Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Construction and Expression of Recombinant FN9-10ELP Fusion Protein

2.2. hTMSCs Culture and Preparation

2.3. Cell proliferation Assay

2.4. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

2.6. DAPI Staining and Nuclear Size Analysis

2.7. Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase (SA-β-gal) Staining

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

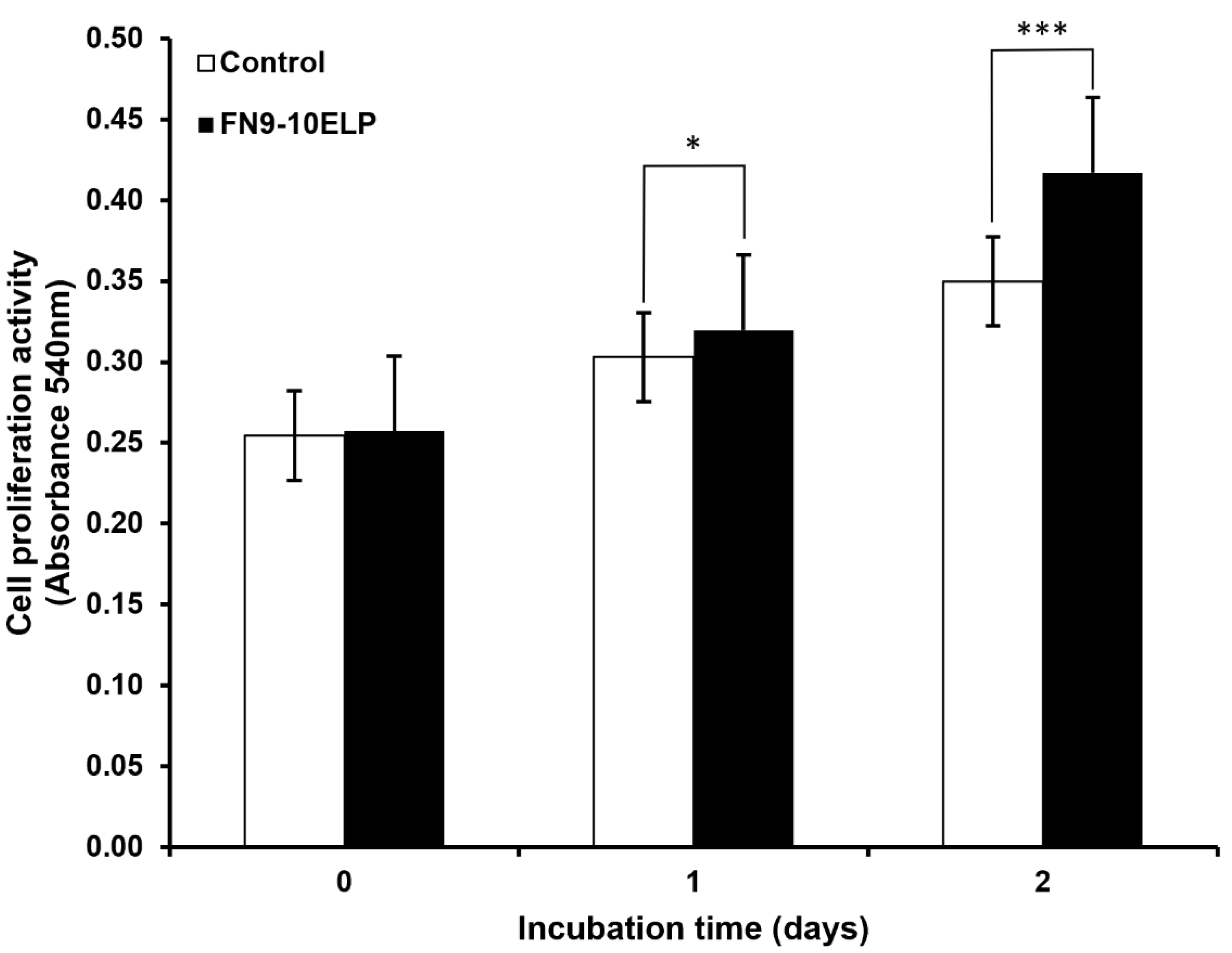

3.1. FN9-10ELP Protects hTMSCs from Etoposide-Induced Cellular Senescence by Promoting Viability

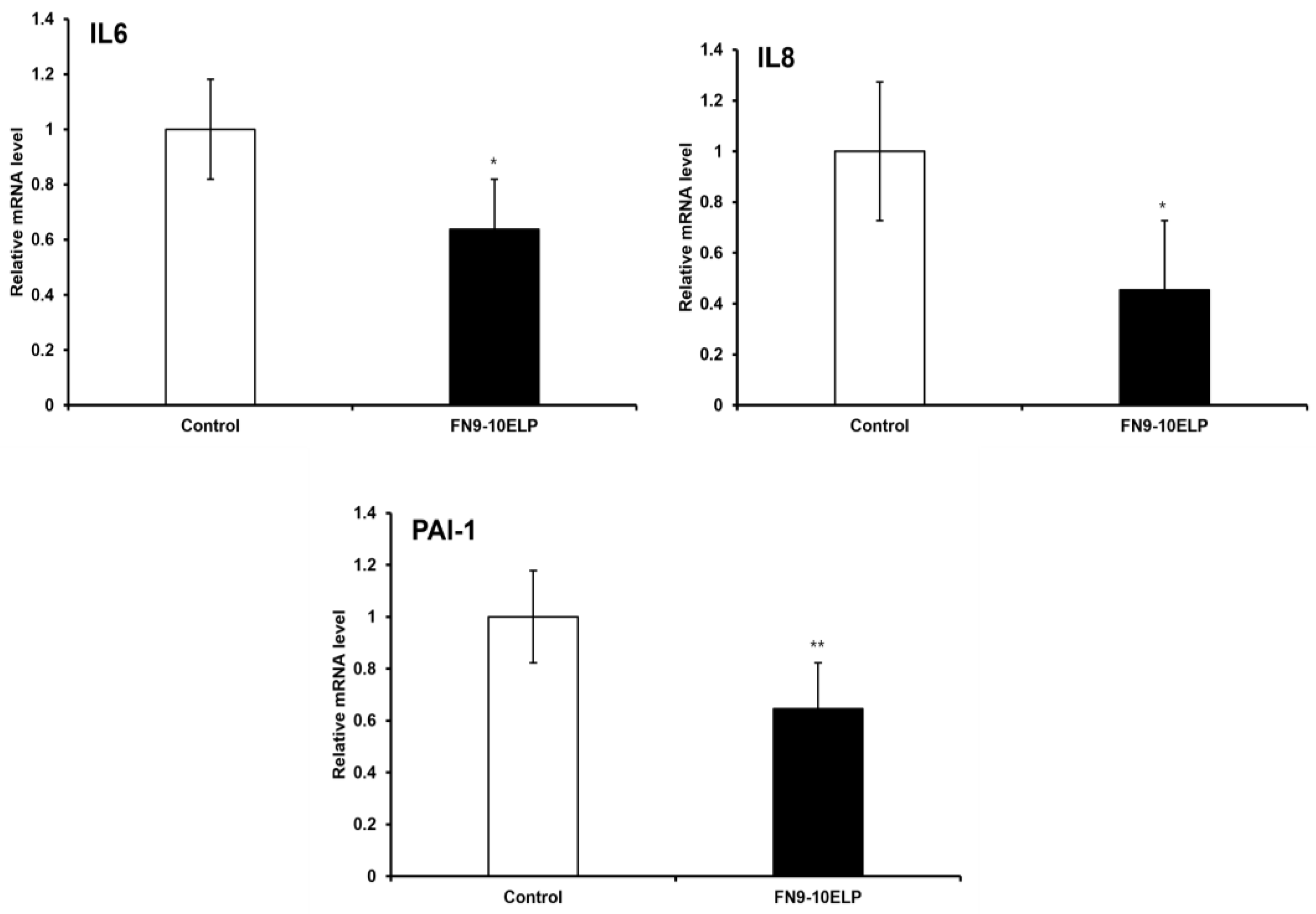

3.2. FN9-10ELP Suppresses the Expression of Senescence-Associated Genes in Etoposide-Treated hTMSCs

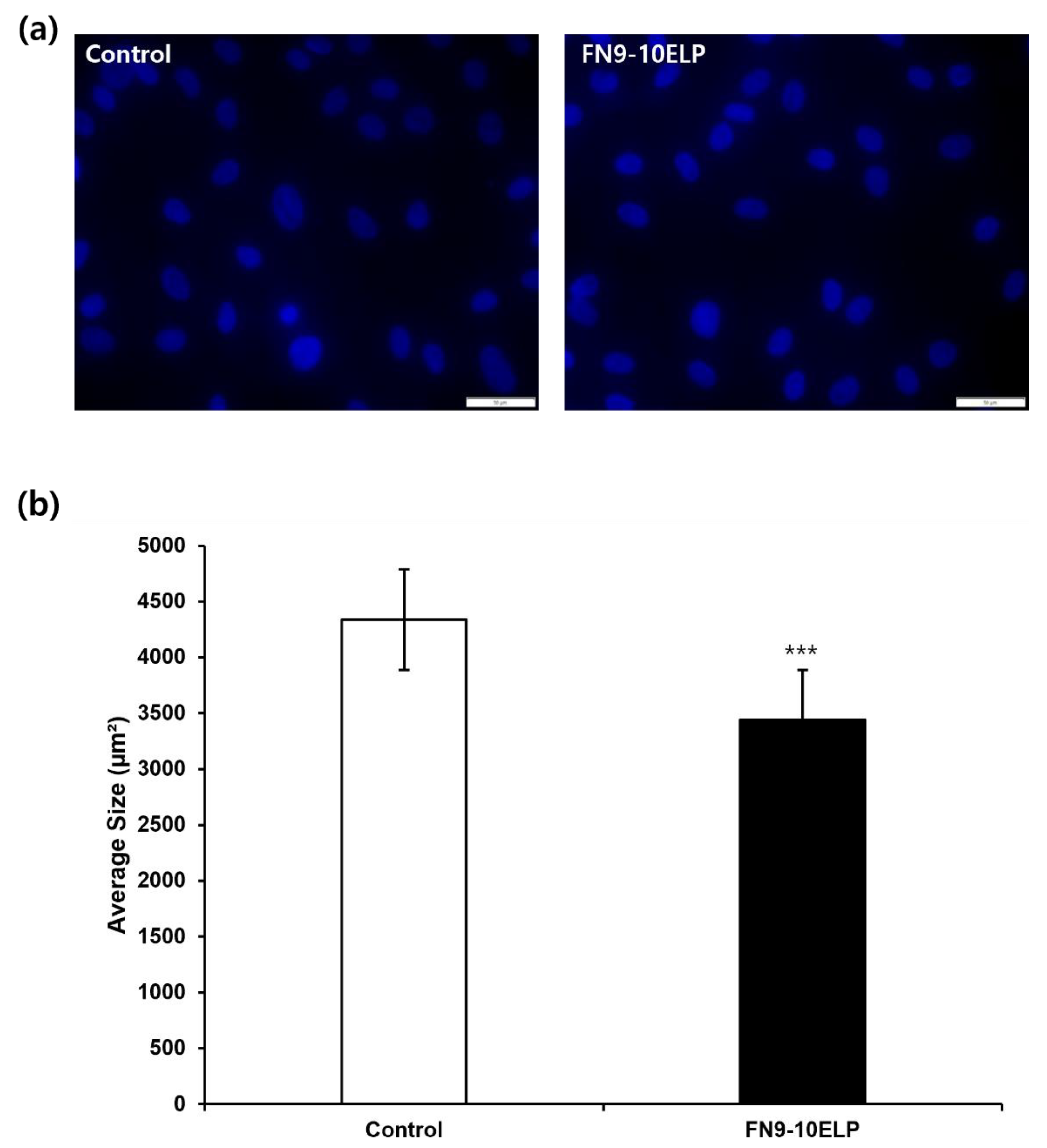

3.3. FN9-10ELP Attenuates Nuclear Enlargement Induced by Etoposide

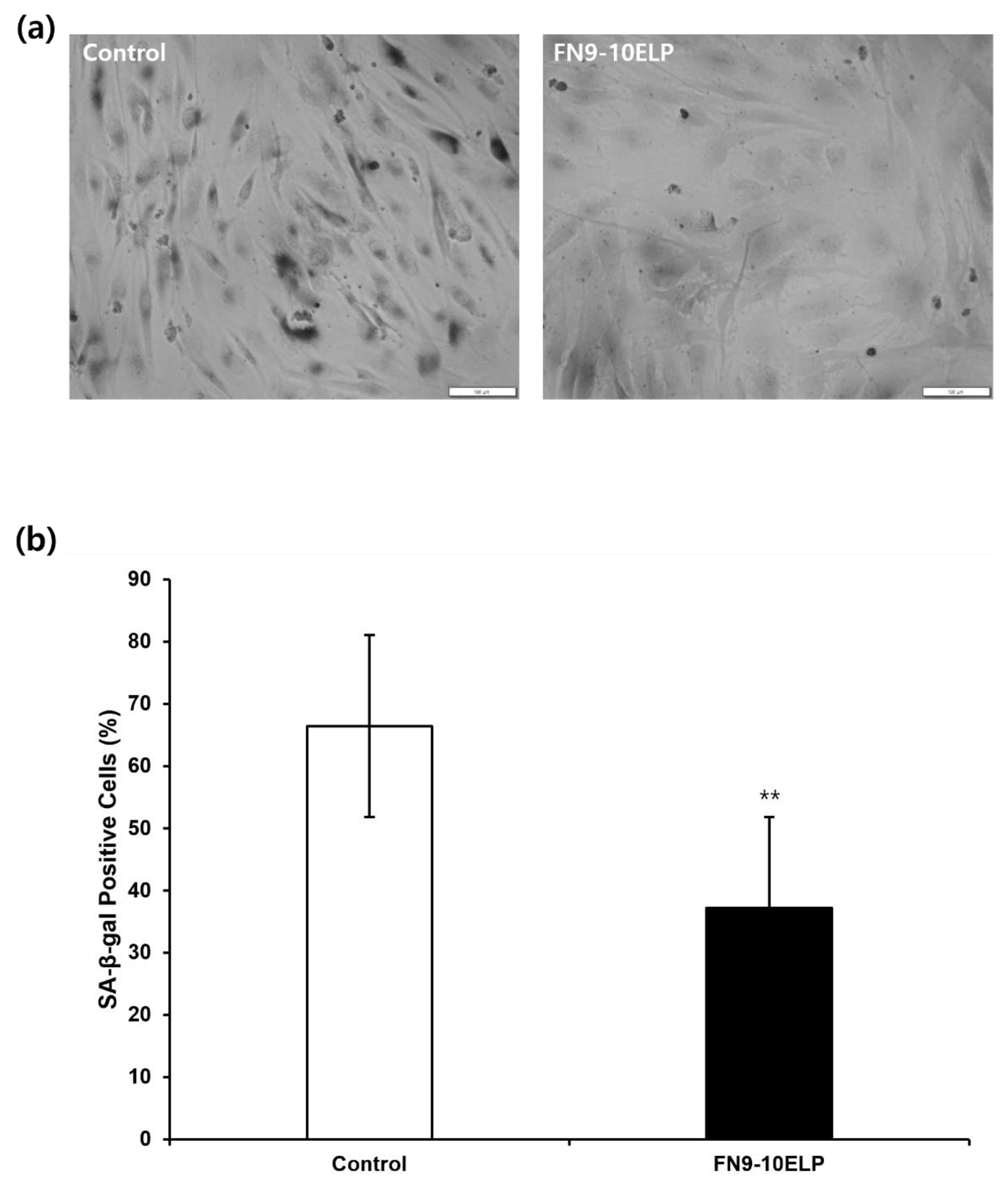

3.4. FN9-10ELP Significantly Suppresses Etoposide-Induced SA-β-Galactosidase Activitity in Senescent hTMSCs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DAPI | 4′,6′-Diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| DDR | DNA damage response |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| DPBS | Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| DSBs | DNA double-strand breaks |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| ELPs | Elastin-like polypeptides |

| FAK | Focal Adhesion Kinase |

| FN | Fibronectin |

| FN9-10ELP | fusion protein of fibronectin type III domains 9-10 and elastin-like polypeptide |

| hMSCs | Human mesenchymal stem cells |

| hTMSCs | Human turbinate-derived mesenchymal stem cells |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| LB-Amp | Luria Broth containing ampicillin |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| mRNA | Messenger Ribonucleic Acid |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| PAI-1 | Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 |

| PI3K | phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SA- β-gal | Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase |

| SASP | Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| SEM | Standard Error of the Mean |

| TLRs | Toll-like receptors |

| TNF- α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha |

| α-MEM | α-minimal essential medium |

References

- Campisi, J. Aging, Cellular Senescence, and Cancer. Annu Rev Physiol 2013, 75, 685–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Otin, C., M. A. Blasco, L. Partridge, M. Serrano, and G. Kroemer. “The Hallmarks of Aging.” Cell 153, no. 6 (2013): 1194–217.

- Childs, B.G.; Gluscevic, M.; Baker, D.J.; Laberge, R.-M.; Marquess, D.; Dananberg, J.; van Deursen, J.M. Senescent cells: an emerging target for diseases of ageing. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 718–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Espín, D.; Serrano, M. Cellular senescence: from physiology to pathology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokland, K.E.; Pouwels, S.D.; Schuliga, M.; Knight, D.A.; Burgess, J.K. Regulation of cellular senescence by extracellular matrix during chronic fibrotic diseases. Clin. Sci. 2020, 134, 2681–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jean, C.; Gravelle, P.; Fournie, J.-J.; Laurent, G. Influence of stress on extracellular matrix and integrin biology. Oncogene 2011, 30, 2697–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rashidy, A.A.; El Moshy, S.; Radwan, I.A.; Rady, D.; Abbass, M.M.S.; Dörfer, C.E.; El-Sayed, K.M.F. Effect of Polymeric Matrix Stiffness on Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem/Progenitor Cells: Concise Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jiang, X.; Huang, B.; Zhou, W.; Cui, X.; Zheng, C.; Liu, F.; Bi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, H.; et al. Inhibition of matrix stiffness relating integrin β1 signaling pathway inhibits tumor growth in vitro and in hepatocellular cancer xenografts. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.R.; A Cho, K.; Kang, H.T.; Bin Lee, J.; Kaeberlein, M.; Suh, Y.; Chung, I.K.; Park, S.C. Restoration of senescent human diploid fibroblasts by modulation of the extracellular matrix. Aging Cell 2011, 10, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. H., J. Turnbull, and S. Guimond. “Extracellular Matrix and Cell Signalling: The Dynamic Cooperation of Integrin, Proteoglycan and Growth Factor Receptor.” J Endocrinol 209, no. 2 (2011): 139–51.

- Altroff, H.; Schlinkert, R.; van der Walle, C.F.; Bernini, A.; Campbell, I.D.; Werner, J.M.; Mardon, H.J. Interdomain Tilt Angle Determines Integrin-dependent Function of the Ninth and Tenth FIII Domains of Human Fibronectin. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 55995–56003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aota, S.; Nomizu, M.; Yamada, K. The short amino acid sequence Pro-His-Ser-Arg-Asn in human fibronectin enhances cell-adhesive function. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 24756–24761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.; Dzuricky, M.; Chilkoti, A. Elastin-like polypeptides as models of intrinsically disordered proteins. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 2477–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despanie, J.; Dhandhukia, J.P.; Hamm-Alvarez, S.F.; MacKay, J.A. Elastin-like polypeptides: Therapeutic applications for an emerging class of nanomedicines. J. Control. Release 2016, 240, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangthem, V.; Sharma, H.; Goel, R.; Ghose, S.; Park, R.-W.; Mohanty, S.; Chaudhuri, T.K.; Dinda, A.K.; Singh, T.D. Application of elastin-like polypeptide (ELP) containing extra-cellular matrix (ECM) binding ligands in regenerative medicine. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 207, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Mackay, A.M.; Beck, S.C.; Jaiswal, R.K.; Douglas, R.; Mosca, J.D.; Moorman, M.A.; Simonetti, D.W.; Craig, S.; Marshak, D.R. Multilineage Potential of Adult Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Science 1999, 284, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.H.; Hwang, S.H. Human Nasal Turbinate-Derived Stem Cells for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. J. Rhinol. 2024, 31, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.S.; Kim, S.W.; Kwon, D.Y.; Park, S.H.; Son, A.R.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, M.S. In vivo osteogenic differentiation of human turbinate mesenchymal stem cells in an injectable in situ-forming hydrogel. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 5337–5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.H.; Cho, H.K.; Park, S.H.; Lee, W.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, D.C.; Oh, J.H.; Park, S.H.; Kim, T.-G.; Sohn, H.-J.; et al. Toll like Receptor 3 & 4 Responses of Human Turbinate Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Stimulation by Double Stranded RNA and Lipopolysaccharide. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e101558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, W.; Bork, S.; Horn, P.; Krunic, D.; Walenda, T.; Diehlmann, A.; Benes, V.; Blake, J.; Huber, F.-X.; Eckstein, V.; et al. Aging and Replicative Senescence Have Related Effects on Human Stem and Progenitor Cells. PLOS ONE 2009, 4, e5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- te Poele, R. H., A. L. Okorokov, L. Jardine, J. Cummings, and S. P. Joel. “DNA Damage Is Able to Induce Senescence in Tumor Cells in Vitro and in Vivo.” Cancer Res 62, no. 6 (2002): 1876–83.

- Malaise, O.; Tachikart, Y.; Constantinides, M.; Mumme, M.; Ferreira-Lopez, R.; Noack, S.; Krettek, C.; Noël, D.; Wang, J.; Jorgensen, C.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell senescence alleviates their intrinsic and seno-suppressive paracrine properties contributing to osteoarthritis development. Aging 2019, 11, 9128–9146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Hu, D.; Zhang, L.; Shi, S. ALKBH5 regulates etoposide-induced cellular senescence and osteogenic differentiation in osteoporosis through mediating the m6A modification of VDAC3. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammaro, M.; Barr, P.; Ricci, B.; Yan, H.; Bielinsky, A.-K. Replication-Dependent and Transcription-Dependent Mechanisms of DNA Double-Strand Break Induction by the Topoisomerase 2-Targeting Drug Etoposide. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e79202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslimović, A.; Nyström, S.; Gao, Y.; Hammarsten, O.; Sullivan, B.A. Numerical Analysis of Etoposide Induced DNA Breaks. PLOS ONE 2009, 4, e5859–e5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.-E.; Seo, H.-J.; Jang, J.-H. Design of fibronectin type III domains fused to an elastin-like polypeptide for the osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Acta Biochim. et Biophys. Sin. 2019, 51, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.-H.; Jeong, E.-S.; Lee, S.; Jang, J.-H.; Papaccio, G. Bio-functionalization and in-vitro evaluation of titanium surface with recombinant fibronectin and elastin fragment in human mesenchymal stem cell. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0260760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, L.B.H.; Yoo, Y.; Park, S.H.; Back, S.A.; Kim, S.W.; Bjørge, I.; Mano, J.; Jang, J. Investigating the effect of fibulin-1 on the differentiation of human nasal inferior turbinate-derived mesenchymal stem cells into osteoblasts. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2017, 105, 2291–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoddam, A.; Vaughan, D.; Wilsbacher, L. Role of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) in age-related cardiovascular pathophysiology. J. Cardiovasc. Aging 2025, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, A.; Orjalo, A.V.; Desprez, P.-Y.; Campisi, J. Inflammatory networks during cellular senescence: causes and consequences. Trends Mol. Med. 2010, 16, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez, J.A.; Alarcón, T. Senescence-Inflammatory Regulation of Reparative Cellular Reprogramming in Aging and Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, R.U.; Soujanya, M.; Mishra, R.K. Deterioration of nuclear morphology and architecture: A hallmark of senescence and aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 67, 101264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckenbach, I.; Mkrtchyan, G.V.; Ben Ezra, M.; Bakula, D.; Madsen, J.S.; Nielsen, M.H.; Oró, D.; Osborne, B.; Covarrubias, A.J.; Idda, M.L.; et al. Nuclear morphology is a deep learning biomarker of cellular senescence. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimri, G.P.; Lee, X.; Basile, G.; Acosta, M.; Scott, G.; Roskelley, C.; Medrano, E.E.; Linskens, M.; Rubelj, I.; Pereira-Smith, O.; et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 9363–9367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tragoonlugkana, P., C. Pruksapong, P. Ontong, W. Kamprom, and A. Supokawej. “Fibronectin and Vitronectin Alleviate Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Senescence during Long-Term Culture through the Akt/Mdm2/P53 Pathway.” Sci Rep 14, no. 1 (2024): 14242.

- Matsuo, M.; Sakurai, H.; Ueno, Y.; Ohtani, O.; Saiki, I. Activation of MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways by fibronectin requires integrin αv-mediated ADAM activity in hepatocellular carcinoma: A novel functional target for gefitinib. Cancer Sci. 2006, 97, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veevers-Lowe, J.; Ball, S.G.; Shuttleworth, A.; Kielty, C.M. Mesenchymal stem cell migration is regulated by fibronectin through α5β1-integrin-mediated activation of PDGFR-β and potentiation of growth factor signals. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 1288–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genes | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin | TGGCACCCAGCACAATGAAGAT | TACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCA |

| IL-6 | CCCCTGACCCAACCACAAAT | GCCCAGTGGACAGGTTTCTG |

| IL-8 | GTCTGCTAGCCAGGATCCAC | AGTGCTTCCACATGTCCTCA |

| PAI-1 | CAGACCAAGAGCCTCTCCAC | GGTTCCATCACTTGGCCCAT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).