1. Introduction

Medicinal plants form the primary base of health care, not only for rural communities, but for urban communities as well and they also contribute as a source of income [

1]. Over the past twenty years there has been a drastic increase of interest in traditional systems of medicines and herbal medicines not just in developed countries but also in developing countries. Rapid commercialization of medicinal herbs has seen a significant growth in the economy [

2]. Medicinal plants have been proven to be safe therapeutics that are easily accessible and affordable. As such over 80% of the world's population rely on the use of medicinal plants as natural remedies [

3].

Moringa oleifera Lam. is known as a multipurpose plant with a vast variety of nutritional potential use [

4,

5].

Moringa oleifera is abundant in essential vitamins and minerals, with the leaves being the most nutritious part of the plant.

Moringa oleifera leaves have shown to be an excellent source of vitamin A, magnesium, calcium, vitamin B6, vitamin C and beta carotene pro-vitamin A [

6]. Previous studies have demonstrated that

M. oleifera leaves have been shown to have greater amounts of Vitamin A than found in carrots, more calcium than found in milk, as well as more iron than found in spinach [

7].

Moringa oleifera is also known to be an excellent source of vitamin C, which is contained more in the leaves than in oranges, as well as more potassium than in a banana. The quality of protein in the

M. oleifera leaves is similar to that found in milk and eggs [

7].

Moringa oleifera leaf contains amino acids, which are essential building blocks of proteins and phytochemical compounds that have important biological activities [

8]. The leaves can be consumed in many ways either fresh, cooked, dried leaf or crushed into a powder [

9]. Dried

M. oleifera leaves are expected to retain their nutrient content.

Moringa oleifera leaves can be dried and stored for up to a period beyond six months depending on the conditions. It is advisable to store the food in sealed packaging materials when dried with a required moisture content. To prevent microbiological contamination or moisture in dried products, packaging should be considered to be an integral part of food processing and preservation methods, as it depends on the appropriate packaging [

10,

11].

In various regions of South Africa, M. oleifera cultivation serves as a vital source of income and food security within communities due to its nutritional significance. As the demand for M. oleifera continues to rise for commercial purposes, ensuring proper storage becomes imperative to uphold its quality and prevent phytochemical degradation. Phytochemicals act as natural compounds devoid of nutritional value and function independently or in conjunction with vitamins and other nutrients to combat diseases. Many phytochemicals exhibit potent biological activities. Extended storage durations may lead to the depletion of both phytochemicals and some nutrients in plant material, potentially compromising their quality and diminishing their value. The challenge of storage is compounded by diverse environmental settings and economic constraints surrounding planting, harvesting, storage, and packaging.

Critical factors influencing storage include packaging methods and storage temperatures, pivotal in enhancing shelf life and preserving quality [

12]. Improper drying or storage of

M. oleifera powder can foster mold or mildew growth, posing issues ranging from unpleasant odours to potential harm [

10]. Implementing sound processing practices is essential to minimize microbial contamination, significantly impacting the overall quality and safety of medicinal products. Understanding the optimal post-harvest procedures, including drying, appropriate packaging, and storage methods, is crucial to maintain the quality of these plants and prevent degradation. Improper handling, inadequate drying, and subpar storage conditions can profoundly impact the biological, chemical, and physical composition of the plants, leading to unfavourable microbial alterations [

13,

14]. The aim of this study was to evaluate how varying storage temperatures and light exposure would affect the phytochemical levels, nutritional properties, and microbial contamination in

M. oleifera leaf powder.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Colour

2.1.1. Lightness (L*)

Figure 1 depicts the types of storage packaging used in the study, vis a vis, transparent plastic and opaque silver zipper bags. The effects of different packaging type and light exposure on the colour of

M. oleifera leaf powder are shown in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. The L* value represents the degree of lightness to darkness, a* represents the degree of redness and greenness and the b* value represents the yellowness and blueness. The colour parameters (L*, a*, ΔE) were used to determine the most suitable frequency for the study. These values were crucial in understanding the influence of the treatments to colour changes in the powder samples.

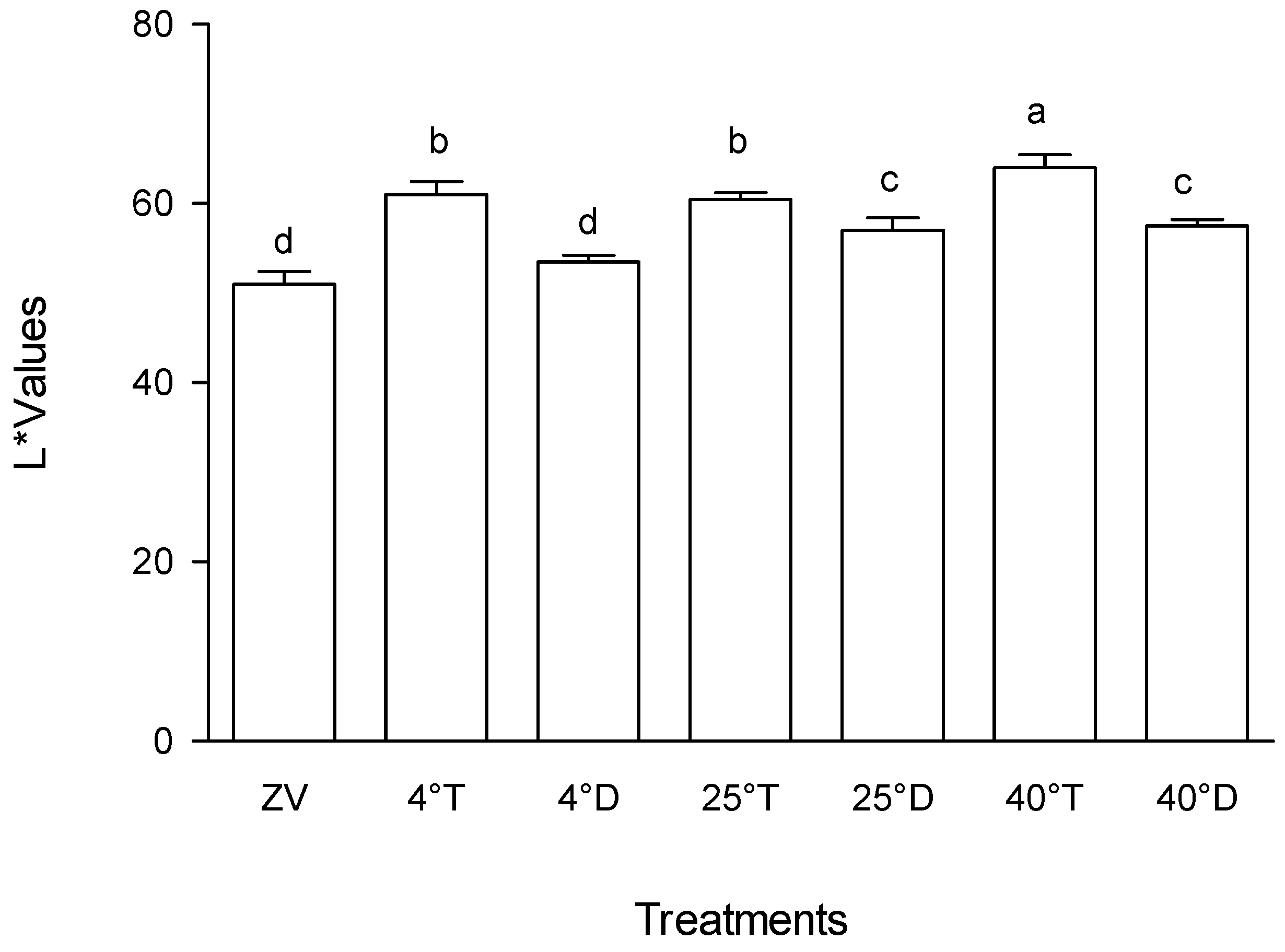

The colour analysis showed storage at 40°C with transparent packaging had a noticeably higher level of lightness (L*) than the other experimental treatments (p < 0.05), meaning high rate of colour fading (

Figure 2). On the other hand, storage at 4°C in a transparent packaging (

Figure 1A) and storage at 25°C in a transparent packaging showed somewhat moderate changes in L* values, which signified moderate changes in colour over time. Storage of

M. oleifera at 4°C in an opaque packaging (

Figure 1B) had lower Lightness L* values which were not very different from the initial readings taken at day Zero of the experiment, which meant little colour changes.

The outcomes observed among the various treatments denote intriguing patterns in the context of colour attributes within differing packaging and temperature conditions. Treatment A40T, characterized by transparent packaging at 40°C, notably exhibited significantly higher lightness (L*) in comparison to the other treatments investigated. This observation implies that under the specified conditions, the colour of the product experienced a perceptible increase in brightness. Such an outcome could indicate potential alterations in the visual appearance or perceived quality of the product due to this specific packaging and temperature combination. Moreover, the treatments Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging and storage at 25°C with transparent packaging also demonstrated relatively higher L* values, though without a discernible statistical variance between them (

Figure 2). This suggests a consistent trend in the colour enhancement effect, albeit not markedly distinguishable at the tested significance level. This finding underscores the influence of transparency across varied temperature conditions on the product's colour characteristics. Previous research has noted the impact of light presence on enhancing product lightness [

15]. In terms of food storage for

M. oleifera powder, an increase in the L* value representing lightness could be due to various factors. Exposure to light, especially in improper storage conditions, might trigger photochemical reactions that alter pigments or colour compounds present in the leaf powder. This exposure can lead to degradation or breakdown of these compounds, resulting in a lighter appearance of the powder and an increase in the L* value.

Conversely, treatments storage at 4°C with opaque packaging and control (Zero Value) displayed lower L* values, indicating a comparatively reduced lightness in these conditions. Despite exhibiting a degree of variability, the observed differences in lightness between storage at 4°C with opaque packaging and control (Zero Value) were not statistically significant within the tested parameters (p < 0.05). This lack of statistical distinction suggests that the dark packaging at 4°C did not significantly alter the product's colour attributes compared to its initial state control (Zero Value). Authors, [

16] suggested that utilizing dark packaging might shield products from photo-oxidation, potentially aiding in preserving their qualities.

Overall, these findings underscore the substantial impact of packaging transparency and temperature variations on the colour attributes of the product. The significant increase in lightness observed in Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging compared to the other treatments suggests a potential influence of transparent packaging at higher temperatures on the visual perception and potentially the perceived quality of the product. However, further detailed analyses and complementary investigations may be warranted to comprehensively elucidate the underlying mechanisms driving these observed colour alterations and their broader implications for product quality and consumer perception.

2.1.2. Colour Redness (a*)

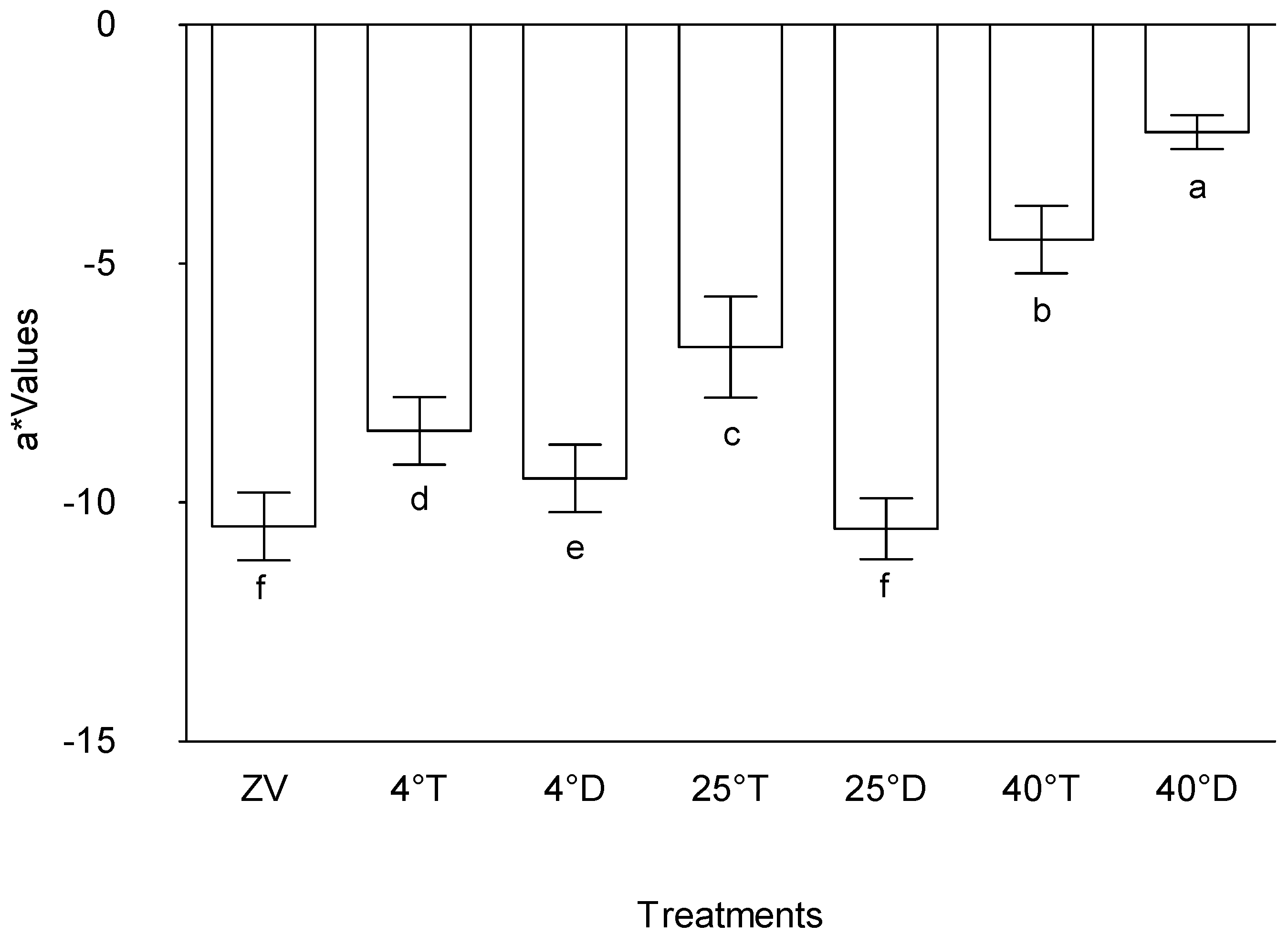

The observed outcomes regarding the "a*" values across the treatments offer valuable insights into the colour attributes influenced by varying experimental conditions (

Figure 3). The significant elevation in "a*" values within treatments Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging and Storage at 40°C with Transparent packaging, when juxtaposed with other treatments, aligns with the notion that these specific conditions—presumably associated with opaque packaging at 40°C and transparent packaging at 40°C—contribute substantially to heightened colour attributes, particularly in the red-green axis.

In comparison to Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging, control (Zero value), Storage at 4°C with opaque, and treatment storage at 25°C with transparent packaging of has a noticeably higher "a*" value. This indicates that, in comparison to the previously described treatments, transparent packaging at 25°C highlights the red-green axis in color characteristics more, highlighting the complex relationship between temperature and packaging transparency and color development.

These results are consistent with earlier studies investigating the impact of packaging and ambient factors on color characteristics. Analogous research has emphasized how temperature variations and the transparency of packing materials influence colour qualities. For example, [

17]'s study supported the patterns seen in treatments Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging and storage at 40°C with transparent packaging by demonstrating the relationship between rising temperatures and an increase in particular color characteristics. Results obtained by [

18] also highlighted the way that transparent packing materials can amplify color features, which is similar to the higher "a*" value that treatment storage at 25°C with transparent packaging showed in comparison to other conditions.

Heat and oxygen during storage encourage chlorophyll colour change in dried leaves [

19]. Chlorophyll in leaves can experience oxidation, hydrolysis, and isomerization after harvest. Chlorophyll's magnesium atom is swapped out for two hydrogen atoms, which causes the colour to shift from brilliant green to olive green [

17]. The observed differences in "a*" values between treatments highlight how temperature and the transparency of the packing material affect particular colour axes, adding to our understanding of how color develops and stabilizes in a variety of product packaging scenarios.

2.1.3. Colour Yellowness (b*)

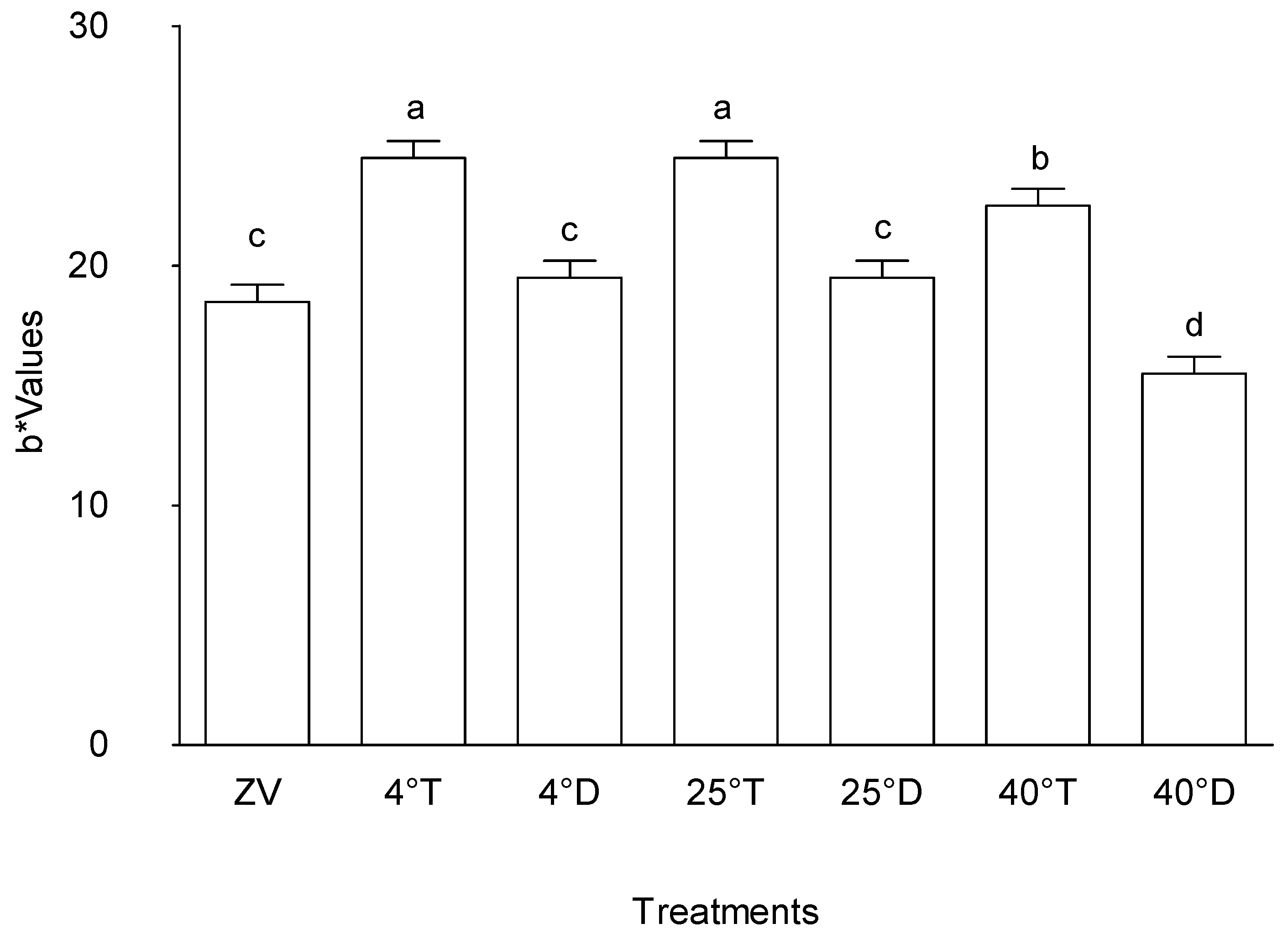

The result of this investigation clearly shows that different treatment circumstances have a significant impact on the "b*" values, which are a crucial parameter that represent the yellow-blue axis within colour characteristics (

Figure 4). The treatments that were examined on storage at 4°C with transparent packaging and storage at 25°C with transparent packaging were found to have the highest "b*" values, indicating a significant increase along the yellow-blue axis. In particular, treatment Storage at 4°C with Transparent packaging was distinguished from the other treatment conditions by exhibiting significantly higher "b*" values, indicating a unique effect on this specific colour quality (p < 0.05).

On the other hand, the powder that was stored at 40°C in a transparent packaging displayed the lowest "b*" value among the conditions that were being studied, indicating a substantial difference from powder stored at 4°C in a transparent packaging, storage at 25°C with transparent packaging, and storage at 40°C with transparent packaging. This distinct divergence indicates a perceptible departure in colour profile and reveals a noteworthy decrease along the yellow-blue axis within its colour features, in contrast to treatments with higher "b*" values (p < 0.05).

These findings are consistent with related research that, although conducted in different settings, looks at how various treatments affect colour qualities. As an example, studies conducted by [

20] who reported that the dried moringa samples had positive b* values, which were considerably higher than those of the fresh sample. This suggests that the samples' colour changed towards the yellow zone.

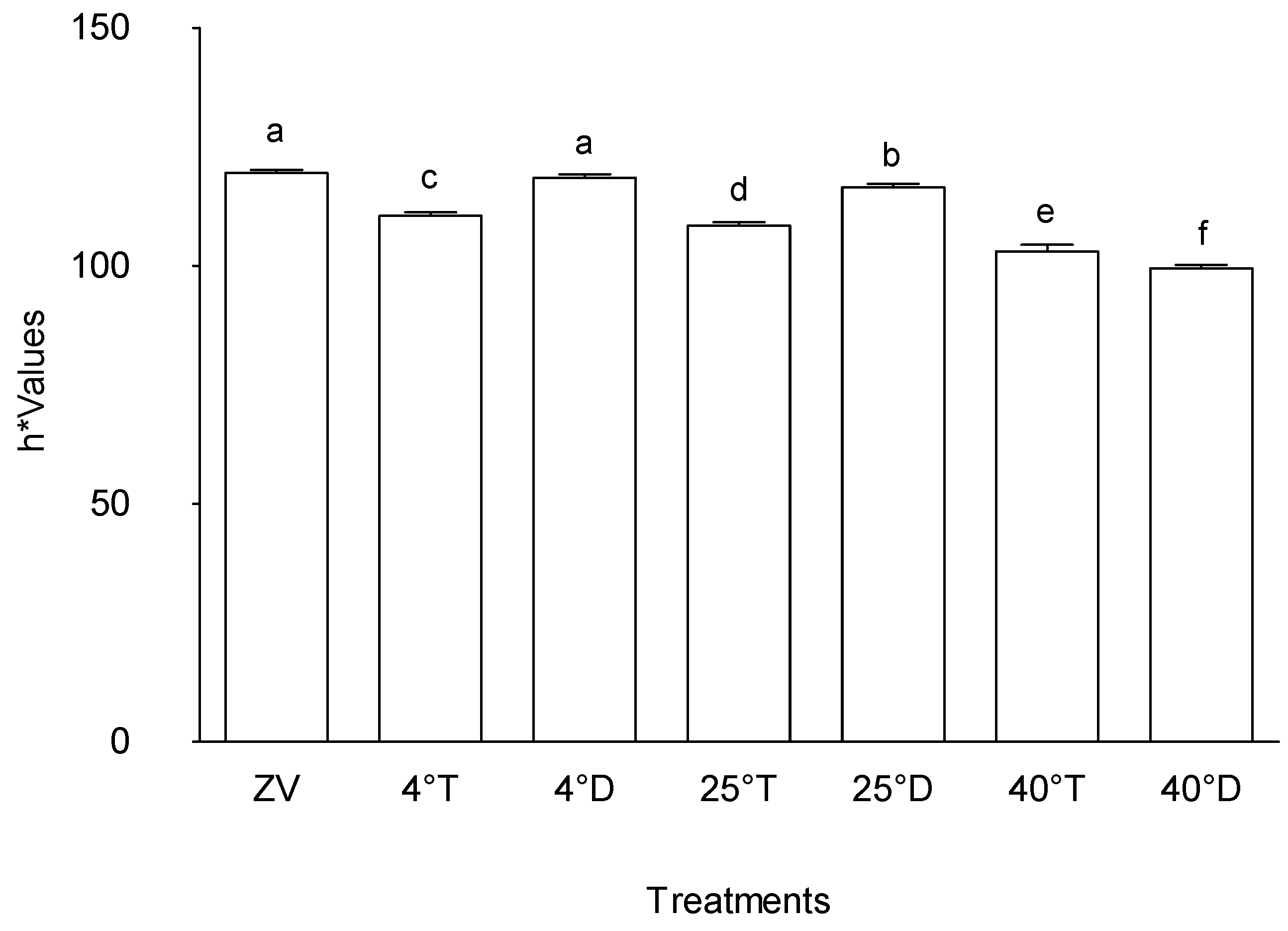

2.1.4. Colour (h*)

Figure 5 indicates distinct trends in the "h*" values among the various treatments, signifying notable differences in colour attributes. Specifically, treatment Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging exhibited the lowest "h*" value among the assessed conditions, followed sequentially by storage at 25°C with transparent packaging, storage at 4°C with transparent packaging, storage at 25°C with opaque packaging, Storage at 4°C with opaque packaging, and the initial baseline, denoted as control (Zero value). In contrast, treatment 40°C in a transparent packaging showcased a higher "h*" value compared to 40°C in opaque packaging, yet it registers lower values relative to storage at 25°C with opaque packaging, storage at 4°C with transparent packaging, storage at 25°C with transparent packaging, storage at 4°C with opaque packaging, and control (Zero value).

This observed hierarchy in "h*" values across treatments underlines the diverse impact of specific storage temperatures and packaging types on colour characteristics. The significantly lower "h*" value in storage at 40°C with opaque packaging suggests a pronounced shift in colour attributes, potentially associated with the elevated storage temperature of 40°C combined with dark packaging. Conversely, treatment Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging demonstrates a relatively higher "h*" value compared to storage at 40°C with opaque packaging, indicating a less intense alteration in colour characteristics, yet still positioned lower compared to several other treatments.

These findings align with comparable studies exploring the influence of storage conditions on colour attributes. Previous research by [

20] has highlighted the subtle differences in colour characteristics linked to particular storage environments, which is consistent with the patterns shown in this study. The current work contributes to this understanding by elucidating the different orders of "h*" values among treatments, hence highlighting the different degrees of colour alteration produced by different combinations of temperature and packaging. This distinction draws attention to the intricate relationship that exists between colour characteristics and storage conditions, providing valuable insight into how to optimise packaging for the intended colour outcomes.

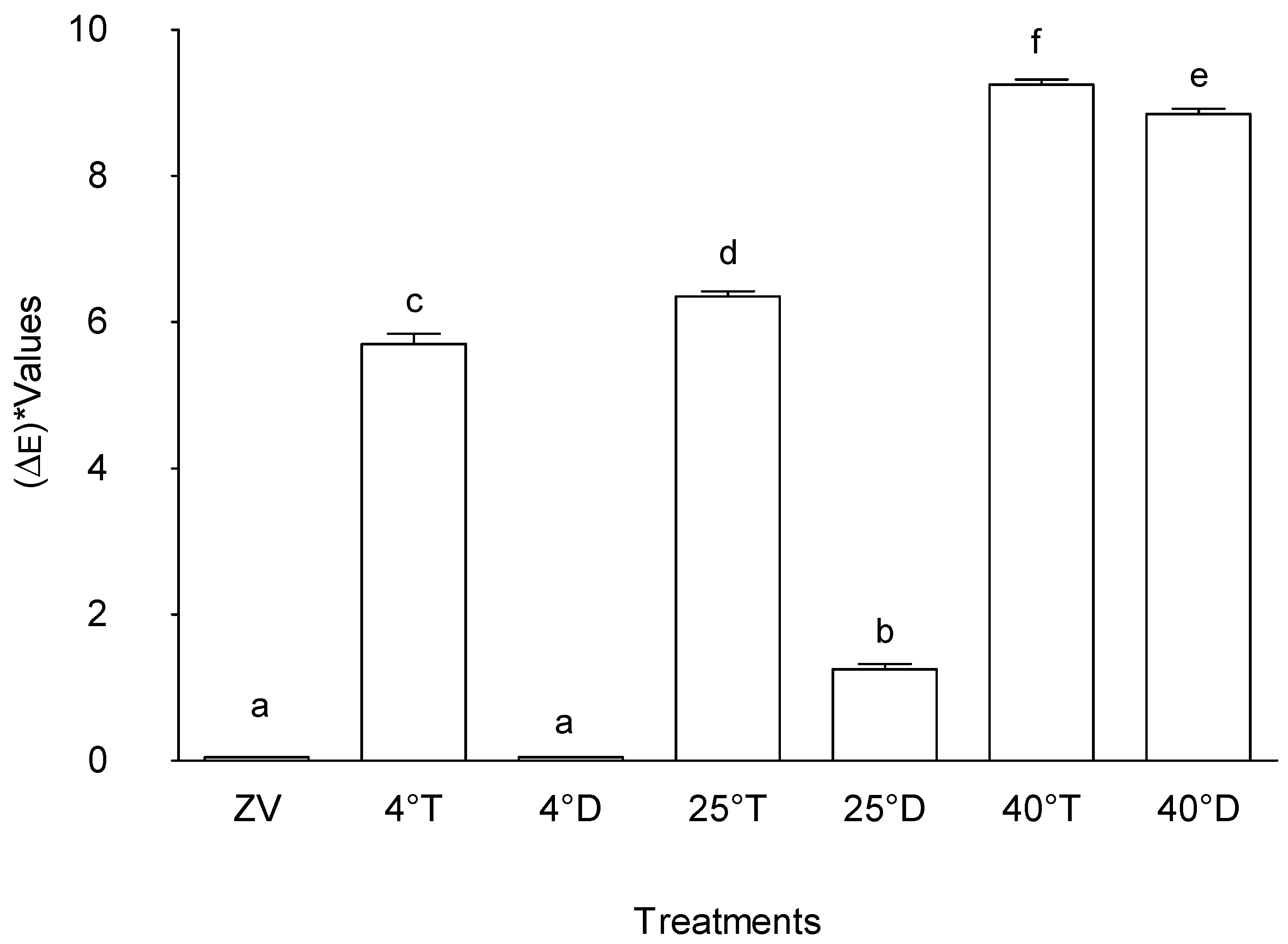

2.1.5. Colour Difference "(ΔE)"

Figure 6 highlights the distinct variations in colour differences ("ΔE") among the different treatments, indicating pronounced disparities in colour attributes. The results depict that samples stored at lower temperatures and in the dark resulted in minimal colour changes. On the other hand, treatment storage at 40°C with transparent packaging exhibited the highest colour difference among all assessed conditions, followed sequentially by storage at 40°C with opaque packaging, Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging, Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging, and storage at 25°C with opaque packaging. In contrast, treatments control (zero value) and storage at 4°C in opaque packaging indicated no discernible changes in colour.

This observed hierarchy in colour differences underscores the diverse impact of specific storage temperatures and packaging types on colour attributes. The significantly elevated "ΔE" value at 40°C with transparent packaging implied a substantial alteration in colour characteristics. Conversely, the absence of colour changes in zero value and 4°C in opaque packaging indicated a consistent colour profile maintained under the respective storage conditions.

Similar trends have been identified in prior studies examining the influence of storage conditions on colour attributes. Research conducted by [

17,

21] has elucidated similar patterns, emphasizing the multifaceted impact of temperature and packaging variations on colour stability within diverse product contexts. Storage-induced alterations in dried leaves facilitate the colour transformation of chlorophyll, a phenomenon accelerated by heat and oxygen exposure [

19]. Chlorophyll in leaves can experience oxidation, hydrolysis, and isomerization after harvest, which causes a change in colour from vivid green to olive green when two hydrogen atoms replace the magnesium atom in chlorophyll [

21]. It has also been observed that increased polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity speeds up chlorophyll deterioration in storage. It has also been observed that increased polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity speeds up chlorophyll deterioration in storage [

22].

By outlining the distinct sequence of color changes among treatments and showing the various degrees of color alteration caused by various combinations of packing and temperature, this study advances the understanding of colour changes in M. oleifera. This sophisticated understanding highlights the complex interactions that occur between colour characteristics and storage circumstances, highlighting the need for specific packaging techniques to regulate and preserve the desired color profiles. To fully understand color stability and preservation in product packaging, more research into the mechanisms driving these color variations is essential.

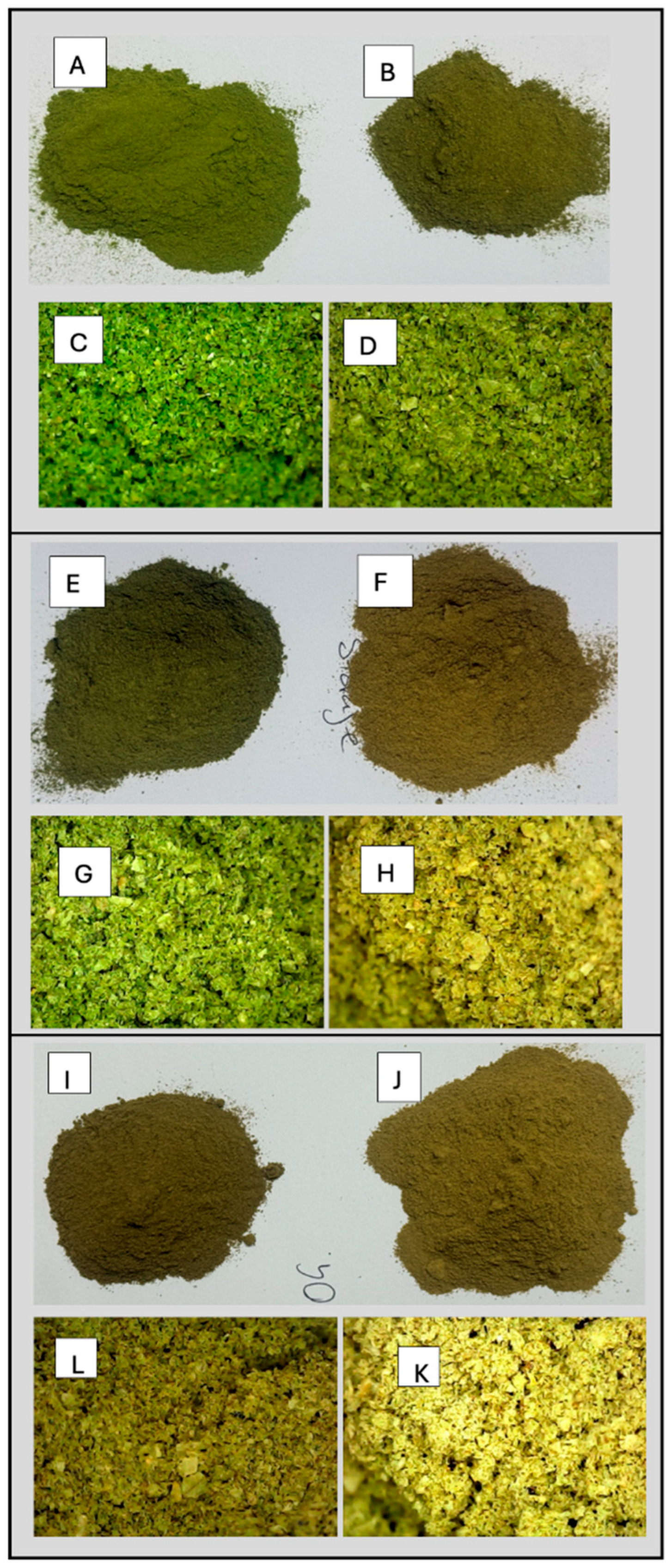

The photographs and microscope images presented in

Figure 7 offer critical insights into the colour changes of the powder obtained through different storage methods. As depicted in

Figure 7, opaque packaging exhibited better color retention, with minimal fading, while higher temperature treatments in transparent packaging resulted in color degradation. Most plant leaves, including

Moringa leaves are rich in β-carotene. The compound is a key contributor to leaf pigmentation and easily degrades at elevated temperatures and light exposure. Hence the transparent packaging combined with exposure to heat had a greater impact on the yellowness of

Moringa leaves than the opaque packaging and lower temperature did.

2.2. Amino Acids

Table 1 provides data on the levels of various amino acids (His, Arg, Ser, Gly, Asp, Glu, Thr, Ala) in M. oleifera leaf samples subjected to different treatments. Amino acid concentrations fluctuated greatly depending on which treatment is given to the M. oleifera leaves. For instance, in comparison to the zero value (the control), treatments of storage at 25°C with opaque packaging, 25°C with transparent packaging, 40°C with opaque packaging, 40°C with transparent packaging, 4°C with opaque packaging, and 4°C with transparent packaging showcased alterations in the concentrations of these amino acids. Notably, certain treatments exhibited distinct trends in specific amino acids compared to others. Treatment storage at 25°C with opaque packaging, for example, demonstrated lower concentrations of several amino acids (His, Arg, Ser, Gly, Asp, Glu, Thr, Ala) in comparison to the control. Conversely, treatments like storage at 40°C with transparent packaging and storage at 4°C with transparent packaging showed elevated concentrations of certain amino acids, indicating potential changes induced by the storage conditions and types of packaging used.

In addition,

Table 1 highlights the concentrations of more various amino acids (Pro, Lys, Tyr, Met, Val, Ile, Leu, Phe) in M. oleifera leaf samples subjected to different treatments, along with their respective mean concentrations ± standard deviation. Compared to the zero value (control), treatments storage at 25°C with opaque packaging, storage at 25°C with transparent packaging, storage at 4°C with opaque packaging, storage at 40°C with transparent packaging, storage at 4°C with opaque packaging, and storage at 4°C with transparent packaging exhibit alterations in the concentrations of the specified amino acids. Each treatment displays distinct patterns in the concentrations of these amino acids relative to others. For instance, treatment storage at 25°C with opaque packaging demonstrated notably lower concentrations of several amino acids (Pro, Lys, Tyr, Met, Val, Ile, Leu, Phe) compared to the control sample. Conversely, treatments like storage at 40°C with transparent packaging and storage at 4°C with transparent packaging displayed increased concentrations of certain amino acids, indicating potential changes influenced by the storage conditions and packaging variations employed.

The changes in amino acid levels highlight how different packaging types (transparent and dark) and storage temperatures (25°C and 40°C) affect the amino acid content of M. oleifera leaves. These changes may have an impact on the functional traits and nutritional qualities linked to M. oleifera ingestion.

The distinct decrease in amino acid concentrations within treatment Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging could be ascribed to several influential factors. Primarily, the storage conditions, encompassing a temperature of 25°C in conjunction with dark packaging, likely fostered an environment that unfavorably impacted amino acid preservation. This is mainly through amino acid depolymerization and Maillard reactions [

23]. This combination potentially led to degradation or breakdown processes, causing a reduction in amino acid concentrations over time. This observation aligns with prior research indicating that extended exposure to elevated temperatures, particularly in the absence of light, may prompt degradation mechanisms that compromise amino acid stability [

24,

25].

Furthermore, the storage setting at 25°C may have prompted oxidative reactions within the leaf samples. Oxidative stress, a consequence of environmental conditions, could instigate the degradation of amino acids, particularly susceptible ones like methionine (Met) and tyrosine (Tyr), thereby resulting in diminished [

26]. This premise aligns with established findings that highlight the susceptibility of certain amino acids to oxidative damage under unfavorable storage conditions.

Moreover, the conducive nature of the dark storage environment, especially when coupled with moderate temperatures, might have facilitated microbial growth or enzymatic activity. This microbial or enzymatic metabolism could have contributed to the breakdown or utilization of amino acids, influencing the observed reduction in concentrations. Chemical interactions between amino acids and other compounds present in the storage milieu might have also transpired, instigating chemical reactions that altered or diminished certain amino acid levels. These interactions underscore the complex interplay of various compounds in storage environments, potentially impacting the stability of amino acids. Lastly, the duration of storage under these conditions likely played a pivotal role. Extended storage periods in suboptimal conditions could exacerbate degradation processes, culminating in the observed reduction in amino acid concentrations.

These theories are consistent with the body of research that has been done on the effects of storage conditions on the stability of amino acids in various matrices. Prior research has demonstrated associations between changes in the amino acid content of various biological samples and temperature, light exposure, oxidative stress, microbial activity, and chemical interactions [

27].

2.3. Microbiological Analysis

Table 2 shows microbial contamination assessments on powdered M. oleifera leaf samples subjected to the different storage conditions and packaging variations. The results indicated the presence and absence of various microorganisms, including E. coli, Salmonella sp., S. aureus, B. cereus, aerobic count, total coliforms, yeasts, and moulds across all treatments, including the control (Zero Value) and those subjected to varying temperatures (4°C, 25°C, 40°C) and packaging types (Opaque and Transparent). There were also variation in the microbial contents depending on the storage conditions. Notably, E. coli, B. cereus and Salmonella sp. were absent in all samples, suggesting the high level of hygenic practices during the preparation of the samples tested before and during storage. This observation indicated the safe use of the powder as these organisms were in the acceptable thresholds for food products.

Based on the results (

Table 2), there were variations in the Aerobic count (AC), Total coliforms (TC) and yeast and mold (Y&m) for all the storage conditions with CFU/mL, slightly increasing as the temperature increase. From a food safety standpoint, the AC, TC and Y&m counts for all the samples were below the limit set by South African National standard (SANS1683:2015) Moringa Standard requirements.

Previous studies have indicated that M. oleifera possesses natural antimicrobial properties due to certain bioactive compounds [

28]. However, despite these inherent properties, the microbial load observed in this study suggested that certain bacterial populations remained unaffected by the storage conditions and packaging variations studied. This implied the need for more rigorous processing or storage protocols to address these specific microbial populations, especially AC and TC, to ensure enhanced safety and quality of M. oleifera leaf products. For example, [

29] observed that glass material kept colour the best and was less prone to microbial permeability. Further investigations into the persistence of these bacteria despite storage conditions might aid in developing more effective preservation strategies for M. oleifera leaf products.

Although the results revealed that the storage conditions of M. oleifera leaf powder resulted in microbial counts below the SANS1683:2025 limit for Moringa, further isolation is recommended for colonies on the AC, TC and Y&m for future studies on species-specific determination of these contaminants.

2.4. Phytochemicals

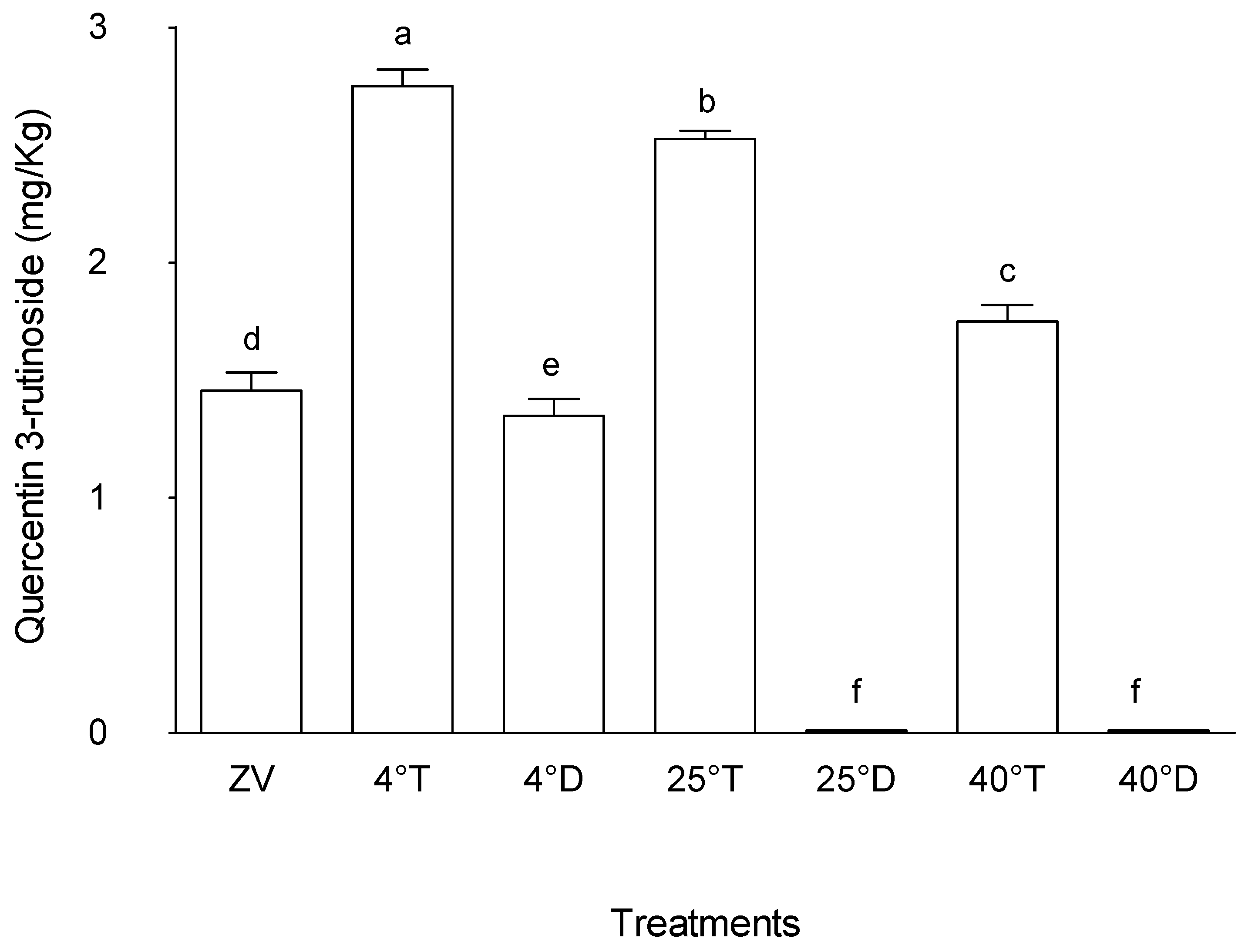

2.4.1. Quercetin-3-Rutinoside

Figure 8 shows that treatment at 4°C in a transparent packaging had the highest quercetin 3-rutinoside level in the grounded and stored

M. oleifera leaves, with a mean value of 2.8 µg/g, showing statistical significance (p < 0.05) compared to the other treatments. This was followed by treatment at 25°C in a transparent package, which displayed a mean value of 2.46 µg/g, also significantly different from other treatments (p < 0.05). In contrast, treatments in the opaque packaging at all the three-storage temperature (4°C, 25°C, 40°C) exhibited lower levels of quercetin 3-rutinoside, with mean values of 0, 0, and 1.2 µg/g, respectively. The lower values of quercetin 3-rutinoside in opaque packaging suggest some form of impact of light during storage conditions on the preservation or degradation of this compound in

M. oleifera leaves.

The Zero value, representing the initial state of quercetin 3-rutinoside concentration in

M. oleifera leaves before storage, showed an intermediate value of 1.23 µg/g. These findings underscore the possible biochemical activities that may continue despite the storage of plant material and in this particular case, either accumulation or biosynthesis of quercetin 3-rutinoside in powdered

M. oleifera leaves. Treatments subjected to transparent packaging allowing light tended to exhibit significantly higher concentrations, while those stored under opaque with no light displayed lower levels. This suggests some compounds biosynthesis are influenced by factors like light exposure or temperature fluctuations [

30].

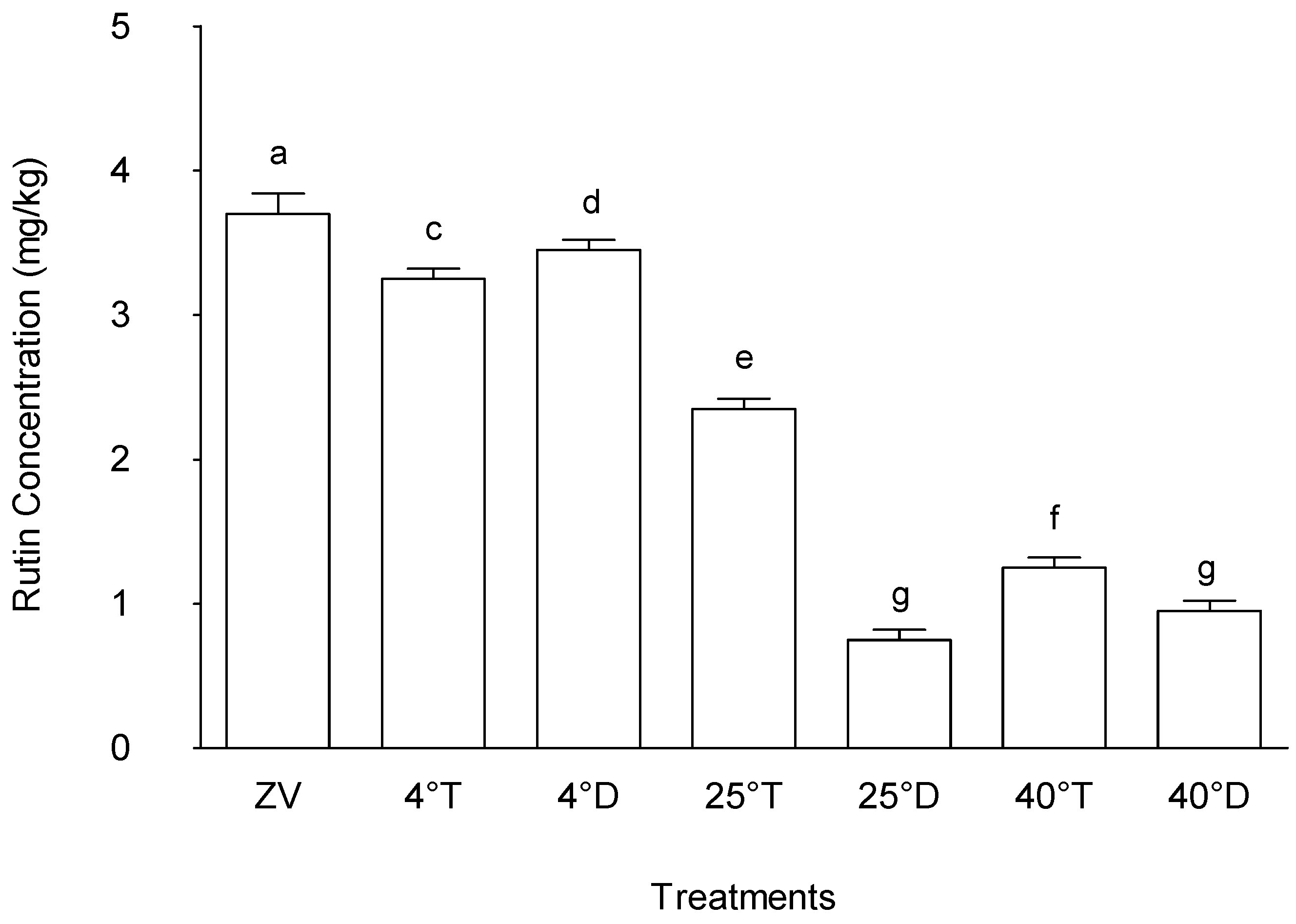

2.4.2. Rutin

While quercetin 3-rutinoside concentration in powdered M. oleifera leaves during storage was affected by light conditions, the concentration of rutin varied according to temperature. The treatment that exhibited the highest rutin concentration amongst the treatments was the control (zero value), representing the initial Rutin concentration before storage, with a mean value of 3.76 µg/g (

Figure 9). Following this, treatments storage at 4°C in both opaque packaging and transparent packaging exhibited rutin concentrations, with mean values of 3.34 µg/g and 3.19 µg/g, respectively, both significantly higher compared to other treatments (p < 0.05). These findings suggest that storage conditions at lower temperature, regardless of packaging type, notably preserved the rutin content in powdered M. oleifera leaves.

A decrease in the rutin concentration was observed in treatment at 25°C with transparent packaging (mean value of 2.27 µg/g) compared to the treatment at 25°C with opaque packaging (0.78 µg/g). Notable differences were also observed at 40°C with opaque packaging versus the transparent packages, with the amounts being slightly higher in the later than the former.

The results highlight the significant influence of storage conditions on rutin concentrations in M. oleifera leaves, with cooler storage conditions, specifically at 4°C, demonstrating the highest preservation potential. These findings are consistent with other studies that have shown the impact of temperature on the stability and preservation of bioactive compounds in M. oleifera leaves. For instance, [

31] observed that rutin content decreased at higher temperatures of up to 35 °C compared to storage at 4 °C. According to the authors, after two months at 4 °C, the rutin content did not significantly change. In contrast, the rutin contents were comparatively steady for two weeks at 25 °C and 35 °C before declining in the third week [

31].

Rutin, a flavonoid glycoside found in plants, can degrade, or lose concentration when stored at high temperatures, due to several reasons. First, rutin is heat sensitive and can break down in high storage temperatures [

32]. Second, elevated temperatures have the potential to induce oxidative stress in plant tissues. Rutin, an antioxidant molecule, may degrade in an effort to counteract free radicals produced in such stress situations [

32]. Thirdly, the enzymes that break down rutin may become more active at higher temperatures [

32]. The current findings underscore the importance of controlled storage conditions, particularly lower temperatures, in preserving the bioactive compounds in M. oleifera leaves, such as rutin.

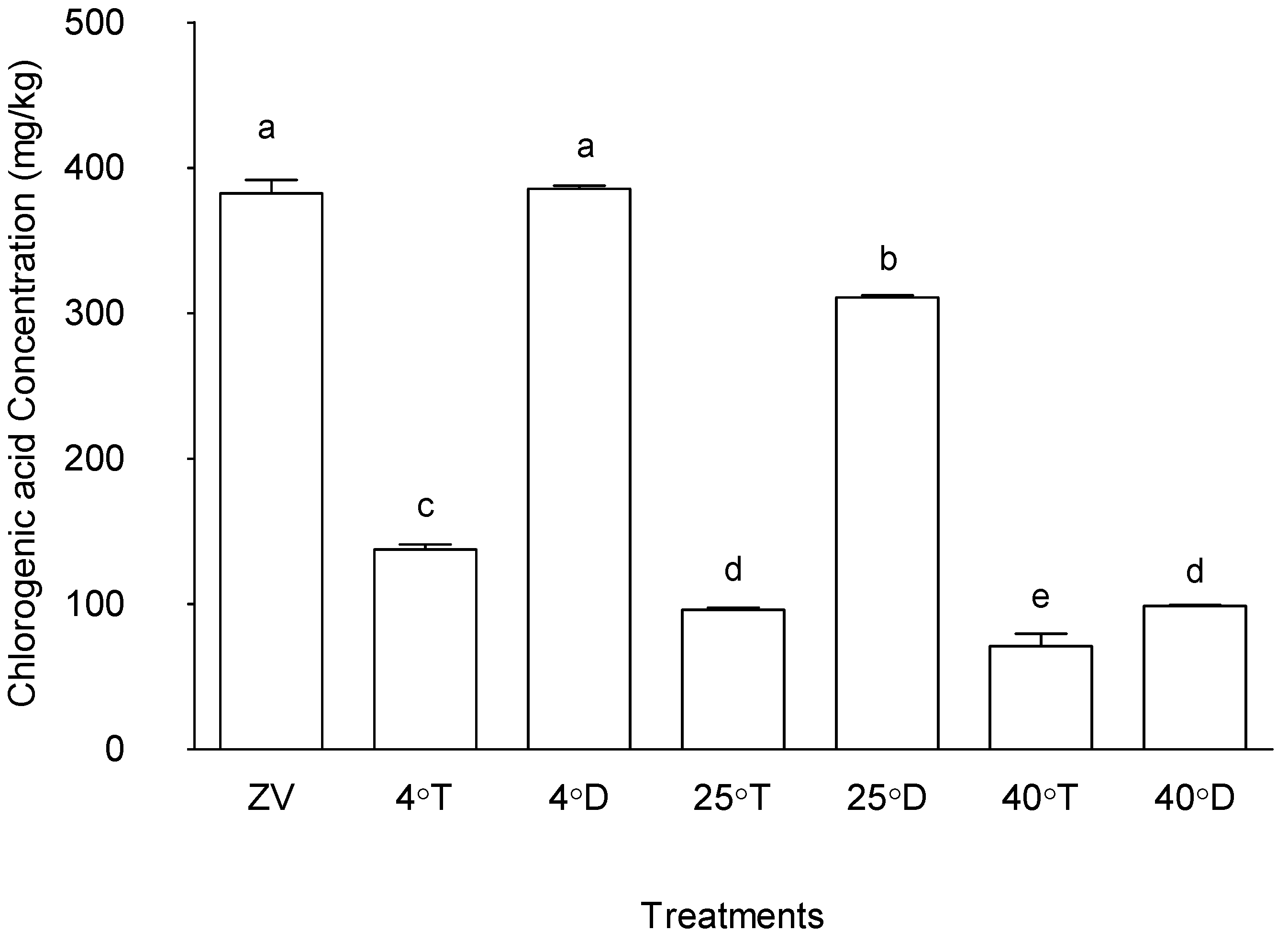

2.4.3. Chlorogenic Acid

The effect of storage on the chlorogenic acid concentration is presented in

Figure 10. Storage at 4°C with opaque packaging and the control (zero value), with mean values of 393.26 µg/g and 396.17 µg/g, respectively, indicating no significant difference between these two treatments (p > 0.05). Following this, treatment storage at 25°C with opaque packaging exhibited a relatively high chlorogenic acid concentration (mean value of 306.67 µg/g) compared to other treatments (p < 0.05). Conversely, 40°C with opaque packaging exhibited lower chlorogenic acid concentration, threefold lower than the other opaque storage temperature conditions. All the samples in transparent packaging had threefold lower chlorogenic acid concentrations. These findings suggest that storage conditions lower to ambient temperatures in opaque packages notably preserved chlorogenic acid content in M. oleifera powdered leaves.

These outcomes underscore the significant influence of storage conditions on chlorogenic acid concentrations in M. oleifera leaves. Previous studies have demonstrated that chlorogenic acid, found in M. oleifera has anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, and antioxidant qualities [

33]. Therefore, the preservation of chlorogenic acid content in M. oleifera leaves 10is important for maintaining its potential health benefits during storage.

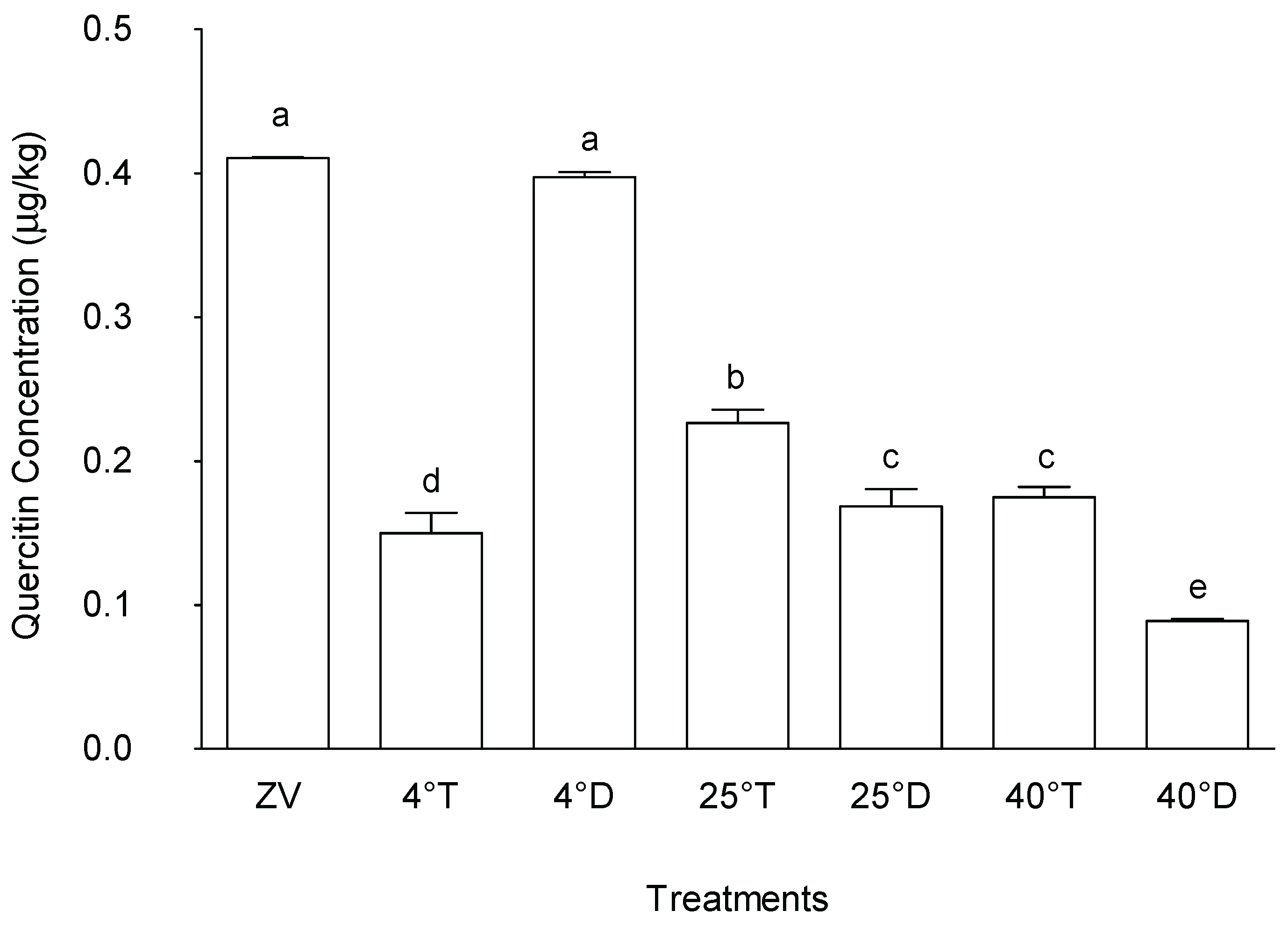

2.4.4. Quercitrin

A similar trend to the behavior observed for chlorogenic acid was also observed for quercitrin concentrations. The observed quercetin concentrations in M. oleifera leaves under various storage conditions showed notable differences among treatments (

Figure 11). Treatment stored at 4°C in opaque packaging and the control (zero value) exhibited the highest quercitrin concentrations, with a mean value of 400.4 µg/g and 397.3 µg/g, respectively. These were significantly higher than all other treatments. Conversely, treatments Storage at in transparent packaging at all temperatures as well as 25°C and 40 °C in opaque packaging showed lower quercitrin concentrations. These treatments demonstrated comparatively reduced levels of quercitrin compared to the storage at 4°C in an opaque packaging.

The significant perseveration of quercitrin concentrations observed in the storage at 4°C with opaque packaging treatments suggests that these storage conditions may be beneficial for maintaining its concentrations during storage of M. oleifera leaves, hence preserving the plant leaf medicinal and antioxidant properties attributed to quercetin. [

34] reported that quercitrin was prone to deterioration when exposed to light. Because quercitrin degrades easily when exposed to light, it is crucial to store plant-based products under ideal circumstances to prevent this degradation and maintain their quality.

These advancements in food preservation and processing align with the broader objective of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2: Zero Hunger by 2030. By improving the nutritional quality and shelf life of food products, reducing post-harvest losses, and supporting sustainable agricultural practices, these techniques can contribute to improved food security and nutrition worldwide.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material

Moringa oleifera Lam. (Cultivar PKM1) fresh leaves were harvested and collected from the university orchard situated within the University of Limpopo in Limpopo Province, South Africa (coordinates: 23.8888° S, 29.7386° E). The first procedure entailed thoroughly cleaning and rinsing the fresh leaves with running deionized water. Following that, the leaves were defoliated, drained, and dried in an ambient room environment. The dried leaf materials were milled and sieved to generate a finely powdered form with particle sizes of 0.5 mm. The powdered substance was subjected to extensive testing to determine its colour attributes, phytochemical content, amino acids and microbial contamination. This examination was performed initially and then again after 12-months of storage period to evaluate potential changes over time.

3.2. Experimental Design and Treatments

The experimental design used was a Randomized Complete Design (RCD) done in chambers with controlled temperature and environment to systematically assess the impact of various temperature storage conditions (4°C, 25°C, and 40°C) and packaging types (opaque and transparent) on the colour attributes, phytochemical content, amino acids and microbial contamination of the samples. The samples were 6 replicates per treatment at each storage temperature.

The trial layout was structured to accommodate three temperature storage conditions and two distinct packaging types, as follows: 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging.

Additionally, the control sample, referred to as Zero value (ZV) served as the baseline and was tested before the commencement of the storage period. Subsequent to the baseline assessment, the remaining samples underwent storage for a duration of 12 months under the designated temperature and packaging conditions. After the stipulated storage periods, the samples were subjected to testing to evaluate the alterations in their colour attributes, phenolic composition, and nutritional variation over time.

Photographs of the packaging material and the powder samples were taken using a Digital Canon D60 Camera, QY-X03 HD colour High resolution Digital Microscope (Andowl, China) and a

3.3. Colour Measurement

The colour was measured using a Minolta Leaf CR-400 chromameter in Minolta, Osaka, Japan; the instrument had been calibrated by white tiles. The L* (lightness), colour coordinate (a*) was related to the red and green colours where it had a positive or negative value (b*) values were determined and the total colour difference (ΔE) was calculated using the formulae described by [

35] previously. In the CIE colour system, negative a* colour coordinate and the positive b* colour coordinate describe the intensity of green and the yellow colour respectively.

where L1*, a1*, b1* are day 0 values. L2*, a2*, and b2* are the values of the sample treatments. Measurements were taken at three points per replicate. Altogether colour readings were recorded from two replicate samples per treatment.

Colour measurements were obtained for various M. oleifera packaging treatments, including temperature (4°C, 25°C or 40°C) and packaging type (Dark or Transparent). The "Zero Value" served as the reference for colour comparison. Means and standard errors (SE) were calculated for each treatment group within the colour parameters (L*, a*, b*, h*). Delta E (ΔE) values were computed to quantify colour differences relative to the "Zero Value." ΔE is a measure of how different the colour of each treatment is from the reference. Smaller ΔE values indicated closer colour matches, while larger values indicated greater colour differences.

3.4. Amino Acids Determination

The oven was set at 110°C temperature, the (protein/freeze dried tissue) was added to a suitable glass sample vial. Then hydrochloric acid (6N HCl) was added to the vials containing the sample- between 0.3 - 1.0 mL. Samples were vortexed to make sure that all the sample material is submerged in the acid. The tubes were flushed with argon or nitrogen gas to eliminate oxygen the tubes ware closed with the lids. Vials were placed in the oven, and after 5-10 min tighten the lids. The vials were left in the oven at 110°C for 18 - 24 hours. The vials were taken out of the oven then cooled. The hydrolysate was filtered using centrifuge tube filters (Corning® Costar® Spin-X tubes). The filtrate was transferred to Eppendorf tubes and dried down using a speed vac. Reconstituted in borate buffer to be ready for derivatization.

3.4.1. Derivatization Procedure

Sample dilutions were performed in 2ml Eppendorf tubes, and 10µl of diluted sample was then used during the derivatization. Borate buffer of 70 µl was transferred into a 200 µl glass and inserted in a 2ml glass vial. Then 10 µl diluted sample/standard solution was added thereafter. 20 µl AQC reagent was also added. The vials were vortexed for proper mixing. Then vials were place into an oven/heating mantle at 55 °C and heat for 10 minutes. After 10 minutes the vials were ready for analysis and can were loaded into the autosampler tray.

3.5. Determination of Microbial Contamination

The M. oleifera leaf powder samples were subjected to dilution series to obtain various dilutions in which 1g dissolved in 5 mL sterile distilled water. Dilution of each sample with aliquots were plated on agar plates. Colonies were counted using the Semi-automatic digital device The microbial population was quantified in terms of bacterial count per millilitre (CFU/ml).

3.5.1. Sample Dilution

The initial dilution was prepared by adding 1 ml of the sample to a 99 ml sterile saline solution, making a 1/100 (or 10-2) dilution. Bacteria was dispersed by mixing the dilution vigorously to dissolve any aggregates. With, 1 ml from the 10-2 dilution was moved to a second 99 ml saline solution, creating a 10-4 dilution. This procedure was continued until a 10-8 dilution was obtained.

3.5.2. Plating and Incubation

One petri dish received 1 ml of each dilution sample, while another received 0.1 ml. Nutrient agar was heated at temperature of between 48-50°C in a water bath which was then thoroughly blended to encourage bacterial growth for E. coli and total coliforms the samples. The presence of Salmonella in the samples was determined using the Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate (XLD) agar. To promote microbial growth was promoted by heating the plates and turning the oven at ,25°C for 48 hours.

3.5.3. Colony Counting

The treatment samples analysed were 6 replicates per packaging at each storage temperature. Therefore, the total samples were 36 plus the 6 analysed as baseline results to give 42 samples. The petri plates with 30 to 300 colonies were taken for counting after incubation. Plates with more than 300 colonies were deemed too many for an accurate count, while plates with fewer than 30 colonies were deemed insufficient for a reliable statistical analysis. An automated colony counter was used to count the colonies on each plate (ZR-1101). The following equation was used to calculate:

Number of bacteria (CFUs) = Dilution × Number of colonies on plate

3.6. Phenolic Variations

A 50 ml centrifuge tube with screwcap was used to accurately weigh the 2 g sample. 15ml of 50% methanol/1% formic acid was added and the tubes tightly capped. After that, the samples were centrifuged for 1 minute and then they were extracted in a vacuum bath for an additional hour. After 5 minutes, the 2 ml sample was taken and centrifuged at 14,000 revolutions per minute. The clear supernatant was then transferred into 1.5 ml glass vials for analysis.

A Waters Synapt G2 Quadrupole time-of-flight (QTOF) mass spectrometer (MS) connected to a Waters Acquity ultra-performance liquid chromatograph (UPLC) (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was used for high-resolution UPLC-MS analysis. Before entering the mass spectrometer, Column eluate went through a Photodiode Array PNPDA detector and was able to simultaneously obtain UV and MS spectral data. In negative mode, with a cone voltage of 15 V, desolvation temperature of 275 C, desolvation gas at 650 Lph and the rest of the MS settings optimized for best resolution and sensitivity, an electrospray ionization device has been used. Data were acquired by scanning from m/z 150 to 1500 m/z in resolution mode as well as in MSE mode. In MSE mode two channels of MS data were acquired, one at a low collision energy (4 V) and the second using a collision energy ramp (40−100 V) to obtain fragmentation data as well. For accurate mass determination, leucine enkaphalin has been used as a lock reference mass and the instrument is calibrated in sodium format. Separation was achieved on a Waters HSS T3, 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm column. The injection volume was 2 L, and the mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic solvent A and Acetonitrile which contained 0.1 % Formic acid as solvents B. For 1 minute, the gradient started at 100% solvent A and gradually increased to 28% B over 22 minutes in a linear manner. The flow rate was set at 0.3 mL per minute and the column temperature was maintained at 55 C. The compound was quantified relative to the calibration curve set by injecting a range of catechin standards between 0.5 and 100 mg per litre for catechin.

Data was processed using MSDIAL and MSFINDER (RIKEN Canter for Sustainable Resource Science: Metabolome Informatics Research Team, Kanagawa, Japan

4. Conclusions

Based on the results and objectives outlined in the current study, the following conclusions can be drawn. The storage temperature significantly influences the quality parameters of M. oleifera leaf powder. Variations in temperature conditions (4°C, 25°C, 40°C) led to notable changes in phytochemical content, microbial activity, and nutritional properties over the 12-month storage period. Different storage material exhibited varying impacts on the phytochemical profiles, with higher temperatures and transparent bags showed more pronounced degradation in bioactive compounds and increased microbial activity compared to lower temperatures. Lower temperatures (4°C) in opaque bags tend to better preserve the phytochemical constituents and nutritional attributes of M. oleifera leaf powder. This information serves as a valuable resource for stakeholders involved in the production, distribution, and consumption of this beneficial plant product.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.N. and S.L.L.; methodology, A.R.N., T.G.N., R.M., S.L.L.; software, A.R.N.; validation, A.R.N., T.G.N., R.M. and S.L.L.; formal analysis, T.G.N. and R.M.; investigation, T.G.N. and R.M.; resources, A.R.N. and S.L.L.; data curation, A.R.N. and S.L.L; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.N. and T.G.N.; writing—review and editing A.R.N., T.G.N., R.M., S.L.L.; visualization, A.R.N., T.G.N., R.M., S.L.L; supervision, A.R.N., R.M., S.L.L.; project administration, A.R.N., S.L.L.; funding acquisition, A.R.N., S.L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Department of Science and Innovation, Pretoria (South African Government), grant number DSI-IKS DSI/CON C2235/2021.

Data Availability Statement

The research data is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding from the Directorate of the Indigenous Knowledge-based Tech Innovation in the Department of Science and Innovation, Pretoria and National Research Foundation, Pretoria.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Schippmann, U.; Leaman, D.J.; Cunningham, A.B. Impact of cultivation and gathering of medicinal plants on biodiversity: Global trends and issues. Biodiversity and the Ecosystem Approach in Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, 2002.

- Pandey, A.K. Harvesting and post-harvest processing of medicinal plants: Problems and prospects. 2017.

- Ekor, M. The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 4, 177. [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.K. Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants, Vol. 1; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 285–292.

- Mishra, S.P.; Singh, P.; Singh, S. Processing of Moringa oleifera leaves for human consumption. Bull. Environ. Pharmacol. Life Sci. 2012, 2, 1–5.

- Dania, S.O.; Akpansubi, P.; Eghagara, O.O. Comparative effects of different fertilizer sources on the growth and nutrient content of moringa (Moringa oleifera) seedling in a greenhouse trial. Adv. Agric. 2014, Article ID 726313. [CrossRef]

- Fahey, J.W. Moringa oleifera: A review of the medical evidence for its nutritional, therapeutic and prophylactic properties. Trees Life J. 2005, 1, 1–15.

- Ndhlala, A.R.; Tshabalala, T. Diversity in the Nutritional Values of Some Moringa oleifera Lam. Cultivars. Diversity 2023, 15, 834.

- Grubben, G.J.H.; Denton, O.A. Plant Resources of Tropical Africa 2. Vegetables; PROTA Foundation: Wageningen, Netherlands; Backhuys Publishers: Leiden, Netherlands; CTA: Wageningen, Netherlands, 2004; pp. 1–688.

- Doerr, B.; Cameron, L. Moringa Leaf Powder. ECHO Technical Note #51; 2005. Available online: https://www.echocommunity.org/en/resources/ed7fb90d-e49a-438d-89dc-01e22f3fa124.

- Mensah, M. Effect of different packaging materials on the quality and shelf life of Moringa oleifera leaf powder during storage. Master’s Thesis, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, 2011.

- Rico, D.; Martin-Diana, A.B.; Barat, J.M.; Barry-Ryan, C. Extending and measuring the quality of fresh-cut fruit and vegetables: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 18, 373–386. [CrossRef]

- Peter, K.V. Handbook of Herbs and Spices, Vol. 3; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006.

- Mayuoni-Kirshinbaum, L.; Daus, A.; Porat, R. Changes in sensory quality and aroma volatile composition during prolonged storage of ‘Wonderful’ pomegranate fruit. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 1569–1578. [CrossRef]

- Haile, D.M.; De Smet, S.; Claeys, E.; Vossen, E. Effect of light, packaging condition and dark storage durations on colour and lipid oxidative stability of cooked ham. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 50, 239–247. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Duncan, S.E.; Whalley, N.W.; O'Keefe, S.F. Interaction effect of LED colour temperatures and light-protective additive packaging on photo-oxidation in milk displayed in retail dairy case. Food Chem. 2020, 323, 126699. [CrossRef]

- Phahom, T.; Kerr, W.L.; Pegg, R.B.; Phoungchandang, S. Effect of packaging types and storage conditions on quality aspects of dried Thunbergia laurifolia leaves and degradation kinetics of bioactive compounds. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 4405–4415. [CrossRef]

- Krah, C.Y.; Krisnadi, D. Effect of Harvest and Postharvest Handling on Quality of Moringa Leaf Powder. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1038, 012074.

- Meyer, L.H. Food Chemistry; Affiliated East-West Press Pvt Ltd: New Delhi, India, 1973.

- Hasizah, A.; Salengke, S.; Djalal, M.; Arifin, A.S.; Mochtar, A.A. Color change and chlorophyll degradation during fluidized bed drying of Moringa oleifera leaves. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2871, 030007.

- Ahad, T.; Gull, A.; Nissar, J.; Masoodi, L.; Rather, A. Effect of storage temperatures, packaging materials and storage periods on antioxidant activity and non-enzymatic browning of antioxidant treated walnut kernels. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 3556–3563. [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Zhou, H.-M.; Zhu, K.-X.; Guo, X.-N.; Peng, W. Physicochemical changes in the discoloration of dried green tea noodles caused by polyphenol oxidase from wheat flour. LWT 2020, 130, 109614. [CrossRef]

- Šopík, T.; Lazárková, Z.; Salek, R.N.; Talár, J.; Purevdorj, K.; Buňková, L.; Foltin, P.; Jančová, P.; Novotný, M.; Gál, R. Changes in the quality attributes of selected long-life food at four different temperatures over prolonged storage. Foods 2022, 11, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Östbring, K.; Sjöholm, I.; Rayner, M.; Erlanson-Albertsson, C. Effects of storage conditions on degradation of chlorophyll and emulsifying capacity of thylakoid powders produced by different drying methods. Foods 2020, 9, 669. [CrossRef]

- Schnellbaecher, A.; Lindig, A.; Le Mignon, M.; Hofmann, T.; Pardon, B.; Bellmaine, S.; Zimmer, A. Degradation products of tryptophan in cell culture media: Contribution to color and toxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6221. [CrossRef]

- Andrés, C.M.C.; Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Andrés Juan, C.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. Impact of reactive species on amino acids—Biological relevance in proteins and induced pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14049. [CrossRef]

- Kashef, N.; Hamblin, M.R. Can microbial cells develop resistance to oxidative stress in antimicrobial photodynamic inactivation? Drug Resist. Updat. 2017, 31, 31–42. [CrossRef]

- Tshabalala, T.; Ndhlala, A.R.; Ncube, B.; Abdelgadir, H.A.; Van Staden, J. Potential substitution of the root with the leaf in the use of Moringa oleifera for antimicrobial, antidiabetic and antioxidant properties. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 129, 106–112. [CrossRef]

- Olorode, O.; Bamgbose, A.; Raji, O. Effect of blanching and packaging material on the colour and microbial load of ben oil (Moringa oleifera) leaf powder. Outlook 2015 World Association for Sustainable Development Conference Proceedings, 2015, pp. 311–320.

- Potisate, Y.; Kerr, W.L.; Phoungchandang, S. Changes during storage of dried Moringa oleifera leaves prepared by heat pump-assisted dehumidified air drying. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 1224–1233.

- Kim, J.M.; Kang, J.Y.; Park, S.K.; Han, H.J.; Lee, K.-Y.; Kim, A.-N.; Kim, J.C.; Choi, S.-G.; Heo, H.J. Effect of storage temperature on the antioxidant activity and catechins stability of Matcha (Camellia sinensis). Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 1261–1271. [CrossRef]

- Donkor, A.; Nashirudeen, Y.; Suurbaar, J. Stability evaluation and degradation kinetics of rutin in Ficus pumila leaves formulated with oil extracted from Moringa oleifera seeds. J. Anal. Pharm. Res. 2016, 3, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Coz-Bolaños, X.; Campos-Vega, R.; Reynoso-Camacho, R.; Ramos-Gómez, M.; Loarca-Piña, G.F.; Guzmán-Maldonado, S. Moringa Infusion (Moringa oleifera) Rich in Phenolic Compounds and High Antioxidant Capacity Attenuate Nitric Oxide Pro-Inflammatory Mediator In Vitro. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 118, 95–101. [CrossRef]

- Chaaban, H.; Ioannou, I.; Paris, C.; Charbonnel, C.; Ghoul, M. The Photostability of Flavanones, Flavonols and Flavones and Evolution of Their Antioxidant Activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2017, 336, 131–139. [CrossRef]

- Managa, M.G.; Remize, F.; Garcia, C.; Sivakumar, D. Effect of Moist Cooking Blanching on Colour, Phenolic Metabolites and Glucosinolate Content in Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa L. subsp. chinensis). Foods 2019, 8, 399.

Figure 1.

Packaging types used to store Moringa oleifera leaf powder. A- transparent packaging; B - opaque packaging.

Figure 1.

Packaging types used to store Moringa oleifera leaf powder. A- transparent packaging; B - opaque packaging.

Figure 2.

Effect of packaging and temperature treatment on lightness L* colour values in Moringa oleifera leaf powder. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 2.

Effect of packaging and temperature treatment on lightness L* colour values in Moringa oleifera leaf powder. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 3.

Effect of packaging and temperature treatment on a* colour values in Moringa oleifera leaf powder. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 3.

Effect of packaging and temperature treatment on a* colour values in Moringa oleifera leaf powder. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 4.

Effect of packaging and temperature treatment on b* colour values in Moringa oleifera leaf powder. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 4.

Effect of packaging and temperature treatment on b* colour values in Moringa oleifera leaf powder. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 5.

Effect of packaging and temperature treatment on h* colour values in Moringa oleifera leaf powder. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 5.

Effect of packaging and temperature treatment on h* colour values in Moringa oleifera leaf powder. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 6.

Effect of packaging and temperature treatment on Colour difference (ΔE) values in Moringa oleifera leaf powder. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 6.

Effect of packaging and temperature treatment on Colour difference (ΔE) values in Moringa oleifera leaf powder. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 7.

Effect of packaging and temperature treatment on colour in Moringa oleifera leaf powder as viewed and photographed using a Digital Canon EOS D70 15-135 mm lens Camera (EOSD70) and QY-X03 HD colour High resolution Digital Microscope (HDHRM). A- D material storage at 4°C [A- opaque packaging (EOSD70); B- transparent packaging (EOSD70); C- opaque packaging (HDHRM); D - transparent packaging (HDHRM)]. E-H material storage at 25°C [E - opaque packaging (EOSD70); F - transparent packaging (EOSD70); G - opaque packaging (HDHRM); H - transparent packaging (HDHRM)]. I-K material storage at 40°C [I - opaque packaging (EOSD70); J - transparent packaging (EOSD70); K - opaque packaging (HDHRM); L - transparent packaging (HDHRM)].

Figure 7.

Effect of packaging and temperature treatment on colour in Moringa oleifera leaf powder as viewed and photographed using a Digital Canon EOS D70 15-135 mm lens Camera (EOSD70) and QY-X03 HD colour High resolution Digital Microscope (HDHRM). A- D material storage at 4°C [A- opaque packaging (EOSD70); B- transparent packaging (EOSD70); C- opaque packaging (HDHRM); D - transparent packaging (HDHRM)]. E-H material storage at 25°C [E - opaque packaging (EOSD70); F - transparent packaging (EOSD70); G - opaque packaging (HDHRM); H - transparent packaging (HDHRM)]. I-K material storage at 40°C [I - opaque packaging (EOSD70); J - transparent packaging (EOSD70); K - opaque packaging (HDHRM); L - transparent packaging (HDHRM)].

Figure 8.

Effect of different storage conditions on quercetin-3-rutinoside concentration in Moringa oleifera leaves. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 8.

Effect of different storage conditions on quercetin-3-rutinoside concentration in Moringa oleifera leaves. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 9.

Effect of different storage conditions on quercetin-3-rutinoside concentration in Moringa oleifera leaves. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 9.

Effect of different storage conditions on quercetin-3-rutinoside concentration in Moringa oleifera leaves. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 10.

Effect of different storage conditions on chlorogenic acid concentration in Moringa oleifera leaves. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 10.

Effect of different storage conditions on chlorogenic acid concentration in Moringa oleifera leaves. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 11.

Effect of different storage conditions on quercitrin concentration in Moringa oleifera leave. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Figure 11.

Effect of different storage conditions on quercitrin concentration in Moringa oleifera leave. ZV - Zero value – baseline results of material analysed before storage; 4°T - Storage at 4°C with transparent packaging; 4°D - Storage at 4°C opaque packaging; 25°T- Storage at 25°C with transparent packaging; 25°D - Storage at 25°C with opaque packaging; 40°T- Storage at 40°C with transparent packaging; 40°D - Storage at 40°C with opaque packaging. n = 6 per treatment. Results are expressed as the mean values ± standard error (n=6) including control, bars in the same column marked with different letters indicate significance difference at p≤0, 05.

Table 1.

Effects of storage temperature and different packaging materials on amino acids of Moringa oleifera leaf powder.

Table 1.

Effects of storage temperature and different packaging materials on amino acids of Moringa oleifera leaf powder.

| |

Treatments |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

ZV |

4°T |

4°D |

25°T |

25°D |

40°T |

40°D |

| Histidine |

1.22±0a

|

0.87±0.02cd

|

0.94±0.01b

|

0.89±0.01bc

|

0.84±0.02cd

|

0.8±0.01d

|

0.86±0.02cd

|

| Arginine |

2.44±0b

|

2.38±0.01b

|

2.07±0.01c

|

2.52±0.05ab

|

1.96±0.04c

|

2.75±0.05a

|

2.1±0.05c

|

| Serine |

1.98±0.02a

|

1.73±0.05b

|

1.64±0.01b

|

1.66±0.02b

|

1.58±0.02b

|

1.95±0.04a

|

1.58±0.01b

|

| Glycine |

2.65±0a

|

1.86±0.01f

|

1.96±0.01e

|

2.03±0.01d

|

1.93±0.01e

|

2.18±0.01b

|

2.11±0.01c

|

| Aspartic acid |

4.78±0a

|

3.15±0.01c

|

2.56±0.02d

|

2.45±0.02ef

|

2.52±0.01de

|

3.42±0.02b

|

2.35±0.02f

|

| Glutamic |

6.2±0a

|

4.54±0.02c

|

4.33±0.02d

|

3.95±0.01g

|

4.15±0.01e

|

5.16±0.01b

|

4.05±0.02f

|

| Threomine |

2.1±0a

|

1.6±0.02cd

|

1.67±0.01c |

1.56±0.02d

|

1.63±0.02cd

|

1.84±0b

|

1.63±0.02cd

|

| Alanine |

3.77±0a

|

2.05±0.01c

|

1.77±0.01e

|

1.89±0.01d

|

1.8±0.01e

|

2.26±0.01b

|

1.77±0.01e

|

| Proline |

2.98±0a

|

1.4±0.01c

|

1.54±0.05bc

|

1.54±0.02bc

|

1.52±0.01bc

|

1.6±0.01b

|

1.59±0.01b

|

| Lysine |

4.56±0a

|

2.72±0.02f

|

2.9±0.01e

|

3.43±0.02c

|

2.87±0.01e

|

3.26±0.01d

|

3.59±0.01b

|

| Tyrosine |

2.44±0a

|

1.22±0.01g

|

0.97±0.01f

|

0.54±0.01c

|

1.04±0.01b

|

1.12±0.01e

|

0.63±0.01d

|

| Methionine |

1.22±0a

|

0.54±0d

|

0.54±0.01d

|

0.65±0c

|

0.54±0d

|

0.88±0b

|

0.57±0d

|

| Valine |

4.44±0a

|

1.91±0.01de

|

1.85±0.02e

|

2±0.02c

|

1.86±0.02e

|

2.14±0.01b

|

1.94±0.01cd

|

| Isoleucine |

2.33±0a

|

1.44±0.01c

|

1.49±0.01c

|

1.57±0.01b

|

1.47±0.01c

|

1.6±0.01b

|

1.61±0.01b

|

| Leucine |

4.33±0a

|

2.6±0.01f

|

2.83±0.01e

|

2.89±0.01d

|

2.89±0.01d

|

3±0c

|

3.13±0.01b

|

| Phenylalanine |

5.33±0a

|

2.92±0.01g

|

3.2±0.01f

|

3.75±0c

|

3.28±0.01b

|

3.52±0.01e

|

3.96±0.01d

|

Table 2.

Effect of storage temperature and different packaging materials on microbial contamination of Moringa oleifera leaf powder.

Table 2.

Effect of storage temperature and different packaging materials on microbial contamination of Moringa oleifera leaf powder.

| Microorganisms (CFU/g) |

|---|

| Treatments |

E.c |

S.Sp. |

S.a |

B.c |

Ac |

Tc |

Y&m |

| ZV |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

<10 |

20 |

0.5 x 102

|

| 4°T |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

<10 |

33 |

< 10 |

| 4°D |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

10 |

33 |

< 10 |

| 25°T |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

20 |

50 |

< 10 |

| 25°D |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

40 |

55 |

< 10 |

| 40°T |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

60 |

56 |

< 10 |

| 40°D |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

40 |

50 |

< 10 |

| SANS1683:2015 Requirements |

0 |

NS |

NS |

0 |

NS |

≤1.0 x 102

|

≤5.0 x 102

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).