Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Synthesis of TiO2/LDHs

2.1.1. Preparation of TiO2 Sol

2.1.2. Synthesis of LDHs Precursors

2.1.3. Synthesis of TiO2/LDHs Nanocomposites

2.2. Characterization

2.3. Photocatalytic Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Material Characterization and Analysis

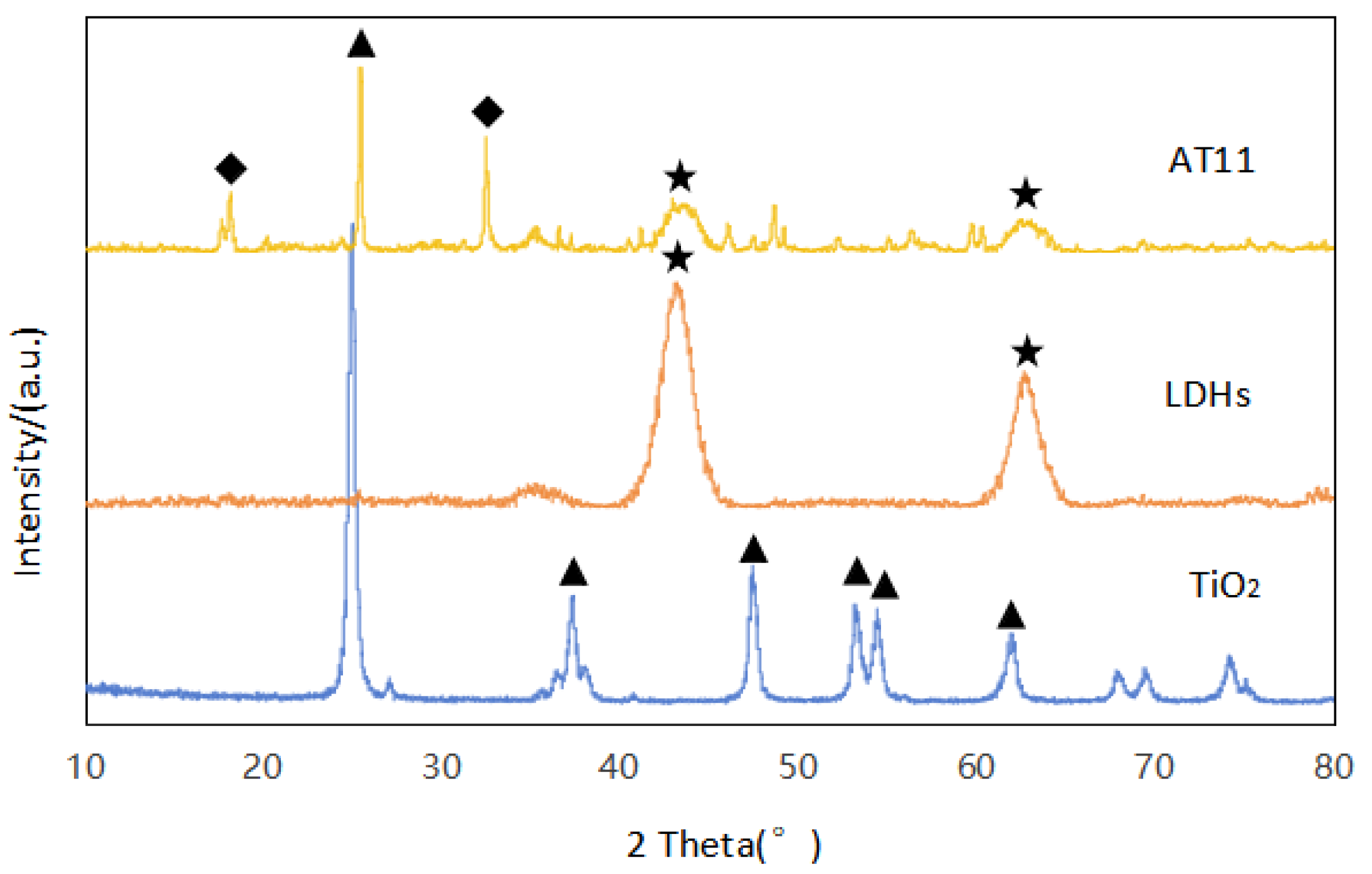

3.1.1. X-Ray Powder Diffraction

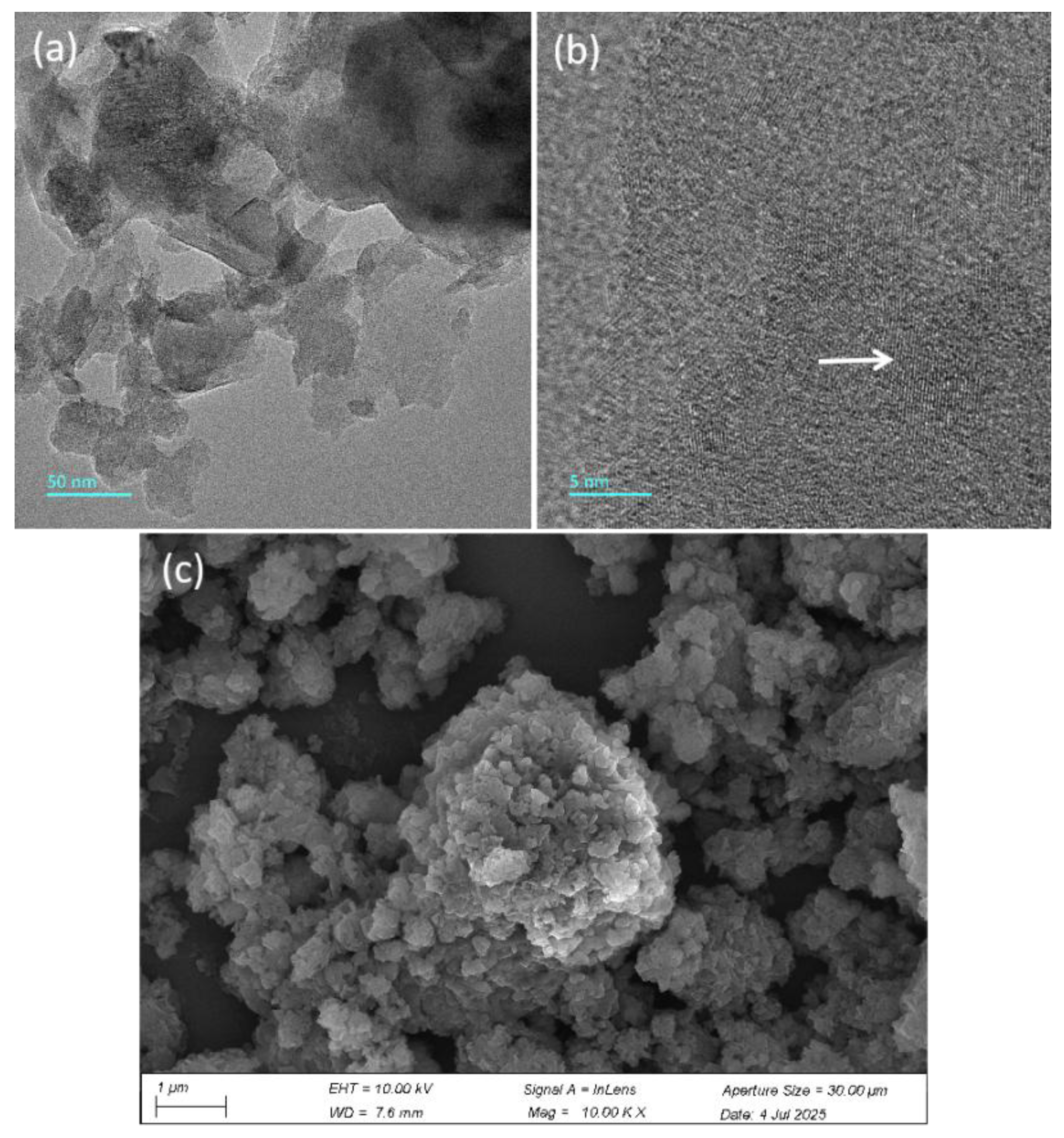

3.1.2. Morphological Analysis of TiO2/LDHs

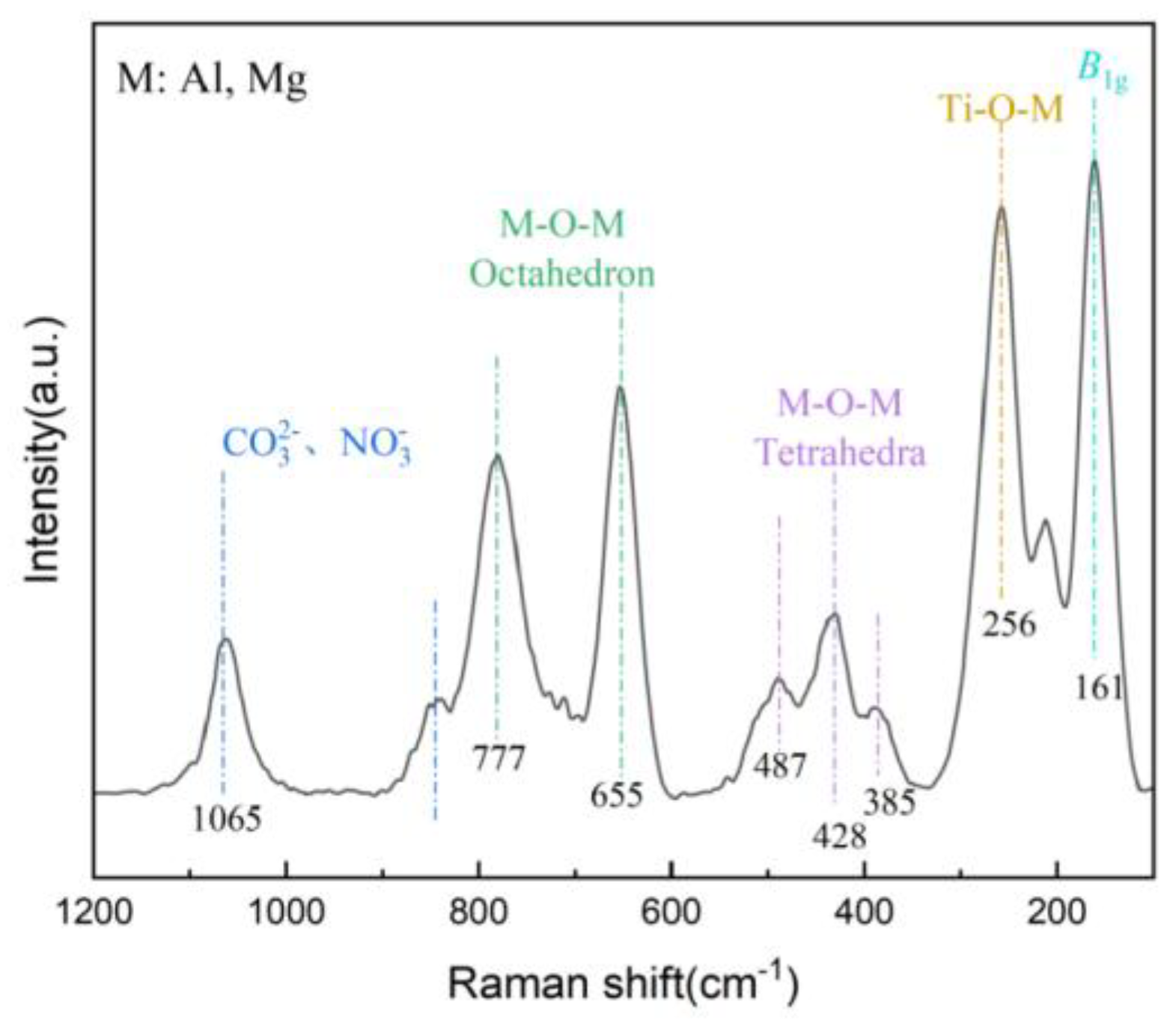

3.1.3. Raman Spectroscopy

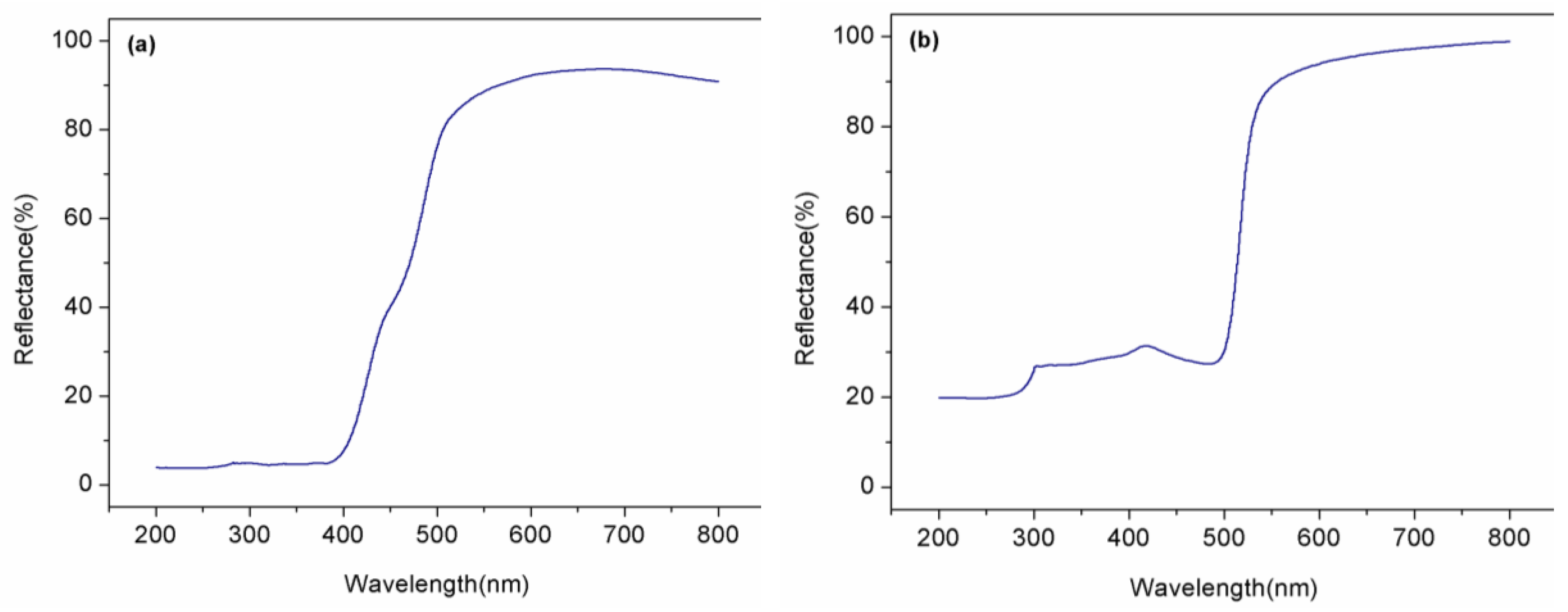

3.1.4. UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy

3.2. Photocatalytic Performance of Photocatalysts

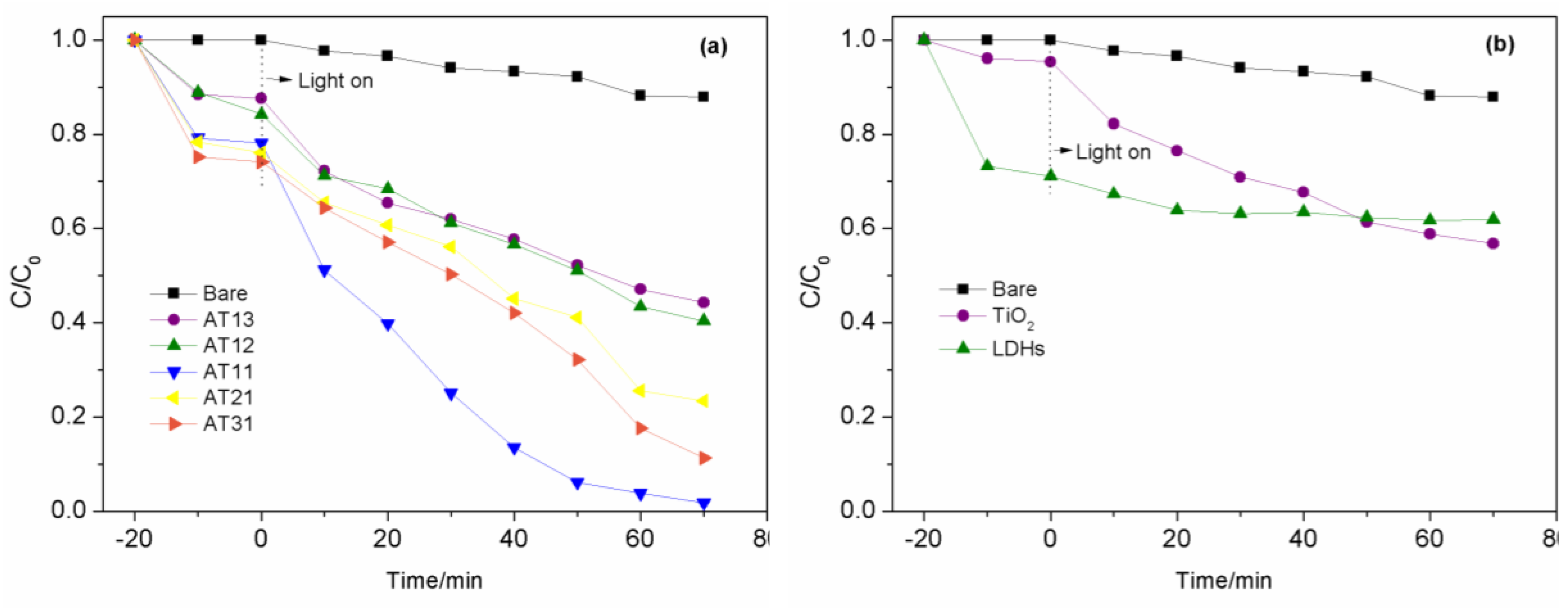

3.2.1. Impact of Diverse Composite Materials on Photocatalytic Performance

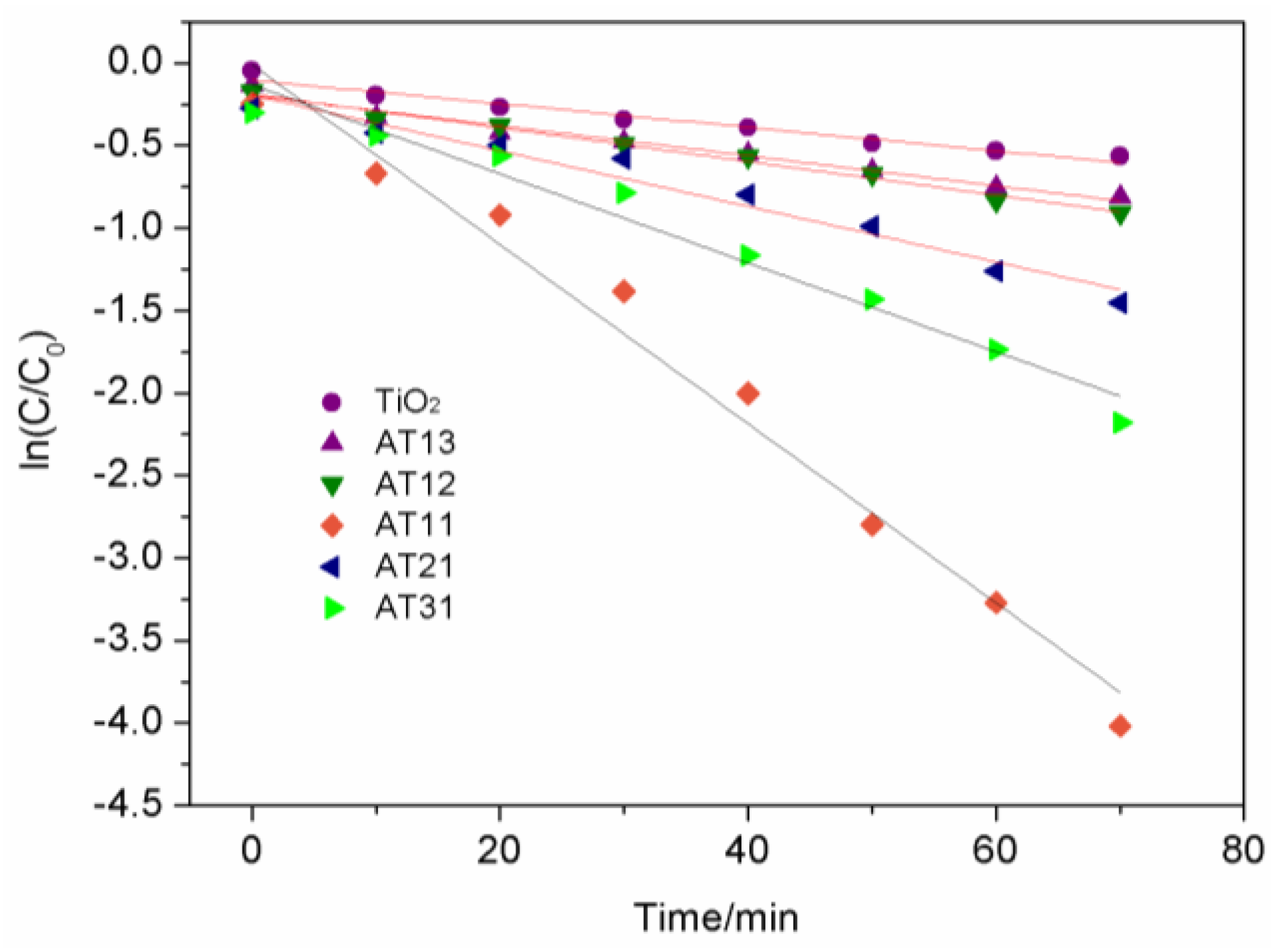

3.2.2. Kinetic Analysis of Photocatalytic Reactions

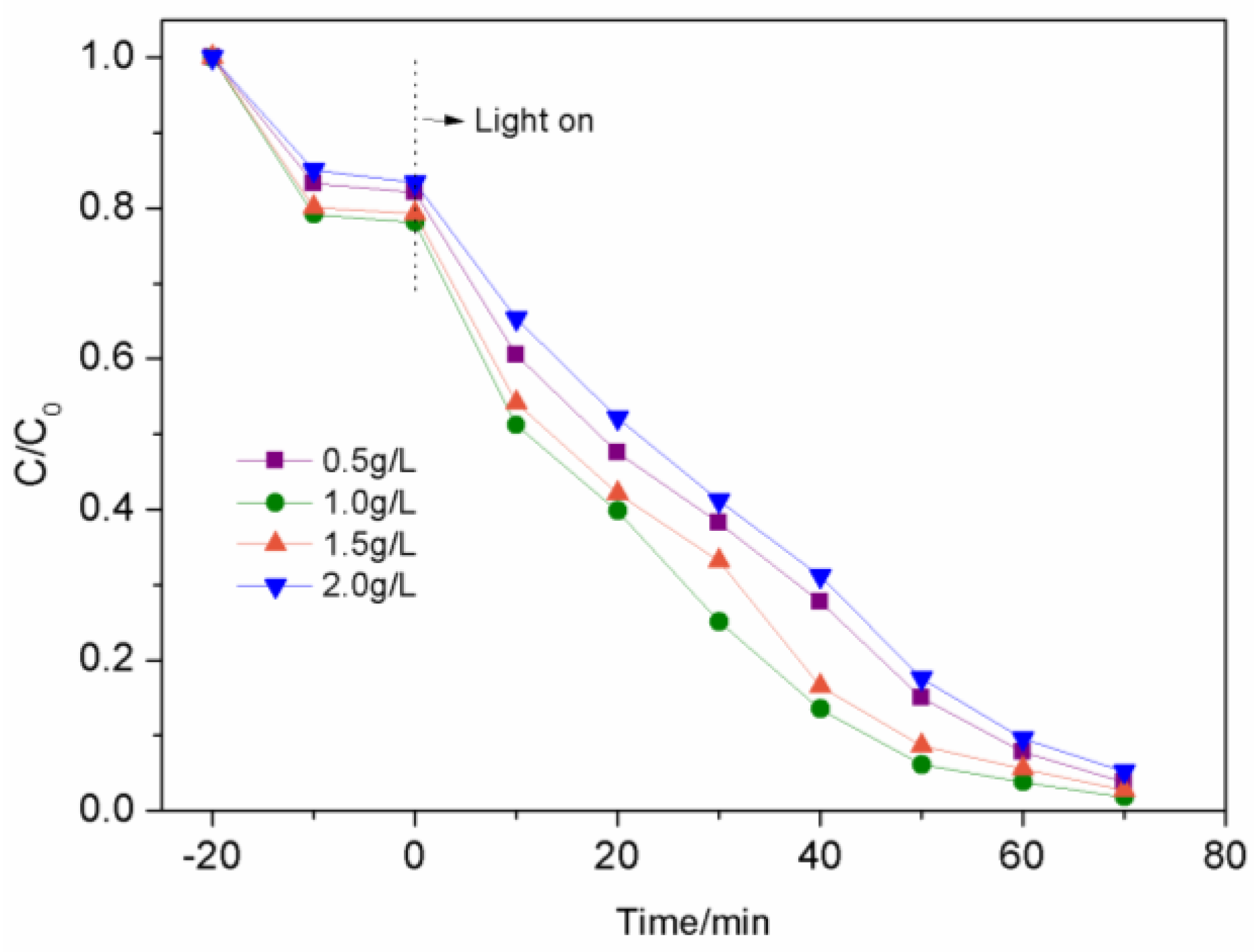

3.2.3. The Impact of Catalyst Concentration on Photocatalytic Performance

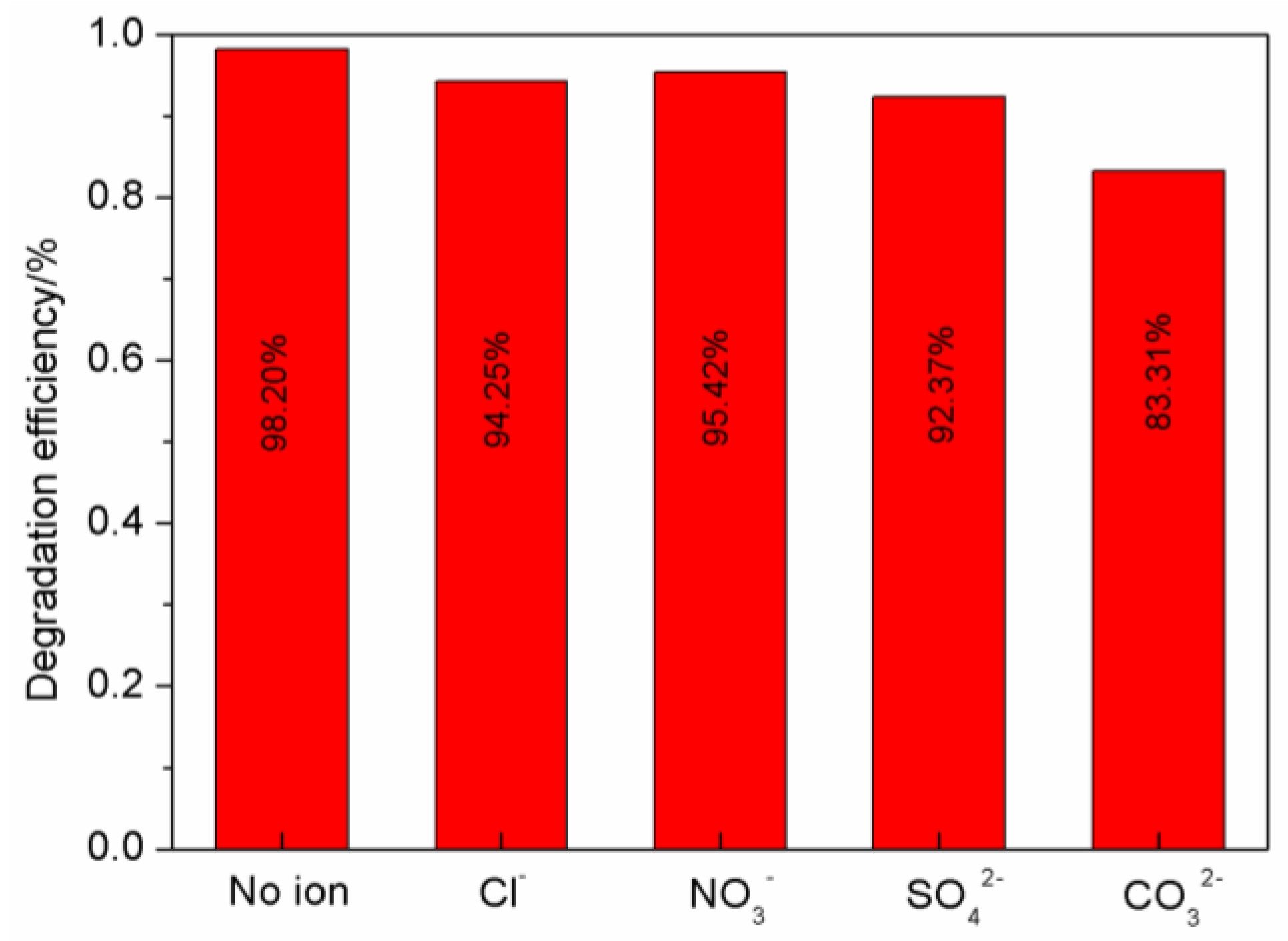

3.2.4. The Impact of Inorganic Anions on Photocatalytic Reactions

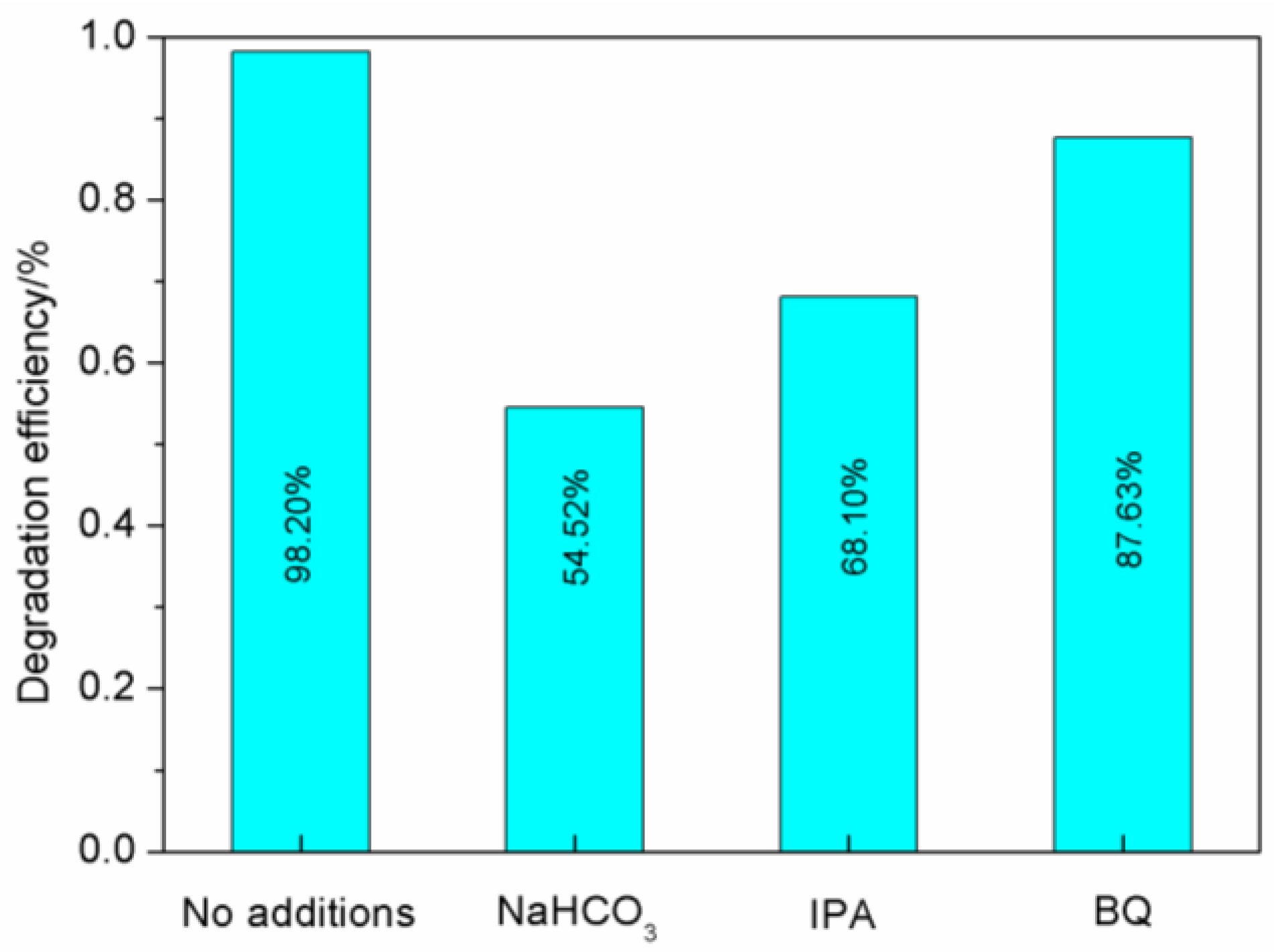

3.2.5. Free Radical Trapping Experiment

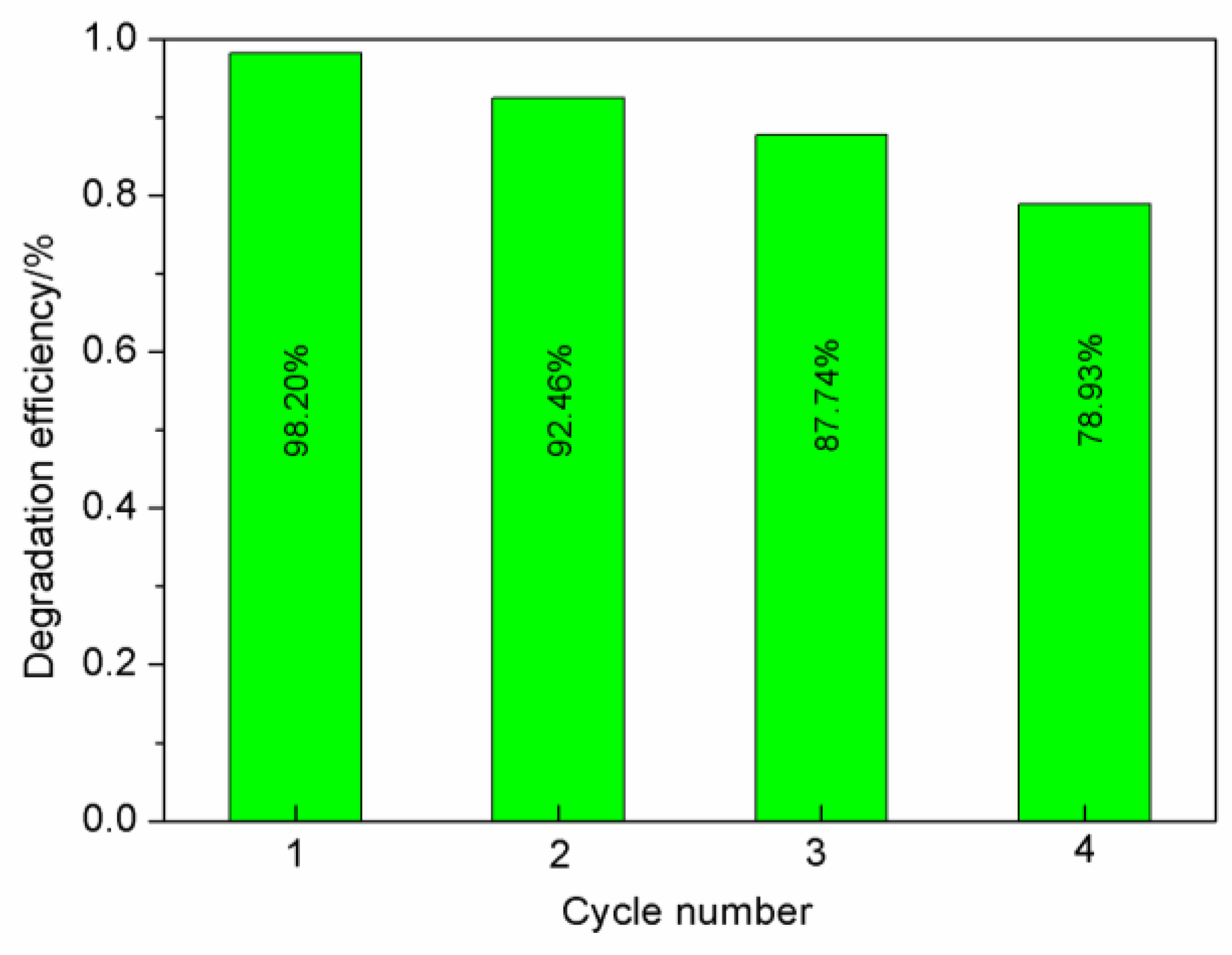

3.2.6. Evaluation of Photocatalytic Stability in Composite Materials

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, J.; Zhou, T.T.; Guo, H.; Ge, C.; Lu, J.J. Application of nano-TiO2@adsorbent composites in the treatment of dye wastewater: A review. Journal Of Engineered Fibers And Fabrics 2025, 20, 15589250251329450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Jiang, G.D.; Hu, M.X.; Huang, J.; Tang, H.Q. Adsorption of Methylene Blue from Aqueous Solution onto Magnetic Fe3O4 / Graphene Oxide Nanoparticles. Environmental Science 2014, 35, 1804–1809. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willison, E.O.C.; Lopes, A.S.C.; Monteiro, W.R.; Filho, G.N.R.; Nobre, F.X.; Luz, P.T.S.; Nascimento, L.A.S.; Costa, C.E.F.; Monteiro, W.F.; Vieira, M.O.; Zamian, J.R. Layered double hydroxides as heterostructure LDH@Bi2WO6 oriented toward visible-light-driven applications: synthesis, characterization, and its photocatalytic properties. Reaction Kinetics, Mechanisms and Catalysis 2020, 131, 505–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadzli, J.; Hamid, K.H.K.; Him, N.R.N.; Puasa, S.W. A critical review on the treatment of reactive dye wastewater. Desalination And Water Treatment 2022, 257, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.J.; Sun, Y.K.; Xing, J.; Meng, A. Fast removal of Methylene Blue by Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles and their cycling property. Journal Of Nanoscience And Nanotechnology 2019, 19, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.Y.; Deng, S.; Han, X.; Wu, S.X.; Bai, Y.Y.; Jiang, Y.H.; Yang, Y. Adsorption Properties and Mechanism of Ciprofloxacin Enhanced by Mn-Doped Biochar. Research of Environmental Sciences 2024, 37, 2526–2536. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Yoo, K.; Kim, M.S.; Han, I.; Lee, M.; Kang, B.R.; Lee, T.K.; Park, J. The capacity of wastewater treatment plants drives bacterial community structure and its assembly. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 14809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assress, H.A.; Selvarajan, R.; Nyoni, H.; Ntushelo, K.; Mamba, B.B.; Msagati, T.A.M. Diversity, co-occurrence and implications of fungal communities in wastewater treatment plants. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 14056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Ghangrekar, M.M. Tungsten oxide as electrocatalyst for improved power generation and wastewater treatment in microbial fuel cell. Environmental Technology 2020, 41, 2546–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, F.X.; Pessoa, W.A.; Ruiz, Y.L.; Bentes, V.L.I.; Silva-Moraes, M.O.; Silva, T.M.C.; Rocco, M.L.M.; Larrudé, D.R.G.; de Matos, J.M.E.; Couceiro, P.R.D. Facile synthesis of nTiO2 phase mixture: characterization and catalytic performance. Materials Research Bulletin 2019, 109, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodzek, M.; Konieczny, K.; Kwiecinska-Mydlak, A. Nano-photocatalysis in water and wastewater treatment. Desalination And Water Treatment 2021, 243, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Chanana, A. TiO2 based nanomaterial: Synthesis, structure, photocatalytic properties, and removal of dyes from wastewater. Korean Journal Of Chemical Engineering 2023, 40, 1822–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.X.; Zhang, Y.H.; Sun, Z.C.; Chang, Y.K. Laboratory study on the evolution of waves parameters due to wave breaking in deep water. Wave Motion 2017, 68, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njema, G.G.; Kibet, J.K. A review of novel materials for nano-photocatalytic and optoelectronic applications: Recent perspectives, water splitting and environmental remediation. Progress in Engineering Science 2024, 1, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.R.; Qiu, F.X.; Xu, W.Z.; Cao, S.S.; Zhu, H.J. Recent progress in enhancing photocatalytic efficiency of TiO2-based materials. Applied Catalysis A-General 2015, 495, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Q.; Hu, Y.H. Color TiO2 Materials as Emerging Catalysts for Visible-NIR Light Photocatalysis, A Review. Catalysis Reviews-Science And Engineering 2023, 66, 1951–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhou, C.Y.; Ma, Z.B.; Yang, X.M. Fundamentals of TiO2 Photocatalysis: Concepts, Mechanisms, and Challenges. Advanced Materials 2019, 31, 1901997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris, S.; de Silva, H.B.; Ranasinghe, K.N.; Bandara, S.V.; Perera, I.R. Recent development and future prospects of TiO2 photocatalysis. Journal Of The Chinese Chemical Society 2021, 68, 738–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, E.; Gomes, J.; Martins, R.C. Semiconductors Application Forms and Doping Benefits to Wastewater Treatment: A Comparison of TiO2, WO3, and g-C3N4. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, Y.; Gareso, P.L.; Tahir, D. Review: influence of synthesis methods and performance of rare earth doped TiO2 photocatalysts in degrading dye effluents. International Journal Of Environmental Science And Technology 2025, 22, 1975–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, L.; Wang, Z.X.; He, J.R. Photocatalytic Oxidation of Printing and Dyeing Wastewater by Foam Ceramics Loaded with Cu and N-TiO2. Catalysis Letters 2024, 154, 3937–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indira, A.C.; Muthaian, J.R.; Pandi, M.; Mohammad, F.; Al-Lohedan, H.A.; Soleiman, A.A. Photocatalytic Efficacy and Degradation Kinetics of Chitosan-Loaded Ce-TiO2 Nanocomposite towards for Rhodamine B Dye. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, V.; Pal, B.; Kaur, S. Photocatalysis of Ag-loaded MgTiO3 for degradation of fuchsin dye and dyes present in textile wastewater under sunlight. Solar Energy 2025, 296, 113587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, M.Q.; Liu, Y.F.; Sun, Y.X.; Zhao, Q.H.; Chen, T.L.; Chen, Y.F.; Wang, S.F. In Situ Construction of Bronze/Anatase TiO2 Homogeneous Heterojunctions and Their Photocatalytic Performances. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.W.; Li, Z.W.; Wen, J.H.; Qiu, P.; Xie, A.J.; Peng, H.P. Review of TiO2-Based Heterojunction Coatings in Photocathodic Protection. Acs Applied Nano Materials 2024, 7, 8464–8488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.Q.; Cao, S.X.; Ye, X.Z.; Ye, J.F. Recent Advances in the Fabrication of All-Solid-State Nanostructured TiO2-Based Z-Scheme Heterojunctions for Environmental Remediation. Journal Of Nanoscience And Nanotechnology 2020, 20, 5861–5873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.H.; Chen, G.Q.; Wang, J.; Li, J.M.; Wang, G.H. Review on S-Scheme Heterojunctions for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Acta Physico-Chimica Sinica 2023, 39, 2212016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Sun, L.; Feng, J.Y.; Gao, S.J.; Zhu, K.; Wu, K.; Guo, R.T. Progress on photocatalytic elimination of CO2 and gaseous pollutants over LDHs-based materials. Journal Of Industrial And Engineering Chemistry 2025, 144, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Z.; Wang, S.; Li, X.L.; Bai, P.; Yan, W.F.; Yu, J.H. Layered Inorganic Cationic Frameworks beyond Layered Double Hydroxides (LDHs): Structures and Applications. European Journal Of Inorganic Chemistry 2020, 43, 4055–4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.F.; Zhang, X.L.; Wang, B.; Niu, J.T.; Yang, Z.X.; Wang, W.C. Fundamental understanding of electrocatalysis over layered double hydroxides from the aspects of crystal and electronic structures. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 1107–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadnadjev-Kostic, M.; Vulic, T.; Lukic, N.; Jokic, A.; Karanovic, D. Photocatalytic Performance of TiO2-ZnAl LDH Based Materials: Kinetics and Neural Networks Approach. Polish Journal Of Environmental Studies 2022, 31, 4117–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, L.; Parida, K. A Review on Recent Progress, Challenges and Perspective of Layered Double Hydroxides as Promising Photocatalysts. Journal Of Materials Chemistry A 2016, 4, 10744–10766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Y.; Gao, X.; Cheng, Y.Q.; Zhang, X.X.; Wang, G.Q.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Su, J.X. TiO2@MgAl-layered double hydroxide with enhanced photocatalytic activity towards degradation of gaseous toluene. Journal Of Photochemistry And Photobiology A-Chemistry 2019, 369, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, M.J.; Shen, Y.; Chan, C.K.; Kim, J.H. Titanium Dioxide-Layered Double Hydroxide Composite Material for Adsorption-Photocatalysis of Water Pollutants. Langmuir 2019, 35, 8699–8708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zheng, K.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, X.; Wu, S.; Su, J. Self-assembly TiO2-RGO/LDHs nanocomposite: Photocatalysis of VOCs degradation in simulation air. Applied Surface Science 2022, 586, 152882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, K.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Cui, J. Construction of two-dimensional nano-composite g-C3N4/LDHs and photocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin. Applied Chemical Industry 2025, 54, 881-886, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seftel, E.M.; Niarchos, M.; Mitropoulos, C.; Mertens, M.; Vansant, E.F.; Cool, P. Photocatalytic removal of phenol and methylene-blue in aqueous media using TiO2@LDH clay nanocomposites. Catalysis Today 2015, 252, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Biswas, K. Synthesis optimization and investigation on electrical properties of Fe2+-doped Mg2TiO4 ceramics for energy storage. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 2020, 31, 12434–12443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Fattah-alhosseini, A.; Kaseem, M. Recent advances in the design and surface modification of titanium-based LDH for photocatalytic applications. Inorganic Chemistry Communications 2023, 153, 110739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljevic, B.; van der Bergh, J.M.; Vucetic, S.; Lazar, D.; Ranogajec, J. Molybdenum doped TiO2 nanocomposite coatings Visible light driven photocatalytic self-cleaning of mineral substrates. Ceramics International 2017, 43, 8214–8221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, A.; Eghbali, P.; Mahdipour, F.; Waclawek, S.; Lin, K.Y.A.; Ghanbari, F. Insights into the synergistic role of photocatalytic activation of peroxymonosulfate by UVA-LED irradiation over CoFe2O4-rGO nanocomposite towards effective Bisphenol A degradation: Performance, mineralization, and activation mechanism. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 453, 139556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Xie, D.; Jiang, L.; Dong, Y.M.; Yuan, Y. Degradation of Organic Dyes by the UCNP/h-BN/TiO2 Ternary Photocatalyst. Acs Omega 2023, 8, 48662–48672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, L.J.; Yang, Y.F.; Chen, L.K.; Liu, X.D.; Chen, H.X.; Yao, Y.Y.; Wang, W.T. Highly efficient removal of organic pollutants via a green catalytic oxidation system based on sodium metaborate and peroxymonosulfate. Chemosphere 2020, 238, 124687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | K/min-1 | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| TiO2 | 0.007 2 | 0.968 7 |

| AT13 | 0.009 1 | 0.976 6 |

| AT12 | 0.010 2 | 0.987 5 |

| AT11 | 0.054 3 | 0.980 5 |

| AT21 | 0.016 8 | 0.965 4 |

| AT31 | 0.027 0 | 0.969 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).