGEs |

Idiopathic Generalized Epilepsies |

| ICS |

Isolated Clinical Syndrome |

| DMTs |

Disease-Modifying Therapies |

| POMS |

Pediatric Onset Multiple Sclerosis |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

P1 Brain MRI & EEG frequence and aspect.

Figure A1.

P1 Brain MRI & EEG frequence and aspect.

Figure A2.

P2 Brain MRI & EEG frequence and aspect.

Figure A2.

P2 Brain MRI & EEG frequence and aspect.

Figure A3.

P3 Brain MRI & EEG frequence and aspect.

Figure A3.

P3 Brain MRI & EEG frequence and aspect.

Figure A4.

P4 Brain MRI & EEG frequence and aspect.

Figure A4.

P4 Brain MRI & EEG frequence and aspect.

Figure A5.

P5 Brain MRI & EEG frequence and aspect.

Figure A5.

P5 Brain MRI & EEG frequence and aspect.

Figure A6.

P6 Brain MRI & EEG frequence and aspect.

Figure A6.

P6 Brain MRI & EEG frequence and aspect.

References

- Rayatpour, A.; Farhangi, S.; Verdaguer, E.; Olloquequi, J.; Ureña, J.; Auladell, C.; Javan, M. The Cross Talk between Underlying Mechanisms of Multiple Sclerosis and Epilepsy May Provide New Insights for More Efficient Therapies. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 14(10), 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzilli, V.; Haggiag, S.; Di Filippo, M.; Capone, F.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Tortorella, C.; Gasperini, C.; Prosperini, L. Incidence and determinants of seizures in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2024, 95(7), 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durmus, H.; Kurtuncu, M.; Tuzun, E.; Pehlivan, M.; Akman-Demir, G.; Yapıcı, Z.; Eraksoy, M. Comparative clinical characteristics of early- and adult-onset multiple sclerosis patients with seizures. Acta Neurol Belg. 2013; 113, 421–426. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.S.; Cross, J.H.; French, J.A.; Higurashi, N.; Hirsch, E.; Jansen, F.E.; et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, M.; Uyttenboogaart, M.; Polman, S.; De Keyser, J. Seizures in multiple sclerosis. Epilepsia 2008, 49, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, I.E.; Berkovic, S.; Capovilla, G.; Connolly, M.B.; French, J.; Guilhoto, L.; Hirsch, E.; Jain, S.; Mathern, G.W.; Moshe, S.; et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: Position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K.S.; Cuascut, F.X.; Rivera, V.M.; Hutton, G.J. Current Advances in Pediatric Onset Multiple Sclerosis. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaberg, K.M.; Gunnes, N.; Bakken, I.J.; Lund Søraas, C.; Berntsen, A.; Magnus, P.; Lossius, M.I.; Stoltenberg, C.; Chin, R.; Surén, P. Incidence and Prevalence of Childhood Epilepsy: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Pediatrics 2017, May, 139(5):e20163908. [CrossRef]

- Camfield, P.; Camfield, C. Incidence, prevalence and aetiology of seizures and epilepsy in children. Epileptic Disord. 2015, 17, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupp, L.B.; Vieira, M.C.; Toledano, H.; Peneva, D.; Druyts, E.; Wu, P.; Boulos, F.C. A Review of Available Treatments, Clinical Evidence, and Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis in the United States. J Child Neurol. 2019, 34(10), 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitnis, T.; Aaen, G.; Belman, A.; Benson, L.; Gorman, M.; Goyal, M.S.; Graves, J.S.; Harris, Y.; Krupp, L.; Lotze, T.; Mar, S.; Ness, J.; Rensel, M.; Schreiner, T.; Tillema, J.M.; Waubant, E.; Weinstock-Guttman, B.; Roalstad, S.; Rose, J.; Weiner, H.L.; Casper, T.C.; Rodriguez, M. US Network of Paediatric Multiple Sclerosis Centers. Improved relapse recovery in paediatric compared to adult multiple sclerosis. Brain 2020, 143(9), 2733–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Balijepalli, C.; Desai, K.; Gullapalli, L.; Druyts, E. Epidemiology of pediatric multiple sclerosis: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020, Sep, 44:102260. [CrossRef]

- Sandesjö, F.; Tremlett, H.; Fink, K.; Marrie, R.A.; Zhu, F.; Wickström, R.; McKay, K.A. Incidence rate and prevalence of pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis in Sweden: A population-based register study. Eur J Neurol. 2024, May, 31(5):e16253. [CrossRef]

- Marrie, R.A.; Reider, N.; Cohen, J.; et al. A systematic review of the incidence and prevalence of sleep disorders and seizure disorders in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2015, 21, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burman, J.; Zelano, J. Epilepsy in multiple sclerosis: a nationwide population-based register study. Neurology 2017, 89, 2462–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grothe, M.; Ellenberger, D.; von Podewils, F.; et al. Epilepsy as a predictor of disease progression in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2022, 28, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grothe, M.; Ellenberger, D.; Rommer, P.S.; Stahmann, A.; Zettl, U.K. Epileptic seizures at multiple sclerosis onset and their role in disease progression. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2023, Oct 6, 16:17562864231192826. [CrossRef]

- Chabas, D.; Strober, J.; Waubant, E. Pediatric multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008, 8(5), 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavčič, A.; Hofmann, W.E. Seizures in Multiple Sclerosis are, above all, a Matter of Brain Viability. SciBase Neurol. 2024, 2(1): 1011. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lapiscina, E.H.; Ayuso, T.; Lacruz, F.; Gurtubay, I.G.; Soriano, G.; Otano, M.; Bujanda, M.; Bacaicoa, M.C. Corticojuxtacortical involvement increases risk of epileptic seizures in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2013, 128, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, M.; Grossi, P.; Favaretto, A.; Romualdi, C.; Atzori, M.; Rinaldi, F.; Perini, P.; Saladini, M.; Gallo, P. Cortical pathology in multiple sclerosis patients with epilepsy: A 3 year longitudinal study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2011, 83, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe-San-Martín, R.; Ciampi-Díaz, E.; Suarez-Hernández, F.; et al. Prevalence of epilepsy in a cohort of patients with multiple sclerosis. Seizure 2014, 23, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, J.J.; Barkhof, F. Grey matter pathology in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7(9), 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradl, M.; Lassmann, H. Progressive multiple sclerosis. Semin Immunopathol. 2009, 31(4), 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, S.; Wu, A.S.; Matheson, E.; Vyas, I.; Vyas, M.V. Association between multiple sclerosis and epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023, 104421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasa, R.; Barcutean, L.; Mosora, O.; Manu, D. Reviewing the Significance of Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption in Multiple Scle-rosis Pathology and Treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22(16): 8370. [CrossRef]

- Mahamud, Z.; Burman, J.; Zelano, J. Risk of epilepsy after a single seizure in multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2018, 25(6), 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Kim, D.W. Focal Cortical Dysplasia and Epilepsy Surgery. J. Epilepsy Res. 2013, 3, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devinsky, O.; Vezzani, A.; O’Brien, T.J.; Jette, N.; Scheffer, I.E.; de Curtis, M.; Perucca, P. Epilepsy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, E.; French, J.; Scheffer, I.E.; Bogacz, A.; Alsaadi, T.; Sperling, M.R.; Abdulla, F.; Zuberi, S.M.; Trinka, E.; Specchio, N.; Somerville, E.; Samia, P.; Riney, K.; Nabbout, R.; Jain, S.; Wilmshurst, J.M.; Auvin, S.; Wiebe, S.; Perucca, E.; Moshé, S.L.; Tinuper, P.; Wirrell, E.C. ILAE definition of the Idiopathic Generalized Epilepsy Syndromes: Position statement by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions. Epilepsia 2022, 63(6), 1475–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riney, K.; Bogacz, A.; Somerville, E.; Hirsch, E.; Nabbout, R.; Scheffer, I.E.; Zuberi, S.M.; Alsaadi, T.; Jain, S.; French, J.; Specchio, N.; Trinka, E.; Wiebe, S.; Auvin, S.; Cabral-Lim, L.; Naidoo, A.; Perucca, E.; Moshé, S.L.; Wirrell, E.C.; Tinuper, P. International League Against Epilepsy classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset at a variable age: position statement by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions. Epilepsia 2022, 63(6), 1443–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specchio, N.; Wirrell, E.C.; Scheffer, I.E.; Nabbout, R.; Riney, K.; Samia, P.; Guerreiro, M.; Gwer, S.; Zuberi, S.M.; Wilmshurst, J.M.; Yozawitz, E.; Pressler, R.; Hirsch, E.; Wiebe, S.; Cross, H.J.; Perucca, E.; Moshé, S.L.; Tinuper, P.; Auvin, S. International League Against Epilepsy classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset in childhood: Position paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions. Epilepsia 2022, 63(6), 1398–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirrell, E.C.; Nabbout, R.; Scheffer, I.E.; Alsaadi, T.; Bogacz, A.; French, J.A.; et al. Methodology for classification and definition of epileptic syndromes with list of syndromes: report of the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions. Epilepsia 2022, 63(6), 1333–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Mannan, O.A.; Manchoon, C.; Rossor, T.; Southin, J.C.; Tur, C.; Brownlee, W.; Byrne, S.; Chitre, M.; Coles, A.; Forsyth, R.; Kneen, R.; Mankad, K.; Ram, D.; West, S.; Wright, S.; Wassmer, E.; Lim, M.; Ciccarelli, O.; Hemingway, C.; Hacohen, Y. UK-Childhood Inflammatory Disease Network. Use of Disease-Modifying Therapies in Pediatric Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis in the United Kingdom. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2021, May, 21, 8(4):e1008. [CrossRef]

- Margoni, M.; Rinaldi, F.; Perini, P.; Gallo, P. Therapy of Pediatric-Onset Multiple Sclerosis: State of the Art, Challenges, and Opportunities. Front Neurol. 2021, May, 17;12:676095. [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Bai, H.; Liu, Z.; Meng, F.; Zhang, H.; Xu, R. Glatiramer acetate, an anti-demyelination drug, reduced rats’ epileptic seizures induced by pentylenetetrazol via protection of myelin sheath. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 49, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, A.; Baharvand, H.; Javan, M. Enhanced remyelination following lysolecithin-induced demyelination in mice under treatment with fingolimod (FTY720). Neuroscience 2015, 311, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Seizures and epilepsy characteristics and outcome.

Table 1.

Seizures and epilepsy characteristics and outcome.

| Patient nr |

Age at sz onset |

Time relation with MS onset |

Time sz onset- MS onset |

Time MS onset- sz onset |

Seizures aspect |

Seizures duration |

Seizures frequency |

Epilepsy diagnosis |

AED treatment |

Seizures control |

Personal & family history |

| P1 |

9y 7mo |

after |

NA |

9mo |

Left Focal Motor SE, impaired awareness at the end |

3-4h |

Only 1 SE, from awake |

No |

LEV 6mo |

Yes, ~7y, no AED in present |

Neg |

| P2 |

4y 6mo |

before |

5y8mo |

NA |

Type 1: Focal secondary generalized (head+eyes right deviation, oral automatism, generalized hypertonia+/-clonic movements,

Type 2: myoclonic-atonic

Type 3: absence sz +/- mild head to R/L; rare GTC or Focal secondary generalized |

Type 1

<1’

Type 2

1-2”

Type 3

5-10” absence sz; 1-5’ GTC |

Type 1

3/day, daily, awake & sleep

Type 2

5-10/day, daily, awake

Type 3

3-10/day, every

1-4 days, awake; GTC/focal 2-3/year |

Yes, non-syndromic, probable genetic-autoimmune |

Type 1

VPA, then *ACTH cure added

Type 2

VPA+CNZ, then new *ACTH cure

Type 3

+CBZ 20 mg/bw/day,

+LEV, - CBZ |

Type 1

Yes, after ACTH for 1y

Type 2

Yes, after ACTH for 3y

Type 3

No, only decreased nr 2-4 sz/day

VPA+CNZ+LEV in present |

6 simple FS, between 2-4y, 3/year; mild cognitive decline; some GTC/focal sz are non-epileptic |

| P3 |

10y 1mo |

before |

6y5mo |

NA |

Type 1:

Described as generalized,

Type 2: focal+/- secondary generalized

(tinnitus/diplopia, headache, left mouth deviation, L limbs dystonic posture, +/-generalized hypertonia & clonic movements, headache+/- vomiting after sz) |

Type 1

1/5-6 mo, from awake

Type 2

1/1-2 mo, majority from awake |

Type 1

1/5-6 mo, from awake

Type 2

1/1-2 mo, majority from awake |

Yes, non-syndromic, probable genetic-autoimmune |

Type 1:

VPA

Type 2

+ LEV

+ CBZ,

+ LTG, - CBZ |

No, sz freq stable in the last 3y

**LEV+VPA+

LTG+CBZ in present |

1 parent with epilepsy (adolescence form);

2 simple FS between 1-2y |

| P4 |

13y 1mo |

before |

1y8mo |

NA |

GTC sz |

1-2’ |

2 GTC sz, 2y appart, from awake |

Yes, GIEs (JME vs GTCA) |

LEV |

Yes, 1y, LEV in present |

Neg |

| P5 |

6y 5mo |

before |

4y9mo |

NA |

Focal motor: speech impairment, hypersalivation, R facio-brachial clonic movements, NO LOC |

<1’ |

2 focal sz, 2 mo appart, before sleep |

Yes, SeLECTS |

VPA 2.5y |

Yes, ~12y, no AED in present |

1 parent with MS (adult onset) |

| P6 |

15y 3mo |

after |

NA |

2wks |

Focal +/- secondary generalized

1st: nausea, dizziness, R head deviation, RUL hypertonia+clonic movements, no LOC, 5 min aphasia

2nd: nausea, L head deviation, generalized hypertonia & clonic movements, left hemibody transient paresis |

<1’, 1 from asleep, 1 awake |

2 sz, 4 days appart |

Yes, non-syndromic, probable autoimmune |

LEV 2y |

Yes, ~3y, no AED in present |

Neg |

Table 2.

Epilepsy in POMS as risk factor for higher last EDSS score 1.

Table 2.

Epilepsy in POMS as risk factor for higher last EDSS score 1.

| Chi-Squared Tests |

Value |

df |

p |

| Χ² |

7.536 |

1 |

0.006 |

| Χ² continuity correction |

5.003 |

1 |

0.025 |

| N |

120 |

|

|

Table 3.

Epilepsy in POMS as risk factor for higher last EDSS score 2.

Table 3.

Epilepsy in POMS as risk factor for higher last EDSS score 2.

| Log Odds Ratio |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

95% Confidence Intervals |

|

| |

Log Odds Ratio |

|

Upper |

p |

| Odds ratio |

2.124 |

0.364 |

3.884 |

|

Fisher’s

exact test |

2.099 |

0.088 |

4.560 |

0.020 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).