Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

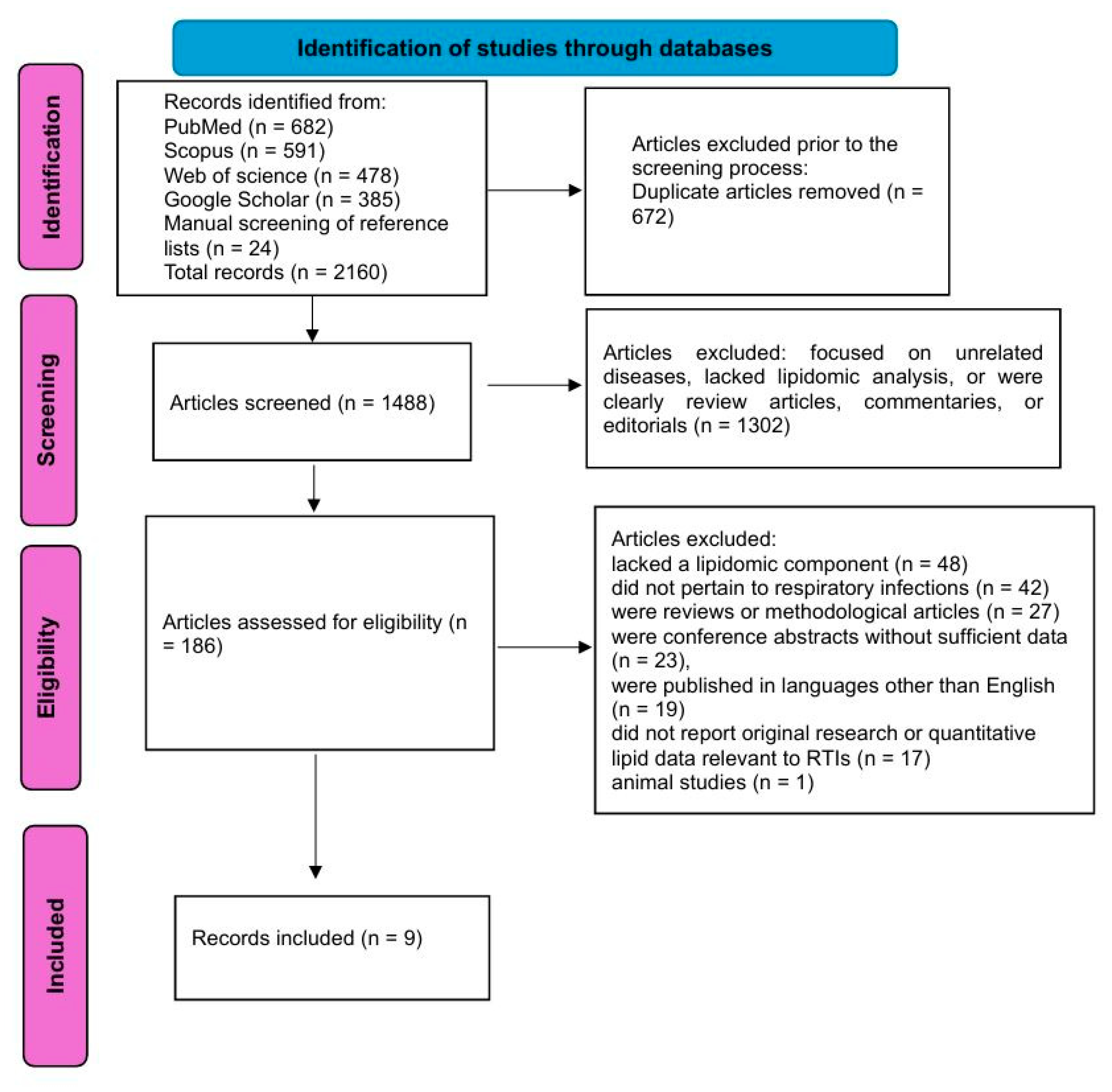

2.3. PRISMA Process

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics and Analytical Platforms

3.2. Identified Lipid Biomarkers in RTIs

3.3. Role of Lipidomics in Pathophysiological Insights

3.4. Lipidomic Alterations by Pathogen Type

3.5. Temporal Dynamics and Prognostic Implications

3.6. Integrative Models and Clinical Translation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Georgakopoulou, VE. Insights from respiratory virus co-infections. World J Virol. 2024;13(4):98600. [CrossRef]

- Georgakopoulou VE, Lempesis IG, Tarantinos K, Sklapani P, Trakas N, Spandidos DA. Atypical pneumonia (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2024;28(5):424. [CrossRef]

- Hanage WP, Schaffner W. Burden of Acute Respiratory Infections Caused by Influenza Virus, Respiratory Syncytial Virus, and SARS-CoV-2 with Consideration of Older Adults: A Narrative Review. Infect Dis Ther. 2025;14(Suppl 1):5-37. [CrossRef]

- Liapikou A, Torres A. The clinical management of lower respiratory tract infections. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2016;10(4):441-452. [CrossRef]

- Lim, WS. Pneumonia—Overview. Encyclopedia of Respiratory Medicine. 2022:185–97. [CrossRef]

- Wenk, MR. Lipidomics of host-pathogen interactions. FEBS Lett. 2006 ;580(23):5541-51. [CrossRef]

- Han X, Gross RW. Shotgun lipidomics: multidimensional MS analysis of cellular lipidomes. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2005;2(2):253-64. [CrossRef]

- Anh NK, Thu NQ, Tien NTN, Long NP, Nguyen HT. Advancements in Mass Spectrometry-Based Targeted Metabolomics and Lipidomics: Implications for Clinical Research. Molecules. 2024 Dec 16;29(24):5934. [CrossRef]

- Cajka T, Fiehn O. Comprehensive analysis of lipids in biological systems by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Trends Analyt Chem. 2014 Oct 1;61:192-206. [CrossRef]

- Wu Z, Shon JC, Liu KH. Mass Spectrometry-based Lipidomics and Its Application to Biomedical Research. J Lifestyle Med. 2014 Mar;4(1):17-33. [CrossRef]

- Schenck EJ, Plataki M, Wheelock CE. A Lipid Map for Community-acquired Pneumonia with Sepsis: Observation Is the First Step in Scientific Progress. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024;209(8):903-904. [CrossRef]

- Rischke S, Gurke R, Zielbauer AS, Ziegler N, Hahnefeld L, Köhm M, Kannt A, Vehreschild MJ, Geisslinger G, Rohde G, Bellinghausen C, Behrens F, Study Group C. Proteomic, metabolomic and lipidomic profiles in community acquired pneumonia for differentiating viral and bacterial infections. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):1922. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Zheng Y, Zhao L, Zhang Y, Yin L, He Y, Ma X, Xu Y, Gao Z. Lipid profiles and differential lipids in serum related to severity of community-acquired pneumonia: A pilot study. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0245770. [CrossRef]

- Shan J, Qian W, Shen C, Lin L, Xie T, Peng L, Xu J, Yang R, Ji J, Zhao X. High-resolution lipidomics reveals dysregulation of lipid metabolism in respiratory syncytial virus pneumonia mice. RSC Adv. 2018 Aug 17;8(51):29368-29377. [CrossRef]

- Virgiliou C, Begou O, Ftergioti A, Simitsopoulou M, Sdougka M, Roilides E, Theodoridis G, Gika H, Iosifidis E. Untargeted Blood Lipidomics Analysis in Critically Ill Pediatric Patients with Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia: A Pilot Study. Metabolites. 2024;14(9):466. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. [CrossRef]

- Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses.

- Castañé H, Iftimie S, Baiges-Gaya G, Rodríguez-Tomàs E, Jiménez-Franco A, López-Azcona AF, Garrido P, Castro A, Camps J, Joven J. Machine learning and semi-targeted lipidomics identify distinct serum lipid signatures in hospitalized COVID-19-positive and COVID-19-negative patients. Metabolism. 2022;131:155197. [CrossRef]

- Chouchane O, Schuurman AR, Reijnders TDY, Peters-Sengers H, Butler JM, Uhel F, Schultz MJ, Bonten MJ, Cremer OL, Calfee CS, Matthay MA, Langley RJ, Alipanah-Lechner N, Kingsmore SF, Rogers A, van Weeghel M, Vaz FM, van der Poll T. The Plasma Lipidomic Landscape in Patients with Sepsis due to Community-acquired Pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024 Apr 15;209(8):973-986. [CrossRef]

- Saballs M, Parra S, Martínez N, Amigo N, Cabau L, Iftimie S, Pavon R, Gabaldó X, Correig X, Paredes S, Vallvé JM, Castro A. Lipidomic and metabolomic changes in community-acquired and COVID-19 pneumonia. J Lipid Res. 2024;65(9):100622. [CrossRef]

- Kassa-Sombo A, Verney C, Pasquet A, Vaidie J, Brea D, Vasseur V, Cezard A, Lefevre A, David C, Piver E, Nadal-Desbarats L, Emond P, Blasco H, Si-Tahar M, Guillon A. Lipidomic signatures of ventilator-associated pneumonia in COVID-19 ARDS patients: a new frontier for diagnostic biomarkers. Ann Intensive Care. 2025;15(1):78. [CrossRef]

- Ma X, Chen L, He Y, Zhao L, Yu W, Xie Y, Yu Y, Xu Y, Zheng Y, Li R, Gao Z. Targeted lipidomics reveals phospholipids and lysophospholipids as biomarkers for evaluating community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10(7):395. [CrossRef]

- Schuurman AR, Chouchane O, Butler JM, Peters-Sengers H, Joosten S, Brands X, Haak BW, Otto NA, Uhel F, Klarenbeek A, van Linge CC, van Kampen A, Pras-Raves M, van Weeghel M, van Eijk M, Ferraz MJ, Faber DR, de Vos A, Scicluna BP, Vaz FM, Wiersinga WJ, van der Poll T. The shifting lipidomic landscape of blood monocytes and neutrophils during pneumonia. JCI Insight. 2024;9(4):e164400. [CrossRef]

| First Author | Year | Country | Study Design | Population | Sample Type | Analytical Platform | Lipid Classes Analyzed | Main findings | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Castané [18] | 2022 | Spain | Retrospective post-hoc cohort study | 126 hospitalized COVID-19 patients, 45 hospitalized COVID-19-negative patients (infectious/inflammatory), 50 healthy controls | Serum | Semi-targeted lipidomics by UHPLC-QTOF-MS, machine learning (Monte Carlo, PCA, PLS-DA) | Acylcarnitines, lysophospholipids (LPC, LPE), phosphatidylcholines (PC), oxylipins (e.g., 9/13-HODE, 15-HETE), bile acids, long-chain TGs | COVID-19 and non-COVID inflammatory patients shared a common lipid signature characterized by elevated acylcarnitines and LPE, and decreased 9/13-HODE and 15-HETE. However, specific discrimination between COVID-19 and other conditions was achieved via decreased LPC(22:6-sn2), increased PC(36:1), and changes in secondary bile acids. Arachidonic acid levels were markedly decreased in both COVID-19 and other infectious groups. Machine learning identified oxylipins, carnitines, and phospholipids as key discriminatory features. Alterations in β-oxidation and fatty acid metabolism were prominent. The ratio of LPC22:6-sn2/PC36:1 achieved an AUC > 0.95. No association was found with ICU admission or mortality. |

8/9 |

| Chen [13] | 2021 | China | Cross-sectional pilot study | 28 CAP patients (13 severe, 15 non-severe), 20 matched non-CAP controls | Serum | Untargeted UHPLC-MS/MS lipidomics, OPLS-DA, ROC, multivariate regression | Glycerophospholipids (PC, PE), sphingolipids (SM, HexCer), lysophospholipids (LPC, LPE), diacylglycerols, cholesterol esters, free fatty acids | Lipid profiles differed significantly across NC, NSCAP, and SCAP groups. CAP patients exhibited reduced LPC and PE levels, increased Hex2Cer and cholesterol esters. Four lipids (PC[16:0_18:1], PC[18:2_20:4], PC[36:4], PC[38:6]) outperformed CURB-65 and PSI in ROC analysis for disease severity. PC(18:2_20:4) had AUC 0.954, PC(38:6) had AUC 0.959. PC(18:2_20:4) and PC(36:4) correlated negatively with FiO2 and PCT; PC(16:0_18:1) positively with PCT. Lower PC levels were linked to longer hospital stay and higher 30-day mortality. Combined phospholipid biomarkers showed potential for disease monitoring, diagnosis, and prognosis in CAP. |

7/9 |

| Chouchane [19] | 2024 | Netherlands | Prospective cohort study | 169 ICU patients with CAP sepsis, 51 noninfected ICU controls, 48 outpatient controls; plus two validation cohorts (CAPSOD, EARLI) | Plasma | Untargeted lipidomics via HPLC-MS (1,833 lipid species across 33 classes), data validated in external cohorts | Cholesterol esters, triacylglycerols, phospholipids (PC, PE, LPC), sphingomyelins, ceramides, sulfatides, plasmalogens, lysolipids | Patients with sepsis due to CAP exhibited a profound shift in the plasma lipidome compared to both healthy and noninfected ICU controls. 58% of lipid species were decreased, while 6% increased. Cholesterol esters and lysophospholipids showed strong inverse associations with SOFA score and systemic inflammation. Recovery of specific lipids such as cholesterol esters by Day 4 in ICU was linked to lower 30-day mortality (e.g., OR=0.84 per 10% increase). The lipidomic profile showed partial recovery over time, and a specific TG-rich pattern distinguished CAP from other ICU patients. LPC and Chol-E emerged as key prognostic lipids. Lipid class patterns were validated across CAPSOD and EARLI cohorts. Results support lipidomics as a biomarker and prognostic tool in CAP-associated sepsis. | 9/9 |

| Rischke [12] | 2025 | Germany | Prospective cohort study | 69 patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP): 43 viral (incl. COVID-19), 26 bacterial | Plasma (baseline, day 3, day 7) | LC-MS/MS (MxP Quant 500), Olink proteomics, lipid network enrichment (LINEX2), PLS-DA, PCA | Phosphatidylcholines, ether-PCs, lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC), triglycerides, diglycerides, bile acids (GCA, TCA, TCDCA), oxylipins (EpOME, DiHOME) | Distinct plasma lipidomic profiles differentiated viral from bacterial CAP. Bacterial CAP was characterized by elevated PCs and PC-ethers, while viral CAP showed increased TGs, DGs (especially FA 18:2-containing), and linoleic acid–derived oxylipins (12,13-EpOME, 9,10-DiHOME). Proteomic markers like TRAIL, LAG-3, and LAMP3 were elevated in viral CAP, while CLEC4D and EN-RAGE were elevated in bacterial CAP. Integrated clustering of lipidomic, metabolomic, and proteomic analytes supported co-expression of pathogen-specific patterns. PLS-DA and hierarchical clustering identified robust discriminatory features. Findings indicate the potential of lipidomics and multi-omics in pathogen-specific diagnosis and individualized treatment strategies in CAP. |

8/9 |

| Saballs [20] | 2024 | Spain | Prospective observational study | 71 CAP patients, 75 COVID-19 pneumonia patients, 75 healthy controls (age- and sex-matched) | Serum | 1H NMR spectroscopy (Liposcale® assay), BUME extraction, LipSpin, multivariate analysis (PLS-DA, random forest, ROC) | Phosphatidylcholine, lysophosphatidylcholine, PUFA, DHA, esterified/free cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL/LDL/VLDL subclasses, glycoproteins | Both CAP and COVID-19 pneumonia patients exhibited hypolipidemia with reduced levels of HDL-c, phosphatidylcholine, lysophosphatidylcholine, PUFA, and DHA. Severity was associated with increased VLDL-c, IDL-c, LDL-tg/LDL-c, triglycerides, and glycoproteins (GlycA, GlycB, GlycF), along with decreased HDL particles and esterified cholesterol. COVID-19 patients showed more pronounced alterations. A lipidomic-metabolomic model based on PC, glycerophospholipids, creatine, glutamate, isoleucine, alanine, and glycoproteins achieved AUC = 0.935 for etiology classification and 0.931 for severity. Metabolites linked to inflammation and energy metabolism (lactate, glucose, creatine, BCAAs, glutamate) were elevated. Decreased glutamine and DHA in severe COVID-19 suggest impaired immune energy supply and pro-inflammatory resolution failure. These alterations reflect lipid-mediated immune modulation, metabolic reprogramming, and potential for diagnostic/prognostic biomarker development. |

7/9 |

| Kassa-Sombo [21] | 2025 | France | Prospective observational cohort study | 39 patients with COVID-19 ARDS (26 with VAP, 13 without VAP), matched controls | Tracheal aspirate | Untargeted lipidomics via UHPLC-HRMS (Q-Exactive MS), data processed with Workflow4Metabolomics/XCMS | Phosphatidylcholines, phosphatidylethanolamines, sphingomyelins, ether-linked PCs and PEs, lysophospholipids | Significant alterations in the tracheal aspirate lipidome were observed in VAP versus non-VAP COVID-19 ARDS patients (p = 0.003). Among 272 identified lipids, PCs were most frequently dysregulated, with 17 upregulated and 6 downregulated. SM(34:1) and PC(O-34:1) were the most predictive biomarkers for VAP, showing AUROC of 0.85 and 0.83 respectively. Eight key lipids were identified via multivariate analyses (PCA, PLS-DA, OPLS-DA), all upregulated in VAP. Lipidomic changes reflected breakdown of surfactant and pulmonary cells rather than bacterial origin. Combined lipid biomarkers modestly improved diagnostic performance (AUROC up to 0.86). These results suggest that lipidomics of tracheal aspirates offers potential for accurate VAP diagnostics and highlights lipid remodeling at the site of infection. |

8/9 |

| Ma [22] | 2022 | China | Prospective multi-center cohort study | 58 patients with CAP (30 NSCAP, 28 SCAP), 11 healthy controls | Serum | Targeted LC-MS/MS, qRT-PCR validation, GEO database transcriptome analysis | Phosphatidylcholine (PC), lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE) | LPC levels were decreased, while PE, PC, PC/LPC, and PE/LPE ratios were increased in CAP. PE combined with CURB-65 predicted severity (AUC = 0.848), while PC/LPC ratio improved 30-day mortality prediction (AUC = 0.838). PC(36:4) and LPC(18:2/0:0) emerged as species-level biomarkers. Expression of LPCAT2 was upregulated and LPCAT1 downregulated in SCAP; LPCAT2 positively correlated with inflammatory genes, LPCAT1 negatively. Lipid ratios (PC/LPC, PE/LPE) and PE were positively correlated with CRP, neutrophil percentage, and PSI, and negatively with albumin and lymphocytes. Alterations in Lands cycle enzymes support metabolic dysregulation during infection. | 8/9 |

| Schuurman [23] | 2024 | Netherlands | Case-control cohort study | 48 CAP patients (baseline and 1-month follow-up), 25 matched noninfectious controls | Isolated blood monocytes and neutrophils | Untargeted HPLC-MS lipidomics with transcriptomics integration | Sphingolipids (SM, ceramides, S1P), phospholipids (PC, PE), lysophospholipids (LPC, LPE), fatty acids, diacylglycerols (DG), triglycerides (TG), BMPs | Pneumonia significantly altered the lipidomic landscape of monocytes and neutrophils, with distinct profiles. Monocyte lipid changes were mostly decreases in PC, PE, and SM species and resolved after 1 month. In contrast, neutrophils showed persistent changes with increased PC, PE, DG, BMP, and polyunsaturated TGs. Sphingolipid metabolism, particularly S1P signaling, was upregulated. Transcriptomic analysis confirmed upregulation of key enzymes (SPHK1, UGCG, SMPD1). Functional validation showed that inhibiting SPT and SPHK1 blunted cytokine production in both cell types. The study demonstrated a mechanistic link between altered lipid profiles and immune function during CAP. | 9/9 |

| Virgiliou [15] | 2024 | Greece | Prospective pilot cohort study | 20 critically ill pediatric patients (12 high VAP suspicion, 8 low suspicion) | Plasma (blood samples at 4 timepoints: Days 1, 3, 6, 12) | Untargeted LC-HRMS (UPLC-TIMS-TOF/MS), multivariate + univariate analysis, MS-DIAL, Lipostar2 | Phosphatidylcholines (PC), lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC), sphingomyelins (SM), triglycerides (TG), diglycerides (DG), cholesterol esters (CE), carnitines | Untargeted lipidomics revealed 144 blood lipid species in critically ill pediatric patients with VAP suspicion. PCs, SMs, TGs, and DGs were significantly altered between high and low mCPIS groups. High suspicion group showed increased levels of PCs and TGs over time. Discriminatory lipids (e.g., PC 32:2, TG 48:3, SM 40:1) had AUC > 0.75. Specific lipid profiles were associated with culture-confirmed pathogens, including S. aureus and K. pneumoniae. Multivariate models (OPLS-DA) distinguished both VAP severity and pathogen type. Phospholipid shifts correlated with inflammatory markers and may indicate pathogen-specific metabolic remodeling. The study supports lipidomics as a promising diagnostic tool for early VAP identification and microbial stratification in pediatric ICU settings. | 7/9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).