1. Introduction

The widespread adoption of mesh-based techniques in inguinal hernia repair has led to a substantial reduction in recurrence rates—estimated between 50% and 75% [1]. Consequently, clinical attention has shifted from the prevention of recurrence to the management of postoperative complications, particularly chronic groin pain. While post-herniorrhaphy discomfort typically resolves within two months [2], a subset of patients continues to experience persistent pain beyond this period: this condition is known as chronic postoperative inguinal pain (CPIP) [3,4].

Originally defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) in 1986 as pain persisting for more than three months after surgery, CPIP was later refined by the HerniaSurge Group [2018]: this updated definition includes pain that is moderate to severe, lasts beyond three months, and interferes with daily activities such as movement, sleep, or social interaction [5,6,7]. However, due to ongoing mesh-related inflammation beyond the three-month period, some experts advocate extending the diagnostic threshold to six months [8].

A review of the literature offers a comprehensive overview of CPIP following inguinal hernioplasty across various studies and geographic regions (

Table 1).

2. Epidemiological Landscape

The international literature on CPIP reveals a complex and heterogeneous picture. Incidence rates vary widely—from 6% in Forester’s UK-based study [2021] to an exceptional 64.3% in Niebuhr’s German cohort (2018)—highlighting the multifactorial nature of CPIP [10,18]. This variability reflects a dynamic interplay of factors, including surgical technique, follow-up duration, patient selection criteria, regional healthcare practices, and methodological consistency.

A clear trend emerges regarding follow-up duration. Studies with shorter postoperative evaluations [3–6 months], such as Lo (2021: 8.7%) and Forester [2021: 6%], tend to report lower CPIP rates [9,10]. In contrast, studies with extended follow-up periods [≥12 months], including Lundström (2018: 15.2%) and Jeroukhimov (2014: 32.8%), consistently report higher pain prevalence [16,25]. This suggests that early assessments may underestimate the true burden of chronic pain, emphasizing the importance of long-term surveillance in clinical research.

3. Surgical Technique and Geographic Variation

Surgical technique plays a pivotal role in CPIP outcomes. Laparoscopic repairs generally yield lower CPIP rates compared to open approaches. For example, Lo (2021) and Gutlic (2016) report rates below 9% in laparoscopic cohorts, supporting the hypothesis that minimally invasive techniques may reduce nerve trauma and mesh-related inflammation [9,23]. However, this advantage is not absolute. Niebuhr’s 2018 study presents a striking anomaly: a CPIP rate of 64.3% despite exclusive use of laparoscopy [18]. Given the large sample size (20,004 patients), this finding raises methodological concerns and suggests the influence of confounding variables such as non-standardized surgical protocols, selection bias, or inconsistencies in pain assessment. It serves as a reminder that no technique is inherently superior without rigorous execution and individualized patient care. According to a more recent paper published in 2025 by Liu et al. chronic pain in open inguinal hernia surgical repair group was more frequent than that in laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgical repair group (4.8% vs 1.88%, p < 0.05) [29].

Geographic variation further complicates the CPIP landscape. European studies often report moderate to high rates—Fränneby (2006, Sweden): 31%, Poobalan (2008, UK): 30%, and Nienhuijs (2005, Netherlands): 43.3%—suggesting potential influences from cultural attitudes toward pain, surgical training, and healthcare infrastructure, including access to pain management and rehabilitation services. In contrast, Asian studies such as Lo (2021, Taiwan) and Min (2020, China: 26.8%) tend to report lower or intermediate rates, raising questions about regional differences in clinical practice, mesh selection, perioperative care, and even genetic predisposition to chronic pain [3,9,11,20,30,31]. Surgical expertise may not affect the incidence of CPIP: Swedish surgeon de la Croix recently (2025) observed that the incidence of CPIP was 15.4% in patients operated by specialist surgeons and 15.5% in patients operated by surgical residents [32].

4. Strengths and Limitations of the Literature

From a critical standpoint, the dataset presents several strengths. It encompasses a wide range of countries, surgical techniques, and follow-up durations, offering a broad overview of CPIP across diverse clinical settings. The inclusion of large patient samples—such as Niebuhr’s 2018 cohort of over 20,000 individuals—provides robust statistical power. However, limitations are equally evident [18]. The heterogeneity in study designs, particularly regarding follow-up intervals and definitions of CPIP, complicates direct comparisons. The presence of “NR” (Not Reported) values in several studies further obscures the timeline of pain evaluation, while outlier data—such as the unexpectedly high CPIP rate in Niebuhr’s laparoscopic series—warrants deeper methodological scrutiny to rule out bias or inconsistencies.

Clinically, these findings underscore the urgent need for standardized pain assessment tools to improve data consistency and comparability. Instruments such as the DN4 questionnaire should be routinely employed to distinguish between neuropathic and nociceptive pain, thereby refining diagnostic accuracy. While laparoscopic approaches generally appear to offer better outcomes in terms of CPIP reduction, the presence of high pain rates in certain laparoscopic cohorts calls for further investigation into surgical technique, perioperative management, and patient-specific factors. Moreover, regional differences in CPIP prevalence should be explored in greater depth to develop tailored pain prevention strategies that align with local healthcare infrastructure and demographic profiles.

5. Neuropathic vs. Nociceptive CPIP: Diagnostic Challenges and Clinical Implications

In routine clinical practice, distinguishing between neuropathic and non-neuropathic CPIP remains a significant challenge. Although the underlying mechanisms differ, their clinical manifestations often overlap, complicating accurate classification [33,34]. A reanalysis of selected studies reporting CPIP incidence reveals that only a limited number of authors have attempted to differentiate between neuropathic and nociceptive groin pain—highlighting a notable gap in diagnostic rigor (

Table 2).

Most of these studies focus on open surgical techniques, with only Loos (2007) including laparoscopic procedures [35]. The presence of laparoscopy in this cohort may influence CPIP outcomes, potentially altering the balance between neuropathic and nociceptive pain.

6. Neuropathic and Nociceptive Pain Profiles

Neuropathic CPIP rates vary widely. Ergönenç (2017) reports the highest proportion [73.7%], suggesting a strong neuropathic component likely due to limited nerve preservation during open repair [19]. Bande (2020) and Nienhuijs (2005) report similar rates (38.5% and 40.3%, respectively), possibly reflecting comparable surgical techniques or perioperative protocols [12,30]. Loos (2007), with a rate of 46.5%, occupies a mid-range position—potentially influenced by the inclusion of laparoscopic procedures, which may reduce nerve trauma [35].

Conversely, non-neuropathic CPIP rates show an inverse trend. Ergönenç (2017) reports the lowest rate (26.3%), while Bande (2020) and Nienhuijs (2005) report higher rates (61.5% and 59.7%) [12,19,30]. These discrepancies may stem from differences in pain classification criteria, diagnostic methodology, or postoperative nerve management. The relatively balanced distribution in Loos (2007) further supports the hypothesis that surgical approach—particularly laparoscopy—may influence the type of pain experienced [35].

7. Limitations and Methodological Considerations

Several limitations must be acknowledged. Sample sizes vary significantly—from 61 patients in Ergönenç (2017) to 239 in Bande (2020)—potentially affecting statistical robustness [12,19]. Additionally, the lack of precise differentiation between open techniques (e.g., Lichtenstein vs. Shouldice) as well as between TAPP (Transabdominal preperitoneal) versus TEP (Totally Extraperitoneal) mini invasive techniques may obscure finer trends and make comparison between different surgical techniques more difficult [29].

Inconsistencies in pain classification methodology—especially in distinguishing neuropathic from nociceptive pain—further limit comparability across studies.

From a clinical standpoint, the high prevalence of neuropathic pain in Ergönenç (2017) underscores the importance of meticulous nerve identification and preservation during hernia repair [19]. The potential protective role of laparoscopy, as suggested by Loos (2007), warrants further investigation to determine whether minimally invasive techniques reduce neuropathic complications [35]. Ultimately, pain management strategies should be tailored to individual patient risk profiles, with particular attention to surgical technique, nerve handling, and postoperative monitoring.

8. Toward a Structured Diagnostic Approach

These findings offer valuable insights into the relative prevalence of neuropathic pain among CPIP cases. Notably, Ergönenç (2017) reported a striking 73.7% rate of neuropathic CPIP in an open repair cohort, suggesting nerve injury as a predominant mechanism in certain surgical contexts [19]. Other studies show a more balanced distribution, indicating that both neuropathic and nociceptive pathways contribute meaningfully to postoperative pain.

Despite these observations, the limited number of studies performing this subclassification highlights a critical gap in the literature. Without consistent use of validated diagnostic tools and standardized definitions, the true burden of neuropathic CPIP remains difficult to quantify. Further research is essential to elucidate risk factors, refine diagnostic criteria, and optimize surgical techniques to minimize both forms of chronic pain.

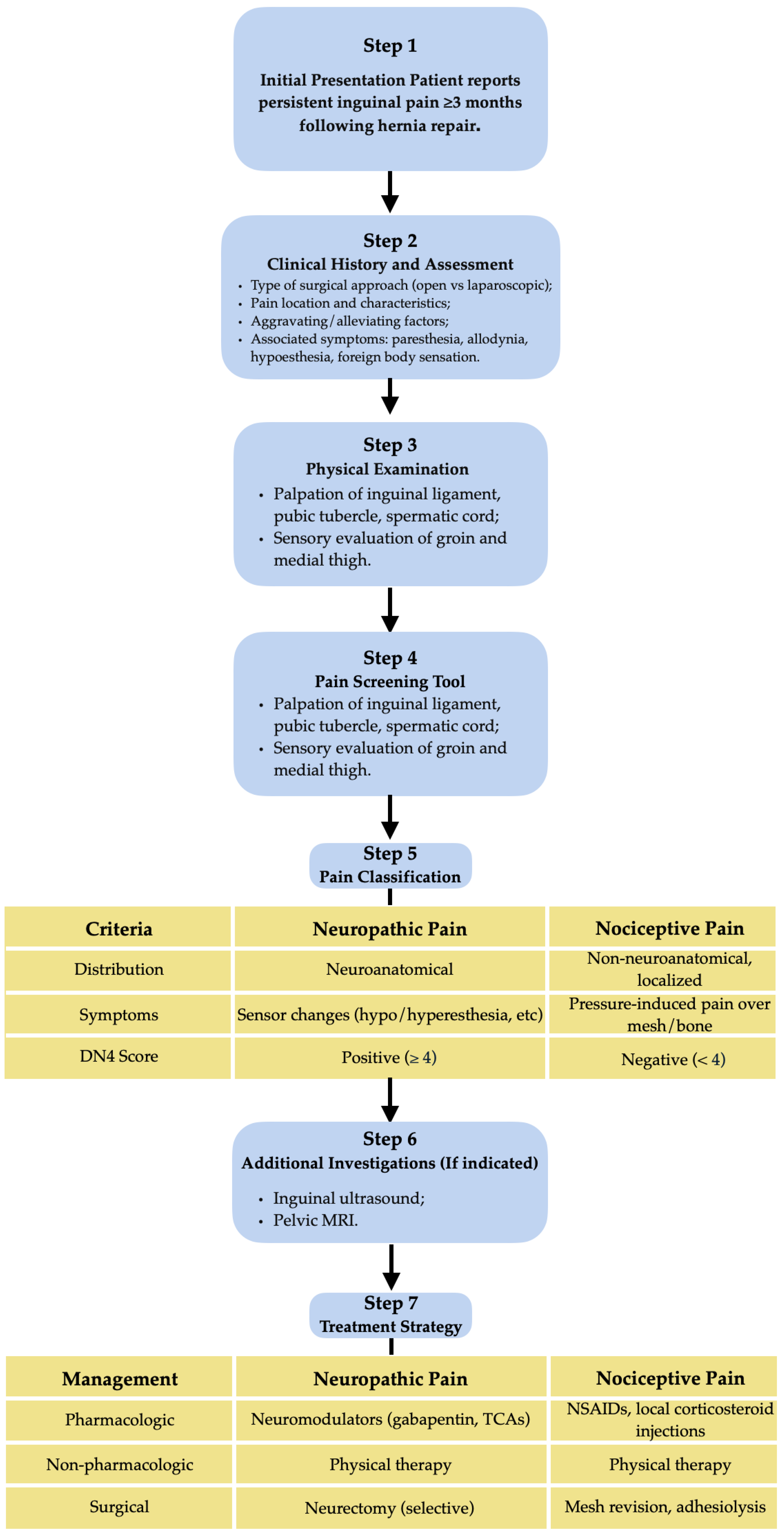

Given the diagnostic complexity and multifactorial nature of CPIP, a structured clinical algorithm can assist surgeons and pain specialists in navigating evaluation and treatment. Such a pathway should integrate current evidence and clinical reasoning to distinguish between pain types, guide appropriate investigations, and tailor management strategies to individual patient profiles. This approach emphasizes early recognition, standardized assessment tools, and a stepwise therapeutic plan aimed at minimizing long-term morbidity (

Figure 1).

9. Conclusions

Chronic postoperative inguinal pain (CPIP) remains a significant and multifaceted challenge in hernia surgery. The wide variability in reported incidence rates across international studies reflects the complexity of its aetiology and the influence of numerous factors—including surgical technique, follow-up duration, geographic context, and diagnostic methodology. In example, Hermann reported that 9.6% out of 11,221 patients who underwent repair of monolateral inguinal hernia in Germany had preoperative pain that disappeared after surgery, but 8.5% of patients after surgery complained of novel pain in the same anatomical region [36].

While laparoscopic approaches generally demonstrate lower CPIP rates, exceptions such as Niebuhr’s 2018 study underscore the need for cautious interpretation and emphasize that surgical precision and individualized care are paramount [18]. The distinction between neuropathic and nociceptive pain is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective management, yet it is often overlooked in clinical practice and underreported in the literature.

Studies that attempt this subclassification reveal substantial differences in pain profiles, suggesting that nerve handling, mesh positioning, and postoperative care play critical roles in CPIP development. The high prevalence of neuropathic pain in certain cohorts reinforces the importance of nerve preservation strategies and the potential value of minimally invasive techniques. The age of the patients may affect the type of postoperative pain: in Denmark 8.6% (95% CI, 7.5-10) of 2486 adolescents (10-19 years) had chronic pain during sexual activity after unilateral inguinal surgical hernia repair [37].

Methodological inconsistencies—including variable follow-up durations, heterogeneous definitions of CPIP, and disparities in sample sizes—limit the comparability of existing data and hinder the development of standardized treatment protocols. To advance clinical understanding and improve patient outcomes, future research must prioritize uniform diagnostic criteria, validated pain assessment tools, and long-term follow-up. Moreover, regional differences in CPIP incidence should be explored to tailor prevention and management strategies to specific healthcare environments.

Ultimately, reducing the burden of CPIP requires a multidimensional approach that integrates surgical expertise, diagnostic rigor, and patient-centred care. By refining techniques, standardizing evaluation, and acknowledging the diverse nature of postoperative pain, clinicians can move toward more effective prevention and treatment of this often-debilitating condition.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, R.C. and P.B.; methodology, R.C. and B.C.; validation, G.C., F.B. and M.L.; investigation, P.B., P.F. and R.C.; resources, S.L.; data curation, R.C. and C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C., P.B; writing—review and editing, L.T.; visualization, P.F. and L.T.; supervision, R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CPIP |

Chronic postoperative inguinal pain |

| IASP |

International Association for the Study of Pain |

| NR |

Not Reported |

| DN4 |

Douleur Neuropathique 4 |

| TAPP |

Transabdominal Preperitoneal |

| TEP |

Totally Extraperitoneal |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| PMID |

PubMed Identifier |

References

- Scott NW, McCormack K, Graham P, Go PM, Ross SJ, Grant AM. Open mesh versus non-mesh for repair of femoral and inguinal hernia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(4):CD002197.

- Bay-Nielsen M, Perkins FM, Kehlet H, Danish Hernia Database. Pain and functional impairment 1 year after inguinal herniorrhaphy: a nationwide questionnaire study. Ann Surg. 2001 Jan;233(1):1–7. [CrossRef]

- Poobalan AS, Bruce J, Smith WCS, King PM, Krukowski ZH, Chambers WA. A review of chronic pain after inguinal herniorrhaphy. Clin J Pain. 2003;19(1):48–54. [CrossRef]

- Chapman CR, Vierck CJ. The Transition of Acute Postoperative Pain to Chronic Pain: An Integrative Overview of Research on Mechanisms. J Pain. 2017 Apr;18(4):359.e1-359.e38.

- Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Prepared by the International Association for the Study of Pain, Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain Suppl. 1986;3:S1-226.

- Stabilini C, van Veenendaal N, Aasvang E, Agresta F, Aufenacker T, Berrevoet F, et al. Update of the international HerniaSurge guidelines for groin hernia management. BJS Open. 2023 Oct 20;7(5):zrad080. [CrossRef]

- HerniaSurge Group. International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia. 2018 Feb;22(1):1–165.

- Faessen JL, Stoot JHMB, van Vugt R. Safety and efficacy in inguinal hernia repair: a retrospective study comparing TREPP, TEP and Lichtenstein (SETTLE). Hernia. 2021 Oct;25(5):1309–15. [CrossRef]

- Lo CW, Chen YT, Jaw FS, Yu CC, Tsai YC. Predictive factors of post-laparoscopic inguinal hernia acute and chronic pain: prospective follow-up of 807 patients from a single experienced surgeon. Surg Endosc. 2021 Jan;35(1):148–58. [CrossRef]

- Forester B, Attaar M, Chirayil S, Kuchta K, Denham W, Linn JG, et al. Predictors of chronic pain after laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Surgery. 2021 Mar;169(3):586–94.

- Min L, Yong P, Yun L, Balde AI, Chang Z, Qian G, et al. Propensity score analysis of outcomes between the transabdominal preperitoneal and open Lichtenstein repair techniques for inguinal hernia repair: a single-center experience. Surg Endosc. 2020 Dec;34(12):5338–45.

- Bande D, Moltó L, Pereira JA, Montes A. Chronic pain after groin hernia repair: pain characteristics and impact on quality of life. BMC Surg. 2020 Jul 6;20(1):147. [CrossRef]

- Köckerling F, Lorenz R, Hukauf M, Grau H, Jacob D, Fortelny R, et al. Influencing Factors on the Outcome in Female Groin Hernia Repair: A Registry-based Multivariable Analysis of 15,601 Patients. Ann Surg. 2019 Jul;270(1):1–9.

- Chinchilla-Hermida PA, Baquero-Zamarra DR, Guerrero-Nope C, Bayter-Mendoza EF. Incidence of chronic post-surgical pain and its associated factors in patients taken to inguinal hernia repair. Colombian Journal of Anesthesiology. 2017 Oct 1;45(4):291–9.

- Andercou O, Olteanu G, Stancu B, Mihaileanu F, Chiorescu S, Dorin M. Risk factors for and prevention of chronic pain and sensory disorders following inguinal hernia repair. Ann Ital Chir. 2019;90:442–6.

- Lundström KJ, Holmberg H, Montgomery A, Nordin P. Patient-reported rates of chronic pain and recurrence after groin hernia repair. Br J Surg. 2018 Jan;105(1):106–12. [CrossRef]

- Matikainen M, Aro E, Vironen J, Kössi J, Hulmi T, Silvasti S, et al. Factors predicting chronic pain after open inguinal hernia repair: a regression analysis of randomized trial comparing three different meshes with three fixation methods (FinnMesh Study). Hernia. 2018 Oct;22(5):813–8.

- Niebuhr H, Wegner F, Hukauf M, Lechner M, Fortelny R, Bittner R, et al. What are the influencing factors for chronic pain following TAPP inguinal hernia repair: an analysis of 20,004 patients from the Herniamed Registry. Surg Endosc. 2018 Apr;32(4):1971–83.

- Ergönenç T, Beyaz SG, Özocak H, Palabıyık O, Altıntoprak F. Persistent postherniorrhaphy pain following inguinal hernia repair: A cross-sectional study of prevalence, pain characteristics, and effects on quality of life. Int J Surg. 2017 Oct;46:126–32. [CrossRef]

- Olsson A, Sandblom G, Fränneby U, Sondén A, Gunnarsson U, Dahlstrand U. Impact of postoperative complications on the risk for chronic groin pain after open inguinal hernia repair. Surgery. 2017 Feb;161(2):509–16.

- Schioldann J, Berrios GE. “My insanity in the year 1783”, by C.S. Andresen (1801). Hist Psychiatry. 2020 Dec;31(4):495–510.

- Pierides GA, Paajanen HE, Vironen JH. Factors predicting chronic pain after open mesh based inguinal hernia repair: A prospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2016 May;29:165–70.

- Gutlic N, Rogmark P, Nordin P, Petersson U, Montgomery A. Impact of Mesh Fixation on Chronic Pain in Total Extraperitoneal Inguinal Hernia Repair (TEP): A Nationwide Register-based Study. Ann Surg. 2016 Jun;263(6):1199–206.

- Langeveld HR, Klitsie P, Smedinga H, Eker H, Van’t Riet M, Weidema W, et al. Prognostic value of age for chronic postoperative inguinal pain. Hernia. 2015 Aug;19(4):549–55. [CrossRef]

- Jeroukhimov I, Wiser I, Karasic E, Nesterenko V, Poluksht N, Lavy R, et al. Reduced postoperative chronic pain after tension-free inguinal hernia repair using absorbable sutures: a single-blind randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2014 Jan;218(1):102–7.

- Nikkolo C, Murruste M, Vaasna T, Seepter H, Tikk T, Lepner U. Three-year results of randomised clinical trial comparing lightweight mesh with heavyweight mesh for inguinal hernioplasty. Hernia. 2012 Oct;16(5):555–9. [CrossRef]

- Reinpold W. Risk factors of chronic pain after inguinal hernia repair: a systematic review. Innovative Surgical Sciences. 2017 Jun 1;2(2):61–8.

- Hompes R, Vansteenkiste F, Pottel H, Devriendt D, Van Rooy F. Chronic pain after Kugel inguinal hernia repair. Hernia. 2008 Apr;12(2):127–32. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Shen J, Liu N, Liu Z, Zhu X, Zhong M, et al. Comparison of open and laparoscopic preperitoneal tension-free repair of groin hernia: a prospective nonrandomized controlled study. Surg Endosc. 2025 Jul 29;

- Nienhuijs SW, Boelens OBA, Strobbe LJA. Pain after anterior mesh hernia repair. J Am Coll Surg. 2005 Jun;200(6):885–9. [CrossRef]

- Fränneby U, Sandblom G, Nordin P, Nyrén O, Gunnarsson U. Risk factors for long-term pain after hernia surgery. Ann Surg. 2006 Aug;244(2):212–9.

- de la Croix H, Montgomery A, Holmberg H, Melkemichel M, Nordin P. Surgical expertise and risk of long-term complications following groin hernia mesh repair in sweden: a prospective, patient-reported, nationwide register study. Int J Surg. 2025 Jul 9; [CrossRef]

- Kwee E, Langeveld M, Duraku LS, Hundepool CA, Zuidam M. Surgical Treatment of Neuropathic Chronic Postherniorrhaphy Inguinal Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024 Jan;13(10):2812. [CrossRef]

- Taha-Mehlitz S, Taha A, Janzen A, Saad B, Hendie D, Ochs V, et al. Is pain control for chronic neuropathic pain after inguinal hernia repair using endoscopic retroperitoneal neurectomy effective? A meta-analysis of 142 patients from 1995 to 2022. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2023 Jan 18;408(1):39.

- Loos MJA, Roumen RMH, Scheltinga MRM. Classifying post-herniorrhaphy pain syndromes following elective inguinal hernia repair. World J Surg. 2007 Sep;31(9):1760–5.

- Herrmann E, Schindehütte M, Kindl G, Reinhold AK, Aulbach F, Rose N, et al. Chronic postsurgical inguinal pain: incidence and diagnostic biomarkers from a large German national claims database. Br J Anaesth. 2025 Jun;134(6):1746–55. [CrossRef]

- Reistrup H, Fonnes S, Rosenberg J. Chronic pain and sexual dysfunction after groin hernia repair in adolescents: a nationwide survey. ANN SURG [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 1]; Available from: https://research.regionh.dk/en/publications/chronic-pain-and-sexual-dysfunction-after-groin-hernia-repair-in-.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).