Submitted:

06 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Culture and Vaccine Preparation

2.1.1. Electron Beam (eBeam) Vaccine

2.1.2. Formalin-Inactivated (FK) Vaccine

2.1.3. Combination (F+E) Vaccine

2.2. Confirmation of Bacterial Inactivation, Membrane Integrity and Viability

2.2.1. Bacterial Inactivation

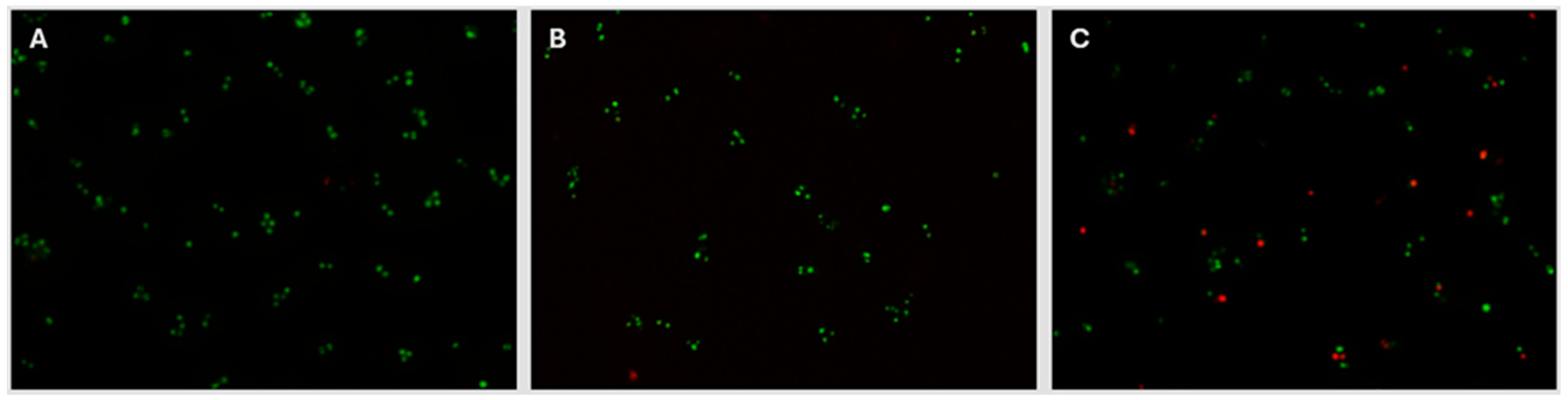

2.2.2. Bacterial Membrane Integrity

2.2.3. Bacterial Cell Viability

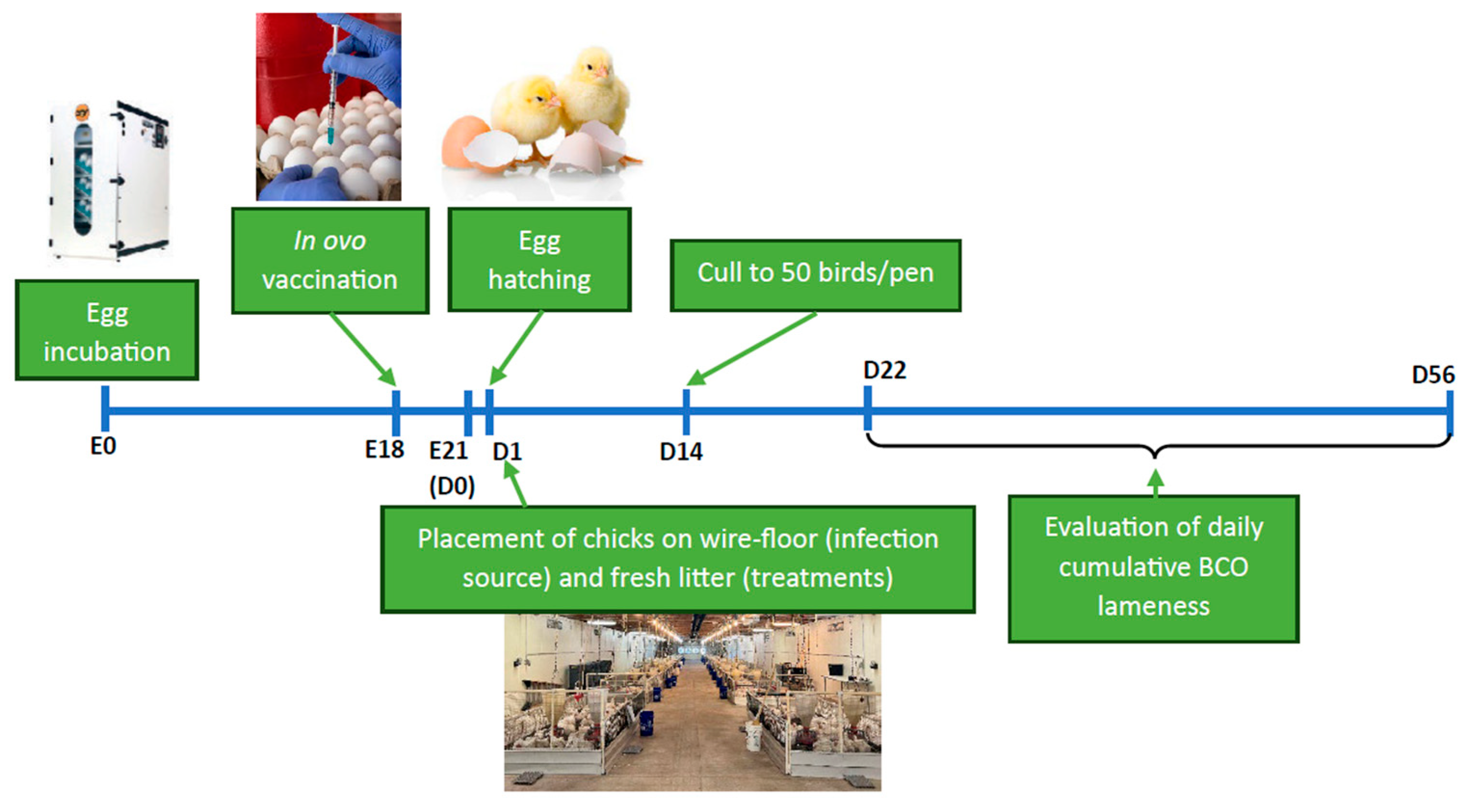

2.3. Broiler Chicken Vaccination Trial

2.3.1. Egg Placement and in Ovo Vaccination

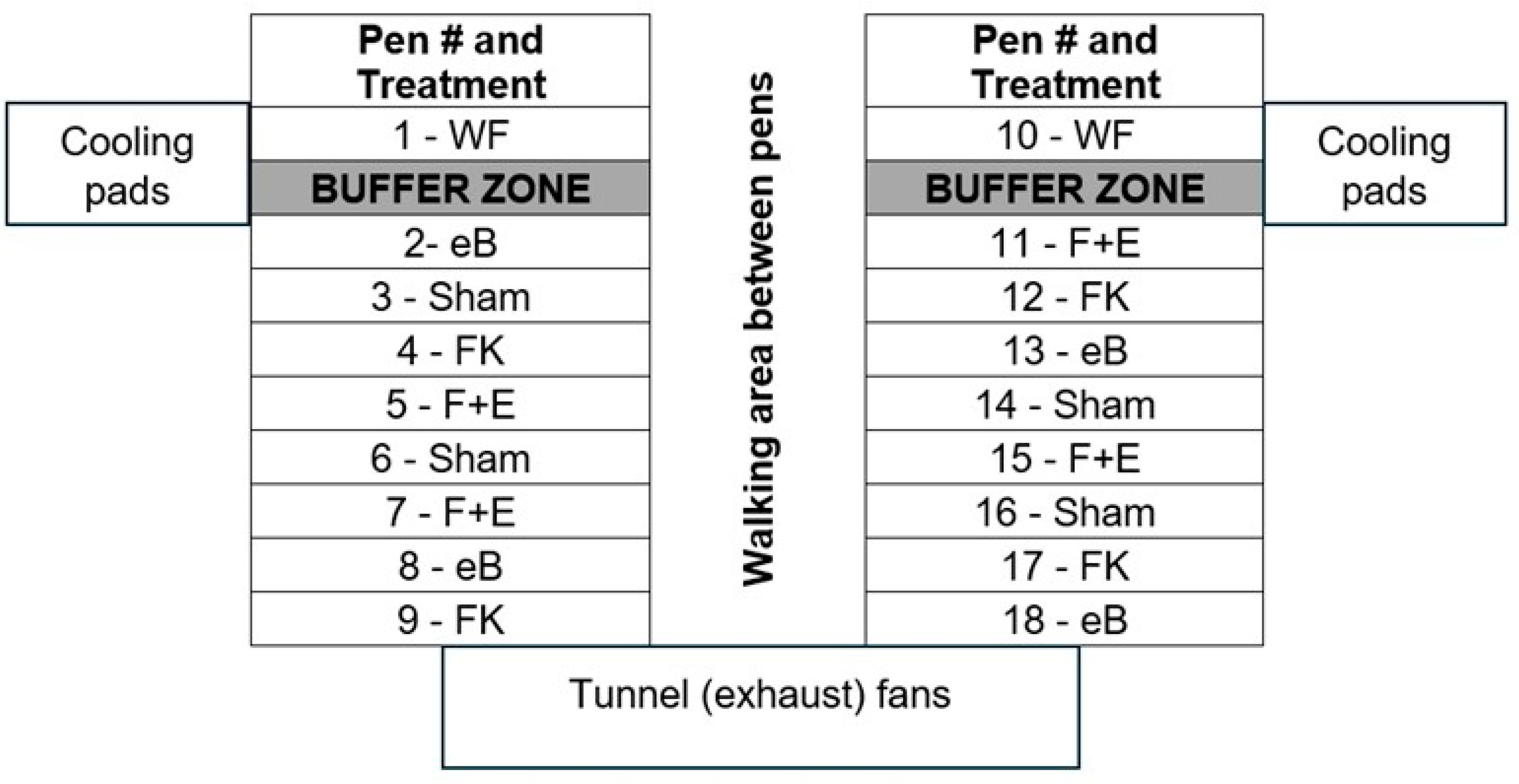

| Treatment | Flooring | Vaccine | Number of pens allocated |

|---|---|---|---|

| WF - Infection source1 | Wire | sham | 2 |

| eB - eBeam group2 | Litter | eBeam-inactivated | 4 |

| FK - Formalin group3 | Litter | formalin-inactivated | 4 |

| F+E - Combination group4 | Litter | eBeam + formalin | 4 |

| Sham - Control group5 | Litter | sham | 4 |

2.3.2. Live Bird Study and Sampling

2.4. Sample Processing

2.4.1. Bacterial Species Identification from BCO Lesions

2.4.2. Analysis and Comparison of Antibody (IgM, IgY, and IgA) Profiles

2.4.3. Flow Cytometry

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

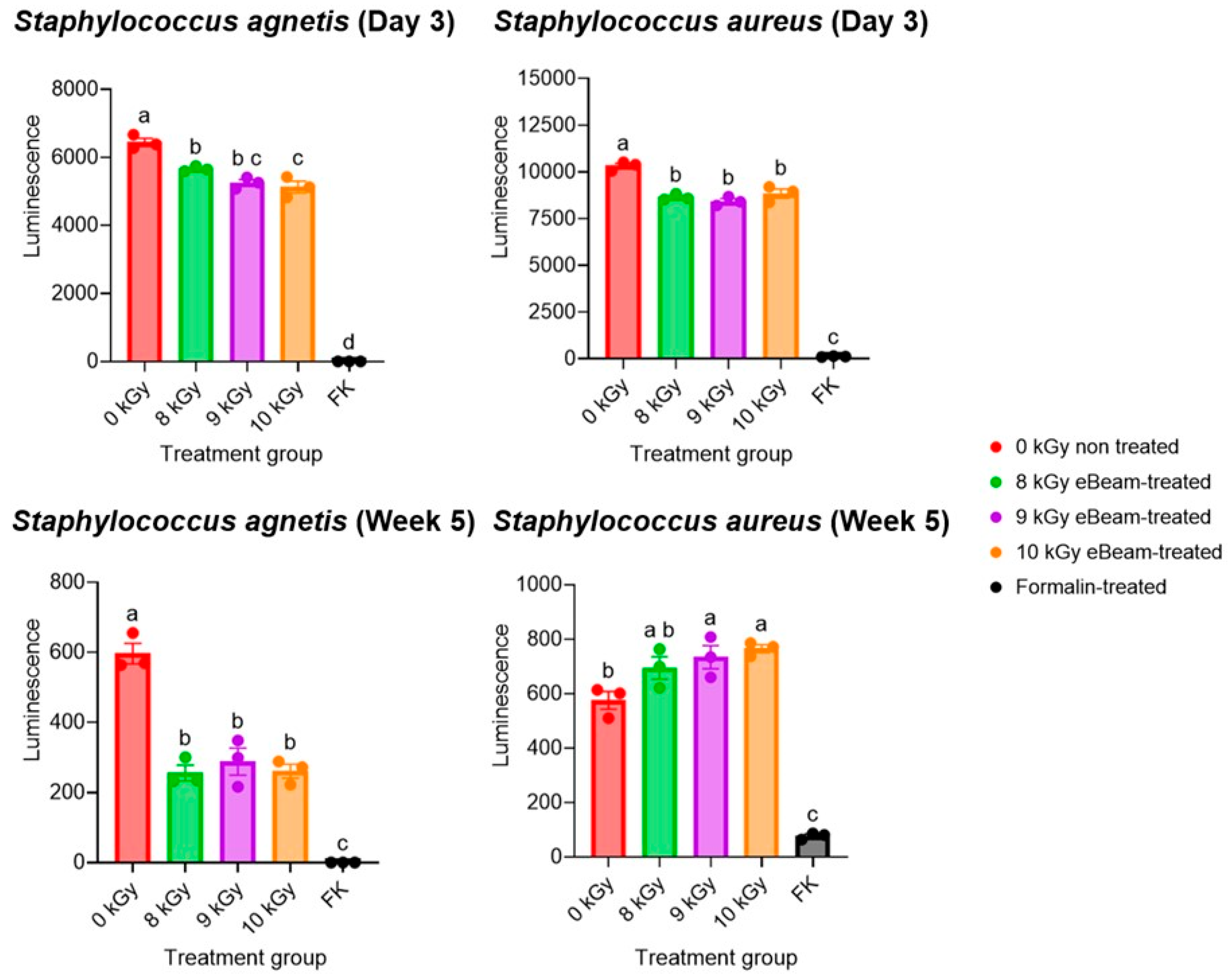

3.1. eBeam-Treated Staphylococcus Cells Were Inactivated Entirely, While Retaining Their Membrane Integrity and Higher Viability than Formalin-Treated Staphylococcus

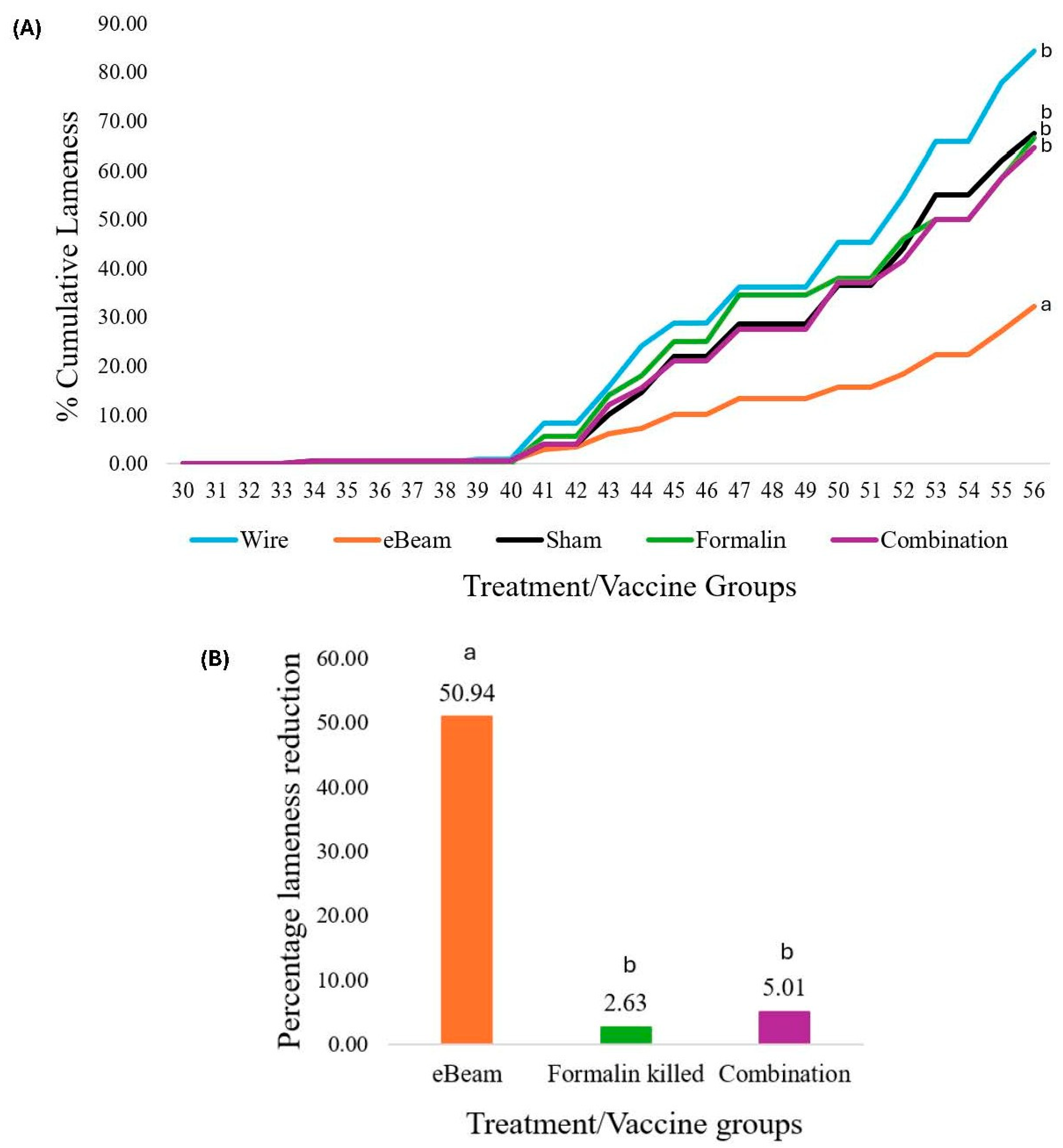

3.2. eBeam-Inactivated Staphylococcus Vaccine Significantly Decreased Lameness Compared to the Other Treatment Groups

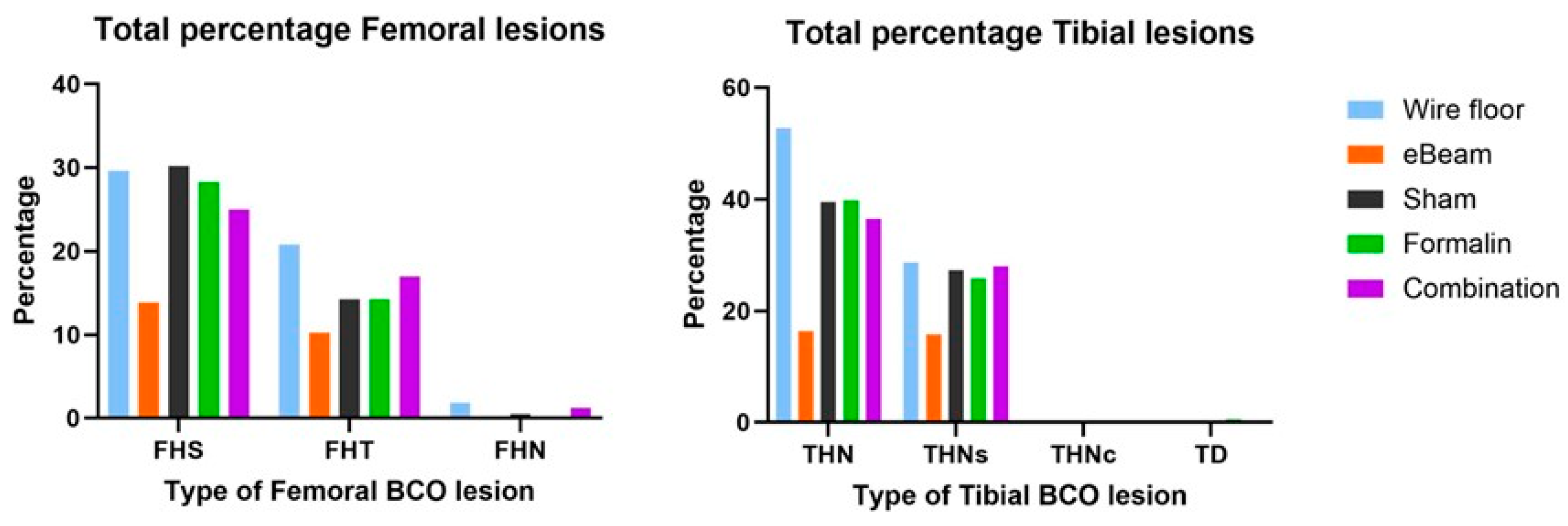

3.3. Staphylococcus Was Absent in the BCO Lesions of Birds Vaccinated with the eBeam-Treated Staphylococcus Vaccine

3.4. Birds of the eBeam and Combination Vaccine Groups Had Higher Mucosal IgA Levels at D16 Compared to Other Groups, Suggesting Early Protection

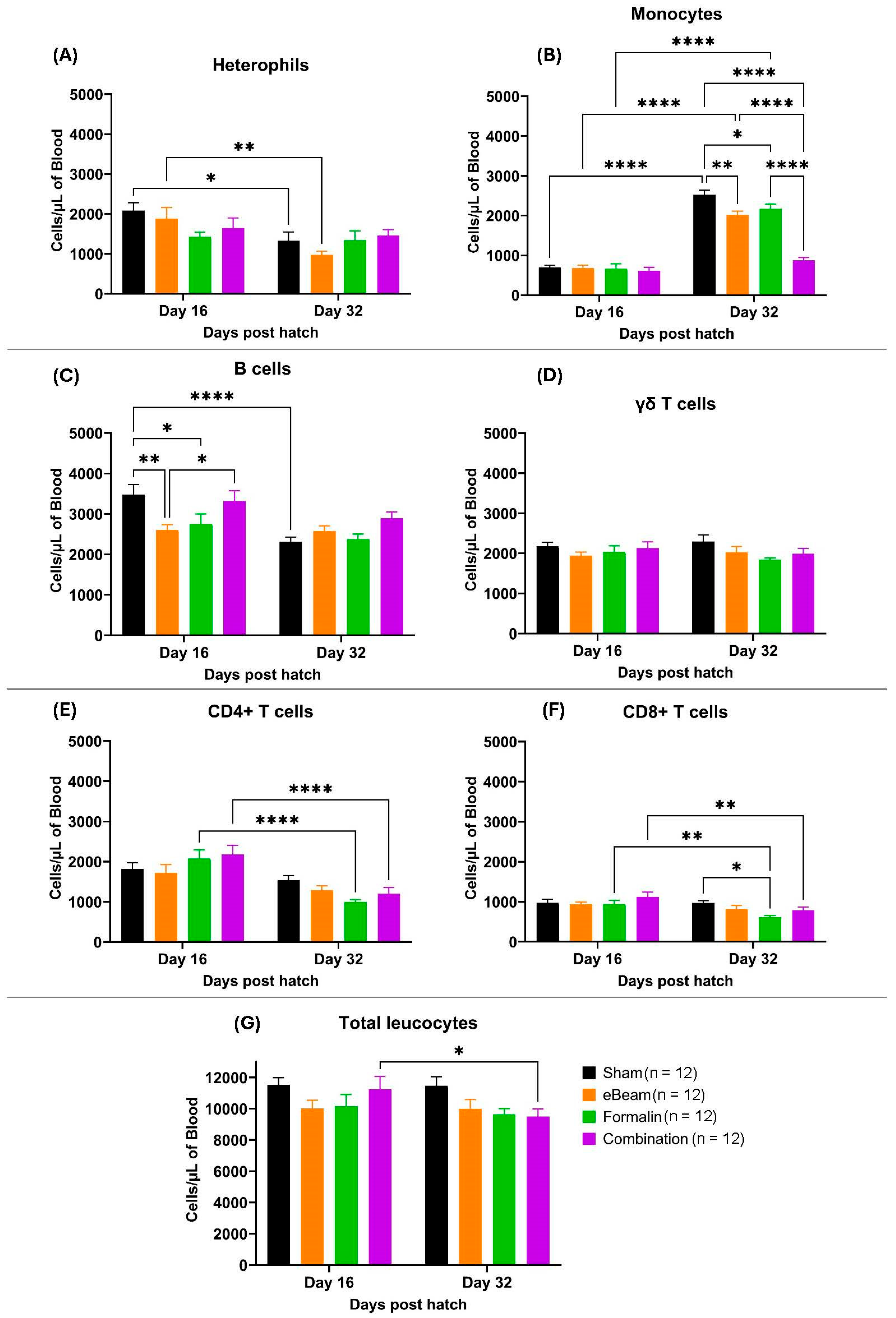

3.5. Leucocyte Populations Showed Diverse Trends of Concentration Changes Between Treatment Groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Which are the world’s 10 largest chicken companies? https://www.wattagnet.com/broilers-turkeys/broilers/article/15660706/which-are-the-worlds-10-largest-chicken-companies (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- National Chicken Council. Top Broiler Producing States https://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/industry/broiler-industry-today/ (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Wideman, R.F. Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis and Lameness in Broilers: A Review. Poult Sci 2016, 95, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, P.B.; Barger, K.; Siewerdt, F. Limb Health in Broiler Breeding: History Using Genetics to Improve Welfare. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 2019, 28, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorp, B.H. Skeletal Disorders in the Fowl: A Review. Avian Pathology 1994, 23, 203–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granquist, E.G.; Vasdal, G.; De Jong, I.C.; Moe, R.O. Lameness and Its Relationship with Health and Production Measures in Broiler Chickens. Animal 2019, 13, 2365–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szafraniec, G.M.; Szeleszczuk, P.; Dolka, B. Review on Skeletal Disorders Caused by Staphylococcus Spp. in Poultry. Veterinary Quarterly 2022, 42, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamee, P.T.; Smyth, J.A. Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis ('femoral Head Necrosis’) of Broiler Chickens: A Review. Avian Pathology 2000, 29, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairn, M.E.; Watson, A.R.A. Leg Weakness of Poultry—A Clinical and Pathological Characterisation. Aust Vet J 1972, 48, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wideman Jr, R.F.; Prisby, R.D. Bone Circulatory Disturbances in the Development of Spontaneous Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis: A Translational Model for the Pathogenesis of Femoral Head Necrosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2013, 3, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rubaye, A.A.K.; Couger, M.B.; Ojha, S.; Pummill, J.F.; Koon, J.A.; Wideman Jr, R.F.; Rhoads, D.D. Genome Analysis of Staphylococcus Agnetis, an Agent of Lameness in Broiler Chickens. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0143336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramser, A.; Greene, E.; Alrubaye, A.A.K.; Wideman, R.; Dridi, S. Role of Autophagy Machinery Dysregulation in Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis (BCO): AUTOPHAGY & BROILER LAMENESS. Poult Sci 2022, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrubaye, A.A.K.; Ekesi, N.S.; Hasan, A.; Elkins, E.; Ojha, S.; Zaki, S.; Dridi, S.; Wideman, R.F.; Rebollo, M.A.; Rhoads, D.D. Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis in Broilers: Further Defining Lameness-Inducing Models with Wire or Litter Flooring to Evaluate Protection with Organic Trace Minerals. Poult Sci 2020, 99, 5422–5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junior, A.M.B.; Fernandes, N.L.M.; Snak, A.; Fireman, A.; Horn, D.; Fernandes, J.I.M. Arginine and Manganese Supplementation on the Immune Competence of Broilers Immune Stimulated with Vaccine against Salmonella Enteritidis. Poult Sci 2019, 98, 2160–2168. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, M.T. Nutritional Modulation of Immune Function in Broilers. Poult Sci 2004, 83, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKnight, L.L.; Page, G.; Han, Y. Effect of Replacing In-Feed Antibiotics with Synergistic Organic Acids, with or without Trace Mineral and/or Water Acidification, on Growth Performance and Health of Broiler Chickens under a Clostridium Perfringens Type A Challenge. Avian Dis 2020, 64, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wideman, R.F.; Al-Rubaye, A.; Kwon, Y.M.; Blankenship, J.; Lester, H.; Mitchell, K.N.; Pevzner, I.Y.; Lohrmann, T.; Schleifer, J. Prophylactic Administration of a Combined Prebiotic and Probiotic, or Therapeutic Administration of Enrofloxacin, to Reduce the Incidence of Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis in Broilers. Poult Sci 2015, 94, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wideman, R.F.; Hamal, K.R.; Stark, J.M.; Blankenship, J.; Lester, H.; Mitchell, K.N.; Lorenzoni, G.; Pevzner, I. A Wire-Flooring Model for Inducing Lameness in Broilers: Evaluation of Probiotics as a Prophylactic Treatment. Poult Sci 2012, 91, 870–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesudhasan, P.R.; Bhatia, S.S.; Sivakumar, K.K.; Praveen, C.; Genovese, K.J.; He, H.L.; Droleskey, R.; McReynolds, J.L.; Byrd, J.A.; Swaggerty, C.L. Controlling the Colonization of Clostridium Perfringens in Broiler Chickens by an Electron-Beam-Killed Vaccine. Animals 2021, 11, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.R.; Parreira, V.R.; Kulkarni, R.R.; Prescott, J.F. Live Attenuated Vaccine-Based Control of Necrotic Enteritis of Broiler Chickens. Vet Microbiol 2006, 113, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnayanti, A.; Do, A.D.T.; Alharbi, K.; Alrubaye, A. Inducing Experimental Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis Lameness in Broiler Chickens Using Aerosol Transmission Model. Poult Sci 2024, 103, 103460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnayanti, A.; Hasan, A.; Alharbi, K.; Hassan, I.; Bottje, W.; Rochell, S.J.; Rebollo, M.A.; Kidd, M.T.; Alrubaye, A.A.K. Assessing the Impact of Spirulina Platensis and Organic Trace Minerals on the Incidence of Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis Lameness in Broilers Using an Aerosol Transmission Model. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 2024, 100426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnayanti, A.; Alharbi, K.; Do, A.D.T.; Al-Mitib, L.; Bühler, K.; Van der Klis, J.D.; Gonzalez, J.; Kidd, M.T.; Alrubaye, A.A.K. Early 1, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3-Glycosides Supplementation: An Efficient Feeding Strategy against Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis Lameness in Broilers Assessed by Using an Aerosol Transmission Model. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 2024, 33, 100440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekesi, N.S. Examining Pathogenesis and Preventatives in Spontaneous and Staphylococcus-Induced Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis in Broilers; University of Arkansas, 2020.

- Wijesurendra, D.S.; Chamings, A.N.; Bushell, R.N.; Rourke, D.O.; Stevenson, M.; Marenda, M.S.; Noormohammadi, A.H.; Stent, A. Pathological and Microbiological Investigations into Cases of Bacterial Chondronecrosis and Osteomyelitis in Broiler Poultry. Avian pathology 2017, 46, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choppa, V.S.R.; Kim, W.K. A Review on Pathophysiology, and Molecular Mechanisms of Bacterial Chondronecrosis and Osteomyelitis in Commercial Broilers. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferver, A.; Dridi, S. Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis (BCO) in Modern Broilers: Impacts, Mechanisms, and Perspectives. CABI Reviews, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, P.K.; Wilkinson, B.J.; Kim, Y.; Schmeling, D.; Douglas, S.D.; Quie, P.G.; Verhoef, J. The Key Role of Peptidoglycan in the Opsonization of Staphylococcus Aureus. J Clin Invest 1978, 61, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.L. Vaccination against Experimental Staphylococcal Mastitis in Dairy Heifers. Res Vet Sci 1992, 53, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinefield, H.R.; Black, S. Prevention of Staphylococcus Aureus Infections: Advances in Vaccine Development. Expert Rev Vaccines 2005, 4, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, J.F.; MacInnes, J.I.; Van Immerseel, F.; Boyce, J.D.; Rycroft, A.N.; Vázquez-Boland, J.A. Pathogenesis of Bacterial Infections in Animals; Wiley Online Library, 2022.

- Walker, R.I. Considerations for Development of Whole Cell Bacterial Vaccines to Prevent Diarrheal Diseases in Children in Developing Countries. Vaccine 2005, 23, 3369–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterloh, A. Vaccination against Bacterial Infections: Challenges, Progress, and New Approaches with a Focus on Intracellular Bacteria. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R.W.; Rappuoli, R.; Ahmed, S. Technologies for Making New Vaccines. In Vaccines; Elsevier, 2013; pp 1182–1199.

- Strugnell, R.; Zepp, F.; Cunningham, A.; Tantawichien, T. Vaccine Antigens. Perspect Vaccinol 2011, 1, 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, V.; Denizer, G.; Friedland, L.R.; Krishnan, J.; Shapiro, M. Understanding Modern-Day Vaccines: What You Need to Know. Ann Med 2018, 50, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesudhasan, P.R.; McReynolds, J.L.; Byrd, A.J.; He, H.; Genovese, K.J.; Droleskey, R.; Swaggerty, C.L.; Kogut, M.H.; Duke, S.; Nisbet, D.J. Electron-Beam–Inactivated Vaccine against Salmonella Enteritidis Colonization in Molting Hens. Avian Dis 2015, 59, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.S.; Pillai, S.D. Ionizing Radiation Technologies for Vaccine Development-A Mini Review. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, R.; Pillai, S.D.; Alrubaye, A.; Jesudhasan, P. Leveraging Electron Beam (EBeam) Technology for Advancing the Development of Inactivated Vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 2025, 13, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hieke, A.-S. C.; Pillai, S.D. Escherichia Coli Cells Exposed to Lethal Doses of Electron Beam Irradiation Retain Their Ability to Propagate Bacteriophages and Are Metabolically Active. Front Microbiol 2018, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praveen, C. Electron Beam as a next Generation Vaccine Platform: Microbiological and Immunological Characterization of an Electron Beam Based Vaccine against Salmonella Typhimurium; Texas A&M University, 2014.

- Praveen, C.; Bhatia, S.S.; Alaniz, R.C.; Droleskey, R.E.; Cohen, N.D.; Jesudhasan, P.R.; Pillai, S.D. Assessment of Microbiological Correlates and Immunostimulatory Potential of Electron Beam Inactivated Metabolically Active yet Non Culturable (MAyNC) Salmonella Typhimurium. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0243417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Wang, L.; Lu, W.; Li, S.; Xu, D.; Fu, Y.V. Inactivation of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus with Electron Beam Irradiation under Cold Chain Conditions. Environ Technol Innov 2022, 27, 102715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahergorabi, R.; Matak, K.E.; Jaczynski, J. Application of Electron Beam to Inactivate Salmonella in Food: Recent Developments. Food Research International 2012, 45, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbaghi, A.; Miri, S.M.; Keshavarz, M.; Zargar, M.; Ghaemi, A. Inactivation Methods for Whole Influenza Vaccine Production. Rev Med Virol 2019, 29, e2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.B. Introduction to Food Irradiation. Electronic irradiation of foods: an introduction to the technology, 2005; 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Assumpcao, A.L.F. V.; Arsi, K.; Asnayanti, A.; Alharbi, K.S.; Do, A.D.T.; Read, Q.D.; Perera, R.; Shwani, A.; Hasan, A.; Pillai, S.D. Electron-Beam-Killed Staphylococcus Vaccine Reduced Lameness in Broiler Chickens. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.Y.C.; Davis, J.S.; Eichenberger, E.; Holland, T.L.; Fowler Jr, V.G. Staphylococcus Aureus Infections: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Management. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015, 28, 603–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El Tawab, A.A.; El-Hofy, F.I.; Maarouf, A.A.; El-Said, A.A. Bacteriological Studies on Some Food Borne Bacteria Isolated from Chicken Meat and Meat Products in Kaliobia Governorate. Benha Vet Med J 2015, 29, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, R.W.; Wu, M.; Turbyfill, K.R.; Clarkson, K.; Tai, B.; Bourgeois, A.L.; Van De Verg, L.L.; Walker, R.I.; Oaks, E.V. Development and Preclinical Evaluation of a Trivalent, Formalin-Inactivated Shigella Whole-Cell Vaccine. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology 2014, 21, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. BAM R11: Butterfield’s Phosphate-Buffered Dilution Water https://www.fda.gov/food/laboratory-methods-food/bam-r11-butterfields-phosphate-buffered-dilution-water (accessed Jun 25, 2024).

- Al-Rubaye, A.A.K.; Ekesi, N.S.; Zaki, S.; Emami, N.K.; Wideman, R.F.; Rhoads, D.D. Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis in Broilers: Further Defining a Bacterial Challenge Model Using the Wire Flooring Model. Poult Sci 2017, 96, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.W.; Jorgensen, E.M. ApE, a Plasmid Editor: A Freely Available DNA Manipulation and Visualization Program. Frontiers in Bioinformatics 2022, 2, 818619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seliger, C.; Schaerer, B.; Kohn, M.; Pendl, H.; Weigend, S.; Kaspers, B.; Härtle, S. A Rapid High-Precision Flow Cytometry Based Technique for Total White Blood Cell Counting in Chickens. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2012, 145, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, K.; Assumpcao, A.L.F. V.; Arsi, K.; Erf, G.F.; Donoghue, A.; Jesudhasan, P.R.R. Effect of Salmonella Typhimurium Colonization on Microbiota Maturation and Blood Leukocyte Populations in Broiler Chickens. Animals 2022, 12, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gan, H.; Hawkins, S.; Eckelkamp, L.; Prado, M.; Burns, R.; Purswell, J.; Tabler, T. Modeling Gait Score of Broiler Chicken via Production and Behavioral Data. animal 2023, 17, 100692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekesi, N.S.; Dolka, B.; Alrubaye, A.A.K.; Rhoads, D.D. Analysis of Genomes of Bacterial Isolates from Lameness Outbreaks in Broilers. Poult Sci 2021, 100, 101148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwani, A.; Adkins, P.R.F.; Ekesi, N.S.; Alrubaye, A.; Calcutt, M.J.; Middleton, J.R.; Rhoads, D.D. Whole-Genome Comparisons of Staphylococcus Agnetis Isolates from Cattle and Chickens. Appl Environ Microbiol 2020, 86, e00484–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, K.; Asnayanti, A.; Do, A.D.T.; Perera, R.; Al-Mitib, L.; Shwani, A.; Rebollo, M.A.; Kidd, M.T.; Alrubaye, A.A.K. Identifying Dietary Timing of Organic Trace Minerals to Reduce the Incidence of Osteomyelitis Lameness in Broiler Chickens Using the Aerosol Transmission Model. Animals 2024, 14, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, A.D.T.; Anthney, A.; Alharbi, K.; Asnayanti, A.; Meuter, A.; Alrubaye, A.A.K. Assessing the Impact of Spraying an Enterococcus Faecium-Based Probiotic on Day-Old Broiler Chicks at Hatch on the Incidence of Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis Lameness Using a Staphylococcus Challenge Model. Animals 2024, 14, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petry, B.; Savoldi, I.R.; Ibelli, A.M.G.; Paludo, E.; de Oliveira Peixoto, J.; Jaenisch, F.R.F.; de Córdova Cucco, D.; Ledur, M.C. New Genes Involved in the Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis in Commercial Broilers. Livest Sci 2018, 208, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, S.L.; Wideman, R.F.; Scanes, C.G.; Mauromoustakos, A.; Christensen, K.D.; Vizzier-Thaxton, Y. The Utility of Infrared Thermography for Evaluating Lameness Attributable to Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis. Poult Sci 2019, 98, 1575–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wideman Jr, R.F.; Al-Rubaye, A.; Gilley, A.; Reynolds, D.; Lester, H.; Yoho, D.; Hughes, J.M.; Pevzner, I. Susceptibility of 4 Commercial Broiler Crosses to Lameness Attributable to Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis. Poult Sci 2013, 92, 2311–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, K.; Ekesi, N.; Hasan, A.; Asnayanti, A.; Liu, J.; Murugesan, R.; Ramirez, S.; Rochell, S.; Kidd, M.T.; Alrubaye, A. Deoxynivalenol and Fumonisin Predispose Broilers to Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis Lameness. Poult Sci 2024, 103598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouveret, E.; Derouiche, R.; Rigal, A.; Lloubès, R.; Lazdunski, C.; Bénédetti, H. Peptidoglycan-Associated Lipoprotein-TolB Interaction: A Possible Key to Explaining the Formation of Contact Sites between the Inner and Outer Membranes of Escherichia Coli. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1995, 270, 11071–11077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prossnitz, E.; Nikaido, K.; Ulbrich, S.J.; Ames, G.F. Formaldehyde and Photoactivatable Cross-Linking of the Periplasmic Binding Protein to a Membrane Component of the Histidine Transport System of Salmonella Typhimurium. Journal of biological chemistry 1988, 263, 17917–17920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klockenbusch, C.; O’Hara, J.E.; Kast, J. Advancing Formaldehyde Cross-Linking towards Quantitative Proteomic Applications. Anal Bioanal Chem 2012, 404, 1057–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggers, E.J.; Waspe, C.R.; Parker, M.L.; Waldron, K.W.; Brocklehurst, T.F. Salmonella Must Be Viable in Order to Attach to the Surface of Prepared Vegetable Tissues. J Appl Microbiol 2008, 105, 1239–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Wideman Jr, R.F.; Blankenship, J.; Pevzner, I. Effects of a Well-Defined Multi-Species Probiotic Feed Additive on Lameness in Broiler Chickens [Conference Poster]. 2014.

- Chen, J.; Wedekind, K.J.; Dibner, J.J.; Richards, J.D. Effects of Nutrition and Gut Barrier Function on the Development of Osteomyelitis Complex and Other Forms of Lameness in Poultry. 2013.

- Mandal, R.K.; Jiang, T.; Al-Rubaye, A.A.; Rhoads, D.D.; Wideman, R.F.; Zhao, J.; Pevzner, I.; Kwon, Y.M. An Investigation into Blood Microbiota and Its Potential Association with Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis (BCO) in Broilers. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 25882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Mandal, R.K.; Wideman Jr, R.F.; Khatiwara, A.; Pevzner, I.; Min Kwon, Y. Molecular Survey of Bacterial Communities Associated with Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis (BCO) in Broilers. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0124403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, R.; Alharbi, K.; Hasan, A.; Asnayanti, A.; Do, A.; Shwani, A.; Murugesan, R.; Ramirez, S.; Kidd, M.; Alrubaye, A.A.K. Evaluating the Impact of the PoultryStar® Bro Probiotic on the Incidence of Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis Using the Aerosol Transmission Challenge Model. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayona, J.A.M.; Karuppannan, A.K.; Barreda, D.R. Contribution of Leukocytes to the Induction and Resolution of the Acute Inflammatory Response in Chickens. Dev Comp Immunol 2017, 74, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, C.E.; Sales, M.A.; Rochell, S.J.; Rodriguez, A.; Erf, G.F. Local and Systemic Inflammatory Responses to Lipopolysaccharide in Broilers: New Insights Using a Two-Window Approach. Poult Sci 2020, 99, 6593–6605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, A.V.; Pimenov, N.V.; Konstantinov, A.V.; Bordyugova, S.S. Immunomorphological Changes in Bird Staphylococcus. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 548, 042033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kota, R.K.; Reddy, P.N.; Sreerama, K. Application of IgY Antibodies against Staphylococcal Protein A (SpA) of Staphylococcus Aureus for Detection and Prophylactic Functions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2020, 104, 9387–9398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortei, N.K.; Odamtten, G.T.; Obodai, M.; Wiafe-Kwagyan, M. Mycofloral Profile and the Radiation Sensitivity (D10 Values) of Solar Dried and Gamma Irradiated Pleurotus Ostreatus (Jacq. Ex. Fr. ) Kummer Fruitbodies Stored in Two Different Packaging Materials. Food Sci Nutr 2018, 6, 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S.-G.; Kang, D.-H. Inactivation of Escherichia Coli O157: H7, Salmonella Typhimurium, and Listeria Monocytogenes in Ready-to-Bake Cookie Dough by Gamma and Electron Beam Irradiation. Food Microbiol 2017, 64, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Chen, Z.; Yan, W.; Wang, H.; Tian, W.; Feng, D.; Yue, L.; Qi, W.; He, X.; Kong, Q. TMT-Based Quantitative Proteomic and Scanning Electron Microscopy Reveals Biological and Morphological Changes of Staphylococcus Aureus Irradiated by Electron Beam. LWT 2023, 184, 114977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, H.; Abou ElNour, S.; Hammad, A.A.; Abouzeid, M.; Abdou, D. Comparative Effect of Gamma and Electron Beam Irradiation on Some Food Borne Pathogenic Bacteria Contaminating Meat Products. Egyptian Journal of Pure and Applied Science 2022, 60, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).