Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

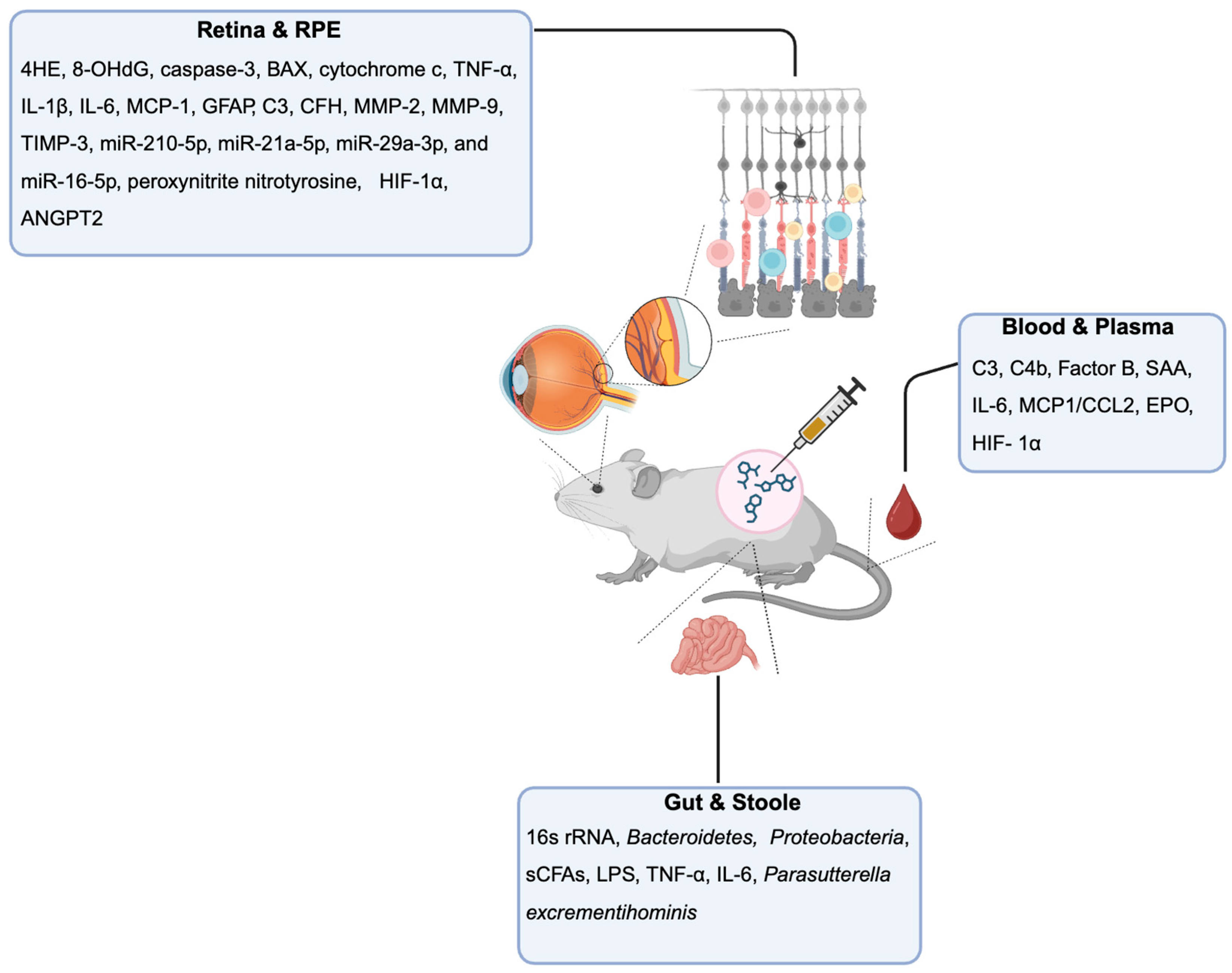

Chemical AMD Models for Biomarker Discovery

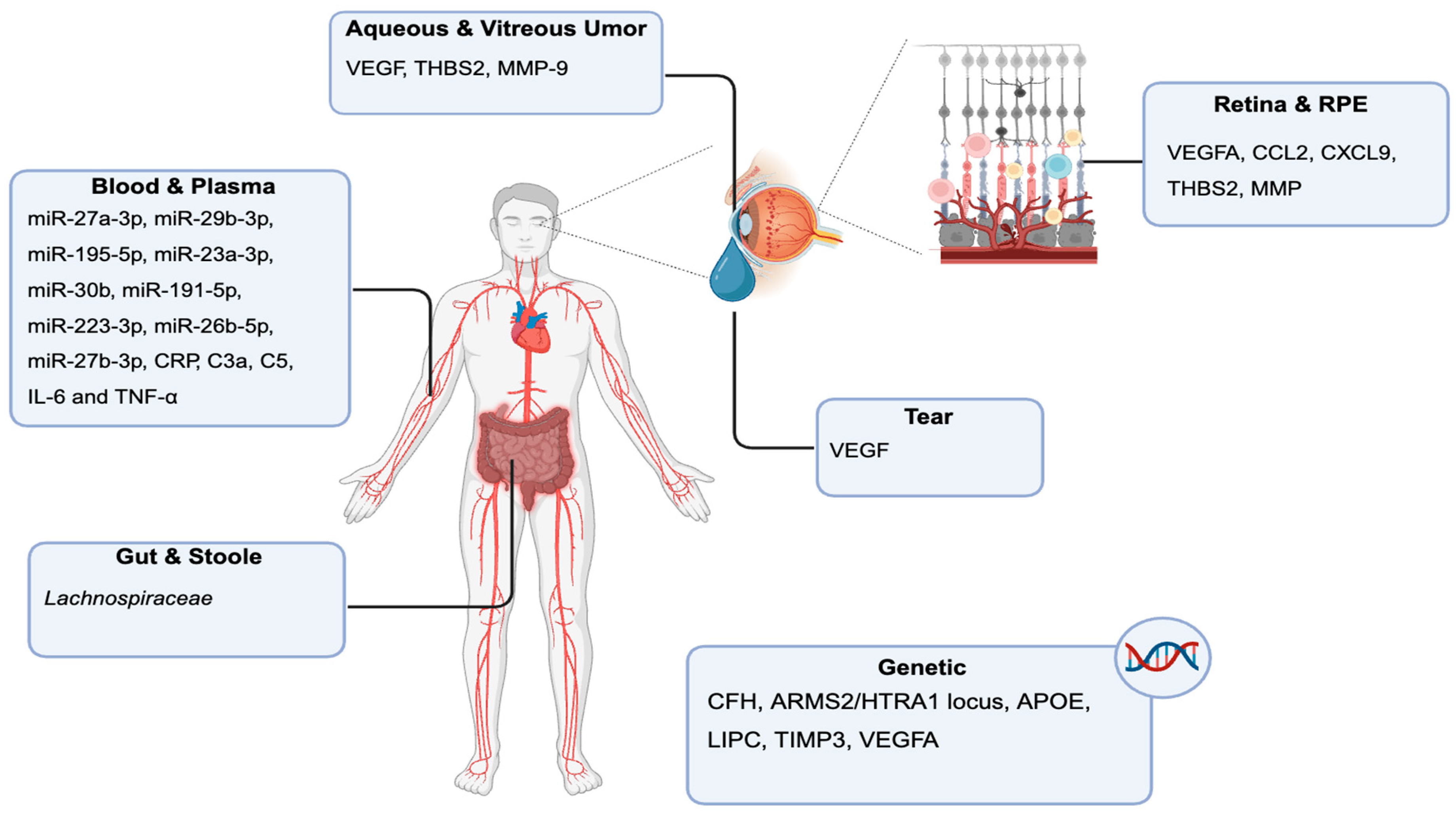

Retina and RPE-Choroid Tissue Biomarkers

Blood and Plasma Biomarkers

Stool and Gut Microbiome Biomarkers

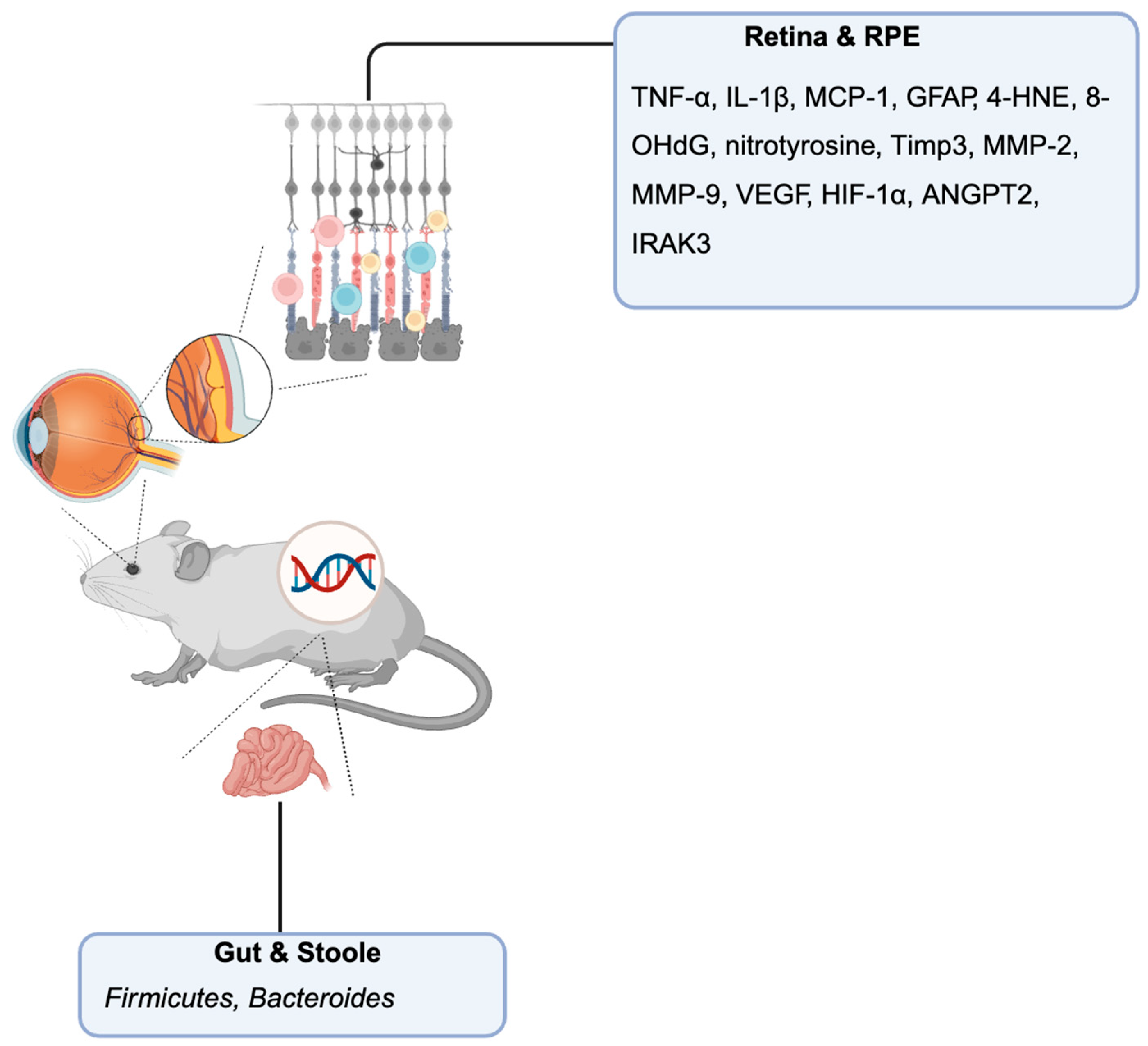

Genetic Mouse Models for AMD

Retina and RPE-Choroid Tissue Biomarkers

Stool and Gut Microbiome Biomarkers

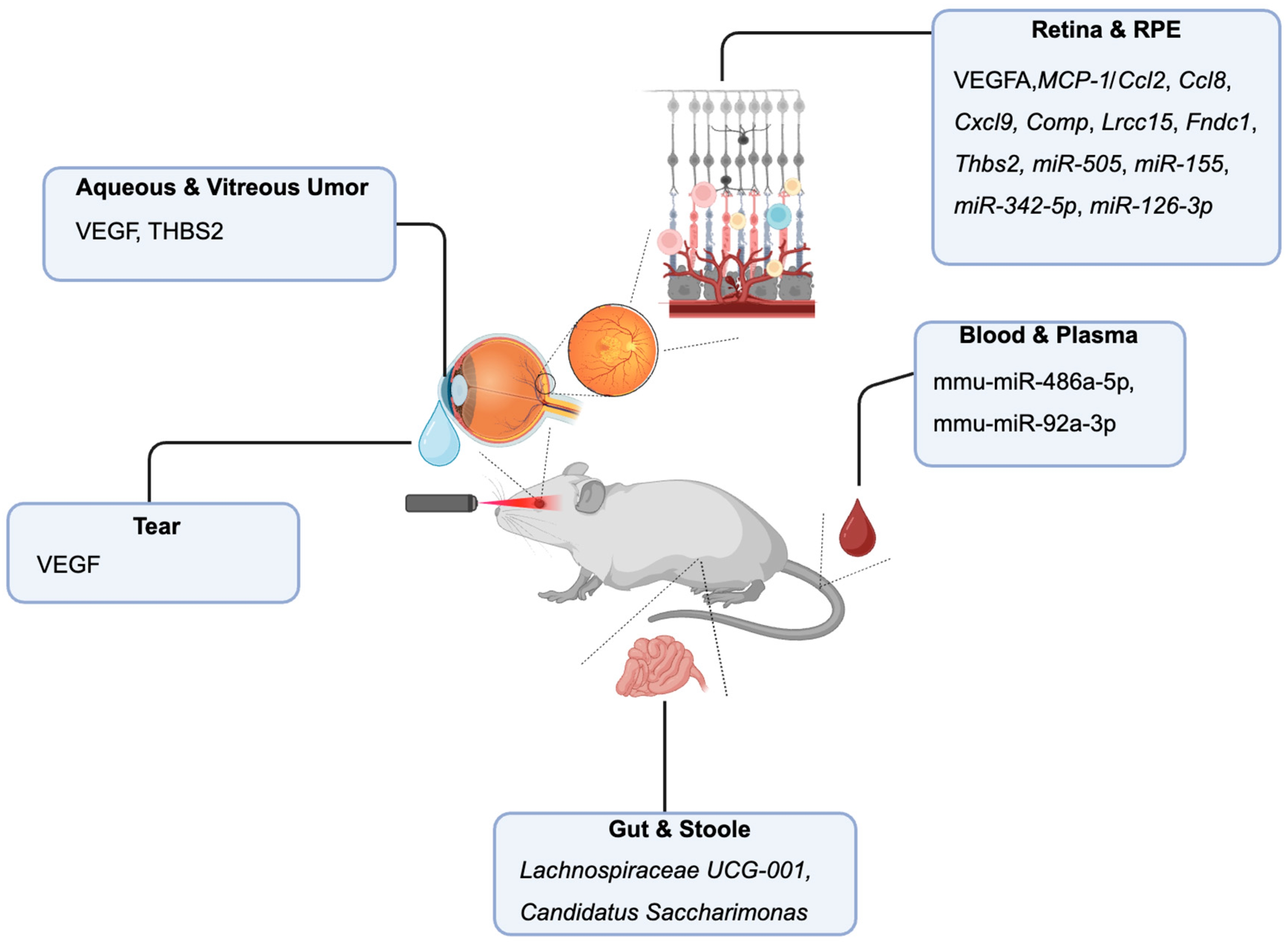

Laser-Induced Neovascularization Model

Retina and RPE-Choroid Tissue Biomarkers

Blood and Plasma Biomarkers

Tear Fluid Biomarkers

Aqueous and Vitreous Humor Biomarkers

Stool and Gut Microbiome Biomarkers

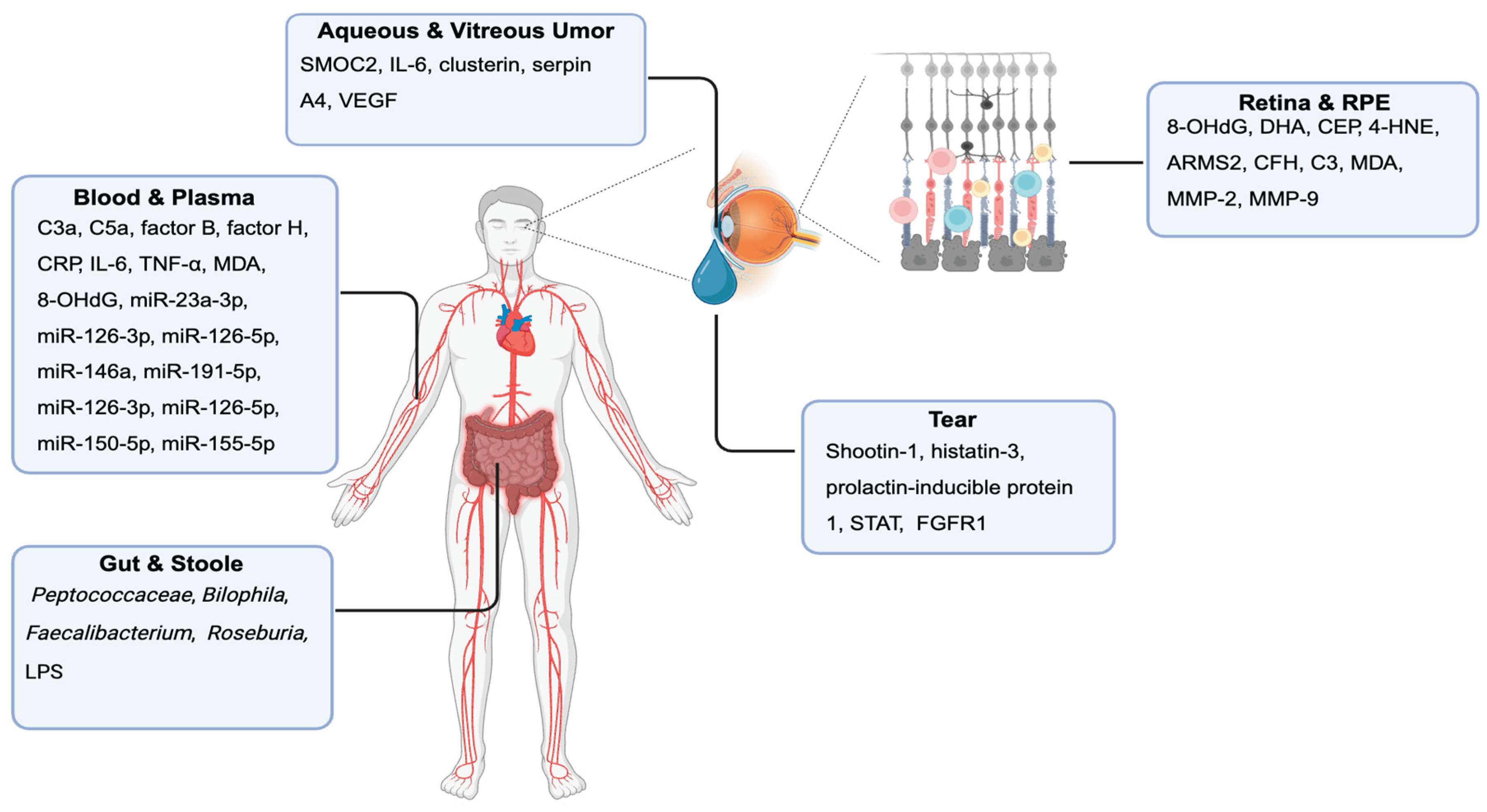

Biomarkers in “Dry” AMD in Humans

Retina and RPE-Choroid Tissue Biomarkers

Blood and Plasma Biomarkers

Tear Fluid Biomarkers

Aqueous and Vitreous Humor Biomarkers

Stool and Gut Microbiome Biomarkers

Biomarkers in “Wet” AMD in Humans

Retinal and RPE-Choroid Tissue Biomarkers

Blood, Plasma, and Serum Biomarkers

Tear Fluid Biomarkers

Aqueous and Vitreous Humor Biomarkers

Genetic Biomarkers

Gut Microbiome Biomarkers

Comparative Analysis of Biomarker Profiles in Chemically Induced Models and Human Dry AMD

Comparison of Biomarker Findings in the Genetic Mouse Model and Human Dry AMD

Comparison of Biomarker Findings in the Mouse Model and Human Wet AMD

Conclusions

References

- Wong, W. L. et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health 2, e106–e116 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Curcio, C. A., Kar, D., Owsley, C., Sloan, K. R. & Ach, T. Age-Related Macular Degeneration, a Mathematically Tractable Disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 65, 4 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, M. & Malek, G. A Review of Pathogenic Drivers of Age-Related Macular Degeneration, Beyond Complement, and Potential Endpoints to Test Therapeutic Interventions in Preclinical Studies. Adv Exp Med Biol 1185, 9–13 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Wong, J. H. C. et al. Exploring the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration: A review of the interplay between retinal pigment epithelium dysfunction and the innate immune system. Front Neurosci 16, 1009599 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Bowes Rickman, C., Farsiu, S., Toth, C. A. & Klingeborn, M. Dry Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targets, and Imaging. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54, ORSF68–ORSF80 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, L. G. et al. A large genome-wide association study of age-related macular degeneration highlights contributions of rare and common variants. Nat Genet 48, 134–143 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Hageman, G. S. et al. Clinical validation of a genetic model to estimate the risk of developing choroidal neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Hum Genomics 5, 420–440 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Lad, E. M., Finger, R. P. & Guymer, R. Biomarkers for the Progression of Intermediate Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmol Ther 12, 2917–2941 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Li, S. et al. Serum metabolite biomarkers for the early diagnosis and monitoring of age-related macular degeneration. Journal of Advanced Research (2024). [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, E. et al. Deep Learning in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Medicina (Kaunas) 60, 990 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B. D., Lee, T. T., Bell, B. A., Wang, T. & Dunaief, J. L. Optimizing the sodium iodate model: effects of dose, gender, and age. Exp Eye Res 239, 109772 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Exploring the Role of Exosomal miRNA-146a-5p in Sodium Iodate-Induced Retinal Pigment Epithelial Dysfunction | IOVS | ARVO Journals (2024).

- Upadhyay, M. & Bonilha, V. L. Regulated cell death pathways in the sodium iodate model: Insights and implications for AMD. Experimental Eye Research 238, 109728 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Liu, S., Hu, D., Xing, Y. & Shen, Y. N -methyl- N -nitrosourea-induced retinal degeneration in mice. Experimental Eye Research 121, 102–113 (2014).

- Zhao, J. et al. Aberrant Buildup of All-Trans-Retinal Dimer, a Nonpyridinium Bisretinoid Lipofuscin Fluorophore, Contributes to the Degeneration of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 58, 1063–1075 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. et al. Protective effect of autophagy on human retinal pigment epithelial cells against lipofuscin fluorophore A2E: implications for age-related macular degeneration. Cell Death Dis 6, e1972–e1972 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. et al. Hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage and protective role of peroxiredoxin 6 protein via EGFR/ERK signaling pathway in RPE cells. Front Aging Neurosci 15, 1169211 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kaczara, P., Sarna, T. & Burke, J. M. Dynamics of H2O2 Availability to ARPE-19 Cultures in Models of Oxidative Stress. Free Radic Biol Med 48, 1064–1070 (2010). [CrossRef]

- You, L., Zhao, W., Li, X., Yang, C. & Guo, P. Tyrosol protects RPE cells from H2O2-induced oxidative damage in vitro and in vivo through activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. European Journal of Pharmacology 991, 177316 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Hara, A. et al. A new model of retinal photoreceptor cell degeneration induced by a chemical hypoxia-mimicking agent, cobalt chloride. Brain Research 1109, 192–200 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sánchez, J. & Chánez-Cárdenas, M. E. The use of cobalt chloride as a chemical hypoxia model. Journal of Applied Toxicology 39, 556–570 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Montezuma, S. R., Sobrin, L. & Seddon, J. M. Review of Genetics in Age Related Macular Degeneration. Seminars in Ophthalmology 22, 229–240 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Hanus, J., Anderson, C. & Wang, S. RPE Necroptosis in Response to Oxidative Stress and in AMD. Ageing Res Rev 24, 286–298 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Enzbrenner, A. et al. Sodium Iodate-Induced Degeneration Results in Local Complement Changes and Inflammatory Processes in Murine Retina. Int J Mol Sci 22, 9218 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. T. et al. Inflammatory Mediators Induced by Amyloid-Beta in the Retina and RPE In Vivo: Implications for Inflammasome Activation in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54, 2225–2237 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Cervellati, F. et al. Hypoxia induces cell damage via oxidative stress in retinal epithelial cells. Free Radic Res 48, 303–312 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Lazzara, F. et al. Stabilization of HIF-1α in Human Retinal Endothelial Cells Modulates Expression of miRNAs and Proangiogenic Growth Factors. Front Pharmacol 11, 1063 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y. et al. Comparative mechanistic study of RPE cell death induced by different oxidative stresses. Redox Biol 65, 102840 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-J. et al. 4-HNE induces proinflammatory cytokines of human retinal pigment epithelial cells by promoting extracellular efflux of HSP70. Exp Eye Res 188, 107792 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Penn, J. S. et al. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Eye Disease. Prog Retin Eye Res 27, 331–371 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Spilsbury, K., Garrett, K. L., Shen, W. Y., Constable, I. J. & Rakoczy, P. E. Overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the retinal pigment epithelium leads to the development of choroidal neovascularization. Am J Pathol 157, 135–144 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Luo, L. et al. Photoreceptor avascular privilege is shielded by soluble VEGF receptor-1. eLife 2, e00324 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Hanus, J., Anderson, C., Sarraf, D., Ma, J. & Wang, S. Retinal pigment epithelial cell necroptosis in response to sodium iodate. Cell Death Discov 2, 16054 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y., Liu, W., Liu, G., Li, X. & Lu, P. Assessing the protective effects of cryptotanshinone on CoCl2-induced hypoxia in RPE cells. Mol Med Rep 24, 739 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y. et al. Combination of Lactobacillus fermentum NS9 and aronia anthocyanidin extract alleviates sodium iodate-induced retina degeneration. Sci Rep 13, 8380 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Y. et al. Unveiling the gut-eye axis: how microbial metabolites influence ocular health and disease. Front Med (Lausanne) 11, 1377186 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Raoul, W. et al. CCL2/CCR2 and CX3CL1/CX3CR1 chemokine axes and their possible involvement in age-related macular degeneration. J Neuroinflammation 7, 87 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Vessey, K. A. et al. Ccl2/Cx3cr1 knockout mice have inner retinal dysfunction but are not an accelerated model of AMD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53, 7833–7846 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Ross, R. J. et al. Immunological protein expression profile in Ccl2/Cx3cr1 deficient mice with lesions similar to age-related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res 86, 675–683 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Imamura, Y. et al. Drusen, choroidal neovascularization, and retinal pigment epithelium dysfunction in SOD1-deficient mice: a model of age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 11282–11287 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Hashizume, K. et al. Retinal Dysfunction and Progressive Retinal Cell Death in SOD1-Deficient Mice. Am J Pathol 172, 1325–1331 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. et al. Mice With a Combined Deficiency of Superoxide Dismutase 1 (Sod1), DJ-1 (Park7), and Parkin (Prkn) Develop Spontaneous Retinal Degeneration With Aging. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 60, 3740–3751 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Lin, M. K. et al. HTRA1, an age-related macular degeneration protease, processes extracellular matrix proteins EFEMP1 and TSP1. Aging Cell 17, e12710 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Vierkotten, S., Muether, P. S. & Fauser, S. Overexpression of HTRA1 leads to ultrastructural changes in the elastic layer of Bruch’s membrane via cleavage of extracellular matrix components. PLoS One 6, e22959 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y. et al. N-Terminomics identifies HtrA1 cleavage of thrombospondin-1 with generation of a proangiogenic fragment in the polarized retinal pigment epithelial cell model of age-related macular degeneration. Matrix Biol 70, 84–101 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Hu, W. et al. Expression of VLDLR in the retina and evolution of subretinal neovascularization in the knockout mouse model’s retinal angiomatous proliferation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49, 407–415 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Zinkernagel, M. S. et al. Association of the Intestinal Microbiome with the Development of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Sci Rep 7, 40826 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Bringer, M.-A., Gabrielle, P.-H., Bron, A. M., Creuzot-Garcher, C. & Acar, N. The gut microbiota in retinal diseases. Exp Eye Res 214, 108867 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Badia, A. et al. Transcriptomics analysis of Ccl2/Cx3cr1/Crb1rd8 deficient mice provides new insights into the pathophysiology of progressive retinal degeneration. Exp Eye Res 203, 108424 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. et al. Replenishing IRAK-M expression in retinal pigment epithelium attenuates outer retinal degeneration. Sci Transl Med 16, eadi4125 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. et al. Increased expression of multifunctional serine protease, HTRA1, in retinal pigment epithelium induces polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 14578–14583 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Cai, X., Seal, S. & McGinnis, J. F. Sustained inhibition of neovascularization in vldlr-/- mice following intravitreal injection of cerium oxide nanoparticles and the role of the ASK1-P38/JNK-NF-κB pathway. Biomaterials 35, 249–258 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Zysset-Burri, D. C. et al. Associations of the intestinal microbiome with the complement system in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. NPJ Genom Med 5, 34 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Rowan, S. & Taylor, A. Gut microbiota modify risk for dietary glycemia-induced age-related macular degeneration. Gut Microbes 9, 452–457 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Shah, R. S., Soetikno, B. T., Lajko, M. & Fawzi, A. A. A Mouse Model for Laser-induced Choroidal Neovascularization. J Vis Exp 53502 (2015) doi:10.3791/53502. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, A. I. et al. Optimization and characterization of an improved laser-induced choroidal neovascularization animal model for the study of retinal diseases. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 64, 2112 (2023).

- Gong, Y. et al. Optimization of an Image-Guided Laser-Induced Choroidal Neovascularization Model in Mice. PLOS ONE 10, e0132643 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Salas, A. et al. Neovascular Progression and Retinal Dysfunction in the Laser-Induced Choroidal Neovascularization Mouse Model. Biomedicines 11, 2445 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-S. et al. Comparative Analysis of Molecular Landscape in Mouse Models and Patients Reveals Conserved Inflammation Pathways in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 65, 13 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis of human and murine choroidal neovascularization identifies fibroblast growth factor inducible-14 as phylogenetically conserved mediator of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1868, 166340 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Toma, H. S., Barnett, J. M., Penn, J. S. & Kim, S. J. Improved assessment of laser-induced choroidal neovascularization. Microvasc Res 80, 295–302 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Iwanishi, H. et al. Delayed regression of laser-induced choroidal neovascularization in TNFα-null mice. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 26, 5315–5325 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Lambert, V. et al. Laser-induced choroidal neovascularization model to study age-related macular degeneration in mice. Nat Protoc 8, 2197–2211 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. et al. Proteotranscriptomic analyses reveal distinct interferon-beta signaling pathways and therapeutic targets in choroidal neovascularization. Front. Immunol. 14, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Apte, R. S., Richter, J., Herndon, J. & Ferguson, T. A. Macrophages Inhibit Neovascularization in a Murine Model of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. PLoS Med 3, e310 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Brandli, A., Khong, F. L., Kong, R. C. K., Kelly, D. J. & Fletcher, E. L. Transcriptomic analysis of choroidal neovascularization reveals dysregulation of immune and fibrosis pathways that are attenuated by a novel anti-fibrotic treatment. Sci Rep 12, 859 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Kiel, C. et al. A Circulating MicroRNA Profile in a Laser-Induced Mouse Model of Choroidal Neovascularization. Int J Mol Sci 21, 2689 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Moshtaghion, S. M. M. et al. VEGF in Tears as a Biomarker for Exudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Molecular Dynamics in a Mouse Model and Human Samples. Int J Mol Sci 26, 3855 (2025). [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, F. M. et al. Vitreous humor proteome: unraveling the molecular mechanisms underlying proliferative and neovascular vitreoretinal diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci 80, 22 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Oca, A. I. et al. Predictive Biomarkers of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Response to Anti-VEGF Treatment. Journal of Personalized Medicine 11, 1329 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ratnapriya, R. & Chew, E. Y. Age-related macular degeneration-clinical review and genetics update. Clin Genet 84, 160–166 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Andriessen, E. M. et al. Gut microbiota influences pathological angiogenesis in obesity-driven choroidal neovascularization. EMBO Mol Med 8, 1366–1379 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. & Mo, Y. The gut-retina axis: a new perspective in the prevention and treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Front. Endocrinol. 14, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Bakri, S. J. et al. Geographic atrophy: Mechanism of disease, pathophysiology, and role of the complement system. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 29, S2–S11 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Lau, L.-I., Liu, C. J. & Wei, Y.-H. Increase of 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine in aqueous humor of patients with exudative age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 51, 5486–5490 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Shen, J. K. et al. Oxidative damage in age-related macular degeneration. Histol Histopathol 22, 1301–1308 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Crabb, J. W. et al. Drusen proteome analysis: an approach to the etiology of age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 14682–14687 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Lu, L. et al. Synthesis and structural characterization of carboxyethylpyrrole-modified proteins: mediators of age-related macular degeneration. Bioorg Med Chem 17, 7548–7561 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Gu, X. et al. Carboxyethylpyrrole protein adducts and autoantibodies, biomarkers for age-related macular degeneration. J Biol Chem 278, 42027–42035 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Renganathan, K. et al. CEP Biomarkers as Potential Tools for Monitoring Therapeutics. PLoS One 8, e76325 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Ethen, C. M., Reilly, C., Feng, X., Olsen, T. W. & Ferrington, D. A. Age-related macular degeneration and retinal protein modification by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 48, 3469–3479 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Gu, J. et al. Proteomic and genomic biomarkers for age-related macular degeneration. Adv Exp Med Biol 664, 411–417 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Totan, Y. et al. Oxidative macromolecular damage in age-related macular degeneration. Curr Eye Res 34, 1089–1093 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Nita, M., Strzałka-Mrozik, B., Grzybowski, A., Mazurek, U. & Romaniuk, W. Age-related macular degeneration and changes in the extracellular matrix. Med Sci Monit 20, 1003–1016 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A. A., Lee, Y., Zhang, J.-J. & Marshall, J. Disturbed Matrix Metalloproteinase Activity of Bruch’s Membrane in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 52, 4459- (2011). [CrossRef]

- Hageman, G. S. et al. A common haplotype in the complement regulatory gene factor H (HF1/CFH) predisposes individuals to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 7227–7232 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, R. et al. Plasma complement components and activation fragments: associations with age-related macular degeneration genotypes and phenotypes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50, 5818–5827 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Ildefonso, C. J., Biswal, M. R., Ahmed, C. M. & Lewin, A. S. The NLRP3 Inflammasome and its Role in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Adv Exp Med Biol 854, 59–65 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Szaflik, J. P. et al. DNA damage and repair in age-related macular degeneration. Mutat Res 669, 169–176 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Martinez, B. & Peplow, P. V. MicroRNAs as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of age-related macular degeneration: advances and limitations. Neural Regen Res 16, 440–447 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Berber, P., Grassmann, F., Kiel, C. & Weber, B. H. F. An Eye on Age-Related Macular Degeneration: The Role of MicroRNAs in Disease Pathology. Mol Diagn Ther 21, 31–43 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Aguilar, M., Groman-Lupa, S. & Jiménez-Martínez, M. C. MicroRNAs as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets in age-related macular degeneration. Front Ophthalmol (Lausanne) 3, 1023782 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Winiarczyk, M. et al. Tear film proteome in age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 256, 1127–1139 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Kaarniranta, K., Tokarz, P., Koskela, A., Paterno, J. & Blasiak, J. Autophagy regulates death of retinal pigment epithelium cells in age-related macular degeneration. Cell Biol Toxicol 33, 113–128 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L. & Beuerman, R. W. The power of tears: how tear proteomics research could revolutionize the clinic. Expert Rev Proteomics 14, 189–191 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L. et al. Identification of tear fluid biomarkers in dry eye syndrome using iTRAQ quantitative proteomics. J Proteome Res 8, 4889–4905 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Huang, K. et al. Proteomics approach identifies aqueous humor biomarkers in retinal diseases. Commun Med (Lond) 5, 134 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Rinsky, B. et al. Analysis of the Aqueous Humor Proteome in Patients With Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 62, 18 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.-H. et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of aqueous humor from patients with drusen and reticular pseudodrusen in age-related macular degeneration. BMC Ophthalmol 18, 289 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Yoon, E. G., Nam, K. T., Choi, M., Choi, K.-E. & Yun, C. Aqueous Humor Levels of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Patients With Dry Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Subretinal Drusenoid Deposits. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 66, 10 (2025). [CrossRef]

- García-Quintanilla, L. et al. Recent Advances in Proteomics-Based Approaches to Studying Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci 23, 14759 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-Y., Wang, J., Qin, B. & Tan, Y. Investigating the causal link between gut microbiota and dry age-related macular degeneration: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Int J Ophthalmol 17, 1723–1730 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J., Zhang, J. Y., Luo, W., He, P. C. & Skondra, D. The Emerging Role of Gut Microbiota in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Am J Pathol 193, 1627–1637 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Ambati, J. & Fowler, B. J. Mechanisms of age-related macular degeneration. Neuron 75, 26–39 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Wong, D. T. et al. Imaging Biomarkers and Their Impact on Therapeutic Decision-Making in the Management of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmologica 244, 265–280 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, P. K. et al. RETINAL FLUID AND THICKNESS AS MEASURES OF DISEASE ACTIVITY IN NEOVASCULAR AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION. Retina 41, 1579–1586 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Rispoli, M. et al. Practical guidance for imaging biomarkers in exudative age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol 68, 615–627 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Litts, K. M. et al. Quantitative Analysis of Outer Retinal Tubulation in Age-Related Macular Degeneration From Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography and Histology. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 57, 2647–2656 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Hammer, M. et al. Fundus autofluorescence intensity, lifetime, and spectral imaging in age-related macular degeneration. Experimental Eye Research 258, 110500 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Schlecht, A. et al. Transcriptomic Characterization of Human Choroidal Neovascular Membranes Identifies Calprotectin as a Novel Biomarker for Patients with Age-Related Macular Degeneration. The American Journal of Pathology 190, 1632–1642 (2020). [CrossRef]

- ElShelmani, H., Brennan, I., Kelly, D. J. & Keegan, D. Differential Circulating MicroRNA Expression in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Int J Mol Sci 22, 12321 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kauppinen, A., Paterno, J. J., Blasiak, J., Salminen, A. & Kaarniranta, K. Inflammation and its role in age-related macular degeneration. Cell Mol Life Sci 73, 1765–1786 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Beatty, S., Koh, H., Phil, M., Henson, D. & Boulton, M. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol 45, 115–134 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Proteomics approach identifies aqueous humor biomarkers in retinal diseases | Communications Medicine. https://www.nature.com/articles/s43856-025-00862-2.

- Caban, M., Owczarek, K. & Lewandowska, U. The Role of Metalloproteinases and Their Tissue Inhibitors on Ocular Diseases: Focusing on Potential Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci 23, 4256 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S. et al. Correlation of Aqueous, Vitreous, and Serum Protein Levels in Patients With Retinal Diseases. Transl Vis Sci Technol 12, 9 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Nobl, M. et al. Proteomics of vitreous in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Experimental Eye Research 146, 107–117 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, L. G. et al. Seven new loci associated with age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet 45, 433–439 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Kaur, I., Rathi, S. & Chakrabarti, S. Variations in TIMP3 are associated with age-related macular degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, E112–E113 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Churchill, A. J. et al. VEGF polymorphisms are associated with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Hum Mol Genet 15, 2955–2961 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Yu, C. et al. Predictive Performance of an Updated Polygenic Risk Score for Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology 131, 880–891 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Schiavone, N. et al. Exploring the Gut Microbiota–Retina Axis: Implications for Health and Disease. Microorganisms 13, 1101 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y. et al. MiR-21-5p promotes RPE cell necroptosis by targeting Peli1 in a rat model of AMD. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim (2025) doi:10.1007/s11626-025-01064-9. [CrossRef]

- Merkle, C. W., Augustin, M., Harper, D. J., Glösmann, M. & Baumann, B. Degeneration of Melanin-Containing Structures Observed Longitudinally in the Eyes of SOD1-/- Mice Using Intensity, Polarization, and Spectroscopic OCT. Transl Vis Sci Technol 11, 28 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. et al. Alterations of the intestinal microbiota in age-related macular degeneration. Front Microbiol 14, 1069325 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Luo, W. & Skondra, D. Implication of gut microbiome in age-related macular degeneration. Neural Regen Res 18, 2699–2700 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Fabian-Jessing, B. K. et al. Animal Models of Choroidal Neovascularization: A Systematic Review. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 63, 11 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y. J., Lim, D., Byeon, S. H., Shin, E.-C. & Chung, H. Chemokine Receptor Profiles of T Cells in Patients with Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Yonsei Med J 63, 357–364 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Sennlaub, F. et al. CCR2(+) monocytes infiltrate atrophic lesions in age-related macular disease and mediate photoreceptor degeneration in experimental subretinal inflammation in Cx3cr1 deficient mice. EMBO Mol Med 5, 1775–1793 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Masli, S., Sheibani, N., Cursiefen, C. & Zieske, J. Matricellular protein thrombospondin : influence on ocular angiogenesis, wound healing and immuneregulation. Curr Eye Res 39, 759–774 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Abokyi, S., To, C.-H., Lam, T. T. & Tse, D. Y. Central Role of Oxidative Stress in Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Evidence from a Review of the Molecular Mechanisms and Animal Models. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2020, 7901270 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Huberman, A. D. & Niell, C. M. What can mice tell us about how vision works? Trends Neurosci 34, 464–473 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Voigt, A. P. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics of the human retinal pigment epithelium and choroid in health and macular degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 24100–24107 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy, U. et al. Clinical risk factors for age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Ophthalmol 10, 31 (2010). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).