1. Introduction

Cancer immunotherapy has revolutionized the treatment landscape for various malignancies, offering new hope for patients with previously intractable diseases. Among the most promising approaches in this field is the targeting of immune checkpoint molecules, particularly the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and its receptor, programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1). The PD-1/PD-L1 axis plays a crucial role in maintaining immune homeostasis and preventing autoimmunity under normal physiological conditions. PD-L1 is overexpressed in cancer cells, which enhances their tumorigenic potential intrinsically (immune-independent)[

1,

2,

3,

4,

5] or through immune evasion by evading immune surveillance via PD-1-mediated T cell inactivation [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Therefore, blocking inhibitory signaling by PD-1/PD-L1 with antibodies can suppress tumor growth by directly inhibiting tumor cell proliferation or reactivating cytotoxic T-cell behavior[

7,

10,

11]. Many PD-1/PD-L1 blocking antibodies have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of multiple cancer types such as melanoma and lung cancer[

11,

12,

13]. Over 2,000 PD-1/PD-L1 blockade clinical trials in various cancers are ongoing globally, and many patients are displaying impressive responses[

14]. Therefore, anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy is currently one of the most promising cancer therapies. Although durable responses have been achieved in melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer, objective response rates in breast cancer—particularly in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)—remain modest [

15,

16,

17]. This underscores the need for a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms governing PD-L1 expression and regulation in cancer cells.

PD-L1 expression is regulated by cytokine signaling (e.g., IFN-γ/JAK-STAT), oncogenic pathways (PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Hippo/YAP/TAZ, MAPK) and post-translational modifications that govern protein stability and trafficking. Kinases orchestrate many of these processes and are highly druggable, yet only a few kinases including GSK3β, AMPK, ROCK and CK2 have been shown to act directly on PD-L1[

18,

19,

20]. Although targeting PD-L1 or kinase involved in cancer alone have some clinical benefit in certain type of cancer, intrinsic or acquired resistance often arises after treatment. Recent studies strongly suggest that combined treatment of cancer with kinase inhibitors and anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy may overcome resistance of cancers to single drug therapy[

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Therefore, identification of novel kinases interacting with PD-L1 may provide novel therapeutic strategy. We therefore undertook an unbiased kinome-wide screen to map new kinase regulators of PD-L1.

Using a HEK293A line that constitutively expresses NanoLuc (NL)-tagged PD-L1 devoid of its native promoter, we interrogated >500 kinases with selective inhibitors. This approach bypasses transcriptional inputs and focuses on post-translational control. The screen highlighted focal adhesion kinase (FAK) as a strong hit. FAK integrates integrin and growth-factor signaling to control adhesion, migration and survival[

28]. FAK is frequently overexpressed in cancers including TNBC and is currently being tested in clinical trials[

22,

23]. Yet its role in tumor immune evasion remains poorly defined. Here we delineate a previously unrecognized FAK–PD-L1 axis with therapeutic implications for TNBC.

2. Results

2.1. Establishment of Cell Line Stably Expressing NanoLuc Tagged PD-L1

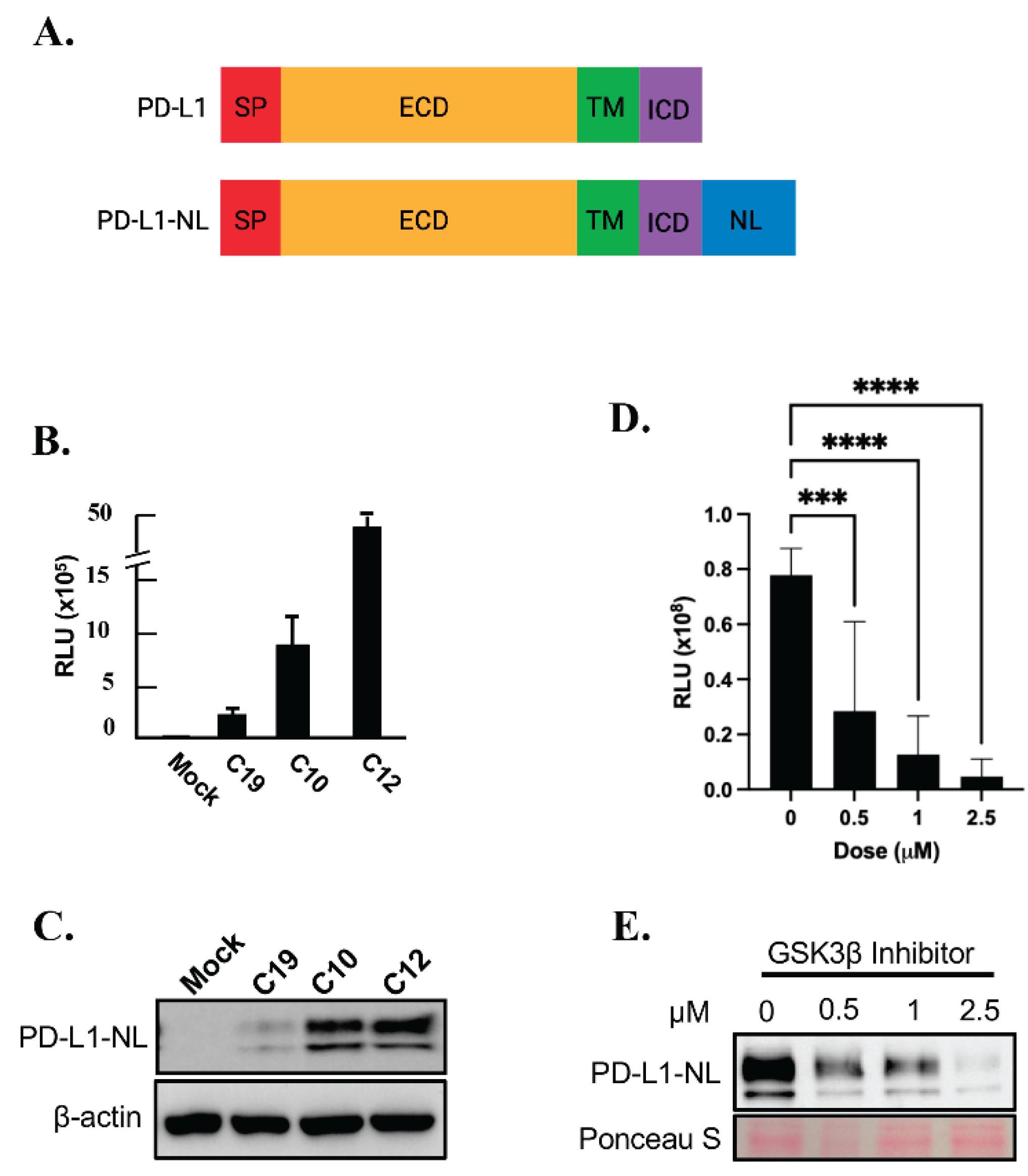

To establish a stable cell line expressing a reporter for PD-L1 levels, HEK293A cells were transfected with a PD-L1-NanoLuc fusion (PD-L1-NL;

Figure 1A) construct driven by the CMV promoter, followed by hygromycin selection. Single HEK293A clones expressing PD-L1-NL were isolated, expanded and subjected to luciferase assay and western blot analysis. As shown in

Figure 1B-1C, the luciferase activity in each clone positively correlated with PD-L1-NL expression levels. To further validate our PD-L1 NanoLuc reporter, HEK293A-PD-L1-NL cells were treated with increasing concentration of GSK3β inhibitor, a well-known degrader of PD-L1 stability[

29]. As expected, PD-L1-NL degradation increased in a dose-dependent manner, as evidenced by decreased luciferase activity and reduced PD-L1-NL protein levels (

Figure 1D–1E). These results confirm the successful establishment of a HEK293A cell line stably expressing a NanoLuc-based PD-L1 reporter.

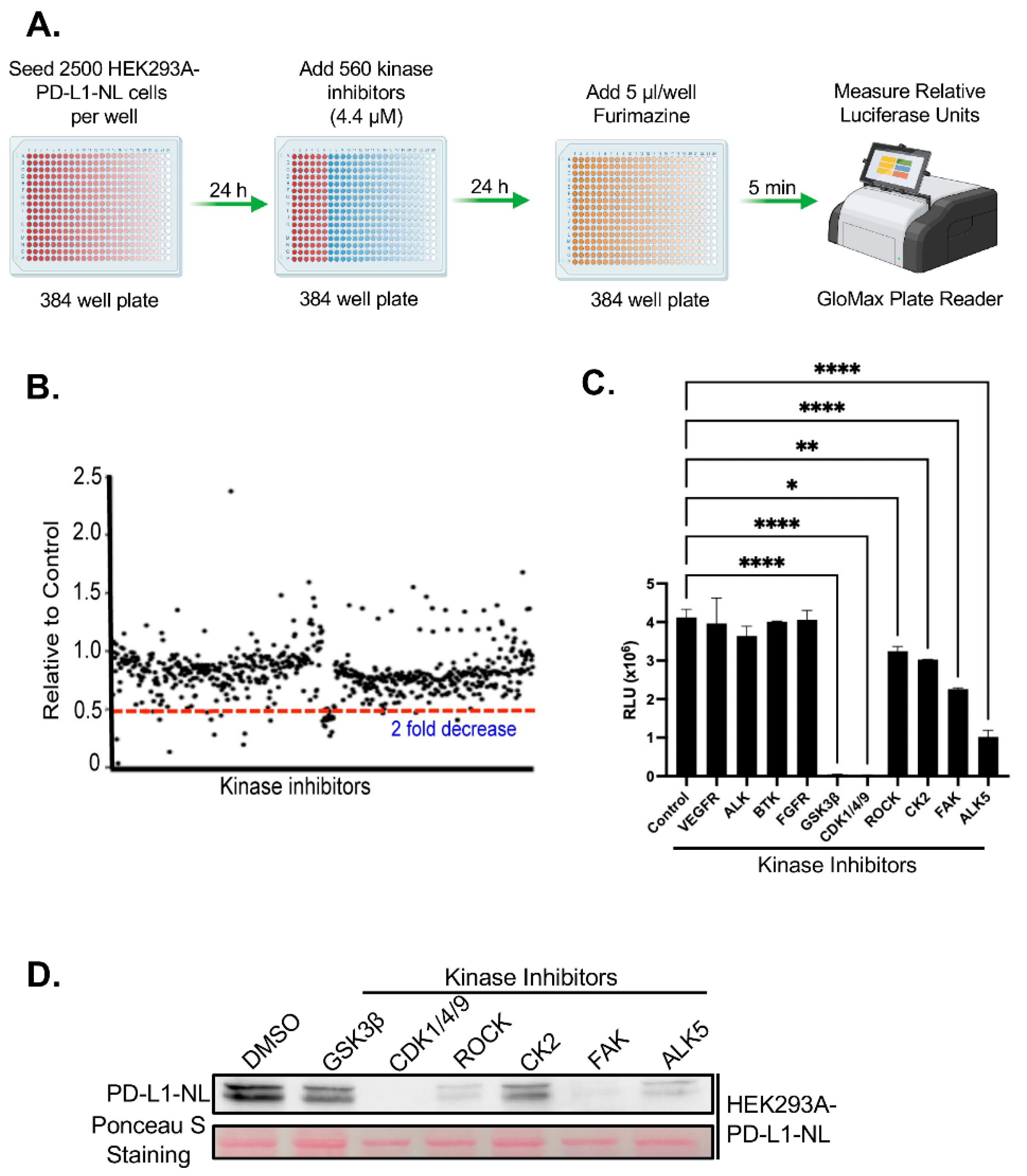

2.2. Kinome-Wide High Throughput Screen (HTS) for Kinase Inhibitors Regulating PD-L1 Stability

We next performed a kinome-wide HTS to identify kinase inhibitors that regulate PD-L1 stability. To minimize indirect effects associated with prolonged drug exposure, HEK293A-PD-L1-NL cells were treated with a library of 560 inhibitors targeting the human kinome for 24 hours, followed by luciferase assays (

Figure 2A). Approximately 19 inhibitors were identified that reduced luciferase activity by more than twofold (

Figure 2B;

Table 1S). Among these, inhibitors targeting three previously known PD-L1 regulators including GSK3β, CK2, ROCK were confirmed[

21,

22,

29], while 16 represented novel candidate regulators of PD-L1 stability. We have further validated the screening hits by luciferase assays. Six out of 10 kinase inhibitors (60%) tested are confirmed to suppress PD-L1-NL luciferase activity (

Figure 2C). We further validated a subset of these hits via luciferase assays. Of the 10 inhibitors tested, 6 (60%) were confirmed to significantly suppress PD-L1-NL luciferase activity (

Figure 2C). To determine whether the reduced luciferase signal reflected decreased PD-L1-NL protein levels, we treated HEK293A-PD-L1-NL cells with the validated inhibitors and performed western blot analysis. All tested inhibitors markedly reduced PD-L1-NL protein levels (

Figure 2D). Taken together, these results identified six kinases, including three novel ones, CDK1/4/9, FAK, and ALK5, as regulators of PD-L1 stability.

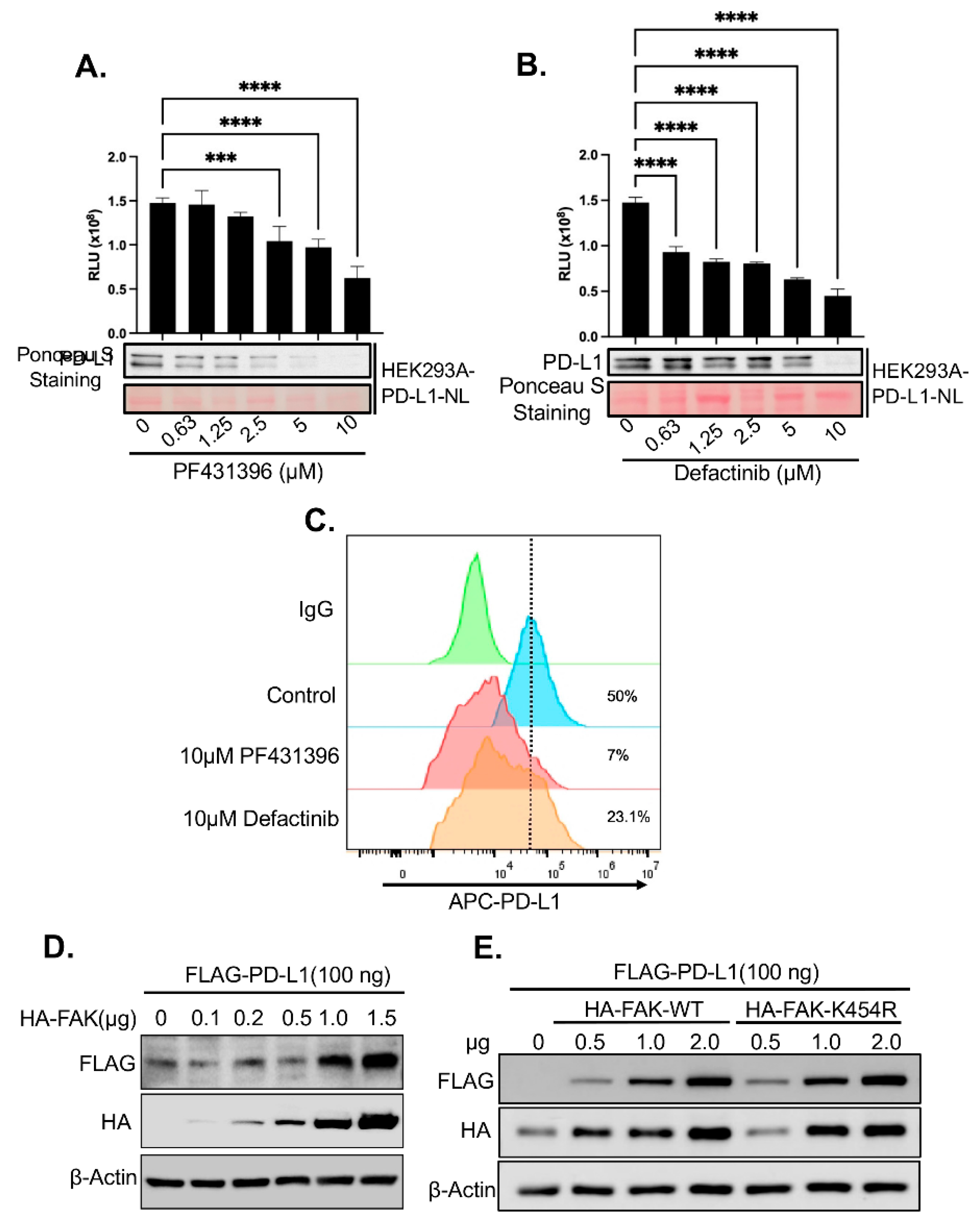

2.3. Validation of FAK as Novel Regulator of PD-L1 Stability

Given the strong effect of FAK inhibitors on PD-L1 stability observed in our screen (

Figure 2D) and the established role of FAK in TNBC [

30], we further investigated whether FAK is a novel regulator of PD-L1. First, we validated that the FAK inhibitor PF431396 used in the HTS reduced PD-L1-NL luciferase activity and protein levels in HEK293A cells in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 3A). To rule out potential off-target effects of PF431396, we also treated HEK293A-PD-L1-NL cells with Defactinib, a more specific FAK inhibitor currently undergoing Phase II clinical trials[

31]. Notably, similar to PF431396, Defactinib also decreased PD-L1-NL stability in a dose-dependent fashion (

Figure 3B).

Since PD-L1 must localize to the cell membrane to engage PD-1 on immune cells and promote immune evasion, we next examined whether FAK inhibition affects membrane-bound PD-L1. Treatment with either PF431396 or Defactinib significantly reduced membrane PD-L1 levels in HEK293A cells (

Figure 3C).

We then assessed the impact of FAK overexpression on PD-L1 levels. Co-transfection of increasing amounts of HA-tagged FAK together with a fixed amount of HA-tagged PD-L1 into HEK293A cells led to a dose-dependent increase in PD-L1 protein levels (

Figure 3D). Surprisingly, this effect was independent of FAK’s kinase activity, as a kinase-dead mutant (FAK-K454R) was equally effective at increasing PD-L1 stability compared to the wild-type (WT) protein (

Figure 3E).

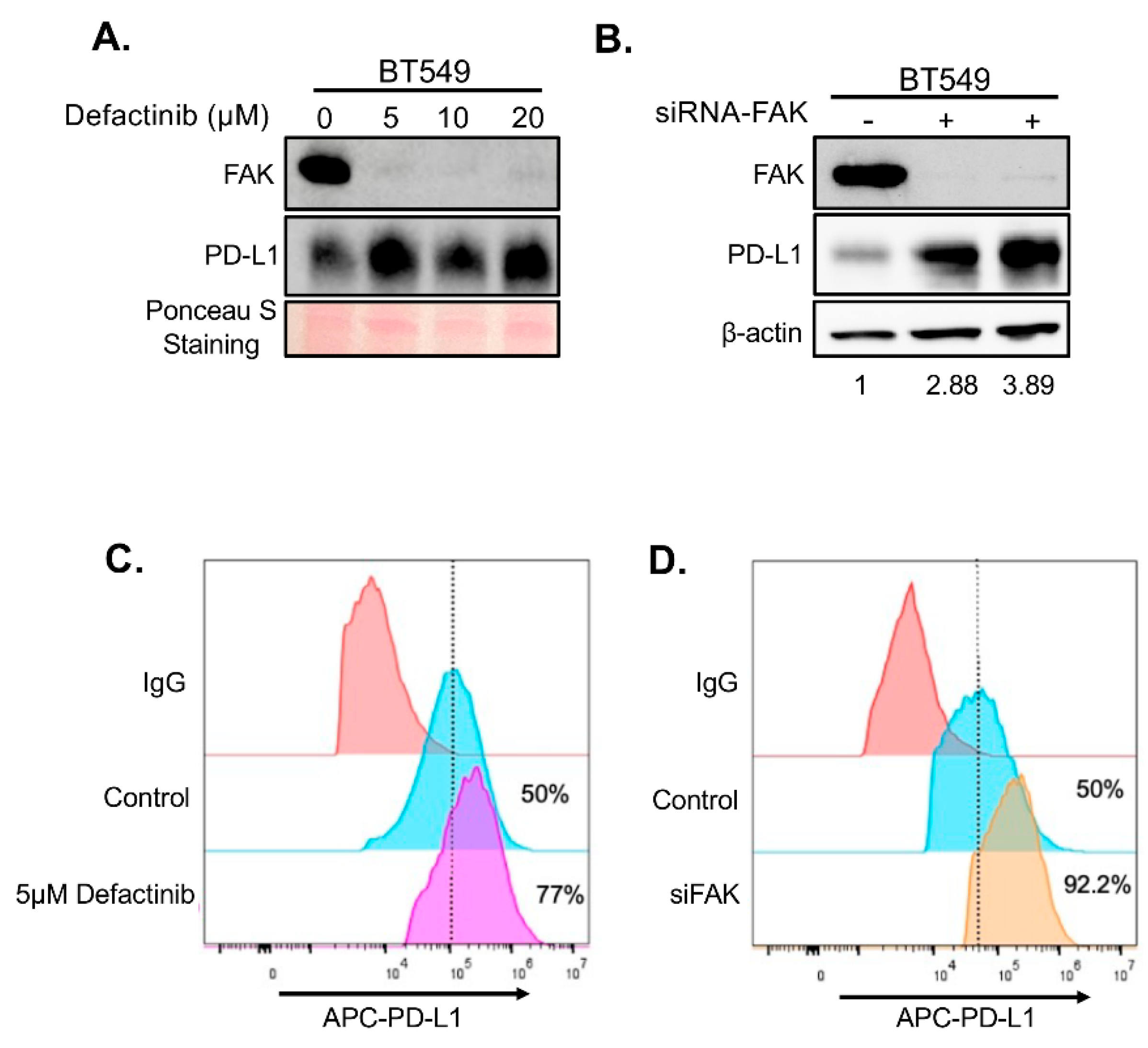

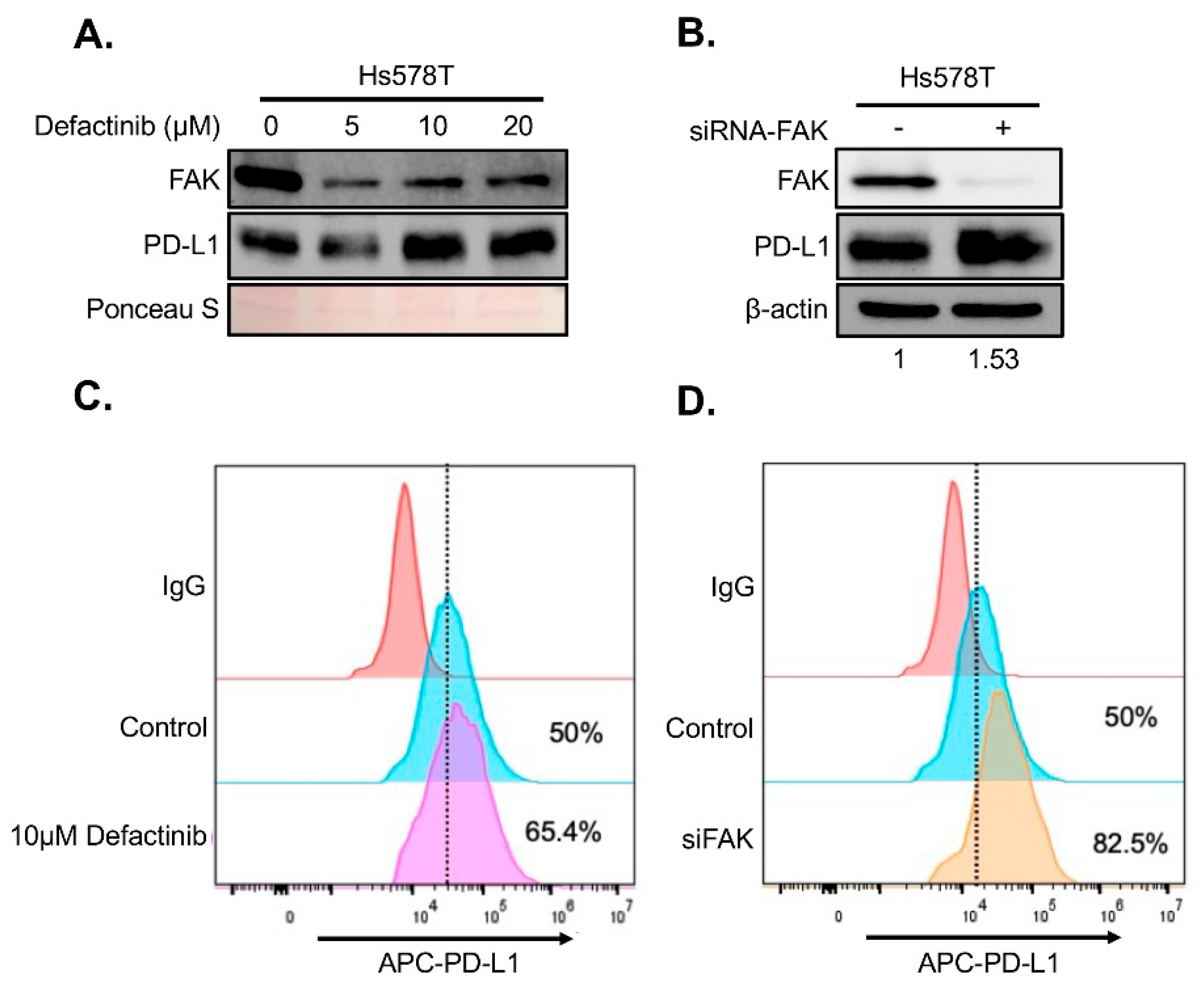

To determine whether FAK also regulates PD-L1 in TNBC cells, we treated two FAK- and PD-L1-positive TNBC cell lines, BT549 and Hs578T, with increasing concentrations of Defactinib. Unexpectedly, FAK inhibition in these cells led to elevated levels of both total and membrane-bound PD-L1 (

Figure 4A–B and

Figure 5A–B), in contrast to the effects observed in HEK293A cells. To confirm that this upregulation was due to specific inhibition of FAK, we performed short interference RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of FAK in both cell lines. Consistent with Defactinib treatment, FAK siRNA (siFAK) knockdown also significantly increased total and membrane PD-L1 levels in both TNBC cell lines (

Figure 4C-4D,

Figure 5C-5D).

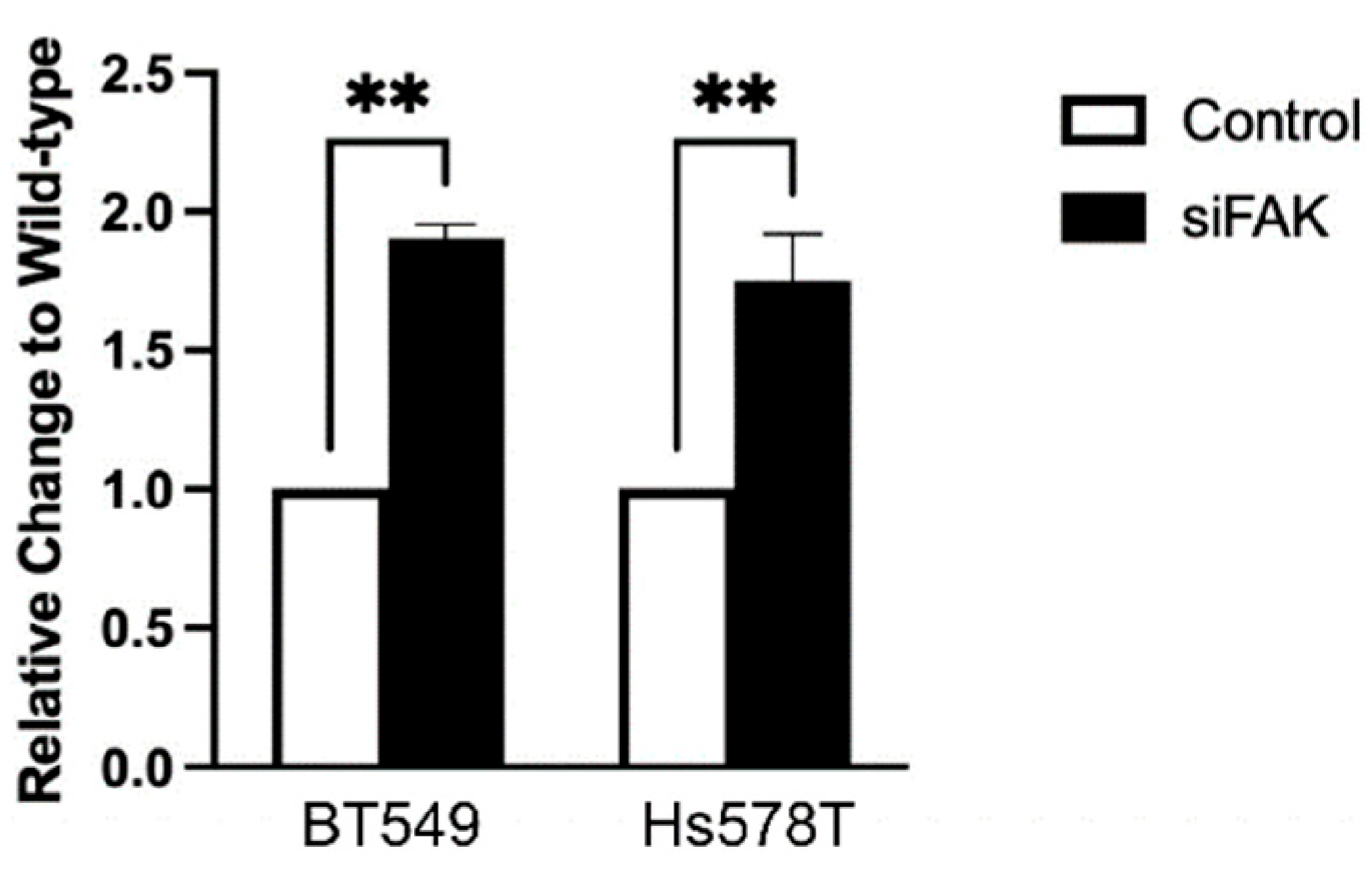

Since the PD-L1-NL construct lacks a promoter, changes in luciferase signal in HEK293A cells reflect post-transcriptional regulation. However, because TNBC cells retain the endogenous PD-L1 promoter, it remained unclear whether the increase in PD-L1 levels following FAK inhibition was due to enhanced transcription. To address this, we measured PD-L1 mRNA levels following FAK knockdown. Interestingly, siFAK also increases PD-L1 mRNA expression in both TNBC cell lines (

Figure 6), suggesting that FAK can regulate PD-L1 at the transcriptional level in these cells as well.

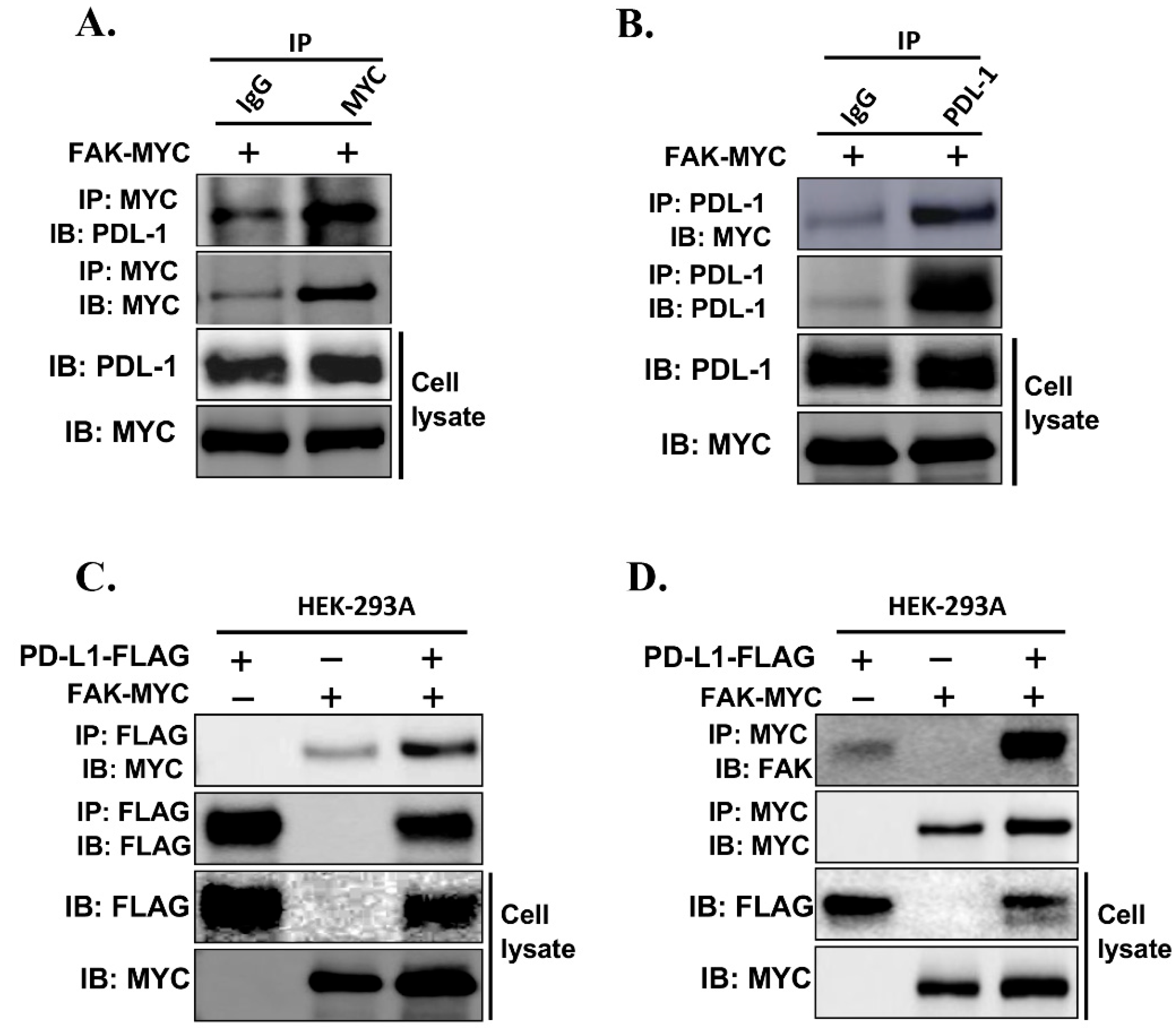

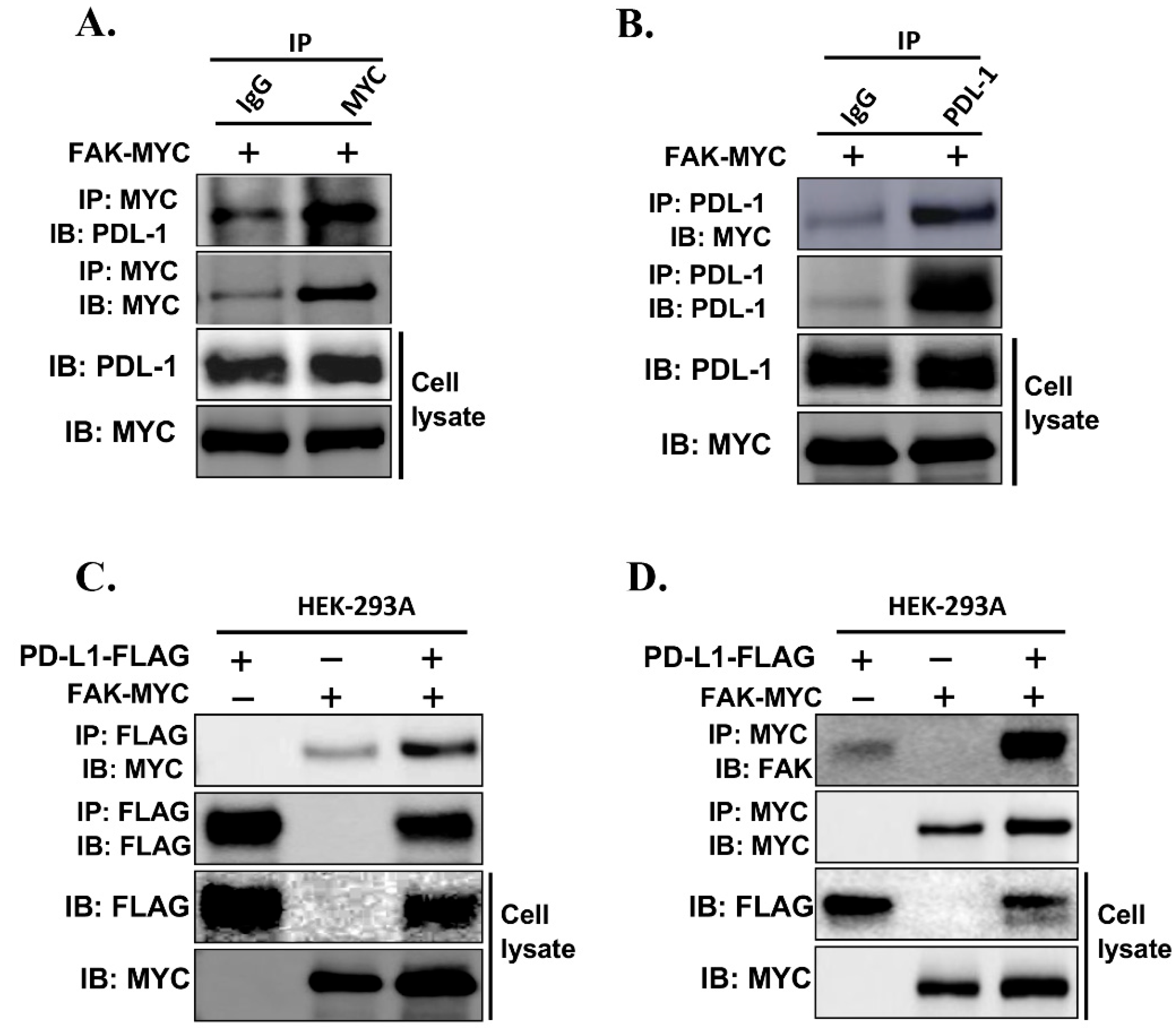

To further investigate whether FAK directly interacts with PD-L1 and regulates its stability, we examined the physical association between the two proteins

in vivo. We transfected MYC-tagged FAK into HEK293A-PD-L1-NL cells, followed by protein extraction and co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) analysis. Immunoprecipitation using an anti-MYC antibody, but not IgG control, successfully pulled down PD-L1-NL (

Figure 7A). Conversely, immunoprecipitation of PD-L1-NL using an anti-PD-L1 antibody pulled down MYC-tagged FAK (

Figure 7B). This interaction was further confirmed through co-transfection of FAK-MYC and PD-L1-FLAG into HEK293A cells (

Figures 7C–7D).

Together, these results strongly support that FAK directly binds to PD-L1 and regulates its levels in cancer cells.

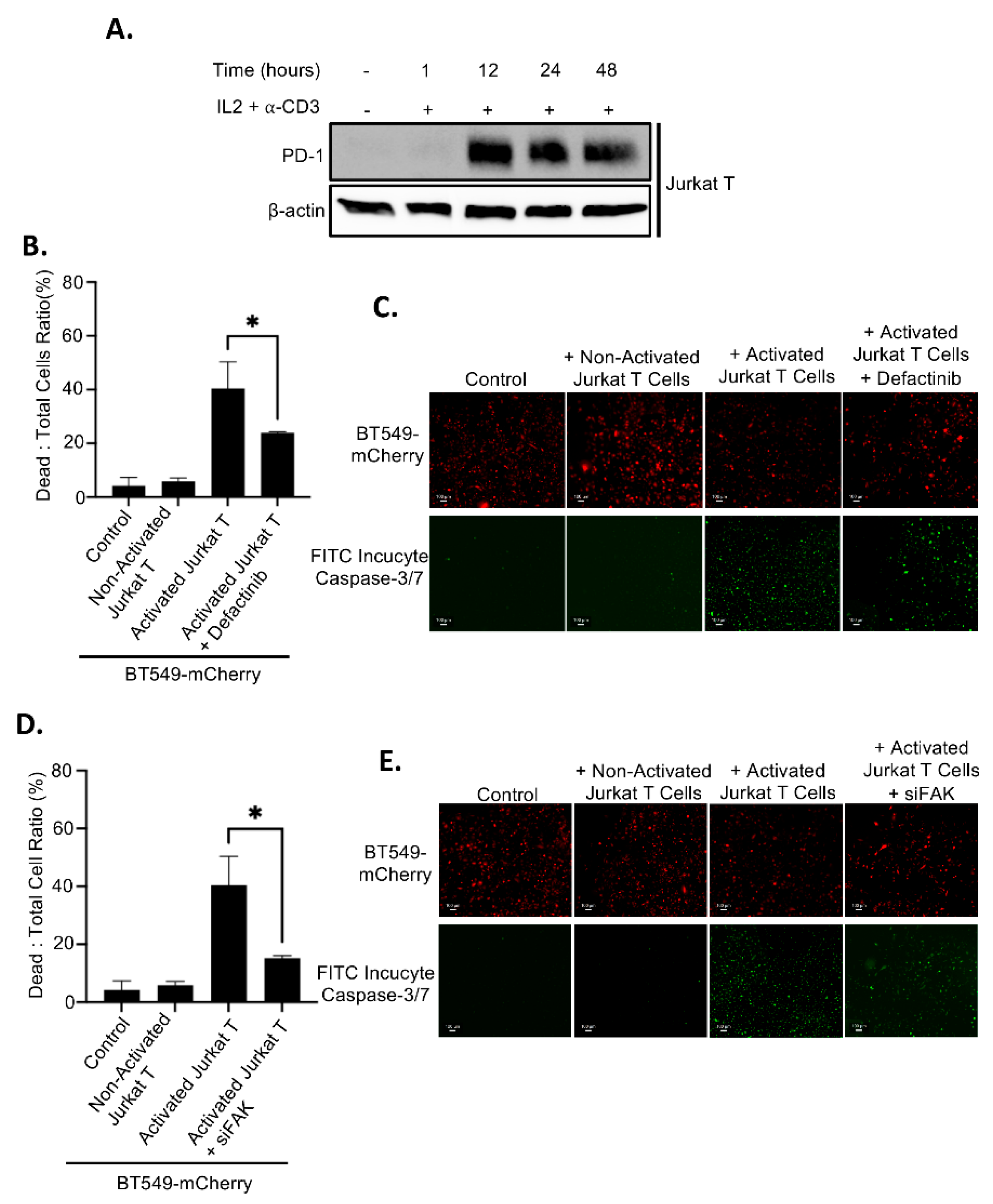

2.4. Upregulation of PD-L1 After FAK Inhibition Causes Increased Immune Evasion

Since FAK inhibition leads to elevated levels of membrane PD-L1, which may bind to PD-1 on T cells and promote immune evasion, we assessed whether FAK inhibition affects T cell–mediated killing of TNBC cells. Jurkat T cells were activated by treatment with IL2 and anti-CD3 antibody for 12 hours, resulting in high PD-1 expression (

Figure 8A). As expected, co-culture of inactivated (PD-1-negative) Jurkat T cells with BT549 cells had no effect on cancer cell viability. In contrast, co-culture with activated (PD-1-positive) Jurkat T cells induced substantial cancer cell death (

Figures 8B–8E). Importantly, inhibition of FAK, either by Defactinib treatment or siRNA-mediated knockdown (siFAK), significantly impaired T cell–mediated killing of BT549 cancer cells (

Figures 8B–8E), indicating that FAK inhibition enhances immune evasion by upregulating PD-L1.

3. Discussion

Although triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) accounts for only 15–20% of all breast cancer cases, its high rates of metastasis and recurrence, poor prognosis, and limited treatment options pose significant clinical challenges, largely due to the lack of well-defined molecular targets. Therefore, the identification of novel diagnostic and therapeutic targets for TNBC is urgently needed.

FAK is a non-receptor protein tyrosine kinase known to promote tumorigenesis and metastasis by regulating key cancer hallmarks, including cell proliferation, survival, migration, and invasion

[31]. Therefore, FAK has emerged as a potential therapeutic target in various cancers. Several small-molecule inhibitors targeting FAK’s kinase function are currently under development and undergoing clinical testing

[32]. Despite promising results in preclinical and early-phase trials, no FAK inhibitor has yet achieved clinical success. Notably, FAK is frequently upregulated in TNBC compared to normal breast tissue, supporting its candidacy as a therapeutic target in this aggressive subtype

[33]. Elevated FAK expression in breast tumors is associated with aggressive features, including increased invasiveness and the triple-negative phenotype, reinforcing its prognostic value and therapeutic relevance

[34]. Although FAK inhibitors have shown efficacy in suppressing TNBC cell invasion and tumor growth in preclinical xenograft models

[35,36], their clinical application in TNBC has thus far been unsuccessful. The underlying reasons remain unclear. Our findings offer a potential explanation: FAK inhibition stabilizes PD-L1, which may enhance immune evasion in TNBC cells. This mechanism could contribute to the lack of clinical efficacy observed with FAK inhibitors as monotherapy. Therefore, combining FAK inhibitors with immune checkpoint blockade, such as anti-PD-L1 therapy, may represent a more effective strategy for TNBC treatment. Supporting this idea, a recent study reported that the PD-L1 inhibitor Atezolizumab acts synergistically with FAK inhibition to suppress TNBC cell invasion and motility

[35]. Similarly, previous studies have shown that PARP inhibitors (PARPi) also upregulate PD-L1 expression and promote immunosuppression, and that combined PARPi and anti-PD-L1 therapy yields superior antitumor effects compared to either agent alone

[37]. Together with our findings, these results highlight a broader mechanism whereby targeted therapies may inadvertently promote immune escape through PD-L1 upregulation. Thus, combination strategies that integrate both targeted and immune therapies may provide a promising approach to overcome intrinsic or acquired resistance in TNBC and other cancers.

Our studies identified 3 novel kinases including FAK, CDK1/4/9, and ALK5 as novel kinase regulators of PD-L1 stability in HEK293A cells after HTS. Further validation also shows that CDK1/4/9 inhibitor instead of ALK5 inhibitor significantly reduce PD-L1 levels in TNBC cells (unpublished). It will be very interesting to further explore whether CDK1, CDK4, or CDK9 regulates PD-L1 stability in immune evasion of TNBC cells.

While our discovery of the FAK–PD-L1 signaling axis in immune evasion is novel and promising, several questions remain unanswered. First, the opposing effects of FAK inhibition, decreasing PD-L1 levels in HEK293A cells but increasing them in TNBC cells, are not yet understood. It is possible that differential expression of cofactors, phosphatases, or ubiquitin ligases between cell types influences FAK-mediated PD-L1 regulation. Therefore, it is important to check the effects of FAK inhibition on PD-L1 stability first when other types of cancer are treated with FAK inhibitors alone and in combination with anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy. Second, although we confirmed a direct interaction between FAK and PD-L1 in cancer cells via co-immunoprecipitation, the mechanistic basis of this interaction remains unclear. PD-L1 is a membrane protein, while FAK is predominantly cytoplasmic. However, FAK has been shown to interact with the intracellular domains of membrane proteins such as integrin and E-cadherin [

26], suggesting that FAK may similarly bind the intracellular region of PD-L1. Notably, other kinases known to regulate PD-L1 stability, such as GSK3β, CK2, and ROCK, are also localized in the cytoplasm [

22,

23,

24]. Therefore, it is plausible that FAK interacts with PD-L1 in the cytoplasm during its processing, thereby destabilizing it and preventing membrane localization. In contrast, inhibition of FAK may stabilize PD-L1 and promote its translocation to the membrane. in our studies. Finally, our current study was conducted entirely

in vitro using cancer cell lines. It remains to be determined whether FAK inhibition promotes immune evasion and tumor progression

in vivo. Future studies using immunocompetent syngeneic mouse models, such as 4T1/Balb/c, will be essential to evaluate whether combined treatment with FAK inhibitors and anti-PD-L1 antibodies offers superior efficacy against metastatic TNBC.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Kinase Inhibitors

CIHR99021 (GSK3 inhibitor), SU4312 (VEGFR inhibitor), Asp-3026 (ALK inhibitor), PCI-32765 (BTK inhibitor), BGJ398 (FGFR inhibitor), Y39983 (ROCK inhibitor), P276-00 (CDK1/4/9 inhibitor), PF431396 and Defactinib (FAK inhibitor), and CX-4945 (CK2 inhibitor) were purchased from TargetMol. SJN2511 (ALK5 inhibitor) was purchased from Cayman Chemical.

4.2. Plasmid Construction

For cloning PD-L1 open reading frame (ORF) into pNLF1-C [CMV/hygro] vector expressing NanoLuc at C-termini, PD-L1 is amplified by PCR (EcoRI-PD-L1F: 5’-GCTGAATTCA CCATGAGGATATTTGCTGTCTT; EcoRV-PD-L1R-no-stop: 5’-ACAGATA TCG TCTC CTCCAAATGTGTATC-3’). The PCR product was cut by EcoRI/EcoRV and subsequently cloned into the EcoRI/EcoRV sites of pNLF1-C vector (Promega) expressing NanoLuc at C-terminal of protein.

4.3. Cell Culture and Establishment of Stable Line

HEK293A (human embryonic kidney cells), HEK293T, and Hs578T were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Sigma D6429). BT549 was cultured in Roswell Memorial Institute-1640 (RPMI-1640; Sigma R8758). All above mentioned cells were cultured in medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen) as antibiotics.

For establishment of cell line stably expressing PD-L1-NL, HEK293A cells were transiently transfected with PD-L1/pNLF1-C, followed by hygromycin (400 μg/ml) treatment and clonal selection. Different clones were isolated, expanded, and subjected to western blot analysis and luciferase assays.

4.4. Kinome-Wide Kinase Inhibitor Screen and Drug Validation

Kinome-wide kinase inhibitor screen is as described previously [

20]. HEK293A-PD-L1-NL cells were used in the screen.

4.5. NanoLuc Luciferase Assay

Approximately 1 × 10⁴ HEK293A-pNLF-PD-L1-C20 cells were seeded in triplicate into each well of a 96-well plate 24 hours prior to treatment. Cells were then treated with increasing concentrations of the indicated drugs. After 24 hours, Nano-Glo® Live Cell Reagent (Promega), containing the cell-permeable furimazine substrate, was added directly to each well. Luminescence was immediately measured using a Promega™ GloMax® Plate Reader.

4.6. RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

RNA extraction, quantification, and qRT-PCR are as described[

20]. For internal control, 18S rRNA was used. The following primers are used in qPCR: rRNA, sense: 5′-TCCCCATGAACGAGGAATTCC-3′, anti-sense:5′-AACCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGC-3’; PD-L1, sense: 5’-GGCATTTGCTGAACGCAT-3’, anti-sense:5’-CAATTAGTGCA GCCAGGT-3’.

4.7. Knockdown of FAK by Short Interference RNA (siRNA)

Knockdown of FAK by siRNA were performed as described as previously[

38] siFAKs were purchased from IDT. siFAK sequences are the following: siFAK-1: sense, 5’-AAGCCAACATTGAAUUUCUUCUATC-3’; anti-sense, 5’-GAUAGAAGAAAUUCA AUGUUGGCUUAU-3’; siFAK-2: 5’-AAGACAGTACTTACTATAAAGCTTC-3’; anti-sense: 5’-GAAGCTTTAUAGTAAGTACTGTCTCC-3’.

4.8. Immunoblotting, co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP), and Antibodies

Immunoblotting and Co-IP were carried out as described previously[

21]. Briefly, cells grown to 70% to 80% confluency were harvested in RIPA/1% NP-40 lysis buffer. Protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with respective antibodies using standard protocols. For Co-IP, cells expressing different genes were harvested in 1% NP-40 lysis buffer. After checking the expression of different proteins, equal amounts of proteins were precleared overnight at 4°C using Protein A/G-agarose. The supernatant was subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-HA-F7 or FLAG-M2 antibodies for 2 hours at 4°C. After the incubation, 20 μl of Protein A/G-agarose was added for an additional 1 hour. The beads were washed four times with 150 mM NaCl-1% NP-40 lysis buffer, suspended in 20 μl of 2x SDS sample buffer, boiled for 5 minutes, and centrifuged. The supernatants were run on SDS-PAGE and blotted with respective antibodies. The antibodies used for Western blot analysis were as follows: PD-L1 (E1L3N), anti-FLAG-M2, and β-actin from MilliporeSigma (Etobicoke, ON, Canada); antibodies against HA-F7 and FAK (D-1) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); and mouse monoclonal anti-Myc (9E10) from Roche (Mississauga, ON, Canada). Densitometry calculations were done using the adjusted volume calculated in the ImageLab 6.1 software (Bio-Rad) and dividing the sample adjusted volume to β-actin’s adjusted volume resulting in the relative increase of PD-L1 protein expression.

4.9. Flow Activating Cell Sorting (FACS) Analysis of Membrane PD-L1

FACS analysis of membrane PD-L1 was conducted following a standard protocol provided by Abcam. A PE-conjugated anti-human PD-L1 antibody (clone MIH1, eBioscience) was used for detection, with mouse IgG1 (clone B11/6, Abcam) serving as the isotype control. Briefly, 1 × 10⁶ cells were resuspended in 100 μL of staining buffer containing either the control IgG or APC-conjugated anti-PD-L1 antibody (diluted 1:100), and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes on a rotator in the dark. After staining, cells were washed three times with 250 μL of staining buffer. Following centrifugation, the cell pellets were resuspended in 0.5 mL of Cell Staining Buffer, filtered through a 35 μm cell strainer (VWR), and maintained on ice in the dark until analysis. Flow cytometry was performed using a Beckman Coulter CytoFlex S instrument.

4.10. Immune Evasion Assays In Vitro

To enable co-culture assays, BT549 cells were labeled with red fluorescence via infection with a lentivirus expressing mCherry. Jurkat T cells were activated by treatment with anti-CD3 antibody (200 ng/mL) and IL-2 (20 ng/mL) for 12 hours to induce PD-1 expression prior to co-culture. Triplicates of 2 × 10⁴ cancer cells were seeded into each well of a 96-well plate. After overnight incubation, approximately 2 × 10⁶ activated Jurkat T cells were added to each well containing cancer cells, followed by the addition of Incucyte® Caspase-3/7 Apoptosis Reagent (Green dye, 5 μM; Sartorius, Cat#4440). Cancer cell killing was monitored and quantified by immunofluorescence imaging over 24 hours using the CellCyte system (CYTENA). Red fluorescence indicated live cancer cells, while green fluorescence indicated apoptotic (dead) cells. The percentage of green (dead) cells relative to the total cell population (green + red) was calculated along with standard deviation.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis were performed using the Prism 10 program.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, X.Y.; methodology, A.B., P.K., T.K., Y.H.; formal analysis, A.B., P.K., T.K., Y.H.; investigation, A.B., P.K, T.K., Y.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B., X.Y.; writing—review and editing, A.B; supervision, X.Y.; project administration, Y.H.; funding acquisition, X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research was funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR), grant numbers 186142 and 148629.

Informed Consent Statement

Any research article describing a study involving humans should contain this statement. Please add “Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” OR “Patient consent was waived due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable.” for studies not involving humans. You might also choose to exclude this statement if the study did not involve humans.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank SMART Laboratory for High-Throughput Screening Programs of the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute (Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto) for HTS screen for kinases regulating PD-L1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AKT |

Protein Kinase B |

| ALK |

Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase |

| APC |

Allophycocyanin (fluorescent dye) |

| BTK |

Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase |

| CDK |

Cyclin-Dependent Kinase |

| CK2 |

Casein Kinase 2 |

| Co-IP |

Co-immunoprecipitation |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| FACS |

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting |

| FAK |

Focal Adhesion Kinase |

| FDA |

U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| FGFR |

Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor |

| GSK3 |

Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 |

| HA |

Hemagglutinin (epitope tag) |

| HEK293A |

Human Embryonic Kidney 293A cells |

| HTS |

High Throughput Screening |

| ICI |

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor |

| IL2 |

Interleukin 2 |

| MAPK |

Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| NL |

NanoLuc |

| NP-40 |

Nonidet P-40 (detergent) |

| NanoLuc |

NanoLuciferase |

| ORF |

Open Reading Frame |

| PBS |

Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| PD-1 |

Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 |

| PD-L1 |

Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| PDX |

Patient-Derived Xenograft |

| PE |

Phycoerythrin (fluorescent dye) |

| PI3K |

Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| RIPA |

Radioimmunoprecipitation Assay buffer |

| ROCK |

Rho-associated Protein Kinase |

| TAZ |

Transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif |

| TNBC |

Triple Negative Breast Cancer |

| VEGFR |

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor |

| WT |

Wild-Type |

| mTOR |

Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin |

| qRT-PCR |

Quantitative Real-Time PCR |

| siFAK |

siRNA targeting FAK |

| siRNA |

Small Interfering RNA |

References

- Almozyan, S.; Colak, D.; Mansour, F.; Alaiya, A.; Al-Harazi, O.; Qattan, A.; Al-Mohanna, F.; Al-Alwan, M.; Ghebeh, H. PD-L1 promotes OCT4 and Nanog expression in breast cancer stem cells by sustaining PI3K/AKT pathway activation. International journal of cancer 2017, 141, 1402–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, M.; Barsoum, I.B.; Truesdell, P.; Cotechini, T.; Macdonald-Goodfellow, S.K.; Petroff, M.; Siemens, D.R.; Koti, M.; Craig, A.W.; Graham, C.H. Activation of the PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint confers tumor cell chemoresistance associated with increased metastasis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 10557–10567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.A.; Gupta, H.B.; Curiel, T.J. Tumor cell-intrinsic CD274/PD-L1: A novel metabolic balancing act with clinical potential. Autophagy 2017, 13, 987–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.A.; Gupta, H.B.; Sareddy, G.; Pandeswara, S.; Lao, S.; Yuan, B.; Drerup, J.M.; Padron, A.; Conejo-Garcia, J.; Murthy, K.; Liu, Y.; Turk, M.J.; Thedieck, K.; Hurez, V.; Li, R.; Vadlamudi, R.; Curiel, T.J. Tumor-Intrinsic PD-L1 Signals Regulate Cell Growth, Pathogenesis, and Autophagy in Ovarian Cancer and Melanoma. Cancer research 2016, 76, 6964–6974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Xia, Y.; Hu, X.; Guo, J. PD-L1 induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via activating SREBP-1c in renal cell carcinoma. Medical oncology (Northwood, London, England) 2015, 32, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Chen, D.S. Immune escape to PD-L1/PD-1 blockade: seven steps to success (or failure). Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2016, 27, 1492–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardoll, D.M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nature reviews.Cancer 2012, 12, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.S.; Mellman, I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity 2013, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.S.; Mellman, I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer-immune set point. Nature 2017, 541, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmaninejad, A.; Valilou, S.F.; Shabgah, A.G.; Aslani, S.; Alimardani, M.; Pasdar, A.; Sahebkar, A. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway: Basic biology and role in cancer immunotherapy. Journal of cellular physiology 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, J.; Lim, K.S.; Mekhail, T.; Chang, C.C. Programmed Death Ligand-1 (PD-L1) Expression in the Programmed Death Receptor-1 (PD-1)/PD-L1 Blockade: A Key Player Against Various Cancers. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 2017, 141, 851–861. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside, T.L.; Demaria, S.; Rodriguez-Ruiz, M.E.; Zarour, H.M.; Melero, I. Emerging Opportunities and Challenges in Cancer Immunotherapy. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2016, 22, 1845–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.C.; Duffy, C.R.; Allison, J.P. Fundamental Mechanisms of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy. Cancer discovery 2018, 8, 1069–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PD-1/PD-L1 landscape (https://www.cancerresearch.org/scientists/clinical-accelerator/landscape-of-immuno-oncology-drug-development/pd-1-pd-l1-landscape). Cancer Research Institute, 2019.

- Ribas, A.; Wolchok, J.D. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science 2018, 359, 1350–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Dewanjee, S.; Li, Y.; Jha, N.K.; Chen, Z.S.; Kumar, A.; Vishakha; Behl, T.; Jha, S.K.; Tang, H. Advancements in clinical aspects of targeted therapy and immunotherapy in breast cancer. Mol Cancer 2023, 22, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, L.; Okines, A. Systemic Therapy for Metastatic Triple Negative Breast Cancer: Current Treatments and Future Directions. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lastwika, K.J.; Wilson, W., 3rd; Li, Q.K.; Norris, J.; Xu, H.; Ghazarian, S.R.; Kitagawa, H.; Kawabata, S.; Taube, J.M.; Yao, S.; Liu, L.N.; Gills, J.J.; Dennis, P.A. Control of PD-L1 Expression by Oncogenic Activation of the AKT-mTOR Pathway in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer research 2016, 76, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janse van Rensburg, H.J.; Azad, T.; Ling, M.; Hao, Y.; Snetsinger, B.; Khanal, P.; Minassian, L.M.; Graham, C.H.; Rauh, M.J.; Yang, X. The Hippo pathway component TAZ promotes immune evasion in human cancer through PD-L1. Cancer Research 2018, 78, 1457–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rensburg, H.; Azad, T.; Ling, M.; Hao, Y.; Snetsinger, B.; Khanal, P.; Minassian, L.; Graham, C.; Raul, M.; Yang, X. The Hippo pathway component TAZ promotes immune evasion in human cancer through PD-L1. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 1457–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wei, Y.; Chu, Y.Y.; Li, Y.; Hsu, J.M.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, C.; Hsu, J.L.; Chang, W.C.; Yang, R.; Chan, L.C.; Qu, J.; Zhang, S.; Ying, H.; Yu, D.; Hung, M.C. Phosphorylation and Stabilization of PD-L1 by CK2 Suppresses Dendritic Cell Function. Cancer Res 2022, 82, 2185–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, F.; Su, Y.; Xu, B. Rho-associated protein kinase-dependent moesin phosphorylation is required for PD-L1 stabilization in breast cancer. Mol Oncol 2020, 14, 2701–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Green, M.D.; Lang, X.; Lazarus, J.; Parsels, J.; Wei, S.; Parsels, L.A.; Shi, J.; Ramnath, N.; Wahl, D.R.; Pasca di Magliano, M.; Frankel, T.L.; Kryczek, I.; Lei, Y.; Lawrence, T.S.; Zou, W.; Morgan, M.A. Inhibition of ATM increases interferon signaling and sensitizes pancreatic cancer to immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Res 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasikara, C.; Davra, V.; Calianese, D.; Geng, K.; Spires, T.E.; Quigley, M.; Wichroski, M.; Sriram, G.; Suarez-Lopez, L.; Yaffe, M.B.; Kotenko, S.V.; De Lorenzo, M.S.; Birge, R.B. Pan-TAM Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor BMS-777607 Enhances Anti-PD-1 mAb Efficacy in a Murine Model of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Res 2019, 79, 2669–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, J.M.; Li, C.W.; Lai, Y.J.; Hung, M.C. Posttranslational Modifications of PD-L1 and Their Applications in Cancer Therapy. Cancer research 2018, 78, 6349–6353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Ge, S.; Xie, Y.; Sun, R.; Wu, Y.; Xu, J. The regulatory role of CDK4/6 inhibitors in tumor immunity and the potential value of tumor immunotherapy (Review). Int J Mol Med 2025, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Aranda, M.; Redondo, M. Targeting Protein Kinases to Enhance the Response to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 Immunotherapy. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, E2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulzmaier, F.J.; Jean, C.; Schlaepfer, D.D. FAK in cancer: mechanistic findings and clinical applications. Nat Rev Cancer 2014, 14, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.W.; Lim, S.O.; Xia, W.; Lee, H.H.; Chan, L.C.; Kuo, C.W.; Khoo, K.H.; Chang, S.S.; Cha, J.H.; Kim, T.; Hsu, J.L.; Wu, Y.; Hsu, J.M.; Yamaguchi, H.; Ding, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yao, J.; Lee, C.C.; Wu, H.J.; Sahin, A.A.; Allison, J.P.; Yu, D.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Hung, M.C. Glycosylation and stabilization of programmed death ligand-1 suppresses T-cell activity. Nature communications 2016, 7, 12632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Guan, J.L. Focal adhesion kinase: a prominent determinant in breast cancer initiation, progression and metastasis. Cancer letters 2010, 289, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Yan, Y.; Song, B.; Zhu, S.; Mei, Q.; Wu, K. Focal adhesion kinase: from biological functions to therapeutic strategies. Exp Hematol Oncol 2023, 12, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.X.; Cao, Y.Y.; Xu, L.S.; Wang, H.C.; Liu, X.H.; Zhu, H.L. FAK inhibitors in cancer, a patent review - an update on progress. Expert Opin Ther Pat 2024, 34, 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glénisson, M.; Vacher, S.; Callens, C.; Susini, A.; Cizeron-Clairac, G.; Le Scodan, R.; Meseure, D.; Lerebours, F.; Spyratos, F.; Lidereau, R.; Bièche, I. Identification of new candidate therapeutic target genes in triple-negative breast cancer. Genes Cancer 2012, 3, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golubovskaya, V.M.; Ylagan, L.; Miller, A.; Hughes, M.; Wilson, J.; Wang, D.; Brese, E.; Bshara, W.; Edge, S.; Morrison, C.; Cance, W.G. High focal adhesion kinase expression in breast carcinoma is associated with lymphovascular invasion and triple-negative phenotype. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, N.; Hosain, S.; Zhao, J.; Shen, Y.; Luo, X.; Jiang, J.; Endo, Y.; Wu, W.J. Atezolizumab potentiates Tcell-mediated cytotoxicity and coordinates with FAK to suppress cell invasion and motility in PD-L1(+) triple negative breast cancer cells. Oncoimmunology 2019, 8, e1624128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiede, S.; Meyer-Schaller, N.; Kalathur, R.K.R.; Ivanek, R.; Fagiani, E.; Schmassmann, P.; Stillhard, P.; Häfliger, S.; Kraut, N.; Schweifer, N.; Waizenegger, I.C.; Bill, R.; Christofori, G. The FAK inhibitor BI 853520 exerts anti-tumor effects in breast cancer. Oncogenesis 2018, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Xia, W.; Yamaguchi, H.; Wei, Y.; Chen, M.K.; Hsu, J.M.; Hsu, J.L.; Yu, W.H.; Du, Y.; Lee, H.H.; Li, C.W.; Chou, C.K.; Lim, S.O.; Chang, S.S.; Litton, J.; Arun, B.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Hung, M.C. PARP Inhibitor Upregulates PD-L1 Expression and Enhances Cancer-Associated Immunosuppression. Clin Cancer Res 2017, 23, 3711–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, T.; Janse van Rensburg, H.J.; Lightbody, E.D.; Neveu, B.; Champagne, A.; Ghaffari, A.; Kay, V.R.; Hao, Y.; Shen, H.; Yeung, B.; Croy, B.A.; Guan, K.L.; Pouliot, F.; Zhang, J.; Nicol, C.J.B.; Yang, X. A LATS biosensor functional screen identifies VEGFR as a novel regulator of the Hippo pathway in angiogenesis. Nat.Commun. 2018, 9, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Establishing a HEK293A cell line stably expressing PD-L1-NL to monitor PD-L1 stability. A. Schematic representation of PD-L1 and PD-L1-NL construct. NL, NanoLuc; SP, signal peptide; ECD, extracellular domain; TM, transmembrane domain; ICD, intracellular domain. B. WB analysis of PD-L1-NL expression in different clones (C19, C10, C12) using anti-PD-L1 antibody. C. Luciferase activity of HEK293A clones (C19, C10, C12) expressing different levels of PD-L1-N. D. E. Dose-dependent reduction of PD-L1 stability by GSK3β inhibitor in HEK293A-PD-L1-NL cells. HEK293A-PD-L1-NL cells were treated at increasing concentration (0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.5 μM) of GSK3β inhibitor for 1 day, followed by luciferase assays (D) and western blot analysis (E). Statistical analysis for luciferase assays (D): ***, p<0.001; ****, p<0.0001. Ponceau S staining of proteins on membrane was used as protein loading control (E).

Figure 1.

Establishing a HEK293A cell line stably expressing PD-L1-NL to monitor PD-L1 stability. A. Schematic representation of PD-L1 and PD-L1-NL construct. NL, NanoLuc; SP, signal peptide; ECD, extracellular domain; TM, transmembrane domain; ICD, intracellular domain. B. WB analysis of PD-L1-NL expression in different clones (C19, C10, C12) using anti-PD-L1 antibody. C. Luciferase activity of HEK293A clones (C19, C10, C12) expressing different levels of PD-L1-N. D. E. Dose-dependent reduction of PD-L1 stability by GSK3β inhibitor in HEK293A-PD-L1-NL cells. HEK293A-PD-L1-NL cells were treated at increasing concentration (0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.5 μM) of GSK3β inhibitor for 1 day, followed by luciferase assays (D) and western blot analysis (E). Statistical analysis for luciferase assays (D): ***, p<0.001; ****, p<0.0001. Ponceau S staining of proteins on membrane was used as protein loading control (E).

Figure 2.

HTS for kinase inhibitors regulating PD-L1 stability. A. Flow diagram of kinome wide kinase inhibitor screening. B. Results of kinome-wide kinase inhibitors screening. The data represent ratios of relative light units (RLUs) of inhibitor-treated to those of DMSO control. C. Validation of potential kinase inhibitors using luciferase assay. Statistical analysis: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ****, p<0.0001. D. Western blot analysis of PD-L1-NL expression in HEK293A cells. HEK293A-PD-L1-NL cells were treated with 5 µM for 1 day, followed by western blot analysis. Protein on the membrane was stained with Ponceau S as protein loading control.

Figure 2.

HTS for kinase inhibitors regulating PD-L1 stability. A. Flow diagram of kinome wide kinase inhibitor screening. B. Results of kinome-wide kinase inhibitors screening. The data represent ratios of relative light units (RLUs) of inhibitor-treated to those of DMSO control. C. Validation of potential kinase inhibitors using luciferase assay. Statistical analysis: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ****, p<0.0001. D. Western blot analysis of PD-L1-NL expression in HEK293A cells. HEK293A-PD-L1-NL cells were treated with 5 µM for 1 day, followed by western blot analysis. Protein on the membrane was stained with Ponceau S as protein loading control.

Figure 3.

Validation of FAKi-induced PD-L1 degradation in HEK293A cells. A. Dose-dependent effect of FAKi PF431396 on PD-L1 stability. Lower panel: western blot analysis. Upper panel: luciferase assay. Statistical analysis: ***, p<0.001; ****, p<0.0001. B. Dose-dependent effect of FAKi Defactinib on PD-L1 stability. Lower panel: western blot analysis. Upper panel: luciferase assay. Statistical analysis: ****, p<0.0001. C. FACS analysis of the effect of various FAKi on membrane PD-L1. D. Dose-dependent effect of FAK on PD-L1 stability. E. Kinase activity independent effect of FAK on PD-L1 stability.

Figure 3.

Validation of FAKi-induced PD-L1 degradation in HEK293A cells. A. Dose-dependent effect of FAKi PF431396 on PD-L1 stability. Lower panel: western blot analysis. Upper panel: luciferase assay. Statistical analysis: ***, p<0.001; ****, p<0.0001. B. Dose-dependent effect of FAKi Defactinib on PD-L1 stability. Lower panel: western blot analysis. Upper panel: luciferase assay. Statistical analysis: ****, p<0.0001. C. FACS analysis of the effect of various FAKi on membrane PD-L1. D. Dose-dependent effect of FAK on PD-L1 stability. E. Kinase activity independent effect of FAK on PD-L1 stability.

Figure 4.

Loss of FAK increases PD-L1 stability in BT549 cells. A. Western blot analysis of PD-L1. BT549 cells were treated with 0, 5, 10, and 20 µM of Defactinib for 1 day. Protein on the membrane was stained with Ponceau S Stain. Stained protein was used as loading control. B. Western blot analysis of PD-L1 in BT549 cells after an siRNA-mediated FAK knockdown. C. FACS analysis of the effect of 5 µM of Defactinib on membrane PD-L1 in BT549 cells. β-actin was used as a control. Densitometry calculations were done using the adjusted band density calculated in ImageLab to compare the PD-L1 expression by dividing the adjusted band density of the siFAK samples by that of β-actin’s adjusted density, resulting in the relative increase of PD-L1 protein expression. D. FACS analysis of the effect of siFAK on membrane PD-L1 in BT549 cells.

Figure 4.

Loss of FAK increases PD-L1 stability in BT549 cells. A. Western blot analysis of PD-L1. BT549 cells were treated with 0, 5, 10, and 20 µM of Defactinib for 1 day. Protein on the membrane was stained with Ponceau S Stain. Stained protein was used as loading control. B. Western blot analysis of PD-L1 in BT549 cells after an siRNA-mediated FAK knockdown. C. FACS analysis of the effect of 5 µM of Defactinib on membrane PD-L1 in BT549 cells. β-actin was used as a control. Densitometry calculations were done using the adjusted band density calculated in ImageLab to compare the PD-L1 expression by dividing the adjusted band density of the siFAK samples by that of β-actin’s adjusted density, resulting in the relative increase of PD-L1 protein expression. D. FACS analysis of the effect of siFAK on membrane PD-L1 in BT549 cells.

Figure 5.

Loss of FAK increases PD-L1 stability in Hs578T cells. A. Western blot analysis of PD-L1 in Hs578T cells were treated with 0, 5, 10, and 20 µM of Defactinib for 1 day. Protein on the membrane was stained with Ponceau S. Stained protein was used as loading control. B. Western blot analysis of PD-L1 in Hs578T cells after an siRNA-mediated FAK knockdown. β-actin was used as a control. Densitometry analysis was as described in Fig. 4C legend. C. FACS analysis of the effect of 5 µM of Defactinib on membrane PD-L1 in Hs578T cells. D. FACS analysis of the effect of siFAK on membrane PD-L1 in Hs578T cells.

Figure 5.

Loss of FAK increases PD-L1 stability in Hs578T cells. A. Western blot analysis of PD-L1 in Hs578T cells were treated with 0, 5, 10, and 20 µM of Defactinib for 1 day. Protein on the membrane was stained with Ponceau S. Stained protein was used as loading control. B. Western blot analysis of PD-L1 in Hs578T cells after an siRNA-mediated FAK knockdown. β-actin was used as a control. Densitometry analysis was as described in Fig. 4C legend. C. FACS analysis of the effect of 5 µM of Defactinib on membrane PD-L1 in Hs578T cells. D. FACS analysis of the effect of siFAK on membrane PD-L1 in Hs578T cells.

Figure 6.

Quantitative Real-Time qRT-PCR analysis of TNBC cell lines after siRNA-mediated FAK knockdown. Relative change of PD-L1 RNA levels before (Wild-type) and after siFAK-mediated FAK knockdown (siFAK) in BT549 and Hs578T cells. Statistical analysis: **, p<0.01.

Figure 6.

Quantitative Real-Time qRT-PCR analysis of TNBC cell lines after siRNA-mediated FAK knockdown. Relative change of PD-L1 RNA levels before (Wild-type) and after siFAK-mediated FAK knockdown (siFAK) in BT549 and Hs578T cells. Statistical analysis: **, p<0.01.

Figure 7.

PD-L1 interacts with FAK in vivo. (A and B) PD-L1 interacts with FAK in vivo. PD-L1 stably overexpressed HEK-293A-pNLF1C-PDL-1 cells were transfected with MYC-tagged-FAK plasmids. The cells were harvested in 1% NP-40 lysis buffer. After checking the expression level of MYC-tagged-FAK or PD-L1, equal amount of cell lysates was subjected to co-immunoprecipitation assays using anti-rabbit-IgG or anti-MYC antibody (A) and anti-rabbit or anti-PD-L1 antibodies (B) respectively and immunoblotting analysis were performed using anti-PD-L1 or anti-FAK antibody respectively. (C and D) PD-L1 interacts with FAK in vivo. HEK-293A cells were transfected with MYC-tagged-FAK plasmids or SFB-tagged PD-L1 alone or together. The cells were harvested in 1% NP-40 lysis buffer. After checking the expression level of MYC-tagged-FAK or FALG-PD-L1, equal amount of cell lysates was subjected to co-immunoprecipitation assays using anti-FLAG antibody (C) or anti-MYC antibody (D) and immunoblotting analysis were performed using anti-MYC or anti-FLAG antibody, respectively.

Figure 7.

PD-L1 interacts with FAK in vivo. (A and B) PD-L1 interacts with FAK in vivo. PD-L1 stably overexpressed HEK-293A-pNLF1C-PDL-1 cells were transfected with MYC-tagged-FAK plasmids. The cells were harvested in 1% NP-40 lysis buffer. After checking the expression level of MYC-tagged-FAK or PD-L1, equal amount of cell lysates was subjected to co-immunoprecipitation assays using anti-rabbit-IgG or anti-MYC antibody (A) and anti-rabbit or anti-PD-L1 antibodies (B) respectively and immunoblotting analysis were performed using anti-PD-L1 or anti-FAK antibody respectively. (C and D) PD-L1 interacts with FAK in vivo. HEK-293A cells were transfected with MYC-tagged-FAK plasmids or SFB-tagged PD-L1 alone or together. The cells were harvested in 1% NP-40 lysis buffer. After checking the expression level of MYC-tagged-FAK or FALG-PD-L1, equal amount of cell lysates was subjected to co-immunoprecipitation assays using anti-FLAG antibody (C) or anti-MYC antibody (D) and immunoblotting analysis were performed using anti-MYC or anti-FLAG antibody, respectively.

Figure 8.

PD-L1 regulation by FAK regulates breast cancer immune evasion. A. Treatment of 20 ng/mL IL-2 and 200 ng/mL of anti-CD3 for 12, 24, and 48 hours induces the PD-1 expression in Jurkat T cells. B. Dead cells: total cells ratio of T cell killing at in wildtype and 5 µM Defactinib treatment in BT549-mCherry cells at a 2.5:1 effector to target cell ratio. Statistical analysis: *, p<0.01. C. Fluorescence of live cells (mCherry, red) and dead cells (FITC incucyte caspase– 3/7, green) in BT549-mCherry cells at a 4x magnification. D. Dead cells: total cells ratio of T cell killing at in wild-type siRNA-mediated FAK knockdown in BT549-mCherry cells at a 2.5:1 effector to target cell ratio. Statistical analysis: *, p<0.01. E. Fluorescence of live cells (mCherry, red) and dead cells (FITC incucyte caspase – 3/7, green) in BT549-mCherry cells at a 4x magnification.

Figure 8.

PD-L1 regulation by FAK regulates breast cancer immune evasion. A. Treatment of 20 ng/mL IL-2 and 200 ng/mL of anti-CD3 for 12, 24, and 48 hours induces the PD-1 expression in Jurkat T cells. B. Dead cells: total cells ratio of T cell killing at in wildtype and 5 µM Defactinib treatment in BT549-mCherry cells at a 2.5:1 effector to target cell ratio. Statistical analysis: *, p<0.01. C. Fluorescence of live cells (mCherry, red) and dead cells (FITC incucyte caspase– 3/7, green) in BT549-mCherry cells at a 4x magnification. D. Dead cells: total cells ratio of T cell killing at in wild-type siRNA-mediated FAK knockdown in BT549-mCherry cells at a 2.5:1 effector to target cell ratio. Statistical analysis: *, p<0.01. E. Fluorescence of live cells (mCherry, red) and dead cells (FITC incucyte caspase – 3/7, green) in BT549-mCherry cells at a 4x magnification.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).