Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Caenorhabditis elegans: A Genetically Tractable Organism for Behavioral Studies

2. Machine Learning in C. elegans Behavioral Research

2.1. Machine Learning Approaches for Tracking, Decoding, and Modeling Locomotion in C. elegans

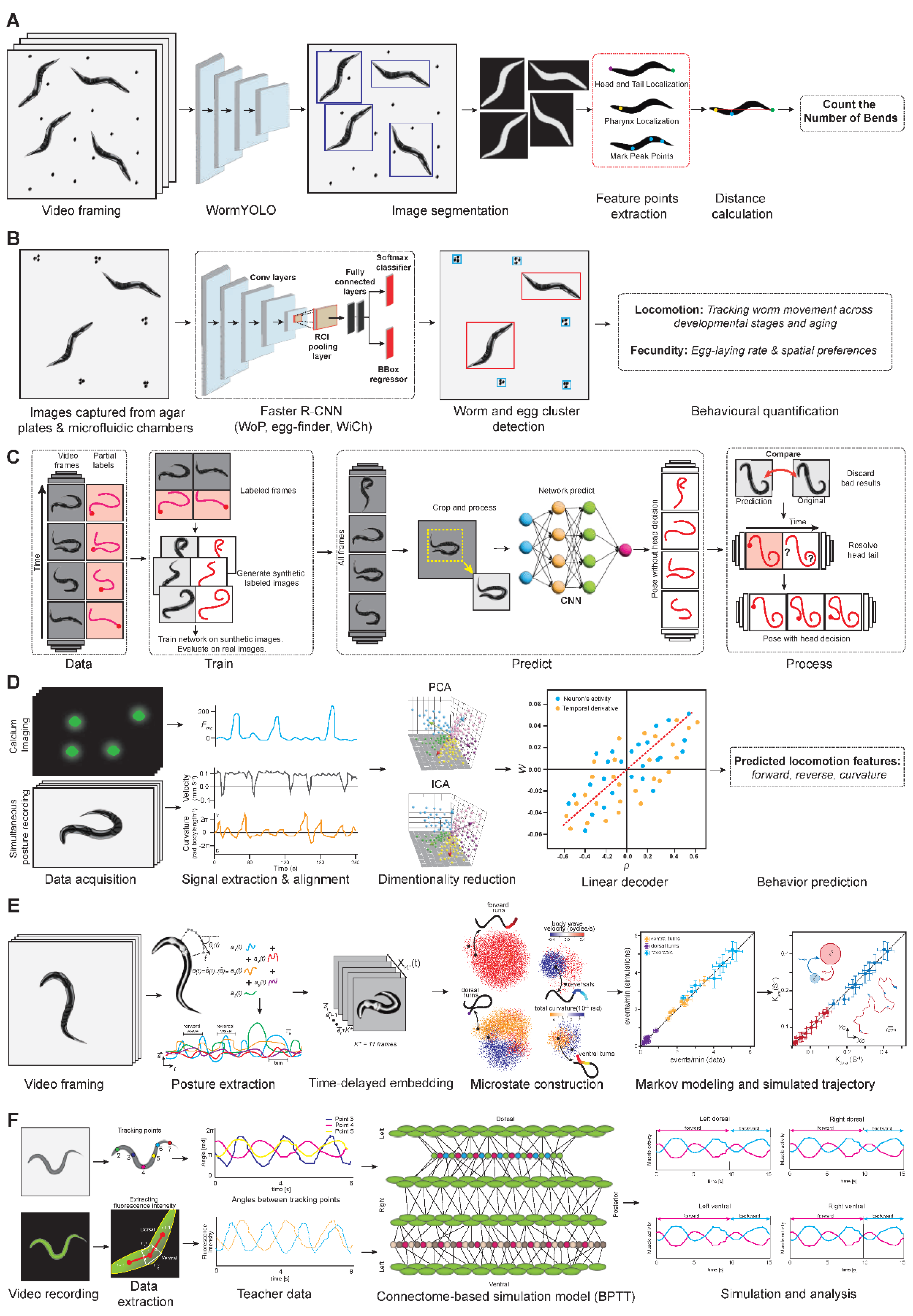

2.1.1. Machine Learning for Segmentation and Detection of Worm Postures

2.1.2. Handcrafted Feature-Based Classification of Behavioral Phenotypes

2.1.3. Deep Learning-Based Representation of Posture and Motion

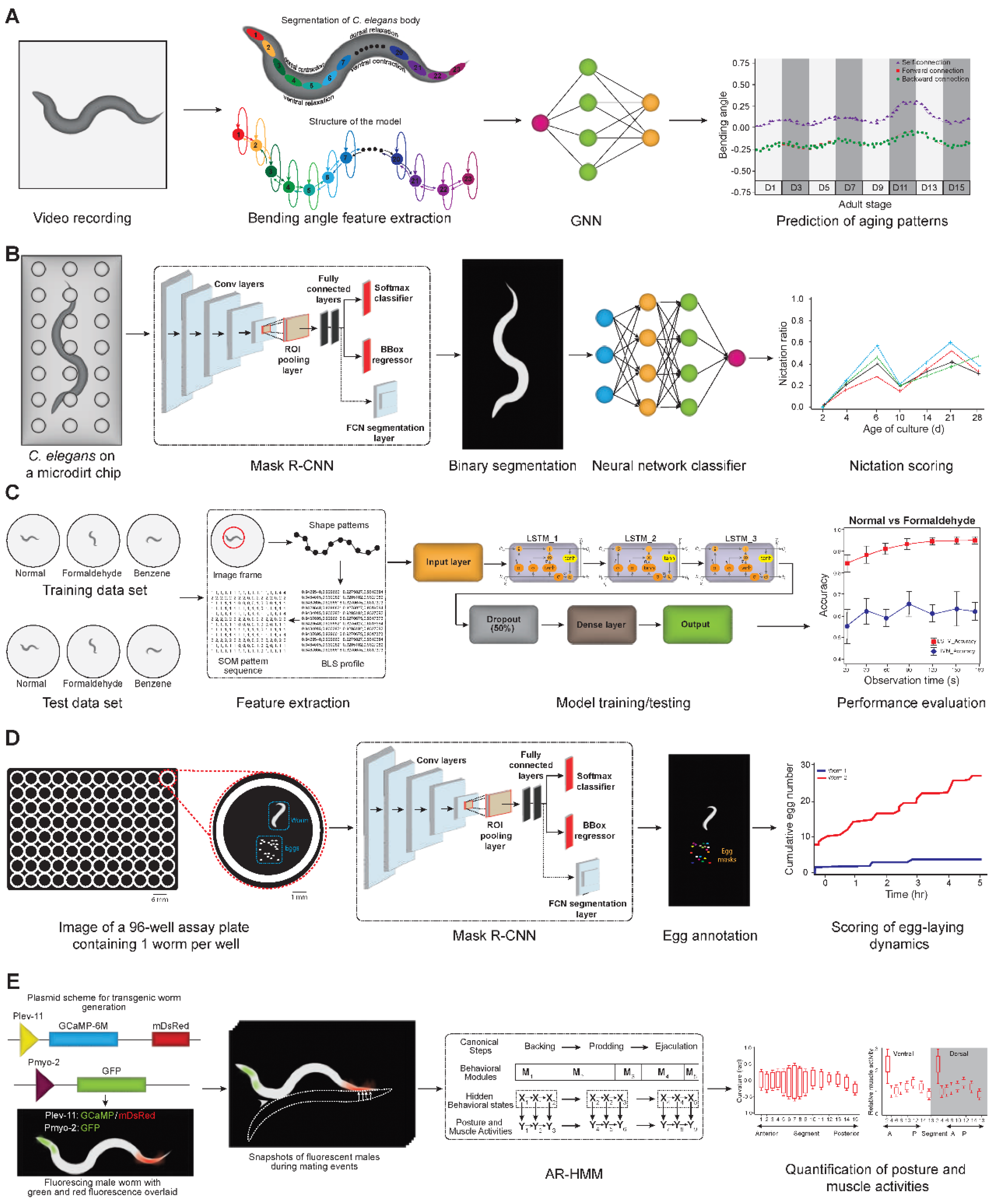

2.1.4. Modeling Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Aging Using Machine Learning

2.2. Machine Learning-Driven Detection and Analysis of Egg-Laying Behavior in C. elegans

2.3. Machine Learning-Based Decoding of Mating Dynamics and Neuromuscular Control

2.4. Machine Learning and Simulation-Based Modeling of Sensory-Guided Navigation

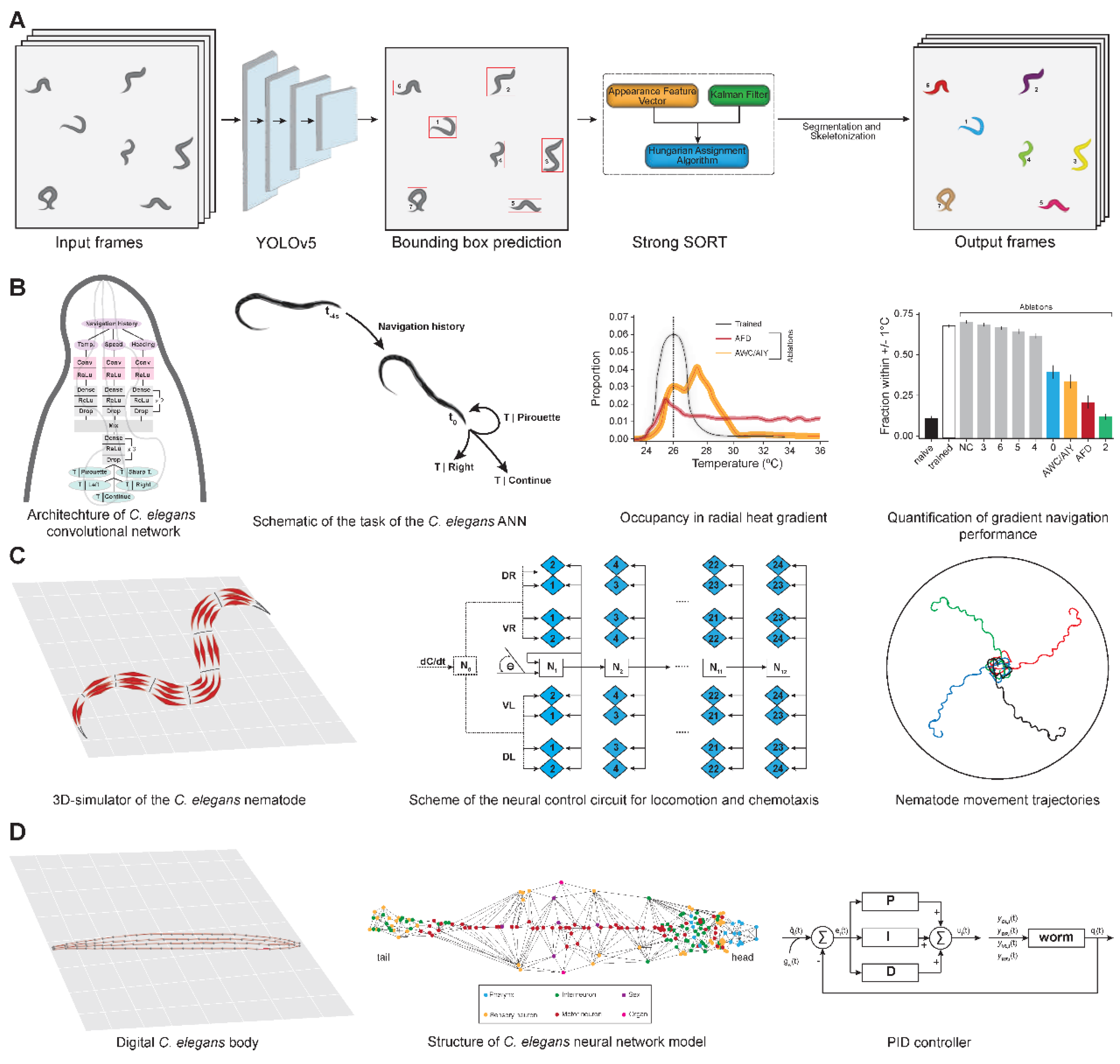

2.4.1. Machine Learning for Multi-Animal Tracking Under Sensory Stimuli

2.4.2. Neural Network-Based Learning of Sensory Representations

2.4.3. Connectome-Based Digital Twins for Navigation Behavior

2.5. Machine Learning and Circuit Modeling Approaches for Mechanosensory Escape Behavior

2.5.1. Linear and Nonlinear Modelling of Stimulus-Response Dynamics

2.5.2. Connectome-Based Recurrent Neural Network Modelling of Escape Behavior

2.6. Machine Learning Models for Social Behavior and Internal State Control

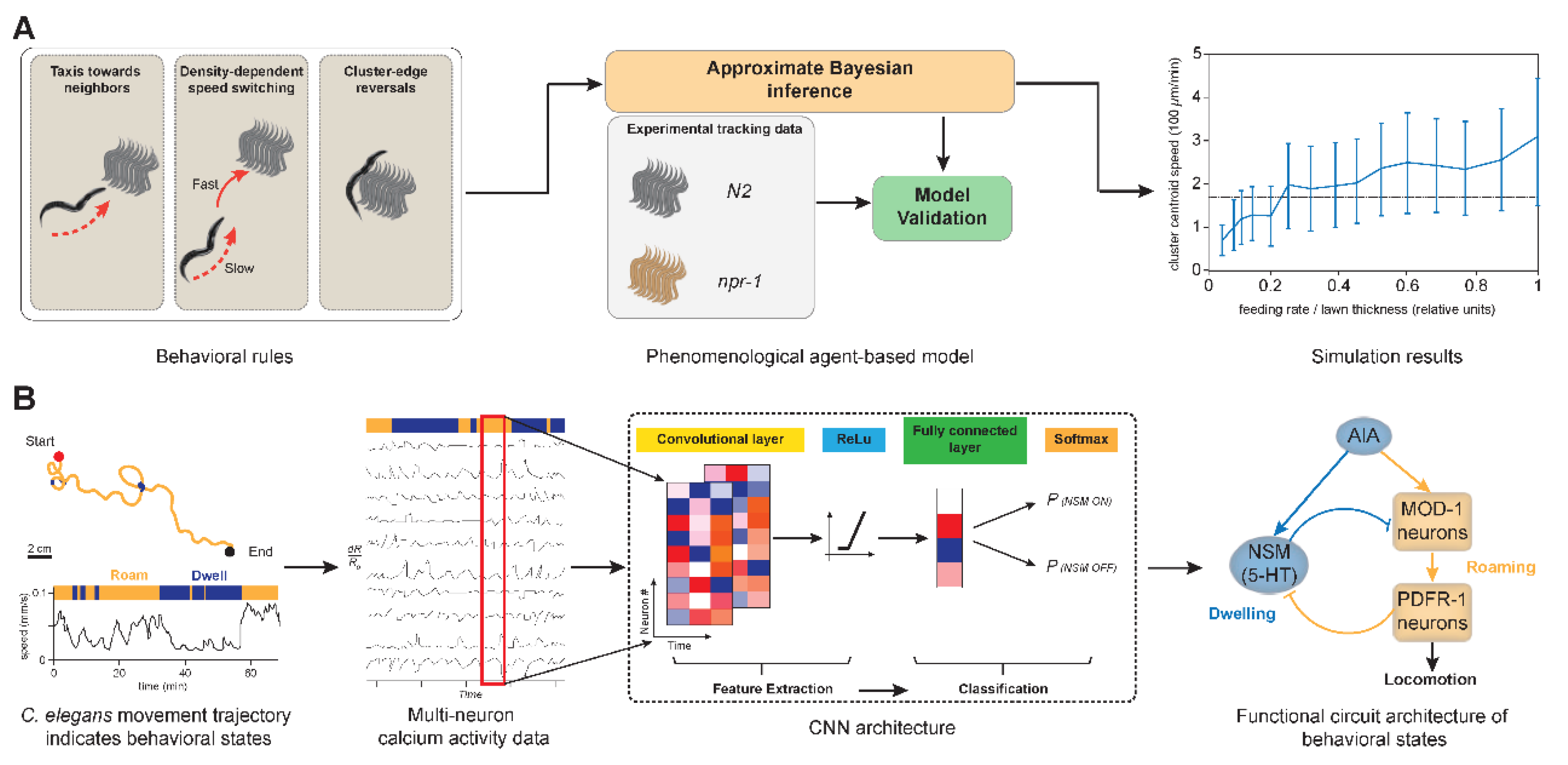

2.6.1. Agent-Based Modelling of Aggregation and Swarming Behavior

2.6.2. Modeling Internal State Transitions Through Neuromodulation Circuits

3. Challenges and Future Directions in Machine Learning for C. elegans Behavioral Analysis

4. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roozen, M. C. & Kas, M. J. H. Assessing genetic conservation of human sociability-linked genes in C. elegans. Behav Genet 55, 141-152 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Ray, A. K. et al. A bioinformatics approach to elucidate conserved genes and pathways in C. elegans as an animal model for cardiovascular research. Sci Rep 14, 7471 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M. et al. An integrative data-driven model simulating C. elegans brain, body and environment interactions. Nat Comput Sci 4, 978-990 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y. et al. Advanced Neural Functional Imaging in C. elegans Using Lab-on-a-Chip Technology. Micromachines (Basel) 15 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Cowen, M. H. et al. Conserved autism-associated genes tune social feeding behavior in C. elegans. Nat Commun 15, 9301 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. et al. Protocol for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing to study spermatogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. STAR Protoc 4, 102720 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X. et al. Locomotion modulates olfactory learning through proprioception in C. elegans. Nat Commun 14, 4534 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, M. M. & Kapahi, P. Pharyngeal Pumping Assay for Quantifying Feeding Behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. Bio Protoc 14, e5073 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Mignerot, L. et al. Natural variation in the Caenorhabditis elegans egg-laying circuit modulates an intergenerational fitness trade-off. Elife 12 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Queiros, L. et al. Overview of Chemotaxis Behavior Assays in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Protoc 1, e120 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, A., McMillen, A., Allen, E., Minervini, C. & Chew, Y. L. Behavioral Tests for Associative Learning in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods Mol Biol 2746, 21-46 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Deshe, N. et al. Inheritance of associative memories and acquired cellular changes in C. elegans. Nat Commun 14, 4232 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Lawler, D. E. et al. Sleep Analysis in Adult C. elegans Reveals State-Dependent Alteration of Neural and Behavioral Responses. J Neurosci 41, 1892-1907 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Jeayeng, S., Thongsroy, J. & Chuaijit, S. Caenorhabditis elegans as a Model to Study Aging and Photoaging. Biomolecules 14 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Fryer, E. et al. A high-throughput behavioral screening platform for measuring chemotaxis by C. elegans. PLoS Biol 22, e3002672 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Kerr, R. A., Roux, A. E., Goudeau, J. & Kenyon, C. The C. elegans Observatory: High-throughput exploration of behavioral aging. Front Aging 3, 932656 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Garvi, A. & Sanchez-Salmeron, A. J. High-throughput behavioral screening in Caenorhabditis elegans using machine learning for drug repurposing. Sci Rep 15, 26140 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Dong, B. & Chen, W. A high precision method of segmenting complex postures in Caenorhabditis elegans and deep phenotyping to analyze lifespan. Sci Rep 15, 8870 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Baek, J. H., Cosman, P., Feng, Z., Silver, J. & Schafer, W. R. Using machine vision to analyze and classify Caenorhabditis elegans behavioral phenotypes quantitatively. J Neurosci Methods 118, 9-21 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, S., Mor, D. E., Kaletsky, R., Keyes, W. & Murphy, C. T. High-throughput behavioral screen in C. elegans reveals Parkinson’s disease drug candidates. Commun Biol 4, 203 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Javer, A., Ripoll-Sanchez, L. & Brown, A. E. X. Powerful and interpretable behavioural features for quantitative phenotyping of Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 373 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Bates, K., Le, K. N. & Lu, H. Deep learning for robust and flexible tracking in behavioral studies for C. elegans. PLoS Comput Biol 18, e1009942 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Hebert, L., Ahamed, T., Costa, A. C., O’Shaughnessy, L. & Stephens, G. J. WormPose: Image synthesis and convolutional networks for pose estimation in C. elegans. PLoS Comput Biol 17, e1008914 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Hallinen, K. M. et al. Decoding locomotion from population neural activity in moving C. elegans. Elife 10 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Costa, A. C., Ahamed, T., Jordan, D. & Stephens, G. J. A Markovian dynamics for Caenorhabditis elegans behavior across scales. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 121, e2318805121 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A. et al. Topological Data Analysis of C. elegans Locomotion and Behavior. Front Artif Intell 4, 668395 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, K., Soh, Z., Suzuki, M., Iino, Y. & Tsuji, T. Forward and backward locomotion patterns in C. elegans generated by a connectome-based model simulation. Sci Rep 11, 13737 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y. et al. A GNN-based model for capturing spatio-temporal changes in locomotion behaviors of aging C. elegans. Comput Biol Med 155, 106694 (2023). [CrossRef]

- McClanahan, P. D., Golinelli, L., Le, T. A. & Temmerman, L. Automated scoring of nematode nictation on a textured background. PLoS One 18, e0289326 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-H., Jeong, I.-S. & Lim, H.-S. A deep learning-based biomonitoring system for detecting water pollution using Caenorhabditis elegans swimming behaviors. Ecological Informatics 80 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Geng, W., Cosman, P., Palm, M. & Schafer, W. R. Caenorhabditis elegans Egg-Laying Detection and Behavior Study Using Image Analysis. EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing 2005 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Ji, H., Chen, D. & Fang-Yen, C. Automated multimodal imaging of Caenorhabditis elegans behavior in multi-well plates. Genetics 228 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y., Macias, L. H. & Garcia, L. R. Unraveling the hierarchical structure of posture and muscle activity changes during mating of Caenorhabditis elegans. PNAS Nexus 3, pgae032 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Itskovits, E., Levine, A., Cohen, E. & Zaslaver, A. A multi-animal tracker for studying complex behaviors. BMC Biol 15, 29 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. C., Khan, K. A. & Sharma, R. Deep-worm-tracker: Deep learning methods for accurate detection and tracking for behavioral studies in C. elegans. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 266 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Haesemeyer, M., Schier, A. F. & Engert, F. Convergent Temperature Representations in Artificial and Biological Neural Networks. Neuron 103, 1123-1134 e1126 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Demin, A. V. & Vityaev, E. E. Learning in a virtual model of the C. elegans nematode for locomotion and chemotaxis. Biologically Inspired Cognitive Architectures 7, 9-14 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Deng, X., Wang, J., Chen, Q. & Tang, Y. Modeling the thermotaxis behavior ofC.elegansbased on the artificial neural network. Bioengineered 7, 253-260 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Yu, Y. & Xue, X. A Connectome-Based Digital Twin Caenorhabditis elegans Capable of Intelligent Sensorimotor Behavior. Mathematics 11 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Porto, D. A., Giblin, J., Zhao, Y. & Lu, H. Reverse-Correlation Analysis of the Mechanosensation Circuit and Behavior in C. elegans Reveals Temporal and Spatial Encoding. Sci Rep 9, 5182 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Daniels, B. C., Ryu, W. S. & Nemenman, I. Automated, predictive, and interpretable inference of Caenorhabditis elegans escape dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 7226-7231 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Lanza, E., Di Angelantonio, S., Gosti, G., Ruocco, G. & Folli, V. A recurrent neural network model of C. elegans responses to aversive stimuli. Neurocomputing 430, 1-13 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ding, S. S., Schumacher, L. J., Javer, A. E., Endres, R. G. & Brown, A. E. Shared behavioral mechanisms underlie C. elegans aggregation and swarming. Elife 8 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Ji, N. et al. A neural circuit for flexible control of persistent behavioral states. Elife 10 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z., Chai, X., Yu, Y., Pang, Y. & Zhang, Z. Improved prototypical networks for few-Shot learning. Pattern Recognition Letters 140, 81-87 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Noroozi, M. & Favaro, P. in Computer Vision – ECCV 2016 Lecture Notes in Computer Science Ch. Chapter 5, 69-84 (2016).

- Toussaint, P. A. et al. Explainable artificial intelligence for omics data: a systematic mapping study. Briefings in Bioinformatics 25 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, P. W. et al. WormBase 2024: status and transitioning to Alliance infrastructure. Genetics 227 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Sarma, G. P. et al. OpenWorm: overview and recent advances in integrative biological simulation of.

- Caenorhabditis elegans. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 373 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S. OVision A raspberry Pi powered portable low cost medical device framework for cancer diagnosis. Sci Rep 15, 7124 (2025). [CrossRef]

| Sl. No | Phenotype | Input data | Machine learning model | Pros | Cons | Reference |

| 1 | Locomotion segmentation | Brightfield video frames | WormYOLO (YOLO + RepLKNet) | High accuracy for coiled/overlapping worms; fast inference | Occasional failures in dense scenes | [18] |

| 2 | Posture classification | Static worm snapshots | CART, CNN (CeSnAP) | Simple and scalable for large-scale screens | Lacks dynamic information | [20] |

| 3 | Posture tracking | Synthetic images, worm skeletons | WormPose (CNN) | Annotation-free; high fidelity in complex poses | Head-tail ambiguity and issues in extreme morphologies | [23] |

| 4 | Locomotion decoding | GCaMP6 calcium imaging | Linear decoder (Ridge regression) | Robust prediction of curvature/velocity | Neuron identity not preserved | [24] |

| 5 | Foraging behavior | Posture time series (eigenworms) | Symbolic Markov model | High realism, interpretable states | Lacks neural network adaptability | [25] |

| 6 | Age-related locomotion pattern | Bending angle time series | GNN | Captures spatio-temporal dynamics | Requires large computation resources | [28] |

| 7 | Nictation behavior | Microdirt arena images | Mask R-CNN + neural net | Outperforms human scorers | Requires high-quality training annotations | [29] |

| 8 | Swimming behavior | Entropy-encoded postural sequences | LSTM | High accuracy, real-time capable | Needs long observation windows | [30] |

| 9 | Egg-laying behavior | Dark-field multiwell images | Mask R-CNN | Multiparametric, longitudinal scoring | Struggles with occlusion | [32] |

| 10 | Mating behavior dynamics | Muscle GCaMP images and posture video | AR-HMM | Hierarchical, interpretable modules | Needs high-fidelity dual-channel imaging | [33] |

| 11 | Chemotaxis simulation | Thermal gradient videos | ANN (supervised + reinforcement learning) | Biological circuit-like representation | Abstracted connectivity | [36] |

| 12 | Neuromuscular control | 3D physics-based worm model | Probabilistic inference ANN | Learns locomotion via reward-based learning | Simplified neural topology | [37] |

| 13 | Digital twin locomotion | Connectome + MuJoCo sim | CENN (BPTT) | Full-body control with sensory feedback | Uses idealized proprioception | [39] |

| 14 | Mechanosensory modeling | Optogenetic time series | ODE inference (Sir Isaac) | Compact, interpretable dynamics | Requires dense time-series data | [41] |

| 15 | Escape response modeling | Stimulus-response pairs | RNN with connectome constraints | Predicts synaptic polarity and output | Relies on curated literature dataset | [42] |

| 16 | Aggregation/swarming | Multi-worm tracking data | Agent-based model | Reproduces emergent group behavior | Requires Bayesian calibration | [43] |

| 17 | State switching (roaming/dwelling) | 10-neuron calcium imaging | CNN + logistic regression | Reveals dual circuit motifs | Context-sensitive modeling needed | [44] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).