Submitted:

01 August 2025

Posted:

01 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

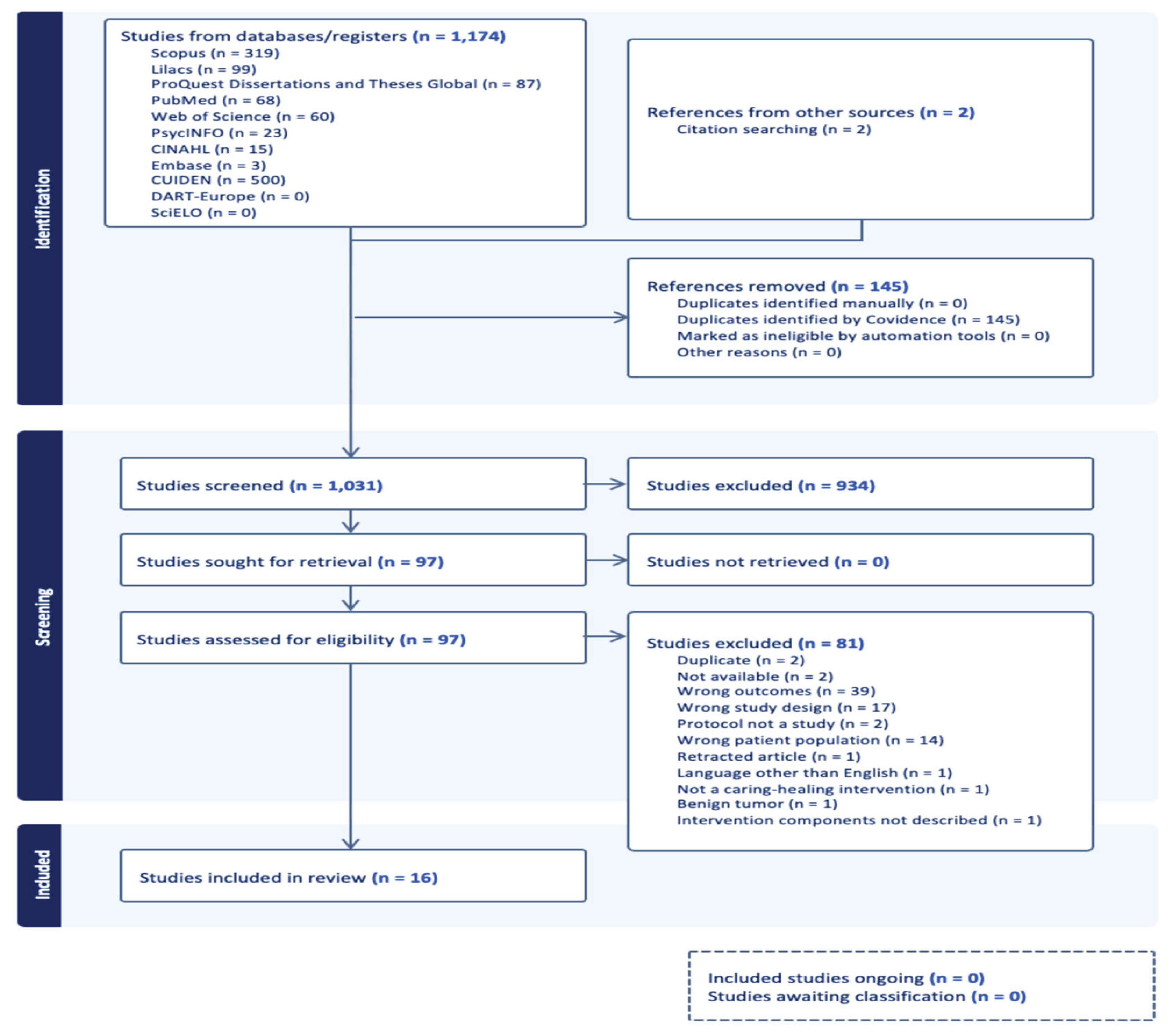

3.1. Source of Evidence Inclusion

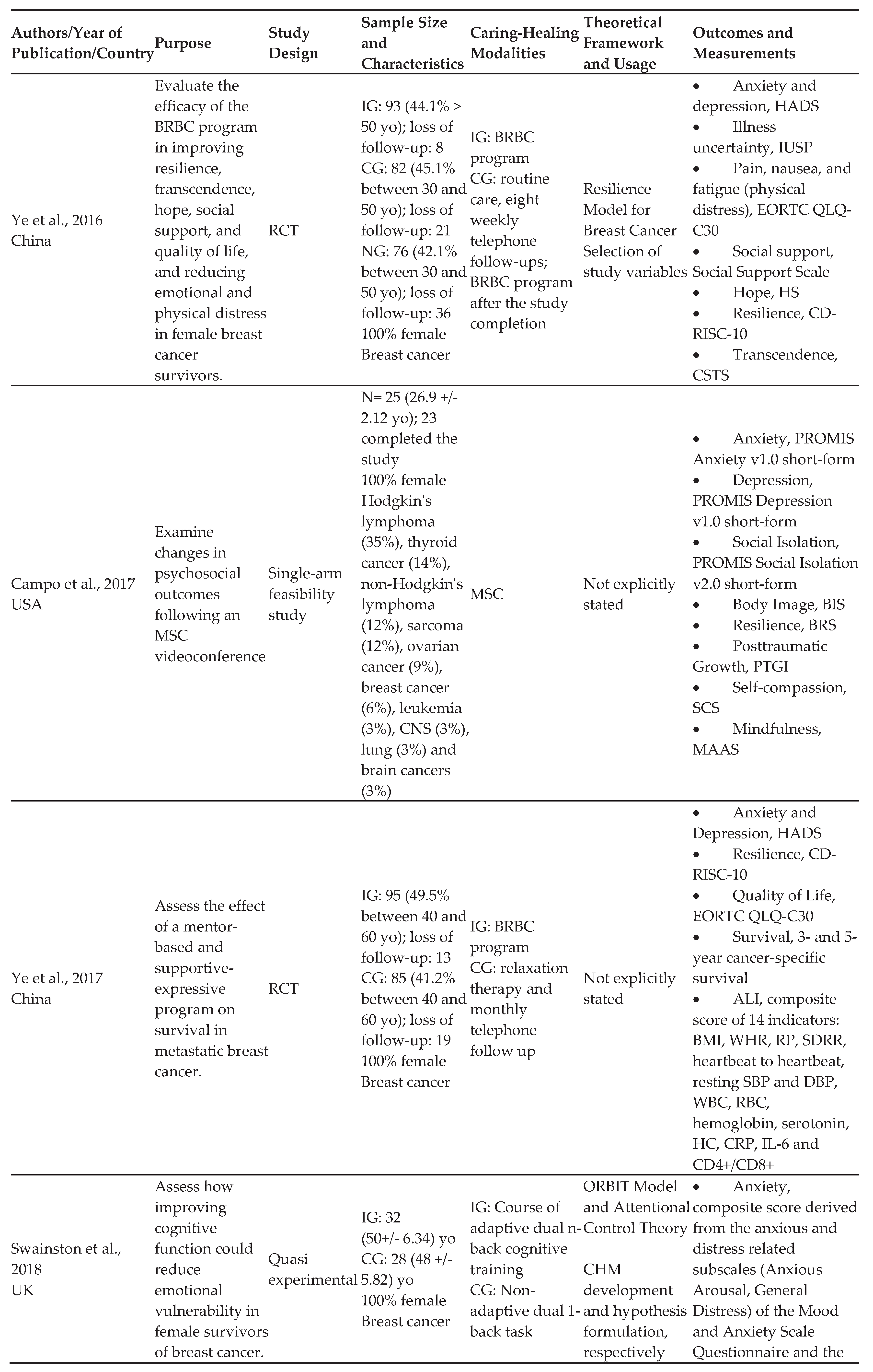

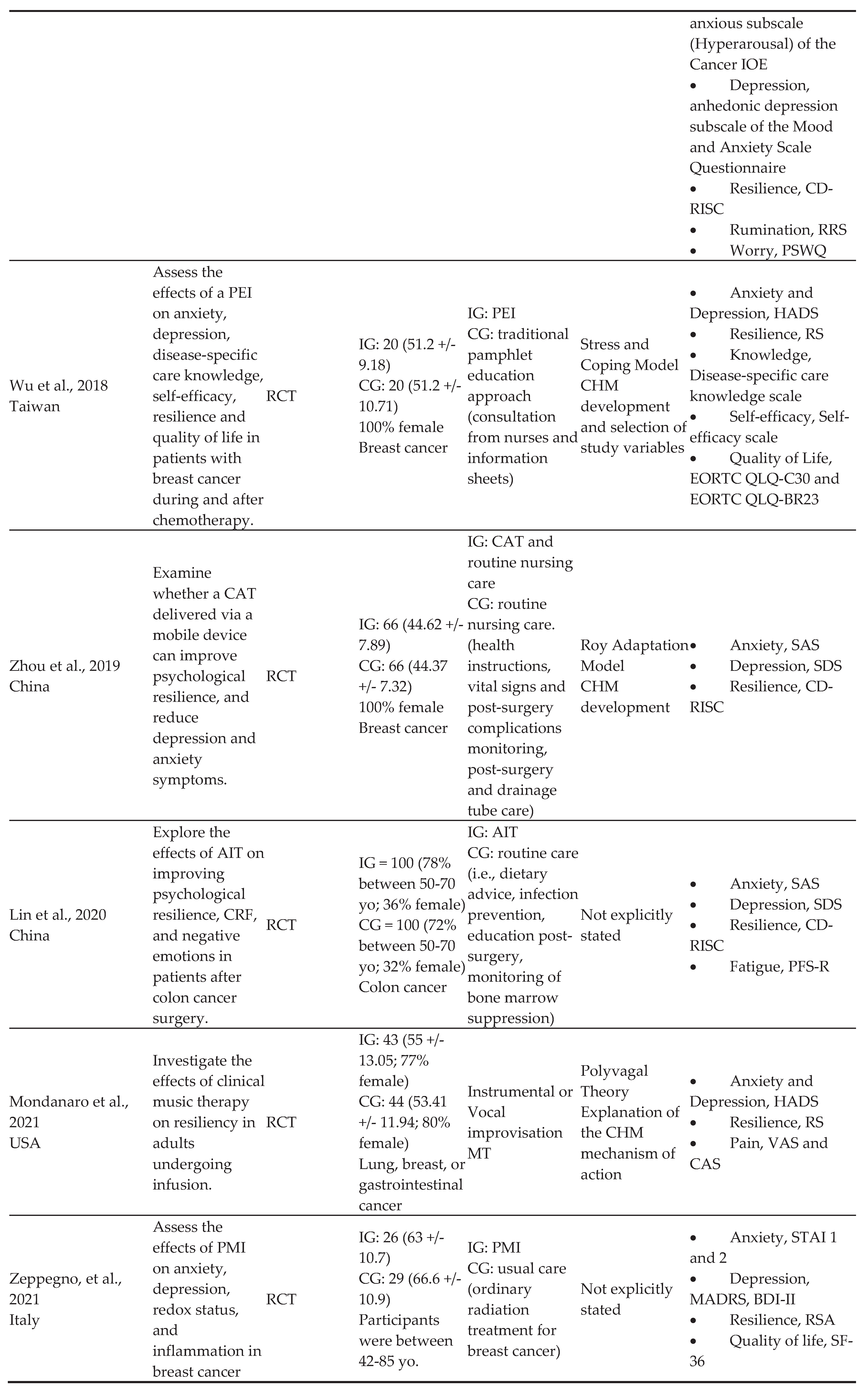

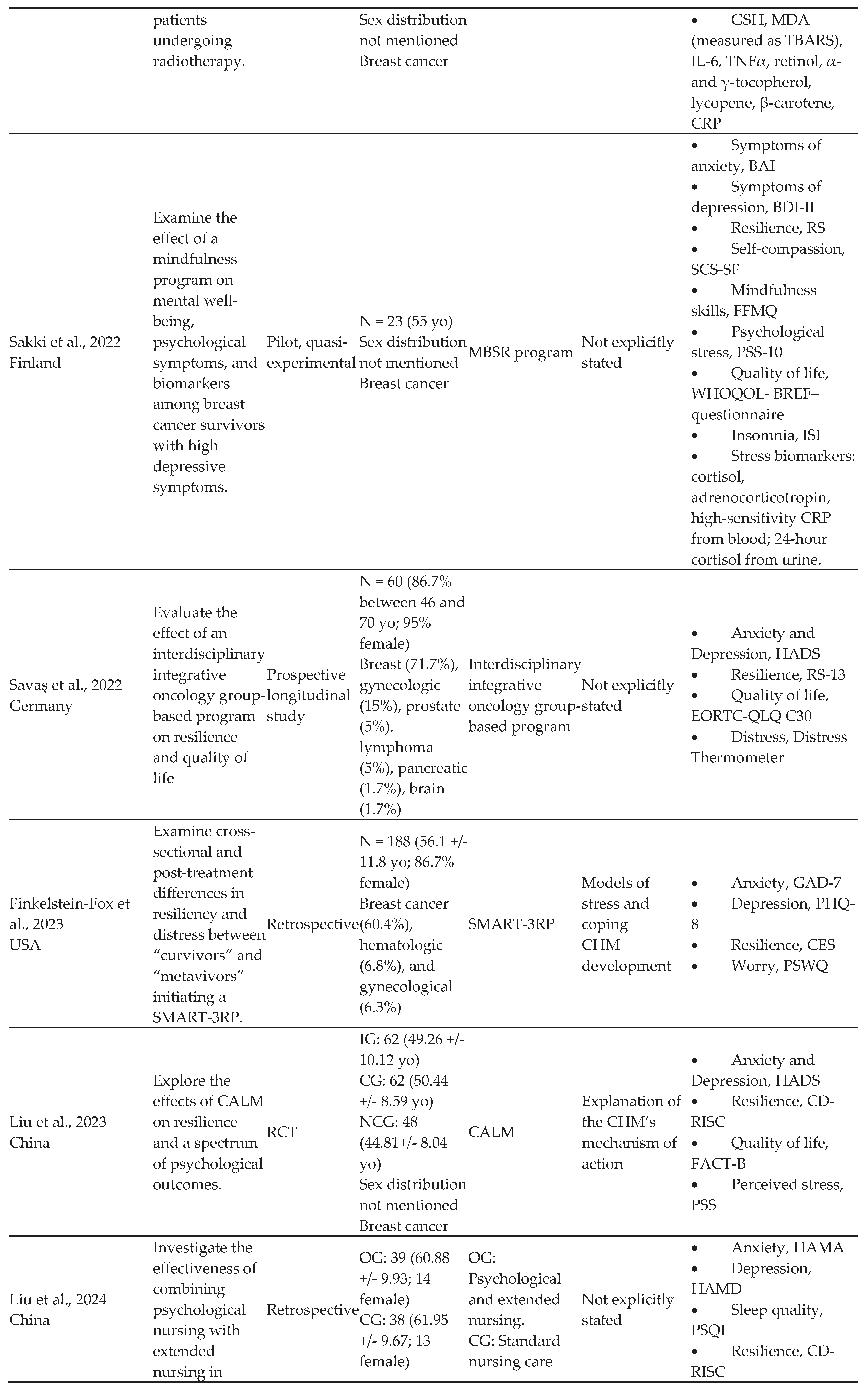

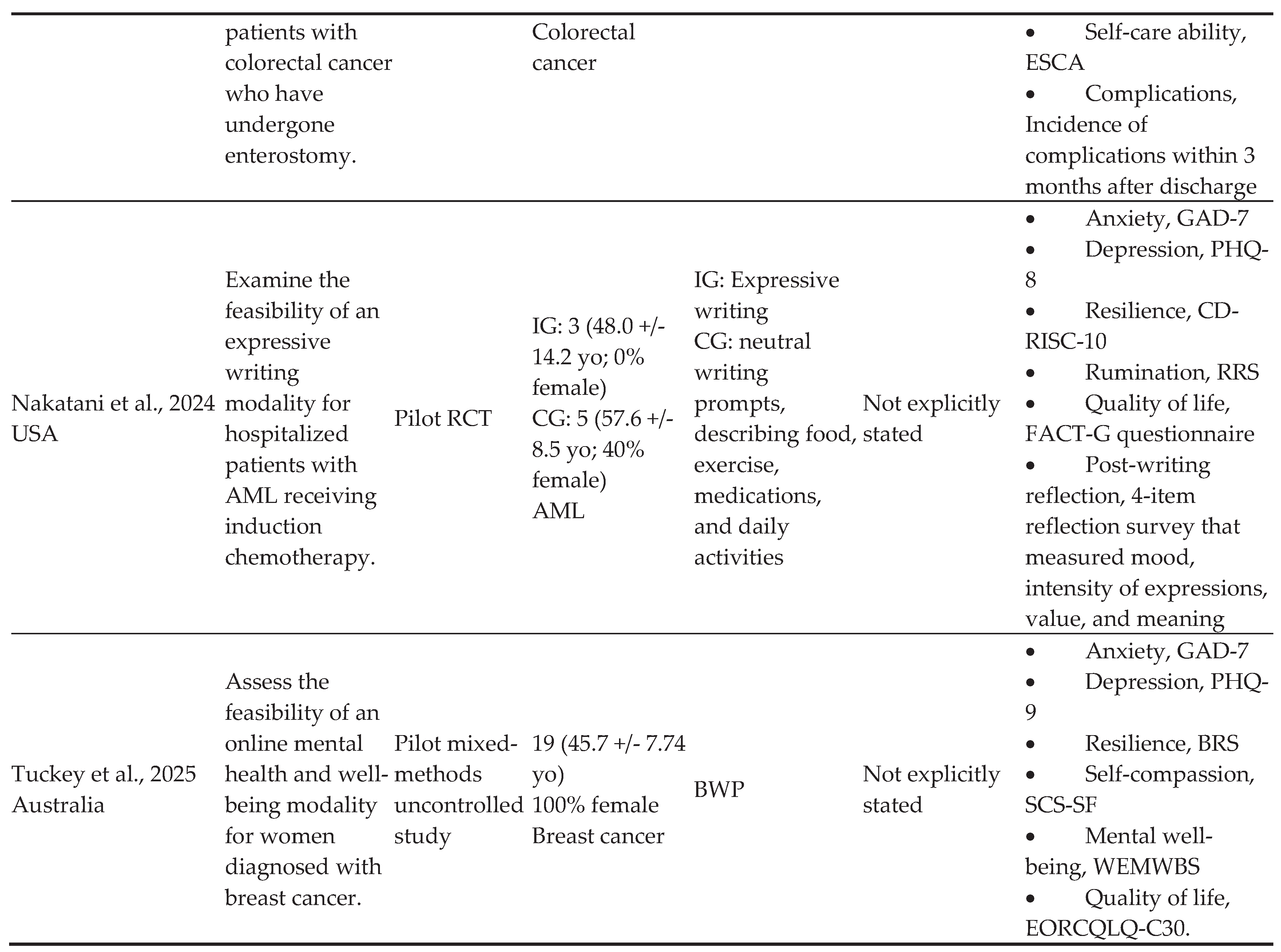

3.2. Characteristics of Included Sources of Evidence

3.3. Review Findings

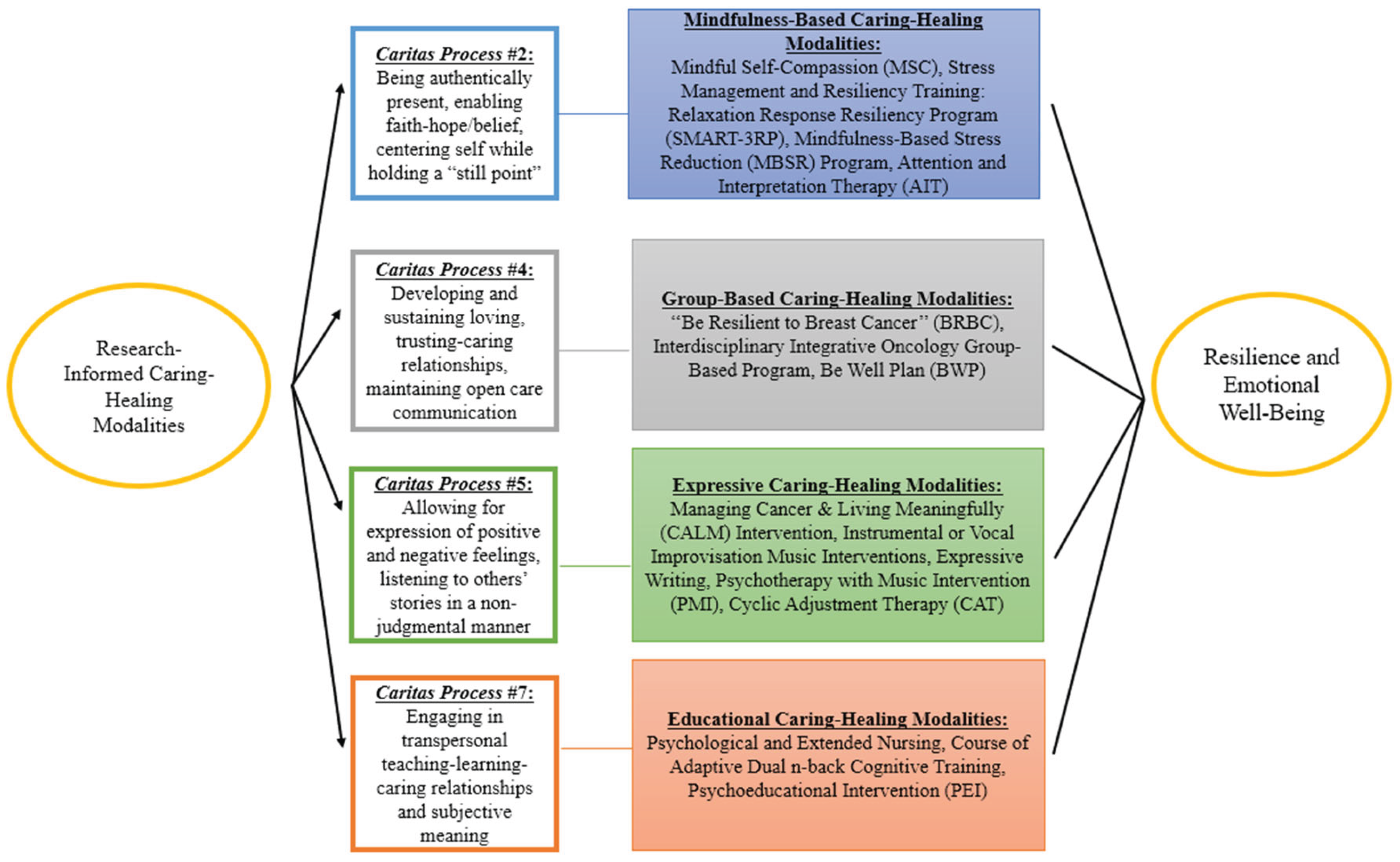

3.3.1. Mindfulness-Based Caring Healing Modalities (Caritas Process #2)

3.3.2. Group-Based Caring Healing Modalities (Caritas Process #4)

3.3.3. Expressive Caring Healing Modalities (Caritas Process #5)

3.3.4. Educational Caring Healing Modalities (Caritas Process #7)

3.3.5. Other Outcomes Assessed in the Sources of Evidence and Measurement Tools

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PwC | Persons with cancer |

| CHMs | Caring-healing modalities |

| CPs | Caritas Processes |

References

- Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Cancer stat facts: Common cancer sites. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/common.html (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Corn, B. W., & Feldman, D. B. Cancer statistics, 2025: A hinge moment for optimism to morph into hope? A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2025, 75, 7–9, . [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Gonzalez, A., Velasco-Durantez, V., Martin-Abreu, C., Cruz-Castellanos, P., Hernandez, R., Gil-Raga, M., Garcia-Torralba, E., Garcia-Garcia, T., Jimenez-Fonseca, P., & Calderon, C. Fatigue, emotional distress, and illness uncertainty in patients with metastatic cancer: Results from the prospective NEOETIC_SEOM study. Current Oncology 2022, 29, 9722–9732, . [CrossRef]

- Caldiroli, C. L., Sarandacchi, S., Tomasuolo, M., Diso, D., Castiglioni, M., & Procaccia, R. Resilience as a mediator of quality of life in cancer patients in healthcare services. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 1-11, . [CrossRef]

- Martin, C. M., Schofield, E., Napolitano, S., Avildsen, I. K., Emanu, J. C., Tutino, R., Roth, A. J., & Nelson, C. J. African-centered coping, resilience, and psychological distress in Black prostate cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 2022, 31, 622–630, . [CrossRef]

- Orom, H., Nelson, C. J., Underwood, W., 3rd, Homish, D. L., & Kapoor, D. A. Factors associated with emotional distress in newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 1416–1422, . [CrossRef]

- Shalata, W., Gothelf, I., Bernstine, T., Michlin, R., Tourkey, L., Shalata, S., & Yakobson, A. Mental health challenges in cancer patients: A cross-sectional analysis of depression and anxiety. Cancers 2024, 16, 1-14, . [CrossRef]

- Getie, A., Ayalneh, M., & Bimerew, M. Global prevalence and determinant factors of pain, depression, and anxiety among cancer patients: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 1-17, . [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Feng, W. Cancer-related psychosocial challenges. General Psychiatry 2022, 35, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Groarke, A., Curtis, R., Skelton, J., & Groarke, J. M. Quality of life and adjustment in men with prostate cancer: Interplay of stress, threat and resilience. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 1–16, . [CrossRef]

- Wei, H., Hardin, S. R., & Watson., J. A Unitary Caring Science resilience-building model: Unifying the human caring theory and research-informed psychology and neuroscience evidence. International Journal of Nursing Sciences 2021, 8, 130-135, . [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., Shan, H., Wu, C., Chen, H., Shen, Y., Shi, W., Wang, L., & Li, Q. The mediating effect of self-efficacy on family functioning and psychological resilience in prostate cancer patients. Frontiers in Psychology 2024, 15, 1-10, . [CrossRef]

- Deshields, T. L., Asvat, Y., Tippey, A. R., & Vanderlan, J. R. Distress, depression, anxiety, and resilience in patients with cancer and caregivers. Health Psychology 2022, 41, 246–255, . [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H., Li, M., Wang, B., Yuan, X., Dong, B., Yin, H., & Yang, Y. The relationship among resilience, anxiety and depression in patients with prostate cancer in China: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Clinical Nursing in Practice 2023, 9, 102–110, . [CrossRef]

- Tan, W. S., Beatty, L., & Koczwara, B. Do cancer patients use the term resilience? A systematic review of qualitative studies. Supportive Care in Cancer 2019, 27, 43–56, . [CrossRef]

- Lukose, A. Developing a practice model for Watson’s Theory of Caring. Nursing Science Quarterly 2011, 24, 27-30, . [CrossRef]

- Gürcan, M., & Turan, S. A. Examining the expectations of healing care environment of hospitalized children with cancer based on Watson’s Theory of Human Caring. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2021, 77, 3472–3482, . [CrossRef]

- Watson, J. Metaphysics of Watson unitary caring science: A cosmology of love. University Press of Colorado: Louisville, United States, 2021, pp. 1-298.

- Sidani, S., & Braden, C. J. Nursing and Health Interventions. Design, Evaluation, and Implementation, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, United States, 2021; pp. 50-51.

- Watson, J. Nursing: The philosophy and science of caring. In Caring in Nursing Classics: An Essential Resource; M. C. Smith, M. C. Turkel, & Z. R. Wolf; Springer Publishing Company, LLC: New York, United States, 2013; pp. 243-263.

- Christie, D. R. H., Sharpley, C. F., & Bitsika, V. A systematic review of the association between psychological resilience and improved psychosocial outcomes in prostate cancer patients. Could resilience training have a potential role?. The World Journal of Men's Health 2024, 43, 1-11, . [CrossRef]

- Galway, K., Black, A., Cantwell, M. M., Cardwell, C. R., Mills, M., & Donnelly, M. Psychosocial interventions to improve quality of life and emotional wellbeing for recently diagnosed cancer patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, 11, 1-61, . [CrossRef]

- Opalinski, A. S., Martinez, L. A., Butcher, H., Bertulfo, T., Stewart, D., & Gengo, R. A theory-guided literature review: A knowledge synthesis methodology. The Journal of Nursing Education 2025, 64, 279–285, . [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Available online: http://jbisumari.org/ (accessed on 20 April, 2025).

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Lewin, S., … Straus, S. E. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 2018, 169, 467–473, . [CrossRef]

- Acoba E. F. Social support and mental health: The mediating role of perceived stress. Frontiers in Psychology 2024, 15, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Amin, S. M., Khedr, M. A., Tawfik, A. F., Malek, M. G. N., E-Ashry, A. M. The mediating and moderating role of social support on the relationship between psychological well-being and burdensomeness among elderly with chronic illness: Community nursing perspective. BMC Nursing 2025, 24, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Covidence [Reference Manager Software]. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Campo, R. A., Bluth, K., Santacroce, S. J., Knapik, S., Tan, J., Gold, S., Philips, K., Gaylord, S., & Asher, G. N. A mindful self-compassion videoconference intervention for nationally recruited posttreatment young adult cancer survivors: Feasibility, acceptability, and psychosocial outcomes. Support Care Cancer 2017, 25, 1759–1768, . [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z. J., Liang, M. Z., Qiu, H. Z., Liu, M. L., Hu, G. Y., Zhu, Y. F., Zeng, Z., Zhao, J. J., & Quan, X. M. Effect of a multidiscipline mentor-based program, Be Resilient to Breast Cancer (BRBC), on female breast cancer survivors in mainland China - A randomized, controlled, theoretically-derived intervention trial. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2016, 158, 509–522, . [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z. J., Qiu, H. Z., Liang, M. Z., Liu, M. L., Li, P. F., Chen, P., Sun, Z., Yu, Y. L., Wang, S. N., Zhang, Z., Liao, K. L., Peng, C. F., Huang, H., Hu, G. Y., Zhu, Y. F., Zeng, Z., Hu, Q., & Zhao, J. J. Effect of a mentor-based, supportive-expressive program, Be Resilient to Breast Cancer, on survival in metastatic breast cancer: A randomised, controlled intervention trial. British Journal of Cancer 2017, 117, 1486–1494, . [CrossRef]

- Tuckey, N., van Agteren, J., Chur-Hansen, A., Ali, K., Fassnacht, D. B., Beatty, L., Bareham, M., Wardill, H., & Lasiello, M. Implementing a group-based online mental well-being program for women living with and beyond breast cancer – A mixed methods study. Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology 2025, 21, 180-189, . [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K., Li, J., & Li, X. Effects of cyclic adjustment training delivered via a mobile device on psychological resilience, depression, and anxiety in Chinese post-surgical breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2019, 178, 95–103, . [CrossRef]

- Wu, P. H., Chen, S. W., Huang, W. T., Chang, S. C., & Hsu, M. C. Effects of a psychoeducational intervention in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Journal of Nursing Research 2018, 26, 266–279, . [CrossRef]

- Swainston, J., & Derakshan, N. Training cognitive control to reduce emotional vulnerability in breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2018, 27, 1780-1786, . [CrossRef]

- Lin, C., Diao, Y., Dong, Z., Song, J., & Bao, C. The effect of attention and interpretation therapy on psychological resilience, cancer-related fatigue, and negative emotions of patients after colon cancer surgery. Annals of Cardiothoracic Surgery 2020, 9, 3261–3270, . [CrossRef]

- Liu, F., Yao, K., & Liu, X. Analysis on effect of psychological nursing combined with extended care for improving negative emotions and self-care ability in patients with colorectal cancer and enterostomy. A retrospective study. Medicine 2024, 103, 1-7, http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000038165.

- Nakatani, M. M., Locke, S. C., Herring, K. W., Somers, T., & LeBlanc, T. W. Expressive writing to address distress in hospitalized adults with acute myeloid leukemia: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 2024, 42, 587–603, . [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein-Fox, L., Bliss, C. C., Rasmussen, A. W., Hall, D. L., El-Jawahri, A., & Perez, G. K. Do cancer curvivors and metavivors have distinct needs for stress management intervention? Retrospective analysis of a mind-body survivorship program. Supportive Care in Cancer 2023, 31, 1–11, http://www.springer.com/medicine/oncology/journal/520.

- Savaş, B. B., Märtens, B., Cramer, H., Voiss, P., Longolius, J., Weiser, A., Ziert, Y., Christiansen, H., & Steinmann, D. Effects of an interdisciplinary integrative oncology group-based program to strengthen resilience and improve quality of life in cancer patients: Results of a prospective longitudinal single-center study. Integrative Cancer Therapies 2022, 21, 1-11, . [CrossRef]

- Mondanaro, J. F., Sara, G. A., Thachil, R., Pranjić, M., Rossetti, A., EunHye Sim, G., Canga, B., Harrison, I. B., & Loewy, J. V. The effects of clinical music therapy on resiliency in adults undergoing infusion: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2021, 61, 1099–1108, . [CrossRef]

- Sakki, S. E., Penttinen, H. M., Hilgert, O. M., Volanen, S.-M., Saarto, T., & Raevuori, A. Mindfulness is associated with improved psychological well-being but no change in stress biomarkers in breast cancer survivors with depression: A single group clinical pilot study. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 1-12, . [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Huang, R., Li, A., Yu, S., Yao, S., Xu, J., Tang, L., Li, W., Gan, C., & Cheng, H. Effects of the CALM intervention on resilience in Chinese patients with early breast cancer: A randomized trial. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 2023, 149, 18005–18021, . [CrossRef]

- Zeppegno, P., Krengli, M., Ferrante, D., Bagnati, M., Burgio, V., Farruggio, S., Rolla, R., Gramaglia, C., & Grossini, E. Psychotherapy with music intervention improves anxiety, depression and the redox status in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Cancers 2021, 13, 1-16, . [CrossRef]

- Lynex, C., Meehan, D., Whittaker, K., Buchanan, T., & Varlow, M. The need for improved integration of psychosocial and supportive care in cancer: A qualitative study of Australian patient perspectives. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 2025, 33, 1-9, . [CrossRef]

- Kiemen, A., Czornik, M., & Weis, J. How effective is peer-to-peer support in cancer patients and survivors? A systematic review. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 2023, 149, 9461–9485, . [CrossRef]

- Azizoğlu, H., Gürkan, Z., Bozkurt, Y., Demir, C., & Akaltun, H. The effect of an improved environment according to Watson's theory of human care on sleep, anxiety, and depression in patients undergoing open heart surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1-16, . [CrossRef]

- Tian Y. A review on factors related to patient comfort experience in hospitals. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition 2023, 42, 1-19, . [CrossRef]

- Song, L., Qan'ir, Y., Guan, T., Guo, P., Xu, S., Jung, A., Idiagbonya, E., Song, F., & Kent, E. E. The challenges of enrollment and retention: A systematic review of psychosocial behavioral interventions for patients with cancer and their family caregivers. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2021, 62, e279–e304, . [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q., Wang, F., Wang, G., Liu, L. & Hu, X. Recent evidence and progress for developing precision nursing in symptomatology: A scoping review. International Nursing Review 2023, 70, 415–424, . [CrossRef]

- Nelson J. W. Using the profile of caring: Measuring nurses' caring for self and caring by their unit manager. Creative Nursing 2022, 28, 17–22, . [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

| Authors/ Year of Publication | Caring-Healing Modality Setting | Active ingredients | Non-specific Elements | Medium | Format | Structure/Approach | Dose | Duration and Frequency |

| Ye et al., 2016 | Outpatient setting | Education related to breast cancer (e.g. breast reconstruction, posttreatment issues, sexuality, anxiety, depression, uncertainty, diet and nutrition, music therapy, emotion management, positive mind therapy, traditional Chinese medicine, Taichi). Peer support Group discussions |

Not identified | Group-based and one-on-one; person-dependent Verbal/written |

In-person, phone calls Techniques included didactic lectures and group discussions on the following themes: surgery and treatment, physical therapy, emotional distress, nausea, diet and nutrition, traditional Chinese Medicine, Taichi practice, music and relaxation techniques, sexuality, restoration, to be better, and renewal. |

Standardized Curriculum with tailored mentor-mentee matching |

3 hours per session | 12 months; 8 weekly sessions in first 2 months, plus 3 follow-ups at 2, 6, and 12 months |

| Campo et al., 2017 | Participants’ homes or private location | MSC, self-esteem, gratitude, and self-appreciation | Quiet environment (headphones), control of distractions, protection of privacy, interaction among members on Facebook secret groups, assistance with technical issues while using online platform, reminders | Group-based, person dependent Verbal/written |

Online/remote (videoconference), including several techniques: didactic instruction, experiential activities (e.g., compassionate friend meditation, body scan, here-and-now stone, affectionate breathing meditation, loving kindness meditations, soften-soothe allow meditation, gratitude phone photos), introduction of different meditations and daily tools, group discussion, and interaction on Facebook | Standardized | 90-minute sessions | Once per week for 8 weeks |

| Ye et al., 2017 | Outpatient setting | Education related to breast cancer (e.g., surgery and treatment, physical therapy, emotional distress, nausea, diet and nutrition, traditional Chinese Medicine, Taichi practice, music and relaxation techniques, sexuality, restoration, to be better, and renewal) Peer support |

Not identified | Group-based Verbal/written |

In-person Techniques included didactic lectures and group discussions |

Standardized | 120 minutes per session | 12 months; weekly sessions |

| Swainston et al., 2018 | Home | Cognitive training | Not identified | Individual-based Verbal/written |

Online Techniques included adaptive dual n-back cognitive training tasks |

Standardized | 30 minutes per session | 12 days across 2-week period; daily sessions |

| Wu et al, 2018 | Cancer Medical Center | PEI consisting of an educational manual addressing depression, anxiety, disease-specific care knowledge, self-efficacy, and resilience, and a self-assessment of learning | Supervision by healthcare professionals, use of a self-directed videotape, educational information and materials | Individual-based Verbal/written |

In person; techniques included interaction between healthcare professionals and patients (telephone consultations), self-directed videotape, educational manual | Standardized CHM plan based on educational and support components | 1 hour per session | 6 sessions during five chemotherapy treatments |

| Zhou et al., 2019 | Hospital/home | Deep breath training, music listening, anti-cancer stories (reading/listening/watching), self-reflection, shared decision-making | Routine nursing care, health instruction, vital signs and post-surgery complications monitoring, post-surgery and drainage tube care | Group-based, person-dependent Verbal/written |

Online (via WeChat), in person (nurse-to-patient instruction) | Standardized | 30-60 minutes per session for nurse-to-patient instruction before surgery; 20 minutes per session for relaxed deep breath training before surgery; 10 minutes per session for relaxed deep breath training three times per day after surgery; 20-30 minutes per session for music listening and anti-cancer stories (reading/listening/watching) three times per day after surgery. | From hospital admission to 12 weeks follow-up; relaxed deep breath training three times per day and once before surgery; music listening and anti-cancer stories (reading/listening/watching) three times per day; re-introspect once per week |

| Lin et al., 2020 | Hospital and home | Transcendental meditation, emotional control, cultivation of appreciation, mindfulness, acceptance, support from peers, and commitment therapy | Nurse supervision and follow-up, personal file establishment, incentives for continuous practice (text message), maintaining peer connection, communication with interventionists | Group based person depended Verbal/written |

Face-to-face Techniques included didactic instruction, group meetings, emotional diaries, WeChat emotion management applet, video sharing, patient workshops |

Tailored according to the special needs of the patient | 30 minutes per session | Daily for 10 weeks |

| Mondanaro et al., 2021 | Hospital | Instrumental or vocal music | Not identified | Individual-based Verbal, auditory |

In-person Techniques included warm up, improvisation (melody, harmony, timbre, and rhythmic idioms), discussion of therapeutic goals and themes or issues identified in the music or self-disclosure |

Standardized | 20 minutes per session | 3 sessions over 1 to 3 months |

| Zeppegno, et al., 2021 | Quiet room at a hospital | Psychodynamic psychotherapy, MT, peer support | Supportive role of residents, quietness, privacy | Group-based Verbal/written |

In-person Techniques included music listening, song lyric analysis, sharing of emotions and memories, group discussions |

Standardized | 1 hour per session | 6 weeks; weekly sessions |

| Sakki et al., 2022 | Between- session practices done at home; group sessions not clearly stated | Mindfulness home practice, including body scan, breathing exercises, mindful movements and yoga practice, awareness | Silent retreat, diary, audio recordings describing nature and content of mindful practices | Group-based Verbal/written |

Informal home practices, group sessions, and diary of independent mindfulness practice | Standardized | 2.5 hours per session, 45 minutes for home practices | 8 weeks; weekly sessions, in addition to between-session practices and one day long silent retreat |

| Savaş et al., 2022 | Outpatient setting | Neurocognitive restructuring, recommendations for diet, exercise, stress management, relaxation, naturopathic self-help strategies, and psychosocial support | Not identified | Group-based Verbal, auditory, tactile |

In-person Music therapy, manual therapies |

Standardized | 5 hours per session, including a 2-hour break | 10 weeks; weekly sessions |

| Finkelstein-Fox et al., 2023 | Not clearly stated | Stress-awareness, stress-coping, and stress-buffering skills | Not clearly stated | Group-based Person-depended Verbal/written |

In-person, videoconferencing Program manual Mind-body techniques that elicit the RR (i.e., meditation, breath awareness), positive psychology (i.e., shifting focus to positive experiences), and cognitive behavioral therapy (i.e., re-structuring negative thoughts) |

Tailored | Not clearly stated | Once per week for 8 or 9 weeks |

| Liu et al., 2023 | Hospital | Guidance for symptom management, discussion of changes brought by the disease, psychotherapy to clarify the purpose and meaning of existence, discussion of concerns about the future and understanding of death | Trusting relationship, education regarding adverse effects of illness and treatment | Individual-based Visual/auditory, verbal |

In-person Techniques included dialogue, didactic instruction, virtual reality therapy |

Tailored to the participants’ needs | At least 30 minutes per session | 12 weeks; six sessions over 12 weeks |

| Liu et al., 2024 | Outpatient setting and home | Education, instillation of hope and confidence, meaning therapy, family association and peer support, emotional expression, and extended care (follow-up) | Personal file establishment, maintaining communication with interventionists, and encouragement to ask questions | Individual- and group- based, person-depended Verbal/written |

Face-to-face/in-person, telephone, and online Techniques included didactic instruction, group meetings, emotional expression, WeChat groups, video sharing |

Tailored to the participants’ needs | Not clearly stated | Once per week, not clearly stated for how long |

| Nakatani et al., 2024 | Hospital | Emotional expression Post writing reflections |

Instructions | Individual-based Verbal (coaching)/written |

In-person and remote (Zoom and phone) Techniques included writing prompts and coaching |

Standardized | 1-hour sessions | 4 sessions over 2 weeks |

| Tuckey et al., 2025 | Outpatient setting and home | Psychoeducation, self-reflection, and sharing | Awareness of participant’s mental health (survey); having a support person in the program | Group-based Verbal/written |

Online or face-to-face/in-person, mobile app | Tailored (developing own well-being plan) | 2 hours per session | 5 weeks; weekly sessions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).