1. Introduction

The plant microbiome—the diverse community of microorganisms associated with plant tissues—plays a crucial role in plant health, nutrient uptake, stress tolerance, and adaptation to extreme environments [

1]. Recent research has revealed that microbiome composition is not random but shaped by a variety of intrinsic plant traits, including genome size, secondary metabolite production, and tissue structure [

2,

3]. Yet, the genetic and physiological determinants of microbiome assembly in non-model and stress-adapted plants remain poorly understood.

One such group of interest is the genus

Noccaea (formerly part of

Thlaspi), which includes several species capable of thriving in metal-contaminated soils and hyperaccumulating high concentrations of zinc (Zn), cadmium (Cd), and nickel (Ni)—at concentrations that are toxic to most organisms [

4]. These species represent models for studying heavy metal tolerance and phytoremediation, and at the same time offer a unique opportunity to explore how extreme plant adaptations influence microbial colonisation in roots and leaves.

Noccaea belongs to the Brassicaceae, a family of one of the most diverse lineages of flowering plants, comprising 338 genera and 3,709 species [

5,

6]. The family likely originated around 19 million years ago in the open, dry grasslands of the eastern Mediterranean [

7]. Its evolutionary success has been linked to an ancient polyploidisation event and subsequent processes such as chromosome rearrangements, gene loss or silencing, genome downsizing, and diploidisation [

8,

9]. These events have conferred genomic plasticity and increased mutational robustness, enhancing adaptability to environmental stress[

10,

11]. As a result, many Brassicaceae, including

Noccaea, can colonise harsh, nutrient-poor, and metal-polluted habitats. Based on nuclear transcriptomic markers, the family is currently divided into six major clades (A–F), with

Noccaea,

Thlaspi, and

Brassica species grouped within clade B [

12].

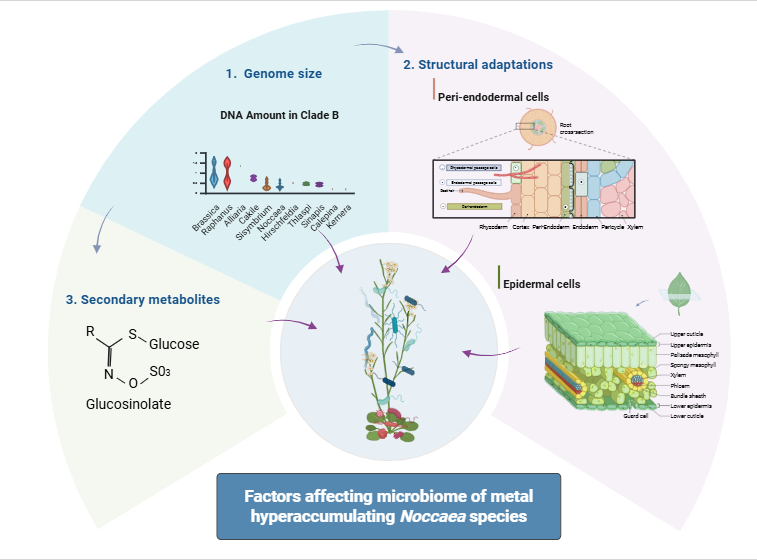

Species of

Noccaea have small genomes, specialised root and leaf structures, and diverse glucosinolate profiles—traits that may significantly influence the structure and function of their microbiomes. For example, small genome size has been hypothesised to enhance ecological adaptability and may affect microbial recruitment by altering metabolic and signalling networks [

13]. Secondary metabolites such as glucosinolates, which are prominent in Brassicaceae, have known antimicrobial properties and may act as chemical filters for microbial colonisation [

14,

15]. Moreover, structural features like peri-endodermal thickenings and epidermal lignification may impose spatial and biochemical constraints on microbial entry and survival [

16].

Despite increasing attention to plant–microbe interactions, the

Noccaea microbiome remains underexplored. Even fundamental questions—such as the mycorrhizal status of these species—remain controversial [

17]. While

Noccaea has long been considered non-mycorrhizal, evidence suggests that under certain conditions, specific fungal symbionts, including Glomeromycota, can colonise their roots, potentially contributing to nutrient cycling and metal tolerance [

18,

19,

20,

21].

This review synthesises current knowledge on the genomic, physiological, and ecological traits of Noccaea species that influence microbiome assembly and function. We discuss how genome evolution, metal hyperaccumulation, secondary metabolism, and tissue structure interact with microbial communities in the rhizosphere and phyllosphere. By highlighting emerging evidence and identifying key gaps, we aim to provide a framework for future research on plant–microbiome co-adaptation and its relevance for phytoremediation and resilience in metal-stressed environments.

2. Phylogenetic Relationships within Noccaea (Formerly Thlaspi) Species

The genus

Thlaspi L., once considered one of the largest genera in the Brassicaceae, comprised approximately 75 species primarily distributed across Eurasia [

6]. However, molecular phylogenetic studies have revealed that

Thlaspi sensu lato (

s.l.) is polyphyletic. This hypothesis was first raised by Meyer in 1973, but gained wide acceptance only after the advent of molecular systematics. Subsequent analyses of nuclear genes and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions provided strong evidence for multiple evolutionary lineages, ultimately supporting the taxonomic reorganisation of

Thlaspi s.l. into distinct monophyletic genera—

Thlaspi sensu stricto,

Noccaea,

Microthlaspi,

Noccidium, and others [

12,

22,

23].

Among these,

Noccaea has emerged as a genus of particular ecological and physiological interest. Al-Shehbaz (2014) presented a comprehensive monograph of

Noccaea, describing 128 species, many of which are adapted to extreme edaphic conditions [

6]. Notably, the genus includes several metal hyperaccumulators, such as

N. caerulescens,

N. cepeaefolia,

N. goesingensis, and

N. praecox, that thrive on naturally and/or anthropogenically metal-rich soils. These species can accumulate extraordinary concentrations of Zn, Cd, and Ni, metals that are typically toxic to most organisms even at trace levels [

4].

Noccaea caerulescens, the most widely studied species of the genus, has become a model system for research in metal homeostasis, adaptation to metalliferous environments, and plant-microbe interactions [

24,

25]. Its close relative,

N. praecox, also exhibits extreme metal tolerance and accumulation traits, especially to Cd [

19,

26,

27] . Phylogenetic reconstruction based on ITS rDNA has shown a 99% sequence similarity between these two species, suggesting a recent divergence in the early Pleistocene, approximately 1.2 million years ago [

28]. This divergence occurred in parallel with the expansion and diversification of perennial

Noccaea species in North America from Eurasian ancestors [

29].

Nuclear gene phylogenies across Brassicaceae support a pattern of nested radiation and convergent morphological evolution [

12]. This evolutionary plasticity is reflected in the repeated emergence of metal tolerance traits and compact genome sizes in several Brassicaceae lineages. The genomic simplification observed in

Noccaea may result from ancient polyploidy followed by genome downsizing, rearrangements, and diploidisation [

8,

9]. These processes, though complicating phylogenetic reconstruction, are also thought to have enhanced mutational robustness and ecological adaptability of Brassicaceae [

10,

11].

Understanding the evolutionary history of Noccaea is thus essential for interpreting its extraordinary physiological traits, including metal hyperaccumulation, compact genome size, tissue-specific structural adaptations, and unique secondary metabolite profiles. These characteristics likely shape its ability to establish highly selective interactions with root- and leaf-associated microbiota. Phylogenetic insights provide a valuable framework for exploring the ecological and functional consequences of these plant traits, especially in the context of microbiome assembly, stress adaptation, and phytoremediation.

3. The Large Genome Size Constraint Hypothesis

Although several whole-genome duplication (WGD) events have occurred in the Brassicaceae [

9,

30,

31,

32], this has not led to a proportional increase in genome size [

8]. Compared to other angiosperms—with more than an eight-fold range in DNA content, or 4.4-fold when excluding allotetraploids—the genomes of most Brassicaceae are relatively small [

33], with genome sizes of the metal hyperaccumulators

Arabidopsis halleri (255 Mbp) and

Noccaea caerulescens (267 Mbp) even smaller than those of

Thlaspi arvense (539 Mbp),

Sinapis alba (553 Mbp), and

Caulanthus heterophyllus (686 Mbp) [

33,

34].

The Large Genome Size Constraint Hypothesis suggests that species with small genomes are more adaptable and capable of colonising diverse environments. In contrast, large-genome species, enriched in non-coding DNA, may face limitations due to slower cell division, lower metabolic efficiency, and reduced tolerance to stress, which could make them more prone to extinction [

35]. In metal-polluted environments, where physiological plasticity and efficient stress response mechanisms are critical, a small genome size may confer a particular advantage [

36,

37]. This may explain why metal hyperaccumulators like

Noccaea exhibit small and stable genomes, supporting their ecological success under extreme edaphic conditions.

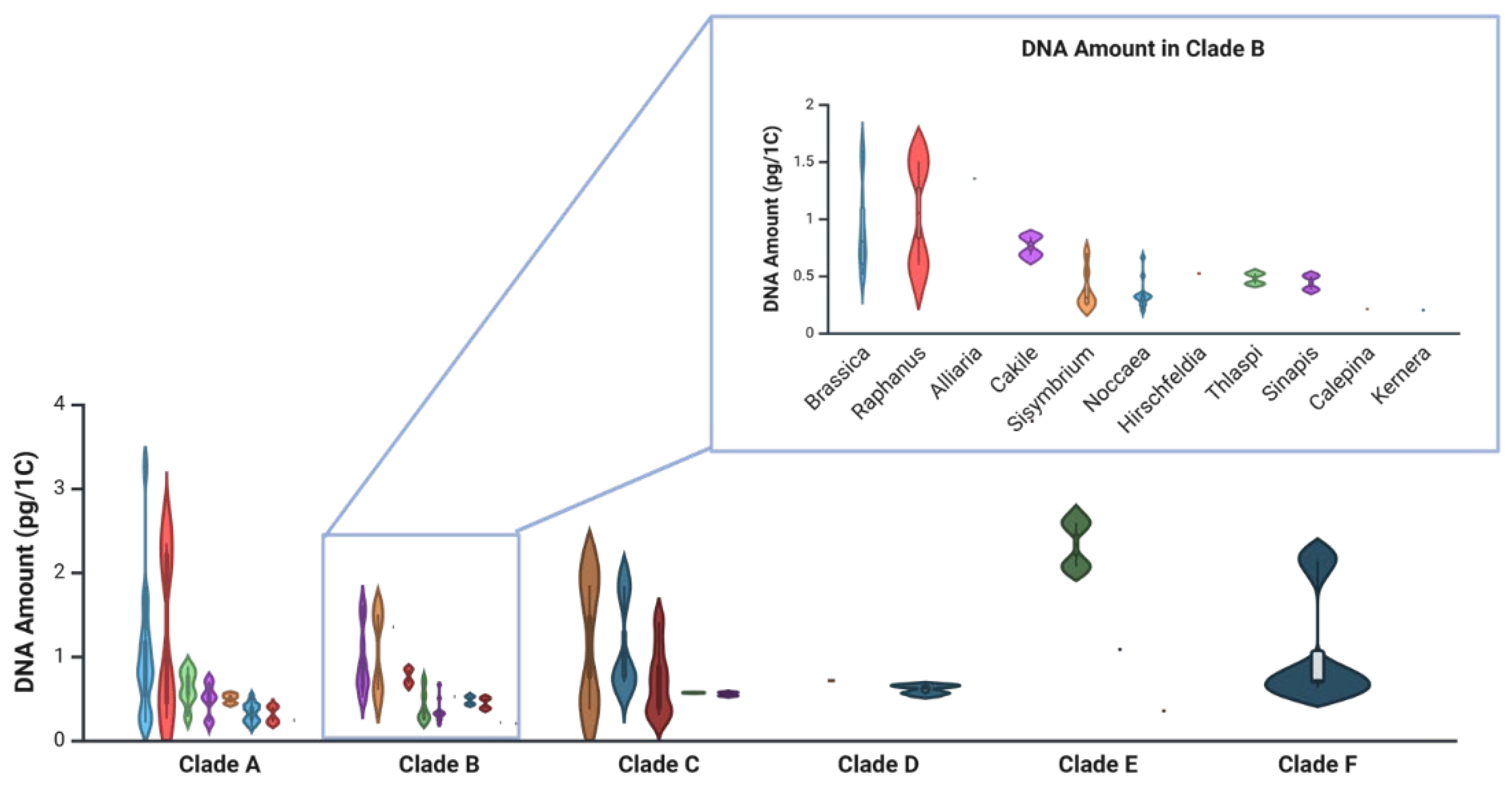

According to data from the Plant DNA C-values Database [

38] Brassicaceae species in clades E and F have the highest average DNA contents (1.98 pg/1C and 1.05 pg/1C, respectively) (

Figure 1;

Table A1), while clade B—home to

Noccaea,

Thlaspi, and

Brassica—has the smallest (0.57 pg/1C) [

12]. Interestingly, species retained in genus

Thlaspi have a higher average DNA amount (0.43 pg/1C) than those assigned to

Noccaea (0.34 pg/1C). Within

Noccaea,

N. alpestris and

N. praecox have the smallest average DNA contents (0.24 and 0.26 pg/1C, respectively). For comparison, average DNA content in

Arabidopsis thaliana ranges from 0.16 to 0.44 pg/1C.

Recent metagenomic work has shown that microbial genome size is shaped by environmental context and trophic strategies [

39]. Metal hyperaccumulator plants, with their chemically and structurally complex tissues, can be viewed as unique microecosystems. Hence, host genome size may also influence the structure and function of associated microbial communities. Genome size in plants varies dramatically (0.065–152.23 pg/1C) [

40,

41] and correlates with traits like cell size, cell cycle control, and metabolic activity [

42,

43], all of which may influence microbial colonisation.

Genome size may also modulate plant-microbe interactions through secondary metabolism. Expansion of specific gene families during WGD may alter secondary metabolite production and defence signalling [

44], thereby affecting microbial recruitment. However, direct testing of the link between host genome size and microbial colonisation remains limited.

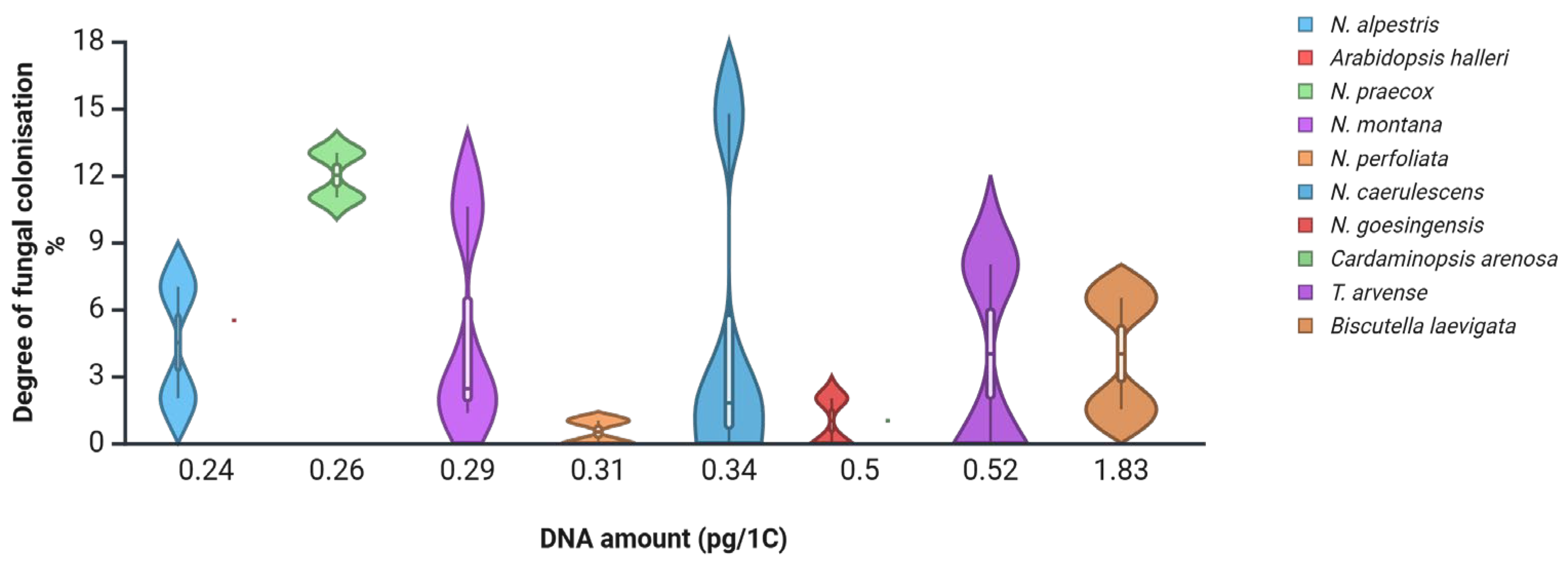

One approach is to estimate root fungal colonisation levels in species with known genome sizes [

38]. In

Noccaea species collected from various polluted and non-polluted sites in Central Europe, the root fungal colonisation levels were generally low [

45], supporting the hypothesis that small-genome species may restrict or tightly regulate microbial entry. When plotted against their corresponding genome size (

Figure 2), it seems species with medium genome sizes may develop the highest root fungal colonisation levels.

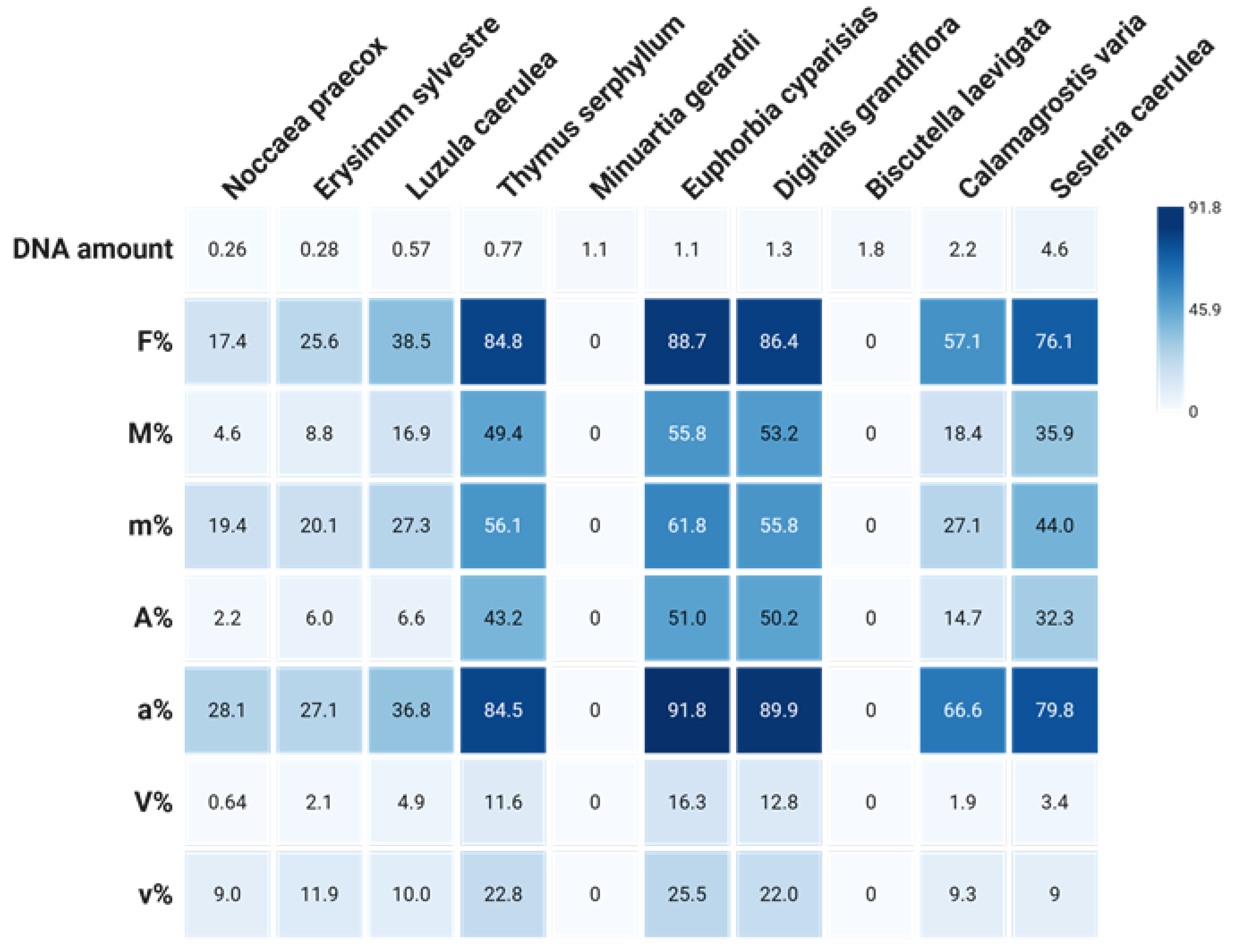

Similar findings were reported from a two-year study on vegetation at a metal-polluted site in Slovenia [

20]. Plants with moderate genome sizes tended to support higher levels of mycorrhizal colonisation (

Figure 3). Nevertheless, some species remained free of colonisation across all sampling periods (e.g.,

Biscutella laevigata,

Minuartia gerardii), although

B. leavigata collected at heavy metal polluted sites in Poland was reported to host arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) [

46], suggesting that factors beyond genome size—such as environmental filtering or chemical defence—may also play significant roles. To date, mycorrhizal status in Brassicaceae still remains controversial [

17].

Species identity is one of the main drivers of plant microbiome composition, followed by the presence of the metal hyperaccumulation trait [

48]. The extent to which genome size impacts colonisation by beneficial microbes remains unclear, but circumstantial evidence is growing. For example, Brassicaceae-associated bacteria often have larger genomes than their free-living relatives, with enriched gene sets for secretion, pongracngraccarbohydrate metabolism, and stress tolerance—adaptations essential for colonising chemically complex hosts [

49]. Similarly, fungal root endophytes tend to have larger genomes than foliar endophytes or saprotrophs [

13], likely reflecting their need for genomic flexibility in navigating plant immunity and nutritional signals.

Collectively, the data support the hypothesis that small genome size in Noccaea and related Brassicaceae species may confer a selective advantage under environmental stress, particularly in metal-polluted habitats. This advantage may be mediated through more efficient growth and physiological plasticity and via modulation of plant–microbe interactions. While direct mechanistic links between genome size and microbiome assembly remain to be fully resolved, mounting evidence suggests that genome size influences microbial compatibility, colonisation patterns, and symbiotic potential. Future research should integrate genome-scale, metabolomic, and microbiome data to untangle these complex relationships and better understand how genome size acts as both a constraint and an opportunity in shaping plant–microbe co-evolution.

4. Genetic Requirements of Metal Hyperaccumulation and Impacts on the Microbiome in Noccaea Species

Brassicaceae hosts the greatest number of metal hyperaccumulating species among dicotyledons, with 103 species currently listed in the Global Hyperaccumulator Database [

4]. The thresholds defining hyperaccumulation are 100 mg kg⁻¹ for Cd, 1000 mg kg⁻¹ for Ni, and 10,000 mg kg⁻¹ (1%) for zinc Zn in dry leaf tissue. According to these criteria, 23

Noccaea species are known to hyperaccumulate Ni, 10 species Zn, and three Cd [

4,

50].

The evolution of metal hyperaccumulation is driven by a combination of natural selection on cis-regulatory regions and gene copy number expansions [

51]. In

A. halleri, tandem triplication of the HMA4 gene (Heavy Metal ATPase 4) facilitates enhanced root-to-shoot metal transport and plays a key role in metal homeostasis, enabling colonisation of Zn- and Cd-contaminated sites [

51,

52]. In

N. caerulescens, a tandem quadruplication of HMA4—arising independently from that in

A. halleri, despite their shared ancestry over 40 Mya, suggests convergent evolution of Zn and Cd hyperaccumulation in Brassicaceae [

53].

Importantly, HMA4 copy number in

N. caerulescens is variable among ecotypes, contributing to intraspecific differences in Cd uptake, xylem loading, and translocation [

54]. Additional genomic mechanisms, such as gene inversion events enhancing expression of HMA4 and ZIP6, as well as expanded gene families related to nicotianamine biosynthesis and transport (NAS2, YSL3, ZIFL1), further contribute to the distinct metal accumulation profiles in

Noccaea species [

34].

At the physiological level, hyperaccumulation and hypertolerance involve several key processes: i) enhanced metal uptake by roots, ii) efficient symplastic transfer to the vascular tissue, iii) accelerated root-to-shoot transport via the xylem, and iv) metal sequestration in leaf vacuoles [

55,

56]. For example, the NcNramp1 transporter shows high expression in roots of the Ganges ecotype, facilitating increased Cd uptake across the endodermal membrane [

57]. Similarly, NcHMA4 is pivotal for Zn and Cd xylem loading and is considered a central regulator of both hyperaccumulation and tolerance [

51,

54]. In the shoots, vacuolar sequestration of Zn is mediated by constitutive expression of NcMTP1, encoding a Zn transporter that mitigates cytoplasmic toxicity [

58]. Transcriptome analysis of the Ganges ecotype further revealed the presence of numerous isotigs encoding metal homeostasis-related proteins, including an extra copy of Metallothionein 3 [

59], a protein that binds metal ions and contributes to detoxification.

Besides plant genetics, microbial partners play an increasingly recognised role in metal accumulation and tolerance. Several fungal endophytes isolated from metalliferous sites were shown to enhance Ni uptake and biomass production in

N. caerulescens, indicating a functional synergy between host and microbiome [

60]. Comparative studies of

Noccaea populations from metal-rich and metal-poor soils show that bacterial and fungal community composition is shaped by both edaphic factors and host genotype [

61,

62]. Microbial communities associated with

Noccaea roots in metalliferous environments often harbour unique taxa with adaptations to high metal loads and show reduced antagonistic interactions, likely due to the selective pressure imposed by the toxic environment [

61].

The capacity for metal hyperaccumulation in Noccaea species is underpinned by a complex network of genetic adaptations, including gene duplications, regulatory mutations, and physiological innovations in metal uptake, transport, and sequestration. These traits enable survival in metalliferous environments and shape the composition and function of the associated microbiome. Fungal and bacterial partners contribute to nutrient acquisition, stress mitigation, and enhanced metal tolerance, suggesting a tightly co-evolved relationship between host and microbiota. The observed intraspecific and interspecific variability in both metal-handling capacity and microbial assemblages underscores the importance of integrating genomics, ecology, and microbiome research to fully understand plant adaptation to extreme environments. Future work focusing on functional metagenomics, transcriptomics, and controlled inoculation studies will be essential to unravel the causal links between host genotype, microbial function, and environmental stress resilience in Noccaea and other metal-tolerant plants.

5. Bioimaging Techniques Reveal Adaptation Mechanisms in the Leaves of Noccaea Species

To withstand the “metal tsunami” posed by excessive levels of Zn, Cd, and Ni in their environment, hyperaccumulating

Noccaea species have evolved remarkable structural and physiological adaptations. These adaptations are often tissue- and cell-specific and can be visualised with high-resolution bioimaging techniques. Since the tip of the leaf matures first [

63] it becomes the primary site of Zn accumulation in

N. caerulescens, whereas Ni shows a more homogeneous distribution throughout the leaf. This spatial pattern was clearly demonstrated using Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) [

64] underscoring the combined influence of developmental gradients and elemental properties on the metal distribution at the organ level.

Advanced synchrotron-based bioimaging techniques have revealed significant tissue-specific biochemical specialisation in the leaves of hyperaccumulating

Noccaea species. For instance, Synchrotron Radiation Fourier Transform Infrared (SR-FTIR) spectroscopy and Low-Energy X-ray Fluorescence (LEXRF) microscopy demonstrated that, besides vacuoles [

65], Zn is also sequestered in the thickened cell walls of epidermal cells in

N. praecox, where it is co-localised with lignin and pectin [

66]. These findings support the “egg-box” model of pectin–metal binding [

67]. Meanwhile, Cd preferentially accumulates in the mesophyll at high soil Zn levels, as confirmed by micro-Particle Induced X-ray Emission (μ-PIXE) [

26,

68] and in vacuoles in low Zn environment as seen by Synchrotron micro-X-ray Fluorescence (SR-μ-XRF) [

27]. These contrasting accumulation patterns suggest that mesophyll tissues serve as key sinks for Cd, while specialised epidermal compartments help to immobilise Zn, thereby limiting its cytotoxic effects.

Importantly, the spatial organisation of these metals and associated biochemical barriers, such as lignified or pectin-enriched walls, likely plays a dual role—not only in metal detoxification but also in shaping the leaf microbiome. Recent studies indicate that physical and chemical leaf traits such as pH, stomatal density, trichome presence, and even surface roughness can significantly influence microbial colonisation on leaf surfaces [

69]. In

N. caerulescens growing in metalliferous soils, highly specialised strains of

Pseudomonas have been found to dominate the phyllosphere microbiome [

70]. These findings suggest that the micro-environmental conditions created by metal compartmentalisation may act as a spatial and chemical filter, permitting colonisation only by metal-tolerant or symbiotically adapted microbes.

Despite compelling physiological and ecological evidence, the relationship between leaf elemental microarchitecture and microbiome spatial distribution remains unexplored. No published studies have yet integrated spatially resolved metagenomics or Fluorescence In Situ Hybridisation (FISH) with metal mapping to examine how localised chemical environments influence microbial community structure in the phyllosphere of hyperaccumulators. Such research could provide critical insights into the co-adaptive strategies of plants and microbes under extreme environmental pressures.

Future directions should include the use of correlative imaging approaches, such as X-ray computed tomography (XCT), SR-μ-XRF, LA-ICP-MS, and confocal Raman microscopy, alongside high-resolution microbiome profiling. Integrating these tools could help uncover how micro-niches within leaves facilitate or restrict microbial colonisation, leading to a better understanding of plant–microbe–metal interactions in hyperaccumulating systems.

6. Specific Features in the Roots of Noccaea Species Affect Microbial Composition and Metal Uptake

Roots of

N. caerulescens exhibit distinct anatomical specialisations, including peri-endodermal cell wall thickenings that form on the radial and inner tangential walls of cells adjacent to the endodermis. These structures, which resemble a “half-moon” or letter “C”, were first described by Zelko et al 2008 [

71] and later characterised using Raman spectroscopy as being rich in cellulose and lignin, with inner surfaces enriched in pectin [

16]. In addition to providing mechanical support, these thickened cell walls likely function as a selective barrier, immobilising excess metals and restricting their movement toward the central vascular tissues.

Fungal entry into roots is further limited by suberin lamellae in the endodermis. However, in

A. thaliana, it has been demonstrated that beneficial colonisation by

Colletotrichum tofieldiae under phosphate-deficient conditions depends on the presence of unsuberized endodermal passage cells [

72]. These passage cells primarily facilitate the movement of elements and signalling molecules between root layers [

73,

74] and may also serve as entry points for endophytic microbes. Remarkably, some evidence suggests that internalised microbes can be digested within root cells to release nitrogen that is then transported to the shoots [

75].

Plant–microbe interactions in the rhizosphere are shaped by structural traits as well as by hormonal signalling. Specific bacteria can suppress abscisic acid signalling, altering the development of root diffusion barriers and indirectly influencing microbiome composition and plant stress responses [

76,

77]. In Brassicaceae roots, dominant fungal taxa typically belong to Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, while Glomeromycotina are generally present at low abundance [

78]. Notably, fungal communities associated with metal hyperaccumulating

N. caerulescens and

N. goesingensis include members of Dothideomycetes, Sordariomycetes, Eurotiomycetes, and Leotiomycetes, many of which promote plant growth and nickel accumulation [

60].

Comparative studies show that the root-associated microbiomes of

N. praecox and

N. caerulescens, even when collected from the same metalliferous site, exhibit no significant differences in overall structure, implying that local soil microbial communities heavily influence microbiome assembly [

61]. However,

Noccaea brachypetala, another hyperaccumulator, displays increased bacterial species richness and relative abundance of taxa associated with metal tolerance, suggesting microbial co-selection for both phytoremediation support and enhanced nutrient acquisition [

58].

The mycorrhizal status of

Noccaea species—and Brassicaceae more broadly—remains controversial, primarily because genomic analyses have revealed a consistent absence or degeneration of key genes required for AM symbiosis [

17,

79]. Although occasional root colonisation by AM fungi has been observed under specific conditions, these associations are typically rudimentary or facultative and often lack functional arbuscule formation. The Brassicaceae family, including

A. thaliana, is known to lack several essential components of the canonical “symbiosis toolkit” likely due to gene loss or pseudogenisation following ancient whole-genome duplication events [

80]. Additionally, the presence of glucosinolate biosynthesis pathways —which produce antimicrobial compounds—further inhibits functional mycorrhisation in this lineage. Consequently, while some

Noccaea species may occasionally host AM fungi, e.g. during the flowering period [

81,

82], the majority of research supports the classification of this group as primarily non-mycorrhizal. A recent high-throughput sequencing, however, identified Glomeromycetes in the roots of

N. caerulescens and

N. praecox, comprising up to 9% of fungal taxa [

61]. These results were supported by successful colonisation of inoculated roots with monospore Glomeromycotina cultures and subsequent elemental shifts under controlled conditions [

21,

83], pointing to a context-dependent facultative mycorrhizal relationship.

In Noccaea species, specialised anatomical features such as peri-endodermal thickenings and endodermal suberisation influence metal sequestration as well as microbial entry and community structure. Root-associated microbiota are shaped by intrinsic plant traits, environmental filtering in metalliferous soils, and potential symbiotic dynamics involving both fungi and bacteria. The ambiguous but emerging role of mycorrhizal fungi in Noccaea highlights the need for integrated approaches—combining structural imaging, metagenomics, and functional assays—to unravel the multifaceted interactions between roots, metals, and microbes. Such insights are pivotal for leveraging plant–microbe partnerships in sustainable phytoremediation and adaptation to extreme edaphic conditions.

7. Glucosinolates

Genome expansion in plants has been associated with alterations in secondary metabolite pathways, which can impact both microbial recruitment and defence signalling. In Brassicaceae, whole-genome duplication events followed by the silencing or loss of duplicated gene copies are believed to have facilitated gene neofunctionalisation, accelerating the evolution of glucosinolate biosynthesis genes [

8,

12,

84]. Glucosinolates, a hallmark group of secondary metabolites in Brassicaceae, play a central role in defence against pathogens and herbivores by producing toxic isothiocyanates upon hydrolysis [

85,

86].

In

N. caerulescens, significant intraspecific variation in both glucosinolate composition and concentration has been reported [

87], with seasonal patterns showing increased shoot and decreased root glucosinolate levels during flowering [

82,

88]. In

N. praecox, indolyl-glucosinolates dominate in the shoots, whereas roots contain approximately equal proportions of indolyl- and alkyl-glucosinolates [

89]. These chemotypes may influence microbial colonisation in a tissue-specific manner.

Recent studies indicate that glucosinolates shape microbial communities through selective pressures. For example, allyl-glucosinolates have been shown to enrich specific bacterial taxa in the phyllosphere of

A. thaliana [

90]. Moreover, the indolic glucosinolate pathway has been implicated in suppressing AM colonisation in non-host Brassicaceae [

91]. In this context, the expression of transcription factors regulating aliphatic, but not indolic, glucosinolate biosynthesis in the roots of

N. caerulescens ecotype Ganges may be a key factor in shaping its rhizosphere microbial community [

59].

Beyond plant-driven biosynthesis, microbial interactions with glucosinolates further shape community structure. Bacterial myrosinase specificity influences glucosinolate breakdown and can affect community composition, especially when coupled with metabolic cross-feeding between microbial taxa [

90]. Some fungal endophytes and soil fungi can metabolise siringin as a carbon source, although they remain sensitive to isothiocyanates [

92]. Additionally,

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum was recently found to detoxify isothiocyanates using a specific hydrolase, suggesting microbial adaptation to these potent compounds [

93].

Glucosinolates in

Noccaea species serve as potent chemical defences and as ecological gatekeepers that modulate microbial colonisation in a genotype-, tissue-, and environment-specific manner. Their biosynthesis is shaped by genome evolution and selective pressures, resulting in structurally diverse compounds with distinct effects on microbial communities. Recent studies show that specific glucosinolate classes—particularly aliphatic and indolic types—can differentially influence bacterial and fungal assemblages in roots and leaves [

90,

91]. However, the mechanistic pathways underlying these interactions remain largely unresolved. To fully understand how glucosinolates structure the microbiome, future research should integrate metabolomic profiling, transcriptomics, and spatially resolved microbial community analyses. Such interdisciplinary approaches will elucidate how secondary metabolites mediate plant-microbe interactions, particularly under the extreme conditions of metal-rich soils.

8. Conclusions and Further Directions

Noccaea species provide a powerful model to explore how genomic, structural, and chemical traits of plants influence microbial assembly in extreme environments such as metal-contaminated soils. Their small genome size, metal hyperaccumulation capacity, specialised leaf and root anatomy, and glucosinolate profiles act in concert to modulate root and leaf microbiomes, potentially selecting for metal-tolerant and functionally beneficial microbes. Although evidence supports a tight coupling between plant traits and microbial composition, the precise mechanisms—particularly the roles of spatial metal distribution, facultative mycorrhisation, and glucosinolate specificity—remain poorly understood. Future research should adopt integrative, multidisciplinary approaches combining genomics, bioimaging, metabolomics, and spatially resolved microbiome profiling to uncover the dynamic interplay between plant adaptation and microbial community structure, with implications for phytoremediation and ecological resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, MR; writing—original draft preparation, MR, VB, JM, ML, PP, TP, KVM; writing—review and editing, KVM.; visualisation, MR; supervision, MR, KVM; project administration, MR, KVM; funding acquisition, MR, KVM All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

The authors receive financial support from the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency: research core funding No. P1-0212, project funding (J1-3014, J1-50014, J7-60126, J4-3091, N4-0346) and Young researcher projects, Valentina Bočaj and Teja Pelko.

Data Availability Statement

Plant names were adopted according to Flora Europaea (

https://ww2.bgbm.org/EuroPlusMed/query.asp). Information on DNA amount was drawn from the Plant DNA C-value database, Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew (

https://ww2.bgbm.org/EuroPlusMed/query.asp). Data on mycorrhizal colonisation is contained in the articles (Regvar et al., 2003, 2006). The final table is provided in the Appendix. The images were prepared by Biorender. AI was used to find references (Elicit) and for text editing (Grammarly, ChatGPT).

Acknowledgements

The manuscript is dedicated to Prof. Hermann Bothe.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AM |

Arbuscular mycorrhiza |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| HMA4 |

Heavy Metal ATPase 4 |

| LA-ICP-MS |

Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry |

| LEXRF |

Low-Energy X-Ray-Fluorescence |

| NAS2 |

Nicotianamine Synthase 2 |

| NcHMA4 |

Noccaea caerulescens Heavy Metal ATPase 4 |

| NcMTP1 |

Noccaea caerulescens Metal Tolerance Protein 1 |

| PIXE |

Particle-Induced X-ray Emission |

| SR-μ-XRF |

Synchrotron micro X-Ray-Fluorescence |

| YSL3 |

Yellow Stripe-Like 3 |

| XCT |

X-ray computed tomography |

| WDG |

whole-genome duplication |

| ZIFL1 |

Zinc-Induced Facilitator-Like 1 |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Brassicaceae clades [

12] with their corresponding DNA amounts, available at the Plant DNA C-values database [

38]. Data corrected according to Flora Europaea (The Euro+Med Plantbase Project,

https://ww2.bgbm.org/EuroPlusMed/query.asp).

Table A1.

Brassicaceae clades [

12] with their corresponding DNA amounts, available at the Plant DNA C-values database [

38]. Data corrected according to Flora Europaea (The Euro+Med Plantbase Project,

https://ww2.bgbm.org/EuroPlusMed/query.asp).

| No |

Clade |

Genus |

Species |

DNA Amount |

Original Reference

See https://ww2.bgbm.org/EuroPlusMed/query.asp

|

Clade average DNA Amount |

| |

|

|

|

1C (pg) |

|

1C (pg) |

| 1 |

Clade A |

Capsella |

rubella |

0.22 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 2 |

Clade A |

Capsella |

bursa-pastoris |

0.4 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 3 |

Clade A |

Pachycladon |

exilis |

0.44 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 4 |

Clade A |

Pachycladon |

fastigiata |

0.51 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 5 |

Clade A |

Pachycladon |

novae-zelandiae |

0.55 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 6 |

Clade A |

Turritis |

glabra |

0.24 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 7 |

Clade A |

Arabidopsis |

thaliana |

0.16 |

Bennett et al.,2003 |

|

| 8 |

Clade A |

Arabidopsis |

arenosa |

0.2 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 9 |

Clade A |

Arabidopsis |

neglecta |

0.2 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 10 |

Clade A |

Arabidopsis |

halleri |

0.24 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 11 |

Clade A |

Arabidopsis |

korshynskyi |

0.25 |

Nagl et al.,1983 |

|

| 12 |

Clade A |

Arabidopsis |

lyrata |

0.25 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 13 |

Clade A |

Arabidopsis |

cebennensis |

0.29 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 14 |

Clade A |

Arabidopsis |

pumila |

0.34 |

Houben et al.,2003 |

|

| 15 |

Clade A |

Arabidopsis |

suecica |

0.35 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 16 |

Clade A |

Arabidopsis |

arenosa |

0.39 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 17 |

Clade A |

Arabidopsis |

wallichii |

0.4 |

Houben et al.,2003 |

|

| 18 |

Clade A |

Arabidopsis |

neglecta |

0.4 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 19 |

Clade A |

Arabidopsis |

thaliana |

0.44 |

Schmuths et al.,2004 |

|

| 20 |

Clade A |

Arabidopsis |

lyrata |

0.45 |

Dart et al.,2004 |

|

| 21 |

Clade A |

Arabidopsis |

kamchatica |

0.52 |

Wolf et al.,2014 |

|

| 22 |

Clade A |

Physaria |

gracilis |

0.26 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 23 |

Clade A |

Physaria |

ovalifolia |

0.43 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 24 |

Clade A |

Physaria |

arctica |

0.69 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 25 |

Clade A |

Physaria |

didymocarpa |

2.23 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 26 |

Clade A |

Physaria |

bellii |

2.34 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 27 |

Clade A |

Erysimum |

sylvestre |

0.28 |

Vidic et al.,2009 |

|

| 28 |

Clade A |

Erysimum |

duriaei |

0.47 |

Loureiro et al.,2013 |

|

| 29 |

Clade A |

Erysimum |

scoparium |

0.54 |

Suda et al.,2003 |

|

| 30 |

Clade A |

Erysimum |

bicolor |

0.58 |

Suda et al.,2003 |

|

| 31 |

Clade A |

Erysimum |

goniocaulon |

0.69 |

Bou Dagher-Kharrat et al.,2013 |

|

| 32 |

Clade A |

Erysimum |

bicolor |

0.76 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 33 |

Clade A |

Erysimum |

cheiranthoides |

0.83 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 34 |

Clade A |

Erysimum |

diffusum |

0.88 |

Pustahija et al.,2013 |

|

| 35 |

Clade A |

Rorippa |

lipizensis |

0.22 |

Vallès et al.,2014 |

|

| 36 |

Clade A |

Rorippa |

sylvestris |

0.48 |

Pustahija et al.,2013 |

|

| 37 |

Clade A |

Rorippa |

palustris |

0.54 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 38 |

Clade A |

Rorippa |

nasturtium-aquaticum |

0.7 |

Kenton and Owens,1988 |

|

| 39 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

impatiens |

0.21 |

Johnston et al.,2005 |

|

| 40 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

hirsuta |

0.23 |

Johnston et al.,2005 |

|

| 41 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

amara |

0.24 |

Hanson et al.,2002 |

|

| 42 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

glauca |

0.28 |

Pustahija et al.,2013 |

|

| 43 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

chelidonia |

0.36 |

Kubešová et al.,2010 |

|

| 44 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

schinziana |

0.68 |

Marhold et al.,2010 |

|

| 45 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

yezoensis |

0.7 |

Marhold et al.,2010 |

|

| 46 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

amaraeiformis |

0.71 |

Marhold et al.,2010 |

|

| 47 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

valida |

0.71 |

Marhold et al.,2010 |

|

| 48 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

yezoensis |

0.87 |

Marhold et al.,2010 |

|

| 49 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

flexuosa |

0.9 |

Mowforth and Grime,1989 |

|

| 50 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

yezoensis |

0.99 |

Marhold et al.,2010 |

|

| 51 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

schinziana |

1 |

Marhold et al.,2010 |

|

| 52 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

torrentis |

1.13 |

Marhold et al.,2010 |

|

| 53 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

yezoensis |

1.24 |

Marhold et al.,2010 |

|

| 54 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

asarifolia |

1.34 |

Lihova et al.,2006 |

|

| 55 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

diphylla |

1.62 |

Sonnier,2016 |

|

| 56 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

pratensis |

1.70 |

Band,1984 |

|

| 57 |

Clade A |

Cardamine |

concatenata |

3.25 |

Bai et al.,2012 |

0.67 |

| 1 |

Clade B |

Raphanus |

sativus |

0.6 |

Dolezel et al.,1992 |

|

| 2 |

Clade B |

Raphanus |

sativus |

1.50 |

Olszewska and Osiecka,1983 |

|

| 3 |

Clade B |

Hirschfeldia |

incana |

0.52 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 4 |

Clade B |

Brassica |

hirta |

0.51 |

Arumuganathan and Earle,1991 |

|

| 5 |

Clade B |

Brassica |

tournefortii |

0.6 |

Nagpal et al.,1996 |

|

| 6 |

Clade B |

Brassica |

campestris |

0.6 |

Bennett et al.,1976 |

|

| 7 |

Clade B |

Brassica |

nigra |

0.8 |

Verma and Rees,1974 |

|

| 8 |

Clade B |

Brassica |

oleracea |

0.8 |

Olszewska and Osiecka,1983 |

|

| 9 |

Clade B |

Brassica |

rapa |

0.8 |

Ingle et al.,1975 |

|

| 10 |

Clade B |

Brassica |

napus |

1.10 |

Greilhuber,1988 |

|

| 11 |

Clade B |

Brassica |

juncea |

1.50 |

Verma and Rees,1974 |

|

| 12 |

Clade B |

Brassica |

carinata |

1.60 |

Verma and Rees,1974 |

|

| 13 |

Clade B |

Sinapis |

arvensis |

0.38 |

Arumuganathan and Earle,1991 |

|

| 14 |

Clade B |

Sinapis |

alba |

0.50 |

Bennett MD, Smith JB, Heslop-Harrison,1982 |

|

| 15 |

Clade B |

Cakile |

maritima |

0.68 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 16 |

Clade B |

Cakile |

edentula |

0.84 |

Bai et al.,2012 |

|

| 17 |

Clade B |

Sisymbrium |

officinale |

0.24 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 18 |

Clade B |

Sisymbrium |

loeselii |

0.24 |

Kubešová et al.,2010 |

|

| 19 |

Clade B |

Sisymbrium |

altissimum |

0.26 |

Kubešová et al.,2010 |

|

| 20 |

Clade B |

Sisymbrium |

orientale |

0.31 |

Johnston et al.,2005 |

|

| 21 |

Clade B |

Sisymbrium |

austriacum |

0.36 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 22 |

Clade B |

Sisymbrium |

irio |

0.53 |

Johnston et al.,2005 |

|

| 23 |

Clade B |

Sisymbrium |

strictissimum |

0.7 |

Kubešová et al.,2010 |

|

| 24 |

Clade B |

Thlaspi |

ceratocarpum |

0.43 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 25 |

Clade B |

Thlaspi |

arvense |

0.52 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 26 |

Clade B |

Alliaria |

petiolata |

1.35 |

Barow & Meister,2003 |

|

| 27 |

Clade B |

Calepina |

irregularis |

0.21 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 28 |

Clade B |

Noccaea |

alpestris |

0.24 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 29 |

Clade B |

Noccaea |

alpestris |

0.2 |

Band,1984 |

|

| 30 |

Clade B |

Noccaea |

caerulescens |

0.34 |

Peer et al.,2006 |

|

| 31 |

Clade B |

Noccaea |

montana |

0.29 |

Peer et al.,2006 |

|

| 32 |

Clade B |

Noccaea |

goesingensis |

0.5 |

Siljak-Yakovlev et al.,2010 |

|

| 33 |

Clade B |

Noccaea |

oxyceras |

0.34 |

Peer et al.,2003 |

|

| 34 |

Clade B |

Noccaea |

praecox |

0.26 |

Temsch et al.,2010 |

|

| 35 |

Clade B |

Noccaea |

perfoliata |

0.31 |

Peer et al.,2006 |

|

| 36 |

Clade B |

Noccaea |

rosularis |

0.32 |

Peer et al.,2003 |

|

| 37 |

Clade B |

Noccaea |

tymphaea |

0.32 |

Peer et al.,2006 |

|

| 38 |

Clade B |

Noccaea |

tymphaea |

0.66 |

Peer et al.,2006 |

|

| 39 |

Clade B |

Noccaea |

violascens |

0.31 |

Peer et al.,2003 |

|

| 40 |

Clade B |

Kernera |

saxatilis |

0.2 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

0.57 |

| 1 |

Clade C |

Iberis |

sempervirens |

0.56 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 2 |

Clade C |

Iberis |

gibraltarica |

0.57 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 3 |

Clade C |

Lobularia |

libyaca |

0.53 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 4 |

Clade C |

Lobularia |

canariensis |

0.57 |

Suda et al.,2003 |

|

| 5 |

Clade C |

Cochlearia |

aucheri |

0.3 |

Peer et al.,2003 |

|

| 6 |

Clade C |

Cochlearia |

sempervivum |

0.33 |

Peer et al.,2003 |

|

| 7 |

Clade C |

Cochlearia |

pyrenaica |

0.4 |

Krisai and Greilhuber,1997 |

|

| 8 |

Clade C |

Cochlearia |

danica |

0.7 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 9 |

Clade C |

Cochlearia |

officinalis |

0.75 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 10 |

Clade C |

Cochlearia |

tatrae |

1.04 |

Kochjarova et al.,2006 |

|

| 11 |

Clade C |

Cochlearia |

borzaeana |

1.41 |

Kochjarova et al.,2006 |

|

| 12 |

Clade C |

Lunaria |

rediviva |

0.37 |

Pustahija et al.,2013 |

|

| 13 |

Clade C |

Lunaria |

biennis |

1.85 |

Zonneveld et al.,2005 |

|

| 14 |

Clade C |

Biscutella |

auriculata |

0.69 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 15 |

Clade C |

Biscutella |

didyma |

0.79 |

Peer et al.,2003 |

|

| 16 |

Clade C |

Biscutella |

laevigata |

1.83 |

Temsch et al.,2010 |

0.79 |

| 1 |

Clade D |

Alyssum |

saxatile |

0.65 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 2 |

Clade D |

Alyssum |

markgrafii |

0.54 |

Pustahija et al.,2013 |

|

| 3 |

Clade D |

Alyssum |

murale |

0.58 |

Siljak-Yakovlev et al.,2010 |

|

| 4 |

Clade D |

Alyssum |

saxatile |

0.65 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 5 |

Clade D |

Berteroa |

incana |

0.71 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

0.63 |

| 1 |

Clade E |

Parrya |

nudicaulis |

1.08 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 2 |

Clade E |

Chorispora |

tenella |

0.35 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 3 |

Clade E |

Bunias |

erucago |

2.07 |

Greilhuber and Obermayer,1999 |

|

| 4 |

Clade E |

Bunias |

orientalis |

2.59 |

Greilhuber and Obermayer,1999 |

|

| 5 |

Clade E |

Hesperis |

matronalis |

3.8 |

Kubešová et al.,2010 |

1.98 |

| 1 |

Clade F |

Aethionema |

saxatile |

0.62 |

Pustahija et al.,2013 |

|

| 2 |

Clade F |

Aethionema |

grandiflorum |

0.71 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 3 |

Clade F |

Aethionema |

schistosum |

0.71 |

Lysák et al.,2009 |

|

| 4 |

Clade F |

Aethionema |

cordifolium |

2.14 |

Bou Dagher-Kharrat et al.,2013 |

1.05 |

References

- Turner, T.R.; James, E.K.; Poole, P.S. The Plant Microbiome. Genome Biol 2013, 14, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.E.; Tringe, S.G.; Sa, T.; Singh, B.K. Plant–Microbiome Interactions: From Community Assembly to Plant Health. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2020 18:11 2020, 18, 607–621. [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, C.R.; Salas-González, I.; Conway, J.M.; Finkel, O.M.; Gilbert, S.; Russ, D.; Teixeira, P.J.P.L.; Dangl, J.L. The Plant Microbiome: From Ecology to Reductionism and Beyond. Annu Rev Microbiol 2020, 74, 81–100. [CrossRef]

- Reeves, R.D.; Baker, A.J.M.; Jaffré, T.; Erskine, P.D.; Echevarria, G.; van der Ent, A. A Global Database for Plants That Hyperaccumulate Metal and Metalloid Trace Elements. New Phytologist 2018, 218, 407–411. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shehbaz, I.A.; Beilstein, M.A.; Kellogg, E.A. Systematics and Phylogeny of the Brassicaceae (Cruciferae): An Overview. Plant Systematics and Evolution 2006, 259, 89–120. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shehbaz, I.A. A Synopsis of the Genus Noccaea (Coluteocarpeae, Brassicaceae). Harv Pap Bot 2014, 19, 25–51. [CrossRef]

- Franzke, A.; German, D.; Al-Shehbaz, I.A.; Mummenhoff, K. Arabidopsis Family Ties: Molecular Phylogeny and Age Estimates in Brassicaceae. Taxon 2009, 58, 425–437. [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, N.; Wolf, E.M.; Lysak, M.A.; Koch, M.A. A Time-Calibrated Road Map of Brassicaceae Species Radiation and Evolutionary History. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 2770–2784. [CrossRef]

- Mandáková, T.; Joly, S.; Krzywinski, M.; Mummenhoff, K.; Lysaka, M.A. Fast Diploidization in Close Mesopolyploid Relatives of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 2277–2290. [CrossRef]

- Kagale, S.; Robinson, S.J.; Nixon, J.; Xiao, R.; Huebert, T.; Condie, J.; Kessler, D.; Clarke, W.E.; Edger, P.P.; Links, M.G.; et al. Polyploid Evolution of the Brassicaceae during the Cenozoic Era. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 2777–2791. [CrossRef]

- Van De Peer, Y.; Mizrachi, E.; Marchal, K. The Evolutionary Significance of Polyploidy. Nature Reviews Genetics 2017 18:7 2017, 18, 411–424. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; Sun, R.; Hu, Y.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, N.; Cai, L.; Zhang, Q.; Koch, M.A.; Al-Shehbaz, I.; Edger, P.P.; et al. Resolution of Brassicaceae Phylogeny Using Nuclear Genes Uncovers Nested Radiations and Supports Convergent Morphological Evolution. Mol Biol Evol 2016, 33, 394–412. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Han, X. Traits-Based Approach: Leveraging Genome Size in Plant–Microbe Interactions. Trends Microbiol 2024, 32, 333–341. [CrossRef]

- Sotelo, T.; Lema, M.; Soengas, P.; Cartea, M.E.; Velasco, P. In Vitro Activity of Glucosinolates and Their Degradation Products against Brassica-Pathogenic Bacteria and Fungi. Appl Environ Microbiol 2015, 81, 432–440. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Massih, R.M.; Debs, E.; Othman, L.; Attieh, J.; Cabrerizo, F.M. Glucosinolates, a Natural Chemical Arsenal: More to Tell than the Myrosinase Story. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1130208. [CrossRef]

- Kováč, J.; Lux, A.; Soukup, M.; Weidinger, M.; Gruber, D.; Lichtscheidl, I.; Vaculík, M. A New Insight on Structural and Some Functional Aspects of Peri-Endodermal Thickenings, a Specific Layer in Noccaea Caerulescens Roots. Ann Bot 2020, 126, 423–434. [CrossRef]

- Trautwig, A.N.; Jackson, M.R.; Kivlin, S.N.; Stinson, K.A. Reviewing Ecological Implications of Mycorrhizal Fungal Interactions in the Brassicaceae. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1269815. [CrossRef]

- Pongrac, P.; Sonjak, S.; Vogel-Mikuš, K.; Kump, P.; Nečemer, M.; Regvar, M. Roots of Metal Hyperaccumulating Population of Thlaspi Praecox (Brassicaceae) Harbour Arbuscular Mycorrhizal and Other Fungi under Experimental Conditions. Int J Phytoremediation 2009, 11, 347–359. [CrossRef]

- Vogel-Mikuš, K.; Drobne, D.; Regvar, M. Zn, Cd and Pb Accumulation and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Colonisation of Pennycress Thlaspi Praecox Wulf. (Brassicaceae) from the Vicinity of a Lead Mine and Smelter in Slovenia. Environmental Pollution 2005, 133, 233–242. [CrossRef]

- Regvar, M.; Vogel-Mikuš, K.; Kugonič, N.; Turk, B.; Batič, F. Vegetational and Mycorrhizal Successions at a Metal Polluted Site: Indications for the Direction of Phytostabilisation? Environmental Pollution 2006, 144, 976–984. [CrossRef]

- Vogel-Mikuš, K.; Pongrac, P.; Kump, P.; Nečemer, M.; Regvar, M. Colonisation of a Zn, Cd and Pb Hyperaccumulator Thlaspi Praecox Wulfen with Indigenous Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungal Mixture Induces Changes in Heavy Metal and Nutrient Uptake. Environmental Pollution 2006, 139, 362–371. [CrossRef]

- Zunk, K.; Mummenhoff, K.; Koch, M.; Hurka, H. Phylogenetic Relationships of Thlaspi s.I. (Subtribe Thlaspidinae, Lepidieae) and Allied Genera Based on Chloroplast DNA Restriction- Site Variation. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 1996, 92, 375–381. [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Mummenhoff, K. Thlaspi s.Str. (Brassicaceae) versus Thlaspi s.l.: Morphological and Anatomical Characters in the Light of ITS NrDNA Sequence Data. Plant Systematics and Evolution 2001, 227, 209–225. [CrossRef]

- Krämer, U. Metal Hyperaccumulation in Plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2010, 61, 517–534. [CrossRef]

- Fasani, E.; Zamboni, A.; Sorio, D.; Furini, A.; DalCorso, G. Metal Interactions in the Ni Hyperaccumulating Population of Noccaea Caerulescens Monte Prinzera. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12, 1537. [CrossRef]

- Vogel-Mikuš, K.; Regvar, M.; Mesjasz-Przybyłowicz, J.; Przybyłowicz, W.J.; Simčič, J.; Pelicon, P.; Budnar, M. Spatial Distribution of Cadmium in Leaves of Metal Hyperaccumulating Thlaspi Praecox Using Micro-PIXE. New Phytologist 2008, 179, 712–721. [CrossRef]

- Koren, Š.; Arčon, I.; Kump, P.; Nečemer, M.; Vogel-Mikuš, K. Influence of CdCl2 and CdSO4 Supplementation on Cd Distribution and Ligand Environment in Leaves of the Cd Hyperaccumulator Noccaea (Thlaspi) Praecox. Plant Soil 2013, 370, 125–148. [CrossRef]

- Likar, M.; Pongrac, P.; Vogel-Mikuš, K.; Regvar, M. Molecular Diversity and Metal Accumulation of Different Thlaspi Praecox Populations from Slovenia. Plant Soil 2010, 330, 195–205. [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Al-Shehbaz, I.A. Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Evaluation of the American “Thlaspi” Species: Identity and Relationship to the Eurasian Genus Noccaea (Brassicaceae). Syst Bot 2004, 29, 375–384. [CrossRef]

- Mandáková, T.; Li, Z.; Barker, M.S.; Lysak, M.A. Diverse Genome Organization Following 13 Independent Mesopolyploid Events in Brassicaceae Contrasts with Convergent Patterns of Gene Retention. The Plant Journal 2017, 91, 3–21. [CrossRef]

- Lysak, M.A.; Koch, M.A.; Pecinka, A.; Schubert, I. Chromosome Triplication Found across the Tribe Brassiceae. Genome Res 2005, 15, 516–525. [CrossRef]

- Vision, T.J.; Brown, D.G.; Tanksley, S.D. The Origins of Genomic Duplications in Arabidopsis. Science (1979) 2000, 290, 2114–2117. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.S.; Pepper, A.E.; Hall, A.E.; Chen, Z.J.; Hodnett, G.; Drabek, J.; Lopez, R.; Price, H.J. Evolution of Genome Size in Brassicaceae. Ann Bot 2005, 95, 229–235. [CrossRef]

- Mandáková, T.; Singh, V.; Krämer, U.; Lysak, M.A. Genome Structure of the Heavy Metal Hyperaccumulator Noccaea Caerulescens and Its Stability on Metalliferous and Nonmetalliferous Soils. Plant Physiol 2015, 169, 674–689. [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.A.; Molinari, N.A.; Petrov, D.A. The Large Genome Constraint Hypothesis: Evolution, Ecology and Phenotype. Ann Bot 2005, 95, 177–190. [CrossRef]

- Temsch, E.M.; Temsch, W.; Ehrendorfer-Schratt, L.; Greilhuber, J. Heavy Metal Pollution, Selection, and Genome Size: The Species of the Žerjav Study Revisited with Flow Cytometry. J Bot 2010, 2010, 596542. [CrossRef]

- Vidic, T.; Greilhuber, J.; Vilhar, B.; Dermastia, M. Selective Significance of Genome Size in a Plant Community with Heavy Metal Pollution. Ecological Applications 2009, 19, 1515–1521. [CrossRef]

- Leitch IJ, J.E.P.J.H.O.B.M. release 7. 1, A. 2019 Plant DNA C-Values Database | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew Available online: https://cvalues.science.kew.org/ (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Rodríguez-Gijón, A.; Nuy, J.K.; Mehrshad, M.; Buck, M.; Schulz, F.; Woyke, T.; Garcia, S.L. A Genomic Perspective Across Earth’s Microbiomes Reveals That Genome Size in Archaea and Bacteria Is Linked to Ecosystem Type and Trophic Strategy. Front Microbiol 2022, 12, 761869. [CrossRef]

- Greilhuber, J.; Borsch, T.; Müller, K.; Worberg, A.; Porembski, S.; Barthlott, W. Smallest Angiosperm Genomes Found in Lentibulariaceae, with Chromosomes of Bacterial Size. Plant Biol (Stuttg) 2006, 8, 770–777. [CrossRef]

- Pellicer, J.; Fay, M.F.; Leitch, I.J. The Largest Eukaryotic Genome of Them All? Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 2010, 164, 10–15. [CrossRef]

- Francis, D.; Davies, M.S.; Barlow, P.W. A Strong Nucleotypic Effect on the Cell Cycle Regardless of Ploidy Level. Ann Bot 2008, 101, 747–757. [CrossRef]

- D’Ario, M.; Tavares, R.; Schiessl, K.; Desvoyes, B.; Gutierrez, C.; Howard, M.; Sablowski, R. Cell Size Controlled in Plants Using DNA Content as an Internal Scale. Science 2021, 372, 1176–1181. [CrossRef]

- Segraves, K.A. The Effects of Genome Duplications in a Community Context. New Phytologist 2017, 215, 57–69. [CrossRef]

- Regvar, M.; Vogel, K.; Irgel, N.; Hildebrandt, U.; Wilde, P.; Bothe, H. Colonization of Pennycresses (Thlaspi Spp.) of the Brassicaceae by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi; 2003; Vol. 160;.

- Orłowska, E.; Zubek, S.; Jurkiewicz, A.; Szarek-Łukaszewska, G.; Turnau, K. Influence of Restoration on Arbuscular Mycorrhiza of Biscutella Laevigata L. (Brassicaceae) and Plantago Lanceolata L. (Plantaginaceae) from Calamine Spoil Mounds. Mycorrhiza 2002, 12, 153–159. [CrossRef]

- Trouvelot, A.; Kough, J.L.; Gianinazzi-Pearson, V. Du Taux de Mycorhization VA d’un Système Radiculaire. Recherche de Méthodes d’estimation Ayant Une Signification Fonctionnelle. Mycorhizes: Physiologie et génétique 1986.

- Ancousture, J.; Durand, A.; Blaudez, D.; Benizri, E. A Reduced but Stable Core Microbiome Found in Seeds of Hyperaccumulators. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 887, 164131. [CrossRef]

- Levy, A.; Salas Gonzalez, I.; Mittelviefhaus, M.; Clingenpeel, S.; Herrera Paredes, S.; Miao, J.; Wang, K.; Devescovi, G.; Stillman, K.; Monteiro, F.; et al. Genomic Features of Bacterial Adaptation to Plants. Nature Genetics 2017 50:1 2017, 50, 138–150. [CrossRef]

- van der Ent, A.; Spiers, K.M.; Brueckner, D.; Echevarria, G.; Aarts, M.G.M.; Montargès-Pelletier, E. Spatially-Resolved Localization and Chemical Speciation of Nickel and Zinc in Noccaea Tymphaea and Bornmuellera Emarginata. Metallomics 2019. [CrossRef]

- Hanikenne, M.; Talke, I.N.; Haydon, M.J.; Lanz, C.; Nolte, A.; Motte, P.; Kroymann, J.; Weigel, D.; Krämer, U. Evolution of Metal Hyperaccumulation Required Cis-Regulatory Changes and Triplication of HMA4. Nature 2008 453:7193 2008, 453, 391–395. [CrossRef]

- Roux, C.; Castric, V.; Pauwels, M.; Wright, S.I.; Saumitou-Laprade, P.; Vekemans, X. Does Speciation between Arabidopsis Halleri and Arabidopsis Lyrata Coincide with Major Changes in a Molecular Target of Adaptation? PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26872. [CrossRef]

- Ó Lochlainn, S.; Bowen, H.C.; Fray, R.G.; Hammond, J.P.; King, G.J.; White, P.J.; Graham, N.S.; Broadley, M.R. Tandem Quadruplication of HMA4 in the Zinc (Zn) and Cadmium (Cd) Hyperaccumulator Noccaea Caerulescens. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17814. [CrossRef]

- Craciun, A.R.; Meyer, C.L.; Chen, J.; Roosens, N.; De Groodt, R.; Hilson, P.; Verbruggen, N. Variation in HMA4 Gene Copy Number and Expression among Noccaea Caerulescens Populations Presenting Different Levels of Cd Tolerance and Accumulation. J Exp Bot 2012, 63, 4179–4189. [CrossRef]

- Clemens, S.; Palmgren, M.G.; Krämer, U. A Long Way Ahead: Understanding and Engineering Plant Metal Accumulation. Trends Plant Sci 2002, 7, 309–315. [CrossRef]

- Hanikenne, M.; Nouet, C. Metal Hyperaccumulation and Hypertolerance: A Model for Plant Evolutionary Genomics. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2011, 14, 252–259. [CrossRef]

- Milner, M.J.; Mitani-Ueno, N.; Yamaji, N.; Yokosho, K.; Craft, E.; Fei, Z.; Ebbs, S.; Clemencia Zambrano, M.; Ma, J.F.; Kochian, L. V. Root and Shoot Transcriptome Analysis of Two Ecotypes of Noccaea Caerulescens Uncovers the Role of NcNramp1 in Cd Hyperaccumulation. The Plant Journal 2014, 78, 398–410. [CrossRef]

- Martos, S.; Gallego, B.; Sáez, L.; López-Alvarado, J.; Cabot, C.; Poschenrieder, C. Characterization of Zinc and Cadmium Hyperaccumulation in Three Noccaea (Brassicaceae) Populations from Non-Metalliferous Sites in the Eastern Pyrenees. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7, 173623. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.F.; Severing, E.I.; te Lintel Hekkert, B.; Schijlen, E.; Aarts, M.G.M. A Comprehensive Set of Transcript Sequences of the Heavy Metal Hyperaccumulator Noccaea Caerulescens. Front Plant Sci 2014, 5, 78115. [CrossRef]

- Ważny, R.; Rozpądek, P.; Domka, A.; Jędrzejczyk, R.J.; Nosek, M.; Hubalewska-Mazgaj, M.; Lichtscheidl, I.; Kidd, P.; Turnau, K. The Effect of Endophytic Fungi on Growth and Nickel Accumulation in Noccaea Hyperaccumulators. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 768, 144666. [CrossRef]

- Bočaj, V.; Pongrac, P.; Grčman, H.; Šala, M.; Likar, M. Rhizobiome Diversity of Field-Collected Hyperaccumulating Noccaea Sp. BMC Plant Biol 2024, 24, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Durand, A.; Sterckeman, T.; Gonnelli, C.; Coppi, A.; Bacci, G.; Leglize, P.; Benizri, E. A Core Seed Endophytic Bacterial Community in the Hyperaccumulator Noccaea Caerulescens across 14 Sites in France. Plant Soil 2021, 459, 203–216. [CrossRef]

- Wolters, H.; Jürgens, G. Survival of the Flexible: Hormonal Growth Control and Adaptation in Plant Development. Nature Reviews Genetics 2009 10:5 2009, 10, 305–317. [CrossRef]

- Callahan, D.L.; Hare, D.J.; Bishop, D.P.; Doble, P.A.; Roessner, U. Elemental Imaging of Leaves from the Metal Hyperaccumulating Plant Noccaea Caerulescens Shows Different Spatial Distribution of Ni, Zn and Cd. RSC Adv 2015, 6, 2337–2344. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, M.D.; Barceló, J.; Poschenrieder, Ch.; Mádico, J.; Hatton, P.; Baker, A.J.M.; Cope, G.H. Localization of Zinc and Cadmium in Thlaspi Caerulescens (Brassicaceae), a Metallophyte That Can Hyperaccumulate Both Metals. J Plant Physiol 1992, 140, 350–355. [CrossRef]

- Regvar, M.; Eichert, D.; Kaulich, B.; Gianoncelli, A.; Pongrac, P.; Vogel-Mikuš, K. Biochemical Characterization of Cell Types within Leaves of Metal-Hyperaccumulating Noccaea Praecox (Brassicaceae). Plant Soil 2013, 373, 157–171. [CrossRef]

- Braccini, I.; Pérez, S. Molecular Basis of Ca2+-Induced Gelation in Alginates and Pectins: The Egg-Box Model Revisited. Biomacromolecules 2001, 2, 1089–1096. [CrossRef]

- Pongrac, P.; Vogel-Mikuš, K.; Vavpetič, P.; Tratnik, J.; Regvar, M.; Simčič, J.; Grlj, N.; Pelicon, P. Cd Induced Redistribution of Elements within Leaves of the Cd/Zn Hyperaccumulator Thlaspi Praecox as Revealed by Micro-PIXE. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B 2010, 268, 2205–2210. [CrossRef]

- Smets, W.; Chock, M.K.; Walsh, C.M.; Vanderburgh, C.Q.; Kau, E.; Lindow, S.E.; Fierer, N.; Koskella, B. Leaf Side Determines the Relative Importance of Dispersal versus Host Filtering in the Phyllosphere Microbiome. mBio 2023, 14, e0111123. [CrossRef]

- Fones, H.N.; McCurrach, H.; Mithani, A.; Smith, J.A.C.; Preston, G.M. Local Adaptation Is Associated with Zinc Tolerance in Pseudomonas Endophytes of the Metal-Hyperaccumulator Plant Noccaea Caerulescens. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2016, 283. [CrossRef]

- Zelko, I.; Lux, A.; Czibula, K. Difference in the Root Structure of Hyperaccumulator Thlaspi Caerulescens and Non-Hyperaccumulator Thlaspi Arvense. Int J Environ Pollut 2008, 33, 123–132. [CrossRef]

- Hiruma, K.; Gerlach, N.; Sacristán, S.; Nakano, R.T.; Hacquard, S.; Kracher, B.; Neumann, U.; Ramírez, D.; Bucher, M.; O’Connell, R.J.; et al. Root Endophyte Colletotrichum Tofieldiae Confers Plant Fitness Benefits That Are Phosphate Status Dependent. Cell 2016, 165, 464–474. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T.G.; Naseer, S.; Ursache, R.; Wybouw, B.; Smet, W.; De Rybel, B.; Vermeer, J.E.M.; Geldner, N. Diffusible Repression of Cytokinin Signalling Produces Endodermal Symmetry and Passage Cells. Nature 2018 555:7697 2018, 555, 529–533. [CrossRef]

- Holbein, J.; Shen, D.; Andersen, T.G. The Endodermal Passage Cell – Just Another Brick in the Wall? New Phytologist 2021, 230, 1321–1328. [CrossRef]

- Paungfoo-Lonhienne, C.; Rentsch, D.; Robatzek, S.; Webb, R.I.; Sagulenko, E.; Näsholm, T.; Schmidt, S.; Lonhienne, T.G.A. Turning the Table: Plants Consume Microbes as a Source of Nutrients. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11915. [CrossRef]

- Durr, J.; Reyt, G.; Spaepen, S.; Hilton, S.; Meehan, C.; Qi, W.; Kamiya, T.; Flis, P.; Dickinson, H.G.; Feher, A.; et al. A Novel Signaling Pathway Required for Arabidopsis Endodermal Root Organization Shapes the Rhizosphere Microbiome. Plant Cell Physiol 2021, 62, 248–261. [CrossRef]

- Salas-González, I.; Reyt, G.; Flis, P.; Custódio, V.; Gopaulchan, D.; Bakhoum, N.; Dew, T.P.; Suresh, K.; Franke, R.B.; Dangl, J.L.; et al. Coordination between Microbiota and Root Endodermis Supports Plant Mineral Nutrient Homeostasis. Science 2021, 371. [CrossRef]

- Maciá-Vicente, J.G.; Nam, B.; Thines, M. Root Filtering, Rather than Host Identity or Age, Determines the Composition of Root-Associated Fungi and Oomycetes in Three Naturally Co-Occurring Brassicaceae. Soil Biol Biochem 2020, 146, 107806. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sinharoy, S.; Bisht, N.C. The Mysterious Non-Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Status of Brassicaceae Species. Environ Microbiol 2023, 25, 917–930. [CrossRef]

- Delaux, P.M.; Radhakrishnan, G. V.; Jayaraman, D.; Cheema, J.; Malbreil, M.; Volkening, J.D.; Sekimoto, H.; Nishiyama, T.; Melkonian, M.; Pokorny, L.; et al. Algal Ancestor of Land Plants Was Preadapted for Symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 13390–13395. [CrossRef]

- Pongrac, P.; Vogel-Mikuš, K.; Poschenrieder, C.; Barceló, J.; Tolrà, R.; Regvar, M. Arbuscular Mycorrhiza in Glucosinolate-Containing Plants: The Story of the Metal Hyperaccumulator Noccaea (Thlaspi) Praecox (Brassicaceae); 2013;.

- Pongrac, P.; Vogel-Mikuš, K.; Regvar, M.; Tolrà, R.; Poschenrieder, C.; Barceló, J. Glucosinolate Profiles Change during the Life Cycle and Mycorrhizal Colonization in a Cd/Zn Hyperaccumulator Thlaspi Praecox (Brassicaceae). J Chem Ecol 2008, 34, 1038–1044. [CrossRef]

- Bočaj, V.; Regvar, M.; Pongrac, P. Linking Microbiome and Hyperaccumulation in Plants. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Song, N.; Zhao, X.; Qi, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, M. Genome Survey Sequencing Provides Clues into Glucosinolate Biosynthesis and Flowering Pathway Evolution in Allotetrapolyploid Brassica Juncea. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Grubb, C.D.; Abel, S. Glucosinolate Metabolism and Its Control. Trends Plant Sci 2006, 11, 89–100. [CrossRef]

- Agerbirk, N.; Olsen, C.E. Glucosinolate Structures in Evolution. Phytochemistry 2012, 77, 16–45. [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, R.M.; Krosse, S.; Swolfs, A.E.M.; Te Brinke, E.T.; Prill, N. Te; Leimu, R.; Van Galen, P.M.; Wang, Y.; Aarts, M.G.M.; Van Dam, N.M. Isolation and Identification of 4-α-Rhamnosyloxy Benzyl Glucosinolate in Noccaea Caerulescens Showing Intraspecific Variation. Phytochemistry 2015, 110, 166–171. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, B.W.; Oh, M.H.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, E.O.; Chae, W.B. Glucosinolate Variation among Organs, Growth Stages and Seasons Suggests Its Dominant Accumulation in Sexual over Asexual-Reproductive Organs in White Radish. Sci Hortic 2022, 291, 110617. [CrossRef]

- Tolrà, R.; Pongrac, P.; Poschenrieder, C.; Vogel-Mikuš, K.; Regvar, M.; Barceló, J. Distinctive Effects of Cadmium on Glucosinolate Profiles in Cd Hyperaccumulator Thlaspi Praecox and Non-Hyperaccumulator Thlaspi Arvense. Plant Soil 2006, 288, 333–341. [CrossRef]

- Unger, K.; Raza, S.A.K.; Mayer, T.; Reichelt, M.; Stuttmann, J.; Hielscher, A.; Wittstock, U.; Gershenzon, J.; Agler, M.T. Glucosinolate Structural Diversity Shapes Recruitment of a Metabolic Network of Leaf-Associated Bacteria. Nature Communications 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Anthony, M.A.; Celenza, J.L.; Armstrong, A.; Frey, S.D. Indolic Glucosinolate Pathway Provides Resistance to Mycorrhizal Fungal Colonization in a Non-Host Brassicaceae. Ecosphere 2020, 11, e03100. [CrossRef]

- Szucs, Z.; Plaszkó, T.; Cziáky, Z.; Kiss-Szikszai, A.; Emri, T.; Bertóti, R.; Sinka, L.T.; Vasas, G.; Gonda, S. Endophytic Fungi from the Roots of Horseradish (Armoracia Rusticana) and Their Interactions with the Defensive Metabolites of the Glucosinolate - Myrosinase - Isothiocyanate System. BMC Plant Biol 2018, 18, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ullah, C.; Reichelt, M.; Beran, F.; Yang, Z.L.; Gershenzon, J.; Hammerbacher, A.; Vassão, D.G. The Phytopathogenic Fungus Sclerotinia Sclerotiorum Detoxifies Plant Glucosinolate Hydrolysis Products via an Isothiocyanate Hydrolase. Nature Communications 2020 11:1 2020, 11, 1–12. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).