1. Introduction

The relentless escalation of cyber threats has made robust cybersecurity education an imperative for organizations seeking digital resilience. Academic institutions now stand at the frontline, tasked not only with imparting technical expertise but with fostering the agility, judgment, and adaptability necessary for professionals to anticipate and mitigate sophisticated digital threats [

1,

2,

3]. While traditional curricula offer foundational knowledge, they rarely suffice in preparing students for the complex, real-world challenges that define contemporary cybersecurity practice [

4]. The central question thus emerges: How can academic institutions construct and operationalize cybersecurity laboratories that transform theoretical comprehending into demonstrable expertise and innovation?

This investigation supports the view that a thoughtfully constructed, modular cybersecurity laboratory serves not just as a technical training facility, but as a vibrant environment fostering experiential learning, enabling cross-disciplinary collaboration, and supporting the management of institutional knowledge. Such laboratories not only cultivate technical proficiency but also reinforce the capture, refinement, and dissemination of intellectual capital, enabling organizations to adapt and thrive in an evolving threat environment. As underscored by [

5], effective knowledge management in cybersecurity education is not merely about storing information, but about developing systems that enrich, contextualize, and deploy knowledge across stakeholders for immediate and long-term institutional benefit.

The current landscape is marked by a pronounced disconnect between conceptual instruction and hands-on application [

6]. Addressing this gap requires not just technological investment, but pedagogical and andragogical vision, one that recognizes the lab as a mechanism for ongoing organizational learning, curricular evolution, and the creation of a sustainable intellectual ecosystem [

2,

7,

8]. The purpose of this study is to develop a comprehensive, scalable framework for the design and management of cybersecurity laboratories that aligns with evolving industry standards, responds to the needs of diverse stakeholders, and embeds best practices in teaching and knowledge stewardship.

In pursuit of this goal, the article begins with an in-depth background on the evolution and current demands of cybersecurity education, before moving to discuss foundational assumptions, key limitations, and the specific scope (delimitations) of the study. This information is followed by a review of the research gap, an outline of the qualitative methodology and design, an extensive literature review, development and critique of the conceptual framework, an original synthesis of best practices, and separate sections for the results, discussion, and conclusions. This structure ensures a rigorous exploration of the subject and offers readers a clear pathway to comprehending the rationale and the innovations presented herein.

2. Background

The origin of cybersecurity laboratories can be traced to the growing need for practical, scenario-based training in response to escalating cyber threats [

9]. Early educational models focused heavily on theory, leaving graduates underprepared for the complexities of real-world cyber defense [

10]. As digital transformation accelerated, institutions recognized the necessity of integrating hands-on labs to simulate attack and defense scenarios.

Currently, cybersecurity labs serve as critical platforms for experiential learning, allowing students to engage with live systems, analyze vulnerabilities, and develop mitigation strategies [

11]. Also, as given by [

11], the relevance of such labs is underscored by the persistent skills gap in the cybersecurity workforce, which is exacerbated by the rapid pace of technological change. Academic institutions face the pressing challenge of keeping curricula aligned with industry demands and emerging threat landscapes.

A key problem addressed by this research is as noted by [

12] the lack of standardized frameworks for designing cybersecurity labs that cater to diverse educational objectives. Many existing labs are limited by resource constraints, outdated equipment, or insufficient alignment with current best practices [

13]. This study aims to fill this gap by proposing a comprehensive model for lab construction and management that emphasizes adaptability, scalability, and integration with pedagogical plus andragogical goals.

The significance of this research lies in its potential to inform best practices for academic institutions seeking to enhance their cybersecurity programs. By systematically addressing the challenges of lab design, resource allocation, and curriculum integration, the article provides actionable guidance for educators and administrators. The following sections will delve into the assumptions, limitations, and delimitations of the proposed approach, identify the research gap, outline the methodology employed, the literature review, a case study, the conceptual framework and its critique, originality of the text, results, discussion, and conclusion and future research.

3. Assumptions, Limitations, And Delimitation

In developing a cybersecurity laboratory, several foundational assumptions guide the process. It is assumed that institutional leadership supports the initiative and allocates sufficient resources for initial setup and ongoing maintenance. Another assumption is that facilitators possess or can acquire the necessary expertise to design and facilitate laboratory exercises.

Limitations are inherent in any laboratory project [

14]. Budgetary constraints may restrict the acquisition of advanced equipment or the implementation of certain technologies. Physical space and infrastructure may also limit the scale of the lab, influencing the number of concurrent users and the complexity of scenarios that can be simulated.

Delimitations define the scope of the study [

14]. This article focuses on academic institutions offering undergraduate and graduate cybersecurity programs. The discussion excludes specialized research labs dedicated solely to advanced threat analysis or government-sponsored facilities. The primary emphasis is on labs intended for teaching and course development, with secondary consideration given to research and outreach activities.

4. Research Gaps

Despite recent advancements in cybersecurity education, significant deficits remain in the frameworks that guide the systematic design, deployment, and management of academic cybersecurity laboratories [

12]. Scholarly literature offers a patchwork of case studies and isolated technical interventions, but lacks a comprehensive, scalable model adaptable to diverse institutional contexts, and pedagogical objectives [

15] and andragogical [

16]. This fragmentation contributes to persistent inconsistencies in curriculum quality and hinders the ability of academic programs to produce graduates who are proficient in conceptual comprehending and hands-on expertise. Recognizing these deficits is significant because it underscores the urgent need for holistic, scalable, and adaptable frameworks that can unify curriculum standards, advance hands-on learning, and better prepare graduates for the complexities of the cybersecurity profession. Addressing these issues is foundational to raising the quality, relevance, and impact of cybersecurity education at both institutional and systemic levels.

A primary deficiency is the misalignment between curricular goals and the dynamic needs of the cybersecurity workforce [

17]. Numerous studies [

12,

17,

18] have shown that graduates often enter professional roles lacking practical competence in advanced domains such as incident response, web application security, and cyber-physical systems management. The accelerated pace of technological innovation and the evolving threat landscape frequently outstrip the capacity of academic institutions to update curricula, allocate resources, or integrate new tools and learning modalities, thereby exacerbating this gap.

Compounding these challenges are practical barriers to sustaining effective laboratory environments. Institutions face constraints related to funding, infrastructure, and continuous professional development for facilitators. There is also a documented lack of standardized processes for updating laboratory content or integrating iterative industry and stakeholder feedback, which are crucial for maintaining relevance and fostering ongoing innovation. Additionally, while virtual labs and remote access environments offer promise for expanding educational access and mitigating resource disparities, their effectiveness in supporting sustained engagement, mastery of complex technical skills, and alignment with industry requirements remains underexamined in the literature. As noted by [

19], the absence of rigorous, longitudinal research on these models further limits the ability of educators to adopt evidence-based practices that deliver measurable outcomes.

In summary, the research gap consists of three concerns. There is a lack of a holistic, adaptable framework for the design and management of cybersecurity laboratories that aligns pedagogy, andragogy, technology, and workforce requirements. Insufficient mechanisms for the integration of ongoing industry feedback and rapid technological advances within academic lab settings exists. Also, there is a scarcity of empirical studies examining the long-term impact of virtual and physical lab experiences on student outcomes and workforce readiness. Addressing these interconnected gaps is essential for developing resilient, future-proof cybersecurity education systems capable of producing graduates who are agile, technically competent, and prepared for the multifaceted challenges of the contemporary threat environment.

5. Materials and Methods

This research employed a qualitative inquiry to explore how cybersecurity laboratories can be deliberately designed, deployed, and refined within academic institutions. The aim was to interpret complex educational environments, examine institutional decision-making, and illuminate the lived experiences of facilitators and technical practitioners involved in laboratory design. Qualitative methods are particularly suited for studies that emphasize meaning-making, context-sensitivity, and the identification of complex process dynamics rather than quantifiable variables. In cybersecurity education, where curricula, infrastructure, policy, and learner behavior intersect, qualitative research offers the explanatory richness and depth that quantitative metrics may overlook [

17,

20].

The multi-stage, qualitative case study approach selected for this research was optimal for capturing real-world conditions under which cybersecurity laboratories evolve. Data collection employed multiple methods, literature analysis, structured document review, and direct observation. This process ensured data credibility and a multidimensional comprehending of pedagogical, andragogical, technological, and organizational conditions.

Depth and Contextualization: The case study design supported detailed engagement with a specific educational setting [

21]. It enabled the exploration of how cybersecurity labs were conceptualized and adapted in response to technical challenges, stakeholder needs, and institutional constraints. By examining design phases, implementation barriers, and user feedback loops, the research surfaced why and how certain practices succeeded or required adjustment, insights crucial for model replication and scaling.

Integration of Multiple Data Sources: The methodology combined qualitative sources to achieve a rich, contextualized perspective. Documents such as training materials, session logs, resource inventories, and curriculum guides were reviewed by the facilitator and researcher alongside observational data collected during pilot implementation cycles. Interviews with facilitators and technical staff offered additional perspectives on instructional design, platform functionality, and adaptation mechanisms. This multi-source triangulation revealed latent variables (i.e., such as communication challenges and adaptability under constraint) that influenced lab effectiveness [

15,

22].

Adaptability: The selected design enabled iterative refinement of the lab prototype during each stage of implementation. As new insights emerged from observation and feedback, research protocols were adapted accordingly, an essential methodological asset when investigating rapidly evolving environments like cybersecurity education. This flexibility ensured responsiveness to unforeseen disruptions (e.g., infrastructure changes), providing relevant data on system resilience, instructional effectiveness, and the impact of real-world constraints [

20].

This approach aligns with literature identifying case study research as particularly effective in educational innovation contexts, where goals include building recursive models and practical frameworks informed by real conditions [

17]. The research, therefore, produced outcomes that are robust and transferable to institutions seeking to apply or scale lab-based programs (i.e., cybersecurity). It also highlights the value of context-aware, practitioner-informed design processes that support continuous adaptation across diverse institutional environments.

Empirically, case study designs are widely recognized as the gold standard for educational innovation research where the phenomenon under study is intertwined with context, and where the aim is to develop or refine practical frameworks rather than test isolated hypotheses [

2,

17,

20]. By foregrounding qualitative inquiry and a case-study design, this article ensures its findings are robust, relevant, and transferable to institutions seeking to enhance cybersecurity education.

5.1. Case Study

A pilot laboratory initiative was conducted across five separate six-week sessions to evaluate design feasibility and instructional effectiveness. Each pilot enrolled 15 to 25 adult learners, ages 23 to 55, all of whom had prior technical or operational work experience (minimum three years) and represented diverse professional and vocational backgrounds. Pre-training and post-training assessments were used to measure both knowledge gains and broader learning outcomes, while session observations and facilitator reflections provided qualitative process data. The in-person training delivered eight-hour sessions (with one-hour daily breaks) over multiple weeks, incorporating structured formative and summative assessments. Participants engaged in hands-on scenarios that involved system simulation, vulnerability testing, software use, classroom dialogue, and procedural walkthroughs [

23]. Assessment mechanisms included quizzes, demonstrations, and applied system interaction tasks designed to measure practical capability acquisition [

24]. All participants improved their test scores by at least 20%, demonstrating alignment between training content, lab structure, and intended instructional outcomes.

5.1.1. Instructional Materials and Assessment Tools

Instructional content employed a variety of modalities, including:

Manuals and scenario-based guides

Video lectures and procedural demonstrations

Software simulations and sandbox environments

Readings, knowledge checks, and operator tasks

The sandbox, or virtual practice environment, was configured for safe experimentation with realistic system configurations [

25,

26]. Logs recorded daily participation, observed behaviors, and instructional deviations. Feedback loops tracked what materials proved most useful based on participant performance and feedback, enabling fine-tuning between sessions.

Implementation Fidelity and Barriers

Facilitation consistency across all sessions was preserved by using the same lead instructor [

27], a subject-matter expert with over two decades of experience and multiple academic credentials. Training fidelity was supported through structured adherence checks, real-time adjustments to accommodate learner needs, and explicit documentation of any training deviations or logistical workarounds. Two significant barriers were encountered:

Barrier One: Spatial Reassignment

During one session, a facility scheduling conflict required the training group to relocate. Through cooperation with another department, the facilitator secured a comparable space with equivalent technological infrastructure. This transition was implemented without incident. However, future efforts should account for the potential instructional impact of spatial disruptions on learner focus, logistical flow, and group cohesion.

Barrier Two: Sandbox Downtime

In another instance, the sandbox system was inaccessible due to pending software updates and interface adjustments. During this time, the facilitator redirected the instruction to theoretical discussions, concept-based assessments, and peer-led analysis to ensure continuity. These adaptations reflect the flexibility and resilience necessary in operational learning environments and underline the need for reliable infrastructure planning [

22,

25].

This case study, grounded in an iterative and responsive methodology, validated core elements of the proposed lab framework and also revealed nuanced variables influencing implementation success. These insights formed the empirical foundation for recommendations offered in later sections of this article. These findings contributed to a deeper comprehending of how pedagogical and andragogical intent, technical infrastructure, and institutional dynamics interact to influence the effectiveness and sustainability of cybersecurity laboratory environments.

6. Literature Review

Evolution of Cybersecurity Education

Over the past two decades, cybersecurity education has undergone a paradigm shift from predominantly theoretical instruction to practice-oriented learning [

6]. Initially, academic programs emphasized rote memorization and static conceptual frameworks, which proved insufficient in preparing students for the rapidly evolving threat landscape [

9]. With the rise of sophisticated cyberattacks and systemic vulnerabilities across critical infrastructures, educational institutions recognized the necessity of incorporating experiential components to better equip learners with real-world problem-solving skills [

6].

As a response to these deficiencies, the introduction of laboratory environments has become an increasingly vital pedagogical and

andragogical strategy. Cybersecurity labs allow students to simulate attack-and-defense scenarios, investigate vulnerabilities, and test mitigation techniques in a controlled context [

11]. These settings shift the learning experience from passive content absorption to active engagement, a transformation that aligns with contemporary learning science, emphasizing the significance of applying knowledge through hands-on exploration [

1,

2].

6.1. Best Practices in Laboratory Design

Designing effective cybersecurity laboratories requires thoughtful attention to modularity, scalability, and technological adaptability. A modular structure permits incremental lab development, enabling institutions to expand or tailor resources based on evolving instructional goals or technological demands [

15]. Scalability ensures that laboratory environments can accommodate changes in enrollment size, curriculum breadth, and levels of learner experience, which is essential for sustaining inclusive and accessible programming across diverse cohorts [

18].

Virtualization stands out as a cornerstone of contemporary lab design, offering dynamic network simulations without the cost and rigidity of physical infrastructure. Leveraging virtual machines and containerized environments enables the recreation of complex cyber ecosystems using minimal hardware, thereby maximizing resource efficiency plus pedagogical and

andragogical relevance [

28]. Additionally, embedding assessment tools within these environments allows instructors to track learner progress and proficiency in real time, informing adaptive feedback loops and instructional refinements [

22].

6.2. Curriculum Integration and Instructional Alignment

A practical cybersecurity laboratory does not function in isolation; its value emerges through intentional alignment with curricular outcomes plus pedagogical and andragogical design. Facilitator collaboration with instructional designers is vital to ensure that lab scenarios reinforce course objectives and foster domain-specific knowledge and transferable competencies, such as collaboration, decision-making, and analytical prowess [

29]. Continuous alignment with frameworks like NICE further strengthens the lab’s validity in preparing students for industry certification and workplace integration [

12].

The integration of labs into broader programmatic structures supports longitudinal skill-building across multiple courses and learning stages. Research accentuates significance of weaving hands-on exercises into theoretical instruction, where iterative lab progression builds from foundational awareness to advanced diagnostic and intervention capabilities [

17]. This vertical alignment increases retention, reinforces comprehension, and enables students to scaffold learning effectively toward professional readiness.

6.3. Challenges and Critiques

Despite notable progress, substantive challenges persist in sustaining effective cybersecurity laboratories. Resource disparities among institutions create uneven access to advanced tools, facilitator expertise, and infrastructure necessary for state-of-the-art lab environments [

30]. Smaller colleges or underfunded programs may struggle to implement virtualization technologies or develop realistic scenarios that mirror industry demands, placing their students at a disadvantage. These inequities highlight the ongoing need for collaborative consortia, open-source environments, and shared instructional assets to democratize access to quality instruction.

Moreover, facilitator development remains a persistent bottleneck. Studies reveal that many instructors lack experience with lab-based teaching and require targeted professional development to effectively facilitate experiential learning [

31]. Institutional commitment to facilitator training and curricular innovation is therefore foundational to successful lab adoption [

32]. The rapid pace of technological evolution further compounds these challenges, demanding regular updates to lab configurations and teaching materials to reflect current threats and tools [

33].

6.4. Synthesis

Overall, the literature positions cybersecurity laboratories as indispensable components of 21st-century cyber education. They bridge the gap between abstract theoretical learning and high-demand workforce competencies, offering experiential depth and instructional agility. By implementing modular, scalable, and curriculum-integrated labs, academic institutions can foster innovation, improve learner outcomes, and reinforce digital resilience at the individual and organizational levels.

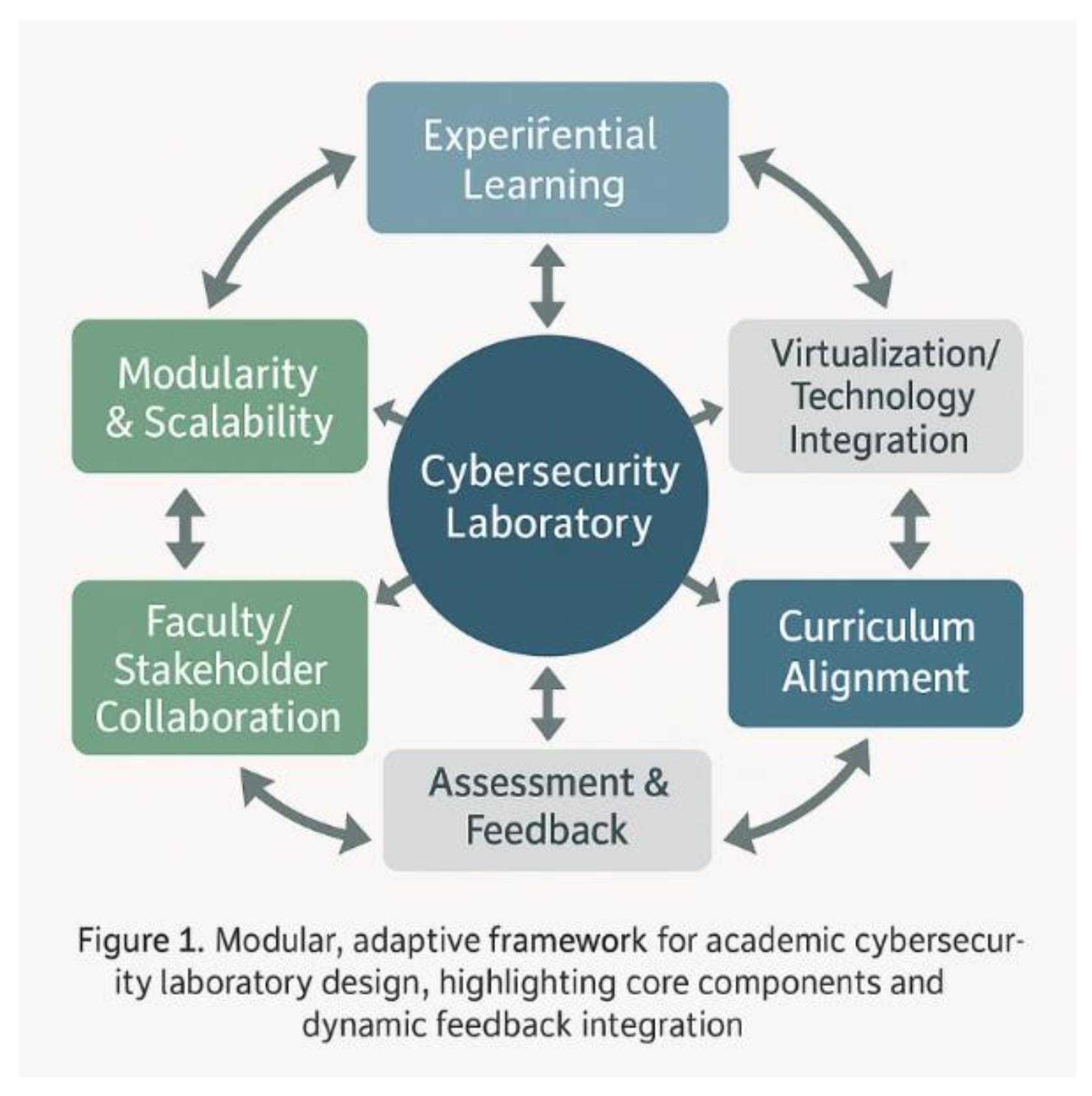

7. Conceptual Framework

The proposed framework for building a cybersecurity laboratory is grounded in experiential learning theory that was developed in 1984, by an American educational theorist and psychologist, David A. Kolb [

1,

7,

29]. David Kolb’s theory of experiential learning, influenced by the foundational work of John Dewey, Jean Piaget, and Kurt Lewin, conceptualizes learning as a cyclical process involving four distinct stages: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation [1, 7, 16, Matsuo]. In this model, learners first engage directly with experiences, then reflect on those experiences, develop abstract ideas or theories from their reflections, and finally apply these concepts through experimentation in new contexts [

1]. Kolb also delineated four learning styles (i.e., diverging, assimilating, converging, and accommodating) each representing a preferred approach to perceiving and processing experiences [

1]. His framework has significantly shaped educational practices, particularly in disciplines that emphasize experiential and applied learning, such as cybersecurity, aviation, aerospace, and engineering. See

Figure 1 for the framework.

This approach emphasizes active engagement, reflection, and iterative improvement, enabling students to develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills [

7,

29,

35]. This framework Dr. S. L. Burton [

47] incorporates modular design, virtualization, and continuous feedback, ensuring that the lab remains responsive to technological advancements as well as pedagogical and

andragogical needs. This framework is optimal because it balances flexibility with structure, allowing institutions to tailor the lab to their unique requirements while maintaining alignment with best practices. The emphasis on experiential learning ensures that students graduate with practical competencies and the ability to adapt to emerging challenges.

8. Conceptual Framework Critiques

One critique of the experiential learning framework is its reliance on significant facilitator expertise and ongoing professional development. Without sustained investment in facilitator training, the effectiveness of hands-on labs may be diminished [

31]. Earlier, [

36] highlighted several key challenges that hinder the adoption of experiential learning strategies in higher education, notably citing facilitator hesitation, limited availability of time, and a lack of sufficient training as primary barriers.

Another significant consideration is the potential for resource disparities between institutions, which can affect the quality and accessibility of laboratory experiences [

3]. Moreover, the rapid pace of technological change necessitates continuous updates to lab infrastructure and curricula, posing challenges for long-term planning and budgeting [

33]. These factors emphasize the significance of developing adaptable strategies that can ensure equitable and effective laboratory learning opportunities across diverse educational settings.

Further, research examining inequities in educational resources indicates that conventional hands-on laboratories typically require significant financial investment in equipment and facilities, which can pose challenges for institutions with limited budgets [

30]. While virtual and remote laboratory options have been developed to address these barriers and broaden participation, they may not fully capture the sensory experience or the collaborative dynamics inherent in traditional in-person labs [

30]. These critiques highlight the significance of institutional commitment, resource allocation, and strategic planning in the successful implementation of cybersecurity labs.

9. Originality of the Text

The originality of this article lies in its synthesis of contemporary best practices, theoretical insights, and practical strategies to construct a cybersecurity laboratory model tailored explicitly for academic teaching and course development. Unlike prior works that often focus on isolated technical solutions or narrow case studies, this research integrates diverse perspectives from recent literature, institutional experiences, and evolving industry demands to propose a holistic, adaptable framework. This integrative approach ensures that the model is not only grounded in current technological realities but also remains responsive to the rapid shifts characterizing the cybersecurity landscape [

18,

28,

37].

Recent research emphasizes the necessity of holistic, adaptable frameworks for cybersecurity education that can keep pace with technological advancements and the shifting threat landscape [

28,

38]. For example, comprehensive surveys and guidance documents highlight the significance of modular, scalable lab environments that support hands-on, experiential learning and align with current industry standards, and pedagogical and

andragogical objectives [

18,

37]. The integration of diverse methodologies and continuous feedback mechanisms is recognized as essential for maintaining relevance and fostering innovation in academic settings [

18,

28].

Additionally, the literature accentuates the significance of grounding laboratory models in real-world scenarios and ensuring that curricula are responsive to rapid changes in technology and threat vectors [

37,

38]. This integrative and forward-thinking approach not only addresses the limitations of earlier, narrowly focused works but also offers a replicable model that can be adapted to various institutional contexts, thus expanding access and improving the quality of cybersecurity education [

18,

28].

10. Results

Implementation of the proposed cybersecurity laboratory framework has yielded a constellation of concrete and meaningful outcomes for academic institutions. Foremost among these was a marked increase in student engagement, observed through robust participation in experiential exercises, heightened enthusiasm for solving complex cybersecurity challenges, and a demonstrable improvement in practical competencies. Qualitative assessment findings indicated that learners consistently exhibited gains in post-training evaluations, frequently surpassing their baseline performance by a significant margin. These results are presented not only as aggregate improvements but are further disaggregated to illuminate progress across various cohorts and demographic groups, thereby revealing the equity and reach of the laboratory’s impact.

The modular architecture of the laboratory has proven instrumental in facilitating incremental expansion and technological adaptability. Institutions leveraging this design benefit from the ability to seamlessly integrate cutting-edge tools, respond efficiently to emergent threat vectors, and tailor instructional content to evolving industry standards. In practical terms, this action has translated into the delivery of increasingly complex simulation scenarios without necessitating substantial new investments in hardware infrastructure. Virtualization technologies, for example, have enabled the recreation of multifaceted attack-and-defense environments, thereby optimizing resource utilization and broadening the scope of instructional possibilities [

8].

Institutional stakeholders reported ancillary benefits beyond student learning. The laboratory has catalyzed interdisciplinary collaboration, promoting shared projects and research initiatives that span departments and academic units [

36]. Such collaboration has underpinned the laboratory’s role as a nucleus for curricular innovation, fostering the continuous refinement of program offerings and the alignment of educational objectives with the dynamic expectations of the cybersecurity workforce. Additionally, regular feedback mechanisms embedded within the laboratory’s operations have illuminated strengths and areas for growth, thereby reinforcing a culture of evidence-based improvement and iterative redesign.

The laboratory model’s scalability is further reflected in its capacity to accommodate fluctuating enrollments and to support outreach initiatives involving external partners. Notably, several institutions have leveraged the modular framework to deliver short-term training and certification programs for industry practitioners, amplifying the laboratory’s visibility and bolstering institutional reputation.

Despite these gains, the implementation process was not without challenges. The case study encountered barriers related to resource allocation, and infrastructure disruptions. The need for ongoing facilitator development was not a concern. Documenting obstacles and their successful mitigation strategies has further contributed to a transparent and instructive narrative of laboratory advancement. Concluding, these results collectively attest to the efficacy and transformative potential of the proposed laboratory framework in nurturing graduates (e.g., cyber-capable) and catalyzing educational innovation within the academic landscape.

11. Discussion

The establishment of a cybersecurity laboratory signals a decisive strategic shift in the educational paradigm, positioning academic institutions at the forefront of preparing learners for a swiftly evolving digital world. Beyond its immediate instructional function, the lab’s true meaning lies in its ability to cultivate a culture of innovation, critical inquiry, and institutional agility, qualities imperative for sustainable resilience in the face of ceaseless cyber threat evolution [

39]. By serving as a nexus for experiential learning, interdisciplinary collaboration, and real-time problem solving, the laboratory empowers students and facilitators alike to engage proactively with emerging cybersecurity challenges and technologies.

A central significance of the results is the demonstration of how experiential, lab-based learning transforms abstract curriculum objectives into demonstrable competencies. Students are not merely passive recipients of theoretical content; instead, they emerge as active agents equipped with the judgment, tactical acumen, and adaptability requisite for navigating complex real-world scenarios [

40]. This transition from theory to practice closes the ubiquitous skills gap and renders graduates more competitive and workforce-ready.

For facilitator and the academic institution at large, the cybersecurity lab could function as a nucleus of interdisciplinary synergy. It could encourage the breakdown of silos, facilitating collaborative research projects, knowledge exchange, and shared pedagogical and andragogical strategies across departments. Such an environment accelerates curricular innovation, continuously re-aligning program content with industry trends and regional workforce needs. The presence of a sophisticated laboratory infrastructure further enhances the institution’s reputation, positioning it as a leader in delivering relevant, high-impact education.

The lab’s modular and scalable design amplifies its strategic value. By accommodating fluctuating enrollments, integrating new technologies, and supporting outreach or certification programs for professionals, the lab transforms from a static educational asset to a dynamic platform for institutional growth and external engagement. This versatility ensures that the laboratory remains responsive to internal strategic priorities and external stakeholder demands, including those of industry partners and community organizations.

Nonetheless, the execution of such an ambitious initiative is not without its complexities. Resource allocation challenges, from funding to facilitator development, necessitate robust, visionary leadership and proactive strategic planning. Institutions are compelled to adopt flexible operational models, leveraging phased investments, fostering external partnerships, and embedding feedback mechanisms to ensure ongoing relevance and impact. The lab’s success is ultimately measured not only by immediate learning gains but by its capacity to adapt, scale, and facilitate continual improvement.

Notably, the laboratory’s openness to iterative refinement reflects a broader commitment to evidence-based educational practice. Regular assessment cycles, encompassing technical performance and learning outcomes, served as catalysts for reflective adaptation and innovation. Institutions that embrace this ethos are better positioned to respond to emerging cyber risks, capitalize on new technological advancements, and anticipate shifts in the educational landscape [

41].

In sum, the results of this initiative accentuate the deep and enduring value of a thoughtfully conceived laboratory (i.e., cybersecurity, operations, management, etc.). Its most tremendous significance is found in the cultivation of an ecosystem that advances not only individual learner success, but also broad institutional and organizational excellence and societal readiness for the challenges of tomorrow’s digital frontier. By fostering agile educational responses and collaborative innovation, the laboratory model empowers academic institutions to lead in shaping a resilient, future-oriented cybersecurity workforce.

12. Conclusion and Future Research

This comprehensive framework Dr. S. L. Burton, [

47], outlined in this study for designing and implementing a cybersecurity laboratory addresses a pressing educational need by bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and applied skills. By integrating experiential learning principles and modular lab design, the framework equips students with practical competencies directly aligned with industry demands [

1,

7]. These findings reinforce the significance of a hands-on, adaptive educational environment in producing graduates who are workforce-ready and capable of responding to evolving cybersecurity challenges [

8].

The original contribution of this research is its synthesis of current best practices and educational theory into a replicable lab model tailored for teaching plus curriculum and course development. This model not only supports student achievement but also enhances facilitator collaboration, institutional and organizational adaptability, and the scalability of cybersecurity programs [

28,

37]. The Modular Adaptive Cybersecurity Laboratory Framework (MACLF) is significant because it advances student achievement [42; 43] and strengthens facilitator collaboration [

42,

43], enhances institutional adaptability [

42,

43], and enables scalable growth [

42,

43] of cybersecurity programs, ensuring that educational environments remain responsive to evolving industry demands and continuously foster innovation at organizational and systemic levels. Policy and management implications include the necessity of sustained resource investment, ongoing facilitator professional development, and continuous alignment with rapidly changing technological and threat landscapes [

33,

44]. The study also highlights the significance of regular assessment cycles and stakeholder feedback in maintaining the relevance and impact of lab-based education [

2].

Limitations of this work are primarily rooted in resource constraints and the challenge of keeping laboratory infrastructure current with technological advancements [

45]. This factor may hinder widespread adoption in less-funded institutions [

30]. Additionally, disparities in facilitator expertise and support can affect the quality of experiential learning opportunities [

27]. Despite these challenges, the framework’s emphasis on modularity and feedback-informed iteration provides a foundation for continuous improvement and adaptability across diverse educational contexts [

29,

46].

Future research should investigate the integration of emerging technologies (i.e., artificial intelligence, automation, and advanced simulation tools) into cybersecurity laboratory environments. Longitudinal studies examining the career trajectories of program graduates and the broader institutional impacts of lab adoption offer valuable insights into long-term effectiveness and inform further refinements. By adopting the proposed model and fostering a culture of ongoing assessment and innovation, institutions and organizations will be better positioned to meet the demands of the digital future and to prepare graduates capable of safeguarding complex information environments.

References

- Kolb, D. A. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall, 1984.

- National Research Council. Education for life and work: Developing transferable knowledge and skills in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2012. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. America’s lab report: Investigations in high school science. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press., 2006. (accessed on 06.25.2025). [CrossRef]

- John, S.N., Noma-Osaghae, E., Oajide, F., Okokpujie, K. Cybersecurity Education: The Skills Gap, Hurdle!. In Daimi, Innovations in Cybersecurity Education K., Francia III, G. (eds) Springer, Cham,. 2020, pp 361-376. [CrossRef]

- Dodla, T.R., & Jones, L. Identifying knowledge management strategies for knowledge management systems. Access to Science, Business. Innovation in the Digital Economy, 2023, 4, 261-277. [CrossRef]

- Fantinelli, S., Cortini, M., Di Fiore, T., Iervese, S., & Galanti, T. Bridging the gap between theoretical learning and practical application: A qualitative study in the Italian educational context. Education Sciences, 2024, 14, 198. [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, M. Supporting experiential learning for expanding successes: extending Kolb’s model. Human Resource Development International, 2025, 28, 423-445. [CrossRef]

- Tuncel, A., & Atan, A. How to clearly articulate results and construct tables and figures in a scientific paper? Turkish Journal of Urology, 2013, 39, Suppl 1. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M., Le, N. T., Chow, Y.-W., & Susilo, W. Strategic approaches to cybersecurity learning: A study of educational models and outcomes. Information, 2024, 15, 117. [CrossRef]

- Hickey, D. T., & Kantor, R. J. Comparing cognitive theories of learning transfer to advance cybersecurity instruction, assessment, and testing. Journal of Cybersecurity Education, Research and Practice, 2024, 1. [CrossRef]

- ICS2. 2024 ISC2 Cybersecurity Workforce Study Prepares for an AI-Driven World. ISC2, 2024, October 31.

- 17. Karagiannis, S., Magkos, E., Karavaras, E., Karnavas, A., Nikiforos, M. N., & Ntantogian, C. (2024). Towards NICE-by-design cybersecurity learning environments: A cyber range for SOC teams. Journal of Network and Systems Management, 2024, 32. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, T., Bridging the gap navigating: The challenges of modern cybersecurity, RSA conference blog, 2025, May 21.

- Saldaña, J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers (4th ed.). Sage Publications, 2021.

- Irvine, C. E., Thompson, M. F., & Khosalim, J. Labtainers: A framework for parameterized cybersecurity labs using containers. Naval Postgraduate School Technical Report, 2023.

- Burton, S. L. Best practices for faculty development through andragogy in online distance education (Order No. 10758601). Available from ProQuest Central; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global; ProQuest One Academic; Publicly Available Content Database. (1989663912), 2014.

- Towhidi, G., & Pridmore, J. Aligning cybersecurity in higher education with industry needs. Journal of Information Systems Education, 2023, 34, 70–83.

- Ismail, M., Madathil, N. T., Alalawi, M., Alrabaee, S., Al Bataineh, M., Melhem, S., & Mouheb, D. Cybersecurity activities for education and curriculum design: A survey. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 16, 100501, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kebande, V. R. The impact of virtual laboratories on active learning and engagement in cybersecurity distance education. arXiv, 2024, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, H., Birks, M., Franklin, R., & Mills, J. Case study research: Foundations and methodological orientations. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2017, 18, Article 19. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Waters, L., & Johnstone, A. Embedding Well-being into School: A Case Study of Positive Education Before and During COVID-19 Lockdowns. Journal of School and Educational Psychology, 2022, 2, 60–77. [CrossRef]

- Chernikova, O., Heitzmann, N., Holzberger, D., Seidel, T. & Fischer, F. Simulation-based learning in higher education: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 2020, August, 90, pp 499-541. [CrossRef]

- Kavak, H., Padilla, J. J., Vernon-Bido, D., Diallo, S. Y., Gore, R., & Shetty, S. (2021). Simulation for cybersecurity: State of the art and future directions. Journal of Cybersecurity, 2021, 7, (1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Denton, K., & Simmons, M. (2021). Virtual Learning Assessment: Practical Strategies for Instructors in Higher Education. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 2021, 3, 42-48.

- Aebersold, M. Simulation-based learning: No longer a novelty in undergraduate education. Center for Medical Simulation 2018, 23. [CrossRef]

- INACSL Standards Committee, McDermott, D.S., Ludlow, J., Horsley, E., & Meakim, C. Virtual simulation: An educator’s toolkit. Centre for Faculty Development, 2021.

- Gauthier, L., & Waqar, Y. High impact learning for facilitator training and development. Faculty Development Journal, 2021, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, I. A., Laroiya, S., & Singh, R. Holistic cybersecurity risk management framework. SSRN (2024, February 6). [CrossRef]

- Lehane, L. Experiential learning: David A. Kolb. In Science Education in Theory and Practice, Akpan, B., Kennedy, T.J, Eds.,: Springer : Cham, 2025, pp 241–257. [CrossRef]

- Takkouch, M. & Zukowski, S. & Campbell, N. Students’ perspectives and experiences with equity, diversity, inclusion, and accessibility in online and in-person undergraduate science laboratory courses. Journal of Perspectives in Applied Academic Practice, 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M., Dooley, K. E., & Roberts, T. G. A phenomenological study of intensive experiential learning for university faculty professional development. Journal of Experiential Education, 2024, 47, 685-703. [CrossRef]

- Burrell, D. N. Innovations from Academia around Cybersecurity Workforce and Faculty Development. MWAIS 2019 Proceedings, Paper 21, 2019.

- Grimus, M. Emerging technologies: Impacting learning, pedagogy and curriculum development. In Emerging Technologies and Pedagogies in the Curriculum. Bridging Human and Machine: Future Education with Intelligence. Yu, S., Ally, M., Tsinakos, A. (eds) Springer, Singapore, 2020, pp. 127-151. [CrossRef]

- Burton, S. L. Modular Adaptive Cybersecurity Laboratory Framework (MACLF) by Dr. S. L. Burton (Image). 2025.

- Blyznyuk, T., & Kachak, T. Benefits of Interactive Learning for Students’ Critical Thinking Skills Improvement. Journal of Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University, 2024, 11, 94–102. [CrossRef]

- Wurdinger, S., & Allison, P. Faculty perceptions and use of experiential learning in higher education. Journal of E-Learning and Knowledge Society, 2017, 13, 15–26.

- National Institute of Standards & Technology [NIST]. Building a cybersecurity and privacy learning program: NIST publishes SP 800-50r1. National Institute of Standards & Technology. 2024, September 12. [CrossRef]

- Straight, R. (2024). Beyond human-centric models in cybersecurity education: A pilot posthuman analysis of the nice workforce framework for cybersecurity. Journal of Cybersecurity Education, Research and Practice, 2024, 1. [CrossRef]

- McCance, K. R., & Blanchard, M. Measuring the Interdisciplinarity and Collaboration Perceptions of U.S. Scientists, Engineers, and Educators. AERA Open, 2023, 9, 1–21. [CrossRef]

-

Kaziukonis, V. How to build a culture of cyber resilience in your organization. Forbes Technology Council, 2024, September 5..

- Jones, L. A. Unveiling human factors: Aligning facets of cybersecurity leadership, insider threats, and arsonist attributes to reduce cyber risk. SocioEconomic Challenges, 2024, 8, 44–63. [CrossRef]

- Judd, T., Bisgin, H., Huseinovic, A., Derani, M., & Uludag, S. Coalescing Research into Modular and Safe Educational Cybersecurity Labs with AI Solutions. Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Washington, DC, 2024, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Vykopal, J., Seda, P., Švábenský, V., & Čeleda, P. (2023). Smart environment for adaptive learning of cybersecurity skills. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 2023, 16, pp. 443-456. [CrossRef]

- Fukasaku, Y. Management of Technological Resources for Sustainable Development. In Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS); UNESCO-EOLSS Joint Committee: Paris, France, 2020.

- Yuwono, M.A.; Ellitan, L. Technological development and resource constraints: A critical analysis. Int. J. Res. 2024, 11, 1455.

- Evanick, J. Improving instructional design: feedback and iterative refinement. eLearning Industry, 2023. https://elearningindustry.com/improving-instructional-design-feedback-and-iterative-refinement (accessed on 07/17/2025).

- The Modular Adaptive Cybersecurity Laboratory Framework (MACLF) by Dr. S. L. Burton (2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).