1. Introduction

Unifying gravity with quantum physics remains one of the central challenges in theoretical physics. While general relativity (GR) passes all tests at macroscopic scales, its merger with quantum theory remains elusive. String theory, though extensively developed, fails to yield a unique low-energy limit, limiting its predictive power [

1,

2,

3]. Loop quantum gravity (LQG) offers a background-independent quantisation of gravity and predicts discrete spectra for geometric operators [

4,

5]. Yet, it struggles to incorporate standard model fields and to recover classical GR in the semiclassical limit. An alternative class of models modifies gravity or introduces new dynamical fields. Scalar-tensor theories, including quintessence, invoke a dynamical scalar field to explain late-time cosmic acceleration [

6,

7], offering an alternative to a cosmological constant and addressing fine-tuning and coincidence problems [

8]. Many modified gravity models, such as

and Horndeski theories, can be recast as scalar-tensor frameworks with non-minimal couplings [

9]. Within quantum gravity, two complementary programs stand out. The asymptotic-safety scenario posits a non-perturbative UV fixed point that makes gravity fundamentally renormalizable [

10,

11]. Renormalisation-group flows drive gravitational couplings to finite values at Planckian scales, while IR fixed points can trigger spontaneous scale symmetry breaking, generating particle masses and dynamically selecting fundamental scales [

12,

13]. A concrete realisation is the cosmon framework, where a time-dependent scalar field remains scale-invariant at both fixed points but breaks symmetry in between accounting for inflation and dark energy without fine-tuning or extra fields [

14,

15]. Second, approaches reinterpret gravity not as a fundamental force but as a macroscopic consequence of underlying thermodynamic or informational structure. Entropic and holographic scenarios derive Newtonian and Einsteinian dynamics from thermodynamic or information-theoretic properties of microscopic degrees of freedom, linking quantum information to geometry [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Recently, a consistent framework coupling classical gravity to quantum matter was proposed, avoiding the need to quantize the metric [

20]. The theory is linear, completely positive, and trace-preserving, reproducing Einstein’s equations in the classical limit. Crucially, fundamental stochasticity in both geometry and matter allows the model to evade no-go theorems while naturally inducing decoherence without invoking measurement postulates. In a related framework, ’t Hooft models systems via discrete ontological states evolving under a unitary matrix, with quantum mechanics emerging as a statistical description and the wave function reflecting epistemic, not ontological, information [

21]. A multiscale framework by Wetterich links particle mass generation and cosmic evolution to a time-varying scalar field, thereby avoiding an initial singularity [

12]. Similarly, Verlinde’s entropic approach reframes gravity as an information-based ordering principle rather than a fundamental force [

16]. While these frameworks offer theoretical insights, none has yet received decisive experimental support.

Rather than relying on a specific microscopic origin such as entropic, holographic, or informational mechanisms [

12,

16,

17,

21] the present model offers a structural unification of these perspectives through a dynamic, energy-based interpretation in which collective gravitational behavior arises organically from recursive multiscale organisation. Crucially, the local internal energy at each scale is defined as a functional of the internal energies of its subsystems, establishing a fully nested energy hierarchy. This recursive structure enables natural coupling across all physical scales and pprovides a mechanism for quantum behavior arising from structurally constrained multiscale interactions governed by cosmological dynamics. The multiscale model thus invites for a reconsideration of foundational assumptions from a dynamic, network-based viewpoint.

The importance of multiscale modeling has long been recognized in other fields of science, notably in chemistry, where the 2013 Nobel Prize was awarded to Martin Karplus, Michael Levitt and Arieh Warshel for pioneering methods that couple quantum and classical regimes to simulate complex systems efficiently [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Building on this principle, the present framework extends the concept of cross-scale coupling beyond molecular systems by establishing recursive multiscale interaction as a structural foundation of physical organisation. This formulation introduces a dynamical paradigm in which Newtonian mechanics arises as a limiting case of recursively structured multiscale couplings, rather than being postulated a priori. Gravitational theory remains operationally valid at macroscopic scales, yet its source terms are recast as effective expressions of deeply nested energy architectures across physical hierarchies.

Modeling decisions, such as which scales to resolve and with what precision, depend on the application. Quantum mechanical, mesoscopic, and classical descriptions may coexist across spatial regions without conceptual conflict, as long as coupling remains consistent. From this broader perspective, chemical multiscale modeling can be viewed as a mature, domain-specific realisation of a more general paradigm: one that integrates macroscopic behavior with microscopic structure through coherent scale-bridging strategies. Building on this idea, we now construct the model from a thermodynamic viewpoint, beginning with a classical analogy and postponing field-theoretic or continuum assumptions.

2. The Recursive Thermodynamic Model

Before introducing the mathematical formulation, we clarify the terminology and conceptual framing used throughout this work. Terms such as “nested structure” and “hierarchy” are employed in a technical sense, grounded in statistical mechanics and multiscale systems theory. By nested structure we refer to a recursive organization in which each subsystem is thermodynamically embedded within, and constrained by, a superordinate system. This top-down influence defines the accessible state space of each level. The term hierarchy, in this context, denotes a functional ordering of energetically interacting systems across multiple scales, where each level contributes to the constraint structure of the next.

The proposed approach is based on two simple postulates:

Assumption 1.

The universe is regarded as an isolated thermodynamic system with no other systems of equal rank. Its total energy equals its internal energy , as kinetic energy is initially set to zero. It remains unchanged in time

This is interpreted as the minimum requirement for the universe.

Assumption 2.

All astronomical systems, macroscopic matter, and composite particles except elementary particles possess a thermodynamic internal energy , in its simplest form defined as

where is the local internal energy and the Hamilton function, with denoting kinetic and potential contributions of the sublevels of U. Each acts as a functional of the family of all recursively nested energy contributions of its subsystems, in the same manner as .

In this formulation, the energies are treated as globally integrated quantities but may be understood as arising from spatial integration over corresponding field variables. A local, differential representation of the first law, as common in continuum thermodynamics, is not used here. When point-like particles are considered, the continuum assumption may be partially dropped, and expressions known from classical mechanics are used in place of volumetric integrals.

Remark 1.

[regarding Assumption A2:] More formally, U is defined as a recursively nested family of energy contributions where each element depends on a local internal energy , itself determined by a subordinate family at the next sublevel

Thereby, a fully nested nonlinear hierarchical structure is established, where denotes the contributions at the first hierarchical sublevel (comprising A subsystems), and , with , refers to the contributions at the sublevel of subsystem α. This can be quantitatively expressed for the first two scales:

This procedure can straightforwardly be generalized to more than two hierarchical scales by considering

In general, each local internal energy is defined analogously in terms of its own subsystems,

thereby enabling unrestricted hierarchical recursion and capturing the multiscale nesting of energy contributions.

The second postulate serves as the foundational hypothesis of this framework, implying that each energy contribution on one level functions as a structurally constrained basis for further decompositions. This establishes nonlinear, recursively coupled interactions across scales—from cosmic to quantum domains.

2.1. Internal Energy of the Universe

Based on the two postulates, the internal energy of the universe

is given depending on multiple scales

abbreviated as

where

is introduced as an energy-operator, with the indices as information about the scales are to be considered. For the universe, taking all scales into account, there is a further definition

2.2. Further Consequences Resulting from the Recursive Model

Each subsystem obeys a local form of the first law

yet remains embedded in a globally coupled thermodynamic structure, as given in Equation (

8). Consequently, no subsystem evolves independently: cosmic-scale variations such as orbital motion, solar output, or gravitational shifts propagate downward and modulate internal energy states across scales.

This has direct thermodynamic implications. According to the Clausius-Duhem inequality of rational thermodynamics [

26]:

the irreversible part of the entropy rate is directly proportional to the rate of internal energy accumulation. Here,

denotes the irreversible part of the entropy rate,

the total entropy rate,

the power density,

the rate of internal energy accumulation,

the heat flux vector, and

the temperature gradient. All quantities are defined per unit volume as common in continuum formulation of balance equations e.g.,

. Obviously, a total equilibrium state becomes thermodynamically inaccessible when internal energy is hierarchically coupled across scales, as postulate 2 implies.

In local formulations, global couplings remain implicitly embedded, much like boundary conditions in classical mechanics encode global constraints into local motion or how path integrals embed the full history of all paths into the current amplitude. Effective parameters such as mass, energy or charge must then absorb multiscale influences by construction. Effective physical parameters such as mass and inertia, respectively, electric charge or energy must then, by construction, absorb and reflect multiscale influences from these nested structures. In particular, experimentally accessible ratios such as the mass-to-charge ratio may serve as sensitive probes for underlying hierarchical effects. The resulting structure acts as an informational mediator across scales, much like spacetime in general relativity encodes and transmits the mutual dependence between energy distributions and geometric curvature

3. Derivation of Newtonian Laws from Recursive Energy Structures

In this framework, Newton’s axioms are obtained as structurally constrained limiting cases. The first law follows by considering a universe containing only a single system with

(point mass). From this, the classical formulation of inertia naturally arises

where

and

are referring to the vectors of velocity and linear momentum. Without the minimum requirement for the universe, the result is not tenable without detailed statements about the work performed on the system and the transferred heat. If we furthermore consider the case of two point-mass systems in the universe from the perspective of classical physics, the well-known relationships emerge:

These relations follow entirely without invoking Newton’s axioms or assuming energy conservation. Instead, they result directly from the minimum condition for the universe (Postulate 1), together with Postulate 2, via:

This holds for all velocities. Here

and

is the Newtonian gravitational force. If the above is interpreted as a derivation by prefixing postulates 1 and 2, then the foundational role typically ascribed to these equations becomes questionable. This demonstrates that Newton’s second and third laws arise as consistency conditions of recursive multiscale couplings, rather than as independent postulates. This equation no longer applies if the system is not a point mass and therefore has a non-zero internal energy.

4. Hierarchical Energy Coupling and Local Observables

4.1. Thermodynamic Fluctuations Across Scales

Illustrating structural interdependence across scales, we consider a molecule on Earth

as subsystem in the multiscale structure of the planet. The first law of thermodynamics in conjunction with Earth’s internal energy, according to postulate 2, provides

The indices M and E indicate the contributions of the molecule and Earth. Obviously, the total energy of the molecule

changes in the same way as the difference

, e.g., when the Earth adopts a different orbit and thereby alters its energy level, or when

and

become identical or both vanish. Due to strong couplings,

and

cannot be treated as independent. Temporarily relaxing this constraint allows hypothetical scenarios involving changes in the velocity of the considered material subsystem. Large masses and high velocities significantly affect this balance, forcing the system to reduce its energy and, in extreme cases, perturbing the orbital dynamics of the carrier system. Such recursive feedback propagates across structurally coupled systems, both laterally and vertically, triggering scale-spanning energy reconfigurations throughout the nested hierarchy. This conceptual exploration underscores that local energy fluctuations cannot remain isolated within the total system and illustrates why the universe, given its vast energy content, large masses, and high velocities on average exhibits remarkable large-scale stability. The macroscopic influence on the microscale becomes particularly visible when

is substituted in Equation (

14) via the local first law, applied to the Earth system

It becomes obvious that the external energies of the Earth as well as the work performed on the Earth and the heat flux across Earth’s surface have an influence on the behavior of all matter and its subsystems.

4.1.1. Brownian Dynamics under the Influence of Cosmological Fluctuations

Moreover, Eqs. (

14) and (

15) suggest that classical Brownian motion may not be purely stochastic in origin, but rather a local thermodynamic response to unresolved energy redistribution across scales. This becomes evident when recast in the form of a Langevin-type equation:

Whereas conventional models like the Langevin approach treat friction and noise as externally imposed stochastic inputs, this framework derives both as intrinsic manifestations of recursive multiscale energy exchange. This perspective generalizes the fluctuation-dissipation relation and reveals how nested thermodynamic structures systematically constrain the accessible dynamics of embedded systems.

4.2. Cosmic Effects on Quantum Systems

For a refined understanding of quantum behaviour we start with examining Earth’s internal energy, which, when resolved to quantum scales following postulate 2, reveals the following structure:

The electron of interest, e.g., in quantum level 1111, is removed from its interacting background and its energy is expressed in isolated form as

Neglecting spin and exchange terms for simplification, the Schroedinger equation follows as

Naturally,

here becomes an operator since the kinetic term in Equation (

19) retains its standard quantum-mechanical form, as it is unaffected by the interpretational shift introduced in this framework. The Schroedinger equation (

19) describes an electron in an effectively isolated state, neglecting explicit multiscale interactions with its cosmological environment. Due to the principled inaccessibility of fully resolving all multiscale interactions in Equation (

17), the wave function

in Equation (

19) must be regarded not as a fundamental ontological entity, but as an effective representation of unresolved recursive multiscale couplings within a hierarchically structured universe. These unresolved couplings are implicitly encoded in the wave function. This perspective interprets quantum behavior as a functional consequence of coarse-grained thermodynamic constraints and boundary conditions, rather than being attributed to intrinsic randomness." From this point of view, the Schrödinger equation thus describes an effective subsystem governed by constraints arising from unresolved energy couplings beyond its descriptive scale. This is in agreement with [

21], where quantum mechanics is interpreted as an effective statistical description, and the wave function encodes epistemic rather than ontological information. In the case of a multi-electron system, explicit interactions are often introduced retrospectively. However, these methods mainly consider interactions within the system and do not take into account the higher astronomical scales that would trivially be included in our multiscale model, see A.

4.3. Zero-Point Energy from Unresolved Recursive Thermodynamic Embedding

The Hamilton function of an ideal/monoatomic gas is given by the following equation

Here,

N is the particle number of the considered system, and

is the Boltzmann constant. If the temperature is set to zero, the Hamilton function vanishes, but the total energy does not disappear as long as the substructures

possess quantum mechanical degrees of freedom

per mode

This equation is embedded within the multiscale model and must also satisfy the equations governing the higher-order systems even if

and

are zero; thus, it is evident that it cannot vanish. Only if there were no further cosmic energy changes, implying an absolutely static universe. Consequently, within this recursive multiscale framework, a non-thermal energy remains that is not attributable to statistical thermodynamics, but reflects unresolved energetic dependencies across hierarchically coupled systems. While this residual energy structurally resembles quantum mechanical zero-point energy, it originates from classical, deterministic nesting rather than quantum uncertainty.

4.4. Remarks on the Uncertainty Principle of Quantum Physics

In this framework, quantum uncertainty is not a manifestation of intrinsic randomness, but arises from scale-dependent limitations in resolving energetic couplings across a recursively nested thermodynamic structure. The Heisenberg principle reflects these structural constraints: any localization perturbs the energetic embedding of a system, forcing a redistribution of unresolved degrees of freedom.

This applies even to structureless particles such as electrons, which—despite nominal isolation—remain thermodynamically coupled to their environment. Attempts to resolve their intrinsic dynamics inevitably inject measurement energy that exceeds the amplitude of cosmological background modulations, thereby altering the system itself.

Zero-point energy is interpreted analogously: it reflects residual, non-thermal contributions from unresolved substructures within the energy hierarchy, as shown in Equation (

21). Even at zero temperature, this energy persists—not due to quantum indeterminacy, but as a thermodynamic consequence of incomplete energetic resolution.

Uncertainty and vacuum energy thus represent functional consequences of unresolved multiscale coupling—grounded in thermodynamic structure, not in quantum postulates.

5. Constraining the Energy-Momentum Tensor through Recursive Thermodynamic Structure

Having established the recursive thermodynamic framework we now turn to its implications for spacetime geometry. Jacobson famously showed that Einstein’s equations can be derived as an equation of state by applying the Clausius relation to local Rindler horizons [

18]. Lemaitre interpreted the cosmological constant as a form of vacuum energy by comparing geometric terms to a perfect-fluid energy-momentum tensor [

27]. This aligns with the view that spacetime geometry encodes thermodynamic constraints imposed by nested energy exchange. While Einstein’s equations relate geometry to energy-momentum, they do not specify the internal origin of

. Rather than postulating fields or fluids, our framework implies in accordance with [

18] that

arises from recursively nested internal energies:

Rather than starting from a predefined spacetime geometry, this framework suggests a reversal of the conventional approach: the energy-momentum tensor

, derived from recursive thermodynamic structure, serves as the primary object. Geometry then arises by solving the Einstein field equations with prescribed

. In this view, spacetime curvature is not fundamental, but constrained by the nested energy architecture of matter.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

Within this thermodynamically consistent, recursive multiscale model, phenomena such as the wave function, zero-point energy, and Brownian motion are understood as effective consequences of constrained energy exchange across hierarchically nested physical systems, rather than as irreducible assumptions of standard theory. The second postulate serves as the foundational hypothesis of this framework, implying that each energy contribution on one level provides a recursively structured foundation for further decomposition. This establishes nonlinear, scale-bridging couplings that span from cosmological to quantum domains. Unlike traditional models that invoke distinct fundamental interactions at each scale, the present framework postulates a unified recursive energy structure, governed by the first law of continuum thermodynamics across scale transitions. Ultimately, the wave function is reinterpreted as an effective descriptor of unresolved multiscale couplings. It no longer describes a static microstate but encodes the system’s current energetic embedding within the multiscale hierarchy. This perspective redefines locality as a scale-relative concept and opens paths to experimental access of global energetic correlations—for instance, via high-precision interferometry sensitive to cosmological background modulations , see B. Within this structure, true equilibrium states are fundamentally inaccessible, as the dynamics of the cosmic scale permanently perturb any lower-scale configuration. Thus, local equilibria can only exist transiently, stabilized by continuous energetic compensation across scales. This suggests that apparent inertial constancy may itself reflect a stabilized dynamic equilibrium, maintained by interscale energetic feedback — a hypothesis that could be tested via long-term drift analysis of precision inertial systems. Consequently, geometry itself may not be a fundamental input but a derived construct determined from the energy-momentum tensor. A full derivation of the metric remains open, but the structure suggests that the geometry is constrained by the recursive multiscale model. The model generalizes and embeds approaches such as Wetterich’s variable-mass cosmology and Verlinde’s entropic gravity into a unified energetic architecture grounded in recursive thermodynamic structure. In Wetterich’s scenario, cosmological redshift arises from increasing particle masses rather than metric expansion. This concept is extended here by permitting energy or mass modulations on one hierarchical level to induce compensatory redistributions on others, consistent with global conservation constraints. These interscale adjustments impose nonlocal consistency conditions, which may manifest as quantum uncertainty, relativistic inertia modulation, or effective gravitational interaction. In particular, we do not assume or invoke any gravitational, cosmological, or superdeterministic mechanisms. The formalism remains fully compatible with conventional quantum theory but explores the possibility of reinterpreting the wavefunction as a statistical projection arising from deeply coupled thermodynamic embedding.

Author Contributions

The author solely conceived, designed, performed, and wrote the study. All aspects of the work were carried out by the author.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Appendix A Structural Resolution and Wavefunction Compensation in Many-Body Approximations

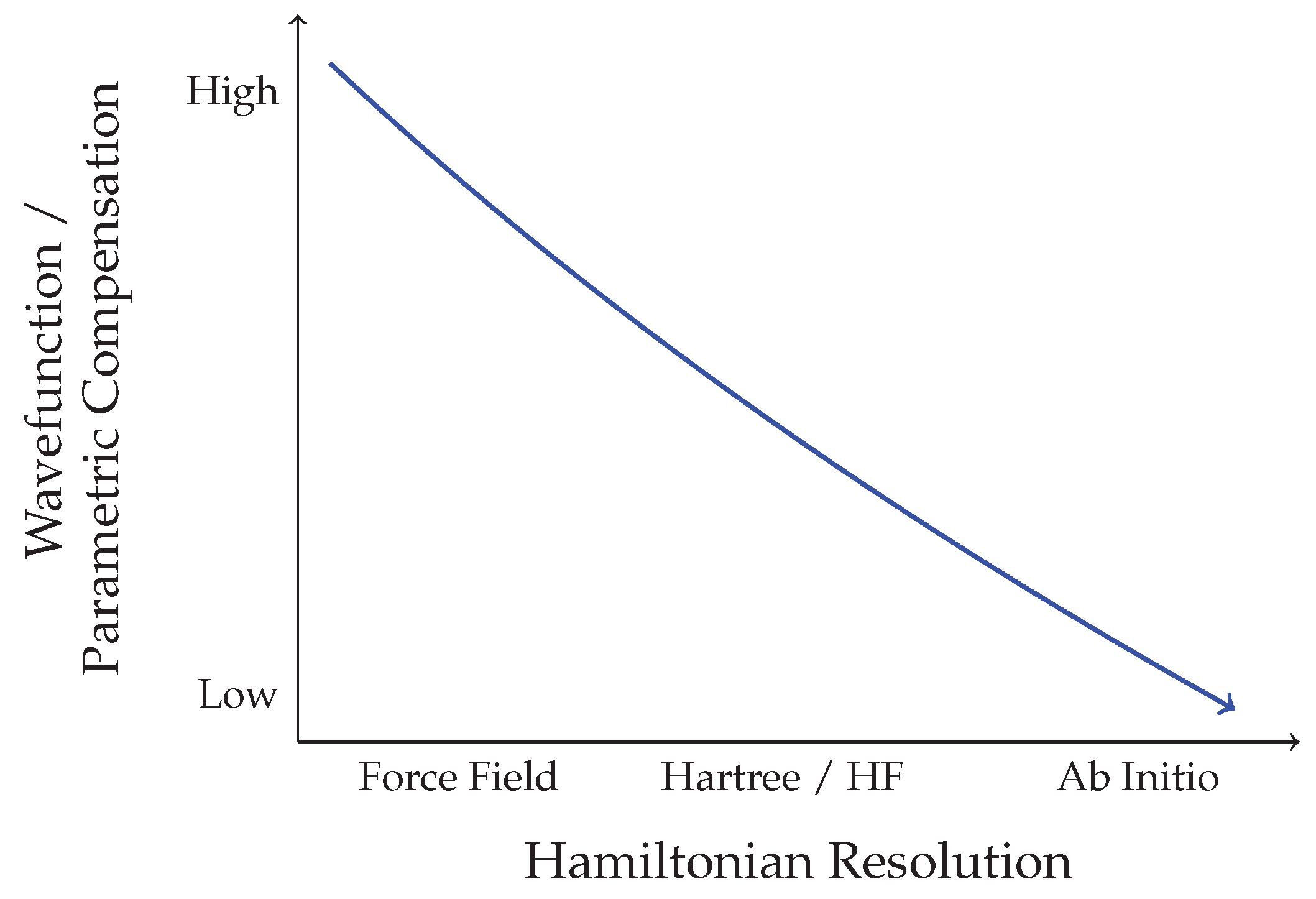

In the theoretical framework adopted here, we systematically decompose the many-body Hamiltonian into hierarchical structural contributions. This allows us to trace which physical interactions are retained or neglected at different levels of approximation and to analyze how missing structure must be compensated elsewhere in the formalism—typically in the expressive capacity of the wavefunction or in the form of parametrized corrections.

For an

A-electron system, we begin with the standard Hamiltonian

explicitly defined as [

28]

These internal terms

can be recursively resolved into two- and three-body contributions:

The structural resolution here shows explicitly which contributions are retained or discarded in different approximation schemes. In common practice, molecular mechanics retains only the simplest local terms within

, such as bonded interactions and fixed potentials. The remaining contributions including

,

, and higher-order terms are not explicitly resolved, but approximated via empirical parametrizations. Hartree and Hartree-Fock methods retain

(Coulomb repulsion), and in the case of HF, also an explicit exchange term, but neglect

and all three-body or higher interactions. Kohn–Sham DFT retains none of these multibody terms structurally; instead, their collective effect is embedded in a one-body exchange-correlation potential. This reveals a general structural principle:

The fewer interaction terms are explicitly resolved in the Hamiltonian, the more compensation is required by the wavefunction, effective potentials, or parametrized models.

Wavefunctions in ab initio approaches must thus develop high internal complexity to recover missing correlations. In DFT,

approximates the effects of electron correlation and polarization not by explicitly resolving multi-particle operators, but by embedding their averaged influence into an effective one-body potential—enabling computational efficiency at the expense of structural transparency.

Operationally, this substitution acts primarily on the -scale: although the Kohn–Sham equations formally treat non-interacting particles on the -scale, the exchange-correlation potential encodes information originating from interactions on the -level via approximate statistical averaging.

In classical force fields, the missing physics must be approximated through fixed parameters obtained from empirical or higher-level fitting. This relation is quantitatively illustrated in

Figure A1.

Remark A1. Structural simplifications at the operator level do not remove physical effects. They are relocated within the formalism. This framework makes such redistribution transparent and allows us to identify which contributions are transferred to the wavefunction, to parametrizations, or to empirical models.

Figure A1.

Inverse relationship between structural resolution of the Hamiltonian and compensatory complexity in the wavefunction or parametrisation.

Figure A1.

Inverse relationship between structural resolution of the Hamiltonian and compensatory complexity in the wavefunction or parametrisation.

Appendix B Experimental Testability

Our model suggests that quantum wavefunctions encode structural information about the recursively organized internal energy hierarchy of a system, which itself may undergo slow modulation through cosmological-scale thermodynamic evolution (e.g., expansion-driven energy redistribution or gravitational embedding). This opens the possibility for long-term or nonlocal experimental signatures beyond standard quantum theory. Such effects may manifest as minute, systematic drifts in spectroscopic transition frequencies, temporally evolving deviations in entanglement correlations across gravitational gradients, or spatially variant signatures in quantum state distributions prepared under nominally identical laboratory conditions. These scenarios imply a testable coupling between cosmic-scale recursive energy structures and local quantum dynamics, potentially mediated by the system’s embedding in a scale-spanning thermodynamic hierarchy.

Furthermore, geochemical barcoding of volcanic samples from the Afar triple junction reveals temporally periodic mantle upwelling pulses with characteristic recurrence intervals of 50-150 kyr [

29]. These pulses, preserved in isotopic and trace-element stratigraphy, provide direct evidence for rhythmic deep-Earth convection. Their consistent frequency ( 10

−5 Hz) and variable expression across rift zones suggest modulation by lithospheric structure and spreading dynamics. Within the proposed model, such pulsations may reflect macroscopic cyclicities in planetary energy distribution, which may modulate deep Earth convection via long-wavelength strain fields or energy density fluctuations consistent with the proposed recursive multiscale coupling framework. The Afar system thus offers a rare empirical proxy for testing large-scale oscillatory behaviour in geodynamic and possibly cosmological-contexts.

We propose that Brownian motion, long seen as the outcome of local stochastic collisions, can be reinterpreted within the framework of our recursive motion equation (

16) as a macroscopic projection of nonlinear multilateral interactions across nested cosmic structures. In this view, deviations from classical Langevin dynamics observable through high-resolution particle tracking are nnot mere stochastic noise, but scale-modulated fluctuations encoding the influence of recursively coupled energy redistribution, reflecting multiscale energy coupling across cosmological embedding Brownian trajectories thus carry structural imprints of the universe’s dynamics, much like the quantum wave function at quantum level. By analysing fluctuation spectra, autocorrelations, and force-response patterns in varied environments, one can extract information about the recursive energy coupling governing motion at mesoscopic scales. This approach opens a new route to probe the thermodynamic structure of the universe experimentally, quantitatively, and from within.

References

- Susskind, L. The anthropic landscape of string theory. In Universe or Multiverse? Carr, B., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2007; pp. 247–266. [Google Scholar]

- Polchinski, J. String Theory; Vol. 1, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Polchinski, J. String Theory; Vol. 2, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rovelli, C. Loop Quantum Gravity. Living Reviews in Relativity 1998, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gielen, S.; Oriti, D. Quantum cosmology from group field theory condensates: A review. Frontiers in Physics 2014, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratra, B.; Peebles, P.J.E. Cosmological consequences of a rolling homogeneous scalar field. Physical Review D 1988, 37, 3406–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujikawa, S. Quintessence: A Review. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2013, 30, 214003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, E.J.; Sami, M.; Tsujikawa, S. Dynamics of dark energy. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2006, 15, 1753–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, T.; Ferreira, P.G.; Padilla, A.; Skordis, C. Modified gravity and cosmology. Physics Reports 2012, 513, 1–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, M. Nonperturbative evolution equation for quantum gravity. Physical Review D 1998, 57, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percacci, R. Asymptotic safety. In Approaches to Quantum Gravity: Toward a New Understanding of Space, Time and Matter; Oriti, D., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2009; pp. 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetterich, C. Probing quintessence with time variation of couplings. Physical Review D 2018, 98, 043501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, A.; Reuter, M. Cosmology of the Planck era from a renormalization group for quantum gravity. Physics Letters B 2002, 527, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetterich, C. Exact evolution equation for the effective potential. Nuclear Physics B 1988, 302, 668–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetterich, C. Variable gravity Universe. Physical Review D 2014, 89, 084007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlinde, E.P. On the origin of gravity and the laws of Newton. Journal of High Energy Physics 2011, 2011, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousso, R. The holographic principle. Reviews of Modern Physics 2002, 74, 825–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, T. Thermodynamics of Spacetime: The Einstein Equation of State. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’t Hooft, G. Dimensional Reduction in Quantum Gravity. arXiv 2009, arXiv:gr-qc/9310026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim, J. A Postquantum Theory of Classical Gravity? Phys. Rev. X 2023, 13, 041040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’t Hooft, G. The cellular automaton interpretation of quantum mechanics. Foundations of Physics 2013, 43, 597–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, M.J.; Bash, P.A.; Karplus, M. A Combined Quantum Mechanical and Molecular Mechanical Potential for Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Journal of Computational Chemistry 1990, 11, 700–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubartsev, A.; Tu, Y.; Laaksonen, A. Hierarchical Multiscale Modelling Scheme from First Principles to Mesoscale. Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience 2009, 6, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karplus, M. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Biomolecules. Accounts of Chemical Research 2002, 35, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, M. Birth and Future of Multiscale Modeling for Macromolecular Systems (Nobel Lecture). Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2014, 53, 10006–10018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basar, Y.; Weichert, D. Nonlinear Continuum Mechanics of Solids; Springer, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, G. Evolution of the Expanding Universe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1934, 20, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feynman, R.P.; Leighton, R.B.; Sands, M.L. The Feynman Lectures on Physics, definitive ed ed.; Pearson/Addison-Wesley, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, E.J.; Rees, R.; Jonathan, P.; et al. Mantle upwelling at Afar triple junction shaped by overriding plate dynamics. Nature Geoscience 2025, 18, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).