Submitted:

01 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. ELISA

2.3. Ella

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Data Overview

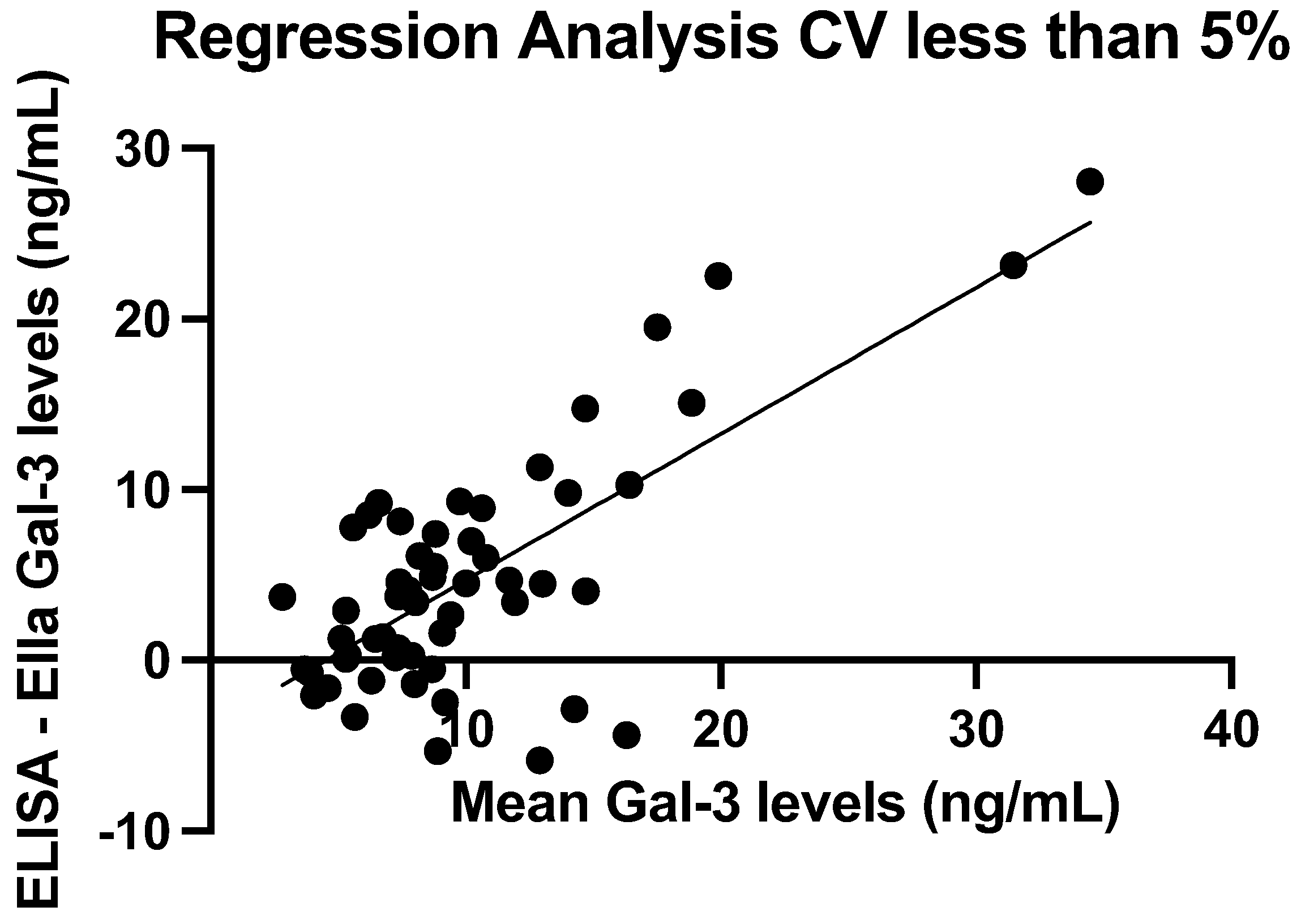

3.2. Assay Precision

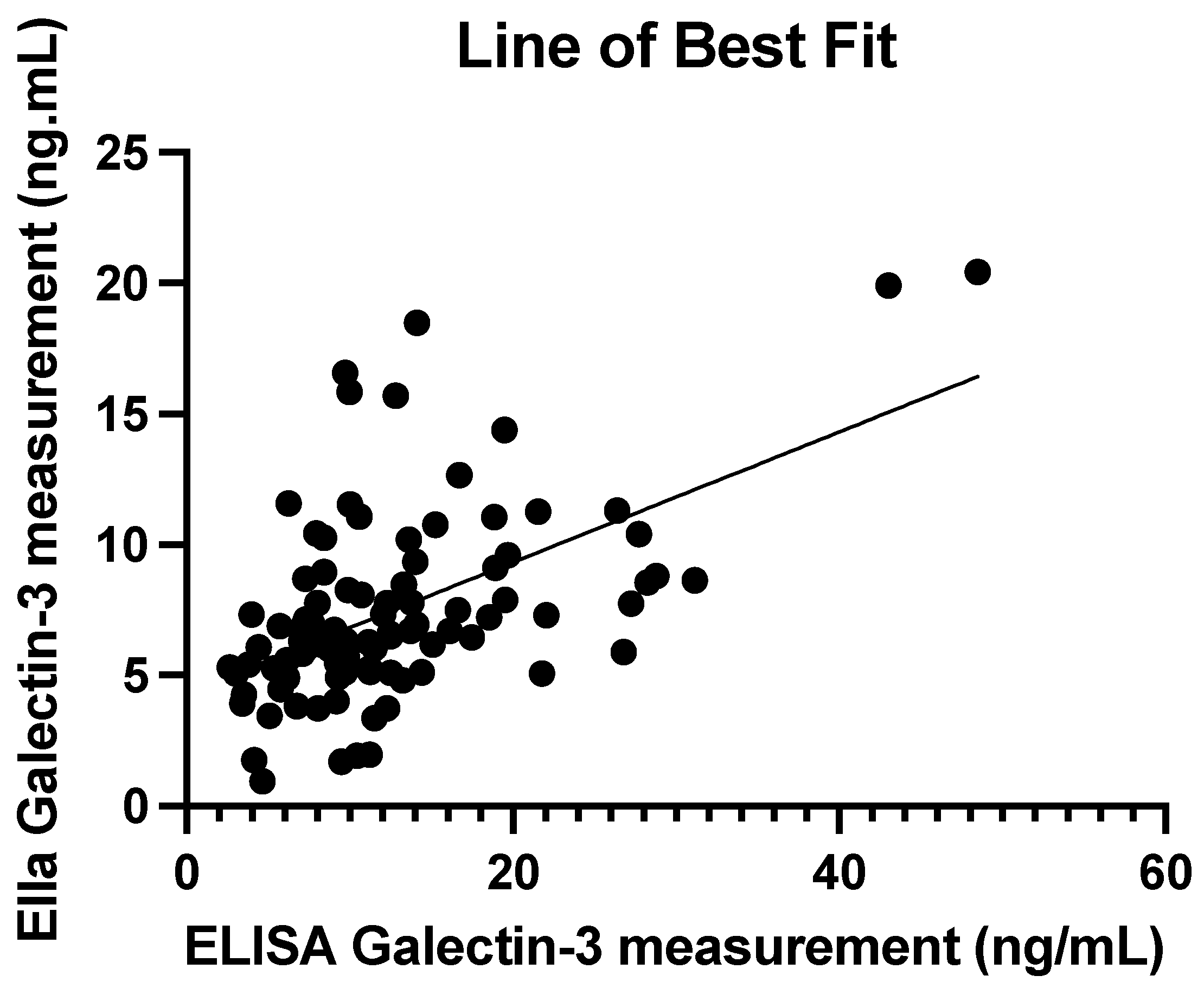

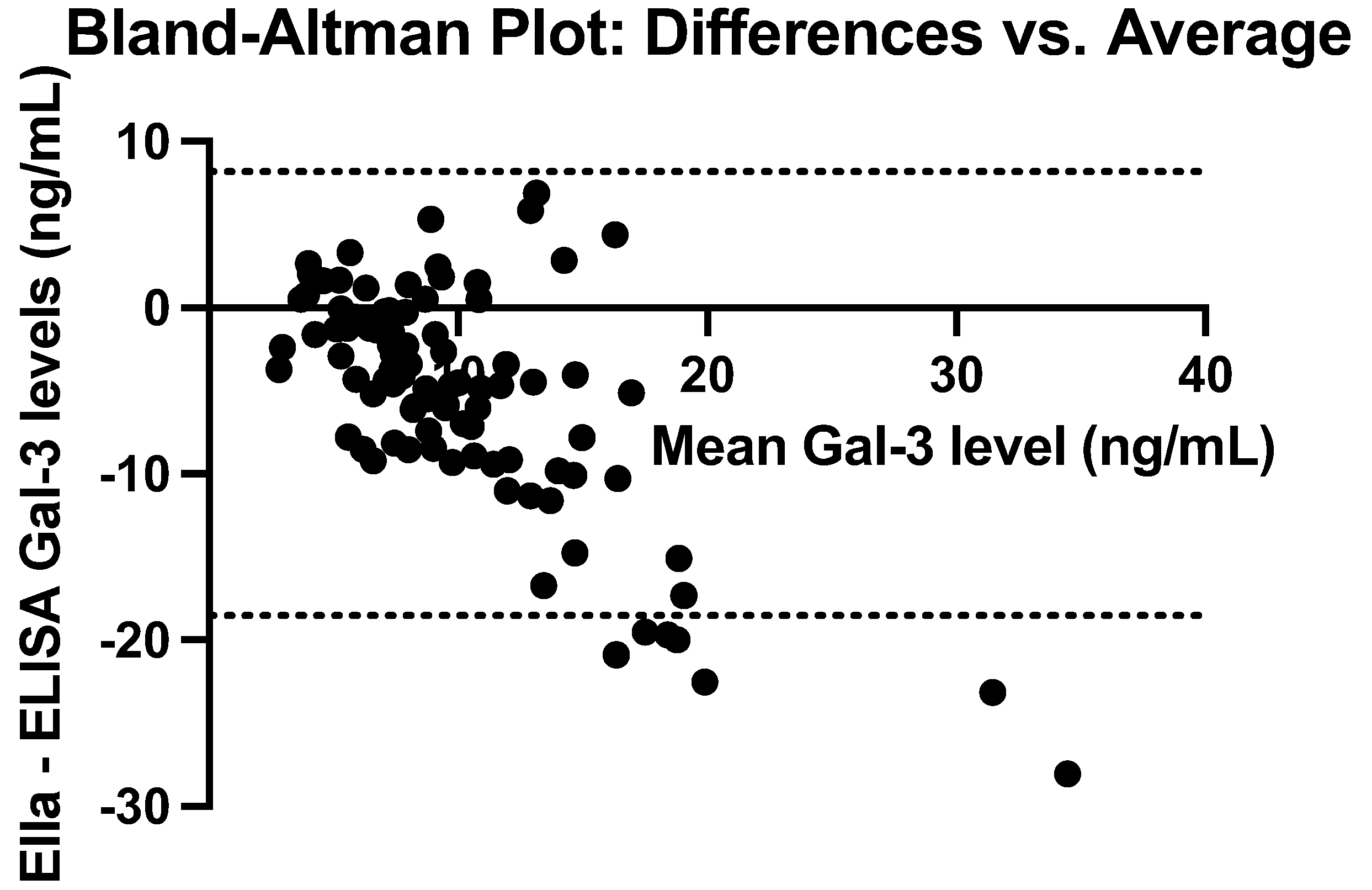

3.3. Comparison of ELISA and Ella Measurements

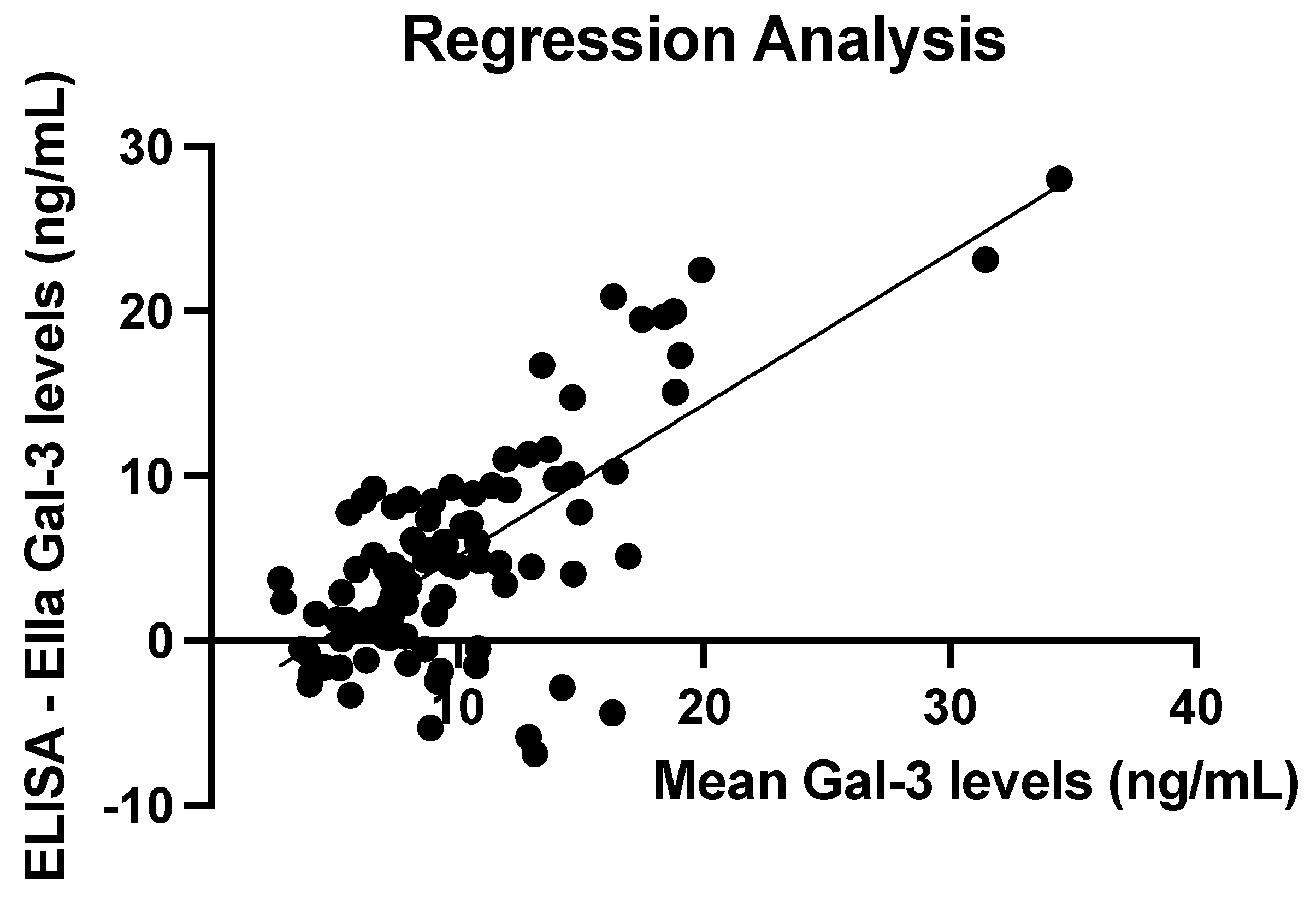

3.4. ELISA and Ella Measurements: Regression Line

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Findings

4.2. Implications

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Direction

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ELISA | Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| Gal-3 | Galectin-3 |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| Ras | Rat Sarcoma |

| Raf | Rapidly Accelerated Fibrosarcoma |

| ERK | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase |

| MEK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase |

| VEGFR2 | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A Receptor 2 |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 |

| CCL2 | Chemokine (C-C motif) Ligand 2 |

| VEGF-A | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

References

- Liu, F. Intracellular functions of galectins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2002, 1572, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nio-Kobayashi, J. Tissue- and cell-specific localization of galectins, β-galactose-binding animal lectins, and their potential functions in health and disease. Anat. Sci. Int. 2016, 92, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Alvarez, L.; Ortega, E. The Many Roles of Galectin-3, a Multifaceted Molecule, in Innate Immune Responses against Pathogens. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anadón, A.; Castellano, V.; Martínez-Larrañaga, M.R. (2014). Chapter 55—Biomarkers in drug safety evaluation. In R. C. Gupta (Ed.), Biomarkers in Toxicology (pp. 923–945). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Haudek, K.C.; Spronk, K.J.; Voss, P.G.; Patterson, R.J.; Wang, J.L.; Arnoys, E.J. Dynamics of galectin-3 in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gen. Subj. 2010, 1800, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, T.; Zhou, Z.; Xiao, Y. Emerging roles of Galectin-3 in diabetes and diabetes complications: A snapshot. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2022, 23, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.-J.; Yu, G.-F.; Jie, Y.-Q.; Fan, X.-F.; Huang, Q.; Dai, W.-M. Role of galectin-3 in plasma as a predictive biomarker of outcome after acute intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 368, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanda, V.; Bracale, U.M.; Di Taranto, M.D.; Fortunato, G. Galectin-3 in Cardiovascular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutin, L.; Dépret, F.; Gayat, E.; Legrand, M.; Chadjichristos, C.E. Galectin-3 in Kidney Diseases: From an Old Protein to a New Therapeutic Target. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aureli, A.; Del Cornò, M.; Marziani, B.; Gessani, S.; Conti, L. Highlights on the Role of Galectin-3 in Colorectal Cancer and the Preventive/Therapeutic Potential of Food-Derived Inhibitors. Cancers 2022, 15, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, B.B.; Funkhouser, A.T.; Goodwin, J.L.; Strigenz, A.M.; Chaballout, B.H.; Martin, J.C.; Arthur, C.M.; Funk, C.R.; Edenfield, W.J.; Blenda, A.V. Increased Circulating Levels of Galectin Proteins in Patients with Breast, Colon, and Lung Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, T.S.; Oshima, C.T.F.; Forones, N.M.; Lima, F.D.O.; Ribeiro, D.A. Expression of galectin-3 in gastric adenocarcinoma. Indian J. Med. Res. 2014, 140, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.Y.; Hsu, D.K.; Liu, F.T. Expression of galectin-3 modulates T-cell growth and apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996, 93, 6737–6742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, H.-G.; Goedegebuure, P.S.; Sadanaga, N.; Nagoshi, M.; von Bernstorff, W.; Eberlein, T.J. Expression and function of galectin-3, a β-galactoside-binding protein in activated T lymphocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2001, 69, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frigeri, L.G.; Zuberi, R.I.; Liu, F.T. .epsilon.BP, a.beta.-galactoside-binding animal lectin, recognizes IgE receptor (Fc.epsilon.RI) and activates mast cells. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 7644–7649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragomir, A.-C.D.; Sun, R.; Choi, H.; Laskin, J.D.; Laskin, D.L. Role of Galectin-3 in Classical and Alternative Macrophage Activation in the Liver following Acetaminophen Intoxication. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 5934–5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaoka, A.; Kuwabara, I.; Frigeri, L.G.; Liu, F.T. A human lectin, galectin-3 (epsilon bp/Mac-2), stimulates superoxide production by neutrophils. J. Immunol. 1995, 154, 3479–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, S.F.; Wang, J.L.; Patterson, R.J. Identification of galectin-3 as a factor in pre-mRNA splicing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995, 92, 1213–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, B.B.; Funkhouser, A.T.; Goodwin, J.L.; Strigenz, A.M.; Chaballout, B.H.; Martin, J.C.; Arthur, C.M.; Funk, C.R.; Edenfield, W.J.; Blenda, A.V. Increased Circulating Levels of Galectin Proteins in Patients with Breast, Colon, and Lung Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raz, A.; Lotan, R. Endogenous galactoside-binding lectins: a new class of functional tumor cell surface molecules related to metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1987, 6, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.C.F.; Andrade, L.N.d.S.; Bustos, S.O.; Chammas, R. Galectin-3 Determines Tumor Cell Adaptive Strategies in Stressed Tumor Microenvironments. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funasaka, T.; Raz, A.; Nangia-Makker, P. Galectin-3 in angiogenesis and metastasis. Glycobiology 2014, 24, 886–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, I.; Hu, Z.; AbuSamra, D.B.; Saint-Geniez, M.; Ng, Y.S.E.; Argüeso, P.; D’aMore, P.A. Galectin-3 Enhances Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-A Receptor 2 Activity in the Presence of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, B.-K.; Lee, Y.J.; Battle, P.; Jessup, J.M.; Raz, A.; Kim, H.-R.C. Galectin-3 Protects Human Breast Carcinoma Cells against Nitric Oxide-Induced Apoptosis: Implication of Galectin-3 Function during Metastasis. Am. J. Pathol. 2001, 159, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Nangia-Makker, P.; Balan, V.; Hogan, V.; Raz, A. Calpain activation through galectin-3 inhibition sensitizes prostate cancer cells to cisplatin treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2010, 1, e101–e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Guo, S.; Kim, S.-J.; Shao, F.; Ho, J.W.K.; Wong, K.U.; Miao, Z.; Hao, D.; Zhao, M.; Xu, J.; et al. Cisplatin prevents breast cancer metastasis through blocking early EMT and retards cancer growth together with paclitaxel. Theranostics 2021, 11, 2442–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhad, M.; Rolig, A.S.; Redmond, W.L. The role of Galectin-3 in modulating tumor growth and immunosuppression within the tumor microenvironment. OncoImmunology 2018, 7, e1434467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillman, B.N.; Hsu, D.K.; Pang, M.; Brewer, C.F.; Johnson, P.; Liu, F.-T.; Baum, L.G. Galectin-3 and Galectin-1 Bind Distinct Cell Surface Glycoprotein Receptors to Induce T Cell Death. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melief, S.M.; Visser, M.; van der Burg, S.H.; Verdegaal, E.M.E. IDO and galectin-3 hamper the ex vivo generation of clinical grade tumor-specific T cells for adoptive cell therapy in metastatic melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2017, 66, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liang, X.; Duan, C.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Glynn, S.A. Galectin-3 as a Marker and Potential Therapeutic Target in Breast Cancer. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e103482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funkhouser, A.T.; Strigenz, A.M.; Blair, B.B.; Miller, A.P.; Shealy, J.C.; Ewing, J.A.; Martin, J.C.; Funk, C.R.; Edenfield, W.J.; Blenda, A.V. KIT Mutations Correlate with Higher Galectin Levels and Brain Metastasis in Breast and Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markalunas, E.G.; Arnold, D.H.; Funkhouser, A.T.; Martin, J.C.; Shtutman, M.; Edenfield, W.J.; Blenda, A.V. Correlation Analysis of Genetic Mutations and Galectin Levels in Breast Cancer Patients. Genes 2024, 15, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhajj, M. , Zubair, M., & Farhana, A. (2025). Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 5559. [Google Scholar]

- Engvall, E. The ELISA, Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay. Clin. Chem. 2010, 56, 319–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Maghsoudlou, P. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA): the basics. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2016, 77, C98–C101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, S. A short history, principles, and types of ELISA, and our laboratory experience with peptide/protein analyses using ELISA. Peptides 2015, 72, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruson, D.; Mancini, M.; Ahn, S.; Rousseau, M. Measurement of Galectin-3 with the ARCHITECT assay: Clinical validity and cost-effectiveness in patients with heart failure. Clin. Biochem. 2014, 47, 1006–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijers, W. (2019). Circulating factors in heart failure: Biomarkers, markers of co-morbidities and disease factors. [Groningen]: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen.

- Aldo, P.; Marusov, G.; Svancara, D.; David, J.; Mor, G. Simple Plex™: A Novel Multi-Analyte, Automated Microfluidic Immunoassay Platform for the Detection of Human and Mouse Cytokines and Chemokines. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2016, 75, 678–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dysinger, M.; Marusov, G.; Fraser, S. Quantitative analysis of four protein biomarkers: An automated microfluidic cartridge-based method and its comparison to colorimetric ELISA. J. Immunol. Methods 2017, 451, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wessels, U.; Mackeben, K.; Stubenrauch, K. Use of Ella ® to Facilitate drug Quantification and Antidrug Antibody Detection in Preclinical Studies. Bioanalysis 2019, 11, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macis, D.; Aristarco, V.; Johansson, H.; Guerrieri-Gonzaga, A.; Raimondi, S.; Lazzeroni, M.; Sestak, I.; Cuzick, J.; DeCensi, A.; Bonanni, B.; et al. A Novel Automated Immunoassay Platform to Evaluate the Association of Adiponectin and Leptin Levels with Breast Cancer Risk. Cancers 2021, 13, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean (ng/mL) | SD (ng/mL) | Median (ng/mL) | IQR (ng/mL) | Min–Max (ng/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA | 12.68 | 8.07 | 10.59 | 7.43–15.10 | 2.65–48.48 |

| Ella | 7.49 | 3.71 | 6.70 | 5.20–8.80 | 0.95–20.43 |

| ELISA—Ella | -5.19 | 6.81 | -4.32 | -8.54–-0.30 | -28.06–6.88 |

| Mean (%) | SD (%) | Median (%) | IQR (%) | Min–Max (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA | 7.50 | 13.78 | 4.75 | 1.85–7.82 | 0.17–127.84 |

| Ella | 2.41 | 1.46 | 2.10 | 1.37–3.27 | 0.19–6.86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).