Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Methods

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of Infants Sensitized to HDMs

3.2. Laboratory Findings in HDM-Sensitized Infants

3.3. Comparison Between the HDM (+) and HDM (–) Groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HDM | House dust mite |

| sIgE | Specific immunoglobulin E |

References

- Miyamoto, T.; Oshima, S.; Ishizaki, T.; Sato, S.H. Allergenic identity between the common floor mite (Dermatophagoides farinae Hughes, 1961) and house dust as a causative antigen in bronchial asthma. J Allergy 1968, 42, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarsfield, J.K. Role of house-dust mites in childhood asthma. Arch Dis Child 1974, 49, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ree, H.I.; Jeon, S.H.; Lee, I.Y.; Hong, C.S.; Lee, D.K. Fauna and geographical distribution of house dust mites in Korea. Korean J Parasitol 1997, 35, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Hahm, M.I.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, W.K.; Chae, Y.; Park, Y.M.; et al. Sensitization to aeroallergens in Korean children: a population-based study in 2010. J Korean Med Sci 2011, 26, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.Y.; Park, J.W.; Hong, C.S. House dust mite allergy in Korea: the most important inhalant allergen in current and future. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2012, 4, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.C.; Hwang, C.S.; Chung, H.J.; Purev, M.; Al Sharhan, S.S.; Cho, H.J.; et al. Geographic and demographic variations of inhalant allergen sensitization in Koreans and non-Koreans. Allergol Int 2019, 68, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmage, S.C.; Lowe, A.J.; Matheson, M.C.; Burgess, J.A.; Allen, K.J.; Abramson, M.J. Atopic dermatitis and the atopic march revisited. Allergy 2014, 69, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabryszewski, S.J.; Hill, D.A. One march, many paths: Insights into allergic march trajectories. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eapen, A.A.; Kim, H. The Phenotype of the Food-Allergic Patient. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2021, 41, 165–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, M.A.; Linneberg, A.; Kleine-Tebbe, J.; De Blay, F.; Hernandez Fernandez de Rojas, D.; Virchow, J.C.; et al. Respiratory allergy caused by house dust mites: What do we really know? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015, 136, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, H.; Chieppa, M.; Perros, F.; Willart, M.A.; Germain, R.N.; Lambrecht, B.N. House dust mite allergen induces asthma via Toll-like receptor 4 triggering of airway structural cells. Nat Med 2009, 15, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sporik, R.; Holgate, S.T.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E.; Cogswell, J.J. Exposure to House-Dust Mite Allergen (Der p I) and the Development of Asthma in Childhood. 1990, 323, 502-7.

- Brussee, J.E.; Smit, H.A.; van Strien, R.T.; Corver, K.; Kerkhof, M.; Wijga, A.H.; et al. Allergen exposure in infancy and the development of sensitization, wheeze, and asthma at 4 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005, 115, 946–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celedón, J.C.; Milton, D.K.; Ramsey, C.D.; Litonjua, A.A.; Ryan, L.; Platts-Mills, T.A.; et al. Exposure to dust mite allergen and endotoxin in early life and asthma and atopy in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007, 120, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, K.W.; Chiu, C.Y.; Tsai, M.H.; Liao, S.L.; Chen, L.C.; Hua, M.C.; et al. Asymptomatic toddlers with house dust mite sensitization at risk of asthma and abnormal lung functions at age 7 years. World Allergy Organ J 2019, 12, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illi, S.; von Mutius, E.; Lau, S.; Niggemann, B.; Grüber, C.; Wahn, U. Perennial allergen sensitisation early in life and chronic asthma in children: a birth cohort study. Lancet 2006, 368, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bilderling, G.; Mathot, M.; Agustsson, S.; Tuerlinckx, D.; Jamart, J.; Bodart, E. Early skin sensitization to aeroallergens. 2008, 38, 643-8.

- Casas, L.; Sunyer, J.; Tischer, C.; Gehring, U.; Wickman, M.; Garcia-Esteban, R.; et al. Early-life house dust mite allergens, childhood mite sensitization, and respiratory outcomes. Allergy 2015, 70, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, S.; Illi, S.; Sommerfeld, C.; Niggemann, B.; Bergmann, R.; von Mutius, E.; et al. Early exposure to house-dust mite and cat allergens and development of childhood asthma: a cohort study. The Lancet 2000, 356, 1392–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahn, U.; Bergmann, R.; Kulig, M.; Forster, J.; Bauer, C.P. The natural course of sensitisation and atopic disease in infancy and childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 1997, 8(10 Suppl), 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, P.G.; Jones, C.A. The development of the immune system during pregnancy and early life. Allergy 2000, 55, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brough, H.A.; Liu, A.H.; Sicherer, S.; Makinson, K.; Douiri, A.; Brown, S.J.; et al. Atopic dermatitis increases the effect of exposure to peanut antigen in dust on peanut sensitization and likely peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015, 135, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, E.H.; Rajakulendran, M.; Lee, B.W.; Van Bever, H.P.S. Epicutaneous sensitization to food allergens in atopic dermatitis: What do we know? Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2020, 31, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, H.A.; Nadeau, K.C.; Sindher, S.B.; Alkotob, S.S.; Chan, S.; Bahnson, H.T.; et al. Epicutaneous sensitization in the development of food allergy: What is the evidence and how can this be prevented? Allergy 2020, 75, 2185–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boralevi, F.; Hubiche, T.; Léauté-Labrèze, C.; Saubusse, E.; Fayon, M.; Roul, S.; et al. Epicutaneous aeroallergen sensitization in atopic dermatitis infants - determining the role of epidermal barrier impairment. Allergy 2008, 63, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M.; Meguro, T.; Ito, Y.; Tokunaga, F.; Hashiguchi, A.; Seto, S. Close Positive Correlation between the Lymphocyte Response to Hen Egg White and House Dust Mites in Infants with Atopic Dermatitis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2015, 166, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, E.S.; Kjaer, H.F.; Eller, E.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Høst, A.; Mortz, C.G.; et al. Early-life sensitization to hen’s egg predicts asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis at 14 years of age. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2017, 28, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, Y.; Perzanowski, M.S. Allergic sensitization and the environment: latest update. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2014, 14, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, Y.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Sohn, M.H.; Lee, H.R. Effects of Vacuuming Mattresses on Allergic Rhinitis Symptoms in Children. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2019, 11, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N (%) or mean ± SD | ||

|

Infants< 24 months (N=96) |

Infants< 12 months (N=11) |

|

| Age (months) | 17.2 ± 4.3 | 10.3 ± 0.9 |

| Male | 63 (64.6%) | 8 (72.7%) |

| Doctor-diagnosed allergic disease | ||

| Atopic dermatitis | 71 (74.0%) | 10 (90.9%) |

| Food allergy | 55 (57.3%) | 11 (100%) |

| Anaphylaxis | 10 (10.4%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| Recurrent wheezing (≥ 4 times) | 31 (32.3%) | 4 (36.4%) |

| Asthma | 23 (24.2%) | 3 (27.3%) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 30 (31.2%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| Characteristics | N (%) or mean ± SD | |

| Infants <24 months | Infants <12 months | |

| Total IgE* (kU/L) | 415.0 ± 674.1 | 368.2 ± 718.9 |

| HDM† sIgE‡ (kU/L) | 12.4 ± 23.6 | 13.3 ± 29.5 |

| Egg whitesensitization | 69 (75.0%) | 10 (90.9%) |

| Cow’s milk sIgEsensitization | 54 (62.8%) | 9 (81.8%) |

|

Multiple food sensitization (≥ 3 food allergens) |

48 (51.1%) | 8 (72.7%) |

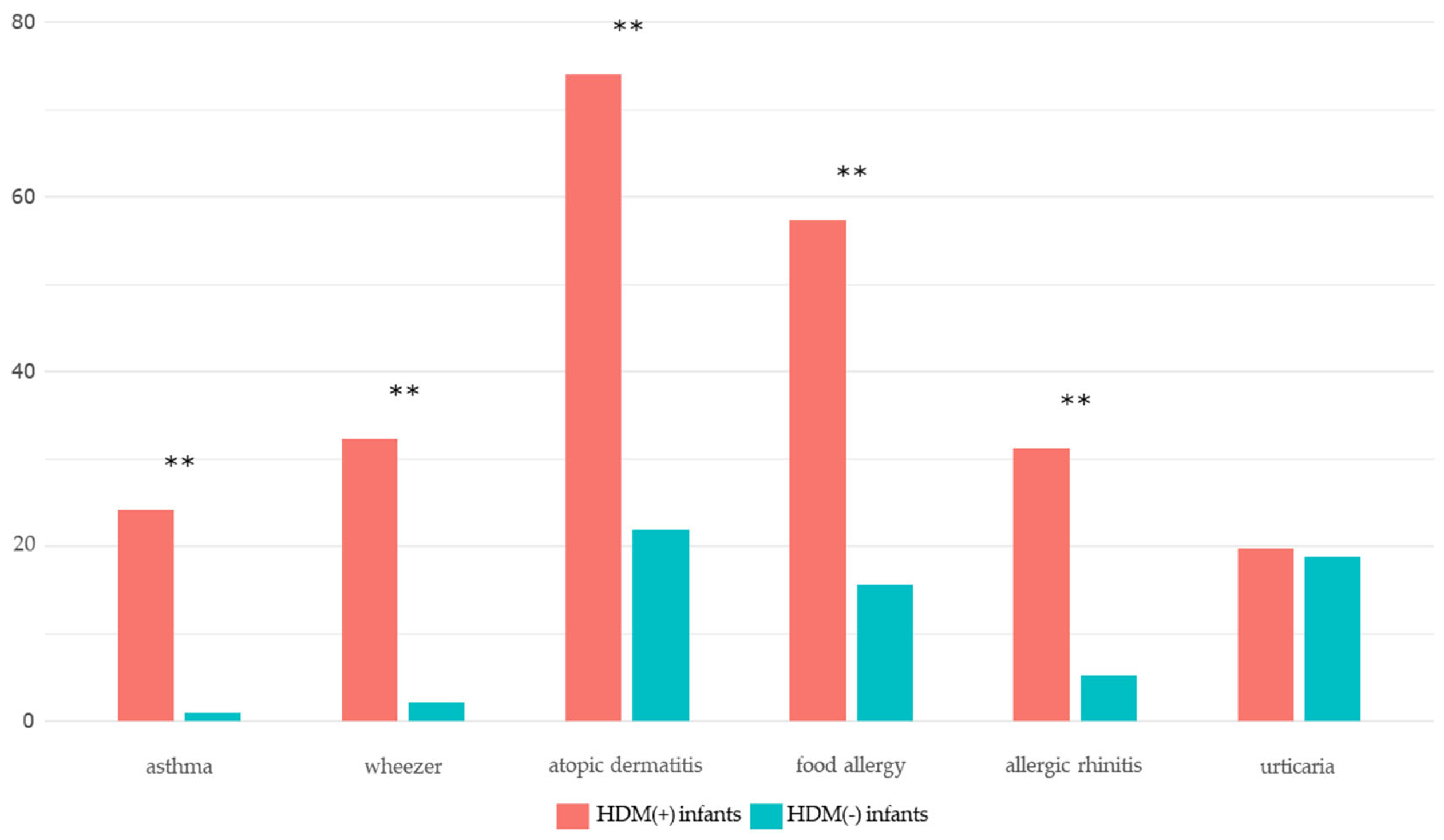

| Variables | HDM (+) group | HDM (−) group | P-value |

| Atopic dermatitis | 71 (74.0) | 21 (21.9) | <0.001*** |

| Food allergy | 55 (57.3) | 15 (15.6) | <0.001*** |

| Anaphylaxis | 10 (10.4) | 3 (3.1) | 0.096 |

| Recurrent wheezing (≥ 4 times) | 31 (32.3) | 2 (2.1) | <0.001*** |

| Asthma | 23 (24.2) | 1 (1.0) | <0.001*** |

| Allergic rhinitis | 30 (31.2) | 5 (5.2) | <0.001*** |

| Urticaria | 19 (19.8) | 18 (18.8) | 1.000 |

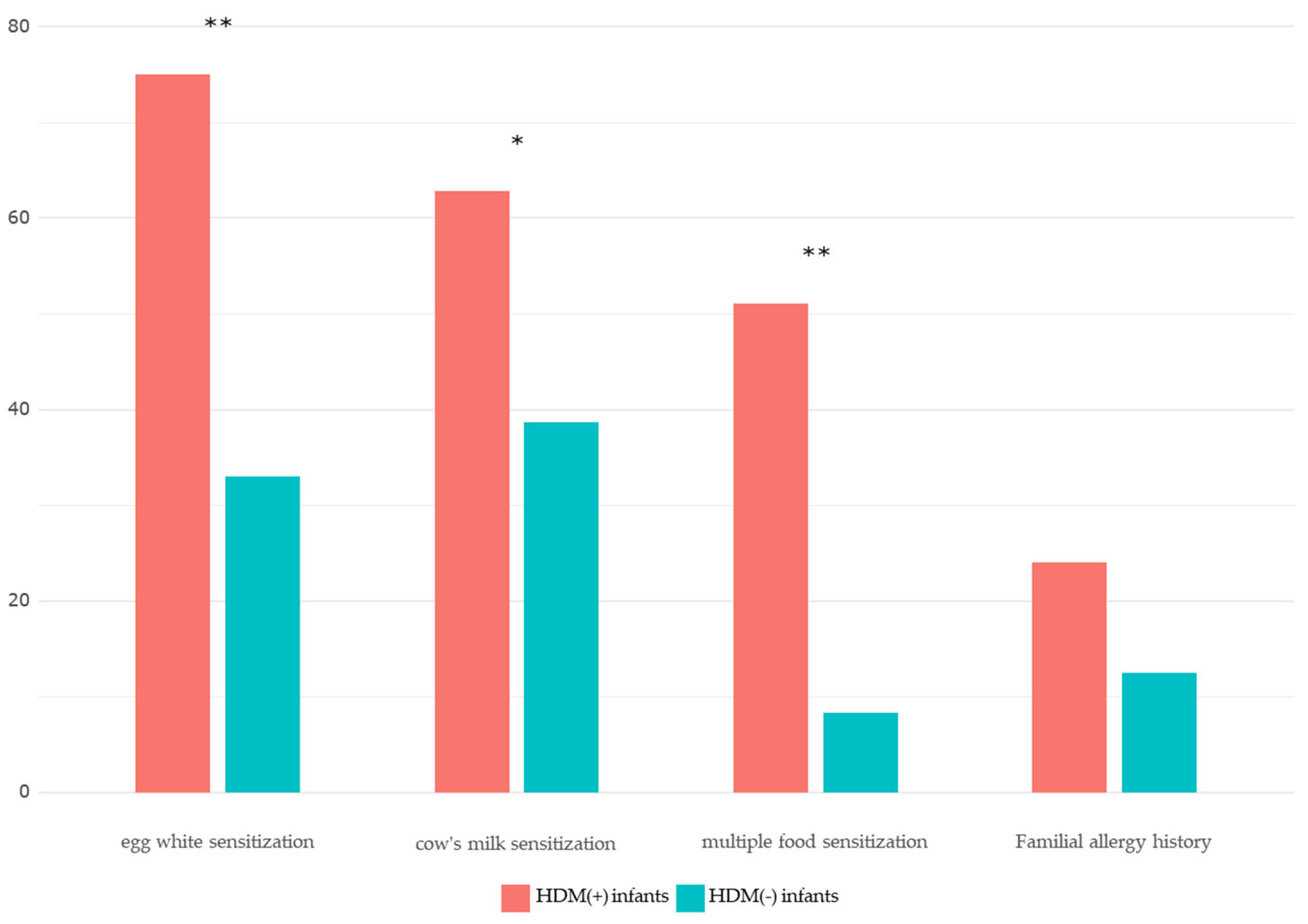

| Egg whitesensitization | 69 (75.0) | 31 (33.0) | <0.001*** |

| Milk sIgEsensitization | 54 (62.8) | 36 (38.7) | 0.007** |

|

Multiple foodsensitization (≥ 3 food allergens) |

48 (51.1) | 8 (8.3) | <0.001*** |

| Variables |

HDM (+) group (mean ± SD) |

HDM (−) group (mean ± SD) |

P-value |

| Log(total IgE+1) | 2.17 ± 0.64 | 1.57 ± 0.66 | ≤ 0.001 |

| Egg white sIgE (kU/L) | 16.13 ± 29.65 | 1.15 ± 3.30 | ≤0.001 |

| Cow’s milk sIgE (kU/L) | 6.08 ± 16.20 | 0.67 ± 1.36 | 0.001 |

|

Total IgE coefficient (P-value) |

Egg white sIgE coefficient (P-value) |

Cow’s milk sIgE coefficient (P-value) |

|

| HDM sIgE | 0.326 (0.002) | 0.312 (0.002) | 0.215 (0.047) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).