Submitted:

05 August 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

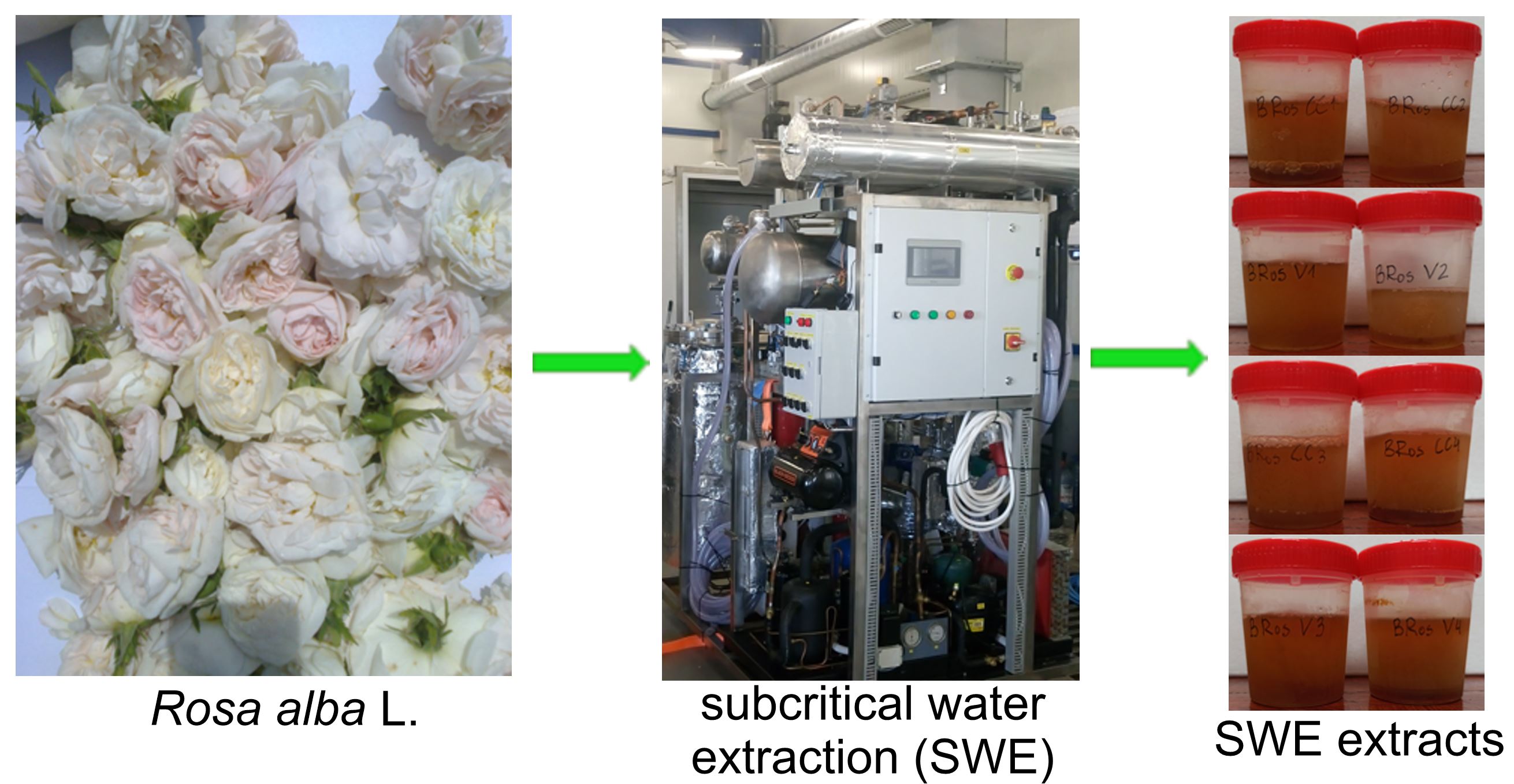

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Experimental Design

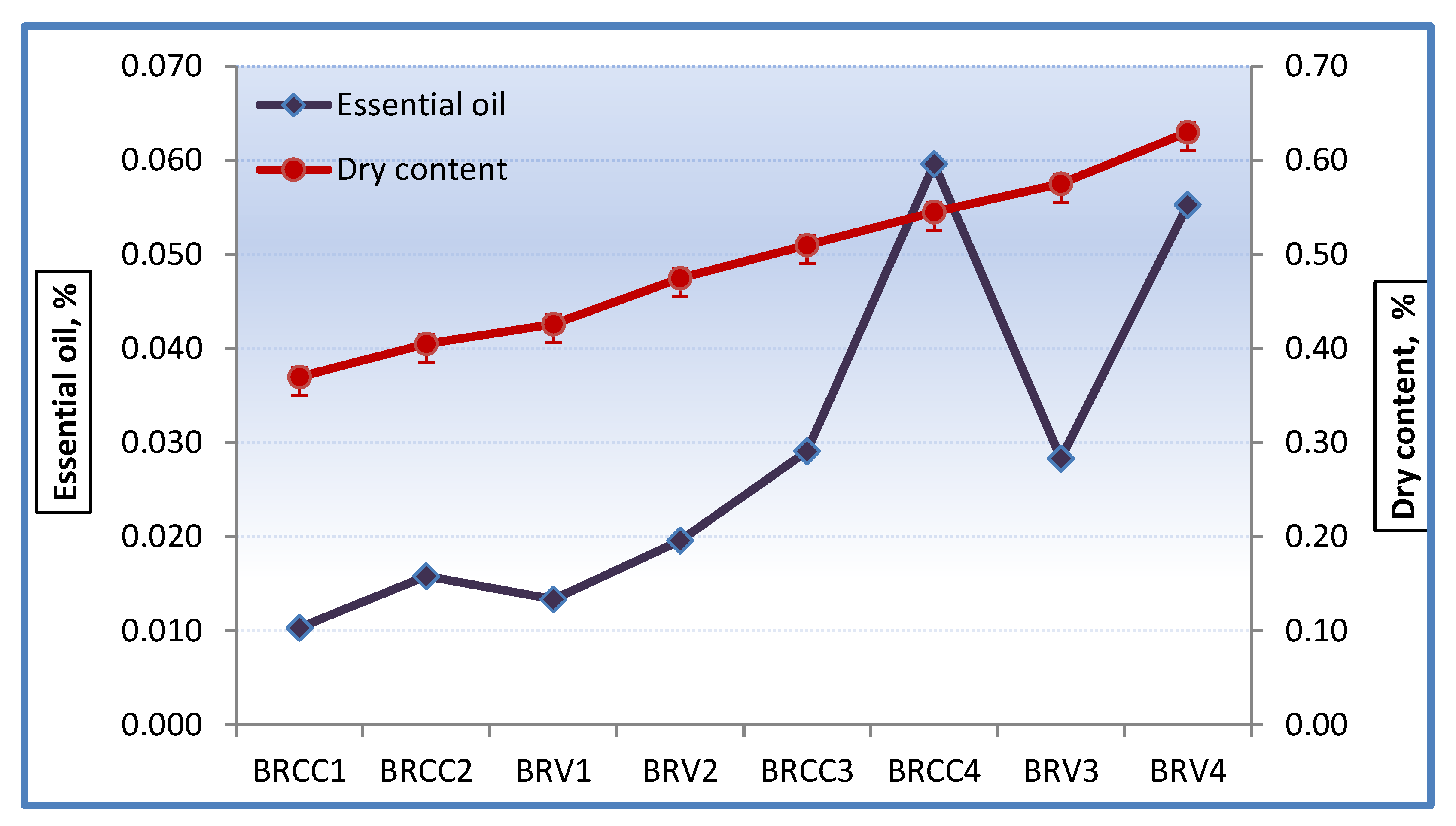

3.2. Extracts

3.3. Chemical Composition of the Extracts

3.3.1. Gas-Chromatography – Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Analyses

3.3.2. Total Neutral Sugars and Protein Content Determination

3.3.3. Monosaccharide Composition of SWE Extracts

3.3.4. Total Polyphenols, Total Flavonoids and Antioxidant Activity of R. alba SWE Extracts

| Compound | Concentration, µg/mL | |||||||

| BRCC1 | BRCC2 | BRV1 | BRV2 | BRCC3 | BRCC4 | BRV3 | BRV4 | |

| Gallic acid | 44.45±1.01e | 39.07±0.86f | 30.92±0.98g | 40.79±1.05f | 68.17±1.05d | 113.37±1.35a | 104.34±1.35c | 108.85±0.99b |

| Protocatehuic acid | NF* | NF | NF* | NF | NF | 13.05±0.94c | 19.22±0.67b | 25.48±0.86a |

| (+)-Catechin | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF |

| Chlorogenic acid | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF |

| Vanillic acid | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF |

| Caffeic acid | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF |

| Syringic acid | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF |

| (-)-Epicatechin | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF |

| p-Coumaric acid | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF |

| Ferulic acid | 99.96±1.80a | 47.21±1.62e,f | 77.49±1.02c | 87.56±1.68b | 51.36±1.85e | 44.50±1.47f | 84.26±1.57b | 67.63±1.77d |

| Salicylic acid | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF |

| Rutin | 47.13±1.21a | 19.25±0.99e | 33.04±0.89c | 37.76±1.02b | 16.58±1.35f | 13.53±0.86g | 31.01±1.14c | 25.00±0.94d |

| Hesperidin | 10.95±0.94a | 2.51±0.87d | 7.42±0.96b | 6.12±0.85b,c | 7.68±0.88b | 5.77±1.02c | 10.95±0.94a | 2.51±0.87d |

| Rosmarinic acid | 65.12±1.74b | 25.27±1.16f | 50.06±1.02c | 46.95±1.11d | 79.41±1.34a | 80.47±1.20a | 65.12±1.74b | 25.27±1.16f |

| Quercetin | NF | NF | NF | NF | 8.35±0.89b | 8.25±0.94b | NF | NF |

| Kaempherol | NF | NF | NF | NF | ULOQ** | 0.311±0.08 | NF | NF |

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SWE | Subcritical water extraction |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography – Mass spectrometry |

| HPLC | High performance liquid chromatography |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical |

| ABTS | 2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid |

| FRAP | Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power |

| CUPRAC | CUPric Reducing Antioxidant Capacity |

References

- Mileva, M.; Ilieva, Y.; Jovtchev, G.; Gateva, S.; Zaharieva, M.M.; Georgieva, A.; Dimitrova, L.; Dobreva, A.; Angelova, T.; Vilhelmova-Ilieva, N.; Valcheva, V.; Najdenski, Н. Rose flowers – A delicate perfume or a natural healer? Biomolecules, 2021, 11, 127, 1–32. [CrossRef]

- Vardakas, A. A new process for enzyme-assisted subcritical water extraction of rice husk polyphenols. Sci. Works Univ. Food Technol. 2020, 67(1), 76–81.

- Chemat, F.; Abert Vian, M.; Ravi, H.K.; Khadhraoui, B.; Hilali, S.; Perino, S.; Fabiano Tixier, A.-S. Review of alternative solvents for green extraction of food and natural products: Panorama, principles, applications and prospects. Molecules 2019, 24, 3007, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Nastić, N.; Švarc-Gajić, J.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Barroso, F.; Soares, C.; Moreira, M.; Morais, S.; Mašković, P.; Srček, V.; Slivac, I.; Radošević, K.; Radojković, M. Subcritical water extraction as an environmentally-friendly technique to recover bioactive compounds from traditional Serbian medicinal plants. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 111, 579–589. [CrossRef]

- Atanasova, A.; Petrova, A.; Teneva, D.; Ognyanov, M.; Georgiev, Y.; Nenov, N.; Denev, P. Subcritical water extraction of rosmarinic acid from lemon balm (Melissa officinalis L.) and its effect on plant cell wall constituents. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 888, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, E.; Kubatova, A.; Senorans, F.J.; Cavero, S.; Reglero, G.; Hawthorne, S.B. (2003). Subcritical water extraction of antioxidant compounds from rosemary plants. J Agricul. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 375–382.

- Zhang, J.; Wen, C.; Zhang, H.; Duan, Y.; Ma, H. Recent advances in the extraction of bioactive compounds with subcritical water, A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 95, 183–195. [CrossRef]

- Özel, M., Clifford, A. Superheated water extraction of fragrance compounds from Rosa canina. Flavour Fragr. J. 2004, 19(4), 354–359. [CrossRef]

- Özel, M.; Göǧüş, F.; Lewis, A. Comparison of direct thermal desorption with water distillation and superheated water extraction for the analysis of volatile components of Rosa damascena Mill. using GCxGC-TOF/MS. Anal. Chim. Acta, 2006, 566, 172–177. [CrossRef]

- DuBois, M.; Gilles, K.; Hamilton, J.; Rebers, P.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28(3), 350–356.

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein using the principle of protein dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, I.; Vrancheva, R.; Marchev, A.; Petkova, N.; Aneva, I.; Denev, P.; Georgiev, V.; Pavlov, A. Antioxidant activities and phenolic compounds in Bulgarian Fumaria species. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 296–306.

- Krasteva, G.; Berkov, S.; Pavlov, A.; Georgiev, V. Metabolite profiling of Gardenia Jasminoides Ellis in vitro cultures with different levels of differentiation. Molecules 2022, 27, 8906. [CrossRef]

- Industry standard BS – II – 02. Natural rose water. 2006. Bulgarian Association of Essential Oils, Perfumes and Cosmetics (BNAEOPC). https://www.bnaeopc.com/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Mihailova, J.; Atanasova, R.; Balinova-Tsvetkova, A. Direct gas chromatography of essential oil in the separate parts of the flower of the Kazanlik rose (Rosa damascena Mill. trigintipetala Dieck). In Proceedings of VIIth International Congress of the Essential Oils, Kyoto, Japan, 1977a, October 1977, 219–221.

- Agarwal, S.G.; Gupta, A.; Kapahi, B.K.; Baleshwar, Thappa, R.K.; Suri, O.P. Chemical composition of rose water volatiles. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2005, 17(3), 265–267. [CrossRef]

- Babu, K.G.D.; Singh, B.; Joshi, V.P.; Singh, V. Essential oil composition of Damask rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) distilled under different pressures and temperatures. Flavour Fragr. J. 2002, 17, 136–140. [CrossRef]

- Antonova, D.V.; Medarska, Y.N.; Stoyanova, A.S.; Nenov N.S.; Slavov, A.M.; Antonov, L.M. Chemical profile and sensory evaluation of Bulgarian rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) aroma products, isolated by different techniques. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2021, 33(2), 171–181. [CrossRef]

- ISO 9842:2024. Oil of Rose (Rosa x damascena Miller). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/86897.html (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Mihailova, J.; Decheva, R.; Koseva, D. Microscopic and biochemical study of starch and localization of essential oil in the corolla leaves of the Kazanlak oil-bearing rose. Plant Sci. 1977b, XIV(2), 34–40 (In Bulgarian).

- Sood, S.; Vyas, D.; Nagar, P.K. Physiological and biochemical studies during flower development in two rose species. Scientia Hort. 2006, 108(4), 390–396. [CrossRef]

- Wyman, C.E.; Dale B.E. Producing biofuels via the sugar platform. Chem. Eng. Prog. 2015, 111(3), 45–51.

- Wojcieszak, R.; Itabaiana I. Engineering the future: Perspectives in the 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid synthesis. Catal. Today 2020, 354(1), 211–2017. [CrossRef]

- Slavov, A.; Chalova, V. Physicochemical characterization of pectic polysaccharides from rose essential oil industry by-products. Foods 2024, 13(2), 270, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Slavov, A.; Vasileva, I.; Denev, P.; Dinkova, R.; Teneva, D.; Ognyanov, M.; Georgiev Y. Polyphenol-rich extracts from essential oil industry wastes. Bul. Chem. Commun. 2020, 52(Special Issue D), 78–83.

- Dobreva, A.; Gerdzhikova, M. 2013. The flavonoid content in the white oil-bearing rose (Rosa alba L.). Agricul. Sci. Technol. 2013, 5(1), 134–136.

- Georgieva, A.; Dobreva, A.; Tzvetanova, E.; Alexandrova, A.; Mileva, M. Comparative study of phytochemical profiles and antioxidant properties of hydrosols from Bulgarian Rosa alba L. and Rosa Damascena Mill. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants. 2019, 22, 1362–1371.

- Ilieva, Y.; Dimitrova, L.; Georgieva, A.; Vilhelmova-Ilieva, N.; Zaharieva, M.M.; Kokanova-Nedialkova, Z.; Dobreva, A.; Nedialkov, P.; Kussovski, V.; Kroumov, A.D.; Najdenski, H., Mileva, M. In vitro study of the biological potential of wastewater obtained after the distillation of four Bulgarian oil-bearing roses. Plants 2022, 11, 1073, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Baydar, N.; Baydar, H. Phenolic compounds, antiradical activity and antioxidant capacity of oil-bearing rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) extracts. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 41, 375–380. [CrossRef]

- Chroho, M.; Bouymajane, A.; Oulad El Majdoub, Y.; Cacciola, F.; Mondello, L.; Aazza, M.; Zair, T.; Bouissane, L. Phenolic composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of extract from flowers of Rosa damascena from Morocco. Separations 2022, 9, 247, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Gavra, D.I.; Endres, L.; Pet˝o, Á.; Józsa, L.; Fehér, P.; Ujhelyi, Z.; Pallag, A.; Marian, E.; Vicas, L.G.; Ghitea, T.C.; Muresan M., Bácskay I., Jurca T. In vitro and human pilot studies of different topical formulations containing Rosa species for the treatment of psoriasis. Molecules, 2022, 27, 5499, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Sivaraj, C.; Abhirami, R.; Deepika, M.; Sowmiya, V.; Saraswathi, K.; Arumugam, P. Antioxidant, antibacterial activities and GC-MS analysis of fresh rose petals aqueous extract of Rosa damascena Mill L. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2019, 9(4-s), 68–77. [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, Z.; Fattahi, M. Essential oil, total phenolic, flavonoids, anthocyanins, carotenoids and antioxidant activity of cultivated Damask Rose (Rosa damascena) from Iran: With chemotyping approach concerning morphology and composition. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 288, 110341. [CrossRef]

- Ko, M.J.; Cheigh, C.I.; Chung, M.S. Relationship analysis between flavonoids structure and subcritical water extraction (SWE). Food Chem. 2014, 143, 147–155. [CrossRef]

| № | Sample description | Abbreviation | Parameters | Extracts obtained, mL | |

| Temperature, °C | Duration, min | ||||

| 1 | Whole flowers | BRCC1 | 100 | 15 | 1937 ± 23 |

| 2 | Whole flowers | BRCC2 | 100 | 30 | 2017 ± 15 |

| 3 | Petals | BRV1 | 100 | 15 | 1978 ± 10 |

| 4 | Petals | BRV2 | 100 | 30 | 2050 ± 15 |

| 5 | Whole flowers | BRCC3 | 150 | 15 | 2112 ± 20 |

| 6 | Whole flowers | BRCC4 | 150 | 30 | 2066 ± 12 |

| 7 | Petals | BRV3 | 150 | 15 | 2053 ± 18 |

| 8 | Petals | BRV4 | 150 | 30 | 2056 ± 21 |

| № | RI | List of the components / classes | Essential oil | BRCC1 | BRCC2 | BRV1 | BRV2. | BRCC3 | BRCC4 | BRV3b | BRV4a |

| Relative % | |||||||||||

| 1 | 668 | Ethanol | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | 1031 | Limonene | 0.06 | 3.31 | 2.16 | 2.94 | 2.67 | 0.08 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 1.00 |

| 3 | 1098 | Linalool | 1.29 | 13.40 | 18.42 | 13.11 | 7.35 | 20.69 | 2.98 | 8.84 | 2.83 |

| 4 | 1118 | 2-Phenylethanol | 0.16 | 14.48 | 10.55 | 14.08 | 6.69 | 13.36 | 25.05 | ||

| 5 | 1109 | Cis-rose oxide | 0.04 | 0.91 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.15 | 0.35 | 1.26 |

| 6 | 1134 | Trans-rose oxide | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 1.84 | 0.12 | 0.68 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.92 |

| 7 | 1228 | Citronellol + Nerol | 14.92 | 0.97 | 0.20 | 0.86 | 4.87 | 3.28 | 0.87 | 0.38 | 0.88 |

| 8 | 1276 | Geraniol | 19.71 | 7.81 | 6.84 | 9.08 | 5.94 | 0.68 | 0.98 | 3.41 | 10.48 |

| 9 | 1364 | Eugenol | 0.06 | 2.47 | 1.72 | 1.36 | 3.58 | 8.33 | 1.35 | 1.83 | 3.62 |

| 10 | 1401 | Methyl eugenol | 0.05 | 5.80 | 4.12 | 3.49 | 7.80 | 0.22 | 2.99 | 3.77 | 1.93 |

| 11 | 1678 | Heptadecane | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.58 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.69 | 1.36 | 0.62 | 0.06 |

| 12 | 1727 | Farnesol | 3.77 | 0.08 | 0.19 | - | 0.10 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.05 |

| 13 | 1874 | Nonadecene | 5.50 | 0.46 | 2.70 | 0.27 | 0.68 | 1.73 | 4.73 | 3.22 | 0.51 |

| 14 | 1900 | Nonadecane | 13.21 | 1.17 | 15.56 | 1.01 | 1.65 | 8.21 | 24.96 | 16.39 | 10.04 |

| 15 | 2000 | Eicosane | 1.39 | 0.10 | 1.50 | 0.57 | 0.15 | 0.75 | 2.04 | 1.43 | 0.04 |

| 16 | 2100 | Heneicosane | 11.86 | 0.58 | 8.28 | 0.18 | 0.86 | 3.54 | 10.91 | 8.40 | 0.03 |

| 17 | 2300 | Tricosane | 2.67 | 0.08 | 1.86 | 1.72 | 0.15 | 0.83 | 2.31 | 1.53 | 0.24 |

| 18 | 2500 | Pentacosane | 1.18 | 0.04 | 0.71 | 1.04 | 0.14 | 1.62 | 0.72 | 0.91 | 0.11 |

| 19 | 2700 | Heptacosane | 1.22 | 0.04 | 0.70 | 3.49 | 0.16 | 1.66 | 0.92 | 0.30 | 0.29 |

| Monoterpenes | 36.04 | 26.53 | 28.35 | 28.3 | 21.59 | 26.08 | 5.52 | 13.53 | 17.37 | ||

| Phenylethanol | 0.16 | 14.48 | 18.42 | 10.55 | 14.08 | 20.69 | 6.69 | 13.36 | 25.05 | ||

| Rose oxides | 0.06 | 1.04 | 0.73 | 2.31 | 0.76 | 1.35 | 0.19 | 0.42 | 2.18 | ||

| Phenylpropenes | 0.11 | 8.27 | 5.84 | 4.85 | 11.38 | 8.55 | 4.34 | 5.6 | 5.55 | ||

| Sesquiterpenes | 3.77 | 0.08 | 0.19 | - | 0.1 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.05 | ||

| Alkanes and alkenes | 37.48 | 2.52 | 31.89 | 8.58 | 3.88 | 19.03 | 47.95 | 32.8 | 11.32 | ||

| Total | 77.56 | 61.20 | 66.27 | 52.28 | 51.03 | 54.08 | 65.88 | 65.51 | 60.14 | ||

| № | Sample | Total neutral sugars, mg/mL | Proteins, µg/mL |

| 1 | BRCC1 | 0.52±0.00b | 156.97±3.99e |

| 2 | BRCC2 | 0.49±0,05b,c | 152.62±2.18e |

| 3 | BRV1 | 0.44±0.01c | 170.56±3.46d |

| 4 | BRV2 | 0.45±0.04c | 155.18±0.73e |

| 5 | BRCC3 | 0.41±0.02c | 206.72±1.81c |

| 6 | BRCC4 | 0.52±0.03b | 234.67±5.08a |

| 7 | BRV3 | 0.64±0.02a | 221.85±1.45b |

| 8 | BRV4 | 0.63±0.02a | 240.31±3.63a |

| № | Sample | GalA, mg/mL (galacturonic acid) | Glc, mg/mL (glucose) | Rha, mg/mL (rhamnose) | Gal, mg/mL (galactose) | Xyl, mg/mL (xylose) |

| 1 | BRCC1 | 1.24±0.11c,d | 4.09±0.27f | 0.48±0.08a | - | - |

| 2 | BRCC2 | 1.02±0.16d | 7.72±0.12d | 0.28±0.01b | - | - |

| 3 | BRV1 | 1.36±0.25c | 6.55±0.14e | 0.18±0.02c | 0.24±0.07c | - |

| 4 | BRV2 | 1.58±0.18b,c | 3.09±0.23g | 0.17±0.02c | 0.47±0.04b | - |

| 5 | BRCC3 | 1.84±0.14b | 8.53±0.10c | 0.25±0.07b | - | - |

| 6 | BRCC4 | 2.34±0.12a | 11.59±0.21b | 0.33±0.01b | 0.17±0.01c | 0.07±0.01b |

| 7 | BRV3 | 1.29±0.14c | 4.12±0.26f | 0.22±0.03b,c | 0.18±0.09c | - |

| 8 | BRV4 | 2.24±0.18а | 15.29±0.11a | 0.27±0.05b | 0.78±0.08a | 0.17±0.01a |

| № | Samples | TPC, mg GAE/mL |

TFC, mg QE/mL |

Antioxidant activity, mM TE/mL | |||

| DPPH | ABTS | FRAP | CUPRAC | ||||

| 1 | BRCC1 | 0.57±0.00b | 0.25±0.00a | 5.81±0.02d | 5.75±0.01c | 5.49±0.05c | 14.18±0.02c |

| 2 | BRCC2 | 0.51±0.00c | 0.21±0.00c | 5.17±0.02e | 4.91±0.08d | 4.67±0.08d | 11.44±0.11d |

| 3 | BRV1 | 0.41±0.03e | 0.19±0.00d | 4.06±0.12f | 3.69±0.03f | 3.65±0.01f | 8.66±0.11f |

| 4 | BRV2 | 0.43±0.00e | 0.21±0.00c | 4.44±0.07f | 4.37±0.19e | 4.14±0.01e | 9.39±0.04e |

| 5 | BRCC3 | 0.48±0.00d | 0.18±0.00d | 5.62±0.02d | 5.46±0.08c | 4.87±0.01d | 11.29±0.04d |

| 6 | BRCC4 | 0.57±0.01b | 0.18±0.00d | 6.27±0.02c | 6.52±0.51b | 6.16±0.19b | 14.49±0.02c |

| 7 | BRV3 | 0.60±0.01a,b | 0.23±0.00b | 6.70±0.22b | 6.71±0.42b | 6.71±0.25a | 15.18±0.02b |

| 8 | BRV4 | 0.63±0.01a | 0.19±0.00d | 7.56±0.16a | 7.24±0.01a | 7.22±0.22a | 15.84±0.02a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).