1. Introduction

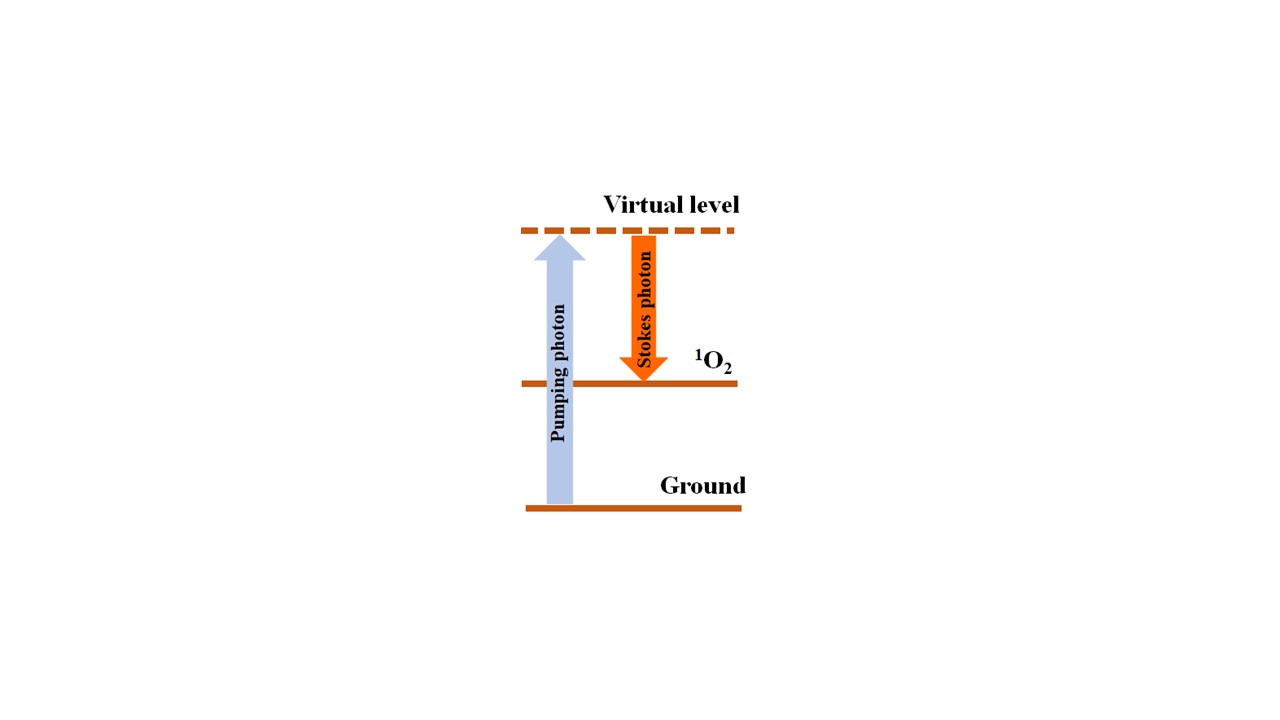

Singlet oxygen (

1O

2) corresponds to the lowest excited electronic quantum level of molecular oxygen. In this state, the molecule is highly electrophilic, which is the basis for its broad applications in photochemistry, photobiology, and photomedicine [1-5]. Quantum mechanics forbids direct one-photon excitation toward the

1O

2 state, resulting in a low transition probability. Photosensitization is the general method for efficient

1O

2 photoproduction [6-7]. A large photosensitizer molecule absorbs visible (VI) light, accumulating the absorbed energy on a triple metastable level. From there, the energy is transmitted to surrounding oxygen molecules, exciting the

1O

2 state. We have recently demonstrated a photosensitizer-free

1O

2 photoexcitation based on the Raman effect [8-10]. A pumping photon produces a Raman transition from ground toward the

1O

2 level, emitting a Stokes photon of lower energy. The difference between the pumping and Stokes photon energies is equal to the energy needed for the transition. The lack of use of the photosensitizer simplifies the procedures and prevents potential secondary effects, like excessive photosensitivity or unexpected phototoxicity. In a recent publication, we demonstrated the detection of phosphorescence at 1270 nm from the Raman photoexcited

1O

2 [

10]. However, determining the efficiency of the process (Φ

Δ) is still a task to be completed. The present work eliminates the gap. We define Φ

Δ as the relation between the number of Raman-generated

1O

2 molecules and the total number of pumping photons. We measure Φ

Δ of (8±2) 10

-5 in distilled water (H

2O) when pumping at 410 nm with nanosecond pulses of an energy of 13 mJ.

Furthermore, we compare the Raman approach with the photosensitization method using the well-known photosensitizer, Rose Bengal. The 1O2 chemical trap, uric acid, is used to evaluate both methods. We show that, over time, the Raman method generates more 1O2 molecules than the photosensitization method. Rose Bengal exhibits near-full photobleaching after sixty minutes of irradiation, interrupting 1O2 photoproduction. In the Raman method, photobleaching does not take place. Consequently, the Raman 1O2 generation continues without interruption even after hours of irradiation.

2. Theoretical Considerations

Figure 1a shows a simplified schematic of

1O

2 Raman excitation. A pumping photon induces a Raman transition from the ground toward the

1O

2 level, emitting a Stokes photon. For example, when pumping at 410 nm in H

2O, the

1O

2 Stokes component occurs around 605 nm. The magnitude of this signal yields a direct measurement of the amount of excited

1O

2 molecules. Other Stokes photons related to the excitation of solvent vibrational modes and their overtones are generated. When pumping at 410 nm, the H

2O stretching vibrational mode produces a Stokes component at 475 nm. An additional overtone of this Stokes signal is also observed at 566 nm. The difference in wavelength between the Stokes components allows for their identification and separation using optical filters. Experiments below demonstrate that most of the energy involved in the Raman process originates from the solvent stretching modes. Despite this fact, the

1O

2 Stokes can still be detected, showing that a significant amount of

1O

2 molecules is still being generated.

In the photosensitization method, the photosensitizer’s quantum yield measures the efficiency of

1O

2 photoproduction [11-15]. The photosensitizer’s quantum yield is defined as the number of excited oxygen molecules divided by the number of photons absorbed by the photosensitizer. The commonly used photosensitizer Rose Bengal exhibits a quantum yield value of 0.76 at 532 nm in H

2O [15-16]. As discussed above, for the Raman method, Φ

Δ is defined by the equation

where

NΔ and

Np are the number of

1O

2 Stokes and pumping photons, respectively. The number of photons can be estimated by measuring the signal energy corresponding to each process divided by the energy of one photon. Then, we can write

where

is the averaged

1O

2 Stokes wavelength,

EΔ is its energy,

λp is the pump wavelength, and

Ep is its energy.

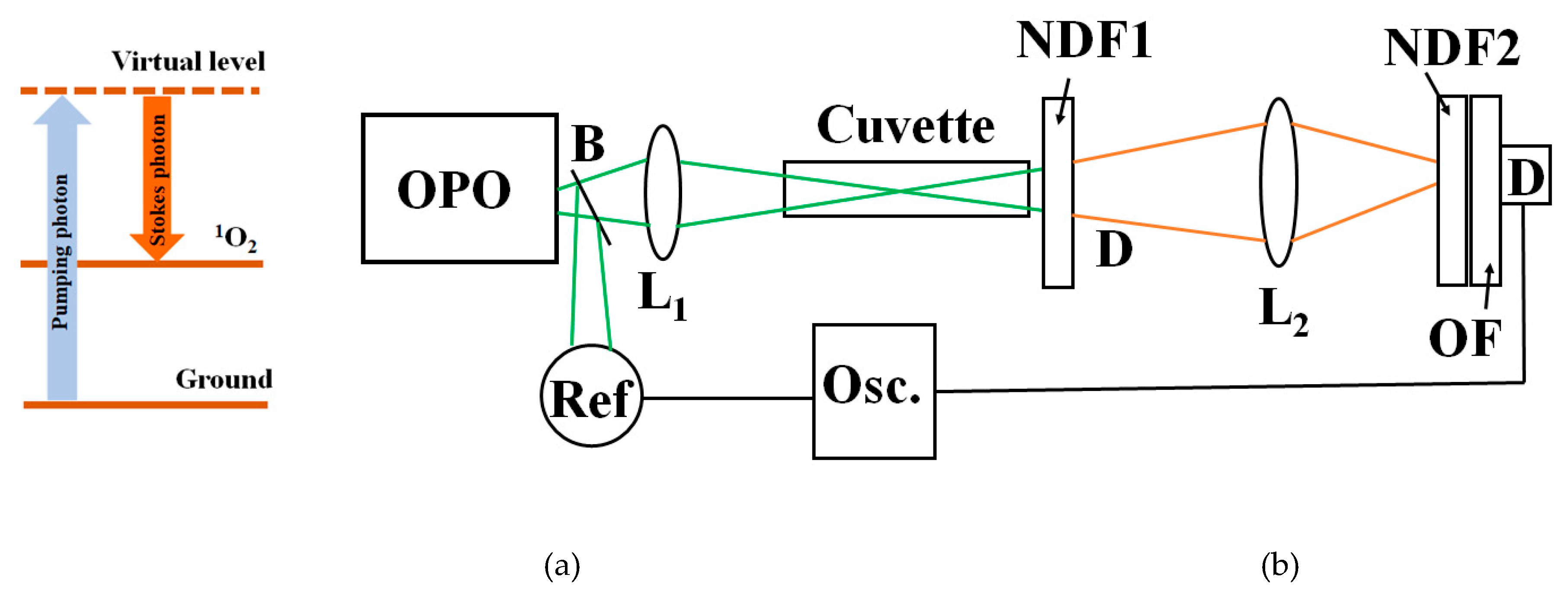

2. Materials and Methods

Figure 1b shows the experiment setup. An optical parametric oscillator (OPO, OPOTEK, Carlsbad, CA, US) provides 6-nanosecond excitation in the blue-green region (410-520 nm) with an average energy per pulse of 14 mJ. A beam splitter B deviates part of the light toward a reference detector. A 20 cm focal length lens L

1 focuses the pump light onto a 10 cm path-length glass cuvette containing the sample. A neutral filter (NDF1) placed at the exit of the sample significantly reduces the power to avoid optical damage to the filters. A lens L

2 focuses the resulting signal onto the detector. An additional neutral density filter, NDF2, is placed at the entrance of the detector, reducing the signal intensity to avoid detector saturation. To detect the signal, we use a silicon detector (Thorlabs DET100A2, Newton, NJ, US) with a responsivity of 0.2 A/W at 410 nm and 0.4 A/W at 610 nm and a rise time of 35 ns.

The silicon detector signal is sent without further amplification toward a digital oscilloscope (TDS 3052, Tektronix, Beaverton, OR, US) for averaging and display. The oscilloscope averages 512 pulses, providing a stable signal proportional to the emitted luminescence. Due to their Raman character, the Stokes signals follow the time dependence of the pump pulse. Since the detector risetime is longer than the excitation pulse, the signal time evolution is limited by it. To calibrate the signal provided by the silicon sensor, we use calibrated detectors. To measure pulse energies above 100 μJ, we use a pyroelectric energy meter (PE25BF-DIF-C, Ophir USA, Newport Corporation, North Logan, UT, US). For measuring energies below 100 μJ, we use a diode power meter (Thorlabs PM100, Newton, NJ, US).

We detect the pump signal using the corresponding interference filter. When pumping at 410 nm, we use an interference filter at (410±10) nm. The 1O2 Stokes signal is measured using a long-pass filter. When pumping at 410 nm, we use a filter with a cutoff at 610 nm. Below, we show that the collected signal corresponds to the amount of 1O2 molecules. The Stokes signals from the solvent stretching modes are evaluated in a similar manner.

Aerated distilled H

2O in 20 cm and 10 cm pathlength glass cuvettes was used as a sample. We use solutions of sodium bisulfite (NaHSO

3) as an oxygen quencher to aid in identifying the oxygen contribution [

17]. The concentration of dissolved oxygen in H

2O decreases when the NaHSO

3 concentration increases. Water solutions of NaHSO

3 exhibit a reduced

1O

2 Stokes signal, as it corresponds to a reduced oxygen concentration. To measure the amount of oxygen in the solutions, we used an oxygen optical sensor (Vernier Optical DO Probe, Vernier, Beaverton, OR).

We used uric acid as a 1O2 chemical trap to compare the efficiency of the photosensitization and Raman methods. The uric acid UV absorbance at 294 nm is a direct measurement of the amount of 1O2 being generated [18-19]. We use Rose Bengal as a photosensitizer. A solution of 10 μM Rose Bengal in H2O was prepared.

To collect spectra of the Stokes signals, we use a spectrometer (red Tide USB 650, Ocean Optics, Orlando, FL).

4. Results and Discussion

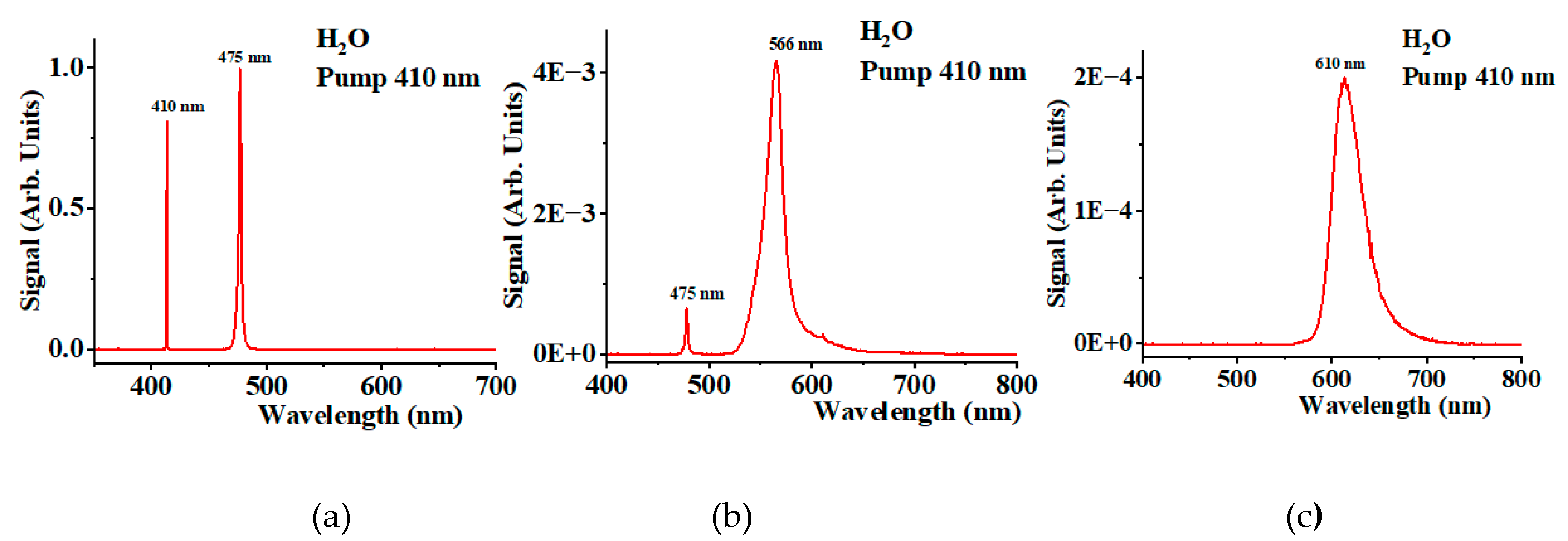

The solvent Stokes contributions are significant, but they can be eliminated using optical filters.

Figure 2a shows the spectra collected using the Ocean Optics spectrometer after passing through neutral filters with a total optical density of six when pumping distilled water at 410 nm. The first peak at 410 nm corresponds to the pumping field. The peak at 475 nm corresponds to the H

2O stretching mode at a frequency of 3350 cm

-1 [20-23]. This mode is the dominant part of the total Stokes field.

Figure 2b shows the spectrum after using a neutral density filter with an optical density of two and a long-pass filter with a cutoff at 550 nm. A diminished Stokes peak at 475 nm and a peak at 566 nm are observed. The last peak corresponds to the first overtone of the H

2O vibrational mode at 6700 cm

-1. When using a neutral density filter with an optical density of one and a long-pass filter with a cutoff at 610 nm, the solvent Stokes components at 475 nm and 566 nm are fully depleted (see

Figure 2c). The arbitrary units in all figures (2a, 2b, and 2c) are the same. Thus, the signal depicted by

Figure 2c is four orders of magnitude smaller than the signal shown on

Figure 2a and one order of magnitude smaller than the signal shown on

Figure 2b. To demonstrate that the curve shown in

Figure 2c is oxygen-dependent, we reduce the oxygen concentration using the oxygen quencher NaHSO

3.

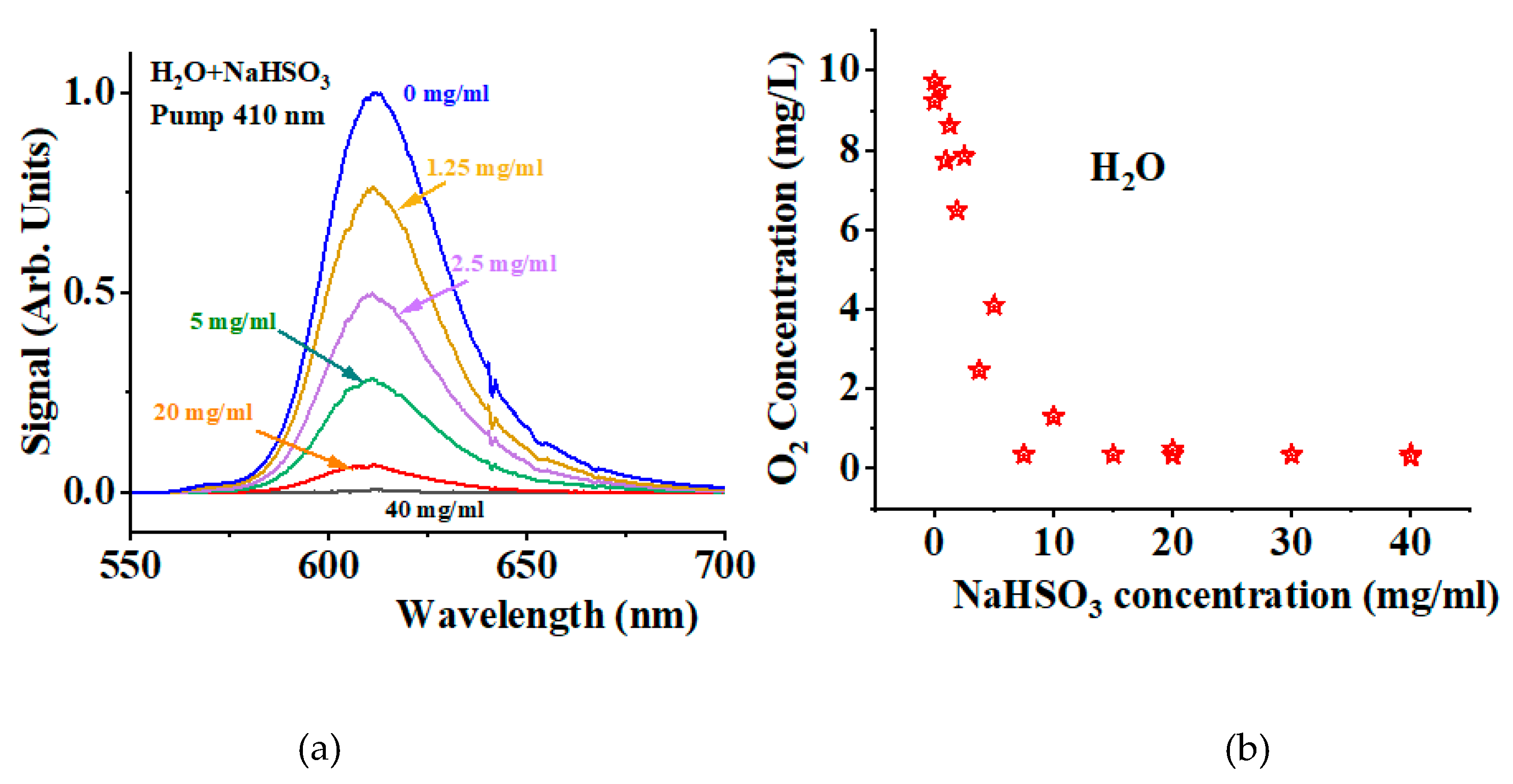

Figure 3a shows the singlet peak obtained when using the long-pass filter at 610 nm for different concentrations of NaHSO

3. The blue line corresponds to the condition where no NaHSO

3 is added. As the NaHSO

3 concentration increases, the signal decreases. At a concentration of 40 mg/ml, the signal has been significantly reduced. Using the optical oxygen sensor, we measure the oxygen concentration in each sample solution.

Figure 3b shows how the oxygen concentration decreases as the NaHSO

3 concentration increases. A nearly linear dependence is observed for concentrations below 10 mg/ml.

Figure 3 shows that the observed Stokes signal collected using the 610 nm long-pass filter is oxygen-dependent. Its amplitude provides a direct measurement of the amount of

1O

2 molecules being generated in the process. We note that the H

2O Stokes components are not affected by the presence of NaHSO

3.

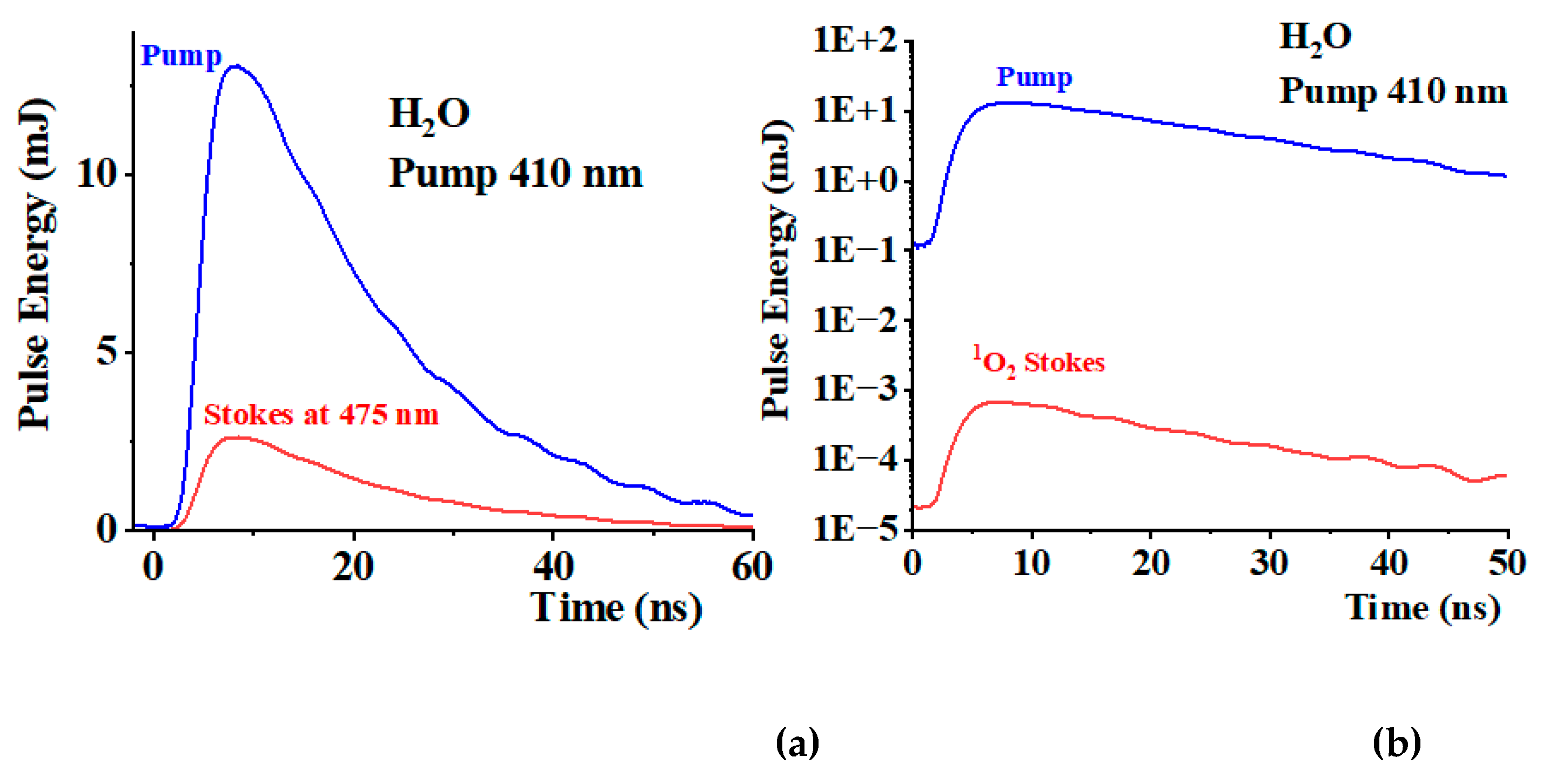

Figure 4a shows the pulse energy corresponding to the excitation pump light (blue light). The signal was collected using the diode detector and energy sensor for calibration purposes. We use an interference filter at (410±10) nm to select only the pump light. Using an interference filter at (475±10) nm, we collect a Stokes signal corresponding to the H

2O stretching mode at 3350 cm

-1 (red line in figure 4a). A significant portion of the pump field, (23±1) %, is converted into this Stokes component. The standard deviation is estimated over 10 experiments. We also measured the contribution from the overtone at 566 nm using the corresponding filter, which accounted for (0.25±0.01) % of the total incoming light. The

1O

2 Stokes contribution is significantly smaller.

Figure 4b shows the

1O

2 Stokes signal, together with the pumping signal, on a logarithmic scale. We estimated a pulse energy of (0.7±0.2) μJ. Under these conditions, equation (2) provides Φ

Δ=(8±2) 10

-5. Using these values, we estimate that each pulse of pumping light generates approximately 4 10

11 1O

2 molecules.

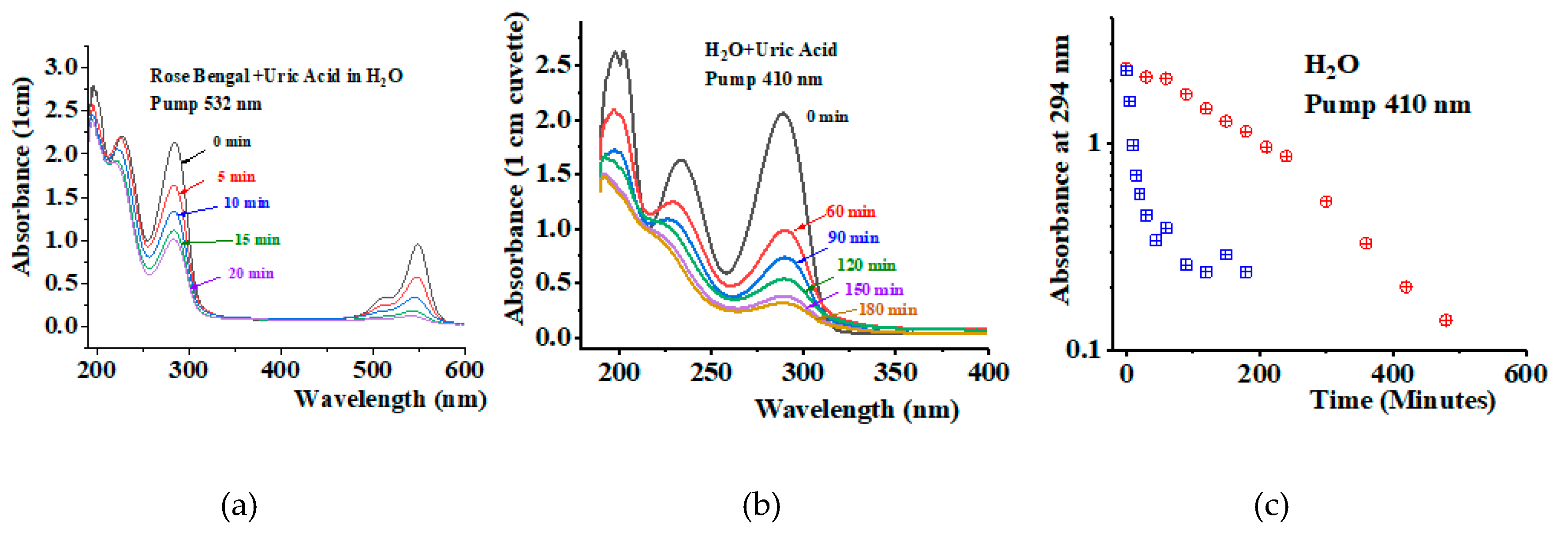

To understand the potential practical applications of the Raman method, we compare it with the conventional photosensitization method. We use the well-known photosensitizer Rose Bengal for this purpose. We prepare solutions of Rose Bengal in H2O at a concentration of 10 μM. We also use uric acid at a concentration of 120 μM as a 1O2 chemical trap to monitor the amount of 1O2 being generated in each method. We irradiate the Rose Bengal and uric acid solution at 532 nm in five-minute intervals. At the end of each interval, we measure the UV spectrum of the solution to monitor the amplitude of the peak at 294 nm.

Figure 5a shows the UV-VI absorbance spectra of the Rose Bengal solution containing uric acid at a concentration of 120 μM, measured for different irradiation times. We observe a reduction in the uric acid peak at 294 nm, corresponding to the depletion of

1O

2 generated by the uric acid. The peak depletes by a factor of four after twenty minutes but does not entirely disappear. The spectra also show the Rose Bengal absorbance peak around 540 nm. This peak also decreases, evidencing photobleaching. Due to the photobleaching of Rose Bengal, the process of

1O

2 generation stops.

Figure 5b shows results obtained for a solution of uric acid with no photosensitizer in H

2O. In this experiment, irradiation is performed at 410 nm over longer time intervals: 60, 90, 120, and up to 480 minutes. Again, we observe depletion of the uric acid peak at 294 nm, evidencing the Raman generation of

1O

2 molecules. No photobleaching effect is observed in the Raman experiment, resulting in a more complete reduction of the 294 nm peak over time.

Figure 5c shows the uric acid absorbance at 294 nm as a function of irradiation time for both experiments. For the Rose Bengal solution, the uric acid absorbance at 294 nm decreases from an initial value of 2.3 to 0.3 after 20 minutes of irradiation. It remains around this value for the rest of the experiment. For the Raman experiment, the peak reduces from 2.3 to a value around 0.1 after 400 minutes of irradiation. The Rose Bengal experiment exhibits a fast photoproduction of

1O

2. However, due to photobleaching of the photosensitizer, the process is not fully complete. In the Raman experiment, the

1O

2 photoproduction is less effective. However, because of the absence of photobleaching, the

1O

2 photoexcitation persists as long as the sample is being irradiated.

5. Conclusions

We have estimated the efficiency of the

1O

2 Raman photogeneration in H

2O by measuring the signal amplitude of the

1O

2 Stokes signal. Defining the efficiency as the relation between the number of photogenerated

1O

2 molecules divided by the number of pumping photons, we determine an efficiency of (8±2) 10

-4 for H

2O at 410 nm. We compare the Raman method with the photosensitization method using Rose Bengal as a photosensitizer. The photosensitizer generates

1O

2 molecules rapidly, but the process eventually stops due to photobleaching of the photosensitizer. The Raman method generates

1O

2 molecules at a rate slower than the photosensitization methods. However, thanks to the intrinsic absence of photobleaching, the Raman method generates more

1O

2 molecules over time than the photosensitization method, despite its low efficiency values. The efficiency of the Raman method can be enhanced based on the fundamental principles of Raman interaction. Raman lasers, Raman amplifiers, and Raman fiber sensors are based on these principles [23-25]. Stokes signal grows exponentially with distance. The gain depends on the pumping field intensity, the nonlinear Raman susceptibility, and the propagation losses. A system should be designed to provide a significant gain for the

1O

2 Stokes component with low losses, while maintaining low gain and substantial losses for the solvent Stokes components. These considerations may play a crucial role in improving the

1O

2 Raman photogeneration efficiency for practical applications of the Raman approach. One useful application is the purification of water caused by viruses or bacteria. In a previous communication, we demonstrated the deactivation of viruses in an aqueous environment through simple irradiation with blue light, without the use of photosensitizers [

26].

Funding

The research was sponsored by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and was accomplished under Grant Number W911NF-23-1-0245. The views and conclusions are those of the author and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the Air Force Office of Scientific Research or the US Government. The US Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Government purposes, notwithstanding any copyright notation herein.

Data Availability Statement

Al relevant data are within the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

“The author declares no conflicts of interest.”

References

-

Singlet Oxygen: Applications in Biosciences and Nanosciences, Volume 2 - Comprehensive Series in Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences, Volume 14, 1st ed.; S. Nonell, C. Flors, editors. Cambridge, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry, Thomas Graham House, 2016.

- Pibiri, I.; Buscemi, S.; Palumbo Piccionello, A.; Pace, A. Photochemically Produced Singlet Oxygen: Applications and Perspectives. ChemPhotoChem 2018, 2(7), 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRosa, M.C.; Crutchley, R.J. Photosensitized Singlet Oxygen and its Applications. Coordination Chem. Rev 2002, 233-234, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobotta, L.; Skupin-Mrugalska, P.; Mielcarek, J.; Goslinski, T.; Balzarini, J. Photosensitizers Mediated Photodynamic Inactivation against Virus Particles. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2015, 15(6), 503–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dougherty, T.J.; Gomer, C.J.; Henderson, B.W.; Jori, G.; Kessel, D.; Korbelik, M.; Moan, J.; Peng, Q. “Photodynamic Therapy”. JNCI: J. Nat. Cancer Inst 998, 90, 889–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank Kino, F.; Medeiros Silva, G.T. The Photophysics of Photosensitization: A brief overview. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 2021, 7, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelin, C.; Hoffmann, N. Photosensitization and Photocatalysis - Perspectives in organic Chemistry. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 12046–12055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcano Olaizola, A.; Kingsley, D.; Kuis, R. ; A. Johnson, A. Stimulated Raman Generation of Aqueous Singlet Oxygen without Photosensitizers. J. Photochem. Photobio. B: Bio 2022, 235, 112562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcano Olaizola, A.; Zerrad, A.; Jenneto, F.; Kingsley, D. “Confirming the Stimulated Raman Origin of Singlet-Oxygen Photogeneration”. J. Raman Spectros. 2024, 2024. 55, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcano Olaizola, A. “Near-Infrared Phosphorescence of Raman Photogenerated Singlet Oxygen.” Photochem 2025. 5(1), 7-14. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, F.; Helman, W.P; Ross, A.B. Quantum Yields for the Photosensitized Formation of the Lowest Electronically Excited Singlet State of Molecular Oxygen in Solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data, 1993. 22(1), 113-262.

- Ossola, R.; Jönsson, O.M.; Moor, K.; McNeill, K. Singlet Oxygen quantum yields in environmental waters. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 4100–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutkus, L.V.; Rickenbach, S.S.; McCormick, T.M. Singlet Oxygen Quantum Yields Determined by Oxygen Consumption. J. Photochem Photobiol. A: Chemistry 2019, 378, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.; Yun, Y.J.; Ayitou, A.J.L. Estimation of Singlet Oxygen Quantum Yield Using Novel Green-Absorbing Baird-Type Aromatic Photosensitizers. Photochem. Photobiol. 2022, 98, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szewczyk, G.; Mokrzynski, K. Concentration-Dependent Photoproduction of Singlet Oxygen by Common Photosensitizers. Mol. 2025, 30(5), 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murasecco-Suardi, P.; Gassmann, E.; Braun, A.M.; Oliveros, E. Determination of the Quantum Yield of Intersystem crossing of Rose Bengal. Helvetica, 1987. 70, 1760-1773. [CrossRef]

- Salasi, M.; Pojtanabuntoeng, T.; S. Wong, S.; Lehmann, M. Efficacy of bisulfite ions as an oxygen scavenger in monoethylene glycol (at least 20 wt%)/water mixtures. SPE J. 2017. 22(05), 1467–1477.

- R. C. Trivedi, L. Rebar, K. Desal, L. J. Stong, New ultraviolet (340 nm) method for essay of uric acid in serum or plasma. Clin. Chem 1978, 1978. 24, 562–566.

- F. Fisher, G. Graschew, H. J. Sinn, W. Maier-Borst, W. J. Lorenz, P. M, Schlag, A chemical dosimeter for the determination of photodynamic activity of photosensitizers. Clin. Chim. Acta 1998. 274, 89-104.

- Gao, Y.; Gong, N.; Sun, C.; Wang, W.; Men, Z. Stimulated Raman scattering investigation of isotopic substitution H2O/D2O system. J. Mol. Liquids 2020, 297, 11923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q. The Raman OH stretching bands of liquid water. Vibrational Spectros. 2009, 51(2), 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertie, J.E.; Lan, Z. Infrared intensities of liquids XX: The intensity of the OH stretching band of liquid water revisited, and the best current values of the optical constants of H2O(l) at 25°C between 15,000 and 1 cm-1," Appl. Spectrosc. 1996, 50, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdal, B.; Bahram, J. Demonstration of a Silicon Raman Laser. Opt. Exp. 2004, 12, 5269–5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, H.; Jone, R.; Liu, A.; Cohen, O.; Hak, D.; Fang, A.; Paniccia, M. A Continuous -Wave Raman Silicon Laser. Nature 2005, 433, 725–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Huang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang,B.; Ji, M. Fiber-Enhanced Stimulated Raman Scattering and Sensitive Detection of Dilute Solutions. Biosensors, 2022; 12, 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley, D.H.; Kuis, R.; Perez, R.; Basaldua, I.; Burkins, P.; Marcano Olaizola, A.; Johnson, A. Oxygen-dependent laser inactivation of murine norovirus using visible light lasers. Virology Journal 2018. 15:117. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).