Introduction

The looming challenges of climate change not only threaten food security & safety of the world but are a quagmire for continuously evolving pathogen populations and management strategies. Under favorable conditions crop pests (including plant diseases) may cause losses up to 50 % depending upon the agroecology [

1]. Fungal plant diseases have remained in focus for their devastating effects on crops starting from the infamous Irish famine (1845), in which the fungal phytopathogen,

Phytophthora infestans, causing late blight disease, destroyed the potato crop leading to over 2 million deaths due to starvation and mass migration of people from Ireland. Similarly, Bengal Famine (owing to loss of rice crop by brown spot disease cause by

Helminthosporium oryzae) in 1943 in British India resulted in death of more than 3 million people [

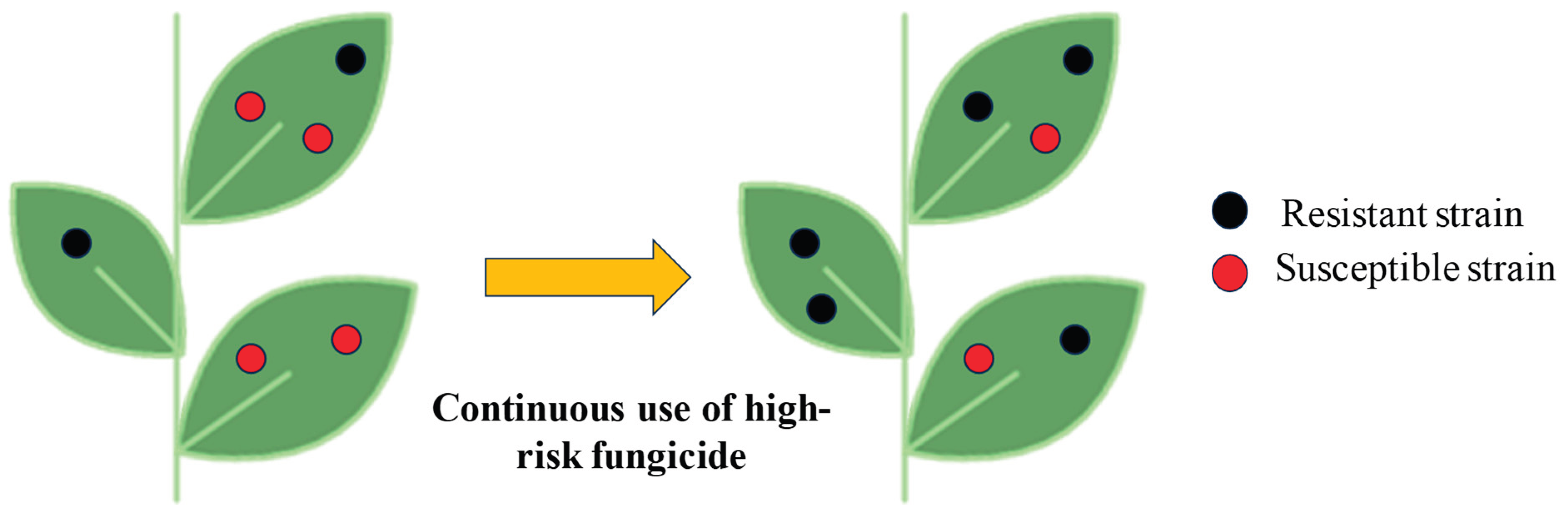

2]. Along with pre-harvest crop losses due to diseases caused by fungal pathogens threatening food security, pre/postharvest contamination of the produce with mycotoxins is another challenge to food safety being presented by fungi. To manage fungal plant pathogens search of antimycotic substances has surpassed many milestones starting from use of saline to identification of sulphur as an antifungal agent. Armed race between ‘killer and killing agent’ led to discovery of Bordeaux mixture, contact fungicides and systemic fungicides to meet the challenges of evolving pathogen population. To manage fungal phytopathogens, antimycotic compounds including benzimidazoles, phenylamides, dicarboximides, anilinopyrimidines, quinone outside inhibitors (QoIs) and carboxylic acid amides (CAAs) are employed in recent times. Lately, it is observed that chemicals employed for management of fungal plant pathogens are losing efficacy quickly due to rapid evolution in pathogen populations and other anthropogenic factors. When fungi are exposed to a certain fungicidal molecule over a period of time (

Figure 1), they tend to develop resistance to these chemical agents [

3]. Fungicide resistance in plant pathogens can render several effective molecules ineffective to manage them leading to significant reduction in crop yields. When fungi develop resistance to fungicides, the application become less effective, leading to increased disease severity and ultimately, lower yields coupled with reduced quality of the produce. This issue is exacerbated by the fact that such resistance can lead to the development of more aggressive and virulent strains of plant pathogenic fungi. Such virulent pathogens will cause diseases which will be difficult to manage and therefore, will severely impact income of the farmers due to increased cost of cultivation coupled with reduced yields and resultant income.

Investigations on development of fungicide resistance is gaining importance in modern agriculture and disease management, as pathogenic fungi evolve to withstand the chemical challenges designed to manage them. Compared to fungicides with multiple sites of action like Cu and S, molecules with one site of action are more prone to development of resistance as more selection pressure is there on it. Antifungal agents may (1) inhibit the synthesis of ergosterol (the main fungal sterol) i.e. azoles; (2) may interact with fungal membrane sterols physico-chemically; and 5-fluorocytosine i.e. polyenes; (3) inhibit macromolecular synthesis [

4]. Due to selection pressure on these sites of action propagules which can withstand the fungicide not only survive but also proliferate and increase in number making the fungicide ineffective under field conditions with time, challenging the chemical management of the pathogen. The development of resistance is influenced by several factors, including the genetic variability of fungal populations, the mode of action of the fungicide, application frequency, and environmental conditions. Strategies to mitigate resistance – such as rotating fungicides with different modes of action, integrating cultural and biological controls, and employing precision application techniques—are essential to prolong the effectiveness of existing fungicides.

Azole group of fungicides were first introduced in 1958 as topical antifungal agent, chlormidazole in medicine, but azole fungicides were first used in agriculture as imazalil and triadimefon during 1970s. At present, many azole derivatives are employed in agriculture like prothioconazole, for management of Mycosphaerella graminicola. Triazoles are the most commonly used class of systemic fungicides. Azole group of fungicides work by targeting the sterol 14α-demethylase, CYP51 (a member of the cytochrome P450 family), which is an important regulatory enzyme in the ergosterol biosyntheis pathway. Azole fungicides bind through direct coordination of the triazole N-4 or the imidazole N-3 nitrogen as the sixth ligand of the haem iron. Understanding the mechanisms and dynamics of fungicide resistance is critical for developing sustainable disease management practices and ensuring long-term agricultural productivity. This review explores the mechanisms, evolution, and management strategies for azole fungicide resistance in plant pathogens.

Historical Perspective of Fungicide Resistances

Charles Darwin’s “On the origin of Species” mentioned for the first time resistance development in microbes [

5]. He mentioned that natural selection brought variation in pathogen population which was more successfully thriving in existing hostile environment. Emergence of variation turned whole population from sensitive to resistant as resistant mutant population replaced sensitive one under the influence of external hostile environment of fungicide application. This was an apparent evolutionary shift that was imperative for the survival of fungus [

6].

For over 200 years, farmers have been using chemicals to reduce fungal attack in fruit crops. Tillet (1755) showed that aqueous brine solution (solution of NaCl) could be used to control infection of bunt fungus (

Tilletia caries) in wheat seed [

7]. Later on, copper sulfate solution was used for fungal disease management with better results [

8] resulting in widespread application of copper formulations. In 1913, efficacy of copper sulfate solution was superseded by organo-mercurial compound for seed treatment [

9]. During 19

th century fruit and foliage were greatly devastated by powdery mildew disease, Forsyth (1802) was the first one to recommended spray of sulphur in order to reduce the damage caused by the disease [

10]. Spray sulphur was found ineffective against several disease like downy mildew of grape (

Plasmopara viticola), late blight of potato (

Phytophthora infestans) etc. Discovery of Bordeaux mixture [

11] which was quite effective against various fungal diseases popularized among large number of farming communities.

In later days, organic compounds-based fungicides were introduced like dithiocarbamates (e.g. thiram, maneb, mancozeb etc.) in 1940s followed by pthalimides (e.g. captan, captafol) in 1950s and chlorothalonil in 1960s. These compounds were comparatively more effective against several diseases with reduced phytotoxicity unlike previous compounds. These compounds formed protective layers on plants’ surface to act against contacting plant pathogens. These compounds had limited penetration ability and could not get intoplant beyond its surface which restricts their efficacy against deep-seated pathogens and established infections. Apart from this, these compounds also wither away, therefore repeated sprays were required. Systemic fungicides held the promise of penetrating deep inside to plant surface in addition to spread in whole plant system which in turn eradicates infection from any plant part [

12]. Griseofulvin (antifungal antibiotic obtained from

Penicillium griseofulvum) had the property to translocate across the plant parts and reported to be effective against wide range of pathogens [

13]. The efficacy of Griseofulvin was at par the existing fungicides as well as it was incurring high-cost rendering Griseofulvin not economical in plant disease management. Systemic nature of Griseofulvin emerged as a ray of hope that systemic fungicidal action was achievable, leading to widespread research on systemic fungicides in plant disease control.

Ultimately, during the late 1960s, six distinct classes of systemic fungicides, all of which were highly effective against specific diseases, emerged in quick succession: benzimidazoles, oxathiins, amines (morpholines), 2-aminopyrimidines, organophosphorus, and antibiotic rice blast fungicides. The 1970s witnessed the launch of four additional classes of highly active fungicides, each exhibiting varying levels of systemicity: dicarboximides, phenylamides, triazoles, and fosetyl-aluminium. In the last two decades, new classes of fungicides have been introduced, including quinone outside inhibitor (Qol) fungicides, anilinopyrimidines, phenylpyrroles, benzamides, carboxylic acid amides, and novel succinic dehydrogenase inhibitors.

Primary Development and Historical Development

The development of resistance in fungal populations against fungicides was not seen as a serious threat during the early 1960s. Farmers were applying fungicides intensively over many years in vineyards, potato fields, orchards etc., without any signs of resistance development. In those days, an article was published with reports of the failure of diphenyl-impregnated paper wraps in protecting lemons from attack of

Penicillium digitatum [

14]. This problem arose due to the emergence of a new strain of

P. digitatum showing resistance against diphenyl and sodium o-phenylphenate. During 1965, fungicide hexachlorobenzene (an aromatic hydrocarbon) was reported to be ineffective in managing wheat bunt fungus

Tilletia foetida from Australia [

15]. This was followed by another detection of resistance in

Pyrenophora avenae population against organomercurial treatment in Scotland [

16]. These reports received considerable attention, but they did not cause much concern as they were isolated incidents related to fungicides that had been utilized for many years. Development of resistance in

Podosphaera fusca (causing Powdery mildew of Cucurbits) in cucurbits plots of New York, USA raised a major concern [

17] as benzimidazole fungicides were adopted by growers for commercial use for less than two years. In the succession of this report, several other findings were emerged out stating about the resistance development against Benomyl and other benzimidazole fungicides in plant pathogens causing damage in different crops. In the same year, Szkolnik and Gilpatrick (1969) documented the extensive failure of dodine in managing

Venturia inaequalis, the pathogen responsible for apple scab, in orchards located in New York State, USA [

18]. These failures were linked to the discovery of isolates that necessitated two to four times greater concentrations of dodine for 50% inhibition (LD

50) in spore germination assessments. Dodine, a long-chain guanidine fungicide with an uncertain mechanism of action, had been utilized extensively, exclusively, and repetitively for approximately a decade due to its demonstrated excellent protective and curative capabilities. Following these failures, the application of dodine experienced a rapid decline, resulting in significant losses to the famers. Nevertheless, in regions where dodine had been used only sparingly or in conjunction with other fungicides in mixed programs, resistance was not observed even after more than 20 years of application [

19]. Also, in orchard which was away from these commercial orchards reduction in the effectivemess of dodine was not recorded which was indicative of the fact that the area was free of tolerant strains of the pathogenic fungus [

20] Bent et al. (1971) reported numerous cases of failure of efficacy of dimethirimol, 2-aminopyrimidine against powdery mildew fungus of cucurbits all across Holland [

21]. It resulted in immediate withdrawal of dimethirimol application from impacted area. In the early 1970s, rapid emergence of resistance against fungicides in plant pathogen population was soon acknowledged as a major threat to application of systemic fungicides with penetrative and curative action. Subsequently, this report more or less adversely affected application and adoption of new commercially introduced fungicides in plant disease management. In succession of these reports, a series of resistance development against many fungicides were reported by many researchers (

Table 1).

Example of Early Resistance Cases

Eye Spot of Wheat and Cereals

Eye spot pathogens (

Oculimacula yallundae and

O. acuformis causing eyespot disease in wheat and other cereals) are considered as low risk (in terms of resistance development) pathogens owing to their monocyclic nature of disease (completing one life cycle in one season) and asexual mode of reproduction through spores. Preliminary reports in Germany [

35,

36] reflected that Methyl Benzimidazole Carbamtes (MBC) treatments (one or two spray) resulted in emergence of resistant fungal spores in eye spot pathogen population but in lower proportion. Failure of MBC treatment in management of eyespot disease was reported in United Kingdom (UK) during 1981 [

37] where pathogen isolates isolated from diseased plants showed high resistance against Carbendazim and other MBC compounds. Resistant isolates had growth rate and pathogenicity identical to sensitive isolates, implying that resistant isolates had low fitness cost. These resistant isolates displayed cross-resistance properties against other compounds belonging to the MBC class [

38]. MBC fungicides disrupt β-tubulin synthesis, which in turn hinders respiration, leading to the death of the pathogen. Resistant isolates of both the

O. yallundae and

O. acuformis were subjected for PCR amplification of β-tubulin partial sequence. These resistant isolates had identical amino acid sequences involving point mutation (substitution of a single amino acid) at 198, 200 and 240 [

39]. For example, the glutamic acid substitution with alanine at position 198 (E198A) was observed in strains that exhibit high resistance to MBCs, yet these strains showed increased sensitivity to phenylcarbamates. In contrast, substituting phenylalanine with tyrosine at position 200 was associated with resistance to both classes of chemicals. In summary, alterations at position 198 were predominantly found in resistant field isolates, indicating that these modifications, while providing resistance to MBCs, do not significantly affect the functionality of the β-tubulin protein.

Septoria Blotch of Wheat

MBC fungicides had been successfully used for the management of Septoria blotch of wheat (caused by

Zymoseptoria tritici) during mid 1970s with nominal reports of resistance development. Post 1970s period, isolates emerged in pathogen population exhibited resistance against series of MBC compounds

viz., Carbendazim, thiabendazole and thiophanate-methyl. These resistant isolates resulted in poor management of Septoria blotch of wheat during 1984-85 where even five sprays were insufficient to control the disease [

40]. E198A mutation in β-tubulin involve in pathogen population. In France, 85% isolates (collected from 1985 to 2005) showed resistance against carbendazim, leading to failure in the control of Septoria blotch of wheat [

41].

Resistance to Azoles and Lessons from Past Fungicide Failures Vis-À-Vis Azoles

In around 30 phytopathogens (

www.frac.info) resistance was reported against Azole fungicides from 60 different countries all over the world [

42]. Emergence of resistance was often observed in plant pathogens with profuse sporulation and short generation time [

43]. In fact, resistance emerged in the ‘high-risk’ cereal powdery mildews (

Blumeria graminis) within four years following the introduction of the azoles triadimefon and triadimenol in the late 1970s [

44]. Notwithstanding this, various azoles (for instance, Prothiconazole) still offer moderate to effective control of powdery mildew, reflecting the presence of incomplete cross-resistance [

45]. The resistance development in phytopathogens causing diseases of economic importance, where Azole fungicides were widely adopted for management, poses a serious concern. The issues arising from resistance among phytopathogens to fungicides are increasing day by day to underline a dire need of anti-resistance strategies. These strategies are as follows:

Dosage: A unanimous consensus is yet to be achieved regarding effect of dosage on fungicide resistance development. Theoretically, it is assumed that high doses reduce population size which in turn, minimize the probability of emergence of resistance [

46]. However, sublethal dose induced stress-mutagenesis leading to high risk of resistance development [

47].

The bulk of experimental data, encompassing field studies, indicate that elevated doses of fungicides enhance the selection for resistance [

48,

49]. The available experimental evidence primarily pertains to the selection phase, focusing on tracking established mutations, rather than addressing the initial emergence of resistance mutations [

50]. A study of the rate of emergence and dissemination of resistance across various regions and nations reveals that the evolution of resistance has advanced more rapidly in areas where elevated fungicide rates are utilized [

51,

52]. Although, the selection of dose rate for each application continues to be a subject of debate in the management of fungicide resistance, the recommendation to reduce the total number of applications of a fungicide that is at risk (while still ensuring effective disease control) is generally accepted and is backed by data from both field and modeling reports. This paved the way for improved understanding regarding pathogen life history traits which further determine that high or low dose rates suits for improved management of both major and polygenic resistance in individual fungal pathogen [

52].

Timing: Application of fungicides as a prophylactic or protectant prevents the onset of infection. After establishment of infection, fungicides are applied as a curative treatment. Unnecessary application of fungicide can be minimized by its application only when a disease is detected or when a specific damage threshold has been met. This approach implies that when treatments are required, they will be administered at a curative stage rather than a preventative one. Application of fungicides as a curative treatment may adversely affect disease and resistance management [

53,

54,

55]. FRAC guidelines advised to avoid curative application as much as possible [

27]. In curative application, higher dose is applied in order to reduce the disease [

54,

56] which exerts high selection pressure on pathogen population. As established infection has large population size which increases the probability of development of resistant strains ([

48,

58,

49,

57].In the context of azole fungicides, rising resistance levels are eliminating the possibility of curative treatment. Long-term monitoring indicates a more pronounced decrease in curative efficacy compared to the protective efficacy of azoles against

Z. tritici, as less-sensitive genotypes become more prevalent in the population [

54].

Mixture or alternations: In order to avoid resistance development in plant pathogens against fungicides one should refrain from applying fungicide with single mode of action. Moreover, either applies mixture of fungicides with two or more distinct mode of action or alternation in application. The application of mixture provides dual advantages for managing resistance. Firstly, when strains that are resistant to one mode of action are susceptible to the other, the disparity in growth rates between resistant and susceptible strains diminishes, thereby reducing the selection pressure for resistance. Secondly, the application rate of each component in the mixture can be lowered without compromising treatment efficacy [

57,

58,

59,

60]. In addition to this if level of resistance in pathogen population is high against one fungicide then mixture offers insurance against crop loss to some extent [

61]. Introducing alternations as supplementary applications interspersed with an unchanged quantity of sprays of the at-risk mode of action will not diminish the selection for resistant strains, provided there is no overlap in the efficacy duration of each spray. This is due to the absence of any alteration in the disparity between the growth rates of resistant and sensitive strains during the timeframe in which the at-risk mode of action is applying selection [

57,

58,

59,

60]. The alternation of fungicides limits the population in small size which in turn reduces the competition among strains resulting in lesser chances of development of resistance.

Effectiveness of mixture or alternation of fungicides (having distinct mode of action) in plant disease management with reduced probability of resistance development varies among the pathogens. In case of mixtures high risk fungicides have to split across several applications which in turn increase exposure time, then alternation proved to be more effective ([

48,

49,

57,

58]. In mixture, both mixing chemicals may be multisite or single site. A multisite chemical has less risk to succumb to resistance development in comparison to single site [

62,

63]. In field trials, the use of a combination of the DMI fungicide epoxiconazole and the SDHI fungicide isopyrazam reduced the selection pressure for

Z. tritici resistance to epoxiconazole. However, it did not have the same effect on the selection for resistance to isopyrazam when compared to the individual applications of each component of the mixture [

64]. In these circumstances, dose of each mixing chemical is standardized in such a way that level of disease management offered by both the fungicides is akin (FRAG-UK, 2020).

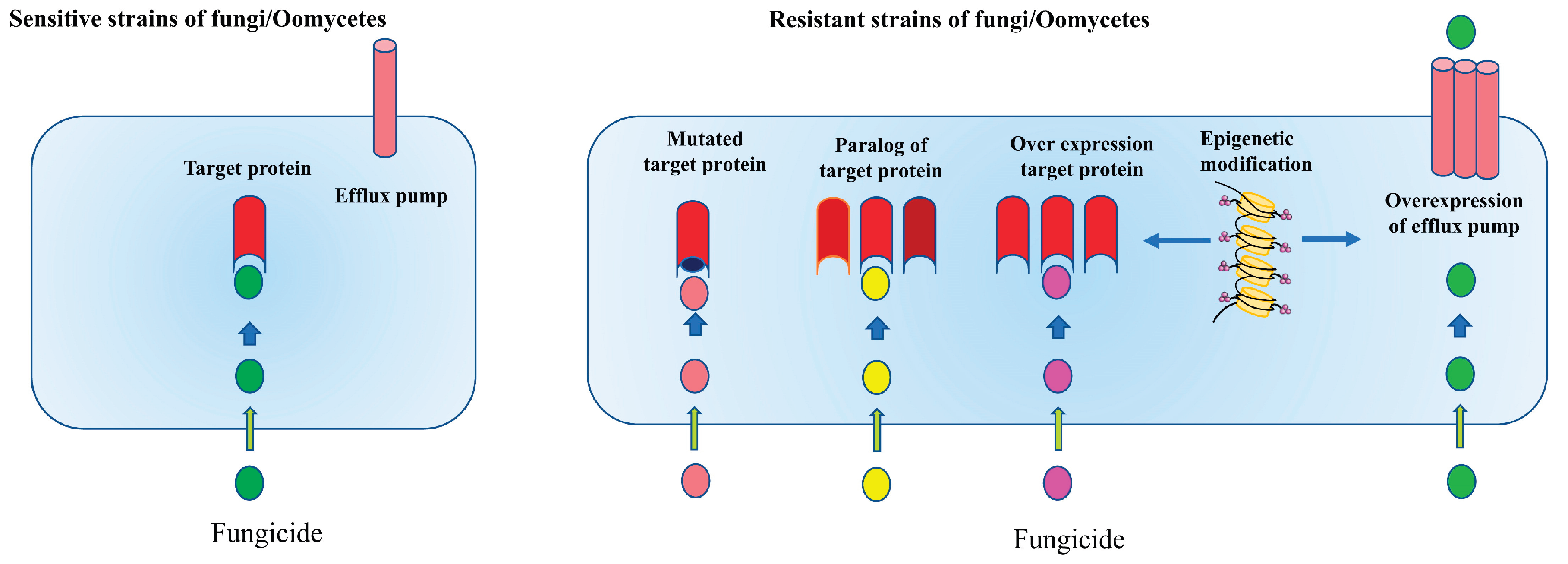

Mechanism of Fungicide Resistance

Various terms like ‘insensitivity’ or ‘tolerance’ are used in place of fungicide resistance but FRAC recommends use of term ‘Resistance’ due to its historical importance as well as usage in related fields of bacteriology and entomology [

65]. Fungicide resistance is defined as “heritable reduction in sensitivity of a chemical of a fungus to specific chemical” [

65,

66]. Development of resistance towards fungicides is an evolutionary process which may have both advantages and disadvantages for pathogen population. Over the time the resistant populations increase in number compared to the fungicide susceptible population which increases their fitness towards survival. To manage fungicide resistance effectively it is essential to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying such processes. Yin et al., (2023) lists some common molecular mechanism of fungicide registers which are which are shown in

Figure 2 [

65].

Further, fungicides resistance in plant pathogens against various fungicides is can be categorized into qualitative or quantitative resistance as described below.

Qualitative resistance: monogenic and mutation is the prime factor in the development of qualitative resistance. UV irradiation primarily introduces mutation in non-pigmented airborne fungal spores like powdery mildew fungi. Genetic mutation in the amino acid encoding gene changes the amino acid, which in turn alters the amino acid receptor required for binding of the fungicide molecule on the pathogen cell. As a result, fungal cell escapes the binding of fungicide molecules, failing fungicide to disrupt vital fungal metabolic process and death of fungus [

67,

68]. For instance, benzimidazole resistance was observed in several plant disease causing fungal pathogens where mutation was detected at codon 6, 50, 163, 167, 198, 200, 240 and 351 in β-tubulin gene [

69]. Apart from this, double mutation of E198A & F167Y, E198A & M163I, E198A & F200S were detected in the fungal population of

Corynespora cassiicola (causing Target leaf spot in cucumber) [

70]. In such cases, even a very high concentration of fungicide does not affect the resistant population. Future fungicide applications replace the entire sensitive wild type with resistant mutant strains. These mutations in fungal populations are inheritable and displayed by the progeny in the presence of particular fungicides [

71].

Quantitative resistance: On the contrary, it is defined by minor, gradual changes in pathogen population. It involves polygenic mutation in genetic makeup over the period [

68,

72]. Multiple mutations in a gene lead to a gradual loss in efficacy of pathogen control. Small mutation keeps on stacking with a minor impact on disease susceptibility. This indicates that the pathogen population slowly develops resistance, and due to the involvement of mutations in various avirulence genes, this results in polygenic alterations within the pathogen population. In both scenarios, the usual trend is a control method that has a partial yet decreasing effectiveness over several growing seasons, until it ultimately becomes insufficient for proper management in the field.

Fungi display this form of resistance by maintaining a low concentration of fungicides at the intracellular level. Mechanisms that ensure the intracellular fungicide concentration remains below a critical threshold include the synthesis of efflux transporters that expel drug molecules into the extracellular space, modifications of plasma membranes that lead to decreased fungicide permeability, or the synthesis of enzymes that break down fungicide molecules [

73]. The resistance arose in

Septoria tritici (causing septoria blotch of wheat) against succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors and azole fungicides were quantitative [

74,

75]. CYP51 enzymes are involved in multiple mutations and render quantitative resistance against azole fungicides [

76,

77]. From past several reports, it has been evident that qualitative (monogenic mutation-driven fungicide resistance) significantly impacts the efficacy of a fungicide in agricultural field and quantitative resistance (polygenic mutation driven fungicide resistance) is of minor significance in agriculture, though holds considerable importance in medicine.

Types of Resistance Mechanism

Target site resistance: A fungicide binds at a specific target site recognized by a specific enzyme followed by disruption of vital biochemical pathways leading to the death of the fungus. Alteration in target site fails fungicide to bind to its receptor enzyme rendering it incapable to cause toxic effect. Resistance to azole compounds arises from alterations in the genes responsible for encoding 14-α-demethylase, which is the target of azole fungicides (cyp51 in molds and erg11 in yeast). Numerous Plant Pathogenic Fungi, including

Penicillium digitatum,

Cercospora beticola,

Erysiphe necator,

B. cinérea,

M. graminicola,

O. acuformis, and

Podosphaera fusca, have been documented to develop resistance to azoles through modifications at the target site [

73,

78,

79,

80]. Remarkably, environments that utilize azoles are increasingly becoming contaminated with duplications of the cyp51A gene promoter, accompanied by specific amino acid substitutions TR34/L98H and TR46/Y121F/T289A. These duplications have also been identified in hospital patients who have never previously received antifungal treatments [

81,

82,

83,

84].

Metabolic resistance: Fungal pathogen uses its metabolic process to detoxify toxic chemical like fungicides. A fungus rapidly breaking down a fungicide may effectively render it inactive before its arrival at the intended site of action. Melanin, a metabolite produced by some pathogenic fungus (like

Alternaria alternata,

Magnaporthe grisea,

Cercospora sp. etc) imparts resistance in fungus against fungicides [

85,

86,

87]. A metabolite detoxifies fungicide by modifying structure and function of the fungicide leading to increase in its aggressiveness with fungicide tolerance. Metabolomics was introduced in order to detect relative changes in metabolite concentration resistant fungal population with the corresponding alternation in gene expression in comparison to sensitive one [

88]. Metabolic fingerprinting led the rapid and easy detection of metabolite facilitating pathogen resistance against a fungicide. Metabolic profiling of

Fusarium graminearum with the help of

1H NMR successfully identified signature metabolites responsible for pathogen resistance against benzimidazole fungicides [

88,

89]. In case of boscalid resistance in

A. nidulans, metabolic profiling confirmed the phenotypic manifestation and emphasized the significance of nucleobase transporters. This was accomplished by analyzing their influence on different biosynthetic pathways and the variation of metabolites at the target site. An identical report was documented by Karamanou et al. (2020), where toxic effects of the compound Flusilazole was unveiled with the help of GC-EI-MS based metabolomics study [

90]. It also indicated liaisoning between ABC transporters YCF1 with emergence of fungicide resistance.

Overexpression of target site: The overexpression of the target site represents an additional method to confer resistance to the fungal pathogen. Generally, there exists a competition between the fungicide and the natural substrates produced by fungi at the target site, where the inability of the natural substrates to compete effectively with the fungicide leads to the emergence of sensitive isolates. However, when overexpressed target sites are present within the fungal body, the natural substrate of the pathogen faces reduced competition at the target site, allowing the fungus to effectively bind its natural substrate to the target site enzyme. This process facilitates the maintenance of normal cellular respiration. Consequently, overexpression contributes to the pathogen’s survival to a certain degree, resulting in the development of resistant isolates [

79,

91,

92]. For instance, enhanced expression of drug target gene confers resistance in fungus against azole fungicides. It is being elucidated that overexpression of transcription regulators namely cyp51A/ERG11 contributed in azole resistance. SREBP (Sterol Regulatory Element Binding Protein) SrbA and Sre1 regulate the expression of cyp51A/ERG11 in

Aspergillus fumigatus and

Cercospora neoformans in response of azole exposure resulting in Azole resistance [

93,

94,

95].

Efflux transporter enabling fungal survival: Like bacteria, efflux transporter also facilitate exclusion of fungitoxic compound (phytoaniticipin, phytoalexin, fungicides) from fungal conferring resistance against them [

31,

67]. Two families of efflux transporters localized in the plasma membrane are known to be involved in the secretion of toxic substances, namely ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) transporters and Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) transporters. ABC transporters harness energy from ATP hydrolysis to transport a variety of structurally diverse substrates against a concentration gradient across the plasma membrane. MFS transporters, on the other hand, lack the ability to hydrolyze ATP and instead utilize the proton motive force to aid in the transport of not only toxicants but also sugars, peptides, and ions [

31,

67].

An accelerated drug efflux is a common antifungal resistance mechanism which functions in conjunction with overexpression or target modification. Azole resistance is frequently accompanied with overexpression of efflux pumps of plasma membrane and reduced intracellular drug accumulation. In contrast, resistance mechanisms mediated by efflux are seldom associated with adaptive resistance to echinocandins and polyenes, as these substances are weak substrates for pumps [

94,

96,

97].

Genome modification/ rearrangements: It involves chromosome translocations; sporadic formation of de novo mini-chromosomes, segmental duplications led the development of azole resistance in

Candida glabrata yeast [

98]. On study of clinical azole resistant isolates and laboratory derived azole resistant strain, duplication of left arm of chromosome 5 resulting in formation of isochromosome (i5(L)) [

94,

99]. Heteroresistance in

C. neoformans is often obtained through the formation of disomy, with chromosome 1, which houses both the ABC transporter genes AFR1 and ERG11, being the most prevalent disomic chromosome [

100]. In addition to these recent reports suggests that horizontal gene transfer (HGT) confers azole resistance in

Aspergillus fumigatus [

101].

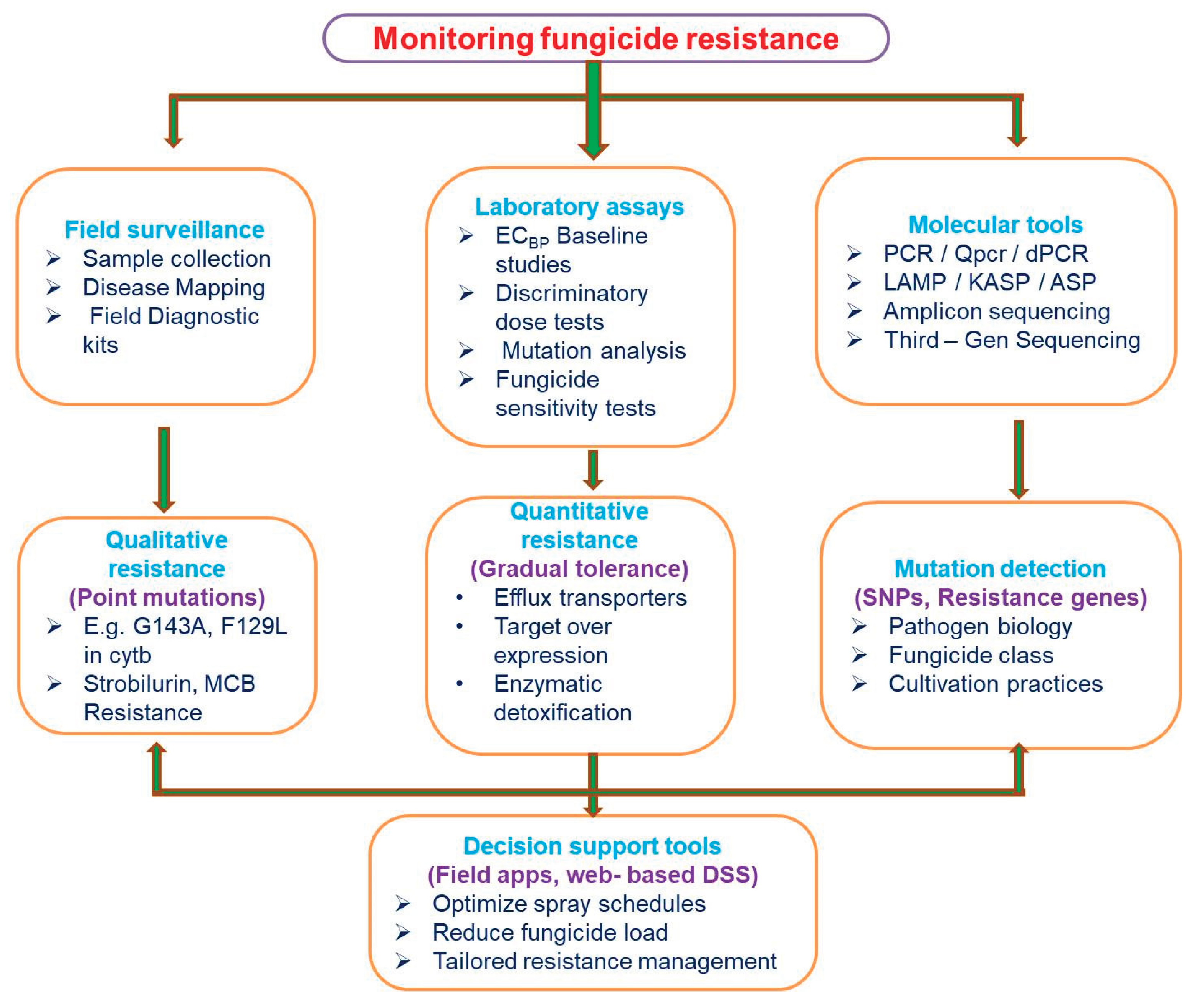

Monitoring Fungicide Resistance (SBS)

Monitoring initiatives are essential for comprehending the dynamics and emergence of fungicide resistance. They shed light on the different kinds of resistance, their frequency, their geographic distribution, and the risk and course of their spread. The development of precision resistance management strategies is based on this information (FRAC).

Figure 3 presented below gives an overview of monitoring of fungicidal resistance.

Establishing Sensitivity Baselines

Establishing baseline sensitivity, the innate sensitivity of pathogen isolates that have never been exposed to the fungicide, is crucial before introducing a new fungicide. Although obligate pathogens necessitate

in vivo evaluation, baselines are established by measuring EC₅₀ values (the effective concentration reducing growth by 50%) using

in vitro tests. A frequency histogram is produced by plotting these values. Current isolate sensitivity is compared to the baseline during follow-up field monitoring. Dosage adjustments may be necessary if the mean EC₅₀ of field isolates is noticeably higher, as this could suggest decreased sensitivity or resistance. As an alternative, resistant isolates can be promptly identified using a discriminatory dose, which is a single fungicide concentration. For instance, thousands of

Fusarium graminearum isolates were successfully screened for resistance to the drug using a 5.0 µg/mL discriminatory dose [

70].

Field-kit Based Techniques for Detection of Azole Fungicides

Using a field-based kit, Schnabel et al. (2012) presented a useful method for identifying fungicide resistance in fungal pathogens on turf grasses. Infected leaf blades are collected, their surfaces are sterilized, and they are then incubated on a growth medium. Because different fungicide application histories result in different resistance profiles, diseases like brown rot (

Monilinia fructicola) benefit greatly from this kit’s location-specific resistance monitoring approach. This system enables producers to make well-informed decisions for managing diseases before and after harvest when combined with professional advice from a web-based platform [

102].

Internet-supported Surveillance Systems

Internet-based decision support systems (DSSs) have become important tools in line with the European Green Deal’s objective to reduce use of chemical pesticides to half by 2030. Instead of using set calendars, these systems help farmers optimize fungicide application schedules based on current disease risk. DSSs can cut fungicide use by up to 50% without sacrificing disease control, according to a meta-analysis of 80 international studies [

103]. In actuality, DSSs frequently maintained better control than calendar-based methods, even when fungicide applications were reduced. These studies involved a wide range of pathogens, including Dothideomycetes (e.g.,

Alternaria alternata,

A. solani,

Cercospora asparagii), Sordariomycetes (e.g.,

Fusarium graminearum), Leotiomycetes (

Botrytis cinerea), Agaricomycetes (

Rhizoctonia solani), and Oomycetes (

Plasmopara viticola,

Bremia lactucae). The trials addressed diseases like downy mildew in grapes and lettuce, Fusarium head blight in wheat, Alternaria brown spot in citrus, early blight in tomatoes, and grey mold in strawberries. These studies included fungicides from a variety of FRAC risk categories:

Low risk: Phthalimides, copper hydroxide, dithiocarbamates (e.g., mancozeb)

Medium to high risk: Demethylation inhibitors (e.g., tebuconazole), SDHIs (e.g., boscalid), QoIs (e.g., trifloxystrobin)

Even under different disease pressures, DSS-based methods consistently led to fewer fungicide applications with comparable or only slightly higher disease incidences than traditional calendar methods [

103].

Molecular Diagnostics (PCR, qPCR, Sequencing)

The ability to identify fungicide resistance at low frequencies without culturing pathogens has improved owing to modern molecular tools. SNPs can be found using Sanger sequencing, but for large-scale applications, it is expensive and time-consuming. Faster but non-quantitative are PCR-based techniques such as PCR-RFLP [

104], CAPS [

105], and allele-specific PCR [

106]. Although it depends on standard curves, real-time PCR allows quantification, as demonstrated in the cases of

Erysiphe necator and

Blumeria graminis f. sp.

tritici [

107,

108,

109]. Other techniques, such as LAMP assays [

110,

111,

112] and PCR-luminex [

113], provide quick detection, particularly in field settings, but they are not quantifiable.

First introduced in 1999 [

114], digital PCR (dPCR) addresses many of the drawbacks of earlier methods. Using Poisson statistics to determine template abundance based on compartmentalized amplification reactions, dPCR provides high sensitivity, absolute quantification, and quick turnaround. It was first used in medical research [

115,

116,

117]. There are trade-offs associated with each of the different dispersion techniques (droplet, microwell, channel, printing). dPCR has been used in agriculture to detect genetically modified organisms (GMOs) [

118], monitor Aspergillus species on grapes [

119], identify

Phytophthora nicotianae in soils [

120], and study viruses in grapevines [

121]. Its use in fungicide resistance detection is promising, despite its recent infancy. For example,

Blumeria graminis f. sp.

hordei mutants (Y136F and S509T) were found in Australian barley fields using dPCR, providing a possible early warning system for the development of resistance.

By employing sequence-specific primers, allele-specific molecular tools like ASP, KASP, and LAMP allow for the accurate detection of SNPs. The most straightforward of these is allele-specific PCR (ASP), which uses a primer whose 3′ end corresponds to the mutant allele. The result is found using gel electrophoresis [

122,

123,

124,

125]. Although ASP is practical and affordable for crude DNA, its sensitivity for identifying low-frequency mutations is limited. In contrast to ASP, ASO probes discriminate by oligonucleotide binding [

126]. While LAMP uses complex primer sets and isothermal amplification to enable visual detection through turbidity, colorimetric / fluorescence indicators, or gel electrophoresis, KASP incorporates fluorescence detection for high-throughput SNP genotyping [

127,

128,

129,

130].

Many fungicide resistance mutations have been found using ASP, including Cyp51 mutations in

B. graminis f. sp.

hordei [

131], QoI resistance in

Z. tritici [

132], and carbendazim resistance in

F. graminearum [

133]. When combined with CRISPR-Cas12a, the modified iARMS method provides high sensitivity (~0.1%) [

134]. Cyp51 mutations in

Z. tritici and

P. striiformis have also been found using KASP [

135,

136]. Cyp51 and β2-tubulin gene mutations have been found using LAMP assays [

110,

112,

137,

138]. Quantitative mutation detection is offered by qPCR and dPCR. When wild-type and mutant alleles coexist, qPCR may not be as specific even though it uses fluorescence-based detection (SYBR Green or labeled probes) [

116,

139,

140].

Incorporating intentional mismatches can enhance this [

122,

141,

142,

143,

144]. By dividing the PCR reaction and using Poisson statistics, dPCR provides absolute quantification [

117,

145,

146]. Despite being sensitive and accurate [

147,

148], field use is limited by its high cost and requirement for specialized equipment. qPCR and dPCR are frequently used to track fungal resistance [

107,

148,

149,

150,

151]. For example, portable qPCR platforms have enabled in-field detection [

152], and qPCR was utilized to map DMI and SDHI target gene mutations in Z. tritici throughout Europe [

151].

As little as 0.008% of resistant alleles can be found using dPCR [

147]. Another method for detecting mutations is amplicon sequencing. Next-generation Illumina sequencing and pyrosequencing both depend on sequencing-by-synthesis chemistry [

153,

154,

155]. Mutations in

P. teres,

Z. tritici, and

R. commune have been found through pyrosequencing [

156,

157,

158]. Numerous loci, including those related to virulence, population diversity, and fungicide resistance, can be multiplexed by Illumina-based systems [

159].

Long-read sequencing for thorough haplotype analysis is made possible by third-generation sequencing, such as Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and PacBio SMRT [

160,

161]. ONT offers portability and ultra-long reads, while PacBio offers high-accuracy reads (~15–20 kb) [

162]. Using error correction techniques like Canu or UMI tagging [

163]; ONT and PacBio have been utilized to identify Cyp51 mutations in

Z. tritici and

P. teres [

164,

165]. Simple mutation detection based on restriction site alterations is provided by restriction-based PCR techniques like RFLP and PIRA [

166,

167].

These techniques have been used to track mutations in myosin-5, β2-tubulin, and cytb [

168,

169,

170]. When the mechanisms underlying QoI and CAA resistance in pathogens such as

P. viticola are well understood, molecular assays are employed [

171,

172,

173]. These mechanisms include G143A and F129L in cytb and G1105S/V in CesA3. PCR-RFLP, ARMS, or tetra-primer PCR assays are used to detect these [

174]. However, because

P. viticola is diploid, it is necessary to distinguish between heterozygous and homozygous mutations using different reactions or better assays [

174,

175]. TaqMan-MGB real-time PCR was created for increased specificity and throughput in order to combat false positives and low resolution [

176].

When resistance mechanisms are known, molecular tools work very well. They are essential for the early identification of low-frequency resistance alleles in field populations, despite their inability to set sensitivity baselines [

27,

177]. However, their applicability is limited by polygenic or unknown resistance mechanisms [

77]. Effective fungicide resistance monitoring therefore depends on continuous technological advancements and thorough resistance mapping.

LAMP-Based Techniques

Notomi et al. (2000) created the quick, sensitive method known as loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), which runs at a steady temperature [

128]. It takes 45 minutes to finish amplification using four to six primers that target six to eight regions in a resistance-associated gene. LAMP is ideal for field-based diagnostics because of its speed and ease of use. Fungicide resistance has been successfully identified using LAMP assays in

Botrytis cinerea,

Cercospora beticola,

Podosphaera xanthii [

111,

178,

179].

Resistance Risk Assessment

Agricultural practices, pathogen biology, and fungicide class all have an impact on the dynamic threat of fungicide resistance [

27,

186]. Some pathogens, like

Pseudocercospora fijiensis in bananas, which are exposed to a lot of fungicides – often up to 50 applications a year – develop resistance more quickly. Even among pathogens on the same crop, resistance risk can differ. For example,

Rhynchosporium commune poses a moderate risk of resistance, whereas

Ramulariacollo-cygni shows a high risk [

187]. Depending on the fungicide class, certain rusts can still be dangerous, but powdery mildews tend to develop resistance to cereals more quickly than rust fungi [

27,

49,

50]. Generally speaking, pathogens that are polycyclic, host-specific, or present in protected cultivation systems are more prone to development of resistance [

188].

Although it can be difficult to predict risk within site-specific categories, site-specific fungicides typically carry higher resistance risks than multisite inhibitors. Due to their high specificity in target-site binding, fungicides with larger molecular weights or complexity are frequently at higher risk of developing resistance from small mutations [

188,

189]. To estimate resistance potential, laboratory mutagenesis is frequently used, particularly when UV light is present. Even though not all of the mutations are field-relevant, these techniques aid in identifying those that confer high resistance [

190]. Mutagenesis is more informative than baseline sensitivity screens because resistance frequently results from

de novo mutations rather than pre-existing genetic variation [

184,

191].

Mutagenesis was used to identify several sdhB, sdhC, and sdhD mutations in

Zymoseptoria tritici for SDHI fungicides; many of these mutations were subsequently found in the field. But because of fitness costs that restrict their spread in competitive settings, some, like sdhC-H152R, remained uncommon [

192] (Gutiérrez-Alonso et al., 2017). Lalève et al. (2014) showed similar fitness trade-offs for other SDHI mutations, though compensatory adaptations can occasionally offset these costs [

193]. As evidenced by the variation in CYP51 alleles across field sites, environmental factors also affect which mutations become dominant [

194]. High-risk pathogens are usually the first to develop resistance, and the time between the introduction of fungicides and the emergence of resistance provides information about potential threats to other species in the future.

FRAC (2020a) states that multisite inhibitors are low, azoles are medium, morpholines are medium-low, SDHIs, dicarboximides, and QiIs are medium-high, and MBCs and QoIs are at high risk [

195]. Notwithstanding the inherent risk, maintaining fungicide efficacy requires resistance management, which includes monitoring, limiting the frequency of applications, and employing mixtures [

186]. Resistance factors, cross-resistance profiles, and the fitness effects of resistance mechanisms are important considerations when creating management plans.

Resistance Management Strategies for Azole Fungicide

Plant pathogens cause significant damage to plant products, compromising both quantities and quality. Efficient and effective crop protection is vital to safeguard food security and safety, but growers are trusting on a limited toolbox in the face of diverse and evolving pathogens. Protection of Crop against plant pathogens depends on fungicide use in addition to varietal resistance. However, frequent and repeated application of single-site fungicides with the same mode of action (MoA) can lead to the evolution of resistance. Discovery and development of fungicides with novel modes of action are some of the recent approaches to counter the issue of fungicide-resistance in some phytopathogens of economic significance (

Table 2).

Azoles have been a major fungicide among the site-specific group for the control of major diseases in a vast range of crops for more than 40 years [

44]. These fungicides revealed a wide spectrum of antifungal activity. They are applied as either seed treatment, foliar application, or post-harvest treatment. Azoles with a high efficacy already at low rates and often with clear visual benefits have been rapidly adopted by growers worldwide in many crop production systems. Despite intensive use and in contrast to other systemic and target-site fungicides, the azoles are still contributing positively to a wide range of disease control. However, regular application of these fungicides results in development of resistant populations in numerous fungal pathogens, including

Zymoseptoria tritici,

Colletotrichum sp.,

Venturia sp.,

Fusarium sp., and

Monilinia sp. in the field [

66]. The use of azoles in agriculture is decidedly argued in light of regulatory limitations concerns consisting, endocrine interruption, environmental fate relating to persistence and metabolites, fungicide resistance issues and particularly cross-resistance to azoles used in human or animal medicine for control of fungal infections. Azole resistance has been reported in 30 plant pathogens [

195], in over 60 countries [

43].

Managing azole fungicide resistance in crops, strategies should focus on diminishing disease, approaching alternative modes of action, and executing integrated approaches such as resistance cultivars, cultural practices, growing crop in pathogen free areas, extended crop rotation reduces disease carry over, bio control agents, appropriate use of fungicides. Elimination of disease source will be the alternative with which development of fungicidal resistance can be avoided. Anyhow, it is critical to use an effective disease management program to delay the build-up of resistant strains. The larger the pathogen population exposed to an at-risk fungicide, the greater the chance a resistant strain will develop. However, in the broad feature the management strategies and alternatives for fungicidal resistance in crop plants can be exploiting host resistance, exploitation of race-nonspecific resistance, enhancement of natural disease resistance, biotechnology approach, biological approach, use of botanical and many more.

Monitoring and Assessment

Detection and measurement of resistance in fungi against fungicides depends on a number of factors including the fungus-fungicide combination [

202] Regularly monitoring fungal populations for resistance development is essential for developing strategies for the application of fungicide and assessing fungicide recital. Monitoring and assessment also play important roles in making conversant decisions about fungicide application and recognizing or detecting areas / regions / zones where resistance is emerging. Monitoring and Assessment may also help to recognize trends in resistance development and direct management decisions through interoperating monitoring data. It is also done to assess the impacts and functioning of avoidance strategies or limitations, to find out the timeline of spread and intensity of resistance development [

203]. Although monitoring fungicidal resistance using “classical” (

in vitro and

in vivo) assays may help detect the degree of resistance, modern molecular genetic approaches facilitate analysis of a large number of field samples in a very short time if known mutations are responsible for resistance [

204].

Fungicide Rotation and Mixture

To combat azole fungicide resistance in crops, a multifaceted approach is crucial. This involves following strategies like limiting the selection and spread of resistant fungal strains; avoiding consecutive applications of the same fungicide or fungicides with similar mode of action; rotating fungicides with different modes of action prevents the continuous selection pressure on fungal populations; mixing fungicides with partners with different modes of action can provide a broader spectrum of control; and optimizing fungicide applications with integrating non-chemical disease management practices. Development of resistance in fungal species against fungicides may be prevented or delayed by the strategies in using fungicides-avoiding repetitive use of at risk fungicides, preference to a mixture or alteration with a partner molecule upon use of a single fungicide with a carefully monitored frequency and timing of application of fungicides (

Table 3) [

205].

Integrated Pest Management (IPM)

IPM integrates available management approaches to manage plant diseases. The judicious use of fungicides, along with various other management techniques, such as cultural practices and biological control, reduces reliance on chemicals. For example, using disease-resistant crop varieties, practicing crop rotation, and augmenting sowing/planting dates can reduce the need for fungicides. The main aim is to manage diseases effectively while minimizing the use of pesticides and their potential negative impacts. The additional measures for management of fungal diseases slow down the process of resistance selection with reduction in the size of population in which mutations can arise [

206,

207]. However, Beckerman et al. (2015) hypothesize that the implementation approaches of IPM have contributed to the issues of fungicide resistance [

208]. Induced resistance was found to be a valid strategy against

Venturia inaequalis populations with reduced sensitivity to a given fungicide [

209]. Damicone and Smith (2009) have listed cultural practices and use patterns of fungicides (

Table 4) that contribute to reduction in disease pressure and selection of fungicide resistance [

210]. Keeping the fact in view that as much as 30 plant pathogens have been found resistant to azole fungicides and that quinone outside inhibitor (QoI) resistance has been reported in almost 50 species [

211], it has become imperative that concrete measures be taken up to reduce the risk of resistance development and keep the molecule functioning for a longer time.

Future Direction for Fungicide Resistance

A. Socioeconomic Impacts

Reduced crop yields and quality: As fungi evolve resistance, fungicides become less effective, leading to increased crop losses and lower-quality produce. When fungal pathogens become resistant, fungicides lose their effectiveness. This allows diseases like

Botrytis,

Plasmopara, or

Magnaporthe to spread unchecked, damaging leaves, stems, and fruits. The results in

lower photosynthesis efficiency, premature plant death and incomplete grain or fruit development. In crops like wheat, rice, and grapes, this can translate to

yield losses of 20-50% in severe cases [

66,

212].

Increased production costs: Fungicide resistance significantly increases agricultural production costs through a combination of direct and indirect economic pressures. As resistance develops, farmers must apply fungicides more often or at higher doses to achieve the same level of disease control. This leads to:

higher input costs for chemicals and fuel and

increased labour expenses for repeated field operations.

“Fungicide resistance has affected the performance and active life of some highly promising fungicides, and in many instances, it has led to failure of disease control” [

212]. When older fungicides lose efficacy, growers are forced to adopt newer, often more costly, products with different modes of action. These may also require more complex application protocols. Corkley et al. (2022) emphasize that resistance shortens the effective life of fungicides, pushing growers toward newer, costlier solutions [

206]. Even with increased chemical use, resistant pathogens can still cause significant crop damage, leading to

reduced marketable yield and

lower quality produce, which fetches lower prices. A recent modeling study by Mikaberidze et al. (2025) quantified the

indirect cost of resistance as the difference in net returns between landscapes with and without resistance [

213]. The study found that resistance can significantly reduce profitability, especially when fungicide prices are high or resistance is widespread. This economic loss is compounded by the cost of ineffective treatments [

213].

Environmental Impacts

Escalated chemical use: To combat resistant strains, farmers may increase fungicide dosages or use multiple products, intensifying chemical loads in the environment. When pathogens develop resistance, the original fungicide becomes less effective. Farmers respond by increasing

application frequency, raising

dosage levels and switching to

multiple or more potent fungicides. Broader chemical spectrum to combat resistant strains, growers often resort to

fungicide mixtures or rotate between different chemical classes. While this can delay resistance, it also increases the

overall chemical load in the environment [

212].

Soil and water contamination: Fungicide resistance doesn’t just complicate disease control; it also intensifies

soil and water contamination through increased and prolonged chemical use. Persistent fungicide residues can disrupt soil microbiomes and leach into waterways, harming aquatic life. As resistant fungal strains emerge, farmers often respond by applying

higher doses or

multiple fungicides with different modes of action. This leads to:

accumulation of residues in the soil, which can disrupt microbial communities and reduce soil fertility and

non-target effects on beneficial fungi and bacteria, impairing nutrient cycling and organic matter decomposition.

Simultaneous application of fungicides significantly altered microbial activity in grassland soils – even in systems with high fungal diversity – highlighting the vulnerability of soil processes under fungicide stress [

214]. Fungicides, especially when overused, can leach into groundwater or run off into nearby water bodies. Resistance-driven over application increases this risk, leading to:

toxic effects on aquatic organisms, including algae, invertebrates, and amphibians and

persistence of fungicide residues in water due to their chemical stability.

Fusarium species, which have developed resistance to multiple fungicide classes, contribute to environmental contamination through increased chemical inputs and runoff [

215].

Biodiversity loss: Fungicide resistance contributes to

biodiversity loss by intensifying chemical use and disrupting ecological balance across soil, plant, and aquatic systems. As pathogens become resistant, farmers often respond with

higher doses or more frequent applications of fungicides. This increases exposure for non-target organisms, including b

eneficial fungi (e.g., mycorrhizae) that support plant nutrient uptake,

soil bacteria involved in nitrogen fixation and organic matter decomposition,

pollinators and insects that are sensitive to chemical residues. Over time, this chemical pressure reduces

species richness and functional diversity, weakening ecosystem resilience. A study highlights that how resistant

Fusarium species drive overuse of fungicides, which in turn

alters soil microbial communities and suppresses beneficial organisms. This microbial imbalance can lead to reduced soil fertility, increased vulnerability to secondary pathogens and loss of keystone microbial species. Fungicide runoff from resistant-driven over application contaminates water bodies, affecting

algae and aquatic fungi, which are foundational to food webs. To

amphibians and invertebrates, which are highly sensitive to fungicide residues, this cascade effect can lead to

local extinctions and altered trophic dynamics [

216]. According to a study it was found that

plant diversity can slow the evolution of fungicide resistance, while monocultures accelerate it. As resistance rises, farmers often simplify cropping systems to manage disease, further reducing

habitat heterogeneity and

species diversity [217].

Case Studies

Plasmopara viticola in European Vineyards: Downy mildew, caused by

P. viticola, thrives in humid conditions and can devastate grape yields. To manage it, growers have long relied on

QoI fungicides (quinone outside inhibitors), such as azoxystrobin. Over time, repeated use of QoI fungicides led to the emergence of resistant

P. viticola strains. In several European wine regions, especially in France and Italy,

resistance was confirmed through molecular diagnostics, revealing mutations in the

cytochrome b gene (notably the G143A mutation), which rendered the fungicides ineffective.

Reduced efficacy of fungicides, leads to increased disease outbreaks and

escalating costs as growers had to apply more fungicides or switch to alternative products. This case highlights how even well-established fungicides can lose their edge without careful stewardship [

218]).

Fungicide Resistance in Magnaporthe oryzae in Indian Rice Cultivation: Rice blast, caused by

M. oryzae, is one of the most destructive fungal diseases affecting rice in India, particularly in humid regions like Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, and West Bengal. Yield losses can range from 10% to 50%, depending on the severity and stage of infection. To manage rice blast, Indian farmers have traditionally relied on fungicides such as

tricyclazole,

isoprothiolane, and

strobilurin-triazole combinations. However, recent studies have documented r

educed sensitivity of

M. oryzae to tricyclazole and other site-specific fungicides, emergence of

resistant strains in fields with repeated fungicide applications and

breakdown of resistance in rice varieties due to pathogen variability and fungicide pressure [

219,

220].

Integration of Digital Agriculture and AI in Decision-making

The integration of

digital agriculture and artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing how farmers manage fungicide resistance – shifting from reactive spraying to predictive, data-driven strategies. AI models analyze real-time weather, crop phenology, and historical disease data to predict fungal outbreaks. This enables

timely fungicide applications, reducing unnecessary use,

selection of appropriate fungicide modes of action and slowing the resistance development [

221]. Smart sensors measure soil moisture, leaf wetness, and canopy temperature – factors critical to fungal growth. These data feed into AI systems that trigger

site-specific fungicide recommendations and reduce

blanket spraying, preserving beneficial organisms [

222]. AI-powered DSS tools like

CropIn,

Fasal, and

Xarvio® FIELD MANAGER integrates satellite imagery, field data, and agronomic models to recommend

fungicide rotation strategies, map

resistance risk zones and provide

real-time advisories to farmers. AI is increasingly used to analyze pathogen genomes, identifying mutations linked to fungicide resistance (

Table 5). This supports

early detection of resistance hotspots and tailored resistance management plans not only digital platforms also serve as educational tools, offering

localized training on resistance mitigation,

alerts and dashboards or safe fungicide use and

feedback loops between farmers, researchers, and policymakers [

223].

Impact of Fungicide Resistance on Human Health

The case of azole-resistant

Aspergillus fumigatus has highlighted that agricultural use of fungicides can potentially contribute to resistance development in non-target species that are also human pathogens, with consequences for human health (

Table 6). A balance is needed between maintaining the availability of fungicides that are important for food security [

228] and protecting the efficacy of antifungals used to treat serious invasive fungal infections (IFI).

Conclusion

Development of resistance to antimicrobial stresses is an evolutionary process which may have both advantages and disadvantages for microbial pathogen population. Over the time the resistant populations increased in number compared to the sensitive one which increases their fitness towards survival under such stresses.

The “One Health” framework recognizes that human, animal, and environmental health are inextricably linked, in areas including antimicrobial resistance and it is now increasingly recognized that plant health should be included too [

229], because plants are essential both in healthy ecosystems and for human nutrition. Antimicrobial resistance is a universal problem across human, animal, and plant health, including antibiotic resistance in livestock, human disease, and plant pathogens [

230], and fungicide resistance in fungal pathogens of humans and plants. A One Health approach to antimicrobial resistance (AMR) management necessitates robust policy and regulatory frameworks across human health, animal health, and environmental sectors. This includes addressing the misuse of fungicides, promoting responsible use, and preventing the spread of resistant strains. Policies should foster collaboration and coordination among sectors, ensure sustainable financing, and promote awareness and education regarding AMR and fungicide resistance.

References

- Ristaino JB, Anderson PK, Bebber DP, Brauman KA, Cunniffe NJ, Fedoroff NV, Finegold C, Garrett KA, Gilligan CA, Jones CM, Martin MD, MacDonald GK, Neenan P, Records A, Schmale DG, Tateosian L, Wei Q. The persistent threat of emerging plant disease pandemics to global food security. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Jun 8;118(23):e2022239118. Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Oct 5;118(40):e2115792118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2115792118. PMID: 34021073; PMCID: PMC8201941. [CrossRef]

- F.B.A. (2025, June 5). Bengal famine of 1943. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Bengal-famine-of-1943.

- Boyce, K.J. The Microevolution of Antifungal Drug Resistance in Pathogenic Fungi. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghannoum MA, Rice LB. Antifungal agents: mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999 Oct;12(4):501-17. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Darwin, C. On the Origin of Species. 1964. Harvard University Press.

- Hollomon DW and Brent KJ. Combating plant diseases - the Darwin connection 65,1156-1163. Pest Management Science, 2009; 65, 1156–1163. [CrossRef]

- Tillet, M. (1775). Dissertation on the cause of the corruption and smutting of the kernels of wheat in the head and on the means of preventing these untoward circumstances. Translated from French by Humpher H.B. Published by Amer. Phytopath. Soc. 1937. Ithaca, New York. Phytopathol. Classics No. 5.

- Prevost B 1807. Memoire sur la Cause Immediate de la Carie ouCharbon des Bles, et de PlusieursAutres Maladies des Plantes, et sur les Preservatifs de la Carie. Bernard, Paris.

- Riehm E. Prufungeinigermittelzurbekampfung des steinbrandes. Mitteiling der KaiserlichBiologischen Anstalt fur Land- u Forstwirtschaft 1913, 14, 8-9.

- Forsyth W 1802. A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees. Nichols, London.

- Millardet PMA 1885.Traitement du mildiou par le melange de sulfate de cuivre et de chaux. Journal d’Agriculture Pratique 49,513-516.

- Wain RL and Carter GA 1977. Historical aspects. In: Marsh, R.W. Wain RL and Carter GA 1977. Historical aspects. In: Marsh, R.W. (ed.) Systemic Fungicides. Longman, London, pp. 6-31.

- Misato T, Ko K and Yamaguchi I 1977. Use of antibiotics in agriculture. Advances in Applied Microbiology21,53-86.

- Harding PR. 1962 Differential sensitivity to sodium orthophenylphenate by biphenyl-sensitive andbiphenyl-resistant strains of Penicillium digitatum. Plant Disease Reporter 1962, 46, 100–104.

- Kuiper J. Failure of hexachlorobenzene to control common bunt of wheat. Nature 1965, 206, 1219–1220. [CrossRef]

- Noble M, Maggarvie QD, Hams AF and Leaf LL. Resistance to mercury of Pyrenophora avenae in Scottish seed oats. Plant Pathology 1966, 15, 23–28. [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, W. T. Schroeder, W. T., Provvidenti, R. Resistance to benomyl in powdery mildew of cucurbits. Plant Dis Rep 1969, 53, 271–275. [Google Scholar]

- Szkolink, M and Gilpatrick, J.D. 1969. Apparent resistance of Venturia inaequalis to dodine in New York apple orchards. Plant Dis Reptr 1969, 53, 861–864.

- Gilpatrick JD 1982. Case study 2: Venturia of pome fruits and Monilinia of stone fruits. In: Dekker, J. and Georgopoulos, S.G. (eds) Fungicide Resistance in Crop Protection. Pudoc, Wageningen, The Netherlands, pp. 195-206.

- Szkolnik, M. and Gilpatrick, J.D. Tolerance of Venturia inaequalis to dodine in relation to the history of dodine usage in apple orchards. Plant Dis Rep 1973, 57, 817–821.

- Bent KJ, Cole AM, Turner JAW and Woolner M 1971. Resistance of cucumber powdery mildew todimethirimol. In: Proceedings 6th British Insecticides and Fungicides Conference. British Crop Protection Council, London, pp. 274-282.

- Eckert, J.W. , 1982. Case study 5: Penicillium decay of citrus fruits. Fungicide resistance in crop protection, pp.231-250.

- Leroux, P. & Clerjeau, M., 1985. Resistance of Botrytis cinerea Pers. and Plasmopara viticola (Berk. & Curt.) Berl. and de Toni to fungicides in French vineyards. Crop Protection 4, 137–160. [CrossRef]

- Littrell, R. H. , 1974. Tolerance in Cercospora arachidicola to benomyl and related fungicides. Phytopathology 64, 1377–1378. [CrossRef]

- Stover, R. H. , 1979. Field observations on benomyl tolerance in ascospores of Mycosphaerella fijiensis var difformis.. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 72, 518–519. [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M. J., Drummond, M., Yarham, D. J., King, J. E. & Brown, M. (1982). Benzimidazole resistance in Pseudocercosporella herpotrichoides, the cause of eyespot disease of cereals. International Society for Plant Pathology, Chemical Control Newsletter 1, 7–8.

- Brent, K.J.; Hollomon, D.W. 2007. Fungicide resistance in crop pathogens. How can it be managed. In FRAC Monograph; No. 1; CropLife International: Brussels, Belgium.

- Giannopolitis, C. N. Lesions on sugarbeet roots caused by Cercospora beticola. Plant Dis. Rep 1978, 62, 424–427. [Google Scholar]

- Staub, T. Fungicide resistance: Practical experience with anti-resistance strategies and the role of integrated use. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol, 1991; 29, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, D.H. and Eichhorn, K.W., 1983. Botrytis cinerea and its resistance to dicarboximide fungicides. Paper presented at the International Symposium on Grey mould of Grapevine, Colmar (France) 24-26 March 1981. Bulletin OEPP EPPO Bulletin (June 1982). 12 (2):125-129.

- de Waard MA, Andrade AC, Hayashi K, Schoonbeek HJ, Stergiopoulos I, Zwiers LH. Impact of fungal drug transporters on fungicide sensitivity, multidrug resistance and virulence. Pest Manag. Sci. 2006, 62, 195–207. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaney, S.P., Hall, A.A., Davies, S.A. and Olaya, G., 2000. Resistance to fungicides in the Qol-STAR cross-resistance group: current perspectives. Book chapter (Conference paper): The BCPC Conference: Pests and diseases, Volume 2. Proceedings of an international conference held at the Brighton Hilton Metropole Hotel, Brighton, UK, 13-16 November 2000, 2000, 755-762 ref. 2. ISBN: 1-901396-59-2. Publisher: British Crop Protection Council.

- Avenot, H.F. Avenot, H.F. and Michailides, T.J. Resistance to boscalid fungicide in Alternaria alternata isolates from pistachio in California. Plant Disease 2007, 91, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, T.D., Fairchild, K.L., Merlington, A., Kirk, W.W., Rosenzweig, N. and Wharton, P.S. First report of boscalid and penthiopyrad-resistant isolates of Alternaria solani causing early blight of potato in Michigan. Plant Disease, 97(12), pp.1655-1655. 2013, 97, 1655. [CrossRef]

- Cannon RD, Lamping E, Holmes AR, Niimi K, Baret PV, Keniya MV, Tanabe, K, Niimi M,Goffeau A, Monk BC 2009 Efflux-Mediated Antifungal Drug Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. :22, 291–321.

- Horsten J, & Fehrmann H 1980. Fungicide resistance of Septoria nodorum and Pseudocercosporellaherpotrichoides.1. Effect of fungicide application on the frequency of resistant spores in the field. Zeitschrift Fur Pflanzenkrankheiten Und Pflanzenschutz-Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection, 87(8), 439–453.

- Fehrmann H, Horsten J, &Siebrasse G 1982. Five years’ results from a long-term field experiment on carbendazim resistance of Pseudocercosporellaherpotrichoides (Fron) Deighton. Crop Protection, 1(2), 165–168.

- Brown MC, Taylor GS, & Epton HAS 1984. Carbendazim resistance in the eyespot pathogen Pseudocercosporellaherpotrichoides. Plant Pathology, 33(1), 101–111. [CrossRef]

- Hocart MJ, Lucas JA &Peberdy JF 1990. Resistance to fungicides in field isolates and laboratory-induced mutants of Pseudocercosporella herpotrichoides. Mycological Research, 94,9–17.

- Albertini C, Gredt M, & Leroux P 1999. Mutations of the beta-tubulin gene associated with different phenotypes of benzimidazole resistance in the cereal eyespot fungi Tapesiayallundae and Tapesiaacuformis. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology, 64(1), 17–31.

- Metcalfe NDS, Sanderson RA & Griffin MJ 1985. Comparison of carbendazim and propiconazole for control of Septoria tritici at sites with different levels of MBC resistance. International Society of Plant Pathology Chemical Control Newsletter, 6,9–11.

- Leroux P, Albertini C, Gautier A, Gredt M & Walker AS 2007. Mutations in the CYP51 gene correlated with changes in sensitivity to sterol 14 alpha-demethylation in hibitors in field isolates of Mycosphaereliagraminicola. Pest Management Science, 63(7), 688–698.

- Fisher, M.C. , Hawkins, N.J., Sanglard, D. and Gurr, S.J. 2018. worldwide emergence of resistance to antifungal drugs challenges human health and food security. Science, 360: 739–742. [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, L.N. , Matzen, N., Heick, T.M., Havis, N., Holdgate S., Clark B., et al. 2021. Decreasing Azole Sensitivity of Z. Tritici in Europe Contributes to Reduced and Varying Field Efficacy. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 128, 287–301. 10.1007/s41348-020-00372-4. [CrossRef]

- Senior IJ, Hollomon DW, Loeffler RST and Baldwin BC 1995. Sterol Composition and Resistance to DMI Fungicides in Erysiphe graminis. Pest Manag. Sci. 45 (1), 57–67. [CrossRef]

- Tucker MA, Lopez-Ruiz F, Cools HJ, Mullins JGL, Jayasena K, and Oliver RP 2019. Analysis of Mutations in West Australian Populations of Blumeria graminisF. Sp. hordei CYP51 Conferring Resistance to DMI Fungicides. Pest Manag. Sci. 76, 1265–1272.

- Hobbelen PHF, Paveley ND & van den Bosch F 2014. The emergence of resistance to fungicides. PLoS One, 9, e91910.

- Amaradasa BS & Everhart SE 2016. Effects of sublethal fungicides on mutation rates and genomic variation in fungal plant pathogen, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. PLoS One, 11, e0168079.

- Oliver RP 2014. A reassessment of the risk of rust fungi developing resistance to fungicides. Pest Management Science, 70, 1641–1645. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. P. (2014). Resistance risks different between powdery mildews and rust fungi in cereal crops. In: The 2014 Mycological Progress Congress (poster/oral presentation).

- Blanquart, F. 2019. Evolutionary epidemiology models to predict the dynamics of antibiotic resistance. Evolutionary Applications, 12, 365–383. [CrossRef]

- Garnault M, Duplaix C, Leroux P, Couleaud G, David O, Walker AS et al. 2021. Large- scale study validates that regional fungicide applications are major determinants of resistance evolution in the wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici in France. New Phytologist, 229, 3508–3521. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen LN, van den BoschF, Oliver RP, Heick TM &Paveley ND 2017. Targeting fungicide inputs according to need. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 55, 181–203.

- Angelotti F, Buffara CRS, Tessamnn DJ, Vieira RA & Vida JB 2014. Protective, curative and eradicative activities of fungicides against grapevine rust. Ciencia Rural, 44, 1367–1370. [CrossRef]

- Blake JJ, Gosling P, Fraaije BA, Burnett FJ, Knight SM, Kildea S et al. 2018. Changes in field dose- response curves for demethylation inhibitor (DMI) and quinone outside inhibitor (QoI) fungicides against Zymoseptoria tritici, related to laboratory sensitivity phenotyping and genotyping assays. Pest Management Science, 74, 302–313.

- Sanatkar MR, Scoglio C, Natarajan B, Isard SA & Garrett KA 2015. History, epidemic evolution, and model burn- in for a network of annual invasion: soybean rust. Phytopathology, 105, 947–955.

- Cohen Y, Rubin AE & Galperin M 2018. Oxathiapiprolin- based fun gicides provide enhanced control of tomato late blight induced by mefenoxam-insensitive Phytophthora infestans. PLoS One, 13, e0204523. [CrossRef]

- van den Bosch F, Oliver R, van den Berg F & Paveley N 2014a. Governing principles can guide fungicide- resistance management tactics. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 52, 175–195. [CrossRef]

- van den Bosch F, Paveley N, van den Berg F, Hobbelen P & Oliver R 2014b. Mixtures as a fungicide resistance management tactic. Phytopathology, 104, 1264–1273. [CrossRef]

- Paveley, N. , Grimmer, M., Powers, S.J. and Van Den Bosch, F., 2014. Improving the predictive power of fungicide resistance risk assessment. Modern fungicides and antifungal compounds, vol. 7, pp.153-160. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/pdf/10.5555/20153047511.

- Paveley, N.; van den Bosch, F.; Grimmer, M. Assessing the potential risk of humanpathogen resistance to medical antifungal treatments arisingfrom agricultural use of fungicides with the same mode of action. Plant Pathology, 2025, 74, 578–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]