Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Based on the recovered software architectures of existing research software [3], we show that genetic algorithms allow to generate recommendations for restructuring this research software.

- To evaluate these recommendations for restructuring the ESMs, we collected feedback from domain experts who are involved in climate research as research software engineers. This feedback is also used for a guided, interactive optimization process.

2. Our Application Domain: Earth System Models

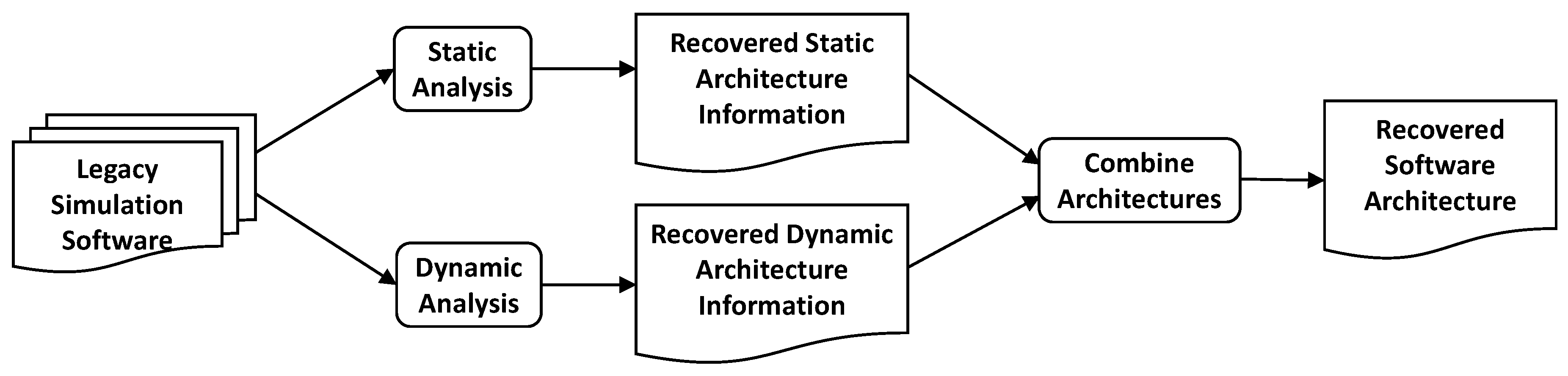

3. Reverse Engineering the Software Architecture

4. Genetic Optimization to Generate Restructuring Recommendations

4.1. Genetic Algorithms for Multi-Objective Optimization

4.2. Software Quality Metrics as Fitness Functions

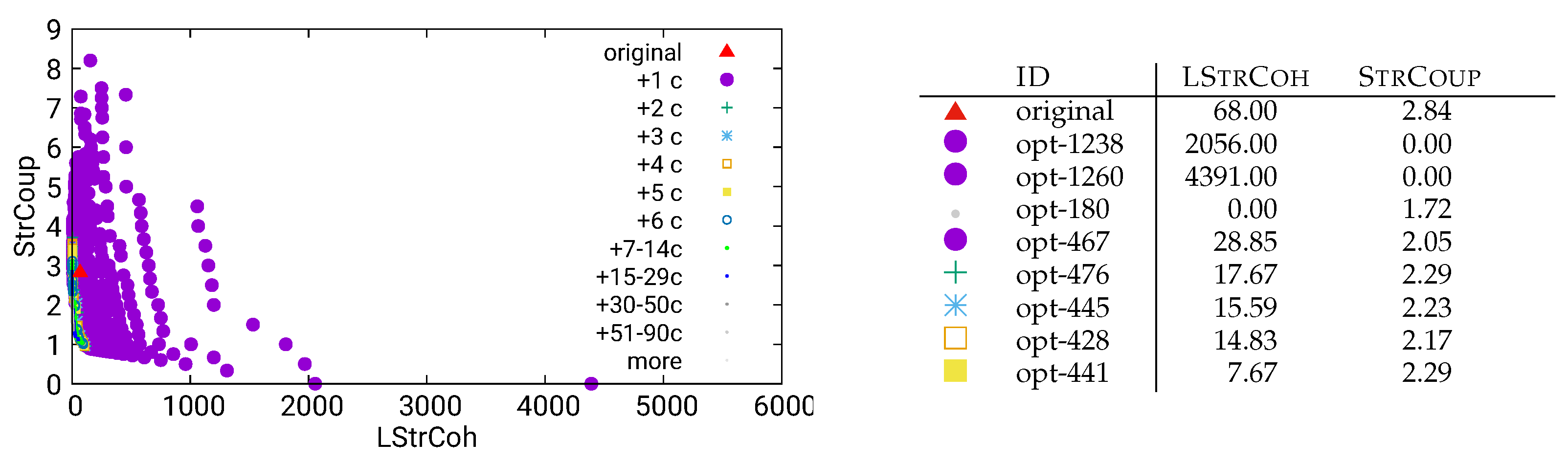

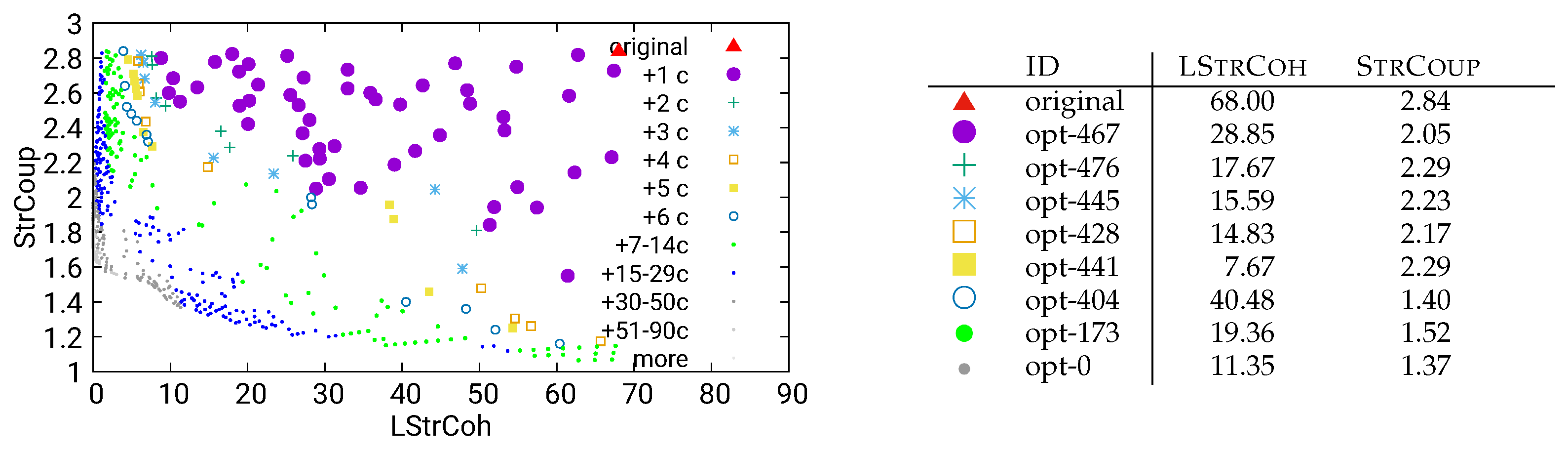

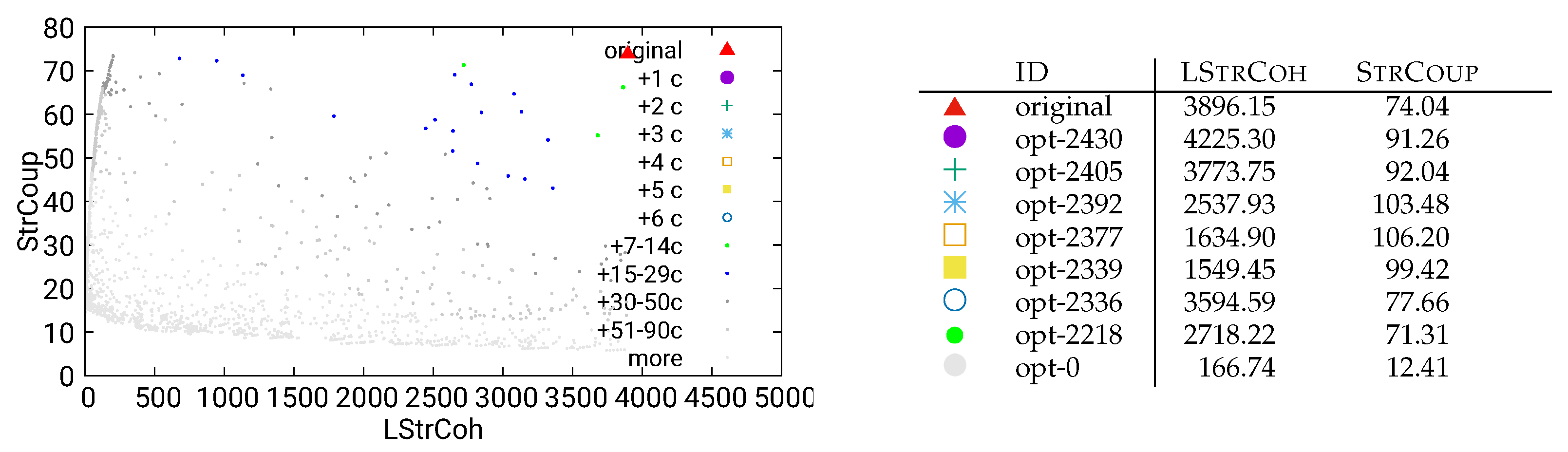

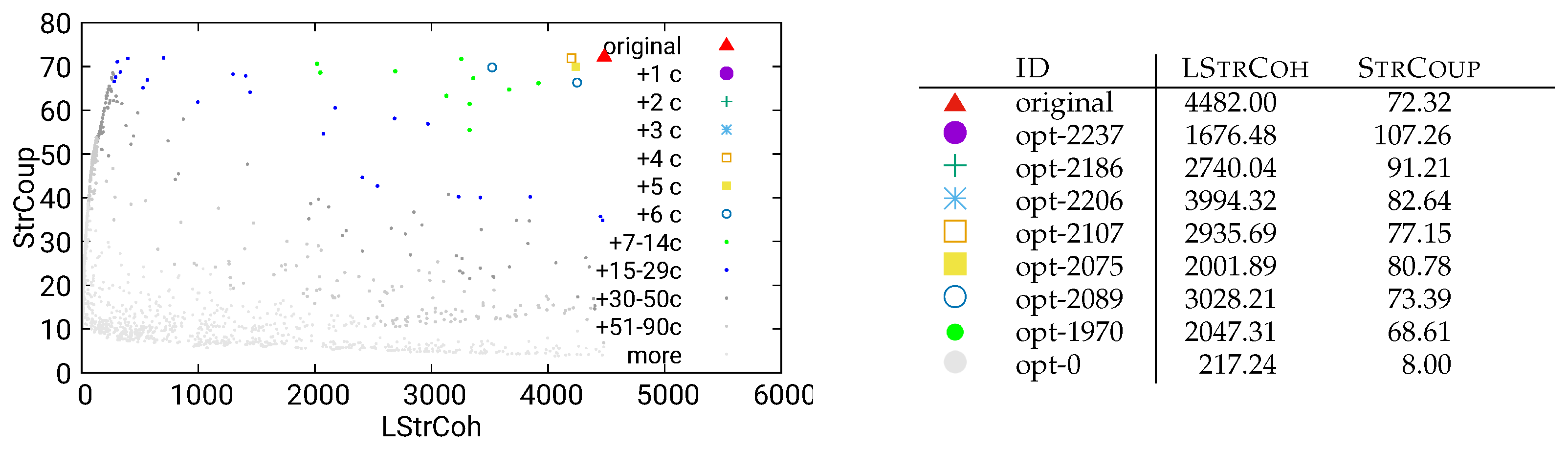

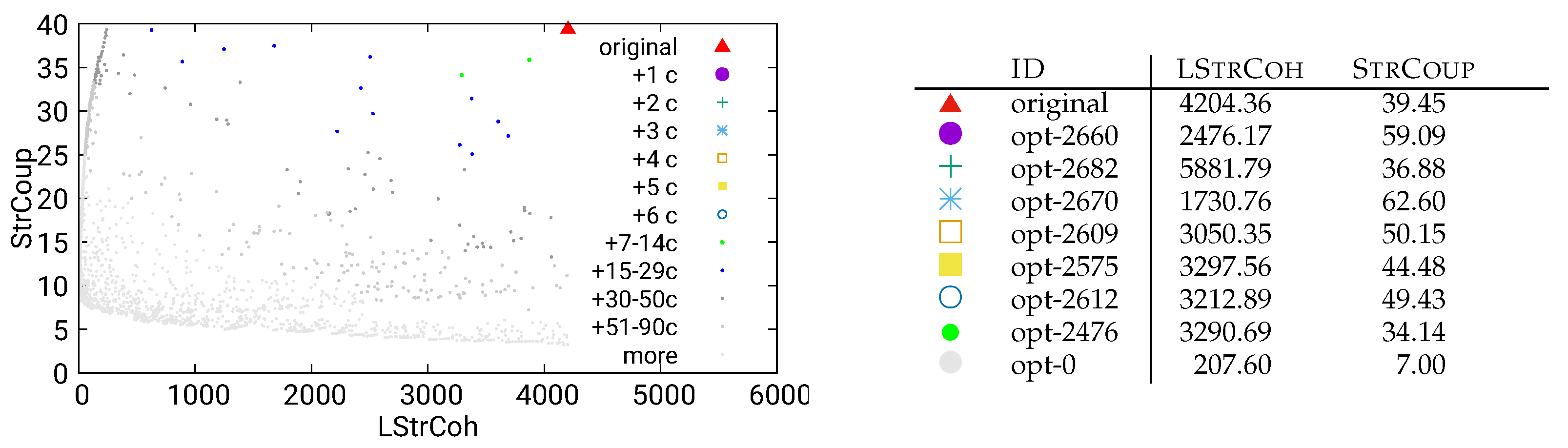

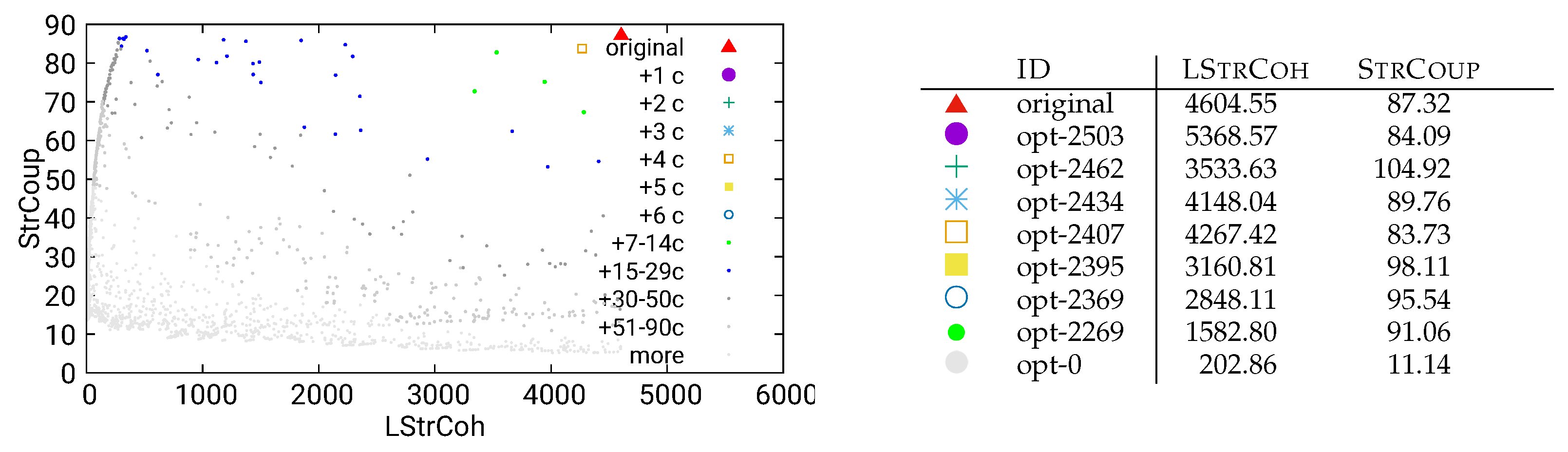

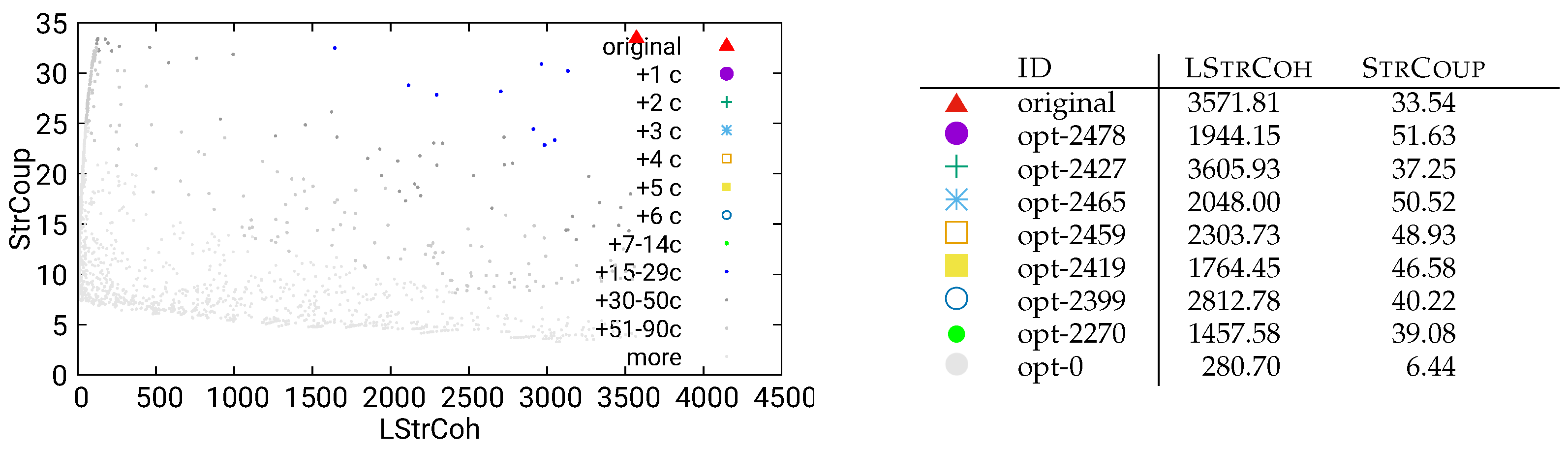

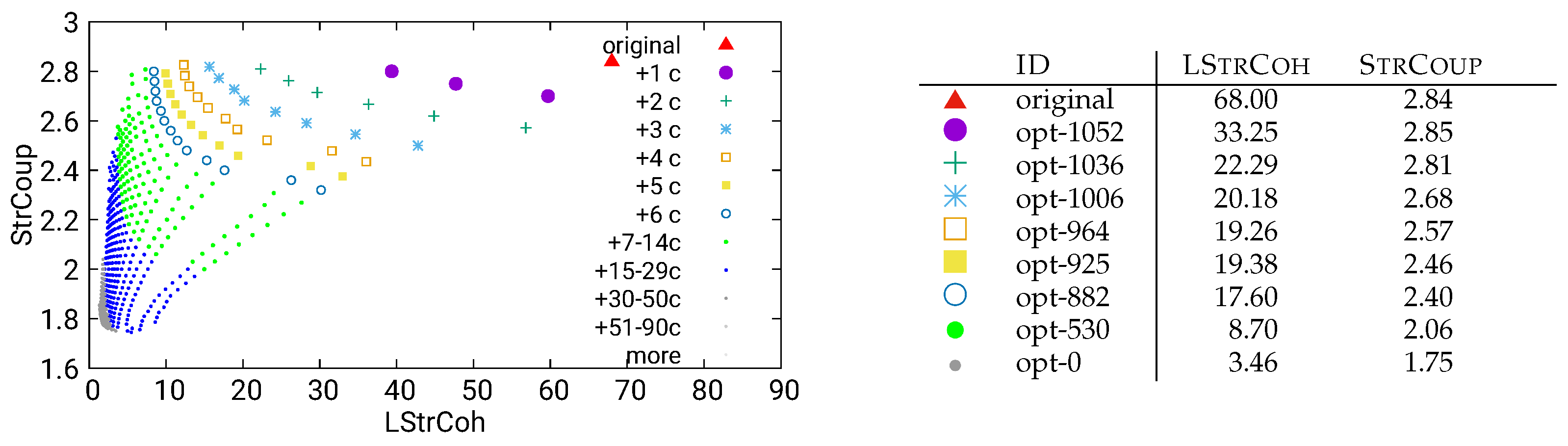

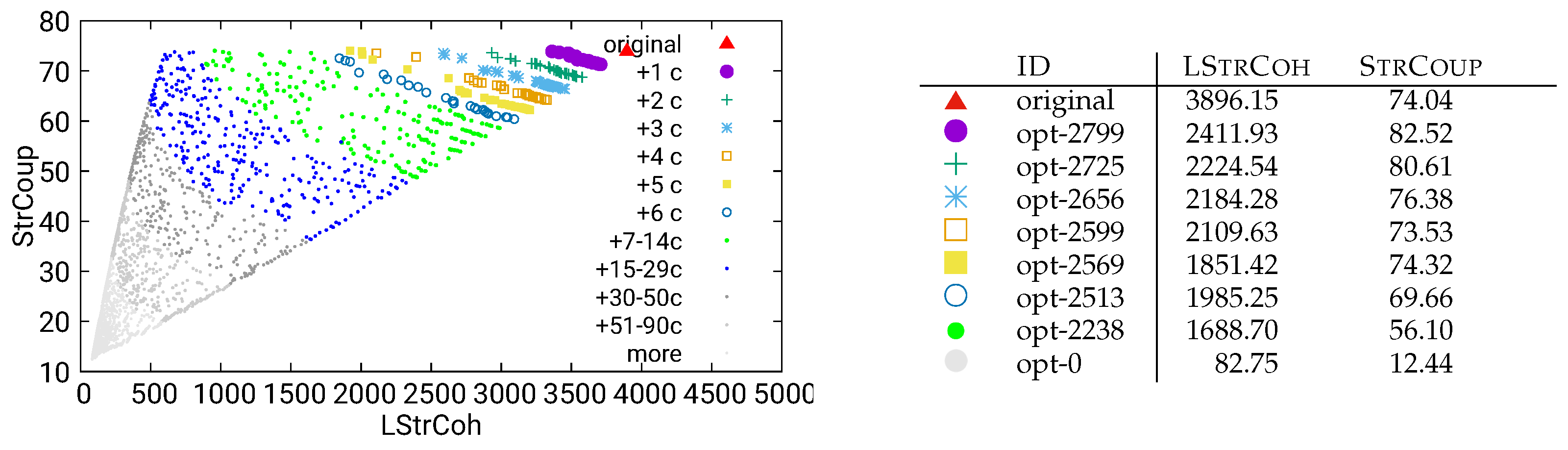

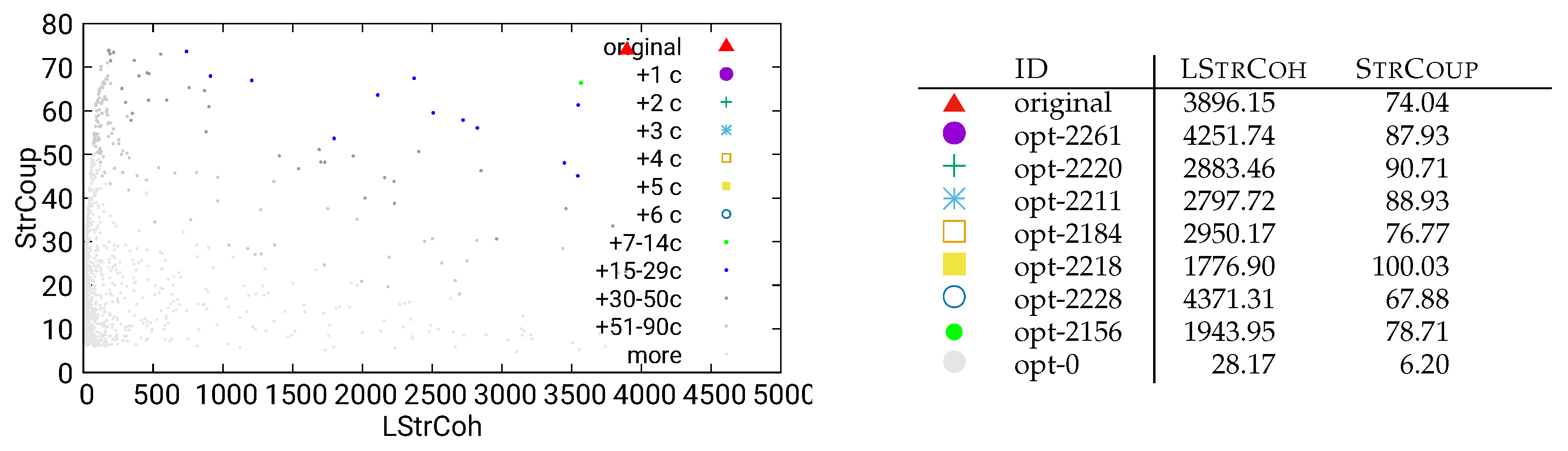

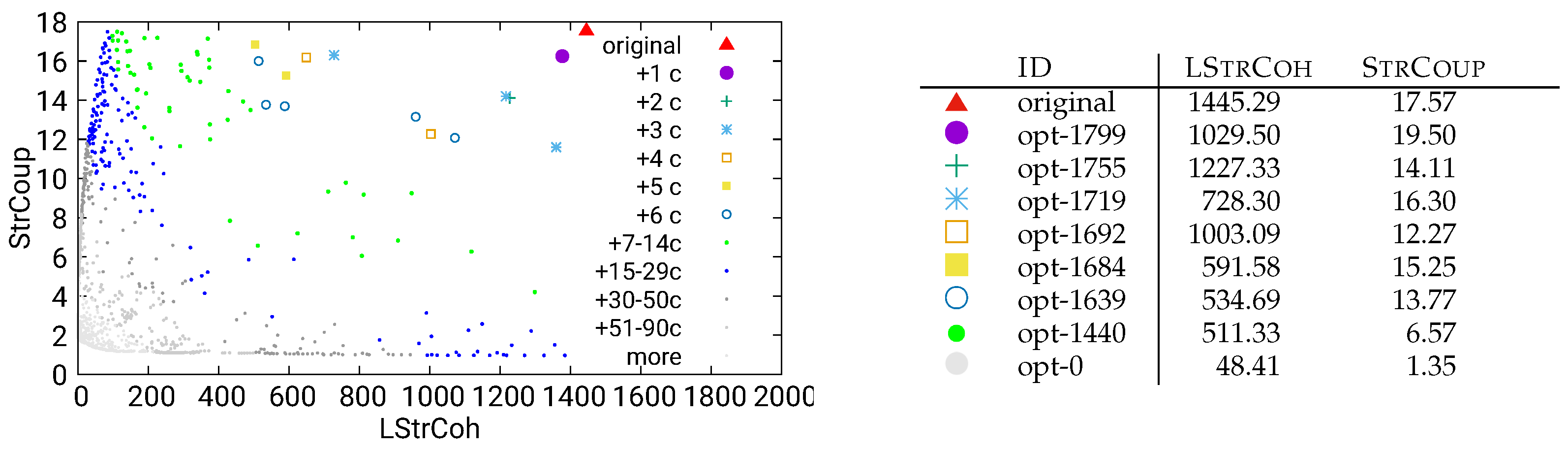

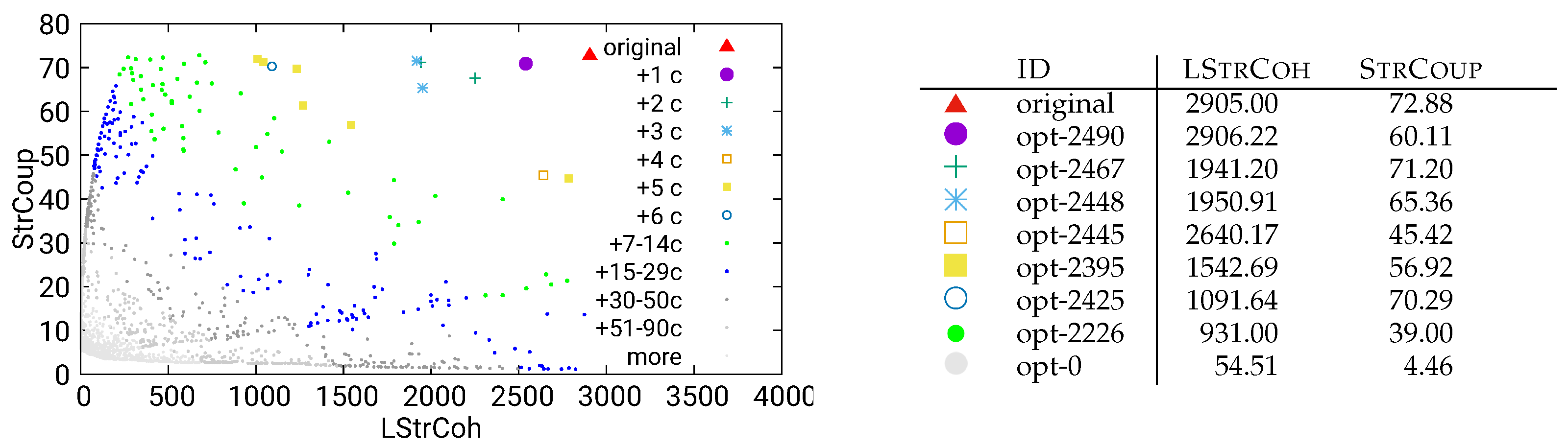

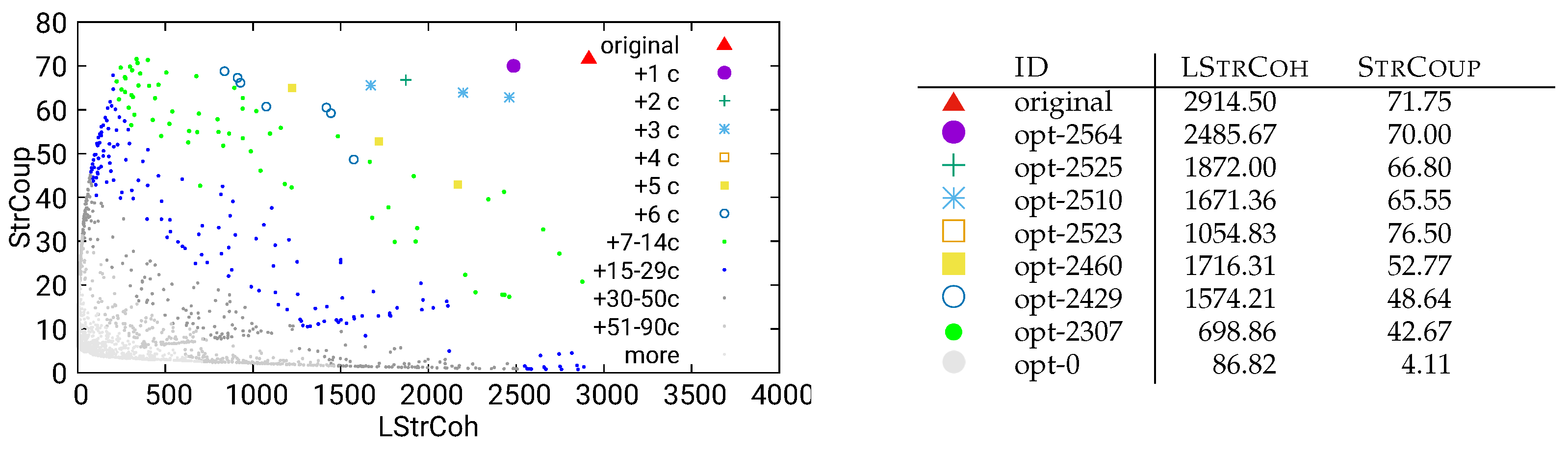

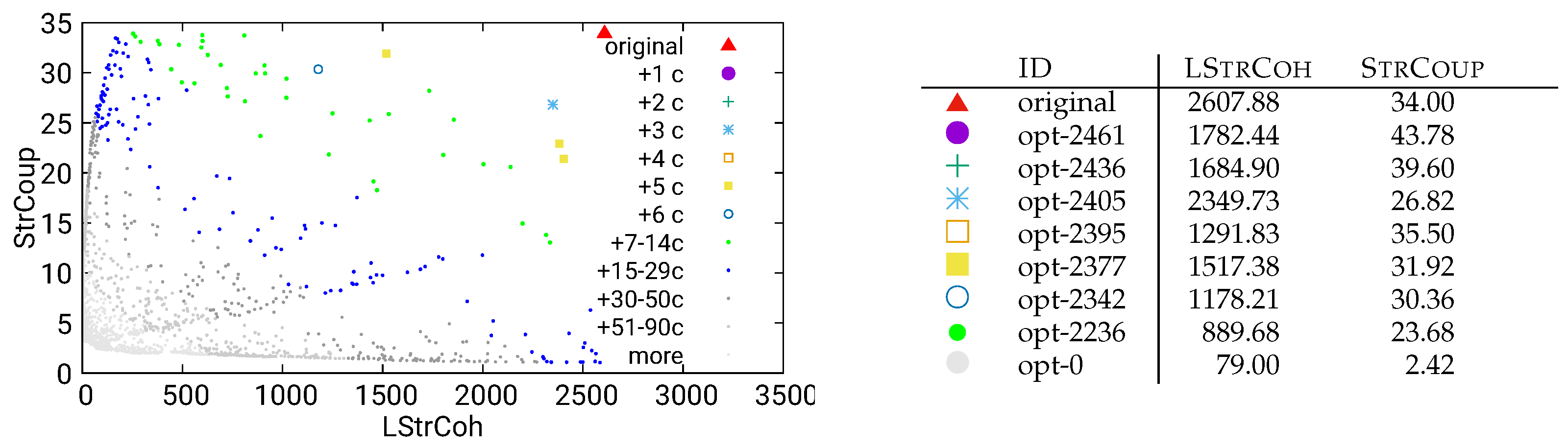

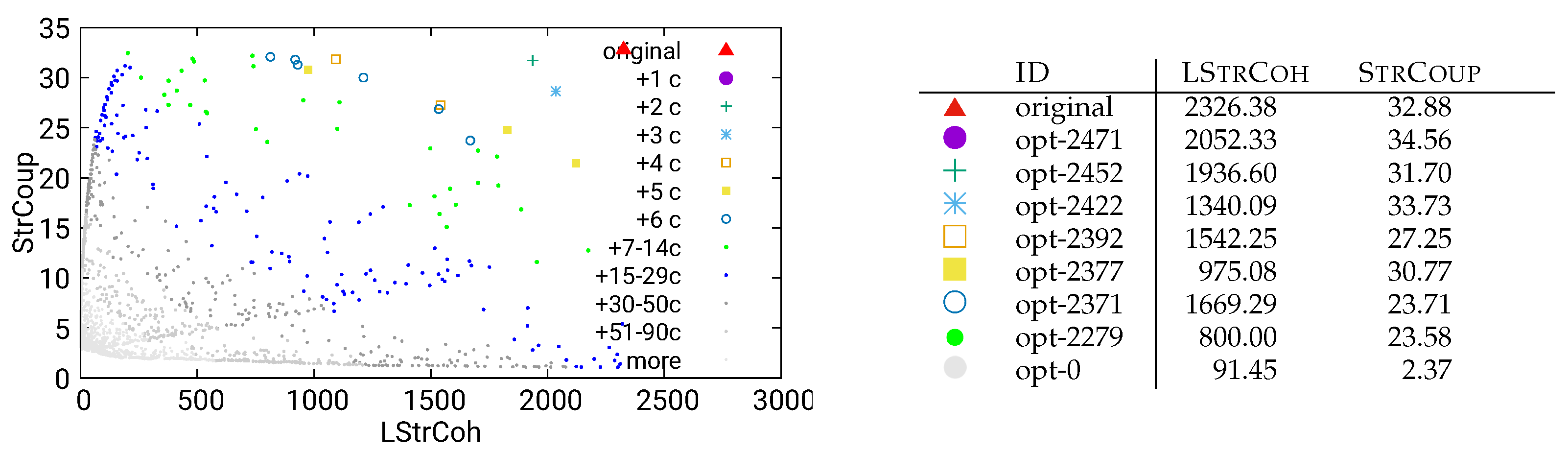

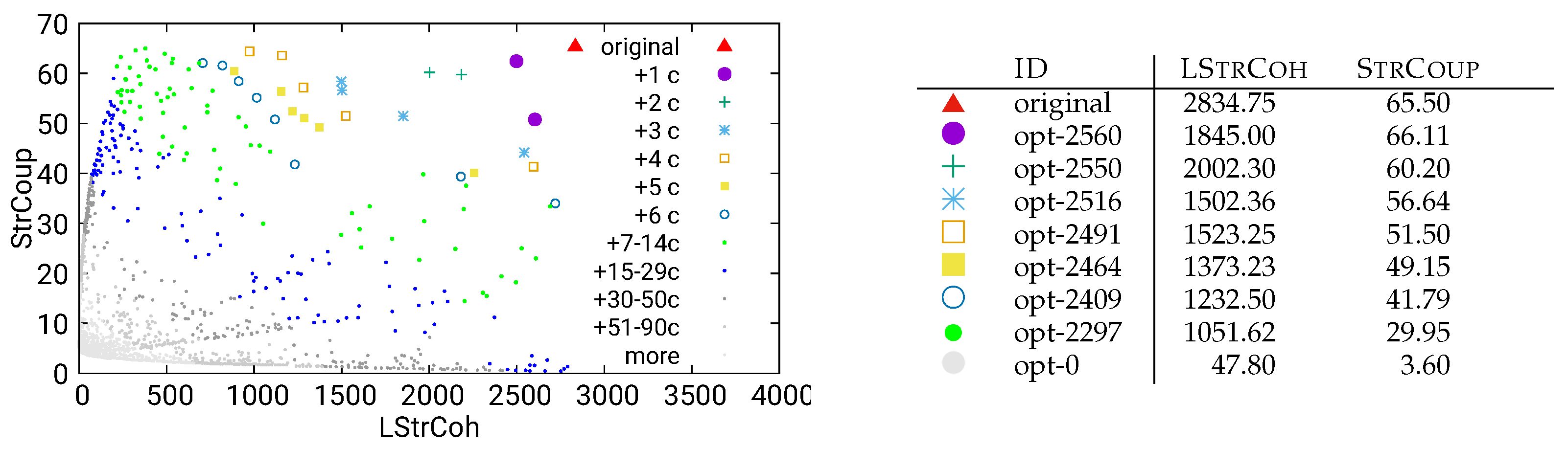

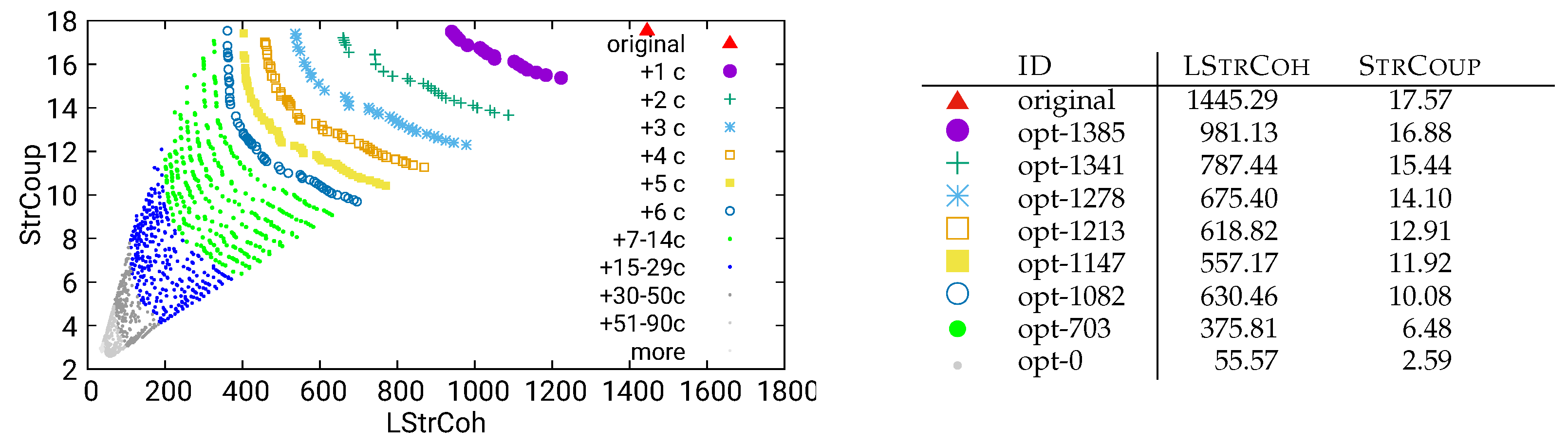

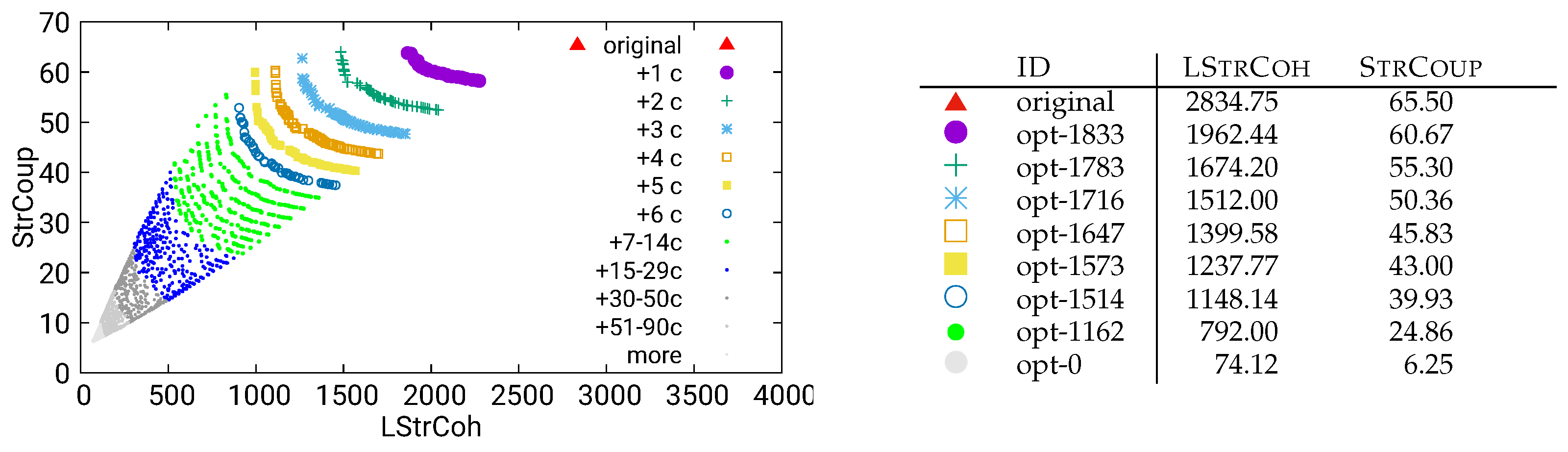

- StrCoup:

- Structural coupling is defined as the average in/out degree of components, i.e., the average number of edges connecting a program unit in the current component with a program unit in another component,

- LStrCoh:

- Lack of structural cohesion is defined as the average number of pairs of unrelated units in a component, i.e., the number of pairs where both u and v are program units, and there is no edge connecting u and v in the coupling graph.

5. Optimization of MITgcm Global Ocean

5.1. Unguided Optimization

.

.- The modularization opt-1238 achieves a coupling degree of zero, at the price of very low cohesion (recall that LStrCoh measures the lack of cohesion, so high values indicate low cohesion). Manual inspection of this modularization shows that opt-1238 merges components to obtain a modularization that consists of two unrelated components (and hence obtains coupling degree zero).

- An even more extreme modularization is opt-1260, which merges all components into a single one–with the “benefit” of fewer components, but at the price of a very low cohesion.

- A third “extreme” modularization is opt-180, which achieves full cohesion (i.e., zero lack of cohesion) while still improving the coupling value over the original modularization (1.72 instead of 2.84). However, a manual inspection of this solution shows that it distributes 96 units into 83 components, which are then mostly one-element components. Such components are cohesive, but obviously this is not a good way to structure a software system.

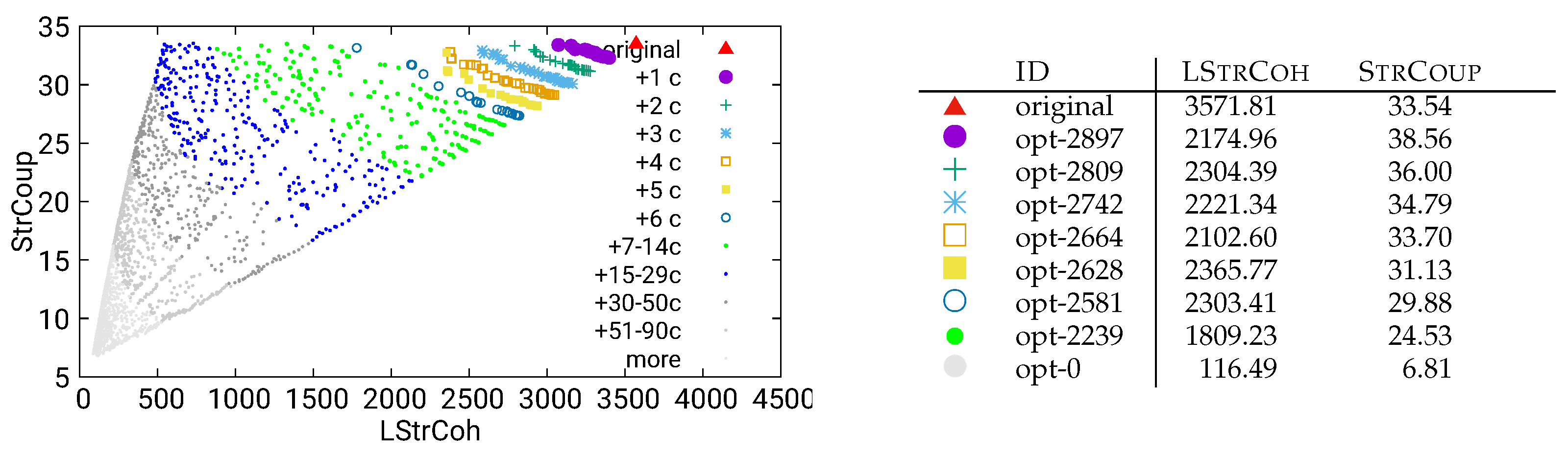

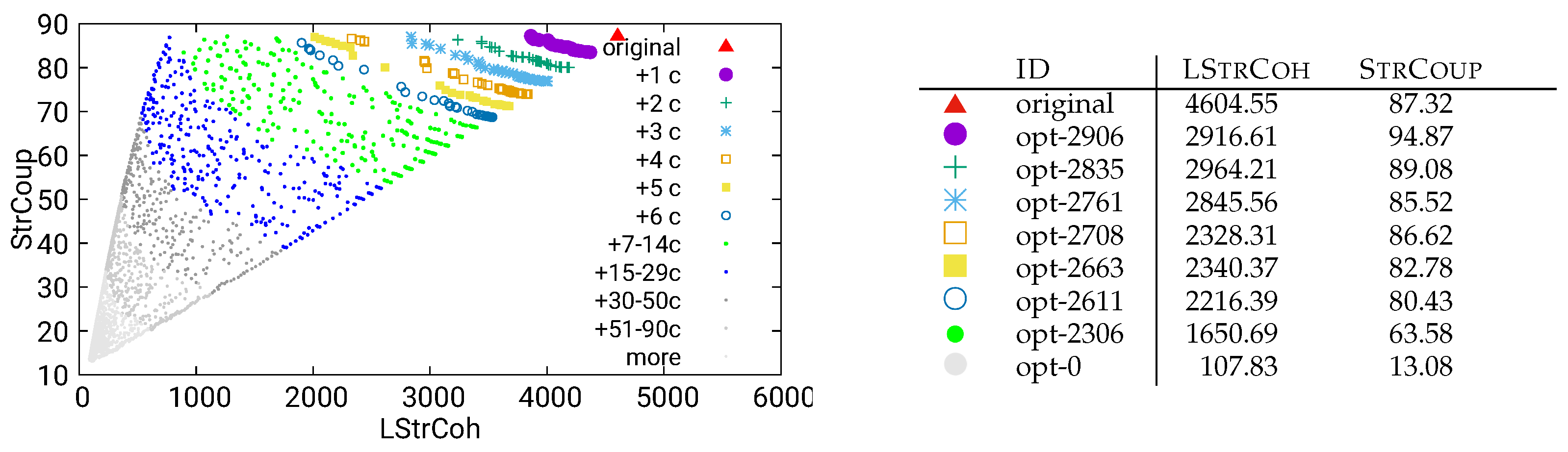

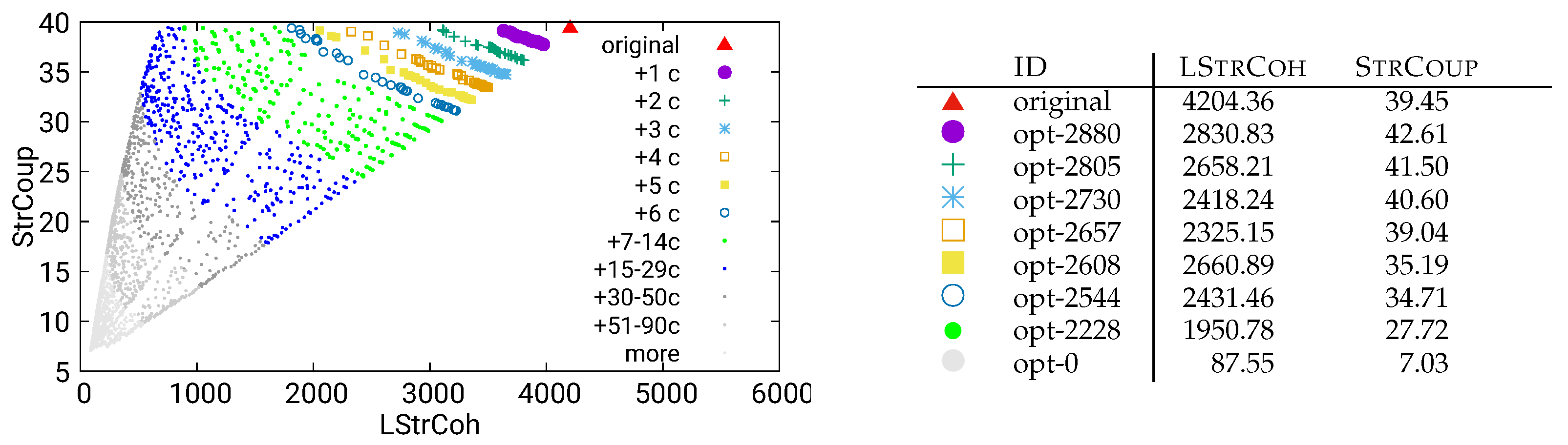

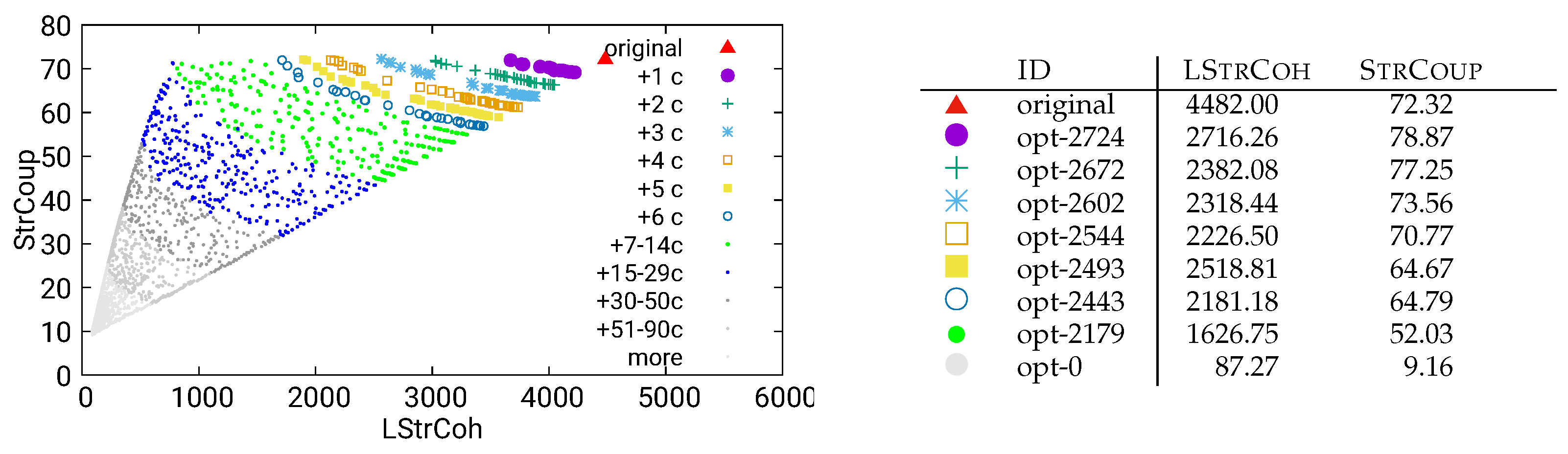

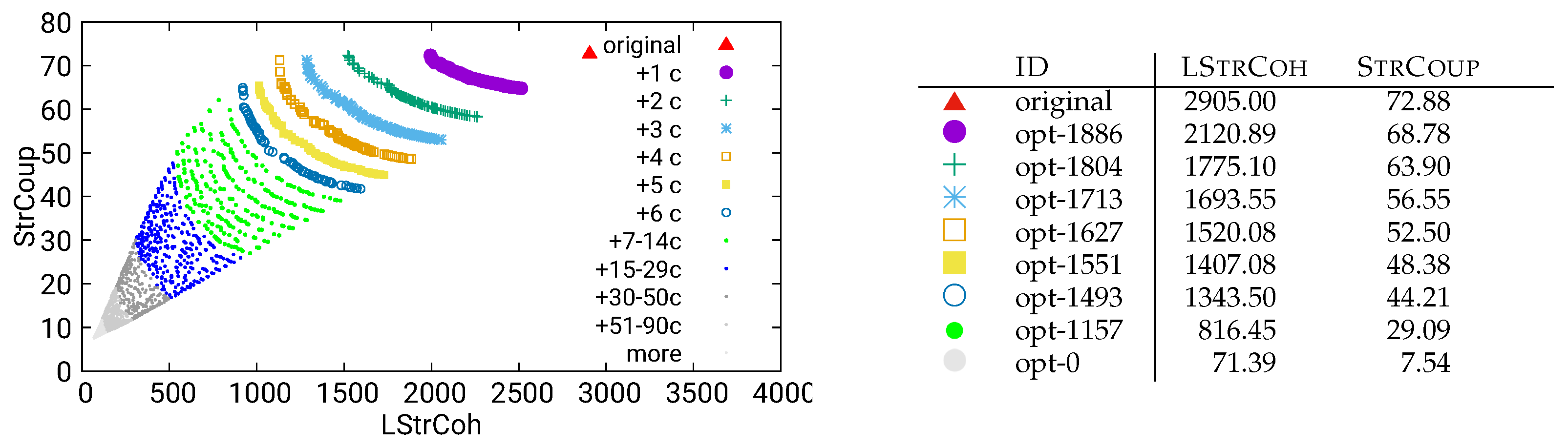

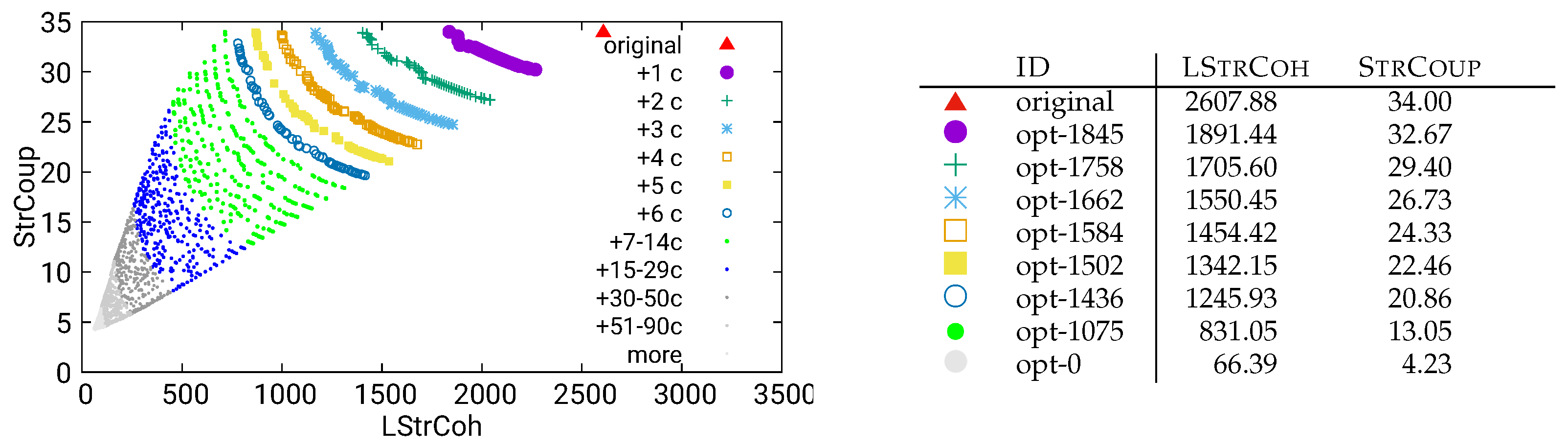

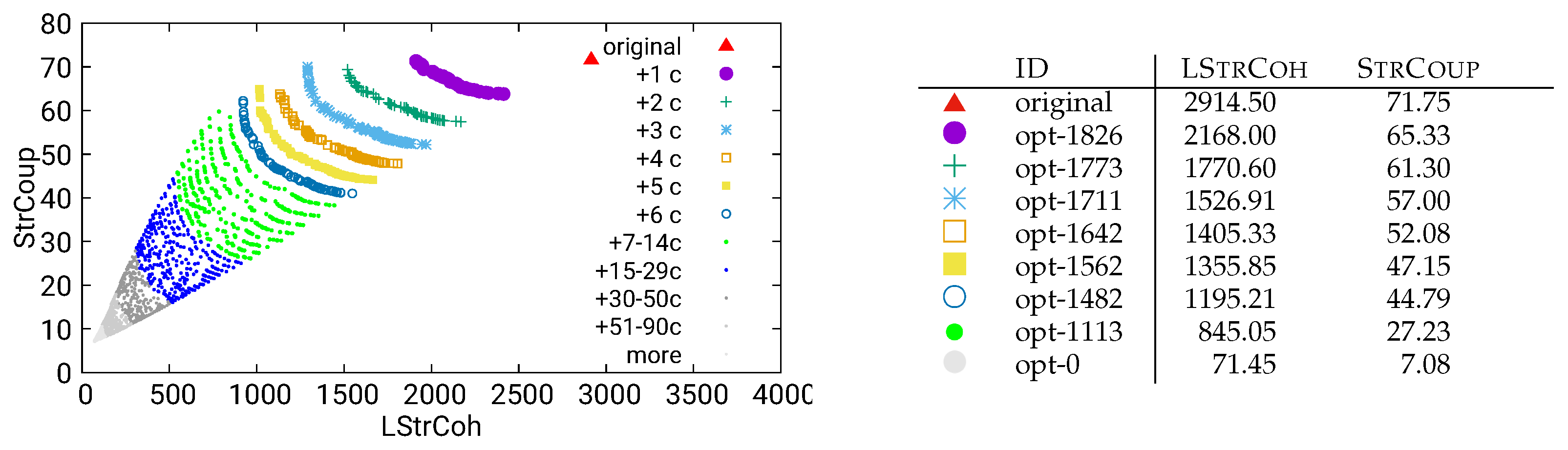

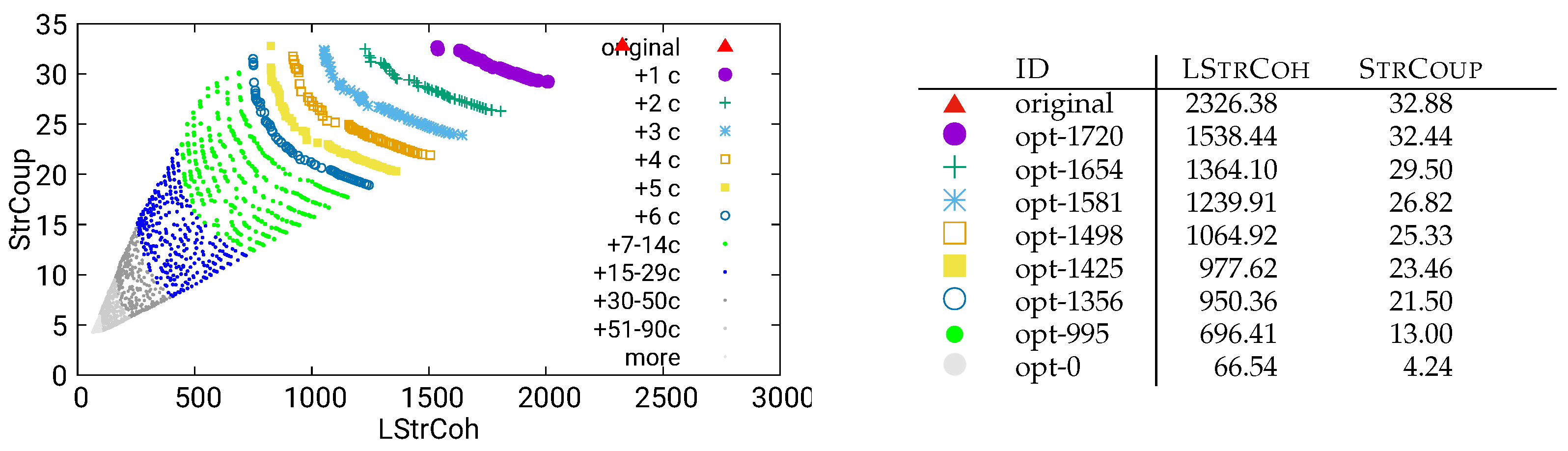

denote optimization results that introduce at most a single additional component compared to the original modularization of the software, while blue star-shaped symbols

denote optimization results that introduce at most a single additional component compared to the original modularization of the software, while blue star-shaped symbols  represent results that introduce three additional components, and the small blue dot

represent results that introduce three additional components, and the small blue dot  stands for optimizations introducing at least 15 and at most 29 additional components (the complete list of symbols is given in the legend of the plots). In this way, the plots illustrate not only the (expected) tradeoff between the quality metrics LStrCoh and StrCoup, but also between the conflicting goals of improving these metrics and introducing a few new components.

stands for optimizations introducing at least 15 and at most 29 additional components (the complete list of symbols is given in the legend of the plots). In this way, the plots illustrate not only the (expected) tradeoff between the quality metrics LStrCoh and StrCoup, but also between the conflicting goals of improving these metrics and introducing a few new components.5.2. Guided, Interactive Optimization

6. Optimization of UVic

6.1. Unguided Optimization

6.2. Guided, Interactive Optimization

7. Discussion

- The pure dynamic analysis produces significantly better modularizations than the optimizations based on the other analysis methods that we used for reverse engineering. This may a specific observation for our application domain of research software: If we use the scientific model for a specific experiment, we can optimize the software architecture for this specific use case. Only those parts of the software that are actually used in the experiment are represented in the reconstructed architecture, which is then optimized.

- The guided, interactive optimization provides good modularizations. Thus, we can recommend to feed expert feedback into the optimization process.

8. Related Work

9. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CMIP | Coupled Model Intercomparison Project |

| ESM | Earth System Model |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| LStrCoh | Lack of Structural Cohesion |

| MITgcm | MIT General Circulation Model |

| NSGA | Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm |

| PalMod | Paleoclimatic Modeling |

| SOLAS | Surface Ocean-Lower Atmosphere Study |

| StrCoup | Structural Coupling |

| UVic | University of Victoria Earth System Climate Model |

References

- Candela, I.; Bavota, G.; Russo, B.; Oliveto, R. Using Cohesion and Coupling for Software Remodularization: Is It Enough? ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2016, 25, 24:1–24:28. [CrossRef]

- Felderer, M.; Goedicke, M.; Grunske, L.; Hasselbring, W.; Lamprecht, A.L.; Rumpe, B. Investigating Research Software Engineering: Toward RSE Research. Commun. ACM 2025, 68, 20–23. [CrossRef]

- Hasselbring, W.; Jung, R.; Schnoor, H. Software Architecture Evaluation of Earth System Models. J. Softw. Eng. Appl. 2025, 18, 113–138. [CrossRef]

- Weaver, A.J.; et al. The UVic earth system climate model: Model description, climatology, and applications to past, present and future climates. Atmos. Ocean 2001, 39, 361–428. [CrossRef]

- Artale, V.; et al. An atmosphere-ocean regional climate model for the Mediterranean area: assessment of a present climate simulation. Clim. Dyn. 2010, 35, 721–740. [CrossRef]

- Hasselbring, W.; Druskat, S.; Bernoth, J.; Betker, P.; Felderer, M.; Ferenz, S.; Hermann, B.; Lamprecht, A.L.; Linxweiler, J.; Prat, A.; et al. Multi-Dimensional Research Software Categorization. Computing in Science & Engineering 2025, pp. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Johanson, A.; Hasselbring, W. Software Engineering for Computational Science: Past, Present, Future. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2018, 20, 90–109. [CrossRef]

- Jung, R.; Gundlach, S.; Hasselbring, W. Software Development Processes in Ocean System Modeling. Int. J. Model. Simulation, Sci. Comput. 2022, 13, 2230002. [CrossRef]

- Bréviére, E.H.; et al. Surface ocean-lower atmosphere study: Scientific synthesis and contribution to Earth system science. Anthropocene 2015, 12, 54–68. [CrossRef]

- Pahlow, M.; Chien, C.T.; Arteaga, L.A.; Oschlies, A. Optimality-based non-Redfield plankton–ecosystem model (OPEM v1. 1) in UVic-ESCM 2.9–Part 1: Implementation and model behaviour. Geosci. Model Dev. 2020, 13, 4663–4690. [CrossRef]

- Chien, C.T.; Pahlow, M.; Schartau, M.; Oschlies, A. Optimality-based non-Redfield plankton–ecosystem model (OPEM v1. 1) in UVic-ESCM 2.9–Part 2: Sensitivity analysis and model calibration. Geosci. Model Dev. 2020, 13, 4691–4712. [CrossRef]

- Mengis, N.; et al. Evaluation of the University of Victoria Earth System Climate Model version 2.10 (UVic ESCM 2.10). Geosci. Model Dev. 2020, 13, 4183–4204. [CrossRef]

- Stocker, T.F.; et al. Climate Change 2013 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Hasselbring, W. Software Architecture: Past, Present, Future. In The Essence of Software Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 169–184. [CrossRef]

- Reussner, R.; Goedicke, M.; Hasselbring, W.; Vogel-Heuser, B.; Keim, J.; Märtin, L. Managed Software Evolution; Springer: Cham, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Verdecchia, R.; Kruchten, P.; Lago, P., Architectural Technical Debt: A Grounded Theory. In Software Architecture; Springer, 2020; pp. 202––219. [CrossRef]

- Druskat, S.; Eisty, N.U.; Chisholm, R.; Chue Hong, N.; Cocking, R.C.; Cohen, M.B.; Felderer, M.; Grunske, L.; Harris, S.A.; Hasselbring, W.; et al. Better Architecture, Better Software, Better Research. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2025, pp. 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Schnoor, H.; Hasselbring, W. Comparing Static and Dynamic Weighted Software Coupling Metrics. Computers 2020, 9, 24. [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [CrossRef]

- Jung, R.; Schnoor, H.; Hasselbring, W. Replication Package for: Software Architecture Evaluation of Earth System Models (Restructuring Part), 2025. [CrossRef]

- Praditwong, K.; Harman, M.; Yao, X. Software Module Clustering as a Multi-Objective Search Problem. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2011, 37, 264–282. [CrossRef]

- Mkaouer, W.; Kessentini, M.; Shaout, A.; Koligheu, P.; Bechikh, S.; Deb, K.; Ouni, A. Many-objective software remodularization using NSGA-III. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. (TOSEM) 2015, 24, 1–45. [CrossRef]

- Sudhakar, G.; Nithiyanandam, S. DOOSRA—Distributed Object-Oriented Software Restructuring Approach using DIM-K-means and MAD-based ENRNN classifier. IET Softw. 2023, 17, 23–36. [CrossRef]

- Maikantis, T.; Tsintzira, A.A.; Ampatzoglou, A.; Arvanitou, E.M.; Chatzigeorgiou, A.; Stamelos, I.; Bibi, S.; Deligiannis, I. Software architecture reconstruction via a genetic algorithm: Applying the move class refactoring. In Proceedings of the 24th Pan-Hellenic Conference on Informatics, 2020, pp. 135–139. [CrossRef]

- Cortellessa, V.; Diaz-Pace, J.A.; Di Pompeo, D.; Frank, S.; Jamshidi, P.; Tucci, M.; van Hoorn, A. Introducing Interactions in Multi-Objective Optimization of Software Architectures. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2025, 34, 1–39. [CrossRef]

- Pourasghar, B.; Izadkhah, H.; Akhtari, M. Beyond Cohesion and Coupling: Integrating Control Flow in Software Modularization Process for Better Code Comprehensibility. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2025, 34, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Levenshtein, V.I. Binary codes capable of correcting deletions, insertions and reversals. Soviet Physics Doklady. 1966, 10, 707–710.

- Ankerst, M.; Breunig, M.M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Sander, J. OPTICS: ordering points to identify the clustering structure. SIGMOD Rec. 1999, 28, 49–60. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, G. A guided tour to approximate string matching. ACM Comput. Surv. 2001, 33, 31–88. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).