1. Introduction

Terpenoids, a vast and structurally diverse class of natural products, underpin numerous life-saving pharmaceuticals, impacting global healthcare. Traditional sourcing of pharmaceutical terpenoids from native plants is plagued by a confluence of challenges: unsustainable yields often below 0.05% dry weight, lengthy growth cycles such as 5 to 7 years for Panax ginseng, environmental instability leading to inconsistent biochemical profiles, and ecological damage due to over-harvesting (Atanasov et al., 2015; Atanasov et al., 2021). Metabolic engineering offers a sustainable alternative by enabling enhanced production in three complementary platforms: (1) Native medicinal plants, allowing for optimized in plant biosynthesis while retaining desirable genetic context (Zhang et al., 2004); (2) Microbial chassis like bacteria and yeast, offering rapid growth, well-established genetic tools, and scalable fermentation (Volk et al., 2022); and (3) Heterologous plant hosts such as Nicotiana benthamiana, providing eukaryotic post-translational modifications and complex subcellular compartmentalization capabilities (D.-K. Ro et al., 2006; Ye et al., 2000).

A “Genomic Insights to Biotechnological Applications” paradigm drives contemporary advancements in terpenoid production. Multi-omics technologies systematically decode biosynthetic pathways, providing a foundation for targeted engineering. Genome mining identified taxadiene synthase (TASY), the gateway enzyme for paclitaxel biosynthesis in Taxus species (Jennewein et al., 2004). Transcriptomic analyses revealed jasmonate-induced expression patterns of artemisinin pathway genes in Artemisia annua, guiding strategies for pathway activation (Ma et al., 2009). Heterologous expression, complemented by proteomics and metabolomics, allows pathway reconstitution and validation of gene functions, as demonstrated by the reconstitution of Panax ginseng ginsenoside pathways in yeast chassis systems (Dai et al., 2013). Building on genomic insights, next-generation toolkits enable platform-optimized interventions. Research has shown that the CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of competing pathways in plants boosts production, demonstrating the power of in planta metabolic rewiring (Courdavault et al., 2021).

Persistent challenges remain, including balancing metabolic flux in complex networks, cytotoxicity of oxidized terpenoid intermediates in microbial hosts, limited availability of cytochrome P450 enzymes with desired regio- and stereo-selectivity, and scale-up limitations such as high production costs associated with plant cell culture. Future progress hinges on three frontiers: (1) Systems biology integration, especially genome-scale metabolic modeling for predictive pathway design (Chung et al., 2021); (2) Development of photoautotrophic chassis to reduce carbon dependency and enhance sustainability (Tharasirivat and Jantaro, 2023); and (3) Economically sustainable bioprocessing platforms enabling commercial deployment (Cao et al., 2023). This review will synthesize cross-platform metabolic engineering, systems biology, and bioprocessing advances, highlighting strategies to accelerate the transition from genomic discovery to industrial-scale terpenoid biomanufacturing.

2. The Basics of Terpene Biosynthesis in Medicinal Plants: Pathways and Regulation

2.1. Core Pathways: From Precursors to Structural Diversification

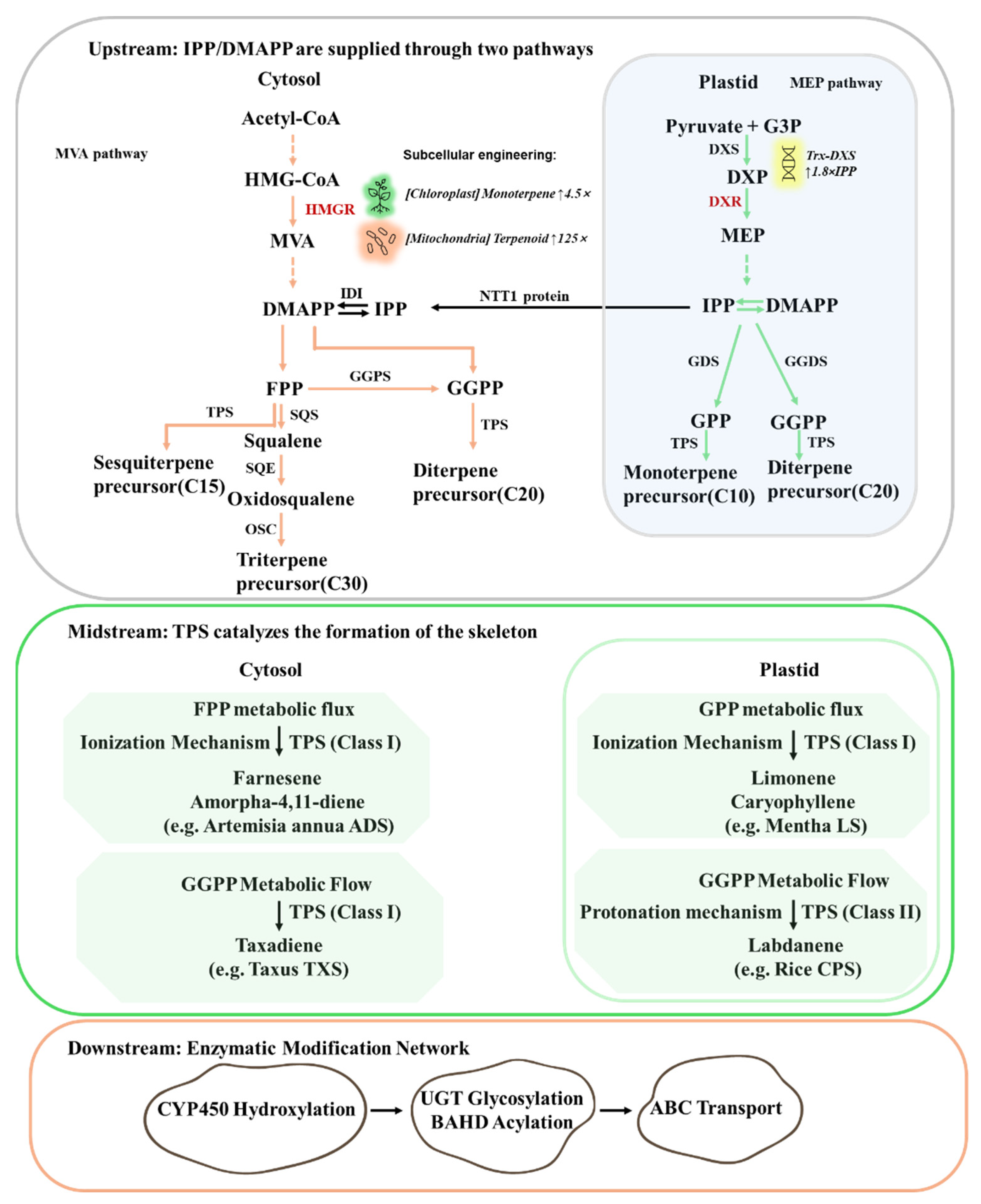

Terpenoid biosynthesis initiates with the formation of universal C

5 precursors, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP), through two spatially segregated pathways in medicinal plants (

Figure 1). The cytosolic mevalonate (MVA) pathway utilizes acetyl-CoA to generate farnesyl diphosphate (FPP, C

15), the precursor for sesquiterpenes (C

15) and triterpenes (C

30). Its rate-limiting enzyme, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR), is tightly regulated by sterol-mediated feedback inhibition. Recent studies on metabolic engineering in

A. annua indicate that targeted overexpression of rate-limiting enzymes HMGR can optimize metabolic flux toward artemisinin biosynthesis. Overexpressing HMGR can specifically enhance carbon allocation towards sesquiterpenes. When HMGR from

Catharanthus roseus (CrHMGR) is introduced into

A. annua, the artemisinin yield increases by 22.5% to 38.9% compared to non-transgenic controls (Y. Li et al., 2024a). Concurrently, the plastidial methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway catalyzes the condensation of pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate to form 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate (DXP), which is then converted to IPP/DMAPP, supplying precursors for monoterpenes (GPP, C

10) and diterpenes (GGPP, C

20). The enzyme catalyzing the first committed and rate-limiting step of this pathway, DXP synthase (DXS), is therefore crucial for determining flux through the MEP pathway. This pathway is modulated by light, with DXS being a key regulatory target. In

A. annua, the blue-light receptor AaCRY1 phosphorylates and activates AaDXS, enhancing artemisinin precursor synthesis (Hong et al., 2009). A critical adaptation in medicinal plants is cross-compartment synergy. IPP derived from the plastidial MEP pathway is hypothesized to be exported to the cytosol via an as-yet-unidentified transporter, though the molecular mechanisms remain largely uncharacterized (Pick and Weber, 2014). Synthetic biology strategies can circumvent the limitations imposed by cytosolic metabolic competition. Relocalizing monoterpene synthases to the chloroplasts of

N. tabacum, leveraging their high endogenous levels of the GPP precursor, resulted in a 4.5-fold increase in monoterpene production compared to cytosolic localization (Sirirungruang et al., 2022). Furthermore, reconstructing the entire cytosolic mevalonate (MVA) pathway within chloroplasts significantly enhanced triterpenoid yields via compartmentalized metabolic channeling (Wu et al., 2012). Additionally, novel isopentenyl phosphate kinase (IPK) pathways offer simplified routes to IPP/DMAPP, requiring fewer steps and only ATP as a cofactor (Lange and Croteau, 1999; Qiu et al., 2022). Metabolic engineering strategies, including pathway modularization and key enzyme engineering, have significantly enhanced microbial terpenoid production. Notably, relocating the terpenoid biosynthetic pathway to the mitochondria in engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae yielded a 125-fold production increase. Similarly, an ERG20 enzyme fusion strategy achieved a 340-fold amplification in monoterpene yield. Furthermore, stepwise optimization of the endogenous mevalonate (MVA) pathway resulted in a 56-fold improvement in total terpenoid titer (Ignea et al., 2014; Ouyang et al., 2019; Promdonkoy et al., 2022).

Terpene synthases (TPSs) catalyze the cyclization of prenyl diphosphates (GPP, FPP, GGPP) into diverse carbon skeletons (

Figure 1). The TPS gene family drives the structural diversity of terpenoids through functional diversification. The genome of

Salvia miltiorrhiza is predicted to have a large number of TPS members, among which 6-8 core enzymes (SmCPS1/2/4/5, SmKSL1, SmSTPS1-3) have been functionally verified (Boutanaev et al., 2015; Trapp and Croteau, 2001). Notably, SmKSL1b specifically catalyzes the formation of the tanshinone precursor tanshinene (Li et al., 2017). Structure-guided engineering has refined catalytic specificity. The structure of taxadiene synthase (TcTS) resolved by X-ray crystallography (1.82 Å) indicates that its βγ domain regulates cyclization fidelity through a substrate confinement mechanism. Single-point mutations such as I571T in

Gossypium arboreum (+)-δ-cadinene synthase can alter the product spectrum (Lanier et al., 2023).

Post-skeleton modifications enhance bioactivity and stability. Cytochrome P450s (CYPs) introduce hydroxyl and other functional groups, significantly diversifying the chemical structures of plant secondary metabolites (

Figure 1). In

Tripterygium wilfordii, CYP82D family P450s have been shown to catalyze the key C14-hydroxylation reaction, which is an essential step in the biosynthetic pathway of triptolide, a potent anti-inflammatory compound (Yifeng Zhang et al., 2023). In

A. annua, the key enzyme AaCYP71AV1 is responsible for the conversion of amorpha-4,11-diene to artemisinic acid, a precursor to the antimalarial drug artemisinin (Tippmann et al., 2013). Glycosyltransferases (UGTs) and acyltransferases (ATs) further diversify products. PgUGT74AE2 catalyzed glycosylation enhances ginsenoside solubility (Lee et al., 2020), while LeSAT1 or LeAAT1 mediated acylation of shikonin with acetyl or isobutyryl groups augments anticancer activity.

2.2. Medicinal Plant-Specific Adaptations

Medicinal plants exhibit lineage-specific gene duplications to expand terpenoid diversity. Maize (Zea mays) contains numerous TPS genes, with subtle active-site variations in functionally divergent enzymes like TPS4 and TPS10 dictating distinct sesquiterpene product specificity (Köllner et al., 2020). Plants expand the chemical diversity of their terpenoids through lineage-specific gene duplications. This evolutionary mechanism is widespread across the plant kingdom and is of particular significance in numerous medicinal plants, forming the foundation for their rich array of medicinally active compounds.), itself a plant of medicinal value. Within Phaseolus lunatus’s genome, two tandemly duplicated cytochrome P450 genes, PlCYP82D47-like and PlCYP82D47, are induced by herbivorous insects (Li et al.). These enzymes catalyze the formation of the volatile indirect defense signals DMNT and TMTT via the oxidative cleavage of terpenoid alcohol precursors (Li et al.). The duplicated enzymes have functionally diverged, exhibiting distinct substrate preferences for (E)-nerolidol and (E,E)-geranyllinalool, respectively. Further molecular investigations reveal that key amino acid residues, such as L324 and L505 in the PlCYP82D47 enzyme, are crucial for maintaining its catalytic activity due to their critical role in substrate recognition (Li et al.). These residues thereby constitute the molecular basis of its substrate specificity.

The biosynthesis of terpenoid compounds often involves multiple cellular organelles, a process well-exemplified by the synthesis of paclitaxel in Taxus species. The pathway initiates inside the plastids, where taxadiene synthase (TcTS), a plastid-targeted enzyme catalyzes the formation of the core hydrocarbon skeleton, taxa-4(5),11(12)-diene (Heinig et al., 2013). This hydrophobic intermediate is then transported to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where a series of membrane-anchored cytochrome P450 enzymes, such as TcCYP725A4, perform numerous oxidative modifications on the taxane ring (Ishii et al., 2005; Patil et al., 2012). Subsequent acylation steps, including the critical C10-acetylation catalyzed by the soluble 10-deacetylbaccatin III-10-O-acetyltransferase (TcDBAT), occur in the cytosol (Walker and Croteau, 2000). To prevent self-toxicity from this potent microtubule-stabilizing agent, the final paclitaxel product is exported from the cytoplasm and sequestered primarily within the cell wall (Sykłowska-Baranek et al., 2018). The transport mechanisms that shuttle intermediates between the plastids, the ER, and the cytosol are essential to the pathway but are not yet fully elucidated, likely involving complex processes such as transport through membrane contact sites (Bellucci et al., 2018; Li-Beisson et al., 2013). Subcellular compartmentalization and transport play pivotal roles in plant secondary metabolism, where transporter proteins are indispensable. In Salvia miltiorrhiza (Danshen), the ABC transporter SmABCG1, localized in periderm cells of the roots, has been demonstrated to mediate the export of the active constituents, tanshinones, to the extracellular space. A study utilizing CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology revealed that functional knockout of the SmABCG1 gene resulted in a significant reduction in tanshinone content within both the hairy roots and their culture medium. This finding underscores the essential role of SmABCG1 in the efficient secretion of tanshinones and the maintenance of normal metabolic flux (Li et al., 2025). Such regulatory mechanisms are also observed in the evolution of Euphorbia species. Research has shown that peplusol synthase, derived from the duplication of steroid synthase genes, can enable the efficient heterologous production of linear triterpenoids in yeast, achieving yields of up to 30 mg/L (Czechowski et al., 2025).

2.3. Multilayer Regulatory Networks

Transcription factors (TFs) play a crucial role in coordinating terpenoid pathways, responding to various developmental and environmental cues. Among the key TF families involved are AP2/ERF, bHLH, and MYB (Yi et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2018). The JA-responsive bHLH transcription factor AaMYC2 directly activates artemisinin biosynthesis by binding promoters of CYP71AV1 and DBR2, with overexpression increasing artemisinin production by >2-fold (Ma et al., 2021). Among MYB family members, AaMYB1 enhances artemisinin yields by upregulating ADS and CYP71AV1 expression and increasing glandular trichome density (Matías-Hernández et al., 2017). Hormonal crosstalk fine-tunes specialized metabolism: Jasmonate (JA) induces artemisinin synthesis by degrading JAZ repressors (e.g., AaJAZ8/9) to derepress transcriptional activators like the TCP14-ORA complex, while salicylic acid (SA) antagonizes JA signaling downstream of JAZ degradation (Li et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2018). Non-coding RNAs add regulatory layers. Cro-miR156a cleaves CrSPL2/5 mRNAs to repress terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus (Zhang et al., 2025). CRISPR editing of miR156 binding sites shows potential to enhance yields (Das et al., 2024).

PTMs dynamically regulate enzyme activity. SnRK1-mediated phosphorylation of HMGR at Ser-577 inactivates the enzyme to modulate flux (Leivar et al., 2011), while ubiquitination controls transcription factor stability. Feedback inhibition is a critical engineering target. FPP accumulation inhibits HMGR, but expressing truncated yeast tHMGR circumvents this. In engineered yeast, the expression of tHMGR can increase the yield of terpenoids, raising patchoulol by 36% and amorphadiene, the precursor of artemisinin, by five times (Gruchattka and Kayser, 2015; Liu et al., 2022). Expressing soluble CrHMGR (from Catharanthus roseus) in A. annua elevates artemisinin 22-38% (Tang et al., 2023). Similarly, artemisinin overproduction activates jasmonate signaling; overexpression of key transcription factors enhances artemisinin synthesis >2-fold (Guerriero et al., 2018).

Recent advances in terpenoid biosynthesis have integrated multiple engineering strategies to enhance production efficiently. CRISPR-Combo systems could enable dynamic pathway control in plant metabolic engineering. Research has demonstrated that by simultaneously knocking out squalene synthase (SQS) and activating terpene synthase (TPS), metabolic flux can be redirected toward sesquiterpenes (Li et al., 2023). Organelle engineering could theoretically optimize plastid metabolic pathways through enzyme co-localization strategies similar to synthetic protein scaffolds used in microbial systems (Noushahi et al., 2022). Such approaches may reduce metabolic intermediate diffusion in the MEP pathway and potentially enhance IPP flux, though this remains experimentally unvalidated in plastids (Zhao et al., 2019). Additionally, in the current frontier of terpenoid research, machine learning approaches have significantly enhanced the functional prediction capacity of terpene synthases. Recent studies integrating sequence diversity analysis with computational chemistry modeling have achieved an average prediction accuracy of 89% for terpene synthase substrate specificity (Samusevich et al., 2024). These advances open new avenues for natural product derivatization, including Aconitum diterpenoids. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the introduction of an isopentenol utilization pathway (IUP) optimizes IPP/DMAPP supply. Combined with metabolic engineering and process optimization, this strategy markedly enhances terpenoid production yields (Yaoyao Zhang et al., 2022). Collectively, these strategies exemplify the power of modern biotechnological approaches in improving terpenoid biosynthesis.

2.4. Emerging Insights and Challenges

Single-cell omics has substantially enhanced spatial resolution in plant biology. This is exemplified by scRNA-seq in Zea mays mesophyll cells, which identified 53 cell-type-specific transcription factors regulating cell cycle dynamics during differentiation (Tao et al., 2022). In Cinnamomum camphora, scRNA-seq studies have revealed dynamic transcriptional networks governing terpenoid biosynthesis, including 24 functionally annotated terpene synthase genesand 2,863 differentially expressed genes between borneol- and camphor-type chemotypes (Chen et al., 2018). While microbial and mammalian systems utilize identified IPP transporters, plant systems lack analogous resolved mechanisms. [Insert revised statement here]. Consequently, elucidating whether IPP traverses the chloroplast membrane via dedicated transporters or physicochemical gradients represents a fundamental priority for plant metabolic engineering (Flügge and Gao, 2005). In cytochrome P450 engineering, rational redesign of substrate pockets remains constrained by dynamic structural uncertainties (Han et al., 2021). Current progress increasingly stems from semi-rational strategies that integrate computational prescreening, reducing mutant screening burdens by >95% compared to traditional approaches (Wijma et al.). Additionally, the interplay between metabolic pathways and environmental stressors dynamically redistributes precursor allocation in planta, as quantified through isotopic flux studies. In Arabidopsis thaliana, phosphate stress reduces oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (oxPPP) flux by 38% while elevating anaplerotic flux through phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC) and malic enzyme, concurrently disrupting energy and nitrogen assimilation (Masakapalli, 2011; Masakapalli et al., 2014). These responses diverge tissue-specifically. shoots prioritize photosynthetic Pi remobilization, whereas roots accumulate organic acids for soil Pi chelation. Systematic multi-omics integration is thus essential to resolve this complexity, having successfully linked dynamic metabolomes with transcriptional regulators to decode systemic adaptation mechanisms.

3. Genomics and Multi-Omics: Unveiling the Blueprint and Targets

3.1. Genome Sequencing: Foundation for Gene Discovery

Advancements in genome sequencing have become foundational for discovering genes involved in terpenoid biosynthesis, with high-quality chromosome-level genomes playing a critical role. Recent studies employ long-read sequencing technologies, such as PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore, along with Hi-C chromatin mapping, to assemble the complex and repetitive genomes of medicinal plants with high contiguity (N50 > 10 Mb) (Dong et al., 2022; Du et al., 2022; Yingmin Zhang et al., 2023; Zhou et al., 2022). These methodologies facilitate the identification of key gene families, such as Terpene Synthase (TPS), Cytochrome P450 (CYP), and UDP-Glycosyltransferase (UGT). This is achieved through homology-based screening and conserved domain analysis. In A. annua, chromatin conformation analysis has revealed spatial interactions regulating the artemisinin biosynthetic cluster (Liao et al., 2023); synteny analysis remains the primary method for identifying evolutionarily conserved clusters across species (Kautsar et al., 2017). Comparative genomics further provides evolutionary insights by revealing expansion and contraction events within gene families, contributing to our understanding of terpenoid diversification (Tai et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2023; Zi et al., 2014).

3.2. Transcriptomics: Spatial-Temporal Dynamics of Terpenoid Pathways

Bulk RNA sequencing is pivotal for mapping tissue-specific expression patterns of core terpenoid biosynthetic genes. Notably, this includes TPS and (CYPs) in specialized structures such as glandular trichomes and roots. This approach also robustly captures inducible expression dynamics, particularly in response to jasmonate signaling, as evidenced by the rapid upregulation of sesquiterpene synthases in tomato trichomes and defense-associated CYPs in N. attenuate (Liu et al., 2011; Spyropoulou et al., 2014). Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) identifies transcriptional modules strongly correlated with terpenoid accumulation and nominates candidate regulatory transcription factors for experimental validation of cis-element interactions (Ren et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2024). The advent of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics holds transformative potential for mapping gene expression to distinct cell types and anatomical compartments. A 2022 study, through scRNA-seq, identified terpenoid biosynthesis gene enrichment in epidermal cell subpopulations (Booth et al., 2020). Spatial transcriptomics enables cellular-resolution mapping in model plants, as demonstrated by MERFISH visualization of auxin transporters in Arabidopsis leaf vasculature (Chen et al., 2015; Xia et al., 2021).

3.3. Metabolomics: Bridging Genotype to Chemotype

High-resolution mass spectrometry techniques, particularly LC-MS/MS and GC-MS, are integral to the untargeted profiling of complex terpenoids across diverse plant taxa. These methods enable robust correlation of metabolite abundance with gene expression through integration with Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA), as demonstrated in Gynostemma pentaphyllum and Ferula assafoetida (Amini et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2024). While ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) provides supplementary separation capabilities for isomer resolution, its application remains limited to metabolite identification rather than gene-metabolite correlation studies (Wang et al., 2024). The established HRMS-WGCNA framework supports metabolic engineering evaluations by quantifying titer improvements. It measures sesquiterpene lactone increases in engineered A. annua; it also quantifies byproduct reduction in engineered systems (Daliri et al., 2020; Oh et al., 2023). In Centella asiatica, recent machine learning advances have optimized quantification of known saponins like asiaticoside, though novel saponin discoveries relied on classical NMR/HRMS approache (Wan et al., 2024). Crucially, UDP-glycosyltransferase linkages to saponin biosynthesis continue to be elucidated through biochemical characterization (Wan et al., 2024).

3.4. Proteomics and Post-Translational Regulation

Emerging quantitative proteomics techniques, such as Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) and Sequential Window Acquisition of All Theoretical Mass Spectra (SWATH-MS), hold significant promise for comprehensively profiling the abundance of enzymes involved in terpenoid biosynthesis, although their standardized application specifically for terpenoid pathway enzymes requires further development (Gillet et al., 2012; Peterson et al., 2012). Complementing abundance measurements, phosphoproteomics provides critical insights into kinase-mediated regulatory mechanisms. A prime and well-validated example is the inhibitory phosphorylation of HMG-CoA reductase (HMGR), the rate-limiting enzyme in the mevalonate (MVA) pathway, at Serine 577 in Arabidopsis thaliana, which directly reduces its activity (Domon and Aebersold, 2010; Lange et al., 2008). Targeted proteomic approaches, such as Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM), have successfully quantified dynamic changes in terpenoid biosynthetic enzyme abundance, like terpene synthases (TPS) and DXS isoforms, under elicitation (Reiter et al., 2011). Phosphorylation-mediated regulation of cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes is a recognized mechanism in biological systems (Faktor et al., 2014). Phosphorylation of human CYP450c17 by p38α kinase enhances its 17,20-lyase activity during androgen biosynthesis (Tee and Miller, 2013). These findings underscore the importance of rigorously investigating post-translational modifications, particularly phosphorylation, in regulating terpenoid biosynthesis and highlight validated and potential targets for metabolic engineering.

3.5. Epigenomics: Chromatin-Level Control

Chromatin-level regulation, encompassing DNA methylation, histone modifications, and 3D conformation, theoretically influences terpenoid gene expression, though direct mechanistic evidence remains limited. Empirical studies confirm DNA methylation actively modulates terpenoid pathways. In Rehmannia glutinosa, the demethylating agent 5-azaC upregulated iridoid glycoside genes, increasing monoterpene accumulation by 2.3-fold (Ma et al., 2022). In Eleutherococcus senticosus, hypermethylation suppressed saponin biosynthetic genes, reducing triterpenoid content by 60% (Ma et al., 2022). Techniques like ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq could advance understanding of histone modifications in terpenoid-producing tissues, particularly given validated histone marks in other specialized metabolic pathways. These findings highlight significant knowledge gaps in epigenomic regulation of terpenoid biosynthesis, underscoring the need for targeted studies to unlock epigenetic engineering potential.

3.6. Integrative Multi-Omics: From Description to Prediction

Integrating genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics through systems biology approaches is essential for advancing predictive engineering in plant biotechnology. By constructing gene regulatory networks (GRNs) and genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), researchers can identify master regulators, such as MYB and bHLH transcription factors, alongside rate-limiting enzymes critical for optimizing metabolic pathways. Machine learning techniques enable robust analysis of multi-omics datasets, facilitating the prediction of gene functions and identification of optimal engineering targets. Random Forest regression has been successfully applied to integrate transcriptomic and metabolomic data in potato, predicting phenotypic traits linked to tuber development (Bai et al., 2024). Similarly, MYB and bHLH transcription factors, known to regulate phenylpropanoid and flavonoid biosynthesis via MBW complexes, have been used to boost anthocyanin production in model plants (Van den Broeck et al., 2020). These predictive frameworks underpin synthetic biology design, enabling the creation of minimal gene circuits for heterologous production in systems like yeast or N. benthamiana, as demonstrated in the reconstruction of benzylisoquinoline alkaloid pathways (Dahal et al., 2020). While transformative potential is evident, current achievements focus on iterative refinement of models using 2-4 omics layers, with seminal work in elicitor-induced paclitaxel enhancement paving the way for future multi-target engineering (Zhu et al., 2023).

4. Metabolic Engineering Strategies: From Targets to Phenotypes

4.1. Rate-Limiting Enzyme Overexpression and Pathway Enhancement

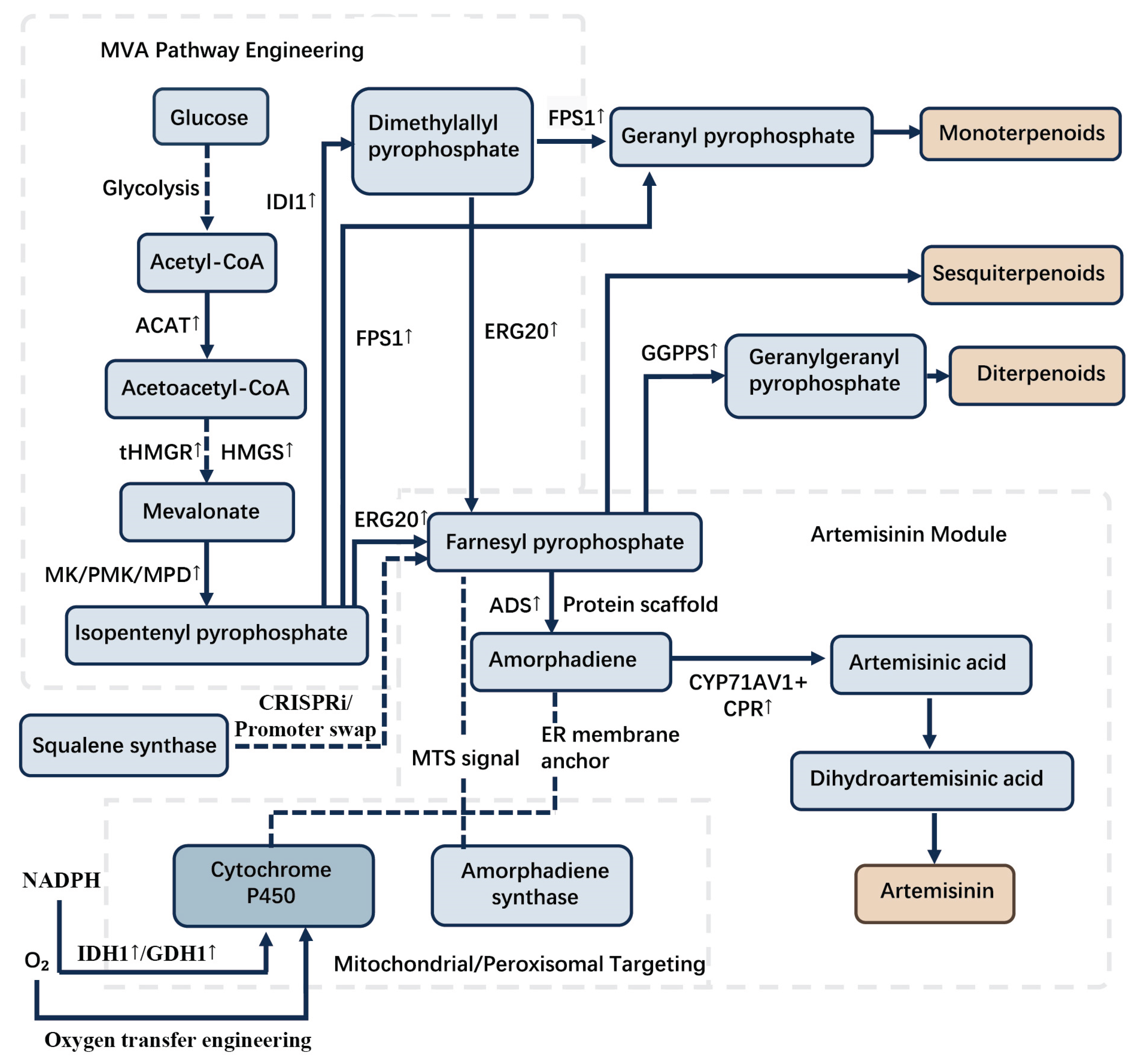

Overexpression of key enzymes in the MVA/MEP pathway is critical for enhancing artemisinin production in A. annua. Multi-gene co-expression strategies have demonstrated significant success, exemplified by the simultaneous overexpression of farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPS), cytochrome P450 CYP71AV1, and its redox partner CPR, which collectively increased artemisinin yield by 3.6-fold in transgenic lines (Scossa et al., 2018). Similarly, co-expression of amorpha-4,11-diene synthase (ADS), CYP71AV1, CPR, and aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) achieved a 3.4-fold enhancement by optimizing flux through the late biosynthetic steps (Shi et al., 2017). Enzyme fusion approaches also show promise, as evidenced by FPS-ADS fusion constructs that improve substrate channeling and increase amorpha-4,11-diene (a key precursor) production by 2- to 3-fold (Guerriero et al., 2018). While precursor compartmentalization remains a challenge, co-overexpression of native cytosolic HMGR and plastidial DXR has been employed to augment the overall precursor pool, though plastid-targeting of HMGR lacks experimental validation (Hassani et al., 2023).

4.2. Precise Suppression of Competing Pathways

Precise suppression of competing pathways represents a promising strategy for redirecting metabolic flux toward valuable plant metabolites, though specific applications require rigorous validation. For flux redirection, antisense suppression of squalene synthase (SQS) in tobacco has demonstrated efficacy, reducing sterol biosynthesis while increasing gibberellin GA3 production by diverting farnesyl pyrophosphate toward diterpenoid pathways (Mitra et al., 2023). Similarly, RNAi-mediated knockdown of SmHPPD in Salvia miltiorrhiza successfully enhanced rosmarinic acid and salvianolic acid B yields by reducing substrate competition (Hao et al., 2012). Although CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) holds theoretical potential for such applications, its implementation for plant pathway suppression remains experimentally unverified. These cases highlight that effective flux redirection requires method-specific verification, with RNAi and antisense approaches currently providing the most documented successes for competitive pathway suppression in plant systems (Bhuyan et al., 2023).

4.3. Transcriptional Factor (TF) Hierarchical Regulation

Transcriptional factor hierarchical regulation optimizes metabolite biosynthesis through coordinated overexpression of positive regulators and suppression of repressors. In A. annua, overexpression of the AaMYB2 transcription factor co-activates key artemisinin pathway genes, enhancing biosynthesis (Shen et al., 2018). Similarly, AaTGA6 (bZIP TF) overexpression elevates expression of the same gene set, confirming this co-activation strategy (Shen et al., 2019). For repressor suppression, RNAi-mediated silencing of ZCT-family transcription factors in Catharanthus roseus has been explored to alleviate repression of terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis, though functional redundancy complicates outcomes (Traverse et al., 2024). To mitigate pleiotropic effects from constitutive expression, tissue-specific promoters can be used. The Agrobacterium rhizogenes-derived RoIC promoter, which drives phloem-specific expression, can spatially confine TF activity, as validated in transgenic potato systems (Graham et al., 1997).

4.4. Heterologous Pathway Reconstruction and Enzyme Engineering

Heterologous pathway reconstruction and enzyme engineering enable sustainable production of high-value metabolites in optimized host systems (

Figure 2). In

N. tabacum, the taxadiene synthase (TS) gene from

Taxus brevifolia was expressed in chloroplasts using a chloroplast transit peptide. This approach achieved taxadiene yields of 87.8 µg/g dry weight by utilizing plastidial GGPP pools for precursor supply (Fu et al., 2021). For complex triterpenoid pathways,

Saccharomyces cerevisiae has proven effective. Co-expression of ginseng dammarenediol-II synthase (PgDDS) and cytochrome P450 CYP716A47 successfully synthesized protopanaxadiol (PPD), the core ginsenoside backbone (Zhang et al., 2019). Further demonstrating cross-kingdom potential, tobacco co-expressing PgDDS, CYP716A47, and CYP716A53v2 produced protopanaxatriol (PPT), confirming functional reconstitution of multi-step oxidation cascades (Gwak et al., 2019). These cases highlight the critical importance of precise enzyme selection, compartmentalization, and host compatibility for successful pathway transplantation.

4.5. Directed Subcellular Metabolic Channeling

Strategic subcellular compartmentalization enhances terpenoid production by colocalizing enzymes with their substrates, though reported improvements require precise verification. In N. benthamiana, plastid-targeted expression of monoterpene synthases increased yields by 1.2-fold by leveraging concentrated plastidial IPP/DMAPP pools (Kanagarajan et al., 2012). While mitochondrial targeting of sesquiterpene synthases boosted valencene production by 2.8-fold (Kanagarajan et al., 2012), the specific mechanisms and extent of these improvements warrant further validation. For specialized metabolite transport, the ATP-binding cassette transporter AaABCG40 demonstrably enhances artemisinin accumulation in A. annua glandular trichomes (Fu et al., 2020). These approaches, including DXS/GGPPS co-expression with plastid-targeted diterpene synthases yielding a 10-fold taxadiene increase (Kanagarajan et al., 2012), demonstrate how validated subcellular targeting optimizes metabolic flux.

4.6. Cofactor Balancing and Dynamic Regulation

Strategic cofactor management and dynamic pathway control are critical for optimizing terpenoid biosynthesis. In A. annua, NaCl-induced activation of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) elevated NADPH regeneration under oxidative stress, correlating with a 79.3% increase in artemisinin production (Wang et al., 2017). For dynamic control, methyl jasmonate (MeJA)-responsive promoters drive coordinated tanshinone biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza, with SmMEC gene expression increasing >5-fold post-elicitation (Hao et al., 2020). This endogenous regulatory system enables synchronized upregulation of pathway genes (SmHMGR, SmDXR, SmGGPPS), while RNAi knockdown of JAZ repressors elevates tanshinone yields 2-3-fold by de-repressing MYC2 transcription factors (Szymczyk et al., 2022). Complementary approaches like engineered NADH-dependent HMGR variants in microbial systems further alleviate NADPH bottlenecks without compromising redox balance (Wang et al., 2013).

4.7. Synthetic Biology Tool Advancements

Recent synthetic biology advances have significantly enhanced medicinal plant metabolic engineering, particularly through CRISPR-based multiplex genome editing. Validated CRISPR-Cas9 systems enable efficient simultaneous knockout of multiple gene targets in hairy root cultures, a critical functional genomics platform for recalcitrant species. Research has shown that in Eucalyptus grandis, dual sgRNA constructs achieved 75% editing efficiency for concurrent EgrCCR1 and EgrIAA9A mutations (Zhang et al., 2020). Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that soybean codon-optimized Cas9 systems facilitate precise multiplex editing of homeologous genes. For metabolic pathway control, engineered promoters now enable tissue-targeted and inducible terpenoid biosynthesis, mitigating growth defects from constitutive overexpression (Das et al., 2024). Delivery systems have also progressed: optimized Agrobacterium strains coupled with surfactants achieved 70.9% transformation efficiency, and hairy root cultures consistently overcome regeneration bottlenecks in slow-growing species like Panax ginseng, yielding 2-3 fold higher metabolite titers. Nevertheless, persistent challenges include genotype-dependent regeneration and the need to validate emerging tools like CRISPR-Combo systems and nanoparticle co-delivery in medicinal species.

5. Biotechnological Applications: From Laboratory to Potential Industrialization

5.1. High-Yielding Medicinal Plant/Cell Line Cultivation

Metabolic engineering has significantly advanced high-yielding terpenoid production in medicinal plants, with several experimentally validated breakthroughs. In A. annua, stacked overexpression of ADS, CYP71AV1, ALDH1, and POR genes achieved a 3.4-fold artemisinin increase, surpassing early single-gene approaches (Y. Li et al., 2024b; Scossa et al., 2018). For paclitaxel, optimized plant cell suspension cultures remain the most productive system, yielding industrially validated titers of 900 mg/L, while microbial platforms have thus far succeeded only in precursor synthesis (Lu et al., 2016). Equally significant, co-expression of SmCPS1 and SmKSL1 in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots robustly enhances tanshinone IIA accumulation, though quantitative genetic stability metrics across subcultures require further documentation(Kowalczyk et al., 2020). Recent CRISPR advances include modulating trichome density in A. annua by editing the SGS3 gene, a validated strategy to indirectly elevate artemisinin levels (Wani et al., 2021).

5.2. Production of Rare or Complex Terpenoids

Plant chassis systems offer distinct advantages for synthesizing highly oxidized terpenoids by leveraging native cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes and compartmentalization. A validated example is the production of artemisinic acid in N. benthamiana through heterologous expression of amorphadiene synthase (ADS) and CYP71AV1, demonstrating the system’s capacity for complex oxidation reactions (Reed and Osbourn, 2018). For triterpenoid saponins, Panax ginseng engineered with CRISPR-mediated suppression of CYP716A53v2 coupled with phenylalanine ammonialyase (PAL) overexpression achieved ginsenoside Rg3 at 7.0 mg/g dry weight. This represents a 21-fold increase over the wild type, marking the highest plant-derived yield documented (Li et al., 2022). Microbial systems remain superior for certain glycosylation steps, as evidenced by yeast platforms expressing PgUGT74AE2 and PgUGT94Q2 yielding > 250 mg/L Rg3 (Jung et al., 2014). These cases underscore plant chassis potential while highlighting context-specific limitations for rare terpenoid biosynthesis.

5.3. Biosynthesis of Novel Terpenoid Derivatives

Combinatorial biosynthesis has significantly expanded the “non-natural natural product” repertoire by enabling systematic diversification of terpenoid scaffolds. Engineered CYP76-family libraries (CYP76AH/CYP76AK) in yeast have oxidized abietadiene precursors to produce 14 abietane diterpenes (Bathe et al., 2019). Among these, 8 are previously unreported. This demonstrates unparalleled scaffold diversity. Among these, novel compounds like Liquidambarines A-C exhibit potent anti-inflammatory activity by suppressing NF-κB-mediated iNOS and COX-2 expression in macrophages (Reed and Osbourn, 2018). Concurrently, modular assembly of terpene synthases and P450s in yeast enables artificial triterpene biosynthesis, exemplified by functional partnerships such as β-amyrin synthase with CYP716Y1 to produce C-16α-hydroxylated derivatives (Moses et al., 2014). These approaches highlight the capacity to engineer structurally complex terpenoids with tailored bioactivities.

5.4. Enhanced Plant Stress Resistance

Terpenoid metabolic engineering offers promising strategies to enhance plant stress resilience. Overexpression of the tps10 terpene synthase in Arabidopsis thaliana significantly repelled aphids by emitting linalool and other volatiles, as demonstrated in controlled dual-choice assays with robust statistical support (Clough and Bent, 1998). Similarly, in Salvia miltiorrhiza, overexpression of specific SmJAZ isoforms (SmJAZ1/2/5/6) activated jasmonate signaling and elevated tanshinone accumulation by upregulating diterpenoid biosynthetic genes (SmGGPPS, SmKSL) (Ma et al., 2012). These examples underscore both the potential and limitations of terpenoid engineering, emphasizing the need for isoform-specific characterization and rigorous statistical reporting.

5.5. Plant Cell/Tissue Culture & Scale-Up Challenges

Suspension cell culture integrated with bioreactor technology offers a viable pathway for the industrial production of high-value compounds like paclitaxel and ginsenosides. For paclitaxel, validated bioreactor yields reach 25.63 mg/L in 20 L systems (Li et al., 2009). However, scale-up faces significant challenges including genetic instability in cell lines, which threatens long-term yield consistency. Notably, commercial production has been successfully achieved by companies like Phyton Biotech and Samyang Genex using plant cell culture (Motolinía-Alcántara et al., 2021). For ginsenosides Rg3, engineered yeast systems demonstrate high potential with yields of 254.07 mg/L in shake flasks, though documented production in bioreactors exceeding 100 L scale remains unavailable (Wang et al., 2012). Key scale-up barriers include shear sensitivity in plant cells and the need for dynamic nutrient control (Kochan et al.). To ensure competitiveness, production costs must target < $500/kg. Future advancements may leverage AI-driven bioreactor systems with real-time metabolomic monitoring to optimize processes, though this approach requires experimental validation.

5.6. Plant Systems as Green Cell Factories

Compared to microbial fermentation, plant systems offer inherent advantages for complex terpenoid modifications due to complete endogenous enzyme systems, exemplified by intricate P450 oxidation networks enabling terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus (Le Cong et al., 2013). Subcellular compartmentalization further prevents toxic intermediate accumulation, as demonstrated by artemisinin storage in glandular trichome vesicles (Jinek et al., 2012). Additionally, native plant UGTs provide regioselective glycosylation critical for bioactivity (Shan et al., 2013). However, heterologous expression of identical UGT isoforms in yeast reduces catalytic efficiency due to lower expression, insufficient UDP-sugar donors, and poor kinetics (Li et al., 2013). As metabolic engineering transitions toward industrial scaling, CRISPR editing shows promise for targeted pathway optimization, though long-term genetic stability in suspension cultures lacks validation (Feng et al., 2018). Similarly, while AI-sensor fusion emerges for bioreactor control (Meng et al., 2020), no industrial-scale platforms exist for plant terpenoid production (Tang and Fu, 2018).

6. Current Challenges and Bottlenecks

6.1. Complex Pathways and Incompletely Understood Regulation

Terpenoid biosynthetic pathways are often highly branched, involving multi-step enzymatic cascades with promiscuous intermediates and extensive crosstalk with primary metabolism (Rizvi et al., 2016). Regulatory networks controlling flux remain largely unmapped in non-model medicinal species, as exemplified by the poorly understood transcriptional regulation of terpenoid indole alkaloids in Catharanthus roseus (Rizvi et al., 2016). Advanced techniques are revealing spatial regulatory complexity: In A. annua, transcriptomic analysis of laser-microdissected glandular trichome cell layers revealed cell-type-specific expression divergence in artemisinin pathway genes (She et al., 2019). Similarly, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of CYP716A53v2 in Panax ginseng cell cultures successfully ablated specific ginsenoside production, demonstrating precise metabolic pathway dissection (Mao et al., 2020).

6.2. Limitations in Genetic Transformation and Regeneration

The genetic modification of many high-value medicinal plants is hampered by low transformation efficiency and challenging regeneration protocols. Species like Taxus and Catharanthus often require lengthy de novo regeneration processes exceeding one year, contrasting sharply with model systems like N. benthamiana (Hiei et al., 1994). Recent advances offer targeted solutions: in Camptotheca acuminata, optimized Agrobacterium-mediated transformation achieves 6% efficiency through refined co-cultivation parameters (Wang and Zu, 2007); hairy root CRISPR systems in Salvia miltiorrhiza enable efficient editing, with reported efficiencies reaching 71.07% (Silva et al., 2022); nodal section transformation in Stevia rebaudiana yields 40.48% efficiency (Yadav et al., 2011). While morphogenic transcription factors how transformative potential in recalcitrant crops like maize (Lowe et al., 2016), these collective advances provide validated pathways for manipulating medicinal species.

6.3. Metabolic Imbalance, Growth Penalties, and Toxicity

Engineered hyperaccumulation of terpenoids frequently incurs metabolic trade-offs, primarily through resource competition for central metabolites such as carbon skeletons, ATP, and NADPH, which directly impairs plant growth. This is empirically demonstrated in transgenic Arabidopsis lines expressing sesquiterpene synthases, where precursor depletion correlates with significant growth retardation (Aharoni et al., 2003). While chloroplast-targeted sesquiterpene production occurs in N. species (Chen et al., 2003), no direct evidence confirms that sesquiterpene overproduction disrupts chloroplast integrity via ROS bursts in engineered N. benthamiana. Instead, ROS generation in chloroplasts is a documented stress response under pathological or metabolic perturbations (Obata and Fernie, 2012). Reactive intermediates like epoxides theoretically generated during taxadiene hydroxylation by cytochrome P450s may pose toxicity risks if accumulation occurs. To mitigate potential instability, spatial sequestration or co-expression of detoxifying enzymes represents a hypothesized safeguard (Aharoni et al., 2006), though in planta efficacy remains unvalidated.

6.4. Compartmentalization and Transport Barriers

Terpenoid biosynthesis involves multiple organelles, creating inherent challenges in trafficking compounds across membranes. Engineering efficiency is frequently constrained by uncharacterized transporters; however, recent discoveries are resolving these barriers. In Catharanthus roseus, CrNPF2.9 was identified as responsible for exporting the monoterpene indole alkaloid (MIA) intermediate strictosidine from vacuoles to the cytosol (Payne et al., 2017). ABC transporters in C. roseus instead facilitate later-stage MIA export across the plasma membrane (Yu and De Luca, 2013). Additionally, breakthroughs in chloroplast compartmentalization in N. benthamiana demonstrate transformative potential (Payne et al., 2017). Targeting taxadiene synthase to chloroplasts resulted in the production of taxadiene at 56.6 μg/g fresh weight. This represents an increase of thousands-fold over the baseline level. These advances underscore how elucidating transport mechanisms and optimizing subcellular targeting can overcome critical bottlenecks in terpenoid engineering.

6.5. Suboptimal Enzyme Properties

Key terpenoid-modifying enzymes, including cytochrome P450s (CYPs) and UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGTs), frequently exhibit suboptimal properties such as low catalytic efficiency, instability, and substrate promiscuity, constraining terpenoid pathway efficiency. Recent advances in enzyme engineering, particularly directed evolution and machine learning (ML), have addressed these limitations with demonstrable success. ML-guided engineering of UGT73P12 via activity-based sequence conservation analysis (ASCA) yielded mutants with a 200-fold increase in catalytic efficiency for terpenoid glycosylation (Jackson, 2009). In Salvia miltiorrhiza, co-expression of upstream pathway genes SmGGPPS and SmHMGR, achieved a validated 5.7-fold increase in tanshinone yield (Wan et al., 2024). These engineering breakthroughs underscore the potential of computational and combinatorial strategies to overcome enzymatic bottlenecks in terpenoid biosynthesis.

6.6. Lack of Universal Chassis Plants

While N. benthamiana is valuable for transient expression, its utility for perennial terpenoid production is constrained by metabolic limitations and carbon competition, necessitating specialized chassis plants. Genetic engineering advances offer promising alternatives: CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of squalene synthase (SQS) in A. annua achieved 84.6% mutagenesis efficiency, redirecting flux toward artemisinin precursors and elevating yields up to 3-fold (Y. Li et al., 2024b). Additionally, hairy root cultures in Ophiorrhiza pumila enable stable camptothecin production at 0.1-0.3% dry weight, though bioreactor scalability remains unvalidated at pilot scale (Al-Khayri et al., 2022). These strategies represent progress toward tailored plant chassis but require further optimization for sustainable, scalable terpenoid biosynthesis.

6.7. Scale-Up Challenges and Economic Viability

Transitioning terpenoid production from laboratory to commercial scale faces significant biological and engineering hurdles. Field cultivation is inherently susceptible to environmental variability, which critically impacts terpenoid profile consistency. This is exemplified in Cannabis sativa, where controlled studies demonstrate that factors like drought timing or UV light exposure cause substantial, chemotype-dependent fluctuations in yield and composition (Patil et al., 2012). Conversely, in vitro production using plant cell cultures encounters distinct barriers: high operational costs driven by extensive medium requirements, genetic instability leading to productivity loss over time, and severe sensitivity to bioreactor shear stress that damages fragile cells and constrains reactor design, as documented in Taxus chinensis cultures (Xu and Zhang, 2014). However, advanced cultivation technologies show promise in mitigating these challenges. Research has shown that perfusion bioreactors have significantly enhanced paclitaxel production in Taxus cultures, enabling continuous specific production rates of ~0.3 mg/g DCW/day for extended periods by alleviating product inhibition (Sood, 2020). Furthermore, emerging biological strategies like fungal co-culture have yielded dramatic improvements, such as a 38-fold increase in paclitaxel titer when Taxus cells were co-cultured with an endophytic fungus, demonstrating the potential for synergistic elicitation to overcome productivity limitations and improve economic viability (Rinaldi et al., 2022).

6.8. Regulatory and Societal Hurdles

Gene-edited medicinal plants face a fragmented regulatory landscape characterized by divergent regional approaches. Process-centric jurisdictions like the European Union impose stringent requirements under genetically modified organism (GMO) legislation, where the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) acknowledges that existing guidelines are only “partially applicable” to Site-Directed Nuclease-1 (SDN-1) plants, mandating extensive trait-specific safety dossiers and documentation of editing precision (Yıldırım et al., 2023). In regions like the United States and Japan, product-focused frameworks take advantage of the non-transgenic nature of SDN-1 edits (Yıldırım et al., 2023). The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) confirms that SDN-1 edits pose no additional safety concerns compared to conventional breeding. This allows for regulatory exemptions for edits that do not involve foreign DNA. Such exemptions apply if the traits introduced could also occur naturally. These facilitated the 2021 commercialization of CRISPR-edited Sicilian Rouge high-GABA tomatoes. These tomatoes are the world’s first genome-edited food product. In 2023, there was a rapid approval of waxy corn. This approval was under the oversight of MAFF (Hamdan et al., 2022). These successes highlight how societal acceptance accelerates commercialization in product-focused systems. This is driven by transparent labeling and consumer education, which help overcome the persistent “pharma-crop” stigma in medicinal applications.

7. Prospects and Frontier Directions

7.1. Deep Integration of Multi-Omics and Systems Biology for Predictive Modeling

The integration of multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, epigenomics) with Genome-scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) and machine learning enables unprecedented precision in predicting metabolic flux bottlenecks, identifying regulatory targets, and optimizing engineering strategies (Pinu et al., 2019). Single-cell multi-omics resolves cell-type-specific metabolic networks, as demonstrated in medicinal plants: scRNA-seq in Gossypium glandular trichomes identified transcriptional hierarchies regulating gossypol biosynthesis, enabling CRISPR-mediated activation of ERF12 that increased yields by 140% (Hong et al., 2016). Deep learning classification models achieve high accuracy in pathway prediction. Spec2Class attains 73% top-1 accuracy for secondary metabolite classification using chemical structures. Additionally, GTC sets benchmarks for multi-label pathway inference (Chen and Wu, 2013). However, quantitative regression models for predicting metabolite concentrations remain underdeveloped due to sparse temporal data and lack of standardized benchmarks (Chen and Wu, 2013).

7.2. Innovation in Gene Editing Technologies

CRISPR-based tools, including base editing (BE), prime editing (PE), multiplex editing, and transient RNP delivery, are expanding in plant biotechnology. These advancements enhance precision and safety in the field. BE enables C-to-T/A-to-G substitutions without double-strand breaks (DSBs), achieving 2.7-13.3% efficiency in rice (Jiang et al., 2020). PE further allows all 12 base substitutions and small indels without donor templates, with regeneration frequencies up to 21.8% in rice/wheat (Abdullah et al., 2020). These technologies circumvent low homologous recombination efficiency in recalcitrant species. For complex pathway engineering, multiplex editing concurrently targets rate-limiting terpenoid genes in N. benthamiana, redirecting metabolic flux via knockout of competing pathways (Baloglu et al., 2022). Critically, DNA-free RNP delivery eliminates foreign DNA integration, aligning with regulatory compliance. Transient RNP-mediated knockout of CYP71D genes in N. benthamiana enhances sesquiterpenoid yields (Y. Zhang et al., 2022), while USDA approvals for CRISPR-edited crops underscore commercial viability (Hsu et al., 2021). However, heritable edits in metabolic pathways remain challenging, with somatic edits dominating T1 generations and stabilization requiring T3 lineages (Y. Zhang et al., 2022).

7.3. Synthetic Biology and Modular Design

Synthetic biology applies engineering principles such as standardization, modularity, and orthogonality to deconstruct complex terpenoid biosynthetic pathways into interoperable genetic modules. This approach enhances predictability and scalability. While the foundational BioBrick standard inspired this approach, its direct implementation in terpenoid pathways remains limited. Instead, BioBrick-inspired modular design enables pathway segmentation and optimization, exemplified by the partitioning of the taxadiene pathway in E. coli into two independently tuned modules, achieving a 15,000-fold titer improvement (~1 g/L) (Ajikumar et al., 2010). Orthogonal systems further ensure stable expression by decoupling engineered pathways from host regulation, as demonstrated by orthogonal T7 polymerases and riboswitches that boosted limonene yields in yeast and monoterpene titers in E. coli by 2-fold and 3‒11-fold, respectively (Zhang and Hong, 2020). Dynamic regulatory circuits integrate metabolite-sensing feedback such as optogenetic controls or quorum-sensing systems to auto-adjust gene expression in response to cellular states. This balance of precursor flux and toxicity results in a 40% increase in amorphadiene production in yeast (Zhang and Hong, 2020). These strategies converge in plug-and-play platforms like engineered Yarrowia lipolytica strains, which employ standardized modules to achieve 100-fold higher limonene and 8.4-fold elevated valencene yields (Madhavan et al., 2019). Collectively, modular design, orthogonal components, and intelligent regulation transform terpenoid biosynthesis from artisanal tinkering toward predictable biomanufacturing; though broader standardization remains a future goal (Zhang and Hong, 2020).

7.4. Enzyme Engineering and Directed Evolution

Enzyme engineering and directed evolution are pivotal for optimizing the catalytic efficiency, specificity, and stability of terpenoid biosynthetic enzymes. This is particularly important for Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYPs), Terpene Synthases (TPSs), and UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGTs). Rational design leverages cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to resolve dynamic conformations, integrated with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for precise residue targeting, as demonstrated in MD-guided thermostabilization strategies (Kumar, 2010). Directed evolution accelerates enzyme optimization through high-throughput screening innovations, including microfluidics and fluorescence-based reporters for CYP activity (Kumar, 2010). These approaches enable: (1) Substrate scope expansion: Directed evolution of P450BM3 accessing non-native terpenoids (Otey et al., 2006); (2) Stability enhancement: Surface-charge optimization in plant P450s improving heterologous expression in tobacco for taxol biosynthesis (Z. Zhang et al., 2023); (3) Regioselectivity control: MD-simulated residue swaps in UGTs increasing glycosylation efficiency by 2.5-fold (Kumar, 2010). Recent advances elucidate electric-field effects in P450 dynamics (He et al., 2024). Collectively, these engineered enzymes facilitate novel terpenoid synthesis and yield improvements while addressing critical challenges like plant P450 solubility and host-environment tolerance.

7.5. Organelle Engineering

Chloroplasts and mitochondria provide specialized environments for engineering terpenoid biosynthesis, leveraging their metabolic compartmentalization and semi-autonomous genomes. Chloroplast engineering exploits high genome copy numbers (~10,000 per cell), prokaryotic-like expression systems, and endogenous terpenoid precursors (IPP/DMAPP) (Boynton et al., 1988). While chloroplast transformation enables high protein accumulation (Oey et al., 2009), quantified terpenoid yields remain unreported despite pathway engineering in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Jackson et al., 2021). Critically, transporter engineering for IPP/DMAPP movement is unresolved, with only bicarbonate transporters successfully engineered to date (Sakamoto et al., 2008). Mitochondrial engineering focuses on enhancing acetyl-CoA flux: in yeast, pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) overexpression boosted acetyl-CoA 3-fold, enabling compartmentalized terpenoid synthesis (Agapakis et al., 2011). This resulted in quantifiable improvements: a 3.7-fold increase in α-santalene titers compared to cytosolic expression, 427 mg/L of amorpha-4,11-diene achieved through mitochondrial-localized pathways, and a 6-fold increase in geraniol production (Agapakis et al., 2011).

7.6. Development of Efficient Universal Chassis

Efficient plant chassis development prioritizes species with rapid growth kinetics, high biomass yield, well-characterized genomes, and amenability to genetic transformation. Specialized chassis leverage traditional medicinal plants: Salvia miltiorrhiza has been engineered using CRISPR-mediated knockout of SmCPS1 to enhance tanshinone yields by eliminating competing terpenoid pathways, achieving 2.7 mg/g DW in hairy root systems (Karkute et al., 2017). Perilla frutescens has also seen success with multiplex CRISPR editing, which suppressed FAD3, leading to a 60% increase in therapeutic perillaldehyde (Verma et al., 2023). Universal chassis focus on N. benthamiana, where transient expression exploits rapid biomass accumulation and efficient agroinfiltration (De Paola, 2024). Metabolic competition is actively minimized via VIGS-mediated PSY silencing, which doubled taxadiene titers to 48 μg/g DW; precursor pool expansion, elevating linalool 5-fold; and multigene stacking, producing artemisinin precursors at 130 mg/kg FW (Uetz et al., 2022). While genome minimization remains immature in plants, targeted pathway disruption and transient engineering establish N. benthamiana as the premier universal platform for therapeutic terpenoids. Future efforts require CRISPR-based pathway pruning and flux modeling to reduce endogenous competition systematically (L. Cong et al., 2013).

7.7. Cell-Free Synthetic Biology Systems

Cell-free synthetic biology utilizes plant cell extracts or reconstituted purified enzyme systems to synthesize complex terpenoids in a precisely controlled in vitro environment. This approach eliminates cellular limitations, such as cytotoxicity, transport barriers, and regulatory complexity, while enabling rapid pathway prototyping more than 100 times faster than in vivo processes, simplified product separation, and synthesis of cell-toxic compounds. Key advancements demonstrate the field’s maturity: orthogonal cofactor regeneration achieved a 65% yield for nepetalactol synthesis and reduced cofactor costs by more than 50 times through NAD(P)H recycling (Bat-Erdene et al., 2021). Engineered yeast systems produced 2.23 g/L limonene, while optimized platforms sustain greater than 100 mg/L h productivities at scales over 100 liters (Bat-Erdene et al., 2021). Enzyme stabilization via nanochannel confinement maintained activity over 1,740 reaction cycles, or 72 hours, addressing long-term instability (Bat-Erdene et al., 2021). However, challenges persist in cofactor economics, as NADPH regeneration costs exceed $1,000 per kilogram without recycling, pathway scalability, with a fivefold increase in shunt products at 10 milliliters versus 200 microliters scales, and enzyme sourcing, with fewer than 10% of plant terpenoid pathways reconstituted (Bat-Erdene et al., 2021). Despite these hurdles, the system excels at synthesizing pharmaceutically relevant terpenoids, such as triterpenoid betulinic acid at 18.7% productivity, positioning it for industrial adoption in high-value compound manufacturing (Bat-Erdene et al., 2021).

7.8. Integration of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are profoundly transforming metabolic engineering, particularly in terpenoid synthesis. In target prediction, deep learning models leverage databases like KEGG and MetaCyc to identify novel terpenoid biosynthesis genes and enzymatic regulators (He et al., 2023). For pathway design, AI-driven platforms such as BioNavI-NP and novoStoic enable de novo construction of mass-balanced biosynthetic routes; transfer learning strategies further enhance top-10 pathway prediction accuracy by ~20% by pretraining on chemical synthesis databases (Zheng et al., 2022). In enzyme engineering, AI significantly reduces the burdens associated with experimental screening. Tools like MutaCYP achieve 84.6% accuracy in classifying functional mutations for cytochrome P450s. Additionally, DeepP450 attains AUROC values ranging from 0.89 to 0.98 across major CYPs (Lawson et al., 2021). For bioprocess control, ML models optimize nutrients and hormones but peer-reviewed evidence directly linking ML-optimized light spectra to terpenoid yields is currently lacking (Bai et al., 2024).

7.9. Focus on Non-Model Medicinal Plants

Most plants with documented medicinal value are classified as “non-model species,” characterized by absent reference genomes and limited transformation protocols. However, advances in high-throughput sequencing now enable genomic characterization of these species: RNA-seq facilitates gene discovery in Gentiana rigescens and Phyllanthus amarus without reference genomes, while chromosome-scale assemblies reveal terpenoid biosynthetic diversity (Liu et al., 2017). Concurrently, transient CRISPR-Cas9 techniques partially overcome transformation barriers—demonstrated by PEG-mediated RNP delivery achieving 71.07% editing efficiency in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots to engineer tanshinone biosynthesis (Tian et al., 2025). Despite these advances, critical gaps persist in research. No peer-reviewed studies confirm transient CRISPR applications in rare traditional Chinese medicinal herbs, and novel terpenoid structures remain disconnected from genomic validations.

7.10. End-to-End Integration and Collaborative Innovation

Future success in medicinal plant terpenoid research demands comprehensive integration from fundamental discovery to commercialization. Basic research must elucidate the structure of the genome and metabolic networks. Studies have shown that transcription factors and epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA demethylation, can enhance the accumulation of tanshinones in Salvia miltiorrhiza (Danshen) (Jiang et al., 2016). Concurrently, metabolic engineering requires synergistic application of advanced tools: CRISPR editing of Taxus spp. for taxadiene overproduction and synthetic biology platforms reconstructing terpenoid pathways in yeast (Paddon et al., 2013; D. K. Ro et al., 2006). Downstream integration necessitates green extraction technologies and in situ modifications like engineered glycosyltransferases improving terpenoid solubility in microbial chassis (L. Li et al., 2024). Industrial translation crucially relies on academia-industry partnerships, as demonstrated by the scale-up of a semi-synthetic taxol precursor. These partnerships address scale-up economics and regulatory hurdles, ultimately accelerating patient access to plant-derived therapeutics (Mani et al., 2021).

8. Conclusions

This review highlights metabolic engineering as a critical strategy for the sustainable production of terpenoids. It emphasizes several key advancements in the field. One significant development is the use of genomic insights; research has shown that chromosome-level genomes and single-cell omics provide a detailed understanding of cell-type-specific regulations. Studies on glandular trichome-enriched artemisinin genes have demonstrated the potential for precise manipulation of biosynthetic pathways. Furthermore, engineering breakthroughs have played a substantial role in enhancing production efficiency. Research indicates that CRISPR-based tools, such as the knockout of SmABCG1, can improve tanshinone export. Additionally, enzyme optimizations achieved through machine learning have led to significant yield improvements, with studies showing a 200-fold increase in UGT73P12 efficiency. Harnessing these techniques has enabled the heterologous reconstruction of complex terpenoids in organisms like N. benthamiana and yeast. Noteworthy achievements include research demonstrating the production of protopanaxadiol at 254 mg/L.

In terms of industrial potential, bioreactor cultivation and microbial platforms are paving the way for scalable production. Studies have reported that paclitaxel has been successfully produced at a concentration of 25.63 mg/L in 20-liter systems. However, there are challenges such as genetic instability and regulatory issues that require addressing; policies surrounding SDN-1 plants remain obstacles to be resolved. Looking to the future, the integration of AI-driven metabolic modeling, cell-free production systems, and photoautotrophic chassis is expected to bridge the gap between laboratory-scale innovations and commercial-scale applications. Achieving the full potential of plant-based “green factories” for producing high-value terpenoids requires collaborative efforts spanning fundamental research, synthetic biology, and industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.G. and X.G.; Methodology, C.G. and S.X.; Investigation, C.G. and S.X. (literature survey, data extraction); Resources, C.G. and S.X. (bibliographic databases); Data Curation, C.G.; Writing—Original Draft, C.G.; Writing—Review & Editing, X.G. and S.X.; Visualization, C.G. (figures/tables); Supervision, X.G.; Project Administration, X.G.; Funding Acquisition, X.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Guangxi Science and Technology Base and Talent Special Project (Grant No. Guike AD22080016), the Guangxi Qihuang Scholars Training Program (Grant No. GXQH202402).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Full Name |

| ABC |

ATP-Binding Cassette |

| ADS |

Amorpha-4,11-Diene Synthase |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ALDH1 |

Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1 |

| ATAC-seq |

Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with high-throughput sequencing |

| ATP |

Adenosine Triphosphate |

| BE |

Base Editing |

| ChIP-seq |

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation sequencing |

| COX-2 |

Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| CPR |

Cytochrome P450 Reductase |

| CRISPR |

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| CRISPR-Cas9 |

CRISPR-associated protein 9 |

| CRISPRi |

CRISPR interference |

| CYP |

Cytochrome P450 |

| DMAPP |

Dimethylallyl Diphosphate |

| DXS |

1-Deoxy-D-Xylulose-5-Phosphate Synthase |

| EFSA |

European Food Safety Authority |

| ER |

Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| FAD3 |

Fatty Acid Desaturase 3 |

| FPP |

Farnesyl Diphosphate |

| G6PDH |

Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase |

| GA3 |

Gibberellin A3 |

| GC-MS |

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| GEMs |

Genome-scale Metabolic Models |

| GGPP |

Geranylgeranyl Diphosphate |

| GMO |

Genetically Modified Organism |

| GPP |

Geranyl Diphosphate |

| GRNs |

Gene Regulatory Networks |

| HMG-CoA |

3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA |

| HMGR |

3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA Reductase |

| HRMS |

High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry |

| IDI |

Isopentenyl Diphosphate Isomerase |

| IMS |

Ion Mobility Spectrometry |

| IPK |

Isopentenyl Phosphate Kinase |

| IPP |

Isopentenyl Diphosphate |

| iNOS |

Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| IUP |

Isopentenol Utilization Pathway |

| JA |

Jasmonate |

| JAZ |

Jasmonate ZIM-domain |

| LC-MS/MS |

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| MAFF |

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (Japan) |

| MD |

Molecular Dynamics |

| MeJA |

Methyl Jasmonate |

| MEP |

Methylerythritol Phosphate pathway |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| MVA |

Mevalonate pathway |

| NADPH |

Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (reduced form) |

| NF-κB |

Nuclear Factor kappa B |

| NMR |

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| oxPPP |

Oxidative Pentose Phosphate Pathway |

| PAL |

Phenylalanine Ammonia-Lyase |

| PDH |

Pyruvate Dehydrogenase |

| PE |

Prime Editing |

| PEPC |

Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxylase |

| POR |

Protochlorophyllide Oxidoreductase |

| PSY |

Phytoene Synthase |

| PTMs |

Post-Translational Modifications |

| RNAi |

RNA Interference |

| RNA-seq |

RNA Sequencing |

| RNP |

Ribonucleoprotein |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SA |

Salicylic Acid |

| scRNA-seq |

Single-cell RNA Sequencing |

| SDN-1 |

Site-Directed Nuclease 1 |

| SEM |

Structural Equation Modeling |

| SQS |

Squalene Synthase |

| SRM |

Selected Reaction Monitoring |

| SWATH-MS |

Sequential Window Acquisition of All Theoretical Mass Spectra |

| TF |

Transcription Factor |

| TLA |

Three Letter Acronym (included as per example) |

| TMT |

Tandem Mass Tag |

| TPS |

Terpene Synthase |

| UGT |

UDP-Glycosyltransferase |

| USDA |

United States Department of Agriculture |

| VIGS |

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing |

| WGCNA |

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis |

References

- Abdullah, Jiang, Z., Hong, X., Zhang, S., Yao, R., and Xiao, Y. (2020). CRISPR base editing and prime editing: DSB and template-free editing systems for bacteria and plants. Synth Syst Biotechnol 5, 277-292. [CrossRef]

- Agapakis, C. M., Niederholtmeyer, H., Noche, R. R., Lieberman, T. D., Megason, S. G., Way, J. C., and Silver, P. A. (2011). Towards a synthetic chloroplast. PLoS One 6, e18877. [CrossRef]

- Aharoni, A., Giri, A. P., Deuerlein, S., Griepink, F., de Kogel, W.-J., Verstappen, F. W. A., Verhoeven, H. A., Jongsma, M. A., Schwab, W., and Bouwmeester, H. J. (2003). Terpenoid metabolism in wild-type and transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant Cell 15, 2866-2884. [CrossRef]

- Aharoni, A., Jongsma, M. A., Kim, T.-Y., Ri, M.-B., Giri, A. P., Verstappen, F. W. A., Schwab, W., and Bouwmeester, H. J. (2006). Metabolic engineering of terpenoid biosynthesis in plants. Phytochem. Rev 5, 49-58. [CrossRef]

- Ajikumar, P. K., Xiao, W. H., Tyo, K. E., Wang, Y., Simeon, F., Leonard, E., Mucha, O., Phon, T. H., Pfeifer, B., and Stephanopoulos, G. (2010). Isoprenoid pathway optimization for Taxol precursor overproduction in Escherichia coli. Science 330, 70-74. [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayri, J. M., Sudheer, W. N., Lakshmaiah, V. V., Mukherjee, E., Nizam, A., Thiruvengadam, M., Nagella, P., Alessa, F. M., Al-Mssallem, M. Q., and Rezk, A. A. (2022). Biotechnological approaches for production of artemisinin, an anti-malarial drug from Artemisia annua L. Molecules 27, 3040. [CrossRef]

- Amini, H., Naghavi, M. R., Shen, T., Wang, Y., Nasiri, J., Khan, I. A., Fiehn, O., Zerbe, P., and Maloof, J. N. (2019). Tissue-specific transcriptome analysis reveals candidate genes for terpenoid and phenylpropanoid metabolism in the medicinal plant Ferula assafoetida. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 9, 807-816. [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, A. G., Waltenberger, B., Pferschy-Wenzig, E.-M., Linder, T., Wawrosch, C., Uhrin, P., Temml, V., Wang, L., Schwaiger, S., and Heiss, E. H. (2015). Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: A review. Biotechnol Adv 33, 1582-1614. [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, A. G., Zotchev, S. B., Dirsch, V. M., and Supuran, C. T. (2021). Natural products in drug discovery: advances and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov 20, 200-216. [CrossRef]

- Bai, W., Li, C., Li, W., Wang, H., Han, X., Wang, P., and Wang, L. (2024). Machine learning assists prediction of genes responsible for plant specialized metabolite biosynthesis by integrating multi-omics data. BMC Genom 25, 418. [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, M. C., Celik Altunoglu, Y., Baloglu, P., Yildiz, A. B., Türkölmez, N., and Özden Çiftçi, Y. (2022). Gene-Editing Technologies and Applications in Legumes: Progress, Evolution, and Future Prospects. Front Genet 13. [CrossRef]

- Bat-Erdene, U., Billingsley, J. M., Turner, W. C., Lichman, B. R., Ippoliti, F. M., Garg, N. K., O’Connor, S. E., and Tang, Y. (2021). Cell-Free Total Biosynthesis of Plant Terpene Natural Products using an Orthogonal Cofactor Regeneration System. ACS Catal 11, 9898-9903. [CrossRef]

- Bathe, U., Frolov, A., Porzel, A., and Tissier, A. (2019). CYP76 Oxidation Network of Abietane Diterpenes in Lamiaceae Reconstituted in Yeast. J Agric Food Chem 67, 13437-13450. [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, M., De Marchis, F., and Pompa, A. (2018). The endoplasmic reticulum is a hub to sort proteins toward unconventional traffic pathways and endosymbiotic organelles. J Exp Bot 69, 7-20. [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, S. J., Kumar, M., Ramrao Devde, P., Rai, A. C., Mishra, A. K., Singh, P. K., and Siddique, K. H. M. (2023). Progress in gene editing tools, implications and success in plants: a review. Frontiers in Genome Editing 5, 1272678. [CrossRef]

- Booth, J. K., Yuen, M. M. S., Jancsik, S., Madilao, L. L., Page, J. E., and Bohlmann, J. (2020). Terpene synthases and terpene variation in Cannabis sativa. Plant Physiol 184, 130-147. [CrossRef]

- Boutanaev, A. M., Moses, T., Zi, J., Nelson, D. R., Mugford, S. T., Peters, R. J., and Osbourn, A. (2015). Investigation of terpene diversification across multiple sequenced plant genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, E81-E88. [CrossRef]

- Boynton, J. E., Gillham, N. W., Harris, E. H., Hosler, J. P., Johnson, A. M., Jones, A. R., Randolph-Anderson, B. L., Robertson, D., Klein, T. M., Shark, K. B., and et al. (1988). Chloroplast transformation in Chlamydomonas with high velocity microprojectiles. Science 240, 1534-1538. [CrossRef]

- Cao, K., Cui, Y., Sun, F., Zhang, H., Fan, J., Ge, B., Cao, Y., Wang, X., Zhu, X., and Wei, Z. (2023). Metabolic engineering and synthetic biology strategies for producing high-value natural pigments in Microalgae. Biotechnol Adv 68, 108236. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.-S., and Wu, C.-C. (2013). Systems biology as an integrated platform for bioinformatics, systems synthetic biology, and systems metabolic engineering. Cells 2, 635-688. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Zheng, Y., Zhong, Y., Wu, Y., Li, Z., Xu, L.-A., and Xu, M. (2018). Transcriptome analysis and identification of genes related to terpenoid biosynthesis in Cinnamomum camphora. BMC genomics 19, 550. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F., Tholl, D., D’Auria, J. C., Farooq, A., Pichersky, E., and Gershenzon, J. (2003). Biosynthesis and emission of terpenoid volatiles from Arabidopsis flowers. Plant Cell 15, 481-494. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K. H., Boettiger, A. N., Moffitt, J. R., Wang, S., and Zhuang, X. (2015). Spatially resolved, highly multiplexed RNA profiling in single cells. Science 348, aaa6090. [CrossRef]

- Chung, C. H., Lin, D.-W., Eames, A., and Chandrasekaran, S. (2021). Next-generation genome-scale metabolic modeling through integration of regulatory mechanisms. Metabolites 11, 606. [CrossRef]

- Clough, S. J., and Bent, A. F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16, 735-743. [CrossRef]

- Cong, L., Ran, F. A., Cox, D., Lin, S., Barretto, R., Habib, N., Hsu, P. D., Wu, X., Jiang, W., and Marraffini, L. A. (2013). Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819-823. [CrossRef]

- Cong, L., Ran, F. A., Cox, D., Lin, S., Barretto, R., Habib, N., Hsu, P. D., Wu, X., Jiang, W., Marraffini, L. A., and Zhang, F. (2013). Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819-823. [CrossRef]

- Courdavault, V., O’Connor, S. E., Jensen, M. K., and Papon, N. (2021). Metabolic engineering for plant natural products biosynthesis: new procedures, concrete achievements and remaining limits. Nat Prod Rep 38, 2145-2153. [CrossRef]

- Czechowski, T., Li, Y., Gilday, A. D., Harvey, D., Swamidatta, S. H., Lichman, B. R., Ward, J. L., and Graham, I. A. (2025). Evolution of linear triterpenoid biosynthesis within the Euphorbia genus. Nat Commun 16, 5602. [CrossRef]

- Dahal, S., Yurkovich, J. T., Xu, H., Palsson, B. O., and Yang, L. (2020). Synthesizing systems biology knowledge from omics using genome-scale models. Proteomics 20, 1900282. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z., Liu, Y., Zhang, X., Shi, M., Wang, B., Wang, D., Huang, L., and Zhang, X. (2013). Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for production of ginsenosides. Metabolic engineering 20, 146-156. [CrossRef]