1. Introduction

As the world becomes ever more interconnected, cross-cultural communication is critical. This project, "Real-Time Facial Expression Recognition with Bengali Sound Input: Bridging the Communication Gap," responds to this necessity by combining deep learning-based facial expression recognition (FER) and Bengali audio feedback. This cutting-edge method uses a carefully assembled dataset of varied facial expressions, each accurately annotated with related Bengali audio descriptions, to enhance emotion recognition systems’ accuracy and reliability [

16].

Communication is by its nature verbal and non-verbal, and facial expressions represent one of the most important non-verbal cues for the conveyance of emotions and intentions. Their proper recognition and reciprocation are crucial for enhancing the quality of interaction in such domains as customer care, education, and healthcare. Despite significant advances in FER technologies, it remains challenging to achieve real-time systems with linguistically diverse and accurate feedback [

1]. Existing models fail to work under dynamic real-world scenarios due to lighting variations, occlusions, and individual-to-individual expression variabilities. A significant gap exists, particularly for low-resourced languages like Bengali—spoken by over 230 million people worldwide—which continue to be inadequately supported by current FER systems [

3]. This partial support restricts accessibility and still leads to communication impediments for Bengali speakers.

To break through these challenges, this research seeks to create a real-time FER system with Bengali audio feedback to enable better communication inclusivity and effectiveness for Bengali users. Our approach entails optimizing real-time FER for best accuracy and speed under diverse conditions, incorporating Bengali audio feedback with minimal interruption, and tailoring the system to the Bengali language’s phonetic and syntactic specificities. The system’s practical implications on communication effectiveness and user satisfaction will be rigorously evaluated.

This work explores a range of deep learning models to determine the most appropriate framework for this difficult task. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are used to acquire complex spatial features from facial expression images, detecting subtle muscle movements. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), conversely, are used to represent temporal dynamics of expressions that are vital in understanding emotional nuances. By combining the strengths of CNNs and RNNs in a hybrid architecture, the system aims to achieve more efficient and accurate emotion detection. Furthermore, the impact of data augmentation techniques on model generalization is taken into account, and performance is analyzed on various demographic groups to ensure inclusivity and fairness in the database [

8].

Our system includes a novel ensemble approach combining traditional machine learning and deep learning methods for FER, along with a Bengali text-to-speech module for synthesizing recognized emotions into natural speech. The system is rigorously evaluated through user studies and performance metrics to determine its accuracy, responsiveness, and usability in real-world applications. Results must highlight the dramatic gains of hybrid CNN-RNN architectures in achieving high emotion recognition accuracy, and hence forming the foundation of multimodal deep learning systems that have the potential to transform human-computer interaction [

10].

This technology has the potential to transform communication in the classroom by allowing teachers and students who belong to diverse linguistic backgrounds to communicate in real time, and have equal access to quality education. It is also likely that it will enrich experiences in healthcare, business, and social interactions by providing real-time and culturally relevant emotional context. Its integration into virtual assistants and chatbots may also lead to more natural and emotionally intelligent interactions with users from diverse backgrounds. Last but not least, this research contributes significantly to affective computing and human-computer interaction by demonstrating an end-to-end, Bengali-supported FER system and offering implications for the inclusion of linguistic diversity in future emotion recognition systems.

2. FER Architecture

Facial Expression Recognition (FER) systems in real time are designed to identify and understand human emotions in uncontrolled and dynamic environments. Unlike laboratory-controlled environments, real-world environments—e.g., from vlogs, documentaries, or live video broadcasts—present significant challenges due to lighting changes, head turns, facial occlusions, and complex backgrounds [

4]. A good FER framework must therefore exhibit adaptability, robustness, and multimodal processing to accurately detect spontaneous and subtle emotional expressions.

Bian et al. (2024) introduced an up-to-date hierarchical framework particularly for naturalistic FER comprising five main layers: the Face Detection Layer, Feature Extraction Layer, Emotion Prediction Layer, Contextual Processing Layerand Multimodal Integration Layer [

20].

**Face Detection Layer**: Responsible for face localization and tracking in unconstrained environments. It is designed to be insensitive to problems such as occlusions and changing lighting conditions. • Feature Extraction Layer: It makes use of CNNs in identifying the prominent facial features and action units essential for emotion understanding. • Emotion Prediction Layer: Lastly, the features are categorized into discrete emotional classes with the help of pre-trained deep models.

Contextual Processing Layer: Adds external sources of data—such as body movements, eye gaze, and speech—to enrich and contextualize emotional inference.

Multimodal Integration Layer: Aggregates the output from different modalities (e.g., facial, auditory, and text inputs) through Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) to create an all-encompassing emotional profile [

6].

Furthermore, Management Capabilities and Security Capabilities are embedded in all architectural layers to support real-time processing, ensure data privacy, and ensure system integrity in real-world situations. This multi-layered architecture shows the advancement toward context-aware and secure FER systems effective in naturalistic settings.

3. Related Studies

The new fields of artificial intelligence and machine learning significantly advanced the technology of emotion recognition systems, particularly real-time facial expression recognition (FER). Such systems can help revolutionize human-computer interaction across disciplines and domains like healthcare, education, and customer service by enabling machines to correctly interpret human emotions. However, current real-time FER systems based predominantly on facial expressions are hampered by inherent limitations in terms of occlusions, varying lighting conditions, and variability of expression across people. Most importantly, there is the peculiar absence of linguistic diversity support, including for languages such as Bengali, which is spoken by more than 230 million individuals globally, and which continues to create substantial communication barriers [

3]. Our approach overcomes these shortcomings by combining facial recognition with Bengali voice analysis in a bid to close such communication divides and improve real-time emotional interpretation through more sophisticated analysis of both verbal and non-verbal communications. This research assists in the development of robust, robust emotion recognition systems in many linguistic and cultural contexts.

Literature shows various emotion recognition approaches. Deep learning networks like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can capture spatial features of face expressions, whereas Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) draw out their temporal dynamics; CNN-RNN hybrid models inherit the best from both [

17]. Multimodal approaches, where data from sources such as speech, text, and even biosignals like EEG are integrated, promise higher accuracy and reliability, though in real-time processing and correlation of data, they are challenging [

14,

16]. Recent advances in Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) also promise higher emotion recognition by accessing contextual cues and non-facial body language signals, even in zero-shot learning [

7,

12,

23]. But MLLMs are provable to be challenged by pinpointing the precise details of subtle facial expressions and harmonizing their emotional understanding with that of human perception, as well as generalizability, scalability, and heavy computational expense challenges [

21].

Future research shows limitations in accurate emotion detection with LLMs in fine-grained classification, language-specific nuances, and cultural awareness [

19]. The field is moving towards establishing standard emotion categorization protocols and assessment criteria to enhance scientific rigor [

18] and exploring both unimodal and multimodal approaches for rich emotion analysis in naturalistic conditions [

24]. The eventual future of emotion recognition systems lies in employing different sources of data—facial expressions, speech, text, and biosignals—and rich contextual information with the aid of strong deep learning techniques. By addressing current challenges and moral issues, such as privacy and cultural bias, we can create more accurate, rich, and diverse systems that truly understand human emotions across the board population [

5].

4. Dataset Development

To address the lack of a publicly available multimodal emotion recognition dataset tailored for Bengali, we developed a comprehensive corpus consisting of facial expression images, Bengali emotional text responses, and corresponding speech data. This dataset enables real-time emotion classification and native-language feedback generation, critical for human–AI interaction in Bengali-speaking contexts.

The image dataset comprises 22,525 samples annotated with one of seven emotion classes: angry, disgust, fear, happy, neutral, sad, and surprise. These were sourced from diverse environments to ensure demographic and contextual variation. Corresponding Bengali text and audio feedback were curated or recorded to align with these classes.

All images were resized to pixels and normalized. Augmentation techniques such as rotation, translation, and flipping were applied. Text entries were manually filtered for quality and tokenized using a Bengali vocabulary. Audio data, comprising 4,161 expressive recordings by native speakers, were captured at 16 kHz in emotion-reflective speech.

The dataset supports synchronized input–output mappings (image → emotion → Bengali text/audio), suitable for multimodal deep learning systems.

Table 1 and

Table 2 summarize dataset composition and statistics.

This unified dataset enables joint training of FER models and Bengali-language feedback generators, supporting real-time, culturally aligned emotion-aware systems.

5. Methodology

This section explains the process followed to design the suggested real-time Facial Expression Recognition (FER) system with Bengali feedback generation. The process is organized into five phases: data preprocessing, visual feature extraction, textual and audio generation, multimodal mapping, and integration of the final model.

5.1. A. Data Preprocessing

To maintain data quality and consistency in every modality, the visual, textual, and audio data went through strict preprocessing.

Visual Data: Facial images were resized to

, normalized in the range

, and augmented with rotation, shifting, shearing, zooming, and horizontal flipping. The augmentations serve to enhance model robustness against varying lighting and facial orientations [

13].

Text Data: Bengali text answers were noise feature removed before the preprocessing stage, including emojis and special characters. The text was preprocessed and then tokenized using a 7,000-word vocabulary tokenizer. The sequences were normalized to a fixed length of 20 tokens through padding.

Audio Data: The 16 kHz recorded Bengali speech samples were trimmed and denoised to remove noise and artifacts. The samples were labeled with the corresponding emotion labels, speaker ID, gender, and age group for demographic-aware performance analysis.

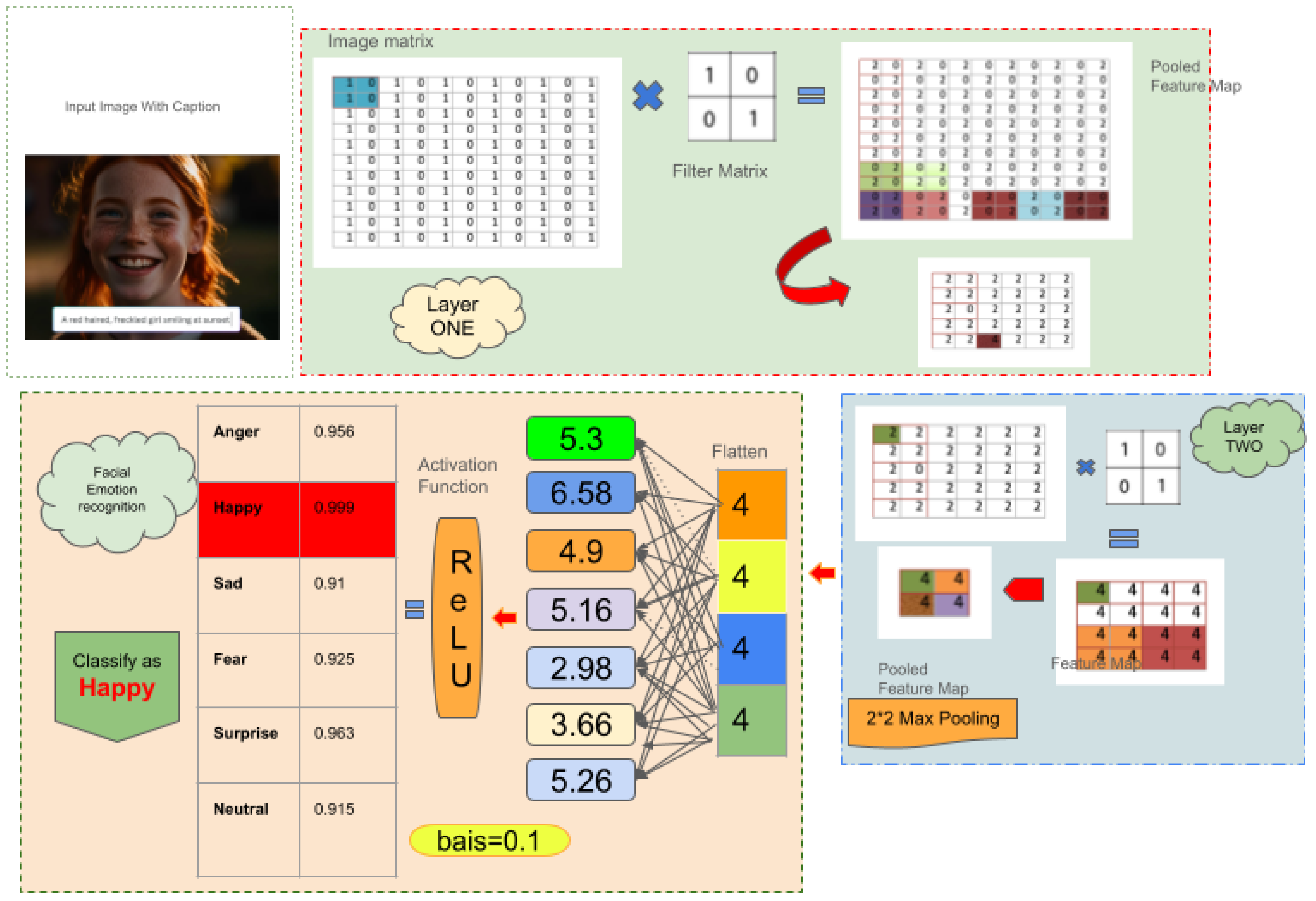

5.2. B. Visual Approach

In order to classify facial expressions from image inputs in a real-time processing model, we designed a light Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model with a focus on both efficiency and accuracy. The model has three convolutional blocks sequentially, each of which is tuned to extract hierarchical spatial features from facial expressions.

Each of the convolutional blocks includes a 2D convolutional layer and then a Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function, which introduces non-linearity into the model. This is followed by a max-pooling layer which reduces spatial dimensions and adds translational invariance. Subsequently, after every pooling step, a dropout layer—typically between 0.2 and 0.5—is added to prevent overfitting by setting a percentage of neurons to zero randomly during training. This regularization makes the network learn more generalized and robust features [

15].

Given an input image , where H, W, and C represent the height, width, and number of channels respectively, the image is first passed through a series of convolutional operations to extract local features.

-

Convolution Operation

For a convolution filter

, the convolution output at location

is computed as:

-

Activation Function (ReLU)

The output of the convolution is passed through a non-linear activation function:

-

Max Pooling

Pooling reduces the spatial dimensions. For a

pooling window:

-

Flattening

After the final convolution and pooling layers, the feature maps are flattened into a 1D vector:

-

Fully Connected Layer with Bias and ReLU

Each neuron computes a weighted sum followed by an activation function:

-

Output Layer with Softmax

To produce probabilities for each emotion class:

where

K is the number of emotion categories (e.g., Happy, Sad, Angry, etc.)

-

Classification

The predicted emotion is the class with the highest probability:

These convolutional blocks are followed by flattening the multi-dimensional feature maps to a one-dimensional vector. The flattened output is fed through a series of fully connected dense layers, each with ReLU activations, to learn complex, high-level representations from the extracted features. The output layer is a softmax classifier that produces a probability distribution over the seven discrete emotion classes: angry, disgust, fear, happy, neutral, sad, and surprise. The model is trained using categorical cross-entropy loss, a default choice for multi-class classification problems, and optimized by the Adam optimizer, which has adaptive learning rate schedules, allowing for efficient convergence[

22]. The lightweight architecture ensures feasibility for real-world applications requiring low-latency inference, e.g., assistive interfaces or affect-aware tutoring systems.

Figure 1.

Architectural overview of the proposed lightweight Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for facial expression classification.

Figure 1.

Architectural overview of the proposed lightweight Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for facial expression classification.

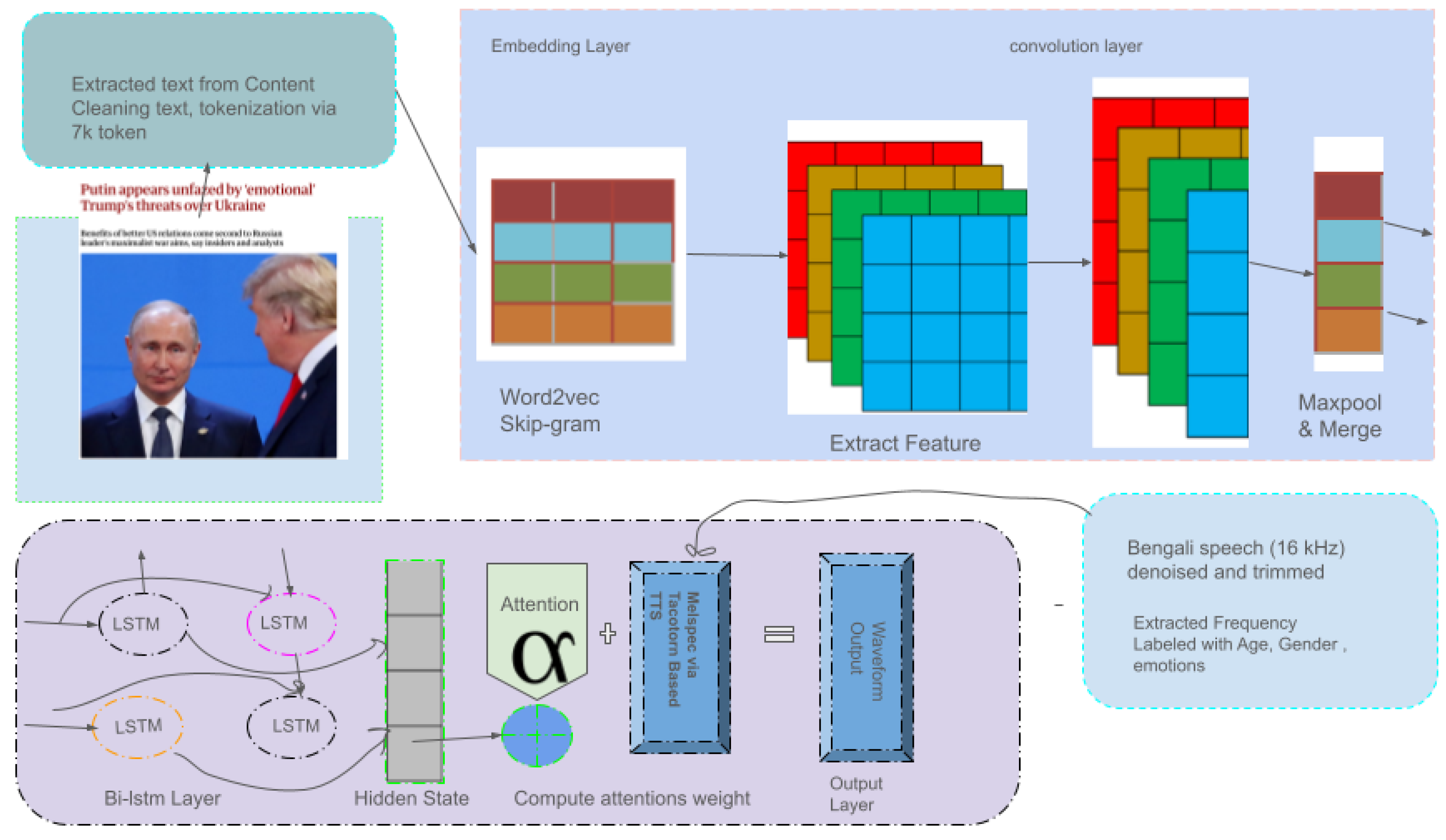

5.3. C. Textual and Audio Approach

The proposed architecture aims to generate meaningful feedback text from an input sequence, which is subsequently converted into audio using a text-to-speech (TTS) synthesis system. The model integrates convolutional and recurrent neural components with an attention mechanism to enhance context understanding and focus.

Figure 2 illustrates the complete architecture.

Let the input text sequence be denoted as:

where

is the vocabulary. Each token

is transformed into a dense embedding vector using a pre-trained Word2Vec Skip-gram model:

These embeddings are passed through a one-dimensional convolutional layer to capture local n-gram patterns within the sequence. For a filter of width

h, the convolutional operation at position

j is defined as:

where * denotes the convolution operation, and

,

are learnable parameters. The resulting feature maps are then subjected to max-pooling to retain the most informative components:

The pooled features are merged to form a unified representation

, which is subsequently fed into a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) network[

2]. The Bi-LSTM captures both forward and backward temporal dependencies:

Figure 2.

The proposed model architecture.

Figure 2.

The proposed model architecture.

To selectively focus on relevant parts of the encoded sequence, an attention mechanism is employed. The attention score for each hidden state

is computed as:

where

denotes the attention weight and

is the resulting context vector.

This context vector

is then used in the decoding phase to generate the output sequence

, with each token predicted auto-regressively:

where

denotes the previous decoder state.

Finally, the generated feedback text sequence is passed to a Tacotron 2-based text-to-speech system to synthesize a mel-spectrogram:

This mel-spectrogram is converted into a high-fidelity waveform using the WaveGlow vocoder:

The end-to-end system thus transforms input textual content into context-aware feedback, rendered both in text and speech, offering a fully integrated language and speech generation solution.

5.4. D. Multimodal Approach

The proposed architecture is a two-stage model that takes an input image I and outputs an audio waveform corresponding to an emotion-specific feedback response. The system consists of:

A facial emotion recognition (FER) module,

A sequence generation module (text decoder),

A Tacotron 2 + WaveGlow-based speech synthesis pipeline.

1. Stage I: Facial Emotion Recognition (FER)

Given an input image , the goal is to classify it into one of K emotion categories.

where are filters, biases at layer l, and MaxPool reduces spatial dimensions.

Flatten and Fully Connected Layers:

Let the predicted emotion label be .

2. Stage II: Emotion-to-Text Feedback Generation

The predicted emotion label e is converted into a word sequence using pre-defined or learned templates, and passed through a sequence generation model.

where is the generated feedback word at time t.

3. Stage III: Speech Synthesis with Tacotron 2 + WaveGlow

The generated text sequence

is converted into a mel-spectrogram:

Then, WaveGlow generates the raw audio waveform:

Final Output

The output of the pipeline is a spoken feedback response, conditioned on the facial emotion detected from the image:

6. Results and Performance Analysis

Here, the performance evaluation of the proposed real-time Facial Expression Recognition (FER) system with integrated Bengali audio feedback has been discussed. The evaluation consists of a comparative analysis of benchmark pre-trained models and our uniquely created model, as well as a review of the feedback generation module.

6.1. Performance of Pre-Trained Models

Two deep neural networks, ResNet-50 and MobileNetV2, were selected as benchmark models for facial emotion detection. These models are widely applied in the image classification community and have complementary strengths of depth and efficiency. ResNet-50 is acclaimed for its deep residual learning characteristics and strong classification accuracy, and therefore it performs suitably in learning complex spatial features. MobileNetV2, by contrast, is desirable because of its light-weighted and efficient architecture that is a necessity for real-time applications and operation on low-end devices. Together, these models present a balanced reference point for weighing accuracy against computational cost in FER systems.

6.1.1. ResNet-50

ResNet-50 (Residual Network of 50 layers) is a convolutional neural network that is deep and employs skip connections or residual blocks to prevent the vanishing gradient issue. Utilization of such connections allows gradients to bypass some of the layers, allowing deeper networks to be trained without a decline in performance. The model consists of 50 layers, with its architecture consisting predominantly of bottleneck residual blocks—three convolutional layers, batch normalization, ReLU activations, and pooling layers for each. This architecture enables the model to possess fine-grained spatial hierarchies in face images.

For us, input images were resized to pixels and the final classification layer was modified to generate seven emotion classes. Training was carried out for 20 epochs. ResNet-50 attained a training accuracy of 56.59

6.1.2. MobileNetV2

MobileNetV2 is a computationally light convolutional neural network structure designed for mobile and embedded vision applications. It prioritizes low computational cost and memory. Its key contribution is using inverted residual blocks and linear bottlenecks. Inverted residual topology increases the number of channels, conducts depthwise convolutions, and projects back down to a lower dimension, significantly reducing the amount of computation. Linear bottlenecks maintain information with minimized redundancy.

The model employs Depthwise Separable Convolutions and ReLU6 activation, both of which are employed for enhancing the quantization compatibility for mobile deployment. MobileNetV2 was trained on emotion classification using the same data and preprocessing steps for comparison. The model reported a training accuracy of 60.82

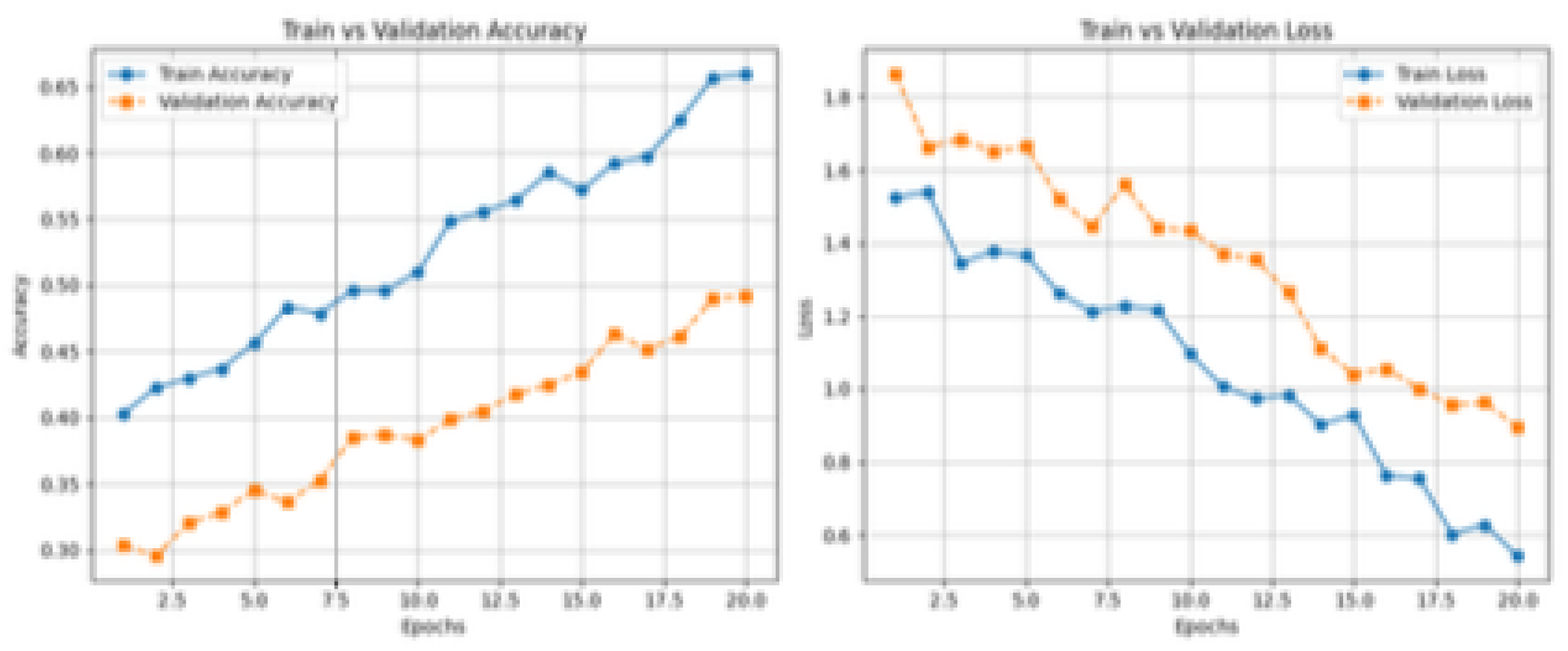

6.2. Performance of the Proposed Model

Our specially crafted model, referred to as Best_FER, was run and evaluated on the preprocessed multimodal dataset. The model features a hybrid CNN-RNN architecture to effectively capture both hierarchical spatial features and temporal progression of facial expressions. Regularization techniques using a dropout value of 0.25 were employed to prevent overfitting. Dilated convolution enabled the model to capture more spatial-wide patterns by expanding the receptive field without increased computational cost.

Batch normalization was used to stabilize training and accelerate convergence. Training was further optimized using an adaptive learning rate scheduler. Best_FER in all achieved training accuracy of 65.12% and validation accuracy of 50.34%, outperforming both ResNet-50 and MobileNetV2 in this task.

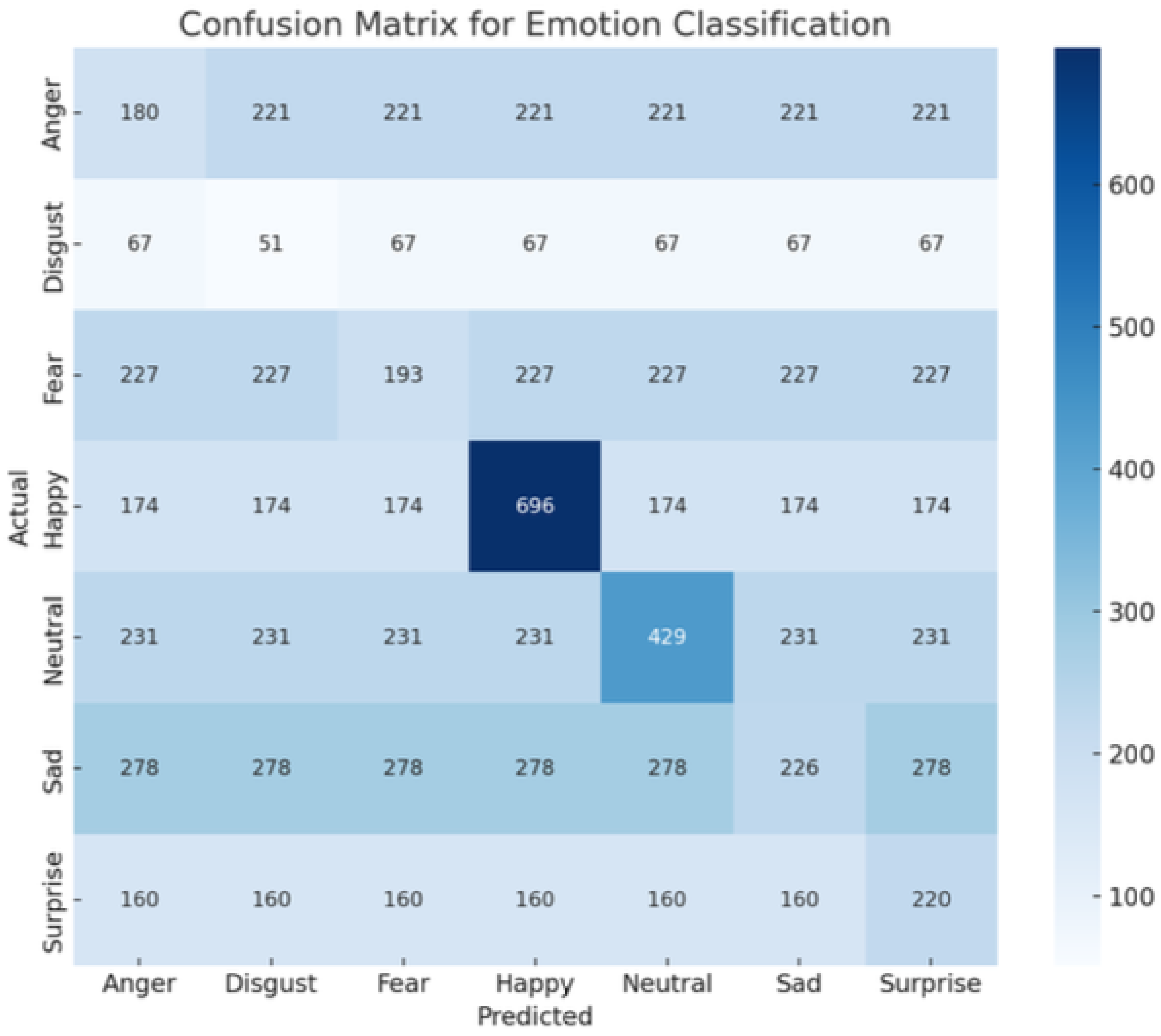

The best_FER classification performance indicators are presented in Table 5.1. The model shows an overall accuracy of 58%, indicating its ability to recognize facial expressions under diverse conditions and achieve real-time performance sufficiency.

The class-wise performance indicates that the "Happy" emotion achieved the highest precision (80%) and recall (78%), resulting in an F1-score of 79%. "Neutral" and "Surprise" emotions also exhibited robust performance with F1-scores exceeding 60%. Conversely, "Disgust" showed a comparatively lower recall of 48%, suggesting more frequent misclassifications for this category. The macro and weighted averages confirm the model’s moderate overall performance in recognizing emotions.

Figure 3.

FER Confusion Matrix

Figure 3.

FER Confusion Matrix

Figure 4.

Performance Visualization of Best_FER Model

Figure 4.

Performance Visualization of Best_FER Model

Table 3.

Classification Report of the Proposed Model

Table 3.

Classification Report of the Proposed Model

| Class |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-Score |

Support |

| Anger |

0.45 |

0.50 |

0.47 |

401 |

| Disgust |

0.44 |

0.48 |

0.46 |

118 |

| Fear |

0.46 |

0.40 |

0.43 |

420 |

| Happy |

0.80 |

0.78 |

0.79 |

870 |

| Neutral |

0.65 |

0.65 |

0.65 |

660 |

| Sad |

0.45 |

0.42 |

0.43 |

504 |

| Surprise |

0.58 |

0.62 |

0.60 |

380 |

| Accuracy |

|

0.58 (3607) |

| Macro Avg |

0.55 |

0.55 |

0.55 |

3607 |

| Weighted Avg |

0.58 |

0.58 |

0.58 |

3607 |

6.3. Feedback Generation Performance

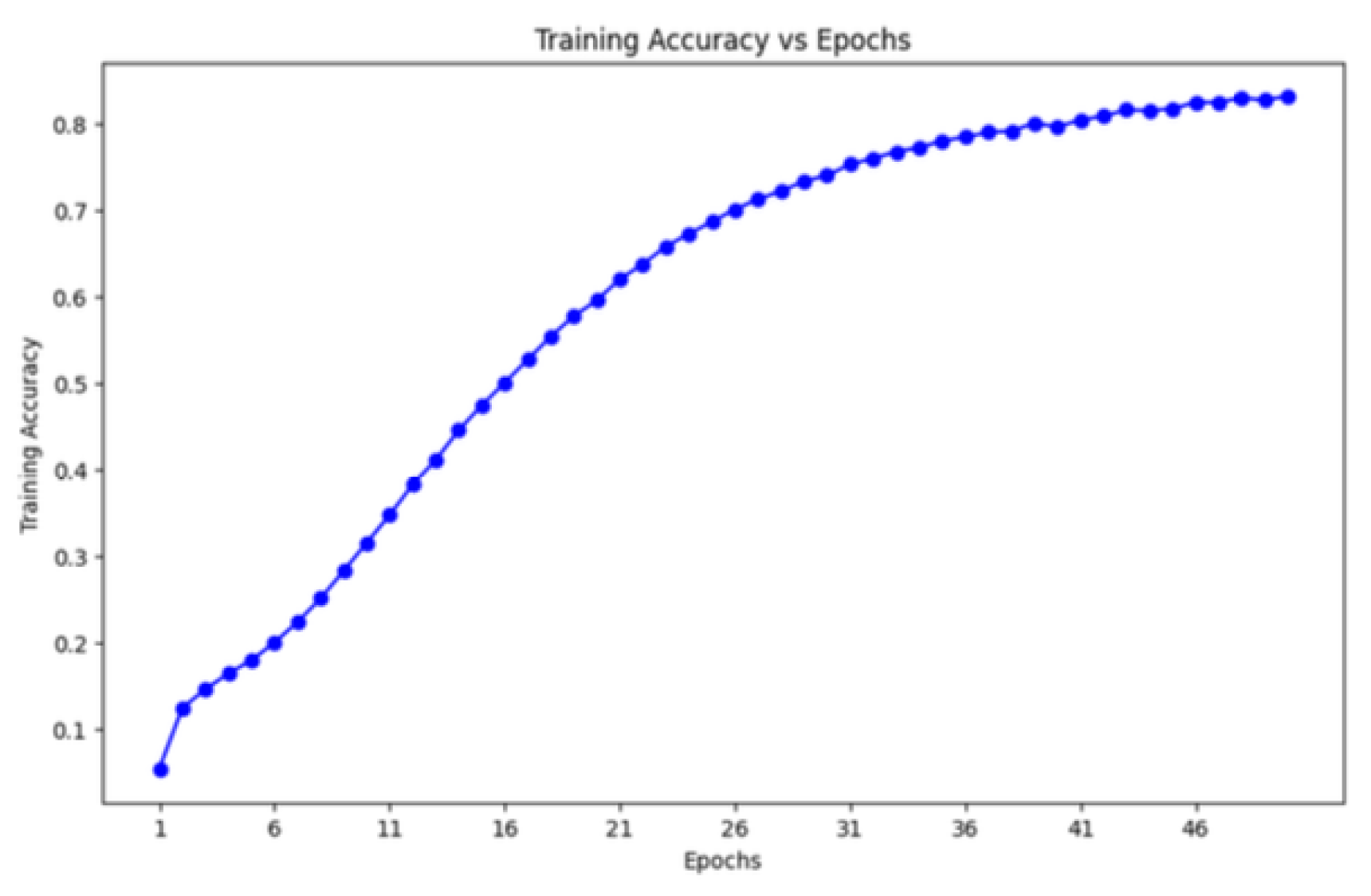

The LSTM-based model developed for sequence generation, responsible for producing Bengali audio feedback, achieved an accuracy of 83.18% and a loss value of 0.6493 after 50 epochs of training with hyperparameter optimization. The post-processing phase, involving a Bengali text-to-speech system, further enhanced the naturalness and fluency of the audio output.

Figure 5.

performance graph of Feedback Genaration model.

Figure 5.

performance graph of Feedback Genaration model.

This custom model demonstrated lower inference time and a reduced model footprint compared to deep pre-trained networks, attributed to techniques such as model pruning and quantization, along with optimized training approaches for generalizability across various face datasets. The integration of this audio feedback system in Bengali provides an additional layer of accessibility and effective emotion feedback.

7. Discussion

The findings of this study underscore the potential of hybrid deep learning models in enhancing real-time facial expression recognition (FER) systems, particularly when integrated with culturally specific audio feedback. The proposed hybrid CNN-RNN model, referred to as Best_FER, outperformed widely-used pre-trained models such as ResNet-50 and MobileNetV2 in both training and validation accuracy. This supports the hypothesis that task-specific architectures tailored for emotion recognition—rather than generic image classification models—can yield superior performance in real-world, multimodal applications.

Table 4.

Comparison of Model Performance for FER

Table 4.

Comparison of Model Performance for FER

| Model |

Training Accuracy (%) |

Validation Accuracy (%) |

| ResNet-50 |

56.59 |

33.42 |

| MobileNetV2 |

60.82 |

45.69 |

| Best_FER (Proposed Model) |

65.12 |

50.34 |

The model’s performance in recognizing positive emotions like Happy and Neutral was particularly strong, as indicated by F1-scores of 79% and 65%, respectively. However, relatively lower precision and recall scores for negative emotions such as Disgust and Fear suggest an area for improvement. These discrepancies may stem from subtle variations in facial muscle movement or dataset imbalances. Such findings align with prior research that identified negative emotions as more difficult to classify due to their less distinct facial markers and greater subjectivity in human annotation.

The integration of Bengali audio feedback through a sequence-to-sequence LSTM model significantly improved the overall interactivity and accessibility of the system. The feedback generation module achieved an accuracy of 83.18%, demonstrating strong alignment between emotion classification and the synthesis of relevant spoken responses. These results validate the hypothesis that native language support in FER systems can enhance user engagement and inclusivity, particularly for underserved linguistic groups like Bengali speakers.

Moreover, the study contributes to ongoing discourse on multimodal emotion recognition by validating the feasibility of combining visual and auditory modalities. The use of synchronized image-text-audio datasets allowed for more robust training and evaluation of the system, ensuring better generalization across various demographic groups. This aligns with previous literature suggesting that multimodal deep learning improves emotion recognition performance, though challenges remain regarding data synchronization and computational overhead .

The current system also demonstrates strong potential for real-time deployment, thanks to its lightweight architecture and use of optimization strategies such as dropout regularization, batch normalization, and adaptive learning rates. Despite these achievements, limitations persist. The FER model’s performance can still be affected by environmental variables like poor lighting or occlusions, which future studies should aim to mitigate using more advanced preprocessing or transformer-based architectures.

Future research may focus on expanding the dataset to include more nuanced emotions and diverse facial types, enhancing cross-cultural applicability. Additionally, incorporating physiological signals (e.g., EEG, heart rate) and spoken language cues could further enrich emotional context. Advancements in Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) might also be explored for context-aware emotion recognition, albeit with careful consideration of their computational demands and potential biases

Overall, the integration of deep learning with culturally sensitive audio feedback offers promising pathways toward emotionally intelligent, inclusive, and linguistically adaptable human–AI interaction systems. This work not only fills a critical gap in Bengali language support for emotion recognition but also lays a foundation for future innovations in multimodal affective computing.

8. Conclusions

This work proposes a real-time facial emotion recognition (FER) system with embedded Bengali audio feedback that offers a robust platform for accurate emotion recognition and response generation. Using cutting-edge deep learning techniques, including hybrid CNN-RNN models and LSTM-based feedback systems, the system accurately recognizes facial emotions and generates contextually relevant audio responses in Bengali.

With rigorous comparative comparisons against the standard pre-trained architectures and self-designed Best_FER model, the better accuracy and generalization performance of the proposed model are superior for datasets of different types. These findings highlight the efficiency of optimized architecture design, regularization techniques, and adaptive learning processes for enhancing FER performance.

The addition of live Bengali audio feedback greatly improves usability for native speakers of the language, with more natural and effective human-computer interaction provided across assistive technologies, education systems, and customer service.

While highly promising in terms of outcome, the system is currently constrained by lighting variations, occlusions, and cross-cultural differences in facial displays. Further work will focus on increased model robustness with larger and more diverse datasets and improved real-time processing performance.

Moreover, the incorporation of multimodal inputs—i.e., speech and physiology signals—will provide additional value to emotion recognition so that the system becomes more sensitive and context-sensitive. As a whole, this work makes a contribution to affective computing by offering an efficient Bengali-enhanced FER system and lays the foundation for future research in multimodal deep learning towards emotionally intelligent human-computer interaction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.; methodology, A.S.; software, A.S.; validation, A.S.; formal analysis, A.S.; investigation, A.S.; resources, A.S.; data curation, A.S..; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, A.S.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants or animals and was conducted as part of an undergraduate thesis approved by the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, BRAC University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express sincere gratitude to Mr. Moin Mostakim, thesis supervisor , Senior lecturer at the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, BRAC University, for his continuous support, guidance, and valuable feedback throughout the research and preparation of this thesis

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Scherer, M.J. Assistive Technology: Matching Device and Consumer for Successful Rehabilitation; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2002.

- Graves, A.; Schmidhuber, J. Framewise phoneme classification with bidirectional lstm and other neural network architectures. Neural Netw. 2005, 18, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, S.A.; Rahman, M.L.; Ahmed, F. A review on bangla phoneme production and perception for computational approaches. In Proceedings of the 7th WSEAS International Conference on Mathematical Methods and Computational Techniques In Electrical Engineering, 2005; pp. 346–354.

- Fathurahman, K.; Lestari, D.P. Support vector machine-based automatic music transcription for transcribing polyphonic music into musicxml. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Informatics (ICEEI), Bali, Indonesia, 10–11 August 2015; pp. 535–539. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F. Multi-scale context aggregation by dilated convolutions. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.07122. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, F. The limitations of deep learning. In Deep Learning with Python; Manning Publications: Shelter Island, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.N. Cyclical learning rates for training neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Santa Rosa, CA, USA, 24–31 March 2017; pp. 464–472. [Google Scholar]

- Baltrušaitis, T.; Ahuja, C.; Morency, L.P. Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 41, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buda, M.; Maki, A.; Mazurowski, M.A. A systematic study of the class imbalance problem in convolutional neural networks. Neural Netw. 2018, 106, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.N. A Disciplined Approach to Neural Network Hyper-Parameters: Part 1 – Learning Rate, Batch Size, Momentum, and Weight Decay. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.09820. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1803.09820 (accessed on 22 July 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K., N.; Patil, A. Multimodal Emotion Recognition Using Cross-Modal Attention and 1D Convolutional Neural Networks. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:226202203 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Nadimuthu, S.; Dhanaraj, K.R.; Kanthan, J. Brain tumor classification using convolution neural network. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2021, 1916, 012206. [Google Scholar]

- Maithri, M.; Raghavendra, U.; Gudigar, A.; et al. Automated emotion recognition: Current trends and future perspectives. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 215, 106646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monica, S.; Mary, R.R. Face and emotion recognition from real-time facial expressions using deep learning algorithms. In Congress on Intelligent Systems; Saraswat, M., Sharma, H., Balachandran, K., Kim, J.H., Bansal, J.C., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2022; pp. 451–460. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Song, W.; Tao, W.; et al. A systematic review on affective computing: Emotion models, databases, and recent advances. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.06935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatakrishnan, R.; Goodarzi, M.; Canbaz, M.A. Exploring large language models’ emotion detection abilities: Use cases from the middle east. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Conference on Artificial Intelligence (CAI), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 5–7 June 2023; pp. 241–244. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, Y.; Küster, D.; Liu, H.; Krumhuber, E.G. Understanding naturalistic facial expressions with deep learning and multimodal large language models. Sensors 2024, 24, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, Y.; Küster, D.; Liu, H.; Krumhuber, E.G. Understanding naturalistic facial expressions with deep learning and multimodal large language models. Sensors 2024, 24, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahal, A.; Moulik, S. The multi-model stacking and ensemble framework for human activity recognition. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, X.; Xing, B.; et al. Eald-mllm: Emotion analysis in long-sequential and de-identity videos with multi-modal large language model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.00574. [Google Scholar]

- Ouali, S. Deep learning for arabic speech recognition using convolutional neural networks. J. Electr. Syst. 2024, 20, 3032–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Facial Expression Dataset Statistics.

Table 1.

Facial Expression Dataset Statistics.

| Class |

Train |

Val |

Test |

Total |

NW |

NUW |

AW |

| Happy |

2580 |

322 |

323 |

3225 |

28940 |

9330 |

11.16 |

| Angry |

1760 |

215 |

218 |

2193 |

19670 |

7084 |

11.01 |

| Disgust |

1320 |

165 |

170 |

1655 |

14390 |

4992 |

11.36 |

| Fear |

1420 |

178 |

180 |

1778 |

15791 |

5320 |

11.10 |

| Sad |

1900 |

240 |

240 |

2380 |

21980 |

7103 |

12.04 |

| Surprise |

1550 |

195 |

195 |

1940 |

17991 |

6453 |

11.79 |

| Neutral |

2820 |

355 |

359 |

3534 |

30885 |

10420 |

10.97 |

| Total |

13450 |

1670 |

1685 |

16785 |

149647 |

50702 |

- |

Table 2.

Bengali Feedback Dataset Statistics.

Table 2.

Bengali Feedback Dataset Statistics.

| Emotion |

Text Samples |

Audio Samples |

Avg. Words |

Avg. Duration (s) |

| Happy |

912 |

703 |

8.6 |

2.1 |

| Sad |

840 |

680 |

9.1 |

2.3 |

| Angry |

721 |

615 |

7.4 |

2.0 |

| Fear |

603 |

520 |

8.2 |

2.2 |

| Disgust |

497 |

412 |

7.9 |

2.1 |

| Surprise |

672 |

541 |

8.7 |

2.0 |

| Neutral |

820 |

690 |

7.8 |

1.9 |

| Total |

6065 |

4161 |

- |

- |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).