1. Introduction and Results

Norovirus is the leading cause of acute gastroenteritis worldwide, responsible for an estimated 685 million cases annually, including 200 million among children under five [

2]. The virus contributes to approximately 200,000 deaths each year, with the highest burden in low-income countries [

2]. Beyond its health impact, norovirus imposes a significant economic burden, estimated at

$60 billion globally due to healthcare costs and productivity losses [

2]. In Finland, norovirus is a major cause of gastroenteritis outbreaks, particularly in institutional settings such as long-term care facilities and schools. Norovirus genotyping is conducted as a statutory part of food- and waterborne outbreak investigations [

10]. Viruses in person-to-person transmissions are not routinely genotyped; instead, they are typically included in collaborative research studies. Norovirus genotyping is based on sequencing specific regions of the viral genome, particularly the capsid gene (VP1) and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) gene [

3]. These sequences are then compared to the typing tools implemented by the NoroNet to determine the genotype [

4].

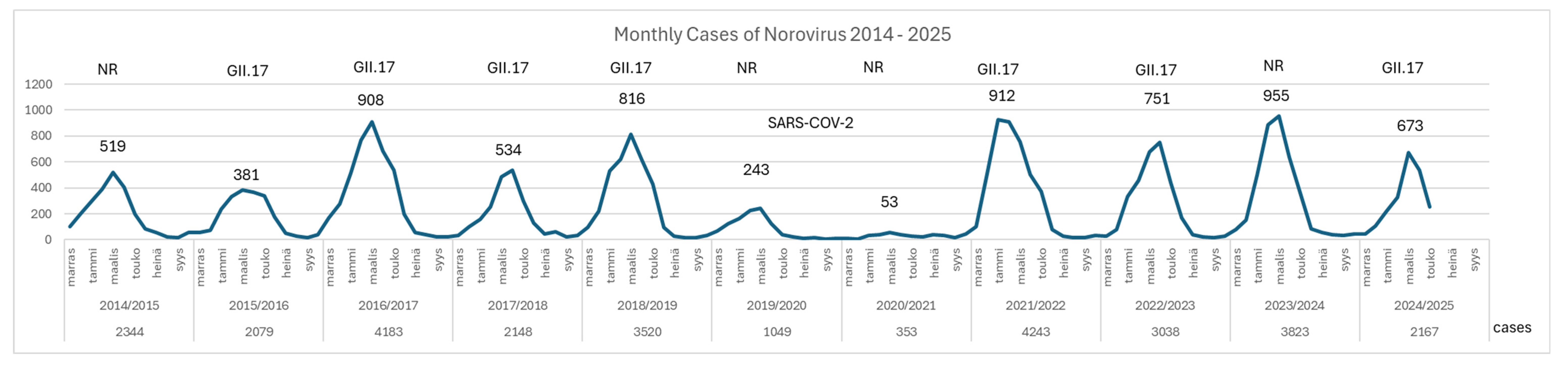

In Finland, laboratory-confirmed norovirus infections are mandatorily reported to the Finnish Infectious Diseases Register (FIDR) as part of a surveillance system coordinated by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL). The reporting is based on nucleic acid detection methods, primarily RT-PCR, which identify norovirus genogroups GI and GII from stool specimens. The analysis of national norovirus surveillance data from the Finnish Infectious Disease Registry (FIDR) between 2014 and 2025 reveals a biennial norovirus notification pattern with higher case numbers observed every other year (

Figure 1). In the three seasons during and following the COVID pandemic (2021/22, 2022/23 and 2023/24), the number of norovirus notifications resembled the levels typically seen during pre-pandemic norovirus epidemic years (2016/17 and 2018/19).

During the 2023/24 season, Finland participated in enhanced norovirus surveillance alongside other European countries and the USA [

1]. A notable increase in GII.17 norovirus outbreaks and sporadic cases occurred in Austria, Germany, France, Ireland, the Netherlands, England, and the United States. This rise in GII.17 prevalence coincided with a decline in the previously dominant GII.4 genotype, with GII.17 accounting for 17% to 64% of all GII detections in the affected countries. In Finland, however, no GII.17 norovirus were detected.

In Finland, the municipal food- and waterborne outbreak investigation groups notify suspected norovirus outbreaks to the Finnish Food and Waterborne Outbreak Registry (FWOR) [

10]. To better understand the emergence of GII.17 in Finland, we reviewed the FWOR notifications from the 2014/15 to 2024/25 seasons (

Table 1). While GII.17 was first detected in Finland in the 2015/16 season, it remained rare and sporadic in subsequent years, with isolated detections in both outbreak-related and sporadic cases. The sporadic cases were selected to monitor the prevalence of the GII.17 strain in non-FWOs and requested from diagnostic laboratories across Finland.

- -

Season starts July and ends June next year

- -

NR stands for no record

- -

* Sporadic case

During the 2024/25 season, FWOR contained 98 outbreak notifications, of which 41 (42%) were suspected to be caused by norovirus (

Table 1). Noroviruses from four outbreaks were genotyped, and GII.17 was confirmed in three of them. Of the twelve sporadic cases, five genotyped as GII.17. The outbreaks occurred in southern, western, and northern Finland, while the sporadic cases were reported in the south and west. This suggests that GII.17 is circulating across the entire country.

In Finland, GII.17 norovirus has been detected in both high-incidence and low-incidence years, indicating that its circulation is not strictly dependent on overall epidemic intensity. Despite the sharp decline in total norovirus cases during the pandemic years (2019/20 and 2020/21), GII.17 re-emerged post-pandemic and was most frequently detected in the 2024/25 season, both in outbreaks and sporadic cases.

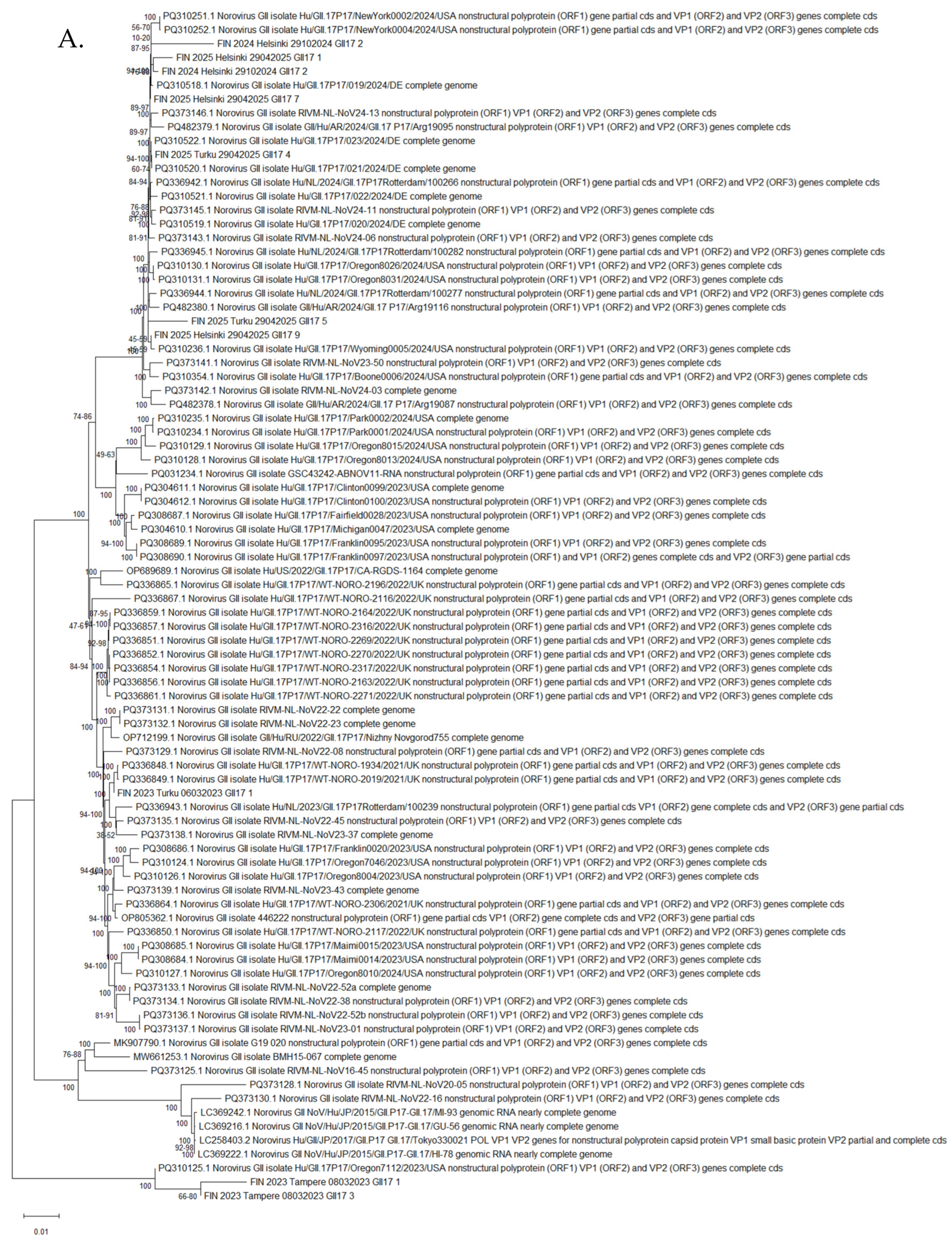

The phylogenetic tree in

Figure 2A based on the capsid gene (VP1) of GII.17 norovirus strains illustrates the genetic relationships between Finnish GII.17 sequences and global reference strains (

Figure 2A). Sequences from Finland, including those recently found, cluster closely with strains from recent years (2023–2025), suggesting that the currently circulating GII.17 strains in Finland are part of the globally emerging lineage that has evolved from earlier variants first detected around 2015 and 2017.

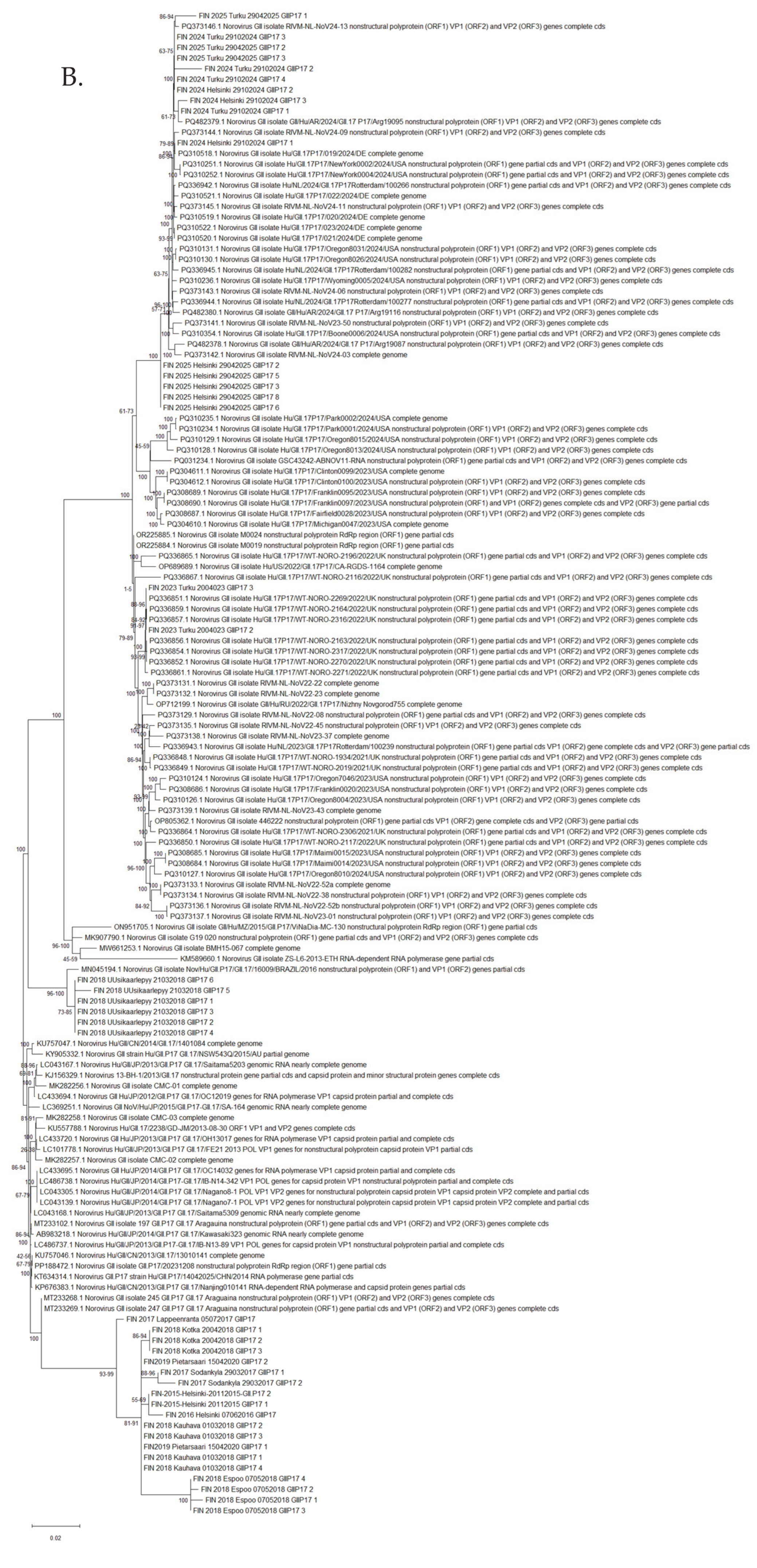

The phylogenetic tree of the polymerase region (GII.P17) is like the capsid tree, Finnish sequences from 2025 also cluster with recent international strains, indicating co-evolution of the polymerase and capsid regions. The presence of closely related sequences in both trees supports the conclusion that the current GII.17 viruses circulating in Finland are genetically like those causing outbreaks in other parts of the world.

2. Discussion

Norovirus GII.17 emerged later in Finland than in Central Europe and Russia, where the virus had already caused widespread outbreaks during the 2023/24 season [

9]. The Finnish GII.17 strains were part of the globally expanding lineage and provided molecular evidence of their delayed introduction and spread in Finland. This phenomenon is not unique, Finland has experienced delayed emergence of epidemic viral pathogens compared to Central and Southern Europe before [5, 6]. The true emergence of GII.17, however, might be undetected, since not all norovirus outbreaks in Finland undergo molecular investigation.

During the COVID-19 pandemic (seasons 2019/20 and 2020/21), no GII.17 norovirus was identified in Finland. Reduced virus transmission can be due to pandemic control measures: less contacts between people, restrictions to dining together and traveling, more hand washing leading to less outbreak investigations. After the pandemic, detection of GII.17 norovirus resumed. The actual burden of GII.17 norovirus in Finland is probably underestimated since sporadic cases likely represent a chain of person-to-person transmission, especially in settings where outbreak investigations are not routinely conducted. The rise in GII.17 detections during the 2024/25 season suggests a shift in genotype dominance and highlights the dynamic nature of norovirus epidemiology. This may partly be due to the population's lack of exposure to norovirus infections during the pandemic, which could have led to a decline in immunity.

Norovirus infections are typically short-lived and self-limiting, and they rarely require hospitalization. As a result, the total number of norovirus cases often remains underreported in official statistics and only small fraction of cases seek medical care or are recorded [13-14]. During the 2024–2025 season, 42% of FWOR notifications were suspected norovirus outbreaks, yet genotyping was performed in only four cases. This reflects the established practice of conducting genotyping only when exact identification is needed for comparing noroviruses in patients and the suspected source. In such cases, expert consultation is often requested from the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL), particularly when a food- or waterborne source is suspected.

The recognition of delayed genotype emergence has important public health implications. Although norovirus infections are clinically similar regardless of genotype, the introduction of a novel strain such as GII.17 may lead to larger outbreaks due to a lower population immunity [11-12]. Norovirus is highly contagious and can spread rapidly in institutional and community settings, often before public health interventions can be fully implemented. Thus, awareness of emerging genotypes in other regions may enhance preparedness by heightening surveillance and outbreak detection, and communication with healthcare providers. The public health authorities could also consider integrating international surveillance data into national risk assessments. Still, without targeted interventions or vaccines, the impact of enhanced surveillance and risk assessments may limit to mitigation rather than prevention. Continued monitoring and international data sharing remain essential tools in mitigating the impact of emerging norovirus strains.

References

- Chhabra, P.; Wong, S.; Niendorf, S.; Lederer, I.; Vennema, H.; Faber, M. ; Nisavanh, A; Jacobsen, S.; Williams, R.; Colgan, A.; Yandle, Z.; Garvey, P.; Al-Hello, H.; Ambert-Balay, K.; Barclay, L.; de Graaf, M.; Celma, C.; Breuer, J.; Vinjé, J.; Douglas, A. Increased circulation of GII.17 noroviruses, six European countries and the United States, 2023 to 2024. Euro Surveill. 2024 Sep;29(39):2400625. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platts-Mills, J.A.; Taniuchi M.; Uddin, Md.J; Sobuz, S. U.; Mahfuz, M.; Gaffar, S.M.A.,

Mondal, D.; Hossain, M.I.; Islam M.M., Ahmed, A.M S.; Petri W. A., Haque, R.; Houpt, E.R; Ahmed, T.

Association between enteropathogens and malnutrition in children aged 6–23 mo in Bangladesh: a casecontrol

study1, 2, 3. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2017 May; 105(5): 1132-1138. [CrossRef]

- Vinje, J.; Hamidjaja, R.A.; Sobsey, M.D.; (2004). Development and application of a capsid VP1 (region D) based reverse transcription PCR assay for genotyping of genogroup I and II noroviruses. J Virol Methods 116;109-117.

- Norovirus Typing Tool Version 2.0. Available online: https://mpf.rivm.nl/mpf/norovirus/typingtool/.

- Polkowska, A.; Rönnqvist, M.; Lepistö, O.; Roivainen, M.; Maunula, L.; Huusko, S.; Toikkanen, S.; Rimhanen-Finne, R.; Outbreak of gastroenteritis caused by norovirus GII.4 Sydney variant after a wedding reception at a resort/activity centre, Finland, August 2012. Epidemiol Infect. 2014 Sep;142(9):1877-83. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813002847. Epub 2013 Nov 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summa, M.; Tuutti, E.; Al-Hello, H.; Huttunen, L.M.; Rimhanen-Finne R. Norovirus GII.17 Caused Five Outbreaks Linked to Frozen Domestic Bilberries in Finland, 2019. Food Environ Virol. 2024 Jun;16(2):180-187. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar. S; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis Version 12 for Adaptive and Green Computing. Mol Biol Evol. 2024 Dec 6;41(12):msae263. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Nei, M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 1993 May;10(3):512-26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Beek, J.; de Graaf, M.; Al-Hello, H.; Allen, D.J.; Ambert-Balay, K.; Botteldoorn, N.; Brytting, M.; Buesa, J.; Cabrerizo, M.; Chan, M.; Cloak, F.; Di Bartolo, I.; Guix, S.; Hewitt, J.; Iritani, N.; Jin, M.; Johne, R.; Lederer, I.; Mans, J.; Martella, V.; Maunula, L.; McAllister, G.; Niendorf, S.; Niesters, H.G.; Podkolzin, A.T., Poljsak-Prijatelj, M.; Rasmussen, L.D.; Reuter, G.; Tuite, G.; Kroneman, A.; Vennema, H.; Koopmans, M.P.G.; NoroNet. Molecular surveillance of norovirus, 2005-16: an epidemiological analysis of data collected from the NoroNet network. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018 May;18(5):545-553. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnish legislation. Available online: https://www.finlex.fi/fi/lainsaadanto/2011/1365.

- Lopman, B.; Vennema, H.; Kohli, E.; Pothier, P.; Sanchez, A.; Negredo, A.; Buesa, J.; Schreier, E.; Reacher, M.; Brown, D.; Gray, J.; Iturriza, M.; Gallimore, C.; Bottiger, B.; Hedlund, K.O.; Torvén, M.; von Bonsdorff, C.H.; Maunula, L.; Poljsak-Prijatelj, M.; Zimsek, J.; Reuter, G.; Szücs, G.; Melegh, B.; Svennson, L.; van Duijnhoven, Y.; Koopmans M. Increase in viral gastroenteritis outbreaks in Europe and epidemic spread of new norovirus variant. Lancet. 2004 Feb 28;363(9410):682-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, E.T.; Bull, R.A.; Greening, G.E.; Hewitt, J.; Lyon, M.J.; Marshall, J.A.; McIver, C.J.; Rawlinson, W.D.; White, P.A. Epidemics of gastroenteritis during 2006 were associated with the spread of norovirus GII.4 variants 2006a and 2006b. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Feb 1;46(3):413-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robilotti, E.; Deresinski, S.; Pinsky, B.A. Norovirus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015 Jan;28(1):134-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rha, B.; Burrer, S., Park, S.; Trivedi, T.; Parashar, U.D.; Lopman, B.A. Emergency department visit data for rapid detection and monitoring of norovirus activity, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013 Aug;19(8):1214-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).