1. Introduction

Traffic safety and economic sustainability are intricately linked, particularly in rapidly developing economies like Saudi Arabia. As the Kingdom undergoes transformative reforms under its Vision 2030 initiative, improving traffic safety has emerged as a critical component of its broader strategy to enhance economic performance and attract foreign investment. Traffic-related fatalities and accidents not only result in human tragedy but also impose significant economic costs, including healthcare expenditures, lost productivity, and reduced investor confidence. Understanding the nexus between traffic safety and economic sustainability is therefore essential for designing effective policies that align with Saudi Arabia’s ambitious development goals.

Road traffic accidents remain a pressing global public health concern, responsible for approximately 1.25 million deaths and up to 50 million injuries annually. Beyond the human toll, these incidents impose considerable economic burdens, costing nations an estimated 1–2% of their GDP. This underscores the critical link between traffic safety and economic sustainability, particularly in rapidly developing economies.

The launch of Saudi Arabia's Vision 2030 in 2016 signaled a pivotal shift, integrating traffic safety within a broader framework of economic diversification and sustainable development. Since then, fatalities have declined by over 35%, yet road-related injuries continue to exert an annual economic cost of US$3.2 billion, equivalent to 1.7% of GDP. The kingdom has made strides in addressing traffic safety challenges through initiatives such as the introduction of the Saher automated traffic monitoring system and substantial investments in road infrastructure. Despite these efforts, the country still faces a high rate of road traffic fatalities, with an estimated 28.7 deaths per 100,000 people as of recent years, well above global averages. This poses a direct threat to economic productivity and undermines the Kingdom’s efforts to position itself as an international hub for trade, tourism, and investment. Traffic safety is not only a public health issue but also a critical determinant of macroeconomic outcomes such as gross domestic product (GDP) growth and foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows.

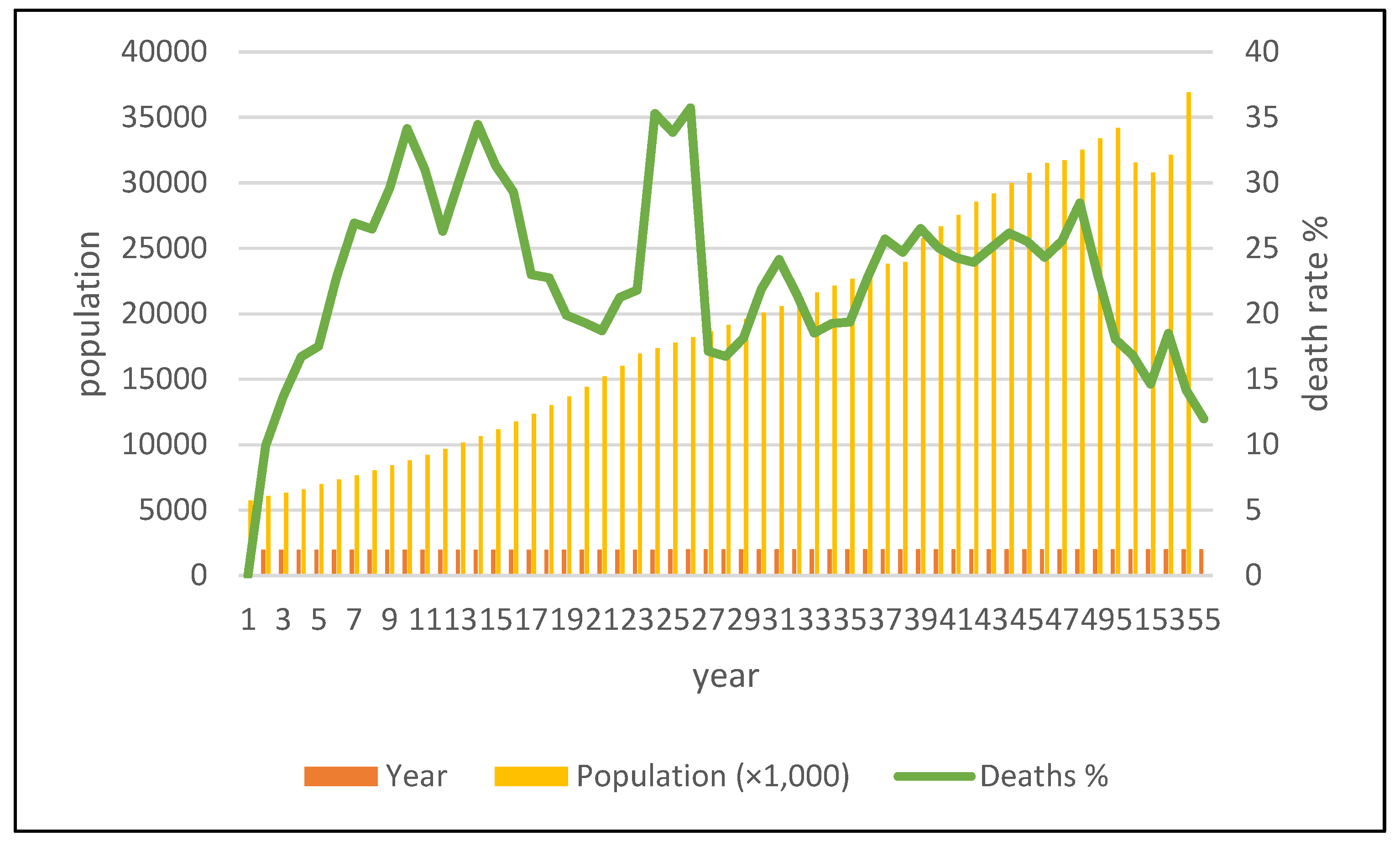

Figure 1.

Traffic accident deaths in Saudi Arabia (1970 – 2023), Population (×1,000). s). Source: Saudi Arabia General Authority for Statistics

https://www.stats.gov.sa/home (accessed on 25 March 2025).

Figure 1.

Traffic accident deaths in Saudi Arabia (1970 – 2023), Population (×1,000). s). Source: Saudi Arabia General Authority for Statistics

https://www.stats.gov.sa/home (accessed on 25 March 2025).

This study employs an econometric model to investigate the relationship between traffic safety and economic sustainability in Saudi Arabia. The model examines the impact of traffic safety on GDP growth, incorporating key variables such as foreign direct investment (FDI), government effectiveness, road quality, and security threats. This study captures short- and long-run dynamics between traffic safety indicators and economic outcomes by utilizing time-series data and applying an Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) framework. By employing the ARDL bounds testing procedure, this study not only assesses the existence of cointegration among traffic fatality rates, economic indicators, and governance variables but also quantifies the magnitude and direction of these relationships over time.

The novelty of this research lies in its focus on integrating traffic safety into the broader discourse on economic sustainability within the context of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. While previous studies have explored the economic implications of traffic accidents in other regions, limited attention has been given to how improved traffic safety can drive macroeconomic indicators such as GDP growth and FDI inflows in Saudi Arabia. This study addresses this gap by providing empirical evidence on how reducing road traffic fatalities and enhancing infrastructure quality can contribute to achieving the Kingdom’s long-term development objectives.

The findings of this study are expected to offer actionable insights for policymakers seeking to balance public health priorities with economic growth objectives. By quantifying the economic benefits of improved traffic safety, this research underscores the importance of integrating road safety measures into national development strategies. Furthermore, it highlights the role of institutional factors such as government effectiveness and infrastructure quality in mediating the relationship between traffic safety and economic sustainability.

This study aims to contribute to the growing body of literature on sustainable development by demonstrating how investments in traffic safety can yield significant economic dividends. Through robust econometric modeling and a focus on Saudi Arabia’s unique development context, this research provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the interplay between public safety and macroeconomic performance. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the methodology, including data sources, variable definitions, and analytical approach.

Section 3 reports the empirical results and analysis.

Section 4 discusses the implications of the findings for policy and practice.

Section 5 concludes with a summary of key insights and recommendations for future research.

2. Literature Review

Theoretical Background

This study adopts an integrated theoretical framework combining Institutional Theory, Sustainable Development Theory, and Human Capital Theory to examine the link between safety and economic sustainability in Saudi Arabia. Institutional Theory explains how national policies like Vision 2030 and safety regulations shape organizational behavior. Sustainable Development Theory highlights safety as a core element of long-term economic, social, and environmental stability. Human Capital Theory positions safety as an investment that enhances workforce productivity and reduces costs related to injuries and absenteeism. Together, these theories illustrate how strong safety practices, driven by policy and aligned with sustainable goals, contribute directly to economic resilience and national development.

2.1. Economic Reforms and Traffic Safety Outcomes

Saudi Arabia's transformative economic agenda, particularly under the Vision 2030 initiative, has had significant ripple effects on traffic safety outcomes, as modern infrastructure, legal reforms, and smart mobility systems are increasingly integrated. Empirical studies now document how these reforms have shaped traffic safety, revealing both progress and persistent challenges.

Economic modernization has been accompanied by legal and regulatory upgrades, with digital governance tools, such as AI-assisted surveillance and automated traffic monitoring, playing a key role in strengthening enforcement and enhancing public safety [

1,

2]. One of the earliest assessments of these reforms demonstrated that fuel price adjustments and stricter enforcement policies led to a measurable reduction in traffic volumes and accident rates, indicating that economic measures can significantly influence road user behavior by altering the financial costs of mobility [

3]. Efforts to develop smart mobility infrastructure, including intelligent transport systems (ITS), dynamic traffic control, and predictive analytics, have also supported greater compliance and faster emergency responses, reinforcing the safety benefits of integrated transport reform [

4]. Despite progress, challenges persist in merging legacy infrastructure with advanced technologies, though improved regulatory coordination and heightened safety awareness continue to emerge as positive outcomes [

5]. These developments have been further supported by educational initiatives, where the introduction of reform-driven traffic safety materials has helped instil legal awareness and reduce risky driving behaviors among younger populations [

6]. Together, these findings affirm that the Kingdom’s traffic safety advancements are intrinsically linked to its broader economic and structural transformation, reflecting a holistic approach to sustainable development. Hence, traffic safety improvements in Saudi Arabia are not solely due to standalone safety initiatives but are deeply intertwined with the Kingdom’s broader economic reforms. By enhancing enforcement capacity, introducing smart mobility infrastructure, and promoting traffic safety education, Vision 2030 has catalyzed a multifaceted improvement in road safety outcomes.

2.2. Economic Factors and Their Relationship to Traffic Safety

Economic conditions form a critical layer in understanding traffic safety outcomes, particularly in the context of Saudi Arabia's ongoing structural transformation. As the nation invests in infrastructure and reforms regulatory policy under Vision 2030, economic indicators such as GDP growth, vehicle affordability, and public spending patterns increasingly influence traffic dynamics and associated risks. Recent studies have examined the link between GDP per capita and traffic safety in Saudi Arabia. The study of [

7] found a non-linear relationship: while economic growth improves infrastructure and vehicle safety, it also increases road usage, elevating risk. This supports the "Kuznets curve for traffic fatalities," where fatalities rise during early economic growth but decline after surpassing a certain GDP threshold. The research suggests Saudi Arabia may be nearing this turning point, with Vision 2030 reforms potentially hastening safer outcomes. However, motorization rates in Saudi Arabia have surged alongside economic growth and increased access to consumer credit, contributing to higher vehicle ownership, particularly among younger drivers.

Government spending on transport infrastructure presents both benefits and trade-offs. [

8] found that while economic growth positively influences foreign direct investment (FDI), infrastructure spending in the short term may produce crowding-out effects. Over time, however, trade openness and sustained FDI contribute to long-term infrastructure improvements, which are vital for enhancing road safety outcomes. Likewise, [

9] utilized ARIMA models to forecast traffic accident trends, highlighting how economic patterns influence accident rates over time. His work supports findings that economic growth initially elevates traffic risk but eventually facilitates safer conditions through infrastructure investments.

The evolution of insurance policy is another critical economic factor. [

10] reported that the introduction of mandatory auto insurance led insurers to adjust premiums based on driver risk profiles. This created economic incentives for safer driving and greater adherence to traffic laws.

Labor market dynamics also shape traffic risks. As ride-hailing and delivery services expand, especially among gig workers, driver exposure to crashes has increased. A report by the [

11] highlighted that gig-economy drivers often work long hours under economic pressure, linking informal employment to higher road safety risks.

Additionally, fuel subsidy reforms central to Saudi Arabia’s economic diversification have influenced driving behavior. [

12] noted shifts in household transport expenditures, with more residents opting for carpooling or public transport in response to rising fuel prices.

Collectively, these economic dimensions reveal that traffic safety in Saudi Arabia is deeply embedded in financial behavior, public policy, and market structures. Moving forward, traffic safety strategies must consider the interplay between economic access, institutional incentives, and infrastructure design to achieve sustainable improvements.

2.3. Road Quality and Traffic Safety

The quality of road infrastructure is a foundational element in ensuring traffic safety, and in Saudi Arabia, it has become increasingly central to the nation's development strategy. As investments in road modernization align with Vision 2030 objectives, researchers have begun to quantify the safety benefits and ongoing gaps related to road conditions, design, and smart systems. Saudi Arabia's road quality index has risen to 5.7 in 2024, placing the Kingdom in the fourth rank among the G20 countries [

13,

14]. This represents a significant improvement in road infrastructure quality, with more than 77% of roads across Saudi Arabia meeting safety standards, exceeding the 66% targeted in the previous year [

15,

16]. This improvement is directly attributed to the Kingdom's Roads Sector Strategy that focuses on safety, quality, and traffic density. The strategy has led to the implementation of performance-based maintenance contracts, advanced bridge management systems, and enhanced monitoring of infrastructure quality, all contributing to improved safety outcomes [

17,

18].

Recent investments in smart traffic management technologies, such as the Riyadh traffic control project [

19], have also contributed to more responsive and safer road networks. The Roads General Authority's recognition for quality advancements further demonstrates Saudi Arabia's progress toward global best practices [

20].

Recent findings by [

21] highlight that advanced traffic prediction models, dependent on real-world road condition datasets, are essential for accurate congestion management and accident prevention. Using data from Saudi Arabia and Jordan, their study emphasizes the role of high-resolution road mapping in reducing collision risks through intelligent traffic systems. Similarly, [

22] examined urban traffic congestion in Saudi cities and concluded that poor road surface quality and insufficient signage significantly contribute to elevated accident rates. Their proposed intelligent transport system model showed potential to mitigate these risks through dynamic traffic routing and better infrastructure responsiveness. Complementary evidence from [

23] emphasizes the importance of integrating advanced technologies such as automated pothole detection and real-time road condition monitoring to further strengthen road safety efforts.

A separate geographic study by [

24] focused on accessibility challenges for vulnerable populations, particularly the visually impaired. Their research found that inconsistencies in pedestrian pathways, surface materials, and roadside infrastructure directly hindered safe mobility, underlining the link between road design and public safety. Similarly, [

25] explored trauma-related outcomes linked to poor road conditions and accident-prone zones, underscoring the urgency of targeted road safety interventions in areas with substandard infrastructure. Complementary studies by [

26] reveal that public perception identifies poor road quality as a leading factor in accidents in Riyadh. Additionally, recent work by [

5] examined drivers' perceptions in Riyadh and identified poor road surface maintenance as a leading factor contributing to traffic accidents, confirming that public perceptions align with empirical road quality challenges.

Therefore, prior studies affirm that road quality is not merely a technical concern but a critical public health and safety issue. Poorly maintained or poorly designed roads correlate with increased crash risks, particularly in urban environments with high traffic density. As Saudi Arabia continues its infrastructure expansion, ensuring the safety, accessibility, and inclusiveness of road networks remains essential to reducing traffic fatalities and promoting sustainable mobility.

2.4. Rule of Law and Traffic Safety

The role of legal enforcement and governance, often encapsulated in the concept of the rule of law, is essential in shaping traffic safety outcomes. In Saudi Arabia, the implementation of Vision 2030 has led to a concerted effort to strengthen traffic law enforcement, modernize legal frameworks, and increase accountability across transport-related institutions.

A systematic review by [

27] underscores the importance of legal reform in reducing road traffic accidents. The authors emphasize that effective enforcement mechanisms, such as surveillance technologies and legal penalties, are critical in promoting compliance and deterring violations. Their findings support the need for sustained legal interventions as part of national safety planning. Likewise, [

28] systematically reviewed road traffic accident determinants, highlighting legal compliance and enforcement as critical predictors of safety outcomes. In a related study, [

29] evaluated the impact of detection cameras introduced under Vision 2030. Their before-and-after analysis in Riyadh found significant improvements in compliance with seatbelt and mobile phone laws, indicating that legal enforcement tools backed by institutional authority can shift behavior effectively. Moreover, [

3] addressed the intersection of Vision 2030 and traffic safety, concluding that reforms in fuel pricing, policy enforcement, and traffic control regulations helped reduce accident rates. This study highlights how economic policies, when combined with legal oversight, support improved traffic outcomes. Further supporting this view, [

30] conducted a safety effectiveness evaluation of Saudi Arabia’s Saher automated enforcement system. The study found that increased legal accountability and digital surveillance significantly reduced accident severity, reinforcing the importance of a rules-based system. Complementing the enforcement focus, [

31] explores legal responsibilities resulting from poor road conditions. His analysis points out that under Vision 2030, legal standards are being updated to hold authorities accountable for maintaining road infrastructure, which is a critical yet under-discussed factor in traffic safety governance.

Accordingly, these studies affirm that Saudi Arabia’s recent gains in traffic safety are strongly linked to legal enforcement, rule of law principles, and institutional reforms introduced under Vision 2030. Legal accountability via detection systems, traffic law education, and infrastructure liability is increasingly central to national traffic safety outcomes.

2.5. Integrated Approaches to Traffic Safety and Economic Sustainability

In recent years, scholars and international institutions have increasingly emphasized the value of integrated approaches that connect traffic safety with broader economic sustainability goals. In Saudi Arabia, this intersection is gaining momentum under the Vision 2030 framework, which promotes cross-sectoral strategies that simultaneously enhance mobility safety, economic resilience, and institutional reform.

A prominent example of this integrated perspective is presented by [

1], who argue that economic modernization and legal innovation, especially through digital governance, are critical for advancing both safety and development objectives. Research by [

32] explored the nexus between sustainable green mobility and reduced emissions, arguing that sustainable transport frameworks must incorporate safety features alongside environmental considerations. Meanwhile, AI applications like camel-vehicle collision detection systems developed by [

33] showcase how computer vision and machine learning can enhance rural and highway safety. This perspective aligns closely with systems-thinking models in transport policy, such as the “Safe System” approach advocated by [

34,

35]. These frameworks emphasize that safety cannot be addressed in isolation; it must be embedded within legal, environmental, and economic development structures. When governments integrate infrastructure funding, regulatory enforcement, and smart mobility systems into their economic planning, they not only lower crash rates but also improve logistics performance, healthcare cost efficiency, and overall workforce participation. In the Saudi context, early findings by [

3] demonstrated that regulatory modernization and fuel pricing reforms under Vision 2030 helped reduce accident rates while promoting fiscal stability. Similarly, [

26] reported that the implementation of automated detection systems (e.g., Saher) significantly improved driver compliance, showcasing how integrated legal and technological measures can reduce the socioeconomic burden of road traffic injuries.

Moreover, recent reforms in infrastructure funding and insurance regulation have introduced economic incentives for safe behavior. Variable-rate premiums based on driver history and expanding intelligent transportation systems (ITS) are part of a growing “safety-economy nexus,” where tools like smart taxation and foreign direct investment (FDI) policies serve dual purposes: promoting public safety and enhancing national productivity.

Therefore, these global and local insights signal a strategic shift: traffic safety is no longer viewed merely as a public health challenge but as a cross-cutting issue that demands coordination across urban planning, economic policy, legal enforcement, and digital transformation. For Saudi Arabia, embracing this convergence model offers a clear path to achieving long-term economic sustainability through safer, smarter mobility systems.

2.6. Review of ARDL Applications and the Unique Contribution of This Study

The Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model has gained popularity in Saudi economic research for its flexibility in analyzing short- and long-run dynamics across integrated variables. Several studies have applied the ARDL framework to explore macroeconomic indicators such as transport sector growth, oil prices, consumer price indices, and economic complexity. For instance, [

36] used ARDL to evaluate the impact of Saudi Arabia’s transport and communication sectors on economic growth, confirming their significance as growth drivers.

Similarly, [

37] applied ARDL to assess the effects of Vision 2030 reforms on the Consumer Price Index, capturing how infrastructure-related sectors influence price stability and, indirectly, safety-relevant spending behavior. While these applications highlight the ARDL model’s robustness in economic research, they largely omit traffic safety as a primary outcome variable. Existing ARDL studies focus on aggregate macroeconomic indicators or sector-specific effects without integrating traffic safety metrics, legal enforcement indices, or infrastructure quality as dependent variables.

This study is distinct in its attempt to bridge economic and safety domains using an ARDL-VECM framework. By integrating variables such as GDP per capita, FDI, road infrastructure quality, and traffic fatality rates, this research provides a novel contribution to the literature. It also incorporates rule of law indicators as moderators—rarely addressed in prior Saudi-focused ARDL studies—thereby offering a multidimensional understanding of how institutional and economic forces jointly influence traffic safety under the Vision 2030 agenda.

Research shows that Vision 2030 reforms have significantly improved traffic safety in Saudi Arabia, with fuel pricing, FDI, and infrastructure upgrades reducing accidents and fatalities. Studies confirm a non-linear link between economic growth and safety, with Saudi Arabia now positioned to benefit from further development. Improvements in road quality and legal enforcement, including systems like Saher, have enhanced compliance and reduced risks. Integrated models highlight the mutual benefits between economic sustainability and safety, including lower healthcare costs and improved productivity. Still, gaps remain in understanding long-term impacts, demographic differences (e.g., female drivers), and the role of FDI and emerging technologies. Comparative research with other economies is also needed. This study aims to address some of these gaps by examining the specific relationships between traffic fatality rates (dependent variable), GDP per capita as a proxy for sustainability, foreign direct investment, and road quality index (independent variables), with the rule of law as a control variable. By testing these relationships in the context of Saudi Arabia's economic transformation under Vision 2030, the study will contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the nexus between safety and economic sustainability.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study employs a quantitative research design to examine the relationship between traffic fatality rates and economic factors in Saudi Arabia. A cross-sectional time-series analysis approach is utilized to investigate how gross domestic product per capita (GDPC), foreign direct investment (FDI), and quality of road index (QRI) influence traffic fatality rates, while controlling for the rule of law (RLI). This methodological approach allows for the examination of both the direction and magnitude of relationships between the dependent and independent variables over time, providing insights into the dynamic interplay between economic sustainability and traffic safety outcomes in the Saudi context.

3.2. Data Sources and Collection

The study utilizes secondary data from multiple authoritative sources to ensure reliability and validity. Data for the period 1990-2023 is collected to capture recent trends and the impact of Vision 2030 initiatives implemented since 2016. The specific data sources for each variable are as follows:

Dependent Variable

Traffic Fatality Data: Annual traffic fatality rates (per 100,000 population) measure the number of deaths due to road traffic accidents per 100,000 population annually. obtained from the Saudi General Authority for Statistics, the Ministry of Interior's Traffic Department, and the World Health Organization's Global Status Report on Road Safety.

Independent Variables

Gross Domestic Product per Capita (GDPc): Measured in constant US dollars, this variable serves as a proxy for economic sustainability and captures the overall economic development level of Saudi Arabia. GDPC reflects a nation's capacity to invest in safety infrastructure and implement effective regulations. Data on GDP per capita is sourced from the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA) and the World Bank's World Development Indicators database.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): Measured as net inflows as a percentage of GDP. This variable captures the level of international investment in the Saudi economy, which may influence infrastructure development, technology transfer, and economic diversification. FDI data is collected from the Saudi Ministry of Investment and the World Bank's Foreign Direct Investment database.

Quality of Road Index: Measured on a scale of 1-7, with higher values indicating better quality road infrastructure. This variable directly assesses the physical condition and quality of the road network, which can significantly impact traffic safety outcomes. Quality of Road Index data is obtained from the Saudi Ministry of Transport and the World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Report.

The Control Variable

Rule of Law Index: Measured on a scale of 0-1, with higher values indicating stronger rule of law. This variable controls for the institutional environment that affects the implementation and enforcement of traffic regulations. Data on the rule of law is sourced from the World Bank's Worldwide Governance Indicators. This index captures perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, particularly the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts.

3.3. Model Specification and Estimation Techniques

The cointegration test determines whether a long-run equilibrium relationship exists among non-stationary variables that move together over time despite short-term fluctuations. Given that the study's variables are non-stationary in levels but may move together over time due to underlying economic and institutional linkages, cointegration analysis ensures that their relationships are not spurious. Establishing cointegration is a critical prerequisite for applying long-run estimation techniques such as the ARDL model, VECM, and Canonical Cointegrating Regression (CCR). This approach strengthens the validity of the empirical findings by confirming that observed associations reflect genuine economic dynamics rather than random trends.

For a set of variables Yt, X1t, X2t, ..., Xkt, the cointegration equation can be written as:

where:

Yt: Dependent variable (traffic fatality rate)

Xkt: Independent variables (GDP per capita, FDI, road quality, rule of law)

βk: Long-run coefficients

α: Constant term

ut: Error term (should be stationary, i.e., I(0), for cointegration to exist)

The multivariate Johansen approach uses a Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) form:

Zt: Vector of all endogenous variables (e.g., [Yt, X1t, X2t, ..., Xkt)

Π: Long-run impact matrix (rank of Π = number of cointegrating vectors)

Γi: Short-run adjustment coefficients

εt: White noise error term.

Canonical Cointegrating Regression (CCR) estimates the long-run relationship while correcting for endogeneity and serial correlation:

However, unlike standard OLS, CCR transforms Y

t and X

kt using stationary components to yield:

where Y

t* and X

kt* are the transformed variables that correct for serial correlation and endogeneity, enabling efficient and unbiased estimation of β

k. This provides asymptotically efficient long-run estimates.

Once cointegration is confirmed, ARDL can be expressed in its Error Correction Model (ECM) form:

- ▪

Δ: First difference operator.

- ▪

λ: Error correction term (ECT) coefficient, showing speed of adjustment.

- ▪

The term in parentheses: the lagged residual from the long-run equation (i.e., cointegration residual).

A significant and negative λ confirms long-run equilibrium adjustment.

In addition, multiple regression models are estimated using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) with robust standard errors for potential heteroscedasticity. Furthermore, fixed-effects and random-effects models are estimated to address potential endogeneity concerns and unobserved heterogeneity.

Moreover, the study uses the Ramsey RESET test for model specification diagnostic tests are performed to ensure the validity of the regression results:

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics table provides insights into the distribution and characteristics of five key variables: LnDeaths, LnFDI, LnGDPC, LnQRI, and LnRLI, based on 34 observations. The mean and median values indicate that traffic-related deaths (Deaths) are relatively stable, with a slight left skew. LnFDI has a negative mean and the highest standard deviation (1.40), indicating significant fluctuations. LnGDPC shows moderate variation and is closer to a normal distribution, while the LnQRI and LnRLI exhibit considerable variation, with road infrastructure having the widest range (-9.210 to 1.785).

Skewness and kurtosis values suggest that LnFDI is highly left-skewed with heavy tails, while LnQRI is slightly right-skewed but flatter than a normal distribution. The Jarque-Bera test results indicate that LnFDI (p = 0.0137) is not normally distributed, whereas LnDeaths, LnGDPC, and LnRLI do not significantly deviate from normality. These findings highlight the substantial variability in FDI and road infrastructure quality, which may have important economic and traffic safety modeling implications. The relative stability of traffic deaths suggests a more predictable pattern. In contrast, road quality and governance factors show significant fluctuations, warranting further analysis of their effects on safety and economic sustainability.

Table 1.

The descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

The descriptive statistics.

| Statistic |

LnDeaths |

LnFDI |

LnGDPC |

LnQRI |

LnRLI |

| Mean |

3.075052 |

-0.10431 |

0.940273 |

-5.05803 |

-4.26297 |

| Median |

3.131102 |

0.099015 |

1.178537 |

-5.35706 |

-2.41416 |

| Maximum |

3.576023 |

2.813411 |

2.396988 |

1.78507 |

3.912023 |

| Minimum |

2.526552 |

-4.60517 |

-1.27536 |

-9.21034 |

-11.5129 |

| Std. Dev. |

0.267846 |

1.400106 |

1.030472 |

3.55706 |

3.175621 |

| Skewness |

-0.319836 |

-0.87726 |

-0.68256 |

0.484417 |

-0.75207 |

| Kurtosis |

2.788644 |

4.724357 |

2.544709 |

1.234985 |

2.190234 |

| Jarque-Bera |

0.642955 |

8.573286 |

2.933725 |

5.743053 |

2.543856 |

| Probability |

0.725077 |

0.013751 |

0.230648 |

0.056612 |

0.280291 |

| Sum |

104.5518 |

-3.54644 |

31.96927 |

-171.973 |

-144.941 |

| Sum Sq. Dev. |

2.367467 |

64.77388 |

35.65658 |

947.0369 |

745.3782 |

| Observations |

34 |

34 |

34 |

34 |

34 |

4.2. Correlation Test

The correlation matrix reveals key relationships between traffic deaths and economic, infrastructural, and governance indicators. Based on

Table 2, there is a weak positive correlation between LnDeaths and both FDI (0.0672) and GDP per capita (0.1008), suggesting that economic growth and investment have minimal direct impact on traffic fatalities. However, LnQRI shows a moderate positive correlation (0.2737) with traffic deaths, indicating that better roads may inadvertently contribute to higher fatality rates, possibly due to increased vehicle speeds or riskier driving behavior. Conversely, the rule of law index (LnRLI) has a moderate negative correlation (-0.2618) with LnDeaths, implying that stronger governance and enforcement mechanisms help reduce fatalities. Additionally, FDI and GDP per capita exhibit a moderate positive correlation (0.4699), reinforcing the idea that foreign investment contributes to economic growth.

However, FDI’s weak negative correlation with road quality (-0.2493) suggests that higher investment does not necessarily translate into better infrastructure. The moderate positive correlation between LnQRI and LnRLI (0.3403) indicates that countries with better governance tend to have higher road quality. Overall, the findings suggest that while economic growth and investment play indirect roles in traffic safety, governance effectiveness and infrastructure development policies must be carefully managed to minimize unintended safety risks.

4.3. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression Test

The regression results in

Table 3 reveal that among the predictors of LnDeaths, LnRLI and LnQRI are statistically significant, with LnRLI exerting a negative effect (coefficient = -0.0230, p = 0.0065). LNQRI has a positive effect (coefficient = 0.0227, p = 0.0053), suggesting that stronger legal frameworks reduce traffic accident density, while improved infrastructure may be associated with increased road usage or better reporting. In contrast, LNGDPC shows no significant impact on LnDeaths (p = 0.9175), and LnFDI has a positive but statistically insignificant effect (p = 0.1250), indicating limited explanatory power for these economic variables in this model. The constant term is large and highly significant, reflecting a strong baseline level of LnDeaths independent of the explanatory variables.

4.4. Unit Root test

The Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) unit root test was conducted to examine the stationarity of the variables. Based on

Table 4, at level, the variables LNROL, LNQRI, and LNTAD failed to reject the null hypothesis of a unit root, as their test statistics (–1.90, –1.44, and –1.71, respectively) are greater than the critical values at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, with corresponding p-values above 0.05. In contrast, LNGDPC and LNFDI were found to be stationary at level, as their ADF statistics (–4.66 and –6.11, respectively) are more negative than the 1% critical value, and their p-values are statistically significant at 1%. After first differencing, LNROL, LNQRI, and LNTAD became stationary, with test statistics (–20.29, –5.48, and –5.37, respectively) well below the 1% critical value and p-values equal to 0.00, indicating strong rejection of the null hypothesis. These results suggest that all variables are either I(0) or I(1), justifying the suitability of applying the ARDL modeling approach.

4.5. VAR Lag Order Selection Criteria

The VAR (Vector Autoregressive) Lag Order Selection Criteria table helps determine the optimal number of lags to include in a VAR model, which is crucial for accurately modeling the relationships between the endogenous variables LnDeaths, LnFDI, LnGDPC, LnQRI, and LnRLI. The selection is based on multiple statistical criteria, including Final Prediction Error (FPE), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Schwarz Information Criterion (SC), and Hannan-Quinn Criterion (HQ).

Table 5 evaluates three lag lengths (0, 1, and 2) based on their Log-Likelihood (LogL), Likelihood Ratio (LR) test, and information criteria. A lower value of FPE, AIC, SC, and HQ generally indicates a better model fit. The asterisks (*) indicate the preferred lag order selected by each criterion. Based on the selection criteria, Lag 2 is the optimal lag length for the VAR model, as it minimizes FPE, AIC, and HQ, which are widely used in time series analysis. This means that the relationships between traffic deaths, FDI, sustainability (LN_GDPC), road quality, and governance should be modeled using a VAR(2) process to capture the dynamic interactions between these variables best.

VAR Model Specification

The results of the VAR Residual Serial Correlation LM Test in

Table 6 confirm that the residuals of the estimated VAR model are free from serial correlation, thereby validating one of the key assumptions of VAR modeling. The test was conducted for lags 1 through 3. In each case, the p-values associated with both the Lagrange Multiplier (LRE) statistic and the Rao F-statistic* were well above the conventional 5% significance level. Specifically, the p-values for lag 1 were 0.4882 (χ²) and 0.5092 (F); for lag 2, 0.7116 and 0.7271; and for lag 3, 0.2658 and 0.2860, respectively. Since all p-values exceed 0.05, we fail to reject the null hypothesis that no serial correlation exists in the residuals at any of the tested lags. This indicates that the residuals behave like white noise and are not influenced by their past values, thereby supporting the statistical reliability, dynamic specification, and predictive validity of the VAR model used in the study. In the context of analyzing the long-run and short-run dynamics among sustainability and road safety factors in Saudi Arabia, this finding enhances confidence in the model’s capacity to produce robust and unbiased estimates.

4.6. Cointegration Tests

4.6.1. Canonical Test

The Canonical Cointegrating Regression (CCR) results for the dependent variable LnDeaths show the long-run relationships between traffic fatalities and key economic and governance indicators. The estimated coefficients in

Table 7 suggest that LnFDI has a positive but statistically insignificant effect (0.0329, p = 0.5692), implying that changes in FDI do not significantly influence traffic deaths in the long run. Similarly, GDP per capita also has a positive but insignificant effect (0.0518, p = 0.3737), indicating that economic growth alone does not directly impact fatality rates. However, LnQRI is positively and statistically significant (0.0272, p = 0.0143), suggesting that improvements in road quality may unintentionally lead to higher fatalities, potentially due to increased speeds or riskier driving behavior on better roads. On the other hand, LnRLI exhibits a negative and significant effect (-0.0409, p = 0.0070), highlighting that stronger legal enforcement and governance contribute to reducing traffic deaths.

These findings have important policy implications. While economic growth and investment alone do not appear to drive traffic safety improvements, governance and legal enforcement play a critical role in reducing fatalities. Additionally, the counterintuitive result that improved road infrastructure correlates with higher deaths suggests that infrastructure development should be coupled with strict safety regulations, enforcement of speed limits, and driver education programs to mitigate unintended risks.

4.6.2. Johanson Test

The Maximum Eigenvalue Test for cointegration in

Table 8 reveals the presence of three cointegrating equations at the 5% significance level, indicating a strong long-run equilibrium relationship among the variables. The null hypothesis of no cointegration is rejected as the Max-Eigen Statistic (60.35) exceeds the critical value (33.88) with a p-value of 0.0000, confirming at least one cointegrating equation. Similarly, the hypotheses for at most one and two cointegrating relationships are also rejected, with test statistics exceeding their respective critical values and p-values of 0.0038 and 0.0382, respectively. However, the hypothesis for at most three cointegrating equations is not rejected (p = 0.8683), suggesting that the system contains exactly three stable long-run relationships. This finding implies that despite short-term fluctuations, the variables potentially including traffic deaths, GDP per capita, road infrastructure quality, and governance, tend to move together over time. The presence of cointegration suggests that a Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) would be the appropriate approach for capturing both short-term dynamics and long-run equilibrium adjustments. From a policy perspective, this result underscores the importance of considering long-term dependencies between economic, governance, and infrastructure variables when designing interventions to improve road safety and economic sustainability.

4.6.3. Error Correction Model (ECM) Test

The ECM presented in the table explores the dependent variable's short-run dynamics and long-run adjustments, as well as the change in the logarithm of Deaths. Based on

Table 9, short-run estimates indicate minimal significance, with LnRLI, LnQRI, and LnGDPC all failing to show statistically significant relationships, suggesting that these variables do not immediately affect Deaths in the short run. Conversely, LnFDI demonstrates a positive relationship at a marginal significance level (p-value = 0.0864), indicating a moderate short-run influence. Importantly, the Error Correction Term (ECT) is negative (-0.4129) and statistically significant (p-value = 0.0385), validating the presence of a stable long-run equilibrium relationship among the variables. This implies that approximately 41.3% of any short-run deviations from equilibrium are corrected annually, demonstrating a moderate adjustment speed. Therefore, the ECM confirms robust long-run dynamics, highlighting the importance of long-term structural adjustments rather than immediate short-term changes.

ARDL error correction regression results in

Table 10 indicate significant short-run inertia effects from the lagged dependent variable, highlighting the persistence of previous shocks on current changes. LnRLI demonstrates delayed positive effects, particularly evident at the second and third lags, suggesting a time-dependent influence. LnQRI initially shows a marginally significant positive short-run impact, followed by a highly significant negative correction, reflecting short-term fluctuations. However, LnFDI exhibits complex short-run dynamics, with an initial positive effect followed by significant negative corrections at subsequent lags. Crucially, the cointegration term is negative and highly significant (-0.5538, p < 0.01), indicating that roughly 55.4% of deviations from the long-run equilibrium are adjusted annually, signifying a rapid correction mechanism. With strong explanatory power (R² = 0.7166) and no severe autocorrelation issues (Durbin-Watson = 2.5974), the model robustly confirms the existence of meaningful short- and long-term dynamics affecting traffic accident deaths in Saudi Arabia.

4.6.4. Stability Diagnostics Test of the Model

The Ramsey RESET test evaluates whether a regression model is correctly specified by detecting omitted variables or incorrect functional form through added powers of the fitted values. The results in

Table 11 indicate that the ARDL model is correctly specified, with no evidence of omitted variable bias or functional form misspecification. All test statistics, the t-statistic (0.1688), F-statistic (0.0285), and likelihood ratio (0.0776), are associated with high p-values (0.8690 and 0.7805), which are well above the conventional significance thresholds. This means the null hypothesis of correct model specification cannot be rejected, suggesting that the functional form of the model is appropriate and that no major nonlinear relationships or missing variables are distorting the regression results

4.7. Granger Causality Test

The Granger causality test explores whether past values of one variable can predict another, identifying possible causal relationships. In this analysis, LnGDPC serves as a proxy for sustainability, reflecting long-term economic and social development. The Key findings of

Table 12 can be summarized as follows:

• LnDeaths → LnRLI (F = 4.66336, p = 0.0182): Traffic accident deaths Granger-cause changes in the rule of law index, suggesting that higher fatality rates might lead to stronger governance or regulatory responses in Saudi Arabia. This result suggests reactive institutional strengthening in response to safety crises.

• LnFDI → LnRLI (F = 5.11219, p = 0.0131): FDI Granger-causes rule of law improvements, possibly reflecting that foreign investment demands legal and institutional reforms to ensure contract enforcement and stability. Furthermore, the result reinforces the idea that external capital can improve institutional quality.

• LnQRI → LnFDI (F = 3.73340, p = 0.0370): Road quality Granger-causes FDI inflows, indicating that better infrastructure attracts foreign investors, consistent with economic development theory.

For all other pairwise tests, the null hypothesis cannot be rejected, meaning no Granger causality is detected at the 5% significance level. These include:

- -

No causality between LnQRI and LnDeaths in either direction.

- -

No evidence that LnGDPC is Granger-caused by or Granger-causes any of the variables.

- -

No feedback between LnFDI and LnDeaths, LnRLI, LnGDPC.

- -

No evidence of mutual or unidirectional prediction between rule of law and road quality, or between GDP per capita and other variables.

In conclusion, the findings highlight that while infrastructure development and foreign investment play a pivotal role in shaping institutional quality in the short term, improvements in economic sustainability, as measured by GDP per capita, are likely driven by longer-term dynamics rather than immediate interactions with road safety, governance, or investment flows. This underscores the need for integrated, long-horizon policy planning that aligns infrastructure and regulatory reforms with broader economic development goals in Saudi Arabia.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study contribute significantly to the growing body of literature examining the intersection of traffic safety and economic sustainability, particularly in the context of Saudi Arabia's Vision 2030. The results reveal a complex but compelling relationship between institutional strength, infrastructural development, and macroeconomic performance. In line with [

27] and [

28], the study finds that improvements in the rule of law significantly reduce traffic-related fatalities. The negative and statistically significant coefficient for the rule of law index supports the hypothesis that stronger legal enforcement mechanisms, particularly those embedded within digital surveillance systems such as SAHER, play a pivotal role in enhancing public safety outcomes. This finding is congruent with the observations of [

26] and [

2], who emphasized the importance of legal frameworks in deterring violations and fostering compliance. Notably, the Granger causality test also indicates that FDI inflows predict improvements in institutional governance, suggesting that economic liberalization and global capital mobility can indirectly promote safety by enhancing regulatory environments. Recent work by [

38] further supports this trend, recognizing Saudi Arabia for implementing the world’s largest road assessment, which has helped shape national safety upgrades.

However, the study also presents a somewhat counterintuitive result: higher quality of road quality is associated with increased traffic fatalities in the long run. While infrastructure improvements are generally expected to enhance safety, the positive and significant coefficient for road quality (LnQRI) aligns with findings by [

17] and [

18], who caution that better roads can lead to increased vehicle speeds and risk-taking behavior in the absence of strict enforcement. This underscores the importance of coupling infrastructure development with behavioral interventions and law enforcement. In this regard, the Safe System approach recommended by the [

30] is particularly relevant, advocating for a comprehensive framework that integrates road design, vehicle safety, and post-crash response. Supporting this integrated view, the [

39] highlighted that Saudi Arabia reduced road crash deaths by nearly 35% over five years through a whole-of-government commitment, including the creation of a Ministerial Committee for Traffic Safety. This is reinforced by [

40], who emphasized the role of smart mobility systems in improving traffic efficiency and reducing risks, particularly in urban environments.

Moreover, the empirical evidence shows that GDP per capita and FDI, while important economic indicators, do not exert a statistically significant direct impact on traffic safety outcomes within the study period. This finding diverges from earlier work by [

6], who suggested a non-linear Kuznets-type relationship between economic growth and traffic safety. Instead, the results of this study suggest that economic growth alone is insufficient to drive improvements in traffic safety without concurrent institutional and infrastructural reforms. While [

8] emphasized the positive role of sustained FDI and trade openness in infrastructure development, this study's findings imply that such effects may be lagged or mediated by governance quality. A broader public health perspective is also highlighted by [

41], who report that in 2016, Saudi Arabia experienced over 9,000 road traffic fatalities, equivalent to one death per hour, emphasizing the socio-economic urgency of effective safety interventions. Additional risk factors, such as camel-vehicle collisions, were explored in the studies by [

42], which employed deep learning models for camel detection, underscoring the value of AI-based tools in addressing region-specific hazards.

The results from the ARDL and ECM models further affirm the long-run cointegrating relationship among traffic safety, institutional governance, and road quality, even as short-run effects appear limited. The significant and negative error correction term in both models validates the model's convergence to equilibrium and reinforces the argument that structural improvements, not short-term fluctuations, govern the trajectory of traffic safety. Additionally, the Ramsey RESET test confirms that the model is correctly specified, adding further credibility to the robustness of the results. Other model-based studies, such as those using Bayesian networks, support this finding by showing that systemic and policy-level changes, rather than isolated financial metrics, are the key levers for reducing accident consequences.

In light of these insights, this study not only confirms but also extends prior literature by explicitly demonstrating that traffic safety improvements in Saudi Arabia are driven more by legal and infrastructural reforms than by macroeconomic expansion alone. The observed interplay between FDI, rule of law, and infrastructure quality reinforces the notion of a "safety-economy nexus," wherein institutional strength and physical development must evolve in tandem. Policymakers should therefore prioritize integrated policy approaches that link economic planning with safety regulation, infrastructure investment, and legal accountability. Furthermore, future studies should investigate demographic factors, behavioral risks, and regional disparities to deepen understanding and support more targeted interventions. Comparative research with other Gulf or emerging economies would also provide valuable benchmarks and contextual validation for the generalizability of these findings.

6. Conclusions

This study offers compelling empirical evidence that traffic safety is not merely a public health concern but a critical dimension of economic sustainability in the context of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. By employing a comprehensive ARDL-ECM framework supported by cointegration techniques, the research establishes that improvements in the rule of law and road quality are statistically significant drivers of long-run traffic safety outcomes. However, it also highlights an important paradox: while infrastructure upgrades are central to economic modernization, their safety benefits can be offset if not paired with robust regulatory enforcement and behavioral interventions.

The study’s findings reveal that macroeconomic indicators such as GDP per capita and FDI do not directly influence traffic fatality rates in a significant manner. Instead, the quality of governance and the structural integrity of infrastructure emerge as more powerful determinants. These insights reinforce the need to view traffic safety through an institutional and systems-thinking lens, where economic liberalization, legal reform, and smart infrastructure investment must advance in coordination.

In policy terms, this research underscores the necessity of a multi-pronged approach that integrates safety governance into national development strategies. Tools such as automated enforcement (e.g., Saher), AI-powered risk detection systems, and risk-based insurance schemes should be scaled up to complement infrastructure investments. Furthermore, the government must continue to institutionalize safety within regulatory frameworks, especially through data-driven planning, cross-sector collaboration, and regional customization.

From an academic perspective, this study advances the literature by operationalizing a “safety-economy nexus” that ties legal efficacy, investment behavior, and transport system design into a unified explanatory model. Future research should expand this framework by incorporating behavioral variables, spatial dimensions, and comparative analyses with peer economies. Understanding how safety performance evolves under different governance models and economic configurations will be vital for generalizing the findings beyond Saudi Arabia.

In conclusion, the path to sustainable economic development in Saudi Arabia is inextricably linked to road safety governance. By embedding traffic safety at the core of economic policy, Saudi Arabia can not only save lives but also build a resilient, investor-friendly, and productivity-enhancing transport ecosystem.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

While the present study makes significant contributions to the understanding of traffic safety and economic sustainability, it is not without limitations. First, the analysis is constrained by the availability and granularity of data, particularly for variables such as law enforcement intensity, driver behavior, and disaggregated accident characteristics. Second, the use of national-level data may mask regional disparities in infrastructure quality, enforcement practices, and demographic vulnerabilities, which could provide more localized insights. Third, the models assume linear relationships and may not fully capture complex, non-linear interactions or behavioral feedback loops. Additionally, potential endogeneity between economic growth and safety outcomes, while partially addressed through model specification, may still affect the interpretation of causality.

Future research should consider adopting mixed-method approaches that integrate quantitative modeling with qualitative field data to better capture behavioral and institutional nuances. Expanding the scope to include gender- and age-specific risk factors, especially in light of increasing female participation in driving post-2018 reforms, could yield critical insights. Moreover, incorporating technological variables such as autonomous vehicle penetration, AI-based surveillance, and real-time data analytics would enrich the explanatory power of future models. Finally, comparative studies across Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries or other rapidly developing economies would enhance external validity and facilitate regional policy learning in pursuing integrated, sustainable mobility systems.

Funding

This research received funding from the University of Tabuk under Research Grant No. S-2024-0267.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author extends his appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at the University of Tabuk for funding this work through Research No. S-1444-0122.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest

References

- Mansour, N. , & Vadell, L. M. B. Finance and Law in the Metaverse World. Springer, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alobaidallah, A. M. , Alqahtany, A., & Maniruzzaman, K. M. Assessment of the Saher System in Enhancing Traffic Control and Road Safety: Insights from Experts for Dammam, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 2025, 17, 3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahim, M. A. H. Impact of Vision 2030 on Traffic Safety in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 2018, 5, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanazi, F. Development of Smart Mobility Infrastructure in Saudi Arabia: A Benchmarking Approach. Sustainability, 2023, 15, 3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatar, K. M. Smart Transportation Planning and its Challenges in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Sustainable Futures, 2024, 6, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. M. , & Al-Mansour, A. I. Development of New Traffic Safety Education Material for the Future Drivers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of King Saud University – Engineering Sciences, 2020, 32, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sulaie, S. Sensitivity Analysis of Factors Affecting Consequences Due to Traffic Crashes: A Bayesian Network Modelling. Journal of Road Safety, 2025, 36, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL SHAMMRE, Abdullah Sultan; ALSHAHRANI, Mariam Nasser. A Dynamic Analysis of Sustainable Economic Growth and FDI Inflow in Saudi Arabia Using ARDL Approach and VECM Technique. Energies, 2024, 17.18: 4663.

- AL SULAIE, Saleh. Use of ARIMA Model for Forecasting Consequences Due to Traffic Crashes in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Road Safety, 2024, 35.4: 54-65.

- Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA). Annual Insurance Market Report, 2022. Available at https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/annual-report.

- Farah, J. , AlZoubi, A. R., Ijaz, M., AlSaied, A. R., AlWohaibi, R., AlMazour, B.,... & AlMughairy, A. Urban Development in Arab Cities: Challenges, Priorities and Capacity of Actions., 2023. Urban-Development-in-Arab-Cities-Challenges-Priorities-and-Capacity-of-Actions. (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Saudi General Authority for Statistics (2022). https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/web/guest/home. (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Saudi Mobility Consulting. (2024). Enhancing Road Safety and Mobility with Smart Traffic Systems. https://saudimobilityconsulting.

- Zawya. Saudi Arabia ranks 4th in road quality index among G20 countries, 2024. https://www.zawya. (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Alfaki, I. A. Tracking Road Safety Efficiency Gains Over Time Within the Gulf Cooperation Council Region. The Open Transportation Journal, 2024,18(1).

- Economy Middle East. Saudi Arabia tops Arab region in quality infrastructure rankings, climbs 25 spots globally, 2024. https://economymiddleeast. (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Alobaidallah, A. M. , Alqahtany, A., & Maniruzzaman, K. M. Assessment of the Saher System in Enhancing Traffic Control and Road Safety: Insights from Experts for Dammam, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 2025, 17, 3304. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Press Agency (SPA). Saudi Arabia implements performance-based maintenance contracts and bridge management systems to enhance infrastructure, 2024. https://www.spa.gov.sa/en/N2181098. (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- TransCore. Riyadh officials select TransCore to deploy traffic management system in Saudi Arabia’s largest city, 2024. https://transcore.com/riyadh-officials-select-transcore-to-deploy-traffic-management-system-in-saudi-arabias-largest-city.html. (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Saudi Press Agency (SPA). Saudi Arabia’s Roads General Authority recognized internationally for quality infrastructure advancements, 2024. Retrieved from https://www.spa.govgov.sa/en/N2194611. (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Qaddoura, R. , Younes, M. B., & Boukerche, A. Towards optimal tuned machine learning techniques based vehicular traffic prediction for real roads scenarios. Ad Hoc Networks, 2024, 161, 103508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam Rahmani, M. K. , Khan, S., Ahmed, M. E., & Jawad, K. An Intelligent Transport System for Prediction of Urban Traffic Congestion Level. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science & Applications, 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroudi, U. , BaHamid, A., Elalfy, Y., & Al Alami, Z. Enhancing Pothole Detection and Characterization: Integrated Segmentation and Depth Estimation in Road Anomaly Systems. 2025; arXiv:2504.13648. https://arxiv.org/abs/2504. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shahrani, A. , Alghamdi, A., Alqurashi, A., & Alzahrani, R. Real-Time Comprehensive Assistance for Visually Impaired Navigation. IJCSNS 2024, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almallah, A. M. , Albattah, G. A., Altarqi, A. A., Al Sattouf, A. A., Alameer, K. M., Hamithi, D. M.,... & AlShammri, M. Epidemiological Characteristics of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury in Saudi Arabia: A Systematic Review. Cureus, 2024, 16. https://www.ksa.directory/saudi-arabia-s-road-quality-index-hasrisen-to-5-7-placing-the-kingdom-in-fourth-rank-among-the-g20-countries/1539/n. (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Almatar, K. M. Perception of drivers toward road safety and factors that cause road accidents in Riyadh city of Saudi Arabia. Frontiers in Built Environment, 2024, 10, 1367553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, E. Z. , AlQahtani, A. M., Althunayan, S. F., Alanazi, A. S., Aldosari, A. O., Alharbi, A. M.,... & Alanazi Sr, S. S. Prevalence and determinants of road traffic accidents in Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. Cureus, 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, E. Z. , AlQahtani, A. M., Althunayan, S. F., Alanazi, A. S., Aldosari, A. O., Alharbi, A. M.,... & Alanazi Sr, S. S. Prevalence and determinants of road traffic accidents in Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. Cureus, 2023; 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghnam, S. , Towhari, J., Alkelya, M., Binahmad, A., & Bell, T. M. The effectiveness of introducing detection cameras on compliance with mobile phone and seatbelt laws: a before-after study among drivers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Injury epidemiology, 2018, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ahmadi, H. M. Analysis of traffic accidents in Saudi Arabia: safety effectiveness evaluation of SAHER enforcement system. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, 2023, 48, 5493–5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaibani, M. N. The Legal Responsibility Resulting from Deteriorating Road Conditions in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences, 2024, 19, 388–410. [Google Scholar]

- Almatar, K. M. Towards sustainable green mobility in the future of Saudi Arabia cities: Implication for reducing carbon emissions and increasing renewable energy capacity. Heliyon, 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlNujaidi, K. , Alhabib, G., & AlOdhieb, A. Spot-the-camel: Computer vision for safer roads. arXiv preprint arXiv, 2023, 2304.00757.

- World Health Organization. Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021–2030, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/global-plan-for-the-decade-of-action-for-road-safety-2021-2030. (Accessed on 4 April 2025).

- World Bank. Road Safety and Sustainable Mobility: Policy Integration in Developing Economies, 2022. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099645006172219760/pdf/P1731880a0ad070ff0a6cf01b424e24ed04.pdf. (Accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Mohammed, A. E. A. A. , & Saad, S. A. A. The Impact of the Transport and communications sector on Saudi Economic growth Using ARDL Model. International Journal of Latest Engineering Research and Applications, 2023, 08, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M. , Alawadh, A., Rafi, N., & Akhtar, S.. Analyzing the Impact of Vision 2030’s Economic Reforms on Saudi Arabia’s Consumer Price Index. Sustainability, 2024, 16, 9163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Road Assessment Programme (iRAP). Saudi Arabia's Roads General Authority Recognised as a Shining Star in Coveted International Gary Liddle Memorial Award Program, 2025. Saudi Arabia’s Roads General Authority recognised as a Shining Star in coveted international Gary Liddle Memorial Award Program - iRAP. (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Reducing Road Crash Deaths in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2023.https://www.who.int/news/item/20-06-2023-reducing-road-crash-deaths-in-the-kingdom-of-saudi-arabia. (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Alotaibi, A. , Almasoudi, A., & Alqurashi, A. Investigation of the impact of smart mobility solutions on urban transportation efficiency in Saudi Arabian Cities. Journal of Umm Al-Qura University for Engineering and Architecture, 2025; 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tit, A. A. , Ben Dhaou, I., Albejaidi, F. M., & Alshitawi, M. S. Traffic safety factors in the Qassim region of Saudi Arabia. Sage open, 2020, 10, 2158244020919500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnujaidi, K. , & AlHabib, G. Computer vision for a camel-vehicle collision mitigation system. arXiv preprint arXiv, 2023, 2301.09339. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).