1. Introduction

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus belonging to the genus Alphavirus within the Togaviridae family. It is transmitted to humans through the bite of Aedes albopictus or Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, causing Chikungunya fever (CHIKF) [

1]. CHIKV was first isolated in 1953 from a febrile patient in Tanzania [

2]. Prior to 2004, it was only prevalent in Africa and Southeast Asia. In 2004, a CHIKF outbreak broke out in eastern Kenya, and then expanded to the surrounding areas of the Indian Ocean. Currently, it is prevalent in multiple regions including Asia, Africa, Europe, and the United States, affecting millions of people [

3,

4]. According to the World Health Organization's risk assessment, CHIKV has become a potential risk affecting public health [

5].

The CHIKV genome is approximately 11.8 kb in length, with a virion diameter of about 70 nm. It contains two open reading frames (ORFs) encoding four nonstructural proteins (nsP1, nsP2, nsP3, and nsP4) and five structural proteins (C, E3, E2, 6K, and E1) [

6,

7,

8]. Following entry into target cells via endocytosis, CHIKV synthesizes nsP polyproteins from its positive-sense RNA. These polyproteins are subsequently cleaved to form the nsP1-4 replication complex, which facilitates the synthesis of negative-strand RNA [

9]. nsP1 possesses methyltransferase activity involved in mRNA capping [

10], nsP2 and nsP3 function as RNA helicase and replicase, respectively, in viral replication, while nsP4 serves as the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase [

11]. The negative-strand RNA acts as a template for both the genomic RNA and the 26S subgenomic RNA, the latter of which is responsible for structural protein expression. Viral RNA assembles with the nucleocapsid protein (C) to form the viral core, which then buds from the plasma membrane after envelope protein (E) incorporation to produce virions [

12]. The envelope glycoproteins E1 and E2 initially form heterodimers, which subsequently organize into trimeric spikes embedded in the viral envelope, mediating receptor binding, attachment, and membrane fusion [

13]. The E3 protein facilitates pE2 (E2 precursor) folding and stabilizes the E2-E1 spike complex [

14].

Currently, CHIKV is classified into four genotypes: West African (WA), East/Central/South African (ECSA), Asian, and Indian Ocean lineage (IOL) [

15]. The virus is believed to have originated in Central/East Africa approximately 300-500 years ago [

16,

17]. Initially confined to eastern, central, and southern Africa, CHIKV subsequently diverged and spread to other regions [

17,

18]. The divergence between ECSA and Asian lineages occurred around 150 years ago (between 1879 and 1927), leading to multiple outbreaks in Southeast Asia and India [

19]. Notably, the Asian lineage was responsible for the first CHIKV outbreak in the Caribbean in late 2013 [

20], which rapidly spread across Pacific islands and much of the Americas, causing numerous epidemics [

21,

22]. During the 2005-2006 Réunion Island outbreak, the ECSA lineage evolved into the IOL subgenotype [

23].

In 2019, China's Yunnan Province reported its first Asian-genotype CHIKV outbreak, with 88 nucleic acid-positive cases detected, including four with full-genome sequencing [

24]. Reverse genetics technology, which enables direct manipulation of viral genomes in vitro to rapidly synthesize wild-type or mutant strains, has significantly advanced research on viral infection, transmission, and pathogenesis, serving as a crucial tool in virology [

25]. This technology also facilitates the development of live-attenuated vaccines and contributes to serodiagnosis and antiviral screening [

26]. To further investigate the infectivity and pathogenic characteristics of the Asian-genotype CHIKV strain circulating in Yunnan in 2019, we successfully constructed an infectious clone of the 625D6h strain (GenBank: OK316995.1). Using this clone, we analyzed its infection properties in mammalian and mosquito cells and evaluated the antiviral effects of two compounds.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

All mammalian cells, including BHK-21 (baby hamster kidney) cells, Vero (African green monkey kidney) cells, U2-OS (human osteosarcoma) cells, human rhabdomyosarcoma (A-673) cells, and human skeletal muscle cells, were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO₂. The culture medium consisted of DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S, Gibco), 1% glutamine (Glu, Gibco), and non-essential amino acids (NEAA, Gibco). C6/36 Aedes albopictus and Aag2 Aedes Aegypti cells were maintained at 28°C in a 5% CO₂ incubator.

2.2. Construction of Infectious Clone

A modified pSinRep5 plasmid (Invitrogen) was used as the backbone for constructing the CHIKV infectious clone. A T7 promoter sequence was introduced upstream of the 5′ end of the CHIKV cDNA, and a poly(A) tail along with a NotI restriction site was added to the 3′ end. To avoid introducing mutations during cloning, at least two clones of intermediate and final plasmids were selected for full-length sequencing to ensure sequence accuracy.

2.3. Production of Infectious Clone

Stbl3 competent cells were transformed with 0.2 μg of plasmid DNA in 20 μl of competent cells by gentle mixing. After incubation on ice for 30 min, the cells were heat-shocked at 42°C for 90 sec, followed by immediate transfer back to ice for 2-5 min. The transformed cells were then spread onto LB agar plates containing ampicillin (50-100 μg/ml) and incubated at 37°C for 14-16 h. Single colonies were picked and inoculated into 3-4 ml of LB broth with ampicillin, followed by shaking at 200 rpm at 37°C for 14-16 h. Plasmid DNA was extracted using the Qiagen Miniprep Kit. Prior to transcription, the plasmid was linearized with NotI restriction enzyme (New England Biolabs), and the linearized cDNA template was used for in vitro transcription with the mMESSAGE mMACHINE® T7 High-Yield Capped RNA Transcription Kit (Invitrogen).

BHK-21 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 1×10⁵ cells/well and cultured for 12-18 h until 80-90% confluency. For transfection, 2 μg of full-length CHIKV RNA was mixed with 500 μl of Opti-MEM and 4 μl of LipAofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen), incubated at room temperature for 15 min, and then added to the BHK-21 cells. After 6 h, the medium was replaced with fresh DMEM containing 2% FBS. Viral particles were harvested from the supernatant at 36-48 h post-transfection when cytopathic effect (CPE) became evident. The supernatant was clarified by centrifugation, and the virus stock was stored at -80°C.

2.4. Viral Infection

Cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 1×10⁵ cells/well (4×10⁵ cells/well for C6/36, Aag2 cells) and incubated overnight. The cells were then infected with the CHIKV infectious clone (MOI = 1) in DMEM with 2% FBS (MEM for C6/36, Aag2 cells). After 2 h of incubation at 37°C (28°C for C6/36 cells), the cells were washed once with PBS and maintained in fresh medium with 2% FBS. Supernatants were collected at indicated time points for viral titer determination by plaque assay.

2.5. Plaque Assay

Vero cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 1×10⁵ cells/well. Overnight, serial 10-fold dilutions of viral samples were prepared in DMEM with 2% FBS, and the cells were infected at 37°C for 2 h. After removing the inoculum, the cells were overlaid with DMEM containing 1.3% carboxymethyl cellulose (FUJIFILM Wako) and 2% FBS. Two days later, the cells were fixed with formaldehyde and stained with 1% crystal violet to visualize plaques. Viral titers were calculated as plaque-forming units per milliliter (PFU/ml).

2.6. Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA)

Cells were seeded in 24- or 96-well plates and infected (MOI = 1) when reaching 80-100% confluency. At 24 h post-infection, the cells were fixed with methanol (100 μl/well for 96-well plates; 350 μl/well for 24-well plates) at -20°C for 30 min. After fixation, the cells were blocked with 3% BSA at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with primary antibody (diluted in 3% BSA) for 90 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated with secondary antibody (Invitrogen, diluted in 3% BSA) for 60 min in the dark. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (1:5000 in PBS) for 15 min. Fluorescence images were captured using a fluorescence microscope.

2.7. Viral Replication Kinetics

Monolayers of BHK-21, U2-OS, C6/36 or other cells were infected (MOI = 1). After 2 h of adsorption, the cells were washed with PBS and maintained in fresh medium with 2% FBS. Supernatants were collected at 0, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h post-infection for viral titer determination by plaque assay.

2.8. Evaluation of Antiviral Compounds

Vero cells were seeded in 96-well plates (1×10⁴ cells/well) and infected (MOI = 1) with virus pre-mixed with test compounds (final concentration 40 μM). After 2 h, the inoculum was replaced with maintenance medium containing 40 μM compound. At 24 h post-infection, supernatants were collected for viral titer measurement, and infected cells were analyzed by IFA.

2.9. Data Analysis

Viral titers were determined from at least three independent experiments and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 10.0, with Student’s test used for comparisons. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Generation of CHIKV Infectious Clone

The synthesized full-genome cDNA fragment of 625D6h was inserted into the pSinRep5 vector, with the T7 promoter located upstream of the viral cDNA (

Figure 1a). Sequencing analysis of the construct pSinRep5-625D6h showed complete consistency with the sequence of the 625D6h strain in GenBank [

24] (Accession No.: MG664851.1). The constructed plasmid (

Figure 1b) and the RNA obtained by in vitro transcription (

Figure 1c) were verified by gel electrophoresis, with sizes matching the expected results.

The pSinRep5-625D6h construct (2 μg) was transfected into BHK-21 cells in a 24-well plate, and the culture supernatant was harvested 48 h post-transfection. To confirm the successful generation of the 625D6h infectious clone, the clone was inoculated onto Vero cells, and the plaque morphology observed after 2 days is shown in

Figure 1d. Additionally, the supernatant obtained from transfection was used to infect Vero cells, and obvious CPE were observed at 48 h post-infection, while the mock cells remained normal in morphology (

Figure 1e).

An IFA was also performed. The infected cells were stained with virus-specific primary antibodies, followed by corresponding secondary antibodies (green) and DAPI for nuclear staining (blue). As shown in

Figure 1f, green fluorescence signals were detected in cells infected with the supernatant derived from transfection of 625D6h RNA, whereas no signals were observed in the mock group. The plaque morphology formed by the infectious clone in Vero cells 2 d post-inoculation is shown in

Figure 1f. These results demonstrate that the plasmid containing the full-length genome of the 625D6h strain can generate CHIKV infectious clones through in vitro transcription followed by transfection into BHK-21 cells.

3.2. Replication of Infectious Clone in Mammalian Cell Lines

We evaluated the replication efficiency of the CHIKV 625D6h infectious clone in adherent mammalian cell lines. The tested cells were seeded at 5×10⁵ cells/well in 24-well plates and incubated overnight before infection with the 625D6h infectious clone at an MOI of 1. Viral titers in the culture supernatant were determined by plaque assay. The results showed that in BHK-21 cells, the viral titer peaked at 24 h post-infection, reaching approximately 2.6×10⁵ PFU/ml (

Figure 2a). U2-OS cells supported viral replication up to 48 post-infection, with the titer peaking at 36 hpi (2.8×10⁵ PFU/ml) (

Figure 2b). While the virus titres were lower for Human sceletal muscle myoblasts and A-673 cells.

To visualize viral infection, BHK-21 and U2-OS cells were infected with the virus at an MOI of 1, and immunofluorescence staining was performed at 24 h post-infection. Green fluorescent signals were observed in the infected cells (

Figure 3), confirming the successful construction of the infectious clone. Under optical microscopy, extensive cell death was observed in BHK-21 cells infected with 625D6h, consistent with previous reports that CHIKV infection induces significant cytopathic effects in mammalian cells [

27,

28].

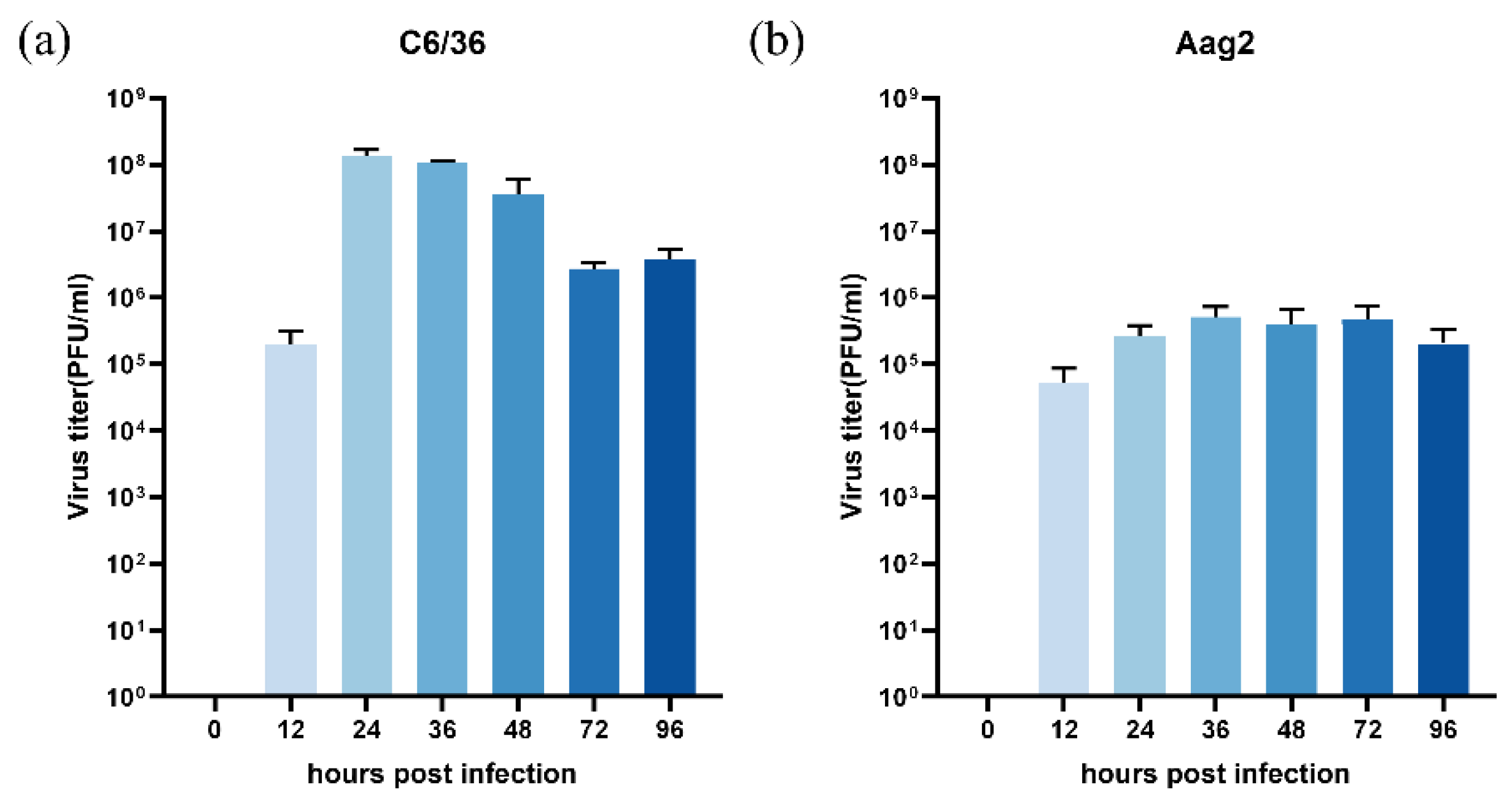

3.3. Evaluation of Replication Efficiency in C6/36 and Aag2 Cells

To assess the replication of the CHIKV clone in the C6/36

Aedes albopictus cells and Aag2

Aedes Aegypti cells, cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 1×10⁶ cells/well. After overnight incubation, they were infected with 625D6h at an MOI of 1. Supernatants were collected at multiple time points, and viral titers were determined by plaque assay. The results demonstrated efficient replication of 625D6h, with the highest titer (10⁸ PFU/ml) reached at 36 h post-infection, followed by a gradual decline over 3-4 days (

Figure 4a), while the highest titer were less than 10

6 PFU/ml for Aag2 cells (

Figure 4b). Unlike in mammalian cells, optical microscopy observation showed that CHIKV infection in C6/36 and Aag2 cells did not induce significant (CPE) [

28].

3.4. Evaluation of Antiviral Compound Efficacy

Our previous studies identified two dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) inhibitors, ML390 and vidofludimus, which exhibited significant antiviral effects against West Nile virus [

29]. Given the crucial role of DHODH in viral nucleic acid replication, we hypothesized that these compounds might also inhibit CHIKV replication. To test this hypothesis, we conducted in vitro antiviral assays using sorafenib, a known anti-CHIKV compound, as a positive control [

30]. The results demonstrated that compared to the control group, both ML390 and vidofludimus treatment groups showed a significant reduction in viral fluorescence signal intensity (

P-value < 0.05). These findings indicate that DHODH inhibitors vidofludimus and ML390 can effectively suppress CHIKV replication, further supporting the potential of DHODH as an antiviral target.This discovery provides important experimental evidence for the development of novel antiviral drugs against CHIKV.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of 625D6h replication by ML390 and vidofludimus. Cells were infected at an MOI of 0.1, and viral replication was assessed at 24 h post-infection using Immunofluorescence assays.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of 625D6h replication by ML390 and vidofludimus. Cells were infected at an MOI of 0.1, and viral replication was assessed at 24 h post-infection using Immunofluorescence assays.

4. Discussion

The CHIKV strain 625D6h was isolated in 2019 from a dengue-like febrile patient at the People's Hospital of Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan Province, China. Whole-genome sequencing and evolutionary analysis revealed that this strain belongs to the Asian genotype and is most closely related to the SZ1239 strain (GenBank: MG664851.1), which was isolated in July 2012 from an imported chikungunya case (originating from Southeast Asia) in Shenzhen. The nucleotide homology between the two strains reached 99.2%. Compared to the SZ1239 strain, the 625D6h strain has accumulated 25 amino acid mutations distributed across viral nonstructural proteins (nsp1: 3, nsp2: 5, nsp3: 2, nsp4: 5) and structural proteins (capsid protein C: 1, envelope protein E3: 1, E2: 5, E1: 3), suggesting that this strain may have undergone host-adaptive evolution.

To explore the biological significance of these mutations, this study constructed an infectious clone of the 625D6h strain. In vitro experiments showed that this clone exhibited limited replication levels in mammalian cell lines (such as Vero or BHK-21) but was accompanied by significant cytopathic effects (CPE). In contrast, viral replication efficiency was significantly enhanced in C6/36 cells derived from Aedes albopictus. This differential phenotype suggests that the 625D6h strain may have acquired an adaptive advantage for mosquito vector cells.

Further analysis of the potential functions of the mutation sites revealed that the five mutations in the E2 protein (e.g., L210Q, K252Q, etc.) are located near known mosquito receptor-binding domains, while the three mutations in the E1 protein (e.g., V156A, K211T, etc.) are associated with membrane fusion functions. These mutations may have synergistic effects with previously reported host-adaptive mutations (e.g., E1-A226V, E2-L210Q). Previous studies have confirmed that the E1-A226V mutation enhances CHIKV infectivity in

Aedes albopictus, while secondary mutations (e.g., E2-K252Q or nsP2-L539S) can further optimize viral fitness [

31,

32,

33]. Although the 625D6h strain does not carry the classic A226V mutation, its unique combination of mutations (e.g., E2-R198Q/E3-S18F or multiple mutations in the nsp4 region) may mediate adaptive evolution to

Aedes albopictus in Yunnan by altering viral particle stability or replication efficiency.

In summary, this study is the first to report the molecular characteristics of the locally circulating CHIKV strain 625D6h in southwestern China. Its high replication efficiency under mosquito-adaptive conditions may have contributed to the outbreak in 2019. Currently, we are constructing an infectious clone of the parental strain SZ1239 to compare the biological properties of the two strains using reverse genetics, aiming to clarify the contribution of key mutations to host switching.

This study provides an in-depth exploration of the molecular characteristics and host-adaptive mechanisms of the CHIKV Yunnan epidemic strain 625D6h, which has significant public health implications. The following discussion expands on multiple perspectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T. and H.R.; methodology, X.N, B.X. and Z.C. visualization, L.Z and F.M. writing-original draft preparation, X.N., B.X. and H.T.; writing-review and editing, H.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC2602901, 2022YFC2602903).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have declared no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

References

- Handler, M.Z.; Handler, N.S.; Stephany, M.P.; Handler, G.A.; Schwartz, R.A. Chikungunya fever: an emerging viral infection threatening North America and Europe. Int J Dermatol, 2017. 2, e19-e25. [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.W. The Newala epidemic. III. The virus: isolation, pathogenic properties and relationship to the epidemic. J Hyg (Lond), 1956. 2, 177-91. [CrossRef]

- Weaver, S.C.; Forrester, N.L. Chikungunya: Evolutionary history and recent epidemic spread. Antiviral Res, 2015. 120, 32-39. [CrossRef]

- de Souza, W.M.; Ribeiro, G.S.; de Lima, S.T.; de Jesus, R.; Moreira, F.R.; Whittaker, C.; Sallum, M.A.; Carrington, C.V.; Sabino, E.C.; Kitron, U.; et al. Chikungunya: a decade of burden in the Americas. Lancet Reg Health Am, 2024. 30, 100673. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Geographical expansion of cases of dengue and chikungunya beyond the historical areas of transmission in the Region of the Americas. https://wwwwhoint/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON448. 23 March 2023.

- Godaert, L.; Najioullah, F.; Bartholet, S.; Colas, S.; Yactayo, S.; Cabié, A.; Fanon, J.L.; Césaire, R.; Dramé, M. Atypical Clinical Presentations of Acute Phase Chikungunya Virus Infection in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2017. 11, 2510-2515. [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Ge, N.; Cao, Y.; Sun, J.; Jin, X. Recent progress on chikungunya virus research. Virol Sin, 2017. 6, 441-453. [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Yin, P.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, N.; Jian, X.; Song, S.; Gao, S.; Zhang, L. Intraviral interactome of Chikungunya virus reveals the homo-oligomerization and palmitoylation of structural protein TF. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2019. 4, 919-924. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, O.; Albert, M.L. Biology and pathogenesis of chikungunya virus. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2010. 7, 491-500. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Jain, R. Neurological Manifestations of Chikungunya in Children. Indian Pediatr, 2017. 3, 249. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Tong, X.; Xiaoyan, L. Molecular variation and epidemiology of the Chikungunya virus . China Tropical Medicine, 2021. 8, 809-813. [CrossRef]

- Weaver, S.C.; Lecuit, M. Chikungunya virus and the global spread of a mosquito-borne disease. N Engl J Med, 2015. 13, 1231-1239. [CrossRef]

- Gorchakov, R.; Wang, E.; Leal, G.; Forrester, N.L.; Plante, K.; Rossi, S.L.; Partidos, C.D.; Adams, A.P.; Seymour, R.L.; Weger, J.; et al. Attenuation of Chikungunya virus vaccine strain 181/clone 25 is determined by two amino acid substitutions in the E2 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol, 2012. 11, 6084-6096. [CrossRef]

- Jose, J.; Snyder, J.E; Kuhn, R.J. A structural and functional perspective of alphavirus replication and assembly. Future Microbiol, 2009. 7, 837-856. [CrossRef]

- Hakim, M.S.; Annisa, L.; Gazali, F.M.; Aman, A.T. The origin and continuing adaptive evolution of chikungunya virus. Arch Virol, 2022.12, 2443-2455. [CrossRef]

- Cherian, S.S.; Walimbe, A.M.; Jadhav, S.M.; Gandhe, S.S.; Hundekar, S.L.; Mishra, A.C.; Arankalle, V.A. Evolutionary rates and timescale comparison of Chikungunya viruses inferred from the whole genome/E1 gene with special reference to the 2005-07 outbreak in the Indian subcontinent. Infect Genet Evol, 2009. 1, 16-23. [CrossRef]

- Volk, S.M.; Chen, R.; Tsetsarkin, K.A.; Adams, A.P.; Garcia, T.I.; Sall, A.A.; Nasar, F.; Schuh, A.J.; Holmes, E.C.; Higgs, S.; et al. Genome-scale phylogenetic analyses of chikungunya virus reveal independent emergences of recent epidemics and various evolutionary rates. J Virol, 2010. 13, 6497-6504. [CrossRef]

- Deeba, F.; Haider, M.S.H.; Ahmed, A.; Tazeen, A.; Faizan, M.I.; Salam, N.; Hussain, T.; Alamery, S.F.; Parveen S. Global transmission and evolutionary dynamics of the Chikungunya virus. Epidemiol Infect, 2020. 148, e63. [CrossRef]

- Ng, L.C.; Hapuarachchi, H.C. Tracing the path of Chikungunya virus--evolution and adaptation. Infect Genet Evol, 2010. 7, 876-885. [CrossRef]

- Leparc-Goffart, I.; Nougairede, A.; Cassadou, S.; Prat, C.; de Lamballerie, X. Chikungunya in the Americas. Lancet, 2014. 9916, 514. [CrossRef]

- Sam, I.C.; Kümmerer, B.M.; Chan, Y.F.; Roques, P.; Drosten, C.; AbuBakar, S. Updates on chikungunya epidemiology, clinical disease, and diagnostics. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis, 2015. 4, 223-230. [CrossRef]

- Alto, B.W.; Wiggins, K.; Eastmond, B.; Velez, D.; Lounibos, L.P.; Lord, C.C. Transmission risk of two chikungunya lineages by invasive mosquito vectors from Florida and the Dominican Republic. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2017. 7, e0005724. [CrossRef]

- van Duijl-Richter, M.K.; Hoornweg, T.E.; Rodenhuis-Zybert, I.A.; Smit, J.M. Early Events in Chikungunya Virus Infection-From Virus Cell Binding to Membrane Fusion. Viruses, 2015. 7, 3647-3674. [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.; Su, C.; Li, T.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Luan, N.; Ma, D.; Liu, J.; Sun, Q.; Peng, X.; et al. Genetic Characterization of Chikungunya Virus Among Febrile Dengue Fever-Like Patients in Xishuangbanna.; Southwestern Part of China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2022. 12, 914289. [CrossRef]

- Aubry, F.; Nougairède, A.; Gould, E.A.; de Lamballerie X. Flavivirus reverse genetic systems, construction techniques and applications: a historical perspective. Antiviral Res, 2015. 114, 67-85. [CrossRef]

- Stobart, C.C.; Moore M.L. RNA virus reverse genetics and vaccine design. Viruses, 2014. 7, 2531-2350. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang,, Y.; Wang, M.; Yang, F.; Wu, C.; Huang, D.; Xiong, L.; Wan, C.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, R. Differences in genome characters and cell tropisms between two chikungunya isolates of Asian lineage and Indian Ocean lineage. Virol J, 2018. 1, 130. [CrossRef]

- Wikan, N.; Sakoonwatanyoo, P.; Ubol, S.; Yoksan, S.; Smith, D.R. Chikungunya virus infection of cell lines: analysis of the East, Central and South African lineage. PLoS One, 2012. 1, e31102. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Liu, Y.; Ren, R.; Liu, Y.; He, Y.; Qi, Z.; Peng, H.; Zhao, P. Identification of clinical candidates against West Nile virus by activity screening in vitro and effect evaluation in vivo. J Med Virol, 2022. 10, 4918-4925. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Pan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Peng, H.; Zhao, P.; Qi, Z.; Liu, Y.; Tang, H. Identification of tyrphostin AG879 and A9 inhibiting replication of chikungunya virus by screening of a kinase inhibitor library. Virology, 2023. 588, 109900. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Sharma, A.K.; Sukumaran, D.; Parida, M.; Dash, P.K. Two novel epistatic mutations (E1:K211E and E2:V264A) in structural proteins of Chikungunya virus enhance fitness in Aedes aegypti. Virology, 2016. 497, 59-68. [CrossRef]

- Rangel, M.V.; McAllister, N.; Dancel-Manning, K.; Noval, M.G.; Silva, L.A.; Stapleford, K.A. Emerging Chikungunya Virus Variants at the E1-E1 Interglycoprotein Spike Interface Impact Virus Attachment and Inflammation. J Virol, 2022. 4, e0158621. [CrossRef]

- Tsetsarkin, K.A.; Chen, R.; Yun, R.; Rossi, S.L.; Plante, K.S.; Guerbois, M.; Forrester, N.; Perng, G.C.; Sreekumar, E.; Leal, G.; et al. Multi-peaked adaptive landscape for chikungunya virus evolution predicts continued fitness optimization in Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. Nat Commun, 2014. 5, 4084. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).