1. Introduction

The boundary integral equation (BIE) method is a very powerful approach for the numerical solution of various boundary value problems (BVPs). The main advantage of BIE method consists in the dimensionality decrease of the given differential problem: the BVP is reduced to the BIE, where the unknown function is defined only on the domain boundary [

1]. Clearly, the considered differential equation needs to have the fundamental solution and to be homogeneous. For the numerical solution of such BIE, effective numerical methods are developed, for example, projection methods [

1].

In the case of non-stationary BVPs, there are additional difficulties caused by the presence of time as an independent variable. There are several ways to apply BIE to such BVPs. One approach involves a fundamental solution of the time-dependent differential equation. Then, by a direct or indirect BIE method, the initial BVP can be reduced to a time-boundary integral equation. The numerical solution of such a BIE is more difficult than in the stationary case. The most popular method for time-boundary integral equations is the convolution quadrature method suggested by Christian Lubich in the 1980s [

2].

Another so-called two-steps methods consist of the semi-discretization of the given initial BVP with respect to the time variable. As a result, the set of stationary BVPs for elliptic equations is obtained. This time discretization can be achieved using approaches such as finite-difference approximations (e.g., the Rothe method [

3]) or integral transforms (e.g., the Laguerre transform [

4,

5,

6,

7], the Laplace transform [

8]). In the second step, which addresses the spatial variable, various techniques are available, including the BIE method. Two-step methods offer several advantages, such as dimension reduction and the avoidance of volume integrals. The finite-difference semi-discretization is the simplest approach, which gives the numerical solution in a fixed set of time moments. In the case of the integral transforms, we have an approximation for arbitrary time, but it is necessary to calculate the inverse transform numerically.

The Laguerre transform for a parabolic initial BVP leads to stationary BVPs for a recurrent sequence of elliptic equations, and to apply the BIE method, one needs to find the fundamental sequence [

4,

7]. The inverse Laguerre transform has the form of the Fourier-Laguerre series, and its summation is a complicated ill-posed problem, especially for long-time moments. In the case of the Laplace transform to a parabolic initial BVP, stationary BVPs for the Helmholtz-type equations with complex parameters can be obtained. The inverse Laplace transform is defined as the Bromwich integral on the complex plane, and there are several numerical methods for its calculation [

9].

In this paper, we use the two-step approach based on the Laplace transform and the BIE method to solve parabolic BVPs in 3D domains. To calculate the inverse transform, the sinc-quadrature rule suggested in [

10] is applied. Our contribution is to reduce computational costs by selecting optimal values of the quadrature formula parameters and applying an efficient method for numerically solving the resulting BIEs.

The outline of the present work is as follows. In

Section 2, we apply the Laplace transform to the parabolic initial boundary value problem and describe the sinc-quadrature for the numerical inverse transform. Two ideas for decreasing computational cost are presented in subsections 2.1 and 2.2. In Subsection 2.1 it is shown that due to a certain symmetry of the sinc-quadrature nodes, the number of stationary problems can be reduced almost twice. In Subsection 2.2, it reflects how the choice of integration contour in the complex plane influences the precision of the sinc-quadrature. In

Section 3, we apply the indirect BIE method to stationary elliptic problems. The unknown solution is presented in the form of the double-layer potential, and the BIE of the second kind is obtained. Taking into account that the boundary surface is diffeomorphic to the unit sphere we apply the Nyström method based on the Wienert’s quadrature rules.

Section 4 presents numerical examples to clarify our approach and its optimization.

Before closing this section, we formulate the problem to be studied. Let

be a simply connected region with a smooth boundary

. It is necessary to find function

, which satisfies the heat equation

the initial condition

and the Dirichlet boundary value condition

Assume that the given function

g is bounded, continuous, and satisfies the compatibility condition

.

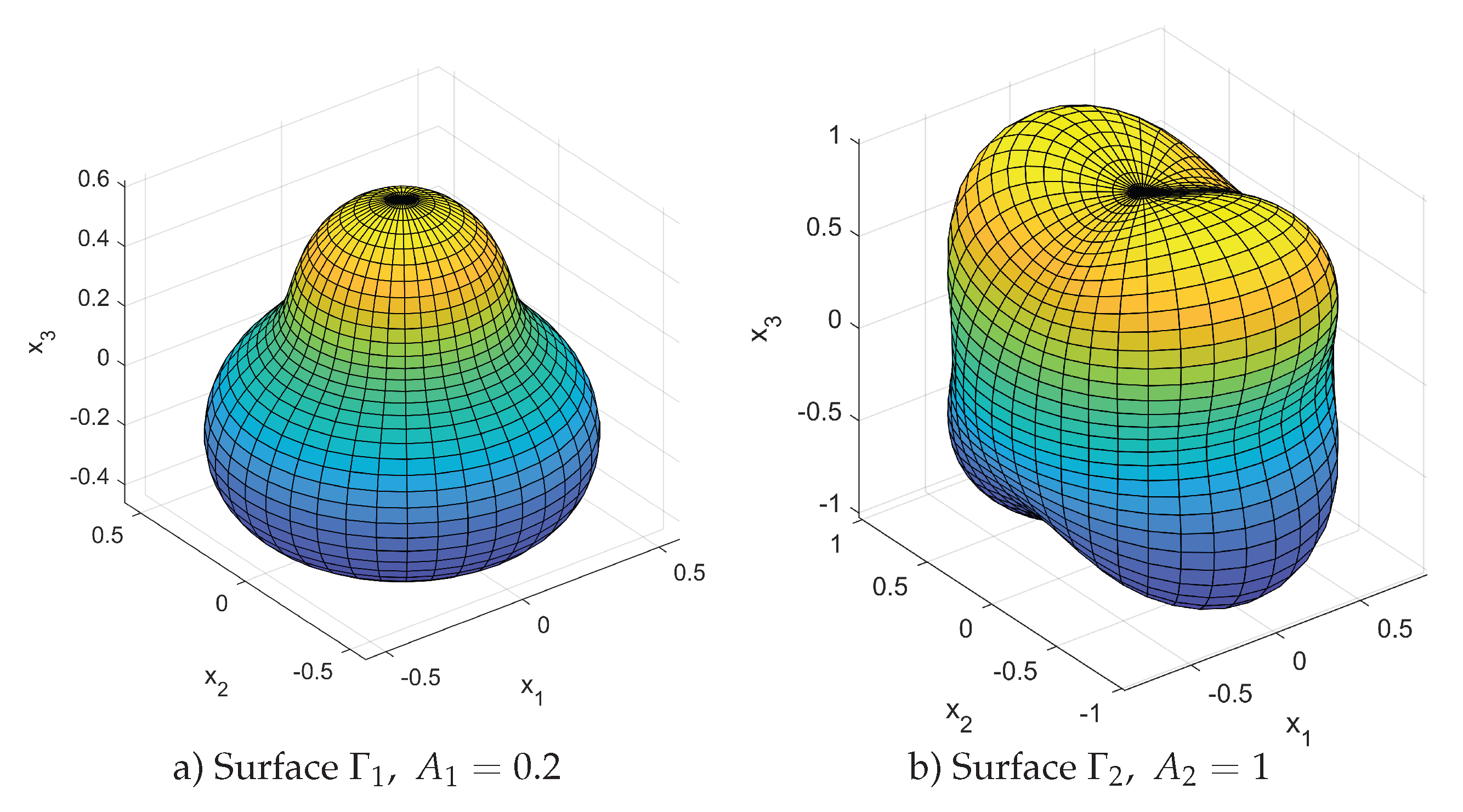

We consider surfaces

, diffeomorphic to the unit sphere

described by an analytic function

with a non zero Jacobian

J.

2. Time Semi-Discretization via Laplace Transform

The Laplace transform of the function

is given by

The integral (

4) is convergent for

, where

is the order of growth of the function

, and

is an analytic function.

For the known image

F the original

f can be reconstructed by using the inverse Laplace transform, described by the Bromwich integral

where

C is the suitable integration contour (see [

8,

10,

11]).

A popular strategy to use the Laplace transform for the heat problems is next:

- 1.

Apply the Laplace transform in time to the initial boundary value problem to obtain boundary value problems for the Helmholtz-type equations.

- 2.

Build an effective solver for stationary problems.

- 3.

Reconstruct time-domain solution via numerical inversion of the Laplace transform.

One approach to approximating the inverse Laplace transform was proposed in [

10]. If

F can be analytically continued to the set

, where

and there exists

such that

then to approximate the inverse Laplace transform of the function

F, a quadrature formula is proposed based on the use of sinc-quadrature for integral (

5) with a special integration contour (see

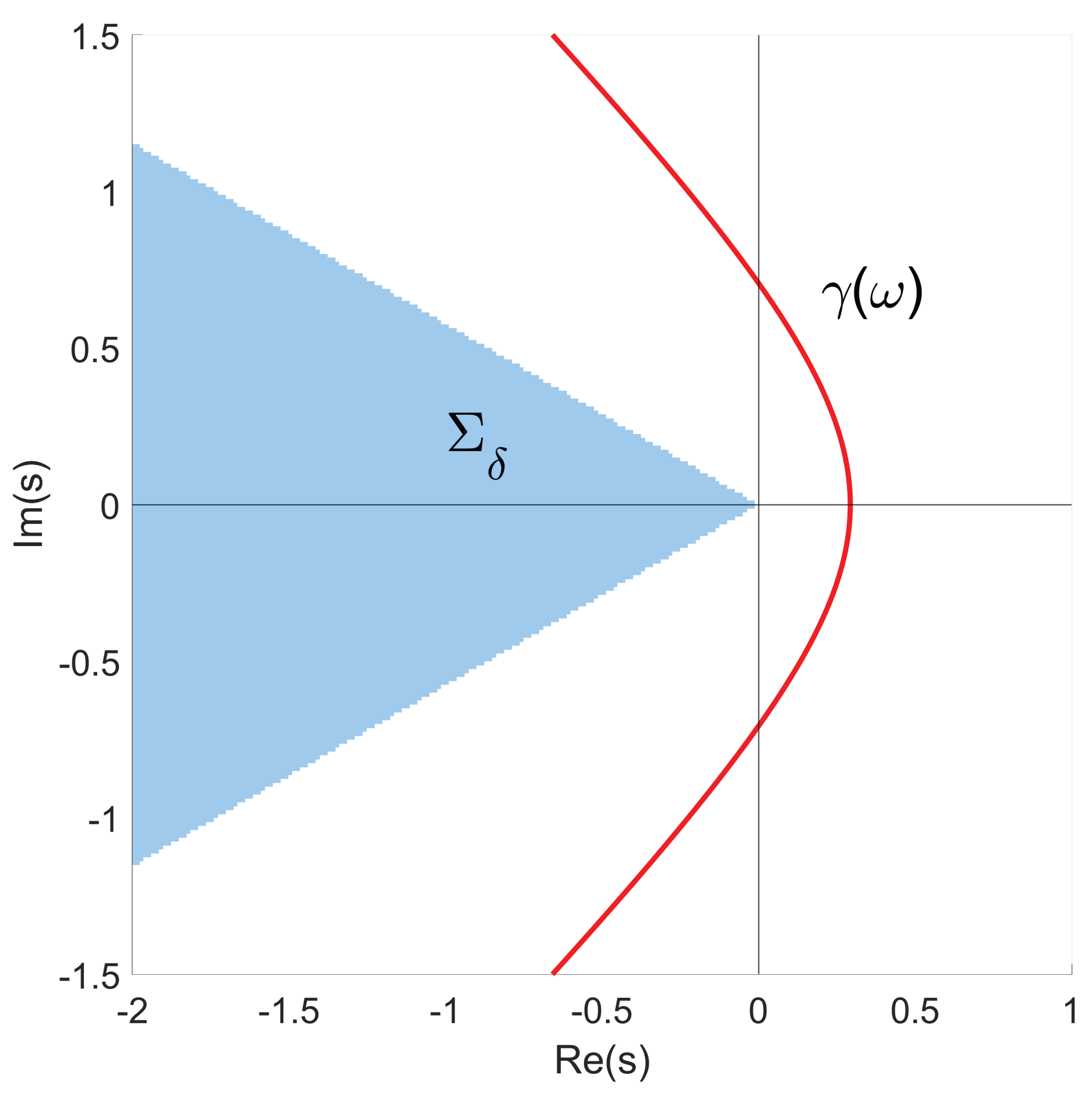

Figure 1)

Here

,

are arbitrary parameters that define the geometry of the contour (

6).

Using contour (

6) to parametrize integral (

5), we obtain

Let

,

,

,

. Integral (

7) can be approximated using the following quadrature formula [

10]

Let us denote

and

, then we obtain

Note, when computing

for different values of

t, one can use the same set of values

. The approximation error of (

9) is shown to behave like

and possess stability to the perturbations of

. This is especially important when values

are computed numerically [

10].

Since the solution of the non-stationary problem (

1)–(

3)

u is bounded with respect to the time variable, i.e., its order of growth is equal to 0, the Laplace transform with respect to time can be applied to both parts of equation (

1). Taking into account property

and zero initial condition, we obtain the following equation for the Laplace image

On the boundary of the domain, the function

satisfies the following condition

where

. Thus, for

we get a boundary value problem (

10)–(

11) for the Helmholtz equation with a complex wavenumber

.

Applying the described approach for the inverse Laplace transform, in order to find an approximate solution of problem (

1)–(

3), it is necessary to compute

that is, to solve a set of

problems (

10)–(

11) for

Here

. It is important to emphasize that problems (

12)–(

13) are independent of each other, enabling their parallel solution.

In [

8,

11] it was shown that the image of the solution to the heat problem

, as a function of the complex argument

s, can be analytically continued to the set

, and there exists a constant

such that

Thus, in our case, we can apply the approach from [

10] and use the contour (

6) for any

and

.

Note, in order to solve problems (

12)–(

13) it is necessary to have boundary functions

, i.e., have the Laplace image

of the original boundary condition

g. If

is not available in a closed form, it can be approximated using various techniques (see [

12,

13,

14]). We leave the approximation of

beyond the scope of the current article and will use examples of

g with a known Laplace transform for the numerical experiments.

Recalling problems (

12)–(

13) are 3D stationary boundary value problems, it is easy to see that solving them numerically may pose a significant computational effort. The main motivation for this article was to suggest certain ideas for decreasing the amount of computational work, as described further.

2.1. Reducing Number of Stationary Problems

It is easy to notice that .

Then

We use the fact that

for any complex

z.

Thus, quadrature nodes (

14) are pairwise conjugate, except for the node

. This allows reducing the solution of the set of

stationary problems to

problems.

Theorem 1.

Let U be a solution of the problem

Then is a solution of the problem

Proof. Statement (d) follows directly from (b). Let us show that (c) follows from (a).

We denote

Then (a) can be written as

Thus

Then

which proves statement (c). □

Corollary 1.

Solutions of the problems(

12)

-(

13)

with indices and j are complex conjugates

Proof. Using a well-known fact

(for real valued

) it is easy to see that the boundary conditions of the problems with indices

and

j are complex conjugates. Since

, it follows from the Theorem 1 the solutions of the problems (

12) - (

13) with indices

and

j are also complex conjugates. □

Thus, it is sufficient to solve the stationary problems for indices , and the solutions for the indices can be obtained automatically from the Corollary 1.

2.2. Integration Contour Parameters Optimization

As mentioned earlier, the integration contour (

6) depends on the parameters

and

. The

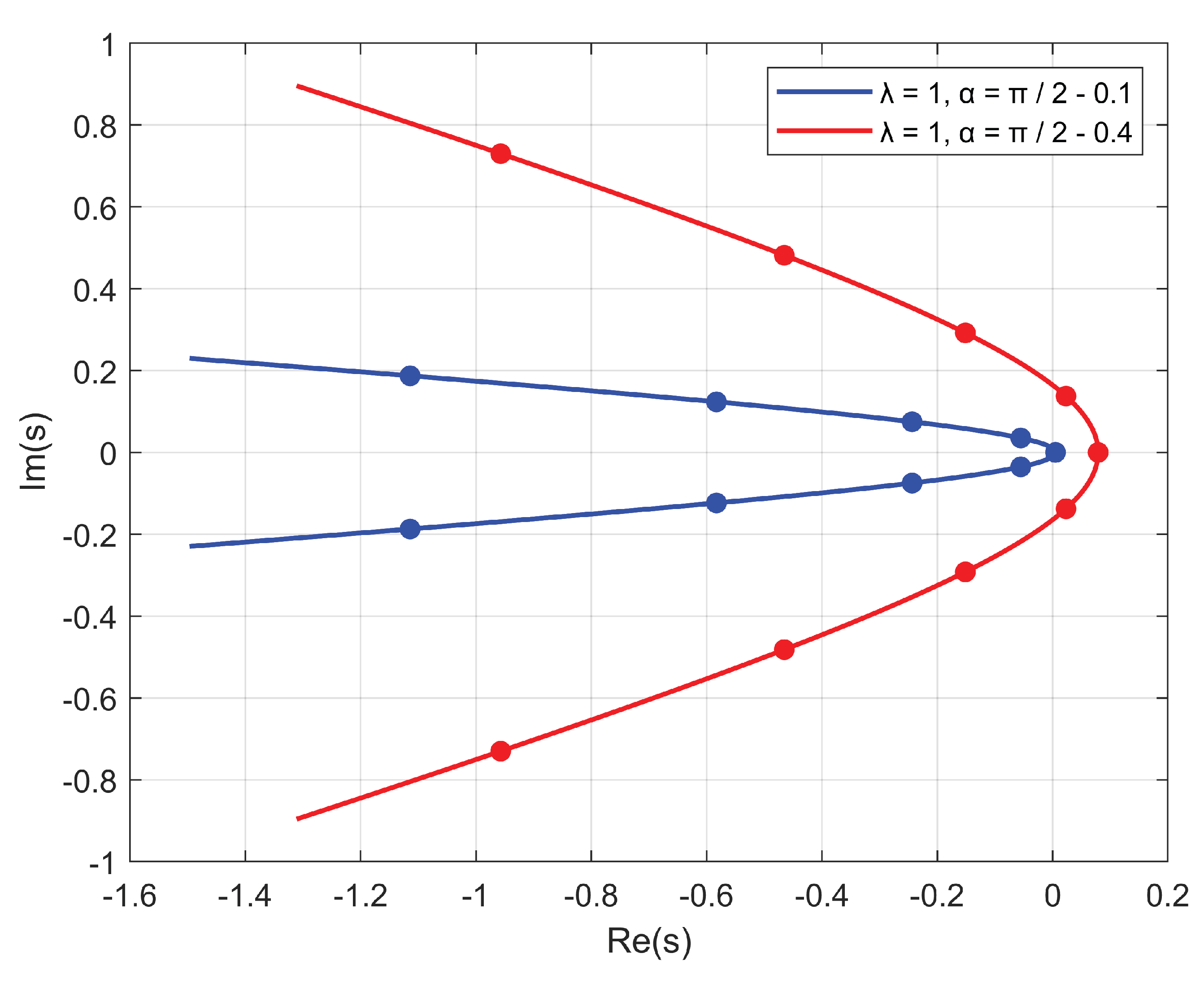

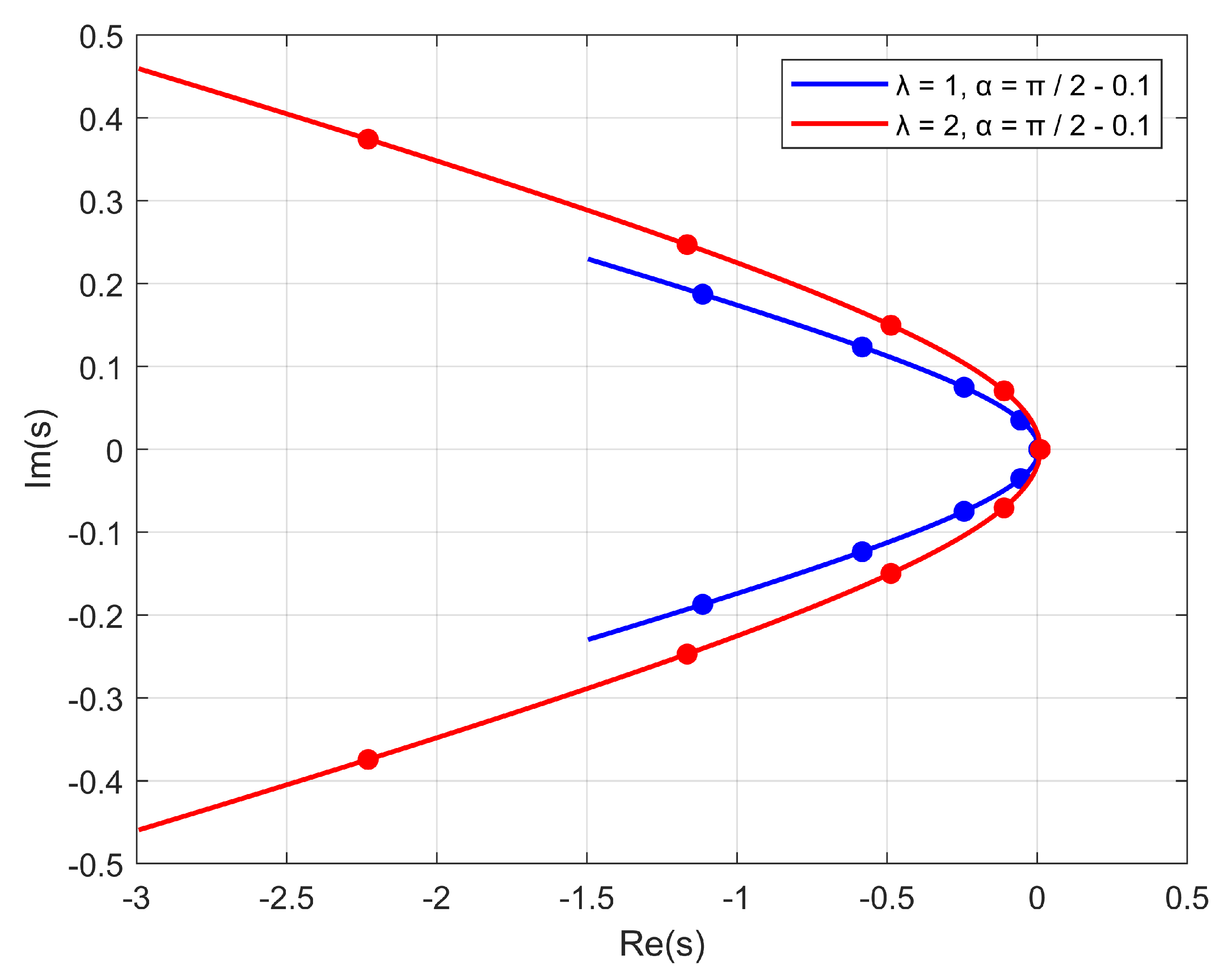

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show the influence of the parameters

and

on the shape of the contour and placement of the nodes for

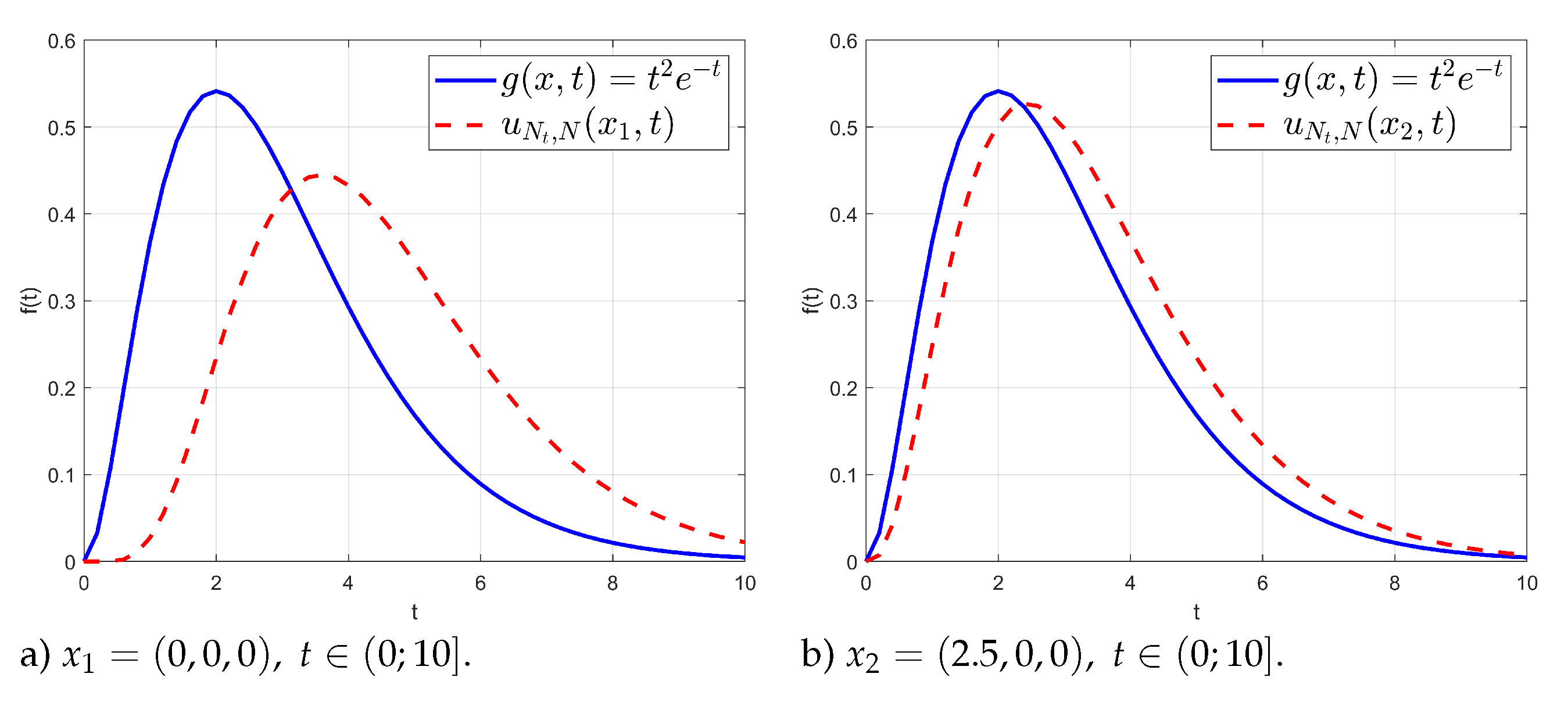

Since the approximate solution of the 3D stationary problems requires a large amount of computations, it makes sense to select the parameters , in such a way as to reduce the expected error.

To find the parameters

,

for which the error is minimized, we will define search intervals for the optimal values of

,

and construct a uniform grid of test values for

We fix certain values of

and select a Laplace transform pair of test functions

and

. It is natural to select

to be similar to the behavior of the boundary condition

g. Then, for each pair of values

, we compute the absolute or relative errors

of the numerical Laplace transform inversion (

9) for

and find the values

for which

Obtained contour parameters are then used to define quadrature nodes and solve stationary problems. We do not provide an explicit recipe to define and . For it seems natural to define close to 0 and close to and thus "scan" most of the interval. For it is empirically observed that increasing stops finding different after certain values of .

3. Stationary Boundary Value Problems Solver

In this section we consider the numerical solution of the stationary problems (

12)–(

13). We will apply the BIE method with later application of the Nyström method based on the quadrature rules for surface integrals, proposed by Wienert [

15].

For brevity, we rewrite problems (

12)–(

13) as

The fundamental solution of the equation (

19) has the form

Since

, it is known that under suitable assumptions on the boundary

and for sufficiently smooth boundary data

, the solution of the Dirichlet problem exists and is unique, see [

16] and references therein. The solution of (

19) can be written in the form of a double layer potential

where

,

is the potential density and

is the unit outward normal vector to

at the point

y.

Potential (

22) is a solution of the problem (

12)–(

13) if the density

is a solution of the Fredholm integral equation of the second kind

For any

equation (

23) has a unique solution

in

[

16].

Since

, we can obtain the parametrized integral equation on

where we denoted

and

The function

K is a weakly singular integral kernel that can be rewritten in the form

where

Note, due to the analyticality of

q well-posedness of (

23) also applies to (

24). In order to discretize (

24), we consider quadrature rules, proposed by Wienert [

15]. For a given space discretization parameter

the following values are defined

where

are the zeros of the Legendre polynomials

[

17].

For a given function approximation is defined as

where

and by

we denote a scalar product of two vectors. Note, the poles are excluded from the continuity requirements, since values of the parametrized functions

at the poles may depend on the direction of approach (i.e. specific value of

) and may be not continous at the poles.

For the non-singular integrands, the following quadrature rule is suggested

For the weakly singular integrands, the following quadrature rule can be used

where

and

Both quadratures are obtained by approximation of the regular part of the integrand via approximation

and then using exact integration. According to results in [

15], these quadrature rules have super-algebraic or even exponential convergence order, depending on the smoothness of

f.

By simple substitution, the quadrature rule (

28) can be extended to a more general case

where

is usually a rotation, such that

, see [

15].

Applying (

29) to the integral in (

24), for

we get an approximation equation

We observe that (

30) contains values of the density

in the rotated nodes

. In order to be able to construct a system of linear equations, we replace

with its approximation by

(

26)

Substituting (

31) back into (

30), we get

where

Collocating the equation (

32) in the nodes

, we get a

system of linear equations for the unknown values

After solving (

33), the approximate solutions of problems (

19)–(

20) for the parameter

can be found by applying the quadrature rule (

27) to (

22)

where

for the parameter value

.

Having solved a set of problems (

19)–(

20), we can construct the approximate solution of the original non-stationary problem (

1)–(

3)

As mentioned, the error rate of the numerical inversion of the Laplace transform behaves like

and is stable to perturbations of

values. In our case these perturbations are created by the fact that

are approximated by

, which in practice exhibits super-algebraic convergence rate for the sufficiently smooth surfaces and boundary conditions. As result, when

and

N are selected in the balanced way, the overall error rate of the original non-stationary problem is super-algebraic, which is shown by the numerical experiments.