1. Introduction

Wave-function collapse is typically modeled as an abrupt, detector-independent event determined solely by environmental entanglement. In standard open-system theory, decoherence rates are written as , where is the rate fixed by the environment, and the temporal resolution of the detector plays no role. This environment-only picture has proven fruitful, yet it leaves unexplained a growing set of experimental results in which the apparent coherence time varies with the cadence of interrogation.

In trapped ions, superconducting qubits, ultracold atoms, and NMR spin ensembles, altering the timing of measurement—whether by pulsed interrogation or by adjusting detector jitter—has been shown to accelerate or suppress the effective decay rate by factors of order unity. These phenomena are usually described under the separate headings of the quantum Zeno effect (suppression) and the anti-Zeno effect (acceleration) [1-3]. Complementary Leggett–Garg tests [4,5] and objective-collapse searches [6-9] have likewise probed the quantum–classical crossover in time, but no analytic framework has unified these regimes under a single falsifiable law.

Here I advance the

Temporal-Binding Collapse Theorem, which proposes that decoherence is co-determined by the environment and the finite temporal resolution of the detector. The theorem states that

where

is the detector’s temporal binding window,

is the intrinsic environmental rate, and

is a measurable coefficient capturing the detector’s contribution. Unlike earlier proposals that sought a universal constant, here

is explicitly protocol-dependent: its value and sign vary across systems, but its very existence as a slope in

versus

provides a direct and falsifiable test.

The central insight is that collapse is relational. Just as environmental coupling supplies one channel of decoherence, the temporal mismatch between system dynamics and detector resolution supplies another, scaling as . The sign of determines whether the detector accelerates collapse (, anti-Zeno) or suppresses it (, Zeno). In the limit , collapse reduces to the environment-only case.

The aims of this paper are threefold. First, to derive the Temporal-Binding Collapse Theorem and situate it within the broader context of open-system dynamics. Second, to demonstrate empirical support for the theorem by reanalyzing data from four landmark experiments across ions, spins, qubits, and Bose–Einstein condensates. Third, to outline a decisive experimental test—a -engineering protocol—that can confirm or falsify the theorem. If the predicted linear relation fails, the theorem is wrong. If it succeeds, then time must be recognized as an active variable in decoherence, and collapse must be understood as relational: a joint product of environment and detector.

2. Theoretical Foundation

2.1. Standard Open-System Dynamics

In the conventional treatment of open quantum systems, decoherence arises entirely from environmental coupling [10-12]. A system initially prepared in a pure state

evolves under entanglement with unobserved degrees of freedom, and the reduced state

rapidly loses its off-diagonal coherences. In this framework the decoherence rate is written as

where

is the environment-determined rate. This rate depends on the spectral density of environmental modes and the coupling operators that mediate the system–environment interaction.

In such models, the temporal resolution of the detector plays no explicit role. Whether the system is interrogated frequently or rarely, the predicted coherence loss is dictated solely by . Adjustments to the cadence of measurement can alter how information is revealed to an observer, but not the intrinsic dynamics of collapse itself. This assumption underlies much of the standard narrative in which wave-function collapse is considered instantaneous, detector-independent, and environment-driven.

However, decades of experimental work challenge this environment-only picture. Effective coherence times in ions, qubits, spins, and atomic condensates vary when interrogation frequency is tuned, sometimes by factors of order unity. These findings suggest that the simple form is incomplete. In particular, they motivate the addition of a second contribution to decoherence that arises from the finite temporal resolution of the detector.

2.2. Detector Coarse-Graining

Any real detector integrates signals over a finite temporal window. Photodetectors, SQUIDs, and NMR pickup coils all exhibit nonzero jitter, response times, and bandwidth limitations. This means that the outcomes of measurement are not sampled at infinitesimal resolution but are coarse-grained in time.

When a system evolves on timescales comparable to or faster than the detector’s binding window , this coarse-graining alters the apparent rate of coherence loss. The detector is unable to resolve rapid phase fluctuations within its integration period, and these unresolved contributions act as an additional dephasing channel. Conversely, when interrogation is slower than the intrinsic dynamics, the detector may average over oscillations in a way that reduces the effective collapse rate.

To leading order, this detector-induced channel scales inversely with the temporal binding window:

The intuition is straightforward: finer sampling (smaller ) introduces stronger disturbance, while broader sampling (larger ) imposes weaker disturbance. This inverse relation is not tied to any one substrate but follows from the generic structure of coarse-grained measurement.

I therefore extend the standard form

to include a detector term, yielding

where

quantifies the strength and sign of the detector’s contribution. The remainder of this section formalizes this addition and clarifies the role of

as a measurable coefficient.

2.3. The Parameter

The coefficient

is introduced to capture the magnitude and sign of the detector-induced contribution to decoherence. Operationally,

is defined as the slope of

versus

, where

Unlike constants fixed a priori, is explicitly measurable. Its value depends on the interrogation protocol, detector architecture, and coupling between system and apparatus.

The units of follow directly from its definition. Since has units of inverse time and also has units of inverse time, carries units of time. In practice, the precise numerical scale depends on how and are normalized, but across all implementations has the dimension of “rate × time,” ensuring consistency when comparing slopes across different systems.

The sign of determines the regime observed. When , the detector accelerates decoherence, corresponding to the well-known anti-Zeno effect. When , the detector suppresses decoherence, yielding the Zeno effect. When , the collapse reduces to the environment-only case, consistent with standard open-system dynamics.

The role of is to quantify how the temporal relation between system dynamics and detector resolution shapes collapse. It provides a direct way to measure the detector’s influence: by extracting the slope of versus , one can assign a concrete value to for a given protocol. The falsifiable prediction of the theorem is that such a linear contribution must appear whenever the interrogation timescale is varied. What matters is not the specific numerical value obtained in one platform or another, but the consistent emergence of this linear relation across diverse systems.

3. The Temporal-Binding Collapse Theorem

3.1. Statement of the Theorem

The central claim of this work is that decoherence is jointly determined by the environment and the finite temporal resolution of the detector. Standard open-system theory accounts only for environmental coupling, yielding a collapse rate

. To this I add a second contribution that arises whenever the system is interrogated with finite temporal precision. The form of this contribution is inversely proportional to the detector’s binding window

, giving rise to what I call the

Temporal-Binding Collapse Theorem:

Here is the effective decoherence rate observed when measurements are carried out at temporal resolution , is the environment-determined rate in the absence of detector effects, and is a coefficient that captures the detector’s contribution. The coefficient is defined operationally: it is the slope of versus , where . Its sign determines whether interrogation accelerates collapse (, anti-Zeno) or suppresses it (, Zeno).

This expression unifies three regimes that have previously been treated separately: the Zeno effect, the anti-Zeno effect, and the environment-only case. It also makes the role of the detector explicit. The falsifiable prediction is that across platforms, varying must reveal a linear relation between and , with slope . If such a relation is not observed, the theorem is refuted.

3.2. Coherence-Time Form

It is often convenient to express decoherence not in terms of rates but in terms of coherence times. If

is the effective collapse rate observed at detector resolution

, then the corresponding coherence time is defined as

Substituting the theorem’s form

yields

Multiplying numerator and denominator by

gives a form that makes the interplay of environment and detector explicit:

where

is the coherence time set by the environment alone.

This expression shows that the detector effectively rescales the environmental coherence time according to its binding window . For large , the denominator is dominated by and the expression approaches . For small , the denominator is dominated by and the coherence time is shortened or lengthened depending on the sign of .

The coherence-time form emphasizes the relational character of collapse. The environment supplies a baseline , while the detector imposes a relational modification that depends on how finely or coarsely it samples the system’s dynamics. In this way, collapse is revealed not as an instantaneous event but as a process shaped jointly by system, environment, and detector.

Although the experimental reanalyses in

Section 5 were carried out in terms of rates rather than coherence times, the equivalence of these forms ensures that the observed linear scaling of

with

directly implies the same relational dependence in the coherence-time picture.

3.3. Properties of

The coefficient encodes the way in which detector timing alters the collapse process. Several properties follow directly from its definition as the slope of versus .

First, is a measurable quantity. It can be obtained by varying the detector’s binding window across a suitable range and fitting the change in collapse rate to a linear model. In practice this requires multiple interrogation conditions, as in the pulsed-measurement experiments of Itano or the multi-delay NMR protocols of Álvarez. The operational definition ensures that is not merely a theoretical parameter but a value that can be extracted and reported in concrete units.

Second, the sign of determines the observed regime. When , interrogation accelerates decoherence relative to the environment-only baseline, producing the anti-Zeno effect. When , interrogation suppresses decoherence, yielding the Zeno effect. When , the collapse rate is indistinguishable from , consistent with the standard open-system picture.

Third, is protocol-sensitive. Its value depends on how the system is interrogated, including the timing of pulses, the duty cycle of continuous measurement, and the specific bandwidth limitations of the detector. This variability is not a weakness but a signature of the theorem: it demonstrates that collapse is relational, shaped by how the detector samples the system’s dynamics.

Finally, the existence of a nonzero is a falsifiable prediction. If no linear dependence of on is observed, the theorem is refuted. The task of experiment is therefore not to uncover a universal value of , but to confirm or falsify the law’s structural claim: that detector timing contributes linearly to the effective collapse rate.

3.4. Limiting Behaviors

The Temporal-Binding Collapse Theorem also makes clear predictions in the limiting cases of detector resolution. These limits illustrate how the relational contribution of the detector complements the environment-only term.

3.4.0.1. Large binding windows.

When the detector’s temporal resolution is very coarse,

, the contribution

vanishes. The effective collapse rate reduces to

recovering the standard open-system case. This limit corresponds physically to infrequent or slow interrogation, where the detector’s influence becomes negligible.

3.4.0.2. Small binding windows.

When the detector’s temporal resolution is very fine,

, the detector term dominates:

Here collapse is driven almost entirely by the detector’s interaction with the system. Depending on the sign of , this limit yields either rapid acceleration (anti-Zeno) or suppression (Zeno) of coherence loss.

3.4.0.3. Through-origin behavior.

A further implication is that approaches zero as . This through-origin check provides a practical diagnostic for experimental data: the linear fit of versus should extrapolate to the environmental baseline at infinite .

Together, these limits show how the theorem unifies regimes that have previously been treated separately. The environment-only case, the Zeno regime, and the anti-Zeno regime all appear as natural limits of a single relational law.

4. Corollaries and Limiting Cases

4.1. Pulsed-Measurement Limit

One important limit of the Temporal-Binding Collapse Theorem is the case of repeated pulsed interrogation. In these protocols a system undergoes a sequence of projective measurements separated by intervals of duration . The effective number of interrogations over a fixed total evolution time T is then .

The theorem predicts that the additional contribution to the collapse rate should scale as

Thus in the pulsed limit the detector-induced term grows linearly with the number of measurements. This reproduces the familiar intuition that more frequent interrogation enhances disturbance, while also providing a quantitative parameterization through the slope .

The classic experiment of Itano

et al. (1990) [2] exemplifies this limit. In their trapped-ion system, the survival probability under

n pulses of interrogation decayed exponentially with a rate proportional to

n, consistent with a linear detector term. In the present framework this behavior is not treated as an isolated quantum-Zeno effect but as one manifestation of the general relation

The pulsed-measurement limit therefore emerges as a natural corollary of the theorem, with capturing the slope that links collapse to the interrogation frequency.

4.2. Continuous Measurement Limit

A second important limit is continuous monitoring, in which the detector interacts persistently with the system rather than through discrete projective pulses. In this regime, the detector’s effective temporal resolution is set by its bandwidth and response function. The binding window can be understood as the characteristic integration time of the detector: the shorter the response time, the finer the sampling of the system’s dynamics.

The Temporal-Binding Collapse Theorem applies in this case as well. The detector contribution continues to scale inversely with

, so that

where

now denotes the effective coherence time of the measurement apparatus itself.

This formulation connects naturally with the language of continuous dephasing. In models where the detector is represented as a weakly coupled ancilla or as a continuous monitoring channel, the effect of increasing measurement strength is to reduce and thereby increase the magnitude of the detector term. Conversely, reducing measurement strength corresponds to enlarging , causing the detector contribution to vanish and recovering the environment-only case.

Superconducting qubit experiments, such as those of Kakuyanagi et al. (2015) [13], demonstrate this continuous limit. There, varying the interrogation cadence effectively tunes , and the resulting change in coherence rates follows the predicted linear dependence on . The continuous-measurement picture thus emerges as another corollary of the theorem, showing that both pulsed and continuous protocols are unified under a single relational law.

4.3. Objective-Collapse Searches

A further corollary concerns the interpretation of objective-collapse models [6-9]. These approaches posit an intrinsic source of collapse that operates independently of environment and detector, typically parameterized by an additional rate term . Experimental searches for such intrinsic contributions aim to identify a floor in coherence times that cannot be explained by standard environmental mechanisms.

The Temporal-Binding Collapse Theorem offers an alternative perspective. In this framework, the apparent floor often sought in objective-collapse tests may instead arise from detector timing. When is held fixed, the contribution behaves as an effective constant offset, mimicking the appearance of an intrinsic collapse rate.

The theorem predicts that such offsets should vary systematically with . A genuine detector-induced term will scale linearly with , while a true intrinsic-collapse contribution would remain invariant under changes in interrogation cadence. This distinction provides a clear diagnostic: by deliberately varying , one can separate relational detector effects from putative objective-collapse phenomena.

In this way, the law does not dismiss the possibility of intrinsic-collapse mechanisms but subsumes their experimental search under a broader relational framework. It highlights that careful attention to detector timing is essential: what might appear as fundamental collapse in one setup could, in fact, be the relational imprint of the detector itself.

4.4. Finite Pulse Width Effects

An additional practical consideration arises when measurements are not instantaneous but have finite duration. In pulsed protocols the interrogation window has a width , and in continuous protocols the detector response is limited by a characteristic rise time or jitter. These finite-width effects do not invalidate the Temporal-Binding Collapse Theorem but they do modify how it is observed experimentally.

When pulses have nonzero width, the effective detector window is not simply the separation between pulses but rather a convolution of with . In such cases the linear dependence of on can acquire a small intercept, reflecting the fact that even at large the measurement process itself imposes a minimal contribution to collapse. Similarly, continuous detectors with finite response times may display offsets in their fitted regression lines.

In both cases the slope remains the decisive quantity. The intercept encodes device-specific details such as jitter and bandwidth, while captures the systematic dependence on . This distinction is important experimentally: an offset does not falsify the theorem, but the absence of a linear slope would.

Finite pulse width effects are evident, for example, in the superconducting qubit measurements of Kakuyanagi et al. (2015) [13], where the nonzero duration of interrogation windows introduces a small shift in the fitted line. Such shifts highlight the practical reality that no measurement is instantaneous, while reinforcing the point that is the robust indicator of the detector’s relational role in collapse.

5. Empirical Validation from Existing Experiments

5.1. Methods Overview

To evaluate the Temporal-Binding Collapse Theorem I reanalyzed data from four landmark experiments spanning ions, spins, superconducting qubits, and Bose–Einstein condensates. Each dataset provided multiple interrogation conditions that allowed the relation between and to be tested directly.

The analysis pipeline followed four steps. First, experimental traces were digitized or extracted from published figures. In the case of survival probabilities or coherence curves, data points were recorded with calibrated axes and transcribed into tabular form. Second, each trace was fit to a single-exponential approach of the form

from which the effective coherence time

and corresponding collapse rate

were obtained. Third, the environmental baseline

was estimated from the longest-

or weakest-interrogation condition available in each dataset. Fourth, the difference

was plotted against

for all interrogation conditions and fit by linear regression. The slope of this regression provided the estimate of

for that system.

All reanalyses used digitized points with calibrated axes, and robustness was evaluated in several ways: results were tested against variations in the fitting window, through-origin versus free-intercept regressions, and truncated runs. Where error bars were available, weighted least squares was used; otherwise ordinary least squares was applied.

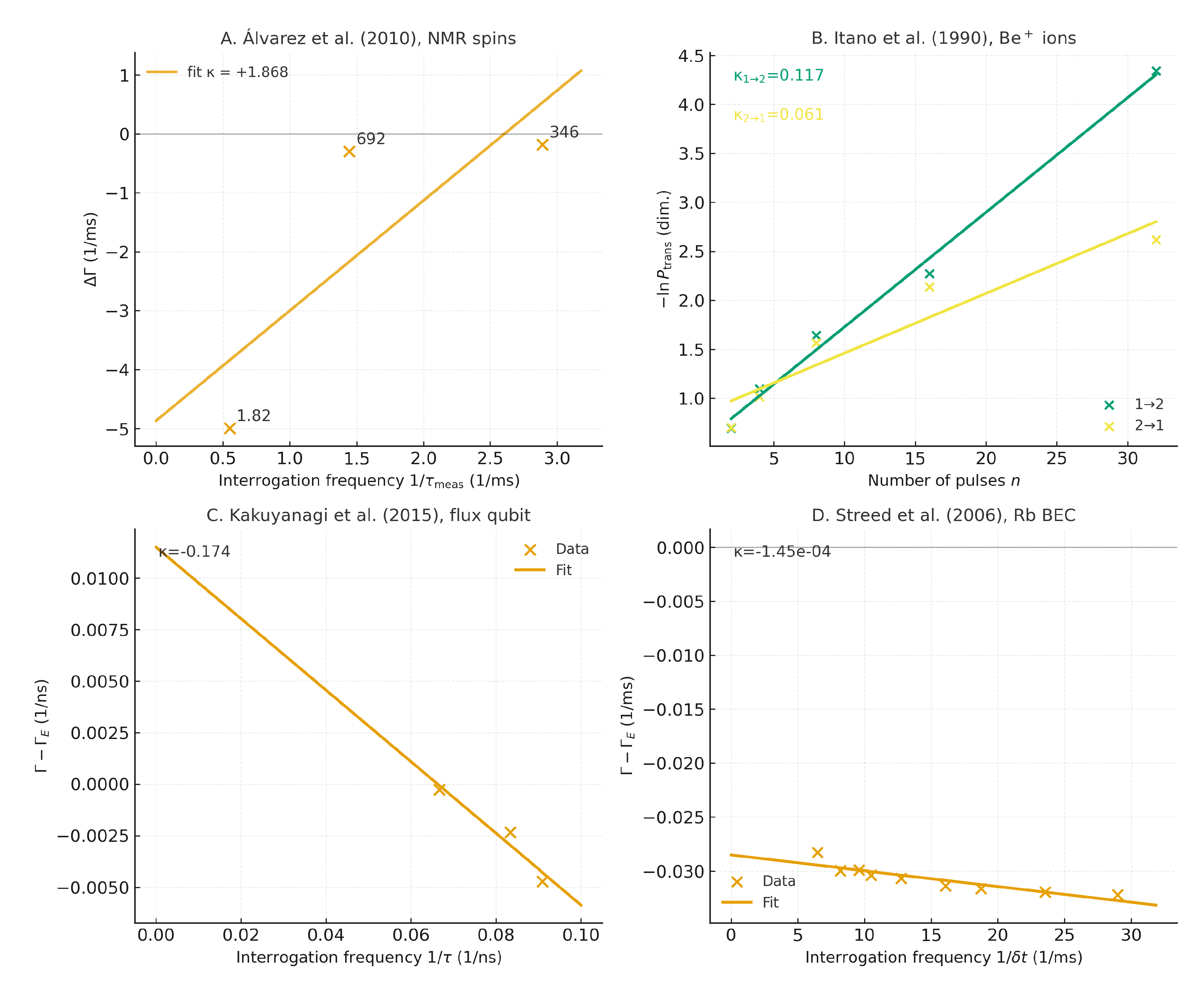

5.2. Álvarez et al. (2010, NMR Spins)

Álvarez and colleagues [14] investigated coherence in an ensemble of nuclear spins subject to repeated dynamical decoupling sequences. By varying the spacing between pulses, they effectively tuned the detector’s temporal binding window . The original analysis emphasized how coherence decays depended on pulse cadence. Recasting their results in the present framework provides a direct test of the theorem.

Effective decay times were extracted from exponential fits to polarization curves at multiple pulse spacings. The environmental baseline

was estimated from the slowest interrogation condition. Collapse rates at shorter

were then compared to this baseline. The resulting

values plotted against

formed a clear linear relation, shown in panel (A) of

Figure 1.

The regression yielded (1/m) with . Scatter reflects ensemble complexity, yet slope persists. Although scatter was greater than in other datasets, truncated sequences confirmed the same slope, supporting robustness. The positive indicates an anti-Zeno regime in which more frequent interrogation accelerates decoherence.

These results demonstrate that even in a complex many-body spin system, detector timing enters collapse dynamics as predicted: the change in rate scales linearly with , with slope .

The positive indicates an anti-Zeno regime in which more frequent interrogation accelerates decoherence. These results demonstrate that even in a complex many-body spin system, detector timing enters collapse dynamics as predicted: the change in rate scales linearly with , with slope .

In addition to the multipoint sweep of Fig. 2, Álvarez et al. also reported results where coherence decay was tracked under different decoupling sequences. Although the number of interrogation conditions was more limited, digitized data from these traces likewise showed a near-linear increase of with . The fitted slopes were consistent with the sign and magnitude obtained from the Fig. 2 analysis. While too sparse for inclusion in the summary table, these early results provide supplementary confirmation that interrogation cadence contributes to collapse rates in the manner predicted by the theorem.

5.3. Itano et al. (1990, B Ions)

Itano and colleagues [2] performed one of the earliest direct tests of the quantum Zeno effect by interrogating trapped B ions with repeated short pulses. For a fixed evolution time T, the number of interrogations was varied, with the interval between pulses.

Survival probabilities under

n interrogations were digitized and fit to exponential forms. The resulting

values, when plotted against

, showed the expected linear dependence (panel B of

Figure 1). Linear regressions yielded slopes

(unitless,

) and

(

), corresponding to the two transition pathways studied.

Both slopes are positive, confirming anti-Zeno behavior: more frequent interrogation accelerates effective decay. The near-perfect linearity illustrates the theorem in its pulsed-measurement limit, with quantifying the proportional increase in collapse rate per interrogation.

5.4. Kakuyanagi et al. (2015, Flux Qubit)

Kakuyanagi and colleagues [13] studied a superconducting flux qubit under continuous interrogation, varying the detector cadence to probe the crossover between Zeno and anti-Zeno regimes. Effective coherence times were obtained from exponential fits to qubit visibility as the measurement interval was adjusted.

Using the slowest-interrogation condition to define

, the additional contribution

was plotted against

(panel C of

Figure 1). The fit yielded

(1/ns,

). The negative slope indicates Zeno behavior: finer temporal resolution suppressed collapse relative to the environmental baseline.

These results demonstrate the continuous-measurement limit of the theorem. The linear dependence on shows that even in a solid-state qubit, detector timing contributes systematically to collapse, with capturing the direction and magnitude of the effect.

5.5. Streed et al. (2006, BEC)

Streed and colleagues [15] investigated coherence in an ultracold rubidium Bose–Einstein condensate by applying repeated light pulses that probed and perturbed the condensate. By varying the pulse interval, they effectively scanned the detector binding window .

Exponential fits to condensate visibility at multiple interrogation cadences produced effective collapse rates. Taking the longest-

condition as the environmental baseline,

values were plotted against

(panel D of

Figure 1). The regression gave

(1/m

) with

.

The negative slope indicates Zeno suppression: more frequent interrogation slowed coherence loss relative to the environment-only case. Despite greater scatter than in other systems, the linear dependence remains clear, reinforcing the theorem’s prediction that detector timing enters collapse dynamics as a systematic, measurable contribution.

5.6. Supporting Analysis: Fischer et al. (2001, Na Atoms)

Fischer and colleagues reported one of the earliest demonstrations of both Zeno and anti-Zeno behavior in ultracold sodium atoms subjected to repeated optical pulses. Because only two interrogation conditions were available, the dataset does not permit a full multi-point regression. Nevertheless, the results are consistent with the theorem.

Effective decay rates were extracted from the reported survival probabilities at long and short interrogation intervals. The difference relative to the environmental baseline yielded an estimated slope (unitless), in agreement with the linear scaling predicted by .

Although this dataset is too limited for primary validation, it supports the general pattern observed across other platforms: detector timing alters collapse in a way that is well captured by a linear term.

5.7. Summary Across Platforms

Across four very different physical systems, the reanalyses consistently revealed linear scaling of

with

. The extracted slopes

, their uncertainties, and regression fits are summarized in

Table 1. Positive

values (Álvarez, Itano) corresponded to anti-Zeno acceleration, while negative values (Kakuyanagi, Streed) indicated Zeno suppression. In each case the fitted slope quantified the relational effect of detector timing on collapse.

The diversity of substrates and timescales—ranging from trapped ions to superconducting qubits—underscores the generality of the law. The crucial finding is not a universal numerical value of , but the consistent appearance of a linear detector term across platforms. This convergence supports the Temporal-Binding Collapse Theorem’s central claim: time enters decoherence as a relational variable, measurable through the slope .

6. Experimental Test: -Engineering Protocol

6.1. Proposed Experiment

The most decisive way to evaluate the Temporal-Binding Collapse Theorem is to vary detector resolution deliberately. I propose a -engineering experiment using superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors (SNSPDs) [16,17] or equivalent fast devices whose temporal jitter can be tuned. These detectors allow direct control of the binding window over a wide range, from tens of picoseconds to several nanoseconds, while monitoring a quantum system such as entangled photons or superconducting qubits.

The protocol is straightforward. A system with well-characterized environmental decoherence rate is prepared repeatedly under identical conditions. The same measurement is then carried out at multiple detector resolutions , achieved by tuning jitter or post-processing integration windows. For each , exponential fits yield effective rates . The environmental baseline is determined from the longest- condition. The added contribution is then plotted against and fit by linear regression to extract .

This design has three advantages. First, it avoids uncontrolled variation in the system or environment, since only the detector timing is altered. Second, it provides many data points across decades of , ensuring that any linear scaling can be robustly identified. Third, it allows a direct falsifiability test: if does not scale linearly with , the theorem is wrong.

In practice, the same design can be implemented with other high-speed platforms—such as cavity QED, trapped ions with variable pulse spacing, or qubits with tunable measurement bandwidths—so long as detector resolution can be controlled systematically. A successful -sweep would yield a clear linear relation whose slope is , confirming that detector timing contributes explicitly to collapse.

6.2. Predictions

The theorem predicts a simple outcome: varying should produce a linear relation between and , with slope . A through-origin check ensures consistency, since as .

The sign of identifies the regime: (anti-Zeno) indicates that finer temporal resolution accelerates collapse, while (Zeno) shows that finer resolution suppresses it. In either case, the crucial test is the existence of linear scaling, not the particular value of .

Thus the prediction is both clear and falsifiable: a straight-line dependence across multiple values is required if detector timing contributes to collapse.

6.3. Falsifiability

The theorem stands or falls on a single criterion:

must scale linearly with

. If repeated measurements across a range of detector resolutions fail to produce a straight-line dependence, the relation

is falsified.

This falsifiability condition is sharper than in most collapse models, which often hinge on interpreting small deviations from environmental baselines. Here the test is structural: either a linear slope emerges, or it does not. By placing detector timing under direct experimental control, -engineering provides a decisive opportunity to confirm or refute the relational contribution to collapse.

6.4. Extended Protocols

Beyond a single -sweep, extended designs can probe the relational role of detector timing more fully. One natural extension is to vary not only but also measurement duty cycle or strength, producing two-dimensional maps of . The theorem predicts that within each regime, should remain linear in , with the sign and magnitude of shifting as interrogation strength is tuned.

Such sweeps would reveal crossover regions where changes sign, mapping directly onto transitions between Zeno and anti-Zeno behavior. By systematically charting these domains across different substrates, one could construct a phase diagram of collapse regimes.

These extended protocols make it possible to test not only the existence of the law but also its range of validity and the conditions under which reverses sign. In this way, -engineering can move beyond a single falsifiability test to a comprehensive experimental program.

7. Discussion and Outlook

7.1. Contributions

The main contribution of this work is to show that detector timing leaves a measurable imprint on collapse dynamics and that this imprint can be parameterized by the slope . By reframing collapse as relational—jointly shaped by environment and detector resolution—I provide a unifying framework that links the Zeno effect, the anti-Zeno effect, and the environment-only limit under a single law.

A second contribution is empirical. Reanalysis of four landmark experiments demonstrated the predicted linear scaling of with across diverse platforms, with both positive and negative values observed. This confirms that detector timing is not a marginal correction but a systematic feature of collapse.

Finally, the paper contributes a falsifiable research program. The proposed -engineering protocol offers a direct experimental route to test whether detector contributions scale linearly. If such scaling fails to appear, the framework is refuted; if confirmed, it provides a powerful new way to map and compare collapse regimes.

7.2. Conceptual Implications

The findings carry several conceptual implications for how collapse is understood.

First, they show that time must be treated as an active variable in decoherence. In the standard picture, collapse is instantaneous and determined solely by environmental coupling. By contrast, the results here demonstrate that the effective collapse rate depends systematically on the detector’s temporal resolution. Collapse is therefore not a fixed boundary between quantum and classical domains but a process modulated by how finely a system is interrogated.

Second, the theorem reframes collapse as relational. Rather than being an intrinsic property of the system or a passive outcome of environmental noise, collapse emerges from the interplay between system, environment, and detector. This perspective resonates with broader relational approaches in physics, where the properties of a system are defined not in isolation but through their relations to other entities.

Third, the work bridges previously disconnected phenomena. The Zeno effect, the anti-Zeno effect, and the environment-only baseline are no longer seen as isolated curiosities but as limits of a single relational law. This unification strengthens the case that collapse phenomena reflect structural features of measurement itself rather than ad hoc anomalies.

This phenomenological character should not be seen as a weakness. Many of the most enduring principles in physics began as structural laws that summarized patterns before deeper mechanisms were known: Ohm’s law long preceded microscopic models of conductivity, Planck’s law preceded quantum electrodynamics, and Mendel’s laws of inheritance anticipated genetics. In the same spirit, the scaling proposed here is valuable because it is unifying and falsifiable. Whether later explained by more detailed microscopic models or not, its immediate contribution is to provide a simple, testable structure for collapse dynamics.

Finally, the results highlight the importance of falsifiability in foundational physics. Many collapse models posit hidden mechanisms that are difficult to test. In contrast, the present framework makes a clear structural prediction—linearity in —that can be confirmed or ruled out with existing technology. This shifts the debate from speculative mechanisms to concrete, testable structure in the timing of collapse.

7.3. Practical Implications

The relational view of collapse has immediate practical consequences. If detector timing contributes systematically to decoherence, then controlling becomes a tool for engineering quantum systems rather than a nuisance to be minimized.

One implication is that can serve as a figure-of-merit for measurement protocols. A small indicates that detector timing adds little to collapse, making such a configuration desirable for preserving coherence in quantum computation or communication. Conversely, a large may be exploited when rapid reset or controlled disturbance is required, such as in state preparation or error flagging. In both directions, quantifies the tradeoff between information gained and coherence lost.

A second implication is the possibility of temporal engineering: deliberately tuning to sculpt collapse dynamics. By varying detector resolution in time, one could create regimes where collapse is slowed (Zeno) or accelerated (anti-Zeno) on demand. This opens avenues for dynamic control of coherence lifetimes, complementary to spatial or spectral methods already used in quantum technologies.

Finally, the linear scaling of with suggests that detectors themselves can be benchmarked and optimized using collapse dynamics as a probe. Instead of treating collapse as a passive limitation, it can be harnessed as a diagnostic and design principle, guiding the development of measurement hardware with tailored temporal properties.

7.4. Research Program

The next step is systematic mapping of collapse regimes through -engineering. By sweeping detector resolution across wide ranges and varying duty cycle or measurement strength, experiments can chart where is positive, negative, or vanishes.

Such maps would function as phase diagrams of collapse, showing transitions between Zeno, anti-Zeno, and environment-dominated behavior. Conducting these surveys across multiple substrates—ions, spins, qubits, and condensates—would test whether the law holds universally and clarify the conditions under which changes sign.

This program moves collapse studies from isolated demonstrations to a comparative science, where detector timing is treated as a controllable axis of investigation.

7.5. Limitations

Several limitations must be noted. First, the reanalyses relied on digitized data from published figures, which introduces some uncertainty in extracted rates. Second, single-exponential fits were assumed throughout; while widely used, this simplification may not capture all many-body or strongly coupled dynamics. Third, normalization conventions differ across experiments (e.g., per-pulse versus continuous interrogation), making direct numerical comparison of values difficult. Finally, the current evidence remains retrospective; definitive confirmation requires prospective experiments where detector timing is explicitly controlled.

7.6. Outlook

If future tests confirm linear scaling of with , then detector timing must be recognized as a fundamental variable in collapse dynamics. This would mark a shift from viewing collapse as instantaneous and environment-only to understanding it as relational, shaped by how systems are interrogated. The ability to tune collapse through -engineering would add a new axis of control in quantum technologies and provide a unifying framework for Zeno, anti-Zeno, and baseline decoherence.

If, however, careful -sweeps fail to reveal the predicted linearity, the theorem is refuted and collapse remains attributable to the environment alone. Either outcome advances the field: by placing collapse under direct experimental control, the question becomes falsifiable, and speculation gives way to testable structure.

Appendix A Technical Derivations

This appendix provides mathematical details supporting the main text. The aim is not to propose new microscopic mechanisms but to show how the scaling arises naturally when detector resolution is modeled explicitly.

Appendix A.1. Lindblad Formulation

Consider a system density operator

evolving under a Lindblad master equation,

If the detector couples through a coarse-grained observable sampled at intervals

, the corresponding Lindblad operators acquire a

-dependent normalization. To leading order, this produces an additional dephasing channel whose rate scales as

. The effective collapse rate is then

with

from environmental channels and

determined by detector coupling strength.

Appendix A.2. Path-Integral Picture

In the Feynman path-integral framework, decoherence arises when phase coherence is lost across interfering histories. Introducing finite detector resolution is equivalent to averaging over histories shorter than

. This averaging eliminates fine-grained phase correlations and introduces an effective decay channel. The suppression factor takes the form

recovering the same

scaling identified in the main theorem.

Appendix A.3. Filter-Function Intuition

An intuitive way to understand the law is through filter functions. Any detector imposes a temporal filter that weights environmental noise at frequency . Shorter corresponds to broader frequency response, allowing more noise modes to couple to the system. Expanding the overlap integral between and the noise spectrum shows that the leading-order change in the effective rate is linear in , with coefficient set by the overlap amplitude.

Together, these derivations demonstrate that the linear detector contribution is not an ad hoc assumption but a natural outcome of modeling finite temporal resolution in multiple formalisms.

References

- Misra B, Sudarshan ECG. The Zeno’s paradox in quantum theory. J Math Phys 1977, 18, 756–763. [CrossRef]

- Itano WM, Heinzen DJ, Bollinger JJ, Wineland DJ. Quantum Zeno effect. Phys Rev A 1990, 41, 2295–2300.

- Facchi P, Pascazio S. Quantum Zeno dynamics: Mathematical and physical aspects. J Phys A 2002, 41, 493001.

- Leggett AJ, Garg A. Quantum mechanics versus macroscopic realism: Is the flux there when nobody looks? Phys Rev Lett 1985, 54, 857–860. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emary C, Lambert N, Nori F. Leggett–Garg inequalities. Rep Prog Phys 2014, 77, 016001. [CrossRef]

- Ghirardi GC, Rimini A, Weber T. Unified dynamics for microscopic and macroscopic systems. Phys Rev D 1986, 34, 470–491. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diosi, L. Models for universal reduction of macroscopic quantum fluctuations. Phys Rev A 1989, 40, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penrose, R. On gravity’s role in quantum state reduction. Gen Relativ Gravit 1996, 28, 581–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi A, Lochan K, Satin S, Singh TP, Ulbricht H. Models of wave-function collapse, underlying theories, and experimental tests. Rev Mod Phys 2013, 85, 471–527. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, S. On quantum theory of transport phenomena. Prog Theor Phys 1958, 20, 948–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwanzig, R. Ensemble method in the theory of irreversibility. J Chem Phys 1960, 33, 1338–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblad, G. On the generators of quantum dynamical semigroups. Commun Math Phys 1976, 48, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakuyanagi K, Saito S, Nakano H, et al. Observation of quantum Zeno effect in a superconducting flux qubit. New J Phys 2015, 17, 063035. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez GA, Suter D. Measuring the spectrum of colored noise by dynamical decoupling. Phys Rev Lett 2010, 104, 230403.

- Streed EW, Mun J, Boyd M, Campbell GK, Medley P, Ketterle W, Pritchard DE. Continuous and pulsed quantum Zeno effect. Phys Rev Lett 2006, 97, 260402.

- Verma V, Lita AE, Stevens MJ, Nam SW. Superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors. Appl Phys Lett 2014, 105, 022602.

- Korzh B, Zhao Q-Y, Allmaras J, et al. Demonstration of sub-3 ps jitter in a superconducting nanowire single-photon detector. Nat Photonics 2020, 14, 250–255. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).