1. The Collatz Problem Leads to a Short Computer Program That Computes in the Limit a Function of Unknown Computability

Definition 1 (cf. [

10], pp. 233–235).

A computation in the limit of a function is a semi-algorithm which takes as input a non-negative integer n and for every prints a non-negative integer such that .

By Definition 1, a function is computable in the limit when there exists an infinite computation which takes as input a non-negative integer n and prints a non-negative integer on each iteration and prints on each sufficiently high iteration.

It is known that there exists a limit-computable function which is not computable, see Theorem 1. Every known proof of this fact does not lead to the existence of a short computer program that computes f in the limit. So far, short computer programs can only compute in the limit functions from to whose computability is proven or unknown.

MuPAD is a part of the Symbolic Math Toolbox in MATLAB R2019b. By Lemma 1, the following program in MuPAD computes in the limit a function .

input("Input a non-negative integer n",n):

while TRUE do

print(sign(n)):

n:=sign(n-1)*(2*n+(1-(-1)^n)*(5*n+2))/4:

end_while:

The computability of

is unknown, see [

1], p. 79. The Collatz conjecture implies that

for every

.

2. A Limit-Computable Function Which Eventually Dominates Every Computable

Function

Theorem 1.([9] p. 118). There exists a limit-computable function which eventually dominates every computable function .

We present an alternative proof of Theorem 1. For

,

denotes the smallest

such that if a system of equations

has a solution in

, then

has a solution in

. The function

is computable in the limit and eventually dominates every computable function

, see [

12]. The term

"dominated" in the title of [

12] means

"eventually dominated".

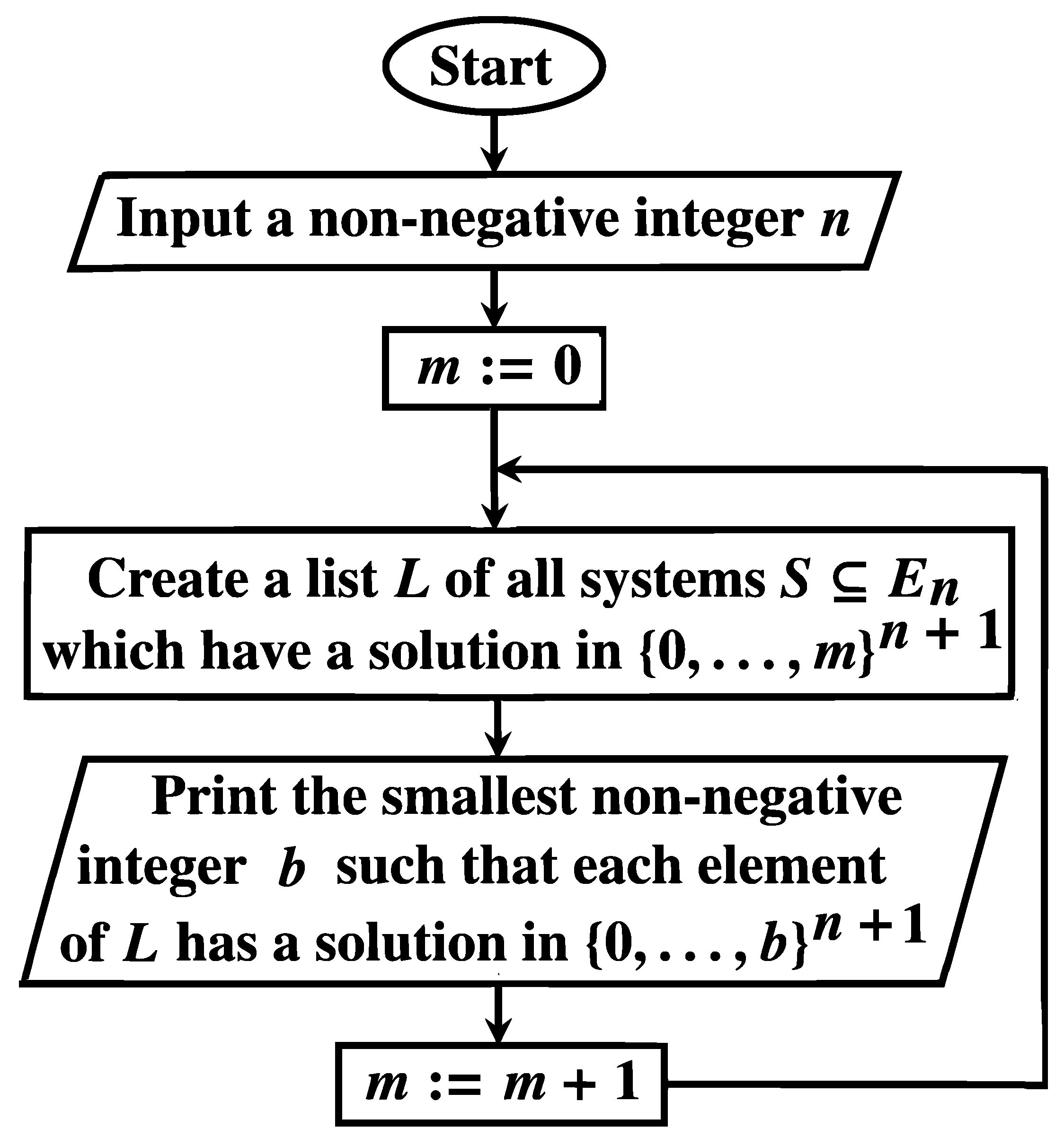

Flowchart 1 shows a semi-algorithm which computes

in the limit, see [

12].

3. A Short Program in MuPAD That Computes f in the Limit

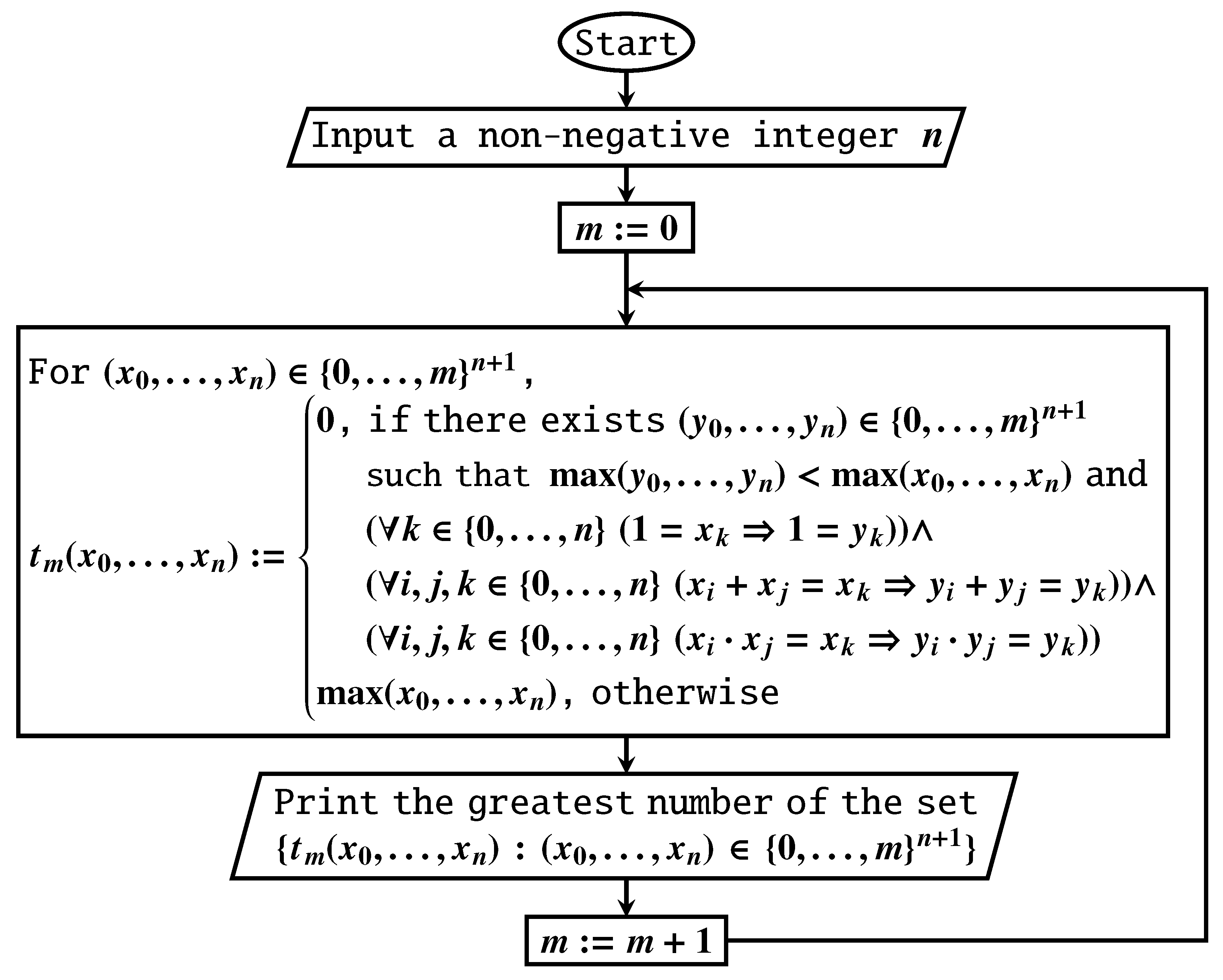

Flowchart 2 shows a simpler semi-algorithm which computes

in the limit.

Lemma 2. For every , the number printed by Flowchart 2 does not exceed the number printed by Flowchart 1.

Proof. For every

,

□

Lemma 3. For every , the number printed by Flowchart 1 does not exceed the number printed by Flowchart 2.

Proof. Let

. For every system of equations

, if

and

solves

, then

solves the following system of equations:

□

Theorem 2. For every , Flowcharts 1 and 2 print the same number.

Proof. It follows from Lemmas 2 and 3. □

Definition 2.

An approximation of a tuple is a tuple such that

Observation 1. There exists a set

such that

and every tuple

possesses an approximation in

.

Observation 2.

equals the smallest such that every tuple possesses an approximation in .

Observation 3. For every , Flowcharts 1 and 2 print the smallest such that every tuple possesses an approximation in .

The following program in MuPAD implements the semi-algorithm shown in Flowchart 2.

input("Input a non-negative integer n",n):

m:=0:

while TRUE do

X:=combinat::cartesianProduct([s $s=0..m] $t=0..n):

Y:=[max(op(X[u])) $u=1..(m+1)^(n+1)]:

for p from 1 to (m+1)^(n+1) do

for q from 1 to (m+1)^(n+1) do

v:=1:

for k from 1 to n+1 do

if 1=X[p][k] and 1<>X[q][k] then v:=0 end_if:

for i from 1 to n+1 do

for j from i to n+1 do

if X[p][i]+X[p][j]=X[p][k] and X[q][i]+X[q][j]<>X[q][k] then v:=0 end_if:

if X[p][i]*X[p][j]=X[p][k] and X[q][i]*X[q][j]<>X[q][k] then v:=0 end_if:

end_for:

end_for:

end_for:

if max(op(X[q]))<max(op(X[p])) and v=1 then Y[p]:=0 end_if:

end_for:

end_for:

print(max(op(Y))):

m:=m+1:

end_while:

For

,

denotes the smallest

such that if a system of equations

has a solution in

, then

has a solution in

. From [

12] and Lemma 3 in [

11], it follows that the function

is computable in the limit and eventually dominates every computable function

. A bit shorter program in

MuPAD computes

h in the limit.

4. A Limit-Computable Function of Unknown Computability Which

Eventually Dominates Every Function with a Single-Fold Diophantine Representation

The Davis-Putnam-Robinson-Matiyasevich theorem states that every listable set

has a Diophantine representation, that is

for some polynomial

W with integer coefficients, see [

6]. The representation

(R) is said to be single-fold, if for any

the equation

has at most one solution

.

Hypothesis 1 ([

2,

3,

4,

5] pp. 341–342, [

7] p. 42, [

8] p. 745).

Every listable set has a single-fold Diophantine representation.

For , denotes the smallest such that if a system of equations has a unique solution in , then this solution belongs to . The computability of is unknown.

Theorem 3. The function is computable in the limit and eventually dominates every function with a single-fold Diophantine representation.

Proof. This is proved in [

12].

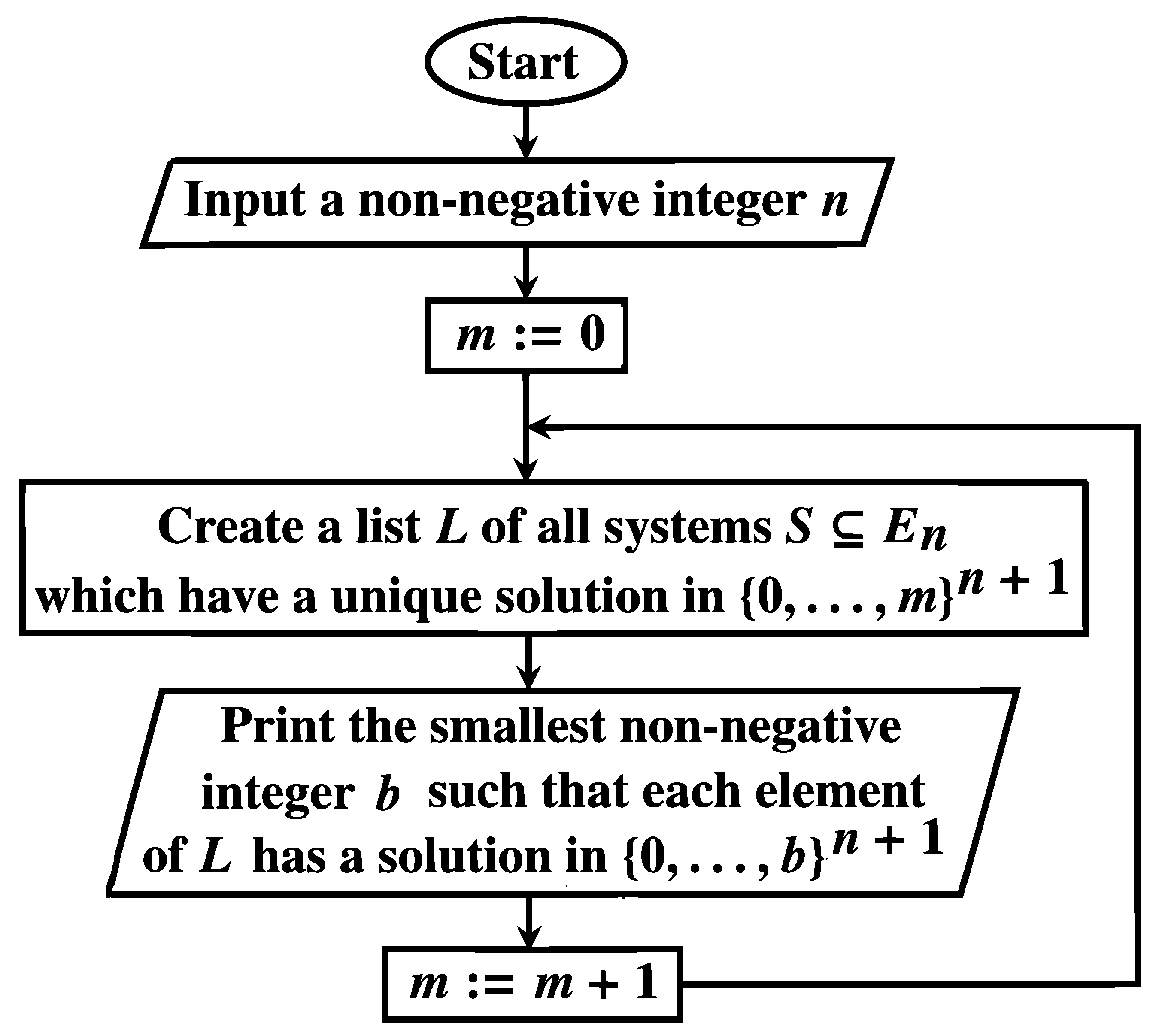

Flowchart 3 shows a semi-algorithm which computes

in the limit, see [

12]. □

5. A Short Program in MuPAD That Computes in the Limit

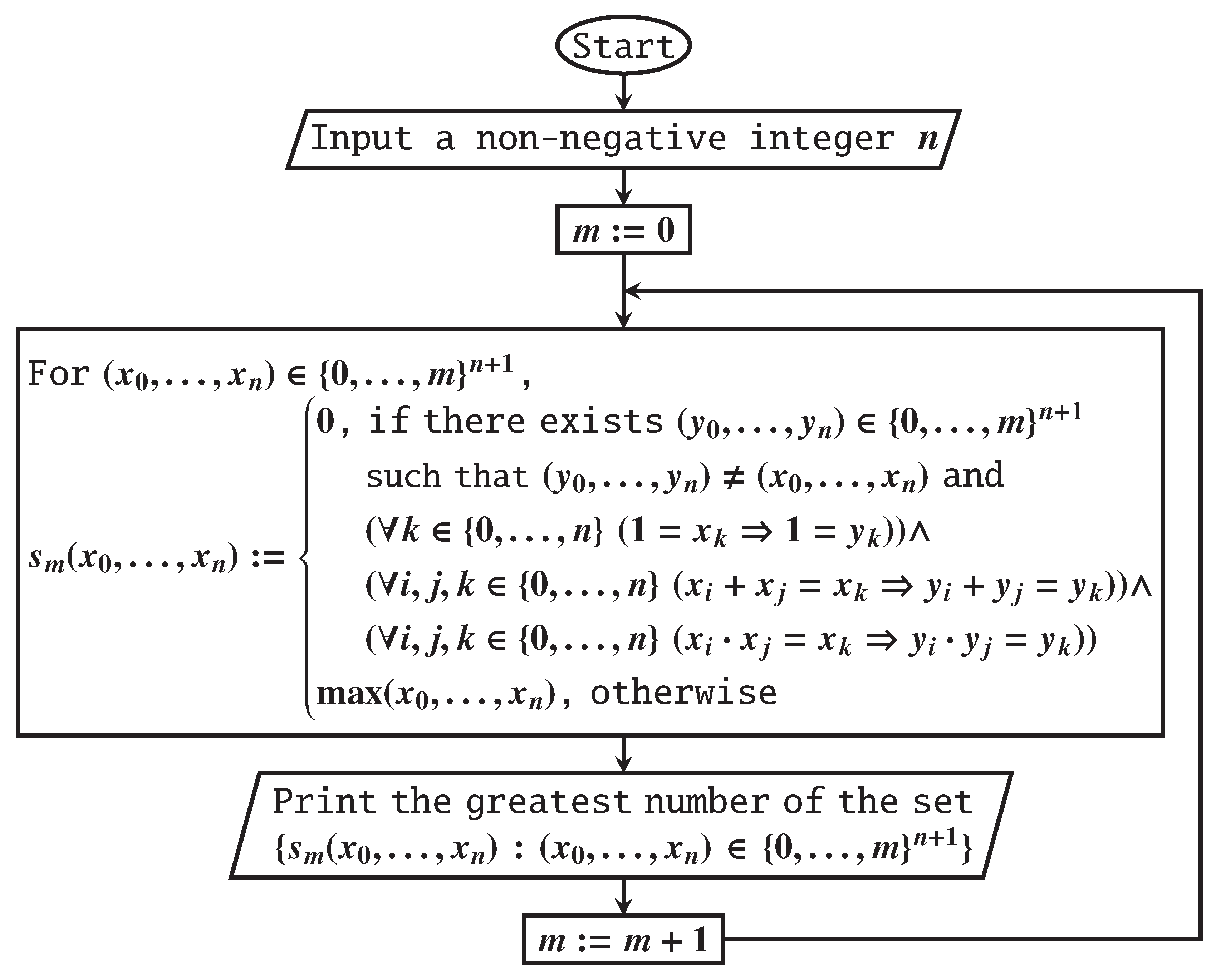

Flowchart 4 shows a simpler semi-algorithm which computes

in the limit.

Lemma 4. For every , the number printed by Flowchart 4 does not exceed the number printed by Flowchart 3.

Proof. For every

,

□

Lemma 5. For every , the number printed by Flowchart 3 does not exceed the number printed by Flowchart 4.

Proof. Let

. For every system of equations

, if

is a unique solution of

in

, then

solves the system

, where

By this and the inclusion

,

has exactly one solution in

, namely

. □

Theorem 4. For every , Flowcharts 3 and 4 print the same number.

Proof. It follows from Lemmas 4 and 5. □

The following program in MuPAD implements the semi-algorithm shown in Flowchart 4.

input("Input a non-negative integer n",n):

m:=0:

while TRUE do

X:=combinat::cartesianProduct([s $s=0..m] $t=0..n):

Y:=[max(op(X[u])) $u=1..(m+1)^(n+1)]:

for p from 1 to (m+1)^(n+1) do

for q from 1 to (m+1)^(n+1) do

v:=1:

for k from 1 to n+1 do

if 1=X[p][k] and 1<>X[q][k] then v:=0 end_if:

for i from 1 to n+1 do

for j from i to n+1 do

if X[p][i]+X[p][j]=X[p][k] and X[q][i]+X[q][j]<>X[q][k] then v:=0 end_if:

if X[p][i]*X[p][j]=X[p][k] and X[q][i]*X[q][j]<>X[q][k] then v:=0 end_if:

end_for:

end_for:

end_for:

if q<>p and v=1 then Y[p]:=0 end_if:

end_for:

end_for:

print(max(op(Y))):

m:=m+1:

end_while:

References

- C. S. Calude, To halt or not to halt? That is the question, World Scientific, Singapore, 2024.

- D. Cantone, A. Casagrande, F. Fabris, E. Omodeo, The quest for Diophantine finite-fold-ness, Matematiche (Catania) 76 (2021), no. 1, 133–160. [CrossRef]

- D. Cantone, L. Cuzziol, E. G. Omodeo. On Diophantine singlefold specifications. Matematiche (Catania) https://lematematiche.dmi.unict.it/index.php/lematematiche/article/view/2703/1218. 2024, 79, 585–620. [Google Scholar]

- D. Cantone and E. G. Omodeo, “One equation to rule them all”, revisited, Rend. Istit. Mat. Univ. Trieste 53 (2021), Art. No. 28, 32 pp. (electronic). [CrossRef]

- M. Davis, Yu. Matiyasevich, J. Robinson, Hilbert’s tenth problem, Diophantine equations: positive aspects of a negative solution; in: Mathematical developments arising from Hilbert problems (ed. F. E. Browder), Proc. Sympos. Pure Math., vol. 28, Part 2, Amer. Math. Soc., Providence, RI, 1976, 323–378; reprinted in: The collected works of Julia Robinson (ed. S. Feferman), Amer. Math. Soc., Providence, RI, 1996, 269–324. [CrossRef]

- Yu. Matiyasevich, Hilbert’s tenth problem, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1993.

- Yu. Matiyasevich, Hilbert’s tenth problem: what was done and what is to be done, in: Proceedings of the Workshop on Hilbert’s tenth problem: relations with arithmetic and algebraic geometry (Ghent, 1999), Contemp. Math. 270, Amer. Math. Soc., Providence, RI, 2000, 1–47. [CrossRef]

- Yu. Matiyasevich, Towards finite-fold Diophantine representations, J. Math. Sci. (N. Y.) vol. 171, no. 6, 2010, 745–752. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Royer and J. Case, Subrecursive Programming Systems: Complexity and Succinctness, Birkhäuser, Boston, 1994.

- R. I. Soare, Interactive computing and relativized computability, in: B. J. Copeland, C. J. Posy, and O. Shagrir (eds.), Computability: Turing, Gödel, Church and beyond, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2013, 203–260.

- A. Tyszka, A hypothetical upper bound on the heights of the solutions of a Diophantine equation with a finite number of solutions, Open Comput. Sci. 8 (2018), no. 1, 109–114. [CrossRef]

- A. Tyszka, All functions g:N→N which have a single-fold Diophantine representation are dominated by a limit-computable function f:N∖{0}→N which is implemented in MuPAD and whose computability is an open problem, in: Computation, cryptography, and network security (eds. N. J. Daras, M. Th. Rassias), Springer, Cham, 2015, 577–590. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).