Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

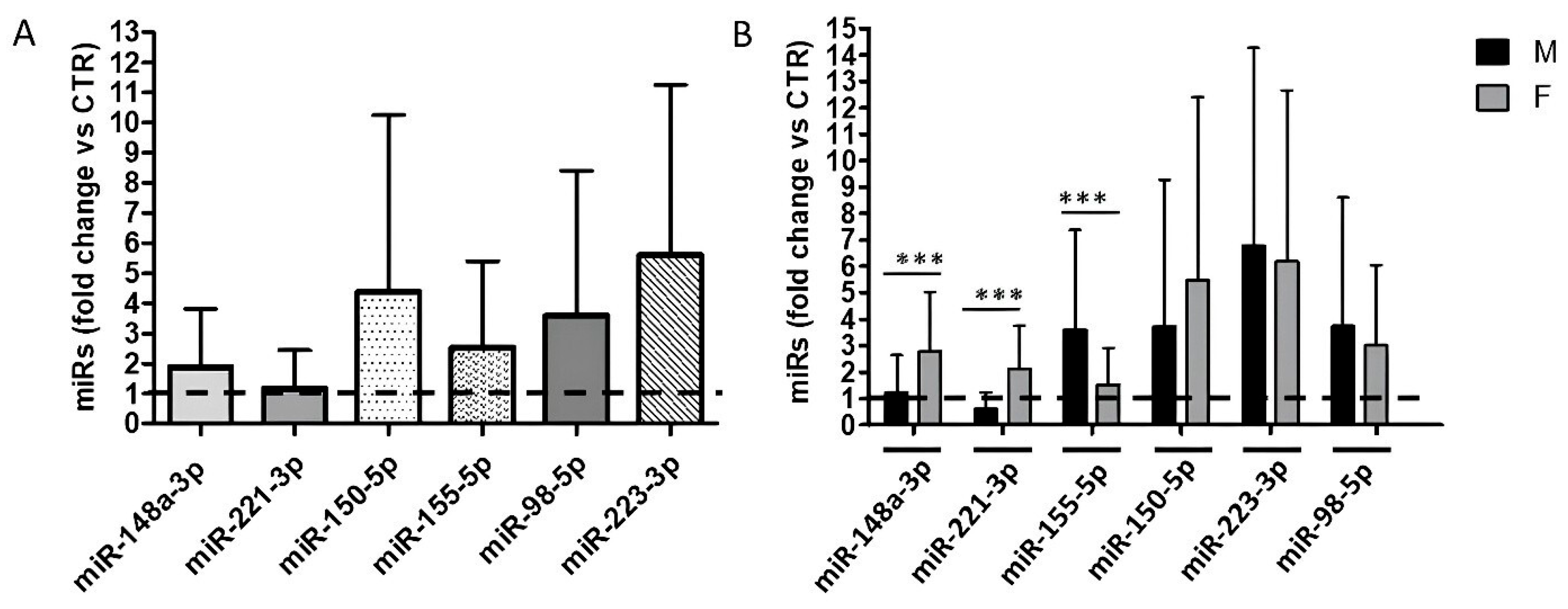

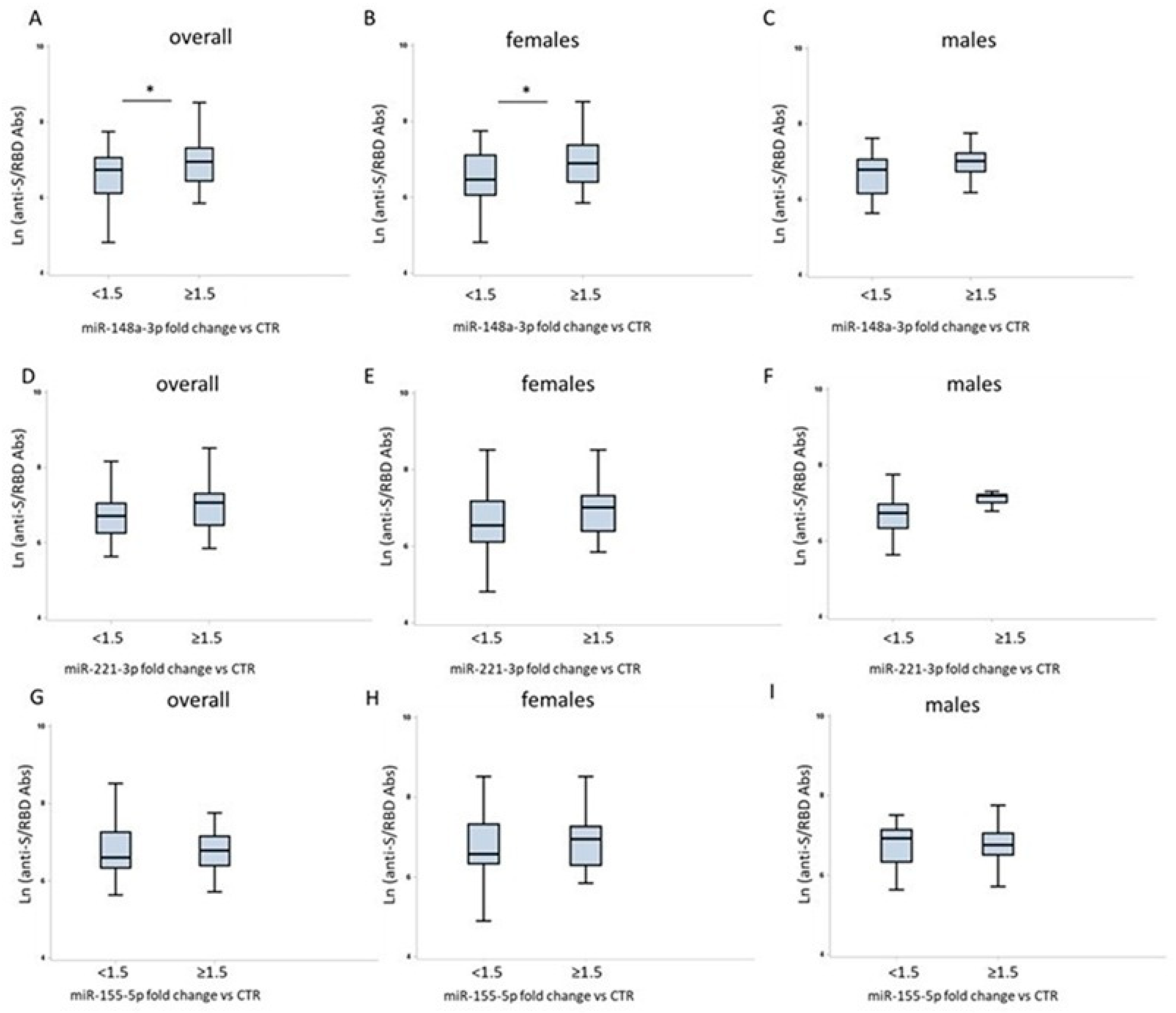

2. Results

2.1. Description of the Study Population

2.2. Sex Differences in Humoral Response to COVID-19 Vaccination

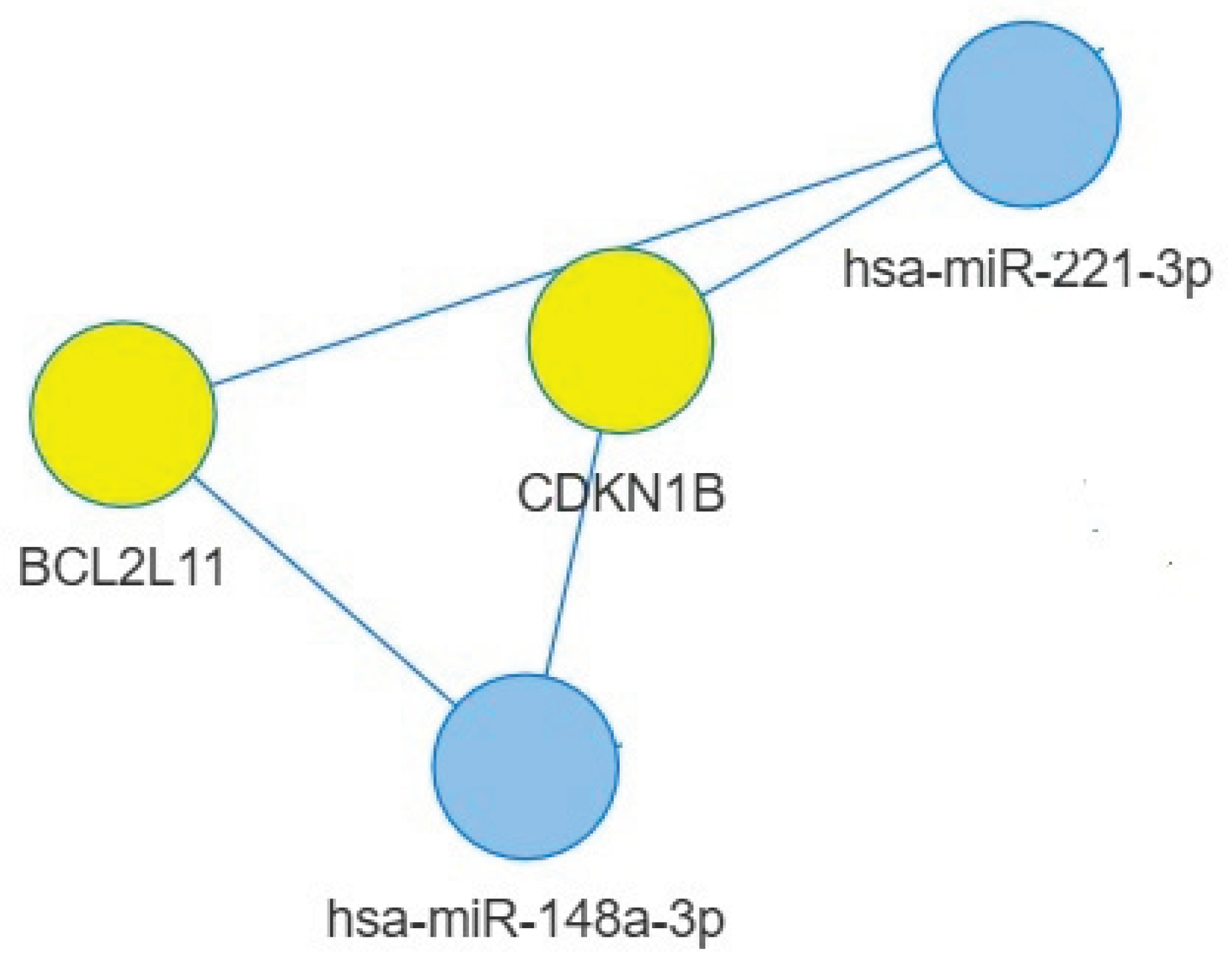

2.4. Targets of miR-148a-3p

2.5. Targets of miR-221-3p and miR-155-5p

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Population and Study Design

4.2. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis and Quantitative Analysis by qRT-PCR of the Selected microRNAs

4.3. Statistical Analyses

4.4. MicroRNA-Target Interaction Network

4.5. Functional Enrichment Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gote, V.; Bolla, P.K.; Kommineni, N.; Butreddy, A.; Nukala, P.K.; Palakurthi, S.S.; Khan, W. A Comprehensive Review of mRNA Vaccines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, M.; Gültekin, N; Stanga, Z, Fehr, J. S.; Ülgür, I.I.; Schlagenhauf, P. Disparities in response to mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines according to sex and age: A systematic review. New Microbes New Infect. 2024, 63, 101551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, M.; Yun, S.G.; Kim, S.; Kim, C.G.; Cha, J.H.; Lee, C.; Kang, S.; Park, S.G.; Kim, S.B.; Lee, K.; et al. Humoral and Cellular Immune Responses to Vector, Mix-and-Match, or mRNA Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 and the Relationship between the Two Immune Responses. Microbiol Spectr. 2022, 10, e02495–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Shunmuganathan, B.; Qian, X.; Gupta, R.; Tan, R.S.W.; Kozma, M.; Purushotorman, K.; Murali, T.M.; Tan, N.Y.J.; Preiser, P.R.; et al. Employment of a high throughput functional assay to define the critical factors that influence vaccine induced cross-variant neutralizing antibodies for SARS-CoV-2. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 21810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anticoli, S.; Dorrucci, M.; Iessi, E.; Chiarotti, F.; Di Prinzio, R. R.; Vinci, M. R.; Zaffina, S.; Puro, V.; Colavita, F.; Mizzoni, K.; et al. Association between sex hormones and anti-S/RBD antibody responses to COVID-19 vaccines in healthcare workers. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023, 19, 2273697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tilbeurgh, M.; Lemdani, K.; Beignon, A.S.; Chapon, C.; Tchitchek, N.; Cheraitia, L.; Marcos Lopez, E.; Pascal, Q.; Le Grand, R.; Maisonnasse, P.; et al. Predictive Markers of Immunogenicity and Efficacy for Human Vaccines. Vaccines 2021, 9, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atherton, L.J.; Jorquera, P.A.; Bakre, A.A.; Tripp, R.A. Determining Immune and miRNA Biomarkers Related to Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Vaccine Types. Front Immunol. 2019, 10, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-P.; Hsieh, Y.-S.; Cheng, M.-H.; Shen, C.-F.; Shen, C.-J.; Cheng, C.-M. Using MicroRNA Arrays as a Tool to Evaluate COVID-19 Vaccine Efficacy. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Xu, X.; Xiao, L.; Wang, L.; Qiang, S. The Role of microRNA in the Inflammatory Response of Wound Healing. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 852419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaál, Z. Role of microRNAs in Immune Regulation with Translational and Clinical Applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Palo, A.; Siniscalchi, C.; Salerno, M.; Russo, A.; Gravholt, C.H.; Potenza, N. What microRNAs could tell us about the human X chromosome. Cell Mol Life Sci 2020, 77, 4069–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyashita, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Takagi, Y.; Tsukamoto, H.; Takashima, K.; Kouwaki, T.; Makino, K.; Fukushima, S.; Nakamura, K.; Oshiumi, H. Circulating extracellular vesicle microRNAs associated with adverse reactions, proinflammatory cytokine, and antibody production after COVID-19 vaccination. NPJ Vaccines 2022, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Candia, P.; Torri, A.; Gorletta, T.; Fedeli, M.; Bulgheroni, E.; Cheroni, C.; Marabita, F.; Crosti, M.; Moro, M.; Pariani, E.; et al. Intracellular modulation, extracellular disposal and serum increase of MiR-150 mark lymphocyte activation. PLoS One 2013, 8, e75348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haralambieva, I.H.; Ratishvili, T.; Goergen, K.M.; Grill, D.E.; Simon, W.L.; Chen, J.; Ovsyannikova, I.G.; Poland, G.A.; Kennedy, R.B. Effect of lymphocyte miRNA expression on influenza vaccine-induced immunity. Vaccine 2025, 55, 127023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, W.; Ni, J. Increased serum microRNA-155 level associated with nonresponsiveness to hepatitis B vaccine. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013, 20, 1089–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralambieva, I.H.; Kennedy, R.B.; Simon, W.L.; Goergen, K.M.; Grill, D.E.; Ovsyannikova, I.G.; Poland, G.A. Differential miRNA expression in B cells is associated with inter-individual differences in humoral immune response to measles vaccination. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0191812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianello, E.; Persson, J.; Andersson, B.; van Veen, S.; Dias, T.L.; Santoro, F.; Östensson, M.; Obudulu, O.; Agbajogu, C.; Torkzadeh, S. Global blood miRNA profiling unravels early signatures of immunogenicity of Ebola vaccine rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP. iScience 2023, 26, 108574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Licursi, V.; Conte, F.; Fiscon, G.; Paci, P. MIENTURNET: an interactive web tool for microRNA-target enrichment and network-based analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2019, 20, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.D.; Kim, M.S. Exposure to a mixture of heavy metals induces cognitive impairment: Genes and microRNAs involved. Toxicology 2022, 471, 153164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigton, E.J.; Mikami, Y.; McMonigle, R.J.; Castellanos, C.A.; Wade-Vallance, A.K.; Zhou, S.K.; Kageyama, R.; Litterman, A.; Roy, S.; Kitamura, D.; et al. MicroRNA-directed pathway discovery elucidates an miR-221/222-mediated regulatory circuit in class switch recombination. J Exp Med. 2021, 218, e20201422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh, A.; Naseri, A.; Shojaie, L.; Nemati, M.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Bannazadeh Baghi, H.; Hamblin, M.R.; Akhlagh, S.A.; Mirzaei, H. MicroRNA-155 and antiviral immune responses. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021, 101(Pt A), 108188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiumi, H. Circulating Extracellular Vesicles Carry Immune Regulatory miRNAs and Regulate Vaccine Efficacy and Local Inflammatory Response After Vaccination. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 685344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, Y.; Ishikawa, K.; Fukushima, Y.; Kouwaki, T.; Nakamura, K.; Oshiumi, H. Immune-regulatory microRNA expression levels within circulating extracellular vesicles correspond with the appearance of local symptoms after seasonal flu vaccination. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberger, C.M.; Podyminogin, R.L.; Navarro, G.; Zhao, G.W.; Askovich, P.S.; Weiss, M.J.; Aderem, A. miR-451 Regulates Dendritic Cell Cytokine Responses to Influenza Infection. J Immunol. 2012, 189, 5965–5975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Eghbali, M. Influence of sex differences on microRNA gene regulation in disease. Biol Sex Differ. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.; Cui, C.; Cui, Q. Identification and Analysis of Sex-Biased MicroRNAs in Human Diseases. Genes 2023, 14, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klinge, C.M. miRNAs regulated by estrogens, tamoxifen, and endocrine disruptors and their downstream gene targets. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015, 418 Pt 3(0 3), 273–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhan, Z.; Xu, L.; Ma, F.; Li, D.; Guo, Z.; Li, N.; Cao, X. MicroRNA-148/152 Impair Innate Response and Antigen Presentation of TLR-Triggered Dendritic Cells by Targeting Camkiiα. J Immunol. 2010, 185, 7244–7251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pracht, K.; Meinzinger, J.; Schulz, S.R.; Daum, P.; Côrte-Real, J.; Hauke, M.; Roth, E.; Kindermann, D.; Mielenz, D.; Schuh, W.; et al. miR-148a controls metabolic programming and survival of mature CD19-negative plasma cells in mice. Eur J Immunol. 2021, 51, 1089–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, T.; Takayama, K.; Katayama, S.; Urano, T.; Horie-Inoue, K.; Ikeda, K.; Takahashi, S.; Kawazu, C.; Hasegawa, A.; Ouchi, Y.; et al. miR-148a is an androgen-responsive microRNA that promotes LNCaP prostate cell growth by repressing its target CAND1 expression. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; He, H.; Chen, Q.; Yue, W. GPER mediated estradiol reduces miR-148a to promote HLA-G expression in breast cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014, 451, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quero, L.; Tiaden, A.N.; Hanser, E.; Roux, J.; Laski, A.; Hall, J.; Kyburz, D. miR-221-3p Drives the Shift of M2-Macrophages to a Pro-Inflammatory Function by Suppressing JAK3/STAT3 Activation. Front Immunol. 2020, 10, 3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaytán-Pacheco, N.; Ibáñez-Salazar, A.; Herrera-Van Oostdam, A.S.; Oropeza-Valdez, J.J.; Magaña-Aquino, M.; Adrián López, J.; Monárrez-Espino, J.; López-Hernández, Y. miR-146a, miR-221, and miR-155 are Involved in Inflammatory Immune Response in Severe COVID-19 Patients. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022, 13, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hu, J.; Huang, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, S.; Hu, X. miR-155: An Important Role in Inflammation Response. J Immunol Res. 2022, 2022, 7437281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study population | Males | Females | |

| n = 128 | 47 (36.7 %) | 81 (63.3 %) | |

| Age (years), median (IQR); (range) |

45 (36–54); (23–72) |

42 (36–51); (26–72) |

47 (35.5–54.5); (23–64) |

| age groups | |||

| 23–45 years (n) | 67 (52.3 %) | 29 (43.3 %) | 38 (56.7 %) |

| 46–72 years (n) | 61 (47.7 %) | 18 (29.5 %) | 43 (70.5 %) |

| Interval (days) median (IQR); (range) |

71 (70-79); (55-100) |

71 (70-81); (55-100) |

71 (69-78); (56-100) |

|

Anti-S/RBD titer (AU/L) GMT (95% CI) |

p-value | |

| All subjects | 921.5 | |

| (790.7-1074) | ||

| F | 1069 (925.8-1234) |

0.0123 |

| M | 713,9 | |

| (509.1-1001) | ||

| Age | ||

| ≤ 45 years | 1031 | 0.42 |

| (925.8-1234) | ||

| > 45 years | 713.9 | |

| (509.1-1001) | ||

| Sex and age | ||

| F≤ 45 years | 1031 | 0.37 |

| 870.7-1220 | ||

| F> 45 years | 978.9 | |

| 830.9-1153 | ||

| M≤ 45 years | 862.7 | 0.48 |

| (696.5-1068) | ||

| M> 45 years | 526.2 | |

| (225.6-1227) | ||

| Description | KEGG ID | p-value | FDR * | Genes |

| Epstein-Barr virus infection | hsa05169 | 8,74364E-08 | 2,49E-06 | HLA-G/BCL2/CDKN1B/RUNX3/ BCL2L11/PDIA3/STAT3/IKBKB/BAX |

| FoxO signaling pathway | hsa04068 | 8,86186E-07 | 1,37E-05 | IRS1/CDKN1B/BCL2L11/S1PR1/STAT3/ TGFB2/IKBKB |

| Human T-cell leukemia virus 1 infection | hsa05166 | 2,79378E-05 | 0,000259 | HLA-G/MMP7/SMAD2/TGFB2/IKBKB/ BAX/NRP1 |

| Human papillomavirus infection | hsa05165 | 4,59073E-05 | 0,000387 | HLA-G/WNT10B/CDKN1B/ITGB8/ITGA5/ WNT1/IKBKB/BAX |

| TGF-beta signaling pathway | hsa04350 | 7,06962E-05 | 0,000504 | TGIF2/ACVR1/ROCK1/SMAD2/TGFB2 |

| PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | hsa04151 | 8,29241E-05 | 0,000517 | IRS1/BCL2/CDKN1B/ITGB8/ITGA5/MET/ BCL2L11/IKBKB |

| Herpes simplex virus 1 infection | hsa05168 | 8,36848E-05 | 0,000517 | HLA-G/BCL2/ITGA5/PDIA3/IKBKB/BAX |

| MAPK signaling pathway | hsa04010 | 0,000177249 | 0,000912 | RPS6KA5/CDC25B/MAP3K4/MET/MAP3K9/ TGFB2/IKBKB |

| Measles | hsa05162 | 0,000232811 | 0,001135 | BCL2/CDKN1B/STAT3/IKBKB/BAX |

| Human cytomegalovirus infection | hsa05163 | 0,000274049 | 0,001156 | HLA-G/ROCK1/PDIA3/STAT3/IKBKB/BAX |

| Apoptosis - multiple species | hsa04215 | 0,000288247 | 0,001161 | BCL2/BCL2L11/BAX |

| Hepatitis B | hsa05161 | 0,000486342 | 0,001733 | BCL2/STAT3/TGFB2/IKBKB/BAX |

| Apoptosis | hsa04210 | 0,00219604 | 0,005812 | BCL2/BCL2L11/IKBKB/BAX |

| Adipocytokine signaling pathway | hsa04920 | 0,002859899 | 0,006971 | IRS1/STAT3/IKBKB |

| p53 signaling pathway | hsa04115 | 0,003478888 | 0,007952 | BCL2/SERPINE1/BAX |

| Cellular senescence | hsa04218 | 0,003692136 | 0,007952 | HLA-G/SERPINE1/SMAD2/TGFB2 |

| Cell cycle | hsa04110 | 0,003777087 | 0,007952 | CDC25B/CDKN1B/SMAD2/TGFB2 |

| mTOR signaling pathway | hsa04150 | 0,003777087 | 0,007952 | IRS1/WNT10B/WNT1/IKBKB |

| Chemokine signaling pathway | hsa04062 | 0,00765295 | 0,014769 | VAV2/ROCK1/STAT3/IKBKB |

| Th17 cell differentiation | hsa04659 | 0,009837214 | 0,017193 | SMAD2/STAT3/IKBKB |

| Hormone signaling | hsa04081 | 0,011813777 | 0,020265 | CCKBR/IRS1/ACVR1/STAT3 |

| Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | hsa04810 | 0,014353241 | 0,024174 | ITGB8/VAV2/ITGA5/ROCK1 |

| Antigen processing and presentation | hsa04612 | 0,043197093 | 0,053352 | HLA-G/PDIA3 |

| Description | KEGG ID | p-value | FDR* | Genes | |||

| FoxO signaling pathway | hsa04068 | 1,02E-07 | 4,28E-06 | CDKN1B/BCL2L11/FOXO3/TNFSF10/BNIP3/ PTEN/SIRT1/MDM2/PIK3R1 |

|||

| Cellular senescence | hsa04218 | 4,82E-06 | 4,84E-05 | FOXO3/PTEN/TP53/ETS1/RB1/SIRT1/MDM2/PIK3R1 | |||

| Apoptosis | hsa04210 | 1,87E-05 | 0,000141 | BCL2L11/BBC3/TNFSF10/FOS/TP53/APAF1/PIK3R1 | |||

| Mitophagy - animal | hsa04137 | 4,31E-05 | 0,000217 | FOXO3/BNIP3L/TBK1/BNIP3/TP53/BECN1 | |||

| Autophagy - animal | hsa04140 | 7,54E-05 | 0,000325 | DDIT4/TBK1/BNIP3/PTEN/RAB1A/PIK3R1/BECN1 | |||

| p53 signaling pathway | hsa04115 | 9,46E-05 | 0,000329 | BBC3/PTEN/TP53/APAF1/MDM2 | |||

| PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | hsa04151 | 0,00034 | 0,000906 | CDKN1B/BCL2L11/FOXO3/KIT/DDIT4/PTEN/ TP53/MDM2/PIK3R1 |

|||

| Cell cycle | hsa04110 | 0,000409 | 0,00103 | CDKN1B/CDKN1C/TP53/WEE1/RB1/MDM2 | |||

| TNF signaling pathway | hsa04668 | 0,000815 | 0,001891 | ICAM1/FOS/SELE/PIK3R1/SOCS3 | |||

| mTOR signaling pathway | hsa04150 | 0,002861 | 0,004887 | DDIT4/PTEN/DVL2/PIK3R1/GRB10 | |||

| Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | hsa04620 | 0,004558 | 0,007239 | TBK1/FOS/TICAM1/PIK3R1 | |||

| Leukocyte transendothelial migration | hsa04670 | 0,005682 | 0,008869 | ICAM1/PIK3R1/MMP2/CXCL12 | |||

| Thyroid hormone signaling pathway | hsa04919 | 0,006783 | 0,010066 | ESR1/TP53/MDM2/PIK3R1 | |||

| Estrogen signaling pathway | hsa04915 | 0,010646 | 0,014602 | FOS/ESR1/PIK3R1/MMP2 | |||

| JAK-STAT signaling pathway | hsa04630 | 0,020074 | 0,025239 | PIK3R1/STAT5A/SOCS3/SOCS1 | |||

| NF-kappa B signaling pathway | hsa04064 | 0,027183 | 0,031548 | ICAM1/TICAM1/CXCL12 | |||

| Th17 cell differentiation | hsa04659 | 0,029922 | 0,033859 | FOS/RUNX1/STAT5A | |||

| Chemokine signaling pathway | hsa04062 | 0,031384 | 0,034647 | FOXO3/PAK1/PIK3R1/CXCL12 | |||

|

MAPK signaling pathway |

hsa04010 | 0,037664 | 0,040358 | KIT/FOS/TP53/PAK1/STMN1 | |||

|

AMPK signaling pathway |

hsa04152 | 0,039796 | 0,040938 | FOXO3/SIRT1/PIK3R1 | |||

| T cell receptor signaling pathway | hsa04660 | 0,039796 | 0,040938 | FOS/PAK1/PIK3R1 | |||

| Description | KEGG ID | p-value | FDR * | Genes |

| Hepatitis B | hsa05161 | 6,35E-13 | 2,25E-11 | TAB2/IKBKE/KRAS/JUN/FADD/MYD88/YWHAZ/ SMAD4/APAF1/SMAD3/CXCL8/NFKB1/E2F2/PIK3R1/FOS/MAPK14/MYC/MAPK13/STAT1/ CASP3 |

| Epstein-Barr virus infection | hsa05169 | 4,26E-11 | 1,13E-09 | TAB2/IKBKE/ICAM1/JUN/FADD/MYD88/RAC1/ SAP30L/MAP3K14/APAF1/CCND1/NFKB1/E2F2/PIK3R1/MAPK14/MYC/MAPK13/STAT1/ CCND2/CASP3 |

| Cellular senescence | hsa04218 | 2,48E-09 | 2,93E-08 | RHEB/FOXO3/KRAS/ETS1/SMAD2/SMAD3/CCND1/CXCL8/NFKB1/E2F2/PIK3R1/MAPK14/MYC/MAPK13/CCND2/PTEN |

| TNF signaling pathway | hsa04668 | 4,03E-09 | 3,89E-08 | TAB2/CEBPB/EDN1/ICAM1/SELE/JUN/FADD/MAP3K14/ NFKB1/PIK3R1/FOS/MAPK14/MAPK13/CASP3 |

| Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | hsa04620 | 1,26E-08 | 9,28E-08 | TAB2/IKBKE/JUN/FADD/MYD88/RAC1/CXCL8/NFKB1/PIK3R1/FOS/MAPK14/MAPK13/STAT1 |

|

IL-17 signaling pathway |

hsa04657 | 2,44E-08 | 1,62E-07 | TAB2/CEBPB/IKBKE/JUN/FADD/IL17RB/CXCL8/NFKB1/ FOS/MAPK14/MAPK13/CASP3 |

| Hepatitis C | hsa05160 | 1,68E-07 | 9,4E-07 | CLDN1/IKBKE/KRAS/FADD/YWHAZ/APAF1/CCND1/ NFKB1/E2F2/PIK3R1/MYC/STAT1/CASP3/ NR1H3 |

| Measles | hsa05162 | 2,35E-07 | 1,25E-06 | TAB2/IKBKE/JUN/FADD/MYD88/APAF1/CCND1/NFKB1/PIK3R1/FOS/STAT1/CCND2/CASP3 |

|

Th17 cell differentiation |

hsa04659 | 9,74E-07 | 4,14E-06 | IFNGR1/SMAD2/JUN/SMAD4/SMAD3/NFKB1/ FOS/MAPK14/HIF1A/MAPK13/STAT1 |

|

FoxO signaling pathway |

hsa04068 | 1,03E-06 | 4,23E-06 | FOXO3/KRAS/BCL6/SMAD4/GABARAPL1/SMAD3/ CCND1/PIK3R1/MAPK14/MAPK13/CCND2/ PTEN |

|

T cell receptor signaling pathway |

hsa04660 | 3E-06 | 1,1E-05 | RHOA/KRAS/JUN/CARD11/MAP3K14/PAK2/NFKB1/PIK3R1/FOS/MAPK14/MAPK13 |

|

MAPK signaling pathway |

hsa04010 | 4,1E-06 | 1,28E-05 | TAB2/FGF7/KRAS/CSF1R/JUN/MAP3K10/MYD88/RAC1/RAPGEF2/MAP3K14/PAK2/NFKB1/FOS/MAPK14/MYC/MAPK13/CASP3 |

| NOD-like receptor signaling pathway | hsa04621 | 7,68E-06 | 2,27E-05 | TAB2/PKN2/RHOA/IKBKE/JUN/FADD/MYD88/GABARAPL1/CXCL8/NFKB1/MAPK14/MAPK13/STAT1 |

| Cell cycle | hsa04110 | 3,56E-05 | 8,22E-05 | TRIP13/SMAD2/ANAPC16/YWHAZ/SMAD4/ SMAD3/WEE1/CCND1/E2F2/MYC/CCND2 |

| PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | hsa04151 | 4,75E-05 | 0,000108 | RHEB/PKN2/FGF7/FOXO3/KRAS/MYB/CSF1R/ NOS3/YWHAZ/RAC1/CCND1/NFKB1/PIK3R1/ MYC/RPTOR/CCND2/PTEN |

| Influenza A | hsa05164 | 8,15E-05 | 0,00017 | IKBKE/IFNGR1/ICAM1/FADD/MYD88/APAF1/ CXCL8/NFKB1/PIK3R1/STAT1/CASP3 |

|

B cell receptor signaling pathway |

hsa04662 | 8,48E-05 | 0,000172 | INPP5D/KRAS/JUN/CARD11/RAC1/NFKB1/ PIK3R1/FOS |

| Apoptosis | hsa04210 | 0,000274 | 0,000448 | KRAS/JUN/FADD/MAP3K14/APAF1/NFKB1/ PIK3R1/FOS/CASP3 |

| TGF-beta signaling pathway | hsa04350 | 0,000281 | 0,000453 | SMAD5/SMAD1/RHOA/SMAD2/SKI/SMAD4/ SMAD3/MYC |

| Coronavirus disease - COVID-19 | hsa05171 | 0,000346 | 0,000536 | TAB2/AGTR1/IKBKE/JUN/MYD88/CXCL8/NFKB1/ PIK3R1/FOS/MAPK14/MAPK13/STAT1 |

| Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation | hsa04658 | 0,000617 | 0,000887 | IFNGR1/JUN/NFKB1/FOS/MAPK14/MAPK13/ STAT1 |

| RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway | hsa04622 | 0,000892 | 0,001193 | IKBKE/FADD/CXCL8/NFKB1/MAPK14/MAPK13 |

|

JAK-STAT signaling pathway |

hsa04630 | 0,001268 | 0,001607 | SOCS1/IFNGR1/IL13RA1/CCND1/PIK3R1/MYC/ SOCS6/STAT1/CCND2 |

|

NF-kappa B signaling pathway |

hsa04064 | 0,00127 | 0,001607 | TAB2/ICAM1/MYD88/CARD11/MAP3K14/ CXCL8/NFKB1 |

| Mitophagy - animal | hsa04137 | 0,00127 | 0,001607 | FOXO3/KRAS/JUN/MITF/GABARAPL1/TOMM20/HIF1A |

| Human papillomavirus infection | hsa05165 | 0,002137 | 0,002497 | APC/RHEB/IKBKE/KRAS/CSNK1A1/FADD/ CCND1/NFKB1/PIK3R1/STAT1/CCND2/CASP3/PTEN |

|

Leukocyte transendothelial migration |

hsa04670 | 0,002257 | 0,002608 | CLDN1/RHOA/ICAM1/RAC1/PIK3R1/MAPK14/MAPK13 |

| Autophagy - animal | hsa04140 | 0,005021 | 0,005561 | RHEB/KRAS/GABARAPL1/VPS18/PIK3R1/HIF1A/RPTOR/PTEN |

|

p53 signaling pathway |

hsa04115 | 0,006329 | 0,006662 | APAF1/CCND1/CCND2/CASP3/PTEN |

|

Chemokine signaling pathway |

hsa04062 | 0,010868 | 0,010727 | RHOA/FOXO3/KRAS/RAC1/CXCL8/NFKB1/PIK3R1 /STAT1 |

|

Apoptosis – multiple species |

hsa04215 | 0,013437 | 0,012642 | FADD/APAF1/CASP3 |

|

Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity |

hsa04650 | 0,018674 | 0,016969 | IFNGR1/KRAS/ICAM1/RAC1/PIK3R1/CASP3 |

| Hormone signaling | hsa04081 | 0,056541 | 0,047333 | SMAD5/SMAD1/RHOA/AGTR1/SMAD4/PIK3R1/THRB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).