Introduction

Background

The rapid growth of social media platforms has significantly transformed how people communicate, share opinions, and engage with society. However, this increased connectivity has also led to a rise in the spread of hate speech-content that targets individuals or groups based on attributes such as religion, caste, gender, or ethnicity. While many tools and techniques have been developed to detect hate speech in English, there remains a notable gap when it comes to low-resource languages like Hindi, despite its widespread use across India and beyond.

Detecting hate speech in Hindi poses several unique challenges. The frequent use of code-mixed language (Hindi combined with English), informal spellings, and slang, along with the limited availability of annotated datasets, makes it difficult for traditional models to perform well. Moreover, hate speech in Hindi can often be subtle or implicit, requiring a deeper understanding of context and cultural nuances.

This research aims to address these issues by developing a machine learning-based approach for hate speech detection in Hindi. We focus on building effective preprocessing techniques tailored to Hindi text, handling code-mixed inputs, and experimenting with various classification models to improve accuracy. Our goal is to contribute to the growing field of multilingual content moderation and to support the creation of safer digital spaces for Hindi-speaking users.

Problem Statement

With the exponential growth of social media usage, online platforms have become common spaces for public discourse. However, this openness has also enabled the widespread circulation of hate speech-language intended to demean, threaten, or incite violence against individuals or communities. Detecting such content is crucial for maintaining respectful digital environments. While considerable research has focused on automated hate speech detection in English and other high-resource languages, there remains a significant gap in developing reliable systems for regional languages like Hindi, despite its massive user base in India and neighboring countries.

Hate speech detection in Hindi is particularly challenging due to several linguistic and technical factors. These include the lack of large-scale annotated datasets, frequent code-mixing with English, inconsistent spelling, informal syntax, and the use of culturally specific slang or sarcasm. Traditional machine learning models often struggle to generalize in such settings, especially when trained on limited or imbalanced data. Moreover, many prior studies rely on a single train-test split, which can lead to skewed performance estimates and overfitting to specific data distributions.

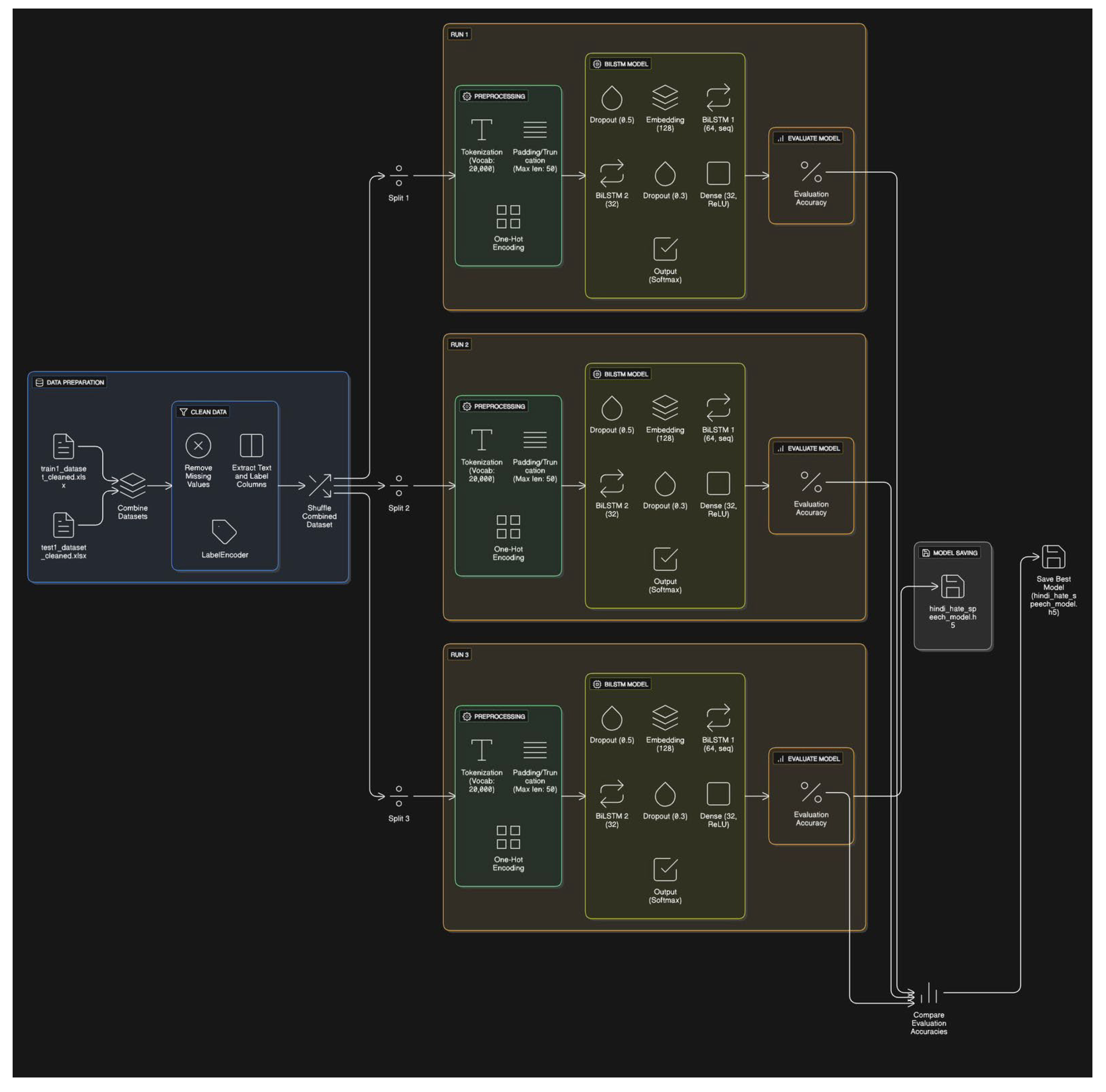

To address these challenges, this research proposes a deep learning-based approach using a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) network for multi-class hate speech classification in Hindi. Unlike conventional methods, this study employs a multi-split evaluation strategy, where the dataset is shuffled and re-partitioned into three different train-test combinations. This enables a more robust analysis of model generalization across varied subsets and contributes to building more reliable NLP systems for low-resource languages.

Objectives

The primary objective of this research is to develop a robust and language-specific model for the automatic detection of hate speech in Hindi text. Given the linguistic complexity and limited computational resources available for Hindi, this study aims to contribute toward building inclusive and effective content moderation tools. The specific objectives are as follows:

To preprocess and prepare a cleaned and labeled dataset of Hindi social media text suitable for training deep learning models, with attention to code-mixed (Hindi-English) inputs.

To design and implement a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) architecture capable of capturing both forward and backward contextual information in Hindi text for accurate multi-class classification.

To evaluate model robustness using a multi-split training and testing strategy by combining and shuffling the dataset to create three distinct train-test splits, ensuring the generalizability of the results.

To measure and analyze the model’s performance across different data distributions, using accuracy as the primary metric, and assess its consistency and limitations.

To highlight the challenges of hate speech detection in low-resource and code-mixed languages and propose this framework as a foundation for future multilingual or regional NLP research.

Literature Review

Urdu, a language that originated in India, is widely spoken in countries such as Pakistan and regions of Afghanistan. It shares a strong linguistic resemblance with Hindi, particularly in grammar and vocabulary, and is celebrated for its rich poetic tradition. In India, it is predominantly used in Uttar Pradesh, Telangana, and Jammu & Kashmir. Urdu is written using the Perso-Arabic script.

Efforts have been made to detect hate speech in Urdu. One such study by Bilal et al. [

4] focused on Roman Urdu. They created the RU-HSD-30K dataset containing 30,000 Roman Urdu messages and trained a BERT model from scratch called RU-BERT. In addition, they evaluated multilingual BERT and English BERT models on the same dataset. They applied two fine-tuning strategies: one where transformer model weights were frozen and used with BiLSTM and BiLSTM-attention classifiers, and another where the weights were updated during training with the same architectures. The transformer-based models outperformed traditional ML models significantly. Among classical models, Random Forest achieved the highest accuracy of 71%, while the transformer models reached an impressive 97%.

Das et al. [

7] leveraged datasets like HASOC 2021 and CONSTRAINT 2021 for detecting hate speech in Hindi. They addressed content in code-mixed Hindi, Devanagari Hindi, and English written in Devanagari. Using the multilingual BERT model (m-BERT), they defined 34 distinct categories—28 for monolingual and 6 for code-mixed hate speech—to differentiate between truly hateful statements and benign ones like “I hate apples,” which express dislike without targeting a group. They also dealt with implicit hate speech lacking offensive terms or explicit targets.

Saha et al. [

8] proposed a method for classifying Urdu text into abusive and threatening categories using the Urdu HASOC 2021 dataset. Their approach involved BERT embeddings coupled with classifiers like XGBoost and LGBM, as well as using multilingual BERT and DeHateBERT-Mono-Arabic models. Due to class imbalance in the dataset, they applied weighted training. The best F1 score for abusive tweet classification was 0.88, and 0.54 for threatening content, both achieved using the DeHateBERT-Mono-Arabic model.

Kanade et al. [

13] worked on Hindi hate speech classification using the HASOC 2021 dataset. They experimented with various text embeddings such as TF-IDF, Word2Vec, and Bag-of-Words, and used traditional ML algorithms including Naive Bayes, Logistic Regression, SVM, and Random Forest. The most effective setup combined Word2Vec with an SVM classifier, yielding a macro F1 score of 69% and an overall accuracy of 75%.

Kakwani et al. [

16] introduced the IndicNLPSuite, a comprehensive resource with monolingual corpora, evaluation benchmarks, and multilingual pretrained models for various Indian languages. This model was utilized in multiple downstream tasks, including hate speech detection.

Malik et al. [

17] identified a lack of consistent guidelines for labeling content as hateful in Roman Urdu. They developed the HS-RU-20 dataset and categorized text into hateful, offensive, and neutral. According to their criteria, hateful content attacks immutable characteristics like gender or ethnicity, whereas offensive speech is derogatory without targeting inherent traits. They tested traditional ML models using count vectorizer, n-gram, and character-level features. Logistic Regression combined with count vectorizer achieved the highest accuracy of 84%.

Velankar et al. [

29] addressed hate speech in Marathi using the HASOC 2021 dataset. They employed fastText embeddings in combination with deep learning methods such as 1D-CNN, LSTM, and BiLSTM. Transformer-based embeddings, including multilingual BERT, Roberta-mr, and IndicBERT [

16], were also evaluated. A hierarchical training framework was adopted: first identifying if a tweet was hateful, then classifying it further into profane, offensive, or hateful. The best results among transformer models came from IndicBERT, which achieved an 88% accuracy. The highest accuracy with fastText was 83% using 1D-CNN and non-trainable embeddings.

Later, Joshi et al. [

30] compiled a large-scale Marathi hate speech dataset named L3Cube-MahaHate, consisting of over 25,000 tweets labeled as hateful, offensive, profane, or non-hateful. They fine-tuned a multilingual BERT model on this dataset and released it as MahaBERT on HuggingFace [

22].

Shukla et al. [

27] experimented with BERT embeddings and their combination with CNNs on HASOC datasets from 2020 and 2021. To mitigate class imbalance, they employed oversampling. On the oversampled HASOC 2020 dataset, they achieved an F1 score of 85%, while for HASOC 2021, they achieved 77% using a hybrid model of BERT and 1D-CNN.

Model and Methodology

This section outlines the complete pipeline used for building the hate speech detection model in Hindi. It includes dataset preparation, preprocessing techniques, model architecture design, training configurations, and evaluation strategies.

Data

The dataset used in this study consists of 15,000 labeled entries sourced from a combination of tweets (from Twitter) and hate speech excerpts from newspapers and televised news broadcasts. This diverse sourcing strategy ensures a realistic representation of hate speech in Hindi, capturing both informal and formal styles of language.

4.1. Structure and Composition

The dataset includes the following columns:

Unique ID: A unique integer identifier for each post.

Post: The raw text content in Hindi, including both original and code-mixed (Hindi-English) forms.

Labels Set: A string or set of labels indicating the hostility of the content.

From the full dataset:

10,000 entries were used for training, and

5,000 for testing,

in the initial configuration. Each post was annotated manually with one or more labels from a predefined label set.

4.2. Label Encoding

For the purposes of classification:

The original textual labels were encoded into binary form (0 or 1) using LabelEncoder, representing hostile vs non-hostile content.

Although the original dataset supports multi-label classification (e.g., posts labeled both as hate and offensive), this study focused on single-label multi-class classification, treating each instance with a dominant label.

The labels included are:

non-hostile: No hate or offensive content

hate: Contains hate speech

offensive: Contains offensive language

defamation: Defames individuals or groups

4.3. Shuffling and Splitting Strategy

After initial loading:

The 10k training and 5k testing sets were merged into a unified corpus of 15,000 entries.

The combined dataset was then randomly shuffled and split into three different train-test combinations, each with 10,000 training samples and 5,000 test samples.

This multi-split strategy was used to test model robustness, evaluate performance stability, and detect overlap effects across data distributions.

Each of the three splits was used to independently train and evaluate a deep learning model, and the results were later compared to assess generalization across different sample compositions.

4.4. Key Features

Comprehensive and Diverse: Posts span formal (e.g., news clips) and informal (e.g., tweets) language, including varying tones, topics, and dialects.

Focused on Hindi: All posts are in Hindi or Hindi-English code-mixed formats, making it a valuable dataset for regional NLP tasks.

Multi-label Annotations: Posts may carry more than one label, reflecting real-world ambiguity in how hate speech manifests.

Language Richness: The dataset captures colloquialisms, slang, and regional variations, all of which introduce complexity for automated classification.

4.5. Challenges

Language Nuances: Slang, sarcasm, spelling inconsistencies, and informal grammar pose challenges for tokenization and semantic modeling.

Multi-label Classification Potential: While this study focuses on single-label classification, future work may explore the dataset’s full multi-label potential using more advanced architectures.

Data Preprocessing

The raw training and testing datasets were sourced from pre-cleaned Excel files containing labeled Hindi social media text. Initially, all missing entries were removed to ensure data consistency. The text and label fields were extracted, and categorical labels were converted into numerical form using scikit-learn’s LabelEncoder. These integer labels were then one-hot encoded to prepare them for multi-class classification.

Tokenization was carried out using Keras’ Tokenizer, limited to a vocabulary size of 20,000 words, with an Out-of-Vocabulary (OOV) token to handle rare or unseen terms. Each sentence was converted into a sequence of integers and padded to a uniform length of 50 tokens. This preprocessing was applied uniformly across all experimental runs.

To enhance generalizability and test model robustness, the preprocessed training and testing datasets were combined into a single corpus and subjected to three different random shuffles. For each shuffle, the combined data was split into new training and testing sets. The model was trained independently on each of these three configurations.

Model Architecture

A Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) neural network was employed due to its effectiveness in capturing long-range dependencies and contextual nuances, which are particularly relevant for Hindi and code-mixed content. The architecture consisted of the following layers:

An embedding layer that maps each word index to a dense vector of 128 dimensions.

A Bidirectional LSTM layer with 64 units and return_sequences=True, allowing sequential outputs to be passed to subsequent layers.

A dropout layer with a rate of 0.5 to mitigate overfitting.

A second Bidirectional LSTM layer with 32 units, followed by a dense layer of 32 units with ReLU activation.

A final softmax output layer to classify inputs into one of the predefined categories.

This architecture was kept consistent across all three training runs to ensure comparability

Figure 1.

BiLSTM architecture for classifying Hindi hate speech classification.

Figure 1.

BiLSTM architecture for classifying Hindi hate speech classification.

Model Training

The model was compiled using the categorical cross-entropy loss function and optimized with the Adam optimizer. Accuracy was used as the primary evaluation metric. Each shuffled dataset configuration was used to train the model for 10 epochs with a batch size of 32. Validation was performed on the respective test split from each shuffle.

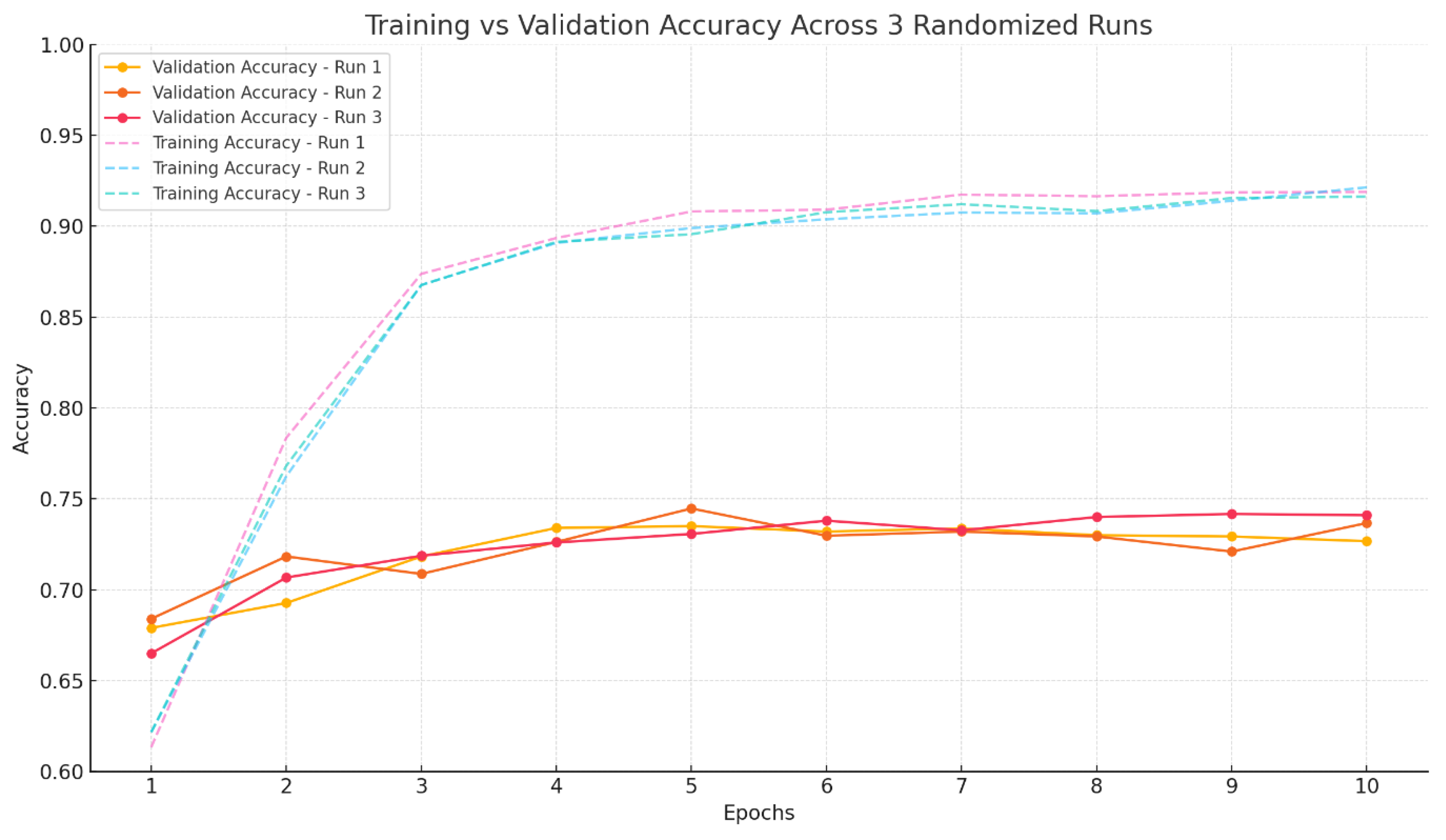

Training was repeated across the three randomized train-test splits as follows:

Run 1: Achieved a test accuracy of 72.67%

Run 2: Achieved a test accuracy of 73.67%

Run 3: Achieved a test accuracy of 74.10%

Figure 2.

Training and validation accuracy across 10 epochs for three randomized train-test splits using the BiLSTM model.

Figure 2.

Training and validation accuracy across 10 epochs for three randomized train-test splits using the BiLSTM model.

These results demonstrate consistent performance across different splits and highlight the model’s ability to generalize across varied samples of the data.

Results and Discussion

The proposed BiLSTM-based model was trained and evaluated on three distinct randomized splits of the combined dataset. The model consistently demonstrated reliable performance across all runs, with test accuracy values as follows:

Run 1: 72.67%

Run 2: 73.67%

Run 3: 74.10%

These results indicate a relatively narrow performance margin across different data distributions, suggesting that the model is not heavily reliant on specific data ordering and generalizes well within the available corpus. The highest accuracy of 74.10% was observed in the third run, which was retained as the final model for downstream use. The consistent progression of test accuracy across the three runs also implies that minor variations in the distribution of training and test data can slightly impact the learning dynamics of the model, especially in low-resource and code-mixed contexts.

Conclusion

This study presents a deep learning approach for hate speech detection in Hindi using a Bidirectional LSTM architecture. Through careful preprocessing, tokenization, and repeated training across randomized data splits, the model achieved stable test accuracy in the range of 72-74%. While these results are promising, they also reflect certain inherent limitations of working with regional and under-resourced languages.

The relatively moderate accuracy can be attributed to several factors: the linguistic complexity of Hindi, frequent code-mixing with English, and the lack of large-scale, high-quality annotated datasets. Moreover, subtle or implicit hate speech-often embedded in sarcasm, idiomatic phrases, or culturally nuanced references-remains difficult for sequential models to detect without deeper semantic understanding.

Despite these challenges, the model lays a strong foundation for future work. Improvements could include the integration of pretrained multilingual transformers (e.g., mBERT, IndicBERT), the use of attention mechanisms for better context capturing, and the expansion of the dataset through crowd-sourced annotations or transfer learning. More importantly, this work highlights the urgent need for developing NLP tools that are linguistically and culturally inclusive, especially for languages like Hindi that represent a large segment of the digital population but remain underserved in computational research.

Future Scope

While this study demonstrates the feasibility of using BiLSTM-based deep learning models for hate speech detection in Hindi, there remains substantial room for advancement, particularly given the complexity of language and the sociolinguistic context in which hate speech appears. Several promising directions for future work include:

Integration of Transformer-based Models: Leveraging state-of-the-art pretrained language models such as mBERT, IndicBERT, or XLM-RoBERTa may significantly improve performance. These models are capable of capturing deeper contextual relationships and are particularly suited for handling code-mixed and multilingual text.

Dataset Expansion and Annotation: The current model is limited by the scale and scope of the available dataset. Future work should focus on expanding the dataset through crowd-sourced annotations, semi-supervised learning, or data augmentation strategies. Additionally, labeling hate speech across varied categories such as communal, caste-based, or gendered hate can support more fine-grained classification.

Code-Mixed and Dialect-Aware Modeling: As code-mixing (e.g., Hindi-English) is prevalent on Indian social media, future systems could incorporate code-mix aware embeddings, language identification modules, or switch-point detection to better model linguistic variability.

Explainability and Fairness: Integrating explainable AI (XAI) frameworks can make model predictions more interpretable, especially in sensitive domains like hate speech detection. Ensuring fairness across demographic groups is also crucial to avoid reinforcing societal biases.

Real-Time and Scalable Systems: Future implementations may also explore deploying the model as part of real-time moderation pipelines on social media platforms. This would involve optimizing the model for speed and memory efficiency, possibly via quantization or pruning techniques.

Multi-label and Implicit Hate Detection: As hateful content is often subtle or sarcastic, future models should move toward implicit hate detection and multi-label classification, where a single text may contain overlapping types of harmful speech.

References

- Alammar, J. The illustrated transformer. 2021. Available online: https://jalammar.github.io/illustrated-transformer/.

- Bojanowski, P.; Grave, E.; Joulin, A.; Mikolov, T. Enriching word vectors with subword information. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2017, 5, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, J.L.; Kiros, J.R.; Hinton, G.E. Layer normalization. arXiv arXiv:1607.06450, 2016. [PubMed]

- Bilal, M.; Khan, A.; Jan, S.; Musa, S.; Ali, S. Roman urdu hate speech detection using transformer-based model for cyber security applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanh, V.; Debut, L.; Chaumond, J.; Wolf, T. Distilbert, a distilled version of bert: Smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv 2019. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A. A visual guide to fasttext word embeddings. Available online: https://amitness.com/2020/06/fasttext-embeddings/ (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Das, M.; Saha, P.; Mathew, B.; Mukherjee, A. Hatecheckhin: Evaluating hindi hate speech detection models. arXiv arXiv:2205.00328, 2022.

- Das, M.; Banerjee, S.; Saha, P. Abusive and threatening language detection in urdu using boosting based and bert based models: A comparative approach. arXiv 2021. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv 2018. [CrossRef]

- Devjyoti Chakrobarty, A.R.G. ‘An introduction to the global vectors (glove) algorithm. 2021. Available online: https://wandb.ai/authors/embeddings-2/reports/GloVe--VmlldzozNDg2NTQ.

- ‘‘Distillation of bert-like models: The theory. Available online: https://towardsdatascience.com/distillation-of-bert-like-models-the-theory-32e19a02641f (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Venugopal, K. Mathematical introduction to glove word embedding. 2021. Available online: https://becominghuman.ai/mathematical-introduction-to-glove-wordembedding-60f24154e54c.

- Jadhav, I.; Kanade, A.; Waghmare, V.; Chaudhari, D. Hate and offensive speech detection in hindi twitter corpus. in Forum for Information Retrieval Evaluation (Working Notes)(FIRE), CEUR-WS. org, 2021.

- Jha, A. Vectorization techniques in nlp [guide]. 2023. Available online: https://neptune.ai/blog/vectorization-techniques-in-nlp-guide.

- Jitender. Implement sigmoid function using numpy. 2023. Available online: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/implement-sigmoid-function-using-numpy/#article-meta-div.

- Kakwani, D.; Kunchukuttan, A.; Golla, S.; Gokul, N.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Khapra, M.M.; Kumar, P. Indicnlpsuite: Monolingual corpora, evaluation benchmarks and pre-trained multilingual language models for indian languages. in Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, 2020, pp. 4948--4961.

- Khan, M.M.; Shahzad, K.; Malik, M.K. Hate speech detection in roman urdu. ACM Transactions on Asian and Low-Resource Language Information Processing (TALLIP) 2021, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanuja, S.; Bansal, D.; Mehtani, S.; Khosla, S.; Dey, A.; Gopalan, B.; Margam, D.K.; Aggarwal, P.; Nagipogu, R.T.; Dave, S.; et al. Muril: Multilingual representations for indian languages. arXiv 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mandl, T.; Modha, S.; Shahi, G.K.; Madhu, H.; Satapara, S.; Majumder, P.; Schäfer, J.; Ranasinghe, T.; Zampieri, M.; Nandini, D.; et al. Overview of the hasoc subtrack at fire 2021: Hate speech and offensive content identification in english and indo-aryan languages. arXiv 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, K.; Essam, D.; Shafi, K.; Malik, M.K. An unsupervised lexical normalization for roman hindi and urdu sentiment analysis. Information Processing & Management 2020, 57, 102368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolov, T.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.; Dean, J. Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv 2013. [CrossRef]

- Mahabert. Available online: https://huggingface.co/l3cube-pune/marathi-bert (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Mishra, R. devanagari-to-roman-script-transliteration. 2019. Available online: https://github.com/ritwikmishra/devanagari-to-roman-script-transliteration.

- Weng, L. Learning word embedding. 2017. Available online: https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2017-10-15-word-embedding/.

- Pennington, J.; Socher, R.; Manning, C.D. Glove: Global vectors for word representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (EMNLP); 2014; pp. 1532–1543. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Kabra, A.; Jain, M. Ceasing hate with moh: Hate speech detection in hindi--english code-switched language. Information Processing & Management 2022, 59, 102760. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, S.; Nagpal, S.; Sabharwal, S. Hate speech detection in hindi language using bert and convolution neural network. in 2022 International Conference on Computing, Communication, and Intelligent Systems (ICCCIS). IEEE, 2022, pp. 642--647.

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. The Journal of Machine Learning Research 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Velankar, A.; Patil, H.; Gore, A.; Salunke, S.; Joshi, R. Hate and offensive speech detection in hindi and marathi. arXiv 2021. [CrossRef]

- Velankar, A.; Patil, H.; Gore, A.; Salunke, S.; Joshi, R. L3cube-mahahate: A tweet-based marathi hate speech detection dataset and bert models. arXiv arXiv:2203.13778, 2022.

- Phi, M. Illustrated guide to transformers- step by step explanation. Available online: https://towardsdatascience.com/illustrated-guide-to-transformers-stepby-step-explanation-f74876522bc0 (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Navlani, A. Decision tree classification in python tutorial. 2023. Available online: https://www.datacamp.com/tutorial/decision-tree-classification-python.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).