1. Introduction

Future protected plant production should be energy- and water-saving as well deliver safe, healthy, and functional food. Tomato is one of the most important vegetable crops grown in glasshouses and polyethylene plastic tunnels. Tomato fruits play an important role in human diet worldwide as a source of, among others, antioxidant biomolecules like lycopene, ascorbic acid, phenolics, flavonoids, and vitamin E [

1,

2,

3,

4]. As with other vegetables, tomato production under cover on a big scale near huge metropolises more and more frequently encounters the problem of fresh water shortage and its resultant high price in many regions of the world. Therefore, research into improving irrigation water use efficiency for glasshouse tomato production is urgently needed.

Strategies improving water use efficiency (WUE) of plants which are most often investigated nowadays include common (regulated) deficit irrigation (DI) and alternating deficit irrigation causing partial root-zone drying (PRD) [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. PRD and DI represent two irrigation strategies which differ in soil water dynamics, PRD being more dynamic than DI due to the smaller soil volume to which irrigation is applied as compared to DI. Under DI reduction in nutrient transport to root surfaces may be induced due to periods of low soil water content for the whole root zone. Under PRD the radial flow rate of nitrate to root surfaces may be enhanced by higher local soil water content, a result of extended wetting/drying processes under PRD. The impact of both deficit irrigation strategies on plant physiology, WUE, and yield of tomato has lately been intensively investigated [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. There are also some reports about increased tomato fruit quality in terms of dry matter content, sugar content, skin colour, and total soluble solid content under deficit irrigation, especially in processing tomatoes [

11,

17,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Increase of antioxidant content in field-grown cultivars of potatoes [

24,

25] and in tomatoes [

26,

27,

28] under drought stress or deficit irrigation has been discovered; in the latter case there was also an increase in the content of carotenoids, vitamin C, and phenolics. Deficit irrigation may be regarded as a regulated way of imposing slight soil water stress by withholding irrigation water. Thus it has the potential to increase the amount of tissue secondary metabolites including antioxidant content [

29,

30]. However, until now no information was available on how different deficit irrigation treatments affect antioxidant content in tomato fruits. In addition, the most detailed investigations about the effects of DI and PRD on tomato have only been undertaken for a period of a few weeks during the growing season – it is therefore difficult to draw conclusions about the long-term effects of those irrigation treatments on the crop. To complement the aforementioned research, the objective of the present study was to determine the effects of long-term DI and PRD treatments under glasshouse conditions on yield and quality of fresh tomato fruits with special emphasis on their antioxidant content as an important property of these fruits for human diet. Additionally, the study aimed at a comparison of these two different deficit irrigations with respect to the benefits of their implementation in crop production.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

The experiments were performed on tomato plants (

Solanum lycopersicum L., cv.

Cedrico) in a glasshouse during two growth seasons in Cracow, Poland. The seeds were obtained from J.H. Planter Aps, Ingersvej 4, 2640 Hedehusene, Denmark.

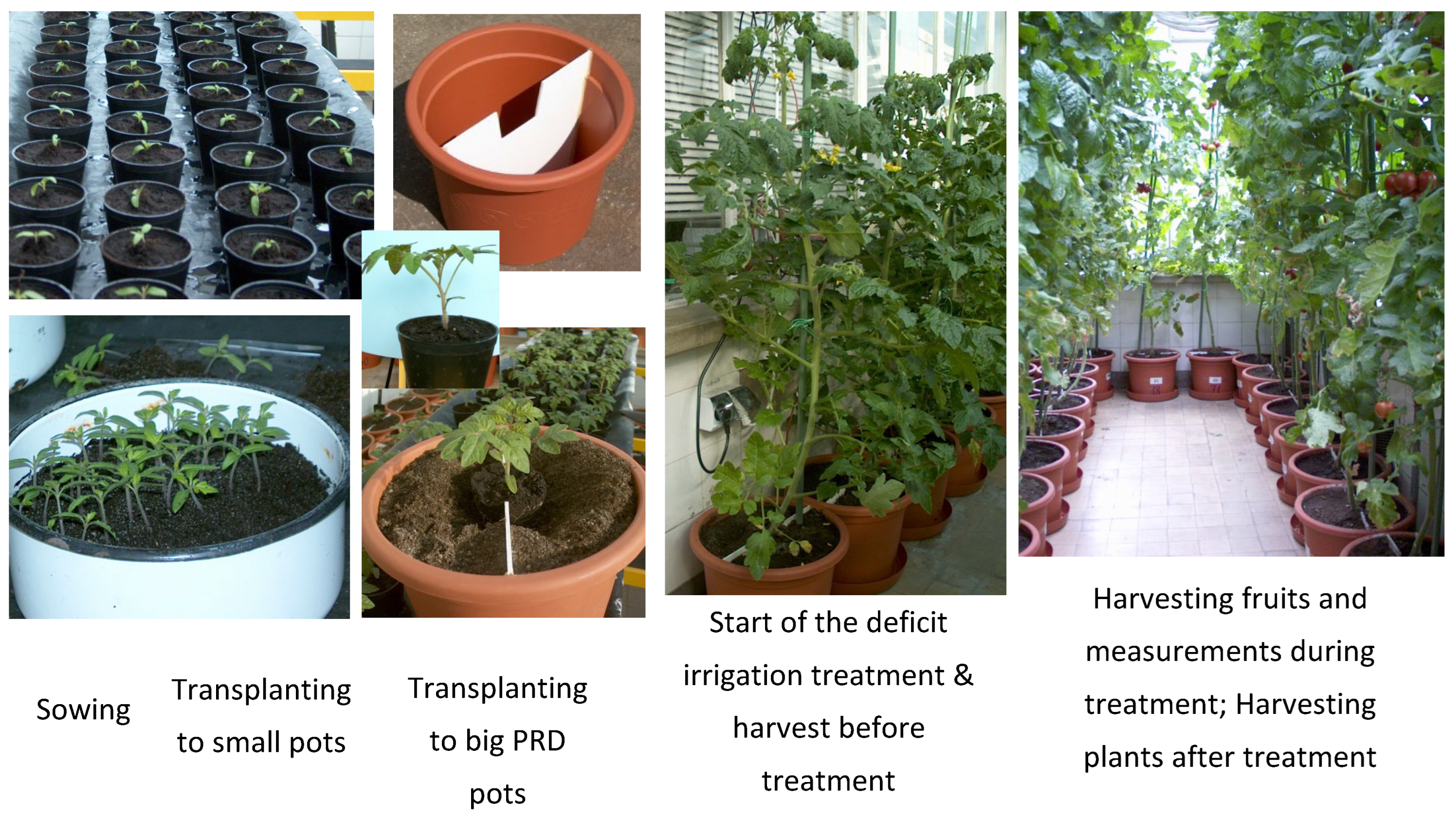

Cedrico is a hybrid cultivar of fresh tomato with an undeterminate growth habit. The seeds were sown into containers filled with peat substrate and then germinated in a growth chamber at 25°C and at light intensity of 250 μmol m

-2 s

-1, photoperiod 15h (

Scheme 1). After 14 days the seedlings were planted into small pots filled with the starting soil for tomato seedlings, and then the plants were grown in a glasshouse at 26/20°C day/night. After two weeks the seedlings were replanted into special 12 L split-root pots (

Scheme 1) filled with a mixture of peat substrate, clay soil and sand (4:1:1 v/v/v). The split-root pots were vertically divided into two equal halves with a PVC plate and the partition was water sealed with a gap filling adhesive to prevent water movement between the two halves. In the middle of the upper part of the partition plate, a piece of PVC was removed, which made it possible to plant the seedling to a depth of 7 cm. While transplanting, the root system of the seedling was distributed equally to both parts of the pot so that further root growth of each plant proceeded into both parts of the pot (

Scheme 1). This split-root pot, separating the root system into two halves, made it possible to maintain different water conditions in each half during PRD treatment. After being transplanted into the split-root pots, the plants grew in a glasshouse with a regulated temperature ranging from 22 to 30°C (day, 16h) and from 15 to 20°C (night). Air humidity was monitored only and it changed following the natural fluctuation. During heavily clouded days the plants were illuminated by lamps (Philips P83 SON-T AGRO 400) with light intensity of ca. 300 μmol m

-2 s

-1 on the top of the canopy. The plants were fertilized every two weeks with fertilizer Agrecol (20 g per pot) designed for tomato plants (

www.agrecol.pl). During the experimental period, all side shoots were removed. The stem growth apex was removed after the appearance of one leaf above the 5th flower cluster.

2.2. Irrigation Treatments

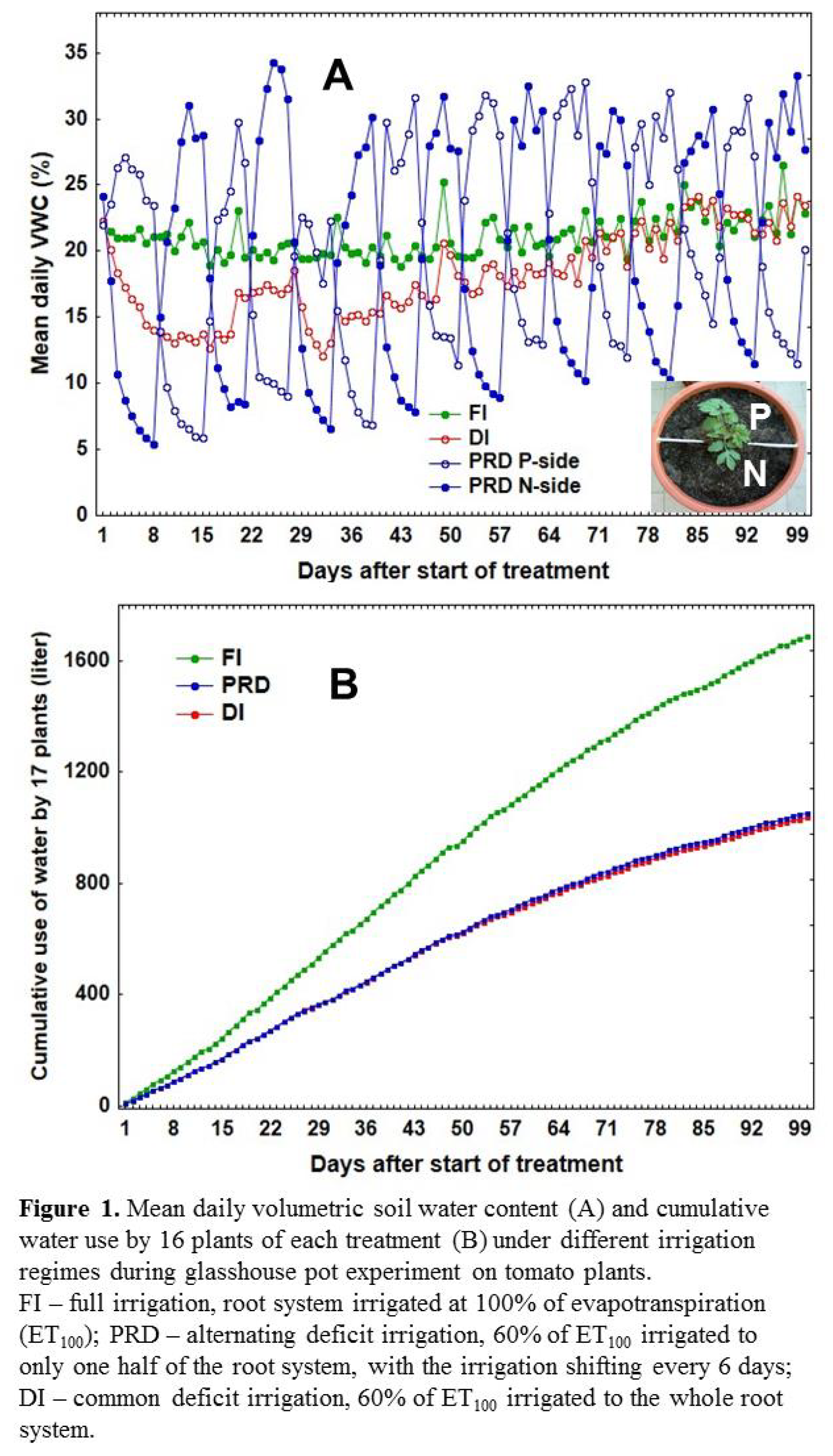

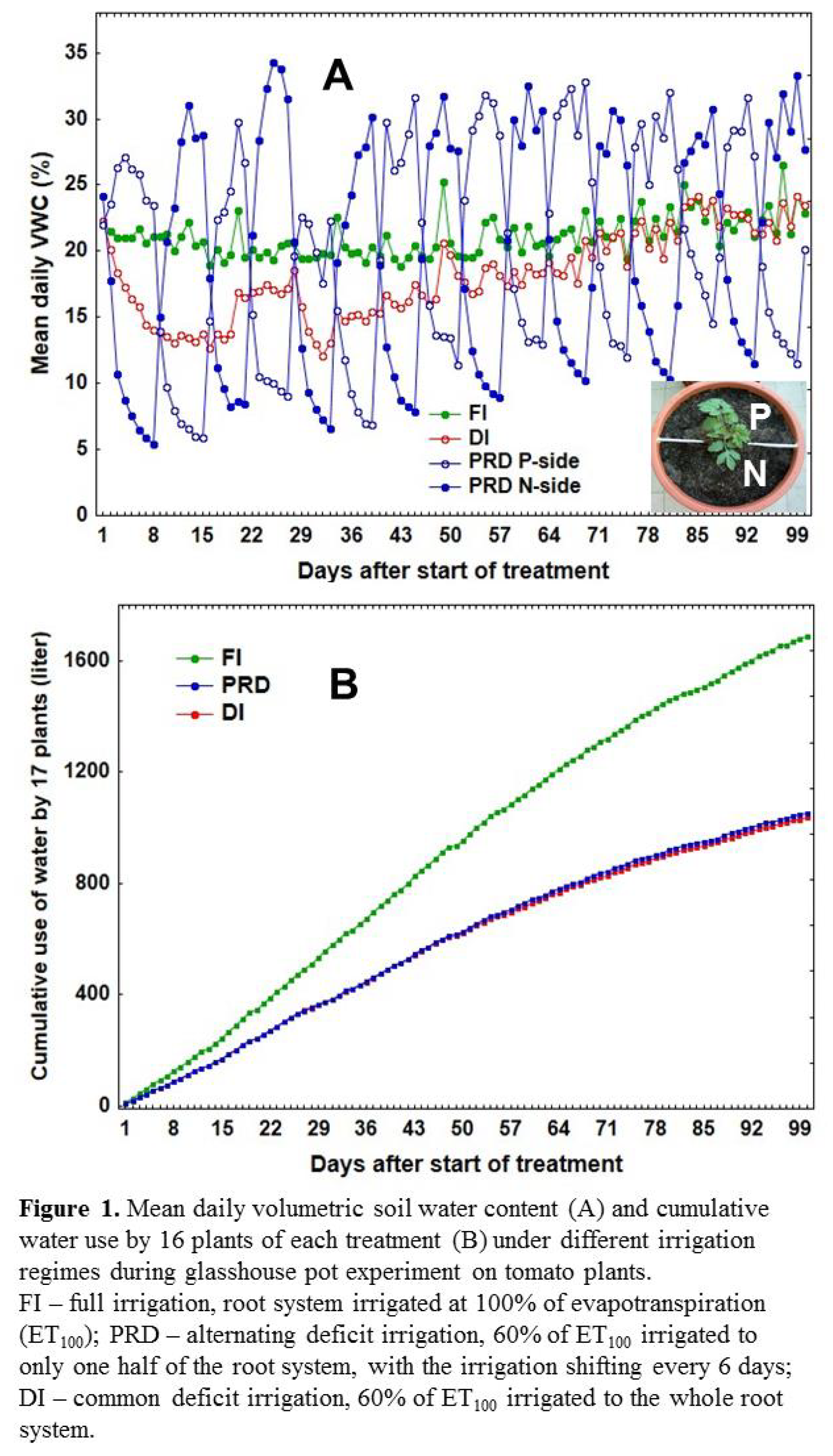

Until the appearance of fruits on the first cluster and flowering on the second and third clusters, all plants were watered to 25% of volumetric water content (θ), which equalled ca. 80% of water holding capacity (WHC) of the soil mixture used. The limit of 80% of WHC was chosen to avoid flooding roots in the pots. Next the plants were subjected to three irrigation treatments: full irrigation (FI), in which the whole root system was irrigated daily to 25% of θ; alternating deficit irrigation, causing partial root-zone drying (PRD), in which 50% (Experiment 1) or 60% (Experiment 2) of the irrigation water used in FI was applied to one half of the root system, and the irrigation was shifted every 6 days when θ of the drying side decreased to about 6%; and common deficit irrigation (DI), in which 50% (Experiment 1) or 60% (Experiment 2) of the irrigation water used in FI was applied to the whole root system. During the whole treatment period, there were 7 and 16 PRD cycles in experiment 1 and 2, respectively. For each treatment 16 plants in four blocks were used. θ of both halves of all pots was measured every day before irrigation by TDR system and mean daily θ (Figure 1A) for all treatments was calculated based on θ of present and previous day as well as the amount of water added to individual pots or pot halves. Then the plants were irrigated manually based on daily measurements of θ in both pot halves of FI plants and the calculation of their mean daily water loss. Control plants were irrigated to obtain 80% of WHC (θ WHC = 30%) of the pot soil, i.e.

, θ control plants was set in calculations to 24%. The deficit irrigated plants received 50% (Experiment 1) or 60% (Experiment 2) of the mean daily water loss of control plants, which was added to only one pot half (PRD) or spread equally to both pot halves (DI).

2.3. Measurement of Soil Water Content

Volumetric water content (θ) was measured daily in the middle of both halves of all pots by manual Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR) system CS620 HydroSense

®® Water Content Sensor with CD620 HydroSense Display Unit (

http://www.campbellsci.com/cs620). The measurements were performed for the whole profile of the soil in pots by means of 20 cm rods. The CS620 HydroSense system was calibrated by the manufacturer for typical agricultural soils by the adoption of appropriate calibration coefficient transforming probe outgoing signals to volumetric water content values (Instruction manual, HydroSense, Campbell Scientific, Inc.,

http://www.campbellsci.com/cs620). The time course of θ is presented in Figure 1A as daily mean θ for pots of FI and DI or for halves of pots of PRD, where every point was calculated as a treatment mean of θ from the previous day after watering (e.g.

, FI 24%) and the measured θ of the current day. To check the reliability of CS620 HydroSense readings obtained for soil mixture used in our experiments, additional tests were performed, in which water content was measured simultaneously by CS620 HydroSense and by gravimetric methods. The correlation coefficient between θ values obtained by CS620 HydroSense and water content obtained by weighting and drying was high, statistically significant (at p ≤ 0.05) and amounted to 0.80. Thus, the θ determined by CS620 HydroSense for the soil mixture was reliable.

2.4. Harvest of Fruits and Sampling for Quality Determination

In order to determine yield, fruits were harvested from the first three (Experiment 1) or five (Experiment 2) clusters of all 16 plants for each treatment. The harvests took place every three days during the ripening time beginning from the 36th day after the start of the treatment. The fruits were plucked at the stage of full maturity and their fresh weight was individually determined. Afterwards, the fruits were dried for 7 days at 60°C and weighted again to determine their dry weight (DW). Samples of fruit sap were taken from three similarly sized fruits of each tomato plant representative for the 1st, 2nd and 3rd cluster (Experiment 1) as well as for 2nd, 3rd and 4th cluster (Experiment 2). After squeezing out, the sap was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored in deep freezer at -40°C until measurements. Similarly, three entire fruits per plant were frozen in deep freezer for quality determination.

2.5. Determination of Plant Growth Parameters

The area, fresh weight (FW) and DW (after 3 days at 60°C) of ten top leaves as well as FW and DW of stems of 5 plants for each treatment were determined. The leaf area was measured by an area scanner connected with a computer equipped with the software for plant leaf area determination (Delta-T SCAN ver. 2.04nc, Delta-T Devices Ltd.).

2.6. Determination of Fruit Quality

The quality of fruits was evaluated on the basis of (A) total content of antioxidants (total antioxidant activity) in fresh fruit sap as well as in dry matter of the fruits; (B) content of reducing sugars in fruits; (C) titratable acidity, osmolarity and pH value of fruit sap. The samples of fruit sap after thawing were centrifuged for 20 min at 18,000 g in a cooled (4°C) centrifuge (MPW-350R, Poland) and the supernatants were used for measurements of total antioxidants, titratable acidity, osmolarity and pH value. Whole fruits were used for measurements of total content of antioxidants in freeze-dried matter (DM) and of reducing sugars in fresh matter. For measurements of total antioxidant content in dry matter of the fruits, 50 mg of DM of each fruit were extracted for 3 hours in the dark at room temperature on a shaker (Yellow Line Basic 5.0, 480 cycles/min) in 1.5 mL Eppendorf vials with 1 mL of 50% ethanol. Next the samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 18,000 g in a centrifuge (MPW-350R, Poland) and the supernatants were used for determination of total antioxidants.

2.6.1. Determination of Total Antioxidant Content in Sap and in Dry Matter Of Fruits

The total content of antioxidants (total antioxidant activity) in fresh fruit sap as well as in the extracts from dry matter of the fruits was measured by DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) method according to Brand-Williams, et al. [

31] with some modifications [

32]. The DPPH protocol was adapted to 96-well microtitre plates and to the measurement of absorbance by ELISA reader [

33]. A 0.5 mM solution of DPPH in methanol was used. Into wells of microtitre plate (flat polystyrene 96-microtitre plates, Equimed, Poland) first aliquots of 16,5 µL of fruit sap or AA standards (40 µL of 3, 2.5, 2, 1.75, 1.5, 1.25, 1 and 0.75 mM L-ascorbic acid (AA, SIGMA) or 20-33 µL of 50% ethanol extracts of DM and next 250 µL 0.5 mM DPPH were pipetted. 0.5 mM solution of DPPH in methanol was also pipetted to determine the initial absorbance of the DPPH solution. Each sample was pipetted into three wells. The plate was then covered by a lid and put into the thermostat DTS-2 (Biokom, USA) for incubation at 37°C for 30 min. The absorbance of each well was determined at 490 nm using ELISA reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Model 680). The results were expressed as mg of AA equivalents per 1 kg DM or 1 L fruit sap, i.e.

, the quantity of AA required to produce the same scavenging activity as that in the extract of 1 kg of DM or 1 L of fruit sap. All measurements were performed three times.

2.6.2. Determination of Reducing Sugar Content In Fruits

For measurement of reducing sugar content (RS), 10 g of homogenised pulp were used for each fruit. Then after 50 ml of water were added and the mixture was boiled for 3 min, RS was measured colorimetrically according to the Samogyi-Nelson method [

34,

35] and the norms PN-90/75101/07 for sugar measurements in plant products. Absorbance of samples and glucose standards were measured by spectral colorimeter (Specol, Carl Zeiss Jena, Germany) at 500 nm.

2.6.3. Determination of Titratable Acidity, Osmolarity and pH Value of Fruit Sap

The total titratable acidity was measured by the titration of 0.5 mL fruit sap with 0.1 N NaOH after adding the indicator phenolphthalein and the results were expressed as milliequivalents of alkali per 1L of sap [

36]. The pH value of fruit sap was measured by pH-meter pH 211 using a microelectrode HANHI1330B (Hanna Instruments, Germany). The osmolarity of fruit sap was measured by osmometer Marcel os3000 (Marcel, Poland).

2.7. Statistical Analyses

Both experiments were arranged in a randomized complete block design. For each treatment 16 plants divided into four blocks were used. Both experiments gave similar results, especially regarding fruit quality. Although both experiments had similar design, they could not be calculated as a two-year series of experiments because of the different treatment parameters. Thus, in this paper, mainly the data from experiment 2 is presented as representative for the whole research. Only the yield and content of antioxidants in sap and DM of fruits from both experiments are presented. The values presented in the figures for the treatments are mean values of at least 16 measurements of eight samples collected from different plants. Analyses of variance and comparisons of the treatments according to Tukey’s test were performed by data analysis software system STATISTICA 12, StatSoft, Inc.,

www.statsoft.com.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Water Content During Different Irrigation Treatments

Fully irrigated plants (FI) were watered at 100% of evapotranspiration (ET100) to 24% of volumetric water content (θ). Therefore, the mean daily θ of FI ranged between 20 and 25% during the whole treatment period (Figure 1A). In alternating deficit irrigation causing partial root-zone drying (PRD) 60% of ET100 was irrigated to only one half of the root system and the irrigation was shifted every 6 days. Cycles of watering and drying periods caused enormous fluctuations in mean daily θ of both (P and N) halves of the pot ranging from 6 to 34%. Thus in the middle of each cycle the roots of PRD-treated plants were exposed simultaneously to soil drought on one side of the pot and to ample irrigation on the other side. In common deficit irrigation (DI) 60% of ET100 was irrigated to the whole root system. The mean daily θ ranged between 12 and 20% during the first seventy days of the treatment. However, during further treatment, they were close to the values of FI in spite of the reduced irrigation volume (Figure 1A). Such effect was not observed during the shorter (42 days) DI treatment in the Experiment 1 (data not shown).

3.2. Characteristics of Tomato Plants Under Different Irrigation Treatments

The tomato cultivar

Cedrico used in the experiments has an undeterminate growth habit so the stem growth apex of all plants was cut after the appearance of one leaf above the 5th cluster. At the end of the treatment, the ten upper leaves of FI plants had a bigger area and significantly higher dry weight than those of PRD and DI plants (

Table 1). The total water use for FI at the end of the treatment amounted to about 40% more than that for PRD and DI (Table 1, Figure 1B), and PRD plants had the highest water use efficiency, significantly exceeding that of FI and DI (Table 1).

3.3. Quality of Tomato Fruits Under Different Irrigation Treatments

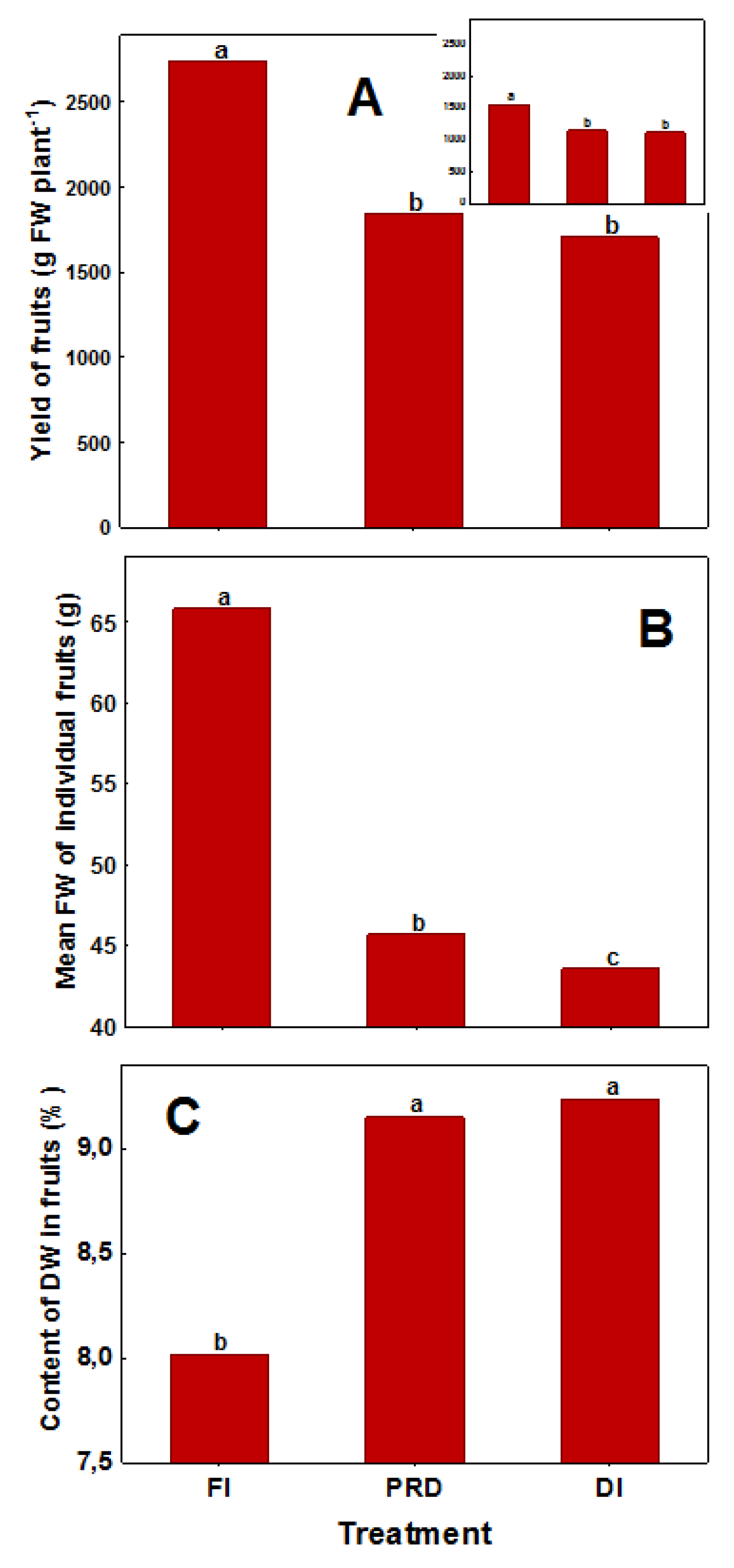

The yield of fruits in FI was about 30% higher in comparison to PRD and DI (

Figure 2A), while the yield in PRD was 5% higher compared to DI though the difference was not statistically significant. A similar reduction of 26% in fruit yield in PRD and DI as compared to FI was observed during an experiment with deficit irrigation at the level of 50% of ET

100 (

Figure 2A Inset). Similarly, the mean fresh weight of individual fruits was significantly higher in FI in comparison to PRD and DI (

Figure 2B). However, the fruits in FI had significantly lower DW content than those in PRD and DI, and the difference exceeded one per cent, which constitutes above 12% of the whole DW (

Figure 2C

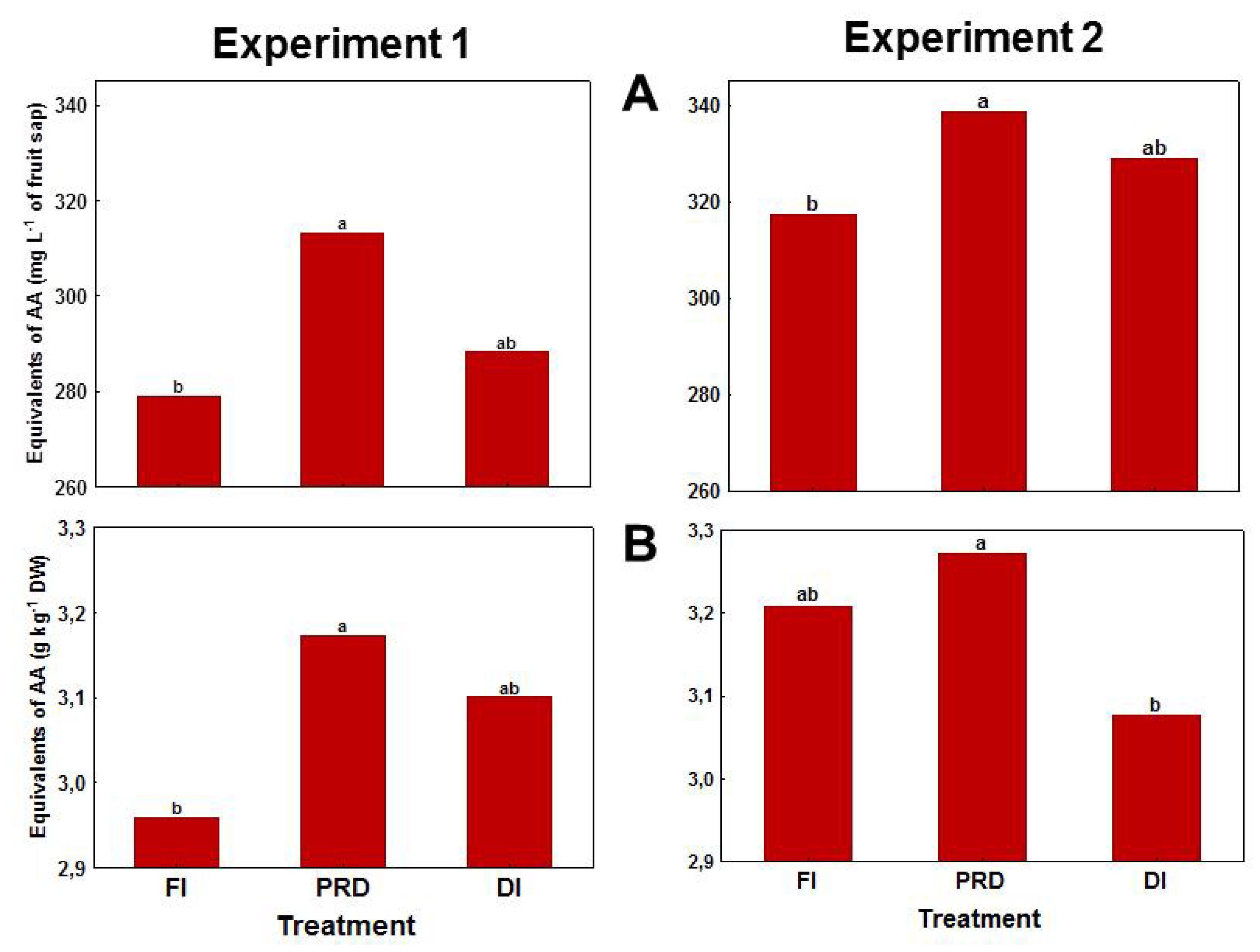

PRD plants had significantly higher content of antioxidants in fresh fruit sap (

Figure 3A) as well as in dry matter of the fruits (

Figure 3B) in comparison to FI plants in both experiments performed. In experiment 2 the differences amounted to 7% and 2%, respectively. Interestingly, DI plants in this experiment had higher content of antioxidants in fresh fruit sap (

Figure 3A) but lower in dry matter of the fruits (

Figure 3B) in comparison to FI plants. However, the differences were not statistically significant.

FI – full irrigation, root system irrigated at 100% of evapotranspiration (ET100); PRD – alternating deficit irrigation, 60% of ET100 irrigated to only one half of the root system, with the irrigation shifting every 6 days; DI – common deficit irrigation, 60% of ET100 irrigated to the whole root system.

Means which do not have letters in common are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 according to Tukey’s test.

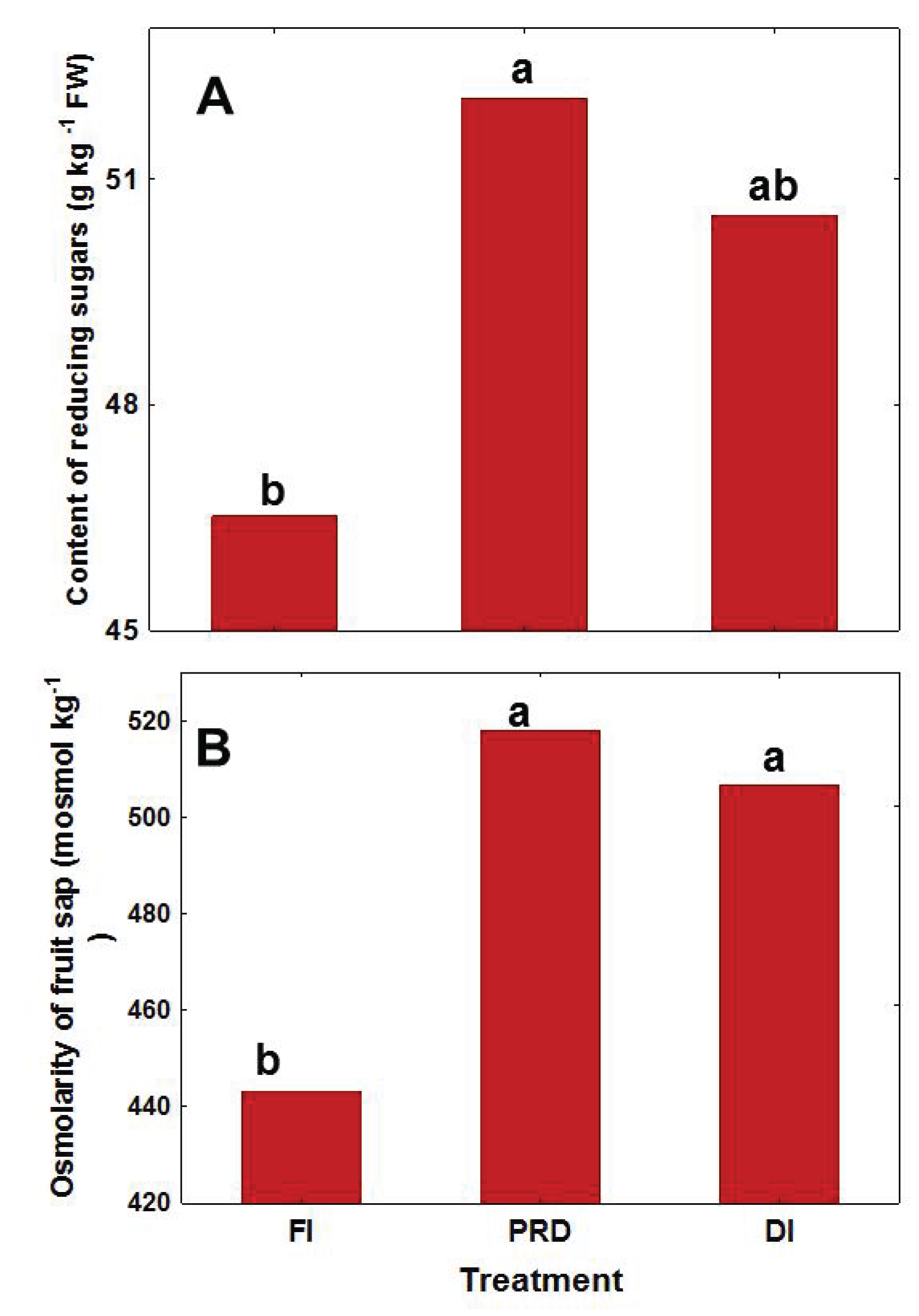

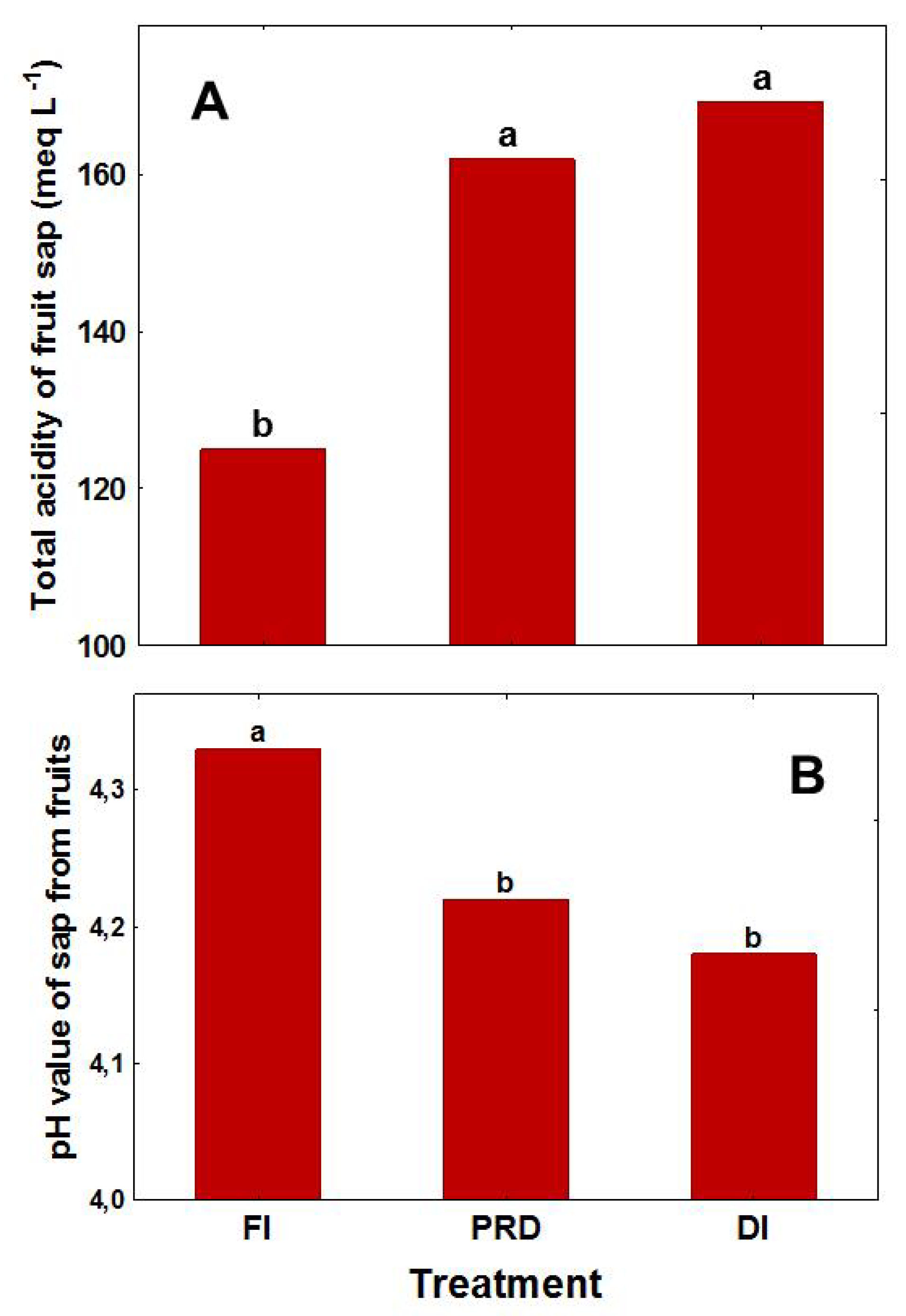

Both PRD and DI caused an increase in the content of reducing sugars in fruits in comparison to FI (

Figure 4A). This rise was particularly marked in PRD and amounted to 12%. Parallel to the increased content of reducing sugars in fruits, a significant rise in osmolarity was observed in fruit sap in both PRD and DI, by 17 and 14%, respectively, as compared to FI plants (

Figure 4B). Similarly, the total titratable acidity of fresh fruit sap increased significantly in both DI and PRD in comparison to FI (Figure. 5A). The increase in acidity of sap was immense in both deficit irrigation treatments and amounted to above 30%. Parallel to the increase in acidity there was a significant decrease in pH value of fruit sap in both PRD and DI treatments in comparison to FI (

Figure 5B).

FI – full irrigation, root system irrigated at 100% of evapotranspiration (ET100); PRD – alternating deficit irrigation, 50% (Experiment 1) or 60% (Experiment 2) of ET100 irrigated to only one half of the root system, with the irrigation shifting every 6 days; DI – common deficit irrigation, 50% (Experiment 1) or 60% (Experiment 2) of ET100 irrigated to the whole root system.

Means which do not have letters in common are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 according to Tukey’s test.

FI – full irrigation, root system irrigated at 100% of evapotranspiration (ET100); PRD – alternating deficit irrigation, 60% of ET100 irrigated to only one half of the root system, with the irrigation shifting every 6 days; DI – common deficit irrigation, 60% of ET100 irrigated to the whole root system.

Means which do not have letters in common are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05

FI – full irrigation, root system irrigated at 100% of evapotranspiration (ET100); PRD – alternating deficit irrigation, 60% of ET100 irrigated to only one half of the root system, with the irrigation shifting every 6 days; DI – common deficit irrigation, 60% of ET100 irrigated to the whole root system.

Means which do not have letters in common are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 according to Tukey’s test.

4. Discussion

4.1. Plants Growth and Water Use Efficiency

According to the literature, there is almost no doubt that all kinds of deficit irrigation inhibit vegetative growth of plants [

5,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Also in our experiments both PRD and DI decreased the size of tomato plants by reducing their leaf area and DW by 32 and 33% (PRD) and 24 and 27% (DI), respectively, as compared to FI (

Table 1). Very similar reductions by about 30% of the total tomato plant dry mass for both types of deficit (50%) irrigations compared with the control were reported by Tahi et al. (2007). In turn, Campos et al. (2009) observed that three different levels of PRD reduced the size of tomato shoots proportionally to the amount of available water during different PRD treatments. Conversely, the effect of different modes of deficit irrigation on the yield of tomato fruits has not been unequivocally elucidated up to now. Several studies found no significant yield reductions under PRD or DI conditions [

11,

21] but other reports showed significant decrease of yield in comparison to FI plants [

41,

42]. In the current study, PRD and DI treatments, in which there was a significant decrease in fresh fruit yield, saved 40% of irrigation water in comparison to FI (Figure 1B, 2A). The yield reduction was slightly smaller in PRD than in DI. The yield reduction in PRD and DI plants was due mainly to the decreased size of tomato fruits (

Figure 2B). However, the fruits in PRD and DI had significantly higher dry matter content, exceeding that of FI fruits by ca. 1.2% (

Figure 2C). WUE was increased by about 9% in PRD and 1% in DI plants compared to FI plants. Thus, PRD irrigation may be a promising technique for saving water especially in the regions where fresh water is highly expensive.

4.2. Quality of Tomato Fruits and Level of Antioxidants

The quality of fruits plays a crucial role in the production of fresh and processing tomatoes because of the important function of tomato fruits in human diet as a source of bioactive molecules like lycopene, ascorbic acid, phenolics, flavonoids and vitamin E [

1,

2,

3]. So apart from yield and production costs, the most important factor for future tomato production to be considered is the quality and the content of these bioactive plant molecules. It is of great interest that in the present study almost all investigated parameters of fruits’ quality were higher in PRD and DI than in FI. The total content of antioxidants in fruit sap in PRD plants was significantly higher than in FI plants (

Figure 3A), and the same was observed in dry matter of fruits, although the difference was not statistically significant (

Figure 3B). Antioxidants are thought to be important in the prevention of some diseases such as cancer and cardiovascular disease. Their content in tomato fruits depends on genetic and environmental factors as well as on the agricultural techniques used [

26,

43,

44,

45]. The presented results show clearly and for the first time that deficit irrigations, especially alternating deficit irrigation causing PRD, significantly increase the level of total activity of antioxidants in fresh tomato fruits in comparison to FI. Earlier studies have shown that decrease in soil water availability caused an increase in the content of the main antioxidants in tomato fruits such as carotenoids (lycopene), vitamin C and phenolics [

20,

26,

40,

42,

46,

47,

48]. In our experiments common deficit irrigation (DI) increased the level of antioxidants in fruit sap compared to FI but the increase was not significant, while in DM of fruits the content of antioxidants increased slightly in experiment 1 and even decreased in experiment 2 (

Figure 3). The bio-physiological mechanisms underlying the significantly higher level of antioxidants in fruits in PRD and partly in DI than in FI remain unknown and merit further investigation. One explanation for this phenomenon in PRD might be that it is an adaptation mechanism to alternating stress conditions of the root system, namely deep water shortage of one side of the root system and relatively good water availability of the other side. These conditions may have amplified secondary metabolism and caused the accumulation of secondary metabolites, mainly of phenolics, which have antioxidant properties. The differences between PRD and DI are seemingly connected to the higher soil water dynamics under PRD compared to DI and may result in both altered root ABA production and nutrient uptake under similar level of water saving [

39,

49]. In the literature there are some reports about the increase of antioxidant activity under PRD conditions in strawberry [

50], potato [

25] and grape [

51]. In the latter case the increase in antioxidant activity in response to PRD treatment was associated with an increase in anthocyanin and phenolic concentration.

Other characteristics of internal quality of fresh tomato fruits such as content of reducing sugars (

Figure 4A), total acidity (

Figure 5A), and dry matter content (

Figure 2A) were significantly higher in fruits in PRD than in FI. All these parameters are important for the taste and nutritive value of tomato fruits [

20,

36,

52]. A similar increase in some parameters of tomato fruit quality in DI or PRD compared to FI plants was observed by Zegbe-Dominguez et al. [

21] and Xu, et al. [

53] for processing tomato and by Campos et al. [

11] for salad-type tomato. In turn, the increase in osmolarity of fruit sap, observed under PRD and DI conditions in the present study (

Figure 4B), may contribute to tolerance against salinity stress, which often occurs during long-term tomato growth in pots or soilless systems [

54].

5. Conclusions

Long-term common (DI) and alternating (PRD) deficit irrigations of tomato plants saved 40% of irrigation water while reducing fruit yield but increasing WUE – by as much as 9% in the PRD treatment. PRD and DI increased dry matter content in fruits by 12% and their total acidity by 30% as compared to FI. PRD and DI also increased total content of antioxidants in fresh fruit sap by 7 and 4%, respectively, as compared to FI. Thus alternating and common deficit irrigations were proved to have evident advantages in tomato plants, improving WUE, fruit quality, and especially the content of antioxidants. The results obtained in this study clearly suggest that PRD and especially the technically cheaper DI may be used in future sustainable horticultural production not only to save water but also to manipulate concentrations of key bioactive and health-promoting compounds in vegetables and fruits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.W.; F.L.; C.R.J. and F.J.; methodology, B.W.; J.S.; F.L.; C.R.J.; and F.J.; software, B.W.; J.S. and F.J.; validation, B.W.; J.S. and F.J.; formal analysis, B.W.; J.S. and F.J.; investigation, B.W.; J.S.; M.T.G.; P.C.; M.T.; M.W. and F.J.; resources, B.W.; J.S.; M.T.G.; P.C.; M.T.; M.W. and F.J.; data curation, B.W.; J.S. and F.J.; writing—original draft preparation, B.W.; F.L.; C.R.J.; and F.J.; writing—review and editing, B.W.; M.T.G.; F.L.; C.R.J.; and F.J.; visualization, B.W.; F.L.; C.R.J.; and F.J.; supervision, F.L.; C.R.J.; and F.J.; project administration, F.L.; C.R.J.; and F.J.; funding acquisition, F.L.; C.R.J.; and F.J.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the EU project SAFIR, contract no 023168 (Food). The APC was funded from the institutional funding awarded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland to The Franciszek Górski Institute of Plant Physiology Polish Academy of Sciences.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Barbara Kaminska for her excellent technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

AA L-ascorbic acid

DI common deficit irrigation

DM freeze-dried matter

DPPH 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

DW dry weight

ET100 100% of evapotranspiration

FI fully irrigated plants

FW fresh weight

PRD alternating deficit irrigation causing partial root-zone drying

RS reducing sugar content

TDR Time Domain Reflectometry

WHC water holding capacity

WUE water use efficiency

θ volumetric water content

References

- Frusciante, L.; Carli, P.; Ercolano, M.R.; Pernice, R.; Di Matteo, A.; Fogliano, V.; Pellegrini, N. Antioxidant nutritional quality of tomato. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Romero, M.; Arraez-Roman, D.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernandez-Gutierrez, A. Analytical determination of antioxidants in tomato: Typical components of the Mediterranean diet. J. Sep. Sci. 2007, 30, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, C.; George, B.; Deepa, N.; Singh, B.; Kapoor, H.C. Antioxidant status of fresh and processed tomato - A review. J. Food Sci. Tech. Mys. 2004, 41, 479–486. [Google Scholar]

- Chabi, I.B.; Zannou, O.; Dedehou, E.; Ayegnon, B.P.; Odouaro, O.B.O.; Maqsood, S.; Galanakis, C.M.; Kayodé, A.P.P. Tomato pomace as a source of valuable functional ingredients for improving physicochemical and sensory properties and extending the shelf life of foods: A review. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.M.; Ortuno, M.F.; Chaves, M.M. Deficit irrigation as a strategy to save water: Physiology and potential application to horticulture. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2007, 49, 1421–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C.R.; Battilani, A.; Plauborg, F.; Psarras, G.; Chartzoulakis, K.; Janowiak, F.; Stikic, R.; Jovanovic, Z.; Li, G.T.; Qi, X.B. ; Stikic, R.; Jovanovic, Z.; Li, G.T.; Qi, X.B., et al. Deficit irrigation based on drought tolerance and root signalling in potatoes and tomatoes. Agric. Water Manage. 2010, 98, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.Z.; Zhang, J.H. Controlled alternate partial root-zone irrigation: its physiological consequences and impact on water use efficiency. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 2437–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katerji, N.; Mastrorilli, M.; Rana, G. Water use efficiency of crops cultivated in the Mediterranean region: Review and analysis. Eur. J. Agron. 2008, 28, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somefun, O.T.; Masasi, B.; Adelabu, A.O. Irrigation and Water Management of Tomatoes–A Review. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture and Environment 2024, 3, e70020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, J.B.; Hewa, G.; Hassanli, A.; Myers, B. Deficit Irrigation on Tomato Production in a Greenhouse Environment: A Review. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering 2021, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, H.; Trejo, C.; Pena-Valdivia, C.B.; Ramirez-Ayala, C.; Sanchez-Garcia, P. Effect of partial rootzone drying on growth, gas exchange, and yield of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Sci. Hortic. 2009, 120, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirda, C.; Cetin, M.; Dasgan, Y.; Topcu, S.; Kaman, H.; Ekici, B.; Derici, M.R.; Ozguven, A.I. Yield response of greenhouse grown tomato to partial root drying and conventional deficit irrigation. Agric. Water Manage. 2004, 69, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingo, D.M.; Theobald, J.C.; Bacon, M.A.; Davies, W.J.; Dodd, I.C. Biomass allocation in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) plants grown under partial rootzone drying: enhancement of root growth. Funct. Plant Biol. 2004, 31, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobeih, W.Y.; Dodd, I.C.; Bacon, M.A.; Grierson, D.; Davies, W.J. Long-distance signals regulating stomatal conductance and leaf growth in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) plants subjected to partial root-zone drying. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 2353–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahi, H.; Wahbi, S.; Wakrim, R.; Aganchich, B.; Serraj, R.; Centritto, M. Water relations, photosynthesis, growth and water-use efficiency in tomato plants subjected to partial rootzone drying and regulated deficit irrigation. Plant Biosystems 2007, 141, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Kang, S.; Du, T.; Li, F.; Qiu, R. Determination of comprehensive quality index for tomato and its response to different irrigation treatments. Agric. Water Manage. 2011, 98, 1228–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegbe, J.A.; Behboudian, M.H.; Clothier, B.E. Yield and fruit quality in processing tomato under partial rootzone drying. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2006, 71, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, T.T.; Feng, P.Y.; Yao, D.L.; Gao, F.; Hong, X. Effect of potassium fertilization during fruit development on tomato quality, potassium uptake, water and potassium use efficiency under deficit irrigation regime. Agricultural Water Management 2021, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.M.; Zuo, J.H.; Watkins, C.B.; Wang, Q.; Liang, H.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Liu, M.C.; Ji, Y.H. Sugar accumulation and fruit quality of tomatoes under water deficit irrigation. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2023, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patane, C.; Cosentino, S.L. Effects of soil water deficit on yield and quality of processing tomato under a Mediterranean climate. Agric. Water Manage. 2010, 97, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegbe-Dominguez, J.A.; Behboudian, M.H.; Lang, A.; Clothier, B.E. Deficit irrigation and partial rootzone drying maintain fruit dry mass and enhance fruit quality in ‘Petopride’ processing tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Sci. Hortic. 2003, 98, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyago-Cruz, E.; Corell, M.; Moriana, A.; Hernanz, D.; Stinco, C.M.; Mapelli-Brahm, P.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J. Effect of regulated deficit irrigation on commercial quality parameters, carotenoids, phenolics and sugars of the black cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) ‘Sunchocola’. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2022, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burato, A.; Fusco, G.M.; Pentangelo, A.; Ronga, D.; Carillo, P.; Campi, P.; Parisi, M. Balancing yield, water productivity, and fruit quality of processing tomatoes through the combined use of biodegradable mulch film and regulated deficit irrigation. European Journal of Agronomy 2025, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, C.M.; Schafleitner, R.; Guignard, C.; Oufir, M.; Aliaga, C.A.A.; Nomberto, G.; Hoffmann, L.; Hausman, J.F.; Evers, D.; Larondelle, Y. Modification of the health-promoting value of potato tubers field grown under drought stress: emphasis on dietary antioxidant and glycoalkaloid contents in five native Andean cultivars (Solanum tuberosum L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, Z.; Stikic, R.; Vucelic-Radovic, B.; Paukovic, M.; Brocic, Z.; Matovic, G.; Rovcanin, S.; Mojevic, M. Partial root-zone drying increases WUE, N and antioxidant content in field potatoes. Eur. J. Agron. 2010, 33, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, Y.; Dadomo, M.; Di Lucca, G.; Grolier, P. Effects of environmental factors and agricultural techniques on antioxidant content of tomatoes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2003, 83, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünyayar, S.; Keleş, Y.; Çekiç, F.Ö. The antioxidative response of two tomato species with different drought tolerances as a result of drought and cadmium stress combinations. Plant Soil Environ. 2005, 51, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipan, L.; Issa-Issa, H.; Moriana, A.; Zurita, N.M.; Galindo, A.; Martín-Palomo, M.J.; Andreu, L.; Carbonell-Barrachina, A.A.; Hernández, F.; Corell, M. Scheduling Regulated Deficit Irrigation with Leaf Water Potential of Cherry Tomato in Greenhouse and its Effect on Fruit Quality. Agriculture-Basel 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.M.; Oliveira, M.M. Mechanisms underlying plant resilience to water deficits: prospects for water-saving agriculture. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 2365–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breniere, T.; Fanciullino, A.L.; Dumont, D.; Le Bourvellec, C.; Riva, C.; Borel, P.; Landrier, J.F.; Bertin, N. Effect of long-term deficit irrigation on tomato and goji berry quality: from fruit composition to in vitro bioaccessibility of carotenoids. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free-radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. Food Science and Technology-Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft & Technologie 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Laskoś, K.; Pisulewska, E.; Waligórski, P.; Janowiak, F.; Janeczko, A.; Sadura, I.; Polaszczyk, S.; Czyczyło-Mysza, I.M. Herbal additives substantially modify antioxidant properties and tocopherol content of cold-pressed oils. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, L.R.; Mazza, G. Assessing antioxidant and prooxidant activities of phenolic compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 3597–3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, N. A photometric adaptation of the Somogyi method for the determination of glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 1944, 153, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somogyi, M. A new reagent for the determination of sugars. J. Biol. Chem. 1945, 160, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Ruiz, V.; Sanchez-Mata, M.C.; Camara, M.; Torija, M.E.; Chaya, C.; Galiana-Balaguer, L.; Rosello, S.; Nuez, F. Internal quality characterization of fresh tomato fruits. Hortscience 2004, 39, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, W.J.; Bacon, M.A.; Thompson, D.S.; Sobeih, W.; Rodriguez, L.G. Regulation of leaf and fruit growth in plants growing in drying soil: exploitation of the plants’ chemical signalling system and hydraulic architecture to increase the efficiency of water use in agriculture. J. Exp. Bot. 2000, 51, 1617–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Savic, S.; Jensen, C.R.; Shahnazari, A.; Jacobsen, S.E.; Stikic, R.; Andersen, M.N. Water relations and yield of lysimeter-grown strawberries under limited irrigation. Sci. Hortic. 2007, 111, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urlic, B.; Runjic, M.; Mandusic, M.; Zanic, K.; Selak, G.V.; Mateskovic, A.; Dumicic, G. Partial Root-Zone Drying and Deficit Irrigation Effect on Growth, Yield, Water Use and Quality of Greenhouse Grown Grafted Tomato. Agronomy-Basel 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yan, S.C.; Fan, J.L.; Zhang, F.C.; Xiang, Y.Z.; Zheng, J.; Guo, J.J. Responses of growth, fruit yield, quality and water productivity of greenhouse tomato to deficit drip irrigation. Scientia Horticulturae 2021, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topcu, S.; Kirda, C.; Dasgan, Y.; Kaman, H.; Cetin, M.; Yazici, A.; Bacon, M.A. Yield response and N-fertiliser recovery of tomato grown under deficit irrigation. Eur. J. Agron. 2007, 26, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.L.; Zhao, Y.L.; Tong, L.; Wang, R.; Zhao, S. Quantitative Analysis of Tomato Yield and Comprehensive Fruit Quality in Response to Deficit Irrigation at Different Growth Stages. Hortscience 2019, 54, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B.; Kaur, C.; Khurdiya, D.S.; Kapoor, H.C. Antioxidants in tomato (Lycopersium esculentum) as a function of genotype. Food Chem. 2004, 84, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, P.M.; Yang, R.Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, J.T.; Ledesma, D.; Tsou, S.C.S.; Lee, T.C. Variation for antioxidant activity and antioxidants in tomato. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2004, 129, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, M.A.; Ruiz, J.M.; Hernandez, J.; Soriano, T.; Castilla, N.; Romero, L. Antioxidant content and ascorbate metabolism in cherry tomato exocarp in relation to temperature and solar radiation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 1545–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nangare, D.D.; Singh, Y.; Kumar, P.S.; Minhas, P.S. Growth, fruit yield and quality of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) as affected by deficit irrigation regulated on phenological basis. Agricultural Water Management 2016, 171, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyago-Cruz, E.; Corell, M.; Moriana, A.; Hernanz, D.; Benítez-Gonzálezb, A.M.; Stinco, C.M.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J. Antioxidants (carotenoids and phenolics) profile of cherry tomatoes as influenced by deficit irrigation, ripening and cluster. Food Chemistry 2018, 240, 870–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Vázquez, J.R.; Benavides-Mendoza, A.; Juárez-Maldonado, A.; Cabrera-De la Fuente, M.; Robledo-Olivo, A.; González-Morales, S. Effect of deficit irrigation on the accumulation of antioxidant compounds in tomato plants. Ecosistemas Y Recursos Agropecuarios 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Song, R.; Zhang, X.; Shahnazari, A.; Andersen, M.N.; Plauborg, F.; Jacobsen, S.-E.; Jensen, C.R. Measurement and modelling of ABA signalling in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) during partial root-zone drying. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2008, 63, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, I.C.; Taylor, J.M.; Else, M.A.; Atkinson, C.J.; Davies, W.J. Partial rootzone drying increases antioxidant activity in strawberries. In Acta Horticulturae 744, ISHS 2007, Proc. Ist IS on Hum. Health Effects of F&V, Desjardins, Y., Ed. 2007; pp. 295-302.

- Bindon, K.A.; Dry, P.R.; Loveys, B.R. The Interactive effect of pruning level and irrigation strategy on grape berry ripening and composition in Vitis vinifera L. cv. Shiraz. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2008, 29, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, H.; Diakou-Verdin, V.; Benard, C.; Reich, M.; Buret, M.; Bourgaud, F.; Poessel, J.L.; Caris-Veyrat, C.; Genard, M. How does tomato quality (sugar, acid, and nutritional quality) vary with ripening stage, temperature, and irradiance? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.L.; Qin, F.F.; Xu, Q.C.; Xu, R.Y.; Wang, T.Y.; Wang, R. Applications of xerophytophysiology in plant production: Sub-irrigation improves tomato fruit yield and quality. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2011, 9, 256–263. [Google Scholar]

- Bolarin, M.C.; Estan, M.T.; Caro, M.; Romero-Aranda, R.; Cuartero, J. Relationship between tomato fruit growth and fruit osmotic potential under salinity. Plant Sci. 2001, 160, 1153–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).