Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Cultures

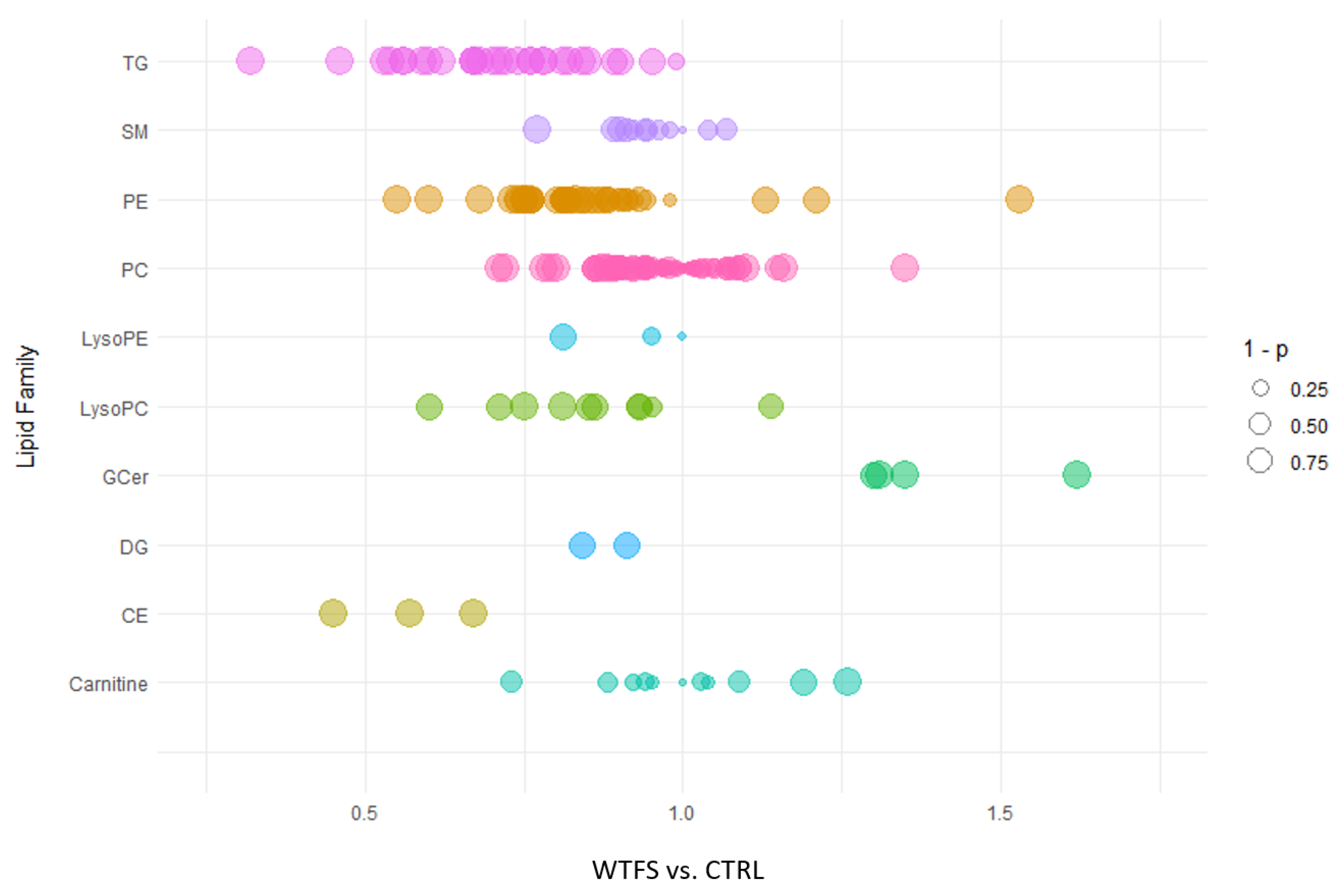

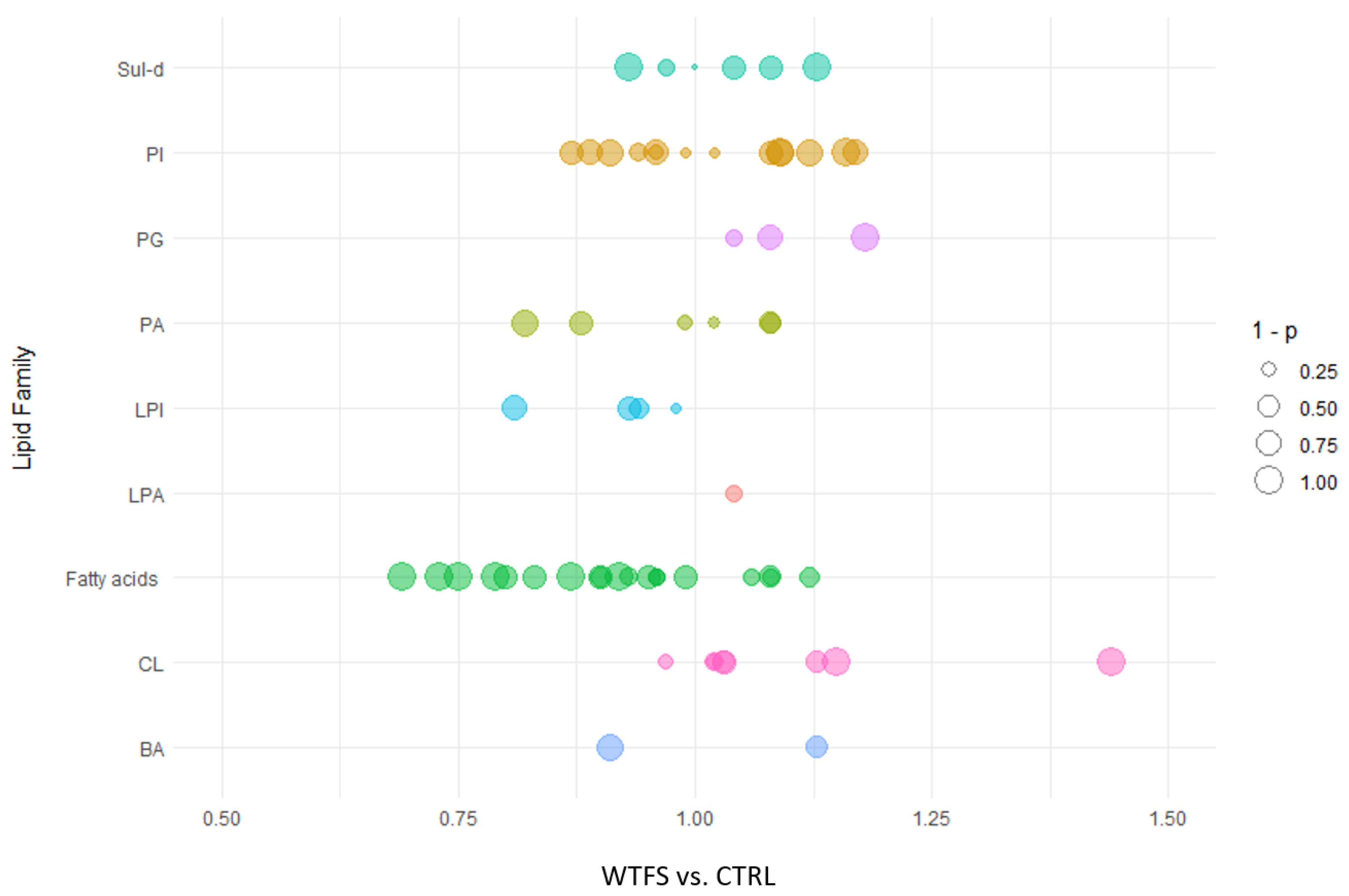

2.2. Lipidomic Analysis

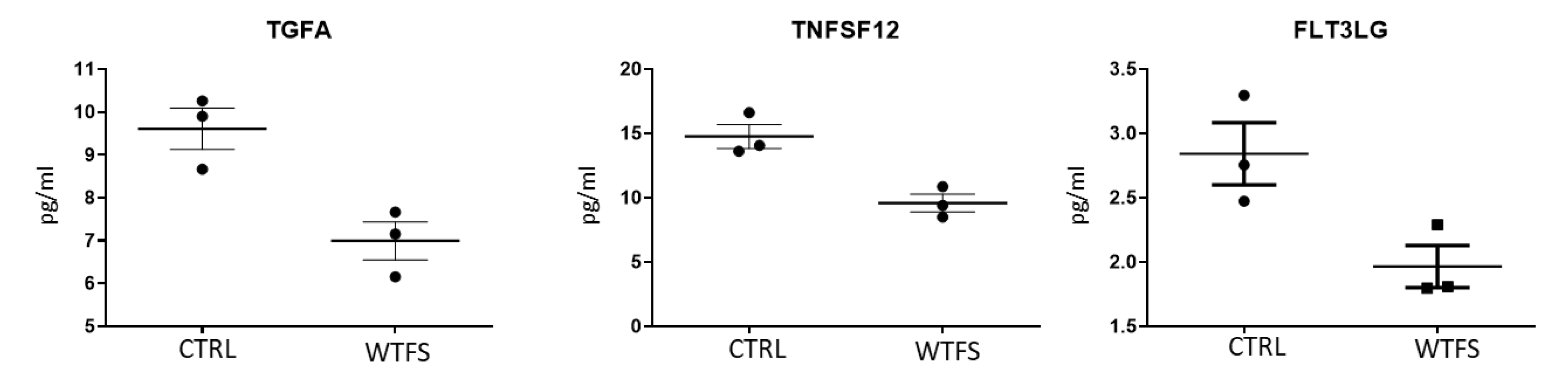

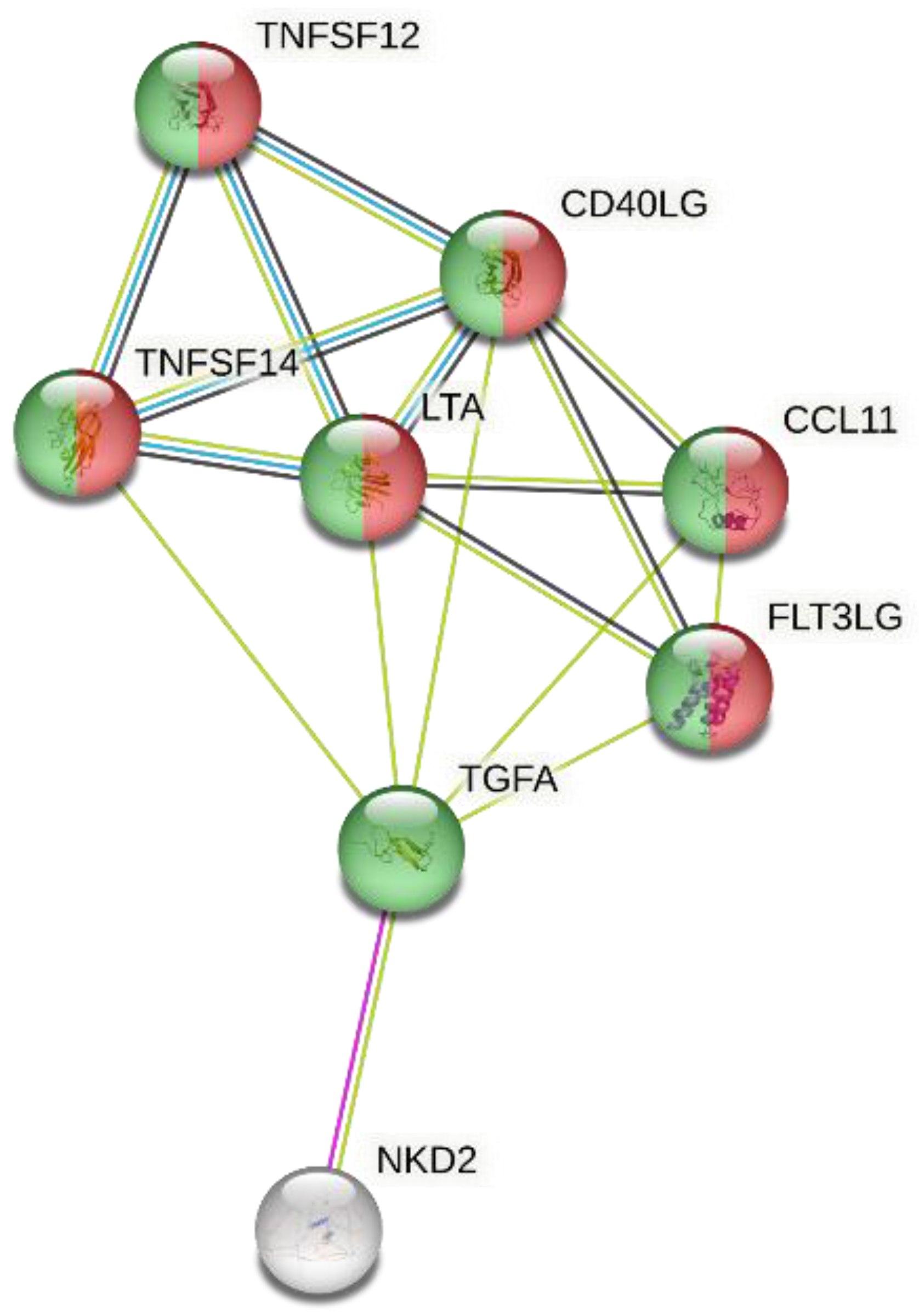

2.3. Olink Analysis

2.4. Gene Ontology Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials:

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTRL | control |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| MASLD | Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease |

| WTFS | whole tomato-based food supplement |

References

- Vahid, F.; Rahmani, D.; Hekmatdoost, A. the association between dietary antioxidant index (DAI) and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) onset; new findings from an incident case-control study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 2021, 41, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, D.; Lv, Y.; Wei, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhou, F.; Tang, M.; Mao, T.; Li, M.; et al. Inhibitory effect of blueberry polyphenolic compounds on oleic acid-induced hepatic steatosis in vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 12254–12263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, Y.; Alboraie, M.; Shiha, G. Epidemiology and diagnosis of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Hepatol. Int. 2024, 18, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L.; Zhang, P.H.; Yan, H.H. Functional foods and dietary supplements in the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1014010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EAT–Lancet 2. 0 Commissioners and contributing authors. Electronic address: fabrice@eatforum.org. EAT-Lancet Commission 2.0: securing a just transition to healthy, environmentally sustainable diets for all. Lancet. 2023, 402, 352–354. [CrossRef]

- Marquez, C.S.; Reis Lima, M.J.; Oliveira, J.; Teixeira-Lemos, E. Tomato lycopene: functional proprieties and health benefits. Int. J. Agric. Eng. 2015, 9, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhash, K.; Bose, C.; Agrawal, B.K. Effect of short-term supplementation of tomatoes on antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation in type-II diabetes. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2007, 22, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafe, M.O.; Gumede, N.M.; Nyakudya, T.T.; Chivandi, E. Lycopene: A potent antioxidant with multiple health benefits. J. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 6252426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Geng, T.; Zou, Q.; Yang, N.; Zhao, W.; Li, Y.; Tan, X.; Yuan, T.; Liu, X. ; Zhigang. Liu. Lycopene prevents lipid accumulation in hepatocytes by stimulating PPARα and improving mitochondrial function. J. Funct. Foods, 2020; 103857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mein, J.R.; Lian, F.; Wang, X.D. Biological activity of lycopene metabolites: implications for cancer prevention. Nutr Rev. 2008, 66, 667–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan Alvi, S.; Ansari, I.A.; Khan, I.; Iqbal, J.; Khan, M.S. Potential role of lycopene in targeting proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type-9 to combat hypercholesterolemia. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 108, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Concepcion, M.; Avalos, J.; Bonet, M.L.; Boronat, A.; Gomez-Gomez, L.; Hornero-Mendez, D.; Limon, M.C.; Melendez- Martinez, A.J.; Medill-Alonso, B.; Palou, A.; et al. A global perspective on carotenoids: Metabolism, biotechnology, and benefits for nutrition and health. Prog. Lipid Res. 2018, 70, 62–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.D. Lycopene metabolism and its biological significance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 1214S–1222S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Golabi, P.; Paik, J.M. : Henry, A., Van Dongen, C.; Henry, L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatol. 2023, 77, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohn, T.; Desmarchelier, C.; Dragsted, L.O.; Nielsen, C.S.; Stahl, W.; Rühl, R.; Keijer, J.; Borel, P. Host-related factors explaining interindividual variability of carotenoid bioavailability and tissue concentrations in humans. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, E.J.; Qin, J.; Krinsky, N.I.; Russell, R.M. Ingestion by men of a combined dose of beta-carotene and lycopene does not affect the absorption of beta-carotene but improves that of lycopene. J. Nutr. 1997, 127, 1833–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamanna, N.; Mahmood, N. Food processing and Maillard reaction products: effect on human health and nutrition. Int. J. Food Sci. 2015, 2015, 526762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applegate, C.; Rowles, J3rd. ; Miller, R., Wallig, M.; Clinton, S.; O’Brien, W.; Erdman, J. Dietary tomato, but not lycopene supplementation, impacts molecular outcomes of castration-resistant prostate cancer in the TRAMP model (P05-015-19). Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnewiel-Hermoni, K.; Khanin, M.; Danilenko, M.; Zango, G.; Amosi, Y.; Levy, J.; Sharoni, Y. The anti-cancer effects of carotenoids and other phytonutrients resides in their combined activity. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 572, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrier, J.F.; Breniere, T.; Sani, L.; Desmarchelier, C.; Mounien, L.; Borel, P. Effect of tomato, tomato-derived products and lycopene on metabolic inflammation: from epidemiological data to molecular mechanisms. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2025, 38, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohri, S.; Takahashi, H.; Sakai, M.; Takahashi, S.; Waki, N.; Aizawa, K.; Suganuma, H.; Ara, T.; Matsumura, Y.; Shibata, D.; et al. Wide-range screening of anti-inflammatory compounds in tomato using LC-MS and elucidating the mechanism of their functions. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0191203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, E.J.; Bowyer, C.; Tsouza, A.; Chopra, M. Tomatoes: an extensive review of the associated health impacts of tomatoes and factors that can affect their cultivation. Biology 2022, 11, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogliano, V.; Iacobelli, S.; Piantelli, M. Euro Patent 3 052 113 B1, Italian Health Ministry (registration n. 68843, 2018–2019) Available online:. Available online: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/049226079/publication/EP3052113A1?q=3052113 (accessed on November 5, 2025).

- Gholami, F.; Antonio, J.; Evans, C.; Cheraghi, K.; Rahmani, L.; Amirnezhad, F. Tomato powder is more effective than lycopene to alleviate exercise-induced lipid peroxidation in well-trained male athletes: randomized, double-blinded cross-over study. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2021, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natali, P.G.; Piantelli, M.; Minacori, M.; Eufemi, M.; Imberti, L. Improving whole tomato transformation for prostate health: benign prostate hypertrophy as an exploratory model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natali, P.G.; Piantelli, M.; Sottini, A.; Eufemi, M.; Banfi, C.; Imberti, L. A step forward in enhancing the health-promoting properties of whole tomato as a functional food to lower the impact of non-communicable diseases. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1519905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mpountouridis, A.; Tsigalou, C.; Bezirtzoglou, I.; Bezirtzoglou, E.; Stavropoulou, E. Gut microbiome in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front. Gastroenterol. 2025, 3, 1534431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.C.; Costa, C.; Roupar, D.; Silva, S.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Teixeira, J.A.; Pintado, M.E. Modulation of the gut microbiota by tomato flours obtained after conventional and ohmic heating extraction and its prebiotic properties. Foods 2023, 12, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemzer, B.V.; Al-Taher, F.; Kalita, D.; Yashin, A.Y.; Yashin, Y.I. Health-improving effects of polyphenols on the human intestinal microbiota: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aden, D.P.; Fogel, A.; Plotkin, S.; Damjanov, I.; Knowles, B.B. Controlled synthesis of HBsAg in a differentiated human liver carcinoma-derived cell line. Nature 1979, 282, 615–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, F.S.; Pimentel, L.L.; Vidigal, S.S.M.P.; Azevedo-Silva, J.; Pintado, M.E.; Rodríguez-Alcalá, L.M. Differential Lipid Accumulation on HepG2 Cells Triggered by Palmitic and Linoleic Fatty Acids Exposure. Molecules. 2023, 28, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfi, C.; Mussoni, L.; Risé, P.; Cattaneo, M.G.; Vicentini, L.; Battaini, F.; Galli, C.; Tremoli, E. Very low density lipoprotein-mediated signal transduction and plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 in cultured HepG2 cells. Circ Res. 1999, 85, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubini, E.; Minacori, M.; Paglia, G.; Macone, A.; Chichiarelli, S.; Altieri, F.; Eufemi, M. Tomato and olive bioactive compounds: A natural shield against the cellular effects induced by β-hexachlorocyclohexane-Activated Signaling Pathways. Molecules. 2021, 26, 7135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausto, N. Liver regeneration and repair: Hepatocytes, progenitor cells, and stem cells. Hepatology, 2004; 39, 1477–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudlow, J.E.; Bjorge, J.D. TGF-alpha in normal physiology. Semin. Cancer Biol. 1990, 1, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Winkles, J.A. The TWEAK-Fn14 cytokine-receptor axis: discovery, biology and therapeutic targeting. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Koenig, A.B.; Abdelatif, D.; Fazel, Y.; Henry, L.; Wymer, M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016, 64, 73-–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, L.; Paik, J.; Younossi, Z.M. Review article: the epidemiologic burden of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease across the world. Alimen. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 56, 942–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldner, D.; Lavine, J.E. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children: Unique Considerations and Challenges. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1967–1983.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobili, V.; Alisi, A.; Valenti, L.; Miele, L.; Feldstein, A.E.; Alkhouri, N. NAFLD in children: new genes, new diagnostic modalities and new drugs. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devasia, A.G.; Ramasamy, A.; Leo, C.H. Current Therapeutic Landscape for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, L.; Kirk, C.; El Gendy, K.; Gallacher, J.; Errington, L.; Mathers, J.C. Anstee, Q.M. The effectiveness and acceptability of Mediterranean diet and calorie restriction in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 1913–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydes, T.J.; Ravi, S. , Loomba, R.; Gray, M.E. Evidence-based clinical advice for nutrition and dietary weight loss strategies for the management of NAFLD and NASH. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2020, 26, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzino, S.; Sofia, M.; Mazzone, C.; Litrico, G.; Greco, L.P.; Gallo, L.; La Greca, G.; Latteri, S. Innovative treatments for obesity and NAFLD: A bibliometric study on antioxidants, herbs, phytochemicals, and natural compounds. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, K.; Lawler, T.; Mares, J. Dietary carotenoids and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease among US adults, NHANES 2003−2014. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donghia, R.; Campanella, A.; Bonfiglio, C.; Cuccaro, F.; Tatoli, R.; Giannelli, G. Protective Role of Lycopene in Subjects with Liver Disease: NUTRIHEP Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paetau, I.; Khachik, F.; Brown, E.D.; Beecher, G.R.; Kramer, T.R.; Chittams, J.; Clevidence, B.A. Chronic ingestion of lycopene-rich tomato juice or lycopene supplements significantly increases plasma concentrations of lycopene and related tomato carotenoids in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 68, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.B.; Vuong, T.; Ruckle, J.; Synal, H.A.; Schulze-König, T.; Wertz, K.; Rümbeli, R.; Liberman, R.G.; Skipper, P.L.; Tannenbaum, S.R.; et al. Lycopene bioavailability and metabolism in humans: an accelerator mass spectrometry study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens (NDA); Turck, D; Bohn, T. ; Cámara, M.; Castenmiller, J.; De Henauw, S.; Jos, Á.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; et al. Safety of yellow tomato extract as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petyaev, I.M. Lycopene Deficiency in Ageing and Cardiovascular Disease. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 321805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, A.R.; Vitale, E.; Guerretti, V.; Palumbo, G.; De Clemente, I.M.; Vitale, L.; Arena, C.; De Maio, A. Antioxidant Characterization of Six Tomato Cultivars and Derived Products Destined for Human Consumption. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023, 12, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Zhu, X.; Xie, T.; Li, W.; Xie, D.; Zhang, G.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, L. Amadori compounds (N-(1-Deoxy-D-fructos-1-yl)-amino acid): The natural transition metal ions (Cu2+, Fe2+, Zn2+) chelators formed during food processing. LWT 2024, 191, 115600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannellini, T.; Iezzi, M.; Liberatore, M.; Sabatini, F.; Iacobelli, S.; Rossi, C.; Alberti, S.; Di Ilio, C.; Vitaglione, P.; Fogliano, V.; et al. A dietary tomato supplement prevents prostate cancer in TRAMP mice. Cancer Prev. Res. 2010, 3, 1284–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzumanian, V.A.; Kiseleva, O.I.; Poverennaya, E.V. The Curious Case of the HepG2 Cell Line: 40 Years of Expertise. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S-J. ; Garcia Diaz, J.; Um, E.; Hahn, Y.S. Major roles of kupffer cells and macrophages in NAFLD development. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1150118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiering, L.; Subramanian, P.; Hammerich. L. Hepatic Stellate Cells: Dictating Outcome in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 15, 1277–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moayedfard, Z.; Sani, F.; Alizadeh, A.; Bagheri Lankarani, K.; Zarei, M.; Azarpira, N. The role of the immune system in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and potential therapeutic impacts of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, Y.; Cohen, D.E. Mechanisms of hepatic triglyceride accumulation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 48, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.E.; Ramos-Roman, M.A.; Browning, J.D.; Parks, E.J. Increased de novo lipogenesis is a distinct characteristic of individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves-Bezerra, M.; Cohen, D.E. Triglyceride Metabolism in the Liver. Compr. Physiol. 2017, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloni, L.; Di Cocco, S.; Guerrieri, F.; Nunn, A.D.G.; Piconese, S.; Salerno, D.; Testoni, B.; Pulito, C.; Mori, F.; Pallocca, M.; et al. Targeting a phospho-STAT3-miRNAs pathway improves vesicular hepatic steatosis in an in vitro and in vivo model. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Wada, T.; Febbraio, M.; He, J.; Matsubara, T.; Lee, M.J.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Xie, W. A novel role for the dioxin receptor in fatty acid metabolism and hepatic steatosis. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M.; Moteki, H.; Ogihara, M. Role of hepatocyte growth regulators in liver regeneration. Cells 2023, 12, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.Q.; Zhao, H.; Ma, A.L.; Zhou, J.Y.; Xie, S.B.; Zhang, X.Q.; Zhang, D.Z.; Xie. Q.; Zhang, G.; Shang, J. et al. Selected cytokines serve as potential biomarkers for predicting liver inflammation and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis b patients with normal to mildly elevated aminotransferases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015, 94, e2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirnitz-Parker, J.E.; Viebahn, C.S.; Jakubowski, A.; Klopcic, B.; Olynyk, J.; Yeoh, G.; Knight, B. Tumor necrosis factor–like weak inducer of apoptosis is a mitogen for liver progenitor cells. Hepatology 2010, 52, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suppli, M.P.; Rigbolt, K.T.G.; Veidal, S.S.; Heebøll, S.; Eriksen, P.L.; Demant, M.; Bagger, J.I.; Nielsen, J.C.; Oró, D.; Thrane, S.W. Hepatic transcriptome signatures in patients with varying degrees of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease compared with healthy normal-weight individuals. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2019, 316, G462–G472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhelm, A.; Shepherd, E.L.; Amatucci, A.; Munir, M.; Reynolds, G.; Humphreys, E.; Resheq, Y.; Adams, D.H.; Hübscher, S.; Burkly, L.C. Interaction of TWEAK with Fn14 leads to the progression of fibrotic liver disease by directly modulating hepatic stellate cell proliferation. J. Pathol. 2016, 239, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, P.; Dobie, R.; Wilson-Kanamori, J.R.; Dora, E.F.; Henderson, B.E.P.; Luu, N.T.; Portman, J.R.; Matchett, K.P.; Brice, M.; Marwick, J.A.; et al. Resolving the fibrotic niche of human liver cirrhosis at single-cell level. Nature 2019, 575, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.H.; Ma, D.; Wu, S.; Huang, Z.; Liang, P.; Chen, H.; Zhong, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, F.; Tang, Y.; et al. Integrative single-cell and spatial transcriptomic analyses identify a pathogenic cholangiocyte niche and TNFRSF12A as therapeutic target for biliary atresia. Hepatology 2025, 81, 1146–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Zheng, D.; Song, Y.; Pan, H.; Qiu, G.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, F. Demonstration of the impact of COVID-19 on metabolic associated fatty liver disease by bioinformatics and system biology approach. Medicine 2023, 102, e34570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronov, I.; Manolson, M.F. Editorial: Flt3 ligand-friend or foe? J. Leukoc. Biol. 2016, 99, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.H.; Aloman, C. Dendritic cells and liver fibrosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013, 1832, 998–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniello, V.; De Leo, V.; Lasalvia, M.; Hossain, M.N.; Carbone, A.; Catucci, L.; Zefferino, R.; Ingrosso, C.; Conese, M.; Di Gioia, S. Solanum lycopersicum (Tomato)-derived nanovesicles accelerate wound healing by eliciting the migration of keratinocytes and fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulcinelli, F.; Curreli, M.; Natali, P.G.; Quaresima, V.; Imberti, L.; Piantelli, M. Development of the whole tomato and olive-based food supplement enriched with anti-platelet aggregating nutrients. Nutr Health. 2023, 29, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccatonda, A.; Del Cane, L.; Marola, L.; D’Ardes, D.; Lessiani, G.; di Gregorio, N.; Ferri, C.; Cipollone, F.; Serra, C.; Santilli, F.; et al. Platelet, Antiplatelet Therapy and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Narrative Review. Life (Basel). 2024, 14, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEneny, J.; Henry, S.-L.; Woodside, J.; Moir, S.; Rudd, A.; Vaughan, N.; Thies. F. Lycopene-rich diets modulate HDL functionality and associated inflammatory markers without aecting lipoprotein size and distribution in moderately overweight, disease-free, middle-aged adults: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 954593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, J.; Sanchez, J.I.; Saldarriaga, O.A.; Solis, L.M.; Tweardy, D.J.; Maru, D.M.; Stevenson, H. L.; Beretta, L. Spatial molecular and cellular determinants of STAT3 activation in liver fibrosis progression in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. JHEP Rep. 2022, 5, 100628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pipitone, R.M.; Zito, R.; Gambino, G.; Di Maria, G. ; Javed,A.; Lupo, G.; Giglia, G.; Sardo, P.; Ferraro, G.; Rappa, F.; et al. Red and golden tomato administration improves fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis in rats by modulating HNF4α, Lepr, and GK expression. Front Nutr. 2023, 10, 1221013. [CrossRef]

- Negri, R.; Trinchese, G.; Carbone, F.; Caprio, M.G.; Stanzione, G.; di Scala, C.; Micillo, T.; Perna, F.; Tarotto, L.; Gelzo, M.; et al. Randomised Clinical Trial: Calorie Restriction Regimen with Tomato Juice Supplementation Ameliorates Oxidative Stress and Preserves a Proper Immune Surveillance Modulating Mitochondrial Bioenergetics of T-Lymphocytes in Obese Children Affected by Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, A.; Terauchi, M.; Tamura, M.; Akiyoshi, M.; Owa, Y.; Kato, K.; Kubota, T. Tomato juice intake increases resting energy expenditure and improves hypertriglyceridemia in middle-aged women: an open-label, single-arm study. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, M.; Tominaga, N.; Ishikawa-Takano, Y.; Maeda-Yamamoto, M.; Nishihira, J. Effect of 12-Week Daily Intake of the High-Lycopene Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum), A Variety Named “PR-7”, on Lipid Metabolism: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacca, M.; Kamzolas, I.; Harder, L.M.; Oakley, F.; Trautwein, C.; Hatting, M.; Ross, T.; Bernardo, B.; Oldenburger, A.; Hjuler, S.T.; et al. An unbiased ranking of murine dietary models based on their proximity to human metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 1178–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, A.; Zahrawi, F.; Mehal, W.Z. Therapeutic landscape of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2025, 24, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, R.; Morgan, E.; Yousefi, K.; Li, D.; Geary, R.; Bhanot, S.; Alkhouri, N. ; ION224-CS2 Investigators. Antisense oligonucleotide DGAT-2 inhibitor, ION224, for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (ION224-CS2): results of a 51-week, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet, 2025, 406, 821–831. [CrossRef]

- Zelber-Sagi, S.; Moore, J.B. Practical Lifestyle Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease for Busy Clinicians. Diabetes Spectr. 2024, 37, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abenavoli, L.; Procopio, A.C.; Paravati, M.R.; Costa, G.; Milić, N.; Alcaro, S.; Luzza, F. Mediterranean Diet: The Beneficial Effects of Lycopene in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaskolka Meir, A.; Rinott, E.; Tsaban, G.; Zelicha, H.; Kaplan, A.; Rosen, P.; Shelef, I.; Youngster, I.; Shalev, A.; Blüher, M.; et al. Effect of green-Mediterranean diet on intrahepatic fat: the DIRECT PLUS randomised controlled trial. Gut 2021, 70, 2085–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Caldwell, S.; Barb, D.; Kleiner, D.E.; Loomba, R. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2023, 77, 1797–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiani, A.K.; Medori, M.C.; Bonetti, G.; Aquilanti, B.; Velluti, V.; Matera, G.; Iaconelli, A.; Stuppia, L.; Connelly, S.T.; Herbst, K.L.; et al. Modern vision of the Mediterranean diet. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E36–E43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, A.; Jennings, A.; Hayhoe, R.P.G.; Awuzudike, V.E.; Welch, A.A. High variability of food and nutrient intake exists across the Mediterranean Dietary Pattern-A systematic review. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 4907–4918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leh, H.E.; Lee, L.K. Lycopene: a potent antioxidant for the amelioration of type II diabetes mellitus. Molecules 2022, 27, 2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 1388–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Jia, L.; Liu, J. Association between carotenoid intake and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease among US adults: A cross-sectional study. Medicine 2023, 102, e36658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).