2.1. Brief Introduction to the Concept of “Entropy as a Criterion for Sustainability” and Its Application to CDR Technologies

2.1.1. Entropy as a Criterion for Sustainability

There are widespread, rather inaccurate preconceptions and prejudices, especially about thermodynamics, and entropy in particular. This section therefore attempts to outline modern thermodynamics, at least briefly [6].

The first prejudice is that thermodynamics is an old and outdated science with no big value for any of our modern scientific questions and even less for our actual global crises. However, this approach ignores the modern nonequilibrium thermodynamics created by Ilya Prigogine, who was awarded for this achievement with the Nobel Prize in 1977 [7]. The name of his thermodynamics adresses a preconception: This science field not only consists of the old and well-known equilibrium thermodynamics with a side branch of close-to-equilibrium nonequilibrium systems but also far-from-equilibrium systems.

The second preconception concerns entropy: According to the 2nd law of thermodynamics, entropy cannot decrease, which so far is correct. However this is valid only for isolated closed systems with no exchange of energy or matter with anything outside. So people just assume that entropy is always and everwhere just increasing. Only closed systems tend to reach equilibrium, which is associated with the highest entropy level characteristic of this system. Consequently, it is widely overlooked that by far most of the real systems are open systems that exchange energy/matter with their environment. Prigogine found that entropy can and will inevitably decrease if the energy influx is overcritical (an amount that is different and characteristic of each system for each process). If this happens, the system will spontaneously develop very complex, so-called “dissipative” structures. “Dissipative” because said systems cannot cope with this overcritical energy influx other than by exporting entropy, i.e., entropy decreases inside said system, while entropy increases by orders of magnitude more outside it. Importantly, an entropy minimum is combined with the formation of complex structures and complex processes within this system. In other words, loss of complexity is equivalent to an increase in entropy. We can also generalize and say that loss of valuability (be it energy, matter, or functioning complexity) is accompanied by an increasing amount of entropy in the systems where this loss is happening.

This leads us to a fourth preconception or, better, oversimplification: Entropy is widely misunderstood as simply being a measure of disorder. However, first and foremost, entropy is a measure for lower valuability of energy (and hence also lower valuability of matter). Boltzman’s interpretation of the entropy of a system by the probability of the arrangement of the system’s components and interpretation is not (as often misunderstood) the definition of entropy. The definition of entropy Its definition is dS = dQ/T, with dS being change in entropy, dQ the change in heat per temperature T. For chemical reactions it is dG = dH – TdS [or: dS = (dH – dG)/T], i.e.: entropy change is the difference of reaction enthalpy and free enrgy change divided by temperature. Boltzman’s formula S = k*lnP (k being the “Boltzman constant”, P the probability) is just one interpretation of entropy. tells us that there is no process with energy (and often matter) turnover that would not produce entropy. In other words, with every such process, energy (and matter) within a given system will inevitably reach a lower level of valuability or “usability” unless more energy in an overcritical amount flows into this system, which, on the other hand, will increase entropy whereever the energy comes from.

In addition, while products or services generated or enabled by this energy supply are used, entropy is again generated. Entropy constantly affects us and the entire environment. We cannot escape it, nor can we ignore it, just as we cannot escape or ignore gravity, whether we like it or not. An increase in entropy can be “seen” in all kinds of forms, such as waste heat, heat loss from our living space (we must heat our houses constantly unless we live in hot regions where air conditioning produces entropy), efficiency loss in power plants and car motors, such as waste (ash, industry and household waste), corrosion, friction and abrasion, and microplastic, as well as our own (and any other animals’) urine and feces, loss of water and emission of CO2 during breathing, as well as CO2 emissions from power plants, combustion engines or concrete plants, and environmental pollution. All this is manifestation of entropy.

CO2 itself represents a higher standard entropy [8] than C (carbon in the gaseous state) and O (oxygen), and more entropy is produced when CO2 and H2O (water) are diluted within the atmosphere; this entropy is the so-called “entropy of mixing”.

Any process with turnover of energy and matter is principally irreversible: heat in a living room cannot be converted back to wood, coal, oil, or gas which when burnt generated the heat. Nuclear fusion in the sun can and will not be reversed (i.e., helium+heat+infrared cannot be reformed into hydrogen), a few billion years from now, the earth will no longer be habitable; electricity transported to industry and households will be used and cannot flow back to the power plant, recover fossil oil or gas and generate new electricity: there is no perpetuum mobile; iron oxide on bridges generated by corrosion cannot be reversed to intact steel bars; microplastics cannot be collected and recycled into clean raw plastics or bottles, packaging and other materials, such as tire abrasion, generated and lost during driving, can never become tires again. A boiled egg cannot be turned back into a fresh raw egg, and the eggshells that end up in the trash when we peel the boiled egg cannot be given back to the chicken, helping it grow a new egg.

The same is true for biodiversity: The complex interactive network in the ecosystems of our biosphere consists of unnumerable kinds of species, and it therefore represents a state of minimal entropy (which is, if not destructed by us, is maintained by constant overcritical influx of solar energy). Reducing the number of representative species in a region or globally and reducing the number of species on earth are equivalent to reducing complexity, i.e., increasing entropy. If the number and diversity of species in the soil of agricultural land is reduced by pesticides and if fertile soil is lost by erosion The amount of erosion, i.e., loss of potentially fertile soil, even in flat regions amounts to almost 2 mm/year equivalent to 22.5 +/- 7.2 metric tons per hectare and year for conventionally farmed land, which are in total 57.6 × 109 +/- 37.8 × 109 tons over the past 150 years in the study area in Midwestern US [9]a). Soil erosion is much less on biologically farmed land (approximately 0.2 tons per hectare and year, compared to 22.5 tons per hectare and year) depending on the farming practice, especially whether or not land is covered with plants all year round [9]b). [9], then the entropy again increases, partially because of loss of complexity and partially because of the entropy of mixing as nutrients, organic and inorganic components of the eroded soil are distributed or dissolved first in flowing water and finally in the sea. In addition, extinct species can never be brought back to exist.

Considering all this, the author has proposed to use entropy as a criterion for sustainability, with the following understanding:

- Sustainability comprises the whole biosphere, not only the climate, i.e. it concerns the whole biosphere and not only humans and their (relatively short-term) needs but also all members and components of ecosystems as humans live from what the earth can sustainably produce (including but by far not only pure water, fresh clean air, and fertile soil).

- A certain product or process A can be called “more sustainable” than alternative B; if A produces less entropy, entropy in any form.

This concept was first published by the author in 2024 [10]. It was laid out in even more detail in his new book “on the origin of unpredictability, complexity, crises and time” [11] and in a compact form in [12].

2.1.2. Sustainability Analysis of CDR Technologies with the Entropy Criterion

This concept allows us to check whether or not CDR (carbon dioxide reduction), such as direct air capture (DAC), carbon capture and storage (CCS), and carbon capture and use (CCU) technologies, are sustainable or at least more sustainable than other alternatives in public discourse. For details of the processes to be examined and of the calculation leading to the results shown below, the readers are referred to references [10,11] and [12] and the references cited therein, [10] and [12] also contain English translations of the original publications.

The total heat and electricity requirement for the DAC is 7*106 kJ per metric ton of CO2 captured. This amount is almost six times greater than we had received as valuable energy for industrial, infrastructure, household and other uses when generating and emitting 1 ton of CO2, not yet taking into account that more recent numbers disclosed by Climeworks for their two DAC plants in Iceland are showing the practical electricity demand to be 2 to 3 times higher than previously predicted [13]. To stabilize the current CO2 concentration in the atmosphere (i.e., not yet reduce it), one would need 22 PWh of electricity (plus primary energy for heat) only to remove the emissions. Taking the electricity production figures for 2024 (assuming the real energy demand is 1.5 or – as recently reported – 2 to 3 times higher than originally published), the total worldwide electricity production or even much more would be required for DAC to remove the current emissions only.

Moreover, when looking just at the shear volume of CO2 to be captured, it was reported that capturing only daily worldwide emissions would require an industry (capable of handling such volumes) equivalent to 10 to 20 times the size of the actual oil extraction and further processing industry.

When looking at the entropy production only for running DAC plants (not yet for building them and the infrastructure needed for it, and not considering entropy production during storing the compressed gas deep in the earth), one can see: For 1 ton of captured CO2, the atmosphere entropy is reduced by 4.15 MJ/K, which includes the entropy contribution caused by capturing H2O, which cannot be avoided. To reduce the entropy of mixing in the atmosphere, more than 1,000 times as much entropy (approximately 7 GJ/K) is produced on the Earth’s surface and in the oceans [11, p. 231]. This means that for 1 unit of positive climate stabilization effect, we have to “pay” with more than 1,000 units of negative environmental effects, which translates into pollution, destruction, degeneration, massive consumption of environmental goods and losses of all kinds, not least in terms of species decline.

Although the CO2 concentration is much higher in CCS plants than in the atmosphere, the results of the sustainability analysis would be not much better than for DAC. This is not only because much more water is absorbed together with CO2 but also because the various power or cement and concrete plants waste gasses contain many other partially toxic or otherwise harmful or troublesome gasses. Because the storage part of CCS requires CO2 transportation from the source to some central location with a suitable infrastructure where the CO2 would be stored deep underground (for Germany, Denmark and Norway, it is intended to be stored under the North Sea, which is being tested in pilot scale). Transport is planned to occur in pipelines, with transfer across water carried out by ship, at least in the beginning. As CO2 will inevitably be accompanied by massive amounts of water, steel will be corroded quickly, especially as CO2 from many different emitters (including various accompanying gases, including water), will be mixed [14]. To overcome this, both very strict specifications for the gasses to be transported as well as much more efficiently as corrosion-resistant steels will be required.

For CCU, the situation is much worse. Not only does CO2 need to be captured first (which is already anything but sustainable), but it must also be purified; otherwise, the following chemical reactions will not (efficiently enough) work. It was reported (cf. references in [10,12]) that – only theoretically, assuming that any organic chemical in use in the global chemical industry would be generated from CO2 as a raw material – this would require more than 18.1 PWh of electricity from regenerative sources, which not only are not available (because at least 22 PWh are already used by DAC!), but moreover, it would add another 55% of the total global electricity generation projected for 2030. However, it would account for only 10% of the actual CO2 emissions. This shows how the use of CO2 as a raw material for the chemical industry would be absurd. It can not be an excuse to argue one does not plan to use CO2 as raw material for all and any organic chemical actually in use in the chemical industry and beyond it, but “only” for very well selected ones. The calculation shows that any CCU project is even more unsustainable than already DAC alone which is true for any small or large scale.

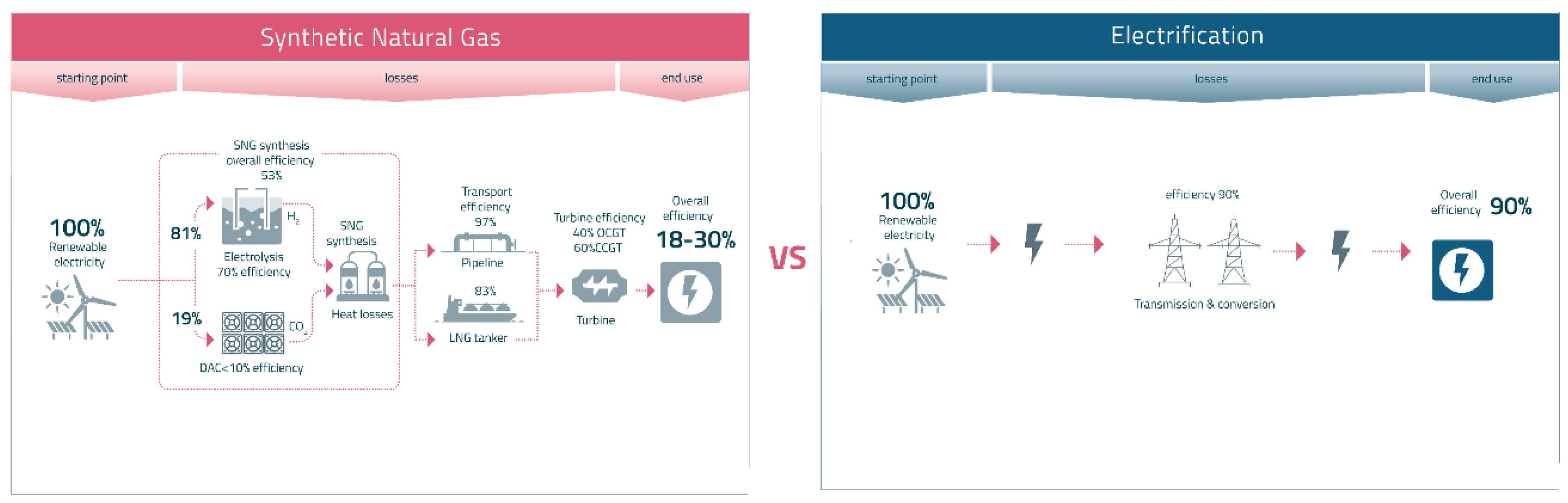

In addition to the use of captured CO

2 for the chemical industry, promoting “CO

2-free (climate-neutral)” fuels is popular. However, if the electricity necessary for the hydrogen generation and further chemical steps to produce such “sustainable” fuels would be used directly for driving electric vehicles, these vehicles can drive up to 10 times longer than when “green” fuels are used. The same is the case for producing so-called “sustainable air fuel” (SAF, an allegedly sustainable fossil-based kerosin replacement). This can be seen in

Figure 1.

Unsurprisingly, it is extremely energy demanding to chemically reduce CO2 to methanol (MeOH) or other industrially important organic chemicals or, allegedly “sustainable kerosin”, as CO2 represents a high content of entropy. It requires much energy to split up the C‒O bond (in other words: reducing the entropy content of CO2), much more than we had been able to use the energy released during the formation of this bond, and it requires more energy to add some hydrogen to finally obtain CH3OH, methanol. (Moreover, providing the necessary amount of energy for reducing the entropy of the reaction system containing CO2 and H2 generating CH3OH unavoidably creates huge amounts of entropy outside the reaction vessels.)

A large portion of this is the high demand of electricity for the electrolysis of water to generate “green” hydrogen (H2). However, there is already a basic problem: Solar or wind power is mostly available where there is either no water (in desert land with plenty of sunshine) or plenty of water but with high salt concentrations (such as in the windy North Germany). In both cases, it is necessary to build and run desalination plants—again, more electricity and more entropy, including another mostly ignored environmental damage. The coastal areas where the desalination plants are running become polluted with brine effluent [15] and have extremely high salt concentrations together with many other components in sea water hence toxic to coastal ecosystems. In addition, the brine contains chemicals necessary for the desalination of polluting coastal waters even more.

In conclusion:

- CO2 emission and dilution in the atmosphere are understood as a process leading toward thermodynamic equilibrium, i.e., accompanied by increasing entropy (in the atmosphere: the entropy of mixing); the same is true for any pollution of rivers, ground or coastal waters, and soil erosion in agriculture with loss of nutrients and humus into the seas: processes toward equilibrium with increasing entropy; this is also the case with the formation and distribution of microplastic, abrasion or corrosion products and any degradation of functioning complexity, such as ecological networks, and a decrease in biodiversity: entropy increases toward equilibrium. CDR requires an overcritical amount of energy accompanied by a decrease in entropy of the atmosphere and orders of magnitude greater increase in entropy of the Earth’s surface.

- Entropy is a useful physical quantity for objectively and falsifiably judging sustainability, comparing different processes or products with respect to their degree of (non)sustainability. Life is a “dissipative structure” (or process) with minimum entropy created in nonequilibrium far from equilibrium, “equilibrium is death” Ludwig von Bertalanffy, the creator of the “steady state” (“Fliessgleichgewicht”) theory, wrote: “Biologically, life is not maintenance or restoration of equilibrium but is essentially maintenance of disequilibria [i.e.: “nonequilibrium” in the sense of Prigogine’s theory, BW], as the doctrine of the organism as open system reveals. Reaching equilibrium means death and consequent decay.” [16]. To maintain functioning nonequilibrium systems, constant overcritical energy influx and energy-consuming work are needed. The increase in entropy accompanied by these processes will accumulate on Earth as waste, pollution, complexity decay and losses if it (the entropy) cannot be emitted as infrared radiation into space (cf. below).

- Energy demand and entropy increase analysis reveals that CDR technologies are far from sustainable; in fact, collateral environmental damage will be by orders of magnitude greater than the positive effect in mitigating climate change.

2.2. Preservation of Biodiversity Plus Natural CO2 Capture and Storage Mechanisms in Ecosystems (with Focus on Bio-Agriculture)

2.2.1. Sustainability of Natural Processes from Entropy Standpoint of View

The extreme energy requirements and entropy costs of technological approaches to mitigating climate change are not sustainable in terms of comprehensive “sustainability” that encompasses the entire biosphere and not just the climate. If a product or a process is CO2 neutral, this does not necessarily mean that it is also sustainable. CDR technologies are not sustainable at all, as shown above.

Therefore, we must develop an approach capable of addressing both crises, i.e., species decline and climate change, without mitigating one crisis with approaches that exacerbate the other. It is quite obvious to look at natural ecosystems, as plants are living from CO2. The necessary amount of overcritical energy is provided by the sun. The nominally low efficiency of photosynthesis (approximately 1%) partially shows how much entropy is also generated during this natural process because of the extremely complex reaction sequences and cycles, which allow entropy reduction (in plants and ecosystems) during CO2 conversion to plants and their complex structures, with their energy providing content used by animals, including humans. However, solar power also drives weather and climate, provides warmth, drives the global water and methane cycles, and creates ozone.

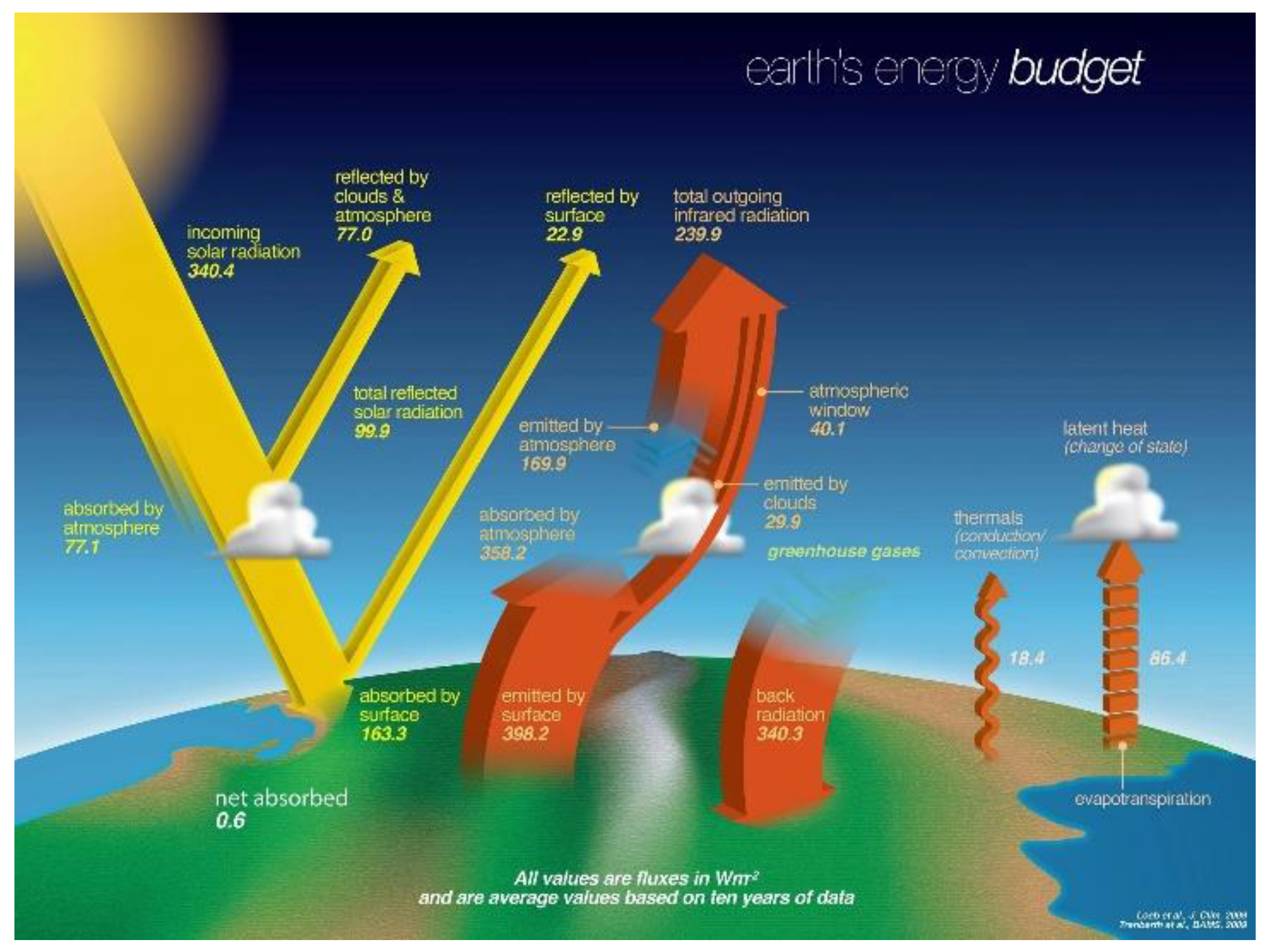

With respect to entropy, it is important to note that these processes, while reducing entropy due to build-up of complex structures (ecosystems), also produce considerable entropy, such as every process connected with energy/matter turnover. However, this entropy is mostly exported into space as low-temperature heat via long-wave infrared radiation (the sun imports an average of 235 W/m² from the Earth’s surface, and the Earth exports the equivalent amount of entropy [17], cf.

Figure 2). This entropy export is connected with the origin [18] and later maintenance of life, including evolution: “dissipative structures” in Prigogine’s terminology of his nonequilibrium thermodynamics. We can therefore consider natural CDR processes via photosynthesis to be truly sustainable. These activities take place in many different ecosystems, such as forests with a wide variety of tree species and grassy openings, moors and other wetlands, river floodplains, mangrove and kelb forests, seagrass beds and savannas, and large open grasslands with their wild inhabitants, as reviewed with their respective CDR potential in chapter 8 of [11].

2.2.2. Biodiversity Improvement and CDR Contribution by Organic Farming

“Net zero agriculture” is a goal within the United Nations “net-zero food plan”

https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/12/1144617, so we will analyze how and what biological (green) agriculture can contribute to the preservation of biodiversity. After this, we will look at the CDR mechanisms in ecosystems with a focus on soil.

There is no need to describe the actual and already decades-long ongoing dramatic worldwide species decline which is a very serious threat to the survival of mankind as well. Conventional agriculture is, owing to the practices (chemicals used for fertilization and suppression of (in view of crop yield) “harmful” weeds, insects and other organisms [5.1], in combination with land consolidation, monoculture crop cultivation and high mechanization with ever and ever heavier machines), the most important cause for the loss of species and decrease in biodiversity, both for plants and for land, air and water organisms [19].

We will therefore look at how bioagriculture could change this, and instead of trying to describe a theoretical worldwide potential picture, we will focus on just one specific real-life example in Germany. This describes what can also be realized on a medium large scale, as the farm to be looked at is not small and can serve as a model: the Kattendorf farm. Kattendorfer Hof”,

https://www.kattendorfer-hof.de

The core of the present farm has a historic root in an approximately 110 ha large farm run by a Christian foundation located at Hamburg. Thirty years ago, the farmer Mathias von Mirbach closed a contract with this foundation and rented the farmstead (land and buildings). A few years later, he changed sales channels to the “community supported agriculture” (CSA) This is a form of direct marketing in which the individual consumers are booking a share of the farm’s crops harvest and products, so that the farm does not at all or only partially sell products to dairiesor wholesale trading comanies, cf.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Community-supported_agriculture. model. In the following years, dairy farming (which was part of the farm concept from the beginning) was supplemented with cheese dairy. Starting in 2009 with an investment by the author, a new farm shop (in addition to an older small shop at the farm) started in Hamburg, approximately 30 km away from the farm. In 2012, the farm’s structure changed from a civil law partnership German: “Gesellschaft bürgerlichen Rechts”, GbR to a special German form of a limited liability company GmbH & Co. KG, “KG” (= Kommanditgesellschaft, a personal partnership with limited personal liability) in combination with the GmbH (= “Inc.”) as the “personally” liable partner, which itself is a limited liability partnership. This was the initiation and foundation for starting to include more partners in KGs, active field and vegetable farmers and pure financial investors. In parallel, a few more farm shops in Hamburg were opened during the coming years.

Together, these factors enabled the farm to lease increasingly more arable land and pastures, to start a second farm site approximately 20 km away from Kattendorf, close to the small town of Bad Oldesloe, and to buy the core area with the farm buildings in Kattendorf. Currently, the farm operates 450 ha of leased land, 320 of which are fields and land for growing vegetables, and 130 are grasslands for grazing milk cows and cattle (a small area of 3.5 ha is forest). The farm also breeds a special pig race, the Angeln saddleback. In total, 50 milk cows, 15 nurse cows, approximately 150 heads of calves and cattle, and more than 100 heads of pigs are now kept by the farm. In this way, the farm offers practically everything for living, except for eggs and fruit, which are provided to the farm’s shops by partner companies, and bread, which is supplied by a relatively large bakery that is almost fully supplied with the farm’s cereals and which sells its bread everywhere else in North Germany.

To date, the CSA of farms has grown to become one of the largest CSA units in Europe, probably the largest one supplying such an almost complete food portfolio. The CSA is run partially in more than a dozen smaller private groups with their own storage rooms (refilled once per week by the farm) and in its own 7 farm shops as pick-up points, 5 in Hamburg, 1 in Bad Oldesloe and 1 in Kattendorf at the original farm site. The shops are also selling the farm’s products to any bypassing or regular customer. It should not be overlooked that sales of the farm’s products cannot (for German tax laws and agriculture regulations) be run by the farm as a company itself but need to be through a special sales company, which, in this case, is part of the GmbH & Co. KG company construction. This sales KG partnership is owned only partially by the same partners as the farm KG, and one shareholder of the sales KG is not a partner in the farm KG. The GmbH is owned by shareholders who are partners in both KGs. Both the farm and the shops, including the administration, are run by more than 80 people, approximately two-thirds of whom are working part-time, such as 20 or 30 hours per week.

The farm operates a cheese dairy using only its own milk (230,000 liters per year; additionally, approximately 80,000 liters are sold as milk, partially, only directly at the farm, as raw milk). In addition to many varieties of cheese, yogurt, curd cheese, butter and buttermilk are also produced. The necessary steam is mostly generated by a wood gasifier powered by the farm’s own wood taken from 12,51 kilometers of wall hedges around the fields and pastures (which are trimmed down to approximately 20 … 30 cm above the ground every 15 years rotating segment by segment, almost 1 km each year, to collect up to 20 solid cubic meters per year). These trees must be trimmed to provide dense bushes against wind (preventing soil erosion); if they are not trimmed, instead of a bush line, a much less dense line of trees would emerge with open spaces in between, too open for wind and much less suitable for birds, hares and numerous other animal species. The bioenergy provided by the gasifier saves up to 70% of the former fossil gas supply. The farm is planting more wall hedges on fields that had been leased starting only a few years ago and were conventionally farmed until then, when wall hedges had been removed long ago. Conventional farming does not prefer to have wall hedges as they make farming more work-intensive due to the fields being smaller, and due to loss of “productive” area. In the case of the Kattendorf farm, the 12.51 km wall hedges correspond to approximately 2.5 to 3 hectares which conventionally would be judged as “unproductive” or even “counterproductive”, but they are very productive in terms of biodiversity and prevention of soil erosion by wind.

The electricity demand is on average between 10 and 20 kW, with the maximum power demand sometimes reaching 70 kW. The farm generates itself approximately 82,000 kWh per year with its own 100 kW PV plant on two of the farm’s barn roofs. In times, when there is more solar irridiation (maximum effective power up to ~85 kW), the surplus electricity is stored in a 90-kWh battery; after the battery is fully loaded, any further surplus electricity is used by heaters in two hot water tanks for the dairy. The total electricity demand per year is approximately 160,000 kWh; thus, the farm generates approximately half of its electricity demand via PV.

2.2.3. Crop Rotation

The biodiversity and climate protection provided by Kattendorf farming are based on two major pillows: a six-year crop rotation and a highly segmented cropfield structure (further below). We begin by looking at the crop rotation:

First, livestock fodder, which involves the cultivation of clover and alfalfa grass mixtures, is cultivated which is green manure as well. These mixtures of Fabaceae and various grasses constitute the first step in the six-year crop rotation. Fabaceae are able to use atmospheric nitrogen through a symbiotic relationship with rhizobiaceae directly for their growth and that of their grass mixture partners. In addition, after two years of use (with 3–4 harvests per year for feeding the cattle), the Fabaceae/grass mixture leaves approximately 250 kg of nitrogen in the soil for the following crops over the next 2–3 years. In preparation for the fields used for this culture, plowing is performed very shallowly (approximately 4 cm deep) immediately after the last grain harvest. Approximately one week later, a shallow plow furrow (12–15 cm deep) is prepared, immediately followed by rolling with levelling front tools, which produces a smooth, reconsolidated seedbed. This is followed by shallow sowing with a seed drill, whose pressure rollers press the seed down so that it immediately has contact with the residual moisture in the soil. A sowing rate of 2.5 - 3 g per m² is optimal.

In mid-October, a mower is used to cut grains that have fallen during harvesting and taller weeds that compete with the crop. Since these grass/Fabaceae mixtures remain in the field for two years, approximately one-third of the total arable land is used for this crop. Each year, the farmers plow half of this area and resow the same size on other fields so that each year, they have half of the clovergrass areas in the first main year of use and the other half in the second year.

In the third year of crop rotation, they sow a grain with a high nitrogen requirement: wheat on better soils, spelt on medium soils, and winter rye on very sandy soils.

In the fourth year of crop rotation, spelt will be grown. Many people who are intolerant to wheat can tolerate spelt bread without any problems. Additionally, potatoes, which are the most labor-intensive crop, are planted in the fourth year. This process begins with soil preparation, fertilization (with cattle manure), and preparation of the planting material and continues with potato planting, hilling and hoeing two to three times, watering once or twice, mulching the foliage and weeds, and finally harvesting.

In the fifth year of crop rotation, three different varieties of leguminosae (legumes) are grown: field beans, which need to be sown as early and as deep as possible, and beans, which are up to eight centimeters deep and are almost four times deeper than cereals. A second crop in this group is grain peas, either as summer peas alone or as winter peas with triticale as a support crop.

A third crop is blue sweet lupin. Once the content of bitter substances is low enough, they are processed into various foods. Lupins can also be harvested with a combine harvester, usually after field beans.

In the sixth year, various types of grain are grown, with winter rye making up the largest proportion. Another grain of choice is winter barley, which needs to be sown early, requires good fertilization, and is also the first grain to be harvested in summer. Barley is the best grain for pig feed. With increasingly warm and early dry summers, summer barley is a reliable crop because it requires very little water. Oats and A. nuda (naked oat) are also crops for the sixth year.

The farm takes part in a nature conservation program that requires

- 5% of the cropland (15 hectares in this study) to be planted with a diverse mixture of flowers, which remain in place from May 15 to mid-February of the following year and actively promote insect populations while also providing a good shelter and food source for birds in winter.

- Each field was divided into at least three smaller fields, with no area smaller than 2 hectares and no area larger than 5 hectares. In their largest field (over 50 hectares), there are 11 different fields and three flower strips.

To manage these small field sections, digital maps were created, and the tractors and the combined harvester used GPS-controlled driving on the basis of these maps.

The wall hedges surrounding the fields, large areas with high plant, insect and bird species varieties are offered, so the farm area is a haven for biodiversity.

2.2.4. Carbon Storage in Soils - Mechanism

With respect to CO2 capture and storage by photosynthesis, another widely distributed prejudice or misunderstanding exists: Mostly, only the CO2 bound to the above-ground plants is counted (the roots are considered negligible); therefore, the ability to plant fast-growing trees in large monoculture forests is strongly promoted. Also fast-growing forests for conversion of the wood into heat, electricity, fuels and catch the emitted CO2 again with CCS technology, or fast growing macroalgae farms are “en vogue”, we will take a critical look at these in section 4 “Discussion”. It is predominantly overlooked what happens in the soil.

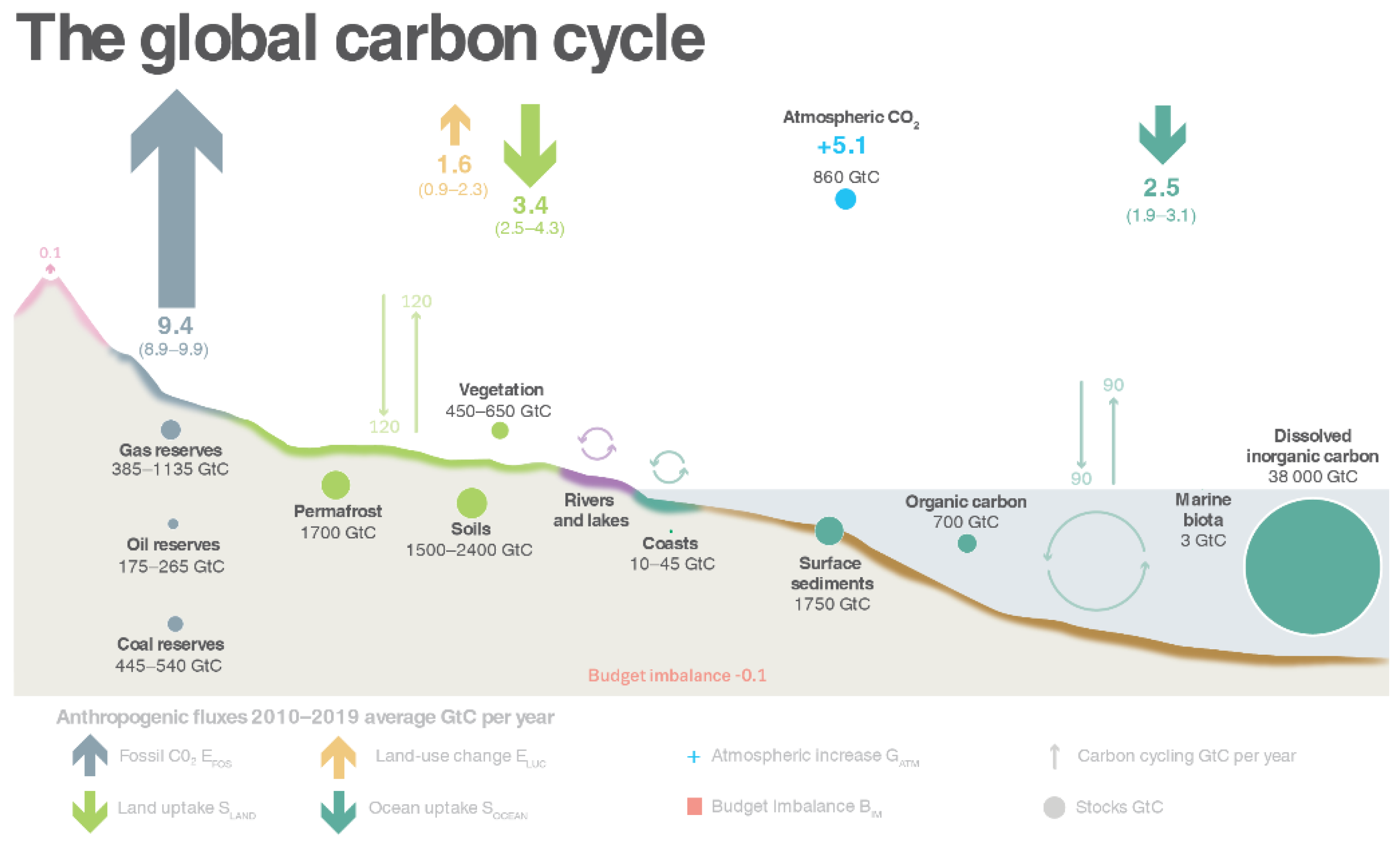

First, as shown in

Figure 3 [20a], much more carbon is stored underground in permafrost (1700 GtC) and in the soil (1500– 2400 GtC) than in the atmosphere (860 GtC) and above ground in plants (450–650 GtC). The ocean contains the largest amount of (inorganically bound) carbon (38000 GtC), and ocean sediments store another significant amount of organically bound C (1750 GtC). In another secondary source [20b], the amount in soil is said to be 2500 GtC, out of which 1550 GtC are organically bound and 950 GtC are either elemental C or inorganically bound, such as in carbonates. This latter source includes 560 GtC that are above-ground bound in plants.

How is it possible that carbon is stored underground in soil? For this purpose, we need to look at the processes occurring above the soil and later underground.

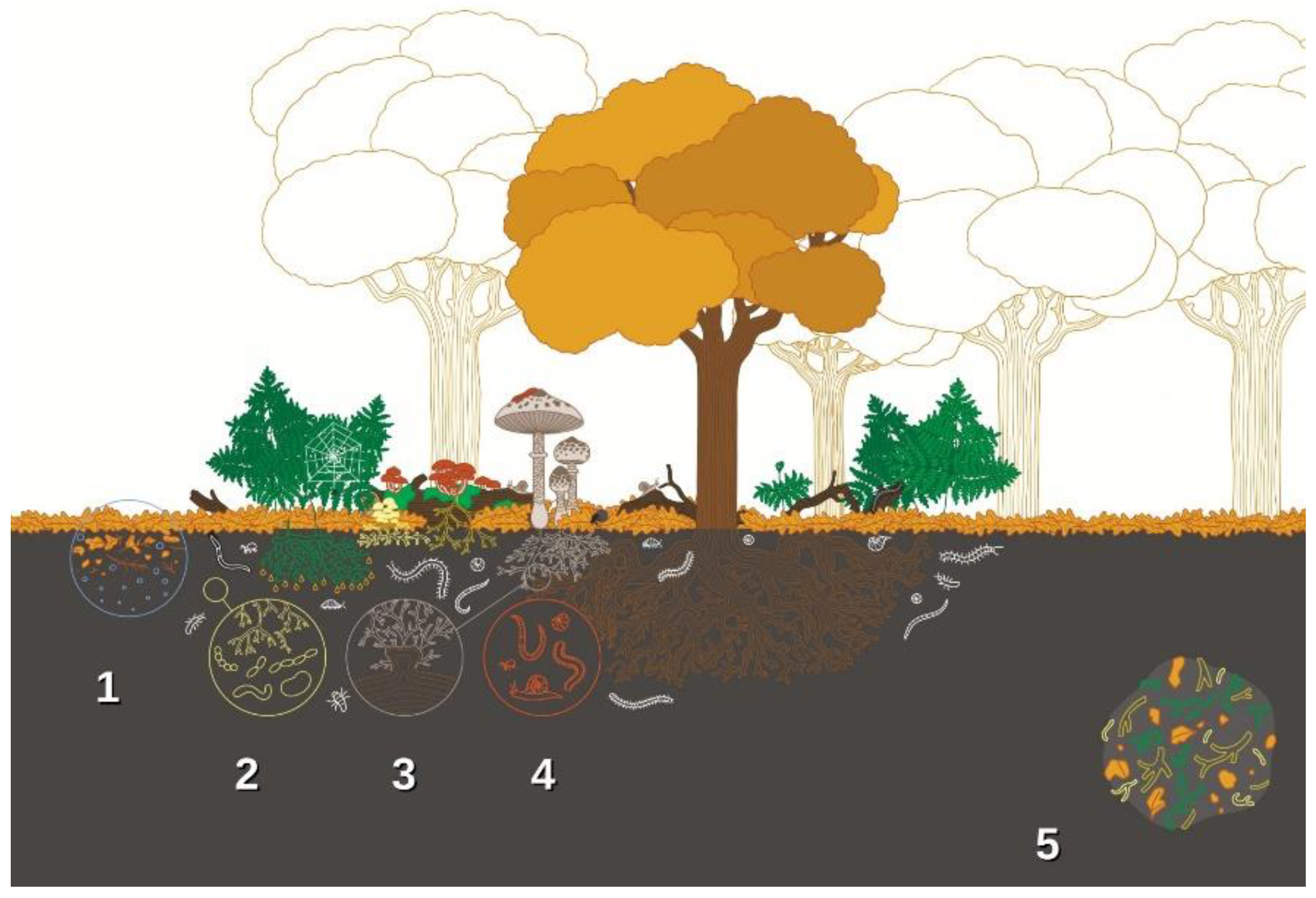

Figure 4 schematically shows what is happening on and within the soil.

An important and eye-opening overview of the role of mycorrhizae (fungal mycelia) is given in [21]. Fungal mycelia form symbiotic partnerships with plants of all kinds (trees, shrubs, grasses) called mycorrhizae. They are associated with the fine roots of plants and receive photosynthesis products (sugars) from the plants. In return, they supply plants with nutrients (such as phosphates, nitrates, and salts) and water. This is basically well known. However, the role of mycorrhizae in transporting carbon into deep soil has been poorly researched. The authors find this “surprising,” given that 75% of carbon is stored underground and that the storage process begins with mycorrhizae. The authors of this publication reported that, on average, between 3% and 13%, depending on the plant/fungal mycelium network, up to 50% of the net carbon produced from photosynthesis is transported into the soil by mycorrhizae. According to their results, this could amount to approximately 13 Gt CO2 (corresponding to approximately 3.5 Gt C) for the different types of mycorrhizae.

On the other hand, it does not involve mycorrhizae alone but rather involves a total of four different mechanisms in the soil that ensure that carbon is stored [22]. Earthworms, snails, beetles, and rain transport them into upper soil layers; some dead plant remains are also emitted back into the atmosphere as CO2 (1). Microorganisms, mainly bacteria and nonsymbiotic fungi, feed on dead plant remains (2). Mycorrhizae promote the storage of carbon compounds obtained from decomposed plant remains and transport them to other plants as nutrients (3). All kinds of soil organisms eat plant debris and excrete waste products such as feces, which contain a wide variety of carbon compounds (4). These compounds are stabilized and stored in the soil by three different mechanisms: hard-to-degrade compounds such as tannins and lignin accumulate; aggregates are formed that protect these and other (more easily degradable) substances from further degradation by microorganisms; finally, complexes of low-molecular-weight compounds with clays form in deeper layers of the earth, after which these substances remain in the soil for centuries and millennia, a mechanism that has been little noticed or even unrecognized until now (5).

These mechanisms can work only if the soils are natural and full of life. This is not the case in monoculture forests with little or no internal structure (clearings, undergrowth, damp depressions, etc.) and not in intensively farmed fields and pastures treated with mineral fertilizers and pesticides. Conventional (quasi-industrial) agriculture is therefore known to be a massive CO2 emitter and contributes massively, if not as the main responsible party, to the biodiversity crisis [19].

If soil life above and under ground is allowed and supported, which requires diverse plant societies on the ground inviting animals of all kinds to live there from these plants, then numerous earthworms, snails, beetles and the kind will be active and will start what the fungal mycelia and microbes can jointly perform, with the result of carbon being stored underground in massive amounts for a very long time.

In addition to what is actually stored in the soil, renaturalized mixed forests with diverse structures, including clearings, could double the CO2 capture and storage capacity. This means that 226 GtC could be additionally stored, equivalent to approximately 20 times what is actually emitted per year, if this study [23] can be taken seriously. If many more wild animals are allowed to roam renaturalized forests and graze in forest clearings, the storage capacity of these ecosystems can be more than doubled.[24]

The same processes would work on agricultural land; however, the use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers essentially kills all the necessary varieties of species capable of running these complex interconnected processes. For example, in Germany, approximately 50% of the area is in agricultural use (cropland and grassland), whereas (mostly monocultural age-class) forests account for almost 30%, and the urban/infrastructure area is close to 15%.[25] For the whole European Union (EU), the rounded figures are 39% (agriculture) and 35% (forests).[26] On a global scale, 44% of the habitable land is used for agriculture (with cropland one-third and grassland two-thirds), and 38% is covered by forests.[27] This shows how important the agricultural lands are for climate and biodiversity, considering that conventionally farmed land is actually a strong net CO2 emitter and that it is the number one cause for species decline because of the intensive use of pesticides [5.1] and chemical fertilizers, in addition to the partially large fields covered with one crop and often no or very poor crop rotation.[19]

The same carbon storage mechanism described above operates on organically farmed arable land and on wild but grazed meadows deep in their living soils, where thick humus layers allow active and diverse beetle and insect life and where no chemical fertilizers or pesticides are used. Hence, the large-scale conversion of agriculture to organic farming, on the one hand, and the conversion of forests to near-natural forests, on the other hand, could result in a large increase in CO2 storage potential. (Other very important ecosystems are moors and wetlands, which cannot be discussed here, too; they offer even more carbon storage potential per hectare than forests do, and despite their minimal area portion compared with forests and agriculture, they can capture and store even double as much CO2 as forests in absolute figures despite covering only 1% of the land area. cf. chapter 8, p. 260 ff [11])

Similarly, the planting of many hundreds (if not thousands) of kilometers of field hedges (wall hedges) can contribute to both biodiversity and climate stabilization. In Schleswig-Holstein, such hedge lines have been protected for centuries, but in other federal states, they were largely destroyed during land consolidation. Now, their replanting is partially financially supported. The new EU law on renaturation [28], asking for renaturalization of 20% of the land and sea area, can also contribute to both objectives if it is consistently implemented in the countries and regions of the EU (which, unfortunately, is far from guaranteed).

As mentioned above, forests can store twice as much CO2 as before if they are allowed to grow naturally to permanent-cover forests and are populated by wild animals. However, if intensive agriculture (currently a CO2 emitter) is converted to organic farming, an additional 1.6 times (50% of land area vs. 31% of forests) greater than what near-natural forests would achieve in CO2 storage could be achieved on agricultural land. This number would be 6 to 32 times greater than what mankind currently emits in CO2. Moreover, at the same time, this would address the biodiversity crisis literally at its roots.

2.2.5. Methane Emission Issues Associated with Milk Production vs. CO2 Storage While Grazing

More specifically, we look at pastures where milk cows and cattle graze. Critically commenting on dairy farming has become popular among environmentally concerned people. Cows are often labeled “climate killers” in media because of their methane emissions. Many people want to eat in a climate-friendly way and therefore drink oat “milk” (more correctly, oat drinks) and do not eat cheese manufactured from cow milk. However, like many simple equations in ecology, this simplistic view of “cows = climate killers” is untenable. Upon closer inspection, it proves to be at best a one-dimensional (and rather fundamentally flawed) view, one that is not appropriate for complex systems and processes. Therefore, one needs to take a step back:

Ruminants have existed on Earth since the Eocene epoch. Without the taxonomy of the species, giraffes, musk oxen, wildebeests, deer, roe deer, moose, ibex, cattle, sheep, and goats are given as examples; kangaroos, camels, and llamas are also ruminants. Before Europeans arrived in North America and took over the land, approximately 50 million bison [29] lived in the prairies there (which are grasslands, i.e., very large pastures, enormous wild meadows with mixed grass species). In addition, they were by no means the only ruminants roaming the prairies and forests. The situation was similar (and in some cases still is) in the savannahs of Africa, where even today, there are still approximately 1.5 million wildebeests. Most likely, in populations not quite as large as those of bisons in North America (population estimates are not yet possible), ruminants roamed Europe, such as musk oxen, aurochs [30], which grazed and ruminated throughout Eurasia and North Africa since when glaciers retired with the end of the ice age. They were later domesticated into modern cattle, whereas the original wild species soon became extinct. There were also steppe bisons, as well as wisents, which had developed from hybrids between aurochs and steppe bisons [31], but these bisons were also becoming increasingly less numerous. Elk and deer, roe deer and reindeer also lived there. It is becoming increasingly clear that Central Europe was not simply covered by dense, dark forest but by a park-like landscape in which richly structured forests alternated with grassy clearings and larger grasslands, apart from the actual steppe landscapes that we still find in Europe today.[32] There grazed ruminants, wild horses and forest elephants kept forests open and emitted methane.

All ruminants have always been landscape designers: They eat and digest plants, keep the forests open, open up the soil and thus repeatedly prepare new small and large habitats for many other animals and even more plant species. There are approximately 2.5 million roe deer in Germany today, plus 200,000 red deer and additional fallow deer. cf.

https://www.deutschewildtierstiftung.de/wildtiere/reh By way of comparison, there are about 10 million cattle in Germany. The per capita meat consumption in developed countries is too high from a “net zero” standpoint of view (and from a health preserverance viewpoint as well), and too much of it is raised in former rainforest areas. However, this is not the topic to be discussed in this paper. Rather, here, it is necessary to address the fundamental question: Are cows climate killers?

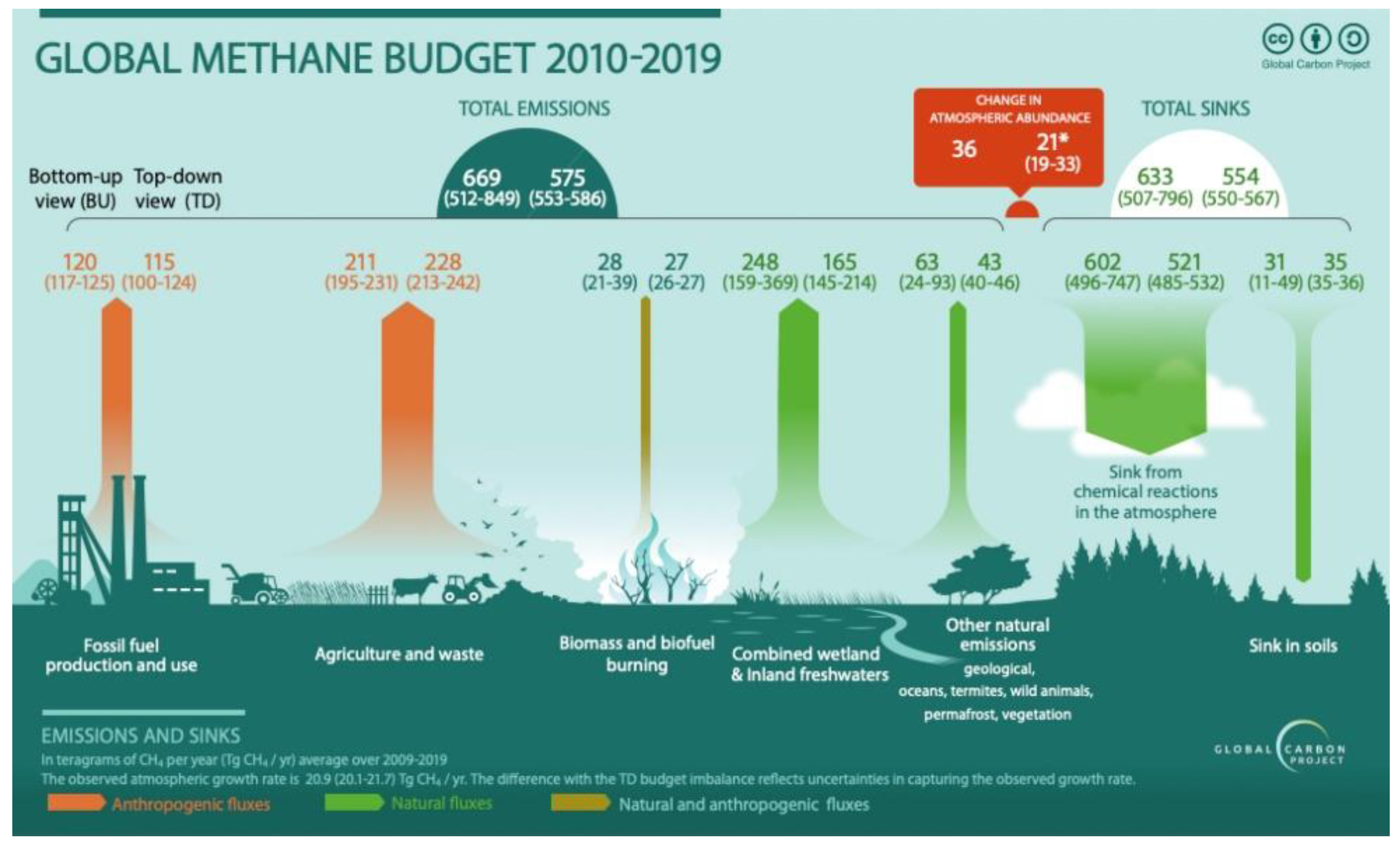

The annual total global methane emissions are estimated to be between 575 and 669 Mt/year.[33] Most of this is offset by the quantities that are decomposed in the atmosphere through (photo)chemical reactions (approximately 561 Mt/year) and those that are stored and decomposed in the soil (approximately 33 Mt/year). Therefore, approximately 21 to 36 Mt/year remain in the atmosphere, as shown in

Figure 5 [34].

Enteric fermentation in agriculture represents approximately 30–32% of the total anthropogenic CH

4 emissions [35]. To see what this means in terms of “net zero agriculture,” one must look into the details per cow and liter milk and per hectare pasture. It is not easy to obtain clear and reliable figures about methane emissions per cow and/or per liter of milk. Detailed data were given by S. Engelke et al. [36]. These findings indicate that if cows (held in stables all the time) are fed more energy-containing food, they will emit up to 700 liters of CH

4 per day. Hence, these cows, which are not outside for grazing, each emit 165 kg CH

4 per year. 365 days x 700 l/day x 0.6443 g/l CH4 = 165 kg/cow, year; the value 0.6443 was calculated using wolframalpha’s web site:

https://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=mass+of+1+l+methane+at+300+K+and+1+bar

This contrasts with cows, which were held outside and could graze all day starting in spring until mid-autumn on pastures that offered a variety of grass varieties, so we can assume that these cows were held under conditions comparable to those at the Kattendorf farm. This paper [37] shows quite different results compared with [36]: Grazing cows emit 8 to 10 g CH

4 per liter of milk, which—taking the average Kattendorf cow’s yearly milk delivery—for 6,000 liters of milk per year are 54 kg per year, a reduction by two-thirds compared with the cows receiving concentrated feed in stables. For the 2.5 cows per hectare at Kattendorf farm (see below), approximately 15,000 liters of milk will be delivered; consequently, 135 kg of CH

4 per hectare, which is said to have a CO

2 greenhouse equivalent of 28

https://www.epa.gov/energy/greenhouse-gas-equivalencies-calculator, i.e., equivalent to 3.78 tons of CO

2, will be produced.

However, as shown below, such a biologically managed hectare of pasture will store approximately 12 t of CO2 per year deep in its soil. Therefore, biological dairy farming benefitting from grazing cows and generating forage mixtures, such as the Kattendorf farm, results in net negative CO2 emissions of approximately 8 t/ha annually after deducting the methane emissions (greenhouse gas equivalents) from cows.

We had already taken a look back and seen that cows are not the only ruminants that emit methane; many other wild and domesticated species (including sheep and goats) do so too, and they have been around for two or three dozen million years. Therefore, methane has always been emitted—and in no small quantities. The methane cycle has existed on Earth for billions of years, but much about it is still unknown.[38] Certain microbes produce methane, others live off it, and methane is oxidatively broken down in the atmosphere into CO2 and H2O. There is no question that the CH4 concentration has increased since the beginning of industrialization. There is also no question that fossil oil and gas extraction and (industrial, conventional chemical) agriculture contribute a large portion of this development.

However, what is known about cattle in particular and ruminants in general, especially when pastures are extensively used, contradicts the much too generalized and completely undifferentiated “cows = climate killers” narrative. Even back then, grazing ruminants (together with nonruminant wild horses, incidentally) ensured that grasslands developed and persisted for long periods, which in turn led to humus formation and ultimately the final storage of carbon in the soil, with the help of the mechanisms described above. However, there is much more CO2/CH4 fixation in the soil than “only” when cows are grazing [39]:

After a cow has dropped a cowpat, the first dung flies arrive within minutes, followed shortly afterwards by dung beetles. Eggs are laid, the dung beetles feed on the cow dung, and an increasing number of different flies and beetles appear. The holy pill roller (found in the Mediterranean region and Africa) forms a ball out of the dung, which rolls away and buries, and the female lays an egg in it. Central European dung beetle species, which are related to the former, also use cow dung and horse manure. Dung beetles dig deep tunnels to store the dung in the ground for their own use. Now, the turn of the earthworms contributes to the processes mentioned above.

This extensively used pasture is very different from a hay meadow, which is chemically fertilized and kept free of “undesirable” weeds, which are mowed several times in spring and summer. The latter is essentially a monoculture of the fastest and densest regrowing grasses (good for hay yield), but when used as pasture close to natural conditions, it is a haven of biodiversity, humus formation, and carbon storage.

J. Buse reported the following [40]: “This means that a [single] 600 kg cow produces over eleven tons of manure on pasture land in the course of a year. This is used by 120 kg of insect larvae,” i.e., over the course of a year, one cow provides the basis for the emergence and life of insects with a total weight of one-fifth of the cow’s weight. A single cowpat can contain up to 4,000 individual insects, together with animals from the soil, including several hundred different species. In addition, countless flies and butterflies visit cow dung for a short period of time. However, this is only the case if the cow is not in the barn, as is unfortunately the case for the vast majority of cows today, but is out grazing on a pasture that itself is covered with many different grass and plant species.

The dung of other grazing animals, such as sheep, goats, or horses, is used and processed in a similar way, as is, of course, that of deer and roe deer when they are able to leave the forests and graze in open grasslands. The insects are followed by numerous bird species and individuals.

According to figures from the Thünen Institute [41], 2.22 tons of carbon can be stored per hectare per year on grazed grassland. This corresponds to 8.15 tons of CO2 removed annually from the atmosphere. No distinction was made here between organically and conventionally farmed grasslands, but the figures for the former are very likely to be significantly higher by at least 50%, i.e., approximately 12 t CO2/ha,year are captured and stored. Conventional agriculture, on the other hand, shows an annual (!) loss of 0.2 tons of carbon. A comparison of the storage of these 12 tons per hectare of CO2 with the energy required for direct air capture (DAC), cf. above, reveals that nine million kJ of primary energy per ton of CO2 is required, i.e., 9 GJ. One (1) hectare of grazed grassland therefore saves 108 GJ of primary energy per year, which would be needed if 12 tons of CO2 would be captured via DAC (or if corrected by the CO2 equivalents of CH4: 72 GJ).

However, a biopasture not only stores CO2 but also delivers meat and milk and creates and preserves biodiversity. At the Kattendorf farm, there are 2.5 dairy cows per hectare in total 50 milk cows plus 15 nurse cows, and approximately 150 heads cattle/calves, each of which (fed exclusively on home-grown feed and fresh grass) produces an average of approximately 6,000 liters of milk per year. The 2.5 cows per hectare produce a corresponding amount of milk: approximately 15,000 liters per year, in addition to CO2 storage and providing nurseries and food for clouds of insects (2.5*120 kg = 300 kg of insect larvae per year). A single hectare achieves all this in addition to saving 108 GJ (or if corrected by the CO2 equivalents of CH4: 72 GJ) of primary energy necessary for DAC, and this hectare avoids all the collateral damage caused by the DAC described above. One only has to extrapolate the figures to Germany’s or the world’s farms’ pastures to see that grazed grassland could become a DAC method with much more storage potential than anything planned for industrial DAC (and this with virtually no energy input) – if, but only of biologically managed. At the same time, it promotes biodiversity and produces healthy food.

2.2.6. Organic Farming and Carbon Content in Soil

At the 2015 Climate Change Conference in Paris, the hosts launched a “4-per-1000” initiative, which Germany has joined.[42] This is based on the realization that if just 4 parts per thousand more humus are formed on all agricultural land worldwide, these soils could store the entire amount of CO2 currently emitted and store it in deeper soil layers.

As Kattendorf Farm has gradually taken over an increasing amount of farmland and pasture that was originally conventionally farmed, it has created far more than four parts per thousand additional humus. Kattendorf Farm’s humus content is at about 4.5%, and humus can visually be found down to 35 cm deep (that’s not the maxum depth of organic matter in soil which goes much deeper). On the other hand, the humus content in the farmland of industrial agricultural operations is mostly less than 1% and decreases annually: 0.2 tons of pure organic carbon are lost per hectare of conventional farmland each year, whereas the Kattendorf farm’s soil is full of life, is visible to the naked eye and continuously adds more humus.

The strong humus formation in organically managed soils is due to the use of manure instead of mineral fertilizers and to the 2 years of green fertilization in the crop rotation plan. Notably, the soil only is only worked very shallowly and is not deeply dug over; the 6-year crop rotation system, which alternates between humus- and nutrient-depleted crops and green manure and nitrogen-fixing plants, is key to success. While conventional agriculture causes humus losses of a few percentage points per year, the humus content of organically farmed soils increases by several percent annually. [43]

In addition, with respect to climate change, humus is extremely important and powerful in preserving water. In 2018/2019, Germany, especially North Germany, experienced very severe drought phases starting in April and May, ending only in September/October. Kattendorf Farm has experienced serious crop losses, but “only” between 40% and 70% losses, depending on the field and crop type. On none of the fields was complete crop loss to suffer—while many conventional farmers had up to 100% losses on their fields.

The EU’s support measures under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) are a consequence of the “4 per 1000 initiative” mentioned above. According to the CAP eco-Regulation 533, grassland areas are now subsidized with a certain amount per hectare if they contain at least four species from a regionally varying list of characteristic species, with at least three specimens of each species at a distance of 10 meters from each other. In 2023, Kattendorfer Hof participated for the first time in this subsidy program and subsequently analyzed various pastures. The results of two pastures are listed here as examples: at least 58 different species were found, 28 of which are included in the Schleswig–Holstein list of characteristic species according to the CAP Organic Regulation 5; this list comprises 44 characteristic species. Twenty-eight of the 44 characteristic species were found on only these two pastures.

We can conclude that only if agricultural procedures are adapted to natural mechanisms can the role of agriculture in exacerbating biodiversity and climate crises be improved and even reversed. This means that no pesticides, no synthetic fertilizers, but rather fertilization via the use of animal excrement in a type of circular agriculture involving a 5-- to 7-year crop rotation between nutrient-depleted and soil-recovering plants.