Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

01 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

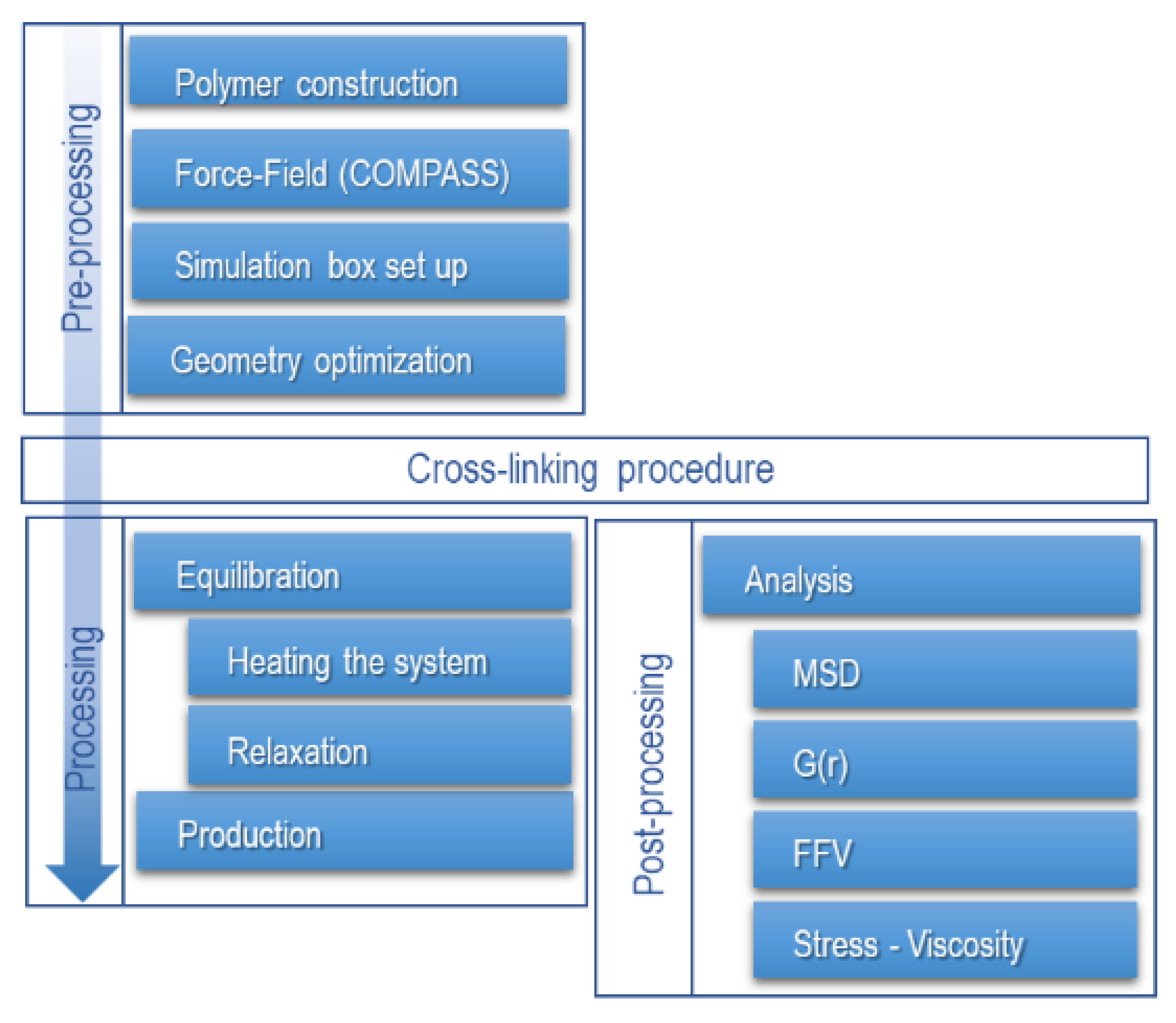

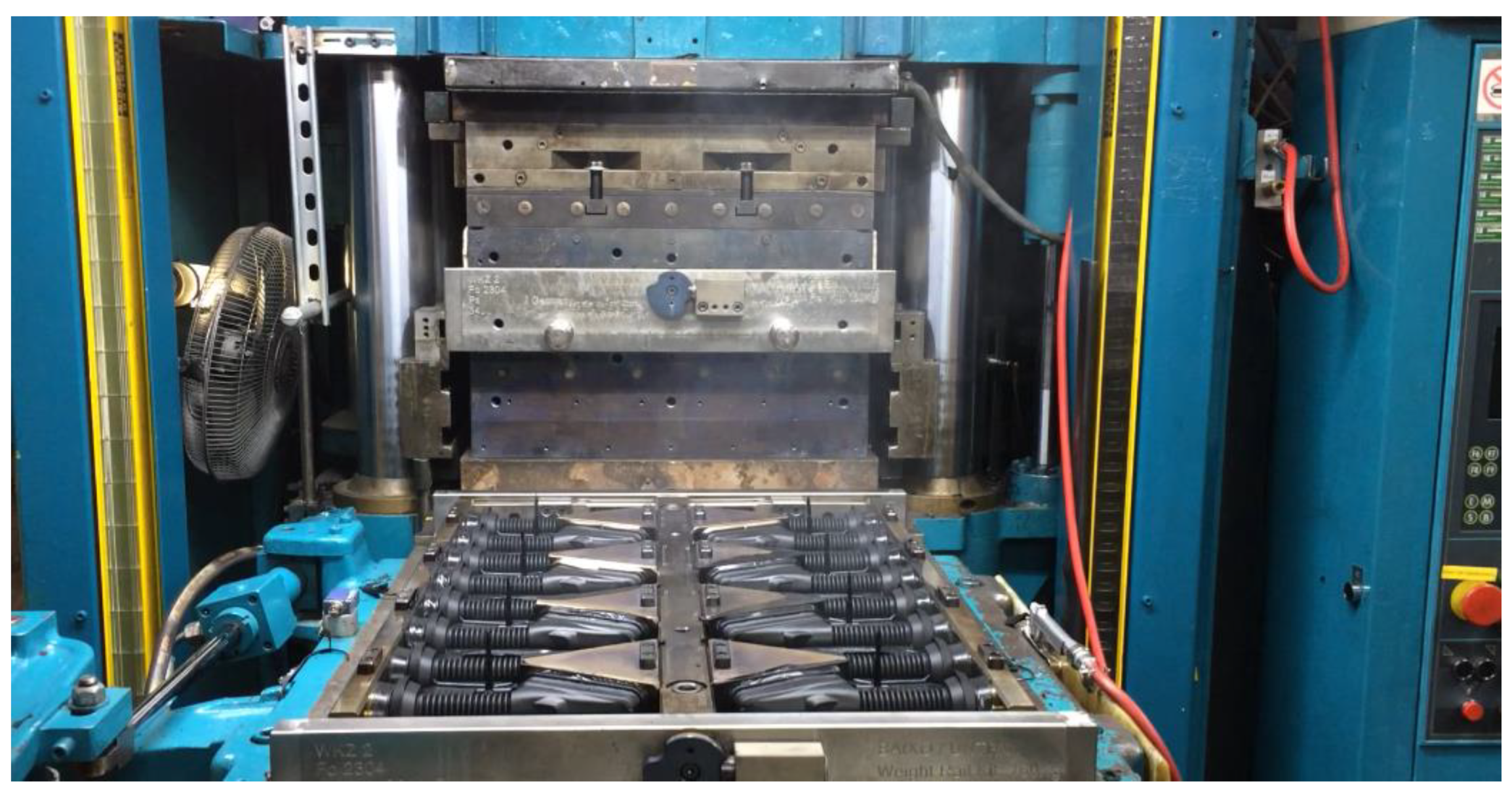

2. Materials and Methods

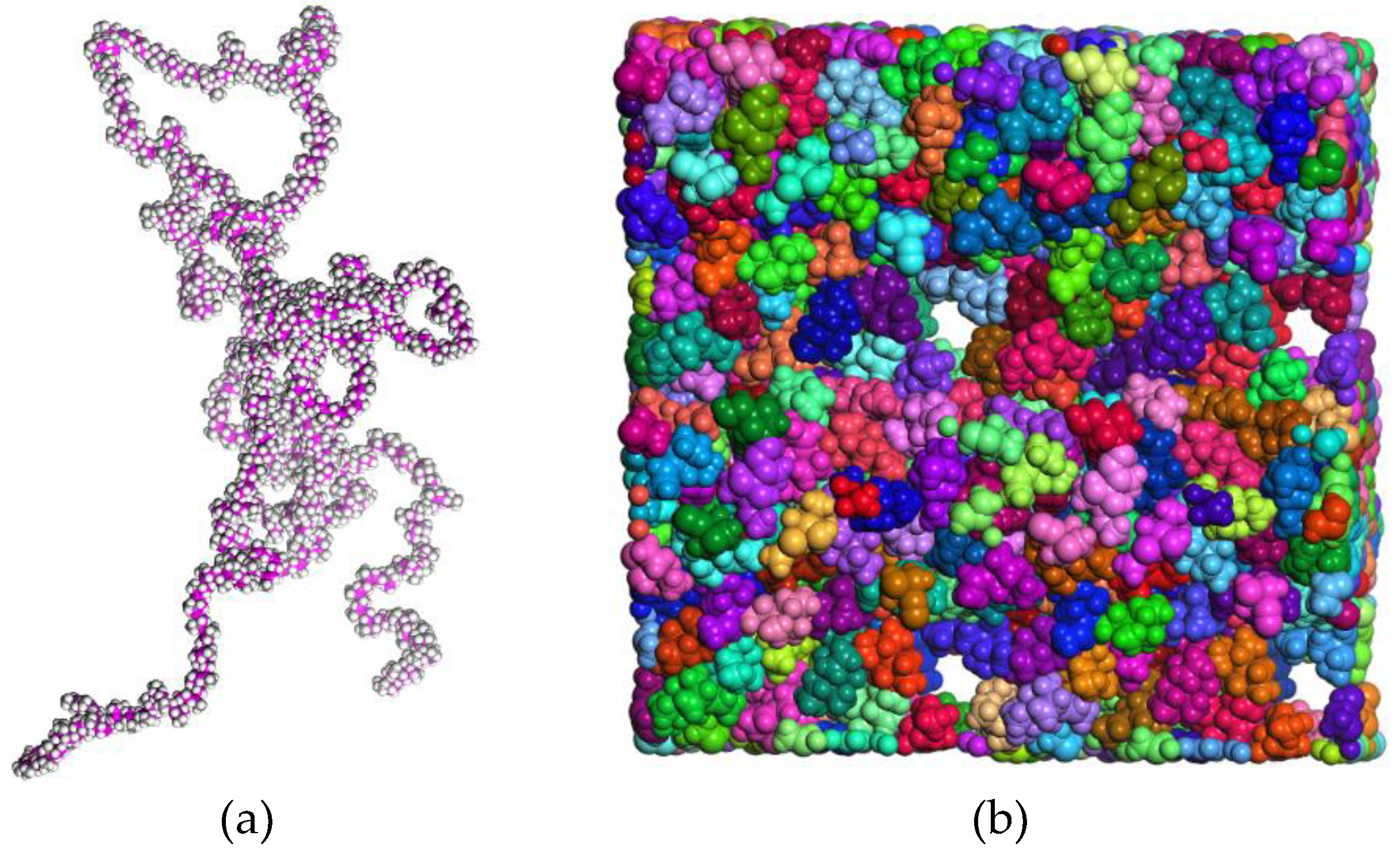

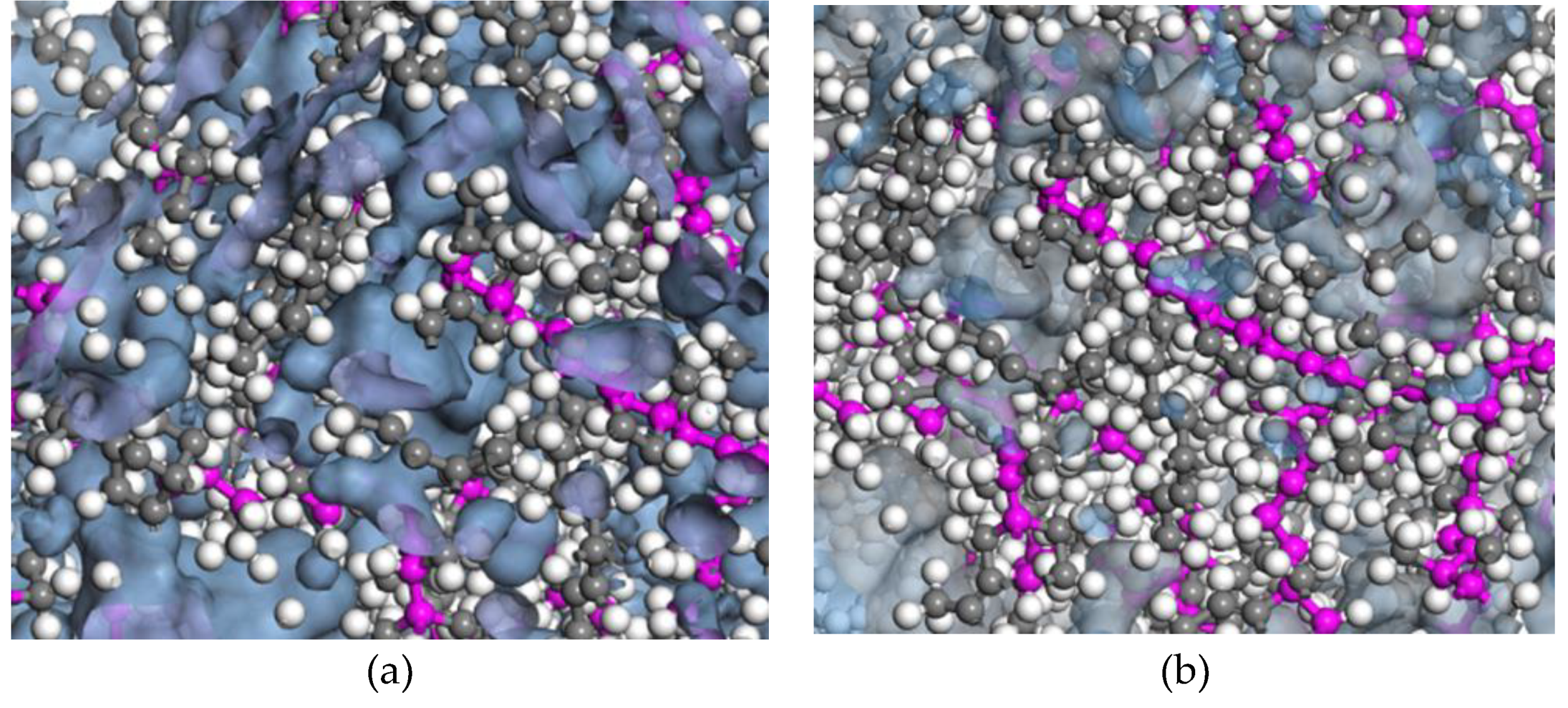

2.1. Topology of the System Subsection

2.2. Interatomic potential parameterization

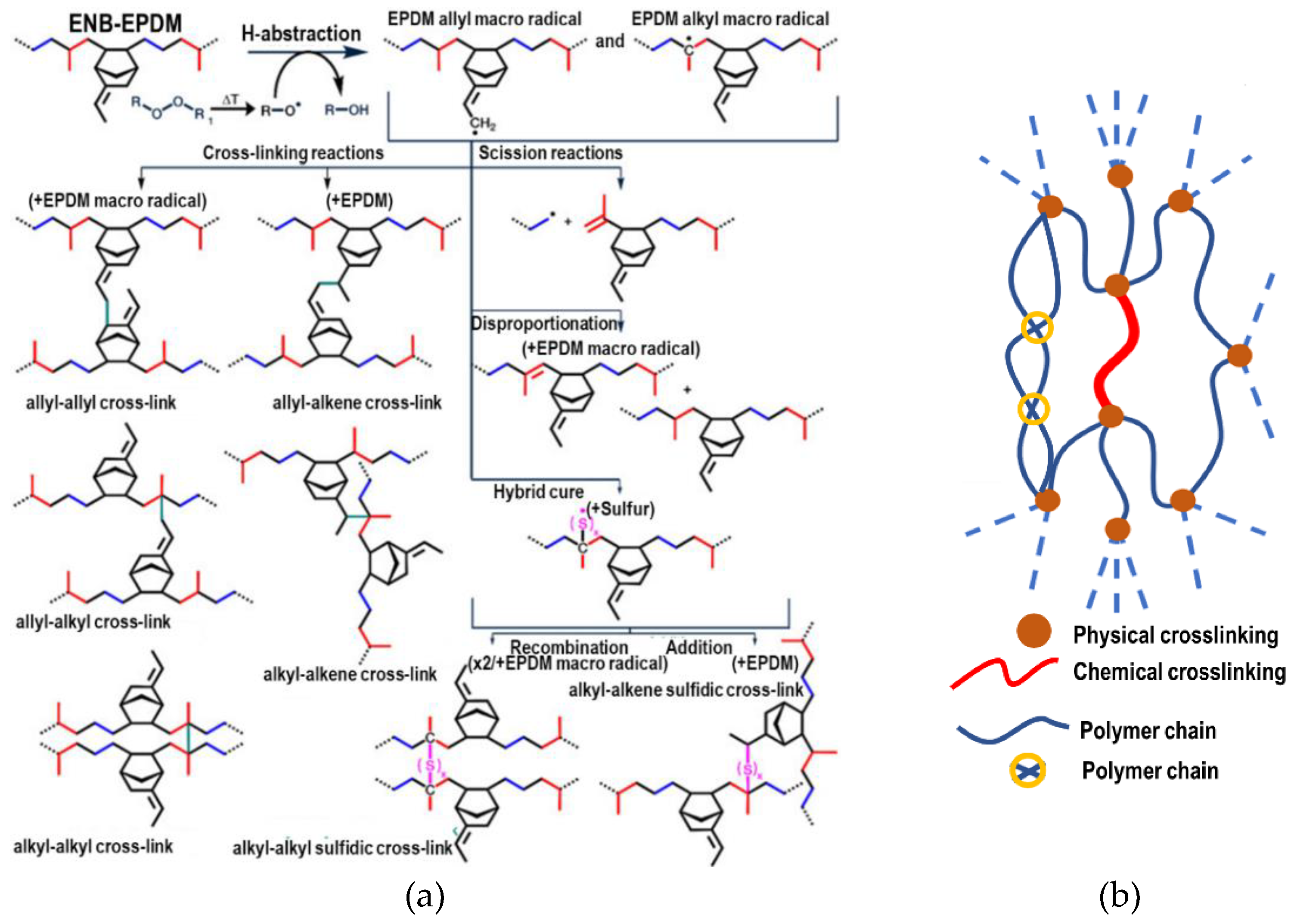

2.3. Cross-Linking Characteristics

2.4. Procedure for Molecular Dynamics Simulation

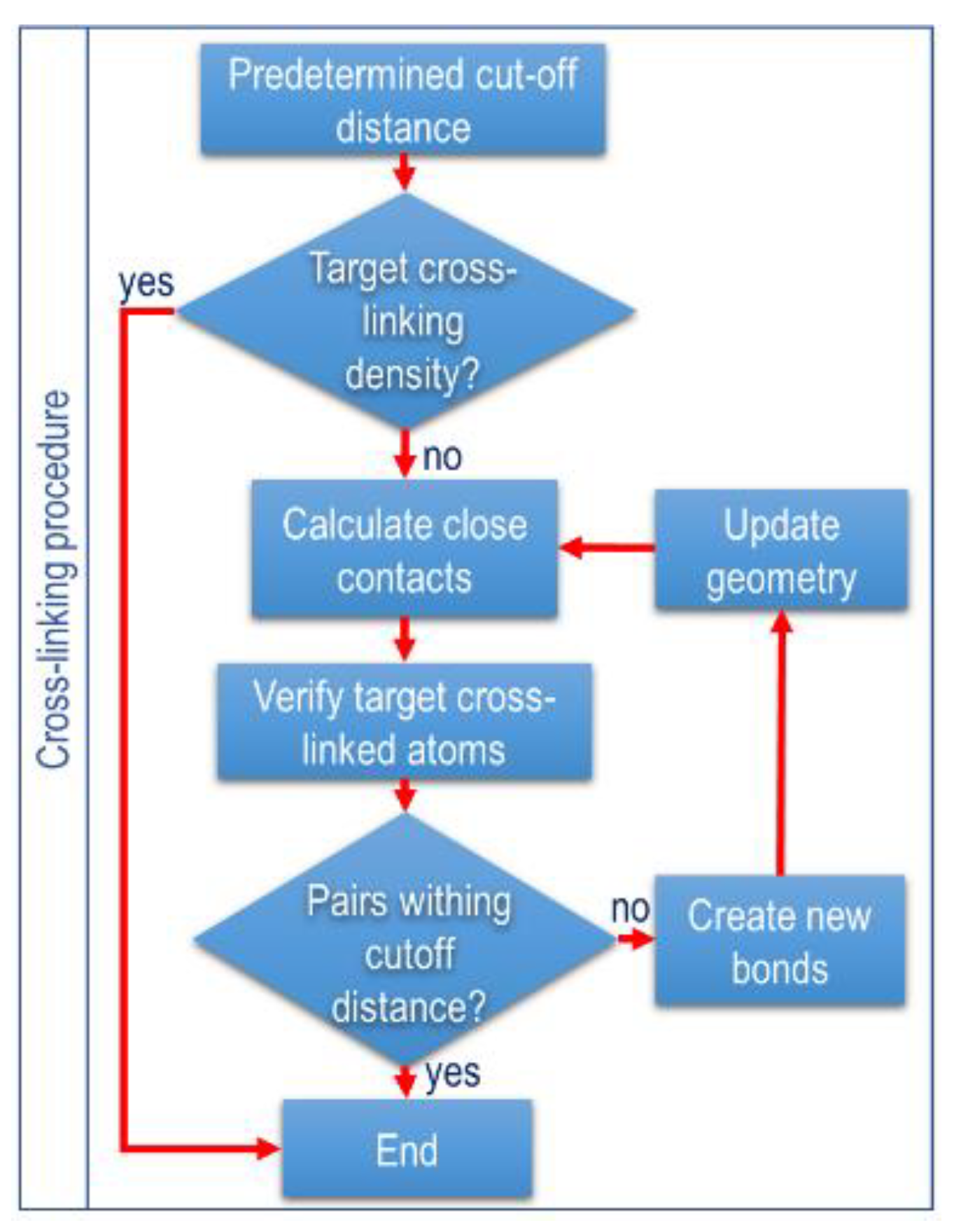

2.5. Cross-Linking Procedure

3. Results

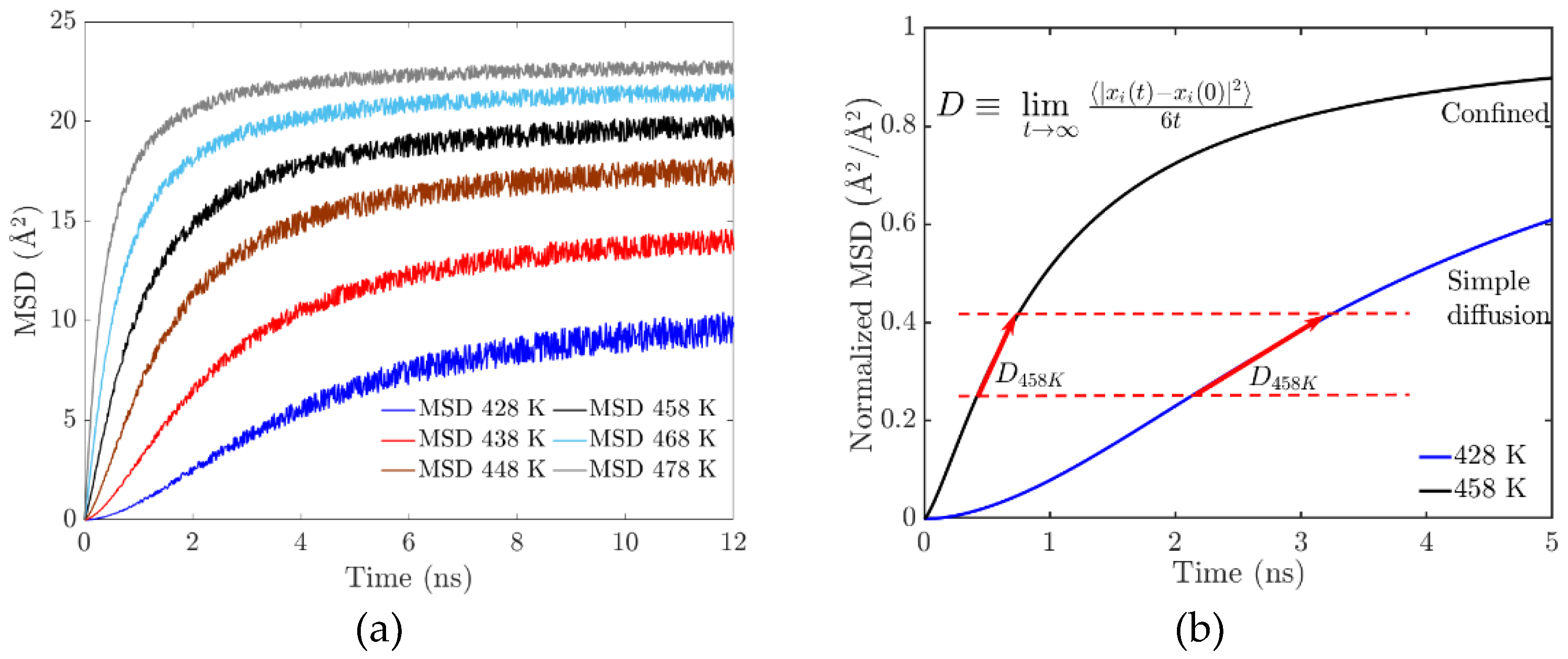

3.1. Mean Square Displacement (MSD)

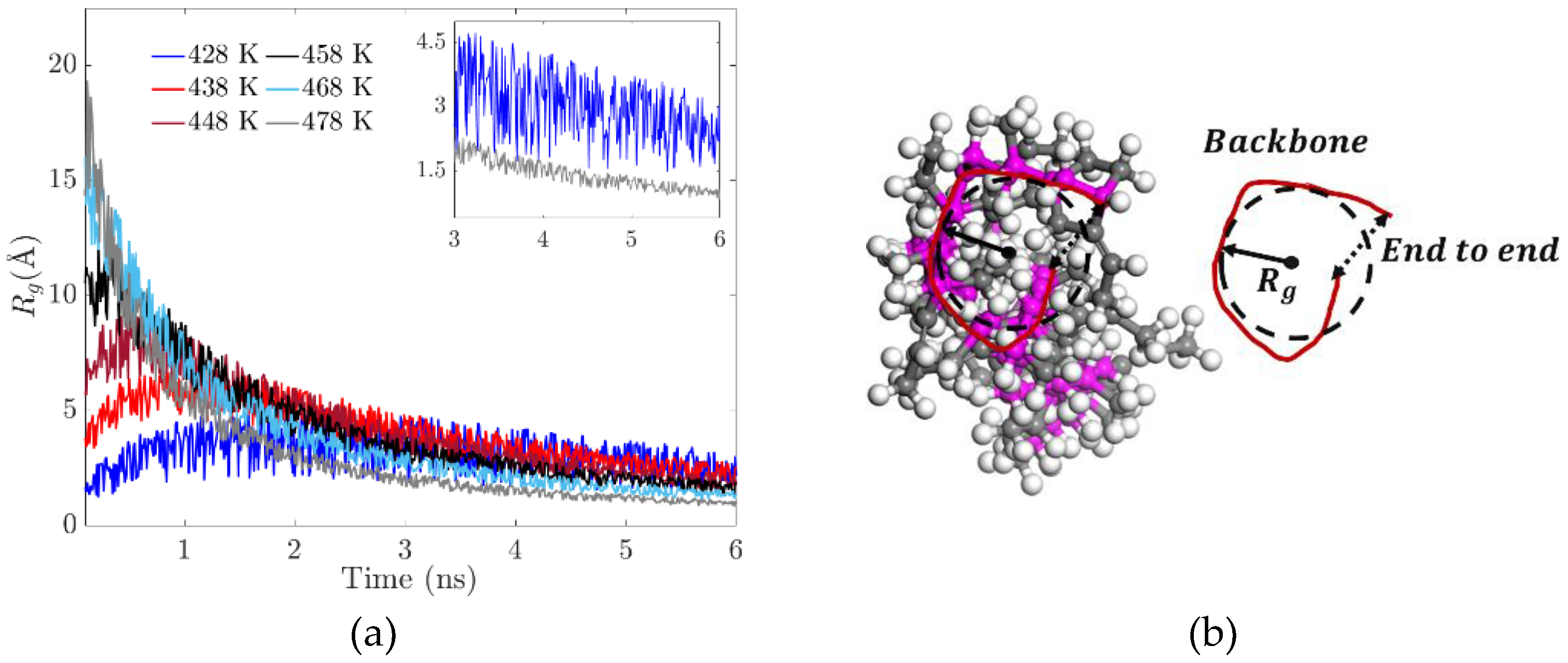

3.2. Radius of Gyration (Rg)

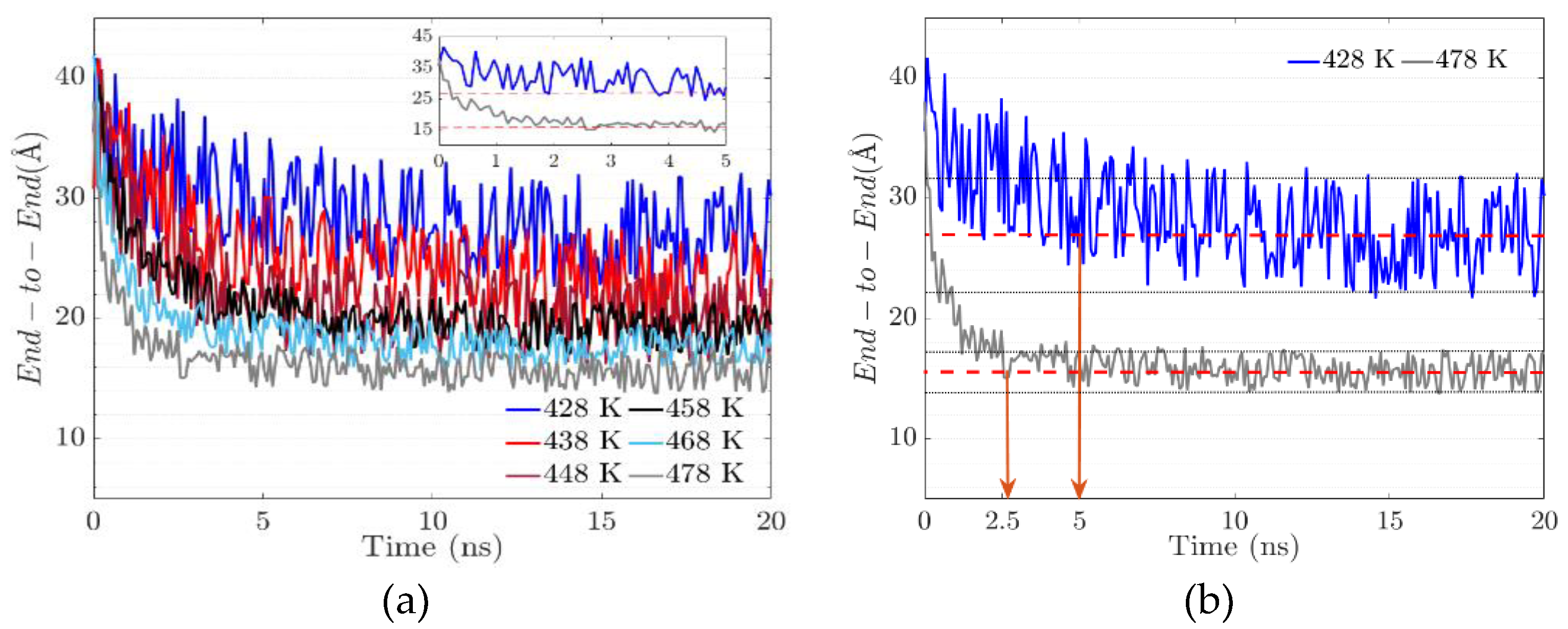

3.3. The End-to-End Vector

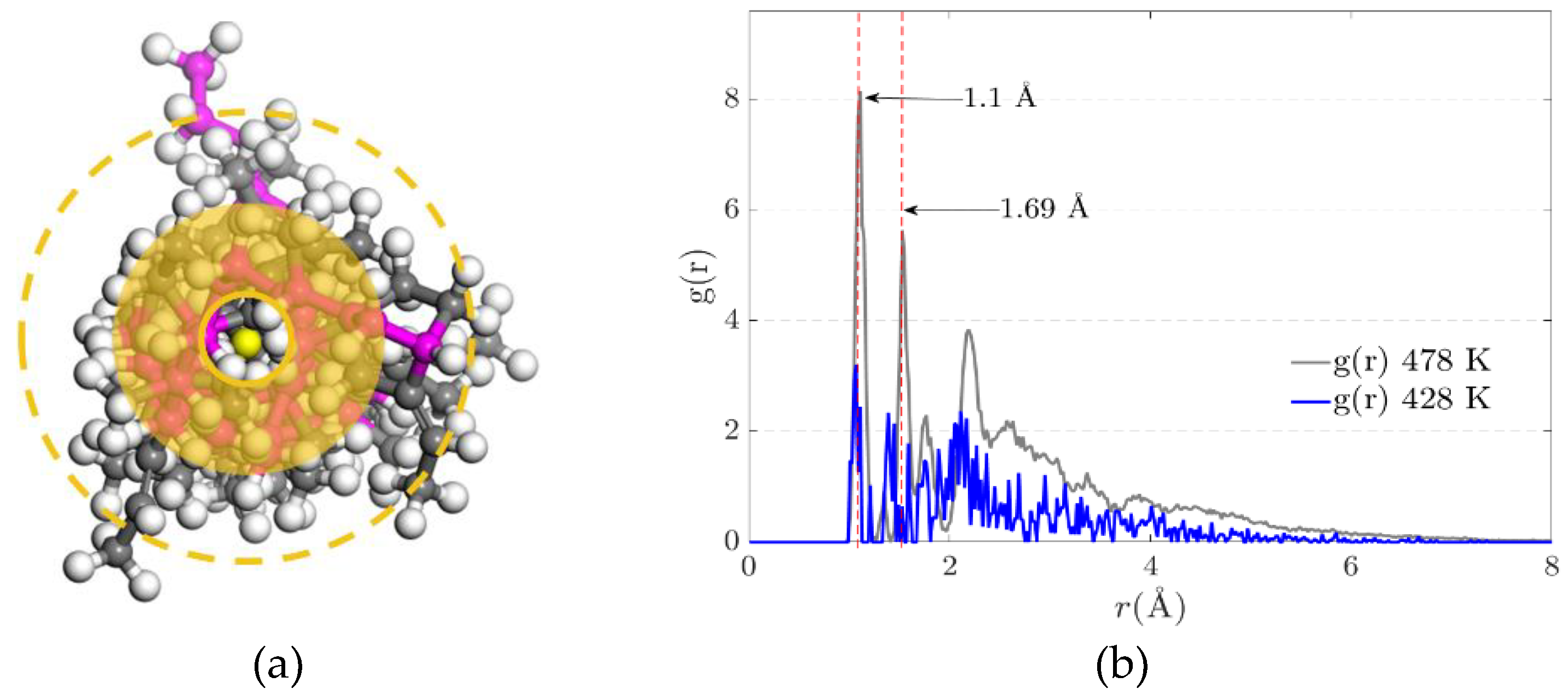

3.4. Radial Distribution Function (g(r))

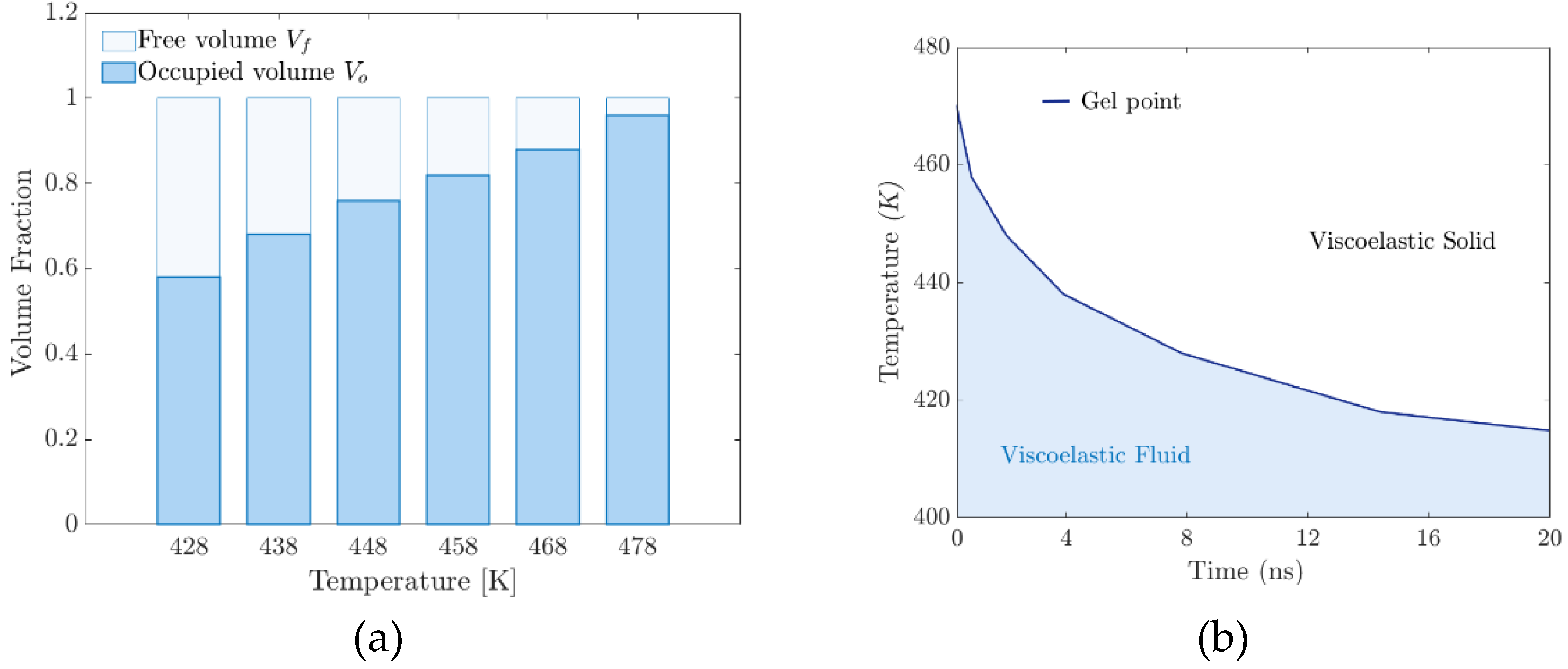

3.5. Free Volume

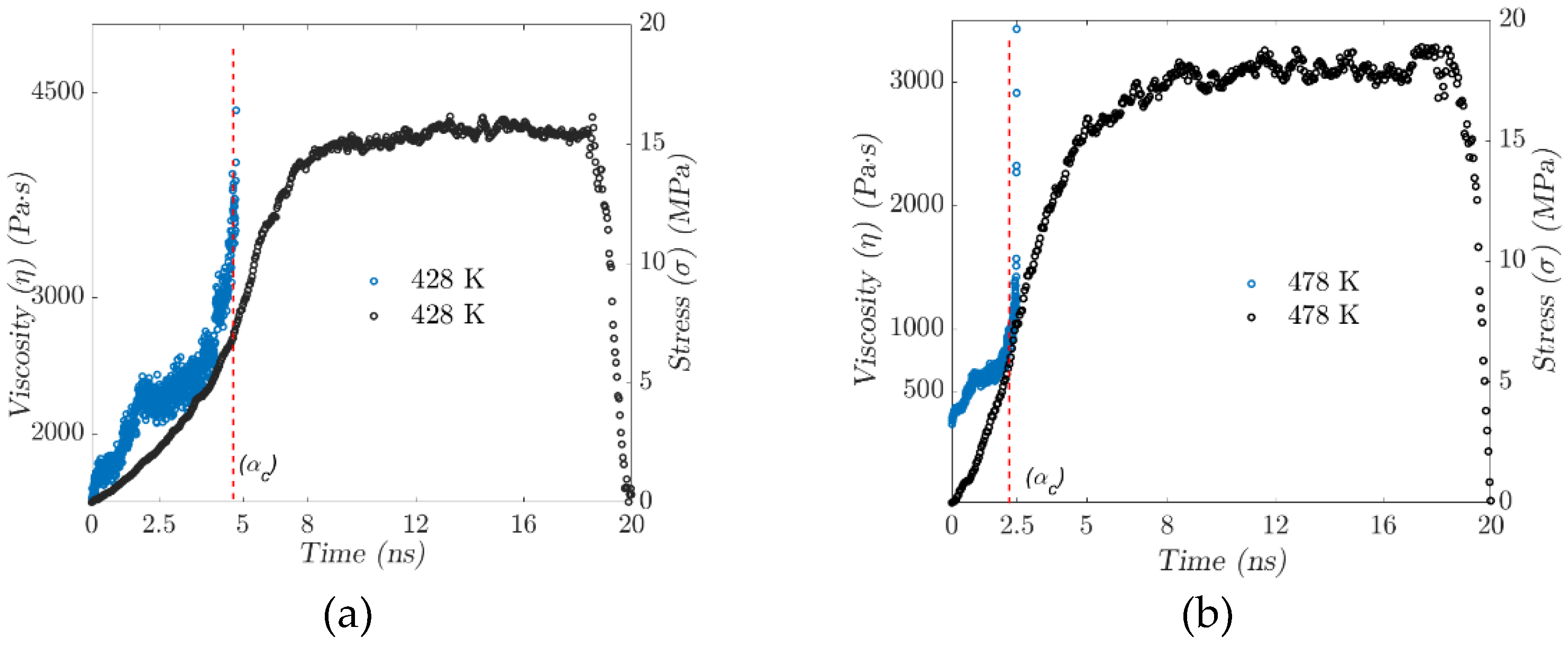

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S. Li, H. Tian, H. Wu, N. Ning, M. Tian, and L. Zhang, “Coupling effect of molecular weight and crosslinking kinetics on the formation of rubber nanoparticles and their agglomerates in EPDM/PP TPVs during dynamic vulcanization,” Soft Matter, 10.1039/C9SM02059D vol. 16, no. 9, pp. 2185- 2198, 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Bouguedad et al., “Physico-chemical study of thermally aged EPDM used in power cables insulation,” IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation, vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 3207- 3215, 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. Ravishankar, “Treatise on EPDM,” Rubber chemistry and technology, vol. 85, no. 3, pp. 327-349, 2012.

- R. Shaji and N. N. Kumar, “Simulation of Room Temperature Vulcanized Gasket Failure at Engine T-Joints,” ARAI Journal of Mobility Technology, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 108-111, 2022.

- N. C. Restrepo-Zapata, B. Eagleburger, T. Saari, T. A. Osswald, and J. P. Hernández-Ortiz, “Chemorheological time-temperature-transformation-viscosity diagram: Foamed EPDM rubber compound,” Journal of Applied Polymer Science, vol. 133, no. 38, ppn/a-n/a. 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Milani and F. Milani, “EPDM accelerated sulfur vulcanization: a kinetic model based on a genetic algorithm,” Journal of mathematical chemistry, vol. 49, no. 7, pp. 1357-1383, 2011.

- W. Niu, Y. Li, Y. Ma, and G. Zhao, “Determination and Prediction of Time-Varying Parameters of Mooney–Rivlin Model of Rubber Material Used in Natural Rubber Bearing under Alternating of Aging and Seawater Erosion,” Materials, vol. 16, no. 13, p. 4696, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/16/13/4696.

- J. Jiang, J.-s. Xu, Z.-s. Zhang, and X. Chen, “Rate-dependent compressive behavior of EPDM insulation: Experimental and constitutive analysis,” Mechanics of Materials, vol. 96, pp. 30-38, 2016/05/01/ 2016. 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. Habieb, F. Milani, G. Milani, G. Pianese, and D. Torrini, “Vulcanization degree influence on the mechanical properties of Fiber Reinforced Elastomeric Isolators made with reactivated EPDM,” Polymer Testing, vol. 108, p. 107496, 2022/04/01/ 2022. [CrossRef]

- Shi, C. Cao, M. Lei, L. Peng, and J. Shen, “Time-dependent performance and constitutive model of EPDM rubber gasket used for tunnel segment joints,” Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology, vol. 50, pp. 490-498, 2015/08/01/ 2015. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Z. A. Rashid et al., “Temperature Dependent on Mechanical and Rheological Properties of EPDM-Based Magnetorheological Elastomers Using Silica Nanoparticles,” Materials, vol. 15, no. 7, p. 2556, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/15/7/2556.

- C. T. Hiranobe et al., “Cross-linked density determination of natural rubber compounds by different analytical techniques,” Materials Research, vol. 24, p. e20210041, 2021.

- V. Morovati, A. Bahrololoumi, and R. Dargazany, “Fatigue-induced stress-softening in cross-linked multi-network elastomers: Effect of damage accumulation,” International Journal of Plasticity, vol. 142, p. 102993, 45 2021/07/01/ 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Shen, X. Lin, J. Liu, and X. Li, “Effects of Cross-Link Density and Distribution on Static and Dynamic Properties of Chemically Cross-Linked Polymers,” Macromolecules, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 121-134, 2019/01/08. [CrossRef]

- M. Cheng, W. Chen, and B. Song, “Phenomenological Modeling of the Stress-Stretch Behavior of EPDM Rubber with Loading-rate and Damage Effects,” International Journal of Damage Mechanics, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 371-381, 2004/10/01 2004. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, H. Liu, P. Li, and L. Wang, “The Effect of Cross-Linking Type on EPDM Elastomer Dynamics and Mechanical Properties: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study,” Polymers, vol. 14, no. 7, p. 1308, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/14/7/1308.

- A. Wang, F. Vargas-Lara, J. M. Younker, K. A. Iyer, K. R. Shull, and S. Keten, “Quantifying Chemical Composition and Cross-link Effects on EPDM Elastomer Viscoelasticity with Molecular Dynamics,” Macromolecules, vol. 54, no. 14, pp. 6780-6789, 2021/07/27 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Varshney, S. S. Patnaik, A. K. Roy, and B. L. Farmer, “A Molecular Dynamics Study of Epoxy-Based Networks: Cross-Linking Procedure and Prediction of Molecular and Material Properties,” Macromolecules, vol. 41, no. 18, pp. 6837-6842, 2008/09/23 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. Papanikolaou, D. Drikakis, and N. Asproulis, “Molecular dynamics modelling of mechanical properties of polymers for adaptive aerospace structures,” AIP Conference Proceedings, vol. 1646, no. 1, pp. 66-71, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. van Duin, R. Orza, R. Peters, and V. Chechik, “Mechanism of Peroxide Cross-Linking of EPDM Rubber,” Macromolecular Symposia, vol. 291-292, no. 1, pp. 66-74, 2010. [CrossRef]

- H. Sun, “COMPASS: An ab Initio Force-Field Optimized for Condensed-Phase ApplicationsOverview with Details on Alkane and Benzene Compounds,” The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, vol. 102, no. 38, pp. 7364, 1998/09/01 1998. [CrossRef]

- M. J. McQuaid, H. Sun, and D. Rigby, “Development and validation of COMPASS force field parameters for molecules with aliphatic azide chains,” Journal of Computational Chemistry, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 61-71, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, Y. Yang, and M. Tao, “Understanding Free Volume Characteristics of Ethylene-Propylene-Diene Monomer (EPDM) through Molecular Dynamics Simulations,” Materials, vol. 12, no. 4, p. 612, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/12/4/612.

- M. Zachary et al., “EPR study of persistent free radicals in cross-linked EPDM rubbers,” European Polymer Journal, vol. 44, no. 7, pp. 2099-2107, 2008/07/01/ 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Paterlini and D. M. Ferguson, “Constant temperature simulations using the Langevin equation with velocity Verlet integration,” Chemical Physics, vol. 236, no. 1, pp. 243-252, 1998/09/15/ 1998. [CrossRef]

- K. Yin, H. Xiao, J. Zhong, and D. Xu, “A new method for Calculation of Elastic Properties of Anisotropic material by constant pressure molecular dynamics,” in International Conference of Computational Methods in Sciences and Engineering 2004 (ICCMSE 2004), 2019: CRC Press, pp. 586-588.

- P. R. Varadwaj, “Combined Molecular Dynamics and DFT Simulation Study of the Molecular and Polymer Properties of a Catechol-Based Cyclic Oligomer of Polyether Ether Ketone,” Polymers, vol. 12, no. 5, p. 1054, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/12/5/1054.

- M. Antonietti, T. M. Antonietti, T. Pakula, and W. Bremser, “Rheology of Small Spherical Polystyrene Microgels: A Direct Proof for a New Transport Mechanism in Bulk Polymers besides Reptation,” Macromolecules, vol. 28, no. 12, pp. 4227-4233, 1995/06/01 1995. [CrossRef]

- A. Chremos, C. Jeong, and J. F. Douglas, “Influence of polymer architectures on diffusion in unentangled polymer melts,” Soft Matter, 10.1039/C7SM01018D vol. 13, no. 34, pp. 5778- 5784, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Saleesung, D. Reichert, K. Saalwächter, and C. Sirisinha, “Correlation of crosslink densities using solid state NMR and conventional techniques in peroxide-crosslinked EPDM rubber,” Polymer, vol. 56, pp. 309-317, 2015/01/15/ 2015. [CrossRef]

- B.-G. Xie et al., “A combined simulation and experiment study on polyisoprene rubber composites,” Composites Science and Technology, vol. 200, p. 108398, 2020/11/10/ 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Bandyopadhyay, P. K. Valavala, T. C. Clancy, K. E. Wise, and G. M. Odegard, “Molecular modeling of crosslinked epoxy polymers: The effect of crosslink density on thermomechanical properties,” Polymer, vol. 52, no. 11, pp. 2445-2452, 2011/05/13/ 2011. [CrossRef]

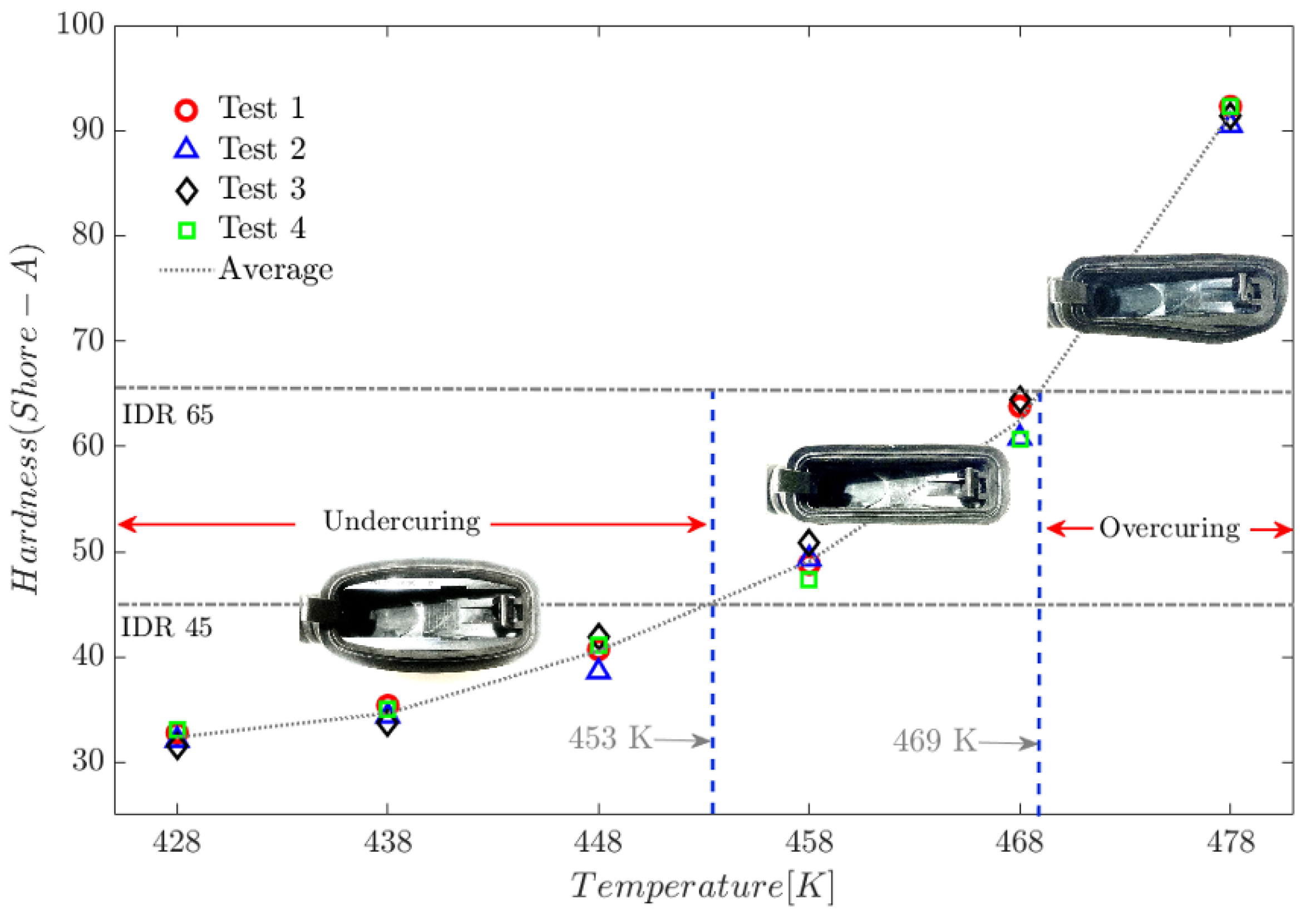

- ASTM 1415-18; Standard Test Method for Rubber Property—International Hardness. American Standard Testing for Materials ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 09.01, 2018.

- P. P, J. Neethirajan, K. M.I, R. R, and R. R, “Thermo-oxidative aging and its influence on the performance of silica, carbon black, and silica/carbon black hybrid fillers -filled tire tread compounds,” Journal of Polymer Research, vol. 32, no. 4, p. 117, 2025/04/01 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Smejda-Krzewicka and, K. Mrozowski, “Chloroprene and Butadiene Rubber (CR/BR) Blends Cross-Linked with Metal Oxides: INFLUENCE of Vulcanization Temperature on Their Rheological, Mechanical, and Thermal Properties,” Molecules, vol. 30, no. 13, p. 2780, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/30/13/2780.

- S. Gomez-Jimenez et al., “Mooney–Rivlin Parameter Determination Model as a Function of Temperature in Vulcanized Rubber Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulations,” Materials, vol. 17, no. 13, p. 3252, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/17/13/3252.

- H. Shao, Q. Guo, and A. He, “Evolution of crosslinking networks structure and thermo-oxidative aging behavior of unfilled NR/BR blends with TBIR as extra functional compatibilizer,” Polymer Testing, vol. 115, p. 107715, 2022/11/01/ 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Panyukov, “Theory of Flexible Polymer Networks: Elasticity and Heterogeneities,” Polymers, vol. 12, no. 4, p. 767, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/12/4/767.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).