Submitted:

06 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Epidemiology of Arrhythmias in Rheumatoid Arthritis

3.1. General Prevalence of Arrhythmias in Rheumatoid Arthritis

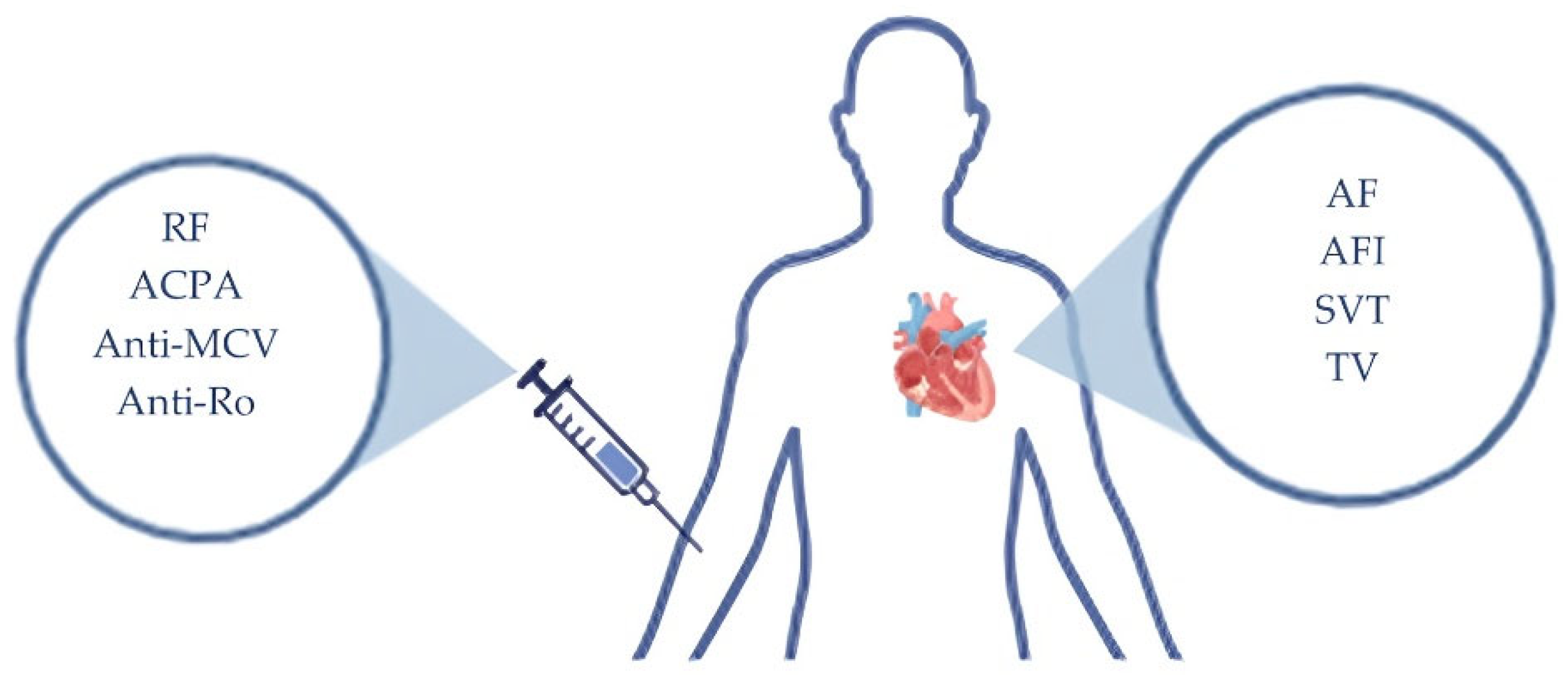

3.2. Autoantibody-Associated Arrhythmias in Rheumatoid Arthritis

4. Pathophysiology

4.1. Atrial and Ventricular Remodeling

4.2. Autonomic Nervous System

4.3. Renin Angiotensin System

4.4. Endothelial Dysfunction

4.5. Epicardial Tissue Adiposity and Inflammation

5. Effects of Antirheumatic Drugs on Cardiac Rhythm

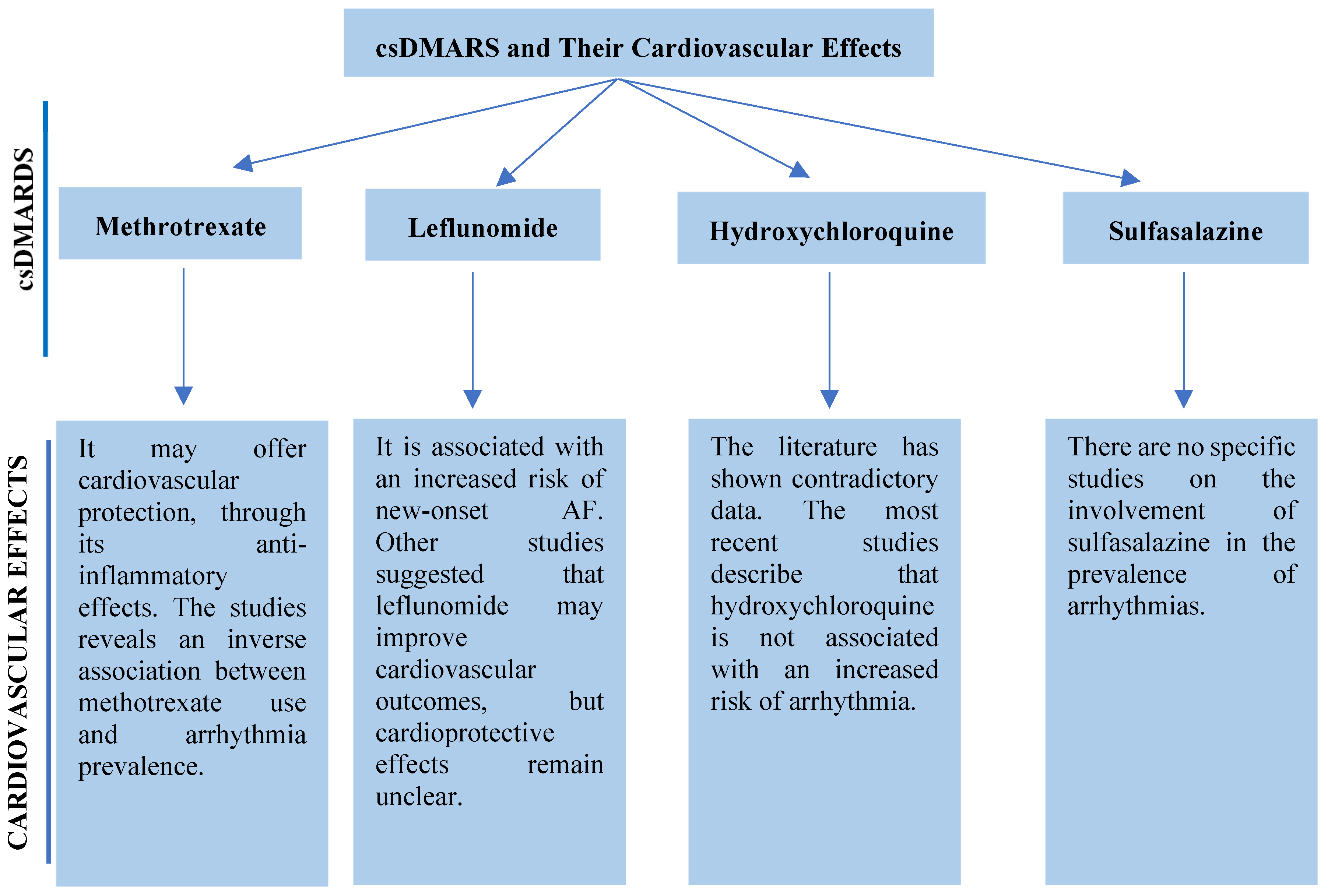

5.1. csDMARDs

5.1.1. Methotrexate

5.1.2. Leflunomide

5.1.3. Antimalarials

5.1.4. Sulfasalazine

5.2. bDMARDs and tsDMARDs

5.3. Complementary Therapies

5.3.1. Corticosteroids

5.3.2. Sinomenine and Arrhythmias

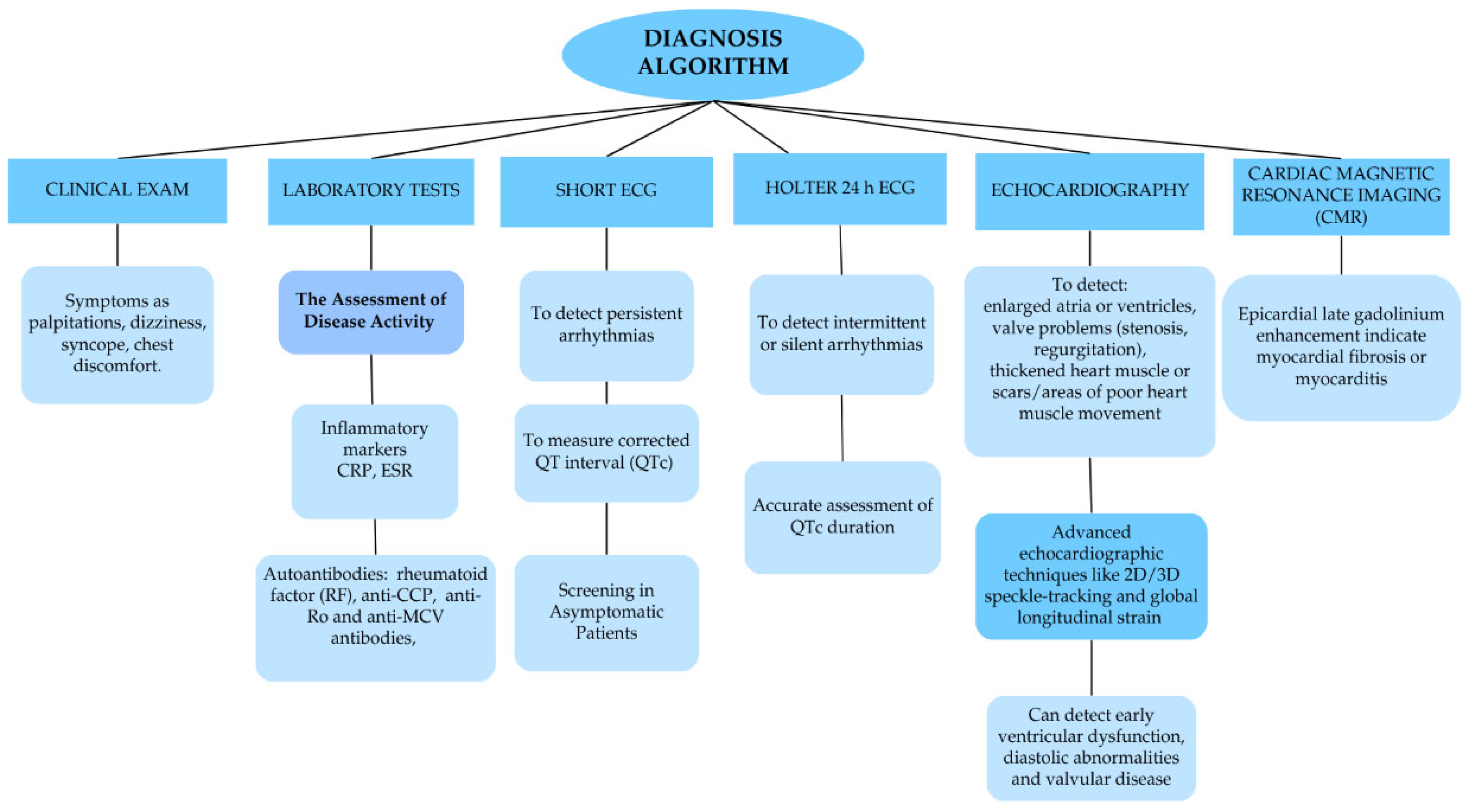

6. Diagnosis of Arrhythmias in RA

7. Management of Arrhythmias in RA

8. Future Perspectives

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| β1AR | β1-adrenergic receptor |

| ACE | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme |

| ACE 2 | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 |

| ACPA | Anti-Citrullinated Protein Antibodies |

| AF | Atrial Fibrillation |

| AFl | Atrial Flutter |

| Ang II | Angiotensin II |

| anti-MCV | Anti-Modified Citrullinated Vimentin Antibodies |

| bDMARDs | Biologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs |

| cGMP | Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate |

| csDMARDs | Conventional Synthetic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs |

| CV | cardiovascular |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| DILE | Drug-induced lupus erythematosus |

| EAT | Epicardial Adipose Tissue |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| E-selectin | Endothelial Selectin |

| ESR | Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate. |

| GCs | Glucocorticoids |

| GRK2 | G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 |

| HCQ | Hydroxychloroquine |

| HF | Heart Failure |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 |

| ICD | Implantable Cardioverter–Defibrillator |

| IKr | Rectifier K⁺ Current |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| LA | Left Atrial |

| LEF | Leflunomide |

| LGE | Epicardial Late Gadolinium Enhancement |

| LQTS | Long QT Syndrome |

| LV | Left Ventricular |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 |

| MHCII | Major Histocompatibility Complex Class Ii |

| MTX | Methotrexate |

| NETs | Neutrophil extracellular traps |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs |

| Pd | P-Wave Dispersion |

| PKG | Protein Kinase G |

| PSVT/SVT | Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia/Supraventricular Tachycardia |

| QTcd | Corrected QT Dispersion |

| QTd | QT Dispersion |

| RA | Rheumatoid Arthritis |

| RA-AF | Rheumatoid Arthritis Associated with Atrial Fibrillation |

| RAAS | Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System |

| RAS | The Renin-Angiotensin System |

| RF | Rheumatoid Factor |

| SASP | Sulfasalazine |

| SBRT | Cardiac Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy |

| tsDMARDs | Targeted Synthetic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 |

| VT | Ventricular Tachycardia |

| WPW | Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome |

References

- Gülkesen, A.; Yıldırım Uslu, E.; Akgöl, G.; Alkan, G.; Kobat, M.A.; Gelen, M.A.; Uslu, M.F. Is the Development of Arrhythmia Predictable in Rheumatoid Arthritis? Arch Rheumatol 2024, 39, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grune, J.; Yamazoe, M.; Nahrendorf, M. Electroimmunology and Cardiac Arrhythmia. Nat Rev Cardiol 2021, 18, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannawi, S.M.; Hannawi, H.; Al Salmi, I. Cardiovascular Risk in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Literature Review. Oman Med J 2021, 36, e262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Shang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Du, J.; Hou, Y. Rheumatoid Arthritis and Risk of Atrial Fibrillation: Results from Pooled Cohort Studies and Mendelian Randomization Analysis. Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications 2024, 9, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plastiras, S.C.; Moutsopoulos, H.M. Arrhythmias and Conduction Disturbances in Autoimmune Rheumatic Disorders. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 2021, 10, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, Y.; Dasu, K.; Gabriel, N.; Roy, T.; Umrani, R.; Lee, M.; Dasu, N.R. Prevalence and Outcomes of Arrhythmias in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Heart Rhythm 2023, 20, S181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.H.K.; Jones, T.N.; Sattler, S.; Mason, J.C.; Ng, F.S. Proarrhythmic Electrophysiological and Structural Remodeling in Rheumatoid Arthritis. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2020, 319, H1008–H1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, G.; Toes, R.E.M. Autoantibodies in Rheumatoid Arthritis – Rheumatoid Factor, Anticitrullinated Protein Antibodies and Beyond. Current Opinion in Rheumatology 2024, 36, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salma, K.; Nessrine, A.; Krystel, E.; Khaoula, E.K.; Noura, N.; Khadija, E.; Taoufik, H. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Seropositivity versus Seronegativity; A Comparative Cross-Sectional Study Arising from Moroccan Context. Curr Rheumatol Rev 2020, 16, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitsina, S.; Mozgovaya, E.; Trofimenko, A.; Bedina, S.; Mamus, M. Electrocardiographic Manifestations in Patients with Seropositive Rheumatoid Arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2021, 80, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Vasdev, V.; Patnaik, S.K.; Bhatt, S.; Singh, R.; Bhayana, A.; Hegde, A.; Kumar, A. The Diagnostic Utility of Rheumatoid Factor and Anticitrullinated Protein Antibody for Rheumatoid Arthritis in the Indian Population. Med J Armed Forces India 2022, 78, S69–S74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyengar, K.P.; Vaish, A.; Nune, A. Anti-Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide Antibody (ACPA) and Rheumatoid Arthritis: Clinical Relevance. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2022, 24, 101729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiewruengsurat, D.; Phongnarudech, T.; Liabsuetrakul, T.; Nilmoje, T. Correlation of Rheumatoid and Cardiac Biomarkers with Cardiac Anatomy and Function in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients without Clinically Overt Cardiovascular Diseases: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc 2022, 44, 101161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Steendam, K.; Tilleman, K.; Deforce, D. The Relevance of Citrullinated Vimentin in the Production of Antibodies against Citrullinated Proteins and the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011, 50, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, S.; Javinani, A.; Aminorroaya, A.; Masoumi, M. Anti-Modified Citrullinated Vimentin Antibody: A Novel Biomarker Associated with Cardiac Systolic Dysfunction in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2020, 20, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzerini, P.E.; Acampa, M.; Hammoud, M.; Maffei, S.; Capecchi, P.L.; Selvi, E.; Bisogno, S.; Guideri, F.; Galeazzi, M.; Pasini, F.L. Arrhythmic Risk during Acute Infusion of Infliximab: A Prospective, Single-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study in Patients with Chronic Arthritis. J Rheumatol 2008, 35, 1958–1965. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Fan, H.; Wang, Y.; Yin, X.; Liu, G.; Gao, C.; Li, X.; Liang, B. Elevated Peripheral T Helper Cells Are Associated With Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 744254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Ito, K.; Depender, C.; Giles, J.T.; Bathon, J. Left Ventricular Remodeling in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients without Clinical Heart Failure. Arthritis Res Ther 2023, 25, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, M.; Tai, Y.; Tao, J.; Zhou, W.; Han, Y.; Wei Wei; Wang, Q. Triggers of Cardiovascular Diseases in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Current Problems in Cardiology 2022, 47, 100853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braz, N.F.T.; Pinto, M.R.C.; Vieira, É.L.M.; Souza, A.J.; Teixeira, A.L.; Simões-e-Silva, A.C.; Kakehasi, A.M. Renin–Angiotensin System Molecules Are Associated with Subclinical Atherosclerosis and Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Modern Rheumatology 2021, 31, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Fei, Z.; Nian, F. The Association Between Rheumatoid Arthritis and Atrial Fibrillation: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology and Management. IJGM 2023, Volume 16, 1899–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacsándi, D.; Fagyas, M.; Horváth, Á.; Végh, E.; Pusztai, A.; Czókolyová, M.; Soós, B.; Szabó, A.Á.; Hamar, A.; Pethő, Z.; et al. Effect of Tofacitinib Therapy on Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1226760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, K.H.K.; Hwang, T.; Se Liebers, C.; Ng, F.S. Epicardial Adipose Tissue as a Mediator of Cardiac Arrhythmias. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2022, 322, H129–H144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, H.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Relationship between Epicardial Adipose Tissue Volume and Atrial Fibrillation in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernault, A.C.; Meijborg, V.M.F.; Coronel, R. Modulation of Cardiac Arrhythmogenesis by Epicardial Adipose Tissue. JACC 2021, 78, 1730–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, M. Characterization, Pathogenesis, and Clinical Implications of Inflammation-Related Atrial Myopathy as an Important Cause of Atrial Fibrillation. JAHA 2020, 9, e015343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radu, A.-F.; Bungau, S.G. Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis: An Overview. Cells 2021, 10, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassilopoulos, D.; Aslanidis, S.; Boumpas, D.; Kitas, G.; Nikas, S.N.; Patrikos, D.; Sfikakis, P.P.; Sidiropoulos, P. Updated Greek Rheumatology Society Guidelines for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Mediterr J Rheumatol 2020, 31, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Hua, Z.; Luo, X.; Li, Y.; Yu, L.; Li, M.; Lu, C.; Zhao, T.; Liu, Y. Application and Pharmacological Mechanism of Methotrexate in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 150, 113074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hloch, K.; Doseděl, M.; Duintjer Tebbens, J.; Žaloudková, L.; Medková, H.; Vlček, J.; Soukup, T.; Pávek, P. Higher Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Without Methotrexate Treatment. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 703279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekeoglu, S. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Cardiovascular Disease in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: A Comparative Analysis of Real-World Data. Int J Gen Med 2024, 17, 5859–5868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunkara, P.; Garikipati, N.A.; Nimmagadda, R.; Cherukuri, A.M.K.; Anne, H.; Chakilam, R.; Yadav, D.; Sunkara, P.; Garikipati, N.A.; Nimmagadda, R.; et al. Cardiovascular Outcomes of Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Review of the Current Evidence. Cureus 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Han, M.; Jung, I.; Ahn, S.S. New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation in Seropositive Rheumatoid Arthritis: Association with Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs Treatment. Rheumatology 2024, 63, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, H.; Kassab, C.J.; Tlaiss, Y.; Gutlapalli, S.D.; Ganipineni, V.D.P.; Paramsothy, J.; Tedesco, S.; Kailayanathan, T.; Abdulaal, R.; Otterbeck, P. Hydroxychloroquine and the Associated Risk of Arrhythmias. gcsp 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones, M.E.; Joseph, J.K.; Dowell, S.; Moore, H.J.; Karasik, P.E.; Fonarow, G.C.; Fletcher, R.D.; Cheng, Y.; Zeng-Treitler, Q.; Arundel, C.; et al. Hydroxychloroquine and Risk of Long QT Syndrome in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Veterans Cohort Study With Nineteen-Year Follow-Up. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2023, 75, 1571–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoque, M.R.; Lu, L.; Daftarian, N.; Esdaile, J.M.; Xie, H.; Aviña-Zubieta, J.A. Risk of Arrhythmia Among New Users of Hydroxychloroquine in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Population-Based Study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2023, 75, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, C.-H.; Wei, J.C.-C.; Wang, Y.-H.; Tsai, C.-F.; Chan, K.-C.; Li, L.-C.; Lo, T.-H.; Su, C.-H. Hydroxychloroquine Does Not Increase the Risk of Cardiac Arrhythmia in Common Rheumatic Diseases: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 631869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eryavuz Onmaz, D.; Tezcan, D.; Abusoglu, S.; Yilmaz, S.; Yerlikaya, F.H.; Onmaz, M.; Abusoglu, G.; Unlu, A. Effects of Hydroxychloroquine and Its Metabolites in Patients with Connective Tissue Diseases. Inflammopharmacology 2021, 29, 1795–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Yu, Y.; Yin, G.; Xu, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhao, G.; Ni, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, B.; et al. Sulfasalazine Promotes Ferroptosis through AKT-ERK1/2 and P53-SLC7A11 in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Inflammopharmacology 2024, 32, 1277–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, C.; Gao, Z.; Jiang, X.; Bai, Y.; Meng, Y. Sulfasalazine Exacerbates Angiotensin II-Induced Cardiac Remodelling by Activating Akt Signal Pathway. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2022, 49, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y. Recent Progress in Treatments of Rheumatoid Arthritis: An Overview of Developments in Biologics and Small Molecules, and Remaining Unmet Needs. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021, 60, vi12–vi20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromolaran, A.S.; Srivastava, U.; Alí, A.; Chahine, M.; Lazaro, D.; El-Sherif, N.; Capecchi, P.L.; Laghi-Pasini, F.; Lazzerini, P.E.; Boutjdir, M. Interleukin-6 Inhibition of hERG Underlies Risk for Acquired Long QT in Cardiac and Systemic Inflammation. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, H.; Kobayashi, Y.; Yokoe, I.; Kitamura, N.; Nishiwaki, A.; Takei, M.; Giles, J.T. Heart Rate–Corrected QT Interval Duration in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Its Reduction with Treatment with the Interleukin 6 Inhibitor Tocilizumab. The Journal of Rheumatology 2018, 45, 1620–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, V.B.; Lunge, S.B.; Doshi, B.R. Cardiac Side Effect of Rituximab. Indian Journal of Drugs in Dermatology 2020, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, E.A.; Cohen, A.F. Abatacept. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009, 68, 480–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Z.; Muraoka, S.; Kawazoe, M.; Hirose, W.; Kono, H.; Yasuda, S.; Sugihara, T.; Nanki, T. Long-Term Effects of Abatacept on Atherosclerosis and Arthritis in Older vs. Younger Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: 3-Year Results of a Prospective, Multicenter, Observational Study. Arthritis Research & Therapy 2024, 26, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandra Deson Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (Dmards): Revolutionizing Rheumatic Disease Management. International Journal of Clinical Rheumatology 2024, 19, 208–210.

- Manilall, A.; Mokotedi, L.; Gunter, S.; Le Roux, R.; Fourie, S.; Flanagan, C.A.; Millen, A.M.E. Inflammation-induced Left Ventricular Fibrosis Is Partially Mediated by Tumor Necrosis Factor-α. Physiological Reports 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senel, S.; Cobankara, V.; Taskoylu, O.; Karasu, U.; Karapinar, H.; Erdis, E.; Evrengul, H.; Kaya, M.G. The Safety and Efficacy of Etanercept on Cardiac Functions and Lipid Profile in Patients with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Investig Med 2012, 60, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Cai, J.; Chen, H.; Feng, Z.; Yang, G. Cardiovascular Adverse Events Associated with Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Inhibitors: A Real-World Pharmacovigilance Analysis. J Atheroscler Thromb 2024, 31, 1733–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talotta, R.; Atzeni, F.; Batticciotto, A.; Ventura, D.; Sarzi-Puttini, P. Possible Relationship between Certolizumab Pegol and Arrhythmias: Report of Two Cases. Reumatismo 2016, 68, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinblatt, M.E.; Westhovens, R.; Mendelsohn, A.M.; Kim, L.; Lo, K.H.; Sheng, S.; Noonan, L.; Lu, J.; Xu, Z.; Leu, J.; et al. Radiographic Benefit and Maintenance of Clinical Benefit with Intravenous Golimumab Therapy in Patients with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis despite Methotrexate Therapy: Results up to 1 Year of the Phase 3, Randomised, Multicentre, Double Blind, Placebo Controlled GO-FURTHER Trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2014, 73, 2152–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; Kay, J.; Landewé, R.B.M.; Matteson, E.L.; Gaylis, N.; Wollenhaupt, J.; Murphy, F.T.; Zhou, Y.; Hsia, E.C.; Doyle, M.K. Golimumab in Patients with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis Who Have Previous Experience with Tumour Necrosis Factor Inhibitors: Results of a Long-Term Extension of the Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled GO-AFTER Study through Week 160. Ann Rheum Dis 2012, 71, 1671–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkshoorn, B.; Raadsen, R.; Nurmohamed, M.T. Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Rheumatoid Arthritis Anno 2022. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Luo, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Huang, Y. Cardiovascular Safety of Janus Kinase Inhibitors: A Pharmacovigilance Study from 2012–2023. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0322849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosrow-Khavar, F.; Kim, S.C.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.B.; Desai, R.J. Tofacitinib and Risk of Cardiovascular Outcomes: Results from the Safety of TofAcitinib in Routine Care Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (STAR-RA) Study. Ann Rheum Dis 2022, 81, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, S.L.; Kontaridis, M.I. Cardio-Rheumatology: The Cardiovascular, Pharmacological, and Surgical Risks Associated with Rheumatological Diseases in Women. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2024, 102, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conaghan, P.G.; Mysler, E.; Tanaka, Y.; Da Silva-Tillmann, B.; Shaw, T.; Liu, J.; Ferguson, R.; Enejosa, J.V.; Cohen, S.; Nash, P.; et al. Upadacitinib in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Benefit–Risk Assessment Across a Phase III Program. Drug Saf 2021, 44, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariette, X.; Borchmann, S.; Aspeslagh, S.; Szekanecz, Z.; Charles-Schoeman, C.; Schreiber, S.; Choy, E.H.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Schmalzing, M.; Tanaka, Y.; et al. Major Adverse Cardiovascular, Thromboembolic and Malignancy Events in the Filgotinib Rheumatoid Arthritis and Ulcerative Colitis Clinical Development Programmes. RMD Open 2025, 11, e005033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Xin, Y.; Zheng, H.; Yun, C.; Kwan, E.; Qin, A.; Namour, F.; Kearney, B.P.; Mathias, A. Filgotinib, a JAK1 Inhibitor, Has No Effect on QT Interval in Healthy Subjects. Clinical Pharm in Drug Dev 2020, 9, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, B.W.; Baker, J.F.; Hsu, J.Y.; Wu, Q.; Xie, F.; Curtis, J.R.; George, M.D. Association of Cardiovascular Outcomes With Low-Dose Glucocorticoid Prescription in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatology 2024, 76, 1585–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawałko, M.; Peller, M.; Balsam, P.; Grabowski, M.; Kosiuk, J. Management of Cardiac Arrhythmias in Patients with Autoimmune Disease—Insights from EHRA Young Electrophysiologists. Pacing Clinical Electrophis 2020, 43, 1194–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdale, J.E.; Chung, M.K.; Campbell, K.B.; Hammadah, M.; Joglar, J.A.; Leclerc, J.; Rajagopalan, B. ; On behalf of the American Heart Association Clinical Pharmacology Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing Drug-Induced Arrhythmias: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, Y.; Sekiguchi, A.; Kato, T.; Yamashita, T. Glucocorticoid Induces Atrial Arrhythmogenesis via Modification of Ion Channel Gene Expression in Rats: Molecular Evidence for Stress-Induced Atrial Fibrillation. Int. Heart J. 2022, 63, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.-W.; Wang, X.-H.; Shi, J.; Yu, J.-G. Sinomenine in Cardio-Cerebrovascular Diseases: Potential Therapeutic Effects and Pharmacological Evidences. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 749113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saramet, E.E.; Negru, R.D.; Oancea, A.; Constantin, M.M.L.; Ancuta, C. 24 h Holter ECG Monitoring of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis-A Potential Role for a Precise Evaluation of QT Interval Duration and Associated Arrhythmic Complications. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, C. Autoimmunity and Biological Therapies in Cardiac Arrhythmias. MRAJ 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tc, T.; Pe, N. Antiarrhythmic Agents: Drug Interactions of Clinical Significance. Drug safety 2000, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C, C.; Me, G. Drug-Induced Lupus Erythematosus: Incidence, Management and Prevention. Drug safety 2011, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irizarry-Caro, J.A.; Carmona-Rivera, C.; Schwartz, D.M.; Khaznadar, S.S.; Kaplan, M.J.; Grayson, P.C. Brief Report: Drugs Implicated in Systemic Autoimmunity Modulate Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018, 70, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyaya, S.; Agarwal, M.; Upadhyaya, A.; Pathania, M.; Dhar, M. Rhupus Syndrome: A Diagnostic Dilemma. Cureus 2022, 14, e29018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, M.; Kovačević, M.; Vezmar-Kovačević, S.; Palibrk, I.; Bjelanović, J.; Miljković, B.; Vučićević, K. Lidocaine Clearance as Pharmacokinetic Parameter of Metabolic Hepatic Activity in Patients with Impaired Liver. J Med Biochem 2023, 42, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhourani, N.; Wolfes, J.; Könemann, H.; Ellermann, C.; Frommeyer, G.; Güner, F.; Lange, P.S.; Reinke, F.; Köbe, J.; Eckardt, L. Relevance of Mexiletine in the Era of Evolving Antiarrhythmic Therapy of Ventricular Arrhythmias. Clin Res Cardiol 2024, 113, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johri, M.; Stewart, C. FLECAINIDE AS A FATAL CAUSE OF DIFFUSE ALVEOLAR DAMAGE. CHEST 2023, 164, A3276–A3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Gershwin, M.E. Drug-Induced Lupus Erythematosus: Incidence, Management and Prevention. Drug Saf 2011, 34, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhelwa, A.Y.; Foster, D.J.R.; Manning-Bennett, A.; Sorich, M.J.; Proudman, S.; Wiese, M.D.; Hopkins, A.M. Concomitant Beta-Blocker Use Is Associated with a Reduced Rate of Remission in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis Treated with Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs: A Post Hoc Multicohort Analysis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2021, 13, 1759720X211009020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sills, J.M.; Bosco, L. Arthralgia Associated with Beta-Adrenergic Blockade. JAMA 1986, 255, 198–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatu, A.L.; Elisei, A.M.; Chioncel, V.; Miulescu, M.; Nwabudike, L.C. Immunologic Adverse Reactions of β-Blockers and the Skin. Exp Ther Med 2019, 18, 955–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assad, A.; Alkhaldi, M.; Abrahamian, A.; Yonel, B.; Assaly, R.; Altorok, N. Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage Synergistically Induced by Amiodarone and Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep 2023, 11, 23247096231196698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenasa, F.; Shenasa, M. Dofetilide: Electrophysiologic Effect, Efficacy, and Safety in Patients with Cardiac Arrhythmias. Cardiac Electrophysiology Clinics 2016, 8, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fravel, M.A.; Ernst, M. Drug Interactions with Antihypertensives. Curr Hypertens Rep 2021, 23, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Xia, H.; Hu, J.; Liu, Y.-N.; Wang, A.; Cai, J.-P.; Hu, G.-X.; Xu, R.-A. CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 Genetic Polymorphisms and Myricetin Interaction on Tofacitinib Metabolism. Biomed Pharmacother 2024, 175, 116421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Mahdy, N.A.; Tadros, M.G.; El-Masry, T.A.; Binsaleh, A.Y.; Alsubaie, N.; Alrossies, A.; Abd Elhamid, M.I.; Osman, E.Y.; Shalaby, H.M.; Saif, D.S. Efficacy of the Cardiac Glycoside Digoxin as an Adjunct to csDMARDs in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15, 1445708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.; Geist, G.E.; Pfenniger, A.; Rottmann, M.; Arora, R. Recent Advances in Gene Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation. Cardiovasc electrophysiol 2021, 32, 2854–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of study | Year of publication | Number of patients |

Data and conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retrospective, propensity score–matched cohort safety study | 2023 | 8.852 | HCQ was not linked to an increased risk of long QT syndrome during the first two years of use. A higher risk emerged after five years, though the absolute risk remained low, with a minimal difference between those taking HCQ and those not. The risk decreased with longer follow-up, supporting HCQ's long-term safety in RA patients [35]. |

|

Retrospective cohort study |

2023 | 23.036 | Using data from 1996 to 2014, the cohort included 11.518 HCQ initiators and non-initiators. Over a follow-up of eight years, 1.610 arrhythmias occurred in the HCQ group and 1.646 in the non-HCQ group, with crude incidence rates of 17.5 and 18.1 per 1,000 person-years, respectively. HCQ initiation was not associated with an increased risk of arrhythmia [36]. |

|

Retrospective cohort study |

2021 | 3.575 | The use of HCQ was not associated with an increased risk of overall cardiac arrhythmia including ventricular arrhythmias, in patients with RA, systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren's syndrome, regardless of dose or treatment duration [37]. |

|

Observational, analytical study |

2021 | 70 | There was a positive correlation between blood HCQ and its metabolite levels with QTc interval, with average interval 390 ms [38]. |

| TNF-A inhibitors | Etanercept | Conclusions | Data and References |

| Cardioprotective in patients without HF. Reduce arterial stiffness, LV mass index, and overall CV morbidity in RA. | To investigate the effects of etanercept on cardiac functions were assigned seventy Sprague-Dawley rats with collagen-induced arthritis. Etanercept was administered for 6 weeks post-arthritis onset. LV structure and function were assessed by echocardiography, inflammatory markers by ELISA, and gene expression by quantitative PCR. The findings show that systemic inflammation contributes to LV fibrosis and extracellular matrix remodelling via increasing macrophage infiltration and local cardiac expression of pro-fibrotic genes. Etanercept partially inhibits collagen remodelling, but it does not stop diastolic dysfunction from starting, suggesting that other mechanisms besides TNF-α are involved [48]. Over the course of a 6-month follow-up with patients who had active disease, etanercept was demonstrated to be safe in terms of cardiac function and lipid profile and to be beneficial in improving RA parameters [49]. | ||

| Infliximab | The literature suggests that infliximab may be associated with life-threatening tachyarrhythmia and bradyarrhythmia. Improve arterial stiffness and vascular function in RA patients. | Infliximab and the risk of arrhythmias in RA have not been linked in any research published in the past five years. Older data and sporadic case reports without contemporary clinical study validation provide the only evidence of arrhythmogenicity. According to the literature, infliximab may be linked to bradyarrhythmia and tachyarrhythmia, which are potentially fatal. The total incidence of arrhythmias during infliximab infusion did not differ significantly from that of a placebo. Ventricular tachyarrhythmias with a recent onset, however, were more common and severe. Prolonged QT intervals and decreased heart rate variability were seen in affected patients, primarily those with RA [16]. | |

| Adalimumab | Inconclusive, one study showed increased thrombotic events, but no study data confirmed an arrhythmic risk. | A retrospective pharmacovigilance study revealed that adalimumab was the only TNF-α inhibitor associated with an elevated risk of cardiovascular adverse events (myocardial infarction, arterial thrombosis), whereas the other four TNF-α inhibitors did not show any risk effect [50]. | |

| Certolizumab pegol | Isolated cases report of arrhythmias, which may be associated with other CV risks. Favourable CV profile due to reduced systemic inflammation. | There are no specific studies or case reports in the last five years. A 2016 case report described two RA patients on certolizumab and MTX who developed serious arrhythmias: one with persistent AF resistant to cardioversion, and another with AFl managed by beta-blockers. Certolizumab pegol dosing intervals were extended, and MTX reduced in one case, without RA flare-ups [51]. | |

| Golimumab | Demonstrated cardioprotective effects in the GO-BEFORE and GO-FORWARD trials through improved cardiovascular markers. However, caution is advised in patients with HF. | A 2014 study evaluating intravenous golimumab (2 mg/kg) plus MTX over 52 weeks in active RA reported one case of AF between weeks 24 and 52 [52]. Across multiple long-term extension studies (GO-AFTER, GO-MORE, GO-FURTHER), no further increase in arrhythmia incidence was observed beyond the isolated cases previously reported [53]. | |

| Interleukine-6 Inhibitors | Tocilizumab | Suggest a potential antiarrhythmic effect, normalise the QTc interval by dampening systemic inflammation. | There are not recent data, a 2018 study of 94 RA and 42 non-RA controls patients, suggest a potential antiarrhythmic effect of IL-6 inhibition and reinforce the link between RA-related inflammation and elevated cardiovascular risk. The observed QTc normalisation with tocilizumab and its correlation with CRP reduction support the role of systemic inflammation in cardiac repolarisation abnormalities in RA [43]. |

| CD-20 monoclonal antibody | Rituximab | The literature suggests that Rituximab may be associated with arrhythmias. | Cardiovascular toxicity, including cardiac arrhythmias, has been reported in 8% of patients treated with rituximab. These arrhythmias encompass monomorphic and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, trigeminy, bradycardia, AF as well as nonspecific dysrhythmias and tachycardia. It is hypothesised that the CD20 antigen may influence calcium ion channel function [44]. |

| Selective T-cell co-stimulation inhibitor | Abatacept | Most available cardiovascular data pertain to HF arterial stiffness, lipid profiles, and major adverse cardiovascular events, rather than to cardiac rhythm disorders. | It may slow atherosclerosis progression and benefit high-risk patients [46]. Hypertension has been reported as a possible side effect in 1–10% of cases. However, the cardiovascular risk reduction associated with the anti-inflammatory effect of abatacept appears to remain unaffected [54]. |

| JAKinhibitors | Tofacitinib | FAERS data suggest JAK inhibitors may raise cardiovascular AE risk, particularly in older patients or those with pre-existing heart conditions. The literature does not provide evidence of a direct link between JAK inhibitors and specific arrhythmias. | Tofacitinib demonstrated signals for embolic/thrombotic events and hypertension [55]. The most recent study, STAR-RA, does not provide evidence of a direct link between tofacitinib and specific arrhythmias. The available data focus solely on major adverse cardiovascular events (including myocardial infarction and stroke), not on cardiac rhythm disturbances [56]. |

| Baricitinib | Baricitinib showed stronger associations with embolic and thrombotic events, torsade de pointes/QT prolongation pulmonary hypertension, ischemic heart disease, cardiac arrhythmias and cardiac failure [55]. Events of arrhythmia, HF and sudden cardiac death have been reported in post-marketing settings [57]. | ||

| Upadacitinib | Upadacitinib was associated with pulmonary hypertension, embolic and thrombotic events, ischemic heart disease, torsade de pointes/QT prolongation, HF,cardiac arrhythmias and cardiomyopathy [55]. It has shown an arrhythmia signal in spontaneous reporting systems, but clinical studies have not confirmed or quantified this risk [58]. | ||

| Filgotinib | Integrated analyses over >12.500 patient, with years of exposure confirm low rates of major adverse cardiovascular events and venous thromboembolism, with no evidence of rhythm-related cardiac events [59]. A 2019 study proved that there were no clinically relevant relationships between QTc interval and plasma concentrations of filgotinib or its major metabolite [60]. |

| Class | Mechanism of Action/ Indications | Examples | Drug safety for RA-patients | |

| Class I (Sodium (Na⁺) channels) | ||||

| Ia | Slows conduction, prolongs repolarization Used for AF, VT, WPW syndrome. |

Quinidine, Procainamide, Disopyramide |

Due to the potential of quinidine to cause a lupus-like syndrome, the use should be evaluated [69]. In 2018, Irizarry-Caro reported that procainamide is a lupus-inducing drug, promoting NET formation via neutrophil muscarinic receptor activation and calcium flux, highlighting innate immune involvement in DILE [70]. Rhupus syndrome, an overlap of RA and systemic lupus erythematosus, occurs in approximately 0.01–2% of rheumatic disease cases and the use of lupus-inducing drug need to be restricted [71]. The literature dose note provide data about autoimmunity induced by disopyramide or side effects that can alter the RA patient’s health status. | |

| Ib | Shortens repolarization. Used for VT (especially post-MI), not for atrial arrhythmias. |

Lidocaine, Mexiletine |

Lidocaine is metabolized in the liver. RA patients often use hepatotoxic drugs such as MTX, which can impair liver function and reduce lidocaine clearance, increasing the risk of toxicity [72]. Mexiletine can present diverse side effects, mostly related to the gastrointestinal tract and nervous system, but also hematological. The most prevalent symptoms are nausea, abdominal pain/discomfort, tremors, headaches, dizziness and thrombocytopenia, which can emphasise the existing health problems [73]. | |

| Ic | Slows conduction, no effect on repolarization. Used for AF, SVT. |

Flecainide, Propafenone | Patients with RA are at elevated risk for interstitial lung disease. Flecainide has been linked to potentially drug-induced interstitial pneumonitis or diffuse alveolar damage [74]. Propafenone is recognized as a very low-risk drug for inducing drug-induced lupus ,with < 0.1% incidence at clinically used doses [75]. | |

| Class II (β-adrenergic receptors) | ||||

| Beta-blockade → ↓ sympathetic tone, ↓ AV conduction. Used for AF (rate control), SVT, ventricular ectopy, post-MI. |

Metoprolol, Atenolol, Esmolol |

The literature presents beta-blocker use was independently associated with a lower likelihood of achieving remission [76]. In 1986, FDA reports described several cases of joint pain linked to metoprolol, which disappeared within a few days after the drug was stopped [77]. Atenolol can cause vasculitis and drug-induced lupus erythematosus [78]. There are no studies about Esmolol linked to negative effects on RA disease activity. | ||

| Class III (Potassium (K⁺) channels) | ||||

| Prolongs repolarization (↑ APD & QT interval), Used for AF, VT, VF |

Amiodarone, Sotalol, Dofetilide, Ibutilide |

Patients with preexisting pulmonary disease (RA-associated interstitial lung disease) are particularly vulnerable to amiodarone. The literature presents cases of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage syndrome induced [79]. Sotalol can induce vasculitis [78]. Dofetilide is primarily excreted through the kidneys, with about 80% eliminated renally, while approximately 20% to 30% is metabolized in the liver via the CYP3A4 enzyme pathway. Therefore, dose adjustments are necessary for RA patients with impaired kidney function [80]. There are no studies about Ibutilide linked to negative effects on RA disease activity. | ||

| Class IV (Calcium (Ca²⁺) channels) | ||||

| ↓ AV node conduction & automaticity. Used for AF (rate control), SVT. |

Verapamil, Diltiazem |

Calcium channel blockers, specifically diltiazem and verapamil, have been well established as strong inhibitors of CYP3A4, with most major drug interactions linked to these two medications [81]. Tofacitinib, a JAK inhibitor, is significantly metabolized by CYP3A4. In this case the association need to be evaluated [82]. | ||

| Others/ Various targets | ||||

| Mixed or unique mechanisms Used for PSVT (adenosine), rate control in AF (digoxin), sinus tachycardia. |

Adenosine, Digoxin, Ivabradine |

Digoxin was well tolerated in RA patients and demonstrated significant immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects. Additionally, it may possess anti-angiogenic properties, suggesting that it could serve as an effective adjunct to csDMARDs in the treatment of RA [83]. There are no studies about Adenosine or Ivabradine linked to negative effects on RA disease activity. | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).