Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

01 August 2025

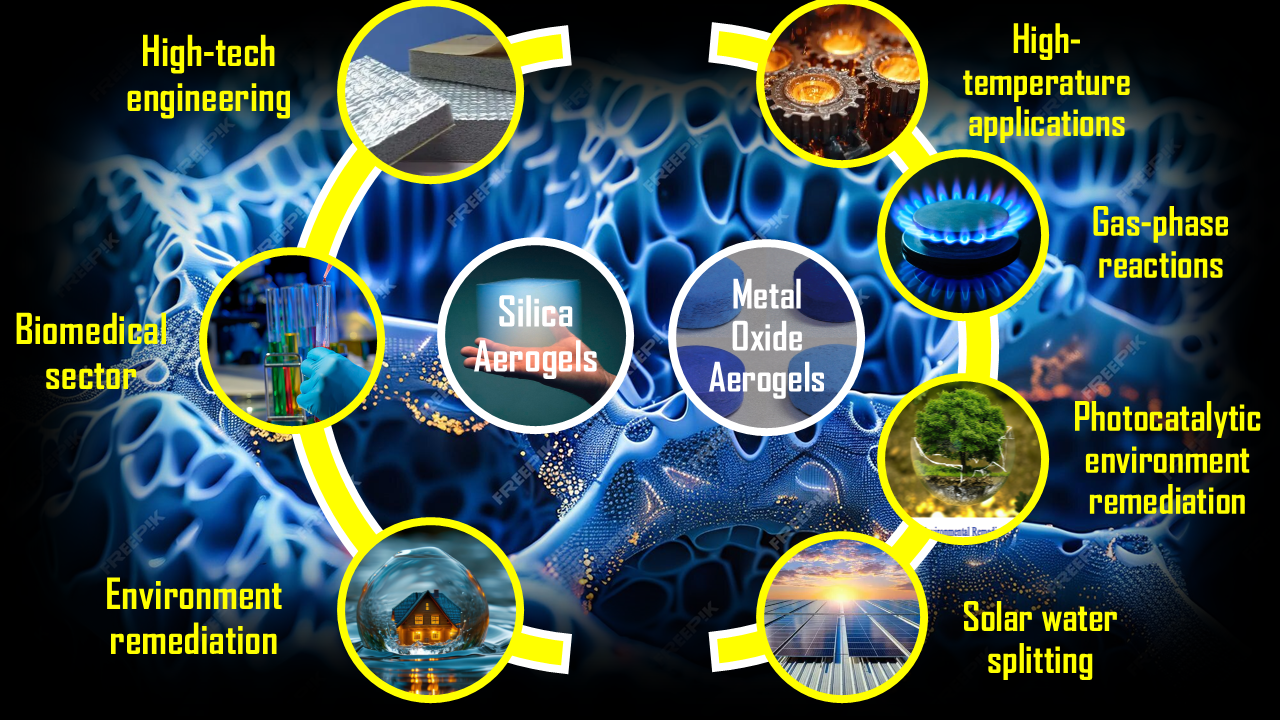

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

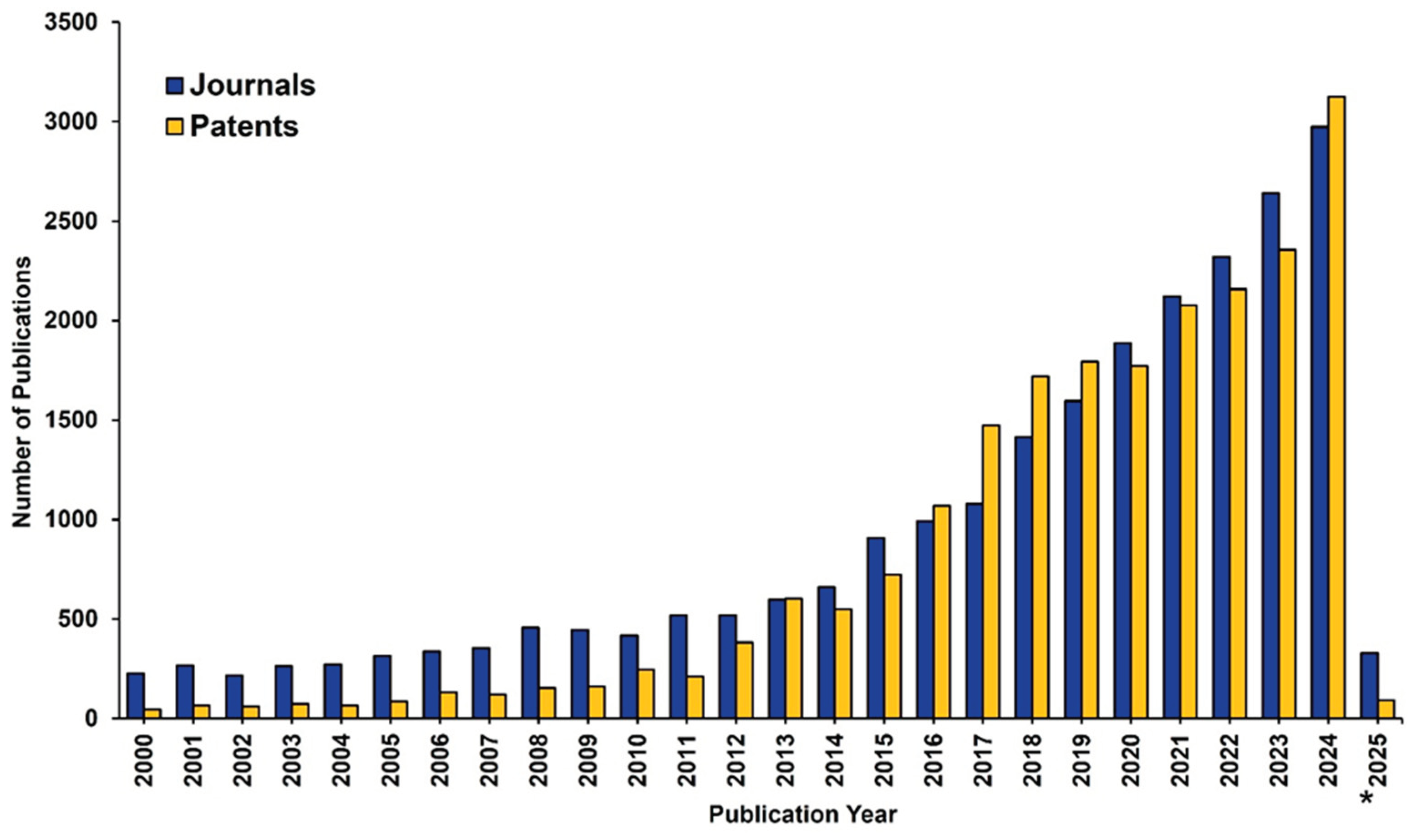

1. Introduction

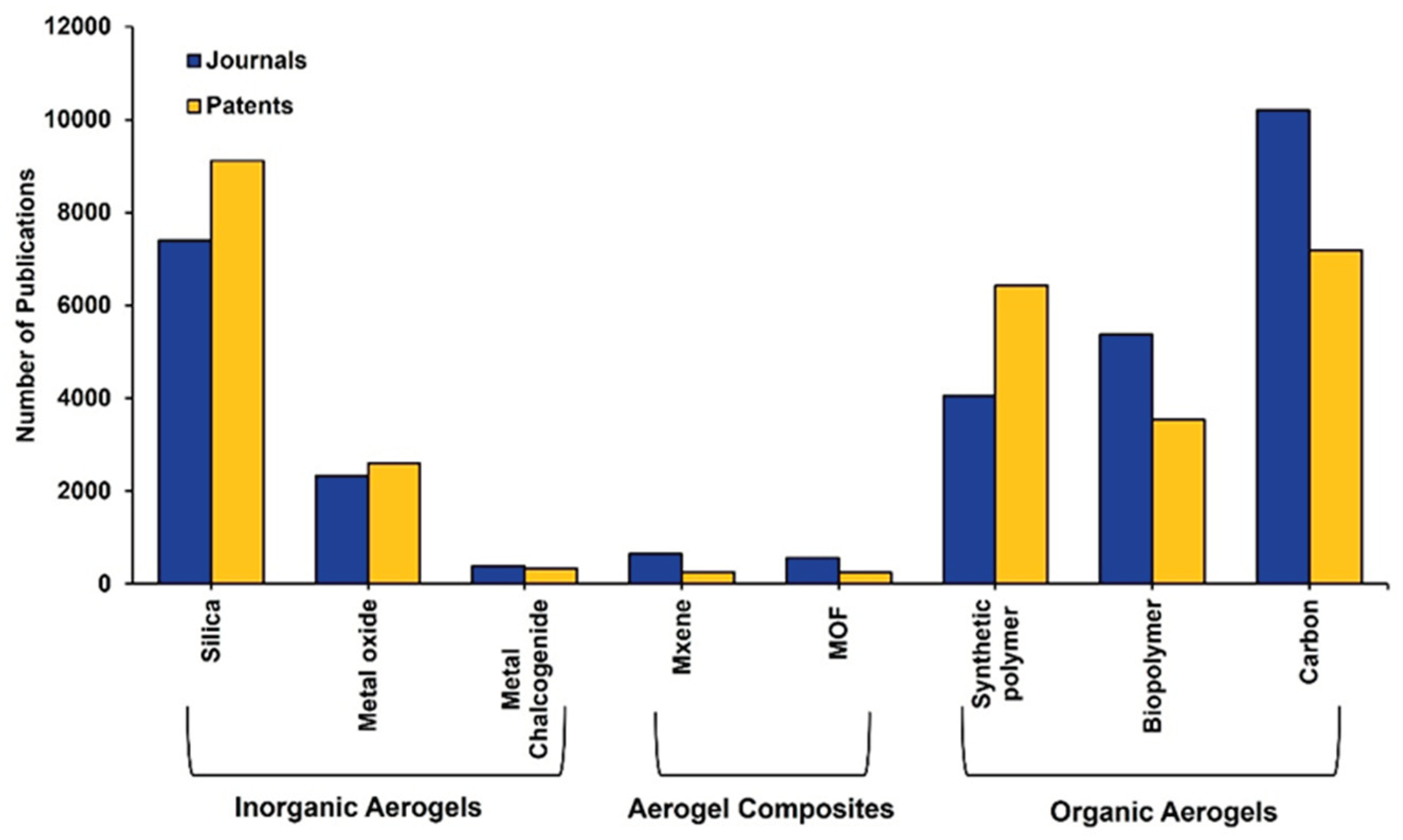

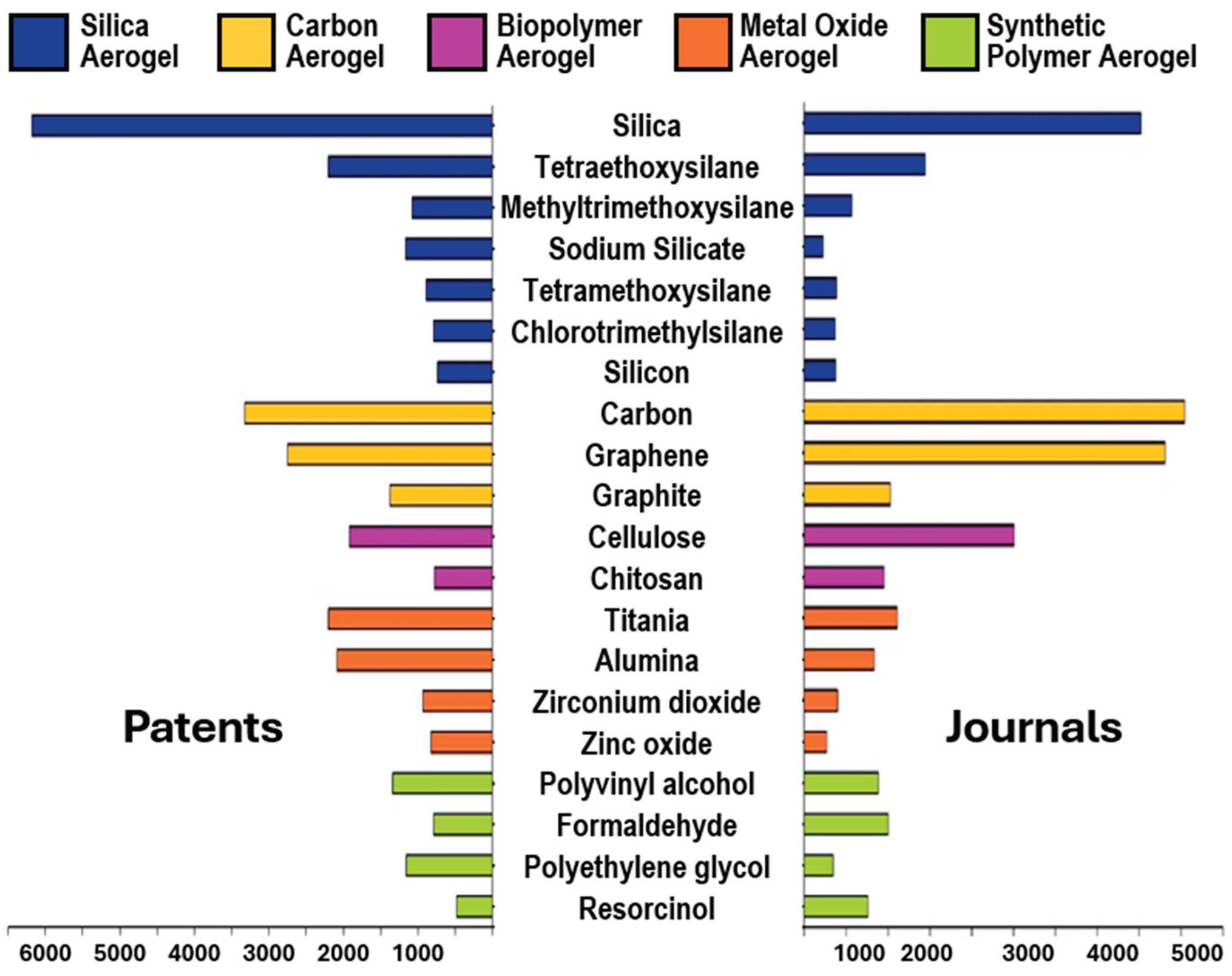

1.1. An Analysis of AGs According to the CAS Content Collection

2. Classification of Aerogels According to Their Chemical Origin

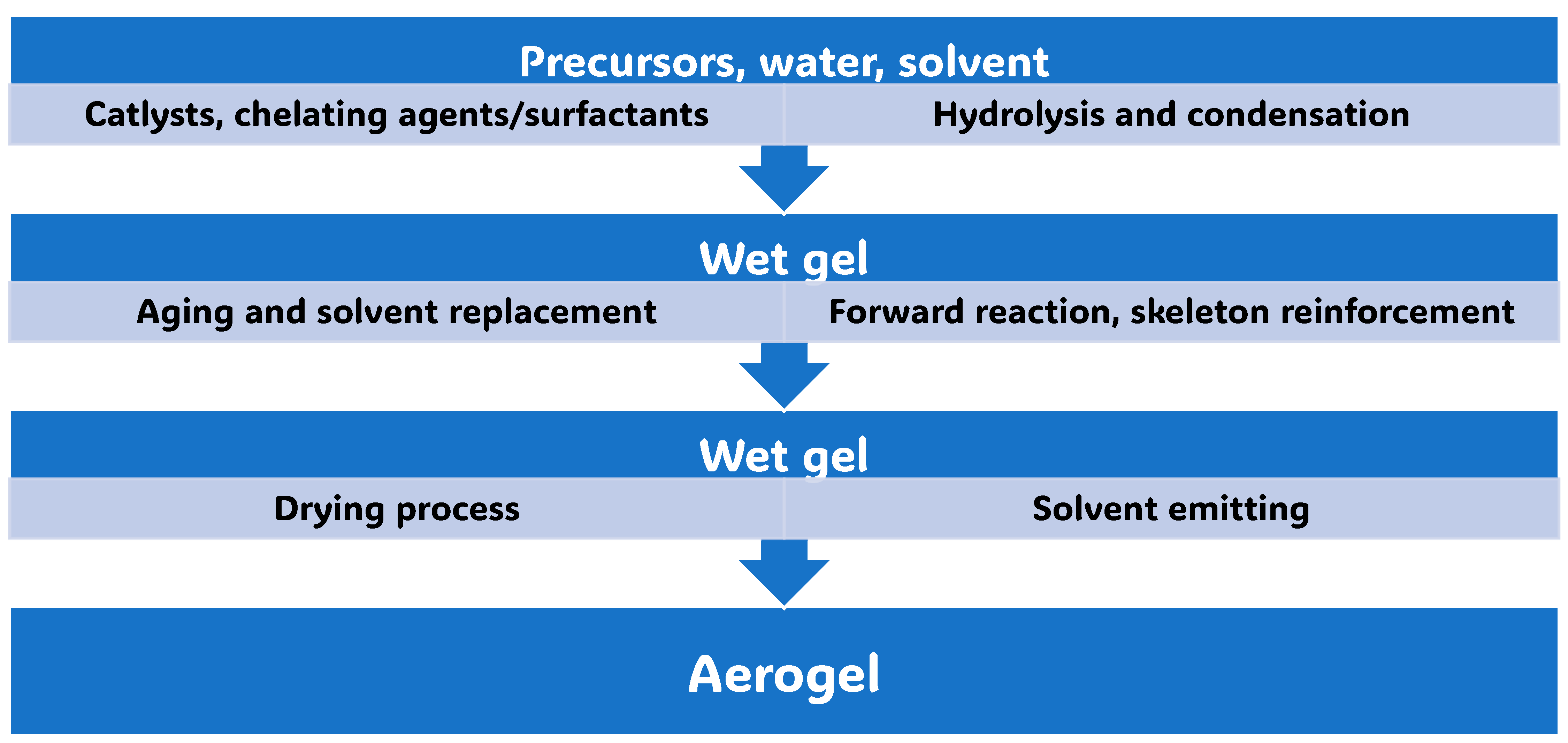

3. Synthetic Methods to Achieve Aerogels

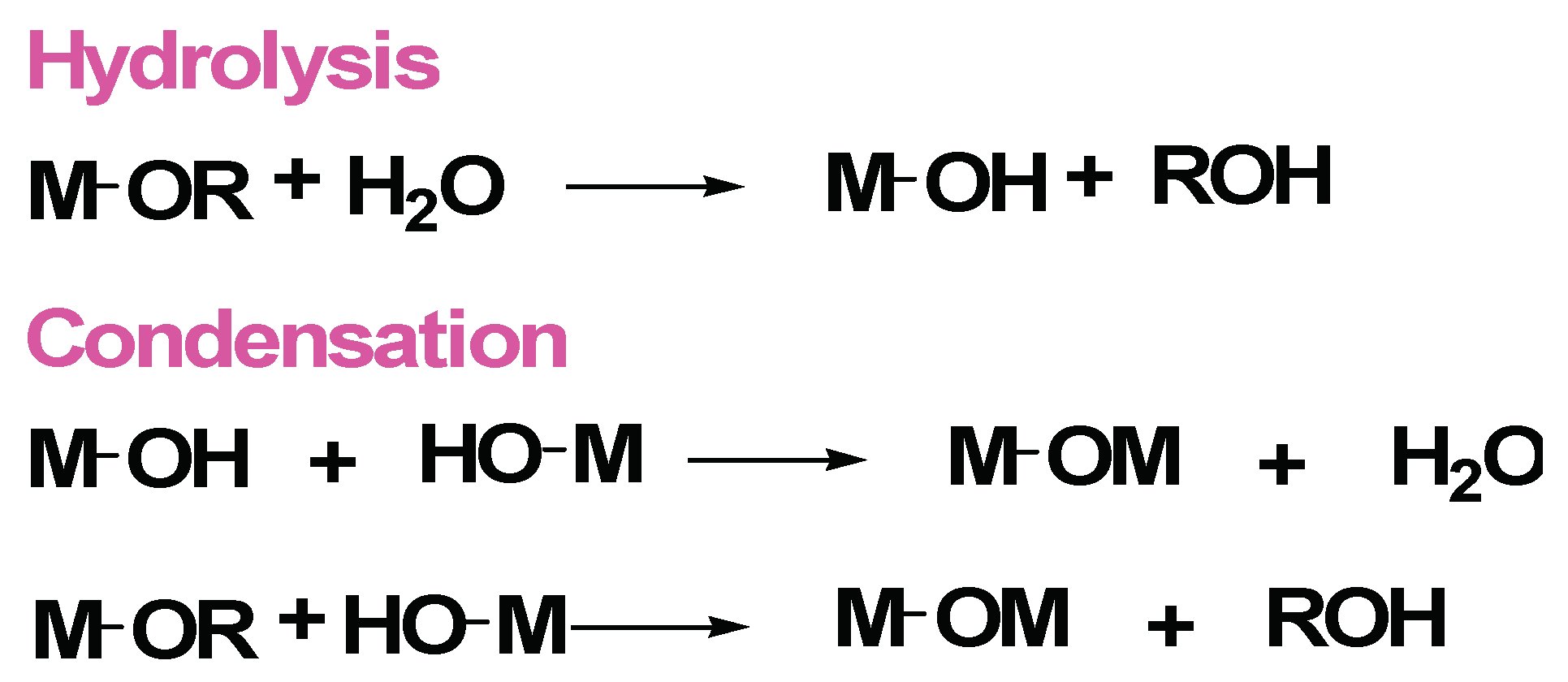

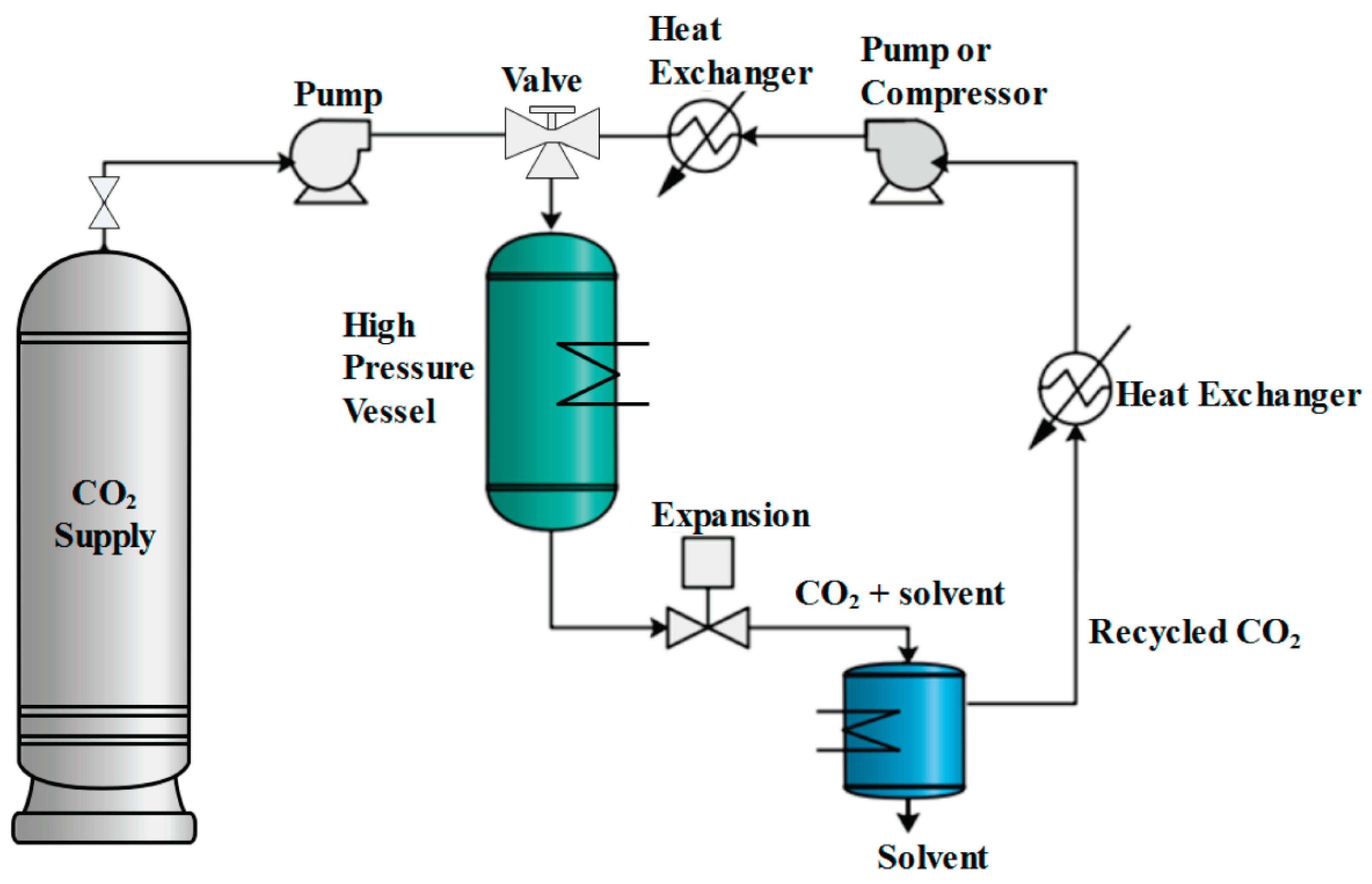

3.1. Molecular Routes to Aerogels (AGs) by Wet Sol-Gel Processes

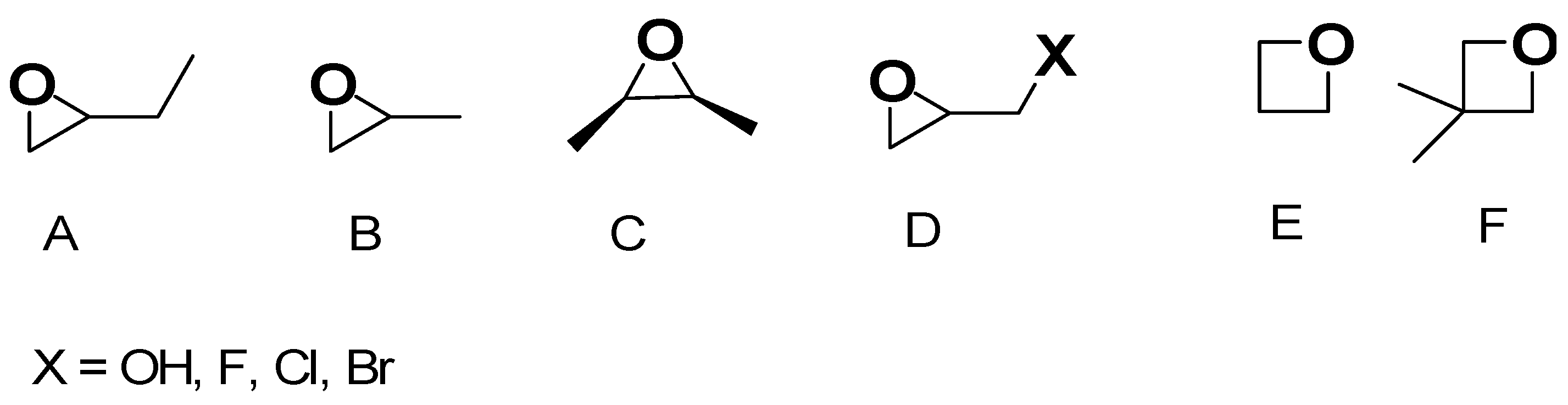

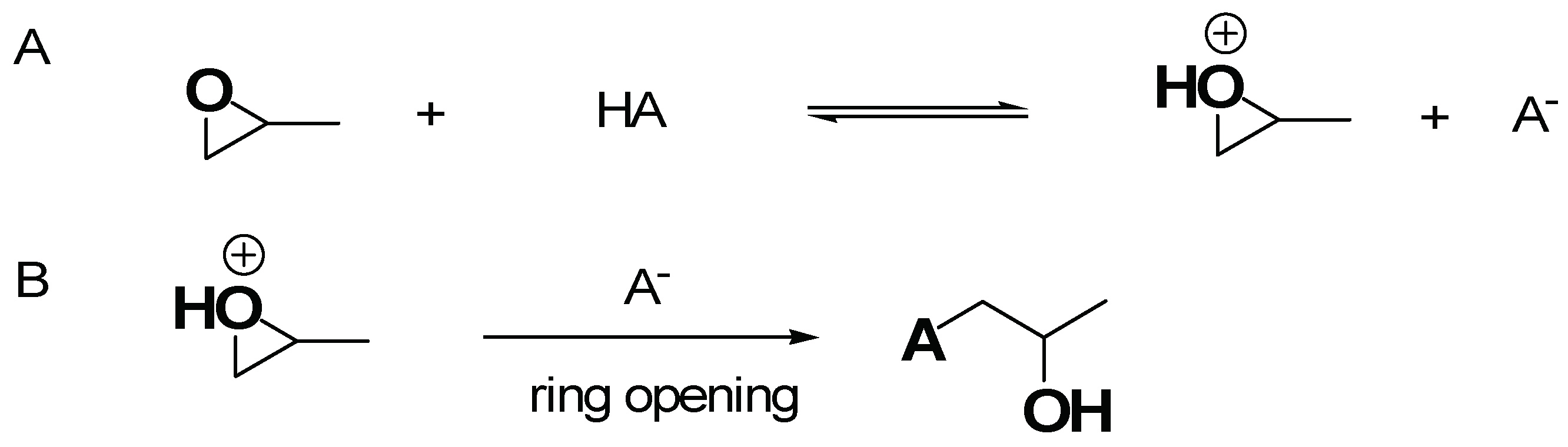

3.1.1. Improved Sol-Gel Procedure by Epoxide Addition Methods

3.1.2. Sol-Gel Methods to Prepare Noble Metal Aerogels (NMAGs)

3.1.3. Non-Sol-Gel Methods to Prepare Metallic Aerogels

Dealloying and Combustion

Bio-Templating

Salt Templating

3.2. Nanoparticle-Based Routes to Aerogels (AGs) by Wet Sol-Gel Processes

4. More in Deep into the Most Patented Classes of Inorganic Aerogels

4.1. Silica-Based Aerogels (SAGs)

4.1.1. Main Properties of SAGs

Case Studies

4.2. Metal Oxide-Based Aerogels (MOAGs)

4.2.1. Alumina Aerogels (ALAGs)

Case Studies

4.2.2. Zirconia Aerogels (ZRAGs)

Case Studies

4.2.3. Titania Aerogels (TIAGs)

Case Studies

4.2.4. Other Metal Oxide Aerogels (OMOAGs)

Case Studies

5. Opportunities, Challenges or Both?

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vadanagekar, A.; Lapcik, L.; Kvitek, L.; Lapcikova, B. Silica Aerogels as a Promising Vehicle for Effective Water Splitting for Hydrogen Production. Molecules 2025, 30, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hina Goyal Beyond Insulation: New Applications for Aerogels. Available online: https://www.cas.org/resources/cas-insights/aerogel-applications#:~:text=Inorganic%20aerogels%20not%20only%20encompass%20silica%20aerogels%20but,precursor%20materials%20like%20metal%20alkoxides%20or%20metal%20salts (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Wu, Y.; Liu, T.; Shi, Y.; Wang, H. Dramatically Enhancing Mechanical Properties of Hydrogels by Drying Reactive Polymers at Elevated Temperatures to Introduce Strong Physical and Chemical Crosslinks. Polymer (Guildf) 2022, 249, 124842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, S.; Rasheed, T.; Naz, R.; Majeed, S.; Bilal, M. Supercritical CO2 Drying of Pure Silica Aerogels: Effect of Drying Time on Textural Properties of Nanoporous Silica Aerogels. J Solgel Sci Technol 2021, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, S.; Maleki, H. Aerogels and Their Applications. Colloidal Metal Oxide Nanoparticles 2020, 337–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajonk, G.M. Catalytic Aerogels. Catal Today 1997, 35, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; Baiker, A. Aerogels in Catalysis. Catalysis Reviews 1995, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallribera, A.; Molins, E. Aerogel Supported Nanoparticles in Catalysis. In Nanoparticles and Catalysis; 2008.

- Rechberger, F.; Niederberger, M. Synthesis of Aerogels: From Molecular Routes to 3-Dimensional Nanoparticle Assembly. Nanoscale Horiz 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosticka, B.; Norris, P.M.; Brenizer, J.S.; Daitch, C.E. Gas Flow through Aerogels. J Non Cryst Solids 1998, 225, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerogels Handbook; Aegerter, M. A., Leventis, N., Koebel, M.M., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4419-7477-8. [Google Scholar]

- Burchell, M.J.; Graham, G.; Kearsley, A. Cosmic Dust Collection in Aerogel. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 2006, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurav, J.L.; Jung, I.-K.; Park, H.-H.; Kang, E.S.; Nadargi, D.Y. Silica Aerogel: Synthesis and Applications. J Nanomater 2010, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrubesh, L.W. Aerogel Applications. J Non Cryst Solids 1998, 225, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapliyal, P.C.; Singh, K. Aerogels as Promising Thermal Insulating Materials: An Overview. J Mater 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayen, R.J.; Iacobucci, P.A. Metal Oxide Aerogel Preparation by Supercritical Extraction. Reviews in Chemical Engineering 1988, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesser, H.D.; Goswami, P.C. Aerogels and Related Porous Materials. Chem Rev 1989, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, J.; Tillotson, T. Aerogels: Production, Characterization, and Applications. Thin Solid Films 1997, 297, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimov, Y.K. Fields of Application of Aerogels (Review). Instruments and Experimental Techniques 2003, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolison, D.R.; Dunn, B. Electrically Conductive Oxide Aerogels: New Materials in Electrochemistry. J Mater Chem 2001, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokov, D.; Turki Jalil, A.; Chupradit, S.; Suksatan, W.; Javed Ansari, M.; Shewael, I.H.; Valiev, G.H.; Kianfar, E. Nanomaterial by Sol-Gel Method: Synthesis and Application. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinle, A.; Hüsing, N. Mixed Metal Oxide Aerogels from Tailor-Made Precursors. J Supercrit Fluids 2015, 106, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, A.; Zhou, B.; Shen, J.; Gui, J.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, G. A Versatile Sol-Gel Route to Monolithic Oxidic Gels via Polyacrylic Acid Template. New Journal of Chemistry 2011, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemere, E.B.; Mhlabeni, T.L.; Mhike, W.; Mavhungu, M.L.; Shongwe, M.B. A Comprehensive Review of Types, Synthesis Strategies, Advanced Designing and Applications of Aerogels. R Soc Open Sci 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaponik, N.; Herrmann, A.K.; Eychmüller, A. Colloidal Nanocrystal-Based Gels and Aerogels: Material Aspects and Application Perspectives. Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meti, P.; Wang, Q.; Mahadik, D.B.; Lee, K.Y.; Gong, Y.D.; Park, H.H. Evolutionary Progress of Silica Aerogels and Their Classification Based on Composition: An Overview. Nanomaterials 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, S.; Sheikh, J.N. Silica Centered Aerogels as Advanced Functional Material and Their Applications: A Review. J Non Cryst Solids 2023, 611, 122322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Arachchige, I.U.; Kanatzidis, M.G. Aerogels from Metal Chalcogenides and Their Emerging Unique Properties. J Mater Chem 2008, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangi, U.K.H.; Lee, K.-Y.; Maldar, N.M.N.; Park, H.-H. Synthesis and Properties of Metal Oxide Aerogels via Ambient Pressure Drying. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Cao, H.; Liao, J.; Du, R.; Dou, K.; Tsidaeva, N.; Wang, W. 3D Porous Coral-like Co1.29Ni1.71O4 Microspheres Embedded into Reduced Graphene Oxide Aerogels with Lightweight and Broadband Microwave Absorption. J Colloid Interface Sci 2022, 609, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Li, Q.; Li, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, W. Construction of Novel Magnesium Oxide Aerogel for Highly Efficient Separation of Uranium(VI) from Wastewater. Sep Purif Technol 2022, 295, 121296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistler, S.S. Coherent Expanded Aerogels and Jellies [5]. Nature 1931, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.J.; Kang, Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Baek, S.W.; Hwang, H. Synthesis of Silicon Carbide Powders from Methyl-Modified Silica Aerogels. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oschatz, M.; Boukhalfa, S.; Nickel, W.; Hofmann, J.P.; Fischer, C.; Yushin, G.; Kaskel, S. Carbide-Derived Carbon Aerogels with Tunable Pore Structure as Versatile Electrode Material in High Power Supercapacitors. Carbon N Y 2017, 113, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.; Amiinu, I.S.; Kou, Z.; Li, W.; Mu, S. RuP2-Based Catalysts with Platinum-like Activity and Higher Durability for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction at All PH Values. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Ruan, Q.; Xie, J.; Chen, X.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, J. Oxygen-Doped Carbon Nitride Aerogel: A Self-Supported Photocatalyst for Solar-to-Chemical Energy Conversion. Appl Catal B 2018, 236, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Feng, Y.; Feng, W. Photothermal Storage and Controllable Release of a Phase-Change Azobenzene/Aluminum Nitride Aerogel Composite. Composites Communications 2021, 23, 100575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, G.; Xu, L.; Liao, J.; Zhang, X. Nanoporous Boron Nitride Aerogel Film and Its Smart Composite with Phase Change Materials. ACS Nano 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna Kumar, A.S.; Warchol, J.; Matusik, J.; Tseng, W.L.; Rajesh, N.; Bajda, T. Heavy Metal and Organic Dye Removal via a Hybrid Porous Hexagonal Boron Nitride-Based Magnetic Aerogel. NPJ Clean Water 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Du, R.; Hübner, R.; Hu, Y.; Eychmüller, A. A Roadmap for 3D Metal Aerogels: Materials Design and Application Attempts. Matter 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nita, L.E.; Ghilan, A.; Rusu, A.G.; Neamtu, I.; Chiriac, A.P. New Trends in Bio-Based Aerogels. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Budtova, T.; Ratke, L.; Gurikov, P.; Baudron, V.; Preibisch, I.; Niemeyer, P.; Smirnova, I.; Milow, B. Review on the Production of Polysaccharide Aerogel Particles. Materials 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Dong, W.; Pan, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Long, D. Lightweight and Flexible Phenolic Aerogels with Three-Dimensional Foam Reinforcement for Acoustic and Thermal Insulation. Ind Eng Chem Res 2021, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derflinger, C.; Kamm, B.; Paulik, C. Sustainable Aerogels Derived from Bio-Based 2,5-Diformylfuran and Depolymerization Products of Lignin. International Journal of Biobased Plastics 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PEKALA, R.W.; KONG, F.M. A SYNTHETIC ROUTE TO ORGANIC AEROGELS - MECHANISM, STRUCTURE, AND PROPERTIES. Le Journal de Physique Colloques 1989, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventis, N. Polyurea Aerogels: Synthesis, Material Properties, and Applications. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merillas, B.; Martín-De León, J.; Villafañe, F.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.A. Transparent Polyisocyanurate-Polyurethane-Based Aerogels: Key Aspects on the Synthesis and Their Porous Structures. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, M.; García-González, C.A.; Subrahmanyam, R.P.; Smirnova, I.; Kulozik, U. Preparation of Novel Whey Protein-Based Aerogels as Drug Carriers for Life Science Applications. Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2012, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmer, I.; Kleemann, C.; Kulozik, U.; Heinrich, S.; Smirnova, I. Development of Egg White Protein Aerogels as New Matrix Material for Microencapsulation in Food. Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2015, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvasekaran, P.; Chidambaram, R. Food-Grade Aerogels Obtained from Polysaccharides, Proteins, and Seed Mucilages: Role as a Carrier Matrix of Functional Food Ingredients. Trends Food Sci Technol 2021, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, J.; Kumar, V.; Garg, A.K.; Dubey, P.; Tripathi, K.M.; Sonkar, S.K. Bio-Mass Derived Functionalized Graphene Aerogel: A Sustainable Approach for the Removal of Multiple Organic Dyes and Their Mixtures. New Journal of Chemistry 2021, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yuan, D.; Guo, Q.; Qiu, F.; Yang, D.; Ou, Z. Preparation of a Renewable Biomass Carbon Aerogel Reinforced with Sisal for Oil Spillage Clean-up: Inspired by Green Leaves to Green Tofu. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2019, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Duan, T.; Zhou, D.; Wang, L.; Zhou, J.; Kuang, M. Environment-Friendly Bio-Materials Based on Cotton-Carbon Aerogel for Strontium Removal from Aqueous Solution. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 2018, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani Dorcheh, A.; Abbasi, M.H. Silica Aerogel; Synthesis, Properties and Characterization. J Mater Process Technol 2008, 199, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, G.; Lewis, D.; McKinley, K.; Richardson, J.; Tillotson, T. Aerogel Commercialization: Technology, Markets and Costs. J Non Cryst Solids 1995, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Trikalitis, P.N.; Chupas, P.J.; Armatas, G.S.; Kanatzidis, M.G. Porous Semiconducting Gels and Aerogels from Chalcogenide Clusters. Science (1979) 2007, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Gaudette, A.F.; Bussell, M.E.; Kanatzidis, M.G. Spongy Chalcogels of Non-Platinum Metals Act as Effective Hydrodesulfurization Catalysts. Nat Chem 2009, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polychronopoulou, K.; Malliakas, C.D.; He, J.; Kanatzidis, M.G. Selective Surfaces: Quaternary Co(Ni)MoS-Based Chalcogels with Divalent (Pb 2+, Cd 2+, Pd 2+) and Trivalent (Cr 3+, Bi 3+) Metals for Gas Separation. Chemistry of Materials 2012, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.; Bag, S.; Malliakas, C.D.; Kanatzidis, M.G. Selective Surfaces: High-Surface-Area Zinc Tin Sulfide Chalcogels. Chemistry of Materials 2011, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, B.J.; Chun, J.; Ryan, J. V.; Matyáš, J.; Li, X.S.; Matson, D.W.; Sundaram, S.K.; Strachan, D.M.; Vienna, J.D. Chalcogen-Based Aerogels as a Multifunctional Platform for Remediation of Radioactive Iodine. RSC Adv 2011, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, C.; Wolf, A.; Liu, W.; Herrmann, A.K.; Gaponik, N.; Eychmüller, A. Modern Inorganic Aerogels. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition, 2017, 56.

- Choi, H.; Parale, V.G.; Kim, T.; Choi, Y.S.; Tae, J.; Park, H.H. Structural and Mechanical Properties of Hybrid Silica Aerogel Formed Using Triethoxy(1-Phenylethenyl)Silane. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2020, 298, 110092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A. Bin; Shishir, S.I.; Mahfuz, M.A.; Hossain, M.T.; Hoque, M.E. Silica Aerogel: Synthesis, Characterization, Applications, and Recent Advancements. Particle and Particle Systems Characterization 2023, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederberger, M.; Pinna, N. Metal Oxide Nanoparticles in Organic Solvents; Springer London: London, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84882-670-0. [Google Scholar]

- Brinker, C.J.; Scherer, G.W. Sol-Gel Science: The Physics and Chemistry of Sol-Gel Processing; 2013.

- Feinle, A.; Elsaesser, M.S.; Hüsing, N. Sol-Gel Synthesis of Monolithic Materials with Hierarchical Porosity. Chem Soc Rev 2016, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerogels Handbook; 2011.

- Nakagawa, Y.; Kageyama, H.; Oaki, Y.; Imai, H. Direction Control of Oriented Self-Assembly for 1D, 2D, and 3D Microarrays of Anisotropic Rectangular Nanoblocks. J Am Chem Soc 2014, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, İ.; Özbakır, Y.; İnönü, Z.; Ulker, Z.; Erkey, C. Kinetics of Supercritical Drying of Gels. Gels 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estok, S.K.; Hughes, T.A.; Carroll, M.K.; Anderson, A.M. Fabrication and Characterization of TEOS-Based Silica Aerogels Prepared Using Rapid Supercritical Extraction. J Solgel Sci Technol 2014, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.M.; Carroll, M.K.; Green, E.C.; Melville, J.T.; Bono, M.S. Hydrophobic Silica Aerogels Prepared via Rapid Supercritical Extraction. J Solgel Sci Technol 2010, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoda, S.; Ohshima, S. Supercritical Drying Media Modification for Silica Aerogel Preparation. J Non Cryst Solids 1999, 248, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quignard, F.; Valentin, R.; Di Renzo, F. Aerogel Materials from Marine Polysaccharides. New Journal of Chemistry 2008, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinker, C.J.; Keefer, K.D.; Schaefer, D.W.; Ashley, C.S. Sol-Gel Transition in Simple Silicates. J Non Cryst Solids 1982, 48, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Shan, G. Elastic Silica Aerogel Using Methyltrimethoxysilane Precusor via Ambient Pressure Drying. Journal of Porous Materials 2015, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Chen, K.; Ma, D.; Lin, H.; Liu, Z.; Qin, S.; Luo, Y. Synthesis of High Specific Surface Area Silica Aerogel from Rice Husk Ash via Ambient Pressure Drying. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2018, 539, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Guo, T.; Zhang, J.; He, L.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Zhu, X.; Gao, Y. Facile Synthesis of Large-Sized Monolithic Methyltrimethoxysilane-Based Silica Aerogel via Ambient Pressure Drying. J Solgel Sci Technol 2017, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, Y.; Ye, W.; Shen, X.; Yuan, X.; Ma, C.; Cao, Y. Performance Regulation of Silica Aerogel Powder Synthesized by a Two-Step Sol-Gel Process with a Fast Ambient Pressure Drying Route. J Non Cryst Solids 2021, 567, 120923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Fan, M.; Mclaughlin, J.F.; Shen, X.; Tan, G. A Novel Low-Cost Method of Silica Aerogel Fabrication Using Fly Ash and Trona Ore with Ambient Pressure Drying Technique. Powder Technol 2018, 323, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; He, S.; Gong, L.; Cheng, X.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H. Low Thermal-Conductivity and High Thermal Stable Silica Aerogel Based on MTMS/Water-Glass Co-Precursor Prepared by Freeze Drying. Mater Des 2017, 113, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Cheng, X.; Pan, Y.; Li, C.; Gong, L.; Zhang, H. Mechanical Performance and Thermal Stability of Glass Fiber Reinforced Silica Aerogel Composites Based on Co-Precursor Method by Freeze Drying. Appl Surf Sci 2018, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillotson, T.M.; Sunderland, W.E.; Thomas, I.M.; Hrubesh, L.W. Synthesis of Lanthanide and Lanthanide-Silicate Aerogels. J Solgel Sci Technol 1994, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gash, A.E.; Tillotson, T.M.; Satcher, J.H.; Poco, J.F.; Hrubesh, L.W.; Simpson, R.L. Use of Epoxides in the Sol-Gel Synthesis of Porous Iron(III) Oxide Monoliths from Fe(III) Salts. Chemistry of Materials 2001, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gash, A.E.; Tillotson, T.M.; Satcher, J.H.; Hrubesh, L.W.; Simpson, R.L. New Sol–Gel Synthetic Route to Transition and Main-Group Metal Oxide Aerogels Using Inorganic Salt Precursors. J Non Cryst Solids 2001, 285, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gash, A.E.; Satcher, J.H.; Simpson, R.L. Strong Akaganeite Aerogel Monoliths Using Epoxides: Synthesis and Characterization. Chemistry of Materials 2003, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.W.; Logan, M.S.; Rhodes, C.P.; Carpenter, E.E.; Stroud, R.M.; Rolison, D.R. Nanocrystalline Iron Oxide Aerogels as Mesoporous Magnetic Architectures. J Am Chem Soc 2004, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chai, C.P.; Luo, Y.J.; Wang, L.; Li, G.P. Synthesis, Structure and Electromagnetic Properties of Mesoporous Fe3O4 Aerogels by Sol–Gel Method. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2014, 188, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kido, Y.; Nakanishi, K.; Miyasaka, A.; Kanamori, K. Synthesis of Monolithic Hierarchically Porous Iron-Based Xerogels from Iron(III) Salts via an Epoxide-Mediated Sol-Gel Process. Chemistry of Materials 2012, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, S.; Huggins, F.E.; Huffman, G.P.; Ernst, R.D.; Pugmire, R.J.; Eyring, E.M. Iron Aerogel and Xerogel Catalysts for Fischer - Tropsch Synthesis of Diesel Fuel. Energy and Fuels 2009, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, S.; Turpin, G.C.; Ernst, R.D.; Pugmire, R.J.; Singh, V.; Seehra, M.S.; Eyring, E.M. Water Gas Shift Catalysis Using Iron Aerogels Doped with Palladium by the Gas-Phase Incorporation Method. Energy and Fuels 2008, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleel, A.; Al-Marzouqi, A. Alkoxide-Free Sol–Gel Synthesis of Aerogel Iron–Chromium Mixed Oxides with Unique Textural Properties. Mater Lett 2012, 68, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.Y.; Chen, C.H.; Chien, H.C.; Lu, S.Y.; Hu, C.C. A Cost-Effective Supercapacitor Material of Ultrahigh Specific Capacitances: Spinel Nickel Cobaltite Aerogels from an Epoxide-Driven Sol-Gel Process. Advanced Materials 2010, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, T.F.; Gash, A.E.; Chinn, S.C.; Sawvel, A.M.; Maxwell, R.S.; Satcher, J.H. Synthesis of High-Surface-Area Alumina Aerogels without the Use of Alkoxide Precursors. Chemistry of Materials 2005, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Xu, Z.; Feng, Y.; Chen, L. Synthesis of Alumina Aerogels by Ambient Drying Method and Control of Their Structures. Journal of Porous Materials 2005, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokudome, Y.; Nakanishi, K.; Kanamori, K.; Fujita, K.; Akamatsu, H.; Hanada, T. Structural Characterization of Hierarchically Porous Alumina Aerogel and Xerogel Monoliths. J Colloid Interface Sci 2009, 338, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Meyer-Zaika, W.; Muhler, M.; Vukojević, S.; Epple, M. Cu/Zn/Al Xerogels and Aerogels Prepared by a Sol-Gel Reaction as Catalysts for Methanol Synthesis. Eur J Inorg Chem 2006. [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.K.; Brown, P.; Ogundiya, M.T.; Hope-Weeks, L.J. High Surface Area Alumina-Supported Nickel (II) Oxide Aerogels Using Epoxide Addition Method. J Solgel Sci Technol 2010, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chervin, C.N.; Clapsaddle, B.J.; Chiu, H.W.; Gash, A.E.; Satcher, J.H.; Kauzlarich, S.M. Aerogel Synthesis of Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia by a Non-Alkoxide Sol-Gel Route. Chemistry of Materials 2005, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chervin, C.N.; Clapsaddle, B.J.; Chiu, H.W.; Gash, A.E.; Satcher, J.H.; Kauzlarich, S.M. Role of Cyclic Ether and Solvent in a Non-Alkoxide Sol-Gel Synthesis of Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia Nanoparticles. Chemistry of Materials 2006, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiao, Y.; Ji, H.; Sun, X. The Effect of Propylene Oxide on Microstructure of Zirconia Monolithic Aerogel. Integrated Ferroelectrics 2013, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, H.; Brandt, S.; Milow, B.; Ichilmann, S.; Steinhart, M.; Ratke, L. Zirconia-Based Aerogels via Hydrolysis of Salts and Alkoxides: The Influence of the Synthesis Procedures on the Properties of the Aerogels. Chem Asian J 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Chen, X.; Song, H.; Guo, K.; Hu, Z. Synthesis of Monolithic Zirconia Aerogel via a Nitric Acid Assisted Epoxide Addition Method. RSC Adv 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, T.F.; Kucheyev, S.O.; Gash, A.E.; Satcher, J.H. Facile Synthesis of a Crystalline, High-Surface-Area SnO2 Aerogel. Advanced Materials 2005, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.P.; Sisk, C.N.; Hope-Weeks, L.J. A Sol-Gel Route to Synthesize Monolithic Zinc Oxide Aerogels. Chemistry of Materials 2007, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Chen, G.; Zeng, T.; Liu, T.; Mei, Y.; Bi, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhang, L. Monolithic Zinc Oxide Aerogel with the Building Block of Nanoscale Crystalline Particle. Journal of Porous Materials 2013, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Wei, C.; Zhang, L. Monolithic ZnO Aerogel Synthesized through Dispersed Inorganic Sol–Gel Method Using Citric Acid as Template. Journal of Porous Materials 2014, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Zhang, K.; Wang, S.; Hope-Weeks, L.J. Enhanced Electrical Conductivity in Mesoporous 3D Indium-Tin Oxide Materials. J Mater Chem 2012, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, A.; Qian, Y.; Stein, A. Porous Electrode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries-How to Prepare Them and What Makes Them Special. Adv Energy Mater 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Gu, J.; Su, L.; Cheng, L. An Overview of Metal Oxide Materials as Electrocatalysts and Supports for Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cells. Energy Environ Sci 2014, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellmer, K. Past Achievements and Future Challenges in the Development of Optically Transparent Electrodes. Nat Photonics 2012, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Bozyigit, D.; Wood, V.; Niederberger, M. High-Quality Transparent Electrodes Spin-Cast from Preformed Antimony-Doped Tin Oxide Nanocrystals for Thin Film Optoelectronics. Chemistry of Materials 2013, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, W.A. A Review on Solar Cells from Si-Single Crystals to Porous Materials and Quantum Dots. J Adv Res 2015, 6, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa Baena, J.P.; Agrios, A.G. Antimony-Doped Tin Oxide Aerogels as Porous Electron Collectors for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2014, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa Baena, J.P.; Agrios, A.G. Transparent Conducting Aerogels of Antimony-Doped Tin Oxide. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucheyev, S.O.; Van Buuren, T.; Baumann, T.F.; Satcher, J.H.; Willey, T.M.; Meulenberg, R.W.; Felter, T.E.; Poco, J.F.; Gammon, S.A.; Terminello, L.J. Electronic Structure of Titania Aerogels from Soft X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy. Phys Rev B Condens Matter Mater Phys 2004, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Shin, C.B.; Suh, D.J. Polyvanadate Dominant Vanadia-Alumina Composite Aerogels Prepared by a Non-Alkoxide Sol-Gel Method. J Mater Chem 2009, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, G.R.; Hung-Low, F.; Gumeci, C.; Bassett, W.P.; Korzeniewski, C.; Hope-Weeks, L.J. Preparation-Morphology-Performance Relationships in Cobalt Aerogels as Supercapacitors. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reibold, R.A.; Poco, J.F.; Baumann, T.F.; Simpson, R.L.; Satcher, J.H. Synthesis and Characterization of a Low-Density Urania (UO3) Aerogel. J Non Cryst Solids 2003, 319, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.D.; Li, B.; Zheng, Q.X.; Jiang, M.H.; Tao, X.T. Synthesis and Characterization of Monolithic Gd2O3 Aerogels. J Non Cryst Solids 2008, 354, 4089–4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapsaddle, B.J.; Neumann, B.; Wittstock, A.; Sprehn, D.W.; Gash, A.E.; Satcher, J.H.; Simpson, R.L.; Bäumer, M. A Sol-Gel Methodology for the Preparation of Lanthanide-Oxide Aerogels: Preparation and Characterization. J Solgel Sci Technol 2012, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, H.; Milow, B.; Ratke, L. Synthesis of Inorganic Aerogels via Rapid Gelation Using Chloride Precursors. RSC Adv 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zhang, L.; Shang, C.; Wang, X.; Bi, Y. Synthesis of a Low-Density Tantalum Oxide Tile-like Aerogel Monolithic. J Solgel Sci Technol 2010, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Gümeci, C.; Kiel, C.; Hope-Weeks, L.J. Preparation of Porous Manganese Oxide Nanomaterials by One-Pot Synthetic Sol-Gel Method. J Solgel Sci Technol 2011, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.D.; Gill, S.K.; Hope-Weeks, L.J. Influence of Solvent on Porosity and Microstructure of an Yttrium Based Aerogel. J Mater Chem 2011, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, J.; Pierre, A.C.; Baret, G. Preparation and Characterization of Transparent Eu Doped Y2O3 Aerogel Monoliths, for Application in Luminescence. J Non Cryst Solids 2005, 351, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reibold, R.A.; Poco, J.F.; Baumann, T.F.; Simpson, R.L.; Satcher, J.H. Synthesis and Characterization of a Nanocrystalline Thoria Aerogel. J Non Cryst Solids 2004, 341, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Bang, Y.; Han, S.J.; Park, S.; Song, J.H.; Song, I.K. Hydrogen Production by Tri-Reforming of Methane over Nickel–Alumina Aerogel Catalyst. J Mol Catal A Chem 2015, 410, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Cearnaigh, D.U.; Fung, E.K.; Hope-Weeks, L.J. Controlling the Morphology of a Zinc Ferrite-Based Aerogel by Choice of Solvent. J Solgel Sci Technol 2012, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Hope-Weeks, L.J. The Synthesis and Characterization of Zinc Ferrite Aerogels Prepared by Epoxide Addition. J Solgel Sci Technol 2009, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chervin, C.N.; Ko, J.S.; Miller, B.W.; Dudek, L.; Mansour, A.N.; Donakowski, M.D.; Brintlinger, T.; Gogotsi, P.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Shibata, T.; et al. Defective by Design: Vanadium-Substituted Iron Oxide Nanoarchitectures as Cation-Insertion Hosts for Electrochemical Charge Storage. J Mater Chem A Mater 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chervin, C.N.; Clapsaddle, B.J.; Chiu, H.W.; Gash, A.E.; Satcher, J.H.; Kauzlarich, S.M. A Non-Alkoxide Sol-Gel Method for the Preparation of Homogeneous Nanocrystalline Powders of La 0.85Sr 0.15MnO 3. Chemistry of Materials 2006, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.W.; Logan, M.S.; Carpenter, E.E.; Rolison, D.R. Synthesis and Characterization of Mn–FeOx Aerogels with Magnetic Properties. J Non Cryst Solids 2004, 350, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, K.A.; Long, J.W.; Carpenter, E.E.; Baker, C.C.; Lytle, J.C.; Chervin, C.N.; Logan, M.S.; Stroud, R.M.; Rolison, D.R. Nickel Ferrite Aerogels with Monodisperse Nanoscale Building Blocks - The Importance of Processing Temperature and Atmosphere. ACS Nano 2008, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lan, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q. Hydrogen Bonding Directed Assembly of Simonkolleite Aerogel by a Sol–Gel Approach. Mater Des 2016, 93, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gash, A.E.; Satcher, J.H.; Simpson, R.L. Monolithic Nickel(II)-Based Aerogels Using an Organic Epoxide: The Importance of the Counterion. J Non Cryst Solids 2004, 350, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, A.; Zhou, B.; Shen, J.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, C.; Zhang, M. Monolithic Copper Oxide Aerogel via Dispersed Inorganic Sol–Gel Method. J Non Cryst Solids 2009, 355, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Herrmann, A.K.; Bigall, N.C.; Rodriguez, P.; Wen, D.; Oezaslan, M.; Schmidt, T.J.; Gaponik, N.; Eychmüller, A. Noble Metal Aerogels-Synthesis, Characterization, and Application as Electrocatalysts. Acc Chem Res 2015, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fang, Q.; Gu, W.; Du, D.; Lin, Y.; Zhu, C. Noble Metal Aerogels. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12, 52234–52250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burpo, F.J. Noble Metal Aerogels. In Springer Handbooks; 2023; Vol. Part F1485.

- Bigall, N.C.; Herrmann, A.K.; Vogel, M.; Rose, M.; Simon, P.; Carrillo-Cabrera, W.; Dorfs, D.; Kaskel, S.; Gaponik, N.; Eychmüller, A. Hydrogels and Aerogels from Noble Metal Nanoparticles. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition, 2009, 48. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, A.K.; Formanek, P.; Borchardt, L.; Klose, M.; Giebeler, L.; Eckert, J.; Kaskel, S.; Gaponik, N.; Eychmüller, A. Multimetallic Aerogels by Template-Free Self-Assembly of Au, Ag, Pt, and Pd Nanoparticles. Chemistry of Materials 2014, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranmohotti, K.G.S.; Gao, X.; Arachchige, I.U. Salt-Mediated Self-Assembly of Metal Nanoshells into Monolithic Aerogel Frameworks. Chemistry of Materials 2013, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Esteves, R.J.; Luong, T.T.H.; Jaini, R.; Arachchige, I.U. Oxidation-Induced Self-Assembly of Ag Nanoshells into Transparent and Opaque Ag Hydrogels and Aerogels. J Am Chem Soc 2014, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühn, L.; Herrmann, A.K.; Rutkowski, B.; Oezaslan, M.; Nachtegaal, M.; Klose, M.; Giebeler, L.; Gaponik, N.; Eckert, J.; Schmidt, T.J.; et al. Alloying Behavior of Self-Assembled Noble Metal Nanoparticles. Chemistry - A European Journal, 2016, 22. [CrossRef]

- Oezaslan, M.; Herrmann, A.K.; Werheid, M.; Frenkel, A.I.; Nachtegaal, M.; Dosche, C.; Laugier Bonnaud, C.; Yilmaz, H.C.; Kühn, L.; Rhiel, E.; et al. Structural Analysis and Electrochemical Properties of Bimetallic Palladium–Platinum Aerogels Prepared by a Two-Step Gelation Process. ChemCatChem 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Dianat, A.; Hübner, R.; Liu, W.; Wen, D.; Benad, A.; Sonntag, L.; Gemming, T.; Cuniberti, G.; Eychmüller, A. Multimetallic Hierarchical Aerogels: Shape Engineering of the Building Blocks for Efficient Electrocatalysis. Advanced Materials 2017, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Wen, D.; Liu, W.; Herrmann, A.K.; Benad, A.; Eychmüller, A. Function-Led Design of Aerogels: Self-Assembly of Alloyed PdNi Hollow Nanospheres for Efficient Electrocatalysis. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition, 2015, 54. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Herrmann, A.K.; Geiger, D.; Borchardt, L.; Simon, F.; Kaskel, S.; Gaponik, N.; Eychmüller, A. High-Performance Electrocatalysis on Palladium Aerogels. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition, 2012, 51. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Rodriguez, P.; Borchardt, L.; Foelske, A.; Yuan, J.; Herrmann, A.K.; Geiger, D.; Zheng, Z.; Kaskel, S.; Gaponik, N.; et al. Bimetallic Aerogels: High-Performance Electrocatalysts for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition, 2013, 52. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Shi, Q.; Fu, S.; Song, J.; Xia, H.; Du, D.; Lin, Y. Efficient Synthesis of MCu (M = Pd, Pt, and Au) Aerogels with Accelerated Gelation Kinetics and Their High Electrocatalytic Activity. Advanced Materials 2016, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Zhu, C.; Du, D.; Bi, C.; Xia, H.; Feng, S.; Engelhard, M.H.; Lin, Y. Kinetically Controlled Synthesis of AuPt Bi-Metallic Aerogels and Their Enhanced Electrocatalytic Performances. J Mater Chem A Mater 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyce, G.W.; Hayes, J.R.; Hamza, A. V.; Satcher, J.H. Synthesis and Characterization of Hierarchical Porous Gold Materials. Chemistry of Materials 2007, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlebacher, J.; Aziz, M.J.; Karma, A.; Dimitrov, N.; Sieradzki, K. Evolution of Nanoporosity in Dealloying. Nature 2001, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielasek, V.; Jürgens, B.; Schulz, C.; Biener, J.; Biener, M.M.; Hamza, A. V.; Bäumer, M. Gold Catalysts: Nanoporous Gold Foams. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition, 2006, 45. [CrossRef]

- Hodge, A.M.; Hayes, J.R.; Caro, J.A.; Biener, J.; Hamza, A. V. Characterization and Mechanical Behavior of Nanoporous Gold. Adv Eng Mater 2006, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biener, J.; Wittstock, A.; Zepeda-Ruiz, L.A.; Biener, M.M.; Zielasek, V.; Kramer, D.; Viswanath, R.N.; Weissmüller, J.; Bäumer, M.; Hamza, A. V. Surface-Chemistry-Driven Actuation in Nanoporous Gold. Nat Mater 2009, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, L.; Farghaly, A.A.; Esteves, R.J.A.; Arachchige, I.U. Shape Controlled Synthesis of Au/Ag/Pd Nanoalloys and Their Oxidation-Induced Self-Assembly into Electrocatalytically Active Aerogel Monoliths. Chemistry of Materials 2017, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce C, T.; Stephen A, S.; Luther, E.P. Nanoporous Metal Foams. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition, 2010, 49.

- Tappan, B.C.; Huynh, M.H.; Hiskey, M.A.; Chavez, D.E.; Luther, E.P.; Mang, J.T.; Son, S.F. Ultralow-Density Nanostructured Metal Foams: Combustion Synthesis, Morphology, and Composition. J Am Chem Soc 2006, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotiropoulou, S.; Sierra-Sastre, Y.; Mark, S.S.; Batt, C.A. Biotemplated Nanostructured Materials. Chemistry of Materials 2008, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.X.; Chow, S.K.; Zhang, D. Biomorphic Mineralization: From Biology to Materials. Prog Mater Sci 2009, 54, 542–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Hu, Y.; Hübner, R.; Joswig, J.O.; Fan, X.; Schneider, K.; Eychmüller, A. Specific Ion Effects Directed Noble Metal Aerogels: Versatile Manipulation for Electrocatalysis and Beyond. Sci Adv 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burpo, F.J.; Nagelli, E.A.; Losch, A.R.; Bui, J.K.; Forcherio, G.T.; Baker, D.R.; McClure, J.P.; Bartolucci, S.F.; Chu, D.D. Salt-Templated Platinum-Copper Porous Macrobeams for Ethanol Oxidation. Catalysts 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burpo, F.J.; Nagelli, E.A.; Mitropoulos, A.N.; Bartolucci, S.F.; McClure, J.P.; Baker, D.R.; Losch, A.R.; Chu, D.D. Saltlated Platinum-Palladium Porous Macrobeam Synthesis. MRS Commun 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burpo, F.J.; Nagelli, E.A.; Morris, L.A.; Woronowicz, K.; Mitropoulos, A.N. Salt-Mediated Au-Cu Nanofoam and Au-Cu-Pd Porous Macrobeam Synthesis. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burpo, F.J.; Nagelli, E.A.; Winter, S.J.; McClure, J.P.; Bartolucci, S.F.; Burns, A.R.; O’Brien, S.F.; Chu, D.D. Salt-Templated Hierarchically Porous Platinum Macrotube Synthesis. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talapin, D. V. Lego Materials. ACS Nano 2008, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiligtag, F.J.; Airaghi Leccardi, M.J.I.; Erdem, D.; Süess, M.J.; Niederberger, M. Anisotropically Structured Magnetic Aerogel Monoliths. Nanoscale 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rechberger, F.; Heiligtag, F.J.; Süess, M.J.; Niederberger, M. Assembly of BaTiO3 Nanocrystals into Macroscopic Aerogel Monoliths with High Surface Area. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition, 2014, 53. [CrossRef]

- Mohanan, J.L.; Arachchige, I.U.; Brock, S.L. Porous Semiconductor Chalcogenide Aerogels. Science (1979) 2005, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, A.C.; Pajonk, G.M. Chemistry of Aerogels and Their Applications. Chem Rev 2002, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiligtag, F.J.; Rossell, M.D.; Süess, M.J.; Niederberger, M. Template-Free Co-Assembly of Preformed Au and TiO2 Nanoparticles into Multicomponent 3D Aerogels. J Mater Chem 2011, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechberger, F.; Ilari, G.; Niederberger, M. Assembly of Antimony Doped Tin Oxide Nanocrystals into Conducting Macroscopic Aerogel Monoliths. Chemical Communications 2014, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Shi, N.; Hess, M.; Chen, X.; Cheng, W.; Fan, T.; Niederberger, M. A General Method of Fabricating Flexible Spinel-Type Oxide/Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite Aerogels as Advanced Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Nano 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederberger, M. Nonaqueous Sol-Gel Routes to Metal Oxide Nanoparticles. Acc Chem Res 2007, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, M.; Tang, H.; Wu, M.; Ouyang, C.; Hong, Z.; Wu, N. Synthesis and Photocatalysis of Metal Oxide Aerogels: A Review. Energy and Fuels 2022, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danks, A.E.; Hall, S.R.; Schnepp, Z. The Evolution of “sol-Gel” Chemistry as a Technique for Materials Synthesis. Mater Horiz 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Chen, Y.C.; Feldmann, C. Polyol Synthesis of Nanoparticles: Status and Options Regarding Metals, Oxides, Chalcogenides, and Non-Metal Elements. Green Chemistry 2015, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mello Donegá, C.; Liljeroth, P.; Vanmaekelbergh, D. Physicochemical Evaluation of the Hot-Injection Method, a Synthesis Route for Monodisperse Nanocrystals. Small 2005, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Embden, J.; Chesman, A.S.R.; Jasieniak, J.J. The Heat-up Synthesis of Colloidal Nanocrystals. Chemistry of Materials 2015, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamathi, M.; Seshadri, R. Oxide and Chalcogenide Nanoparticles from Hydrothermal/Solvothermal Reactions. Curr Opin Solid State Mater Sci 2002, 6, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiemenz, P.C.; Rajagopalan, R. Principles of Colloid and Surface Chemistry: Third Edition, Revised and Expanded. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.S. Self-Assembly and Nanotechnology: A Force Balance Approach; 2007. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S. A: and Nanotechnology, 2007.

- Gaponik, N.; Wolf, A.; Marx, R.; Lesnyak, V.; Schilling, K.; Eychmüller, A. Three-Dimensional Self-Assembly of Thiol-Capped CdTe Nanocrystals: Gels and Aerogels as Building Blocks for Nanotechnology. Advanced Materials 2008, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayase, G.; Nonomura, K.; Hasegawa, G.; Kanamori, K.; Nakanishi, K. Ultralow-Density, Transparent, Superamphiphobic Boehmite Nanofiber Aerogels and Their Alumina Derivatives. Chemistry of Materials 2015, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewis, J.; Wagner, N.J. Colloidal Suspension Rheology; 2011; Vol. 978052151 5993.

- Dawson, K.A. The Glass Paradigm for Colloidal Glasses, Gels, and Other Arrested States Driven by Attractive Interactions. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci 2002, 7, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E. On Gelation Kinetics in a System of Particles with Both Weak and Strong Interactions. Journal of the Chemical Society - Faraday Transactions. [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.J.; Zaccarelli, E.; Ciulla, F.; Schofield, A.B.; Sciortino, F.; Weitz, D.A. Gelation of Particles with Short-Range Attraction. Nature 2008, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Gao, H.; Chen, X.; Chen, D.; Lv, J.; Han, M.; Cheng, P.; Wang, G. In Situ One-Step Construction of Monolithic Silica Aerogel-Based Composite Phase Change Materials for Thermal Protection. Compos B Eng 2020, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Sheikh, J.; Behera, B.K. Aerogel Composites and Blankets with Embedded Fibrous Material by Ambient Drying: Reviewing Their Production, Characteristics, and Potential Applications. Drying Technology 2023, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Du, H.; Zheng, T.; Liu, K.; Ji, X.; Xu, T.; Zhang, X.; Si, C. Cellulose Based Composite Foams and Aerogels for Advanced Energy Storage Devices. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handbook of Sol-Gel Science and Technology: Processing, Characterization and Applications, Volumes I−III Set Edited by Sumio Sakka (Professor Emeritus of Kyoto University). Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, Dordrecht, London. 2005. Lx + 1980 Pp. $1500.00. ISBN 1-4020-7969-9. J Am Chem Soc, 2005, 127. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, S.; Sheikh, J.N. Silica Centered Aerogels as Advanced Functional Material and Their Applications: A Review. J Non Cryst Solids 2023, 611, 122322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, H.; Durães, L.; García-González, C.A.; del Gaudio, P.; Portugal, A.; Mahmoudi, M. Synthesis and Biomedical Applications of Aerogels: Possibilities and Challenges. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2016, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hüsing, N.; Schubert, U. Aerogels—Airy Materials: Chemistry, Structure, and Properties. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 1998, 37, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, A.; Diéguez, S.; Diaz-Gomez, L.; Gómez-Amoza, J.L.; Magariños, B.; Concheiro, A.; Domingo, C.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; García-González, C.A. Synthetic Scaffolds with Full Pore Interconnectivity for Bone Regeneration Prepared by Supercritical Foaming Using Advanced Biofunctional Plasticizers. Biofabrication 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firoozi, A.A.; Firoozi, A.A.; El-Abbasy, A.A.; Aati, K. Enhanced Perspectives on Silica Aerogels: Novel Synthesis Methods and Emerging Engineering Applications. Results in Engineering 2025, 25, 103615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, S.; Navik, R.; Ding, X.; Zhao, Y. Improved Heat Insulation and Mechanical Properties of Silica Aerogel/Glass Fiber Composite by Impregnating Silica Gel. J Non Cryst Solids, 2019, 503–504, 78–83. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Ji, H.; Sun, X.; He, J. Effect of Sepiolite Fiber on the Structure and Properties of the Sepiolite/Silica Aerogel Composite. J Solgel Sci Technol 2013, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Sun, Y.; Feng, J.; Yang, X.; Han, S.; Mi, C.; Jiang, Y.; Qi, H. Experimental Investigation on High Temperature Anisotropic Compression Properties of Ceramic-Fiber-Reinforced SiO2 Aerogel. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2013, 585, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ren, H.; Zhu, J.; Bi, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, L. Facile Fabrication of Superhydrophobic, Mechanically Strong Multifunctional Silica-Based Aerogels at Benign Temperature. J Non Cryst Solids 2017, 473, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamy-Mendes, A.; Malfait, W.J.; Sadeghpour, A.; Girão, A. V.; Silva, R.F.; Durães, L. Influence of 1D and 2D Carbon Nanostructures in Silica-Based Aerogels. Carbon N Y 2021, 180, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Luigi, M.; An, L.; Armstrong, J.N.; Ren, S. Scalable and Robust Silica Aerogel Materials from Ambient Pressure Drying. Mater Adv 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C.M.R.; Ghica, M.E.; Ramalho, A.L.; Durães, L. Silica-Based Aerogel Composites Reinforced with Different Aramid Fibres for Thermal Insulation in Space Environments. J Mater Sci 2021, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zou, L.; Zu, G.; Chen, D.; Shen, J. Opacifier Embedded and Fiber Reinforced Alumina-Based Aerogel Composites for Ultra-High Temperature Thermal Insulation. Ceram Int 2019, 45, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demilecamps, A.; Beauger, C.; Hildenbrand, C.; Rigacci, A.; Budtova, T. Cellulose–Silica Aerogels. Carbohydr Polym 2015, 122, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahbakhsh, A.; Bahramian, A.R. Self-Assembled and Pyrolyzed Carbon Aerogels: An Overview of Their Preparation Mechanisms, Properties and Applications. Nanoscale 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, H.; Durães, L.; Portugal, A. An Overview on Silica Aerogels Synthesis and Different Mechanical Reinforcing Strategies. J Non Cryst Solids 2014, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardecchia, S.; Carriazo, D.; Ferrer, M.L.; Gutiérrez, M.C.; Monte, F. Del Three Dimensional Macroporous Architectures and Aerogels Built of Carbon Nanotubes and/or Graphene: Synthesis and Applications. Chem Soc Rev 2013, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdusalamov, R.; Scherdel, C.; Itskov, M.; Milow, B.; Reichenauer, G.; Rege, A. Modeling and Simulation of the Aggregation and the Structural and Mechanical Properties of Silica Aerogels. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2021, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Niu, M.; Li, M.; Lu, D.; Guo, P.; Zhuang, L.; Peng, K.; Wang, H. Engineering the Mechanical Properties of Resilient Ceramic Aerogels. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2024, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, F.; Pinjaro, M.A.; Ahmed, J.; Ahmed, M.; Arain, H.J.; Ahsan, M.J.; Sanjrani, I.A. Recent Advances and Synthesis Approaches for Enhanced Heavy Metal Adsorption from Wastewater by Silica-Based and Nanocellulose-Based 3D Structured Aerogels: A State of the Art Review with Adsorption Mechanisms and Prospects. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doke, S.D.; Patel, C.M.; Lad, V.N. Improving Physical Properties of Silica Aerogel Using Compatible Additives. Chemical Papers 2021, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Cano, R.; González-López, J.R.; Guerra-Cossío, M.A. Effects on the Mechanical and Thermal Behaviors of an Alternative Mortar When Adding Modified Silica Aerogel with Aminopropyl Triethoxysilane and PEG-PPG-PEG Triblock Copolymer Additives. Silicon 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.X.; Hendrix, Y.; Schollbach, K.; Brouwers, H.J.H. A Silica Aerogel Synthesized from Olivine and Its Application as a Photocatalytic Support. Constr Build Mater 2020, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaraman, D.; Zhao, S.; Iswar, S.; Lattuada, M.; Malfait, W.J. Aerogel Spring-Back Correlates with Strain Recovery: Effect of Silica Concentration and Aging. Adv Eng Mater 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hu, M.; Shen, K.; Liu, Q.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, X.; Wu, X. Tuning Thermal Stability and Fire Hazards of Hydrophobic Silica Aerogels via Doping Reduced Graphene Oxide. J Non Cryst Solids 2024, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Mahadik, D.B.; Parale, V.G.; Park, H.H. Composites of Silica Aerogels with Organics: A Review of Synthesis and Mechanical Properties. Journal of the Korean Ceramic Society 2020, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabernero, A.; Baldino, L.; Misol, A.; Cardea, S.; del Valle, E.M.M. Role of Rheological Properties on Physical Chitosan Aerogels Obtained by Supercritical Drying. Carbohydr Polym 2020, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Han, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y. Advances in Multiple Reinforcement Strategies and Applications for Silica Aerogel. J Mater Sci 2023, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.P. Enhanced Mechanical Properties of Double-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Reinforced Silica Aerogels: An All-Atom Simulation Study. Scr Mater 2021, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, N.M.; Mokhtari-Shourijeh, Z.; Langari, S.; Naeimi, A.; Hayati, B.; Jalili, M.; Seifpanahi-Shabani, K. Silica Aerogel/Polyacrylonitrile/Polyvinylidene Fluoride Nanofiber and Its Ability for Treatment of Colored Wastewater. J Mol Struct 2021, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettignano, A.; Aguilera, D.A.; Tanchoux, N.; Bernardi, L.; Quignard, F. Alginate: A Versatile Biopolymer for Functional Advanced Materials for Catalysis. In Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis; 2019; Vol. 178.

- Cao, J.; Tao, J.; Yang, M.; Liu, C.; Yan, C.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhao, H.B.; Rao, W. A Novel Phosphorus-Modified Silica Aerogel for Simultaneously Improvement of Flame Retardancy, Mechanical and Thermal Insulation Properties in Rigid Polyurethane Foam. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.; Yuan, S.; Yang, Y.; Wan, X.; Yang, Y.; Mu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Fan, W.; Liu, T. Freezing-Assisted Direct Ink Writing of Customized Polyimide Aerogels with Controllable Micro- and Macro- Structures for Thermal Insulation. Adv Funct Mater 2025, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, K.; Ji, X.; You, Y.; Zhang, X. Reaction-Spun Transparent Silica Aerogel Fibers. ACS Nano 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Huang, M.; Wang, X.; Sun, Q.; Tang, G.H.; Du, M. Toward Optical Selectivity Aerogels by Plasmonic Nanoparticles Doping. Renew Energy 2022, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhao, B.; Gao, D.; Jiao, D.; Hu, M.; Pei, G. Solar Transparent and Thermally Insulated Silica Aerogel for Efficiency Improvement of Photovoltaic/Thermal Collectors. Carbon Neutrality 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhuo, S.; Zhang, R. Highly Transparent, Temperature-Resistant, and Flexible Polyimide Aerogels for Solar Energy Collection. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.F.; Tang, G.H.; Feng, J.; Jiang, Y.G.; Feng, J.Z. Non-Silica Fiber and Enabled Stratified Fiber Doping for High Temperature Aerogel Insulation. Int J Heat Mass Transf 2020, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Wu, L.; Hao, Y.; Pei, G. Ultrahigh-Efficiency Solar Energy Harvesting via a Non-Concentrating Evacuated Aerogel Flat-Plate Solar Collector. Renew Energy 2022, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled Mohammad, A.; Ghosh, A. Exploring Energy Consumption for Less Energy-Hungry Building in UK Using Advanced Aerogel Window. Solar Energy 2023, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.C.; Potochniak, A.E.; Hyer, A.P.; Ferri, J.K. Zirconia Aerogels for Thermal Management: Review of Synthesis, Processing, and Properties Information Architecture. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2021, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Huang, Q.; Chen, B.; Niu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Long, D. High-Precision 3D Reconstruction and Quantitative Structure Description: Linking Microstructure to Macroscopic Heat Transfer of Aerogels. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 488, 150989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, S.J.; Gupta, H. Emerging Applications of Aerogels in Textiles. Polym Test 2022, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Hu, X.; Liu, L.; Li, M.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Sun, Z. Dimensional Upgrading of 0D Silica Nanospheres to 3D Networking toward Robust Aerogels for Fire Resistance and Low-Carbon Applications. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports 2024, 161, 100842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silviana, S.; Prastiti, E.C.; Hermawan, F.; Setyawan, A. Optimization of the Sound Absorption Coefficient (SAC) from Cellulose-Silica Aerogel Using the Box-Behnken Design. ACS Omega 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budtova, T.; Lokki, T.; Malakooti, S.; Rege, A.; Lu, H.; Milow, B.; Vapaavuori, J.; Vivod, S.L. Acoustic Properties of Aerogels: Current Status and Prospects. Adv Eng Mater 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei Tafreshi, O.; Saadatnia, Z.; Ghaffari-Mosanenzadeh, S.; Rastegardoost, M.M.; Zhang, C.; Park, C.B.; Naguib, H.E. Polyimide Aerogel Fiber Bundles for Extreme Thermal Management Systems in Aerospace Applications. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2024, 16, 54597–54609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, D.; Bai, W.; Geng, M.; Yin, X.; Yu, J.; Zhang, S.; Ding, B. Bubble Templated Flexible Ceramic Nanofiber Aerogels with Cascaded Resonant Cavities for High-Temperature Noise Absorption. ACS Nano 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.; Zhu, Y.; Cheng, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, M. Recent Progress on Organic Aerogels for Sound Absorption. Mater Today Commun 2024, 39, 109243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, Z.; Yang, L.; Ding, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, M.; Wu, Q.; Liu, T. Hierarchically Porous Networks Structure Based on Flexible SiO2 Nanofibrous Aerogel with Excellent Low Frequency Noise Absorption. Ceram Int 2023, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umate, T.B.; Sawarkar, P.D. Thermal Performance Evaluation of Aerogel-Enhanced Polyurethane Insulation Panels for Refrigerated Vehicles: A Numerical and Experimental Study. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress 2024, 53, 102752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, F.; Buratti, C. Properties and Energy Performance of Wood Waste Sustainable Panels Resulting from the Fabrication of Innovative Monolithic Aerogel Glazing Systems. Constr Build Mater 2024, 438, 137310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba Thai, Q.; Ee Siang, T.; Khac Le, D.; Shah, W.A.; Phan-Thien, N.; Duong, H.M. Advanced Fabrication and Multi-Properties of Rubber Aerogels from Car Tire Waste. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2019, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Hu, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, M.; Han, Y.; Huang, S. Sound Absorption Polyimide Composite Aerogels for Ancient Architectures’ Protection. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, W.; Gong, H.; Xu, Q.; Yan, M.; Li, H.; Zhang, D. Hierarchically Piezoelectric Aerogels for Efficient Sound Absorption and Machine-Learning-Assisted Sensing. Adv Funct Mater 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yuan, P.; Ma, B.; Yuan, W.; Luo, J. Hierarchically Structured M13 Phage Aerogel for Enhanced Sound-Absorption. Macromol Mater Eng 2020, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, M. Simple Ultrasonic-Assisted Approach to Prepare Polysaccharide-Based Aerogel for Cell Research and Histocompatibility Study. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.Y.; Li, Z.Y.; Pan, N. Design and Thermal Insulation Performance Analysis of Endothermic Opacifiers Doped Silica Aerogels. International Journal of Thermal Sciences 2019, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Corker, J.; Papathanasiou, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Madyan, O.A.; Liao, F.; Fan, M. Critical Review on the Thermal Conductivity Modelling of Silica Aerogel Composites. Journal of Building Engineering 2022, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzemińska, S.; Greszta, A.; Różański, A.; Safandowska, M.; Okrasa, M. Effects of Heat Exposure on the Properties and Structure of Aerogels for Protective Clothing Applications. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2019, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Tang, G.H.; Si, Q.; Pu, J.H.; Sun, Q.; Du, M. Plasmonic Aerogel Window with Structural Coloration for Energy-Efficient and Sustainable Building Envelopes. Renew Energy 2023, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Shen, J.; Ma, Y.; Liu, L.; Meng, R.; Yao, J. Robust, Sustainable Cellulose Composite Aerogels with Outstanding Flame Retardancy and Thermal Insulation. Carbohydr Polym 2020, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yrieix, B. Architectured Materials in Building Energy Efficiency. In Springer Series in Materials Science; 2019; Vol. 282.

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lei, Q.; Fang, X.; Xie, H.; Yu, W. Tightly-Packed Fluorinated Graphene Aerogel/Polydimethylsiloxane Composite with Excellent Thermal Management Properties. Compos Sci Technol 2022, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Man, J.; Liu, S.; Huang, S.; Lu, J.; Tai, J.; Zhong, Y.; Shen, X.; Cui, S.; Chen, X. Isocyanate-Crosslinked Silica Aerogel Monolith with Low Thermal Conductivity and Much Enhanced Mechanical Properties: Fabrication and Analysis of Forming Mechanisms. Ceram Int 2021, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.C.; Hyer, A.P.; Guo, H.; Ferri, J.K. Silica Aerogel Synthesis/Process-Property Predictions by Machine Learning. Chemistry of Materials 2023, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Huang, Y.; Chen, G.; Feng, M.; Dai, H.; Yuan, B.; Chen, X. Effect of Heat Treatment on Hydrophobic Silica Aerogel. J Hazard Mater 2019, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, C.; Donthula, S.; Soni, R.; Bertino, M.; Sotiriou-Leventis, C.; Leventis, N. Light Scattering and Haze in TMOS-Co-APTES Silica Aerogels. J Solgel Sci Technol 2019, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinzi, M.; Rossi, G.; Anderson, A.M.; Carroll, M.K.; Moretti, E.; Buratti, C. Optical and Visual Experimental Characterization of a Glazing System with Monolithic Silica Aerogel. Solar Energy 2019, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, M.; Liu, S.; Ding, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Hu, N.; Fan, W.; Miao, Y.-E.; Zhang, C.; Liu, T. A Mechanically Robust and Optically Transparent Nanofiber-Aerogel-Reinforcing Polymeric Nanocomposite for Passive Cooling Window. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 498, 154973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, C.; Tang, G.H.; He, C.B.; Yang, X.; Lu, Y. Elastic Modulus Prediction Based on Thermal Conductivity for Silica Aerogels and Fiber Reinforced Composites. Ceram Int 2022, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malfait, W.J.; Ebert, H.P.; Brunner, S.; Wernery, J.; Galmarini, S.; Zhao, S.; Reichenauer, G. The Poor Reliability of Thermal Conductivity Data in the Aerogel Literature: A Call to Action! J Solgel Sci Technol 2024, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Ling, Y. Research Progress of Aerogel Materials in the Field of Construction. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2024, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Liu, B.W.; Zhang, L.; Peng, Z.C.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, H.B.; Wang, Y.Z. Fully Biomass-Based Aerogels with Ultrahigh Mechanical Modulus, Enhanced Flame Retardancy, and Great Thermal Insulation Applications. Compos B Eng 2021, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Dang, B.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, M.; Bi, H.; Sun, D.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Intelligent Designs from Nature: Biomimetic Applications in Wood Technology. Prog Mater Sci 2023, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbakır, Y.; Jonáš, A.; Kiraz, A.; Erkey, C. Application of Aerogels in Optical Devices. In Springer Handbooks; 2023; Vol. Part F1485.

- Rocha, H.; Lafont, U.; Semprimoschnig, C. Environmental Testing and Characterization of Fibre Reinforced Silica Aerogel Materials for Mars Exploration. Acta Astronaut 2019, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshazli, M.T.; Mudaqiq, M.; Xing, T.; Ibrahim, A.; Johnson, B.; Yuan, J. Experimental Study of Using Aerogel Insulation for Residential Buildings. Advances in Building Energy Research 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, R.; Zhang, C.; Liu, C. Photothermal and Energy Performance of an Innovative Roof Based on Silica Aerogel-PCM Glazing Systems. Energy Convers Manag 2022, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lu, L.; Peng, J.; Zheng, D.; Lu, B. Optical Path Model and Energy Performance Optimization of Aerogel Glazing System Filled with Aerogel Granules. Appl Energy 2023, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, L.; Chen, Y.; Lu, B. Investigation on the Optical and Energy Performances of Different Kinds of Monolithic Aerogel Glazing Systems. Appl Energy 2020, 261, 114487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloni, E.; Buratti, C.; Merli, F.; Moretti, E.; Ihara, T. Thermal-Energy and Lighting Performance of Aerogel Glazings with Hollow Silica: Field Experimental Study and Dynamic Simulations. Energy Build 2021, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Kim, D.; Ko, S.H. Recent Progress in High-Efficiency Transparent Vacuum Insulation Technologies for Carbon Neutrality. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing-Green Technology 2024, 11, 1681–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revin, V. V.; Pestov, N.A.; Shchankin, M. V.; Mishkin, V.P.; Platonov, V.I.; Uglanov, D.A. A Study of the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Aerogels Obtained from Bacterial Cellulose. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çok, S.S.; Gizli, N. Hydrophobic Silica Aerogels Synthesized in Ambient Conditions by Preserving the Pore Structure via Two-Step Silylation. Ceram Int 2020, 46, 27789–27799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.; Zolali, A.M.; Jalali, A.; Park, C.B. Strong, Highly Hydrophobic, Transparent, and Super-Insulative Polyorganosiloxane-Based Aerogel. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 413, 127488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.M.; Jensen, K.I. Evacuated Aerogel Glazings. Vacuum 2008, 82, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer, A.; Chen, K.; Tang, A.; Allgeier, A.; Glicksman, L.R.; Gibson, L.J. Thermal Conductivity and Characterization of Compacted, Granular Silica Aerogel. Energy Build 2014, 79, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.N.; Johansson, P.; Sasic Kalagasidis, A. Knowledge Gaps Regarding the Hygrothermal and Long-Term Performance of Aerogel-Based Coating Mortars. Constr Build Mater 2022, 314, 125602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Guo, J.; Guo, Y.; Yang, F.; Ma, Z. CO2 Adsorption Properties of Aerogel and Application Prospects in Low-Carbon Building Materials: A Review. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2024, 20, e03171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantucci, S.; Fenoglio, E.; Grosso, G.; Serra, V.; Perino, M.; Marino, V.; Dutto, M. Development of an Aerogel-Based Thermal Coating for the Energy Retrofit and the Prevention of Condensation Risk in Existing Buildings. Sci Technol Built Environ 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Lv, Y.; Liang, T.; Kong, X.; Mei, H.; Wang, S. Improvement of Aerogel-Incorporated Concrete by Incorporating Polyvinyl Alcohol Fiber: Mechanical Strength and Thermal Insulation. Constr Build Mater 2024, 449, 138422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, A.; Zheng, N.; Zhu, W.; Cao, D.; Wang, W. Innovation and Development of Vacuum Insulation Panels in China: A State-of-the-Art Review. Journal of Building Engineering 2022, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi, Z.; Soltani, P.; Habibi, N.; Latifi, F. Silica Aerogel/Polyester Blankets for Efficient Sound Absorption in Buildings. Constr Build Mater 2019, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroso, M.; Flores-Colen, I.; Silvestre, J.D.; Gomes, M.G.; Hawreen, A.; Ball, R.J. Synergistic Effect of Fibres on the Physical, Mechanical, and Microstructural Properties of Aerogel-Based Thermal Insulating Renders. Cem Concr Compos 2023, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Fang, Z.; Lin, B. Preparation and Optimization of Ultra-Light and Thermal Insulative Aerogel Foam Concrete. Constr Build Mater 2019, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Xue, C.; Guo, W.; Bai, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, Q. Foamed Geopolymer Insulation Materials: Research Progress on Insulation Performance and Durability. J Clean Prod 2024, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantucci, S.; Fenoglio, E.; Serra, V.; Perino, M.; Dutto, M.; Marino, V. Hygrothermal Characterization of High-Performance Aerogel-Based Internal Plaster. In Proceedings of the Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; 2020; Vol. 163. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, P.; Brunner, S.; Zhao, S.; Griffa, M.; Leemann, A.; Toropovs, N.; Malekos, A.; Koebel, M.M.; Lura, P. Study of Physical Properties and Microstructure of Aerogel-Cement Mortars for Improving the Fire Safety of High-Performance Concrete Linings in Tunnels. Cem Concr Compos 2019, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; He, C.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, X.; Richard, Y.K.K. Fire-Resistant and Mechanically-Robust Phosphorus-Doped MoS2/Epoxy Composite as Barrier of the Thermal Runaway Propagation of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 497, 154866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganobjak, M.; Brunner, S.; Wernery, J. Aerogel Materials for Heritage Buildings: Materials, Properties and Case Studies. J Cult Herit 2020, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, J.; Khandel, O.; Sedighardekani, R.; Sahneh, A.R.; Ghahari, S.A. Enhanced Workability, Durability, and Thermal Properties of Cement-Based Composites with Aerogel and Paraffin Coated Recycled Aggregates. J Clean Prod 2021, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Wu, H.; Fu, P.; Liu, Y.; Yang, W. Dynamic Thermal Performance of Ultra-Light and Thermal-Insulative Aerogel Foamed Concrete for Building Energy Efficiency. Solar Energy 2020, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatoi, A.S.; Hashmi, Z.; Mazari, S.A.; Abro, R.; Sabzoi, N. Recent Developments and Progress of Aerogel Assisted Environmental Remediation: A Review. Journal of Porous Materials 2021, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Dong, X.; Gao, G.; Sha, F.; Xu, D. Microstructure and Adsorption Properties of MTMS / TEOS Co-Precursor Silica Aerogels Dried at Ambient Pressure. J Non Cryst Solids 2021, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, J.; Zheng, Y.; Wei, H.; Su, Z. Graphene-Based Hybrid Aerogels for Energy and Environmental Applications. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnyakov, A.Y.; Barnyakov, M.Y.; Bobrovnikov, V.S.; Buzykaev, A.R.; Danilyuk, A.F.; Katcin, A.A.; Kononov, S.A.; Kirilenko, P.S.; Kravchenko, E.A.; Kuyanov, I.A.; et al. Impact of Polishing on the Light Scattering at Aerogel Surface. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res A 2016, 824, 123–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renjith, P.K.; Sarathchandran, C.; Chandramohanakumar, N.; Sekkar, V. Silica Aerogel Composite with Inherent Superparamagnetic Property: A Pragmatic and Ecofriendly Approach for Oil Spill Clean-up under Harsh Conditions. Materials Today Sustainability 2023, 24, 100498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, S.; Albadn, Y.M.; Yahya, E.B.; Nasr, S.; Khalil, H.P.S.A.; Ahmad, M.I.; Kamaruddin, M.A. Trends in Enhancing the Efficiency of Biomass-Based Aerogels for Oil Spill Clean-Up. Giant 2024, 18, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saharan, Y.; Singh, J.; Goyat, R.; Umar, A.; Algadi, H.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Kumar, R.; Baskoutas, S. Nanoporous and Hydrophobic New Chitosan-Silica Blend Aerogels for Enhanced Oil Adsorption Capacity. J Clean Prod 2022, 351, 131247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, L.; Ghaani, M.R.; MacElroy, J.M.D.; English, N.J. A Comprehensive Review on the Application of Aerogels in CO2-Adsorption: Materials and Characterisation. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Sheng, L.; Zhang, T.; Yin, H.; Weng, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, W.; Hu, G.; Hu, H. Analysis and Measurement of Optical Properties and Time Characterization of Silica Aerogel Used as a Cherenkov Radiator. Radiat Meas 2024, 177, 107259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharzheev, Y.N. Use of Silica Aerogels in Cherenkov Counters. Physics of Particles and Nuclei 2008, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, M. Transparent Silica Aerogel Blocks for High-Energy Physics Research. In Springer Handbooks; 2023; Vol. Part F1485.

- Tabata, M.; Adachi, I.; Hatakeyama, Y.; Kawai, H.; Morita, T.; Sumiyoshi, T. Large-Area Silica Aerogel for Use as Cherenkov Radiators with High Refractive Index, Developed by Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Drying. J Supercrit Fluids 2016, 110, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, M.; Allison, P.; Beatty, J.J.; Coutu, S.; Gebhard, M.; Green, N.; Hanna, D.; Kunkler, B.; Lang, M.; McBride, K.; et al. Developing a Silica Aerogel Radiator for the HELIX Ring-Imaging Cherenkov System. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res A 2020, 952, 161879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, C.A.; Sosnik, A.; Kalmár, J.; De Marco, I.; Erkey, C.; Concheiro, A.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C. Aerogels in Drug Delivery: From Design to Application. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 332, 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel-Castro, T.A.; Ibarra-Alonso, M.C.; Oliva, J.; Martínez-Luévanos, A. Porous Aerogel and Core/Shell Nanoparticles for Controlled Drug Delivery: A Review. Materials Science and Engineering C 2019, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wu, H.; Xu, X.; Huang, G.; Xu, T.; Guo, S.; Liang, Y. Numerical and Experimental Study on the Thermal Performance of Aerogel Insulating Panels for Building Energy Efficiency. Renew Energy 2019, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, A.C. Applications of Sol-Gel Processing. In Introduction to Sol-Gel Processing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 597–685. [Google Scholar]

- López-Iglesias, C.; Barros, J.; Ardao, I.; Monteiro, F.J.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Gómez-Amoza, J.L.; García-González, C.A. Vancomycin-Loaded Chitosan Aerogel Particles for Chronic Wound Applications. Carbohydr Polym 2019, 204, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, T.; Chen, S.; Li, J.; Du, J.; Yan, X. A Multifunctional Chitosan Composite Aerogel Based on High Density Amidation for Chronic Wound Healing. Carbohydr Polym 2023, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrashi, M.; Semnani, D.; Talebi, Z.; Dehghan, P.; Maherolnaghsh, M. Comparing the Drug Loading and Release of Silica Aerogel and PVA Nano Fibers. J Non Cryst Solids 2019, 503–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, M.P.; Gonçalves, V.S.S.; Gaspar, F.B.; Nogueira, I.D.; Matias, A.A.; Gurikov, P. Novel Alginate-Chitosan Aerogel Fibres for Potential Wound Healing Applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshita, S.; Zhao, S.; Malfait, W.J.; Koebel, M.M. Chemistry of Chitosan Aerogels: Three-Dimensional Pore Control for Tailored Applications. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition, 2021, 60.

- Phaechamud, T.; Charoenteeraboon, J. Antibacterial Activity and Drug Release of Chitosan Sponge Containing Doxycycline Hyclate. AAPS PharmSciTech 2008, 9, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.R.; Amiji, M.M. Preparation and Characterization of Freeze-Dried Chitosan-Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Hydrogels for Site-Specific Antibiotic Delivery in the Stomach. Pharm Res 1996, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoyneva, V.; Momekova, D.; Kostova, B.; Petrov, P. Stimuli Sensitive Super-Macroporous Cryogels Based on Photo-Crosslinked 2-Hydroxyethylcellulose and Chitosan. Carbohydr Polym 2014, 99, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, C.; Barrett, A.; Poole-Warren, L.A.; Foster, N.R.; Dehghani, F. The Development of a Dense Gas Solvent Exchange Process for the Impregnation of Pharmaceuticals into Porous Chitosan. Int J Pharm 2010, 391, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, F.L.; Shyu, S.S.; Chen, C.T.; Lai, J.Y. Adsorption of Indomethacin onto Chemically Modified Chitosan Beads. Polymer (Guildf) 2002, 43, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, R.P.; Sousa, A.M.L.; Silva, A.S.; Paninho, A.I.; Temtem, M.; Costa, E.; Casimiro, T.; Aguiar-Ricardo, A. Design of Experiments Approach on the Preparation of Dry Inhaler Chitosan Composite Formulations by Supercritical CO2-Assisted Spray-Drying. J Supercrit Fluids 2016, 116, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said-Galiev, E.E.; Rubina, M.S.; Naumkin, A. V.; Ikonnikov, N.S.; Vasil’kov, A.Y. Production of a Novel Material Based on a Collagen–Chitosan Composite and Ibuprofen in a Supercritical Medium. Doklady Physical Chemistry 2018, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.V.; Cocarta, A.I.; Dragan, E.S. Synthesis, Characterization and Drug Release Properties of 3D Chitosan/Clinoptilolite Biocomposite Cryogels. Carbohydr Polym 2016, 153, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan-Pragłowska, J.; Piątkowski, M.; Janus, Ł.; Bogdał, D.; Matysek, D. Biodegradable, PH-Responsive Chitosan Aerogels for Biomedical Applications. RSC Adv 2017, 7, 32960–32965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Shou, D.; Lv, O.; Kong, Y.; Deng, L.; Shen, J. PH-Controlled Drug Delivery with Hybrid Aerogel of Chitosan, Carboxymethyl Cellulose and Graphene Oxide as the Carrier. Int J Biol Macromol 2017, 103, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.R.C.; Mano, J.F.; Reis, R.L. Preparation of Chitosan Scaffolds Loaded with Dexamethasone for Tissue Engineering Applications Using Supercritical Fluid Technology. Eur Polym J 2009, 45, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diop, M.; Auberval, N.; Viciglio, A.; Langlois, A.; Bietiger, W.; Mura, C.; Peronet, C.; Bekel, A.; Julien David, D.; Zhao, M.; et al. Design, Characterisation, and Bioefficiency of Insulin–Chitosan Nanoparticles after Stabilisation by Freeze-Drying or Cross-Linking. Int J Pharm 2015, 491, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portero, A.; Teijeiro-Osorio, D.; Alonso, M.J.; Remuñán-López, C. Development of Chitosan Sponges for Buccal Administration of Insulin. Carbohydr Polym 2007, 68, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonaje, K.; Chen, Y.J.; Chen, H.L.; Wey, S.P.; Juang, J.H.; Nguyen, H.N.; Hsu, C.W.; Lin, K.J.; Sung, H.W. Enteric-Coated Capsules Filled with Freeze-Dried Chitosan/Poly(γ-Glutamic Acid) Nanoparticles for Oral Insulin Delivery. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 3384–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, E.S.; Cocarta, A.I.; Gierszewska, M. Designing Novel Macroporous Composite Hydrogels Based on Methacrylic Acid Copolymers and Chitosan and in Vitro Assessment of Lysozyme Controlled Delivery. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2016, 139, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro-León, F.J.; Argüelles-Monal, W.; Carvajal-Millán, E.; López-Franco, Y.L.; Goycoolea-Valencia, F.M.; San Román del Barrio, J.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J. Production and Characterization of Supercritical CO2 Dried Chitosan Nanoparticles as Novel Carrier Device. Carbohydr Polym 2018, 198, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayensu, I.; Mitchell, J.C.; Boateng, J.S. In Vitro Characterisation of Chitosan Based Xerogels for Potential Buccal Delivery of Proteins. Carbohydr Polym 2012, 89, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihara, D.; Hattori, N.; Horimasu, Y.; Masuda, T.; Nakashima, T.; Senoo, T.; Iwamoto, H.; Fujitaka, K.; Okamoto, H.; Kohno, N. Histological Quantification of Gene Silencing by Intratracheal Administration of Dry Powdered Small-Interfering RNA/Chitosan Complexes in the Murine Lung. Pharm Res 2015, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverchon, E.; Antonacci, A. Chitosan Microparticles Production by Supercritical Fluid Processing. Ind Eng Chem Res 2006, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.E.; Suh, D.H.; Yun, Y.P.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, K.; Chung, J.Y.; Lee, D.W. Local Delivery of Alendronate Eluting Chitosan Scaffold Can Effectively Increase Osteoblast Functions and Inhibit Osteoclast Differentiation. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2012, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirviö, J.A.; Kantola, A.M.; Komulainen, S.; Filonenko, S. Aqueous Modification of Chitosan with Itaconic Acid to Produce Strong Oxygen Barrier Film. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoreishi, S.M.; Hedayati, A.; Kordnejad, M. Micronization of Chitosan via Rapid Expansion of Supercritical Solution. J Supercrit Fluids 2016, 111, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Tran, T.T.; Teo, J.; Hadinoto, K. Dry Powder Aerosols of Curcumin-Chitosan Nanoparticle Complex Prepared by Spray Freeze Drying and Their Antimicrobial Efficacy against Common Respiratory Bacterial Pathogens. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2016, 504, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, T.; Parmar, R.; Tyagi, R.K.; Butani, S. Rifampicin Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticle Dry Powder Presents an Improved Therapeutic Approach for Alveolar Tuberculosis. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2017, 154, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaidat, R.M.; Tashtoush, B.M.; Bayan, M.F.; T. Al Bustami, R.; Alnaief, M. Drying Using Supercritical Fluid Technology as a Potential Method for Preparation of Chitosan Aerogel Microparticles. 2015, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, K.; Sowasod, N.; Tanthapanichakoon, W.; Charinpanitkul, T. Hydrogel Based Oil Encapsulation for Controlled Release of Curcumin Byusing a Ternary System of Chitosan, Kappa-Carrageenan, and Carboxymethylcellulose Sodium Salt. LWT 2013, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnátová, M.; Bakoš, D.; Černáková, L.; Michliková, M. Chitosan Sponge Matrices with β-Cyclodextrin for Berberine Loadinging. In Proceedings of the Chemical Papers; 2016; Vol. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Peniche, H.; Reyes-Ortega, F.; Aguilar, M.R.; Rodríguez, G.; Abradelo, C.; García-Fernández, L.; Peniche, C.; Román, J.S. Thermosensitive Macroporous Cryogels Functionalized with Bioactive Chitosan/Bemiparin Nanoparticles. Macromol Biosci 2013, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Gu, Z.; Yu, X. Controlled Drug Release from a Novel Drug Carrier of Calcium Polyphosphate/Chitosan/Aldehyde Alginate Scaffolds Containing Chitosan Microspheres. RSC Adv 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Maheswari, P.U.; Sheriffa Begum, K.M.M.; Arthanareeswaran, G. Biomass-Derived Dialdehyde Cellulose Cross-Linked Chitosan-Based Nanocomposite Hydrogel with Phytosynthesized Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles for Enhanced Curcumin Delivery and Bioactivity. J Agric Food Chem 2019, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athamneh, T.; Amin, A.; Benke, E.; Ambrus, R.; Leopold, C.S.; Gurikov, P.; Smirnova, I. Alginate and Hybrid Alginate-Hyaluronic Acid Aerogel Microspheres as Potential Carrier for Pulmonary Drug Delivery. J Supercrit Fluids 2019, 150, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athamneh, T.; Amin, A.; Benke, E.; Ambrus, R.; Gurikov, P.; Smirnova, I.; Leopold, C.S. Pulmonary Drug Delivery with Aerogels: Engineering of Alginate and Alginate–Hyaluronic Acid Microspheres. Pharm Dev Technol 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, A.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, J. A Special Material or a New State of Matter: A Review and Reconsideration of the Aerogel. Materials 2013, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]