1. Introduction

Melanoma is a highly aggressive skin cancer with increasing global incidence and significant mortality, especially in metastatic cases [

1]. Its incidence continues to grow worldwide, with men experiencing higher rates than women [

2]. Geographic, ethnic, and socioeconomic factors, along with disparities in access to early detection and care, contribute to differences in incidence and outcomes [

1]. While early-stage melanoma can often be successfully treated with surgical removal, managing unresectable or metastatic disease poses major challenges due to resistance to current treatments [

3]. Conventional therapies like chemotherapy and radiotherapy frequently fail because of inherent or acquired resistance [

4]. Immunotherapy, especially immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), has greatly improved outcomes by leveraging the immune system to fight melanoma [

5]. However, therapeutic resistance and immune evasion still present significant obstacles to long-term success. Therefore, new molecular targets are urgently needed to enhance treatment responses and survival rates in patients with advanced disease.

The androgen receptor (AR) is a ligand-activated transcription factor that belongs to the nuclear receptor superfamily and is a key mediator of androgen signaling [

6]. AR plays a crucial role in regulating gene expression, DNA repair, and maintaining genome integrity [

7,

8]. In prostate cancer, AR signaling is a major driver of tumorigenesis by regulating genes involved in proliferation, survival, and differentiation [

9,

10]. Consequently, androgen deprivation therapy is a mainstay of treatment [

11]. While traditionally overlooked in non-hormone-dependent cancers, AR is now gaining attention for its potential role in malignancies such as melanoma [

7,

12,

13,

14].

Epidemiological data demonstrate sex-based disparities in melanoma incidence and outcomes, with men exhibiting higher incidence and mortality rates than women [

15,

16,

17,

18]. This phenomenon is not entirely explained by behavioral or environmental factors [

12,

19]. These observations have sparked interest in the influence of sex hormones and their receptors, including AR, on melanoma biology.

In this review, we explore the multifaceted role of AR in melanoma, with a focus on three major domains: metastasis, immunosuppression, and therapeutic resistance. We also discuss the integration of AR-targeted strategies with existing treatment modalities, highlighting emerging approaches and the potential for sex-specific interventions.

2. Androgen Receptor in Melanoma Metastasis

Metastasis remains the leading cause of melanoma-related mortality and represents a major obstacle to effective treatment [

20]. While BRAF and NRAS oncogenic mutations, as well as environmental factors such as ultraviolet (UV) exposure, have traditionally dominated discussions of melanoma progression [

21,

22], recent data implicate sex hormones, particularly the AR, in modulating the metastatic behavior of melanoma cells.

AR is present at low levels in all primary melanocytes, but to varying degrees among melanoma cells. Some tumors have high levels of AR protein and mRNA (AR⁺), while others show minimal to no expression (AR⁻) [

12,

14,

23]. When expressed at high levels, AR is mainly localized to the nucleus of melanoma cells, whereas it is predominantly distributed perinuclearly in low AR-expressing melanoma cell lines and primary melanocytes [

23].

AR promotes melanoma invasiveness through multiple integrated pathways. Wang et al. demonstrated that AR enhances the expression of miR-539-3p, a microRNA that suppresses the deubiquitinase USP13, leading to destabilization of MITF, a melanocytic lineage transcription factor critical for maintaining cell differentiation [

14]. The subsequent downregulation of MITF favors the expression of AXL, a receptor tyrosine kinase associated with invasive and therapy-resistant phenotypes, thereby promoting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastatic potential. Furthermore, utilizing an in vivo melanoma metastasis model, they demonstrated that AR increases melanoma lung metastasis by modifying MITF [

14].

Supporting evidence from prostate cancer shows that AR can upregulate EMT-related transcription factors like Twist-related protein 1 (TWIST1) and zinc finger protein SNAI1 (SNAI1), and upregulate matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) such as MMP2 and MMP9, which facilitate matrix degradation [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], Although these mechanisms are best defined in prostate cancer, in vivo melanoma models confirm that high AR activity enhances metastatic spread [

23].

Ma et al., working with several melanoma cell lines and primary melanoma cells, demonstrated that silencing AR in melanoma cells leads to the downregulation of

CDCA7L, thereby inducing cellular senescence [

23]. Notably,

CDCA7L is a transcriptional repressor that interacts with C-MYC, sharing oncogenic function. They also observed the upregulation of mRNA for

CDKN1A and several immunomodulators, such as intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (

ICAM1) and the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin 6 (

IL-6). Furthermore, several genes involved in melanogenesis, differentiation, and melanoma progression were upregulated or downregulated following AR silencing. These data support the functional role of AR in the melanoma development and metastasis. Additionally, they demonstrated that reducing or pharmacologically inhibiting AR limits melanoma development and leads to greater infiltration of macrophages within the tumor, along with an increased presence of cytotoxic T cells in immune-competent mouse models [

23].

Recent work by Liu et al. identified the exact mechanism by which AR controls the transcriptional increase of fucosyltransferase 4 (FUT4) expression, highlighting its key role in enhancing melanoma invasiveness. In this process, AR-driven FUT4 signaling alters cell-cell adhesion by disrupting N-cadherin-catenin-based junctional complexes between melanoma cells, which impacts adherens junctions (AJs) and promotes cellular spread [

12]. Additionally, they demonstrated that androgen stimulation in melanoma cells did not significantly affect genes typically regulated by AR in prostate cancer, indicating that AR drives a distinct transcriptional program in melanoma cells.

Despite strong evidence linking AR to pro-metastatic behavior, the relationship can be context-dependent. Singh et al., using The Cancer Genome Atlas human skin cutaneous melanoma (TCGA SKCM) dataset and analyzing data from 353 patients with available RNA data, reported that high AR protein levels were associated with improved survival in certain melanoma cohorts [

29], indicating that AR might have tumor-suppressive effects in specific contexts. Possible explanations include isoform-specific signaling, post-translational modifications, or compensatory immune activation. However, the expression of AR splice variants in melanoma tumors has not yet been studied. These findings underscore the need for stratifying patients based on AR expression and tumor context.

The sex-based disparities in melanoma outcomes further support the involvement of AR in disease progression. Male patients tend to exhibit higher AR activity and worse clinical outcomes [

30], even when accounting for environmental and behavioral factors, indicating that androgen signaling can contribute to the more aggressive disease observed in men.

Further research is needed to clarify how AR expression and activity influence metastasis and treatment response. Future studies should investigate how AR signaling intersects with other oncogenic and immune pathways, and how hormonal modulation can be integrated into therapeutic strategies. These efforts can uncover new opportunities for precision medicine approaches in melanoma, including AR-targeted interventions for select patient populations.

3. Androgen Receptor-Mediated Immune Evasion and Tumor Microenvironment Reprogramming

AR is expressed by nearly all immune cells, and its activation affects both innate and adaptive immunity [

8,

31]. In immune cells, AR signaling has dual effects. While in neutrophils, AR activation stimulates pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α by regulating promoter activity [

32], in macrophages, it controls their polarization and differentiation toward the pro-tumor M2 phenotype [

33].

AR signaling also suppresses the activity of T and B cells [

32,

33,

34]. Activation of AR in peripheral T-cells inhibits their proliferation by limiting IL-2 signaling, reduces the differentiation of Th1 cells from naïve precursors, and decreases the expression of IL-12 by inhibiting STAT4 activation [

31]. Ultimately, AR signaling suppresses the expression of IFN-γ in T-cells by repressing lfng transcription [

35], and in B cells, inhibits their lymphopoiesis [

35].

Recent studies have implicated AR signaling as a critical regulator of the tumor microenvironment (TME) in melanoma. TME plays a pivotal role in melanoma progression and therapy resistance, particularly by modulating the immune landscape [

36,

37].

Studies based on the analysis of AR expression and activity using TCGA SKCM data show that AR expression in tumors correlates with exhausted CD8+ T cells [

38]. Increased AR activity is also negatively associated with immune cell infiltration in melanoma patients [

39]. In fact, patients with low levels of AR activity show improved response to ICB.

AR correlates with the upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules. While AR directly regulates B7-H3 in prostate cancer, its role in melanoma is less defined; nonetheless, B7-H3 is highly expressed and contributes to immune evasion [

40,

41,

42]. B7-H3 is a transmembrane glycoprotein implicated in suppressing anti-tumor immune responses and promoting immune tolerance [

43,

44]. In melanoma, its overexpression is associated with an immunosuppressive TME, characterized by reduced infiltration of CD8⁺ T lymphocytes and increased extracellular matrix collagen deposition. This profile defines the so-called “armored-cold” phenotype, characterized by high stromal density, immune exclusion, and a poor response to checkpoint inhibitors [

40]. Our group is currently exploring this potential regulatory axis.

AR influences innate immune evasion. Melanoma cells release soluble ligands such as the major histocompatibility complex class I chain-related protein A (MICA) and B (MICB), which bind the activating receptor NKG2D on NK cells, γδ T cells, and CD8+ T cells [

45,

46]. The binding induces receptor internalization and degradation, leading to immunosuppression [

47]. AR activation promotes MICA shedding through the upregulation of ADAM10 and the formation of an AR/ADAM10/β1-integrin complex [

26,

37]. Thereby abrogating immune cell activation and cytotoxicity.

A subset of melanoma cells display diminished antigen-presenting capacity, including the downregulation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II molecules and essential proteins required for the adequate functioning of the MHC, such as the transporter associated with antigen processing protein (TAP) [

39,

48,

49,

50]. Studies show significantly lower TAP1/2 expression in melanoma cells compared to melanocytes, with a corresponding decrease in HLA class I expression [

50]. These changes impair the recognition of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and hinder immune-mediated tumor clearance. This immune evasion may be driven, at least in part, by AR-mediated repression of MHCI pathway components

AR shapes the immunologic composition of the TME. Activation of the AR in immune cells has been linked to immunosuppression by altering the function and recruitment of various immune cell subsets, including T cells, B cells, and macrophages, within the TME [

28,

31]. In some cancers, such as prostate and breast cancers, elevated AR activity is associated with increased accumulation of T regulatory cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) [

51,

52]. However, little is known about AR expression and its effects on immune cell recruitment in melanoma.

Ma et al. addressed this gap by silencing AR in three melanoma cell lines and identifying a 155-gene signature associated with AR silencing. They then analyzed gene expression data from 469 cutaneous melanomas in the TCGA SKCM cohort. Tumors were stratified based on their similarity to the AR-silencing signature. Strikingly, melanomas positively associated with the AR-silencing signature exhibited higher infiltration of B cells, CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cells, and macrophages compared to those negatively associated with the AR-silencing signature [

23]. Moreover, these tumors showed enrichment for pro-inflammatory M1-like macrophages over immunosuppressive M2-like subsets, as well as increased presence of CD4⁺ memory T cells [

23]. These data indicate that AR actively represses anti-tumor immune infiltration and promotes a tolerogenic microenvironment.

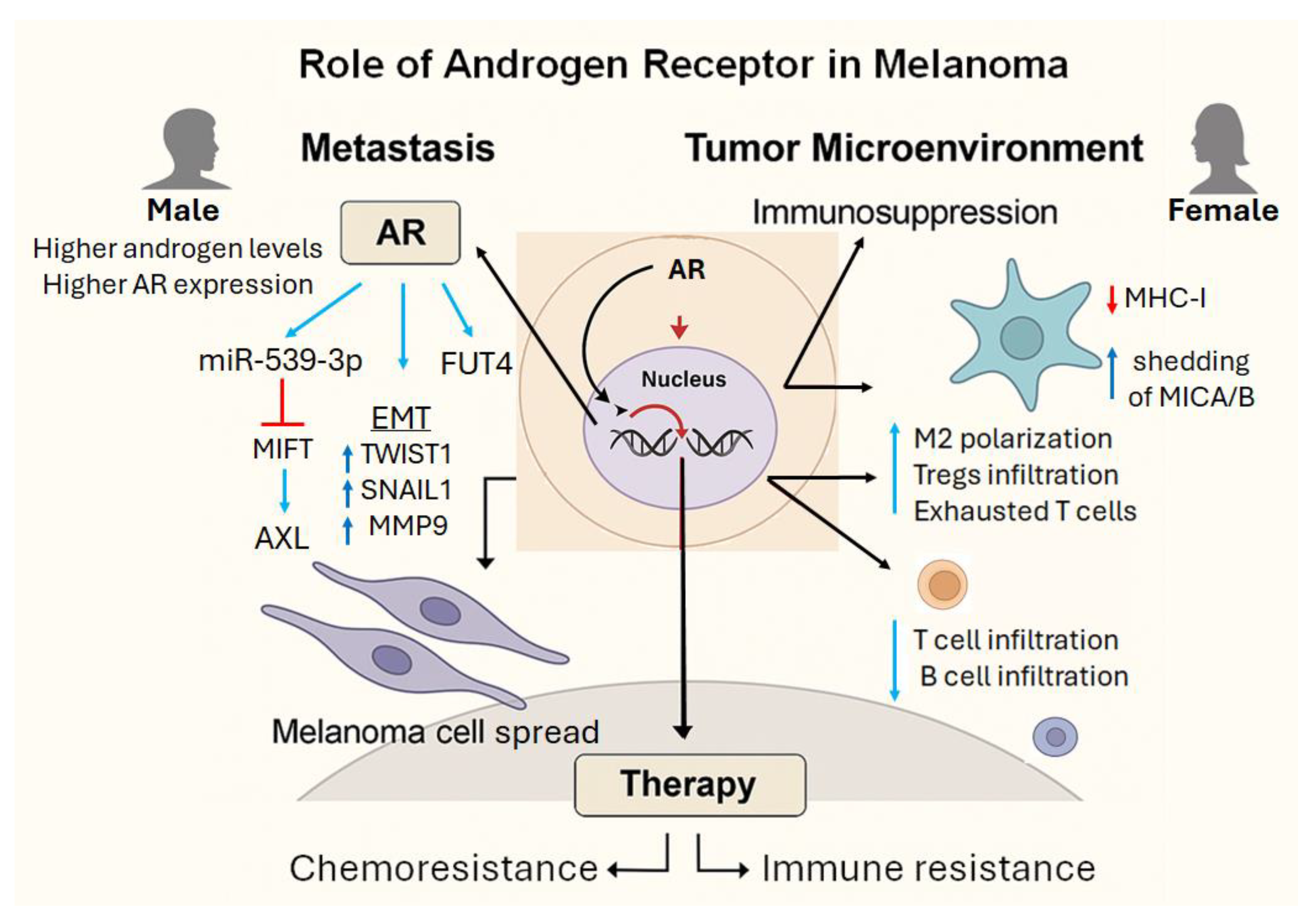

A schematic overview of AR-mediated mechanisms in melanoma metastasis and immunosuppression is shown in

Figure 1.

4. Androgen Receptor and Therapy Resistance

Resistance to targeted and immune-based therapies presents a significant clinical challenge in melanoma treatment. Multiple studies emphasize AR as a key factor in the development of resistance.

AR upregulation has become a crucial adaptive mechanism in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Increased AR activity maintains MAPK signaling despite the use of BRAF and MEK inhibitors, and fosters additional resistance pathways, including the activation of TGFβ and EGFR signaling. Additionally, AR stimulates SERPINE1 expression, which is associated with increased motility and metastasis. Clinical data show strong correlations between AR and SERPINE1 expression, especially in metastatic lesions [

7,

53].

Targeting AR reverses therapeutic resistance in preclinical models. AR inhibitors, such as AZD3514, ARCC4, and enzalutamide, decrease EGFR and SERPINE1 expression and reduce tumorigenicity in BRAF inhibitor-resistant melanoma cells [

7]. Pharmacologic AR blockade makes tumors more sensitive to BRAF/MEK inhibitors and improves regression in vivo, in both male and female models [

13].

AR also plays a critical role in resistance to immunotherapy. As previously discussed, AR-driven immunosuppression directly contributes to resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Androgen deprivation enhances the response to PD-1 blockade in murine melanoma models by increasing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and reinvigorating cytotoxic T cell activity [

46,

54,

55,

56]. These findings suggest that AR antagonism may synergize with ICIs, supporting the development of combinatorial therapeutic strategies.

Notably, sex-based differences in immunotherapy outcomes may also reflect differential AR signaling. Sex hormones influence the expression and function of checkpoint proteins such as PD-1 and PD-L1. Studies in melanoma models show that female mice respond more effectively than males to anti-PD-L1 therapy [

57], partly due to a greater reduction in Treg activity. Higher systemic androgen levels in males may enhance AR-driven immunosuppression, limiting immunotherapy efficacy, whereas lower androgen levels in females may favor more robust immune responses [

58].

However, clinical data are mixed. A pooled analysis of multiple trials reported that men with advanced melanoma demonstrated better immunotherapy responses than women, both short- and long-term, with higher peripheral immune activation observed in male patients [

59]. Although most mechanistic data on AR and immune suppression come from prostate cancer and other androgen-sensitive tumors, emerging studies in melanoma suggest a similar paradigm. This highlights the importance of sex-specific tumor biology in shaping immune responses and treatment outcomes.

Therapeutically, several AR-targeting strategies are under investigation. However, the systemic nature of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and its associated side effects, including metabolic disturbances, cardiovascular risk, and osteoporosis [

60,

61,

62,

63], limit its long-term applicability outside of prostate cancer. More selective pharmacologic interventions, including AR antagonists like enzalutamide, apalutamide, and darolutamide, directly block AR transcriptional activity [

64] and have shown efficacy in metastatic prostate cancer, though their use in melanoma remains investigational [

12,

65].

A summary of the AR-driven mechanisms and their implications in melanoma is provided in

Table 1.

5. Clinical Translation and Future Directions

Translational efforts to AR-targeted therapies in melanoma treatment are gaining momentum. For example, in a recent study, it was shown that patients with melanoma with high AR activity and treated with ICIs respond worse to the therapy compared with those patients with low AR activity [

39]. Furthermore, early-phase clinical trials investigating AR antagonists, in combination with ICIs, have shown encouraging signals, particularly in patients with AR-positive tumors [

66]. These trials indicate that inhibiting AR can synergize with immunotherapy, leading to improved outcomes for subsets of melanoma patients who have shown resistance to conventional treatments.

Beyond AR antagonism, novel agents such as selective AR degraders (SARDs) and proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) offer the potential for more comprehensive AR inhibition by receptor degradation [

67]. Early preclinical data indicate that PROTAC-mediated AR degradation not only reduces tumor growth but also enhances anti-tumor immunity [

67,

68]. Indeed, ARCC4 showed therapeutic effects in melanoma models [

7].

Targeting AR can also potentiate the efficacy of emerging therapies such as adoptive cell transfer and oncolytic virotherapy. Given AR’s role in modulating immune cell recruitment and function, its inhibition might reprogram the TME to favor these immune-based modalities.

Innovative approaches, including RNA interference (RNAi) strategies that silence AR expression, have shown potent anti-tumor effects in vitro and in vivo [

69]. Nanoparticle-based delivery systems may further improve the specificity and clinical feasibility of AR-directed RNA therapeutics.

On the other hand, as with other targeted therapies, prolonged AR inhibition may lead to adaptive resistance via compensatory signaling, genetic alterations, or microenvironmental reprogramming. Therefore, biomarker-driven approaches will be essential to maximize clinical benefit.

An additional therapeutic option is the potential use of Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators (SARMs) in the treatment of melanoma [

70]. Although this idea remains speculative, SARMs could represent a new class of agents that selectively inhibit AR signaling in tumor tissue with reduced systemic toxicity, depending on the AR isoform.

Tissue specificity of SARMs is a central feature of their pharmacological design. These compounds can differentially activate or inhibit the AR depending on the tissue context. In muscle and bone, SARMs often act as AR agonists, promoting anabolic effects, while in prostate and skin, certain SARMs can behave as antagonists or partial agonists, depending on their chemical structure and the expression of AR co-regulators and chromatin accessibility patterns in those tissues [

71,

72]. This tissue-specific modulation has been well described for agents such as enobosarm (GTx-024) and LGD-4033 (ligandrol), which show anabolic activity with limited effects on prostate tissue in preclinical and early-phase clinical studies [

73,

74].

In the context of melanoma, gene silencing or pharmacological inhibition of AR in melanoma cell lines suppresses proliferation and induces cellular senescence [

23]. Additionally, AR silencing causes chromosomal DNA breakage and the release of double-strand DNA into the cytosol, triggering the expression of the DNA sensor, STING. Mechanistically, AR silencing disassembles Ku70/Ku80 DNA repair proteins from the RNA Pol II complex, increasing DNA damage at transcription sites [

23].

In preclinical models, treatment with AR inhibitors suppresses the tumorigenicity of BRAFi-resistant melanoma cells and enhances anti-tumor immunity, particularly when combined with immune checkpoint blockade or BRAF/MEK inhibitors [

7,

13,

23]. Based on this rationale, SARMs with antagonistic properties in melanoma tissue might be developed to block AR signaling without the systemic endocrine side effects associated with ADT or full AR antagonists such as enzalutamide [

64].

Potential strategies include engineering SARMs with cutaneous-selective AR antagonism or combining SARMs with immunotherapies to enhance T cell infiltration, reduce immune checkpoint expression, and improve antigen presentation within the tumor microenvironment. However, caution is warranted. SARMs are not currently approved for cancer treatment, and their effects in melanoma have not been systematically studied. Furthermore, in AR-positive tumors, some SARMs can act as partial agonists or even stimulate AR activity depending on the tumor microenvironment, co-regulator landscape, and ligand concentration, potentially promoting tumor progression [

75].

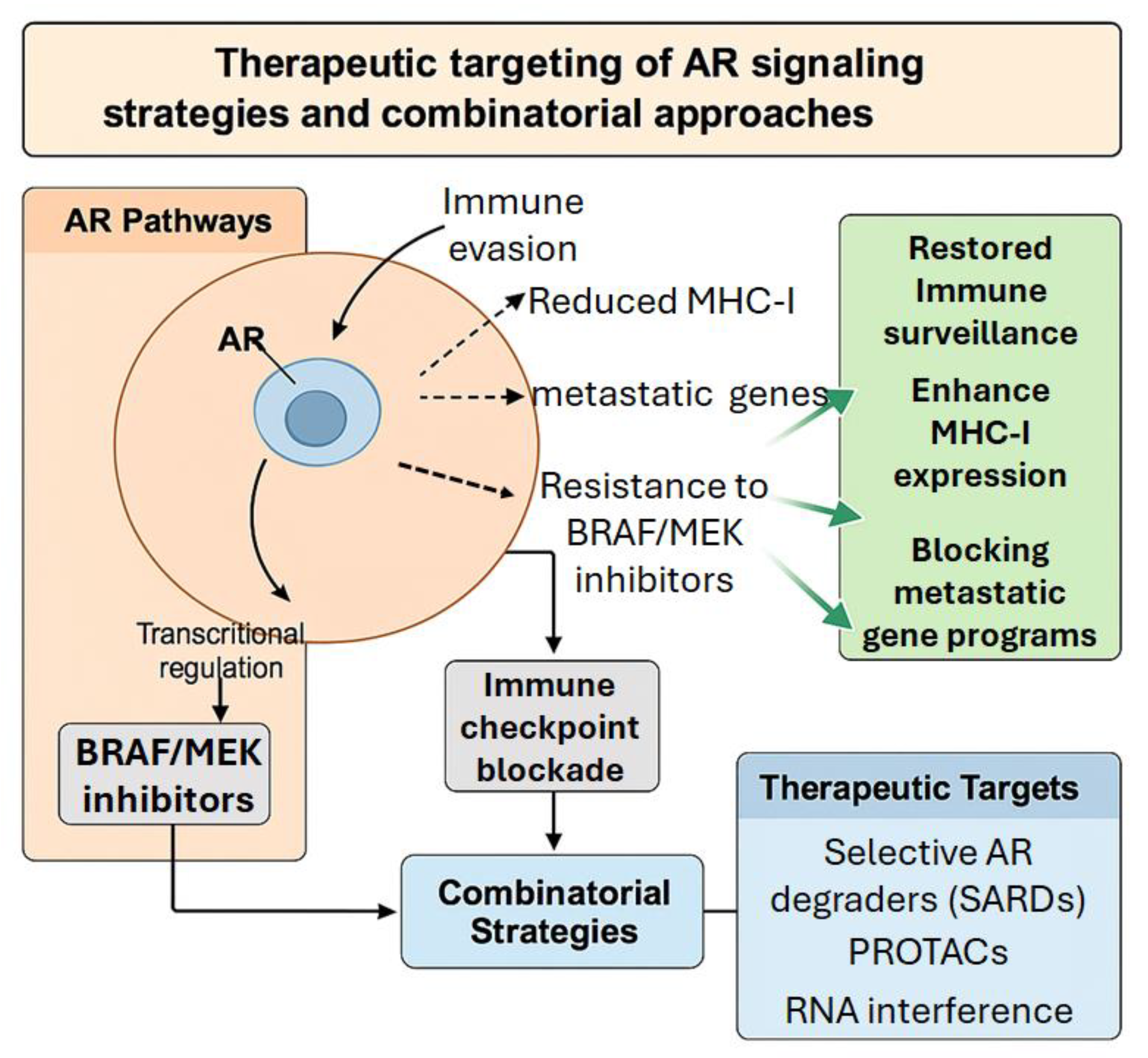

While some AR+ tumors with high AR activity respond well to ADT or AR antagonists, others exhibit intrinsic resistance, likely due to the heterogeneity of AR signaling and its complex interactions with other oncogenic pathways. This variability highlights the importance of precision medicine approaches that consider not only AR expression but also additional biomarkers, such as tumor mutational burden, immune checkpoint expression, and other factors that influence tumor behavior. Stratifying patients based on these criteria might enhance the therapeutic efficacy of AR-targeted therapies and help overcome the challenge of resistance by combining different therapeutic approaches (

Figure 2).

An additional consideration in the clinical application of AR-targeted therapies is the potential for sex-based differences in AR signaling. Epidemiological studies consistently indicate that melanoma is more aggressive and associated with a worse prognosis in men [

76], which can be influenced by differential AR signaling. Tailoring AR-targeted therapies to account for these sex-specific differences might provide a therapeutic advantage, addressing the unique challenges faced by male and female patients. Gender-specific treatment strategies can optimize the efficacy of AR inhibitors, reducing the likelihood of resistance and enhancing overall patient outcomes.

6. Conclusions

The androgen receptor is a critical regulator of melanoma aggressiveness, influencing metastasis, immune evasion, and therapy resistance.

Mechanistic studies reveal that AR orchestrates a pro-tumorigenic program through transcriptional control of EMT-related genes, suppression of antigen presentation, induction of immunosuppressive cytokines, and persistence of survival signaling. These findings not only highlight AR as a biomarker of disease progression but also establish it as a viable therapeutic target.

The development of AR antagonists, degraders, and RNA-based inhibitors opens the door for integrated treatment approaches that combine AR-targeted therapies with existing immunotherapies and kinase inhibitors. Furthermore, acknowledging sex-specific differences in AR signaling provides an opportunity to optimize treatment strategies and personalize care.

Future research should focus on refining biomarkers of AR activity, stratifying patients based on AR expression and downstream signaling signatures, and designing clinical trials that evaluate the efficacy of AR-targeted agents across diverse patient populations. A comprehensive understanding of AR’s role in melanoma will enable the translation of these insights into tangible clinical benefit.

The integration of AR inhibitors into the therapeutic landscape for melanoma presents a promising strategy to complement existing treatments and potentially overcome resistance to chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. Ongoing clinical trials will be pivotal in defining the optimal combinations, sequencing, and patient selection criteria for these therapies. Thus, further studies are needed to refine our understanding of how AR interacts with melanoma subtypes, tumor microenvironment components, and immune modulators, which will be critical for maximizing the clinical benefit of AR targeting.

Overall, AR represents a compelling and underexplored axis in melanoma pathogenesis and therapy. Leveraging this pathway might enhance current treatment paradigms and improve outcomes for patients with advanced and resistant disease.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in writing and editing and approved the final version for publication.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AR |

Androgen receptor |

| ICIs |

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors |

| UV |

Ultraviolet |

| EMT |

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| TWIST1 |

Twist-related protein |

| SNAI1 |

Zinc finger protein SNAI1 |

| MMPs |

Matrix Metalloproteinases |

| ICAM1 |

Intracellular adhesion molecule 1 |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin 6 |

| FUT4 |

Fucosyltransferase 4 |

| AJs |

Adherence junctions |

| TCGA SKCM |

The Cancer Genome Atlas human skin cutaneous melanoma |

| TME |

Tumor Microenvironment |

| MICA |

Major histocompatibility complex class I chain-related protein A |

| MICB |

Major histocompatibility complex class I chain-related protein B |

| MHC |

Major histocompatibility complex |

| TAP |

Transporter associated with antigen processing protein |

| Tregs |

T regulatory cells |

| MDSCs |

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| ADT |

Androgen deprivation therapy |

| SARDs |

Selective AR degraders |

| PROTACs |

Proteolysis-targeting chimeras |

| RNAi |

RNA interface |

| SARMs |

Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators |

References

- Bellenghi M, Puglisi R, Pontecorvi G, De Feo A, Carè A, Mattia G: Sex and Gender Disparities in Melanoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 1819. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sood S, Jayachandiran R, Pandey S: Current Advancements and Novel Strategies in the Treatment of Metastatic Melanoma. Integrative Cancer Therapies 2021, 20, 1534735421990078. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancianti ML, Herlyn M: Tumor progression in melanoma: the biology of epidermal melanocytes in vitro. Carcinog Compr Surv 1989, 11, 369–386.

- Xu J, Mu S, Wang Y, Yu S, Wang Z: Recent advances in immunotherapy and its combination therapies for advanced melanoma: a review. Frontiers in Oncology 2024, 14.

- Davey, R.A.; Grossmann, M. Androgen Receptor Structure, Function and Biology: From Bench to Bedside. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2016, 37, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Samarkina, A.; Youssef, M.K.; Ostano, P.; Ghosh, S.; Ma, M.; Tassone, B.; Proust, T.; Chiorino, G.; Levesque, M.P.; Goruppi, S.; et al. Androgen receptor is a determinant of melanoma targeted drug resistance. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Batalla I, Vargas-Delgado ME, von Amsberg G, Janning M, Loges S: Influence of Androgens on Immunity to Self and Foreign: Effects on Immunity and Cancer. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1184. [CrossRef]

- Jamroze A, Chatta G, Tang DG: Androgen receptor (AR) heterogeneity in prostate cancer and therapy resistance. Cancer Letters 2021, 518, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Zarif, J.C.; Miranti, C.K. The importance of non-nuclear AR signaling in prostate cancer progression and therapeutic resistance. Cell. Signal. 2016, 28, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brawer MK: Androgen deprivation therapy: a cornerstone in the treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Rev Urol 2004, 6 (Suppl 8), S3–9.

- Liu, Q.; Adhikari, E.; Lester, D.K.; Fang, B.; Johnson, J.O.; Tian, Y.; Mockabee-Macias, A.T.; Izumi, V.; Guzman, K.M.; White, M.G.; et al. Androgen drives melanoma invasiveness and metastatic spread by inducing tumorigenic fucosylation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellano CP, White MG, Andrews MC, Chelvanambi M, Witt RG, Daniele JR, Titus M, McQuade JL, Conforti F, Burton EM et al. : Androgen receptor blockade promotes response to BRAF/MEK-targeted therapy. Nature 2022, 606, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Ou Z, Sun Y, Yeh S, Wang X, Long J, Chang C: Androgen receptor promotes melanoma metastasis via altering the miRNA-539-3p/USP13/MITF/AXL signals. Oncogene 2017, 36, 1644–1654. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stidham KR, Johnson JL, Seigler HF: Survival superiority of females with melanoma. A multivariate analysis of 6383 patients exploring the significance of gender in prognostic outcome. Arch Surg 1994, 129, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, E.; Nijsten, T.E.C.; Visser, O.; Bastiaannet, E.; van Hattem, S.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L.; Coebergh, J.-. .-W.W. Superior survival of females among 10 538 Dutch melanoma patients is independent of Breslow thickness, histologic type and tumor site. Ann. Oncol. 2007, 19, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosse A, Collette S, Suciu S, Nijsten T, Patel PM, Keilholz U, Eggermont AM, Coebergh JW, de Vries E: Sex is an independent prognostic indicator for survival and relapse/progression-free survival in metastasized stage III to IV melanoma: a pooled analysis of five European organisation for research and treatment of cancer randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol 2013, 31, 2337–2346.

- Balch, C.M.; Soong, S.-J.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Reintgen, D.S.; Cascinelli, N.; Urist, M.; McMasters, K.M.; Ross, M.I.; Kirkwood, J.M.; Atkins, M.B.; et al. Prognostic Factors Analysis of 17,600 Melanoma Patients: Validation of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Melanoma Staging System. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 3622–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, C.M.; Pandeya, N.; Miranda-Filho, A.; Rosenberg, P.S.; Whiteman, D.C. Does Sex Matter? Temporal Analyses of Melanoma Trends among Men and Women Suggest Etiologic Heterogeneity. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 145, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Switzer B, Puzanov I, Skitzki JJ, Hamad L, Ernstoff MS: Managing Metastatic Melanoma in 2022: A Clinical Review. JCO Oncology Practice 2022, 18, 335–351. [CrossRef]

- Castellani G, Buccarelli M, Arasi MB, Rossi S, Pisanu ME, Bellenghi M, Lintas C, Tabolacci C: BRAF Mutations in Melanoma: Biological Aspects, Therapeutic Implications, and Circulating Biomarkers. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15(16).

- Anna B, Blazej Z, Jacqueline G, Andrew CJ, Jeffrey R, Andrzej S: Mechanism of UV-related carcinogenesis and its contribution to nevi/melanoma. Expert Rev Dermatol 2007, 2, 451–469. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, M.; Ghosh, S.; Tavernari, D.; Katarkar, A.; Clocchiatti, A.; Mazzeo, L.; Samarkina, A.; Epiney, J.; Yu, Y.-R.; Ho, P.-C.; et al. Sustained androgen receptor signaling is a determinant of melanoma cell growth potential and tumorigenesis. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, K.-T.; Chiou, S.-S.; Hsu, S.-H. Recent Advances in Transcription Factors Biomarkers and Targeted Therapies Focusing on Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition. Cancers 2023, 15, 3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatiwada P, Kannan A, Malla M, Dreier M, Shemshedini L: Androgen up-regulation of Twist1 gene expression is mediated by ETV1. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8921. [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino C, D’Angiolo R, Gentile G, Giovannelli P, Perillo B, Migliaccio A, Castoria G, Di Donato M: The Androgen Regulation of Matrix Metalloproteases in Prostate Cancer and Its Related Tumor Microenvironment. Endocrines 2023, 4, 350–365. [CrossRef]

- Larsson P, Syed Khaja AS, Semenas J, Wang T, Sarwar M, Dizeyi N, Simoulis A, Hedblom A, Wai SN, Ødum N et al. : The functional interlink between AR and MMP9/VEGF signaling axis is mediated through PIP5K1α/pAKT in prostate cancer. International Journal of Cancer 2020, 146, 1686–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao X, Thrasher JB, Pelling J, Holzbeierlein J, Sang QX, Li B: Androgen stimulates matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression in human prostate cancer. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 1656–1663. [CrossRef]

- Singh N, Khatib J, Chiu C-Y, Lin J, Patel TS, Liu-Smith F: Tumor Androgen Receptor Protein Level Is Positively Associated with a Better Overall Survival in Melanoma Patients. Genes 2023, 14, 345. [CrossRef]

- Morgese, F.; Sampaolesi, C.; Torniai, M.; Conti, A.; Ranallo, N.; Giacchetti, A.; Serresi, S.; Onofri, A.; Burattini, M.; Ricotti, G.; et al. Gender Differences and Outcomes in Melanoma Patients. Oncol. Ther. 2020, 8, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai J-J, Lai K-P, Zeng W, Chuang K-H, Altuwaijri S, Chang C: Androgen Receptor Influences on Body Defense System via Modulation of Innate and Adaptive Immune Systems: Lessons from Conditional AR Knockout Mice. The American Journal of Pathology 2012, 181, 1504–1512. [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft GS, Mills SJ: Androgen receptor-mediated inhibition of cutaneous wound healing. J Clin Invest 2002, 110, 615–624. [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Díaz, M.; Strickland, A.B.; Keselman, A.; Heller, N.M. Androgen and Androgen Receptor as Enhancers of M2 Macrophage Polarization in Allergic Lung Inflammation. J. Immunol. 2018, 201, 2923–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissick, H. T.; Sanda, M. G.; Dunn, L. K.; Pellegrini, K. L.; On, S. T.; Noel, J. K.; Arredouani, M. S. Androgens alter T-cell immunity by inhibiting T-helper 1 differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Am. 2014, 111, 9887–9892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Polesso, F.; Wang, C.; Sehrawat, A.; Hawkins, R.M.; Murray, S.E.; Thomas, G.V.; Caruso, B.; Thompson, R.F.; Wood, M.A.; et al. Androgen receptor activity in T cells limits checkpoint blockade efficacy. Nature 2022, 606, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva J, Herlyn M: Melanoma and the tumor microenvironment. Curr Oncol Rep 2008, 10, 439–446. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somasundaram R, Herlyn M, Wagner SN: The role of tumor microenvironment in melanoma therapy resistance. Melanoma Manag 2016, 3, 23–32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang C, Jin J, Yang Y, Sun H, Wu L, Shen M, Hong X, Li W, Lu L, Cao D et al. : Androgen receptor-mediated CD8(+) T cell stemness programs drive sex differences in antitumor immunity. Immunity 2022, 55, 1268–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu YM, Zhao F, Graff JN, Chen C, Zhao X, Thomas GV, Wu H, Kardosh A, Mills GB, Alumkal JJ et al.: Androgen receptor activity inversely correlates with immune cell infiltration and immunotherapy response across multiple cancer lineages. bioRxiv 2024.

- Shen, B.; Mei, J.; Xu, R.; Cai, Y.; Wan, M.; Zhou, J.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Y. B7-H3 is associated with the armored-cold phenotype and predicts poor immune checkpoint blockade response in melanoma. Pathol. - Res. Pr. 2024, 256, 155267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flem-Karlsen K, Tekle C, Andersson Y, Flatmark K, Fodstad Ø, Nunes-Xavier CE: Immunoregulatory protein B7-H3 promotes growth and decreases sensitivity to therapy in metastatic melanoma cells. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2017, 30, 467–476. [CrossRef]

- Nunes-Xavier, C.E.; Kildal, W.; Kleppe, A.; Danielsen, H.E.; Wæhre, H.; Llarena, R.; Mælandsmo, G.M.; Fodstad, Ø.; Pulido, R.; López, J.I. Immune checkpoint B7-H3 protein expression is associated with poor outcome and androgen receptor status in prostate cancer. Prostate 2021, 81, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroff, M.G.; Kharatyan, E.; Torry, D.S.; Holets, L. The Immunomodulatory Proteins B7-DC, B7-H2, and B7-H3 Are Differentially Expressed across Gestation in the Human Placenta. Am. J. Pathol. 2005, 167, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmeyer KA, Ray A, Zang X: The contrasting role of B7-H3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 10277–10278. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passarelli A, Mannavola F, Stucci LS, Tucci M, Silvestris F: Immune system and melanoma biology: a balance between immunosurveillance and immune escape. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 106132–106142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing S, Ferrari de Andrade L: NKG2D and MICA/B shedding: a ‘tag game’ between NK cells and malignant cells. Clin Transl Immunology 2020, 9, e1230. [CrossRef]

- Zingoni A, Molfetta R, Fionda C, Soriani A, Paolini R, Cippitelli M, Cerboni C, Santoni A: NKG2D and Its Ligands: “One for All, All for One”. Frontiers in Immunology, 2018.

- Dhatchinamoorthy K, Colbert JD, Rock KL: Cancer Immune Evasion Through Loss of MHC Class I Antigen Presentation. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, Volume 12 - 2021.

- Chesner, L.N.; Polesso, F.; Graff, J.N.; Hawley, J.E.; Smith, A.K.; Lundberg, A.; Das, R.; Shenoy, T.; Sjöström, M.; Zhao, F.; et al. Androgen Receptor Inhibition Increases MHC Class I Expression and Improves Immune Response in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2024, 15, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.; Dong, J.; Wu, Y.; Shen, G.-X.; Tu, Y.-T. Restoration of the Expression of Transports Associated with Antigen Processing in Human Malignant Melanoma Increases Tumor-Specific Immunity. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 1991–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consiglio CR, Udartseva O, Ramsey KD, Bush C, Gollnick SO: Enzalutamide, an Androgen Receptor Antagonist, Enhances Myeloid Cell-Mediated Immune Suppression and Tumor Progression. Cancer Immunol Res 2020, 8, 1215–1227. [CrossRef]

- van Rooijen JM, Qiu S-Q, Timmer-Bosscha H, van der Vegt B, Boers JE, Schröder CP, de Vries EGE: Androgen receptor expression inversely correlates with immune cell infiltration in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive breast cancer. European Journal of Cancer 2018, 103, 52–60. [CrossRef]

- Klein RM, Bernstein D, Higgins SP, Higgins CE, Higgins PJ: SERPINE1 expression discriminates site-specific metastasis in human melanoma. Exp Dermatol 2012, 21, 551–554. [CrossRef]

- Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Is Modulated by Androgen Receptor. Cancer Discov 2022, 12, 1405. [CrossRef]

- Gamat M, McNeel DG: Androgen deprivation and immunotherapy for the treatment of prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2017, 24, T297–t310. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallos, M.C.; Obradovic, A.Z.; McCann, P.; Chowdhury, N.; Pratapa, A.; Aggen, D.H.; Gaffney, C.; Autio, K.A.; Virk, R.K.; De Marzo, A.M.; et al. Androgen Deprivation Therapy Drives a Distinct Immune Phenotype in Localized Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 5218–5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin PY, Sun L, Thibodeaux SR, Ludwig SM, Vadlamudi RK, Hurez VJ, Bahar R, Kious MJ, Livi CB, Wall SR et al. : B7-H1-dependent sex-related differences in tumor immunity and immunotherapy responses. J Immunol 2010, 185, 2747–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubbels Bupp MR, Jorgensen TN: Androgen-Induced Immunosuppression. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 794. [CrossRef]

- Conforti, F.; Pala, L.; Bagnardi, V.; De Pas, T.; Martinetti, M.; Viale, G.; Gelber, R.D.; Goldhirsch, A. Cancer immunotherapy efficacy and patients' sex: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienz, M.; Saad, F. Androgen-deprivation therapy and bone loss in prostate cancer patients: a clinical review. BoneKEy Rep. 2015, 4, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Tripathi, A.; Pieczonka, C.; Cope, D.; McNatty, A.; Logothetis, C.; Guise, T. Bone health effects of androgen-deprivation therapy and androgen receptor inhibitors in patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020, 24, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine GN, D’Amico AV, Berger P, Clark PE, Eckel RH, Keating NL, Milani RV, Sagalowsky AI, Smith MR, Zakai N: Androgen-deprivation therapy in prostate cancer and cardiovascular risk: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, and American Urological Association: endorsed by the American Society for Radiation Oncology. CA Cancer J Clin 2010, 60, 194–201.

- Kim, J.; Freeman, K.; Ayala, A.; Mullen, M.; Sun, Z.; Rhee, J.-W. Cardiovascular Impact of Androgen Deprivation Therapy: from Basic Biology to Clinical Practice. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 25, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattrini, C.; Caffo, O.; De Giorgi, U.; Mennitto, A.; Gennari, A.; Olmos, D.; Castro, E. Apalutamide, Darolutamide and Enzalutamide for Nonmetastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer (nmCRPC): A Critical Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert C, Lebbé C, Lesimple T, Lundström E, Nicolas V, Gavillet B, Crompton P, Baroudjian B, Routier E, Lejeune FJ: Phase I Study of Androgen Deprivation Therapy in Combination with Anti–PD-1 in Melanoma Patients Pretreated with Anti–PD-1. Clinical Cancer Research 2023, 29, 858–865. [CrossRef]

- Ager CR, Obradovic A, McCann P, Chaimowitz M, Wang ALE, Shaikh N, Shah P, Pan S, Laplaca CJ, Virk RK et al.: Neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy with or without Fc-enhanced non-fucosylated anti-CTLA-4 (BMS-986218) in high risk localized prostate cancer: a randomized phase 1 trial. medRxiv 2024.

- Fang, Q.; Cole, R.N.; Wang, Z. Mechanisms and targeting of proteosome-dependent androgen receptor degradation in prostate cancer. 2022, 10, 366–376.

- Mannion, J.; Gifford, V.; Bellenie, B.; Fernando, W.; Garcia, L.R.; Wilson, R.; John, S.W.; Udainiya, S.; Patin, E.C.; Tiu, C.; et al. A RIPK1-specific PROTAC degrader achieves potent antitumor activity by enhancing immunogenic cell death. Immunity 2024, 57, 1514–1532.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiemann K, Rossi JJ: RNAi-based therapeutics-current status, challenges and prospects. EMBO Mol Med 2009, 1, 142–151. [CrossRef]

- Solomon ZJ, Mirabal JR, Mazur DJ, Kohn TP, Lipshultz LI, Pastuszak AW: Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators: Current Knowledge and Clinical Applications. Sex Med Rev 2019, 7, 84–94. [CrossRef]

- Narayanan R, Coss CC, Dalton JT: Development of selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs). Mol Cell Endocrinol 2018, 465, 134–142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao W, Kearbey JD, Nair VA, Chung K, Parlow AF, Miller DD, Dalton JT: Comparison of the Pharmacological Effects of a Novel Selective Androgen Receptor Modulator, the 5α-Reductase Inhibitor Finasteride, and the Antiandrogen Hydroxyflutamide in Intact Rats: New Approach for Benign Prostate Hyperplasia. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 5420–5428.

- Dalton JT, Barnette KG, Bohl CE, Hancock ML, Rodriguez D, Dodson ST, Morton RA, Steiner MS: The selective androgen receptor modulator GTx-024 (enobosarm) improves lean body mass and physical function in healthy elderly men and postmenopausal women: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2011, 2, 153–161.

- Basaria S, Collins L, Dillon EL, Orwoll K, Storer TW, Miciek R, Ulloor J, Zhang A, Eder R, Zientek H et al. : The safety, pharmacokinetics, and effects of LGD-4033, a novel nonsteroidal oral, selective androgen receptor modulator, in healthy young men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2013, 68, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan R, Mohler ML, Bohl CE, Miller DD, Dalton JT: Selective androgen receptor modulators in preclinical and clinical development. Nucl Recept Signal 2008, 6, e010.

- El Sharouni MA, Witkamp AJ, Sigurdsson V, van Diest PJ, Louwman MWJ, Kukutsch NA: Sex matters: men with melanoma have a worse prognosis than women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019, 33, 2062–2067. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).