Introduction

Globally in 2018, fifty-nine countries reported resistance to ciprofloxacin and Cefixime. Studies from Uganda have shown even a much higher resistance to Ciprofloxacin of greater than 68% and the prevalence of gonorrhea in Uganda is still high

[10]. If nothing is done about the resistance of

Neisseria gonorrhoeae to antibiotics like ciprofloxacin and cefixime, then management of gonorrhea will get out of hand as all the few available antibiotics will have become less or non-effective [

10]. However despite of the increasing resistance and fewer effective antibiotics available, there are no recent reviews done on the resistance of

Neisseria gonorrhoeae to Ciprofloxacin and Cefixime. Therefore this research was aimed at reviewing the studies that have been carried out regarding the resistance of gonorrhea to the commonly used antibiotics.

Material and Methods

Search Engine

The search engine used was Google.

Search Words

The search words used were: prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to cefixime and ciprofloxacin, mechanism of resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, recommended alternative treatments for cefixime, ciprofloxacin resistant gonorrhea.

Data Base

The researcher used PubMed database and Google scholar as the principle source of data for this systematic review.

Data Presentation and Interpretation

The collected data was presented in form of tables.

Qualitative and quantitative susceptibility data was interpreted in context of the methodology utilized for testing (e.g., Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI], European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing [EUCAST], Calibrated Dichotomous Sensitivity [CDS]; disc testing, MIC by agar dilution).

Relationships and comparisons of qualitative and quantitative data within and between studies were described from which conclusions about results were made.

Ethical Considerations

Since this kind of work involved use of a copyrighted work, efforts were made to ensure that there was no plagiarism and all sources of primary data were appropriately referenced.

Results

Introduction

This chapter consists of the results for prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to cefixime and ciprofloxacin, mechanism of Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to cefixime and ciprofloxacin and the recommended alternative treatment for cefixime, ciprofloxacin resistant gonorrhea.

Prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Resistance to Cefixime and Ciprofloxacin

Resistance to cefixime is defined as MIC ≥ 0.125 mg/L, resistance to ciprofloxacin is defined as MIC ≥ 0.006mg/L (EUCAST, 2019) and CLSI.

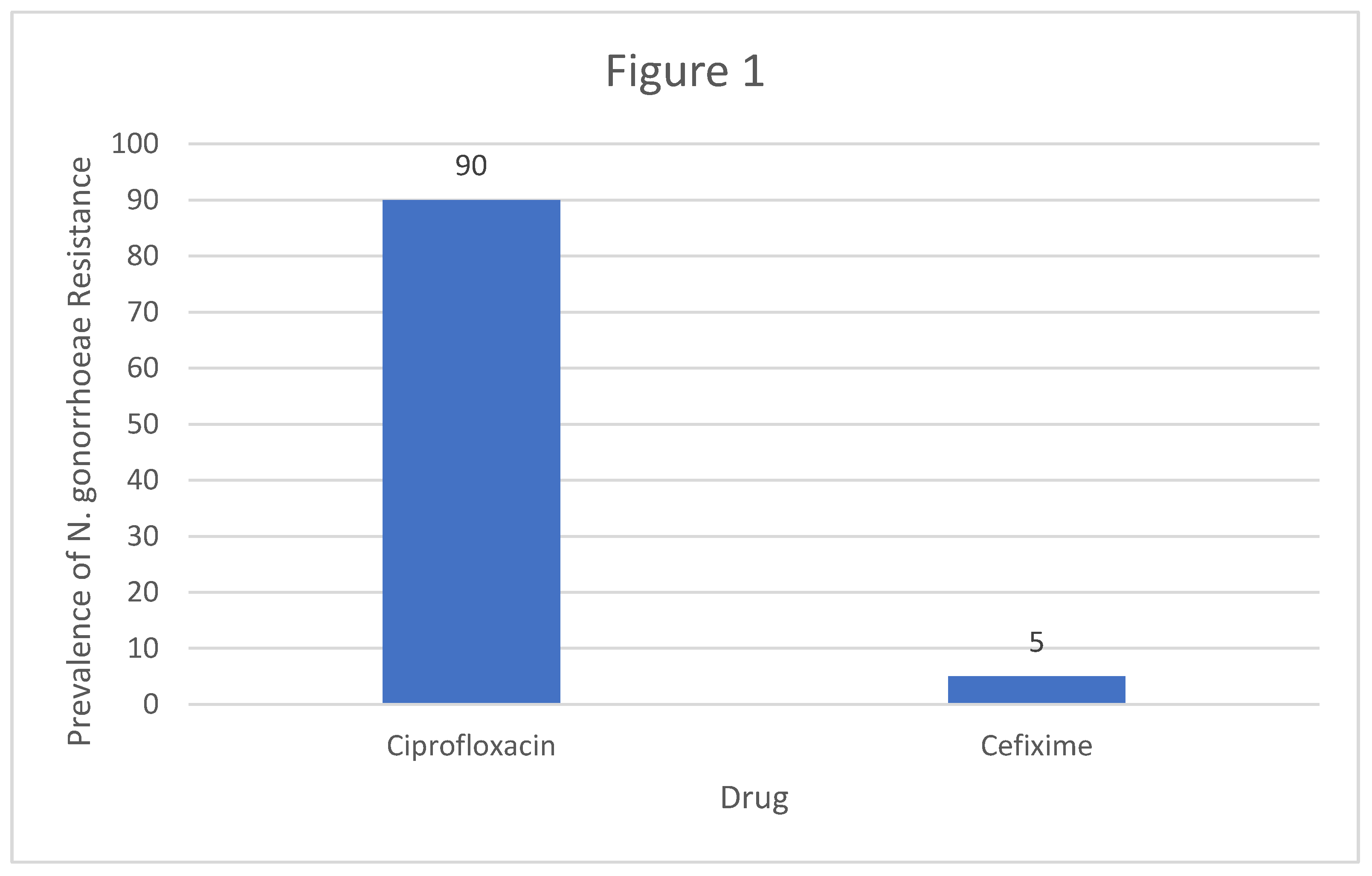

Table 1 below shows the summary of studies which were reviewed regarding the prevalence of

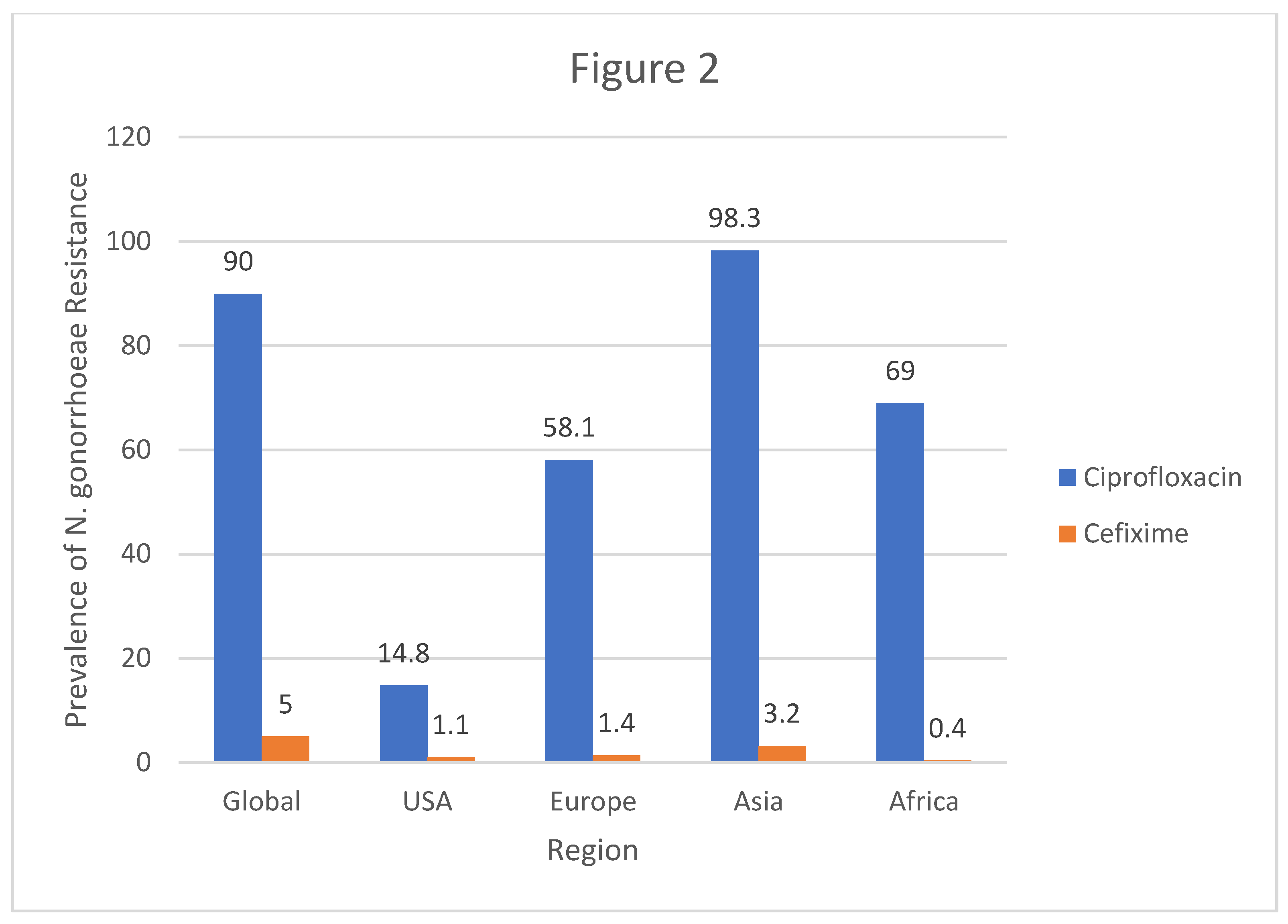

Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to cefixime and ciprofloxacin. In all the studies which were reviewed,

Neisseria gonorrhoeae had the highest prevalence of resistance to Ciprofloxacin whereas resistance to Cefixime was minimal. According to the study conducted by World health Organization, the prevalence of

Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to Ciprofloxacin was at 90% whereas the resistance to Cefixime was at 5%. United states recorded a lower prevalence of resistance to Ciprofloxacin standing at 14.8% and resistance to Cefixime was at 1.1%.

In Europe, the prevalence of resistance to Ciprofloxacin was 58.3% with prevalence of resistance to Cefixime being 1.4%. United Kingdom had a 34% prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to Ciprofloxacin with a 5% resistance to Cefixime. In Portugal, there was a 37% resistance to Ciprofloxacin meanwhile the resistance to Cefixime was 3%. A study from Austria revealed that Neisseria gonorrhoeae had a 65.6% resistance to Ciprofloxacin and a 4.2% resistance to Cefixime.

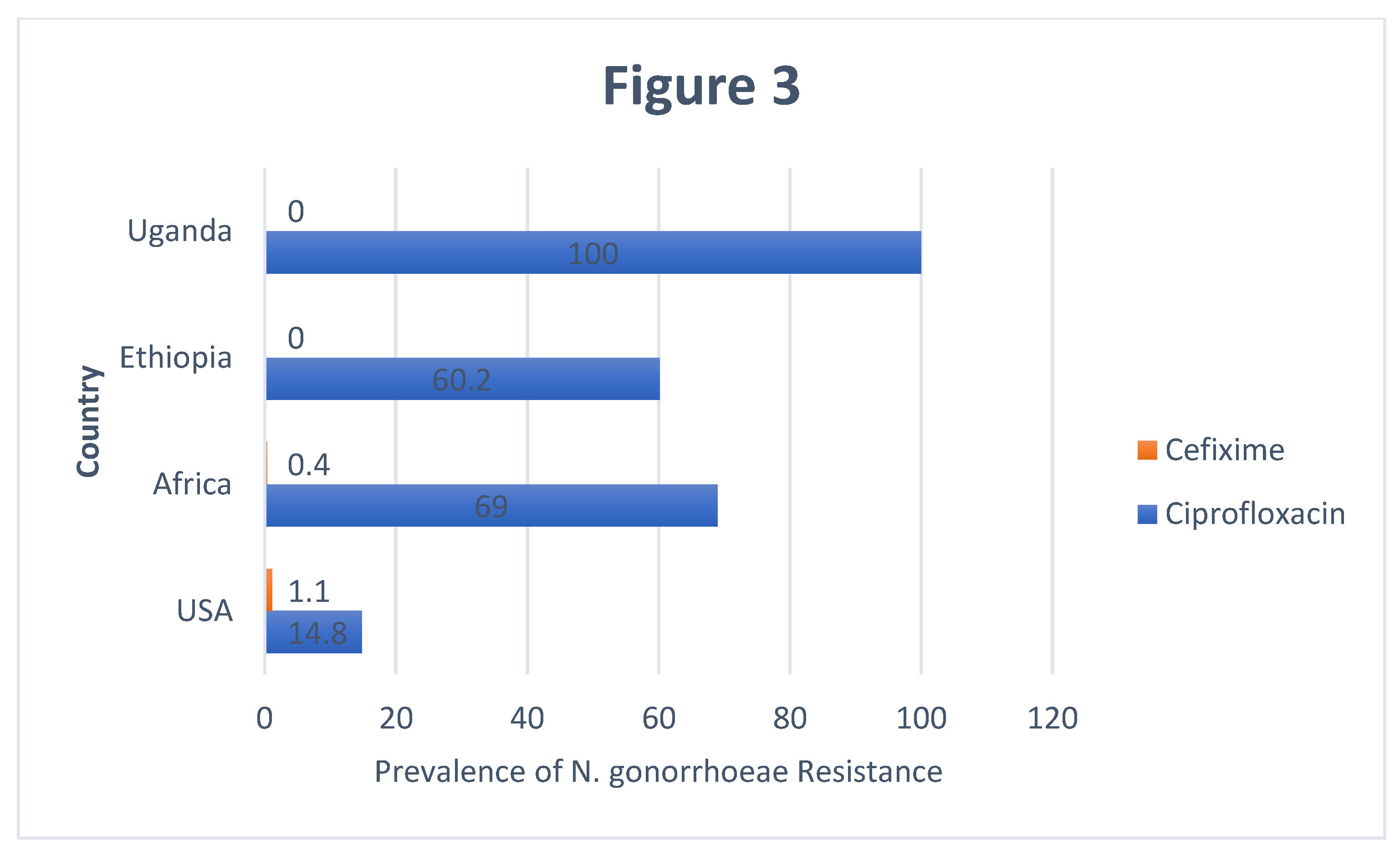

On the other hand, evidence from Asia shows that the prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to Ciprofloxacin was at 98.3% whereas the resistance to Cefixime was at 3.2%. Africa had a prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to Ciprofloxacin at 69% and resistance to Cefixime was at 0.4%. Another study conducted from Ethiopia showed that prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to Ciprofloxacin was 60.2% and resistance to Cefixime was at 0%. Lastly, a Ugandan based study revealed that prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to Ciprofloxacin was 100% meanwhile resistance to Cefixime was found to be 0%.

Mechanisms of Resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to Cefixime and Ciprofloxacin

Table 2 shows the Mechanisms of resistance of

Neisseria gonorrhoeae to cefixime and ciprofloxacin. Publication from [

29] showed that

Neisseria gonorrhoeae resists Ciprofloxacin through three substitutions (gyrA substitutions S91F/D95G and parC substitution S87R) meanwhile 16 & 28 ascertained that the resistance mechanism was through the acquisition of certain genes and the development of mutations in specific genes and in their regulatory regions. Furthermore, 22 and 8 reported that target modification or protection reducing antimicrobial affinity is the mechanism by which

Neisseria gonorrhoeae developed reduced susceptibility to Ciprofloxacin and Cefixime. Finally, 8 provided evidence that the mechanism by which

Neisseria gonorrhoeae becomes resistant to Ciprofloxacin and Cefixime is by decreased influx of antimicrobial and increased efflux of antimicrobials.

Alternative Treatment for Cefixime, Ciprofloxacin Resistant gonorrhea

Basing on the different prevalence rates of resistance of

Neisseria gonorrhoeae to Ciprofloxacin, Cefixime and other antibiotics that were previously used to treat gonorrhea infections, different countries came up with alternative antibiotics to treat the infection and the summary is shown in

Table 3. The most commonly used antibiotic in Uganda for the management of gonorrhea is ceftriaxone which is a 3rd generation cephalosporin followed by Azithromycin. The recommendation is for Ceftriaxone to be administered intramuscularly and for Azithromycin to be administered orally. Other antibiotics used include: Spectinomycin, Gentamycin and Gemifloxacin

Discussion

Prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Resistance to Cefixime and Ciprofloxacin

In this review the researcher summarized the findings reported for the prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to cefixime and ciprofloxacin which was analyzed by reviewing MIC measured using different antibiotic susceptibility testing methods (E-test, agar dilution, disc diffusion), breakpoints for MIC were interpreted using EUCAST. Resistance to cefixime was defined as MIC ≥ 0.125 mg/L, resistance to ciprofloxacin is defined as MIC ≥ 0.006mg/L . This review discovered significant resistance across the globe to cefixime and ciprofloxacin which are commonly used antibiotics in treatment of gonorrhea.

Regarding the resistance of

Neisseria gonorrhoeae to Ciprofloxacin, the worldwide study by WHO reported the prevalence of resistance to be 90% [

30]. This high prevalence of resistance to Ciprofloxacin can be attributed to the fact that the study was carried out globally and the possibility of erroneous reporting as well as mistakes when performing laboratory procedures in some regions cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, Ciprofloxacin being a cheaper drug implies that it has been widely used globally to treat Gonnorhea infections and hence the high global prevalence of resistance to it. To the contrary, in United States of America the prevalence of

Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to Ciprofloxacin was only 14.8% [

14]. This shows that the health workers in USA have been practicing rational use of antibiotics and perhaps the citizens of USA don’t do self-treatment but rather buy drugs from the pharmacy after getting prescriptions from qualified health professionals. Another reason for the low prevalence to Ciprofloxacin resistance in USA could be because of the strict pharmaceutical laws in USA where pharmaceutical outlets are not allowed to sell antibiotics over the counter without prescriptions from registered healthcare professionals.

In Europe, the resistance to Ciprofloxacin was 58.3% [

4] which is an implication that the drug has been used relatively widely for treating Gonorrhea infections hence the above average prevalence of resistance which was reported. The use of Ciprofloxacin for treating a number of other bacterial infections could also be the reason for the relatively high prevalence of its resistance by

Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Europe.

Asia reported a prevalence of 98.3% as the prevalence of

Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to Ciprofloxacin [

20]. This prevalence of resistance is extremely high due to the fact that majority of the population in Asia belong to low socio-economic status and are prone to Gonorrhea infections. Given the fact that Ciprofloxacin is cheaper, it implies that it has been used by majority of the population in Asia to treat Gonorrhea leading to mutations and hence resistance.

Data from Africa has revealed that the prevalence of

Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to Ciprofloxacin stands at 69% [

15]. This is lower than what was found in Asia much as Africa also has majority of its population belonging to low socio-economic status with a good number even living below the poverty level. The high prevalence of resistance to Ciprofloxacin could possibly be due to the irrational use of antibiotics by health workers and patients in Africa.

In Ugandan, studies have shown 100% prevalence of

Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to Ciprofloxacin [

18]. This could be because majority of Ugandans do self-treatment, they just walk to pharmacies or drug shops and buy medicine without consulting qualified health professionals. Such practices increases the chances of resistance on top of putting the lives of users at risk. Another reason for the 100% prevalence of resistance to Ciprofloxacin could be because of the laxity in the implementation of pharmaceutical laws which bar the pharmaceutical outlets from selling prescription medicines over the counter.

Pertaining to the prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to Cefixime, WHO reported that the global prevalence of resistance was 5%. This is an implication that Cefixime has not yet been used extensively to treat Gonorrhea infections hence the bacteria has undergone very little mutation to reduce its susceptibility to Cefixime. Europe and United States of America reported the prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to Cefixime at approximately 1%. This can be attributed to the good clinical practices of the health workers who treat clients after making the necessary laboratory investigations other than treating clients basing on signs and symptoms.

The prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to Cefixime in Africa is 0.4%. This is probably because Cefixime is an expensive drug which may not be affordable by vast majority of the African population, hence less exposure and less resistance from Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Ethiopia and Uganda reported 0% prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to Cefixime. This is probably because majority of government hospitals don’t have Cefixime and yet majority of Ugandan population seek health care services from government health facilities. As such, Cefixime can be found in Private facilities and its expensive making it to be used by few clients and hence Few cases of resistance from Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

In the settings with high prevalence of resistance, there is easy access to antibiotics in the informal health sector [

1]. This is in line with the results of a study which revealed that about 75% of those attending an STD clinic in Ghana had self-medicated prior to presentation to the clinic [

4]. The antibiotics had been acquired from a variety of sources and were taken in inappropriate doses, often as mixtures of different agents. Between 70 and 95% of gonococci examined at this clinic were resistant to commonly used antibiotics. Anecdotal reports tell of commercial sex workers in Asia supplying clients with oral quinolones as a means of ‘prophylaxis’, and self-prescribing of prophylactic antibiotics in CSWs in the Philippines was a factor contributing to the emergence of anti-microbial resistance in that country [

15].

Overall, although antimicrobial resistance varies across the globe, the researcher found that Neisseria gonorrhoeae has little susceptibility or a higher percentage of resistance to ciprofloxacin than cefixime. This is probably because Cefixime is a stronger antibiotic compared to Ciprofloxacin. Furthermore, Cefixime has had less exposure as it has not yet been widely used in treatment of Gonorrhea infections as compared to Ciprofloxacin.

Mechanism of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Resistance to Cefixime and Ciprofloxacin

The mechanisms of

Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance include, (i) enzymatic antimicrobial destruction or modification, (ii) target modification or protection reducing affinity for the antimicrobial, (iii) decreased influx of antimicrobials, and (iv) increased efflux of antimicrobial [

4].

Gonococci are essentially non-clonal organisms; they are highly transformable, acquiring DNA from closely related species, and also undergo antigenic variations that regularly alter their phenotype and genotype [

20], thereby reducing their susceptibility to frequently used antibiotics. The quinolone antibiotics most widely used for the treatment of gonorrhoea are second generation cephalosporins such as ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin.

In a manner reminiscent of the development of chromosomal penicillin resistance, resistance to these antibiotics has developed incrementally over a number of years and multiple chromosomal changes are involved. Access of quinolones to their targets is reduced by changes in cell permeability and possibly by efflux mechanisms. These events produce low-level quinolone resistance [

22].

The present study findings are similar to those reported in studies from Portugal in 2010 [

11] and Italy in 2008 [

27], in which 37.4% (70/187) and 34.2% (111/326), respectively, were QRNG isolates. High levels of QRNG have been reported in several European countries, with 63% (861/1366) of isolates [

28]. Several authors have observed that the prevalence of this phenotype remains high in various regions of the world [

28]. The presence of two mutations in GyrA (including S91F) together with mutations in the ParC protein has been associated with the development of full resistance to ciprofloxacin [

16].

The genetic mechanisms of

N. gonorrhoeae resistance to antibacterial agents such as Ciprofloxacin and Cefixime include the acquisition of certain genes and the development of mutations in specific genes and in their regulatory regions [

3]. The resistance mechanisms developed by

N. gonorrhoeae to fluoroquinolones are due to mutations in the gyrA and parC genes in a well-defined area called the quinolone resistance determining region (QRDR). The resistance of these bacteria to ESCs is mainly due to mutations that modify the action target (penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs)) (penA and ponA genes) [

8,

16,

28].

Gonorrhea resistance to ciprofloxacin is mediated by mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR), located near the topoisomerases DNA binding site. The main resistance mechanism for quinolone ( ciprofloxacin) is target modification and in this case two genes are involved ,gyrA and para C.REF mutations in gyrA causes alteration in the primary target of DNA gyrase which results in reduced ciprofloxacin binding affinity while mutation in ParC gene affect the two ParC subunits in topoisomerase IV and it is responsible for high level of resistance [

5].

Quinolone-resistant gonococci(QRNG) have emerged and spread relatively recently in areas with a high burden of gonococcal disease combined with antibiotic over use or misuse [

30]. Emergence and spread of QRNG may have been accelerated by the introduction of the quinolones for the treatment of other diseases. Initially, gonococci were extremely susceptible to quinolones. Resistance, which is exclusively chromosomally mediated, has developed incrementally.

The targets of the quinolones are topoisomerases, including DNA gyrase. High-level clinically relevant resistance is mediated by alteration of the target sites, initially via mutation in the gyrA gene. Multiple amino acid substitutions have been described which, when combined, result in high-level resistance. Multiple mutations also occur in the parC gene which codes for the production of topoisomerase IV, a secondary target for quinolonesin gonococci, but again found in association with high-level resistance. Changes in ParC seem to arise in the presence of mutations affecting GyrA. The more recent (fourth generation) quinolones are more active against strains with altered ParC, but are less effective against GyrA mutants. Thus, these compounds will in theory be active against some, but not all, ciprofloxacin-resistant gonococci.

Cefixime resistance is almost exclusively mediated by chromosomal mutations, which affect either the target sites or access of the antibiotic to the cell. Plasmid-mediated resistance to nalidixic acid in Shigella dysenteriae was reported in 1987 but was never confirmed [

1]. Plasmid-mediated resistance was recently reported in a clinical isolate of Klebsiella pneumoniae. The resistance determinant was carried on a broad host range plasmid and was transferable to other Enterobacteriaceae and to

Pseudomonas aeruginosa [

4]. It is no accident that antibiotic-resistant N. gonorrhoeae emerged in regions where there is a large informal health sector and the use of antibiotics is not well controlled.

Gonorrhoeae resistance to cefixime is mediated by mutations in penA, penB, penC, porB1b gene, ponA gene and over expression of Mtr CDE membrane pump proteins.PorB1b mutational changes reduces influx of cefixime, mtrR, over expression of MtrCDE membrane pump proteins (efflux pump) causes increased efflux of antimicrobial and in the penA gene that encodes the transpeptidase domain of the PBP2 protein, this mutation changes causes target modification or protection reducing affinity for cefixime hence increased resistance to cefixime which is also the same as reduced susceptibility to Cefixime. The penA gene plays the most important role in the emergence of chromosomal resistance or reduced susceptibility to cefixime [

5]. This is responsible for the resistance of

Neisseria gonorrhoeae to Cefixime.

Recommended Alternative Treatments for Cefixime, Ciprofloxacin Resistant gonorrhea

Based on the prevalence of resistance to Ciprofloxacin and Cefixime in different countries, the treatment alternatives vary slightly, especially concerning antimicrobial doses. Studies showing high ciprofloxacin resistance encourage ciprofloxacin to be replaced by ceftriaxone in those states [

15]. The vast group of countries (U.S., European countries, Australia, and others) recommend a combination of ceftriaxone- azithromycin for therapy [

1,

20,

25]. The WHO Guidelines for the treatment of

N. gonorrhoeae based on data from high, middle- and low-income countries, published in 2016, it recommended ceftriaxone plus azithromycin primarily for treatment of genital and anorectal gonococcal infections [

30]. Over the last 80 years,

N. gonorrhoeae has developed or acquired resistance mechanisms to sulfonamides, penicillins, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and more recently azithromycin and ceftriaxone, making this microorganism a candidate to cause an untreatable disease [

1].

Given the fact that Ceftriaxone is administered intramuscularly, its efficacy is higher than that of Azithromycin as it is administered orally and its efficacy may be reduced by certain enzymes in the gut as well as delayed absorption due to differences in physiology of different individuals. As it is administered orally, azithromycin may also be subjected to drug-drug interaction and drug-food interactions. All these reduce the efficacy of Azithromycin in treating gonococci infections. Regarding toxicity, due to first pass metabolism Azithromycin is less toxic compared to Ceftriaxone. Furthermore, Ceftriaxone is eliminated partly in the bile and partly in the urine. Soon after it came on the market, it was shown sonographically that it could precipitate in the gallbladder [

26], and “biliary sludge” or biliary pseudolithiasis, is now a well-known adverse effect. In the last few years, an increasing number of reports have shown that urinary sludge and/or calculi can also form due to ceftriaxone use.

The current recommended alternative treatment by WHO for cefixime, ciprofloxacin resistant gonorrhea is Ceftriaxone given intramuscularly + azithromycin or cefixime 400mg PO +azithromycin [

30]. Despite these international recommendations, in Uganda ciprofloxacin is still commonly used to treat gonococcal diseases, as it is readily available at no cost in many government health facilities. Cefixime is provided by the government but is liable to stock outs , therefore a number of patients are given a private prescription [

18].

Conclusions

Resistance was found not to be uniform within regions or countries, and can emerge quickly in any locality. It may spread rapidly or slowly, depending on a number of factors, including the mechanism of resistance and whether the strain is being spread by core transmitters. Continual monitoring of antibiotic susceptibility is required to ensure effective treatment.

This review generated strong evidence that ciprofloxacin should certainly not be used as an empirical treatment for gonorrhea. Results from the study showed that all isolates that showed resistance to cefixime were resistant to ciprofloxacin, Results showed that only two articles of those reviewed showed no resistance to cefixime (Uganda and Ethiopia) providing evidence that cefixime can still be used in some countries as a fine line recommendation in treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea

From a global public health perspective, the results of this study were consistent with those of other authors and reinforce the importance of the expedient development of new therapeutic options with new antimicrobial agents or other types of therapeutic molecules. Taking into account the fact that, as in other studies, some N.gonorrhoeae isolates presenting resistance mutations were susceptible to antibiotics, further studies are needed using molecular biology techniques, such as multi-antigen sequence typing, to predict specific antimicrobial resistance.

Recommendation

Since antibiotic resistance affects our ability to treat and control gonorrhoea, continuing surveillance is essential to monitor both its emergence and spread. Population-based surveillance of susceptibility patterns is required in order to establish standardized treatment regimens that cure at least 95% of infections and to modify the regimens when the situation changes. For this purpose, samples of gonococcal isolates must be sufficiently large and representative.

Effective surveillance requires both laboratory facilities and procedures capable of detecting resistance and the infrastructure for handling and analysing data. Surveillance based on clinical outcome involves issues such as accuracy of diagnosis, compliance with therapy, definition of ‘cure’ and follow-up assessment, and needs to be supported by valid laboratory data.

Effective surveillance of AMR is limited by the fact that gonorrhoea occurs most frequently in resource-poor settings where facilities are not available for isolation and susceptibility testing off astidious organisms. Antibiotic-resistant gonococci may be introduced into new areas by travellers, and in these cases it is recommended that treatment be ‘chosen according to international data on sensitivities.

Table 4.

A table showing the Mechanisms of resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to cefixime and ciprofloxacin.

Table 4.

A table showing the Mechanisms of resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to cefixime and ciprofloxacin.

| Resistance mechanism |

Genes Involved |

Reference |

| Three substitutions that are associated with reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones (gyrA substitutions S91F/D95G and parC substitution S87R) |

Analysis of the ponA (penicillin-binding protein 1) sequence revealed a leucine to proline substitution (L421P) previously associated with reduced penicillin susceptibility. Glycine to lysine (G210K) and alanine to histidine mutations (A121N) were detected in penB (porB1b). |

(Washington et al., 2018) |

| The acquisition of certain genes and the development of mutations in specific genes and in their regulatory regions |

The resistance of these bacteria to ESCs is mainly due to mutations that modify the action target (penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs)) (penA and ponA genes)

The resistance mechanisms developed by N. gonorrhoeae to fluoroquinolones are due to mutations in the gyrA and parC genes in a well-defined area called the quinolone resistance determining region (QRDR). |

(Kunz et al., 2012; Unemo, Ballard, et al., 2013) |

Target modification or protection reducing antimicrobial affinity

|

Alterations in penB, mtrR, and penC gene. The altered penA gene can result from point mutations, or from genetic recombination between commensal Neisseria spp. colonizing other human sites, the last generating a mosaic-like structure. The altered PBP2 presents diminished affinity to Ciprofloxacin. |

(Paula et al., 2017) |

Target modification or protection reducing antimicrobial affinity

|

Pen A mutational changes (decreases cefixime acylation of PBP2, 6 to 8 folds) resulting in chromosomal resistance or reduced susceptibility to cefixime.

GyrA mutational changes reduces ciprofloxacin binding to DNA gyrase.

ParC reduces ciprofloxacin biding to topoisomeraseIV |

(Costa-Lourenço et al., 2017) |

Decreased influx of antimicrobials

|

PorB1b mutational changes reduces influx of cefixime.

Pil Q |

(Costa-Lourenço et al., 2017) |

Increased efflux of antimicrobials.

|

mtrR, overexpression of MtrCDE membrane pump proteins (efflux pump). |

(Costa-Lourenço et al., 2017) |

Figure 1.

A column Graph showing the Global prevalence of resistance of N.Gonnorhea to Ciprofloxacin and Cefixime.

Figure 1.

A column Graph showing the Global prevalence of resistance of N.Gonnorhea to Ciprofloxacin and Cefixime.

Figure 2.

Column Graph showing the Regional prevalence of resistance of N.Gonnorhea to Ciprofloxacin and Cefixime.

Figure 2.

Column Graph showing the Regional prevalence of resistance of N.Gonnorhea to Ciprofloxacin and Cefixime.

Figure 3.

A Bar Graph showing the Comparison of prevalence of N.Gonnorhea to Ciprofloxacin and Cefixime in Uganda, Ethiopia, Africa and USA.

Figure 3.

A Bar Graph showing the Comparison of prevalence of N.Gonnorhea to Ciprofloxacin and Cefixime in Uganda, Ethiopia, Africa and USA.

References

- Adamson, P. C. , Van Le, H., Le, H. H. L., Le, G. M., Nguyen, T. V., & Klausner, J. D. Trends in antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Hanoi, Vietnam, 2017–2019. BMC Infectious Diseases 2020, 20, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhashimi, M. , Mayhoub, A., & Seleem, M. N. Repurposing salicylamide for combating multidrug-resistant neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2019, 63, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. , Sewunet, T., Sahlemariam, Z., & Kibru, G. Neisseria gonorrhoeae among suspects of sexually transmitted infection in Gambella hospital, Ethiopia: risk factors and drug resistance. BMC Research Notes 2016, 9, 439. [Google Scholar]

- Buder, S. , Dudareva, S., Jansen, K., Loenenbach, A., Nikisins, S., Sailer, A., Guhl, E., Kohl, P. K., & Bremer, V. (2018). Antimicrobial resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Germany : low levels of cephalosporin resistance, but high azithromycin resistance. [CrossRef]

- Calado, J. , Castro, R., Lopes, Â., José, M., & Rocha, M. International Journal of Infectious Diseases Antimicrobial resistance and molecular characteristics of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from men who have sex with men. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2019, 79, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. (2019a). Antibiotic-Resistant Gonorrhea Basic Information, /: for Disease Control and Prevention. https.

- CDC. (2019b). Gonorrhea - CDC Fact Sheet (Detailed Version), /: for Disease Control and Prevention. https.

- Costa-Lourenço, A. P. R. da, Barros dos Santos, K. T., Moreira, B. M., Fracalanzza, S. E. L., & Bonelli, R. R. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: history, molecular mechanisms and epidemiological aspects of an emerging global threat. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 2017, 48, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Korne-Elenbaas, J. , Pol, A., Vet, J., Dierdorp, M., Van Dam, A. P., & Bruisten, S. M. Simultaneous Detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Fluoroquinolone Resistance Mutations to Enable Rapid Prescription of Oral Antibiotics. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 2020, 47, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fifer, H. , Saunders, J., Soni, S., Sadiq, S. T., & FitzGerald, M. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV national guideline for the management of infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae (2019). Bashh, /: https, 1208. [Google Scholar]

- Florindo, C. , Pereira, R., Boura, M., Nunes, B., Paulino, A., Gomes, J. P., & Borrego, M. J. Genotypes and antimicrobial-resistant phenotypes of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Portugal (2004–2009). Sexually Transmitted Infections 2010, 86, 449–453. [Google Scholar]

- Hailemariam, M. , Abebe, T., Mihret, A., & Lambiyo, T. Prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhea and their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns among symptomatic women attending gynecology outpatient department in Hawassa referral hospital, Hawassa, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences 2013, 23, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon, C. , Buyze, J., & Wi, T. Antimicrobial consumption and susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: A global ecological analysis. Frontiers in Medicine 2018, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkcaldy, R. D. , Kidd, S., Weinstock, H. S., Papp, J. R., & Bolan, G. A. Trends in antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the USA: The Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP), January 2006-June 2012. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 20 January. [CrossRef]

- Kularatne, R. , Maseko, V., Gumede, L., & Kufa, T. Trends in Neisseria gonorrhoeae Antimicrobial Resistance over a Ten-Year Surveillance Period. Antibiotics 2018, 7, 2008–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, A. N. , Begum, A. A., Wu, H., D’Ambrozio, J. A., Robinson, J. M., Shafer, W. M., Bash, M. C., & Jerse, A. E. Impact of fluoroquinolone resistance mutations on gonococcal fitness and in vivo selection for compensatory mutations. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2012, 205, 1821–1829. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, A. S. , Gwanzura, L., Machiha, A., Ndowa, F., Tarupiwa, A., Gudza-Mugabe, M., Shukusho, F. D., Musanhu, C. C., Wi, T., & Unemo, M. Antimicrobial susceptibility in Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from five sentinel surveillance sites in Zimbabwe, 2015–2016. Sexually Transmitted Infections 2018, 94, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mabonga, E. , Parkes-Ratanshi, R., Riedel, S., Nabweyambo, S., Mbabazi, O., Taylor, C., Gaydos, C., & Manabe, Y. C. Complete ciprofloxacin resistance in gonococcal isolates in an urban Ugandan clinic: findings from a cross-sectional study. International Journal of STD & AIDS 2019, 30, 256–263. [Google Scholar]

- Młynarczyk, B. , Anna, B., Magdalena, M., & Grażyna, M. Multiresistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae: a new threat in second decade of the XXI century. Medical Microbiology and Immunology, 5678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Młynarczyk, B. , Anna, B., Magdalena, M., & Grażyna, M. Multiresistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae : a new threat in second decade of the XXI century. Medical Microbiology and Immunology 2020, 209, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owokuhaisa, J. , & Bazira, J. Antimicrobial Resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Isolated from Out Patients Presenting with Urethral and Vaginal Discharges at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital. 2019, 30, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, A. , Thaís, K., Moreira, B. M., Eduardo, S., Fracalanzza, L., & Bonelli, R. R. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae : history, molecular mechanisms and epidemiological aspects of an emerging global threat. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 2017, 8, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, P. A. , Shafer, W. M., Ram, S., & Jerse, A. E. Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Drug Resistance, Mouse Models, and Vaccine Development. Annual Review of Microbiology 2017, 71, 665–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, J. , Vander Hoorn, S., Korenromp, E., Low, N., Unemo, M., Abu-Raddad, L. J., & Chico, R. (2019). Global and regional estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2016. WHO Bulletin. June.

- Sahile, A. , Teshager, L., Fekadie, M., & Gashaw, M. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns of Neisseria gonorrhoeae among Suspected Patients Attending Private Clinics in Jimma, Ethiopia. International Journal of Microbiology.

- Soni, A. , Chaudhary, M., & Dwivedi, V. K. Ceftriaxone-vancomycin drug toxicity reduction by VRP 1020 in Mus musculus mice. Current Clinical Pharmacology 2009, 4, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Starnino, S. , Suligoi, B., Regine, V., Bilek, N., Stefanelli, P., Group, N. gonorrhoeae I. S., Dal Conte, I., Fianchino, B., Delmonte, S., & Robbiano, F. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in parts of Italy: detection of a multiresistant cluster circulating in a heterosexual network. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2008, 14, 949–954. [Google Scholar]

- Unemo, M. , Ballard, R., Ison, C., Lewis, D., Ndowa, F., Peeling, R., & Organization, W. H. (2013). Laboratory diagnosis of sexually transmitted infections, including human immunodeficiency virus.

- Unemo, M. , Clarke, E., Boiko, I., Patel, C., Patel, R., & Group, E. C. Adherence to the 2012 European gonorrhoea guideline in the WHO European Region according to the 2018–19 International Union against Sexually Transmitted Infections European Collaborative Clinical Group gonorrhoea survey. International Journal of STD & AIDS 2020, 31, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Unemo, M. , del Rio, C., & Shafer, W. M. Antimicrobial Resistance Expressed by Neisseria gonorrhoeae: A Major Global Public Health Problem in the 21st Century. Emerging Infections 2016, 10, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unemo, M. , Ison, C. A., Cole, M., Spiteri, G., van de Laar, M., & Khotenashvili, L. Gonorrhoea and gonococcal antimicrobial resistance surveillance networks in the WHO European Region, including the independent countries of the former Soviet Union. Sexually Transmitted Infections.

- Unemo, M. , & Shafer, W. M. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the 21st Century: Past, evolution, and future. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2014, 27, 587–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, M. A. , Jerse, A. E., Rahman, N., Garges, E. C., Latif, N. H., & Akhvlediani, T. First description of a ce fi xime- and cipro fl oxacin-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolate with mutations in key antimicrobial susceptibility – determining genes from the country of Georgia. New Microbes and New Infections 2018, 24, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weston, E. J. , Wi, T., & Papp, J. Surveillance for Antimicrobial Drug-Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae through the Enhanced Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Emerging Infectious Diseases.

- WHO. (2016a). WHO Guidelines on the treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, /: World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia. https, 1066.

- WHO. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Global surveillance and a call for international collaborative action. PLoS Medicine 2017, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO, W. H. O. (2016b). Global health sector strategy on sexually transmitted infections 2016–2021. Towards ending STIs.

- WHO, W. H. O. Global action plan to control the spread and impact of antimicrobial resistance. Department of Reproductive Health and Research. Neisseria Gonorrhoeae. Geneva 2018, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zielke, R. A. , Wierzbicki, I. H., Baarda, B. I., & Sikora, A. E. The Neisseria gonorrhoeae Obg protein is an essential ribosome-associated GTPase and a potential drug target. BMC Microbiology 2015, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).