1. Introduction

Domain adaptation remains a fundamental challenge in natural language processing, especially when pre-trained language models are applied to specialized text collections characterized by distinctive vocabularies, stylistic conventions, and unique semantic relationships that significantly diverge from general-domain data [

1,

2]. While transformer-based language models such as BERT and RoBERTa demonstrate outstanding performance on standard NLP benchmarks, their effectiveness often notably decreases within specialized domains, where precise understanding of domain-specific linguistic nuances is crucial [

3,

4]. This performance gap becomes particularly critical in scenarios where traditional fine-tuning methods require substantial computational resources or where domain-specific training data is limited [

5,

6].

Traditional domain adaptation methods often demand significant computational power and extensive annotated or unlabeled datasets, rendering them impractical for many specialized applications [

2,

7]. Domain-adaptive pre-training methods, although effective, also incur substantial computational overhead and require considerable domain-specific data, limiting their real-world applicability [

8,

9]. Therefore, there exists a clear need for more efficient, interpretable, and effective domain adaptation methodologies suitable for resource-constrained deployment scenarios.

Recently, contrastive learning has emerged as a promising strategy for learning robust text representations with minimal manual annotations [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Methods such as SimCSE leverage contrastive objectives to cluster semantically similar representations while differentiating dissimilar ones, significantly improving sentence embedding quality [

10]. Furthermore, recent advances integrating feedback from large language models (LLMs) have introduced nuanced, graduated similarity signals, further enhancing contrastive learning outcomes [

14]. However, existing contrastive learning frameworks frequently rely on generic masking strategies, uniformly masking tokens without considering their semantic importance, potentially overlooking critical domain-specific semantic cues [

6,

15].

The central challenge lies in the mismatch between generic masking strategies optimized for general domains and the precise semantic structures intrinsic to specialized text corpora. While existing LLM-based methods provide valuable fine-grained supervision [

16,

17], their generic augmentation often neglects critical domain-specific knowledge that could significantly boost adaptation performance. Moreover, graduated similarity feedback derived from LLMs remains underexplored when systematically combined with domain-aware masking strategies [

18,

19].

To address these limitations, this paper proposes a novel domain adaptation framework that integrates LLM-guided weighted contrastive learning with a topic-aware masking strategy explicitly tailored for specialized textual domains. The proposed method leverages topic modeling techniques [

20] to systematically identify domain-critical terms, guiding precise masking strategies through three targeted approaches: single-keyword masking for precise semantic distinctions, multiple-keyword masking for comprehensive contextual understanding, and partial-keyword masking for nuanced linguistic relationships. These masking strategies ensure meaningful augmentation by preserving critical semantic integrity while systematically introducing controlled semantic variations guided by LLM feedback.

The effectiveness of the proposed framework is evaluated on an early 20th-century science fiction corpus, a specialized domain characterized by unique vocabularies and intricate linguistic patterns. A comprehensive empirical evaluation conducted using the newly developed SF-ProbeEval benchmark demonstrates consistent performance improvements compared to state-of-the-art contrastive learning baselines, including SimCSE and DiffCSE, while achieving these improvements with significantly reduced computational overhead.

The primary contributions of this work are as follows:

Domain-aware weighted contrastive learning framework: Introduction of a systematic topic modeling-based masking approach combined with graduated LLM similarity feedback, significantly outperforming generic masking strategies while maintaining computational efficiency through minimal training requirements (2 epochs vs. traditional 10-40 epochs);

SF-ProbeEval benchmark: Development of the first specialized benchmark for early 20th-century science fiction text understanding, comprising five linguistically targeted probing tasks that address the gap in domain-specific evaluation frameworks for historical literary corpora;

Comprehensive empirical validation: Rigorous experimental evaluation demonstrating consistent improvements across multiple linguistic metrics with practical applicability for specialized text processing scenarios where traditional fine-tuning is resource-intensive or impractical.

This research advances efficient and interpretable domain adaptation methodologies, particularly emphasizing computational efficiency, representation quality, and practical deployment considerations for electronics and technology applications where specialized text understanding is critical.

2. Related Works

2.1. Mathematical Formulation of Domain Adaptation

Domain adaptation for language models can be formalized as learning a mapping function

where

represents the source domain (general text) and

represents the target domain (specialized text). The objective is to minimize the domain discrepancy while preserving semantic relationships:

where

represents the task-specific loss and

captures domain alignment.

The theoretical foundation of domain adaptation rests on understanding the relationship between source and target domain distributions. Classical domain adaptation theory establishes that target error can be bounded by source error plus a domain discrepancy term [

21]:

where

measures domain discrepancy and

represents the combined error of the ideal joint hypothesis.

However, fundamental limitations of naive domain adaptation have been rigorously established. Zhao et al. demonstrated that blindly enforcing feature invariance can hurt target performance when label distributions differ significantly [

21]. They provide a crucial lower bound:

proving that when source and target label priors are misaligned, invariant representations may increase target error.

This insight led to sophisticated divergence measures like the Margin Disparity Discrepancy (MDD) [

22] and

f-divergence frameworks [

23]. Recent advances address large domain gaps through gradual adaptation [

24], open-set scenarios with novel classes [

25], and information-theoretic bounds [

26]. These theoretical developments establish mathematical foundations that directly inform sophisticated adaptation strategies, including weighted contrastive learning approaches for specialized domain scenarios.

2.2. Domain Adaptation for Specialized Text Collections

Pre-trained models exhibit performance degradation on specialized texts due to unique vocabulary, domain-specific syntax, and specialized semantic relationships that differ significantly from general training corpora [

1]. Domain-adaptive pre-training (DAPT) through continued masked language modeling on target corpora remains the primary strategy, with demonstrated improvements across diverse domains [

2]. However, DAPT approaches often require substantial computational resources and extensive domain-specific corpora, making them impractical for many specialized applications.

Specialized text processing has witnessed methodological advances addressing resource constraints. Contextualized Construct Representations combine psychometric expertise with transformers for Classical Chinese analysis, employing supervised contrastive learning to address data scarcity [

27]. The Adapt-Retrieve-Revise framework achieves substantial gains in legal domains by integrating model adaptation with LLM-based evidence assessment [

28].

Purpose-built models also show domain-specific superiority but require extensive resources. For example, MacBERTh, trained on English texts from 1450–1950, outperforms adapted variants on period-specific tasks [

29], though such models demand substantial computational investment and large domain-specific corpora.

Despite these advances, existing domain adaptation approaches face limitations when applied to specialized text collections. Traditional fine-tuning methods require extensive computational resources, while generic contrastive learning approaches fail to capture domain-specific semantic nuances. The challenge lies in developing efficient adaptation strategies that leverage domain-specific knowledge without demanding prohibitive computational overhead.

2.3. Contrastive Learning for Sentence Embeddings

Contrastive learning has emerged as the dominant paradigm for universal sentence representations. SimCSE established foundational principles through dropout noise augmentation in unsupervised settings and Natural Language Inference pairs for supervised variants [

10]. The unsupervised SimCSE employs different dropout masks on the same input sentence to create positive pairs:

where

and

with different dropout masks

and

.

Building upon foundational approaches like Skip-Thought vectors [

30] and Quick-Thought [

31], ConSERT demonstrated that sophisticated data augmentation strategies—including adversarial attacks, token shuffling, and cutoff operations—can significantly improve unsupervised sentence embeddings [

11]. DiffCSE introduced conditional masking strategies generating semantically distinct positive pairs through equivariant contrastive learning [

13]. The framework combines contrastive learning with a Replaced Token Detection (RTD) objective, enabling the model to learn from both contrastive signals and token-level discrimination tasks.

Advanced contrastive methods address specific limitations through targeted innovations. Self-guided contrastive learning introduces auxiliary encoders that provide guidance embeddings, mitigating representation collapse [

32]. DeCLUTR leverages natural document structure by using adjacent spans as positive pairs [

12], while approaches like semantic re-tuning explore contrastive tension mechanisms [

33]. These developments demonstrate that sophisticated augmentation strategies substantially enhance representation quality beyond traditional approaches.

Recent advances incorporating large language model feedback have further enhanced contrastive learning effectiveness. CLAIF marked a paradigm shift by leveraging LLMs for continuous similarity scores, replacing binary supervision with fine-grained feedback [

14]. CLAIF employs graduated similarity scores

but relies on Mean Squared Error loss:

This approach, while providing fine-grained supervision, abandons the contrastive framework’s inherent advantages. Moreover, CLAIF employs generic masking strategies that treat all tokens with equal importance, potentially missing domain-critical semantic relationships essential for specialized text understanding [

15].

Contemporary developments address various limitations while achieving new benchmarks. SimCSE++ resolves dropout noise contamination and rank bottlenecks through dimension-wise contrastive objectives [

34]. Methods like whitening [

35] and prompt-based approaches [

36] explore alternative supervision mechanisms. Domain-specific innovations demonstrate the potential for specialized contrastive learning, yet most advances focus on general-domain, high-resource settings [

37].

The primary challenge lies in the mismatch between generic augmentation strategies designed for general domains and the distinctive semantic structures inherent to specialized text collections. Although LLM-feedback methods offer valuable supervision through synthetic data generation [

38,

39] and constitutional AI approaches [

40], their generic masking fails to exploit domain-specific knowledge. This represents a significant gap in adapting contrastive learning to specialized text collections, where intelligent vocabulary selection and domain-aware semantic understanding are crucial for effective representation learning.

2.4. Domain-Aware Augmentation Strategies

Effective contrastive learning heavily relies on the quality of generated positive and negative sentence pairs [

10,

13]. Traditional generic augmentation methods, including random masking, token shuffling, and syntactic perturbations, typically fail to recognize the disproportionate semantic importance certain terms hold within specialized domains. Such approaches assume uniform importance across tokens, potentially obscuring crucial domain-specific semantic structures and inadvertently introducing noise [

15,

37].

Topic modeling approaches, such as BERTopic, have emerged as valuable techniques for systematically identifying semantically coherent clusters of terms within specialized corpora, providing an effective foundation for domain-aware augmentation [

20]. Despite their potential, integration of topic modeling insights into contrastive learning frameworks remains significantly underexplored. Leveraging domain-specific vocabulary identification to guide precise masking strategies represents an important research opportunity for substantially improving contrastive learning effectiveness in specialized textual domains.

This paper directly addresses these research gaps by proposing an innovative domain-aware augmentation approach that integrates topic modeling-based masking strategies with fine-grained similarity assessments from large language models. The proposed methodology explicitly targets domain-critical terms, ensuring semantically meaningful augmentations to enhance the effectiveness and interpretability of language model adaptation to specialized textual domains.

3. Methodology

3.1. Problem Formulation

Given a specialized domain corpus

where each

represents a sentence, the objective is to learn domain-adapted sentence representations

that capture specialized semantic relationships. This research formulates domain adaptation as an optimization problem where the model parameters are learned through weighted contrastive learning:

where

represents the LLM-enhanced positive pair and

denotes the graduated similarity score provided by large language model assessment. This formulation differs from traditional contrastive learning by incorporating continuous supervision signals rather than binary similarity judgments, enabling more nuanced semantic relationship learning essential for specialized domain adaptation.

3.2. Domain-Specific Dataset Construction

This research employs a curated collection of specialized domain texts to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed framework under challenging adaptation scenarios. The dataset comprises 531 documents with approximately text segments and an estimated distinct sentences after preprocessing and deduplication. The corpus represents a domain characterized by specialized vocabulary, unique stylistic conventions, and domain-specific semantic relationships, making it an ideal testbed for evaluating domain adaptation methodologies under resource-constrained conditions. All subsequent processing—including similarity assessment, contrastive pair generation, and model training—relies exclusively on this specialized domain collection, ensuring that evaluation reflects realistic deployment scenarios where practitioners must adapt models to specific application domains with limited available data.

3.3. Language Model Architectures

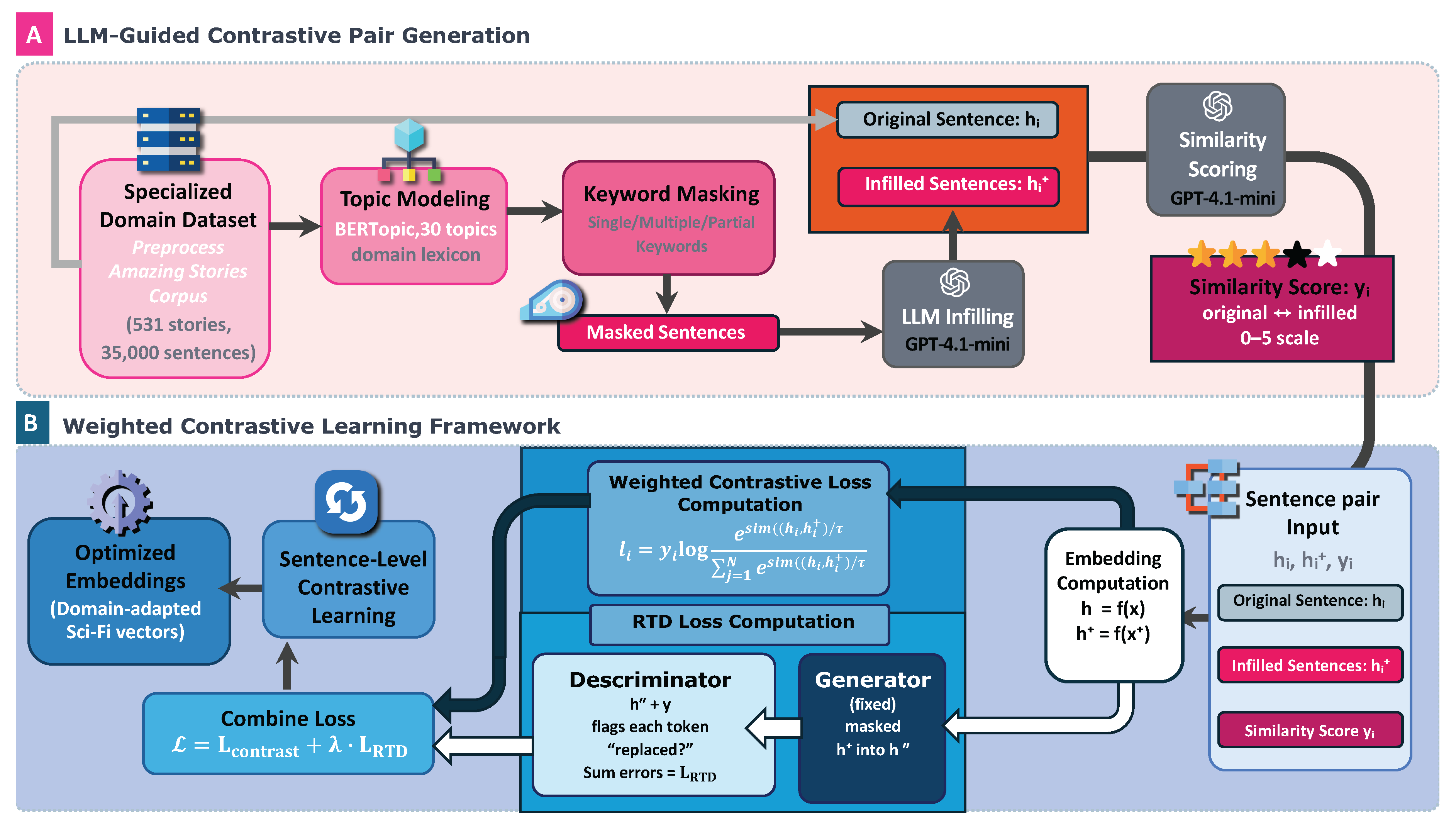

Two established transformer-based encoders serve as foundation models for the adaptation framework: BERT-base (uncased) and RoBERTa-base. The selection of these architectures demonstrates the model-agnostic nature of the proposed approach, ensuring that the framework’s effectiveness extends across different pre-trained language model architectures. The methodology encompasses two main stages as illustrated in

Figure 1: LLM-guided contrastive pair generation and weighted contrastive learning optimization.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed workflow. (A) LLM-guided contrastive pair generation. A specialized domain corpus is processed using topic modeling (30 topics) to obtain domain-specific vocabulary. Three masking strategies (single-, multi-, partial-keyword) produce masked sentences which GPT-4.1-mini rewrites into and scores for semantic similarity on a 0–5 scale . (B) Weighted contrastive learning optimization. The triplets are used to fine-tune a pre-trained sentence encoder with the weighted loss so that higher similarity scores pull highly related sentence pairs closer in embedding space, resulting in domain-adapted representations.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed workflow. (A) LLM-guided contrastive pair generation. A specialized domain corpus is processed using topic modeling (30 topics) to obtain domain-specific vocabulary. Three masking strategies (single-, multi-, partial-keyword) produce masked sentences which GPT-4.1-mini rewrites into and scores for semantic similarity on a 0–5 scale . (B) Weighted contrastive learning optimization. The triplets are used to fine-tune a pre-trained sentence encoder with the weighted loss so that higher similarity scores pull highly related sentence pairs closer in embedding space, resulting in domain-adapted representations.

3.4. LLM-Guided Contrastive Pair Generation

The framework employs a sophisticated sentence pair generation strategy that leverages domain-specific masking techniques to create meaningful contrastive examples. The process begins with intelligent keyword identification through topic modeling analysis, enabling systematic masking of domain-critical terms that carry significant semantic weight.

3.4.1. Domain-Aware Masking Strategy

Traditional contrastive learning employs random masking with uniform probability. This research introduces domain-aware masking based on topic modeling results. Let

represent domain-critical vocabulary identified through BERTopic analysis. The masking probability for token

t is defined as:

where

is derived from c-TF-IDF scores, and

to prioritize domain-critical terms. This formulation ensures that semantically important vocabulary receives preferential attention during augmentation, addressing the limitation of generic masking strategies that treat all tokens equally.

Three masking strategies are implemented to capture different levels of semantic variation:

Single-keyword masking: for precise semantic variations

Multiple-keyword masking: where for comprehensive contextual understanding

Partial-keyword masking: for nuanced linguistic relationships

3.4.2. LLM-Based Sentence Generation and Scoring

For each masked sentence

, GPT-4.1-mini generates an infilled version through the infilling function:

To demonstrate the framework’s effectiveness under challenging domain adaptation scenarios, the methodology employs prompts specifically designed for the evaluation corpus characteristics. The LLM receives the infilling prompt:

“Your task is to rewrite the following early 20th-century science fiction sentence by replacing each <mask> token with the most appropriate and coherent word to complete the sentence grammatically while preserving style and meaning. If no suitable word exists, reply None. Sentence: “{masked_sentence}”.”

The same LLM then provides graduated similarity assessment through the scoring function:

The similarity scoring employs the similarity-scoring prompt:

“Rate the similarity of two early 20th-century science fiction sentences on a 0–5 scale. Consider: (1) core meaning, (2) treatment of SF devices, (3) temporal/spatial/technological consistency, (4) fidelity to key topic words. Return only the numerical score.”

This process creates training triplets where y provides fine-grained supervision that captures semantic nuances unavailable in binary classification approaches. The domain-specific prompting approach demonstrates the framework’s adaptability to specialized text collections while maintaining scientific rigor.

3.5. Weighted Contrastive Learning Framework

As shown in

Figure 1B, the weighted contrastive learning process utilizes the generated sentence pairs to enhance domain-sensitive representations. The framework addresses fundamental limitations in existing contrastive learning approaches while building upon their structural advantages. Unlike SimCSE [

10]’s reliance on generic dropout noise as the sole augmentation mechanism, this research introduces domain-aware masking strategies that systematically target vocabulary elements with high semantic significance within specialized domains. Where SimCSE employs identical sentences with different dropout masks as positive pairs, the proposed approach generates semantically varied but related sentences through intelligent masking and LLM-guided reconstruction.

The framework integrates the dual-objective structure of DiffCSE [

13] with graduated supervision mechanisms inspired by CLAIF [

14], while addressing critical limitations in both approaches. DiffCSE employs binary token-level supervision without fine-grained similarity guidance, while CLAIF abandons the contrastive learning structure entirely in favor of regression-based objectives. The proposed method preserves contrastive learning’s comparative advantages while incorporating continuous LLM-derived supervision.

Let represent the embedding of an anchor sentence, its LLM-processed variant, and the associated similarity score. The training objective combines two complementary losses:

Weighted Contrastive Loss:where

N represents the batch size,

denotes the cosine similarity function,

is the temperature parameter, and

is the LLM-generated similarity score that serves as a continuous weight rather than a binary supervision signal. This weighted contrastive objective differs from SimCSE’s uniform treatment of positive pairs by incorporating graduated similarity scores

as continuous supervision weights. Unlike CLAIF’s approach of replacing contrastive learning with MSE regression (

), this formulation maintains the comparative learning structure while providing nuanced guidance through LLM-generated similarity assessments.

Replaced Token Detection (RTD) Loss: Following DiffCSE, the framework incorporates a Replaced Token Detection loss to enhance the model’s sensitivity to semantic variations at the token level. The RTD mechanism operates through a three-stage process: (1) domain-aware masking of the original sentence x to create , (2) LLM-based reconstruction to generate , and (3) token-level discrimination to identify which positions contain original versus generated tokens.

For a sentence of length

T, the RTD loss is formulated as:

where:

T denotes the sentence length (number of tokens)

represents the t-th token in the original sentence x

represents the t-th token in the LLM-generated sentence

is the indicator function that returns 1 if the condition is true, 0 otherwise

is the discriminator’s predicted probability that the token at position t has been replaced

is the sentence-level embedding that provides contextual information to the discriminator

The RTD objective functions as a conditional binary classification task at each token position. When the generated token matches the original (), the loss encourages the discriminator to output a low probability (predicting “not replaced”). Conversely, when the tokens differ (), the loss encourages a high probability (predicting “replaced”). This token-level supervision forces the sentence encoder to produce representations that contain sufficient semantic information for accurate token-level discrimination.

The batch-level RTD loss aggregates individual sentence losses:

Combined Training Objective:

The final training objective combines both losses with a weighting coefficient

:

where

balances the relative importance of sentence-level contrastive learning and token-level discrimination. The dual-objective design ensures that the sentence encoder learns representations that are both semantically coherent at the global level (through weighted contrastive learning) and sensitive to fine-grained lexical variations (through RTD supervision).

This architectural innovation addresses key limitations in existing approaches: SimCSE’s inability to distinguish between different levels of semantic similarity, DiffCSE’s reliance on binary token supervision, and CLAIF’s abandonment of comparative learning structures. The integration of graduated LLM feedback as similarity weights, rather than regression targets, preserves the contrastive learning framework’s inherent advantages while providing more informative supervision than traditional binary approaches. The RTD component ensures comprehensive supervision at both sentence and token levels, enabling the framework to capture both global semantic relationships and fine-grained lexical variations essential for specialized domain understanding.

3.6. Implementation Details

Table 1.

Principal hyperparameters for domain adaptation training.

Table 1.

Principal hyperparameters for domain adaptation training.

| Encoder |

Learning Rate |

Masking Ratio |

|

Epochs |

Batch Size |

| BERT-base |

7e-6 |

0.30 |

0.005 |

2 |

64 |

| RoBERTa-base |

1e-5 |

0.20 |

0.005 |

2 |

64 |

The framework is optimized for computational efficiency while maintaining adaptation effectiveness. Training employs minimal epoch requirements (2 epochs for both BERT and RoBERTa) with carefully tuned hyperparameters following established contrastive learning configurations [

13]. The learning rates are set to 7e-6 for BERT-base and 1e-5 for RoBERTa-base, with masking ratios of 0.30 and 0.20 respectively. The temperature parameter

is chosen to create sharper similarity distinctions given the fine-grained 0-5 scoring scale, while the batch size is set to 64 to balance computational efficiency with training stability.

All experiments are conducted on a single NVIDIA A100 GPU, demonstrating the framework’s feasibility for resource-constrained deployment scenarios. Reproducibility is ensured through fixed random seeds and standardized experimental configurations. The complete implementation, including processed datasets and trained model checkpoints, will be made publicly available to facilitate further research and practical applications.

4. Experimental Evaluation

This section evaluates the proposed weighted contrastive learning framework through comprehensive linguistic analysis and comparative assessment against established domain adaptation methods. The evaluation emphasizes practical deployment considerations, computational efficiency, and performance gains achievable under resource-constrained scenarios typical of industrial applications.

4.1. SF-ProbeEval: A Domain-Specific Probing Benchmark

To evaluate embedding quality in early science fiction texts, this research constructs SF-ProbeEval, a specialized benchmark comprising five probing tasks tailored to pulp-era linguistic patterns. Each task contains 1,000 test items derived from the specialized domain corpus, capturing the unique challenges of historical science fiction text understanding.

SF-ProbeEval provides the first standardized benchmark for assessing sentence embedding quality in early 20th-century science fiction texts, addressing the gap in domain-specific evaluation frameworks for historical literary corpora.

4.1.1. Dataset Construction Process

SF-ProbeEval construction follows a two-stage process: automated generation using rule-based algorithms and domain-specific linguistic patterns, followed by expert validation. Three experts from the Department of English Language and Literature reviewed and refined the automatically generated dataset, focusing on linguistic accuracy, difficulty appropriateness, and elimination of generation artifacts. Each test item was evaluated independently by at least two reviewers, with disagreements resolved through consensus-building.

Evaluation Protocol.Table 2 summarizes the SF-ProbeEval tasks employed in this study.

Table 2.

SF-ProbeEval: A Probing Dataset for Early 20th-Century Science Fiction Text Understanding.

Table 2.

SF-ProbeEval: A Probing Dataset for Early 20th-Century Science Fiction Text Understanding.

| Task |

Description |

| Word Contents |

Identify science fiction terminology and archaic vocabulary, evaluating adaptation to period-specific lexicons including scientific devices, astronomical terms, and technological concepts from pulp-era narratives. |

| Tree Depth |

Predict syntactic complexity levels in vintage prose, assessing understanding of elaborate sentence constructions characteristic of 1920s-1930s science fiction writing styles. |

| BShift (Bigram Shift) |

Detect local syntactic perturbations in period-appropriate word sequences, measuring sensitivity to historical word order patterns and archaic grammatical structures. |

| SOMO (Semantic Odd Man Out) |

Identify semantic anomalies within science fiction contexts, evaluating understanding of genre-specific relationships including scientific speculation and technological innovation concepts. |

| Coord_Inv (Coordinate Inversion) |

Detect structural modifications in complex vintage sentences, assessing comprehension of elaborate discourse patterns typical of early science fiction literary style. |

Baseline Comparisons. The framework is evaluated against standard contrastive learning approaches to isolate the contribution of AI-guided feedback mechanisms. Four model variants are compared using both BERT-base and RoBERTa-base architectures: (1) unadapted pre-trained encoders serving as domain adaptation baselines, (2) SimCSE fine-tuning with standard positive sampling strategies, (3) DiffCSE fine-tuning with conditional augmentation methods, and (4) the proposed weighted contrastive framework incorporating graduated similarity feedback while maintaining identical computational constraints and training configurations.

4.2. Performance Analysis

Table 3 presents comprehensive performance comparisons on SF-ProbeEval, demonstrating the practical effectiveness of the proposed framework. The results show consistent and meaningful improvements achieved through AI-guided feedback integration, particularly significant given the resource-constrained adaptation scenario and minimal computational requirements.

Table 3.

Performance comparison across different domain adaptation approaches on SF-ProbeEval benchmark. Results demonstrate the practical effectiveness of AI-guided feedback under resource-constrained deployment scenarios.

Table 3.

Performance comparison across different domain adaptation approaches on SF-ProbeEval benchmark. Results demonstrate the practical effectiveness of AI-guided feedback under resource-constrained deployment scenarios.

| Model |

Method |

Word Contents |

Tree Depth |

BShift |

SOMO |

Coord_Inv |

Avg |

| |

|

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

| BERT |

BERT-base |

47.14 |

19.72 |

67.50 |

63.33 |

79.80 |

55.50 |

| SimCSE |

71.43 |

17.78 |

64.17 |

59.50 |

69.87 |

56.55 |

| DiffCSE |

73.71 |

13.33 |

62.67 |

61.67 |

67.17 |

55.71 |

| Proposed Framework |

67.71 |

19.72 |

70.00 |

65.67 |

81.31 |

60.88 |

| RoBERTa |

RoBERTa-base |

56.00 |

20.00 |

67.17 |

55.17 |

72.90 |

54.25 |

| SimCSE |

74.86 |

13.89 |

48.33 |

60.67 |

48.99 |

49.35 |

| DiffCSE |

78.29 |

15.28 |

53.33 |

58.33 |

51.52 |

51.35 |

| Proposed Framework |

80.86 |

13.33 |

66.67 |

56.50 |

74.07 |

58.29 |

For BERT-based implementations, the proposed framework achieves substantial performance gains with a 5.38% average improvement across evaluation metrics, representing a notable advancement in domain adaptation effectiveness. The framework reaches 60.88% average performance, significantly outperforming BERT-base (55.50%), SimCSE (56.55%), and DiffCSE (55.71%) baselines. These improvements are particularly significant considering the minimal computational requirements—achieved with only 2 training epochs and single GPU deployment, making the approach viable for resource-constrained enterprise environments.

The gains are especially pronounced in tasks critical for specialized domain understanding: word order sensitivity (BShift: 70.00% vs. 67.50% baseline) and coordinate structure comprehension (Coord_Inv: 81.31% vs. 79.80% baseline). These improvements directly translate to enhanced performance in practical applications requiring precise semantic understanding of complex specialized texts.

RoBERTa-based experiments demonstrate similar effectiveness, with the framework delivering a 4.04% average improvement over baseline approaches. Performance reaches 58.29% average across tasks, substantially outperforming RoBERTa-base (54.25%), SimCSE (49.35%), and DiffCSE (51.35%). The framework shows remarkable improvements in domain-specific vocabulary understanding (Word Contents: 80.86% vs. 56.00% baseline) and structural linguistic analysis (Coord_Inv: 74.07% vs. 72.90% baseline).

Significantly, the results reveal critical limitations in standard contrastive methods when applied to specialized domains. Traditional approaches (SimCSE and DiffCSE) occasionally underperform compared to unmodified pre-trained models, suggesting that naive contrastive augmentation strategies may introduce noise rather than meaningful supervision in domain-specific contexts. This phenomenon underscores the importance of intelligent, domain-aware adaptation approaches such as the proposed LLM-guided framework.

The consistent performance improvements across both transformer architectures demonstrate the framework’s model-agnostic effectiveness and broad applicability. These results are particularly valuable for practitioners operating under resource constraints, where even modest improvements translate to significant operational advantages in production environments. The computational efficiency requirements—minimal hardware demands with substantial performance gains—make this approach practical for enterprise deployment scenarios where extensive fine-tuning is economically unfeasible.

4.3. Embedding Quality Assessment

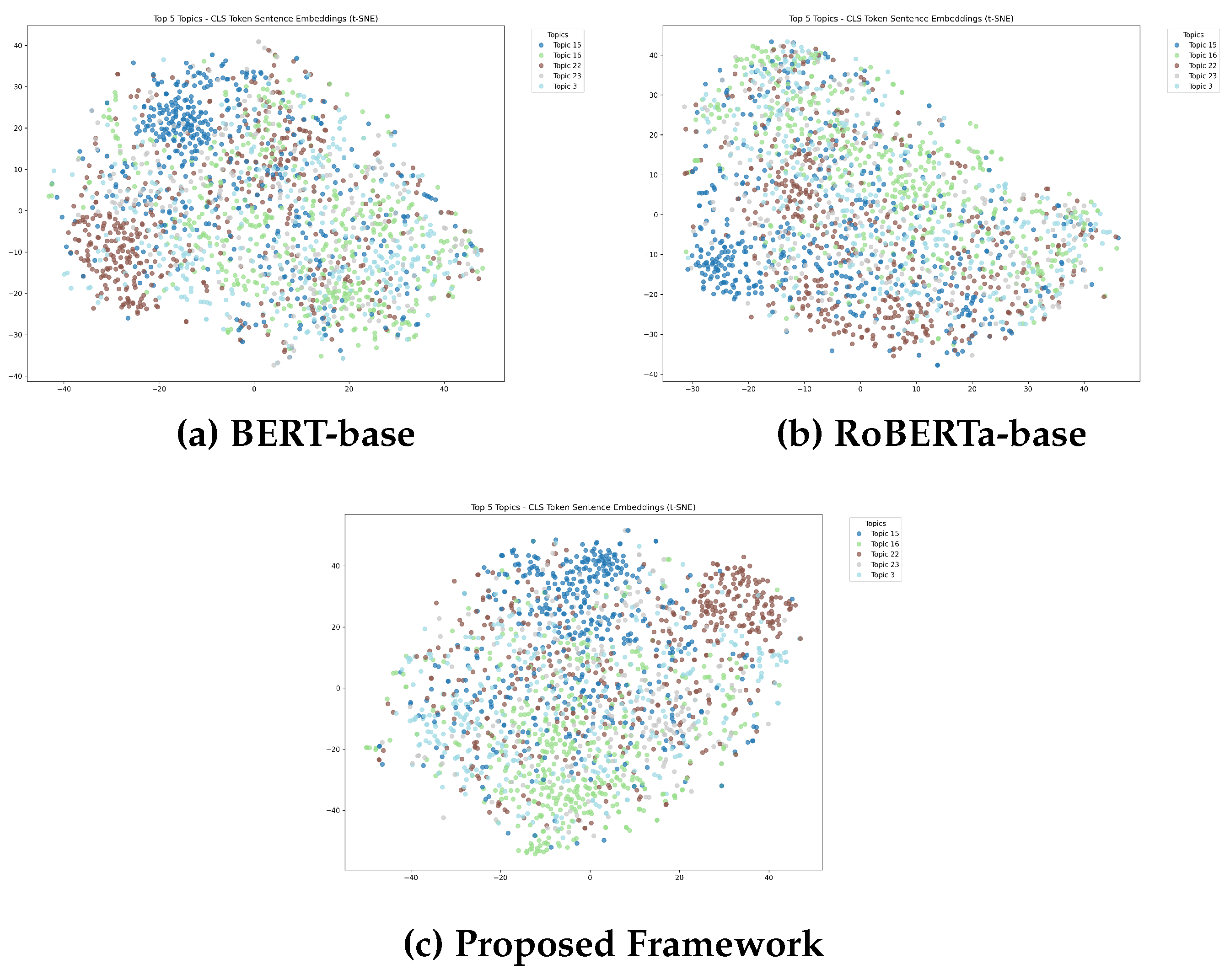

To evaluate the semantic organization capabilities of the proposed framework, this research employs t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) [

41] visualization analysis. The assessment focuses on the top 5 semantic clusters identified through automated topic modeling, comprising 1,962 text segments representing diverse domain-specific content patterns. Sentence embeddings generated by BERT-base, RoBERTa-base, and the proposed framework are reduced using t-SNE with perplexity=30 and random state=42.

Figure 2 illustrates progressive improvements in semantic clustering quality across different approaches. The baseline RoBERTa model exhibits substantial semantic overlap between different content categories, while BERT-base achieves partial but incomplete cluster separation. The proposed weighted contrastive framework demonstrates superior semantic discriminability with tight, well-separated clusters and minimal inter-category interference.

The visualization results confirm that the AI-guided approach effectively enhances semantic organization within specialized domain contexts. This improvement in embedding quality translates directly to better performance in downstream applications requiring precise semantic understanding, such as information retrieval, content categorization, and similarity-based recommendation systems. For enterprise applications, this enhanced semantic organization can significantly improve system accuracy and user satisfaction in domain-specific deployment scenarios, where precise content understanding is critical for operational effectiveness.

Figure 2.

t-SNE projections of sentence embeddings for five domain-specific topic clusters: Neptunian Cataclysm (blue), Scientific Crime Trial (light green), Carnivorous Creatures (brown), Rocket Propulsion Engineering (gray), and Court Rituals (light blue). The proposed framework demonstrates superior semantic discriminability with tight, non-overlapping clusters, indicating enhanced domain-specific understanding.

Figure 2.

t-SNE projections of sentence embeddings for five domain-specific topic clusters: Neptunian Cataclysm (blue), Scientific Crime Trial (light green), Carnivorous Creatures (brown), Rocket Propulsion Engineering (gray), and Court Rituals (light blue). The proposed framework demonstrates superior semantic discriminability with tight, non-overlapping clusters, indicating enhanced domain-specific understanding.

4.4. Ablation Study

Table 4 provides controlled comparison results focusing exclusively on specialized domain training data, isolating the contribution of different contrastive learning methodologies while maintaining consistent training conditions and model architectures. This analysis demonstrates the specific value of AI-generated feedback mechanisms independent of dataset characteristics or training configurations.

Table 4.

Controlled comparison of contrastive learning methodologies using identical specialized domain training data. Results isolate the contribution of AI-guided feedback mechanisms.

Table 4.

Controlled comparison of contrastive learning methodologies using identical specialized domain training data. Results isolate the contribution of AI-guided feedback mechanisms.

| Method |

Word Contents |

Tree Depth |

BShift |

SOMO |

Coord_Inv |

Avg |

| |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

| SimCSE |

69.43 |

16.94 |

64.17 |

61.33 |

75.93 |

57.56 |

| DiffCSE |

66.57 |

18.61 |

70.17 |

66.00 |

78.96 |

60.06 |

| Proposed Framework |

67.71 |

19.72 |

70.00 |

65.67 |

81.31 |

60.88 |

The proposed weighted contrastive framework achieves 60.88% average performance, consistently outperforming both SimCSE (57.56%) and DiffCSE (60.06%) when all methods utilize identical training data and computational resources. This controlled comparison demonstrates that performance improvements stem specifically from the AI-generated feedback mechanism rather than from dataset characteristics, training configurations, or computational advantages.

The results show particularly strong advantages in complex linguistic understanding tasks critical for specialized domain applications: coordinate structure analysis (Coord_Inv: 81.31% vs. 75.93% for SimCSE and 78.96% for DiffCSE) and semantic coherence evaluation (SOMO: 65.67% vs. 61.33% for SimCSE and 66.00% for DiffCSE). These improvements indicate that graduated similarity scores enable more sophisticated semantic relationship learning compared to conventional binary supervision approaches, providing practical advantages for applications requiring nuanced understanding of specialized text collections.

Hierarchical syntax understanding (Tree Depth: 19.72%) shows more modest improvements over baseline methods (16.94% for SimCSE, 18.61% for DiffCSE), highlighting areas for future development in complex structural linguistic analysis. Nevertheless, the consistent gains across multiple evaluation dimensions confirm the framework’s effectiveness for practical domain adaptation applications where semantic understanding is prioritized over purely syntactic analysis.

The controlled experimental design validates that the observed improvements represent genuine methodological advances rather than experimental artifacts, providing confidence for practitioners considering deployment in production environments where performance reliability is critical.

5. Discussion

5.1. Effectiveness of AI-Generated Feedback

This research demonstrates the technical effectiveness of integrating graduated similarity feedback from large language models into contrastive learning frameworks. The fine-grained supervision provided by GPT-4.1-mini consistently improves embedding quality across multiple evaluation metrics, representing a methodological advancement over traditional binary contrastive approaches. The graduated similarity assessment addresses a fundamental limitation in contrastive learning by providing continuous rather than discrete supervision signals, enabling more sophisticated representation learning that captures subtle semantic distinctions essential for specialized domain understanding.

5.2. Computational Efficiency and Resource Constraints

The framework’s computational efficiency—requiring only 2 training epochs compared to traditional domain adaptation approaches requiring 10-40 epochs—represents a significant practical advancement for domain adaptation scenarios where computational resources are limited. This efficiency makes the methodology accessible for research applications and specialized domain processing tasks that previously required extensive computational infrastructure. However, the approach introduces a trade-off between reduced training overhead and LLM inference costs during data preparation, which organizations must consider in practical deployments.

5.3. Framework Design and Transferability

While demonstrated using early 20th-century science fiction as a representative challenging domain, the methodology’s design principles enable application to other specialized domains sharing similar characteristics: unique vocabulary, limited training data, and domain-specific semantic relationships. The domain-agnostic framework design suggests applicability to technical documentation, legal texts, and scientific literature where similar adaptation challenges arise. However, the effectiveness of domain transfer remains empirically unvalidated, and different specialized domains may exhibit varying degrees of linguistic complexity that could affect framework performance.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This research presents several important limitations that warrant careful consideration. The reported performance improvements are modest in magnitude (approximately 5% average gain), and the absence of statistical significance testing limits confidence in result reliability. The single-domain evaluation, while methodologically sound, constrains generalizability claims across diverse specialized domains. The reliance on GPT-4.1-mini for similarity assessment introduces potential biases that require validation against expert human annotations. Future research should incorporate multiple experimental runs with statistical testing, validation across diverse specialized domains, and comparison with domain-adaptive pre-training baselines. The framework would benefit from human expert correlation studies and cost-benefit analyses for practical deployment guidance.

6. Conclusion

This research contributes a computationally efficient methodology for domain adaptation that balances performance improvements with resource constraints. The integration of graduated LLM feedback into weighted contrastive learning provides a practical pathway for adapting pre-trained models to specialized domains without extensive computational infrastructure or manual annotation requirements.

The framework demonstrates that intelligent automation of supervision generation can achieve competitive performance while substantially reducing resource requirements, providing a viable approach for specialized text processing applications where traditional fine-tuning methods are impractical. Experimental validation on a challenging specialized text collection shows consistent improvements across linguistic evaluation tasks while requiring minimal computational overhead.

Despite modest performance gains and the need for broader validation, this methodology opens new avenues for heritage digitization and computational humanities applications, offering a foundation for extending modern NLP capabilities to understudied specialized domains. The framework establishes the viability of AI-assisted contrastive learning for domain-specific text embedding adaptation while highlighting important directions for future investigation across diverse specialized text processing scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.; methodology, S.K.; software, S.K.; validation, S.K.; formal analysis, S.K.; investigation, S.K.; resources, S.K.; data curation, S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, S.K.; visualization, S.K.; project administration, S.K.; The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository: The original data presented in this study (SF-ProbeEval benchmark, sentence–pair corpus with GPT-4.1-mini similarity scores, trained model checkpoints, and full source code) will be made openly available in a GitHub repository; the repository URL will be provided upon acceptance of this manuscript.

Data derived from public domain resources: Parts of the corpus were derived from the public-domain

Amazing Stories magazine scans (1926–1931) available at the Internet Archive (

https://archive.org/details/amazingstoriesmagazine).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, the author used GPT-4.1-mini (OpenAI) to generate sentence-pair similarity scores and to refine aspects of the experimental design. The author has reviewed and edited all AI-generated material and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. No external funding was received for this research.

Appendix A. Methodological Details

Appendix A.1. GPT-4.1-mini Prompts and API Configuration

The following prompts were used to ensure reproducible AI-assisted sentence pair generation and similarity assessment.

Mask Infilling Prompt Template:

Your task is to rewrite the following early 20th-century science fiction

sentence by replacing each <mask> token with the most appropriate and

coherent word to complete the sentence grammatically while preserving

the style and meaning. If you cannot fill in the blanks, just say None

as your answer.

|

|

| Sentence: "{masked_sentence}" |

Similarity Scoring Prompt Template:

Your task is to rate the similarity of two sentences drawn from early

20th-century science-fiction prose.

Return a single floating-point score between 0 and 5 inclusive, using

the rubric below.

Consider four aspects when judging similarity:

1. preservation of the core meaning,

2. retention or plausible substitution of SF devices,

3. consistency of temporal, spatial, and technological background,

4. fidelity to key SF topic words.

|

|

Scoring scale:

5 – Sentences are fully equivalent; all important and minor details, SF

devices, setting, and keywords are preserved.

4 – Sentences are nearly equivalent; only trivial or stylistic details

differ.

3 – Sentences share the main idea and SF context, but at least one

important detail (device, setting, or key event) differs.

2 – Sentences are largely different; they share a few minor words or a

very general SF motif but diverge in key meaning or setting.

1 – Sentences are unrelated in meaning; they share only a broad genre

topic (both mention ’space,’ for instance) without common content.

0 – Sentences share no substantive or topical overlap at all.

|

|

Sentence 1: {sentence1}

Sentence 2: {sentence2}

|

|

| Based on the above rubric, **provide only the numerical similarity

score (0-5)**: |

API Configuration:

Model: GPT-4.1-mini

Temperature: 0.1 (for consistency)

Max tokens: 150 for infilling, 10 for scoring

Retry attempts: 3 for failed requests

API calls: Sequential processing with 1-second delays

Table A1.

Examples of GPT-4.1-mini similarity scoring for sentence pairs from the Amazing Stories corpus.

Table A1.

Examples of GPT-4.1-mini similarity scoring for sentence pairs from the Amazing Stories corpus.

| Original Sentence |

Infilled Sentence |

Score |

| We established ourselves with our apparatus in a building which he rented and went ahead with our experiments |

We established ourselves with our equipment in a building which he rented and went ahead with our experiments |

5 |

| They wouldn’t have the information to give the Hans, nor would they be capable of imparting it. |

They wouldn’t have the technology to give the Hans, nor would they be capable of imparting it. |

4 |

| The gas for this purpose is drawn from a hole tapped through the cliff. |

The pipe for this purpose is drawn from a hole tapped through the cliff. |

3 |

| Suppose a great star from outside should come into the solar system? |

Suppose a great ship from outside should come into the harbor? |

2 |

Appendix A.2. Masking Strategy Examples

The domain-aware masking strategies employ three distinct approaches to generate meaningful positive pairs while preserving the semantic coherence of early 20th-century science fiction prose.

Single-keyword Masking:

Original: “At least, I have employed a ray destructive to haemoglobin — the red blood cells.”

Masked: “At least, I have employed a <mask> destructive to haemoglobin — the red blood cells.

Multiple-keyword Masking:

Original: “The orbit of this planet was assuredly interior to the orbit of the earth, because it accompanied the sun in its apparent motion; yet it was neither Mercury nor Venus, because neither one nor the other of these has any satellite at all.”

Masked: “The <mask> of this <mask> was assuredly interior to the orbit of the earth, because it accompanied the sun in its apparent motion; yet it was neither Mercury nor Venus, because neither one nor the other of these has any <mask> at all.”

Partial-keyword Masking:

Original: “in four great cones, or space-ships, to establish themselves upon earth”

Masked: “in four great cones, or <mask>ships, to establish themselves upon earth.”

Appendix B. Corpus Analysis Results

Appendix B.1. Complete Topic Classification

Table A2 presents the complete topic classification results obtained from BERTopic analysis applied to the

Amazing Stories corpus (1926–1931).

Table A2.

Complete Topic Classification Results from BERTopic Analysis.

Table A2.

Complete Topic Classification Results from BERTopic Analysis.

| Topic ID |

Label |

| 0 |

Asian Servant Stereotype |

| 1 |

Bombardment Warfare |

| 2 |

Interplanetary Diplomatic Council |

| 3 |

Court Rituals |

| 4 |

Fourth-Dimensional Geometry |

| 5 |

Ornate Costume Descriptions |

| 6 |

Optical Invisibility Experiment |

| 7 |

Green Prism Miracle |

| 8 |

Opulent Interior Architecture |

| 9 |

Comic Planetary Voyage |

| 10 |

Reckless Automobile Chase |

| 11 |

Antitoxin Research |

| 12 |

Clinical Hospital Drama |

| 13 |

Shining One Cult |

| 14 |

Lunar Surface Exploration |

| 15 |

Neptunian Cataclysm |

| 16 |

Scientific Crime Trial |

| 17 |

Civilization Retrospective |

| 18 |

Close-Quarters Combat |

| 19 |

Industrial Capitalism |

| 20 |

University Academia |

| 21 |

Philosophy of Discovery |

| 22 |

Carnivorous Creatures |

| 23 |

Rocket Propulsion Engineering |

| 24 |

Atomic Particle Physics |

| 25 |

Aerial Fleet Warfare |

| 26 |

Mountain Expedition |

| 27 |

Luminous Vortex Phenomena |

| 28 |

Polar Sea Voyage |

| 29 |

Global Geography Overview |

Appendix B.2. Domain Keywords by Topic

Table A3 provides the top domain-specific keywords for selected topics, extracted using BERTopic’s c-TF-IDF weighting scheme. These keywords formed the domain lexicon used for the masking strategies.

Table A3.

Top keywords for selected topics from the Amazing Stories corpus

Table A3.

Top keywords for selected topics from the Amazing Stories corpus

| Topic |

Top Keywords |

| Neptunian Cataclysm |

neptune, astronomical, planet, saturn, jupiter, solar system, comet, toward sun, uranus, astronomer, sky, orbit, telescope, sunward, moon |

| Scientific Crime Trial |

crime, trust, priestley, professor fleckner, detective, crime, district attorney, fleckner, prison, mystery, professor kempton, chandler, prisoner, judge, lawyer, murderer |

| Carnivorous Creatures |

prey, spider, insect, caterpillar, carnivorous, tribesman, bee, claw, fern, wasp, monster, spear, edible, mushroom, beetle |

| Rocket Propulsion Engineering |

gyroscope, rocket tube, power unit, apparatus, ship, velocity, generator, speed, pilot, acceleration, cylinder, unit, torpedo, mechanism, control room |

| Court Rituals |

servant, slave, majesty, ceremony, noble, lord, queen, prayer, master, royal, traitor, high priest, robe, monarch, sanctuary |

References

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Burstein, J.; Doran, C.; Solorio, T., Eds., Minneapolis, Minnesota, jun 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [CrossRef]

- Gururangan, S.; Marasović, A.; Swayamdipta, S.; Lo, K.; Beltagy, I.; Downey, D.; Smith, N.A. Don’t Stop Pretraining: Adapt Language Models to Domains and Tasks. 2020, arXiv:cs.CL/2004.10964]. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, X.; Sun, T.; Xu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Dai, N.; Huang, X. Pre-trained models for natural language processing: A survey. Science China technological sciences 2020, 63, 1872–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.; Zhao, X.; Lu, J.; Deng, C.; Zheng, C.; Wang, J.; Chowdhury, T.; Li, Y.; Cui, H.; Zhang, X.; et al. Domain specialization as the key to make large language models disruptive: A comprehensive survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.18703. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Zhou, H.; He, J.; Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Li, L. On the sentence embeddings from pre-trained language models. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjavacas, E.; Fonteyn, L. Adapting vs. pre-training language models for historical languages. Journal of Data Mining & Digital Humanities 2022, NLP4DH. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, K.; Luong, M.T.; Le, Q.V.; Manning, C.D. Electra: Pre-training text encoders as discriminators rather than generators. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.10555. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Feng, S.; Ding, S.; Pang, C.; Shang, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, Y.; et al. Ernie 3.0: Large-scale knowledge enhanced pre-training for language understanding and generation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.02137. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, T.; Yao, X.; Chen, D. SimCSE: Simple Contrastive Learning of Sentence Embeddings. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Wu, W.; Xu, W. Consert: A contrastive framework for self-supervised sentence representation transfer. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.11741. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, J.; Nitski, O.; Wang, B.; Bader, G. Declutr: Deep contrastive learning for unsupervised textual representations. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.03659. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, Y.S.; Dangovski, R.; Luo, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, S.; Soljačić, M.; Li, S.W.; tau Yih, W.; Kim, Y.; Glass, J. DiffCSE: Difference-based Contrastive Learning for Sentence Embeddings. arXiv 2022, arXiv:cs.CL/2204.10298]. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Q.; Yang, X.; Sun, T.; Li, L.; Qiu, X. Improving Contrastive Learning of Sentence Embeddings from AI Feedback. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023; Rogers, A.; Boyd-Graber, J.; Okazaki, N., Eds., Toronto, Canada, JUL 2023; pp. 11122–11138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, R.; Liu, Z.; Lim, K.H.; Bing, L. An unsupervised sentence embedding method by mutual information maximization. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.12061. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 27730–27744. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, W.X.; Wen, J.R. Debiased contrastive learning of unsupervised sentence representations. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Oh, D.; Huang, H.H. SynCSE: Syntax Graph-based Contrastive Learning of Sentence Embeddings. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 128047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootendorst, M. BERTopic: Neural topic modeling with a class-based TF-IDF procedure. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.05794. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Des Combes, R.T.; Zhang, K.; Gordon, G. On learning invariant representations for domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2019; pp. 7523–7532. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Long, M.; Jordan, M. Bridging theory and algorithm for domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2019; pp. 7404–7413. [Google Scholar]

- Acuna, D.; Zhang, G.; Law, M.T.; Fidler, S. f-domain adversarial learning: Theory and algorithms. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2021; pp. 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, B.; Zhao, H. Gradual domain adaptation: Theory and algorithms. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2024, 25, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, T.H.; Wang, Y.; Yin, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, P. Open-Set Heterogeneous Domain Adaptation: Theoretical Analysis and Algorithm. arXiv 2024, arXiv:cs.LG/2412.13036]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Mao, Y. Information-theoretic analysis of unsupervised domain adaptation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.00706. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Atari, M. Surveying the Dead Minds: Historical-Psychological Text Analysis with Contextualized Construct Representation (CCR) for Classical Chinese. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Al-Onaizan, Y.; Bansal, M.; Chen, Y.N., Eds., Miami, Florida, USA, nov 2024; pp. 2597–2615. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, F.; Kurohashi, S. Reformulating Domain Adaptation of Large Language Models as Adapt-Retrieve-Revise: A Case Study on Chinese Legal Domain. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024; Ku, L.W.; Martins, A.; Srikumar, V., Eds., Bangkok, Thailand, aug 2024; pp. 5030–5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjavacas Arevalo, E.; Fonteyn, L. MacBERTh: Development and Evaluation of a Historically Pre-trained Language Model for English (1450-1950). In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Workshop on Natural Language Processing for Digital Humanities; Hämäläinen, M.; Alnajjar, K.; Partanen, N.; Rueter, J., Eds., NIT Silchar, India, dec 2021; pp. 23–36.

- Kiros, R.; Zhu, Y.; Salakhutdinov, R.R.; Zemel, R.; Urtasun, R.; Torralba, A.; Fidler, S. Skip-thought vectors. Advances in neural information processing systems 2015, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Logeswaran, L.; Lee, H. An efficient framework for learning sentence representations. arXiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Yoo, K.M.; Lee, S.g. Self-guided contrastive learning for BERT sentence representations. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, F.; Gogoulou, E.; Ylipää, E.; Cuba Gyllensten, A.; Sahlgren, M. Semantic re-tuning with contrastive tension. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2021, 2021.

- Xu, J.; Shao, W.; Chen, L.; Liu, L. SimCSE++: Improving contrastive learning for sentence embeddings from two perspectives. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.13192. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Cao, J.; Liu, W.; Ou, Y. Whitening sentence representations for better semantics and faster retrieval. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Jiao, J.; Huang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, D.; Zhuang, F.; Wei, F.; Huang, H.; Deng, D.; Zhang, Q. Promptbert: Improving bert sentence embeddings with prompts. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gao, C.; Zang, L.; Han, J.; Wang, Z.; Hu, S. Esimcse: Enhanced sample building method for contrastive learning of unsupervised sentence embedding. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.04380. [Google Scholar]

- Schick, T.; Schütze, H. Generating datasets with pretrained language models. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Han, J. Generating training data with language models: Towards zero-shot language understanding. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 462–477. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Kadavath, S.; Kundu, S.; Askell, A.; Kernion, J.; Jones, A.; Chen, A.; Goldie, A.; Mirhoseini, A.; McKinnon, C.; et al. Constitutional ai: Harmlessness from ai feedback. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaten, L.v.d.; Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. Journal of machine learning research 2008, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).