Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Therapeutic Approaches

2.1. Genome Editing Approaches

2.2. Epigenetic Drugs

2.3. Therapeutic Vaccines

2.4. Natural Compounds & Phytochemicals

| Compound | Natural Source | Mechanism of Action | HPV-related Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curcumin | Turmeric (Curcuma longa) | Inhibits E6/E7 expression; induces apoptosis; modulates NF-κB signaling | Suppresses viral oncogene expression; anti-proliferative |

| EGCG | Green tea (Camellia sinensis) | Antioxidant activity; inhibition of DNA methylation; cell cycle arrest | Inhibits HPV-positive cell growth; sensitizes to therapy |

| Resveratrol | Grapes, berries | Downregulates E6/E7; induces autophagy and apoptosis | Inhibits HPV-driven transformation; enhances immune responses |

| Withaferin A | Withania somnifera | Downregulates E6/E7; restores p53 activity | Reduces HPV oncogene activity; promotes apoptosis |

| Berberine | Berberis species | Induces mitochondrial dysfunction; increases ROS; causes cell cycle arrest | Triggers apoptosis in HPV-transformed cervical cancer cells |

| Fig latex | Ficus carica | Downregulates HPV E6/E7; reactivates p53/Rb; induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis; modulates immune-related gene expression | Selectively inhibits proliferation, migration, and invasion of HPV-positive cervical cancer cells; enhances antigen presentation and immune recognition |

3. Drug Repurposing & Combination Therapies

4. Patient-Derived Organoids & Functional Screening

5. Integration with Precision Oncology

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

References

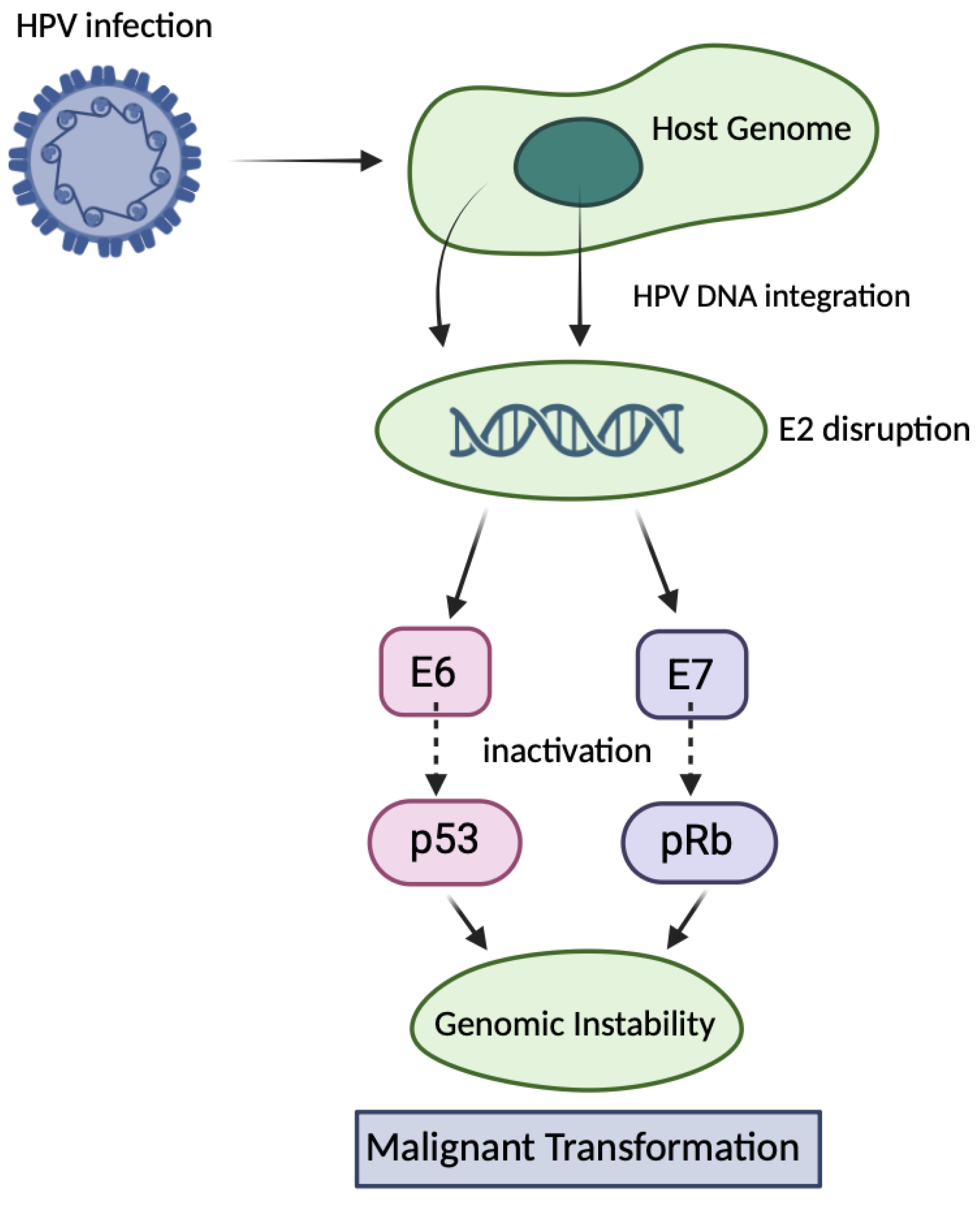

- A, Kundu R. Human papillomavirus E6 and E7: The cervical cancer hallmarks and targets for therapy. Front Microbiol. 2020;10:3116. [CrossRef]

- Doorbar, J. The evolving immunobiology of human papillomavirus infection. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003, 3, B33–B44. [Google Scholar]

- Ronco, LV. HPV E6 proteins: Repertoire of functions from replication to immune modulation. Viruses. 2017, 9, 344. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira EM, et al. HPV E7 protein down-regulates MHC class I surface expression. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0116775.

- Jaiswal R, Banerjee D. Tumor-associated inflammation and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2021, 40, 361–373.

- Teffera ZH, et al. Efficacy of a novel high-risk HPV-16/18 therapeutic vaccine in treating cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer in a clinical trial: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Acad Sci J. 2024;6:52.

- Trimble, CL. Therapeutic HPV vaccines: Targeting the immune escape. Gynecol Oncol. 2010, 116, 486–490. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, M. Immune responses to human papillomavirus. Vaccine. 2006;24(Suppl 1):S16–S22.

- Einstein MH, et al. Cervical cancer recurrence and immune status. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007, 56, 389–395.

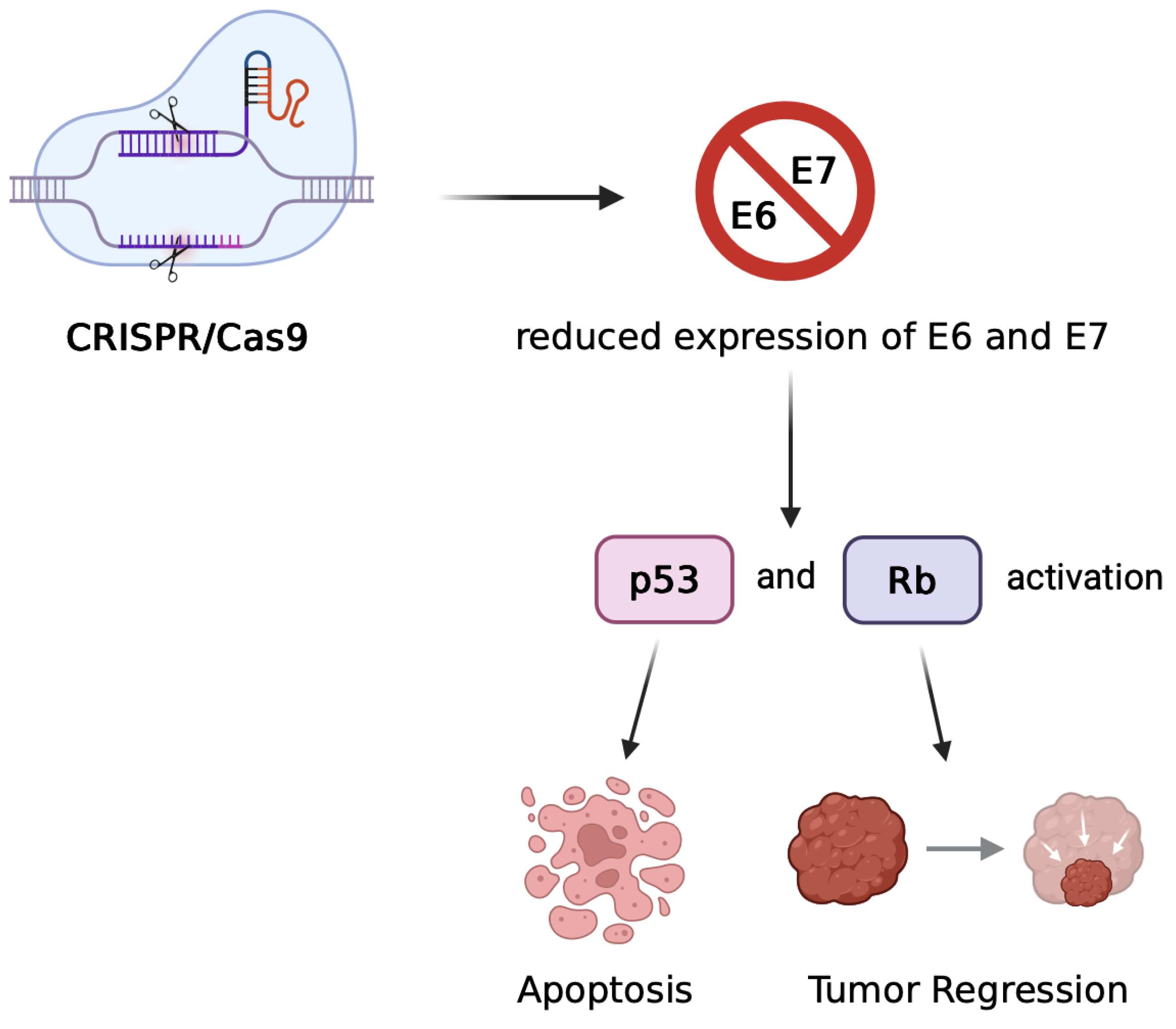

- Zheng Y, Srisuttee R, Jiang Y, et al. Disruption of HPV16-E7 by CRISPR/Cas system induces apoptosis and growth inhibition in HPV16 positive human cervical cancer cells. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:612823. [CrossRef]

- Jubair L, Fallaha S, McMillan NAJ. Systemic delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 targeting HPV oncogenes is effective at eliminating established tumors. Mol Ther. 2019, 27, 2091–2099. [CrossRef]

- Xu Q, Chen Y, Jin Y, Wang Z, Dong H, Kaufmann AM, et al. Advanced nanomedicine for high-risk HPV-driven head and neck cancer. Viruses. 2022, 14, 2824. [CrossRef]

- Khairkhah N, Bolhassani A, Najafipour R. Current and future direction in treatment of HPV-related cervical disease. J Mol Med (Berl). 2022, 100, 829–845. [CrossRef]

- Lu Z, Haghollahi S, Afzal M. Potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of HPV-associated malignancies. Cancers (Basel). 2024, 16, 3474. [CrossRef]

- Zhen S, Qiang R, Lu J, Tuo X, Yang X, Li X. CRISPR/Cas9-HPV-liposome enhances antitumor immunity and treatment of HPV infection-associated cervical cancer. J Med Virol. 2023, 95, e28144. [CrossRef]

- Dadar M, Chakraborty S, Dhama K, et al. Advances in designing and developing vaccines, drugs and therapeutic approaches to counter human papilloma virus. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2478. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Wang J, Yang W, et al. Precision therapeutic targets for HPV-positive cancers: an overview and new insights. Infect Agents Cancer. 2025;20:17. [CrossRef]

- Wei Y, Zhao Z, Ma X. Description of CRISPR-Cas9 development and its prospects in human papillomavirus-driven cancer treatment. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1037124. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy EM, Kornepati AVR, Goldstein M, et al. Inactivation of the human papillomavirus E6 or E7 gene in cervical carcinoma cells using CRISPR/Cas9. J Virol. 2014, 88, 11965–11972. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Han X, Yuan J, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeting of HPV oncogenes E6 and E7 induces apoptosis in cervical cancer cells. Biotechnol Lett. 2020, 42, 797–807.

- Zhang X-H, Tee LY, Wang X-G, Huang Q-S, Yang S-H. Off-target effects in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome engineering. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 467–484. [CrossRef]

- Autin P, Blanquart C, Fradin D. Epigenetic Drugs for Cancer and microRNAs: A Focus on Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors. Cancers. 2019;11:1530. [CrossRef]

- Burkitt K, Saloura V. Epigenetic modifiers as novel therapeutic targets and a systematic review of clinical studies investigating epigenetic inhibitors in head and neck cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13, 5241. [CrossRef]

- Bagarazzi ML, Yan J, Morrow MP, Shen X, Parker RL, Lee JC, et al. Immunotherapy against HPV16/18 generates potent TH1 and cytotoxic cellular immune responses. Sci Transl Med. 2012, 4, 155ra138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimble CL, Morrow MP, Kraynyak KA, Shen X, Dallas M, Yan J, et al. Safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of VGX-3100, a therapeutic synthetic DNA vaccine targeting human papillomavirus 16 and 18 E6 and E7 proteins for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2015, 386, 2078–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalley Rumfield C, Roller N, Pellom ST, Schlom J, Jochems C. Therapeutic vaccines for HPV-associated malignancies. Immunotargets Ther. [CrossRef]

- Young MR, Rodriguez L, Hadden W, Ghosh S, Shrivastava S, Yang L, et al. PRGN-2012, a novel gorilla adenovirus-based immunotherapy, provides the first treatment that leads to complete and durable responses in recurrent respiratory papillomatosis patients. J Clin Oncol. 2024, 42(LBA6015). [CrossRef]

- Maher DM, et al. Curcumin inhibits human papillomavirus oncoproteins and induces apoptosis in cervical cancer cells. Gynecol Oncol. 2011, 123, 376–382.

- Musarra-Pizzo M, Pennisi R, Ben-Amor I, Mandalari G, Sciortino MT. Antiviral Activity Exerted by Natural Products against Human Viruses. Viruses. 2021, 13, 828. [CrossRef]

- Franconi R, Massa S, Paolini F, Vici P, Venuti A. Plant-Derived Natural Compounds in Genetic Vaccination and Therapy for HPV-Associated Cancers. Cancers. 2020, 12, 3101. [CrossRef]

- Einbond LS, Zhou J, Wu H, et al. A novel cancer preventative botanical mixture, TriCurin, inhibits viral transcripts and the growth of W12 cervical cells harbouring extrachromosomal or integrated HPV16 DNA. Br J Cancer. 2021;124:901–913. [CrossRef]

- Massa S, Pagliarello R, Paolini F, Venuti A. Natural Bioactives: Back to the Future in the Fight against Human Papillomavirus? A Narrative Review. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 1465. [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari A, Le Gresley A, Naughton D, Kuhnert N, Sirbu D, Ashrafi GH. Biological activities of Ficus carica latex for potential therapeutics in Human Papillomavirus (HPV) related cervical cancers. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 1013 Published 2019 Jan 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakir MO, Bilge U, Naughton D, Ashrafi GH. Ficus carica Latex Modulates Immunity-Linked Gene Expression in Human Papillomavirus Positive Cervical Cancer Cell Lines: Evidence from RNA Seq Transcriptome Analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 13646. [CrossRef]

- Cakir MO, Bilge U, Ghanbari A, Ashrafi GH. Regulatory Effect of Ficus carica Latex on Cell Cycle Progression in Human Papillomavirus-Positive Cervical Cancer Cell Lines: Insights from Gene Expression Analysis. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023, 16, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu M, Lee E, Choi J, Kim H. Repurposing anthelmintic drug niclosamide to treat HPV-positive cancers. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 4777–4787.

- Hildebrand J, Smith A, Johnson L, Brown K. Lopinavir inhibits proliferation of HPV-positive cervical cancer cells. Gynecol Oncol. 2016, 141, 441–447. [CrossRef]

- Trimble CL, Morrow M, Kraynyak K, Amante D. Immunotherapy and combination strategies for HPV-associated cancers. Cancer Immunol Res. 2021, 9, 377–384.

- Sachs N, de Ligt J, Kopper O, Gogola E, Bounova G, Weeber F,... Clevers H. A living biobank of breast cancer organoids captures disease heterogeneity. Cell. 2018;172(1-2):373–386.e10. [CrossRef]

- Driehuis E, Kolders S, Spelier S, Lõhmussaar K, Willems SM, Devriese LA, de Bree R, de Ruiter EJ, Korving J, Begthel H, van Es JH, Clevers H, van Boxtel R. Human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal cancer organoids for drug screening and therapy development. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 852–871.

- Koppers C, Rinkes IHM, van den Brink GR. Patient-derived organoids from cervical cancer as a platform for precision medicine. Mol Oncol. 2022, 16, 661–676. [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic and molecular characterization of cervical cancer. Nature. 2017, 543, 378–384. [CrossRef]

- Duffy MJ, et al. Precision oncology: Biomarkers, companion diagnostics and therapeutic targets. Mol Aspects Med. 2021;72:100832. [CrossRef]

- Topol, EJ. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteva A, Robicquet A, Ramsundar B, et al. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nat Med. 2021, 27, 766–776. [CrossRef]

- Gao C, Wu P, Yu L, et al. The application of CRISPR/Cas9 system in cervical carcinogenesis. Cancer Gene Ther. 2022;29:466–474. [CrossRef]

- Inturi R, Jemth P. CRISPR/Cas9-based inactivation of human papillomavirus oncogenes E6 or E7 induces senescence in cervical cancer cells. Virology. 2021;562:92–102. [CrossRef]

- Kermanshahi AZ, Ebrahimi F, Taherpoor A, et al. HPV-driven cancers: a looming threat and the potential of CRISPR/Cas9 for targeted therapy. Virol J. 2025;22:156. [CrossRef]

- Kaushal JB, et al. Repurposing Niclosamide for Targeting Pancreatic Cancer by Inhibiting Hh/Gli Non-Canonical Axis of Gsk3β. Cancers. 2021, 13, 3105. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed F, Yang YJ, Samantasinghar A, Kim YW, Ko JB, Choi KH. Network-based drug repurposing for HPV-associated cervical cancer. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2023;21:5186–5200. [CrossRef]

- Zhao M, et al. Advances in organoid and CRISPR-based approaches for HPV-related cancer research. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1349. [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy A, et al. Precision oncology for HPV-associated cancers: a roadmap toward personalized treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, e428–e439.

- Bhatia S, et al. Emerging therapies in HPV-associated cancers: opportunities and challenges. J Clin Oncol. 2021, 39, 3359–3370.

| Approach | Mechanism | Advantages | Challenges | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/TALEN | E6/E7 gene disruption → p53/pRb reactivation | Durable effect, tumor suppression | Vector delivery, off-target effects, safety concerns | |

| RNAi | Suppression of E6/E7 mRNA | Transient, no genomic alteration | Short-lived effects, delivery difficulties | |

| Therapeutic Vaccines | Induction of T cell immune response | Immune activation, long-term protection | Limited Phase III data | |

| Small Molecules | Inhibition of oncoprotein complexes | Targeted, direct molecular intervention | Potential off-target effects on normal cellular functions | |

| Nano-therapy | Targeted drug delivery | Increased efficacy, reduced toxicity | Complex manufacturing, safety uncertainties | |

| Organoids + AI | Personalized drug response modeling | Precision medicine, biomarker discovery | Lack of standardization, limited datasets |

| Feature | Zheng et al. (2014) | Jubair et al. (2019/2021) |

|---|---|---|

| Model | In vitro (SiHa, CaSki cell lines) | In vivo (HPV16+ tumor-bearing mice) |

| Target | E7 oncogene only | Primarily E7, but also systems targeting both E6 and E7 |

| Delivery Method | Plasmid-based transfection | Systemic delivery via PEGylated liposomes |

| Outcome | Apoptosis induction, pRb restoration, growth arrest | Tumor regression, prolonged survival, efficient genome editing |

| Challenges | Limited to in vitro application | Need for metastatic targeting, off-target risks, vector optimization |

| Drug/Therapy | Type | Target/Mechanism | Clinical Phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nivolumab | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor | PD-1 | Approved |

| Decitabine | Epigenetic Drug | DNMT inhibition | Phase II |

| VGX-3100 | DNA Therapeutic Vaccine | E6/E7-specific immune response | Phase III |

| CRISPR-E7 (preclin) | Gene Editing | E7 knockout via Cas9 | Preclinical |

| Curcumin | Natural Compound | NF-κB inhibition, apoptosis induction | Preclinical |

| Drug | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|

| VGX-3100 | Induces T-cell responses targeting E6/E7 oncoproteins (therapeutic vaccine) |

| Lopinavir/Ritonavir | Protease inhibitor disrupting viral protein function |

| Niclosamide | Downregulates E6/E7 expression; modulates cell signaling pathways |

| Cidofovir | Viral DNA polymerase inhibitor blocking DNA synthesis |

| PRGN-2012 | Induces cellular immune activation against E6/E7 proteins |

| GS-9191 | Topical nucleotide analogue inhibiting viral DNA synthesis |

| Trial Name | Intervention | Cancer Type | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| CheckMate-358 | Nivolumab (PD-1) | Cervical, HNSCC | Completed |

| NCT03162224 | CRISPR-Cas9 targeting E7 | Cervical | Recruiting |

| NCT03180684 | VGX-3100 therapeutic vaccine | Cervical lesions | Phase III |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).