Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

2.2. Method

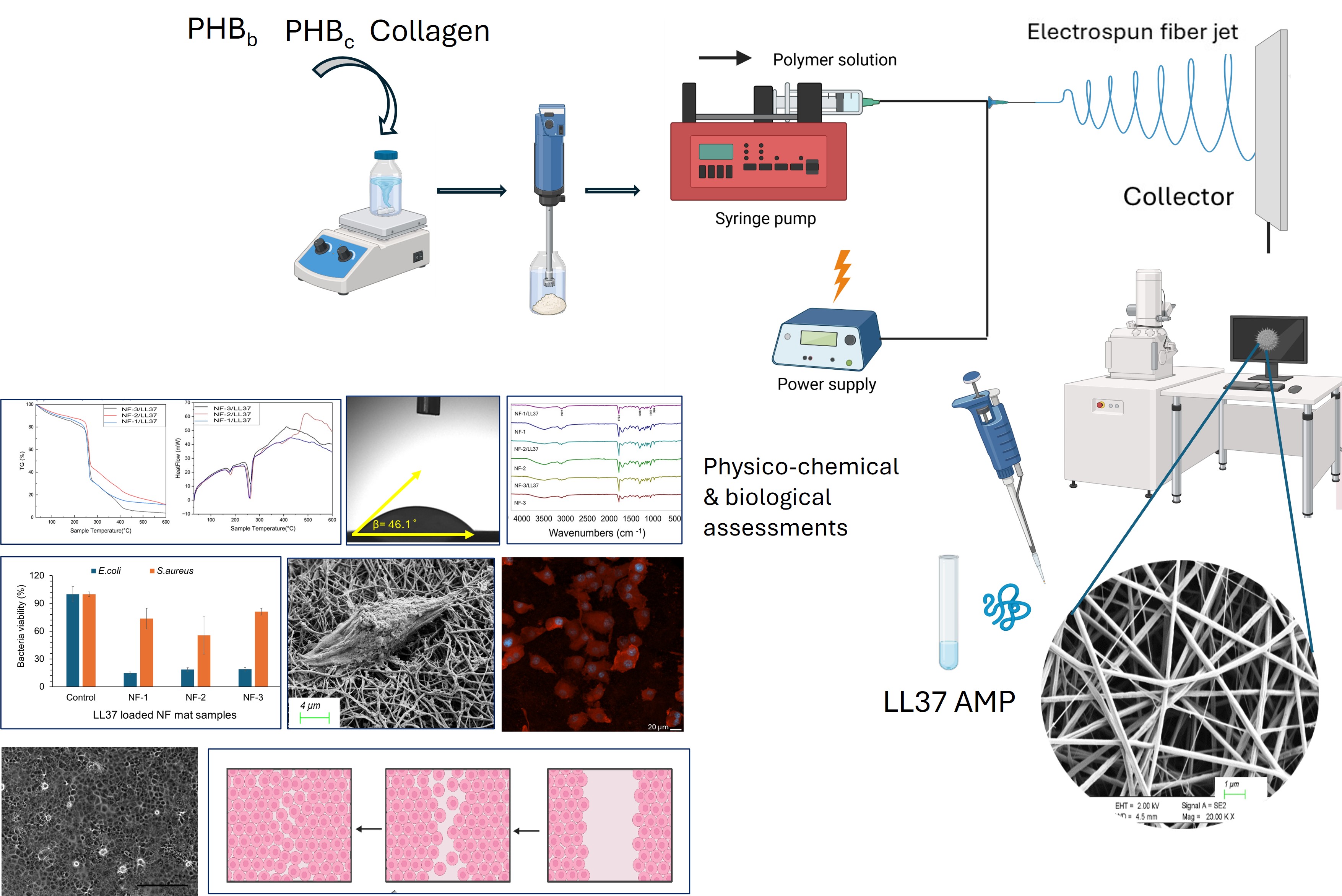

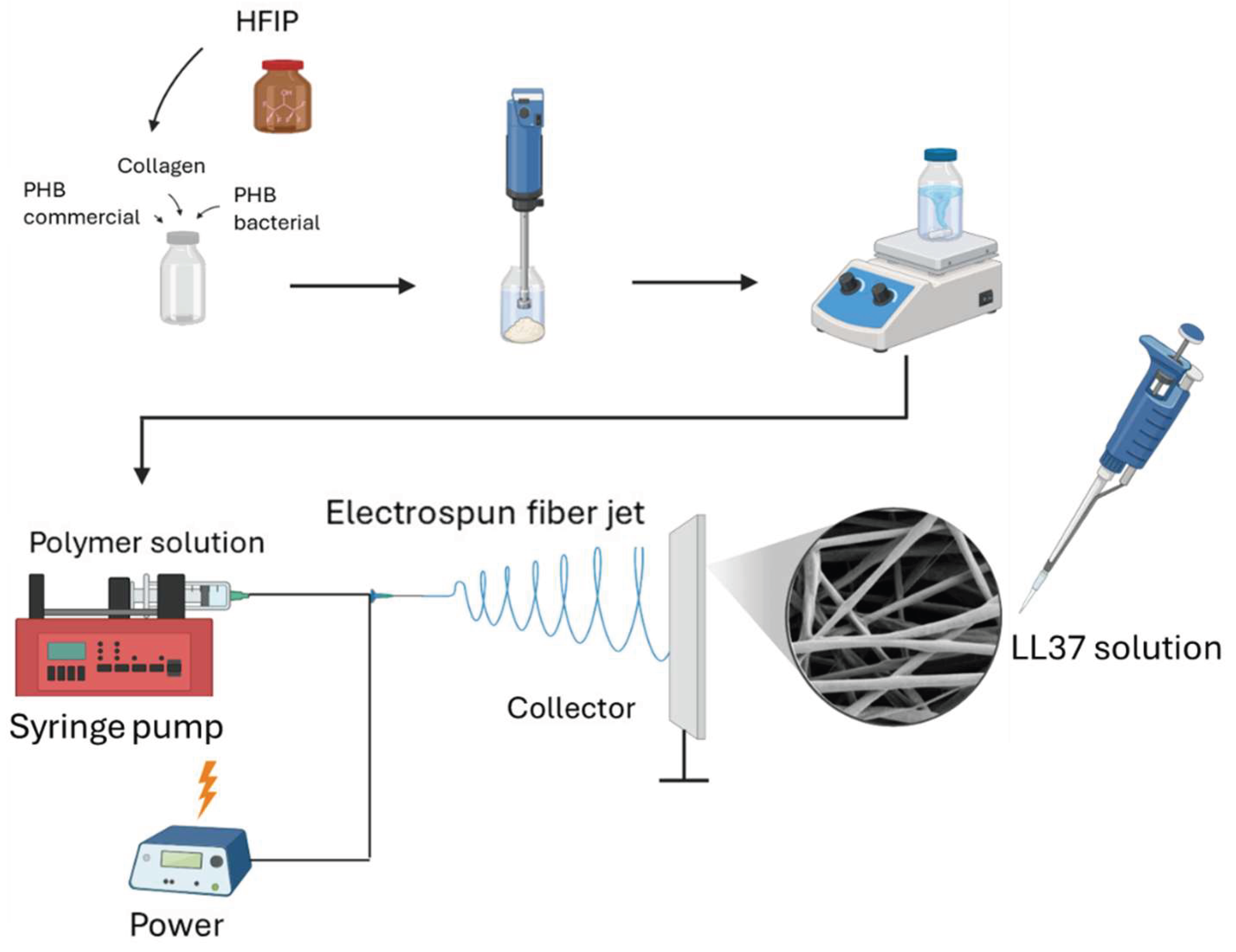

2.2.1. Development of LL37-loaded PHB/Col Nanofiber Mats

2.2.2. Physicochemical Characterization of LL37/PHB/Col Nanofiber Mats

2.2.3. Degradation of Nanofibers

2.2.4. In Vitro Biocompatibility and Cell Attachment on Nanofibers

2.2.5. Measurement of 2D Wound Healing Activity by Scratch Assay

2.2.6. Evaluation of Antibacterial Activity of Nanofiber Mats

3. Results and Discussion

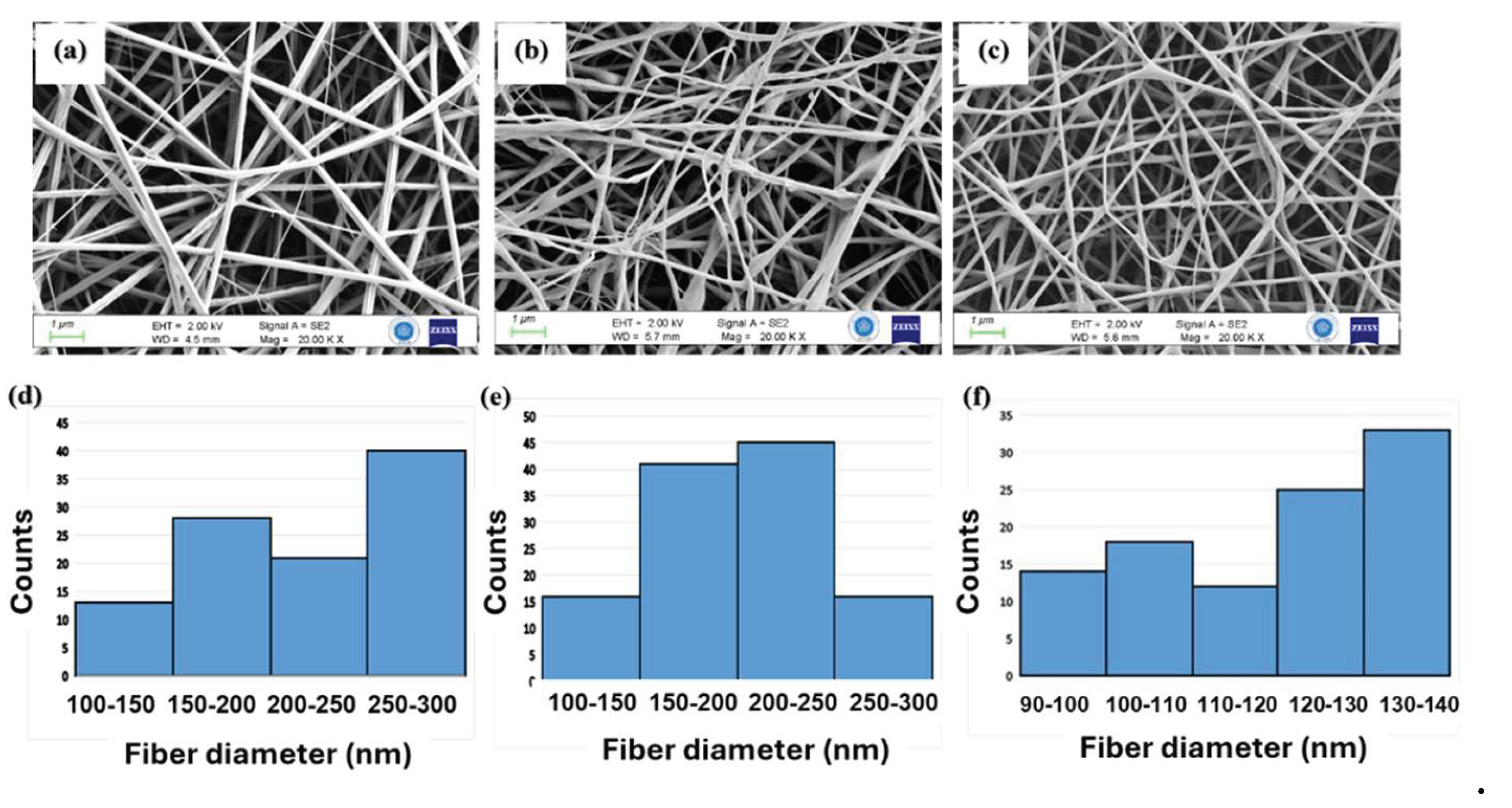

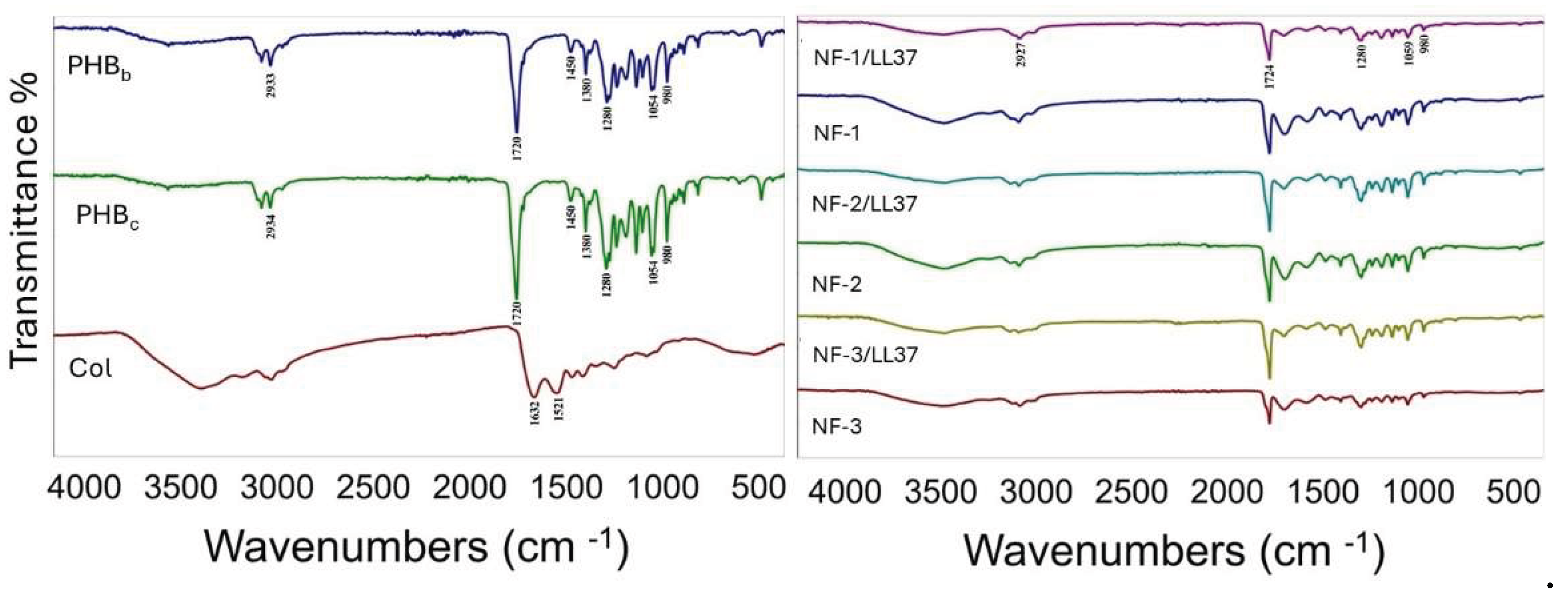

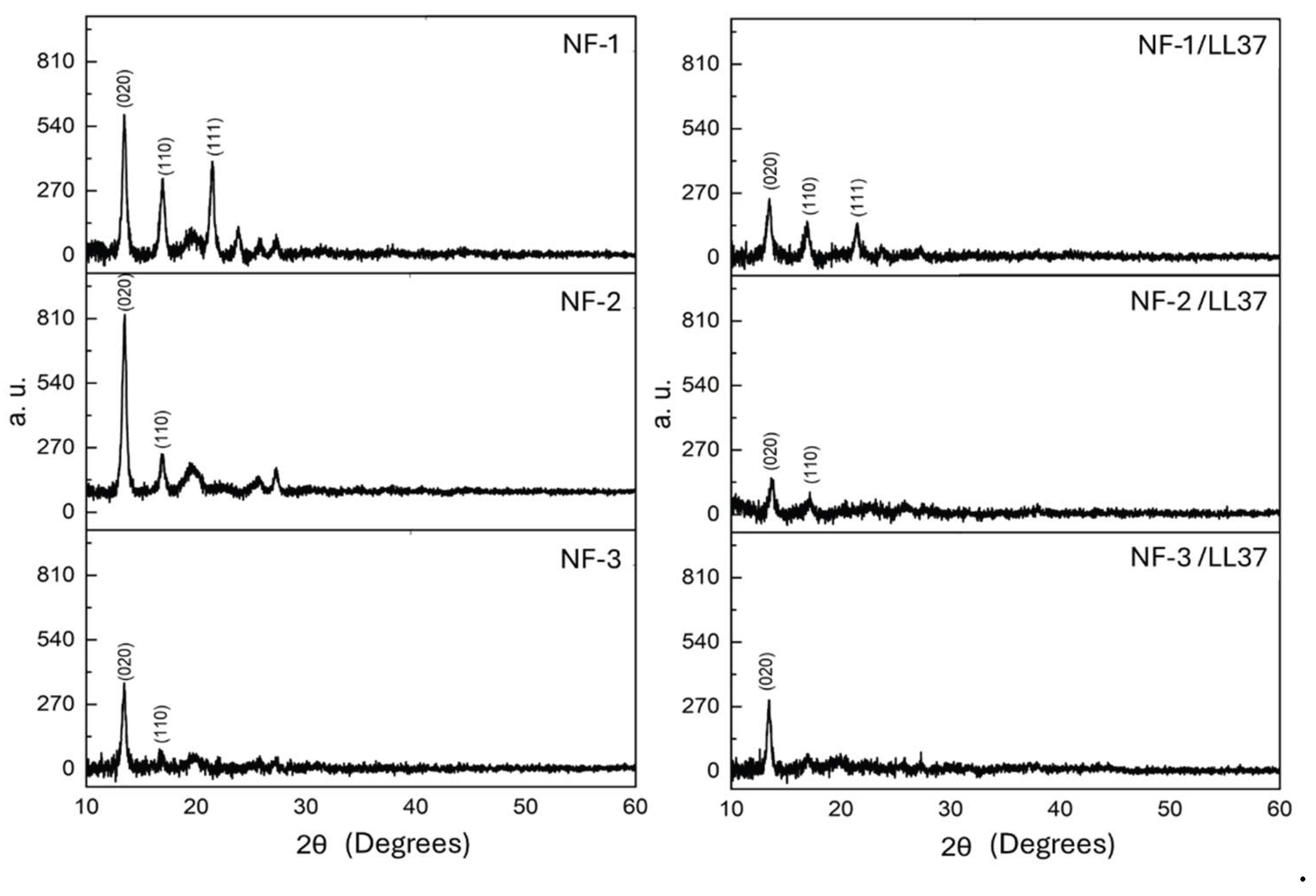

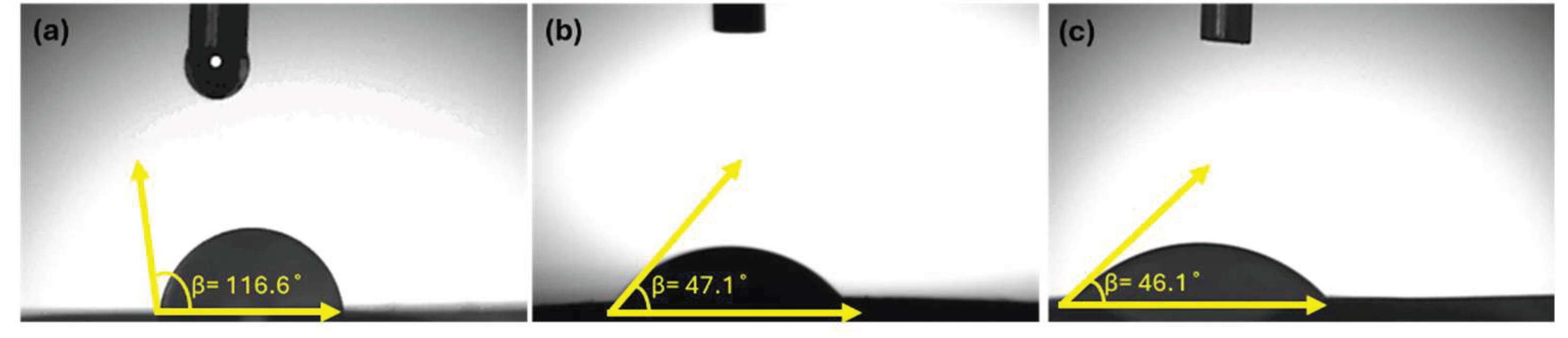

3.1. Physicochemical Characteristics of PHB/Col/LL37 Nanofiber Mats

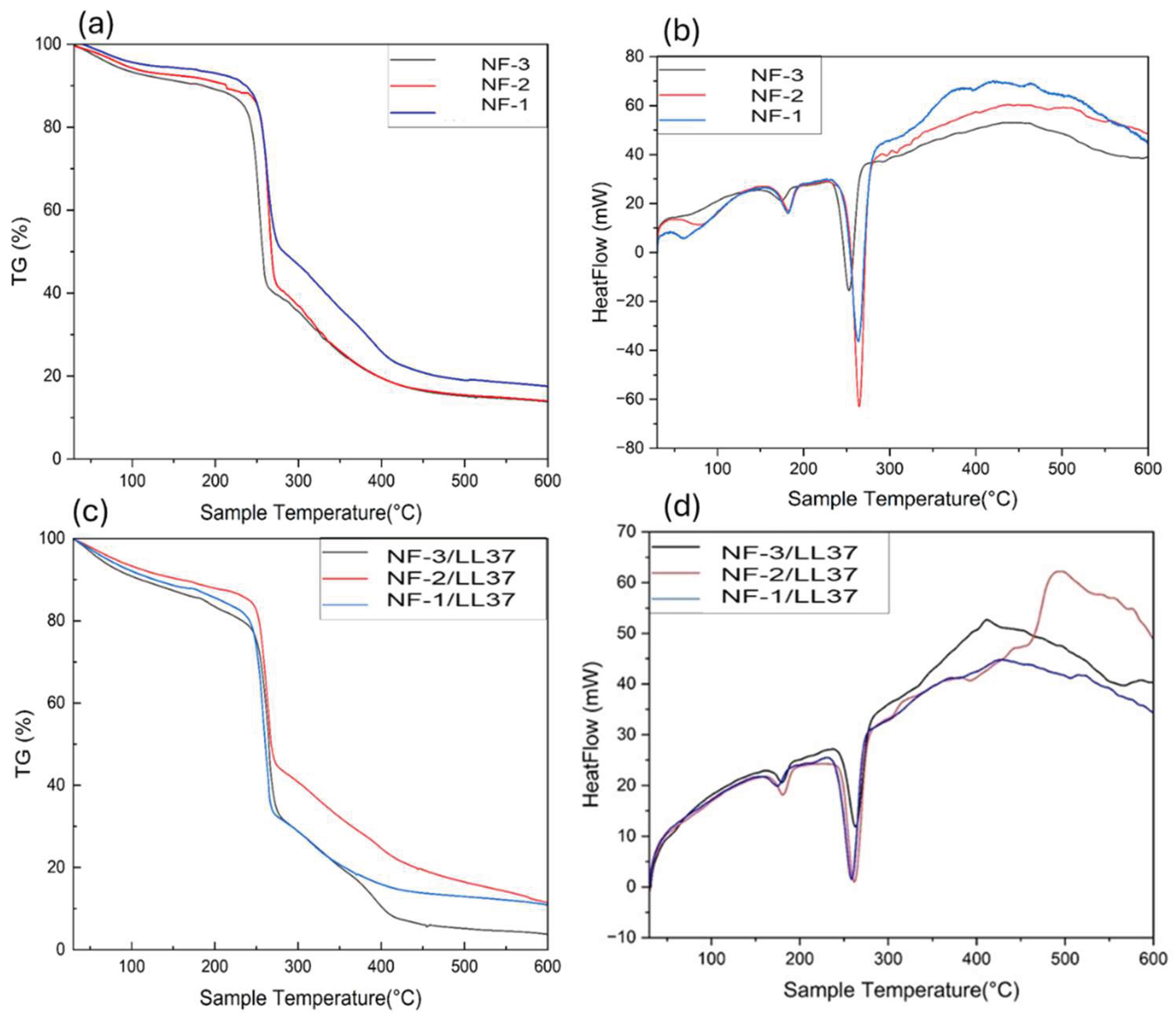

3.2. Degradation of Nanofibers

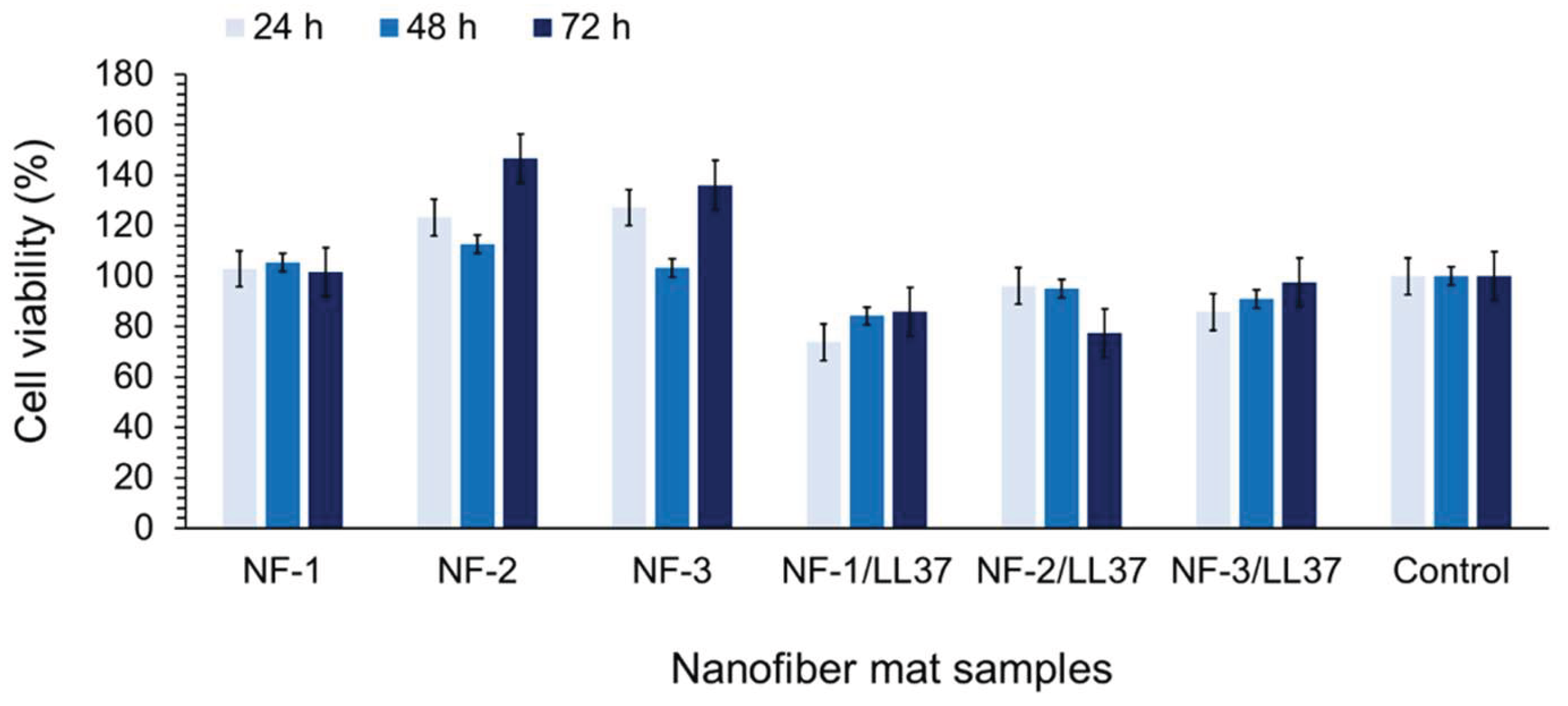

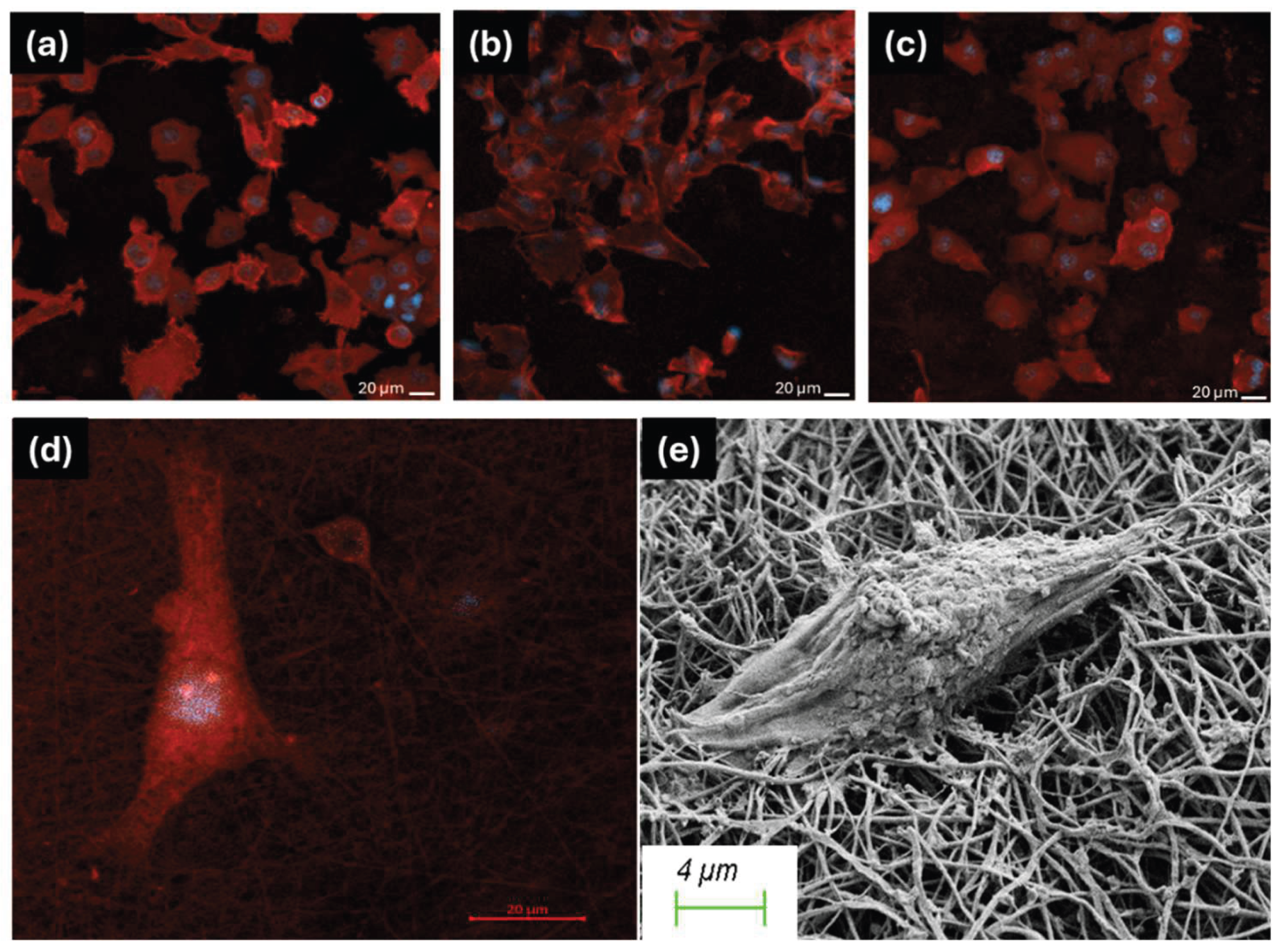

3.3. Biocompatibility and Cell Attachment on Nanofibers

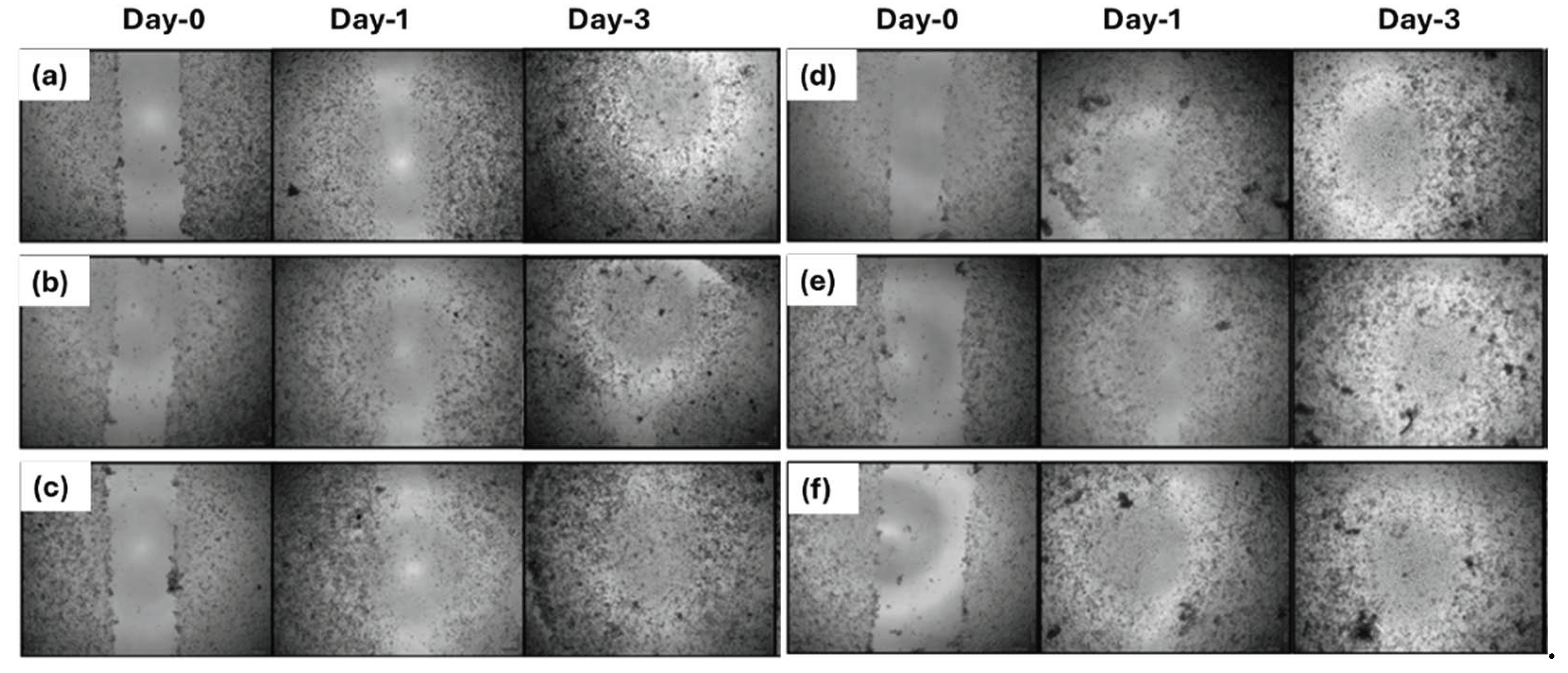

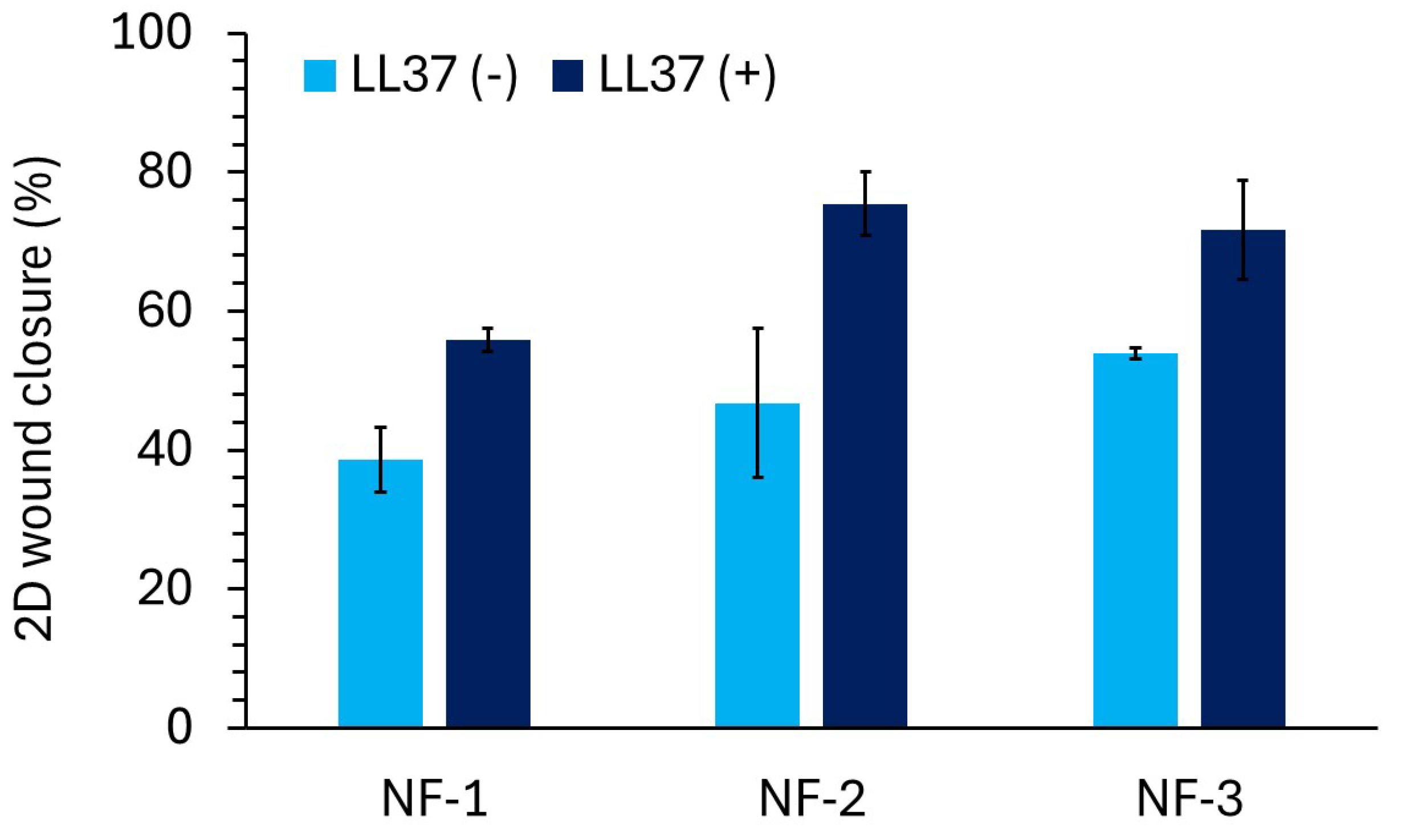

3.4. D Wound Healing Activity of Nanofiber Mats

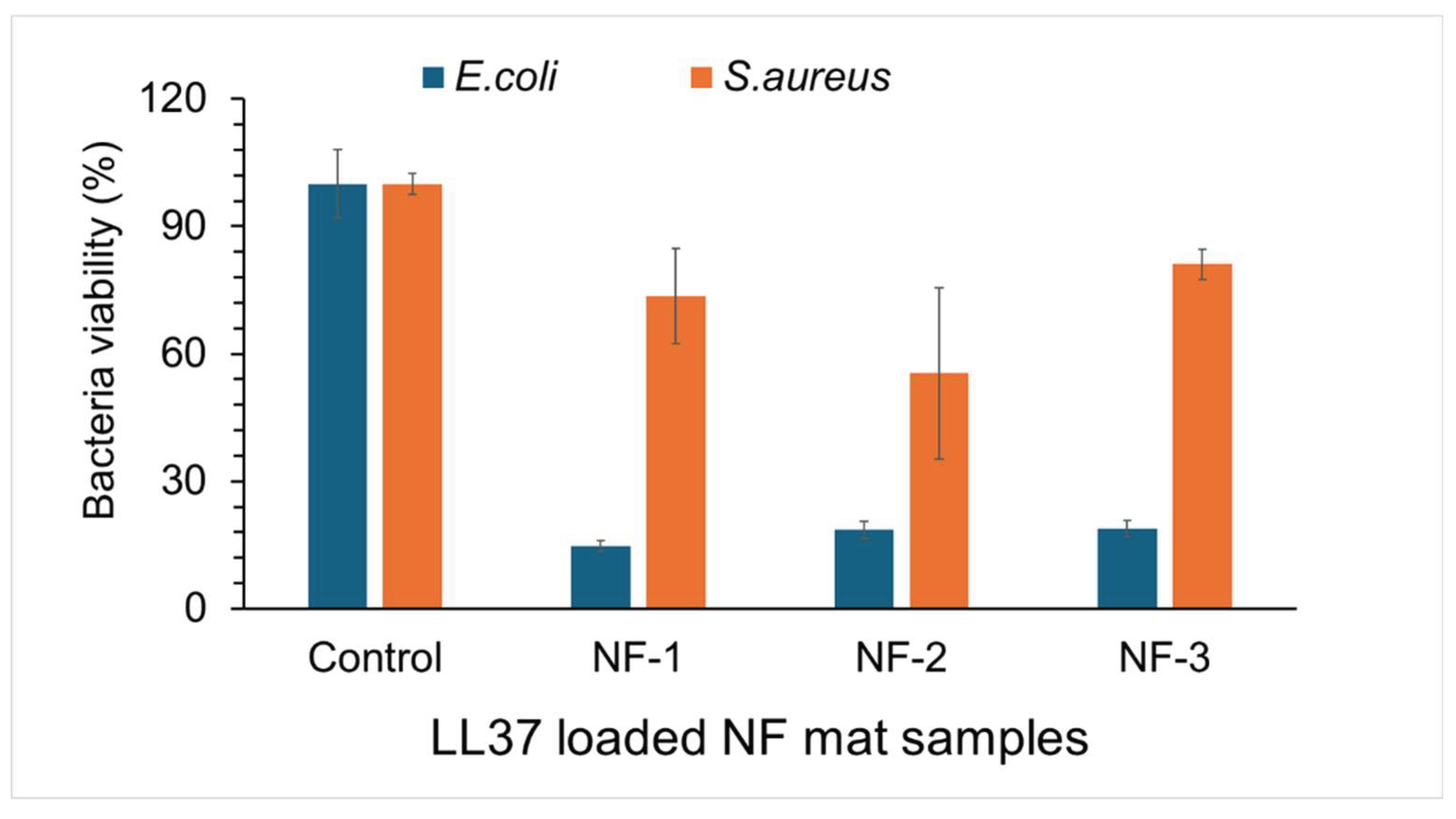

3.5. Antibacterial Activity of Nanofiber Mats

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- J. C. C. Yeo, J. K. Muiruri, W. Thitsartarn, Z. Li, and C. He, “Recent advances in the development of biodegradable PHB-based toughening materials: Approaches, advantages and applications”, Materials Science and Engineering: C, 92, 1092-1116, 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Zarrintaj et al., “Biopolymer-based composites for tissue engineering applications: A basis for future opportunities”, Composites Part B: Engineering, 258, 110701, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Borda, F. E. Macquhae, and R. S. Kirsner, “Wound Dressings: A Comprehensive Review”, Curr Derm Rep, 5, 4, 287-297, 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. Martin and R. Nunan, “Cellular and molecular mechanisms of repair in acute and chronic wound healing”, British Journal of Dermatology, 173, 2, 370-378, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y.-H. Wei, W.-C. Chen, H.-S. Wu, and O.-M. Janarthanan, “Biodegradable and Biocompatible Biomaterial, Polyhydroxybutyrate, Produced by an Indigenous Vibrio sp. BM-1 Isolated from Marine Environment”, Marine Drugs, 9, 4, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Roohi, M. R. Zaheer, and M. Kuddus, “PHB (poly-β-hydroxybutyrate) and its enzymatic degradation”, Polymers for Advanced Technologies, 29, 1, 30-40, 2018. [CrossRef]

- X. Ma et al., “A Review of Antimicrobial Peptides: Structure, Mechanism of Action, and Molecular Optimization Strategies”, Fermentation, 10, 11, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Ramos et al., “Wound healing activity of the human antimicrobial peptide LL37”, Peptides, 32, 7, 1469-1476, 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. Salvatore et al. , “Potential of Electrospun Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate)/Collagen Blends for Tissue Engineering Applications”, Journal of Healthcare Engineering, 2018, 1, 6573947, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. P. Prabhakaran, E. Vatankhah, and S. Ramakrishna, “Electrospun aligned PHBV/collagen nanofibers as substrates for nerve tissue engineering”, Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 110, 10, 2775-2784, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Amir et al., “Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) bioplastic characterization from the isolate Pseudomonas stutzeri PSB1 synthesized using potato peel feedstock to combat solid waste management”, Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, 57, 103097, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Bayram Sarıipek, “Biopolymeric nanofibrous scaffolds of poly(3-hydroxybuthyrate)/chitosan loaded with biogenic silver nanoparticle synthesized using curcumin and their antibacterial activities”, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 256, 128330, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Naderi Gharahgheshlagh et al., “Fabricating modified cotton wound dressing via exopolysaccharide-incorporated marine collagen nanofibers”, Materials Today Communications, 39, 108706, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Li, L. Du, Y. Xiao, L. Fan, Q. Li, and C. Y. Cao, “Multi-active phlorotannins boost antimicrobial peptide LL-37 to promote periodontal tissue regeneration in diabetic periodontitis”, Materials Today Bio, 31, 101535, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Mohammadalipour, T. Behzad, S. Karbasi, M. Babaei Khorzoghi, and Z. Mohammadalipour, “Osteogenic potential of PHB-lignin/cellulose nanofiber electrospun scaffold as a novel bone regeneration construct”, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 250, 126076, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Fahimirad, M. Khaki, E. Ghaznavi-Rad, and H. Abtahi, “Investigation of a novel bilayered PCL/PVA electrospun nanofiber incorporated Chitosan-LL37 and Chitosan-VEGF nanoparticles as an advanced antibacterial cell growth-promoting wound dressing”, International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 661, 124341, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xu et al., “Fighting bacteria with bacteria: A biocompatible living hydrogel patch for combating bacterial infections and promoting wound healing”, Acta Biomaterialia, 181, 176-187, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Long et al., “Injectable multifunctional hyaluronic acid/methylcellulose hydrogels for chronic wounds repairing”, Carbohydrate Polymers, 289, 119456, 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Bechinger and S.-U. Gorr, “Antimicrobial Peptides: Mechanisms of Action and Resistance”, J Dent Res, 96, 3, 254-260, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu et al., “Thermal-responsive microgels incorporated PVA composite hydrogels: Integration of two-stage drug release and enhanced self-healing ability for chronic wound treatment”, Chemical Engineering Journal, 506, 159813, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang et al., “Thermosensitive-based synergistic antibacterial effects of novel LL37@ZPF-2 loaded poloxamer hydrogel for infected skin wound healing”, International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 670, 125210, 2025. [CrossRef]

| Nanofiber types | PHB(b)*/PHB(c)** (w/w) | Collagen (w) | Solvent |

|---|---|---|---|

| NF-1 : %0 bacterial PHB/Collagen | 0 g PHB(b) / 0.2 g PHB(c) | 0.2 g | HFIP |

| NF-2 : %25 bacterial PHB/Collagen | 0.05 g PHB(b) / 0.15 g PHB(c) | 0.2 g | HFIP |

| NF-3 : %50 bacterial PHB/Collagen | 0.1 g PHB(b) / 0.1 g PHB(c) | 0.2 g | HFIP |

| NF-4 : %75 bacterial PHB/Collagen | 0.15 g PHB(b) / 0.05 g PHB(c) | 0.2 g | HFIP |

| NF-5: %100 bacterial PHB/Collagen | 0.2 g PHB(b) / 0 g PHB(c) | 0.2 g | HFIP |

| Functional group | Wavenumbers (cm-1) |

|---|---|

| CH3 | 1380 |

| CH2 | 1450 |

| C-H | 2976-2932 |

| C=O | 1724-1719 |

| C-O | 1280-1275 |

| O-H | 3436 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).