1. Introduction

Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) has been widely acknowledged as a global public health threat, yet there remains a dearth of comprehensive data on the use of antimicrobial agents, the prevalence and spread of resistance, and their potential impact on human health [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Poultry production is a significant contributor to the dissemination of antimicrobial-resistant

E. coli within both the community and the environment [

3,

4,

5]. This is particularly concerning in Zambia, because Poultry production is a major activity in the livestock industry. In 2019, the poultry population in Zambia was estimated at 94 million broilers, 5.8 million layers, and 15 million village chickens (Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock, Livestock and Aquaculture Census Report, 2021) [

6]. The disease burden in Zambia’s poultry sector remains a major challenge, with

Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., and

Escherichia coli being common bacterial pathogens alongside the increasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistance [

7,

8,

9].

Similar to other developing countries, poultry products in Zambia form an indispensable part of the human diet particularly in many households where they serve as an affordable source of animal protein compared to other meat sources [

10]. As such, ensuring the safety and quality of poultry meat is crucial. The increasing disease burden in poultry, coupled with a rise in antimicrobial use, is an essential risk factor associated with the emergence and spread of AMR [

11]. Furthermore, the normal microbiota in poultry, which can carry AMR genes, increases the complexity of the situation [

12].

The pressure to meet the growing consumer demand for poultry products and the desire to maximize profits lead to pressure for farmers to use antimicrobials for disease prevention, treatment, and growth optimization [

13]. However, inappropriate use of antimicrobials in poultry industry, can enhance the development and transmission of antimicrobial-resistant genes and bacteria found in live poultry, on the poultry production premises. Furthermore, non-compliance with withdrawal periods for antimicrobial drugs can lead to elevated levels of antimicrobial residues in chicken meat and eggs, compromising food safety [

14].

The Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), primarily CTX-M enzymes, are increasingly common in

Enterobacteriaceae, particularly

E. coli, leading to serious infections like urinary tract, bloodstream, and intra-abdominal infections [

15,

16]. These infections often require lengthy hospitalization. Treatment options are limited due to multidrug resistance, with carbapenems being the preferred choice. However, clinical data supporting the effectiveness of alternative therapies remains limited [

17].

In response to the global call to combat AMR, Zambia established the Antimicrobial Resistance Coordinating Committee (AMRCC) in 2015, following the World Health Organization’s (WHO) World Health Assembly resolution. In 2016, Zambia established the Antimicrobial Resistance National Action Plan (NAP) as part of its efforts to mitigate the impact of AMR [

18].

This study aimed to generate a comparative assessment of the antimicrobial resistance profiles of E. coli isolates obtained from intensively reared and free-range chickens in selected districts of Zambia. The specific objectives were to determine the carriage of ESBL-producing E. coli in healthy chickens, through phenotypic and genotypic characterization of antimicrobial resistance in these isolates, and to assess the diversity of antimicrobial usage at both the farm and household levels.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Location, Sampling, and Culture of Bacteria

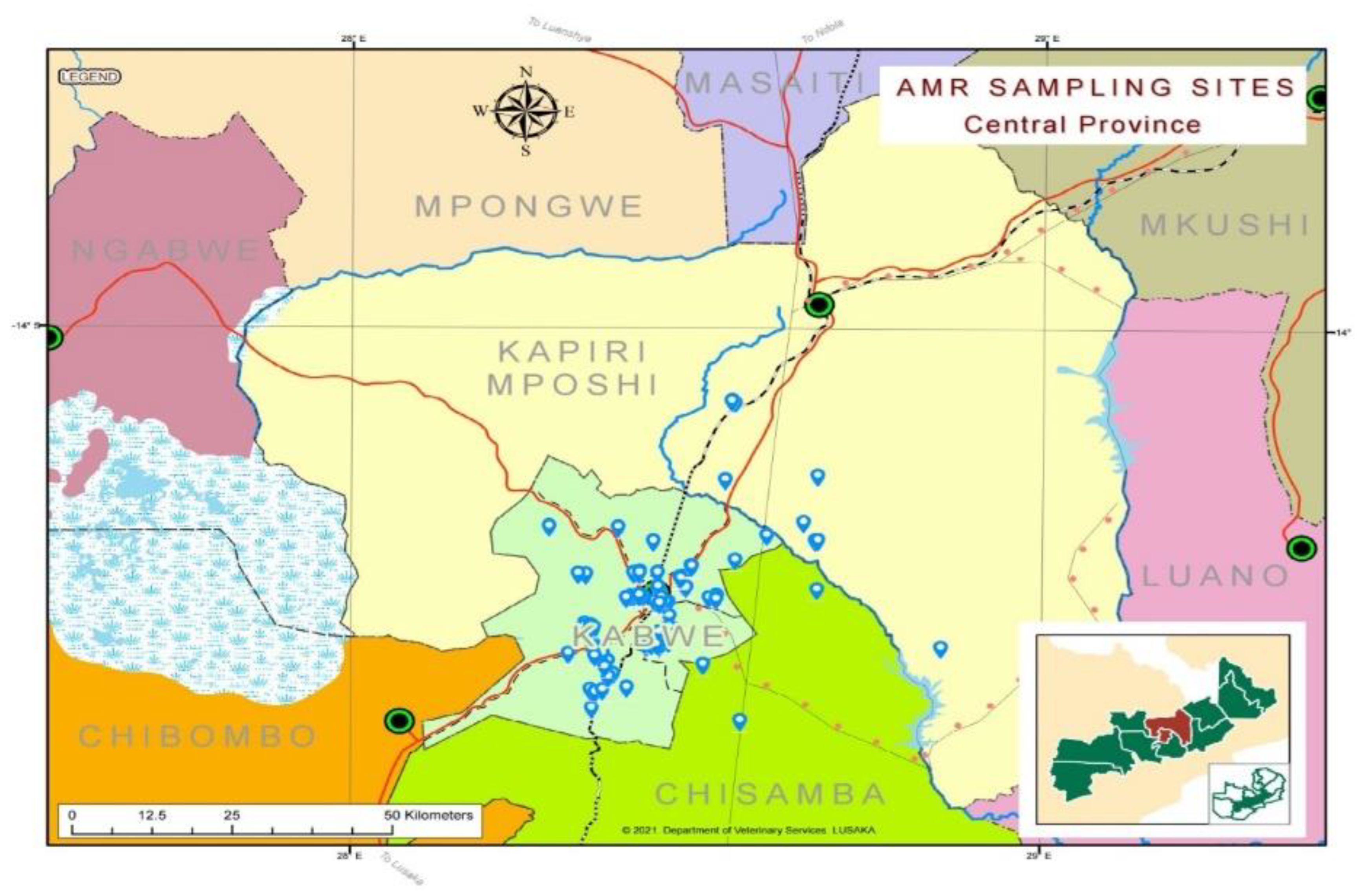

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in Kapiri Mposhi and Kabwe Districts of Zambia. In this study, Kapiri Mposhi accounted for two (2) veterinary camps, while Kabwe accounted for five (5) veterinary camps (

Figure 1). The two districts are located in the Central Province of Zambia. In total, Kabwe District has five veterinary camps, namely: Munga North, Munga West, Mpima, Waya, and Munyama, while the veterinary camps in Kapiri Mposhi district - thirteen in total - are Mulungushi, Kakwelesa, Likumbi, Chibwe, Mukonchi, Lunchu, Nkole, Kapiri Mposhi Central, Luanshimba, Musosoloke, Chipepo, Kato, and Chilumba. Each veterinary camp was divided into villages that were clustered and then systematically selected to ensure strong, representative geographical coverage.

Table 1 shows the distribution of survey respondents by district level (n = 112). The results indicate that a significant majority of respondents were from Kabwe (n = 77, 69.4%; 95% CI: 60.7–78.1), while a smaller proportion were from Kapiri Mposhi (n = 34, 30.6%; 95% CI: 21.9–39.3).

Table 1.

Sampling proportions according to STRATA 1 (main study area).

Table 1.

Sampling proportions according to STRATA 1 (main study area).

| STRATA 1 [District Level] |

(n = 112 |

% Proportion |

(95% CI) |

| Kabwe |

77 |

68.8 |

(59.8% – 77.8%) |

| Kapiri Mposhi |

35 |

31.3 |

(22.8% – 39.8%) |

Table 2 demonstrates that, considering both STRATA 1 and STRATA 2, the distribution of veterinary camps by district is detailed in

Table 4. Kabwe provided five veterinary camps, yielding a total of 77 samples, while Kapiri Mposhi offered two veterinary camps that produced 34 samples.

Table 2.

Tabulation of sampling by strata, where STRATA 2 is taken into consideration along with STRATA 1.

Table 2.

Tabulation of sampling by strata, where STRATA 2 is taken into consideration along with STRATA 1.

| Kabwe (n = 77) |

Kapiri Mposhi (n = 35) |

| STRATA 2 (Veterinary Camps sampled in Kabwe District) |

N |

STRATA 2 (Veterinary Camps sampled in Kapiri Mposhi District) |

N |

| Munga North |

1 |

Chilumba |

13 |

| Waya |

17 |

Luanshimba |

22 |

| Mpima |

12 |

|

|

| Kabwe Central |

32 |

|

|

| Munyama |

15 |

|

|

STRATA 2: The second level of sampling was conducted at the veterinary camp level. Together, the two districts contributed a total of seven independent sampling strata.

Table 2 above outlines the secondary sampling strata at the camp level in detail. Most farmers sampled at the camp level were from the Kabwe Central veterinary camp, in Kabwe district (n = 32), representing a 28.9% sample proportion (at a 95% CI: 20.3%–37.4%), while Munga North, in Kabwe district contributed only one farmer.

The study population comprised intensively reared and free-range animals ranging from 10 to 500. The sampled chickens were of all ages, with age estimation done as previously described [

19,

20]. The sample size for this study was calculated based on established statistical methods suitable for comparing proportions between groups [

21].

The samples were collected from both intensively reared chickens and free-range chickens, as described by De Carli et al. [

22]. Freshly voided faecal samples were collected from apparently healthy chickens. The samples were collected from different chickens. The collected fecal samples were combined into pooled batches, each consisting of ten individual samples [

23].

The pooled samples were then placed in cooler boxes under ice and transported to the microbiology laboratory at the Para-Clinical Studies Department, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Zambia. Upon arrival, the samples were immediately stored at -20 °C until processing, which occurred within 24 hours of collection.

The pooled samples were homogenized by repeated bead beating (RBB) [

24]. A portion (1.0 g) of each homogenized pooled sample was collected and placed in a 9-ml tube containing Luria-Bertani (LB) broth for enrichment. After enrichment, a loopful (approximately 100 µL) of inoculum from the LB broth was streaked onto MacConkey agar supplemented with 2 mg/L of Cefotaxime, E and O Laboratories Ltd. The inoculated plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight, where a single colony of the test organisms was identified as

E. coli as described by [

25]. The colonies were further subjected to the following tests: erythritol, glucose, glycerol, and lactose as previously described [

26,

27].

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of

E. coli isolates was performed using the Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar (Becton, Dickinson and Company, MD, USA) and interpreted according to the Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) guidelines (Becton, Dickinson and Company, MD, USA) [

28].

The following was the panel of antibiotics used in the study: Co-trimoxazole (Sulpha/Trimethoprim) (25 µg), Amoxyclav® (30 µg), Chloramphenicol (30 µg), Gentamicin (10 µg), Tetracycline (30 µg), Ciprofloxacin (5 µg), Streptomycin (10 µg), Nalidixic acid (30 µg), Ceftazidime (30 µg), Norfloxacin (10 µg), Cefotaxime (30 µg), and Clavulanic acid (30 µg). Further, ESBL production was determined using the double-disk synergy test following CLSI (2013) guidelines (

Table 1). ESBL-producing strains of

E. coli were initially identified by a minimum increase of 5 mm in the zone of inhibition around cefotaxime/clavulanate and ceftazidime/clavulanate disks compared to disks without clavulanic acid [

29].

Molecular Detection of Antibiotic Resistance Genes

The

E. coli isolates were subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for confirmation of resistance genes – TEM (Temoniera), SHV (Sulphydryl Variable), and CTX-M (Cefotaxime-Munich) – using primers (

Table 1) previously employed by other researchers (Ranjan et al. 2015). The PCR (Finnzymes Oy, Finland) was performed in a total reaction volume of 16.5 µL consisting of 5.0

μL Phusion master mix, 13.0 µL of sterile distilled (nuclease-free) water, 0.5 µL of Forward primer and 0.5 µL Reverse primer, and 1.0 µL of bacterial DNA template. The PCR was performed using the rapid cycle DNA amplification method comprising an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 10 seconds, followed by 40 cycles of template denaturation at 40 °C for 0.3 seconds, primer annealing at 57 °C for 1 second, and final extension at 72 °C for 10 seconds [

30]. The PCR products were analyzed in 1% agarose gel containing 25 μg/ml of ethidium bromide in tris-EDTA buffer, and the gel was photographed under an ultraviolet illuminator using a gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, USA). Further, a 100 bp DNA ladder was included in each run [

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4].

Table 3.

Primers used in the multiplex PCR amplification.

Table 3.

Primers used in the multiplex PCR amplification.

| Primer name |

Sequence (5’-3’ direction) |

Temperature in °C |

Amplicon Size in bp |

| CTX-M Fw |

CGATGTGCAGTACCAGTAA |

55 |

585 |

| CTX-M Rv |

TTAGTGACCAGAATCAGCGG |

|

|

| TEM Fw |

ATAAAATTCTTGAAGACGAAA |

50 |

1080 |

| TEM Rv |

GACAGTTACCAATGCTTAATC |

|

|

| SHV Fw |

GGGTTATTCTTATTTGTCGC |

55 |

930 |

| SHV Rv |

TTAGCGTTGCCAGTGCTC |

|

|

The sequences are provided in the 5’-3’ direction, with the optimal annealing temperature in degrees Celsius (°C) and the expected size of the amplicon in base pairs (bp) for each gene target.

3. Results

In this study, 112 faecal samples were collected from free-range and intensively reared chickens. In each mode of rearing chickens, 56 samples were collected. The samples were collected from seven (7) veterinary camps, (

Table 2). Of the samples collected, 11.61% (n=13/112) of the samples were positive for ESBL-producing

E. coli, with 5.35% from free-range and 6.25% from intensively reared.

Table 4.

Number of samples that tested positive from veterinary camps.

Table 4.

Number of samples that tested positive from veterinary camps.

| Veterinary Camp |

(n = 112) |

Samples containing ESBL E coli in Intensively-reared chickens |

Samples containing ESBL E coli in Free-range chickens |

| Munga North (Kabwe) |

01 |

0 |

0 |

| Waya (Kabwe) |

17 |

1 |

0 |

| Mpima (Kabwe) |

12 |

2 |

1 |

| Chilumba (Kapiri Mposhi) |

13 |

1 |

1 |

| Kabwe Central (Kabwe) |

32 |

2 |

0 |

| Luanshimba (Kapiri Mposhi) |

22 |

1 |

2 |

| Munyama (Kabwe) |

15 |

0 |

2 |

| |

112 |

7 |

6 |

The identified

E. coli isolates were then subjected to antibiotic susceptibility tests, and the results are shown in

Table 5. The isolates exhibited varying degrees of resistance indicated by 'R' and measured in millimeters (mm) of the zone of inhibition. Each isolate was assessed against a panel of 11 antibiotics: SXT, CL, GEN, TET, CIP, STR, NAL, TAZ, NOR, CTX, and CTXC. Notably, many isolates exhibited resistance to multiple antibiotics as evidenced by low zones of inhibition. The susceptibility varied among isolates, with some exhibiting notable sensitivity to certain antibiotics.

Table 5.

Zones of inhibition (mm) of Isolates to different antibiotics.

Table 5.

Zones of inhibition (mm) of Isolates to different antibiotics.

| Isolates |

Zone of inhibition (mm) |

| |

SXT |

CL |

GEN |

TET |

CIP |

STR |

NAL |

TAZ |

NOR |

CTX |

CTXC |

| 02 |

6R*

|

6R

|

20 |

6 R

|

24 |

10R

|

6R

|

21 |

22 |

12R

|

25 |

| 04 |

23 |

20 |

20 |

6R

|

35 |

9R

|

6R

|

25 |

9R

|

12R

|

23 |

| 05 |

6R

|

6R

|

10R

|

6R

|

12R

|

6R

|

23 |

22 |

36 |

15R

|

28 |

| 06 |

6R

|

6R

|

10R

|

6R

|

40 |

10R

|

25 |

25 |

40 |

16R

|

21 |

| 10 |

6R

|

16 |

7R

|

6R

|

40 |

6R

|

20 |

15R

|

36 |

15R

|

18 |

| 15 |

27 |

6R

|

20 |

7R

|

30 |

13 |

25 |

15R

|

32 |

9R

|

20 |

| 16 |

6R

|

20 |

21 |

6R

|

20 |

9R

|

21 |

16R

|

27 |

8R

|

19 |

| 17 |

6R

|

6R

|

20 |

6R

|

21R

|

10 |

6R

|

18 |

21 |

12R

|

23.5 |

| 19 |

6R

|

6R

|

22 |

6R

|

25 |

7R

|

19 |

15R

|

22 |

8R

|

19 |

| 20 |

6R

|

6R

|

8R

|

6R

|

32 |

6R

|

23 |

13R

|

30 |

10R

|

23 |

| 21 |

6R

|

19 |

18 |

6R

|

26 |

7R

|

21 |

12R

|

28 |

16R

|

17 |

| 22 |

20 |

6R

|

20 |

8R

|

36 |

10.5R

|

26 |

25 |

35 |

14R

|

22 |

| 23 |

16 |

17 |

17 |

6R

|

21R

|

6R

|

6R

|

17R

|

20 |

8R

|

21 |

The antibiotic susceptibility profiles of various E. coli isolates revealed considerable variability in resistance among the isolates, with resistance noted particularly against sulfamethoxazole (SXT), chloramphenicol (CL), tetracycline (TET), and ciprofloxacin (CIP). Notably, some isolates demonstrated significant sensitivity to gentamicin (GEN), piperacillin-tazobactam (TAZ), cefotaxime (CTX), and ceftriaxone (CTXC), while other antibiotics showed a substantial level of resistance.

The data (

Table 6) on antibiotic resistance in

E. coli isolates. Column 1 lists the number of antibiotics tested. Column 2 indicates the count of resistant

E. coli isolates against each antibiotic combination. Column 3 displays the proportion of resistant isolates expressed as a percentage, reflecting the prevalence of resistance among the tested strains.

3.1. Analysis of 112 Samples Revealed the Prevalence of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL) Genes

A total of 13 samples (11.61%) were confirmed as ESBL producers, primarily attributed to the presence of the CTX-M gene, highlighting the occurrence of antibiotic resistance within this E. coli population. Conversely, 99 samples (88.39%) lacked any of the tested ESBL genes, suggesting potential diversity in resistance mechanisms across different E. coli strains. The most frequently detected ESBL gene was CTX-M, present in 13 samples, representing 11.61% of the total population. The SHV gene was detected in only one sample, accounting for 0.01% of the population. The TEM gene was identified in four isolates (3.57%) and was also found in combination with CTX-M and SHV in one sample each. Combinations of CTX-M and TEM were detected in four samples, while combinations involving SHV were observed in only one sample. These findings indicate that CTX-M is the predominant ESBL gene among the analysed samples, while SHV and TEM are less common.

3.2. Agarose Gel Electrophoresis from Clinical Isolates

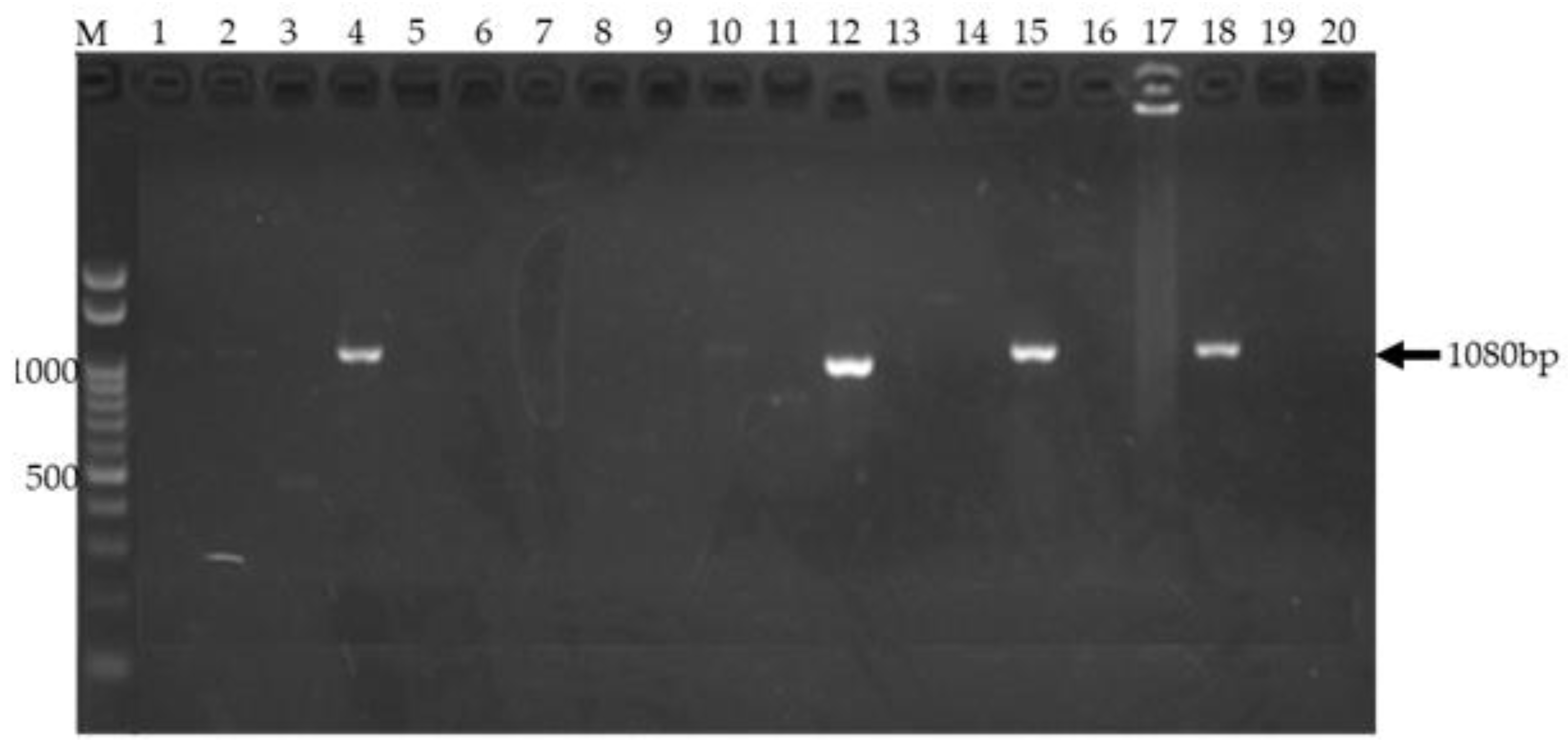

Agarose gel electrophoresis of amplified TEM gene from clinical isolates.

Figure 2 shows a 1% agarose gel used to visualize PCR products amplified from clinical isolates. Lane M contains the Invitrogen 100 bp DNA ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with bands at 100 bp intervals, including a bright band at 1500 bp, serving as a molecular weight marker. Successful amplification of the 1080 bp

TEM gene was observed in lanes 4, 12, 15 and 18 representing isolates 10, 16, 20, and 21 respectively. These lanes display a distinct band migrating at approximately 1080 bp, consistent with the expected size of the amplified target gene. The presence of these bands indicates the presence of the

TEM gene in the corresponding samples. The absence of bands in other lanes suggests the absence of the target gene or unsuccessful amplification in those samples (data not shown). The results validate the successful amplification of the

TEM gene using the optimized PCR protocol.

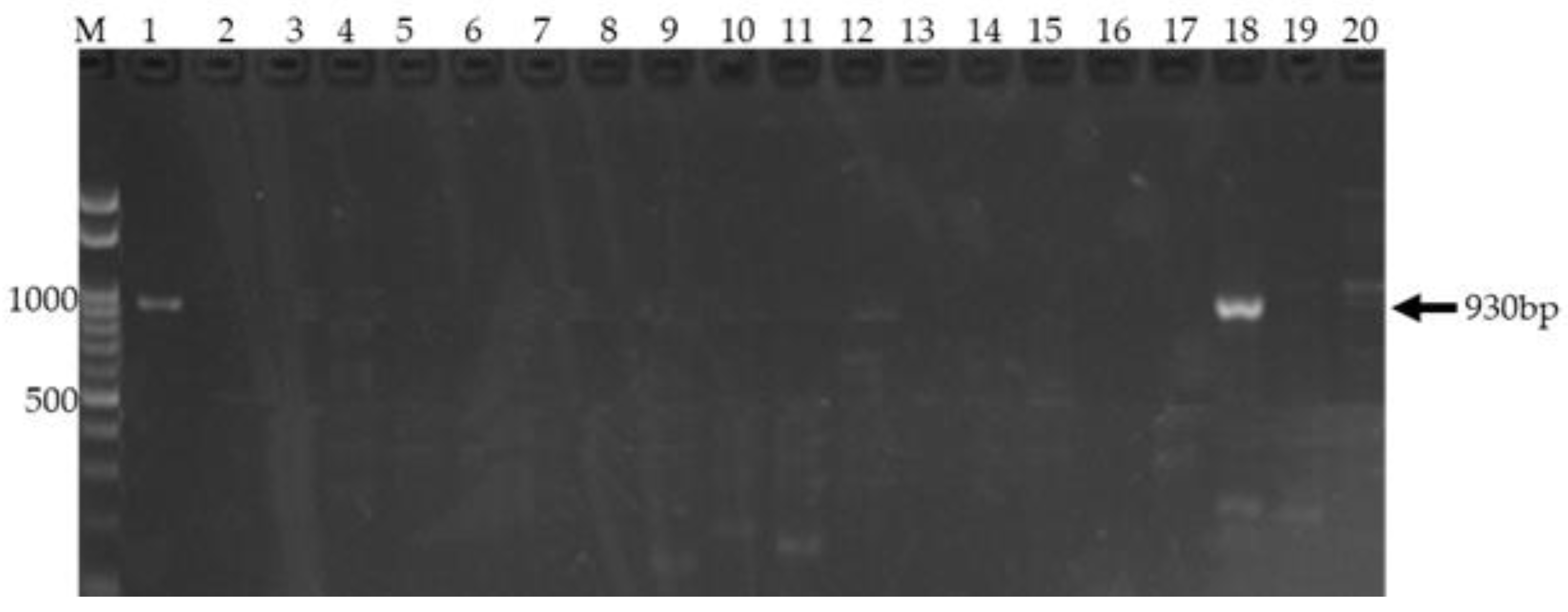

Agarose gel electrophoresis demonstrating amplification of the SHV gene.

Figure 3 shows Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products targeting the SHV gene. Lane M: 100 bp DNA ladder (left), used as a size marker. Lane 18 for sample 20: a single, prominent band at approximately 930 bp, indicating successful and specific amplification of the SHV gene. No other bands are observed, confirming reaction specificity.

The presence of a prominent band in Lane 1 (positive control) and 18 migrating to a position corresponding to approximately 930 bp, based on the DNA ladder in Lane M, indicates successful amplification of the SHV gene. The expected size of the SHV gene amplicon is 930 bp. The absence of bands at other positions in Lane 18 suggests the specificity of the PCR reaction for the target SHV gene. The DNA ladder in Lane M provides a reference for estimating the size of the amplified product.

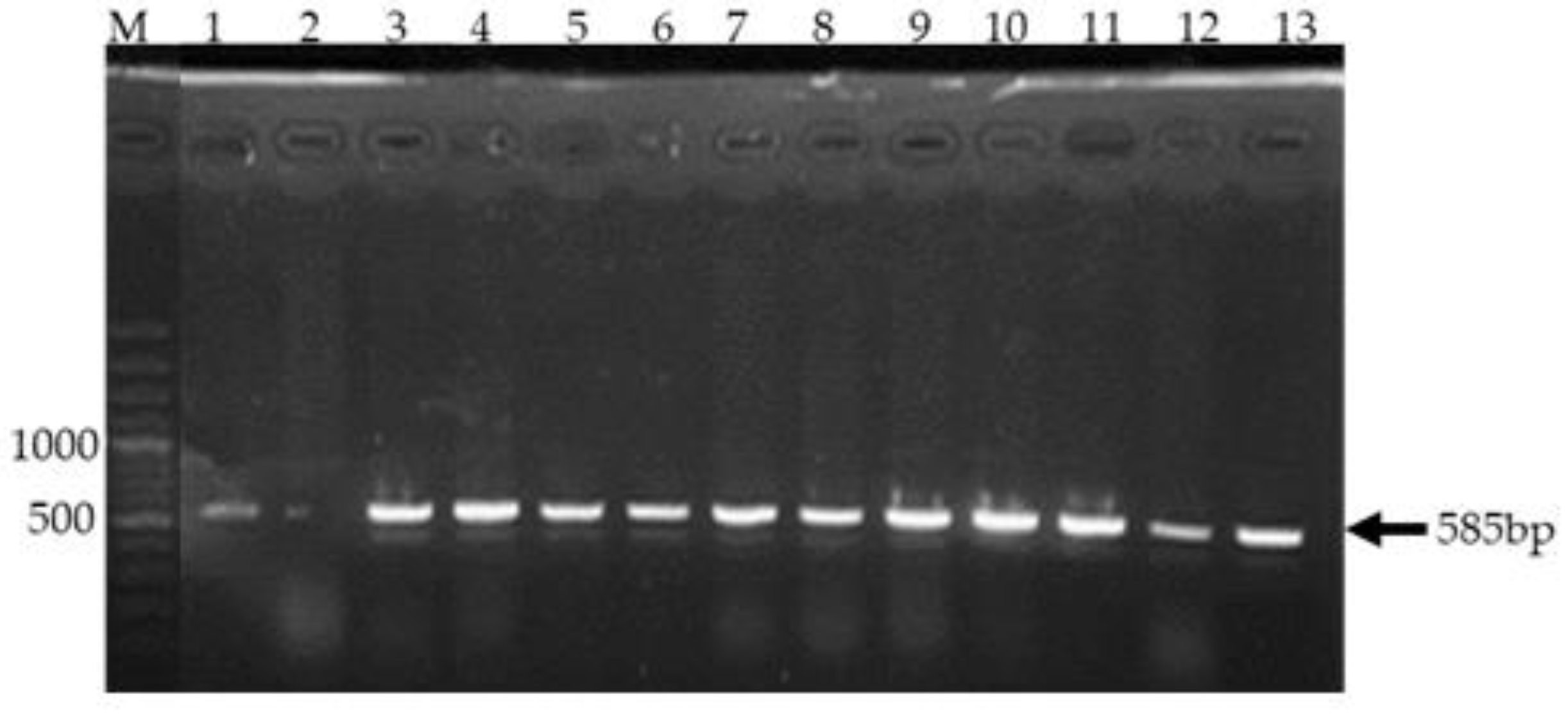

Agarose gel electrophoresis demonstrating amplification of the CTX gene.

Figure 4 shows Gel electrophoresis of PCR products targeting the 585 bp CTX gene fragment. Clear bands of approximately 585 bp were observed in lanes 1 and lane 3 to lane 13 representing samples 2,4,5,6,10,15,16,17,20,21,23 and 24 respectively indicating successful amplification. A 1000 bp DNA ladder in lane M served as a size reference. Lane 1 was a positive control.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was employed to amplify a 585 base pair (bp) fragment of the

Cefotaximase (CTX) gene. Gel electrophoresis was performed to visualize the amplification products. As shown in

Figure 4, distinct bands of approximately 585 bp were observed in lanes 3 to lane 13. The presence of these bands, corresponding to the expected amplicon size, confirms the successful amplification of the CTX gene in these samples. A 1000 bp DNA ladder was included in lane M as a molecular weight marker to facilitate accurate size determination of the amplified products.

Table 7.

Distribution of ESBL Genes in E. coli Isolates.

Table 7.

Distribution of ESBL Genes in E. coli Isolates.

| Detected gene(s) |

Number of E. coli isolates |

Σ (isolates) |

% E. coli isolates (n = 112) |

| CTX-M |

02,04,05,06,10,15,16,17,19,20,23,24 |

13 |

14.56 |

| SHV |

20 |

01 |

0.010 |

| TEM |

10,16,20,21 |

04 |

0.036 |

| Resistant Gene(s) |

Sample No. |

Total No.

Of Resistant Gene (s) |

% of presence of resistance genes in the 112 samples |

| CTX-M and TEM |

10,16,20,21 |

04 |

3.57 |

| CTX-M and SHV |

20 |

01 |

0.89 |

| TEM and SHV |

20 |

01 |

0.89 |

| CTX-M, SHV, and TEM |

20 |

01 |

0.89 |

| Non presence of ESBL producers |

112 - (02,04,05,06,10,15,16,17,19,20,21,23,24) |

99 |

88.39 |

| Proven ESBL producers |

02,04,05,06,10,15,16,17,19,20,21,23,24 |

13 |

11.61 |

The CTX-M gene was the most frequently detected ESBL gene, identified in 13 isolates, representing 11.61% of the total population. The TEM gene was present in 4 isolates (3.57%), while the SHV gene was detected in only a single isolate (0.89%).

Combinations of ESBL genes were also observed. The co-occurrence of CTX-M and TEM was found in 4 isolates (3.57%). The combination of CTX-M and SHV was detected in 1 isolate (0.89%). No isolates were found to harbor the combination of SHV and TEM, or all three genes concurrently.

Overall, 13 isolates (11.61%) were found to possess at least one of the tested ESBL genes, indicating the presence of potential ESBL production within this E. coli population. Notably, a substantial proportion of the isolates 99 out of 112 (88.39%) did not harbor any of the investigated ESBL genes, suggesting variability in the mechanisms of antibiotic resistance or susceptibility among the studied strains.

These findings highlight the prevalence of the CTX-M type ESBL gene among the E. coli isolates in this study, consistent with global trends of CTX-M dominance in ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae. The lower detection rates of SHV and TEM suggest they play a less significant role in ESBL production in this specific isolate collection. The presence of isolates without any of the tested ESBL genes underscores the potential for other resistance mechanisms or the presence of susceptible strains within the population. Further investigation into the specific types of CTX-M, SHV, and TEM genes, as well as phenotypic confirmation of ESBL production for all isolates, would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the resistance landscape in this E. coli population.

In the present study, 112 faecal samples were collected from intensively and free-range chickens, from which 13 E coli isolates were studied phenotypically and genotypically. Among these samples, 13 isolates were phenotypically confirmed ESBL producers, while 99 were phenotypically confirmed non-ESBL producers. Of the three beta-lactamase (bla) genes studied, blaTEM was detected among four (0.036%), followed by blaCTX-M in 11.61% and blaSHV in one (0.010%) phenotypically confirmed ESBL and non-ESBL isolates out of the 112 samples studied. Among these genotypically positive isolates, 13, (11.1%) isolates carried the blaSHV gene, and 4 (3.57%) carried the blaTEM gene 1 (0.01%) carried blaSHV. Both blaSHV and blaTEM genes were present in association with the blaCTX-M gene. One of the 13 samples carried all three genes, blaCTX-M, blaTEM and blaSHV together. In addition, one of the isolates carried the blaCTX-M and blaSHV genes together.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to detect the presence of ESBL-producing

E. coli in chickens and compare the antimicrobial activity profiles of

E. coli isolated from intensively reared and free-range chickens in selected districts of Zambia. The isolated ESBL-producing

E. coli isolates were then subjected to a PCR to identify antibiotic-resistant genes, providing a deeper understanding of their resistance patterns. The findings of this study suggest that poultry, regardless of the rearing system, can act as a potential reservoir for ESBL-producing

E. coli, which is consistent with the observations of previous studies [

31]. This highlights the role of poultry farming as a critical factor that contributes to the spread of antimicrobial-resistant pathogens [

11,

32,

33,

34]. Additionally, the study provides important insights that the extensive use of antibiotics in poultry production may contribute to the emergence of antimicrobial-resistant strains [

11,

32,

33,

34]. The prevalence of ESBL-producing

E. coli in chickens in Zambia, as observed in this study, underscores the scope of antimicrobial resistance in the country and emphasizes the need for improved management practices in poultry farming.

In terms of descriptive statistics, the study found that tetracycline was the most frequently used antibiotic, accounting for 14 instances and 12.61%, while Sulphadimidine was among the least frequently used antibiotics, with only one instance and 0.90%. These results are similar to what was previously observed by others [

35], who also reported tetracycline as a commonly used antibiotic in poultry. The predominant use of tetracycline may reflect its widespread availability and affordability, despite the growing concerns about its role in the development of antimicrobial resistance. The study also explored the reasons behind antibiotic use in poultry farming. This study represents a novel contribution to the understanding of the prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing

E. coli in chicken populations by revealing that profiles of these bacteria do not differ significantly between intensively-reared and free-ranging chickens. By demonstrating that both production systems can serve as reservoirs for ESBL-producing

E. coli, this research provides critical insights into the public health implications of poultry rearing practices. The results suggest that antimicrobial resistance is not solely a consequence of antibiotic use in intensive farming but is a broader issue affecting various poultry production systems.

In this study, the prevalence and distribution of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) genes among Escherichia coli isolates from both intensively, and extensively reared chickens were investigated to assess the landscape of antibiotic resistance within this bacterial population. A total of 13 samples (11.61%) were confirmed as ESBL producers, primarily attributed to the presence of the CTX-M gene, underscoring its dominant role in conferring resistance. Conversely, the majority of samples (88.39%) lacked any of the tested ESBL genes, suggesting the existence of alternative resistance mechanisms or non-ESBL-mediated pathways within these strains. The distribution of ESBL genes revealed that CTX-M was the most frequently detected, present in 11.61% of the isolates, followed by TEM (3.57%) and SHV (0.01%), with some isolates harboring multiple genes. Notably, combinations such as CTX-M with TEM were observed, indicating potential co-expression of resistance determinants. These findings highlight the predominance of CTX-M among ESBL-producing E. coli in this population and suggest a complex resistance gene landscape that warrants further molecular characterization.

This data indicates no significant difference in the prevalence of ESBL-producing

E. coli between the two chicken rearing systems, which contradicts the common assumption that intensive systems exclusively drive the spread of resistant pathogens [

36]. The relatively low usage of antimicrobials in free-range chickens, notably the absence of substantial antibiotic administration, challenges the perception that antimicrobial use is the sole contributor to resistance development. This points to the possible role of environmental contamination and interspecies transmission pathways as facilitating factors for the spread of resistant genes. It aligns with findings from similar studies in Africa, where extensive environmental reservoirs of resistant bacteria potentially influence the resistance profiles in livestock, regardless of the management system of the livestock [

37,

38]. Globally, multiple studies have reported the widespread presence of ESBL-producing bacteria in poultry, irrespective of farming systems. For instance, researchers observed comparable prevalence rates of ESBL-producing

E. coli in conventional and organic poultry farms across Europe, highlighting that AMR genes are widespread across different production systems [

39]. Similarly, a case study in the United Kingdom unraveled that the dissemination of ESBL genes is influenced by multiple factors—including the use of antimicrobials, environmental contamination, and horizontal gene transfer—rather than solely by farm management practices. This indicates that even in systems with reduced antimicrobial use, resistance genes can persist and spread, emphasizing the importance of a One Health approach to AMR surveillance [

40].

Within Africa, data on ESBL-producing bacteria in poultry remain limited but are increasingly emerging. A study done in Ghana demonstrated high carriage rates of ESBL-producing

E. coli in poultry farms, regardless of farm type, suggesting that environmental contamination and antibiotic use practices might play significant roles in resistance dissemination across various rearing systems [

41]. While numerous studies on carriage of ESBL-producing

E. coli in intensively-reared chickens have been done in the Southern African context, research in comparative carriage of ESBL-producing

E. coli between intensively and extensively reared chickens remains sparse. In Zambia, our study is the first of its kind. These findings suggest that local environmental factors, antibiotic usage patterns, and cross-sectoral interactions contribute substantially to the AMR burden, overshadowing the influence of rearing system classification alone.

These findings especially provide valuable information about antimicrobial usage patterns and comparative carriage of ESBL-producing E. coli in the context of poultry production systems in Kapiri Mposhi and Kabwe Districts of Zambia. This information can contribute to a better understanding of the factors influencing antibiotic use in poultry and help inform interventions aimed at reducing the emergence of resistance. However, further research is needed to explore the underlying reasons for the similar prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli in both intensive and extensive chicken production systems, despite the relatively sparing use of antibiotics in extensively reared chickens, and to develop strategies for effective antimicrobial stewardship in poultry production. These findings highlight the necessity for continued monitoring of antibiotic resistance patterns in E. coli to inform antimicrobial stewardship strategies and public health interventions.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the study demonstrated a significant presence of ESBL-producing E. coli in intensively reared and free-range chickens in Zambia, and there was no significant difference in the carriage of ESBL-producing E. coli in the two rearing systems, revealing the importance of the environment in the dissemination of the bacteria. The high antimicrobial resistance and genetic diversity of ESBL genes emphasize the urgent need for enhanced antibiotic stewardship programs in the poultry industry. The study also revealed patterns of antibiotic use and treatment advice, highlighting areas for targeted interventions. Moving forward, a One Health approach that integrates actions across human, animal, and environmental health sectors will be crucial in addressing antimicrobial resistance in poultry and safeguarding public health. Strengthening surveillance systems, promoting appropriate antibiotic use, and enhancing education among poultry farmers are important steps in addressing antimicrobial resistance and safeguarding public health in the poultry industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, KC., BMH., RSM. and ITS.; methodology, KC., BMH., RSM., GM., FM., EK., FYG., GM., MM., RSM., ITS.; software, KC.; validation, BMH., RSM., GM., FM., EK., FYG., GM., MM., RSM. and ITS.; formal analysis, MM, BHM.; investigation, KC., BHM.; resources, ACEPHEM, ACEIDAH, Government of Zambia.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, KC., BMH.; writing—review and editing, KC., and ITS.; visualization, KC.; supervision, BMH., RSM., ITS.; project administration, RSM.; funding acquisition, KC., BMH., RSM., ITS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Academic Centre of Excellence in Public Health and Herbal Medicine (ACEPHEM) at the University of Malawi, College of Medicine, grant number P151847. Academic Centre of Excellence in Infectious Diseases of Humans and Animals (ACEIDHA) at the University of Zambia, School of Veterinary Medicine, grant number P151847; Department of Veterinary Services, Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock, Zambian Government, support through Recurrent Departmental Charges (RDC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Malawi College of Medicine Research Ethics Committee (COMREC) (P.08/20/3116 and 11 November 2020).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The Authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Kamuzu University of Health Sciences and the Africa Center of Excellence in Public and Herbal Medicine (ACEPHEM), as well as the University of Zambia, School of Veterinary Medicine and the Africa Center of Excellence for Infectious Diseases of Humans and Animals (ACEDHA), for their unwavering support throughout this study. The support from the Directorate of Veterinary Services, Veterinary Assistants in Kabwe District, is greatly acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACEDHA |

Africa Center of Excellence for Infectious Diseases of Humans and Animals |

| ACEPHEM |

African Center of Excellence in Public and Herbal Medicine |

| AMR |

Antimicrobial Resistance |

| AMRCC |

Antimicrobial Resistance Coordinating Committee |

| CIP |

Ciprofloxacin |

| CL |

Chloramphenicol |

| COMREC |

College of Medicine Research Ethics Committee |

| CTX |

Cefotaxime |

| CTX-M |

Cefotaxime-Munich |

| ESβL |

Escherichia coli |

| GEN |

Gentamicin |

| NAP |

National Action Plan |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SHV |

Sulphydryl Variable |

| SXT |

Sulfamethoxazole |

| TAZ |

Piperacillin-tazobactam |

| TEM |

Temoniera |

| TET |

Tetracycline |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Jenkins C. Commentary: Whole-Genome Sequencing Data for Serotyping Escherichia coli—It’s Time for a Change! J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2402–3. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed SK, Hussein S, Qurbani K, et al. Antimicrobial resistance: Impacts, challenges, and future prospects. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health. 2024;2:100081. [CrossRef]

- van den Bogaard AE. Antibiotic resistance of faecal Escherichia coli in poultry, poultry farmers and poultry slaughterers. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2001;47:763–71. [CrossRef]

- von Wintersdorff CJH, Penders J, van Niekerk JM, et al. Dissemination of Antimicrobial Resistance in Microbial Ecosystems through Horizontal Gene Transfer. Front Microbiol. 2016;7. [CrossRef]

- Dierikx CM, Van Der Goot JA, Smith HE, et al. Presence of ESBL/AmpC -producing Escherichia coli in the broiler production pyramid: A descriptive study. PLoS One. 2013;8. [CrossRef]

- 2023 LIVESTOCK SURVEY REPORT REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA MINISTRY OF FISHERIES AND LIVESTOCK O F Z A M B I A Republic of Zambia.

- Ziba MW, Bowa B, Romantini R, et al. Journal of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Health Occurrence and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella spp. in broiler chicken neck skin from slaughterhouses in Zambia. S Liverpool. 2020.

- Phiri N, Mainda G, Mukuma M, et al. Antibiotic-resistant Salmonella species and Escherichia coli in broiler chickens from farms, abattoirs, and open markets in selected districts of Zambia. J Epidemiol Res. Published Online First: 2020. [CrossRef]

- Rouger A, Tresse O, Zagorec M. Bacterial contaminants of poultry meat: Sources, species, and dynamics. Microorganisms. 2017;5.

- Musaba EC, Mseteka M. Cost efficiency of small-scale commercial broiler production in Zambia: A stochastic cost frontier approach. Developing Country Studies. 2014;4.

- Hedman HD, Vasco KA, Zhang L. A Review of Antimicrobial Resistance in Poultry Farming within Low-Resource Settings. Animals. 2020;10:1264. [CrossRef]

- Agyare C, Etsiapa Boamah V, Ngofi Zumbi C, et al. Antibiotic Use in Poultry Production and Its Effects on Bacterial Resistance. Antimicrobial Resistance - A Global Threat. 2019.

- Chileshe C, Shawa M, Phiri N, et al. Detection of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL)-Producing Enterobacteriaceae from Diseased Broiler Chickens in Lusaka District, Zambia. Antibiotics. 2024;13. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Ronquillo M, Angeles Hernandez JC. Antibiotic and synthetic growth promoters in animal diets: Review of impact and analytical methods. Food Control. Published Online First: 2017. [CrossRef]

- Puspandari N, Sunarno S, Febrianti T, et al. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli surveillance in the human, food chain, and environment sectors: Tricycle project (pilot) in Indonesia. One Health. 2021;13. [CrossRef]

- Ena J, Arjona F, Martínez-Peinado C, et al. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. Urology. 2006;68. [CrossRef]

- Samarasinghe S. Analysis of unique and specific genetic markers for diagnosis of antibiotic resistant, pathogenic escherichia coli (E. coli) encoding resistance to the third generation antibiotic, cefotaxime. European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine. 2015;2. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The evolving threat of antimicrobial resistance: Options for action. WHO Publications. 2014.

- Breugelmans S, Muylle S, Cornillie P, et al. Age determination of poultry: A challenge for customs. Vlaams Diergeneeskd Tijdschr. 2007;76. [CrossRef]

- Doherty SP, Foster A, Best J, et al. Estimating the age of domestic fowl (Gallus gallus domesticus L. 1758) cockerels through spur development. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 2021;31. [CrossRef]

- Persoons D, Bollaerts K, Smet A, et al. The Importance of Sample Size in the Determination of a Flock-Level Antimicrobial Resistance Profile for Escherichia coli in Broilers. Microbial Drug Resistance. 2011;17:513–9. [CrossRef]

- De Carli S, Ikuta N, Lehmann FKM, et al. Virulence gene content in Escherichia coli isolates from poultry flocks with clinical signs of colibacillosis in Brazil. Poult Sci. 2015;94. [CrossRef]

- Nene M, Kunene NW, Pierneef R, et al. Profiling the diversity of the village chicken faecal microbiota using 16S rRNA gene and metagenomic sequencing data to reveal patterns of gut microbiome signatures. Front Microbiol. 2024;15. [CrossRef]

- Nylund L, Heilig HGHJ, Salminen S, et al. Semi-automated extraction of microbial DNA from feces for qPCR and phylogenetic microarray analysis. J Microbiol Methods. 2010;83. [CrossRef]

- Erkmen O. Pure culture techniques. Laboratory Practices in Microbiology. 2021.

- Islam M, Islam M, Fakhruzzaman M. Isolation and identification of Escherichia coli and Salmonella from poultry litter and feed. International Journal of Natural and Social Sciences. 2014.

- Basavaraju M, Gunashree BS. Escherichia coli : An Overview of Main Characteristics . Escherichia coli - Old and New Insights. 2023.

- Weinstein MP. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2019.

- Kazemian H, Heidari H, Ghanavati R, et al. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterization of ESBL-, AmpC-, and Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli Isolates. Medical Principles and Practice. 2019;28. [CrossRef]

- Mahmud ZH, Kabir MH, Ali S, et al. Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli in Drinking Water Samples From a Forcibly Displaced, Densely Populated Community Setting in Bangladesh. Front Public Health. 2020;8. [CrossRef]

- Brower CH, Mandal S, Hayer S, et al. The prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli in poultry chickens and variation according to farming practices in Punjab, India. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125. [CrossRef]

- Mak PHW, Rehman MA, Kiarie EG, et al. Production systems and important antimicrobial resistant-pathogenic bacteria in poultry: a review. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2022;13:148. [CrossRef]

- Bamidele O, Amole TA, Oyewale OA, et al. Antimicrobial Usage in Smallholder Poultry Production in Nigeria. Vet Med Int. 2022;2022. [CrossRef]

- Abreu R, Semedo-Lemsaddek T, Cunha E, et al. Antimicrobial Drug Resistance in Poultry Production: Current Status and Innovative Strategies for Bacterial Control. Microorganisms. 2023;11.

- Ulomi WJ, Mgaya FX, Kimera Z, et al. Determination of Sulphonamides and Tetracycline Residues in Liver Tissues of Broiler Chicken Sold in Kinondoni and Ilala Municipalities, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Antibiotics. 2022;11. [CrossRef]

- Aboah J, Ngom B, Emes E, et al. Mapping the effect of antimicrobial resistance in poultry production in Senegal: an integrated system dynamics and network analysis approach. Front Vet Sci. 2023;10. [CrossRef]

- Koutsoumanis K, Allende A, Álvarez-Ordóñez A, et al. Role played by the environment in the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) through the food chain. EFSA Journal. 2021;19. [CrossRef]

- Hasan B, Swedberg G. Molecular Characterization of Clinically Relevant Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases blaCTX-M-15-Producing Enterobacteriaceae Isolated from Free-Range Chicken from Households in Bangladesh. Microbial Drug Resistance. 2022;28. [CrossRef]

- Kola A, Kohler C, Pfeifer Y, et al. High prevalence of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in organic and conventional retail chicken meat, Germany. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2012;67. [CrossRef]

- Huizinga P, Van Den Bergh MK, Rossen JW, et al. Decreasing prevalence of contamination with extended-spectrum beta-lactamaseproducing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-E) in retail chicken meat in the Netherlands. PLoS One. 2019;14. [CrossRef]

- Falgenhauer L, Imirzalioglu C, Oppong K, et al. Detection and characterization of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli from humans and poultry in Ghana. Front Microbiol. 2019;10. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. Further, the views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).