Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Historical Evolution of Avogadro’s Number

2.1. Origins: Concepts and Challenges

- Amedeo Avogadro (1811): Proposed that equal volumes of any gas, at equal temperature and pressure, contain equal numbers of molecules—an assertion that paved the way for atomic and molecular quantification, but without specifying a numerical value or mole concept.

- Nineteenth Century Progress: Advances in kinetic theory and gas laws (notably by Loschmidt in 1865) produced the first numerical estimates—originally the number of molecules per cubic centimetre, now called the Loschmidt constant.

- Jean Perrin (Early 1900s): Named the constant in honour of Avogadro and, through Brownian motion studies, provided the first values near those accepted today.

- Mole Concept: Only solidified with Stanislao Cannizzaro’s advocacy at the Karlsruhe Congress (1860), integrating Avogadro’s hypothesis into chemical atomic weights and equations.

2.2. From Experiment to Definition

- Millikan’s Oil Drop: Linked the electron charge with Faraday’s constant, providing an indirect path to .

- Modern SI System: Culminated in the 2019 SI redefinition, which fixes at a stipulated value: . This is now an exact number [1], anchoring the mole and providing the metric for “amount of substance.”

3. Current Scientific Status

3.1. The SI Mole and Avogadro Number

- Definition: One mole contains exactly 6.02214076 × 1023 specified elementary entities.

- Interpretation: This value is not subject to revision by further experiment; improvements now affect implementations, not the SI constant itself.

3.2. Dimensionality and Educational Nuances

- Historically and pedagogically, “atoms per gram” or “atoms per kilogram” have also been used, corresponding to “gram-mole” or “kg-mole.”

- Modern SI disambiguates, but educational material often benefits from clarifying such usage for students and practitioners.

4. Scientific Significance

4.1. Why Avogadro’s Number Matters

- Chemical Quantification: Enables precise mass–molecule conversion, underpins stoichiometry, and defines fundamental units in chemistry and biology.

- Physics and Beyond: Links atomic mass unit to kilogram, allowing direct comparison of micro and macro scales. Without , the “bridge” between atomic mass (u) and macroscopic mass simply does not exist.

- Measurement and Metrology: Permits construction and realization of standards for mass, amount, and associated constants.

4.2. Educational and Conceptual Impact

- Teaching and understanding moles, atomic/molecular scale, and macroscopic phenomena are impossible without grasping Avogadro’s number.

- Clarifies large number concepts and demonstrates the unity of measurement across scales.

5. Computational Determination of Avogadro Number from Nuclear Physics: State-of-the-Art

5.1. Traditional Experimental Approaches

- Electrochemical Methods: Combine electron charge and Faraday constant.

- These have yielded values agreed upon to many significant digits—at or below parts per billion uncertainty.

5.2. Recent Computational Innovations

- Logic: Avogadro’s number emerges as the inverse of the average atomic mass unit as computed from first-principles of nuclear mass and binding energy models.

-

Procedure:

- Compute average nucleon rest energy (mean of neutron and proton rest masses).

- Subtract average nuclear binding energy per nucleon (from models such as the SEMF or SEWMF).

- Add the electron rest mass energy.

- Convert the total energy to mass (via ), defining the unified atomic mass unit (UAMU).

- Take the reciprocal of UAMU (with mass expressed in kg or gram) to yield Avogadro’s number with units “atoms per kg” or “atoms per gram.”

-

Nuclear Mass Formulae Used:

- Strong and Electroweak Mass Formula (SEWMF): A simplified, innovative model emphasizing volume and electroweak contributions with fewer parameters.

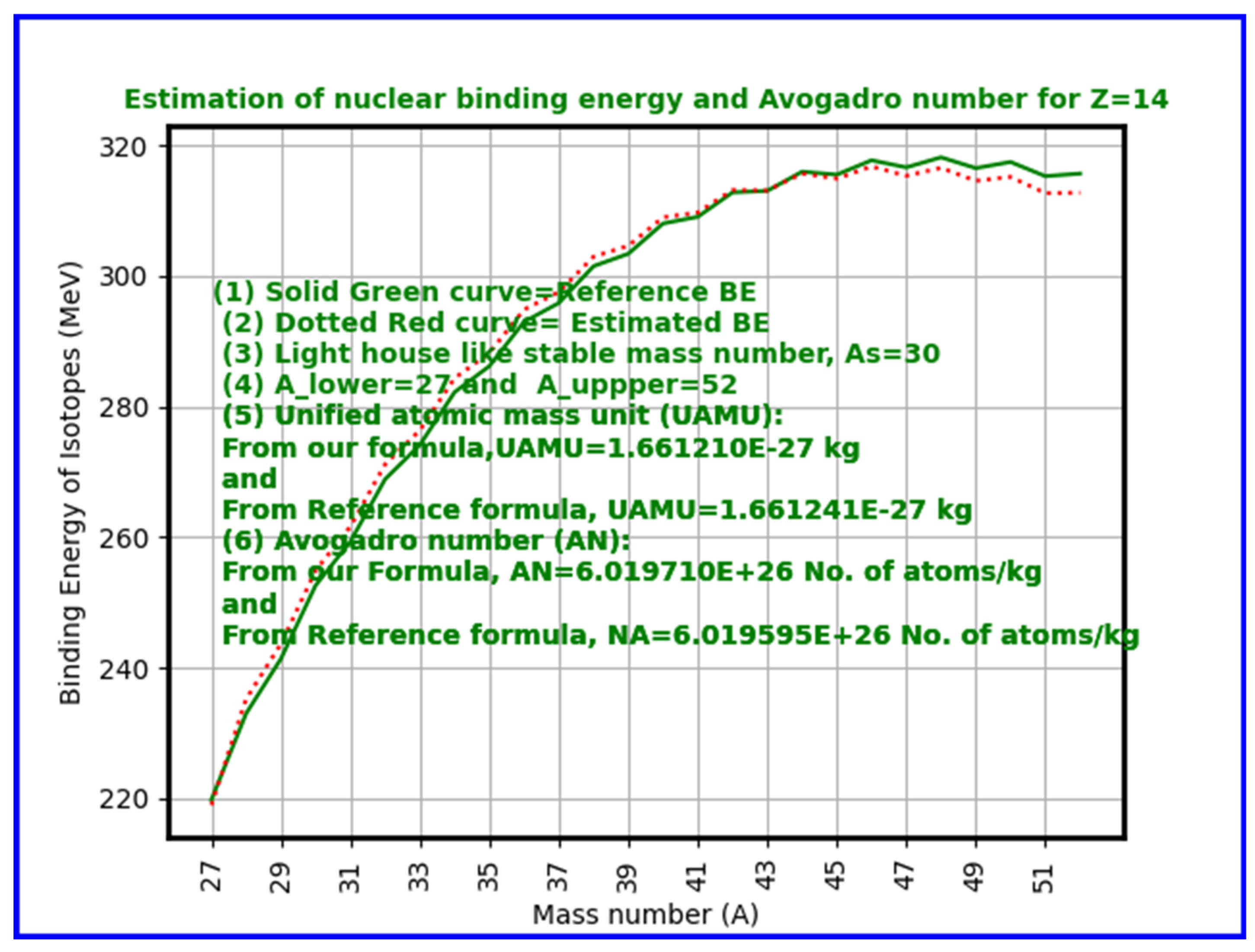

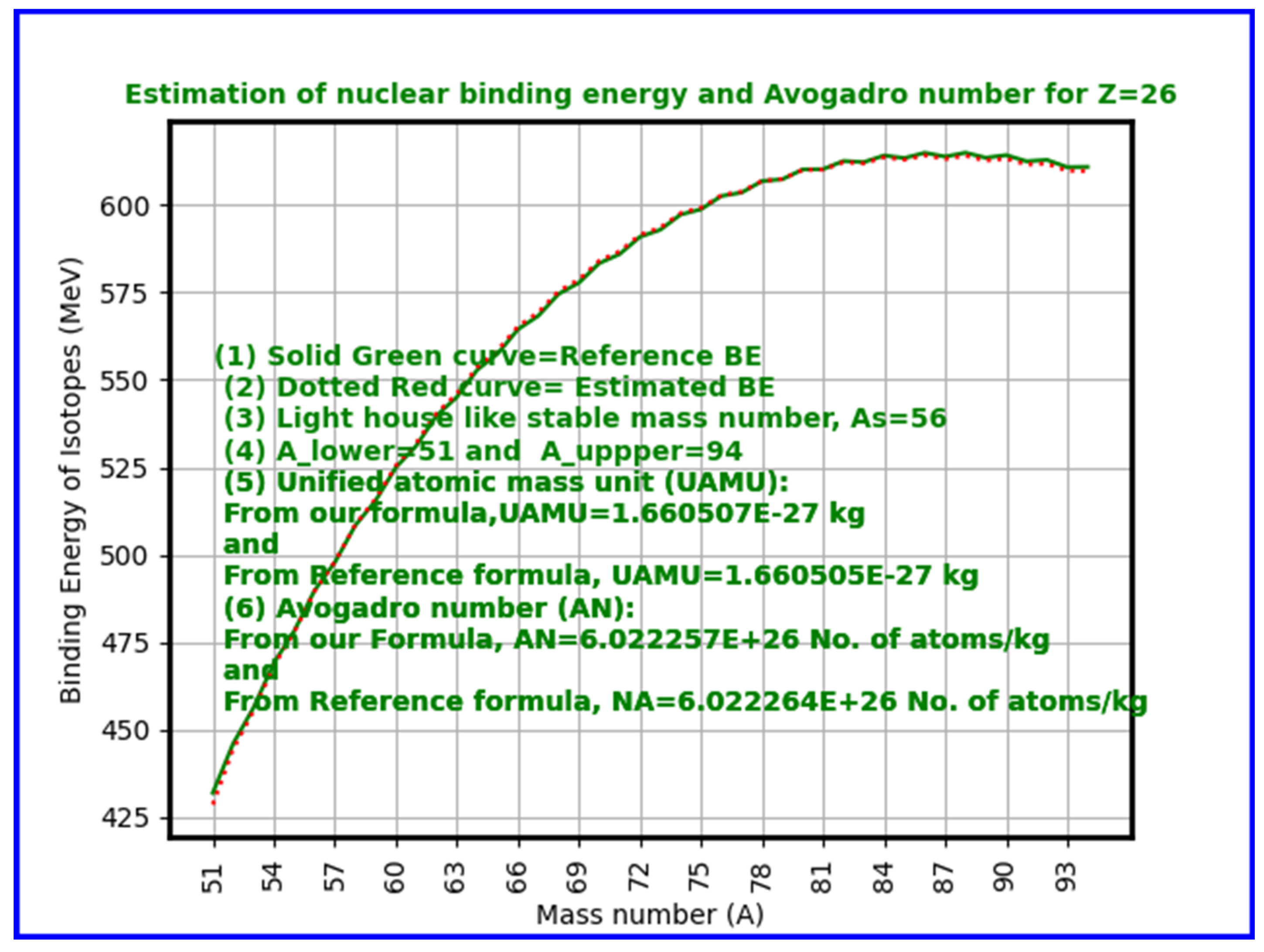

- Key Results: Computed Avogadro values closely match accepted constants, particularly near iron (Z=26), where nuclear binding energy per nucleon peaks.

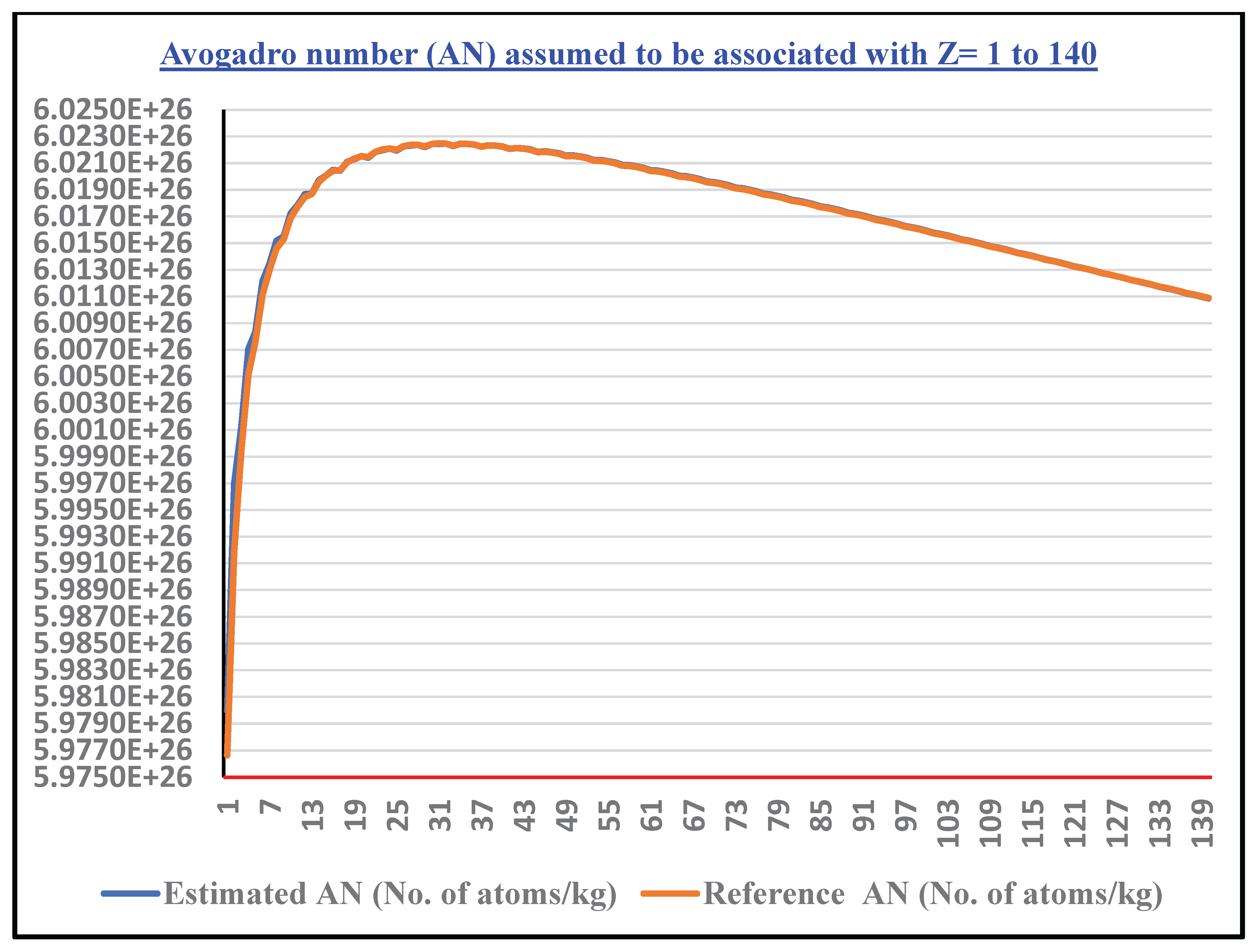

- Averaging across Z = 6 to 118 illustrates robustness and the physical role of nuclear binding saturation in determining Avogadro's number.

6. Special Features of Our Approach

6.1. Nuclear Binding Energy–Centric Physical Framework

6.2. Explicit Inverse Relation Between Avogadro Number and Atomic Mass Unit

6.3. Comprehensive Coverage Across the Nuclear Landscape

6.4. Dual-Formula Testing and Model Flexibility

6.5. Clear Dimensional and Unit Treatment

6.6. Computational Transparency and Pedagogical Potential

6.7. Forward-Looking Integration with Artificial Intelligence

6.8. Unifying Conceptual Framework for the Mole and Avogadro Number

7. Discussion

7.1. Strengths and Advantages

- Conceptual Unification: Offers a physically grounded derivation linking nuclear properties and fundamental constants.

- Transparency: Open code and explicit calculations enable clear verification and educational utility.

- Extendibility: Adaptable to new nuclear data, mass formulas, and AI-enhanced models.

- Pedagogical Impact: Facilitates advanced teaching and exploration of the nuclear origins of macroscopic constants.

7.2. Limitations

- Model-Based Approximations: Relies on semi-empirical formulae, which are approximations especially far from stability.

- Metrological Precision: Does not currently exceed precision achieved by crystallographic and electrochemical methods.

- Dimensional Nuances: Confusion can arise if dimensional and unit conventions are not well explained.

- Data Gaps: Nuclear properties near drip lines and superheavy nuclei remain experimentally and theoretically challenging.

7.3. Future Prospects

- AI and machine learning promise better nuclear mass models, potentially increasing computational accuracy.

- Web-based educational tools could expand accessibility.

- Further exploration of nuclear physics at the limits (superheavy elements, drip lines) can deepen understanding.

7. Mainstream Experimental Determination of Avogadro’s Number

7.1. The Silicon-28 Sphere Method: Measuring Avogadro’s Number by Counting Atoms

- Rationale: Silicon crystals are well-studied and can be prepared almost perfectly. The atomic arrangement within the crystal lattice is regular and highly repeatable, enabling physicists to count the exact number of atoms in a precisely measured volume [4,56].

-

Key Steps:

- Fabrication of Spheres: Scientists manufacture nearly perfect spheres composed of single-crystal silicon highly enriched in the isotope 28Si. The spheres typically weigh about one kilogram and have surface roughness minimized to improve measurement accuracy.

- Measurement of Molar Mass (): Through isotope dilution mass spectrometry, the relative isotopic composition is determined with extreme precision, yielding the molar mass of the silicon sphere.

- Determination of the Crystal Lattice Constant (): Using high-resolution methods such as X-ray interferometry or optical interferometry, the lattice parameter (the length of the cubic unit cell edge) is measured. Silicon’s crystal structure is diamond cubic, which has 8 atoms per unit cell.

- Measurement of the Sphere Volume (): Interferometric techniques also precisely determine the macroscopic volume of the sphere.

- Calculation of Number of Atoms: The total number of atoms in the sphere is given by , where 8 is atoms per unit cell. By dividing the total mass by the molar mass, the number of moles is determined, allowing the calculation of .

- Mathematical Basis: Avogadro’s number links the mole to a direct count of number of atoms via as, , where is the mass of the sphere. Thus,

- Precision and Significance: This method yields the most precise and reproducible value for currently available, reducing uncertainties to parts per billion. This accuracy has been central to the 2019 SI redefinition [1], where the Avogadro number is fixed exactly, decoupling it from experimental uncertainty.

7.2. Complementary and Historical Experimental Techniques

- Millikan Oil-Drop Experiment: Linked the elementary electric charge ee to Faraday’s constant, allowing estimation of .

- Perrin’s Brownian Motion Approach: Analysed fluctuations of suspended particles to estimate the Avogadro number indirectly.

- Gas Density and Kinetic Theory Methodologies: Measured gas properties to calculate numbers of particles per volume.

8. Our Nuclear-Computational Approach with a Unified 6 Term Semi Empirical Mass Formula

8.1. Physical and Computational Framework

- Starting Point: We consider the basic nuclear constituents — protons and neutrons — and their rest energies, combined with nuclear binding energies which represent the energy saving (mass deficit) due to nuclear forces holding the nucleons together.

-

Key Steps in our Calculation:

- Average Nucleon Rest Energy (ANRE): Calculate the mean rest energy of a nucleon, i.e., the average of proton and neutron rest masses multiplied by c2.

- Average Binding Energy per Nucleon (ABEPN): Across the periodic table (Z=1 to 118), and considering isotopes with mass numbers from approximately 2Z to 3.5Z, compute the average nuclear binding energy per nucleon using nuclear mass formulae.

- Average Nuclear Energy Unit (ANEU): Subtract the average binding energy per nucleon from the mean nucleon rest energy to get the effective nuclear mass-energy contribution.

- Add Electron Rest Energy: Incorporate the electron rest mass energy, acknowledging the electrons associated with atoms.

- Calculate Unified Atomic Mass Unit (UAMU): Use the relation to convert the nuclear and electron energy sum to a mass unit.

- Calculate Avogadro Number: Consider the inverse of this mass unit (adjusted for units in grams or kilograms) to estimate the Avogadro number:

-

Nuclear Models Used:

- The classical Semi-Empirical Mass Formula (SEMF), including volume, surface, Coulomb, asymmetry, pairing and other microscopic terms.

- Our unified 6 term SEMF [30] applicable from Z=1 to 140.where,

- Following this unified SEMF applicable from Z= (1 to 140) and considering and , as the lower and upper mass limits, there is a scope for estimating the Avogadro number.

- Considering proton drip lines and neutron drip lines and by fixing the lower and upper mass limits for Z=1 to 140, in a systematic way, for each and every element, corresponding Avogadro number can be estimated by considering average binding energy per nucleon for all of the isotopes under consideration.

- Applying the statistical approach for all the elements, one unique value of can be obtained.

- In a collective approach and by considering the average binding energy effects of the revolving electrons, value of the Avogadro number can be tuned further.

- See Figure 3 for the estimated Avogadro number assumed to be associated with Z=1 to 140.

-

Results and Trends:

- Our calculations show excellent agreement near iron (Z=26), the nucleus with peak binding energy per nucleon and thus greatest stability. The approach naturally explains why Avogadro’s number emerges as it does — as a function of nuclear binding energy saturation effects associated with strong interaction. Starting from Z = (1 to 140), for a total number of 15504 atomic nuclides, estimated

- We recognize that our proposed computational procedure for deriving Avogadro’s number from nuclear binding energies represents a new perspective and methodology in the field. We look forward to the scientific community’s thorough understanding, critical evaluation, and constructive feedback on its validity, applicability, and potential refinements. Such collective scrutiny and collaboration are vital for advancing knowledge and integrating nuclear theory innovations with metrological constants.

8.2. Conceptual and Practical Differences

- By averaging over wide ranges of nuclei—both stable and unstable—it provides a global survey of nuclear structure’s impact on atomic mass units and, consequently, Avogadro’s number.

- The dimensionality of the computed Avogadro number (atoms per gram or kilogram) is made explicit, aiding conceptual clarity around “gram mole” versus “kg mole.”

- We make Python code openly available, underscoring transparency and reproducibility.

9. Reframing the Mole Concept: Distinguishing Between Gram Mole and Kilogram Mole in Understanding Avogadro’s Number

10. ‘The SI Unit Definition of the Mole as Exactly 6.022×10²³ Entities’ Is Problematic

- a)

- Arbitrariness of the Fixed Number: Defining the mole as exactly 6.02214076×10²³ entities is fundamentally arbitrary and lacks grounding in any underlying physical law or natural constant. Unlike fundamental constants such as the speed of light or Planck’s constant, which emerge from universal physical principles, the mole’s fixed numerical value is a human-imposed convention based on historical measurement practices. This arbitrary choice undermines the conceptual purity expected of SI base units.

- b)

- Confusion Between Counting and Mass Units: The mole concept conflates a simple count of entities with mass-related units, leading to persistent confusion. A fixed number of particles per mole ignores the variable isotopic compositions and practical measurement realities of substances in different materials and environments. This rigid linkage oversimplifies complex physical and chemical phenomena and may mislead non-expert users into believing the mole represents a natural constant rather than a pragmatic standard.

- c)

- Mismatch Between Macroscopic and Microscopic Scales: While intended to bridge microscopic atomic scales with macroscopic quantities, fixing the mole at a static large number creates tension when combined with other SI units—particularly mass units defined in kilograms. The factor of 1,000 difference between “per gram” and “per kilogram” counting and the mole’s role as a counting unit is not explicitly resolved, introducing potential inconsistencies, scaling ambiguities, and dimensional confusion in practical use.

- d)

- Pedagogical and Educational Challenges: Emphasizing an exact fixed number for the mole fosters misunderstandings in teaching and learning. Students and practitioners may mistakenly ascribe deeper physical meaning to the number 6.022×10²³, not appreciating its conventional and approximate nature rooted in historical metrology. This hampers scientific literacy and encourages conceptual errors, especially given evolving definitions and measurement techniques.

- e)

- Limitation for Future Scientific Refinement: Fixing the mole’s value rigidly constrains future adjustments and refinements in measurement science and fundamental metrology. Advances in quantum measurement, nuclear physics, or experimental precision may reveal subtleties or require flexibility in the mole’s definition that a fixed integer disallows, potentially impeding scientific progress and adaptation.

- f)

- Disconnect From Natural Variability in Substances: Because isotopic and atomic compositions vary naturally and experimentally, a fixed mole number disregards the heterogeneous nature of real-world samples. This imposes a brittle idealized standard that fails to capture practical chemical variability, limiting the mole’s usefulness in advanced research and precise applications.

11. Conclusion

- Its explicit physical logic, highlighting the inverse relationship between Avogadro’s number and the unified atomic mass unit,

- Its capacity to incorporate and compare multiple nuclear mass models, including both advanced semi-empirical mass formulae and our novel Strong and Electroweak Mass Formula,

- The identification of nuclear binding energy saturation—especially near iron—as a principal factor determining Avogadro’s number’s precise value,

- The clarification of dimensional and unit conventions, elucidating “atoms per gram” versus “atoms per kilogram” and reconciling these with SI mole definitions,

- Its transparent, reproducible computational implementation and pedagogical value,

- The openness to future refinements driven by AI and machine learning methods applied to nuclear mass and binding energy data.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tiesinga, E.; Mohr, P.J.; Newell, D.B.; Taylor, B.N. CODATA recommended values of the fundamental physical constants: 2018. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2021, 93, 025010–033105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siafarikas, M.; Stylos, G.; Chatzimitakos, T.; Georgopoulos, K.; Kosmidis, C.; Kotsis, K.T. Experimental teaching of the Avogadro constant. Phys. Educ. 2023, 58, 065026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordén, B. The Mole, Avogadro’s Number and Albert Einstein. Mol Front J. 5:66-78, 2021.

- Becker, P.; Bettin, H. The Avogadro constant: determining the number of atoms in a single-crystal 28 Si sphere. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2011, 369, 3925–3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K.; Massa, E.; Bettin, H.; Kuramoto, N.; Mana, G. Avogadro constant measurements using enriched28Si monocrystals. Metrologia 2017, 55, L1–L4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, J.; McMorrow, B.; Turban, D.H.P.; Gaunt, A.L.; Spencer, J.S.; Matthews, A.G.D.G.; Obika, A.; Thiry, L.; Fortunato, M.; Pfau, D.; et al. Pushing the frontiers of density functionals by solving the fractional electron problem. Science 2021, 374, 1385–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshavatharam, U.; Lakshminarayana, S. Computing unified atomic mass unit and Avogadro number with various nuclear binding energy formulae coded in Python. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2025, 13, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao ZP, Wang YJ, Lü HL, et al. Machine learning the nuclear mass. Nucl Sci Tech. 32,109, 2021.

- Bethe, H.A. Thomas-Fermi Theory of Nuclei. Phys. Rev. B 1968, 167, 879–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, W.; Swiatecki, W. Nuclear properties according to the Thomas-Fermi model. Nucl. Phys. A 1996, 601, 141–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers W., D. and Swiatecki W. J. Table of nuclear masses according to the 1994 Thomas-Fermi model. United States: N. p., 1994. Web.

- P.R. Chowdhury, C. P.R. Chowdhury, C. Samanta, D.N. Basu, Modified Bethe– Weizsacker mass formula with isotonic shift and new driplines. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 20, 1605–1618, 2005.

- Royer, G. On the coefficients of the liquid drop model mass formulae and nuclear radii. Nucl. Phys. A 2008, 807, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djelloul Benzaid, Salaheddine Bentridi, Abdelkader Kerraci, Naima Amrani. Bethe–Weizsa¨cker semiempirical mass formula coefficients 2019 update based on AME2016.NUCL. SCI. TECH. 31:9, 2020.

- Peng Guo, et. al. (DRHBc Mass Table Collaboration), Nuclear mass table in deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum, II: Even-Z nuclei. Atomic Data and Nuclear Data Tables 158, 101661, 2024.

- Cht. Mavrodiev S, Deliyergiyev M.A. Modification of the nuclear landscape in the inverse problem framework using the generalized Bethe-Weizsäcker mass formula. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 27: 1850015, 2018.

- Ghahramany, N.; Gharaati, S.; Ghanaatian, M. New approach to nuclear binding energy in integrated nuclear model. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 2012, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erler, J.; Birge, N.; Kortelainen, M.; Nazarewicz, W.; Olsen, E.; Perhac, A.M.; Stoitsov, M. The limits of the nuclear landscape. Nature 2012, 486, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshavatharam, U.V.S. and Lakshminarayana S. Understanding the Role of Nuclear Elementary Charge and Its Potential in Estimating Nuclear Binding Energy and Strong Coupling Constant. Hadronic Journal. 48, 207-230, 2025.

- Seshavatharam, U.V. S and Lakshminarayana S. Radius, surface area and volume dependent electroweak term and isospin dependent asymmetry term of the strong and electroweak mass formula. Int. J. Phys. Appl. 2025;7(1):122-134.

- Seshavatharam, U.V. S and Lakshminarayana S. Understanding the Origins of Quark Charges, Quantum of Magnetic Flux, Planck’s Radiation Constant and Celestial Magnetic Moments with the 4G Model of Nuclear Charge. Current Physics. 1, e090524229812, 122-147, 2024.

- Seshavatharam, U.V. S and Lakshminarayana S. Exploring condensed matter physics with refined electroweak term of the strong and electroweak mass formula. World Scientific News.193(2) 105-13, 2024.

- Seshavatharam U., V. S, Gunavardhana Naidu T and Lakshminarayana S. Nuclear evidences for confirming the physical existence of 585 GeV weak fermion and galactic observations of TeV radiation. International Journal of Advanced Astronomy. 13(1):1-17, 2025.

- Seshavatharam U. V., S. , Gunavardhana Naidu T and Lakshminarayana S. 2022. To confirm the existence of heavy weak fermion of rest energy 585 GeV. AIP Conf. Proc. 2451 p 02 0003.

- Seshavatharam U V S and Lakshminarayana, S. 4G model of final unification – A brief report Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2197 p 012029, 2022.

- Seshavatharam U., V. S and Lakshminarayana S., H. K. Cherop and K. M. Khanna, Three Unified Nuclear Binding Energy Formulae. World Scientific News, 163, 30-77, 2022.

- S, S.U.V.; S, L. On the Combined Role of Strong and Electroweak Interactions in Understanding Nuclear Binding Energy Scheme. Mapana J. Sci. 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshavatharam, U.V. S and Lakshminarayana S., Strong and Weak Interactions in Ghahramany’s Integrated Nuclear Binding Energy Formula. World Scientific News, 161, 111-129, 2021.

- Seshavatharam, U. V. S.; Lakshminarayana, S. Revised Electroweak and Asymmetry Terms of the Strong and Electroweak Mass Formula Associated with 4G Model of Final Unification. Preprints 202505 0425, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Seshavatharam, U. V. S. and S. Lakshminarayana. A Unified 6-Term Formula for Nuclear Binding Energy with a Single Set of Energy Coefficients for Z = 1–140. Preprints 2025072397. 2025.

- Unke OT, et al. Machine learning force fields. Chem Rev.121(16),10142-10186, 2021.

- Sarikaya, M. A view about the short histories of the mole and Avogadro’s number. Found. Chem. 2011, 15, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunta, C.J. The Mole and Amount of Substance in Chemistry and Education: Beyond Official Definitions. J. Chem. Educ. 2015, 92, 1593–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIPM, The International System of Units (SI): Ninth Edition, 2019, Section 2.1.1.4 Amount of substance and the mole.

- Roberto Marquardt, Juris Meija, Zoltán Mester, Marcy Towns, Ron Weir, Richard Davis and Jürgen Stohner, Definition of the mole (IUPAC Recommendation 2017), Pure Appl. Chem. 90(1), 175-180, 2018.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).